Mechanochemistry vs. Traditional Synthesis: A Green Pathway for Sustainable Drug Development and SDG Advancement

This article explores the paradigm shift from traditional solution-based chemistry to mechanochemical processes in pharmaceutical development, evaluating their direct contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Mechanochemistry vs. Traditional Synthesis: A Green Pathway for Sustainable Drug Development and SDG Advancement

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift from traditional solution-based chemistry to mechanochemical processes in pharmaceutical development, evaluating their direct contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It provides a foundational understanding of mechanochemistry as a branch of green chemistry that utilizes mechanical energy to drive reactions, often under solvent-free conditions. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content details methodological applications in API synthesis, cocrystal formation, and polymer degradation, supported by comparative case studies. It addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for scaling these techniques, and presents a rigorous validation through comparative analysis of green metrics, including E-factor, PMI, and RME. The synthesis concludes that mechanochemistry offers a robust, industrially viable approach to reduce the environmental footprint of drug manufacturing, thereby advancing SDG targets for responsible consumption, climate action, and sustainable industrialization.

Green Chemistry and the SDGs: Foundations of Mechanochemistry

The Pharmaceutical Industry's Environmental Imperative and the SDG Framework

The pharmaceutical industry faces a critical environmental challenge, contributing approximately 4.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions—surpassing the automotive sector—while simultaneously bearing responsibility for advancing global public health [1] [2]. This paradox has catalyzed an industry-wide transformation toward sustainable manufacturing practices aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Within this movement, mechanochemistry has emerged as a transformative approach that directly addresses SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) by fundamentally reengineering synthetic processes to minimize environmental impact [3].

Traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing, particularly Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS), relies heavily on hazardous solvents and generates substantial waste, creating an urgent need for greener alternatives [4]. Mechanochemistry, which utilizes mechanical force rather than solvents to drive chemical reactions, presents a viable solution. This comprehensive analysis compares conventional pharmaceutical synthesis with mechanochemical methods, examining environmental metrics, experimental protocols, and alignment with sustainability frameworks to guide researchers and drug development professionals in adopting these innovative techniques.

Comparative Analysis of Traditional vs. Mechanochemical Synthesis

Environmental Performance and Green Metrics

Quantitative comparisons across multiple Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) reveal mechanochemistry's superior environmental profile compared to traditional solution-based synthesis.

Table 1: Green Metrics Comparison Between Traditional and Mechanochemical Synthesis

| Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Mechanochemical Synthesis | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High (typically >100) | Significantly reduced | 2-10x improvement [5] |

| E-factor | High waste generation | Minimal waste generation | Substantial reduction [5] |

| Solvent Consumption | Large volumes (DMF, NMP) | Solvent-free or minimal | >1000-fold reduction for peptide synthesis [4] |

| Atom Economy (AE) | Variable, often suboptimal | Enhanced | Improved [5] |

| Carbon Footprint | High (~5% of European industrial emissions) | Significantly reduced | Major reduction potential [3] |

| Reaction Times | Hours to days | Minutes to hours | 2-5x faster [6] |

Analysis of nine APIs demonstrates that mechanosynthesis more closely adheres to green chemistry principles, including waste prevention, safer chemical use, and energy efficiency [5]. The technology significantly enhances multiple green metrics including Atom Economy (AE), Carbon Efficiency (CE), and Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) while reducing Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and E-factor [5].

Specific Case Study: Peptide Synthesis

Peptide therapeutics represent a growing market segment, with over 110 therapeutic peptides available and increasing demand for GLP-1 receptor agonists [4]. The environmental comparison between SPPS and mechanochemical peptide synthesis reveals dramatic differences:

Table 2: Direct Comparison: SPPS vs. Mechanochemical Peptide Synthesis

| Parameter | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Mechanochemical TSE Process |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Volume | ~0.15 mL/mg resin (80-90% of waste mass) [4] | ~0.15 mL/g amino acid (1000-fold reduction) [4] |

| Amino Acid Ratio | Up to 10-fold excess [4] | Equimolar ratios [4] |

| Key Reagents | DMF/NMP, DIC, Oxyma [4] | Solvent-free or minimal acetone [4] |

| Process Type | Batch (up to 6000L) [4] | Continuous flow [4] |

| Space-Time Yield | Baseline | 30-100 fold increase [4] |

| Solid Support | Polystyrene resin (additional waste) [4] | None required [4] |

The mechanochemical approach utilizing Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE) achieves particularly impressive results, operating under solvent-free to minimal solvent conditions through precise temperature control across extrusion zones [4]. This technology has successfully produced dipeptides and tripeptides at various scales, demonstrating compatibility with common protecting groups and commercial amino acid derivatives [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS)

Principle: Sequential addition of amino acid derivatives to a growing peptide chain anchored to insoluble resin support [4].

Detailed Protocol:

- Resin Swelling: Suspend polystyrene resin in dimethylformamide (DMF) or N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) for 30-60 minutes

- Deprotection: Remove Fmoc protecting group using 20% piperidine in DMF

- Washing: Rinse resin multiple times with DMF (typically 5-10 volumes)

- Coupling: React amino acid (3-10 fold excess) with activating agents (DIC/Oxyma) in DMF for 30-90 minutes

- Repetition: Repeat steps 2-4 for each additional amino acid

- Cleavage: Release peptide from resin using trifluoroacetic acid-based cocktail

- Purification: Reverse-phase HPLC with acetonitrile/water gradients

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent purity and degassing

- Coupling efficiency monitoring (Kaiser test)

- Strict exclusion of moisture

- Temperature control (20-25°C)

Mechanochemical Peptide Synthesis via Twin-Screw Extrusion

Principle: Continuous solvent-free coupling of amino acid derivatives through mechanical shear and compression [4].

Detailed Protocol:

- Premixing: Physically mix equimolar amounts of protected amino acid derivatives (electrophile and nucleophile) with sodium bicarbonate base

- Extrusion Parameters:

- Screw speed: 100-500 rpm

- Temperature profile: Precise control across multiple zones (typically 25-80°C)

- Feed rate: 0.1-5 kg/hour depending on scale

- Residence time: 2-10 minutes

- Reaction Monitoring: In-line Raman spectroscopy or periodic HPLC sampling

- Product Collection: Continuous output of crude peptide for minimal purification

- Sequential Synthesis: For tripeptides, repeat extrusion with subsequent amino acid derivatives

Critical Parameters:

