Correcting for Cation Exchange in Groundwater Studies: Methods, Challenges, and Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and environmental scientists on addressing cation exchange processes in groundwater quality assessments.

Correcting for Cation Exchange in Groundwater Studies: Methods, Challenges, and Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and environmental scientists on addressing cation exchange processes in groundwater quality assessments. It covers the foundational principles of how cation exchange capacity (CEC) and exchange reactions influence hydrogeochemistry, explores advanced field and laboratory techniques for characterization, addresses common challenges in complex geological settings, and validates methods through case studies and comparative analysis. By integrating geostatistical modeling, improved CEC determination methods, and multi-parameter validation frameworks, this work establishes robust protocols for accurately interpreting groundwater quality data and managing aquifer resources.

Understanding Cation Exchange: Core Principles and Its Impact on Groundwater Geochemistry

Defining Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) and Base Cations in Aquifer Systems

Definitions and Core Concepts

What is Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) in the context of an aquifer?

Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) is a fundamental property of subsurface materials, measuring the total capacity of aquifer solids to hold and exchange positively charged ions (cations) [1] [2] [3]. It is defined as the amount of positive charge that can be exchanged per mass of solid material, typically expressed in milliequivalents per 100 grams (meq/100g) or centimoles of charge per kilogram (cmol+/kg) [4] [3]. In aquifer systems, this exchange occurs on the negatively charged surfaces of clay minerals and organic matter present in the porous media, which electrostatically attract and retain cations from the surrounding groundwater [2] [4].

What are base cations and how are they distinguished?

Base cations are the group of non-acidic, plant-nutrient cations that includes calcium (Ca²⁺), magnesium (Mg²⁺), potassium (K⁺), and sodium (Na⁺) [1] [2] [3]. These are distinguished from acid cations such as hydrogen (H⁺) and aluminum (Al³⁺) [1] [5]. The term "base" in this context refers to their non-acidic character, not to be confused with bases in the strict chemical sense [3]. In groundwater studies, the balance between these cation groups significantly influences water quality parameters, including pH and hardness.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Methodology for Determining Effective CEC in Aquifer Sediments

This protocol describes the summation method for determining the effective CEC, which reflects the actual field conditions of the aquifer material [3].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect saturated sediment cores using appropriate drilling and sampling techniques to preserve in-situ conditions.

- For unconsolidated aquifers, separate the fine earth fraction (<2 mm) for analysis [4].

- Record the native pH of the sediment-pore water mixture.

2. Cation Extraction and Measurement:

- Extract base cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺) using an appropriate extraction method such as Mehlich I (for acidic, low-CEC soils) or ammonium acetate [1] [6].

- Analyze the extractant using atomic absorption spectroscopy or ICP-MS to determine cation concentrations in parts per million (ppm) or milligrams per liter (mg/L).

3. Conversion to Charge Units:

- Convert concentration values to milliequivalents per 100 grams (meq/100g) using established conversion factors based on atomic weight and valence [5].

Table: Conversion Factors for Base Cations

| Base Cation | Atomic Weight | Valence | Conversion Factor (meq/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | 40 | 2 | 200 |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺) | 24 | 2 | 120 |

| Potassium (K⁺) | 39 | 1 | 390 |

| Sodium (Na⁺) | 23 | 1 | 230 |

4. Calculation of Effective CEC (ECEC):

- Calculate the sum of base cations: Total Base Cations = Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺ + K⁺ + Na⁺ (all in meq/100g) [4].

- For sediments with pH < 7.0, include exchangeable acidity (H⁺ + Al³⁺), typically determined via buffer pH methods [5].

- Effective CEC = Sum of Base Cations + Exchangeable Acidity [5].

Advanced Protocol: Mapping Regional Groundwater Redox and Cation Exchange Conditions

This innovative two-step GIS methodology enables regional-scale mapping of cation exchange conditions [7].

1. Geostatistical Analysis and Interpolation:

- Compile groundwater quality data from monitoring wells (e.g., Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, Fe, NO₃⁻, Na⁺, Mg²⁺).

- Perform Empirical Bayesian Kriging in ArcGIS or similar software to create continuous surfaces of each parameter.

2. Data Integration and Classification:

- Combine interpolated variables using conditional functions in ArcMap's Math toolbox.

- Classify cation exchange conditions based on established hydrochemical criteria.

- Validate the model by comparing predicted versus observed conditions (target: 75-95% agreement) [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting CEC Measurements in Groundwater Studies

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Discrepant CEC values | Different extraction methods (e.g., Mehlich 3 vs. ammonium acetate) [6] | Use consistent extraction methods for both CEC and cation measurements [6]. |

| Base saturation >100% | High calcium carbonate content; method mismatch [6] | Use acid pretreatment to remove carbonates; ensure methodological consistency [6]. |

| Poor model performance | Measurement error in calibration data [8] | Increase sample size; use measurement error variance to correct predictions [8]. |

| Rapid pH decline in low-CEC aquifers | Low buffer capacity against acidification [1] [4] | Monitor pH more frequently; consider different buffering strategies. |

Impact of Measurement Error on Pedotransfer Functions (PTFs)

Measurement error in CEC calibration data significantly impacts PTF performance [8]:

- Random Forest models are particularly sensitive, with Model Efficiency Coefficient (MEC) potentially decreasing by 1.52-31.59% [8].

- Smaller calibration datasets magnify the impact of measurement error [8].

- Solution: Use larger calibration datasets (>100 samples) and account for measurement error variance in model calibration [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does CEC affect contaminant transport in aquifer systems?

CEC significantly influences the retention and mobility of cationic contaminants (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) in groundwater systems [3]. Aquifer materials with higher CEC can retard the movement of these contaminants through adsorption and exchange processes, potentially extending remediation timeframes but reducing the spread of contamination.

Why does CEC vary with pH in aquifer systems?

CEC is pH-dependent because some negative charges on mineral surfaces arise from the deprotonation of hydroxyl groups [1] [3]. As pH increases, more deprotonation occurs, creating more negative charges and increasing CEC. This is particularly significant for organic matter and certain clay minerals, while other clays maintain a relatively constant "permanent charge" regardless of pH [3].

What are typical CEC values for different aquifer materials?

Table: Typical CEC Values for Various Geologic Materials

| Material Type | Typical CEC Range (meq/100g) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Sand | 1-5 [1] [5] | Low nutrient retention, rapid contaminant transport |

| Kaolinite clay | 3-15 [1] | Common in weathered sediments, lower CEC |

| Illite clay | 15-40 [1] | Intermediate CEC capacity |

| Montmorillonite clay | 80-100 [1] | High swelling capacity, excellent contaminant retention |

| Organic matter | 200-400 [1] [4] | Extremely high CEC, significant even in small quantities |

How does base saturation relate to groundwater quality?

Base saturation represents the percentage of the CEC occupied by base cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺) rather than acid cations (H⁺, Al³⁺) [1] [5]. Higher base saturation typically correlates with:

- Higher pH values, reducing metal mobility [1]

- Greater abundance of essential cations [1]

- Reduced concentrations of toxic Al³⁺, which is particularly important in acidic groundwater systems [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents for CEC and Base Cation Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium acetate (1M, pH 7) | Index ion for direct CEC measurement [3] | Standard method for potential CEC; may not reflect field conditions for variable-charge soils. |

| Mehlich I extractant | Acidic extracting solution for base cations [1] | Suitable for acidic, low-CEC soils; check compatibility with local aquifer geology. |

| Barium chloride | Alternative index ion for CEC determination [3] | Used in some standardized methods. |

| Buffer solutions (various pH) | For determining exchangeable acidity [5] | Essential for estimating H⁺ and Al³⁺ in effective CEC calculations. |

