Life Cycle Assessment in Green Chemistry: A Quantitative Framework for Sustainable Process Design in Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to evaluate the environmental performance of green chemistry innovations against conventional...

Life Cycle Assessment in Green Chemistry: A Quantitative Framework for Sustainable Process Design in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to evaluate the environmental performance of green chemistry innovations against conventional processes. It covers the foundational principles of LCA, detailed methodological steps for implementation, strategies to overcome common data and application challenges, and validation through real-world comparative case studies. By integrating LCA early in R&D, professionals can make data-driven decisions that substantiate sustainability claims, optimize resource efficiency, and mitigate unintended environmental trade-offs, ultimately guiding the development of truly greener biomedical solutions.

Foundations of LCA: Why It's Indispensable for Evaluating Green Chemistry

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized, science-based methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle [1] [2]. The "cradle-to-grave" approach provides a comprehensive assessment framework that tracks impacts from initial raw material extraction ("cradle") through manufacturing, distribution, use, and ultimately to disposal ("grave") [1] [3]. This holistic perspective is crucial for avoiding problem-shifting, where reducing environmental impacts in one life cycle stage inadvertently increases impacts in another stage or environmental category.

The international standards ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 provide the foundational framework for conducting LCA studies, ensuring methodological rigor, consistency, and credibility in environmental impact assessments [2] [3]. Within the pharmaceutical and chemical sectors, cradle-to-grave LCA is particularly valuable for evaluating the total environmental footprint of drug development processes, enabling researchers to identify significant impact hotspots across complex supply chains and product life cycles [4].

Conceptual Framework of Cradle-to-Grave LCA

Core Life Cycle Stages

The cradle-to-grave assessment encompasses five interconnected stages that collectively define a product's environmental trajectory. The diagram below illustrates the continuous flow of materials and energy through these stages, with associated inputs and outputs at each phase.

- Raw Material Extraction: This initial stage involves identifying energy usage and resource depletion associated with procuring starting materials, including the environmental impacts of mining, harvesting, or synthesizing fundamental chemical building blocks [1] [2].

- Manufacturing & Processing: This phase analyzes emissions, waste streams, and energy consumption during chemical synthesis, purification, and pharmaceutical formulation processes [1] [2].

- Transportation & Distribution: This stage assesses the carbon footprint and environmental impacts associated with logistics, including the transportation of raw materials, intermediates, and final products throughout the supply chain [1] [2].

- Usage & Retail: This phase measures energy and resource consumption during product use, which for pharmaceuticals may include considerations of administration methods, storage requirements, and metabolic fate [1] [3].

- Waste Disposal: The final stage evaluates the environmental impact of end-of-life management, including recycling, landfilling, incineration, or wastewater treatment of pharmaceutical products and packaging [1] [2].

Comparative LCA Approaches

While cradle-to-grave provides the most comprehensive assessment, other LCA approaches serve specific purposes in research and development contexts. The table below compares the key methodological boundaries and applications of different LCA types.

Table 1: Comparison of LCA Methodological Approaches

| Approach | System Boundaries | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cradle-to-Grave | Raw material extraction → Manufacturing → Transportation → Use → Disposal [1] [3] | Complete environmental footprint of end products [3]; Policy development; Consumer communication | Data-intensive; Complex modeling of use and disposal phases [3] |

| Cradle-to-Gate | Raw material extraction → Manufacturing → Transportation to factory gate [1] [3] | Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [1]; Screening assessments; Supply chain optimization | Excludes use and disposal impacts [3] |

| Gate-to-Gate | Single manufacturing or value-added process [1] | Process optimization; Internal environmental management | Limited scope; Requires linking with other assessments for complete picture [1] |

| Cradle-to-Cradle | Circular model: materials recycled into new products at end-of-life [1] [3] | Circular economy planning; Sustainable material selection | Requires specialized product design for material recovery [3] |

| Consequential LCA | Market-level analysis accounting for consequences of decisions [5] | Policy impact assessment; Strategic planning | Complex market modeling; Less standardized methodology [5] |

Experimental Protocols for LCA in Chemical Research

Standardized LCA Methodology

The ISO standards define four iterative phases for conducting a life cycle assessment. The workflow below outlines the sequence of stages, key tasks, and iterative refinement process that characterizes robust LCA practice.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The initial phase establishes the study's purpose, boundaries, and functional basis for comparison [1] [5] [2]:

- Goal Definition: Clearly state the intended application (e.g., eco-design, marketing claims, policy support), reasons for conducting the study, and intended audience [5]. For pharmaceutical applications, this may include comparing active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis routes.

- Scope Definition: Define the product system, including system boundaries, functional unit, allocation procedures, impact assessment methodology, and data quality requirements [5]. A typical functional unit for drug development might be "per kilogram of purified API" or "per defined daily dose."

- Boundary Selection: For cradle-to-grave assessments, include all life cycle stages from raw material acquisition through production, use, and end-of-life management [1].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The LCI phase involves systematic data collection on energy and material inputs and environmental releases throughout the product life cycle [2] [3]:

- Data Collection: Compile quantified inputs (materials, energy) and outputs (emissions to air, water, land) for all unit processes within the system boundaries [3]. Primary data should be preferred when available, supplemented by secondary data from commercial LCA databases.

- Data Categories: For chemical processes, essential data includes catalyst consumption, solvent losses, reaction energy requirements, purification yields, and waste treatment inputs/outputs [4].

- Data Quality Assessment: Document temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness of data sources, along with uncertainty ranges for key parameters [5].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The LCIA phase translates inventory data into potential environmental impacts [2] [3]:

- Selection of Impact Categories: Choose categories relevant to the product system, typically including global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, ozone depletion, photochemical oxidant formation, and resource depletion [2].

- Classification: Assign LCI results to relevant impact categories (e.g., classifying CO₂ and CH₄ emissions to global warming) [3].

- Characterization: Calculate category indicator results using characterization factors (e.g., converting all greenhouse gases to CO₂ equivalents using IPCC factors) [3].

Phase 4: Interpretation

The final phase involves evaluating study results to inform decision-making [2] [3]:

- Significance Analysis: Identify significant issues based on LCIA results, typically focusing on life cycle stages or processes contributing most to environmental impacts.

- Completeness and Sensitivity Checks: Verify that all necessary information is available and assess how sensitive results are to key methodological choices and data uncertainties.

- Conclusion and Reporting: Draw conclusions consistent with the goal and scope, explain limitations, and provide transparent reporting to enable critical review.

Quantitative Comparison: Green Chemistry vs Conventional Processes

Impact Category Comparison

Life cycle impact assessment quantifies environmental performance across multiple categories. The table below summarizes typical impact categories and characterization methods used in LCA studies of chemical processes.

Table 2: Life Cycle Impact Assessment Categories and Methods

| Impact Category | Indicator | Common Characterization Method | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming | Global Warming Potential (GWP) | IPCC factors (CO₂ equivalents) | kg CO₂-eq |

| Acidification | Acidification Potential | TRACI or CML models (SO₂ equivalents) | kg SO₂-eq |

| Eutrophication | Eutrophication Potential | EP model (PO₄ equivalents) | kg PO₄-eq |

| Ozone Depletion | Ozone Depletion Potential | ODP model (CFC-11 equivalents) | kg CFC-11-eq |

| Photochemical Oxidation | Smog Formation Potential | POCP model (C₂H₄ equivalents) | kg C₂H₄-eq |

| Resource Depletion | Abiotic Resource Depletion | CML or ReCiPe method (Sb equivalents) | kg Sb-eq |

Comparative LCA Data for Chemical Processes

Emerging research demonstrates the environmental advantages of green chemistry principles when applied to pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturing. The table below compares representative environmental impact data for conventional versus green chemistry processes across multiple studies.