- Screw configuration and kneading elements

- Temperature profile optimization

- Residence time distribution

- Powder flow and feeding consistency

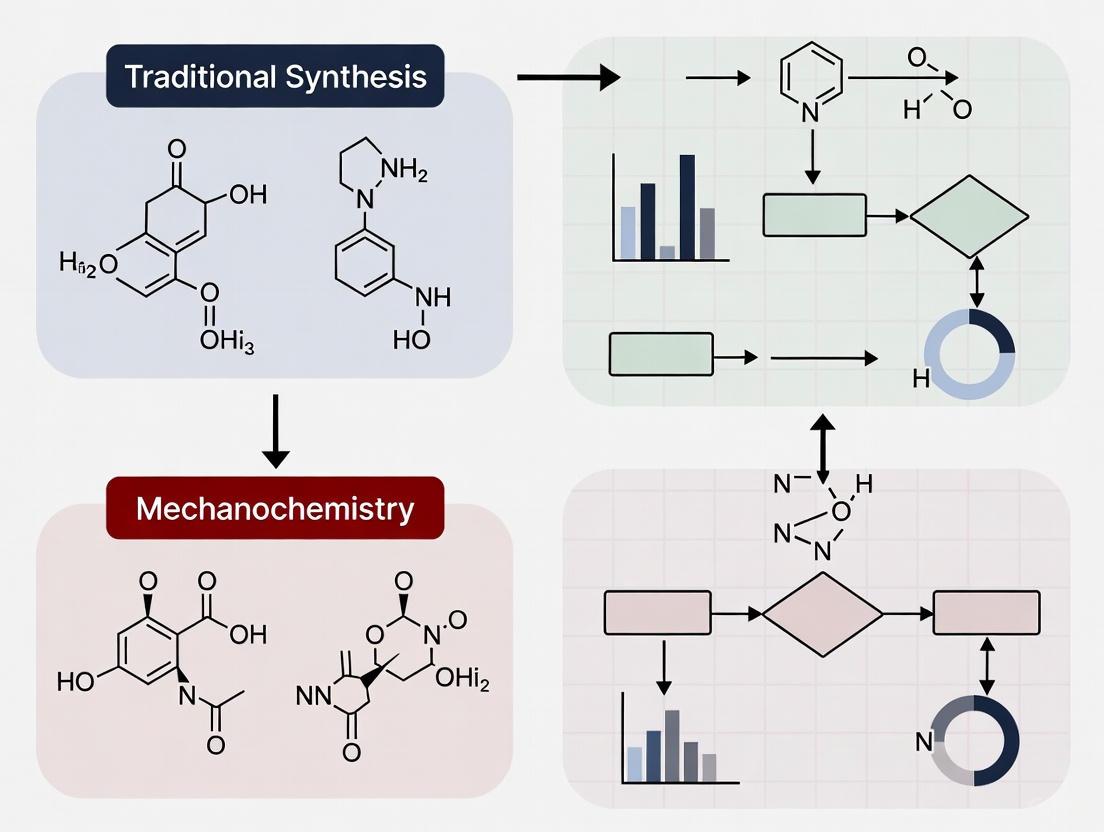

Diagram 1: SPPS vs. Mechanochemical Peptide Synthesis Workflow. The traditional SPPS process involves multiple solvent-intensive steps with recycling loops, while mechanochemical TSE provides a continuous, streamlined approach with minimal purification requirements [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Mechanochemical Peptide Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example in Protocol | Traditional Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid N-Carboxyanhydrides (NCAs) | Electrophile component | Boc-Val-NCA [4] | Fmoc-amino acids |

| Amino Acid N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters | Activated electrophile | Boc-Val-NHS, Boc-Ala-NHS [4] | Same, but used in solution |

| Free Amino Acid Esters (HCl salts) | Nucleophile component | Leu-OMe HCl, Phe-OMe HCl [4] | Resin-bound amino acids |

| Sodium Bicarbonate | Base for HCl salt neutralization | Equimolar to nucleophile [4] | Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) |

| Twin-Screw Extruder | Mechanochemical reactor | Continuous processing [4] | Glass reaction vessels |

| In-line Spectroscopy | Reaction monitoring | Raman for real-time analysis [4] | LC-MS sampling |

Fundamental Principles of Mechanochemical Activation

Understanding the physical principles underlying mechanochemistry is essential for researchers adapting these methods. Mechanical force modifies chemical reactivity through two primary mechanisms:

1. Alteration of Activation Barriers: Mechanical stress directly modifies potential energy surfaces, lowering activation energies through the mechanism described by the Bell-Evans model [7]. The interaction rate under force follows: α(F) = α₀e^(FΔx/kBT), where Δx represents the characteristic spatial scale of the interaction landscape, F is the applied force, and α₀ is the spontaneous rate [7].

2. Enhanced Molecular Collisions: Mechanical processing through methods like TSE increases effective collision probability through intense mixing, particle size reduction, and generation of structural defects and reactive sites [7].

Diagram 2: Mechanical Force Lowers Activation Energy. Applied force distorts the potential energy landscape, reducing the activation barrier between reactants and products and enabling reactions under milder conditions [7].

Regulatory Framework and Global Sustainability Initiatives

The pharmaceutical industry operates within an increasingly stringent regulatory environment focused on environmental impact. Key developments include:

WHO Greener Pharmaceuticals Initiative: The World Health Organization has issued a call for action to drive sustainability in the pharmaceutical sector, emphasizing that "addressing the environmental impact of healthcare products is no longer optional - it is imperative" [8]. The initiative promotes:

- Sustainable manufacturing, packaging, and distribution standards

- Digital transformation of regulatory processes

- Earlier regulator-manufacturer collaboration on eco-friendly innovations [8]

Pharmaceutical Sector Nature-Positive Roadmap: Developed by WBCSD in collaboration with major pharmaceutical companies, this framework aims to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030 through:

- Assessing nature-related impacts across value chains

- Implementing targeted nature-positive actions

- Developing harmonized metrics for accountability [9]

EU Pharmaceutical Regulations: Updated regulations now mandate environmental risk assessments for new medicines, reflecting growing regulatory pressure [1].

The comparative analysis between traditional and mechanochemical synthesis methods reveals a clear trajectory for the pharmaceutical industry's sustainable transformation. Mechanochemistry demonstrates superior environmental performance across multiple metrics, including dramatic solvent reduction, waste minimization, and enhanced energy efficiency [4] [5]. The technology aligns strategically with SDG frameworks and evolving regulatory expectations while maintaining synthetic efficiency and scalability.

For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting mechanochemical approaches represents both an environmental imperative and a strategic opportunity. The experimental protocols and reagent solutions detailed in this guide provide practical pathways for implementation. As the WHO emphasizes, regulatory expectations increasingly favor sustainable manufacturing, making early adoption of these technologies advantageous for both environmental and business objectives [8] [2].

The pharmaceutical industry's transition toward greener synthesis methods, particularly mechanochemistry, will play a crucial role in achieving global sustainability targets while continuing to advance human health through innovative therapeutics.

Mechanochemistry represents a transformative approach to chemical synthesis, defined as the initiation of chemical reactions by mechanical phenomena rather than thermal energy, light, or electricity. This review objectively compares traditional solution-based chemistry with mechanochemical processes through the lens of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly focusing on pharmaceutical applications. Experimental data demonstrate that mechanochemistry consistently outperforms traditional methods across key green metrics, including substantial reductions in E-factor (a measure of process waste), improved reaction efficiencies, and elimination of hazardous solvents. The historical development of mechanochemistry reveals a field that has evolved from ancient mechanical processing to a sophisticated discipline enabling sustainable drug development and materials synthesis with profound implications for environmental stewardship and green technology innovation.

Historical Development

The history of mechanochemistry spans millennia, bridging ancient material processing with modern sustainable synthesis technologies. This evolution can be divided into distinct historical periods that reflect the field's growing sophistication and application breadth.

Ancient and Prehistoric Origins

The earliest mechanochemical experiences date to prehistoric times through activities like fine grinding of materials [10]. A primal mechanochemical project involved making fire by rubbing pieces of wood together, creating friction and heat to trigger combustion [11]. The first documented systematic investigations emerged in the 4th century BC, with Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, conducting mineral experiments [12]. A notable early process involved the extraction of mercury by mechanochemical reduction of cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) by grinding in a copper vessel with vinegar [13].

Foundational 19th Century Research

The late 19th century marked the beginning of systematic scientific investigation into mechanochemistry, primarily through two pioneering figures:

Walthère Spring (University of Liège) studied the consolidation and reactions of powdered materials under high pressure to understand mineral formation in the Earth's crust [10]. His work demonstrated that pressure could induce chemical reactions between solid substances, such as the formation of arsenides and sulfides [10].

M. Carey Lea is recognized as "the first mechanochemist" for his extensive experiments on mechanical decomposition of compounds through grinding [10]. Lea made the crucial observation that mechanical action could produce distinctly different results from thermal effects, documenting endothermic reactions triggered by mechanical force and the transformation of mechanical energy into chemical energy [10].

Modern Institutionalization

The 1960s represented a pivotal period for mechanochemistry with the formation of a broader scientific community. The first dedicated conference was organized in 1968 as a special session of the Soviet colloid chemists' meeting, largely driven by P.A. Rebinder and P.A. Thiessen [10]. This established mechanochemistry as a distinct scientific discipline with regular conferences and growing research output, particularly in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe [10].

Contemporary Renaissance

Since the 1990s, mechanochemistry has experienced a renaissance with applications expanding to:

- Organic synthesis and supramolecular chemistry [13]

- Pharmaceutical production with enhanced green metrics [14]

- Advanced materials including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and nanomaterials [13] [3]

- Polymer science with mechanophores for stress-sensing materials [15] [11]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry has recognized mechanochemistry as one of ten chemical innovations that will change the world, cementing its importance in sustainable chemistry [13].

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

Core Concepts

Mechanochemistry represents a fundamental paradigm in chemical synthesis, operating on principles distinct from traditional approaches:

Primary Definition: "The initiation of chemical reactions by mechanical phenomena" or more specifically, "chemical synthesis induced by external mechanical energy" [13] [11]. This establishes mechanochemistry as the fourth approach to driving chemical reactions, complementing thermal activation, photochemistry, and electrochemistry [11].