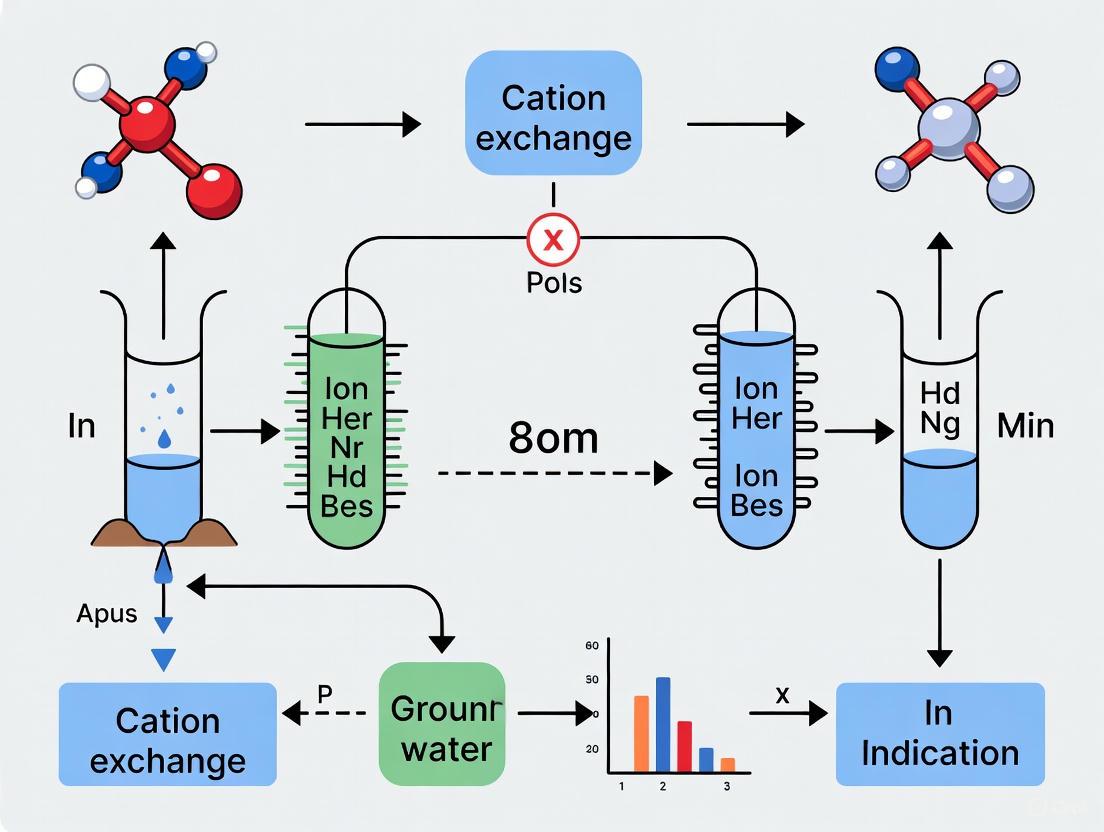

Conceptual Diagram of Cation Exchange in Aquifer Systems

Cation Exchange Dynamics in Aquifer Systems

Experimental Workflow for Aquifer CEC Characterization

Aquifer CEC Characterization Workflow

The Fundamental Role of Water-Rock Interactions in Hydrogeochemical Evolution

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Key Research Challenges

FAQ: How do I distinguish between different water-rock interaction processes in my groundwater data?

Issue: Your hydrochemical data shows elevated ion concentrations, but the dominant water-rock process (e.g., silicate weathering vs. carbonate dissolution) is unclear.

Solution:

- Apply ion ratio analysis: Calculate key ratios like (Ca(^{2+}) + Mg(^{2+}))/HCO(_3^-) and Na(^+)/Cl(^-) to identify dominant processes [9].

- Utilize statistical methods: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to identify factors controlling hydrogeochemistry [10].

- Create Gibbs diagrams: Plot TDS vs. Na(^+)/(Na(^+) + Ca(^{2+})) or Cl(^-)/(Cl(^-) + HCO(_3^-)) to distinguish rock dominance, evaporation, and precipitation domains [11] [9].

Experimental Protocol: Ion Ratio Analysis

- Collect groundwater samples using airtight high-density polyethylene bottles [12].

- Analyze major cations (Ca(^{2+}), Mg(^{2+}), Na(^+), K(^+)) and anions (Cl(^-), SO(4^{2-}), HCO(3^-), CO(_3^{2-})) using ion chromatography [12].

- Calculate milliequivalent ratios:

FAQ: Why are my groundwater cation exchange calculations not balancing?

Issue: Cation exchange calculations show imbalance, with unexpected Na(^+), Ca(^{2+}), or Mg(^{2+}) concentrations.

Solution:

- Verify hydrochemical facies: Determine if groundwater is Ca(^{2+})-Mg(^{2+})-HCO(3^-) type (typical of fresher waters) or Na(^+)-HCO(3^-) type (indicating cation exchange) [12].

- Check for reverse ion exchange: In coastal aquifers, seawater intrusion can cause Ca(^{2+}) release via reverse exchange: 2Na(^+) (water) + Ca(^{2+})-clay → 2Na(^+)-clay + Ca(^{2+}) (water) [13].

- Assess aquifer mineralogy: Clay-rich aquifers have higher cation exchange capacity (CEC) [14].

Experimental Protocol: Cation Exchange Assessment

- Perform hydrochemical facies classification using Piper trilinear diagrams [12] [13].

- Calculate Chloro-Alkaline Indices (CAI):

- CAI-1 = [Cl(^-) - (Na(^+) + K(^+))]/Cl(^-)

- CAI-2 = [Cl(^-) - (Na(^+) + K(^+))]/(SO(4^{2-}) + HCO(3^-) + NO(_3^-))

- Positive values indicate direct cation exchange; negative values indicate reverse exchange [13].

- Analyze sequential water samples along flow paths to observe cation evolution [12].

FAQ: How can I confirm silicate weathering as the primary process in my study area?

Issue: You suspect silicate weathering but need to confirm it versus other processes.

Solution:

- Conduct geochemical modeling: Use PHREEQC to simulate mineral saturation states [15].

- Analyze silica correlations: Check for correlations between HCO(3^-) and SiO(2) [15].

- Examine Na(^+) and K(^+) sources: Identify if feldspar weathering (e.g., albite: NaAlSi(3)O(8)) is contributing ions [9].

Experimental Protocol: Silicate Weathering Validation

- Measure SiO(_2) concentrations in groundwater samples [15].

- Plot (Na(^+) + K(^+)) vs. total cations and HCO(3^-) vs. SiO(2) [9].

- Calculate saturation indices for silicate minerals (e.g., chalcedony, quartz) using geochemical modeling [15].

- If HCO(3^-) and SiO(2) show strong correlation with (Na(^+) + K(^+)), silicate weathering is confirmed [9].

Hydrogeochemical Data Tables

Table 1: Characteristic Ion Ratios for Identifying Water-Rock Interactions

| Process | Diagnostic Ratio | Indicator Values | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate Weathering | (Na(^+) + K(^+))/Total Cations | >0.6 [9] | Coastal aquifer, China [9] |

| Carbonate Dissolution | (Ca(^{2+}) + Mg(^{2+}))/HCO(_3^-) | ~1.0 [13] | Valliyur, India [13] |

| Evaporite Dissolution | Na(^+)/Cl(^-) | ~1.0 [9] | Coastal aquifer, China [9] |

| Cation Exchange | CAI-1 & CAI-2 | Positive values [13] | Valliyur, India [13] |

| Reverse Cation Exchange | CAI-1 & CAI-2 | Negative values [13] | Valliyur, India [13] |

Table 2: Saturation Indices for Mineral Equilibrium Assessment

| Mineral | Saturation State | Hydrogeological Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcite | Saturated [12] | Confined volcanic aquifer [12] | Equilibrium reached |

| Dolomite | Saturated [12] | Confined volcanic aquifer [12] | Equilibrium reached |

| Chalcedony | Undersaturated [15] | Maar lake groundwater [15] | Active silicate weathering |

| Quartz | Variable [15] | Maar lake groundwater [15] | System evolution |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Hydrogeochemical Studies

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Bottles | Sample preservation without contamination [12] | Groundwater sampling [12] |

| HNO(_3) for Preservation | Acidification for cation stability [12] | Cation analysis (pH < 2) [12] |

| 0.20 μm Filter Membrane | Removal of dissolved substances and impurities [12] | Sample filtration before analysis [12] |

| PHREEQC Geochemical Modeling Code | Quantifying water-rock interaction processes [15] | Inverse geochemical modeling [15] |

| Ion Chromatography System | Major cation and anion analysis [12] | Hydrochemical characterization [12] |

Water-Rock Interaction Processes Workflow

Advanced Research Considerations

Integrating Isotopic Tracers

For sophisticated cation exchange correction, implement multi-isotopic approaches (δ(^{34})S-SO(_4), δ(^{11})B, (^{87})Sr/(^{86})Sr) to discriminate hydrogeological pathways and water-rock interaction intensity [16]. This is particularly valuable in complex aquifer systems where multiple processes coexist.

Seasonal Variation Accounting

Groundwater chemistry exhibits temporal variations that affect cation exchange processes [13]. Conduct sampling across both wet and dry seasons to characterize these fluctuations and their impact on your cation exchange corrections [12] [13].

Spatial Distribution Mapping

Use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with ordinary kriging to interpolate and visualize spatial patterns of groundwater quality parameters [10]. This helps identify zones with intense cation exchange activity and guides targeted sampling strategies.