Table 3: Comparative LCA Data: Green Chemistry vs Conventional Processes

| Process Type | Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂-eq/kg product) | Energy Demand (MJ/kg product) | Water Consumption (L/kg product) | Waste Generation (kg/kg product) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional API Synthesis | 150-300 [4] | 800-1,600 [4] | 5,000-20,000 [4] | 50-200 [4] |

| Green Chemistry Alternative | 50-120 [4] | 300-700 [4] | 1,000-5,000 [4] | 10-50 [4] |

| Conventional Solvent Production | 3-8 [4] | 60-150 [4] | 200-800 [4] | 1-5 [4] |

| Bio-based Solvent Alternative | 1-3 [4] | 30-80 [4] | 100-400 [4] | 0.5-2 [4] |

| Traditional Chemical Catalysis | 50-100 [4] | 300-600 [4] | 500-2,000 [4] | 10-30 [4] |

| Enzyme-catalyzed Process | 10-30 [4] | 100-250 [4] | 100-500 [4] | 2-8 [4] |

LCA Software and Databases

Table 4: Essential LCA Research Tools and Resources

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software Platforms | Commercial and open-source LCA software [6] | Modeling product systems; Impact calculation; Result visualization |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases | Ecoinvent, GaBi, ELCD, US LCI [7] | Secondary data for background processes (energy, materials, transport) |

| Impact Assessment Methods | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI, IMPACT World+ [7] | Converting inventory data to environmental impact scores |

| Chemical Process Simulators | Aspen Plus, ChemCAD, SuperPro Designer [4] | Generating process-specific inventory data for chemical operations |

| Digital Twin Applications | Digital twin technology [6] | Dynamic LCA; Scenario testing; Real-time process optimization |

Emerging Methodological Developments

The field of LCA continues to evolve with several emerging trends enhancing its applicability to chemical and pharmaceutical research:

- Dynamic LCA: Incorporates time-dependent inventory data and characterization factors to improve temporal resolution, particularly important for long-lived chemical compounds and carbon storage considerations [8].

- Real-time Impact Monitoring: Uses IoT sensors and AI-powered data collection to generate primary life cycle inventory data, increasing accuracy and enabling continuous environmental performance tracking [6] [8].

- Blockchain for Data Transparency: Provides secure, immutable records of supply chain data, addressing growing demands for verifiable environmental claims and reducing risks of greenwashing [6].

- Digital Twin Integration: Creates virtual replicas of physical systems to simulate environmental impacts of process modifications before implementation, significantly enhancing eco-design capabilities [6].

The cradle-to-grave Life Cycle Assessment framework provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive, standardized methodology for quantifying environmental impacts across the entire life cycle of chemical products and processes. By implementing the detailed experimental protocols outlined in this guide and applying the comparative analytical approaches presented, researchers can generate robust, decision-relevant environmental data to guide the development of more sustainable pharmaceutical products and processes. The continued evolution of LCA methodologies, particularly through digitalization and dynamic assessment capabilities, promises to further enhance its value as an essential tool for achieving sustainability goals in the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors.

The Critical Role of LCA in Moving Beyond Chemical Intuition

In the drive toward sustainable chemical processes, intuition is no longer sufficient. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a critical, non-negotiable tool for quantifying the true environmental footprint of chemical products and processes, moving beyond qualitative claims to data-driven decision-making. Green chemistry, guided by its 12 principles, aims to design safer, more efficient chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [9]. However, a process that appears greener based on a single metric—such as the use of renewable feedstocks—may inadvertently create higher energy demands or toxic byproducts elsewhere in its life cycle. LCA provides the comprehensive, quantitative framework necessary to identify these trade-offs and avoid costly missteps.

The methodology is standardized through ISO 14040 and 14044, ensuring rigorous and comparable assessments across different products and technologies [10] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, LCA shifts the paradigm from assumptions to evidence, validating that innovations in green chemistry deliver genuine, holistic environmental benefits rather than simply shifting burdens to other parts of the system.

LCA Methodology: A Framework for Objective Comparison

A Life Cycle Assessment is conducted through four interdependent phases, providing a structured framework for objective environmental comparison. This systematic approach is crucial for generating reliable, actionable data for research and development.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition: This foundational phase establishes the LCA's purpose, the product system to be studied, and the system boundaries (e.g., cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave). A critical output is defining the functional unit, which provides a standardized basis for comparison, such as "1 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)" [1] [11]. This ensures comparisons between alternative processes are equitable and meaningful.

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): This data-collection phase involves quantifying all relevant inputs and outputs across the product's life cycle. Inputs include raw materials, energy, and water, while outputs include emissions to air, water, land, and co-products [10] [11]. Data is sourced from direct measurement, process simulation, or commercial databases like Ecoinvent.

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): The inventory data is translated into potential environmental impacts using standardized categories. Key impact categories for green chemistry include [12] [11]:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP) in kg CO₂-equivalent.

- Human Toxicity and Ecotoxicity.

- Water Depletion and Eutrophication.

- Resource Depletion (fossil and mineral).

Phase 4: Interpretation: Findings from the inventory and impact assessment are synthesized to draw conclusions, identify environmental hotspots, and provide recommendations for improvement. This includes sensitivity and uncertainty analyses to test the robustness of the results [1] [11].

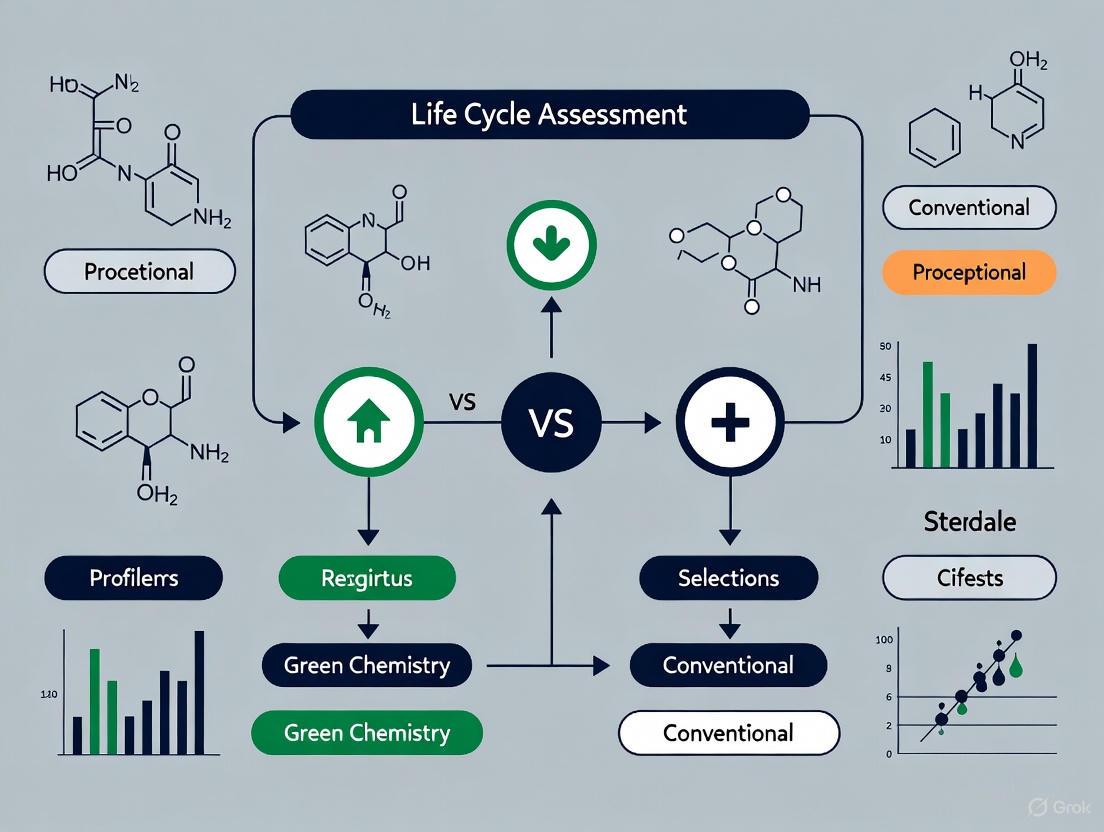

The logical flow and key outputs of this framework are illustrated below.

Quantitative Comparison: LCA Data for Conventional vs. Green Processes

LCA transforms subjective claims into objective, quantifiable data. The following tables summarize key environmental metrics for different chemical processes and materials, demonstrating how LCA enables direct comparison.