Force-Induced Reactivity: Mechanical force can dramatically alter chemical kinetics, with documented cases where mechanical stretching reduces bond half-lives from astronomical timescales to microseconds at room temperature [13]. This occurs through selective deformation of molecular structures in ways not achievable through thermal or photochemical means.

Mechanophore Concept: A key advancement is the development of "mechanophores" - molecular units engineered to undergo predictable chemical transformations in response to applied stress [15] [11]. These enable materials with functions including damage sensing, self-healing, and stress-reporting capabilities [15].

Comparative Framework: Traditional vs. Mechanochemical Synthesis

The fundamental differences between traditional and mechanochemical approaches can be understood through their distinct operational paradigms:

Table: Fundamental Principles Comparison

| Parameter | Traditional Solution Chemistry | Mechanochemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Input | Thermal energy (heating) | Mechanical force (grinding, milling) |

| Reaction Medium | Liquid solvents (often organic) | Solid-state (minimal or no solvent) |

| Molecular Mobility | Diffusion in liquid phase | Direct solid-solid contact |

| Reaction Environment | Homogeneous solution | Heterogeneous solid interfaces |

| Primary Mechanism | Solvent-facilitated molecular collision | Mechanical force-induced bond deformation |

Experimental Comparison: Pharmaceutical Applications

Green Metrics Analysis

Comprehensive analysis of nine Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) reveals significant environmental advantages for mechanochemical processes compared to traditional synthesis routes [14] [5]. The quantitative comparison demonstrates superior performance across multiple green chemistry metrics:

Table: Green Metrics Comparison for API Production

| Performance Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Mechanochemistry | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-factor (kg waste/kg product) | High (often 25-100) | Significantly reduced | 5-10x reduction |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High | Dramatically lower | Substantial improvement |

| Atom Economy (AE) | Variable, often suboptimal | Enhanced | Notable increase |

| Carbon Efficiency (CE) | Limited | Improved | Significant enhancement |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) | Moderate | Higher | Marked improvement |

| cE-factor | Elevated | Reduced | Considerable reduction |

| Solvent Consumption | Substantial (primary waste source) | Minimal to zero | Near elimination |

| Energy Efficiency | Moderate (heating/cooling requirements) | High (direct energy input) | Significant improvement |

| Reaction Time | Hours to days | Minutes to hours | Substantial reduction |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Solution-Based Synthesis

- Apparatus: Round-bottom flasks, reflux condensers, separation funnels, heating mantles [12]

- Procedure: Reactants dissolved in appropriate solvents (frequently dichloromethane, DMF, THF, or other organic solvents) with continuous stirring [14] [12]

- Reaction Conditions: Typically requires heating to reflux temperatures (often 60-120°C) for extended periods (hours to days) [14]

- Workup Steps: Multiple extraction, washing, and purification steps including column chromatography, recrystallization, and distillation [14]

- Solvent Consumption: Large volumes relative to product mass (often 50-100 mL/g product) [14] [12]

Mechanochemical Synthesis

- Apparatus: Ball mills (planetary or shaker types), mixer mills, or mortar and pestle for small-scale experiments [13] [11]

- Grinding Media: Stainless steel, tungsten carbide, or ceramic balls of varying diameters (typically 2-15 mm) [13]

- Procedure: Solid reactants placed in milling jar with grinding balls, processed for predetermined time (minutes to hours) [14] [13]

- Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG): Minimal solvent addition (catalytic amounts) to enhance molecular mobility without creating solutions [13]

- Reaction Conditions: Room temperature typically, with controlled frequency and energy input through milling speed [14]

- Workup Steps: Minimal purification often required, simple washing or direct collection of product [14]

Process Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of mechanochemical processes requires specific equipment and materials optimized for solid-state reactions:

Table: Essential Materials for Mechanochemical Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | High-energy impact grinding | Adjustable rotation speed, multiple jar materials available [13] |

| Mixer Mill | Horizontal shaking motion | Effective for small-scale screening [13] |

| Stainless Steel Balls | Grinding media | Various diameters (2-15mm) for different impact energies [13] |

| Tungsten Carbide Jars | Milling containers | High density for efficient energy transfer [13] |

| Ceramic Balls/Jars | Inert grinding media | For metal-sensitive reactions [13] |

| Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) Additives | Catalytic solvent amounts | Typically 1-5 drops to enhance mobility [13] |

| Mechanophores | Force-responsive molecular units | Spiropyran, gem-dichlorocyclopropane for stress-sensing [15] [11] |

| Analytical Techniques | Real-time reaction monitoring | In-situ Raman, PXRD for mechanistic studies [13] |

Sustainable Development Goal Applications

Pharmaceutical Industry Alignment with SDGs

Mechanochemistry directly addresses multiple Sustainable Development Goals through transformative applications in pharmaceutical manufacturing and materials science:

SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): Production of APIs with reduced environmental impact and elimination of hazardous solvent residues in pharmaceutical products [14] [3]

SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure): Enables cleaner production technologies with reduced energy consumption and waste generation [3]

SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production): Dramatic reduction in Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and E-factor through solvent-free synthesis [14] [3]

SDG 13 (Climate Action): Significant lowering of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions by eliminating solvent production and incineration [14] [3]

Advanced Materials for Sustainability

Mechanochemistry enables synthesis of materials critical for sustainable technologies:

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Porous materials for carbon capture, water treatment, and energy storage synthesized without solvents [13] [3]

Biomass Valorization: Conversion of wood waste and other biomass into valuable chemicals through mechanocatalysis [3]

Energy Storage Materials: Solid-state synthesis of battery components and hydrogen storage materials with improved efficiency [11]

Recyclable Polymers: Incorporation of mechanophores for mechanically-triggered depolymerization to enhance plastic recyclability [15]

The comprehensive comparison between traditional and mechanochemical processes demonstrates that mechanochemistry represents a paradigm shift in sustainable chemical synthesis. With its historical roots in ancient processing techniques and 19th century scientific investigation, mechanochemistry has evolved into a sophisticated discipline offering substantial environmental advantages across pharmaceutical production and materials science. Experimental data confirm superior performance in green metrics, including dramatic reductions in waste generation, elimination of hazardous solvents, and improved energy efficiency. The alignment of mechanochemistry with multiple Sustainable Development Goals, particularly through applications in pharmaceutical manufacturing, water treatment, and renewable energy materials, positions this field as a cornerstone of sustainable industrial development. While challenges remain in fundamental mechanistic understanding and technology transfer, the continued advancement of mechanochemical processes promises to significantly contribute to greener, more sustainable chemical industries worldwide.

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry as an Evaluation Framework

The global chemical industry, particularly the pharmaceutical sector, faces increasing pressure to minimize its environmental footprint. Drug manufacturing is known for producing 25 to over 100 kg of waste per kilogram of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), largely due to multi-step processes, stoichiometric reagents, and substantial solvent use [16]. In response, green chemistry principles provide a systematic framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [17].

This review employs the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry as an evaluation framework to objectively compare traditional solution-based chemistry with mechanochemical approaches. Mechanochemistry, defined as a "chemical reaction induced by the direct absorption of mechanical energy," offers a promising sustainable alternative through techniques like ball milling and extrusion [16] [18]. The analysis specifically examines how these methodologies advance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3), Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9), Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12), and Climate Action (SDG 13) [16] [19].

The Analytical Framework: Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Paul Anastas and John Warner, provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the environmental performance of chemical processes [17] [20]. These principles emphasize pollution prevention at the molecular level rather than end-of-pipe treatment, atom economy to maximize resource efficiency, and designing safer chemicals and processes [17]. For researchers and industrial chemists, these principles serve as actionable guidelines for developing cost-effective and eco-friendly processes.

When applied to pharmaceutical production and API synthesis, this framework enables systematic evaluation of traditional and emerging technologies. The principles directly support corporate sustainability goals and regulatory compliance while driving innovation in synthetic methodology [21]. As the chemical industry moves toward a low-carbon economy, this framework provides metrics to quantify improvements in waste reduction, energy efficiency, and hazard minimization [19].

