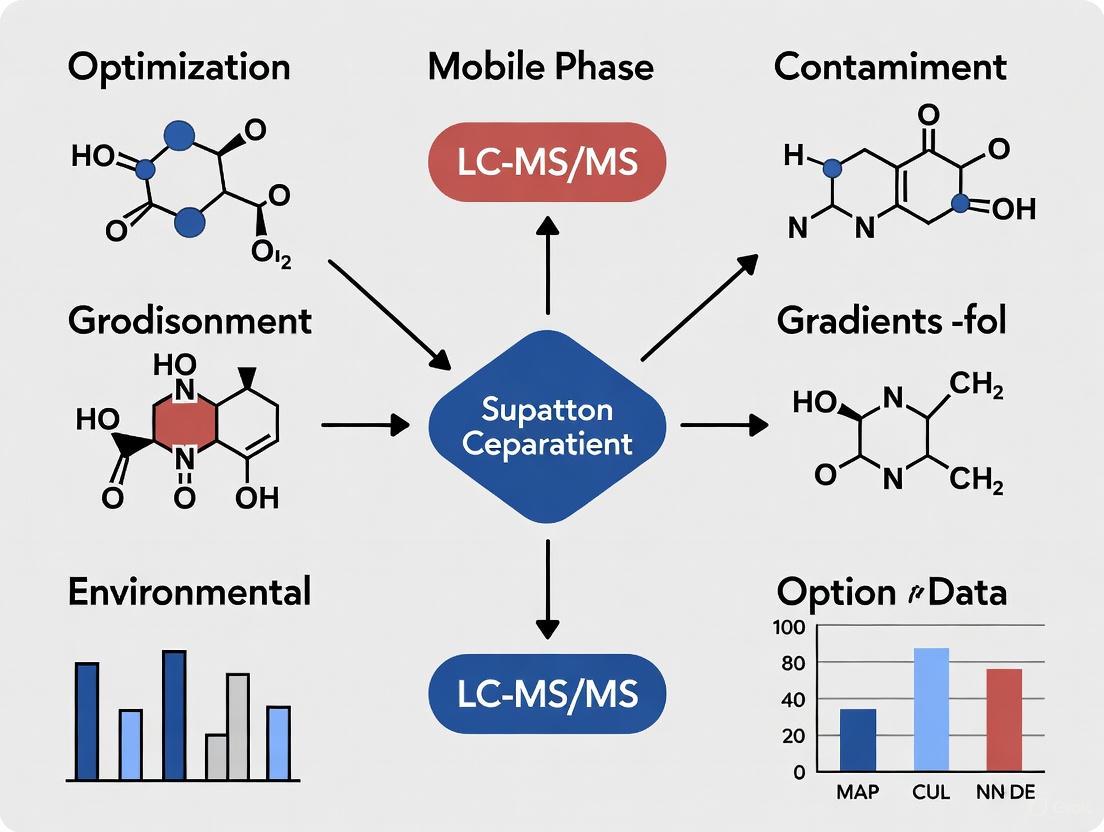

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Mobile Phase Gradients in LC-MS/MS for Enhanced Contaminant Separation

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of developing efficient LC-MS/MS methods for separating complex contaminant mixtures with diverse physicochemical properties.

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Mobile Phase Gradients in LC-MS/MS for Enhanced Contaminant Separation

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of developing efficient LC-MS/MS methods for separating complex contaminant mixtures with diverse physicochemical properties. By integrating foundational principles with cutting-edge optimization approaches, we explore systematic methodologies for mobile phase gradient design that enhance sensitivity, resolution, and analytical robustness. The article provides actionable strategies for mitigating common issues including ion suppression and retention time variability, while highlighting advanced techniques such as Design of Experiments (DoE) and machine learning-assisted optimization. Through comparative analysis of validation frameworks and troubleshooting protocols, this work serves as an essential resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to improve contaminant monitoring and method transferability in regulated environments.

Core Principles of Mobile Phase Behavior and Contaminant Separation Mechanisms

Fundamental Interactions in Reversed-Phase Chromatography for Diverse Contaminants

Fundamental FAQ: Core Principles

Q1: What is the fundamental retention mechanism in Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RPC)? RPC operates on a partition chromatography principle, where separation is based on the hydrophobic interactions between analytes in a polar mobile phase and a non-polar stationary phase. The more hydrophobic a molecule is, the more strongly it will bind to the stationary phase and the longer it will be retained. Elution is achieved by decreasing the polarity of the mobile phase, typically by increasing the concentration of an organic solvent, which reduces these hydrophobic interactions [1] [2].

Q2: How does mobile phase pH affect the retention of ionizable contaminants? Mobile phase pH is a critical factor for ionizable compounds, as it influences their polarity and thus their retention.

- For acidic contaminants (e.g., those with carboxylic acid groups): At a mobile phase pH below the analyte's pKa, the acid is protonated (neutral), making it less polar and increasing its retention. At a pH above the pKa, the acid is deprotonated (charged), making it more polar and significantly decreasing its retention [3] [4].

- For basic contaminants (e.g., those with amine groups): The opposite is true. At a mobile phase pH below the pKa, the amine is protonated (charged), leading to lower retention. At a pH above the pKa, the amine is deprotonated (neutral), resulting in higher retention [3] [4]. Working at a pH near an analyte's pKa can lead to robustness issues; small variations in pH can cause large shifts in retention time. For method robustness, operating at a pH at least 1-2 units away from the pKa is advised [3].

Q3: What are the roles of ion-pairing agents and how should they be selected? Ion-pairing agents are additives that interact with ionized analytes to neutralize their charge and increase their hydrophobicity, thereby enhancing retention on the reversed-phase column. They are essential for analyzing highly polar ionic compounds that would otherwise not be retained.

- For acidic contaminants and general use in proteomics, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is widely used, often at concentrations of 0.05%-0.1% [5] [1].

- For basic contaminants, alkyl sulfonates (e.g., heptane or octane sulfonate) can be used.

- In LC-MS/MS applications, volatile agents are mandatory. Common choices include formic acid, acetic acid, ammonium formate, and ammonium acetate, typically in concentrations of 0.1% for acids or 2-10 mM for buffers [6] [3]. The choice of agent can significantly alter selectivity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: How do I resolve ghost peaks or unknown peaks in my chromatogram? Ghost peaks are typically caused by contaminants in the eluents or from incomplete elution of compounds in previous runs.

- Cause 1: Poor-quality eluent components. Trace organic impurities in solvents or water can bind to the column and elute later as ghost peaks [7].

- Solution: Use high-purity, HPLC-grade solvents and water. Ensure that all glassware and the instrument system are clean.

- Cause 2: Incomplete elution from a previous run. Strongly retained sample components may not have fully eluted [7].

- Solution: Implement a stronger cleaning gradient at the end of your sequence (e.g., a step to 95% organic solvent). Run a blank gradient (with no sample injection) to check if the peaks originate from the system itself [7].

Q2: My baseline is drifting significantly during a gradient run. What is the cause and how can I fix it? Baseline drift during a gradient is often linked to UV-absorbing mobile phase additives.

- Cause: The background absorbance of the mobile phase changes as the proportion of organic modifier increases. This is common with ion-pairing agents like TFA, which have different UV absorption properties in water versus acetonitrile [7].

- Solution: Eluent Balancing. Use slightly different concentrations of the UV-absorbing agent in your aqueous (Eluent A) and organic (Eluent B) mobile phases to compensate for this effect. For example, when using TFA with an acetonitrile gradient, a balanced system might use 0.065% TFA in water (Eluent A) and 0.050% TFA in acetonitrile (Eluent B) [7].

Q3: I am not getting enough retention for my target contaminants. What can I adjust?

- Solution 1: Decrease the organic solvent strength. A useful rule of thumb is that for a small molecule, a 10% decrease in the organic solvent percentage (%B) will roughly double the retention factor [4]. For example, shifting from 40% acetonitrile to 30% can significantly increase retention.

- Solution 2: Modify the pH. For acidic contaminants, lower the mobile phase pH to suppress ionization. For basic contaminants, raise the pH (where column stability allows) to suppress ionization [3] [4].

- Solution 3: Use a less hydrophobic stationary phase. While C18 is standard, strong retention can make elution difficult. A C8 or C4 column can facilitate elution for highly hydrophobic compounds [1].