How Cation Exchange Modifies Ionic Composition in Coastal and Hard Rock Aquifers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is cation exchange and why is it critical in groundwater studies? Cation exchange is a process where positively charged ions (cations) held on the surface of aquifer materials (like clay minerals or organic matter) are swapped with cations present in the groundwater. This occurs due to electrostatic forces on negatively charged particle surfaces [1]. It is critical in groundwater studies because it significantly alters the ionic and chemical composition of water as it flows through an aquifer, without necessarily changing the total dissolved solids. For accurate water quality assessment, especially in salinization studies, failing to account for these exchanges can lead to misinterpretation of water-rock interactions and pollution sources [17] [18].

2. How can I identify if cation exchange is occurring in my aquifer study? You can identify potential cation exchange by analyzing your hydrochemical data for specific indicators. Key signatures include:

- Chloride-Alkali Indices (CAI): Values greater than zero often suggest cation exchange is a dominant process [17].

- Ionic Deviations: Look for an enrichment of calcium (Ca²⁺) and strontium (Sr²⁺) coupled with a depletion of sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) in groundwater compared to a conservative mixing model (e.g., with seawater) [18]. A plot of (ΔCa²⁺ + ΔMg²⁺) against -(ΔNa⁺ + ΔK⁺) that approximates a 1:1 slope is a strong indicator, as the gain in bivalent cations is balanced by the loss of monovalent cations [18].

- Strontium Isotopes (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr): These isotopes are a powerful tracer. distinct ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr ratios can help distinguish between Sr sourced from mineral weathering and Sr released via cation exchange, helping to unravel complex hydrochemical processes [17].

3. My groundwater samples show unexpectedly high sodium levels. Could cation exchange be the cause? Yes. While cation exchange in coastal aquifers often releases Ca²⁺ and retains Na⁺ (leading to Na⁺ depletion in the water), the reverse process can also occur. In freshening aquifers (where freshwater displaces saline water), the exchange can release Na⁺ back into the water, increasing its concentration [19]. The specific direction of the exchange depends on the history of the aquifer and the concentration gradients between the water and the sediment surfaces.

4. What are common pitfalls when correcting for cation exchange effects? Common pitfalls include:

- Ignoring Multiple Processes: Attributing all ionic changes solely to cation exchange, when other processes like carbonate or silicate weathering, evaporite dissolution, or reverse weathering may also be contributing [17] [18].

- Incorrect End-Member Identification: Using an inappropriate conservative mixing model to calculate ionic deviations (Δions), which can lead to incorrect conclusions about the magnitude and direction of exchange [18].

- Overlooking Anthropogenic Inputs: Failing to account for anthropogenic contaminants like nitrate, which can affect redox conditions and indirectly influence other geochemical processes [17] [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Cation Exchange in Your Data

Problem 1: Unclear Hydrochemical Evolution Path

Symptoms: Your Piper or Stiff diagrams show a complex mix of water types that do not follow simple conservative mixing trends between freshwater and seawater end-members.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Construct a Conservative Mixing Model: Define your likely end-members (e.g., fresh groundwater, modern seawater, deep brine). Calculate the theoretical ionic concentrations for mixtures of these end-members without any chemical reactions.

- Calculate Ionic Deviations: For each sample, calculate the deviation (Δ) of major cations from the conservative mixing line using the formula:

Δion = [ion]sample - [ion]conservative_mixture. - Plot and Interpret Deviations: Create a cross-plot of (ΔCa²⁺ + ΔMg²⁺) against -(ΔNa⁺ + ΔK⁺). Data points clustering around a 1:1 slope line confirm cation exchange as a dominant process. Significant deviations from this line suggest the influence of additional processes like mineral weathering [18].

Problem 2: Distinguishing Weathering from Cation Exchange

Symptoms: You observe high concentrations of Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Sr²⁺ but cannot determine if they originate from mineral dissolution or are being released from sediment exchange sites.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Analyze Saturation Indices (SI): Calculate the Saturation Index for minerals like calcite, dolomite, and albite. A systematic increase in SI for these minerals with increasing salinity suggests that mineral weathering and dissolution are active contributors [17].

- Employ Multi-Isotope Tracers: Integrate strontium isotope ratios (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr). Typically, carbonate weathering yields lower ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr ratios (<0.709), while silicate weathering produces higher ratios. The isotopic signature can help partition the sources of ions [17].

- Correlate with Exchange Indicators: Compare your isotopic and SI data with cation exchange indicators like the Chloride-Alkali Indices. A strong correlation between CAI and ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr can help isolate the exchange-driven component of the ionic load [17].

Table 1: Key Diagnostic Tools for Identifying Cation Exchange

| Diagnostic Tool | What It Measures | Interpretation in Favor of Cation Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Chloride-Alkali Indices (CAI-I & CAI-II) | The balance between chloride and alkali ions [17]. | Values consistently greater than zero. |

| Ionic Deviation Plot ((ΔCa+ΔMg) vs -(ΔNa+ΔK)) | Net gain or loss of major cations relative to conservative mixing [18]. | Data points align closely with a 1:1 slope. |

| Strontium Isotopes (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) | The ratio of radiogenic to stable strontium isotopes [17]. | Distinct ratios that correlate with CAI and help trace exchange processes. |

Problem 3: Quantifying the Impact of Cation Exchange in Saline Intrusion

Symptoms: You are studying a coastal aquifer with saline intrusion but need to quantify how much of the ionic composition is modified by cation exchange versus simple mixing.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Determine Seawater Fraction: Use a conservative tracer like chloride (Cl⁻) to calculate the fraction of seawater (X_sw) in each sample.

- Predict Conservative Cation Concentrations: For each major cation (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺), calculate its expected concentration under conservative mixing:

[ion]conservative = (1 - X_sw)[ion]fresh + X_sw[ion]seawater. - Quantify Cation Exchange Flux: The difference between the measured and conservative concentration for each cation represents the net effect of cation exchange. A negative value indicates removal from water (adsorption), while a positive value indicates release into water (desorption). This can be expressed in meq/L for direct comparison [18].

Table 2: Example Calculation of Cation Exchange in a Coastal Aquifer (theoretical data)

| Parameter | Fresh Water End-member | Seawater End-member | Sample (40% Seawater) | Conservative Mix (40% SW) | Measured Concentration | Net Exchange (meq/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloride (Cl⁻) mg/L | 10 | 19,000 | 7,606 | 7,606 | 7,606 | 0 (Conservative) |

| Sodium (Na⁺) meq/L | 0.2 | 430 | 172.1 | 172.1 | 150.0 | -22.1 (Removal) |

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) meq/L | 1.5 | 18 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 25.0 | +16.9 (Release) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Hydrochemical Data Collection for Cation Exchange Evaluation

Objective: To collect groundwater samples suitable for analyzing major ions and identifying cation exchange processes.

Materials:

- Dedicated groundwater pumps and flow-through cells.

- Pre-cleaned HDPE sample bottles.

- On-site instruments for pH, EC, TDS, temperature, alkalinity.

- Filtration equipment (0.45 µm membrane filters).

- Sample preservation reagents (high-purity HNO₃ for cations).

Procedure:

- Well Purging: Purge at least three well volumes to ensure a sample representative of aquifer conditions. Stabilize parameters (pH, EC, TDS).

- Sample Collection: Filter water samples through 0.45 µm filters.

- Cations: Collect in acid-washed bottles and acidify to pH <2 with ultrapure HNO₃.

- Anions: Collect in clean bottles without acidification.

- On-site Measurement: Measure pH, EC, TDS, and alkalinity immediately using calibrated probes.

- Analysis: Analyze samples in the laboratory for major ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻/CO₃²⁻) using standard methods like ICP-MS/OES for cations and IC for anions [17] [19].

Protocol 2: Utilizing Strontium Isotopes as a Tracer

Objective: To determine the ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr ratio in groundwater to trace sources of Sr and elucidate cation exchange.

Materials:

- High-purity chelating resin.

- Clean lab facilities for low-blank sample processing.

- Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometer (TIMS) or Multi-Collector ICP-MS (MC-ICP-MS).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pre-concentrate Sr from a large volume of filtered, acidified water using ion-specific chelating resin.

- Chemical Separation: Purify the separated Sr using chromatographic techniques to remove isobaric interferences (e.g., Rb, Ca).

- Isotopic Analysis: Load the purified Sr onto a filament and analyze using TIMS or introduce it into an MC-ICP-MS.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the measured ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr ratios with potential end-members in your system (e.g., seawater, carbonate rocks, silicate rocks). Correlate the ratios with other hydrochemical parameters (e.g., CAI, Sr²⁺ concentration) to link isotopic signatures to specific processes like cation exchange [17].