Comparative LCA of Urban Green Space Maintenance

This case study on urban management highlights how maintenance intensity drives environmental impact, a concept directly transferable to chemical process operations.

Table 1: LCA of Urban Green Spaces (Functional Unit: 1 m² over 30 years) [12]

| Green Space Type | Maintenance Intensity | Climate Change (kg CO₂ eq.) | Impact Hotspot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utility Lawn (UL) | Intensive | 54.59 | Maintenance phase (fertilizer, frequent mowing) |

| Meadow Lawn (ML) | Extensive | 2.90 | Maintenance phase (significantly reduced) |

| Perennial Bed | Extensive | 10.68 | Maintenance phase |

Comparative LCA of Catalyst Production Methods

The production of catalysts is a common and often energy-intensive step in chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical manufacturing. LCA reveals the profound benefits of process intensification.

Table 2: LCA of Catalyst Production from Solid Waste [13]

| Production Parameter | Conventional Method | Intensified Method (e.g., Ultrasound) | LCA-Based Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Temperature | >600°C to <900°C | <100°C | ~80-90% reduction in energy demand for heating |

| Reaction Time | 4-5 hours | <100 minutes | >50% reduction in process energy and increased throughput |

| Overall Energy Consumption | High | Significantly Lower | Intensified methods minimize the embedded energy of the catalyst, a major contributor to the lifecycle impact of the final chemical product. |

LCA of Pharmaceutical Synthesis: A Solvent Case Study

The pharmaceutical industry is a major consumer of solvents. LCA is critical for evaluating the trade-offs when adopting greener alternatives.

Table 3: LCA of API Synthesis - Edoxaban (Oral Anticoagulant) [14]

| Process Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Enzymatic Synthesis (Green Chemistry) | LCA-Verified Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvent Usage | Baseline | Reduced by ~90% | Lower emissions of VOCs, reduced human toxicity potential, and lower waste management footprint. |

| Raw Material Costs | Baseline | Decreased by ~50% | Improved atom economy and reduced resource depletion impact. |

| Process Complexity | 7 Filtration Steps | Reduced to 3 Steps | Lower energy and water consumption associated with downstream processing. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for LCA-Informed Green Chemistry

For LCA data to be valid and comparable, it must be grounded in robust and clearly documented experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key green chemistry processes that have been evaluated through LCA.

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis of Waste-Derived Catalysts

This protocol outlines an intensified method for producing heterogeneous catalysts from solid waste, a process demonstrated to have a significantly lower lifecycle impact than conventional methods [13].

- Objective: To synthesize a solid base catalyst from waste biomass (e.g., eggshells, fruit peels) for application in transesterification or other organic reactions.

- Materials:

- Precursor: Waste biomass (e.g., calcined eggshells for CaO).

- Reactor: Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator (e.g., 20-40 kHz).

- Solvent: Water or mild solvent.

- Procedure:

- Pretreatment: Wash the waste biomass and dry at 110°C for 24 hours. For eggshells, calcine in a muffle furnace at 900°C for 2 hours to convert CaCO₃ to CaO.

- Activation: Disperse the calcined powder in deionized water at a 1:10 mass ratio.

- Ultrasound Treatment: Subject the suspension to ultrasound irradiation using a probe sonicator. Maintain the temperature below 80°C using an ice bath. Typical parameters: 100 W/cm² intensity for 30-60 minutes.

- Recovery: Recover the solid catalyst by vacuum filtration.

- Drying: Dry the catalyst in an oven at 105°C for 12 hours.

- Characterization: Analyze the catalyst using XRD, SEM, and BET surface area analysis to confirm structure and morphology.

- LCA Data Collection Points:

- Energy Input: Precisely record electricity consumption (kWh) of the furnace (calcination) and sonicator (activation).

- Material Input: Mass of raw waste, water, and other chemicals.

- Outputs: Mass of final catalyst, any waste streams.

Protocol 2: Enzymatic Synthesis in Aqueous Medium

This protocol describes a green chemistry route for synthesizing a target molecule, such as an API intermediate, using enzyme catalysis, which drastically reduces solvent-related environmental impacts [14].

- Objective: To catalyze a specific transformation (e.g., hydrolysis, esterification) using an enzyme in water, replacing a traditional metal catalyst or stoichiometric reagent in an organic solvent.

- Materials:

- Enzyme: Commercial lipase, protease, or other specific enzyme (e.g., 1000 U/mg).

- Substrates: Relevant starting materials for the reaction.

- Solvent: Deionized water or buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Reactor: Jacketed glass reactor with magnetic stirring.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Charge the aqueous buffer and substrates into the reactor. Equip the reactor with a temperature probe.

- Initiation: Add the enzyme to the reaction mixture with gentle stirring.

- Incubation: Maintain the reaction at the specified temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) and pH. Monitor reaction progress by TLC or HPLC.

- Termination: Upon completion, heat the mixture to 80°C for 10 minutes to denature the enzyme.

- Product Isolation: Extract the product with a benign solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) or use direct crystallization. Filter and dry the product.

- LCA Data Collection Points:

- Material Input: Mass of enzyme, substrates, water, and extraction solvent.

- Energy Input: Electricity for temperature control and stirring.

- Outputs: Mass of pure product, aqueous waste stream (characterized for BOD/COD if needed).

Visualizing the Comparative LCA Workflow

The following diagram maps the logical process of using LCA to compare a conventional chemical process with a proposed green alternative, highlighting key decision points and trade-offs that researchers must consider.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Technologies for LCA-Informed Research

For researchers aiming to design and validate green chemistry processes, specific reagents, technologies, and software are essential. This toolkit details critical items that facilitate the development of processes with a demonstrably superior lifecycle profile.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chemistry & LCA

| Tool Category | Specific Item / Technology | Function in Green Chemistry | Relevance to LCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Catalysts | Enzymes (Lipases, Proteases) | Biocatalysts for selective synthesis under mild, aqueous conditions [14]. | Drastically reduce energy (GWP) and solvent use (toxicity) impacts vs. metal catalysts. |

| Waste-Derived Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., CaO from eggshells) | Low-cost, renewable solid catalysts for reactions like transesterification [13]. | Valorizes waste, reducing resource depletion and waste disposal impacts. | |

| Benign Solvents | Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Customizable, biodegradable solvents for extraction and synthesis [15]. | Replace volatile organic compounds (VOCs), reducing air pollution and toxicity impacts. |

| Water | Non-toxic, non-flammable solvent for "on-water" or in-water reactions [15]. | Eliminates concerns over solvent production, emission, and disposal. | |

| Process Technologies | Mechanochemistry (Ball Milling) | Solvent-free synthesis using mechanical force to drive reactions [15]. | Eliminates solvent-related impacts entirely, a major LCA hotspot. |

| Ultrasound & Microwave Reactors | Intensification technologies to enhance reaction rates and yields under milder conditions [13]. | Reduce reaction time and temperature, directly lowering energy consumption (GWP). | |

| LCA & Analysis Software | Ecochain Helix/Mobius, GaBi, OpenLCA | Software platforms for modeling and calculating lifecycle environmental impacts [10] [1]. | Provides the essential quantitative data to validate "green" claims and guide R&D. |

The integration of Life Cycle Assessment into green chemistry R&D is fundamental for progress that is both scientifically sound and genuinely sustainable. For researchers and drug development professionals, LCA provides the critical evidence needed to move beyond chemical intuition, enabling objective comparisons, revealing hidden trade-offs, and validating the environmental superiority of new technologies. By adopting the methodologies, tools, and data-driven mindset outlined in this guide, scientists can ensure their innovations contribute meaningfully to a circular economy and a reduced ecological footprint, transforming green chemistry from a conceptual framework into a quantifiable reality.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product or service throughout its entire life. The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards provide the framework for conducting these assessments, which involve compiling an inventory of relevant energy and material inputs and environmental releases, then evaluating the potential impacts associated with those inputs and releases [16] [1]. The choice of life cycle model—also known as setting the system boundary—is a critical first step that determines which stages of a product's life are included in the analysis [17] [18]. For researchers in green chemistry and pharmaceutical development, selecting the appropriate model is essential for obtaining accurate, relevant data to guide sustainable process design, material selection, and supply chain management.