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry as an Evaluation Framework [17] [20]

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Concept | Key Evaluation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevent Waste | Design syntheses to prevent waste generation rather than treating or cleaning up waste afterward | E-factor, PMI |

| 2 | Maximize Atom Economy | Design syntheses so final product contains maximum proportion of starting materials | Atom Economy (AE) |

| 3 | Design Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Use and generate substances with minimal toxicity to humans and environment | Hazard assessment, toxicity metrics |

| 4 | Design Safer Chemicals | Design effective products with minimal toxicity | Efficacy-toxicity ratio |

| 5 | Use Safer Solvents & Reaction Conditions | Avoid auxiliary chemicals; use safer alternatives when necessary | Solvent greenness scores, energy input |

| 6 | Increase Energy Efficiency | Run reactions at ambient temperature and pressure when possible | Energy consumption, temperature requirements |

| 7 | Use Renewable Feedstocks | Use starting materials from renewable resources rather than depletable sources | Renewable feedstock percentage |

| 8 | Avoid Chemical Derivatives | Avoid unnecessary blocking/protecting groups | Number of synthetic steps, step economy |

| 9 | Use Catalysts, Not Stoichiometric Reagents | Use catalytic reactions that minimize waste | Catalyst loading, turnover number/frequency |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design chemical products to break down to innocuous substances after use | Degradability, persistence metrics |

| 11 | Analyze in Real Time for Pollution Prevention | Include in-process monitoring to minimize byproduct formation | Process analytical technology (PAT) implementation |

| 12 | Minimize Accident Potential | Design chemicals and forms to minimize potential for accidents | Physical hazard assessment (explosivity, flammability) |

Methodology for Comparative Analysis

Evaluation Metrics and Data Collection

The comparative assessment between traditional and mechanochemical processes employs quantitative green metrics to provide objective, data-driven evaluations. These metrics include [16] [22]:

- Atom Economy (AE): Molecular weight of desired product divided by sum of molecular weights of all reactants

- Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME): (Mass of product / Total mass of reactants) × 100%

- Environmental Factor (E-factor): Total mass of waste (kg) per mass of product (kg)

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): Total mass of materials (kg) used per mass of product (kg)

- Complete E-factor (cE-factor): E-factor including water in calculations

Data were collected from peer-reviewed literature comparing identical or highly similar chemical transformations conducted under both traditional solution-based and mechanochemical conditions. The analysis focused particularly on API synthesis pathways common in pharmaceutical development [16].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanochemical Synthesis

Ball Milling Methodology [16] [18]:

- Equipment Setup: Reactions conducted using planetary ball mills (e.g., Retsch PM100) with grinding jars (stainless steel, zirconium oxide, or Teflon) and grinding balls of varying diameters (typically 5-15 mm)

- Loading Procedure: Reactants and any catalysts loaded into grinding jar in predetermined stoichiometric ratios without or with minimal solvent (Liquid-Assisted Grinding, LAG)

- Reaction Parameters: Milling frequency set (typically 500-800 rpm) with alternating rotation directions to enhance mixing

- Temperature Control: Reactions conducted at ambient temperature unless specified, with monitoring of potential "hot-spots" from friction

- Work-up Procedure: Product decanted directly from milling jar, often requiring no further purification or simple washings

Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE) for Continuous Processing [18]:

- System Configuration: Powdered reactants fed into extruder hopper; catalysts optionally premixed or injected through secondary ports

- Process Parameters: Screw rotation speed, temperature zones, and residence time optimized for specific reaction

- Product Collection: Material collected continuously at die outlet, optionally ground to uniform particle size

Comparative Evaluation: Traditional vs. Mechanochemical Processes

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Green Metrics Comparison for Selected API Syntheses [16] [22]

| API/Reaction | Synthesis Method | Atom Economy (%) | E-factor (kg waste/kg product) | Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Reaction Mass Efficiency (%) | Reaction Time | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teriflunomide | Traditional Solution | 82 | 48 | 52 | 65 | 12+ hours | 85 |

| Teriflunomide | Mechanochemical (Ball Milling) | 82 | 12 | 15 | 78 | 5 hours | 88 |

| Amide Bond Formation | Traditional Solution | 85 | 32 | 41 | 61 | 8 hours | 82 |

| Amide Bond Formation | Mechanochemical | 85 | 8 | 11 | 86 | 2 hours | 90 |

| Carbamate Synthesis | Traditional Solution | 79 | 41 | 53 | 58 | 10 hours | 80 |

| Carbamate Synthesis | Mechanochemical | 79 | 11 | 14 | 83 | 3 hours | 87 |

| Heterocycle Formation | Traditional Solution | 75 | 56 | 68 | 52 | 15 hours | 75 |

| Heterocycle Formation | Mechanochemical | 75 | 15 | 19 | 79 | 4 hours | 89 |

Principle-by-Principle Analysis

Principles 1-3 (Waste Prevention, Atom Economy, Less Hazardous Syntheses): Mechanochemistry demonstrates superior performance with E-factors 60-80% lower than traditional processes [16]. This improvement stems primarily from solvent elimination and precise stoichiometric control that minimizes excess reagents. While atom economy remains identical for identical reaction pathways, mechanochemistry's ability to enable novel, more direct synthetic routes can substantially improve inherent atom economy [22].

Principles 5-6 (Safer Solvents, Energy Efficiency): Mechanochemical processes address the critical solvent issue in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where solvents constitute 80-90% of the mass in traditional processes [16]. By operating without solvents or with minimal solvent in LAG approaches, mechanochemistry eliminates volatile organic compound emissions and reduces hazards. Energy efficiency is enhanced by conducting reactions at ambient temperature without energy-intensive cooling or heating [18].

Principles 8-9 (Avoid Derivatives, Catalytic Reactions): The ability to conduct reactions under solvent-free conditions enables mechanochemistry to avoid protecting groups in certain transformations. Additionally, mechanochemical activation enhances catalyst efficiency, allowing reduced catalyst loading while maintaining or improving activity [22] [18].

Case Study: Teriflunomide Synthesis

Experimental Protocols

Traditional Synthesis Protocol [16]:

- Reaction Setup: Charge acetonitrile (5 L/kg substrate) into reactor

- Amide Coupling: Add 5-methyl isoxazole-4-carbonyl chloride (1.0 equiv) and 4-(trifluoromethyl)aniline hydrochloride (1.2 equiv)

- Reaction Monitoring: Stir at 25°C for 8 hours monitoring by TLC/HPLC

- Intermediate Isolation: Concentrate, wash with aqueous NaHCO₃, dry over MgSO₄, filter, and concentrate to obtain leflunomide intermediate

- Hydrolysis: Dissolve intermediate in methanol, add aqueous NaOH (1.5 equiv), stir 4 hours at 40°C

- Work-up: Acidify with HCl, filter precipitate, wash with water, and dry under vacuum

- Overall Yield: 85% over two steps; E-factor: 48

Mechanochemical Synthesis Protocol [16]:

- Equipment Preparation: Load stainless-steel grinding jar (50 mL) with fifty stainless-steel balls (5 mm diameter)

- Activation Step: Add carboxylic acid (1.0 equiv) and carbonyldiimidazole (CDI, 1.1 equiv), mill at 500 rpm for 20 minutes

- Amide Coupling: Add amine hydrochloride (1.05 equiv), mill at 500 rpm for 5 hours with 1-minute breaks every 10 minutes and rotation direction inversion

- Product Isolation: Decant product from jar, minimal washing with cold water

- Overall Yield: 88% in one pot; E-factor: 12

Comparative Green Metrics Analysis

The teriflunomide case study demonstrates mechanochemistry's substantial advantages across multiple green chemistry principles. The E-factor reduction from 48 to 12 (75% decrease) primarily results from solvent elimination and reduced reagent excess [16]. The single-pot mechanochemical approach eliminates the need for intermediate isolation and purification, reducing PMI from 52 to 15. While atom economy remains identical for the core bond-forming steps, the overall process efficiency improves significantly through simplified workflow and reduced auxiliary materials [22].

Visualization of the Evaluation Workflow

Diagram 1: Green Chemistry Principles Evaluation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the systematic framework for evaluating chemical processes against the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, leading to quantitative metrics assessment and SDG alignment evaluation.