Process Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cation Exchange Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Strong Acid Cation (SAC) Exchange Resins | Used in laboratory experiments to model cation selectivity and removal efficiency; also for pre-concentrating trace metals [20]. | Sulfonic acid functional groups on a styrene frame. Regenerate with HCl or H₂SO₄ [20]. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | For acidifying groundwater samples (to pH <2) to preserve cationic composition and prevent precipitation/adsorption onto bottle walls. | Use trace metal grade or better to avoid sample contamination. |

| 0.45 µm Membrane Filters | To remove suspended particles and colloids from water samples, ensuring that the analyzed ions are truly dissolved. | A standard step before major ion and isotope analysis. |

| Strontium-Specific Chelating Resin | For selectively separating and pre-concentrating strontium (Sr) from complex water matrices prior to isotopic analysis (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) [17]. | Critical for obtaining low-blank, high-purity Sr samples for TIMS or MC-ICP-MS. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | To calibrate analytical instruments and verify the accuracy and precision of major ion and isotopic measurements. | Essential for quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC). |

Distinguishing Natural Geogenic Signals from Anthropogenic Contamination

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why is it so challenging to differentiate natural and anthropogenic contaminants in groundwater systems?

The challenge arises from the overlapping signatures of pollutants from various sources and the complex hydrogeochemical processes that control water composition. Key difficulties include:

- Overlapping Sources: Heavy metals and trace elements can originate from both natural weathering of bedrock (geogenic) and human activities like industrial discharge or agricultural runoff (anthropogenic) [21].

- Complex Hydrogeochemistry: Processes like rock-water interactions, ion exchange, and redox reactions can alter contaminant concentrations and speciation, blurring their original source [22]. For instance, the natural geologic context (e.g., hard rock terrain) exerts a primary control on baseline water chemistry, which can be modified by anthropogenic interventions [22].

Q2: What are the primary sources and factors that influence groundwater contamination?

Groundwater quality is impacted by a combination of natural and human-induced factors [21]:

- Anthropogenic Sources: These include improper waste disposal, environmentally-unfriendly agricultural activities (agrochemicals like DDT and DDE), poor sanitation practices, leaking landfills, and industrial discharges [21] [23].

- Geogenic/Natural Factors: Geologic processes, lithology (rock type), pedological factors (soil type), and climatic conditions naturally control the dissolution of minerals and elements into groundwater [21] [22].

- Composite Properties: Understanding the redox status and cation exchange conditions of an aquifer is crucial, as they control the mobility and degradation of contaminants [7].

Q3: My research involves assessing cation exchange in a coastal aquifer. What is a robust methodological approach for mapping this process?

An innovative two-step GIS method has proven effective for regional mapping of cation exchange conditions [7]:

- Interpolation: First, map key groundwater components of interest (e.g., Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, Na⁺, Mg²⁺) using an appropriate geostatistical interpolation method, such as Empirical Bayesian Kriging, identified through a prior geostatistical analysis.

- Spatial Analysis: Second, combine these interpolated variables and use conditional functions within a GIS platform's (e.g., ArcMap) Math toolbox to determine and map the cation exchange classes.

This method has demonstrated a high prediction accuracy, with a 75%–95% agreement between predicted and observed groundwater conditions in field studies [7].

Q4: What advanced analytical tools can help trace the source of organic anthropogenic contamination in a water system?

Molecular markers are powerful tools for tracing anthropogenic contamination due to their chemical stability and diagnostic capabilities [24]. Key markers include:

- Coprostanol: A definitive indicator for sewage inputs.

- Linear Alkylbenzenes (LABs): Unambiguous tracers of untreated domestic and industrial wastewater.

- Unresolved Complex Mixtures (UCMs): Diagnostic profiles indicating petroleum hydrocarbon contamination. The spatial distribution of these markers across a watershed (e.g., from riverine sources to reservoirs) can reveal contamination hotspots and transport pathways, with land-use patterns being a key driver [24].

Q5: During sample preparation for organic pollutant analysis, my solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges often get blocked. What are the potential solutions?

Channeling and cartridge blockage, especially with complex environmental samples, are known drawbacks of traditional SPE [25]. Consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Use SPE Discs: Replace cartridges with disc formats. Discs have a large cross-sectional area, which reduces processing time and minimizes the risk of blockage and channeling [25].

- Explore New Sorbents: Investigate the use of novel sorbent materials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs), which can be fabricated into membranes or discs with high mechanical stability and efficiency [25].

- Alternative Techniques: For specific applications, other extraction methods like dispersive SPE (dSPE) or magnetic SPE (MSPE) can be more robust, as they involve dispersing the sorbent in the sample and separating it via centrifugation or an external magnetic field, thus avoiding cartridge issues [25].

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

This protocol details the methodology for creating regional maps of non-numerical hydrogeochemical indices.

- Objective: To spatially visualize groundwater redox status and cation exchange conditions.

- Materials and Software: Groundwater quality data (for Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, Fe, NO₃⁻, Na⁺, Mg²⁺), GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS), geostatistical analysis tools.

- Methodology Details:

- Data Collection and Preparation: Compile a dataset of groundwater samples from multiple monitoring locations (e.g., 3350 samples). Ensure data includes concentrations of the relevant ions.

- Geostatistical Analysis: Perform a geostatistical analysis on each ion dataset to identify the most appropriate interpolation method (e.g., Empirical Bayesian Kriging, Ordinary Kriging).

- Interpolation: Generate continuous raster surfaces for each ion concentration using the identified optimal interpolation method.

- Define Classification Rules: Establish logical, conditional rules based on hydrogeochemical principles to classify each map pixel into categories (e.g., "oxic," "suboxic," "anoxic" for redox status).

- Map Algebra: Use the GIS's Math toolbox (e.g., Raster Calculator in ArcMap) to apply the conditional functions to the interpolated rasters, combining them to produce the final classified maps of redox status and cation exchange.

The workflow for this methodology is outlined in the diagram below.

This protocol describes using molecular markers to track human-derived pollution in a river-reservoir system.

- Objective: To identify sources, distribution, and transport pathways of organic pollutants.

- Materials: Surface sediment samples, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) system, solvents for extraction.

- Methodology Details:

- Study Design and Sampling: Define the hydrological continuum (riverine sources, watercourses, reservoir). Collect surface sediment samples from each zone.

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Extraction: Extract organic compounds from sediments using appropriate solvents (e.g., via liquid-liquid extraction or accelerated solvent extraction).

- Fractionation and Analysis: Separate the total extract into compound classes (e.g., hydrocarbons, sterols) and analyze via GC-MS.

- Data Interpretation:

- Identify Markers: Quantify specific molecular markers: Coprostanol (sewage), Linear Alkylbenzenes - LABs (wastewater), Unresolved Complex Mixtures - UCMs (petroleum), n-alkanes (biogenic vs. petrogenic sources).

- Spatial Analysis: Compare the concentrations and ratios of these markers across the different hydrological units to identify contamination hotspots and attenuation zones.

The following table summarizes key molecular markers and their interpretations [24].

Table 1: Key Molecular Markers for Tracing Anthropogenic Contamination

| Marker | Primary Indication | Remarks / Diagnostic Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Coprostanol | Sewage Input (Fecal Contamination) | A sterol that is a definitive indicator of mammalian fecal matter. |

| Linear Alkylbenzenes (LABs) | Untreated Domestic & Industrial Wastewater | Persist as precursors to detergents; specific homolog distributions can indicate degradation. |

| Unresolved Complex Mixture (UCM) | Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contamination | Appears as a "hump" of unresolved compounds in GC-MS chromatograms. |

| n-Alkanes | Biogenic (plant waxes) vs. Petrogenic Sources | Carbon chain length distributions and indices (e.g., CPI) help distinguish sources. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Contaminant Source Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from water samples prior to chromatographic analysis [25]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Advanced sorbent material for SPE and microextraction devices; offers high surface area and efficiency for extracting a wide range of contaminants [25]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green, alternative solvents for extraction techniques like dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (DLLME), offering low volatility and tunable properties [25]. |

| Molecular Markers (e.g., Coprostanol, LABs) | Diagnostic chemical tracers used to identify and apportion specific anthropogenic pollution sources (e.g., sewage, petroleum) in environmental samples [24]. |

| GIS Software & Geostatistical Tools | Platform for spatial analysis, interpolation of water quality data, and mapping of complex, non-numerical hydrogeochemical classes like redox status [7] [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary geochemical indicators of reverse cation exchange in groundwater? Reverse cation exchange occurs when Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ from water are adsorbed onto clay minerals, releasing Na⁺ into the groundwater. Key indicators include a high Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) and a Chloro-Alkaline Index (CAI) with negative values [26]. Furthermore, a (Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺) vs. (HCO₃⁻ + SO₄²⁻) scatter plot can reveal this process; if data points fall below the 1:1 equivalence line, it suggests that Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ are being removed from the solution via exchange [26].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between silicate weathering and carbonate dissolution as primary mineral dissolution processes? The ratios of major ions are effective diagnostic tools. The molar ratio of (Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺)/HCO₃⁻ can indicate the process dominance: a ratio close to 1 suggests carbonate dissolution, while a ratio significantly greater than 1 points to silicate weathering as a major contributor of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ [26]. Additionally, analyzing the (Na⁺ + K⁺) vs. Cl⁻ relationship is useful; if Na⁺ + K⁺ exceeds Cl⁻, the excess ions are likely derived from silicate weathering processes [27].