This guide provides a detailed comparison of the three core LCA models: Cradle-to-Grave, Cradle-to-Gate, and Cradle-to-Cradle. It is structured to help scientists and drug development professionals understand the applications, requirements, and outputs of each model, enabling informed decisions for environmental impact assessments of chemical processes and pharmaceutical products.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, typical applications, and outputs of the three primary LCA models.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Core LCA Models

| Feature | Cradle-to-Gate | Cradle-to-Grave | Cradle-to-Cradle |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Boundary | From raw material extraction ("cradle") to the factory gate [17] [18]. | From raw material extraction to final disposal ("grave") [17] [18]. | From raw material extraction through use and into a new cycle, avoiding waste [17] [19]. |

| Stages Included | 1. Raw Material Extraction2. Manufacturing & Processing [17] [18] | 1. Raw Material Extraction2. Manufacturing & Processing3. Transportation & Distribution4. Product Use & Maintenance5. End-of-Life Disposal [17] [18] | 1. Raw Material Extraction2. Manufacturing & Processing3. Transportation & Distribution4. Product Use & Maintenance5. Recycling/Reprocessing for new product life [17] [19] |

| Primary Application | B2B communication, Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), internal process optimization, supplier selection [16] [18]. | Comprehensive product footprint, consumer-facing claims, identifying burden-shifting, full impact management [17] [18]. | Circular economy strategies, certifying products for closed-loop cycles, designing out waste [17] [19]. |

| Key Output | Environmental impact up to the point of sale, often used for procurement decisions [20]. | Total environmental footprint across the product's entire linear life, from creation to disposal [17]. | Assessment of a product's suitability for circular systems and its net-positive impact potential. |

| Complexity & Data Needs | Lower complexity; requires data on internal processes and supply chain [18]. | High complexity; requires additional data on logistics, consumer use, and end-of-life treatment [17] [21]. | Very high complexity; requires data on recyclability, material health, and renewable energy use [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the system boundaries and material flows for each LCA model, highlighting their core structural differences.

Detailed Methodologies and Data Requirements

Cradle-to-Gate Methodology

The Cradle-to-Gate model assesses a partial product life cycle, from resource extraction (cradle) until the product leaves the factory gate [18]. This scope is particularly relevant for business-to-business (B2B) communication and generating Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [16] [1].

Experimental & Data Protocol:

- Goal and Scope Definition (ISO 14040): Define the functional unit (e.g., per kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient) and system boundaries, explicitly excluding use and end-of-life phases [1].

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

- Raw Materials: Quantify all inputs from nature, including ores, minerals, water, and biomass. For green chemistry, this includes biobased feedstocks [16] [1].

- Manufacturing & Processing: Collect primary data on energy carriers (electricity, natural gas), utilities, process emissions, and production waste from internal operations. Data should be sourced from reliable suppliers using standardized templates [16].

- Data Gaps: When primary data is unavailable, fill gaps using estimations from established LCA databases like Ecoinvent or the U.S. Federal LCA Commons [16] [22].

Cradle-to-Grave Methodology

Cradle-to-Grave analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of a product's environmental footprint by including all five life cycle stages [17] [18]. It is essential for identifying whether improvements in one stage (e.g., production) simply shift environmental burdens to another (e.g., use or disposal)—a key concern for regulatory bodies and consumer-facing claims [17].

Experimental & Data Protocol:

- Goal and Scope: In addition to the Cradle-to-Gate scope, define assumptions for the use and end-of-life phases [17].

- Life Cycle Inventory - Extended Phases:

- Transportation & Distribution: Model the transport of the finished product to retailers and consumers, including distances and modes (ship, rail, truck, air) [17] [18].

- Usage & Retail: Model the energy, water, and consumables required during the product's use phase. For pharmaceuticals, this may include refrigeration, patient transport, or ancillary materials. Assumptions about product lifetime and usage patterns are critical [17] [20].

- End-of-Life (Grave): Determine the likely waste treatment pathways (landfill, incineration, composting) based on national statistics. Collect data on the emissions and potential energy recovery from these processes [17].

Cradle-to-Cradle Methodology

Cradle-to-Cradle (C2C) is a circular model that exchanges the waste stage with a process that makes materials reusable, thus "closing the loop" [17] [19]. It designs products so that at their end-of-life, materials become "nutrition" for either new industrial cycles (technical nutrients) or biological cycles (biological nutrients) [19].

Experimental & Data Protocol:

- Goal and Scope: The scope is analogous to Cradle-to-Grave but with a critical focus on closed-loop end-of-life options [18].

- Life Cycle Inventory - Circular Flows:

- Material Health: Classify all materials as technical or biological nutrients and assess their safety for continuous cycles [19].

- Design for Disassembly: Model the processes required for product take-back, disassembly, and material recovery.

- Recycling/Upcycling: Collect data on the energy, water, and emissions for recycling processes that return materials to a quality level sufficient to replace virgin materials in an identical or similar product [17] [19].

- Challenges: This model requires a reliable supply chain for returned products and can lack flexibility for product line diversification once established [19].

Quantitative Impact Comparison

The environmental impact results of an LCA are typically reported across multiple impact categories. The table below shows a hypothetical comparison of a conventional chemical process versus a green chemistry alternative, assessed under different models. Note that the values are illustrative.

Table 2: Illustrative LCA Results for a Chemical Product (per Functional Unit)

| Impact Category | Unit | Cradle-to-Gate | Cradle-to-Grave | Cradle-to-Cradle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | kg CO₂ eq | 15.2 | 45.8 | 32.1 |

| - of which: Production | kg CO₂ eq | 15.2 | 15.2 | 15.2 |

| - of which: Use Phase | kg CO₂ eq | n/a | 28.5 | 28.5 |

| - of which: End-of-Life | kg CO₂ eq | n/a | 2.1 | -11.6 (credit) |

| Freshwater Ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.85 |

| Land Use | m²a crop eq | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

Interpretation of Results:

- Cradle-to-Gate only reveals the production impact, missing the significant use-phase emissions evident in the Cradle-to-Grave results [20].

- Cradle-to-Grave provides the full picture, showing that the use phase is the largest contributor to the carbon footprint. This highlights the risk of burden-shifting if only a Cradle-to-Gate perspective is used [17].

- Cradle-to-Cradle shows a negative value (credit) for end-of-life due to the avoided production of virgin materials through recycling. This demonstrates the potential of circular strategies to reduce the overall footprint, though impacts in other categories may persist [19].

Conducting a robust LCA requires access to specialized software, databases, and methodological guides. The following table lists key resources relevant to researchers.

Table 3: Essential Resources for LCA Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Green Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Federal LCA Commons [22] | Data Repository | A central access point for LCA data repositories, including USLCI and sector-specific data (e.g., construction, electricity). | Provides region-specific background data for energy and material flows in the US. |

| Ecoinvent Database [16] | Database | A comprehensive, widely used international database for LCI data. | Offers background data on conventional and some emerging chemical processes. |

| TRACI [22] | Impact Assessment Method | EPA's tool for characterizing environmental impacts, with factors tailored to North America. | The standard method for assessing impacts in studies involving North American processes. |

| GLAD [7] | Data Platform | The Global LCA Data Access network, promoting data sharing and interoperability. | A platform to access and share data for biobased materials or new chemical processes. |

| ISO 14040/14044 [16] | Standard | The international standards outlining the principles and framework for conducting an LCA. | Ensures methodological rigor and credibility of the assessment. |

Critical Considerations for Model Selection

Benefits and Limitations in Practice

Each model offers distinct advantages and faces specific limitations that researchers must consider.

- Cradle-to-Gate is less complex and costly, making it a practical starting point [18]. However, its limited scope risks burden-shifting, where optimizing production inadvertently increases downstream impacts [17].

- Cradle-to-Grave offers the most complete picture for decision-making, crucial for products whose main impacts occur during use (e.g., solvents requiring energy-intensive handling) [17] [20]. Its key challenge is data intensity, particularly in modeling consumer behavior and end-of-life scenarios, which can introduce uncertainty [17] [21].