Mechanochemical Equipment and Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Equipment and Reagents for Mechanochemical Research

| Equipment/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | Provides mechanical energy through impact and friction | Variable speed control, multiple jar materials available | Retsch PM100, Fritsch Pulverisette |

| Mixer Mill | High-energy grinding for small samples | Suitable for screening reaction conditions | Retsch MM 400, SPEX SamplePrep 8000M |

| Twin-Screw Extruder | Continuous mechanochemical processing | Enables scalable production, various screw configurations | Thermo Scientific Process 11, Leistritz Nano16 |

| Zirconium Oxide Jars & Balls | Milling media for metal-sensitive reactions | Prevents API contamination, EMA-compliant | Zirconia grinding jars (10-250 mL capacity) |

| Stainless Steel Media | Standard milling media for most reactions | Cost-effective, durable | Balls (3-15 mm diameter), cylinders |

| Teflon Milling Assemblies | For highly corrosive or reactive systems | Chemically inert, minimal contamination | Custom-fabricated assemblies |

| Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) Additives | Minimal solvent to enhance reaction kinetics | Typically 1-100 μL/mg substrate | Water, ethanol, ethyl acetate, ionic liquids |

| Catalytic Reagents | Enable catalytic mechanochemical reactions | Enhanced efficiency under milling conditions | Organocatalysts, metal catalysts, enzymes |

Diagram 2: Mechanochemistry Research Infrastructure. This diagram outlines the essential equipment, media, and process parameters for mechanochemical research and their applications in sustainable chemistry.

SDG Alignment and Sustainability Impact

The adoption of mechanochemical processes directly advances multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. For the pharmaceutical industry, which must balance SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) with environmental responsibility, mechanochemistry offers a pathway to reduce the environmental burden of drug manufacturing [16] [19].

SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) is supported through the development of innovative mechanochemical technologies that retrofit existing production facilities for sustainability. The significant reductions in Process Mass Intensity and E-factor demonstrated in Table 2 directly contribute to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by minimizing resource use and waste generation across the chemical lifecycle [16].

The carbon emission reduction potential of mechanochemistry aligns with SDG 13 (Climate Action) through decreased energy consumption for solvent manufacturing, distribution, and removal, as well as reduced fossil fuel dependence for petrochemical-derived solvents [16] [19]. The technology's ability to operate at ambient temperature without external heating or cooling substantially lowers the carbon footprint of chemical manufacturing.

The systematic evaluation using the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry establishes mechanochemistry as a superior approach for sustainable chemical synthesis, particularly in pharmaceutical applications. The quantitative comparison reveals substantial improvements in waste reduction (60-80% lower E-factors), energy efficiency, and hazard minimization compared to traditional solution-based methods.

While mechanochemistry demonstrates stronger alignment with green chemistry principles overall, challenges remain in continuous processing, heat management for exothermic reactions, and equipment scalability. Emerging technologies like twin-screw extrusion and advanced reactor designs show promise in addressing these limitations [16] [18].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mechanochemistry represents a paradigm shift toward sustainable synthesis that aligns with both green chemistry principles and broader sustainable development goals. The technology's ability to enable novel reaction pathways, improve efficiency, and reduce environmental impact positions it as a cornerstone of sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing in the coming decades.

The chemical industry, particularly the pharmaceutical sector, faces increasing pressure to align its practices with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Traditional solution-based chemical synthesis, the long-standing industry standard, is often characterized by high energy consumption and substantial waste generation, creating tension with global sustainability targets [16]. Within this context, mechanochemistry—the use of mechanical force to drive chemical reactions—has re-emerged as a transformative technology capable of directly supporting several SDGs.

This guide provides an objective comparison between traditional and mechanochemical processes, focusing on their contributions to SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). By synthesizing current research data and experimental findings, we offer researchers and drug development professionals a clear, evidence-based framework for evaluating these methodologies.

Quantitative Comparison of Traditional vs. Mechanochemical Processes

The environmental and economic superiority of mechanochemistry can be quantitatively demonstrated using standardized green metrics. The following tables summarize comparative data for the synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and other chemicals.

Table 1: Comparison of Green Metrics for API and Chemical Synthesis

| Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Mechanochemical Synthesis | Improvement Factor | Relevant SDG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-factor (kg waste/kg product) | 25 to >100 [16] | Significantly lower [16] [23] | >70% reduction in some cases [23] | SDG 12 |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High (Solvents ≈ 80-90% of mass) [16] | Drastically reduced [22] | N/A | SDG 12 |

| Energy Consumption | High (Thermal energy input) | 2-10 times less [24] | 2-10X | SDG 13 |

| Reaction Time | Several hours [24] | 30-90 minutes [24] | 2-5X faster [24] | SDG 9 |

| Operating Cost | Baseline | 30-50% lower [24] | 30-50% reduction [24] | SDG 9 |

| Solvent Use | ~85% of process mass [24] | Solvent-free or minimal [16] [25] | Near-total elimination [24] | SDG 12, 13 |

Table 2: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Results for Nitrofurantoin Synthesis [23]

| Impact Category | Traditional Batch Synthesis | Mechanochemical TSE | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Baseline | Significantly lower | Significant reduction in CO2-eq |

| Human Health Impacts | Baseline | Significantly lower | Improved outcomes |

| Ecological Health | Baseline | Significantly lower | Improved outcomes |

| Cumulative Energy Demand | Baseline | Lower | More efficient |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Mechanochemical Synthesis of an API via Ball Milling

The following methodology, derived from the synthesis of Teriflunomide, is representative of a ball-milling approach [16].

- Equipment: Retsch PM100 Planetary Mill (or equivalent); Stainless steel, zirconium oxide, or Teflon grinding jar and balls (to avoid metal contamination per EMA regulations) [16].

- Reagent Preparation: Weigh solid carboxylic acid and amine hydrochloride reagents precisely. Control over stoichiometry is a key advantage, often eliminating the need for excess reagents [22].

- Reaction Step:

- Place reagents and milling balls into the grinding jar.

- For multi-step one-pot syntheses, the first step may involve activating a reagent (e.g., carboxylic acid activation with CDI). This is performed by milling at a specified speed (e.g., 500 rpm) for a set time (e.g., 20 minutes) [16].

- Add subsequent reagents (e.g., amine hydrochloride) to the same jar.

- Mill the reaction mixture for the required time (e.g., 5 hours at 500 rpm). Programs often include intermittent breaks and rotation reversal to manage heat and improve mixing [16].

- Work-up and Purification: The solid product is typically extracted from the jar. Due to higher selectivity and fewer by-products, purification is often simplified and may only require a wash or recrystallization, avoiding complex and solvent-intensive column chromatography [24] [22].

Protocol 2: Continuous Synthesis via Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE)

Twin-screw extrusion represents a scalable, continuous mechanochemical process suitable for industrial application [16] [23].

- Equipment: Co-rotating twin-screw extruder.

- Reagent Preparation: Solid reagents and any liquid additives are precisely fed into the extruder via powder feeders and liquid pumps, respectively.

- Reaction Step:

- The solid reagents are conveyed into the extruder barrel by the rotating screws.

- The chemical reaction occurs through intense mixing and shearing forces in the barrel. The screw configuration (kneading blocks, conveying elements) can be customized to optimize reaction efficiency.

- The reaction is completed as the mixture moves through the barrel, which may be divided into zones with independent temperature control.

- Product Collection: The final product is continuously extruded as a solid strand, which can be collected and processed further (e.g., milled to a powder). This continuous operation eliminates batch-to-batch variability and enables high-throughput production [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Equipment

Table 3: Key Equipment and Reagents for Mechanochemical Research

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | High-energy mill using centrifugal forces for grinding and mixing. | Lab-scale screening of mechanochemical reactions for API synthesis [16]. |

| Twin-Screw Extruder (TSE) | Continuous processor using intermeshing screws to mix, shear, and convey materials. | Scalable, continuous synthesis of APIs and materials; direct translation to industrial processing [16] [23]. |

| Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) Additives | Catalytic amounts of liquids (e.g., solvents, ionic liquids) added to the solid reaction. | Modifying reaction kinetics and selectivity; stabilizing intermediates without acting as bulk solvents [24]. |

| Zirconium Oxide Milling Jars/Balls | Dense, inert milling media. | Preventing metal contamination in API synthesis, crucial for regulatory compliance [16]. |

| In-situ Analytical Probes | Raman, X-ray diffraction, or other probes integrated into the milling chamber. | Real-time monitoring of reaction kinetics and mechanistic studies [26]. |

Logical Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway for implementing mechanochemistry and its subsequent contribution to the relevant Sustainable Development Goals.