FAQ 3: What quantitative methods confirm the dominance of water-rock interactions over anthropogenic influences? Gibbs diagrams are a primary method for this determination. Plotting TDS against the ratios of Na⁺/(Na⁺ + Ca²⁺) and Cl⁻/(Cl⁻ + HCO₃⁻) shows the relative roles of precipitation dominance, rock weathering, and evaporation [27]. Data points that fall within the "rock dominance" zone confirm that water-rock interactions are the main control on the groundwater chemical composition [26] [27].

FAQ 4: My groundwater samples show high TDS and hardness. How do I troubleshoot the source? Begin by calculating the saturation indices (SI) for key minerals like calcite (CaCO₃) and dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂) using geochemical modeling software such as PHREEQC [26] [27]. As shown in the table below, positive SI values indicate mineral precipitation is likely controlling solute concentrations, while negative values point to ongoing dissolution. Subsequent bivariate plots (e.g., Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺ vs. HCO₃⁻+SO₄²⁻) and statistical analysis (ANOVA) can then isolate the influence of carbonate dissolution from other processes like cation exchange or evaporite dissolution [26].

Diagnostic Geochemical Ratios and Indices

The following table summarizes key quantitative indicators for identifying hydrogeochemical processes [26] [27].

Table 1: Key Geochemical Ratios and Indices for Process Identification

| Process | Diagnostic Ratio/Index | Interpretation | Typical Value/Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Cation Exchange | Chloro-Alkaline Index (CAI) | Negative values indicate reverse exchange (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺ adsorbed; Na⁺ released) [26]. | CAI < 0 |

| Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) | High values indicate a high relative concentration of Na⁺, often a result of cation exchange [26]. | Varies by aquifer | |

| Mineral Dissolution | (Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺)/HCO₃⁻ (molar ratio) | ≈1: Carbonate dissolution [26]. >1: Silicate weathering or other sources [26]. | Ratio ≈ 1 or >1 |

| (Na⁺ + K⁺)/Cl⁻ (molar ratio) | ≈1: Halite dissolution [26]. >1: Excess Na⁺, K⁺ from silicate weathering [26]. | Ratio ≈ 1 or >1 | |

| General Water-Rock Interaction | Gibbs Ratio I (for anions) | Gibbs Ratio I = Cl⁻/(Cl⁻ + HCO₃⁻). Low ratio values indicate rock weathering dominance [27]. | Rock dominance: Ratio < 0.25 [27] |

| Gibbs Ratio II (for cations) | Gibbs Ratio II = (Na⁺ + K⁺)/(Na⁺ + K⁺ + Ca²⁺). Low ratio values indicate rock weathering dominance [27]. | Rock dominance: Ratio < 0.25 [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Hydrogeochemical Characterization

Sample Collection and Analysis Protocol

- Field Sampling: Collect groundwater samples from monitoring wells. Measure and record in-situ parameters (pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Temperature, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Oxidation-Reduction Potential (Eh)) using a calibrated portable meter [27].

- Sample Preservation: Filter water samples through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. For cation analysis, acidify samples with high-purity nitric acid to a pH < 2 to prevent precipitation and adsorption [27].

- Laboratory Analysis: Analyze major cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Ion Chromatography (IC). Analyze anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, HCO₃⁻) via titration (for HCO₃⁻) and Ion Chromatography [27].

- Quality Control: Perform an ionic balance error check. The error should be within ±5% for the data to be considered acceptable [27].

Data Interpretation and Modeling Protocol

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct descriptive statistics and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the hydrochemical data to identify significant seasonal variations and spatial trends [26].

- Graphical Plotting: Create Piper trilinear diagrams to determine the hydrochemical facies of the water and Gibbs diagrams to identify the major mechanisms controlling water chemistry (e.g., rock weathering, precipitation, evaporation) [26] [27].

- Geochemical Modeling: Use software like PHREEQC to:

- Calculate the Saturation Index (SI) for minerals (e.g., calcite, dolomite, gypsum, halite). SI = log(IAP/Ksp), where IAP is the ion activity product and Ksp is the solubility product. An SI near zero suggests equilibrium, positive SI suggests oversaturation (potential for precipitation), and negative SI suggests undersaturation (potential for dissolution) [26] [27].

- Perform inverse modeling to quantify the mass transfer of minerals (amounts dissolved or precipitated) along a hypothesized groundwater flow path [27].

The workflow for data interpretation and modeling is outlined below.

Saturation Indices of Common Minerals

Saturation Index (SI) calculations are critical for determining the thermodynamic tendency of a mineral to dissolve or precipitate. The table below provides a guide for interpreting SI values.

Table 2: Interpretation of Mineral Saturation Indices (SI)

| Mineral | Chemical Formula | SI < 0 (Undersaturated) | SI ≈ 0 (At Equilibrium) | SI > 0 (Oversaturated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcite | CaCO₃ | Dissolution is thermodynamically favorable [26]. | System is in equilibrium with the mineral [26]. | Precipitation is thermodynamically favorable [26]. |

| Dolomite | CaMg(CO₃)₂ | Dissolution is thermodynamically favorable [26]. | System is in equilibrium with the mineral [26]. | Precipitation is thermodynamically favorable [26]. |

| Gypsum | CaSO₄·2H₂O | Dissolution is thermodynamically favorable [26]. | System is in equilibrium with the mineral. | Precipitation is thermodynamically favorable. |

| Halite | NaCl | Dissolution is thermodynamically favorable [26]. | System is in equilibrium with the mineral. | Precipitation is thermodynamically favorable. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table lists key materials and software tools essential for conducting research on cation exchange and mineral dissolution.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| 0.45 μm Membrane Filter | Used for field filtration of groundwater samples to remove suspended particles and microorganisms, ensuring the analysis represents dissolved solutes [27]. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Used for sample acidification to preserve cation concentrations (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺) by preventing adsorption to container walls and precipitation [27]. |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) System | Analytical instrument for the simultaneous separation and quantification of major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) and cations in water samples [27]. |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) | Analytical instrument for determining the concentration of specific metal cations (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) in groundwater samples [27]. |

| PHREEQC Software | A widely used geochemical modeling program for calculating mineral saturation indices, simulating reaction paths, and performing inverse mass-balance modeling [27]. |

| ArcGIS Software with Geostatistical Analyst | A GIS platform used for spatial interpolation (e.g., Empirical Bayesian Kriging) of hydrochemical parameters and creating predictive maps of redox status or cation exchange conditions [7]. |

| GWSDAT (GroundWater Spatiotemporal Data Analysis Tool) | An open-source software tool designed for the visualization and spatiotemporal analysis of groundwater monitoring data, including the generation of concentration contour plots and trend analysis [28]. |

Advanced Techniques for Characterizing and Mapping Cation Exchange Processes

Innovative GIS and Empirical Bayesian Kriging for Regional Redox and CEC Mapping

This technical support center provides resources for researchers correcting for cation exchange effects in groundwater quality studies. The guides below address implementing an innovative two-stage GIS method to map complex, non-numerical groundwater conditions like redox status and cation exchange conditions (CEC) using Empirical Bayesian Kriging (EBK). This methodology is crucial for accurately characterizing environments that control contaminant degradation and nutrient mobility [7] [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why should I use Empirical Bayesian Kriging over other geostatistical methods for groundwater interpolation? EBK automates the most difficult aspects of building a valid kriging model and accounts for the error introduced by estimating the underlying semivariogram, leading to more accurate prediction standard errors. It is particularly effective for handling the moderate nonstationarity common in groundwater quality data and has been shown to outperform methods like Ordinary, Simple, and Universal Kriging for key parameters like Cl, SO₄, Fe, PO₄, and NH₄ in coastal lowland environments [30] [31].

2. My study involves mapping linguistic classes like "reducing" or "oxidizing." How can GIS handle these non-numerical indices? A two-stage approach within a GIS environment is effective. First, use a robust interpolation method like EBK to create continuous surfaces of numerical groundwater components (e.g., Cl, SO₄, Fe, NO₃). Second, use the GIS's conditional math functions (e.g., the Raster Calculator or Map Algebra) to apply logical rules that combine these surfaces to determine the final redox or CEC classes [7] [29].