- Solution 4: Employ an ion-pairing reagent. This is particularly effective for retaining ionic contaminants that are otherwise too polar [5] [3].

Q4: My peaks are broad or show tailing. How can I improve peak shape?

- Cause 1: Secondary interactions with residual silanols. On silica-based columns, acidic silanol groups can interact with basic analytes, causing tailing [5].

- Solution: Use a mobile phase with a low pH (e.g., with TFA or formic acid) to protonate silanols and minimize this interaction. Use "end-capped" columns designed to reduce the number of free silanol groups [5] [2].

- Cause 2: Inappropriate buffer concentration or column overload.

- Solution: Ensure adequate buffering capacity (typically 10-50 mM) to control pH precisely. For a high concentration of analyte, consider diluting the sample or injecting a smaller volume [3].

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for diagnosing and resolving common RPC issues.

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow for Reversed-Phase Chromatography

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions for setting up robust RPC methods, particularly for contaminant analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Purpose in RPC | Key Considerations for Contaminant Separation |

|---|---|---|

| C18 (ODS) Column [5] [2] | The most common stationary phase; provides strong retention for hydrophobic analytes via van der Waals interactions. | Ideal for a wide range of non-polar to moderately polar contaminants. Select a column with a pore size >10 nm for larger molecules [5]. |

| C8 or C4 Column [1] | Less hydrophobic stationary phases; useful for very hydrophobic contaminants or when faster elution is needed. | Use for contaminants that bind too strongly to C18 phases, facilitating their elution [1]. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) [1] [3] | Organic modifier; reduces mobile phase polarity to elute analytes. Low viscosity and UV cutoff. | Preferred for LC-MS/MS and low-UV detection due to low background absorbance and viscosity. Often provides different selectivity than methanol [1] [3]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) [3] [4] | Organic modifier; an alternative to ACN. Has different solvochromatic properties (more basic). | Use when selectivity with ACN is unsatisfactory. Rule of thumb: ~10% more methanol than ACN is needed for similar retention [4]. Higher viscosity can cause backpressure. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) [5] [1] | Ion-pairing agent / additive; suppresses silanol effects, ion-pairs with basic/amphoteric molecules, and maintains low pH. | Excellent for peptide and protein separations with UV detection. Not ideal for LC-MS due to ion suppression. Use balanced concentrations (e.g., 0.065% in A, 0.05% in B) to minimize baseline drift [7] [1]. |

| Formic Acid / Ammonium Formate [6] [3] | Volatile ion-pairing agents / buffers; used to control pH and aid ionization in LC-MS compatible methods. | Formic Acid: Common for positive ESI mode. Ammonium Formate: Provides buffering capacity. A combination (e.g., 10 mM ammonium formate/0.125% formic acid) can optimize performance in metabolomics [6]. |

| Ammonium Acetate / Acetic Acid [6] | Volatile buffers; used for pH control in LC-MS, especially in negative ion mode. | A combination (e.g., 10 mM ammonium acetate with 0.1% acetic acid) can be a good compromise for lipidomic profiling in ESI(-), providing signal intensity and stable retention times [6]. |

Method Optimization & Data Interpretation

Q1: What is a logical sequence for optimizing an RPC method for unknown contaminants? A systematic approach ensures efficiency.

- Select a Medium: Start with a standard C18 column and a simple, volatile mobile phase system (e.g., water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) [1] [8].

- Scout for Optimal pH: This is often the most critical factor for selectivity for ionizable compounds. Test different pH conditions (e.g., pH ~2.5 with formic acid, ~6.5 with ammonium acetate, ~10 with ammonium hydroxide*). *Note: Use polymer-based or specialized columns for high pH [1].

- Optimize the Gradient: Once a promising pH is found, optimize the gradient slope. A shallower gradient improves resolution of complex mixtures, while a steeper gradient shortens run time [1].

- Fine-tune Selectivity: If needed, change the organic modifier (e.g., from acetonitrile to methanol) or test a different stationary phase (e.g., C8, phenyl) [1] [4].

- Adjust Flow Rate and Temperature: Finally, optimize for speed and efficiency by adjusting the flow rate and column temperature [1].

Q2: How do changes in the mobile phase quantitatively affect retention and pressure? Understanding these relationships is key to predictive troubleshooting. The table below summarizes key quantitative rules.

| Parameter Change | Effect on Retention (k) | Effect on System Pressure | Practical Rule of Thumb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease %B by 10% (e.g., 40% → 30% ACN) | Increase | Variable (see viscosity curves) | Retention factor roughly doubles for a typical small molecule [4]. |

| Change Modifier: ACN → MeOH | Decrease (if % kept constant) | Increase | Use ~10% more MeOH than ACN to achieve comparable retention. MeOH/water mixtures are more viscous [4]. |

| Adjust pH for Acids (to below pKa) | Increase | Negligible | Retention increases significantly as acid shifts to neutral form [4]. |

| Adjust pH for Bases (to above pKa) | Increase | Negligible | Retention increases significantly as base shifts to neutral form [4]. |

| Increase Flow Rate | No direct effect on k | Linear Increase | Pressure is proportional to flow rate and mobile phase viscosity (Poiseuille's Law) [4]. |

The following diagram outlines a standard protocol for developing an RPC method, from initial setup to final optimization for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Systematic Protocol for RPC Method Development

In Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), the mobile phase is not merely a carrier but a critical determinant of the success of any analytical method, especially for contaminant separation. Its composition directly governs retention, selectivity, peak shape, and, crucially, ionization efficiency in the mass spectrometer. Within method development, the selection of the organic modifier and the precise control of mobile phase pH stand out as two of the most influential parameters. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to navigate these complex choices, enhance method robustness, and achieve optimal separation for complex matrices.

Organic Modifier Selection: A Strategic Guide

The organic modifier, or "strong" solvent in reversed-phase chromatography, is a primary driver of elution strength and selectivity. Its choice significantly impacts the viscosity, backpressure, UV transparency, and MS-compatibility of the mobile phase [9].

Comparison of Common Organic Modifiers

The table below summarizes the key properties of the three most common organic modifiers to guide initial selection [9] [10].

Table 1: Properties of Common Organic Modifiers in Reversed-Phase Chromatography

| Organic Modifier | Eluotropic Strength | Viscosity | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Medium | Low (0.37 cP) | Low viscosity and backpressure; high UV transparency (to ~190 nm); aprotic [9] [10]. | Higher cost; poorer miscibility with some buffers [9]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Lowest | Higher (0.55 cP) | Lower cost; protic solvent (can offer different selectivity) [9] [10]. | Higher viscosity leading to higher backpressure; higher UV cutoff (~210 nm) [9]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Highest | Medium | Very strong eluotropic and solubilizing power; can resolve challenging isomers [9] [11]. | Toxicity and peroxide formation risk; can damage PEEK tubing; often contains UV-absorbing stabilizers [9]. |

Troubleshooting Organic Modifier Selection

FAQ 1: When should I consider using a less common organic modifier like isopropanol or THF? Isopropanol, ethanol, or THF are valuable when critical impurity pairs remain unresolved after screening methanol and acetonitrile [11]. These solvents, often mixed with ACN or MeOH at ~20%, can produce unique selectivity, especially for non-enantiomeric stereoisomers and positional isomers due to their distinct interaction properties [9] [11].

FAQ 2: My method has high backpressure. Could the organic modifier be the cause? Yes. Methanol-water mixtures can have significantly higher viscosity than acetonitrile-water mixtures, especially at intermediate compositions (e.g., ~50:50) [9]. If backpressure is a concern, switching from methanol to acetonitrile can often resolve the issue, provided the selectivity remains acceptable.

FAQ 3: Why is acetonitrile almost universally preferred for peptide and protein separations by LC-MS? Acetonitrile generally provides sharper peaks and shorter retention times compared to methanol due to its lower viscosity and different mechanism of interaction [10]. This results in higher chromatographic resolution and superior peak capacity, which is critical for separating complex biomolecular mixtures.

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Selectivity Screening

Objective: To identify the optimal organic modifier for separating a complex mixture of contaminants.