- Cradle-to-Cradle aligns with circular economy goals and can reveal net-positive impacts through material recovery [19]. Its primary limitations are implementation complexity and a currently immature infrastructure for closed-loop cycles for many technical materials, making it difficult to execute reliably [19].

Comparability and Standardization

A significant challenge in LCA is the difficulty in comparing studies. Variations in scope definition, data quality, background databases, and underlying assumptions can make direct comparisons misleading [16]. For example, comparing a Cradle-to-Gate study of one material to a Cradle-to-Grave study of another is not valid. Therefore, a fair comparison requires using the same scope, methodology, and database for all assessed options [16].

Selecting the appropriate LCA model is a foundational decision that directly shapes the insights and sustainability decisions for researchers in green chemistry and pharmaceutical development.

- Use Cradle-to-Gate for B2B communication, EPDs, and internal process optimization where downstream stages are unknown or uniform.

- Use Cradle-to-Grave for a complete environmental footprint, consumer-facing claims, and to avoid burden-shifting when the full life cycle is known and manageable.

- Use Cradle-to-Cradle to design and evaluate circular systems where the goal is to eliminate waste and create closed-loop material cycles.

A rigorous LCA, regardless of the chosen model, relies on high-quality data, transparency in assumptions, and adherence to international standards. By applying these models correctly, scientists can generate reliable, actionable data to drive meaningful environmental improvements in chemical and pharmaceutical innovation.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a systematic, ISO-standardized framework for quantifying the environmental impacts of a product or process throughout its entire life cycle. For researchers and professionals in drug development and green chemistry, LCA offers a powerful tool to move beyond traditional metrics—such as atom economy and E-factors—towards a holistic understanding of environmental trade-offs, including global warming potential, resource depletion, and human toxicity [23]. The framework is governed by two cornerstone international standards: ISO 14040, which outlines the principles and framework, and ISO 14044, which provides detailed requirements and guidelines [24] [25]. These standards ensure that assessments are credible, reproducible, and fit for purpose, whether for internal decision-making, public disclosure, or regulatory compliance [26].

The LCA process is built upon four interdependent phases that form an iterative cycle: Goal and Scope Definition, Life Cycle Inventory (LCI), Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA), and Interpretation [26] [27]. This structured approach is particularly valuable for comparing innovative green chemistry pathways against conventional synthetic processes, enabling data-driven decisions that align with broader sustainability goals [23]. The following sections detail each stage, with a specific focus on their application in pharmaceutical and chemical research.

Stage 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The first and foundational stage of an LCA is the Goal and Scope Definition. This phase sets the direction and boundaries for the entire study, ensuring that the subsequent analysis is focused, relevant, and aligned with its intended application [26] [27].

Defining the Goal

According to ISO 14040, a robust goal statement must explicitly address several key components [26]:

- Intended Application: The purpose of the study (e.g., comparing the environmental performance of a green chemistry route to a conventional process, internal research & development, or supporting an Environmental Product Declaration).

- Reasons for Carrying Out the Study: The motivations, such as identifying environmental hotspots in a synthesis pathway or selecting the least impactful solvent system.

- Target Audience: The intended readers of the results, whether internal R&D teams, senior management, regulatory bodies, or the scientific community.

- Public Release of Results: Whether the results will be disclosed publicly and if they will be used to make comparative assertions.

Defining the Scope

The scope elaborates on the technical plan to achieve the goal. Key elements include [26] [27] [28]:

- Functional Unit: A quantified description of the primary function of the system that serves as a reference for all inputs and outputs. In chemical synthesis, this could be "the production of 1 kilogram of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) at 99.5% purity." This unit ensures comparability between alternative processes.

- System Boundary: Defines the processes to be included in the assessment. A "cradle-to-grave" boundary encompasses everything from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal of the product. For chemical processes, a "cradle-to-gate" boundary (from raw material to the factory gate) is often used for business-to-business comparisons [1]. Critical decisions involve whether to include capital equipment, laboratory infrastructure, and transportation.

- Assumptions and Limitations: All relevant assumptions, data quality requirements, and cut-off criteria must be documented to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

- Allocation Procedures: Addresses how environmental burdens are partitioned when a process yields multiple products (e.g., in a multi-step synthesis where intermediates are branched).

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in this first stage.

Application in Green Chemistry: A Comparative Framework

For research comparing green and conventional chemical processes, the goal and scope must be defined with precision to ensure a fair and meaningful comparison.

Table 1: Defining Goal and Scope for Green vs. Conventional Chemistry LCA

| Component | Application in Green Chemistry LCA | Application in Conventional Chemistry LCA | Critical Considerations for Comparability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Unit | "Synthesis of 1 kg API using bio-catalytic route" | "Synthesis of 1 kg API using traditional metal-catalyzed route" | The defined function (e.g., kg of product, potency) must be identical. |

| System Boundary | Often includes agricultural feedstock production (if biobased), low-energy purification (e.g., membrane filtration). | Often includes mining for metal catalysts, energy-intensive distillation, and waste solvent incineration. | System boundaries must be equivalent; a cradle-to-gate approach is typical. |

| Key Assumptions | Biogenic carbon is carbon-neutral; solvents are biodegradable. | Fossil-based inputs; waste treatment follows standard industrial protocols. | Assumptions must be stated transparently as they significantly influence results. |

| Allocation | May require allocation between pharmaceutical product and co-products in biorefinery model. | May require allocation for multi-purpose chemical plants producing various intermediates. | The same allocation method (e.g., mass, economic) must be applied to both systems. |

Stage 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) stage is the labor-intensive data collection phase of the LCA. It involves compiling and quantifying all relevant inputs and outputs—energy, raw materials, emissions, and wastes—associated with the product system within the predefined scope [26] [27].

LCI Methodology and Data Collection

The process of creating a life cycle inventory involves several key steps [26]:

- Preparation for Data Collection: The goal and scope definition guides the planning of data collection efforts.

- Data Collection: Gathering information on all inputs (e.g., reagents, solvents, energy) and outputs (e.g., air emissions, aqueous waste, solid waste) for every process within the system boundary.

- Data Validation: Ensuring the accuracy, consistency, and quality of the collected data, even when sourced from external databases.

- Data Allocation: Partitioning inputs and outputs when dealing with multi-functional processes (e.g., a chlor-alkali plant producing both chlorine and sodium hydroxide).

- Relating Data to the Functional Unit: All collected data is quantitatively related to the functional unit (e.g., all inputs needed to produce 1 kg of API).

- Data Aggregation: Compiling all the validated data into a comprehensive inventory of elementary flows.

In a research context, data quality is paramount. The LCI relies on two primary types of data [27] [28]:

- Primary Data: Site-specific, measured data collected directly from laboratory experiments or pilot-scale operations. This includes masses of reactants, solvent volumes, electricity consumption of reactors, and measured emission factors. Primary data is highly accurate and specific but can be costly and time-consuming to gather.

- Secondary Data: Data obtained from literature, industry averages, or LCA databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi). This is often used for background processes like electricity grid mix, raw material extraction, or standard waste treatment processes. While less specific, it is essential for completing the inventory.

A rigorous LCI requires thorough Quality Assurance, often evaluated using data quality indicators (DQIs) that assess precision, completeness, and representativeness [28].

Experimental Protocol for LCI in Chemical Synthesis

For researchers conducting an LCA of a chemical process, the following protocol ensures a robust inventory.

Protocol 1: Life Cycle Inventory Data Collection for a Chemical Reaction

- Material Inputs: Precisely weigh all reagents, catalysts, and solvents used in the reaction and subsequent work-up/purification. Record their purities and sources.

- Energy Inputs: Monitor or calculate the total energy consumption. For laboratory-scale assessments, this involves:

- Heating/Cooling: Record the power rating of hot plates, heating mantles, or cryostats and their operational duration.

- Stirring & Equipment: Record the power consumption of overhead stirrers, pumps, and other ancillary equipment.

- Other Utilities: Note consumption of compressed gases, vacuum, or chilled water.

- Outputs - Product: Accurately weigh and determine the purity of the final product and any isolated co-products.