Pathway to SDGs via Mechanochemistry

The diagram above maps the logical connection between process choices and their alignment with the SDGs. The mechanochemistry pathway directly enables sustainable production (SDG 12) and climate action (SDG 13) through drastic waste and emission reductions. Furthermore, its innovative and scalable nature, exemplified by technologies like twin-screw extrusion, fosters resilient infrastructure and sustainable industrialization (SDG 9).

The empirical data and experimental comparisons presented in this guide consistently demonstrate that mechanochemistry offers a substantively more sustainable pathway than traditional solution-based methods. The technology directly addresses critical industrial challenges by drastically reducing solvent-related waste (aligning with SDG 12), lowering energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions (supporting SDG 13), and enabling innovative, cost-effective, and continuous manufacturing processes (advancing SDG 9). For researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, the adoption and further development of mechanochemical techniques is not merely a technical optimization but a strategic imperative for aligning drug development with global sustainability targets.

Mechanochemistry in Practice: Techniques and Pharmaceutical Applications

The pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the pharmaceutical industry has catalyzed a shift towards greener manufacturing technologies. Among the most promising advancements are mechanochemical methods, which utilize mechanical force to drive chemical reactions, significantly reducing or eliminating the need for hazardous solvents. This guide provides an objective comparison of three core technologies—ball milling, twin-screw extrusion (TSE), and continuous-flow systems—evaluating their performance, applications, and suitability for sustainable drug development. As the industry moves away from traditional, solvent-intensive batch processes, these technologies offer pathways to minimize waste, improve energy efficiency, and enable safer synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and intermediates [5] [27]. Ball milling represents the foundational batch-mode mechanochemical approach, while twin-screw extrusion and other continuous-flow systems have emerged as scalable, continuous alternatives capable of kilogram-per-hour throughputs, transforming laboratory innovations into viable industrial processes [4] [28].

Technology Comparison: Operational Principles and Characteristics

The following table summarizes the core attributes, advantages, and limitations of each technology, providing a foundational comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Core Equipment Technologies

| Technology | Operational Principle | Reaction Mode | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball Milling | Impact and shear forces from grinding balls inside a vibrating or rotating jar [27] | Batch | Solvent-free or minimal solvent (LAG) [29]; Enables novel reaction pathways [29]; Simple operation for lab-scale synthesis | Limited scalability due to safety and heat dissipation constraints [28]; Batch processing; Precise temperature control can be challenging [30] |

| Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE) | Shearing and kneading actions between two intermeshing, rotating screws inside a barrel [4] [28] | Continuous | Excellent scalability and kilogram-per-hour throughput [4] [28]; Precise control over temperature profile and shear forces [4]; Superior mixing for solids and viscous pastes [4] | Higher equipment cost and complexity [28]; Requires optimization of many parameters (screw design, speed, temperature zones) [28] |

| Continuous-Flow (Liquid) Systems | Pumping liquid reaction streams through tubular reactors [28] | Continuous | Excellent heat and mass transfer for homogeneous reactions [28]; Safe handling of hazardous reagents/intermediates [28]; Easy integration with in-line analysis | Requires soluble reagents; Clogging can occur with solids [28]; Still relies on bulk solvent, impacting PMI and E-factor [28] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct quantitative comparisons provide crucial data for technology selection. The following table synthesizes performance metrics from recent research, highlighting the significant environmental and efficiency gains of mechanochemistry over traditional methods, and the superior scalability of TSE.

Table 2: Synthesis of Quantitative Performance Metrics from Literature

| Technology vs. Application | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Traditional Method & Performance Data |

|---|---|---|

| Ball MillingGeneral Organic Synthesis [5] [27] | • Solvent Use: Solvent-free or highly minimized (LAG).• Reaction Time: Often drastically reduced.• Yield & Purity: Frequently higher or comparable yields. | Solution-based synthesis: Higher E-factor and Process Mass Intensity (PMI) due to solvent use [5]. |

| Ball MillingCyclodextrin Derivatization [29] | • Energy Efficiency: Avoids energy-intensive solvent removal steps.• Reaction Mechanism: Can yield different substitution patterns/products vs. solution chemistry. | Conventional synthesis: Energy-intensive for water removal to obtain solid product; follows classical solution mechanism [29]. |

| Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE)Peptide Synthesis [4] | • Solvent Use: ~0.15 mL/g (acetone to amino acid).• Space Time Yield: 30-100x higher than solution phase for dipeptides.• Amino Acid Stoichiometry: Equimolar ratio. | Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): ~0.15 mL/mg solvent to resin (≥1000x more solvent); stoichiometric excess of amino acids [4]. |

| Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE)Imine Synthesis [31] | • Throughput: 6.74 kg/day demonstrated.• Space-Time Yield: 1716 kg m⁻³ day⁻¹.• Yield: Near-quantitative (>99%). | Batch (Neat, 80°C): 54% yield after 30 minutes [31]. |

| Reactive Extruder-GrinderChromene Synthesis [30] | • Reaction Time: 2-10 minutes.• Yield: 75-98%.• Conditions: Catalyst-free, solvent-free, ambient temperature. | Classical Methods: Require catalysts, solvents, and/or longer reaction times [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Mechanochemical Peptide Synthesis via Twin-Screw Extrusion

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating a green, continuous alternative to Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) for dipeptide and tripeptide synthesis [4].

- Objective: To synthesize a model dipeptide (e.g., Boc-Val-Leu-OMe) continuously and with minimal solvent.

- Materials:

- Amino Acid Derivatives: Electrophile: e.g., Boc-Val-NCA (N-carboxyanhydride). Nucleophile: e.g., Leu-OMe hydrochloride.

- Base: Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃).

- Solvent: Acetone (used minimally, if required).

- Equipment: Co-rotating twin-screw extruder with multiple independent temperature zones and a solid powder feeder.

- Methodology:

- Pre-mixing: Manually mix the electrophile, nucleophile, and base in an equimolar ratio (1:1:1). For minimal solvent conditions, a small volume of acetone (e.g., 0.15 mL/g of amino acid) can be added to the powder blend.

- Extruder Setup:

- Screw Configuration: Configure screws with a combination of conveying and kneading elements to ensure efficient mixing and shearing.

- Temperature Profile: Set a precise temperature gradient along the barrel zones (e.g., from lower temperatures at the feed port to the optimal coupling temperature in the reaction zone). This profile is crucial for controlling the reaction.

- Screw Speed: Set between 50-150 rpm.

- Feed Rate: Calibrate the solid feeder to a specific rate (e.g., 0.2-0.5 g/min) to define the residence time.

- Process Execution: Start the extruder and feeder. Collect the solid strand of product as it exits the die.

- Work-up & Analysis: The product often requires no further purification. Analyze conversion and purity by NMR and HPLC [4].

Protocol: Solvent-Free Aldimine Synthesis via Single-Screw Extrusion

This protocol details a continuous, catalyst-free method for imine synthesis, highlighting the applicability of simpler extrusion technology [31].

- Objective: To synthesize aldimines continuously from aldehydes and amines without solvent or catalyst.

- Materials:

- Aldehyde: e.g., Benzaldehyde.

- Amine: e.g., 4-trans-Aminocyclohexanol.

- Equipment: Single-screw extruder with temperature control.

- Methodology:

- Pre-mixing: Briefly mix the aldehyde and amine in a 1:1 molar ratio using a mortar and pestle.

- Extruder Setup:

- Temperature: Set the barrel temperature to an optimized point (e.g., 80°C).

- Screw Speed: Set to an optimized speed (e.g., 40 rpm).

- Process Execution: Feed the pre-mixed powder into the extruder hopper. Collect the solid product output.

- Work-up & Analysis: The product is typically obtained in high purity and yield without purification. Characterize via melting point, NMR, and IR spectroscopy [31].