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV and/or MS detector

- Standard reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm)

- Test mixture of target contaminants

- HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile, methanol, and tetrahydrofuran

- Mobile phase additives (e.g., 0.1% formic acid)

Method:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare four separate mobile phase systems:

- System A: Water + 0.1% Formic Acid / Acetonitrile + 0.1% Formic Acid

- System B: Water + 0.1% Formic Acid / Methanol + 0.1% Formic Acid

- System C: Water + 0.1% Formic Acid / Tetrahydrofuran + 0.1% Formic Acid (ensure THF is stabilizer-free if using low UV)

- System D: Water + 0.1% Formic Acid / (Acetonitrile:Isopropanol 80:20) + 0.1% Formic Acid

- Chromatographic Conditions: Use a linear gradient from 5% to 95% organic modifier over 30 minutes. Keep flow rate, column temperature, and injection volume constant for all runs.

- Data Analysis: Inject the test mixture with each system. Compare chromatograms based on critical resolution (Rs) of the least-resolved peak pair, overall peak symmetry, and analysis time.

pH Control Strategies: Fundamentals and Troubleshooting

The pH of the mobile phase is a powerful tool for manipulating the retention and selectivity of ionizable compounds, which includes most pharmaceuticals and contaminants. Controlling the pH ensures consistent ionization states, which is fundamental to robust and reproducible methods [9] [12].

The Principle of pH Control

For ionizable analytes, the retention factor (k) is strongly influenced by pH. The general principle is that an analyte is most retained when it is in its neutral, uncharged form because it can better interact with the hydrophobic stationary phase [12] [11].

- For acidic compounds (pKa ~3-5): Lowering the pH (< pKa) suppresses ionization, increasing retention [9].

- For basic compounds (pKa ~8-10): Raising the pH (> pKa) suppresses ionization, increasing retention [9].

- Neutral compounds: Retention is largely unaffected by pH changes.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a mobile phase pH based on analyte properties.

Common Mobile Phase Additives and Buffers

Selecting the right additive is critical for effective pH control and MS compatibility.

Table 2: Common Mobile Phase Additives and Buffers for pH Control

| Additive/Buffer | Effective pH Range | pKa | UV Transparency | MS Compatibility | Key Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | ~2.1 (0.1%) | - | Poor (~210 nm) | Suppresses negative ion mode; can cause ion suppression [9] [11]. | Excellent peak shape for basic compounds; strong ion-pairing reagent [11]. |

| Formic Acid | ~2.8 (0.1%) | 3.75 | Good (cutoff ~210 nm) | Excellent (volatile) [9]. | Very common for LC-MS in positive ion mode [9]. |

| Acetic Acid | ~3.2 (0.1%) | 4.76 | Good (cutoff ~210 nm) | Excellent (volatile) [9]. | Weaker acid than formic acid; less ion-pairing [9]. |

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate | 3.8-5.8 (Acetate) / ~3-5 (Formate) | 4.76 / 3.75 | Moderate (cutoff ~210 nm) | Excellent (volatile) [11]. | Standard volatile buffers for LC-MS; provides some buffering capacity [11]. |

| Phosphate Buffer | ~2.1, 7.2, 12.3 | 2.1, 7.2, 12.3 | Excellent (to ~200 nm) | Not compatible (non-volatile) [9]. | Ideal for LC-UV; three buffering ranges; can precipitate in high organic [9]. |

Troubleshooting pH-Related Issues

FAQ 4: Why do my peaks tail for basic compounds, even at low pH? Peak tailing for basic analytes is often caused by ionic interactions with acidic residual silanols on the silica-based stationary phase [9] [13]. To resolve this:

- Ensure adequate buffering capacity: Use a buffer (e.g., 10-20 mM ammonium formate) instead of a plain acid to more effectively block silanol interactions [9].

- Use additives with ion-pairing properties: Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) or chaotropic reagents like hexafluorophosphate (KPF₆) can mask these secondary interactions and improve peak shape [13] [11].

- Consider a column with higher purity silica or a hybrid organic-inorganic surface, which has fewer acidic silanols [9].

FAQ 5: My retention times are drifting. Could pH be the cause? Yes, retention time drift is a classic symptom of inadequate pH control [11]. This occurs when the mobile phase pH is too close (±1.5 units) to the pKa of an ionizable analyte, where small, unintentional variations in pH cause large changes in the ionization state and thus retention [11]. To fix this, increase the buffer concentration (e.g., from 10 mM to 20-50 mM) and ensure the mobile phase pH is at least 1.5-2.0 units away from the analyte's pKa [11].

FAQ 6: How do I choose between formic acid and acetic acid? The choice depends on the required pH and the application.

- Formic Acid (0.1% ≈ pH 2.8): Provides a lower pH, which is more effective at suppressing analyte ionization and silanol interactions. It is the most common choice for general LC-MS applications in positive ion mode [9].

- Acetic Acid (0.1% ≈ pH 3.2): Provides a milder acidity. It is a good alternative if formic acid causes excessive retention or if a higher pH is needed while still maintaining volatility [9].

Experimental Protocol: Investigating the pH-Retention Relationship

Objective: To map the retention behavior of ionizable contaminants as a function of mobile phase pH.

Materials:

- LC-MS/MS system

- Standard reversed-phase column (stable over a wide pH range, e.g., C18 with hybrid particle technology)

- Test mixture containing acidic, basic, and neutral contaminants

- Volatile buffers at different pH values (e.g., pH 3.0, 4.5, 6.0, 7.5 using formate/ammonium formate and acetate/ammonium acetate systems)

Method:

- Buffer Preparation: Precisely prepare at least four different mobile phase A solutions with buffered pH values covering a relevant range (e.g., 3.0, 4.5, 6.0, 7.5). Use ammonium formate for lower pH and ammonium acetate for mid-range pH. Keep the buffer concentration constant (e.g., 10 mM). Mobile phase B for all systems will be acetonitrile.

- Chromatographic Conditions: Use an isocratic method for simplicity (e.g., 30% B) or a fast, shallow gradient. Keep all other parameters (flow rate, temperature, gradient profile) identical across all pH conditions.

- Data Analysis: For each contaminant in the test mixture, plot the retention factor (k) or retention time against the mobile phase pH. This will reveal the pKa of the analyte and the optimal pH for separation and sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogs key reagents and materials critical for mobile phase optimization in LC-MS/MS.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mobile Phase Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity water, acetonitrile, methanol to minimize background noise and contamination. | Essential for maintaining low chemical background in sensitive MS detection [14]. |

| LC-MS Grade Additives | High-purity formic acid, acetic acid, ammonium acetate, ammonium formate. | Reduces risk of introducing contaminants that cause ion suppression or enhancement [14]. |

| Chaotropic Reagents | e.g., Potassium Hexafluorophosphate (KPF₆), Sodium Perchlorate (NaClO₄). | Improves peak shape for basic compounds without irreversible column modification; not MS-compatible [11]. |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents | e.g., Alkylamines (for oligonucleotides), TFA. | Enables separation of ionic species; TFA is common for peptides/bases; alkylamines for oligonucleotides [15] [11]. |

| Nitrile Gloves | Worn during all mobile phase and sample preparation. | Prevents transfer of keratins, lipids, and other biomolecules from skin, which are common LC-MS contaminants [14]. |

| Syringe Filters (0.22 µm) | For filtering samples and mobile phases (if necessary). | Prevents column clogging; use nylon or PVDF for aqueous/organic mixes; ensure compatibility [16] [10]. |

| Dedicated Glassware | Borosilicate glass bottles for mobile phase storage. | Prevents leaching of contaminants from plastic containers and avoids residual detergents [14]. |

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the Linear Solvent Strength (LSS) Model? The Linear Solvent Strength (LSS) model is a foundational concept in reversed-phase liquid chromatography that describes a linear relationship between the logarithm of the retention factor (k) and the volume fraction of the organic modifier in the mobile phase (C). The relationship is expressed by the equation: log k = log k₀ - S × C [17].

In this equation:

- k is the retention factor at a specific mobile phase composition.

- k₀ is the extrapolated retention factor in pure aqueous mobile phase (C=0).

- S is the solvent strength parameter, a constant for a given compound and set of experimental conditions.

- C is the volume fraction of the organic solvent [17].

LSS gradients, originally developed by Snyder and Dolan, are achieved when the composition of the stronger solvent increases linearly with time, and the isocratic retention of the solute follows this linear relationship [17].

What are the key parameters in LSS theory and how are they calculated? The key parameters for predicting retention behavior are the LSS parameters (log k₀ and S) and the gradient steepness parameter (b). These can be determined through a minimum of two gradient experiments with different gradient times [17].