- Outputs - Waste:

- Solid Waste: Weigh all solid wastes, including spent catalysts, filter aids, and purification media (e.g., silica gel).

- Liquid Waste: Measure the volume and characterize the composition of all aqueous and organic waste streams to the extent possible.

- Air Emissions: Estimate or model volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from solvent use and potential acid gases based on reaction chemistry.

Table 2: Life Cycle Inventory Data Table for Synthesizing 1 kg of API

| Inputs | Quantity | Unit | Data Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Materials | ||||

| Starting Material A | 1.8 | kg | Lab measurement (Primary) | 95% purity |

| Catalyst (Pd/C) | 0.05 | kg | Lab measurement (Primary) | 5 wt% loading |

| Solvent (Acetone) | 12.0 | L | Lab measurement (Primary) | |

| Energy | ||||

| Electricity | 45.0 | kWh | Calculated (Primary) | For stirring & heating (4 hrs) |

| Steam | 8.5 | kg | Database (Secondary) | For solvent recovery |

| Outputs | Quantity | Unit | Data Source | Notes |

| Products | ||||

| Target API | 1.0 | kg | Lab measurement (Primary) | 99.5% purity |

| Emissions to Air | ||||

| VOC (as Acetone) | 0.6 | kg | Modeled (Primary) | Based on vapor pressure & handling |

| Waste to Treatment | ||||

| Aqueous Waste | 5.5 | L | Lab measurement (Primary) | From aqueous work-up |

| Solid Waste (slag) | 0.3 | kg | Database (Secondary) | Incineration of spent catalyst |

Stage 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase translates the inventory data from the LCI into potential environmental impacts. This is where quantitative flows of resources and emissions are converted into indicator results that reflect their contribution to specific environmental problems, such as climate change or toxicity [26] [27].

The LCIA Procedure

The ISO standards define mandatory and optional elements for the LCIA. The mandatory steps are [26]:

- Selection of Impact Categories: Choosing environmental issues of concern relevant to the study's goal. Common categories include Global Warming Potential (GWP), Acidification Potential, and Eutrophication Potential.

- Classification: Assigning each LCI result (e.g., kg of CO2, kg of NOx) to the impact category it influences.

- Characterization: Modeling the LCI results within each category using scientifically established characterization factors. This converts and aggregates different substances into a common unit (e.g., all greenhouse gases are converted to kg of CO2-equivalents based on their radiative forcing potential).

Optional steps include Normalization (expressing results relative to a reference value), Grouping, and Weighting (aggregating impact scores into a single value, which is restricted for public comparisons) [26] [27].

Impact Categories Relevant to Green Chemistry

For comparing chemical processes, a multi-category perspective is essential, as a process that is superior in terms of carbon footprint might perform poorly on toxicity or resource depletion.

Table 3: Key Life Cycle Impact Categories for Chemical Process Assessment

| Impact Category | Description | Common Unit | Example Contributing LCI Flows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Contribution to greenhouse effect leading to climate change. | kg CO₂-eq | Carbon dioxide (CO₂), Methane (CH₄), Nitrous oxide (N₂O) |

| Acidification Potential | Potential to acidify soil and water bodies. | kg SO₂-eq | Sulfur oxides (SOₓ), Nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) |

| Eutrophication Potential | Potential to over-fertilize water and soil, leading to ecosystem imbalance. | kg PO₄³⁻-eq | Phosphates (PO₄³⁻), Nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) |

| Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (POCP) | Potential to form ground-level (smog) ozone. | kg Ethene-eq | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), Carbon monoxide (CO) |

| Resource Depletion (Abiotic) | Depletion of non-living resources (e.g., fossils, minerals). | kg Sb-eq | Crude oil, Natural gas, Metal ores (e.g., for catalysts) |

| Human Toxicity (non-cancer/cancer) | Potential harm to human health from toxic substances. | CTUh (Comparative Toxic Unit) | Emissions of heavy metals, formaldehyde, benzene |

The following diagram maps the logical flow of the LCIA phase, showing how inventory data is processed into meaningful environmental impact scores.

Experimental Data: Illustrative LCIA Results

The table below provides hypothetical, yet realistic, characterization results for the synthesis of 1 kg of an API via two different routes, demonstrating how LCIA data can be presented for comparison.

Table 4: Comparative LCIA Results for Green vs. Conventional Synthesis of 1 kg API

| Impact Category | Unit | Conventional Process (Route A) | Green Chemistry Process (Route B) | Notes on Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | kg CO₂-eq | 215 | 98 | Route B's lower GWP is likely due to renewable energy and biobased feedstock. |

| Acidification Potential | kg SO₂-eq | 0.85 | 0.31 | Lower acidification often correlates with reduced fossil fuel combustion. |

| Eutrophication Potential | kg PO₄³⁻-eq | 0.12 | 0.15 | Slightly higher eutrophication in Route B could be linked to agricultural fertilizer use for biobased feedstock. |

| Resource Depletion (Abiotic) | kg Sb-eq | 3.5 | 1.2 | Significant savings in fossil resource depletion for the green route. |

| Human Toxicity (non-cancer) | CTUh | 1.2E-06 | 5.1E-07 | The green route shows a clear advantage, possibly due to the avoidance of toxic metal catalysts or chlorinated solvents. |

Stage 4: Interpretation

The Interpretation stage is the final phase of the LCA, where the results from the Inventory (LCI) and Impact Assessment (LCIA) are systematically evaluated to draw conclusions, explain limitations, and provide actionable recommendations in line with the study's goal [26] [27]. This phase ensures that the complex data generated is translated into meaningful insights.

The Interpretation Process

According to ISO 14043, the interpretation should include three key elements [26]:

- Identification of Significant Issues: Based on the LCI and LCIA results, this step identifies the life cycle stages, processes, or substances that contribute most significantly to the overall environmental impacts (often called "hotspots"). For example, a contribution analysis can reveal whether the energy-intensive purification step or the resource-intensive raw material extraction is the dominant driver for GWP.

- Evaluation: This step assesses the reliability of the study through:

- Completeness Check: Ensuring all relevant data and information are included.

- Sensitivity Check: Determining how sensitive the results are to changes in key parameters (e.g., data sources, allocation methods, assumptions about energy mix). This helps gauge the robustness of the conclusions.

- Consistency Check: Verifying that the assumptions, methods, and data are consistent with the goal and scope throughout the study.

- Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations: Summarizing the findings in a fair and accurate manner, explicitly stating the study's limitations, and providing science-based recommendations for reducing environmental impacts or for further research.

Application: Interpreting Comparative LCAs

In the context of comparing green and conventional chemistry, the interpretation phase is where the trade-offs are analyzed. As seen in Table 4, a process might be superior in most categories but have a higher impact in one (e.g., Eutrophication Potential for the green route). The interpretation must weigh these trade-offs and provide clear guidance. The conclusions should answer the initial question posed in the goal, such as: "Under which conditions does the green chemistry route offer a net environmental benefit?" and "What specific aspects of the process should be targeted for further optimization?"

The Researcher's Toolkit for LCA

Conducting a rigorous LCA requires a suite of methodological tools and resources. The table below details key components of the LCA toolkit for researchers in drug development and green chemistry.