Research Reagent Solutions for Mechanochemistry

The following table lists key materials and their functions in mechanochemical synthesis, based on the protocols and studies cited.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Mechanochemical Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Mechanosynthesis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid N-Carboxyanhydrides (NCAs) | Activated electrophile for peptide bond formation [4]. | TSE synthesis of dipeptides and tripeptides [4]. |

| Amino Acid N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) Esters | Activated electrophile with a good leaving group for amide/peptide coupling [4]. | TSE synthesis of peptides using alternative coupling chemistry [4]. |

| Grinding Auxiliaries (e.g., SiO₂) | Glidants or grinding agents that prevent caking, improve flow, and provide a reactive surface area [28]. | Added to reaction mixtures in ball milling or TSE to facilitate mixing and prevent clogging. |

| Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) Agents | Small, catalytic quantities of solvent that can accelerate reactions, improve homogeneity, or facilitate product formation [28] [29]. | Used in both ball milling and TSE to enhance reaction kinetics without the environmental burden of bulk solvent. |

| Inorganic Bases (e.g., NaHCO₃, K₂CO₃) | Scavenge acids (e.g., HCl) generated in-situ during coupling reactions [4] [30]. | Essential for reactions like peptide coupling or Knoevenagel condensation in solid-state or minimal solvent conditions. |

Technology Selection Workflow and Strategic Implementation

The decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate technology can be visualized in the following workflow, which integrates performance goals with practical constraints.

Strategic Implementation for Sustainable Development

Aligning technology choice with SDGs requires a holistic view. Twin-screw extrusion directly addresses SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by enabling continuous, waste-minimizing manufacturing with drastically reduced solvent use and higher space-time yields [4] [28]. Its scalability makes it a direct enabler of green chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry.

Ball milling, while less scalable, is a powerful tool for SDG 12 in the research and development phase. It allows chemists to rapidly explore solvent-free routes, discover novel synthetic pathways, and synthesize compounds that are difficult to access in solution, laying the groundwork for future sustainable processes [29] [27].

Continuous-flow systems for liquid reactions contribute to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) by improving the safety and controllability of processes involving hazardous intermediates. While they typically use solvents, their high efficiency and potential for integration with renewable resources position them as a key part of the broader sustainable engineering toolkit [28].

Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)

The synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) is a critical process in drug development, with significant implications for manufacturing efficiency, environmental impact, and overall sustainability. Traditionally, API production has relied heavily on solution-based methods that consume substantial amounts of potentially hazardous solvents. With growing pressure to adopt more sustainable practices in pharmaceutical manufacturing, mechanochemistry has emerged as a transformative approach that utilizes mechanical force to drive chemical reactions, often under solvent-free or minimal solvent conditions. This comparison guide objectively evaluates both methodologies within the context of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), focusing on empirical data, experimental protocols, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mechanochemistry represents a paradigm shift in synthetic chemistry, harnessing mechanical energy through techniques such as ball milling, grinding, or twin-screw extrusion (TSE) to facilitate chemical transformations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has recognized mechanochemistry as one of ten chemical innovations poised to transform the world, highlighting its potential to address pressing global sustainability challenges [32]. This review systematically compares these approaches through quantitative green metrics, experimental data, and practical applications in API synthesis.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Green Metrics Assessment

Direct comparison of traditional and mechanochemical processes reveals substantial differences in environmental performance and efficiency. A comprehensive review comparing conventional and mechanosynthesis methods for nine different APIs containing common reaction types found consistent advantages for mechanochemical approaches across multiple green chemistry metrics [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Green Metrics for Traditional vs. Mechanochemical API Synthesis

| Green Metric | Traditional Synthesis | Mechanochemical Synthesis | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High | Significantly reduced | 2.5-3 fold reduction [32] |

| E-factor | High values typical | Dramatically lower | Varies by application |

| Atom Economy (AE) | Standard | Comparable or improved | Application-dependent |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency | Standard | Enhanced | Varies by application |

| Energy Consumption | Conventional requirements | Reduced by ~18-fold [32] | ~18-fold improvement |

| Space-Time Yield | Standard | 30-100 fold increase for dipeptides [4] | 30-100 fold improvement |

The analysis demonstrates that mechanochemistry more closely adheres to the core principles of green chemistry, including waste prevention, safer chemical use, and energy efficiency [14]. While not all mechanochemical reactions adhere to all 12 principles of green chemistry, they generally conform to more principles than traditional solution-based reactions.

Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation

Solvent usage represents one of the most significant differentiators between traditional and mechanochemical API synthesis. Traditional solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), the current industry standard for therapeutic peptide production, typically utilizes a ratio of approximately 0.15 mL/mg of solvent to amino acid-bound resin, with solvents composing 80-90% of waste by mass [4].

In stark contrast, mechanochemical approaches using twin-screw extrusion achieve minimal solvent conditions of approximately 0.15 mL/g of acetone to amino acid, representing a reduction of over 1000-fold in solvent use compared to SPPS reactor couplings [4]. This dramatic reduction simultaneously minimizes environmental impact and reduces the economic burden associated with solvent purchase, recovery, and disposal.

Additionally, TSE utilizes an equimolar ratio of reacting amino acids while SPPS requires up to 10-fold amino acid excess, further contributing to waste reduction [4]. The elimination of costly polystyrene resins and their associated waste in SPPS presents additional economic and environmental advantages for mechanochemical approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Solution-Based Synthesis

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS)

Protocol Overview: SPPS involves sequential addition of amino acid derivatives to a growing peptide chain anchored to an insoluble resin support [4].

Detailed Methodology:

- Resin Swelling: Suspend polystyrene-based resin in dimethylformamide (DMF) or N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) for swelling

- Deprotection: Remove Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl) protecting group using piperidine solution (typically 20% v/v in DMF)

- Coupling: React amino acid derivatives (4-10 equiv.) with coupling agents such as ethyl cyanohydroxyiminoacetate (Oxyma) and N,N'-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) in DMF/NMP

- Washing: Rinse resin multiple times with DMF and dichloromethane between steps

- Cleavage: Liberate peptide from resin using trifluoroacetic acid-based cocktail

- Purification: Isolate product via precipitation and liquid chromatography

Typical Reaction Conditions: Ambient temperature, batch processing in 6000 L reactors for industrial scale [4]

Key Reagents: DMF, NMP, DIC, Oxyma, piperidine, trifluoroacetic acid

Scale-Up Considerations: Linear scalability but with proportional increase in solvent consumption and waste generation

Mechanochemical Synthesis

Ball Milling for API Synthesis

Protocol Overview: Mechanical force applied through grinding or milling enables chemical transformations in solid state or with minimal solvent [14] [33].

Detailed Methodology:

- Material Preparation: Weigh solid reactants precisely - typical stoichiometric ratios of 1:1 for reactants

- Milling Assembly: Load reactants into milling jar with grinding media (balls)

- Milling Parameters: Set frequency (typically 15-30 Hz) and time (minutes to hours)

- Process Monitoring: Monitor temperature, potentially with in-situ spectroscopy

- Product Recovery: Collect product by sieving or washing from milling assembly

Equipment Options: Planetary ball mills, vibratory/mixer mills, attritor mills, drum mills for kilogram-scale production [34] [33]

Reaction Scale: Milligram to kilogram scale demonstrated [34]

Key Advantages: No solvent required, rapid reaction times (minutes), ambient temperature operation

Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE) for Peptide Synthesis

Protocol Overview: Continuous flow mechanochemical synthesis using intermeshing screws in a barrel to facilitate peptide bond formation [4].

Detailed Methodology:

- Reagent Preparation: Pre-mix amino acid derivatives (electrophile and nucleophile) in 1:1 ratio with base (e.g., sodium bicarbonate)

- Extruder Setup: Configure temperature profile across multiple zones (typical range 25-90°C)

- Feeding: Introduce powder blend into extruder via hopper

- Reaction: Maintain residence time through screw configuration and speed control

- Collection: Collect product at die exit

Specific Conditions for Model Dipeptide (Boc-Val-Leu-OMe):

- Amino Acid Derivatives: Boc-Val-NCA (electrophile), Leu-OMe HCl (nucleophile)

- Base: Sodium bicarbonate

- Temperature Profile: Graduated increase across barrel zones

- Solvent Usage: Solvent-free to minimal solvent (0.15 mL/g acetone)

- Throughput: Demonstrated at various scales with kilogram-per-hour capacity [4]

Scale-Up Considerations: Continuous process with linear scale-up potential, minimal change in process parameters

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Mechanochemical API Synthesis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Role | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | Delivers mechanical energy via impact and friction | API co-crystal formation, metal-organic frameworks [33] |

| Twin-Screw Extruder | Continuous mechanochemical processing | Peptide synthesis, co-crystals at multi-kilogram scale [4] [33] |

| Amino Acid N-Carboxyanhydrides | Activated electrophiles for peptide coupling | Mechanochemical dipeptide synthesis [4] |

| Amino Acid N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters | Activated carboxylate components | Peptide bond formation in TSE [4] |

| Grinding Auxiliaries | Control reactivity, prevent agglomeration | Ionic liquids, catalysts in milling processes [32] |

| Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) Additives | Minimal solvent to enhance reactivity | Catalytic amounts of solvents in mechanosynthesis [35] |

| Stainless Steel Milling Media | Grinding balls for energy transfer | General mechanochemical reactions [34] |

Applications and Case Studies

Kilogram-Scale Co-crystal Production

A landmark study demonstrated the kilogram-scale synthesis of rac-ibuprofen:nicotinamide co-crystals using a drum mill, repurposing common industrial milling equipment for pharmaceutical co-crystal production [34]. The optimized process was completed within 90 minutes using liquid-assisted grinding techniques and yielded 99% pure co-crystals by simply sieving off the grinding media. Analysis showed minimal metal contamination from abrasion, with levels well within acceptable regulatory standards for daily intake, underscoring the industrial viability of this approach [34].