3. I am getting poor interpolation results. What are the common pitfalls with EBK? Common issues include:

- Incorrect Transformation for Data with Outliers: The

Log Empiricaltransformation is sensitive to outliers and can produce wildly inaccurate predictions. Use it with caution [30]. - Extremely Long Processing Times: This occurs with large datasets, large subset sizes, high overlap factors, or using complex semivariogram models like

K-Bessel. Optimize these parameters for your data [30] [32]. - Ignoring Data Stationarity: While EBK handles moderately nonstationary data better than other kriging methods, highly nonstationary data may still require detrending, which can be achieved by selecting a

Detrendedsemivariogram model [30].

4. How do I validate the accuracy of my final redox and CEC maps? Compare your predicted maps against observed data from groundwater sampling locations. The referenced study achieved a 75%–95% agreement between predicted and observed conditions for most redox and cation exchange classes, proving the method's effectiveness [7] [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: EBK Processing is Extremely Slow

Problem: The EBK model in ArcGIS is taking hours or days to complete.

Solutions:

- Reduce Subset Size: Decrease the

Maximum number of points in each local modelparameter. The default is 100; try a smaller value [30] [32]. - Lower the Overlap Factor: The

Local model area overlap factorcontrols how many subsets each point falls into. High values (e.g., near 5) make the surface smoother but drastically increase processing time. Typical values are between 0.01 and 5 [32]. - Choose a Faster Semivariogram Model:

LinearandThin Plate Splineare the fastest.Poweris a good balance of speed and flexibility. AvoidK-BesselandK-Bessel Detrendedfor large initial tests [30]. - Use a Standard Circular Search Neighborhood: The

Smooth Circularsearch neighborhood substantially increases execution time [32].

Issue 2: EBK Predictions are Inaccurate or Include Impossible Values

Problem: The output raster contains prediction values that are orders of magnitude too large/small or are physically impossible (e.g., negative concentrations).

Solutions:

- Check Data for Outliers: If you used the

Log Empiricaltransformation, extreme outliers can distort results. Carefully screen your input data for errors [30]. - Ensure Positive Data for Log Transformation: The

Log Empiricaltransformation requires all input data values to be positive. Filter or clean your data to remove zero or negative values if using this transformation [30]. - Re-evaluate Semivariogram Model Choice: Use the guidance in the table below to select a model more appropriate for your data's spatial structure [30].

Issue 3: Difficulty Combining Rasters to Create Categorical Redox/CEC Maps

Problem: You have successfully created rasters for individual chemical parameters but are unsure how to combine them into a single map of categorical classes.

Solutions:

- Use Conditional Statements in Raster Calculator: The final step uses the GIS's math toolbox. For example, to define a "Reducing" class, your conditional statement might be structured as:

Con(("Fe" > 0.5) & ("SO4" < 0.1), 1, 0)where1represents the "Reducing" class. You would build a series of such statements for all redox or CEC classes [7] [29]. - Validate Each Intermediate Raster: Before combining them, ensure each chemically interpolated raster (e.g., for Fe, SO₄) is accurate and makes sense hydrologically.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Two-Stage Mapping of Redox and CEC

Application: This protocol is for mapping regional groundwater redox status and cation exchange conditions in a GIS environment, specifically within the context of correcting for cation exchange effects [7] [29].

Workflow Overview:

Stage 1: Interpolate Groundwater Components

- Data Preparation: Compile groundwater sample data with locations and concentrations of key parameters: Chloride (Cl), Sulfate (SO₄), Iron (Fe), Nitrate (NO₃), and calculated ratios like SO₄/Cl and base exchanges (Na, Mg) [7] [29].

- Geostatistical Analysis: Perform exploratory analysis to understand the spatial structure of each parameter.

- Interpolation with EBK: For each parameter, use the EBK interpolation method. Refer to the "EBK Parameter Guide" table below for configuration.

Stage 2: Create Categorical Maps

- Define Classification Rules: Establish logical rules based on groundwater chemistry to define classes. For example:

- Oxic: NO₃ > 0 and Fe = 0

- Reducing: NO₃ = 0 and Fe > 0

- Apply Conditional Functions: In ArcMap's

Math toolbox(e.g., Raster Calculator), useCon(conditional) functions to apply these rules by combining the interpolated rasters from Stage 1 [7]. - Validation: Compare the final classified map against held-back sample points to calculate the agreement percentage.

EBK Parameter Guide for ArcGIS

Table: Key parameters for configuring Empirical Bayesian Kriging in ArcGIS [30] [32].

| Parameter | Description | Recommendation / Options |

|---|---|---|

| Data Transformation Type | Transforms data to meet statistical assumptions. | None: Default, safe choice.Empirical: For non-normal data.Log Empirical: For positive, skewed data; sensitive to outliers. |

| Semivariogram Model Type | Defines how spatial similarity changes with distance. | If Transformation = None: Power (fast/flexible), Linear (very fast), Thin Plate Spline (strong trends).If Transformation = Empirical/Log: Exponential, K-Bessel (most flexible, but slowest). |

| Max Points in Local Model | Maximum size of data subsets. | Default is 100. Reduce for faster processing. |

| Overlap Factor | Degree of overlap between local models. | Values 0.01-5. Higher values create smoother surfaces but increase processing time. |

| Search Neighborhood | Defines which points are used for prediction. | Standard Circular: Default, faster.Smooth Circular: Smoother results, much slower. |

Comparative Performance of Kriging Methods

Table: Example performance comparison for groundwater quality interpolation, showing root mean square error (RMSE) values from a study in the western Netherlands [31]. Lower RMSE indicates better performance.

| Interpolation Method | Chloride (Cl) | Sulfate (SO₄) | Iron (Fe) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Bayesian Kriging (EBK) | 1.45 | 1.21 | 0.89 |

| Ordinary Kriging (OK) | 1.98 | 1.45 | 1.12 |

| Simple Kriging (SK) | 2.45 | 1.39 | 1.54 |

| Universal Kriging (UK) | 1.89 | 1.48 | 1.08 |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential research reagents and materials for conducting groundwater redox and CEC studies using GIS and geostatistics.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| ArcGIS Software | Primary GIS platform containing the Geostatistical Analyst extension, which is required for running Empirical Bayesian Kriging and performing raster math operations [7] [30]. |

| Groundwater Monitoring Data | Field measurements from monitoring wells, including coordinates (X, Y, Z) and chemical concentrations (e.g., Cl, SO₄, Fe, NO₃, Na, Mg). The foundational dataset for all interpolation [7] [29]. |

| Empirical Bayesian Kriging (EBK) | The core geostatistical interpolation algorithm used to predict values at unsampled locations and create continuous surfaces of groundwater chemical parameters [7] [30] [31]. |

| Conditional (Con) Function | A key function within the GIS's math toolbox used to apply logical rules to combine multiple raster layers into a final categorical map (e.g., classifying redox status) [7]. |

| Groundwater Quality Standards | Reference tables (e.g., for drinking water or ecological health) used to help define the logical thresholds and rules for classifying redox and cation exchange conditions [7] [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

Q1: What is the minimum extraction time required for accurate CEC determination, and does it work for all soil types? A modified single extraction method using vigorous stirring requires only 3–5 minutes to complete the cation exchange process, a significant reduction from the standard 60-minute oscillation [34]. This shortened time is sufficient for acidic, neutral, and alkaline soils, allowing for rapid batch processing [34]. However, for saline soils, a short extraction time may still not prevent the dissolution of gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) and sodium salts, which can lead to an overestimation of exchangeable Ca and Na [34].

Q2: How should I prepare the extractant for analyzing calcareous soils, and can the time-consuming process be avoided? For soils containing calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), the ISO 23470:2018 standard recommends using a calcite-saturated [Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃ solution to prevent the dissolution of native calcite and an overestimation of exchangeable Ca [34]. The preparation of this saturated solution is time-consuming, requiring ultrasonic suspension, magnetic stirring, and setting overnight [34]. Solution: Research indicates that for the modified 3–5 minute stirring method, the calcite-saturation procedure can be omitted entirely without affecting the accuracy of CEC or exchangeable base cation determinations, even with CaCO₃ content as high as 80% [34].

Q3: My CEC values do not match the certified range for my reference soil. What could be the cause? Discrepancies between measured and certified CEC values are often linked to the pH of the extractant and specific soil properties [34]. The certified values for reference materials are typically established using specific methods (e.g., ammonium acetate at pH 7), and a difference in extractant pH can cause variances [34].

- For Acidic Soil: Measured CEC may be below the certified range [34].

- For Alkaline, Saline, and Sodic Soils: Measured CEC is frequently above the certified range [34].

Q4: How can I accurately determine exchangeable cations in saline and sodic soils? Saline and sodic soils present challenges due to the dissolution of soluble salts during extraction [34].

- In Saline Soils: Accurate determination of exchangeable Ca and Na is difficult due to the dissolution of gypsum and sodium salts. Exchangeable Mg and K may be reported below the certified range [34].