The following table summarizes the core parameters and their calculation methods.

| Parameter | Description | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|

| LSS Parameters (log k₀, S) | Describe the specific interaction of a compound with the chromatographic system. | Determined from two gradient runs with different gradient times (t𝓰). Plot Cₑ (organic fraction at elution) vs. log s* (normalized gradient slope) [17]. |

| Gradient Steepness (b) | Defines the rate of the solvent strength change during the gradient. | ( b = S \times s^* ) where ( s^* = (t0 \times \Delta C) / tg ) (t₀ is column dead time, ΔC is change in organic modifier, t𝓰 is gradient time) [17]. |

| Retention Factor at Elution (kₑ) | The retention factor of the analyte at the moment it elutes from the column. | ( k_e = 1 / (2.3 \times b) ) (assuming the compound is strongly retained at the initial gradient conditions) [17]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Method Development and Prediction

How can I easily calculate LSS parameters for retention modeling? A simplified mathematical approach requires two initial gradient experiments with different gradient times to determine the retention parameters log k₀ and S [17].

- Perform two gradient runs with different gradient times (t𝓰) for your analyte.

- For each run, determine the organic modifier fraction at elution (Cₑ) and calculate the normalized gradient slope (s*).

- Plot Cₑ versus log s*. The slope (α) and intercept (β) of this linear plot relate to S and log k₀ through: S = 1/α and log k₀ = S × β - log(2.3 × S) [17].

This method is particularly well-suited for large biomolecules like proteins, as their retention behavior is often better described by the linear model compared to small molecules or peptides [17].

What are the critical conditions for accurate retention time predictions using the LSS model? Two critical hypotheses must be met to ensure accurate predictions [17]:

- High Initial Retention: The retention factor at the initial gradient composition (kᵢ) must be large enough (log kᵢ > 2.1 is suggested).

- Linear Retention Model: The relationship between log k and the organic modifier fraction (C) must be sufficiently linear.

When these conditions are not met, retention time predictions can become unreliable. It is usually accepted that the error between predicted and experimental retention times should not be higher than 2% [17].

What is an acceptable error for retention time predictions in gradient elution? For practical purposes, a predicted retention time error of less than 2% is generally acceptable, based on routine industrial practice [17].

A more relevant measure for gradient elution is the parameter λ, which considers the time difference relative to the peak width [17]: ( \lambda = |t{r,predicted} - t{r,experimental}| / w ) where the peak width ( w = (4 \times t_0) / \sqrt{N} \times (1 + 2.3b) / (2.3b) ) and N is the plate number. A maximum λ value of 0.5 is considered the threshold for accurate predictions, as this corresponds to the acceptable 2% error in terms of chromatographic resolution [17].

Common Operational Issues

How can I troubleshoot baseline drift during my gradient methods? Baseline drift in gradient elution with UV detection is often caused by differences in the UV absorbance of the mobile phase components [18].

- Problem: The A and B solvents have different UV absorbance at the detection wavelength, causing the baseline to rise or fall as the proportion changes.

- Solutions:

- Use UV-Transparent Solvents: Acetonitrile often has lower UV absorbance than methanol at wavelengths below 220 nm and is preferred for low-wavelength UV detection [18].

- Add a UV-Absorbing Buffer: Add a buffer like potassium phosphate to the aqueous solvent (A) to match the absorbance of the organic solvent (B). For example, 10 mM potassium phosphate with methanol at 215 nm can produce a nearly flat baseline [18].

- Increase Detection Wavelength: UV absorbance of solvents decreases at higher wavelengths. Increasing the detection wavelength to 254 nm can often minimize or eliminate drift [18].

- Use Compensating Additives: For TFA/acetonitrile gradients used with peptides/proteins, the baseline is flattest at 215 nm. Adding a slight imbalance of TFA (e.g., 0.11% in A and 0.1% in B) can help flatten the baseline at other wavelengths [18].

How do I prevent buffer precipitation in my gradient method? Buffer salts can precipitate in the HPLC system when the organic content becomes too high, leading to pressure fluctuations and blocked fluidics [19].

- Understand Solubility Limits:

- Phosphate buffers start to precipitate at 80% methanol.

- Potassium phosphate buffers start to precipitate at 70% acetonitrile.

- Ammonium phosphate buffers begin to precipitate at 85% organic content [19].

- Best Practices:

- Do not exceed the solubility limit of your buffer in the gradient method.

- For low-pressure gradient (LPG) systems, prepare the strong solvent (B) as a mixture of buffer and organic to avoid 100% organic solvent contacting the buffer solution. For example, use a buffer/organic mixture for channel B and 100% buffer solution for channel A [19].

- Flush the system after using buffers. Never leave a column or HPLC system with buffer inside [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in LSS Method Development |

|---|---|

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | A volatile ion-pairing reagent that acidifies the mobile phase, improving the separation of biomolecules like proteins and peptides. It has low UV absorbance at wavelengths <220 nm [18]. |

| Potassium Phosphate Buffer | A common buffer for reversed-phase LC. It can be added to the aqueous mobile phase to match the UV absorbance of the organic solvent, thereby reducing baseline drift [18]. |

| Ammonium Acetate | A volatile buffer suitable for LC-MS applications. It does not interfere with the mass spectrometry signal and is commonly used with methanol gradients [18]. |

| Formic Acid (FA) | A volatile acidifier used in mobile phases, particularly for LC-MS applications [17]. |

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

Workflow for Determining LSS Parameters and Predicting Retention

The following diagram illustrates the experimental and computational workflow for applying LSS theory to predict retention times, helping to streamline method development.

Critical Method Checks for Reliable LSS Predictions

Before relying on the calculated LSS parameters, it is essential to verify that your system and data meet the necessary conditions for the model's validity.

Modern Trends in Mobile Phase Selection for Pharmaceutical and Environmental Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common modern mobile phases for reversed-phase LC-MS? Modern reversed-phase LC-MS methods predominantly use simpler, binary mobile phase systems for improved robustness and MS-compatibility. The most common organic solvents are acetonitrile and methanol [9]. Acetonitrile is often preferred for its strong eluting power, low viscosity, and good UV transparency, while methanol is a cost-effective alternative, though it generates higher backpressure [9]. For the aqueous phase, volatile additives like formic acid, acetic acid, and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at concentrations of 0.05–0.1% are standard for controlling pH and ensuring MS-compatibility [9].

2. Why does my LC-MS baseline look abnormal, and how can I fix it? An abnormal baseline is a common issue often traced to mobile phase impurities or instrument problems. The table below summarizes causes and solutions [20].

| Baseline Anomaly | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large, broad peak at gradient end | Retained impurities from mobile phase accumulating on-column | Use higher-purity solvents/additives; flush column with strong solvent [20] |

| High, shifting baseline during gradient | UV-absorbing impurities in a mobile phase component | Switch to a different supplier or higher grade of the implicated solvent (e.g., isopropanol) [20] |

| Saw-tooth pattern in baseline | Inconsistent pump flow from a faulty check valve or air bubble | Perform pump maintenance; purge lines to remove air [20] |

| Drifting baseline in UV | Additive (e.g., formate) in only one solvent; changing UV absorbance | Add same additive concentration to both A and B solvents; use higher detection wavelength [20] |

3. How can I reduce background contamination and noise in my LC-MS analysis? Minimizing contamination requires careful attention to solvents and lab practices.

- Solvents and Additives: Use LC-MS grade solvents and additives. Prepare fresh aqueous mobile phases weekly and add at least 5% organic solvent to inhibit microbial growth [14] [21].

- Lab Practice: Wear nitrile gloves to prevent introducing biomolecules like keratins. Avoid using detergents to wash mobile phase bottles, as residues can contaminate the system [14] [21].

- Instrument Setup: Use a divert valve to direct initial column effluent to waste, preventing non-volatile contaminants from entering the MS source [21].

4. What are the emerging trends and future directions in mobile phase selection? The field is moving towards greater automation, sustainability, and intelligence.

- Automation and AI: Machine learning and reinforcement learning are being applied to autonomously optimize chromatographic methods, including complex multi-segment gradients, reducing development time and effort [22] [23].

- Green Solvents: There is a growing push to replace traditional solvents like acetonitrile with greener alternatives. Ethanol-water mobile phases are already widely used, and solvents like acetone, ethyl lactate, and Cyrene are being explored, though challenges with viscosity and UV absorbance remain [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Ghost Peaks and High Background

Problem: Unexplained peaks ("ghost peaks") appear in blank injections, or a consistently high background signal is observed.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Identify the Source: Run a blank injection (e.g., pure water or mobile phase). If ghost peaks persist, the issue is likely in the mobile phase or the LC system itself [20].