Table 5: Essential LCA Research Toolkit for Chemical Processes

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in LCA | Example Solutions / Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | Software Platform | Provides the core framework for modeling product systems, managing data, and performing LCIA calculations. | SimaPro, GaBi, OpenLCA, Sphera |

| Life Cycle Inventory Database | Data | Provides pre-compiled, secondary data for background processes (e.g., energy generation, chemical production, transport, waste treatment). | Ecoinvent, GaBi Databases, ELCD (European Life Cycle Database) |

| Impact Assessment Method | Methodology | A set of characterized models that define the impact categories and provide the characterization factors for the LCIA. | ReCiPe, IMPACT World+, CML-IA, TRACI |

| Product Category Rules (PCR) | Guidance | Provides sector-specific, detailed instructions for conducting LCAs for a particular product category (e.g., chemicals, plastics) to ensure comparability. | PCR defined by program operators (e.g., for EPDs) |

| Carbon Footprint Standard | Standard | Provides specific requirements for quantifying and reporting the carbon footprint of products, complementing broader LCA standards. | ISO 14067, GHG Protocol Product Standard |

| Uncertainty & Sensitivity Analysis | Analytical Tool | Methods and software features used to quantify uncertainty in the data and test how sensitive the results are to key assumptions. | Monte Carlo simulation (integrated in major LCA software) |

Identifying Environmental Hotspots from Raw Material Extraction to End-of-Life

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a standardized, systematic framework for evaluating the environmental impacts of a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to end-of-life disposal ("grave") [11]. For researchers and scientists in chemistry and drug development, LCA transitions sustainability from a conceptual goal to a quantifiable, actionable science. It moves beyond single-metric analyses (like carbon emissions) to provide a multi-dimensional view of environmental performance, capturing trade-offs between various impact categories such as water use, toxicity, and resource depletion [11].

Within the discipline of green chemistry, LCA acts as a critical validation tool. It offers the quantitative backbone needed to assess whether a new, "benign by design" chemical synthesis or drug production process genuinely reduces the overall environmental footprint when all stages of its life are considered [29] [11]. A core strength of LCA is its ability to pinpoint environmental hotspots—the specific stages, processes, or materials responsible for the most significant environmental impacts [30]. Identifying these hotspots allows researchers and product developers to focus their innovation efforts where they will yield the greatest environmental benefits, guiding strategic decision-making in R&D and process design [30].

Methodological Framework for Hotspot Analysis

The LCA process for identifying hotspots is structured into four distinct phases, as defined by ISO standards 14040 and 14044 [11]. The following workflow visualizes this structured procedure and its key outputs for hotspot analysis.

Figure 1: The LCA Methodology Workflow for identifying environmental hotspots, based on ISO 14040/14044 stages [11].

Defining Goal, Scope, and System Boundaries

The first, critical step is to define the goal and scope of the LCA. This includes specifying the functional unit, which provides a quantified reference to which all inputs and outputs are normalized (e.g., "per 1 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient" or "per single dose of medication"), ensuring fair comparisons [11]. Equally important is setting the system boundary, which dictates which life cycle stages are included in the assessment.

In chemical and pharmaceutical contexts, a cradle-to-gate approach is often employed. This boundary includes impacts from raw material extraction (cradle) up to the production of the finished chemical or active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) at the factory gate, excluding distribution, use, and end-of-life stages [29]. This is particularly relevant for intermediate chemicals with multiple downstream applications or for API synthesis, where the core chemical innovations occur [29]. However, if the compared alternatives have different use-phase efficiencies or end-of-life fates (e.g., a biodegradable polymer vs. a conventional one), a cradle-to-grave boundary is necessary to capture all significant impacts [29].

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) and Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase is the most data-intensive, involving the compilation and quantification of all relevant energy, material inputs, and environmental releases (emissions to air, water, soil) across the defined system boundary [11]. Data sources can include direct measurement, process simulation, and commercial databases like Ecoinvent or GaBi [11].

Subsequently, the Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase translates these inventory flows into potential environmental impacts. This involves classifying flows into specific impact categories and modeling their contributions. Common categories crucial for chemical and pharmaceutical assessments include [11]:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): Measured in kg CO₂-equivalent, representing contributions to climate change.

- Water Depletion: Quantifying freshwater consumption and potential for water stress.

- Human Toxicity: Estimating potential harm to human health from chemical exposures.

- Ecotoxicity: Assessing harmful effects on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

- Eutrophication: Measuring nutrient pollution leading to algal blooms in water bodies.

- Abiotic Resource Depletion: Concerning the consumption of finite non-living resources (e.g., minerals, fossil fuels).

Comparative LCA of Conventional vs. Green Chemical Processes

To illustrate the practical application of hotspot identification, we can compare a conventional chemical process to intensified, greener alternatives. A prominent example is the synthesis of solid catalysts from waste materials for applications like biodiesel production.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes experimental data comparing conventional synthesis to an ultrasound-assisted intensified process, highlighting differences in operating conditions, energy consumption, and performance.

Table 1: Comparative Experimental Data: Conventional vs. Intensified Catalyst Synthesis [13]

| Parameter | Conventional Synthesis | Ultrasound-Assisted Intensified Synthesis | Remarks / Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Temperature | High temperature: 600–900 °C (calcination) [13] | Mild temperature: < 100 °C [13] | Lower energy demand for heating directly reduces the carbon footprint. |

| Reaction Time | Long duration: 4–5 hours [13] | Short duration: < 100 minutes [13] | Faster synthesis increases throughput and reduces energy use per unit time. |

| Energy Consumption | High (inferred from temperature/duration) | Significantly Lower [13] | Intensified processes minimize energy-intensive steps, a major operational hotspot. |

| Catalyst Yield | Varies by precursor & process | Comparable or Improved [13] | Ultrasound can enhance reaction efficiency and mass transfer. |

| Biodiesel Yield | Baseline performance | > 90% (achievable with optimized catalysts) [13] | Performance is maintained or enhanced, ensuring green alternative viability. |

Interpretation of Environmental Hotspots

The experimental data in Table 1 allows for a direct comparison of environmental hotspots. In the conventional synthesis route, the calcination step at 600–900 °C is a massive energy hotspot, directly linked to high greenhouse gas emissions if the energy source is fossil-based [13]. The extended reaction time further compounds this energy burden. In contrast, the intensified process dramatically reduces the energy demand by operating at mild temperatures, thereby addressing and mitigating this primary hotspot.

Another critical consideration is the feedstock. Using solid waste (e.g., eggshells, fruit peels, industrial sludge) as a precursor for catalyst production avoids the environmental impacts associated with the extraction, refining, and processing of virgin materials [13]. This shifts the hotspot from the raw material acquisition stage to the synthesis process itself, where the intensified method again proves advantageous. Furthermore, using waste-derived catalysts supports a circular economy and can reduce impacts related to waste disposal [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit for LCA and Green Chemistry

Transitioning from hotspot identification to solution development requires a specific set of tools and reagents. The following table details key research solutions and their functions in developing sustainable chemical processes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Process Development

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Green Process Development |

|---|---|

| Bio-based Feedstocks | Replaces fossil-derived precursors, potentially reducing carbon footprint and non-renewable resource use. Requires LCA to check for trade-offs like land-use change [11]. |

| Biocatalysts (Engineered Enzymes) | Provides high selectivity and efficiency under mild conditions (aqueous solvent, ambient temperature), reducing energy hotspots and hazardous waste generation [31]. |

| Green Solvents (e.g., Water, Ionic Liquids, Bio-based Solvents) | Aims to replace volatile, toxic, and hazardous organic solvents, addressing major toxicity and emission hotspots in reaction and purification steps. |

| Waste-Derived Heterogeneous Catalysts | Serves as a robust, recyclable catalyst synthesized from waste streams (e.g., CaO from eggshells), addressing resource depletion and waste generation hotspots [13]. |

| Ultrasound & Hydrodynamic Cavitation Reactors | Provides process intensification by enhancing mass/heat transfer, enabling faster reactions at lower temperatures, directly targeting energy-intensive hotspots [13]. |

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

While conventional LCA provides a snapshot in time, emerging methodologies are enhancing its accuracy and applicability. Dynamic LCA (DLCA) incorporates time-dependent data, such as historical or forecasted timeseries for background processes (e.g., changing grid electricity carbon intensity), or models the changing state of a system itself [8]. This is particularly relevant for long-lived products or projects with evolving supply chains. In contrast, Real-Time LCA involves the direct, continuous monitoring of environmental impacts in an operational industrial plant [8]. Though still in its infancy and requiring significant digital infrastructure, it holds promise for instantaneous hotspot identification and process optimization in the era of Industry 4.0 [8].

The principles of LCA are also expanding beyond pure environmental impact. The 12 principles for LCA of chemicals, for instance, include "Beyond environment," advocating for the integration of LCA with other tools to assess social and economic impacts, providing a full life cycle sustainability assessment [29]. Furthermore, the combination with other tools is recommended, such as Safety and Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD) frameworks, to comprehensively address all aspects of sustainability from the earliest research phases [29].