Peptide Synthesis via Twin-Screw Extrusion

Mechanochemical synthesis of therapeutic peptides via TSE presents a viable green alternative to SPPS, successfully producing a diverse array of dipeptides and a tripeptide at various scales and throughputs [4]. The methodology demonstrated compatibility with common protecting and leaving groups of amino acids, as well as various commercially available amino acid derivatives. Sequential TSE reactions successfully produced a model tripeptide, highlighting the technique's versatility for potential industrial therapeutic peptide production [4].

Late-Stage Functionalization of APIs

Mechanochemical strategies have been successfully applied to the late-stage modification of structurally complex APIs, enabling precise alterations to pharmacologically relevant frameworks [36]. These transformations fine-tune biological properties such as potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and solubility. The demonstrated reactions include C-C bond formation, C-N bond formation, C-O bond formation, and C-X bond formation on marketed drugs, providing valuable routes for generating analogues from existing scaffolds and facilitating structure-activity relationship studies [36].

Process Visualization

The comparative analysis demonstrates that mechanochemistry offers substantial advantages over traditional solution-based methods for API synthesis, particularly in alignment with Sustainable Development Goals. The dramatic reduction in solvent consumption (up to 1000-fold), decreased energy requirements (approximately 18-fold reduction), and improved space-time yields (30-100 fold increase) position mechanochemistry as a transformative approach for sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing [14] [4] [32].

While challenges remain in mechanistic understanding, industrial scalability, and cross-laboratory reproducibility, recent advancements in in-situ monitoring techniques and equipment design are rapidly addressing these limitations [32] [33]. The successful demonstration of kilogram-scale production for pharmaceutical co-crystals and continuous-flow peptide synthesis confirms the industrial viability of mechanochemical approaches [4] [34].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mechanochemistry presents opportunities to develop more sustainable synthetic routes while maintaining or even enhancing efficiency and selectivity. The integration of mechanochemical strategies into pharmaceutical development pipelines represents a significant step toward greener manufacturing processes that reduce environmental impact while maintaining the high-quality standards required for pharmaceutical applications.

The development of pharmaceutical cocrystals and salts represents a crucial strategy in modern drug development for enhancing the physicochemical properties of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), particularly for overcoming poor solubility challenges that affect approximately 90% of developmental pipeline drugs [37]. These multicomponent solid forms enable the fine-tuning of critical pharmaceutical properties including solubility, dissolution rate, bioavailability, and stability without modifying the API's chemical structure or intrinsic pharmacological activity [38] [39]. Within the context of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to adopt greener synthetic methodologies [16]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional solution-based chemistry and emerging mechanochemical approaches for the preparation of pharmaceutical cocrystals and salts, supported by experimental data and protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Concepts: Cocrystals vs. Salts

Definitions and Key Distinctions

Pharmaceutical salts are ionic compounds formed through proton transfer from an acid to a base when the pKa difference (ΔpKa) between the API and counterion is typically greater than 2-3 units [40]. Salts represent approximately 50% of FDA-approved drug products, with hydrochloride salts alone accounting for 54% of approved salt forms [40] [39].

Pharmaceutical cocrystals are crystalline materials comprising two or more neutral molecular components in the same crystal lattice, stabilized by non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, or van der Waals forces [37] [39]. The FDA defines cocrystals as "solids that are crystalline materials composed of two or more molecules in the same crystal lattice" where components remain in neutral states [39].

A salt-cocrystal continuum may exist in certain systems where the proton position depends on environmental factors such as temperature, demonstrating that the distinction between salts and cocrystals is not always absolute [39].

Thermodynamic and Solubility Considerations

The solubility behavior of salts and cocrystals follows distinct thermodynamic patterns. A study comparing salts and cocrystals of lamotrigine (LTG), a basic drug with pKa 5.7, demonstrated that cocrystals can sometimes outperform salts in solubility enhancement [38]. The supersaturation index (SA = SCC/SD or Ssalt/SD) followed this order: LTG-Nicotinamide cocrystal (18) > LTG-HCl salt (12) > LTG-Saccharin salt (5) > LTG-Methylparaben cocrystal (1) > LTG-Phenobarbital cocrystal (0.2) [38].

Both cocrystal and salt solubility exhibit strong pH dependence, with pHmax values (the pH at which the cocrystal/salt and drug have equal solubility) ranging from 5.0 for LTG-Saccharin salt to 9.0 for LTG-Phenobarbital cocrystal [38]. This pH dependence must be carefully considered when predicting performance in biological systems.

Table 1: Comparative Solubility Parameters for Lamotrigine (LTG) Salts and Cocrystals [38]

| Solid Form | Type | Supersaturation Index (SA) | pHmax | pKsp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTG-Nicotinamide | Cocrystal | 18 | ~6.0 | - |

| LTG-HCl | Salt | 12 | ~5.5 | - |

| LTG-Saccharin | Salt | 5 | 5.0 | - |

| LTG-Methylparaben | Cocrystal | 1 | 6.4 | - |

| LTG-Phenobarbital | Cocrystal | 0.2 | 9.0 | - |

Traditional Solution-Based Synthesis

Methodologies and Protocols

Traditional solution-based methods remain the conventional approach for preparing pharmaceutical cocrystals and salts. These techniques involve dissolving API and coformer in appropriate solvents, followed by crystallization through various approaches:

Reaction Crystallization Method (RCM): For LTG-NCT·H2O cocrystal, an aqueous solution containing 2% w/w SLS and 3.5 M nicotinamide was prepared, to which anhydrous LTG was added and stirred for 72 hours at ambient temperature [38].

Solvent Evaporation: For dihydromyricetin (DMY) and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP) cocrystal, equimolar quantities (0.5 mmol each) were dissolved in 15 mL of 50% ethanol, stirred at 60°C for 4 hours, then filtered into containers for slow evaporation at room temperature [41]. Transparent needle-shaped crystals typically formed within one week.

Slurry Crystallization: Suspending stoichiometric mixtures of API and coformer in appropriate solvents with continuous agitation until crystalline products form.

Advantages and Limitations

Traditional solution-based methods offer excellent control over crystal size, habit, and purity, with established scalability for industrial production. However, these methods typically consume large volumes of organic solvents, generating significant waste with Environmental Factors (E-factors) ranging from 25 to >100 kg waste per kg API [16]. Additional limitations include potential solvate formation, polymorphism issues, and incompatibility with poorly soluble compounds.

Mechanochemical Synthesis

Methodologies and Protocols

Mechanochemistry utilizes mechanical energy rather than solvents to drive chemical reactions, offering a sustainable alternative for cocrystal and salt formation. Key approaches include:

Neat Grinding (NG): API and coformer are ground together without solvents using mechanical mills such as ball mills or vibratory mills.

Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG): Minimal catalytic amounts of solvent are added to enhance molecular mobility and reaction kinetics. For example, the mechanosynthesis of teriflunomide involves a two-step process where carboxylic acid is first activated with CDI at 500 rpm for 20 minutes, followed by reaction with amine hydrochloride ground for 5 hours at 500 rpm [16].

Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE): A continuous mechanochemical method suitable for larger-scale production, overcoming batch processing limitations of traditional ball milling [16].

Advantages and Limitations