- In Sodic Soils: A practical workaround is to calculate exchangeable Na indirectly: exch. Na = CEC − (exch. Ca + exch. Mg + exch. K) [34].

Comparison of Standard vs. Modified Method

The table below summarizes the key differences between the standard ISO method and the proposed modifications.

| Feature | ISO 23470:2018 Standard Method | Modified Stirring Method |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Time | 60 ± 5 minutes [34] | 3–5 minutes [34] |

| Mixing Technique | Oscillation (shaking) [34] | Vigorous stirring [34] |

| Extractant for Calcareous Soils | Requires calcite-saturated [Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃ (prep time: ~overnight) [34] | Unsaturated solution is sufficient, preparation step omitted [34] |

| Suitability for Saline/Sodic Soils | Challenging due to salt dissolution [34] | Remains challenging; indirect calculation of exch. Na recommended for sodic soils [34] |

| Overall Efficiency | Lower, suitable for small batches [34] | High, ideal for large-scale soil assessments [34] |

Experimental Protocol: Modified Single-Extraction Stirring Method

Principle: The method uses hexamminecobalt trichloride ([Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃) as an index cation to displace exchangeable base cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺) from soil colloids. The CEC is calculated from the depletion of Co(NH₃)₆³⁺ in the solution, while the concentrations of base cations in the extract are used to determine their exchangeable amounts [34].

Materials:

- Extractant: 1.6 mM [Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃ solution. For the modified method, this does not need to be saturated with calcite [34].

- Equipment: Centrifuge, filtration setup, spectrocolorimeter (for measurement at 425 nm) or Atomic Absorption Spectrometer/Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometer for cation analysis [34] [35].

- Soil: Air-dried and sieved (<2 mm) soil sample.

Procedure:

- Weigh a mass of soil containing approximately 0.5-1.0 meq of total exchangeable cations (e.g., ~1g of many topsoils) into a suitable centrifuge tube [35].

- Add a specific volume (e.g., 25-50 mL) of the 1.6 mM [Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃ extractant [35].

- Stir the mixture vigorously for 3–5 minutes to achieve complete cation exchange [34].

- Centrifuge and filter the mixture to obtain a clear supernatant.

- Analyze the filtrate:

- Calculation:

- CEC (meq/100g) = [((Cinitial - Cfinal) * V * 100) / (m * 1000)] * 3 Where: Cinitial and Cfinal are the initial and final concentrations of [Co(NH₃)₆]³⁺ (mmol/L), V is the volume of extractant (mL), m is the mass of soil (g), and 3 is the valence of the cation [34].

- Exchangeable Cations: Calculate the amount of each base cation in meq/100g from its measured concentration in the extract.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| [Co(NH₃)₆]Cl₃ (Cobalt Hexamine Trichloride) | Index cation; the colored complex (Co(NH₃)₆³⁺) displaces native exchangeable cations from soil colloids for CEC measurement [34] [35]. |

| Calcite (CaCO₃) | Used to prepare a saturated extractant for the standard method to prevent dissolution from calcareous soils. The modification shows this step can be omitted [34]. |

| Centrifuge | Essential for rapid separation of the soil residue from the extract after the reaction [34]. |

| Spectrocolorimeter | Enables direct, simple, and repeatable measurement of the Co(NH₃)₆³⁺ concentration at 425 nm for CEC calculation [35]. |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) | Standard instrument for quantifying the concentrations of base cations (Ca, Mg, K, Na) in the extract [35]. |

Workflow for Soil-Specific CEC Determination

This diagram illustrates the decision-making process for applying the modified method based on soil properties.

Experimental Workflow for Modified CEC Method

This diagram outlines the step-by-step laboratory procedure for the modified method.

Frequently Asked Question: How can geophysical properties like magnetic susceptibility and electrical conductivity possibly relate to soil chemistry and groundwater quality?

The connection lies in the fundamental physical properties of the soil matrix. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) is a key chemical property indicating a soil's ability to retain and exchange positively charged ions, crucial for nutrient availability and contaminant mobility [36]. In the context of your thesis on groundwater quality, understanding CEC helps correct for how subsurface layers attenuate or retarget cationic pollutants.

Recent research demonstrates that geophysical properties can act as proxies for CEC. Soil magnetic susceptibility (κ) reflects the concentration of ferrimagnetic minerals (e.g., maghemite), which are often associated with the clay fraction that also contributes to permanent CEC [36]. Simultaneously, electrical conductivity (σ) is influenced by the concentration of free ions in the soil pore water and the surface conductivity of the soil particles, which is directly related to the CEC [36]. By integrating measurements of both κ and σ, you can develop a pedotransfer function (PTF) to rapidly estimate CEC in the field, providing a cost-effective method to characterize sites for groundwater quality studies [36].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Frequently Asked Question: What is a validated step-by-step protocol for collecting field data to build a CEC prediction model?

The following integrated field and laboratory protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that successfully developed a novel PTF using σ and κ* [36].

Field Measurement Protocol

- Site Selection & Preparation: Excavate a soil test pit to expose a fresh vertical profile wall.

- In-situ Magnetic Susceptibility (κ*):

- Instrument: Kappa meter (e.g., SM30 by ZH Instruments) operating at a low frequency (e.g., 8 kHz).

- Procedure: Place the sensor firmly against the soil profile wall at the desired depth interval. Record the measurement.

- Calibration: Take a subsequent measurement in the open air, away from the profile, to obtain a reference zero κ value. Use this to calibrate the soil measurement [36].

- Replication: Take 5-11 measurements per horizon or site to account for heterogeneity.

- In-situ Electrical Conductivity (σ):

- Instrument: Soil sensor (e.g., HydraProbe by Stevens Water Monitoring Systems).

- Procedure: Place the sensor against the same profile wall where κ* was measured.

- Data Correction: Apply established corrections, such as the one proposed by Logsdon et al. (2010), to improve the quality of the σ readings [36].

- Soil Sampling:

- Undisturbed Samples: Collect using standard steel rings (e.g., 100 cm³ volume) pushed horizontally into the profile wall. These are for determining bulk density and volumetric water content.

- Disturbed Samples: Collect approximately 250 g of soil from around the undisturbed sample location. These are for laboratory analysis of texture, chemical properties, and CEC.

Laboratory Analysis Protocol

- Soil Sample Preparation: Air-dry the disturbed samples, homogenize gently with an agate mortar, and sieve through a 2 mm mesh.

- CEC Measurement: Determine CEC using a standard laboratory method, such as the sodium saturation method (e.g., method by Busenberg and Clemency, 1973) [36]. For consistency in groundwater studies, it is common to measure CEC at a neutral pH (CEC₇).

- Supplementary Property Analysis: Characterize the samples by measuring:

- Texture: Using the pipette method to determine clay, silt, and sand content [36].

- Humus/Organic Carbon Content.

- Iron Content.

- Soil pH.

Data Interpretation & Modeling

Frequently Asked Question: I have collected my κ and σ data. How do I transform it into a CEC prediction?

The core of the process involves developing a statistical model, or Pedotransfer Function (PTF). The 2025 study found that polynomial regression models, especially multivariable ones, are effective for this task, particularly with smaller datasets [36].

Model Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the data processing and model development pipeline.

Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Research

Table 1: Performance of different model types for predicting CEC (adapted from [36]).

| Model Type | Input Variables | Soil Type | Performance (R²) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | κ* (in-situ magnetic susceptibility) | Sandy | Significant Improvement | Effective independent of clay content. |

| Multivariable | κ* & σ (in-situ electrical conductivity) | Sandy | 0.94 | Highest predictive performance achieved. |

| Laboratory-based | Laboratory κ | Various | Less Effective | Sample disturbance likely reduces accuracy. |

Table 2: Significant correlations from related geochemical-geophysical studies [37].

| Relationship | Correlation Type | Observed Effect | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEC vs. Leached Pb | Strong Negative Correlation | Soils with higher CEC retained Pb more effectively. | Contaminated shooting range site. |

| Electrical Resistivity (ER) vs. Pb | Significant Predictor | ER was a significant predictor in a multivariate regression model (adj. R² = 0.806). | Model for estimating soil Pb contamination. |

Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Question: My CEC prediction model is performing poorly. What could be wrong?