- Replace Mobile Phase Components: This is the most common fix.

- Flush the System and Column: Perform a thorough system flush with strong solvents (e.g., high acetonitrile or isopropanol) to elute strongly retained impurities from the column and fluidic paths [21] [25].

- Review Lab Practices: Ensure all personnel wear gloves and use dedicated, clean glassware for mobile phase preparation to prevent contamination from skin, dust, or detergents [14].

Guide 2: Optimizing Mobile Phase for Peak Shape of Basic Analytes

Problem: Peaks for basic compounds exhibit severe tailing.

Investigation and Solutions:

- Use an Acidic Mobile Phase: A low pH (2–4) suppresses the ionization of acidic residual silanols on the stationary phase surface, minimizing undesirable ionic interactions with basic analytes [9].

- Select the Right Additive:

- Consider Column Chemistry: Modern reversed-phase columns are often manufactured with high-coverage bonding and advanced endcapping techniques, which inherently reduce residual silanol activity and improve peak shape for basic compounds [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Systematic Mobile Phase Optimization for a New Compound

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for initial mobile phase optimization suitable for a thesis project on contaminant separation [8].

Step 1: Standard and Solvent Preparation

- Dilute a pure standard of the target compound to a concentration of 50 ppb–2 ppm in a solvent that matches your prospective starting mobile phase (e.g., 50:50 water:acetonitrile) [8].

Step 2: MS/MS Optimization (Infusion Mode)

- Directly infuse the standard solution into the mass spectrometer.

- Identify the parent ion ([M+H]+ or [M-H]-) and optimize the orifice voltage to maximize its signal [8].

- For the optimized parent ion, ramp the collision energy to fragment it. Identify the two most abundant product ions.

- Optimize the collision energy for each of these two MRM transitions—one for quantification, the other for confirmation [8].

Step 3: Liquid Chromatography Optimization

- Column Selection: Start with a C18 column for most non-polar to moderately polar compounds [8].

- Initial Scouting: Test different organic modifiers (methanol vs. acetonitrile) and acidic additives (e.g., 0.1% formic acid) to find conditions that provide adequate retention and a sharp, symmetrical peak.

- Gradient Fine-Tuning: If the compound elutes too early or too late, adjust the gradient profile (e.g., slope, initial and final %B). A slower gradient or a lower initial %B can improve retention and resolution [8].

- Flow Rate and Temperature: Optimize flow rate (e.g., 0.2-0.6 mL/min for 2.1 mm ID columns) and set a uniform column temperature (e.g., 30-40°C) to enhance efficiency and reproducibility [8].

Step 4: Verification

- Run a calibration curve with the optimized method to confirm the detector response is linear and the chromatographic performance is consistent across the concentration range [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Acetonitrile | Low-viscosity, strong eluting power organic solvent; high purity minimizes background noise [9] [21]. |

| LC-MS Grade Water | Aqueous phase base; purchased or from a purification system (<5 ppb TOC) to prevent contamination [21]. |

| Volatile Acids (Formic, Acetic) | MS-compatible additives to acidify mobile phase, improving ionization and controlling retention of ionizable analytes [9]. |

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate | Volatile buffers for precise pH control in MS-compatible methods, often used at 2-10 mM concentrations [9]. |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Protic organic solvent; alternative to acetonitrile for selectivity tuning or cost reduction [9]. |

| Ethanol (HPLC Grade) | A "green" alternative to acetonitrile and methanol; requires consideration of its higher viscosity [24]. |

| Phosphate Salts | For non-MS UV methods requiring highly precise and robust pH control outside the volatile buffer range [9]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Mobile Phase Optimization Workflow

Systematic Method Development: From DoE to Automated Optimization

Design of Experiments (DoE) for Multivariate Optimization of Gradient Parameters

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the first step in a DoE for optimizing a gradient LC-MS/MS method? The first step is a screening design to identify which factors have statistically significant effects on your responses. Using designs with two-factor levels, such as a 2^k full/fractional factorial design or a Plackett-Burman design, is highly recommended at this stage. The resolution of the selected design determines its ability to estimate main effects and interactions between factors [26].

2. Which experimental designs should I use for the final optimization of multiple gradient parameters? For the final optimization stage, designs with three or more factor levels are required to model curvature in the response surface. Excellent choices include [26] [27]:

- Central Composite Design (CCD)

- Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

- Doehlert Design

- D-optimal Design These designs differ in the number of experimental runs required and their statistical properties, such as orthogonality and rotatability. A recent large-scale simulation study indicated that Central Composite Designs often perform best overall for multi-objective optimization of complex systems [27].

3. How can I optimize multiple, sometimes conflicting, responses like resolution and analysis time? A powerful tool for this is the desirability function. This approach mathematically transforms multiple responses into a single, aggregate response (total desirability), allowing you to find a compromise that satisfies all your criteria simultaneously [26].

4. I have both continuous (e.g., temperature) and categorical (e.g., column type) factors. What is a good DoE strategy? A robust strategy is to first use a Taguchi design to identify the optimal levels of your categorical factors and to screen continuous factors in a two-level format. Once the categorical factors are fixed, a Central Composite Design can be employed for the final optimization of the continuous factors [27].

5. My response surfaces are highly non-linear. Can I still use DoE? Yes. When second-order polynomial functions cannot accurately describe the responses, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) can be used. ANNs have been shown to be a better tool for estimating results in cases of significant non-linearity, such as in the optimization of comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) modulators [26].

6. How do I translate a method developed using DoE into a robust routine analysis method? The goal of a thorough DoE is to understand your analytical design space. By applying Quality by Design (QbD) principles and using response surface methodology, you can identify a region of operation where the method is reliable and robust, reducing and controlling sources of variability. Simulation software can help investigate this space thoroughly with limited resources [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Peak Resolution After Optimization

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Model Fit | Check R² and prediction plots from your software. Run a confirmation experiment at the predicted optimum. | Use a higher-order model (e.g., ANN) or expand the experimental domain and use a CCD to better capture curvature [26]. |

| Overlooked Critical Factor | Review the screening results for factors just below the significance threshold. | Re-run the screening design, including the potentially overlooked factor (e.g., solvent pH or additive concentration) [29]. |

| Factor Interaction Effects | Examine interaction plots in your statistical software. | Use a full factorial or higher-resolution fractional factorial design during screening to account for interactions [26]. |

Problem: High Prediction Error in the Optimized Region

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Experimental Runs | Check the model's degrees of freedom and power. | Increase the number of experimental points. A Central Composite Design is often more reliable than a 3^k full factorial for building a quadratic model with fewer runs [26] [27]. |

| High Experimental Variance | Replicate center points to estimate pure error. | Improve experimental control (e.g., use more precise HPLC pumps, temperature control). Increase the number of replicates to better estimate error [28]. |

Problem: The Optimized Method is Not Robust During Validation

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp Optimum | Examine response surfaces; a steep peak indicates small changes cause large effects. | Use the desirability function to find a region with a "flat peak" where the response is acceptable over a wider range of factor levels, ensuring robustness [28]. |

| Uncontrolled Categorical Factor | Check if a non-optimized factor (e.g., column batch, instrument) is causing drift. | Use a DoE strategy that incorporates categorical factors, like first applying a Taguchi design to lock in the best level of these factors before final optimization [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key DoE Applications

Protocol 1: Optimizing a Gradient LC-MS/MS Method for Micropollutants Using RSM

This protocol is adapted from an study optimizing Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) and LC-MS/MS conditions for pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and UV filters [29].

- Objective: To simultaneously maximize extraction efficiency (EE), minimize matrix effect (ME), and maximize absolute recovery (AR) for 32 micropollutants.

- Experimental Design: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) using a Central Composite Design.

- Key Factors (Variables):

- Sample pH (continuous)

- Sample Volume (continuous)

- Eluent Volume (continuous)

- Responses: EE (%), ME (%), AR (%).

- Methodology:

- Screening: Prior to RSM, use a fractional factorial design to confirm these are the most significant factors.

- RSM Execution: Run the experiments as dictated by the CCD.

- Model Fitting: Fit the data to a second-order polynomial model. If model fit is poor, use parametric analysis or alternative models.