The rigorous application of Life Cycle Assessment is indispensable for moving beyond assumptions and achieving genuine sustainability in chemical and pharmaceutical research. By systematically identifying environmental hotspots—from the high energy demand of traditional catalyst synthesis to the resource depletion associated with virgin material use—LCA provides an evidence-based roadmap for innovation. The comparative analysis between conventional and green processes clearly demonstrates that addressing these hotspots through principles of green chemistry, such as process intensification and waste valorization, leads to substantial reductions in environmental impact without compromising performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, embedding LCA into the R&D workflow is no longer an optional add-on but a core component of responsible and forward-thinking scientific practice, enabling the design of products and processes that are truly benign by design.

Conducting an LCA: A Step-by-Step Methodology for Chemical Process Analysis

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a systematic framework for evaluating the environmental impacts of pharmaceutical products from raw material extraction to final disposal. For researchers and scientists in drug development, a properly conducted LCA delivers critical insights that extend beyond traditional green chemistry metrics, enabling evidence-based decisions for sustainable process optimization [32]. The pharmaceutical industry presents unique challenges for LCA implementation, characterized by complex multi-step syntheses of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), high energy and chemical consumption, and specialized waste streams [33]. The first phase of any LCA—defining the goal, scope, and functional unit—serves as the critical foundation that determines the study's overall validity, reliability, and practical usefulness. This phase establishes the rules and boundaries that guide all subsequent data collection and impact assessment, ensuring results are both scientifically sound and decision-relevant for comparing green chemistry innovations against conventional manufacturing processes.

The Goal Definition Phase

Core Components of an LCA Goal

The goal definition provides the strategic compass for the entire LCA study. According to ISO 14040 standards, a robust goal statement must explicitly address several key components that clarify the study's purpose and context [34] [26]. The intended application specifies how the results will be used, whether for internal research and development decisions, public environmental product declarations, or supporting comparative assertions claimed to the public. The reasons for carrying out the study articulate the specific motivations, which may include identifying environmental hotspots in API synthesis, comparing alternative synthetic routes, or providing a baseline for continuous environmental improvement. The target audience determines the appropriate level of technical detail and communication format, which may differ significantly for internal R&D teams, regulatory bodies, or scientific publication. Finally, the goal must state whether the results will be used for public comparative assertions, as this triggers specific critical review requirements under ISO standards [34].

Pharmaceutical-Specific Goal Scenarios

In pharmaceutical contexts, LCA goals often focus on specific development and manufacturing scenarios relevant to drug development professionals. Common applications include comparing conventional and green synthesis routes for specific APIs to quantify environmental trade-offs, assessing the footprint of novel drug modalities like biologics or gene therapies against traditional small molecules, evaluating process intensification strategies such as continuous manufacturing versus batch processing, and supporting regulatory submissions with environmental impact data [33] [32]. For example, a study might aim to "Compare the cradle-to-gate environmental impacts of the traditional synthetic route versus a novel biocatalytic route for Drug X to identify optimization opportunities for reducing carbon footprint and toxicological impacts, with results intended for internal R&D decision-making." Such a clearly defined goal ensures the subsequent scope definition remains focused on delivering actionable insights.

The Scope Definition Phase

Establishing System Boundaries

The scope definition translates the goal into a practical study design by establishing the system boundaries, which determine which unit processes are included in the assessment. Pharmaceutical LCAs typically employ one of several common modeling approaches [34]. Cradle-to-gate assessments include everything from raw material extraction (cradle) through API synthesis and formulation to the factory gate (typically where the finished drug product leaves manufacturing). This boundary is most common for business-to-business applications. Cradle-to-grave assessments include additional phases of distribution, patient use, and disposal/recycling, providing a complete product life cycle perspective. Cradle-to-cradle models incorporate end-of-life material recovery and recycling back into new products, representing a circular economy approach.

For pharmaceutical processes, the system boundary should explicitly address energy generation, raw material acquisition and processing, solvent production and recovery, catalyst synthesis and recycling, packaging materials, transportation between manufacturing sites, waste treatment processes, and direct emissions from manufacturing operations [33]. The specific inclusion or exclusion of these elements depends on the defined goal and data availability constraints common in pharmaceutical applications where supply chain transparency may be limited.

Methodological Choices and Data Quality Requirements

The scope must document critical methodological choices that significantly influence LCA outcomes. Allocation procedures determine how environmental burdens are partitioned when processes yield multiple products, such as in multi-purpose pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities. The impact assessment method selection (e.g., ReCiPe, IPCC, USEtox) determines which environmental impact categories are evaluated, with different methods offering varying relevance to pharmaceutical contexts [32]. The geographical and temporal scope establishes the representative regions and timeframes for data collection, particularly important for electricity grid mixes and transportation distances. Data quality requirements specify age, technological, and geographical representativeness of data, balancing ideal data quality with practical collection constraints common in fast-paced drug development environments [34].

The Functional Unit in Pharmaceutical Contexts

Defining an Appropriate Functional Unit

The functional unit quantifies the performance characteristics of the product system being studied, serving as the reference basis for all input and output flows and enabling fair comparisons between alternatives [34] [26]. In pharmaceutical applications, a functionally representative unit must capture both the quantity and quality of therapeutic benefit, moving beyond simple mass-based metrics. Proper functional unit definition ensures comparability when assessing different synthetic routes or drug formulations. For example, "1 kg of API" fails to account for differences in potency, dosage, or efficacy, while "treatment of one patient for one year achieving 90% disease remission" more accurately represents the clinical function, though it introduces greater complexity in modeling and data requirements.

Common Functional Unit Examples for Pharmaceuticals

Table 1: Functional Unit Examples in Pharmaceutical LCA

| Application Scenario | Recommended Functional Unit | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| API Synthesis Route Comparison | 1 kg of >99.5% pure API meeting pharmacopeia specifications | Must account for purity, crystalline form, and impurity profiles that affect therapeutic suitability |

| Drug Formulation Comparison | 1000 doses of fixed-strength tablet (e.g., 100 mg) | Ensures equivalent therapeutic regimens are compared |

| Therapeutic Area Assessment | Complete treatment course for specific indication (e.g., 14-day antibiotic course) | Captures full environmental impact of complete patient treatment |

| Process Efficiency Analysis | 1 mole of final API product | Enables chemical reaction efficiency comparison independent of molecular weight |

Reference Flow Determination

Closely related to the functional unit, the reference flow quantifies the amount of product needed to fulfill the function [26]. For a functional unit of "1 month of treatment for hypertension with Drug X at standard dosage," the reference flow would specify the exact quantity required, such as "thirty 50-mg tablets of Drug X." This distinction is particularly important when comparing alternative drug delivery systems (e.g., tablets versus injectables) or different synthetic routes yielding the same API with varying purity profiles requiring different dosages for equivalent efficacy.

LCA Workflow and Experimental Protocol

LCA Workflow for Pharmaceutical Processes

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, four-phase LCA workflow adapted for pharmaceutical applications, with emphasis on the goal and scope definition phase:

Experimental Protocol for Goal and Scope Definition

Implementing a robust goal and scope definition requires a structured, documented approach:

Stakeholder Alignment Workshop: Conduct facilitated sessions with key stakeholders (process chemists, environmental specialists, regulatory affairs, business decision-makers) to align on study goals, applications, and audience needs. Document decisions in a goal definition template.

System Boundary Mapping: Create a detailed process flow diagram of the pharmaceutical manufacturing system, identifying all unit operations, material inputs, energy flows, and emission outputs. Clearly demarcate included and excluded processes.

Functional Unit Justification: Based on the product's therapeutic function, define and justify the functional unit with input from clinical and regulatory teams. Document all assumptions regarding dosage, efficacy, and treatment duration.

Data Collection Protocol Development: Create standardized templates for primary data collection from manufacturing operations, including raw material consumption, utility usage, direct emissions, and waste generation. Establish quality control procedures for data validation.

Allocation Procedure Documentation: For multi-product processes, document the selected allocation method (mass, economic, system expansion) with rationale based on the specific context.