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Model Accuracy (R²) | 1. Incorrect Measurement Scale: In-situ κ and σ measurements are influenced by different soil volumes. 2. Soil-Type Dependency: The κ-CEC relationship is strongest in sandy soils and may be masked in clay-rich soils [36]. 3. Sample Disturbance: Using laboratory κ measurements instead of in-situ κ* [36]. | 1. Ensure measurements are taken from the same soil volume/horizon. Correlate core samples directly with the geophysical measurement spot. 2. Stratify your dataset by soil texture (sandy vs. clayey) and develop separate PTFs for each. 3. Prioritize in-situ κ* measurements to avoid the inaccuracies introduced by sample collection and handling. |

| High Variability in κ Readings | 1. Instrument Sensitivity: Ferromagnetic debris (nails, wire) in the soil. 2. Insufficient Replication: High small-scale soil heterogeneity. | 1. Visually inspect the soil profile and use a magnet to screen for large metal objects. Clear the area. 2. Increase the number of replicate measurements per horizon (e.g., 5-11 as in the protocol) to capture natural variability. |

| Electrical Conductivity Values are Noisy | 1. Poor Sensor-Soil Contact. 2. Uncorrected Data. 3. Highly variable soil water content. | 1. Ensure the sensor is placed firmly against a flat, clean soil surface. 2. Apply standard corrections to raw σ data (e.g., Logsdon et al., 2010) [36]. 3. Measure water content simultaneously from core samples to account for its dominant effect on σ. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Equipment

Table 3: Key materials and instruments for geophysical CEC prediction studies.

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Kappa Meter | Measures in-situ magnetic susceptibility (κ*), the key magnetic property. | SM30 (ZH Instruments); sensitivity of 10⁻⁷ SI units, operating at 8 kHz [36]. |

| Soil Sensor | Measures in-situ electrical conductivity (σ), a primary input variable. | HydraProbe (Stevens Water Monitoring Systems); measures σ, water content, and temperature [36]. |

| Soil Core Samplers | For collecting undisturbed soil samples to determine bulk density, water content, and for laboratory CEC analysis. | Standard steel rings of known volume (e.g., 100 cm³) [36]. |

| Sodium Saturation Reagents | For laboratory determination of CEC using the standard sodium saturation method. | Sodium acetate, magnesium sulfate, or other reagents per established methods (e.g., Busenberg and Clemency, 1973) [36]. |

| Agate Mortar and Pestle | For gently homogenizing air-dried soil samples without contaminating them with magnetic minerals. | Agate material prevents introduction of ferromagnetic impurities from the mortar itself [36]. |

| Test Sieve | For standardizing soil sample particle size for laboratory analysis. | 2 mm mesh sieve [36]. |

Hydrogeochemical modeling has become an indispensable tool for researchers investigating groundwater quality, particularly when studying cation exchange processes in coastal aquifers and contaminated sites. PHREEQC, a comprehensive computer program for simulating chemical reactions and transport processes in water, provides powerful capabilities for calculating saturation indices and performing inverse modeling to identify and quantify geochemical processes [38]. Within thesis research focused on correcting cation exchange effects, these modeling techniques enable scientists to decipher the complex interactions between water and aquifer materials, helping to explain observed changes in groundwater chemistry along flow paths and over time.

The program's inverse modeling capability is particularly valuable for testing hypotheses about reactions that account for differences in water composition between initial and final sampling points [38]. For researchers investigating cation exchange, PHREEQC can quantify the mole transfers of phases, including exchange species, that explain the evolution of water chemistry, thus providing crucial evidence for thesis conclusions about the impact of cation exchange on groundwater quality.

Theoretical Background: Saturation Indices and Inverse Modeling

Saturation Indices: Quantifying Mineral Equilibrium

Saturation indices (SI) provide a quantitative measure of a water's thermodynamic equilibrium with mineral phases. Calculated as SI = log(IAP/KT), where IAP is the ion activity product and KT is the solubility product constant at temperature T, these indices indicate whether a water is undersaturated (SI < 0), saturated (SI = 0), or supersaturated (SI > 0) with respect to specific minerals. In groundwater studies focused on cation exchange, saturation indices help researchers identify potential mineral dissolution or precipitation reactions that might accompany exchange processes.

For example, in managed aquifer recharge systems, the dissolution of carbonate minerals like calcite and siderite often occurs concurrently with cation exchange, affecting pH and ion concentrations in ways that can be misinterpreted without proper modeling [39]. By calculating saturation indices for relevant mineral phases, researchers can build more accurate conceptual models of the geochemical system they are studying.

Inverse Modeling: Identifying Reaction Pathways

Inverse modeling, also known as mole-balance modeling, determines sets of mineral and gas phase transfers that account for differences in water chemistry between an initial water (or mixture of waters) and a final water [40] [38]. This approach is particularly valuable for thesis research aimed at quantifying cation exchange effects, as it provides a mathematical framework for testing hypotheses about the reactions responsible for observed water quality changes.

The inverse modeling capability in PHREEQC includes isotope mole balance (though not isotope fractionation), allowing researchers to incorporate stable isotope data as additional constraints on reaction pathways [40] [41]. This is especially useful for tracing the sources of elements during cation exchange processes and verifying whether conceptual models of groundwater evolution are consistent with multiple lines of evidence.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Saturation Index Calculations

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected saturation indices | Incorrect database selection; incomplete water analysis; inaccurate pH/pe measurements | Verify database contains required phases; ensure all major ions measured; cross-check field parameters |

| Consistency issues between similar samples | Charge balance errors; unit conversion mistakes; analytical errors | Use charge balance correction; verify unit consistency; check analytical data quality |

| SIs contradict observed mineralogy | Kinetic limitations; non-equilibrium conditions; missing aqueous species | Consider kinetic reactions; verify assumed equilibrium validity; check database completeness |

Common Pitfalls and Solutions:

- Database Selection: Different PHREEQC databases (phreeqc.dat, wateq4f.dat, minteq.dat) contain different thermodynamic data for minerals and aqueous species. Always specify your database and verify it contains the phases relevant to your research, particularly when working with cation exchange phases [42].

- Charge Balance Errors: Large charge imbalances can significantly affect saturation index calculations. PHREEQC can adjust species concentrations to achieve charge balance, but understanding the source of imbalance (often missing analytical data for major ions) is crucial for thesis research quality [42].

- pH and Redox Effects: Small errors in pH measurement can substantially impact saturation indices for pH-sensitive minerals like carbonates and hydroxides. Similarly, incorrect pe values or redox couple definitions affect SI calculations for redox-sensitive minerals [42].

Troubleshooting Inverse Modeling

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No models found | Uncertainty limits too tight; missing phases; conceptual model incorrect | Widen uncertainty limits; include all possible reactants; reevaluate conceptual model |

| Too many models | Uncertainty limits too wide; insufficient constraints | Tighten uncertainty limits; add isotopic constraints; include more elements in balances |

| Physically unreasonable models | Missing constraints; problematic phase combinations | Apply dissolve/precipitate only constraints; add exchange capacity limits; use -force option judiciously |

Advanced Troubleshooting Strategies:

- Uncertainty Allocation: Properly assigning uncertainty limits is both art and science. For thesis research, consider analytical precision, spatial variability, and temporal changes when setting uncertainties. A common approach is to use 2-5% for major ions with good analytical precision and higher uncertainties (10-100%) for trace elements like iron [41].

- Phase Selection: Include all mineral and exchange phases potentially present in your aquifer system. For cation exchange studies, remember to define exchange species in EXCHANGE_SPECIES with proper stoichiometry, as inverse modeling uses only the reaction stoichiometry, not the log K values [41].

- Isotopic Constraints: When available, isotope data provide powerful constraints on inverse models. For example, in the Madison Aquifer inverse modeling, 13C and 34S values helped identify carbonate mineral reactions and sulfate reduction processes [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I fix pH at a specific value in my simulations?

A: To maintain a fixed pH during simulations, you can use the EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES data block with a fictional phase. First, define the phase in a PHASES block:

Then use it in EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES to add either acid or base as needed to maintain the desired pH:

This approach will add HCl or NaOH (depending on the specified formula) to maintain pH at 8.2 [42].

Q2: Why does my inverse model not include a specific phase (like fertilizer) even though I know it's present in my system?

A: If a phase doesn't appear in your inverse models, the most likely reason is that other phases in your model already account for the element balances. For example, if you include fertilizer as a phase but your final water shows no increase in phosphorus (or even a decrease), the model has no need for the fertilizer phase to explain the observed chemistry [43]. Review your conceptual model and verify that the elements provided by the missing phase aren't already accounted for by other phases.

Q3: How can I incorporate cation exchange into my forward or inverse models?

A: For inverse modeling, include exchange phases under the -phases identifier in the INVERSEMODELING data block. Use the exact stoichiometry of the exchange reaction as defined in your EXCHANGESPECIES. For forward modeling, define the exchange composition using the EXCHANGE data block, specifying the initial composition of exchange sites [44] [45]. When studying coastal aquifers where seawater intrusion causes cation exchange, typical reactions include NaX + Ca²⁺ = CaX₂ + 2Na⁺ and similar exchanges for Mg²⁺ and K⁺ [7] [46].

Q4: What should I do when my model produces physically impossible results?