- Multi-Response Optimization: Use a desirability function to find the optimal compromise between EE, ME, and AR.

- Validation: The optimized conditions (sample pH of 3–4, volume of 375 mL, 3.5 mL ethanol eluent) were successfully validated for routine monitoring [29].

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Gradient Profile for Phenolic Compounds in Coffee

This protocol uses a novel statistical criterion for gradient optimization in HPLC-MS/MS [30].

- Objective: Develop a reversed-phase HPLC method to characterize dynamic changes in phenolic compounds during coffee roasting.

- Experimental Design: A new approach combining three statistical criteria.

- Key Factors: Gradient profile parameters (initial time, final time, shape).

- Responses:

- Interquartile range of gradient retention times.

- Probability of MS time-window overlapping.

- Total gradient time range.

- Methodology:

- Data Collection: Run preliminary gradients to gather retention time data.

- Summary Criterion: Calculate a "gradient score" by applying different weights to the three statistical criteria.

- Visual Optimization: Propose optimal conditions using a heatmap diagram to visualize the gradient scores across different conditions [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and software solutions used in modern chromatographic method development and optimization.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ion Exchange Resins | For protein purification and separation of biomolecules; packing stability is critical for process performance [31]. |

| Cyanopropyl Polysilphenylene-siloxane Stationary Phase | A specific polar phase used in GC for enhancing the separation of complex mixtures like fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) [26]. |

| Ionic Liquid Stationary Phases | Used in GC for their highly temperature-dependent polarity, offering unique selectivity for challenging separations [26]. |

| DryLab Software | A popular modeling software for chromatographic separations, known for its 3D modeling capabilities [28]. |

| ACD/LC Simulator & ACD/GC Simulator | Instrument vendor-agnostic software for retention-based modeling; allows for custom model creation and predicts behavior based on logD and pKa [28]. |

| ChromSword | Software that provides automation through instrument control and includes physicochemical property predictions to aid method development [28]. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Software | (e.g., custom code in Python, R, or MATLAB). Used to model highly non-linear response surfaces where traditional polynomial models fail [26]. |

DoE Selection and Application Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying a Design of Experiments strategy for gradient optimization.

DoE Selection and Application Workflow

Key DoE Designs for Chromatography Optimization

This table summarizes the primary experimental designs used in chromatographic method development, highlighting their characteristics and applications.

| DoE Design | Primary Phase | Key Characteristics | Best Use Case in Chromatography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plackett-Burman | Screening | Saturated design, estimates main effects only with few runs. | Initial identification of critical factors from a large set (e.g., pH, temp, gradient time, flow rate) [26]. |

| 2^k Factorial | Screening | Full or fractional; estimates main effects and some interactions. | Understanding the influence of factors and their interactions on resolution and analysis time [26]. |

| Central Composite (CCD) | Optimization | 3-5 levels, rotatable, excellent for fitting quadratic models. | The gold standard for response surface optimization; works well for 2-4 critical factors [26] [27] [29]. |

| Box-Behnken (BBD) | Optimization | 3 levels, spherical, fewer runs than CCD for 3+ factors. | A efficient alternative to CCD when a factorial design is too costly to run [26]. |

| D-Optimal | Optimization | Computer-generated, optimal for constrained design spaces. | Useful when the experimental region is irregular or when there are mixture constraints [26]. |

| Taguchi | Screening/Optimization | Robust design, uses inner/outer arrays for noise. | Efficiently handling categorical factors (e.g., column type, solvent brand) early in the optimization process [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I use RSM instead of a simple "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach for my LC-MS/MS method development?

RSM is designed to find the optimal combination of factor levels that might be missed by an OFAT approach. In the context of LC-MS/MS, factors like the initial mobile phase composition (φ_in), gradient time (t_G), and initial isocratic time (t_in) can interact in complex ways that jointly influence both separation efficiency and matrix effects [32]. RSM systematically explores these interactions with a reduced number of experiments, providing a mathematical model that predicts the optimal balance between a high-quality separation and the minimization of ion suppression/enhancement [33] [34].

FAQ 2: How can RSM specifically help me reduce matrix effects in my LC-MS/MS analysis?

While RSM itself does not eliminate matrix effects, it is a powerful tool for optimizing chromatographic conditions to separate the analyte of interest from co-eluting matrix components that cause ion suppression or enhancement [35]. By modeling the relationship between LC gradient parameters and the chromatographic response (e.g., peak shape, resolution, and retention time), RSM can help you identify conditions where your analyte elutes in a "clean" region of the chromatogram, away from the matrix interferences revealed by techniques like post-column infusion [35].

FAQ 3: I have found the optimal conditions for my extraction, but my LC-MS/MS signal is still suppressed. What should I check?

This is a classic sign that the optimization was likely performed with pure standards and did not account for the complex sample matrix. You should:

- Re-evaluate the Chromatogram: Use the post-column infusion method to identify the retention time zones in your chromatogram that experience significant ion suppression [35].

- Re-optimize with the Matrix: Re-formulate your RSM experiment to include the matrix. The response variable should not just be extraction yield, but also a measure of signal suppression (e.g., the ratio of the signal in matrix to the signal in pure solvent) [35].

- Adjust Factor Ranges: The optimal chromatographic conditions for a pure standard may differ from those for an extract. You may need to adjust the factor ranges (e.g., gradient slope, initial organic percentage) in your RSM design to find a new optimum that moves the analyte away from suppression zones.

FAQ 4: My RSM model shows a high R-squared, but the predictions are poor when I run confirmation experiments. What went wrong?

A high R-squared does not guarantee a good model. The issue likely lies in one of these areas:

- Inadequate Model: The system might have curvature that your first-order model cannot capture. You may need to use a design that supports a second-order (quadratic) model, such as a Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD) [36] [34] [37].

- Violated Statistical Assumptions: The regression analysis used in RSM assumes normality, independence, and homogeneity of variance of the residuals [34]. You should perform a residual analysis to check for these assumptions. Significant violations may require a transformation of your response data (e.g., a logarithmic transformation) [34].

- Lack of Fit: The model may not correctly represent the relationship between factors and the response. The statistical output of your RSM analysis should include a "lack-of-fit" test—a significant p-value for this test indicates the model is inadequate [36] [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RSM Problems in LC-MS/MS Optimization

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common RSM Implementation Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Model Fit | The relationship between variables is highly non-linear or complex [38]. | Switch from a first-order to a second-order model (e.g., use CCD or BBD) [36] [34]. Consider transforming the response variable or using advanced modeling techniques like Support Vector Machines (SVM) [32]. |

| Failure to Find a True Optimum | The deterministic optimization technique used converged to a local optimum, not the global one [39]. | Use metaheuristic algorithms (e.g., Differential Evolution) in the optimization phase to better navigate complex response surfaces and escape local optima [39]. |

| High Sensitivity to Small Changes | The operating conditions are "robust," meaning the response is very sensitive to minor, uncontrollable variations in factor levels. | Use RSM to perform a Robust Parameter Design. Incorporate noise factors (e.g., different matrix lots, column ages) into your experimental design to find factor settings that make your method insensitive to these variations [33]. |

| Model Does Not Validate | The region of experimentation was too narrow, or critical factors were omitted during initial screening [33]. | Return to the screening phase. Use a fractional factorial design to efficiently identify the most influential factors before proceeding to a full RSM optimization [33] [34]. |

| Unpredictable Matrix Effects | The composition of the sample matrix is highly variable, causing shifting suppression zones. | Use the post-column infusion method with several different lots of the matrix to map consistent "clean" elution windows. Optimize your gradient to elute analytes in these stable zones [35]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Using Post-Column Infusion to Map Matrix Effects for RSM

Purpose: To qualitatively identify regions of ion suppression/enhancement in your chromatographic method, providing critical information for defining the goal of your RSM optimization [35].

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental setup and workflow for the post-column infusion method.

Procedure:

- Setup: Configure the LC-MS/MS system as shown in the diagram. The syringe pump delivers a constant infusion of your analyte standard.

- Inject: Inject a processed blank matrix extract from your sample preparation workflow.

- Run & Observe: Run the chromatographic method. The mass spectrometer will detect a steady analyte signal from the post-column infusion, except when co-eluting matrix components from the injected blank extract cause ion suppression or enhancement.

- Analyze: The resulting chromatogram will show a steady baseline where no matrix effects occur. Dips in the signal indicate regions of ion suppression, and peaks indicate ion enhancement [35]. Use this map to define the retention time windows your RSM optimization must avoid.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Central Composite Design (CCD) for Gradient Optimization

Purpose: To empirically build a second-order (quadratic) model that accurately describes the relationship between key LC gradient factors and your critical responses (e.g., resolution, analysis time, signal-to-noise ratio) [34] [37].

Methodology:

- Select Factors and Ranges: Based on preliminary screening, choose 2-4 critical factors. For gradient optimization, common factors are:

t_G: Gradient time (e.g., from 10 to 30 min)φ_in: Initial mobile phase composition (e.g., from 5% to 15% organic)t_in: Initial isocratic hold time (e.g., from 0 to 2 min)

- Code the Factors: Scale and center each factor to coded levels (-1, 0, +1) to make the analysis unitless and the coefficients comparable [36].

- Generate the Design: A CCD consists of three parts:

- Run Experiments: Execute the LC-MS/MS runs in a randomized order to avoid bias.

- Model and Analyze: Fit a quadratic model to the data using regression analysis. The model will take the form [37]:

Y = β₀ + β₁A + β₂B + β₁₁A² + β₂₂B² + β₁₂AB + εUse Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to check the model's significance and lack-of-fit.

Table 2: Example of a 2-Factor Central Composite Design (CCD) Matrix for Gradient Optimization

| Standard Order | Run Order | Factor A: Gradient Time (t_G), Coded |

Factor B: Initial %Organic (φ_in), Coded |

Response: Resolution of Critical Pair |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | -1 | -1 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 1 | +1 | -1 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 5 | -1 | +1 | 1.8 |

| 4 | 7 | +1 | +1 | 2.1 |

| 5 (Center) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 |

| 6 (Center) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 |

| 7 (Axial) | 3 | -α | 0 | 1.3 |

| 8 (Axial) | 6 | +α | 0 | 2.0 |

| 9 (Axial) | 9 | 0 | -α | 1.1 |

| 10 (Axial) | 10 | 0 | +α | 2.2 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for RSM in LC-MS/MS Method Development

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Standard (Pure) | Used to establish baseline MS response and for post-column infusion experiments to map matrix effects [35]. | Should be of high purity (>95%). Prepare stock solutions in an appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) and store at recommended conditions. |

| Blank Matrix | A real sample matrix that does not contain the target analyte. Used for post-extraction spiking and for preparing matrix-matched calibration standards [35]. | Sourcing can be challenging. The goal is to find a matrix that is as representative as possible of the real samples. |

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (IS) | Added to both standards and samples to compensate for variability in sample preparation and matrix effects during MS analysis [35]. | The ideal IS is the analyte labeled with a stable isotope (e.g., ¹³C, ²H). It should co-elute with the analyte and have nearly identical chemical behavior. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Used to prepare mobile phases and standard solutions. | Use low-UV absorbing, LC-MS grade solvents and high-purity water to minimize background noise and contamination. |

| Buffers and Additives | Modify the mobile phase to control pH and improve chromatography (e.g., ammonium formate, formic acid). | Use volatile buffers compatible with MS detection. Avoid non-volatile salts (e.g., phosphate buffers) which can clog the MS source. |

Bayesian Optimization Algorithms for Closed-Loop Gradient Design

Technical FAQ: Core Algorithm Principles

What is Bayesian Optimization (BO) and why is it suitable for closed-loop LC-MS/MS gradient design?

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sequential, model-based strategy for globally optimizing black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate. It is particularly suited for closed-loop LC-MS/MS gradient design because it can find optimal methods with a minimal number of experimental runs, which is crucial when dealing with complex samples and time-consuming analytical procedures. The core of BO lies in using a probabilistic surrogate model, typically a Gaussian Process (GP), to approximate the unknown objective function (e.g., a chromatographic resolution metric). An acquisition function then uses this model to guide the selection of the next experiment by balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of known promising areas [40] [41] [42]. This allows the automated system to efficiently navigate the multi-dimensional parameter space of gradient conditions (e.g., gradient time, slope, temperature) to maximize separation performance for contaminant analysis.

What are the main components of the Bayesian Optimization framework?

The BO framework consists of four key components [41]:

- Experiments: The wet-lab or in silico system that generates data. In LC-MS/MS, this is the chromatographic system itself.

- Surrogate Model: A probabilistic model that approximates the black-box objective function. Gaussian Processes are the most common choice.

- Acquisition Function: A function that determines the next experiment by evaluating the potential utility of candidate points based on the surrogate model's predictions.

- Termination Criterion: A pre-defined rule to stop the optimization loop, such as a maximum number of iterations or convergence in performance.

What is the difference between Single-Objective and Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization?

- Single-Objective Bayesian Optimization is designed to find the optimum for a single performance metric, for example, maximizing the overall chromatographic resolution [43].

- Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization is used when multiple, often competing, objectives need to be balanced. In the context of LC-MS/MS, this could involve simultaneously maximizing the resolution while minimizing the total run time. This approach explores the trade-offs between these objectives, revealing a set of optimal solutions known as the Pareto front, from which a researcher can choose based on their priorities [43] [44].

How does Multi-Task Bayesian Optimization (MTBO) enhance LC×LC method development?

Multi-Task Bayesian Optimization is a powerful extension that leverages information from related tasks to accelerate the primary optimization goal. For complex comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography (LC×LC) separations, MTBO can combine data from both experimental measurements and computational retention modeling. The retention model provides an approximate, inexpensive source of information, while the experiments provide accurate but costly data. By using both, MTBO can find better optima with fewer experimental iterations compared to standard BO, which is especially valuable when dealing with a high number of adjustable parameters [44].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: The algorithm fails to find a satisfactory separation within a reasonable number of iterations.

- Potential Cause: The problem dimensionality is too high. BO's performance can deteriorate in very high-dimensional spaces (e.g., >20 parameters) due to the "curse of dimensionality," where the volume of the search space grows exponentially, making it difficult to model and explore effectively [45] [46].

- Solution:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Reduce the number of parameters being optimized. Use prior knowledge to fix less influential variables.

- Leverage Problem Structure: Apply BO methods that assume a lower-dimensional underlying structure, such as sparsity (where only a few parameters are truly important) or axis-aligned subspaces [45] [46].

- Use MTBO: Incorporate retention modeling as a source of information to guide the optimization more efficiently [44].

Issue: The optimization process appears noisy and unstable, suggesting high experimental variance.

- Potential Cause: The objective function is unstable due to measurement errors or system variability inherent in the chromatographic system and biological samples [45] [41].

- Solution:

- Robust Modeling: The Gaussian Process surrogate model inherently provides a form of "probabilistic smoothing," which can statistically account for uncaptured variations in the measurements [45].

- Improved DoE: Ensure high-quality initial data by using space-filling experimental designs (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) for the excitation experiments. Randomize samples and minimize batch-to-batch variability to reduce the impact of nuisance factors [41].

- Noise Characterization: Explicitly model the noise in the GP surrogate if its characteristics are known.

Issue: The algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum and does not explore the parameter space sufficiently.

- Potential Cause: The acquisition function is over-exploiting known good regions and lacks exploration.

- Solution:

- Tune Acquisition Function: Adjust the parameters of the acquisition function. For example, in the "Probability of Improvement," increasing the

ϵparameter promotes more exploration [40]. - Change Acquisition Function: Switch to an acquisition function that naturally balances exploration and exploitation more effectively for your problem, such as Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [40] [41].

- Hybrid Sampling: Use an optimization strategy that combines sampling from quasi-random points with local perturbations of the best-performing points to enforce a more explorative behavior [46].

- Tune Acquisition Function: Adjust the parameters of the acquisition function. For example, in the "Probability of Improvement," increasing the

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Closed-Loop BO for LC-MS/MS Gradient Optimization

The following workflow provides a detailed methodology for setting up a closed-loop Bayesian Optimization experiment for mobile phase gradient design.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Optimization Goal and Parameters:

- Objective Function: Formally define the quantitative metric to be optimized. For contaminant separation, this is often a measure of chromatographic resolution, such as the minimum resolution between any two peaks of interest or the peak capacity.

- Design Variables: Identify the key gradient parameters to be optimized. For a binary gradient, this typically includes:

- Initial and final %B concentration

- Gradient time (

t_G) - Gradient shape (linear, multi-segmented)

- Temperature

- Flow rate

Initial Experimental Design (Excitation Design):

- Perform initial experiments to build the first surrogate model.

- Use a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or a Sobol sequence to cover the defined parameter space as evenly as possible with a small number of runs (e.g., 10-20 experiments) [41].

- This step is critical for providing a good initial belief about the objective function.

Execute Closed-Loop Optimization:

- Follow the workflow outlined in the diagram above. For each iteration:

- The LC-MS/MS system runs the experiment with the specified gradient parameters.

- The resulting chromatogram is analyzed, and the objective function (e.g., resolution) is computed.

- This new data point is added to the observation set.

- The Gaussian Process surrogate model is updated (re-trained) to form a new posterior distribution of the objective function.

- The acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) is optimized over the parameter space to propose the next set of gradient conditions.

- This loop continues autonomously until a termination criterion is met.

- Follow the workflow outlined in the diagram above. For each iteration:

Termination:

- The loop stops when a pre-set condition is satisfied. Common criteria include:

- A maximum number of iterations (e.g., 30-50 runs) is reached [43].

- The improvement in the objective function over a set number of iterations falls below a defined threshold.

- A satisfactory separation performance is achieved.

- The loop stops when a pre-set condition is satisfied. Common criteria include:

Key Optimization Parameters and Software Tools

Table 1: Summary of Key Parameters for BO in LC-MS/MS Gradient Optimization

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Description & Role in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| BO Algorithm | Surrogate Model | Gaussian Process (GP) is standard; defines how the objective function is modeled. |

| Acquisition Function | Expected Improvement (EI) is common; balances exploration vs. exploitation. | |

| Initial Sample Number | Typically 10-20 space-filling points (e.g., via LHS) to initialize the GP model [41]. | |

| Gradient Parameters (Examples) | Gradient Time (t_G) |

A primary optimization variable; critically impacts resolution and run time. |

| %B Start/End | Defines the elution strength range of the mobile phase gradient. | |

| Gradient Shape | Can be extended to complex forms like multi-segmented or shifting gradients [44]. | |

| Temperature | Can be co-optimized with gradient parameters for additional selectivity control. | |

| Termination Criteria | Max Iterations | Stops the loop after a budget is consumed (e.g., 35 runs) [43]. |

| Performance Threshold | Stops when the objective function exceeds a target value. | |

| Convergence Criterion | Stops when performance improvement plateaus. |

Table 2: Selected Software Packages for Implementing Bayesian Optimization

| Package Name | Key Features | License |

|---|---|---|

| BoTorch [42] | Built on PyTorch; flexible framework for modern BO research. | MIT |

| Ax [42] | Modular platform built on BoTorch; suitable for large-scale experiments. | MIT |

| GPyOpt [42] | Accessible BO library based on GPy. | BSD |

| Scikit-Optimize [42] | Features simple and efficient BO tools. | BSD |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LC-MS/MS Method Development

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analytical Standard Mix | Contains known concentrations of target contaminants; used to establish retention times and optimize separation. |

| Mobile Phase A | Typically a water-based buffer with volatile additives (e.g., formic acid); weak elution strength. |

| Mobile Phase B | Typically an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) with volatile additives; strong elution strength. |

| Stationary Phase Columns | The LC column (e.g., C18); its chemistry is the primary determinant of selectivity and retention. |

| Calibration Standards | Used to characterize the measurement noise and response of the MS/MS detector, which can be incorporated into the BO model [41]. |

Pentafluorophenyl (PFP) stationary phases represent a versatile tool in liquid chromatography, particularly for methods requiring the separation of analytes with a wide range of polarities. Unlike conventional C18 columns, which separate compounds primarily through hydrophobic interactions, PFP phases offer multiple retention mechanisms. These include hydrophobic interactions, π-π interactions, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding [47] [48]. This multi-modal retention capability enables the effective separation of complex mixtures, including structural isomers and compounds with diverse physicochemical properties, which are often challenging to resolve using standard reversed-phase columns.

The unique selectivity of PFP columns makes them exceptionally valuable in LC-MS/MS research, especially in the analysis of pharmaceuticals, metabolites, and environmental contaminants. The presence of the electronegative fluorine atoms on the phenyl ring creates a strong dipole moment, enhancing interactions with compounds containing aromatic systems or electron-donating groups [48]. Furthermore, the propyl spacer chain in pentafluorophenylpropyl (PFPP) columns provides additional stability and reduces steric hindrance, allowing for more efficient interactions with analytes [47] [49]. This article provides a comprehensive technical guide for scientists utilizing PFP columns within the context of optimizing mobile phase gradients for contaminant separation in LC-MS/MS.

Key Advantages and Retention Mechanisms

Multi-Modal Retention for Challenging Separations

The principal advantage of PFP columns lies in their ability to exploit multiple interaction modes with analytes. This multi-modal mechanism provides superior selectivity for compounds that are poorly resolved on traditional C18 columns.

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Like C18 phases, the PFP ligand provides a hydrophobic surface for partitioning, retaining non-polar compounds [48].

- π-π Interactions: The pentafluorophenyl ring can engage in π-π interactions with analytes containing aromatic rings. The electron-deficient fluorinated ring is particularly effective at interacting with electron-rich aromatic systems, offering a distinct selectivity difference from standard phenyl columns [48].

- Dipole-Dipole Interactions: The strong dipole moment created by the fluorine atoms enables strong interactions with polarizable analytes or those possessing permanent dipole moments [48].

- Charge-Assisted Interactions: The stationary phase can participate in hydrogen bonding or ionic interactions with charged or neutral analytes, especially when using specific mobile phase additives [48].

Application in Resolving Critical Pairs

This multi-modal retention is particularly effective for resolving critical pairs of isomers and metabolites with similar structures. Research has demonstrated that PFP columns can successfully resolve challenging pairs such as isoleucine/leucine, malate/fumarate, and malonyl-CoA/3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, which are often difficult to separate with HILIC or standard reversed-phase columns [47]. This capability is invaluable in metabolomics and pharmaceutical impurity profiling, where precise identification and quantification of individual isomers is crucial.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Operational Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Peak Shape for Basic Analytes | - Ionic interactions with residual silanols- Incorrect mobile phase pH | - Use acidic mobile phase (pH ~2-4) to suppress silanol ionization [9]- Incorporate mobile phase additives like ammonium acetate or fluoroalcohols [48] |

| Insufficient Retention of Polar Compounds | - Mobile phase too strong (high organic%)- Lack of appropriate secondary interactions | - Start with a higher aqueous percentage (e.g., 95-98% aqueous phase) [47]- Utilize mobile phase additives that can modulate selectivity (e.g., fluoroalcohols) [48] |

| High Backpressure | - Blocked column frit- Mobile phase viscosity | - Use in-line filters and guard columns- For methanol/water mobiles, consider switching to acetonitrile for lower viscosity [9] |

| Irreproducible Retention Times | - Mobile phase pH not controlled- Inadequate column equilibration | - Use a buffered mobile phase (e.g., formate, acetate) within ±1 pH unit of its pKa [50] [9]- Allow for sufficient equilibration time between gradient runs |

| Low MS Signal | - Ion suppression from co-eluting compounds- Non-volatile mobile phase components | - Improve separation to reduce co-elution [47]- Use volatile additives (formic acid, ammonium acetate) and avoid phosphates [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a PFP column over a standard C18 column for my LC-MS/MS method? A PFP column is preferable when dealing with complex mixtures containing structural isomers, heterocyclic compounds, or analytes with a broad range of polarities. If you encounter poor resolution on a C18 column, especially for compounds with aromatic rings or those capable of dipole-dipole interactions, a PFP column offers an alternative selectivity that often resolves these challenges [47] [49].

Q2: Can I use highly organic mobile phases with PFP columns? Yes, one of the documented advantages of PFPP columns is their ability to retain analytes even with mobile phases containing high concentrations (e.g., 90%) of organic solvents like acetonitrile. This is beneficial for MS detection as it promotes easy desolvation and enhances signal intensity [49].

Q3: What mobile phase additives are recommended for PFP columns in LC-MS/MS? Volatile additives are essential for LC-MS/MS compatibility. Common choices include:

- Acids: Formic acid (0.1%) or Trifluoroacetic acid (0.01-0.05%) for low-pH methods [9].

- Buffers: Ammonium formate or ammonium acetate (5-20 mM) for pH control [47] [9].