Overcoming Matrix Interference: Advanced Strategies for Accurate Trace-Level Contaminant Detection

This article provides a comprehensive examination of matrix interference, a critical challenge in the accurate detection of trace-level contaminants in complex biological and environmental samples.

Overcoming Matrix Interference: Advanced Strategies for Accurate Trace-Level Contaminant Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of matrix interference, a critical challenge in the accurate detection of trace-level contaminants in complex biological and environmental samples. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms of matrix effects, from ionization suppression in mass spectrometry to unexpected changes in chromatographic behavior. The content details robust methodological approaches for sample preparation and analysis, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks to ensure data reliability. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with applied solutions, this guide serves as an essential resource for developing precise and robust analytical methods in biomedical research and environmental monitoring.

Understanding the Enemy: A Deep Dive into the Sources and Mechanisms of Matrix Effects

FAQ: Understanding Matrix Interference

What is matrix interference in analytical chemistry?

Matrix interference refers to the effect caused by extraneous components in a sample (the "matrix") that are not the target analyte but disrupt the accurate detection and quantification of that analyte [1] [2]. The matrix is the portion of the sample that is not the analyte—essentially, most of the sample [3]. These interfering components can be proteins, lipids, salts, carbohydrates, or other organic or inorganic compounds inherent to the sample, such as blood, urine, soil, or food [1] [4] [2].

What are the common consequences of matrix interference?

Matrix interference can manifest in several ways, leading to:

- Inaccurate Results: False increases or decreases in the reported concentration of the target analyte [1] [5].

- Reduced Sensitivity and Precision: A loss of assay sensitivity and an increase in data variability [1] [6].

- Instrumental Issues: In LC-MS/MS, matrix components can contaminate the ion source, leading to increased downtime for maintenance and cleaning [6].

- Chromatographic Problems: Unusually shaped or overlapping peaks, which complicate quantification [7].

Which detection techniques are most susceptible to matrix effects?

Different detection principles are susceptible to different interference mechanisms [3]. The following table summarizes key vulnerabilities:

Table: Matrix Interference Mechanisms Across Detection Techniques

| Detection Technique | Primary Interference Mechanism | Common Result |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) - Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Competition for available charge during ionization; altered droplet formation efficiency [3] [4]. | Ion suppression or enhancement [8] [4]. |

| Fluorescence Detection | Interference with the fluorescence quantum yield of the analyte [3]. | Fluorescence quenching (signal suppression) [3]. |

| UV/Vis Absorbance Detection | Changes in the solvent environment affecting light absorption [3]. | Signal enhancement or suppression via solvatochromism [3]. |

| Evaporative Light Scattering (ELSD) & Charged Aerosol Detection (CAD) | Influence of non-volatile additives on the aerosol formation process [3]. | Signal enhancement or suppression [3]. |

How can I detect the presence of matrix interference in my LC-MS/MS assay?

Two common methodologies are used to detect matrix effects:

- Post-Extraction Spiking: A known amount of the pure analyte is added to a pre-processed (extracted) blank sample matrix. The detector response for this sample is then compared to the response for the same amount of analyte in a pure solution [8] [4]. A difference in response indicates a matrix effect.

- Post-Column Infusion: A solution of the analyte is continuously infused into the LC effluent post-column while a blank, extracted sample matrix is injected into the LC system [3] [8]. A steady analyte signal should result; any suppression or enhancement dips in the chromatogram correspond to the elution time of interfering matrix components [3].

What are the most effective strategies to mitigate matrix interference?

A multi-pronged approach is often necessary to manage matrix interference:

- Sample Preparation: Techniques like dilution, filtration, centrifugation, and solid-phase extraction can physically remove or reduce the concentration of interfering components [1] [6]. Simple sample dilution is often a very effective first step, provided the assay is sufficiently sensitive [8].

- Chromatographic Optimization: Improving the separation between the analyte and interfering compounds by adjusting the column chemistry, mobile phase, or gradient can prevent them from co-eluting and causing interference at the detector [8].

- Internal Standardization: Using a stable isotope-labeled (SIL) internal standard is considered a "gold standard" for correcting matrix effects in quantitative MS [8]. Because the SIL-IS is nearly identical to the analyte and co-elutes with it, it experiences the same matrix-induced ionization effects, allowing for accurate correction [3] [8]. A structural analogue can also be used if a SIL-IS is unavailable [8].

- Standard Addition: This method involves adding known quantities of the analyte to the sample itself and measuring the response [8]. It is particularly useful for complex matrices where a blank matrix is unavailable, but it is more labor-intensive [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Matrix Effects via a Spike-and-Recovery Experiment

This experiment determines if your sample matrix affects the accurate detection of the analyte compared to the assay's standard buffer [5].

Objective: To calculate the percent recovery of a known analyte spike to assess matrix interference. Materials:

- Test sample matrix (e.g., plasma, urine)

- Assay diluent/buffer (from your kit)

- Recombinant protein standard/pure analyte

- Microplate reader or other relevant detector

Procedure:

- Prepare Samples:

- Standard in Buffer: Add a known concentration of the pure analyte standard into the assay diluent.

- Spiked Sample Matrix: Add the same known concentration of the pure analyte standard into your neat or diluted sample matrix.

- Unspiked Sample Matrix: Prepare a control of your sample matrix without the added spike.

- Run Analysis: Process all samples according to your analytical method (e.g., ELISA, LC-MS) and interpolate the observed concentration for each from the standard curve [5].

- Calculate Percent Recovery: Use the formula below.

Interpretation: Recoveries of 80-120% are generally considered acceptable, indicating minimal matrix interference [5]. Significant deviations suggest interference that must be mitigated [5].

Protocol 2: Performing a Linearity-of-Dilution Experiment

This experiment validates whether a sample can be accurately diluted to fall within the assay's dynamic range and checks for the presence of non-linear effects like the "hook effect" [5].

Objective: To demonstrate that a sample can be serially diluted and still produce accurate, proportional results. Materials:

- Sample with high analyte concentration

- Assay diluent

- Equipment for serial dilution and analysis

Procedure:

- Serial Dilution: Perform a series of factored dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) of the sample using the approved assay diluent.

- Analysis: Analyze all dilutions using your standard method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the observed concentration for each dilution and then multiply by the dilution factor to obtain the "back-calculated" original concentration.

Interpretation: A sample with ideal linearity-of-dilution will show consistent back-calculated concentrations across the dilution series [5]. A trend where the calculated concentration increases with higher dilution suggests the presence of an interfering substance that is being diluted out [5].

Table: Example Data from a Linearity-of-Dilution Experiment

| Dilution Factor | Observed Concentration | Back-Calculated Concentration (Dilution Factor × Observed) | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:2 | 48 ng/mL | 96 ng/mL | Poor linearity (results not consistent) |

| 1:4 | 28 ng/mL | 112 ng/mL | |

| 1:8 | 15 ng/mL | 120 ng/mL | |

| 1:16 | 7.5 ng/mL | 120 ng/mL | Good linearity achieved |

Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Matrix Interference

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Managing Matrix Effects

| Reagent / Material | Function in Mitigating Interference |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-IS) | Co-elutes with the analyte and experiences identical matrix effects, providing a reliable reference for quantification correction in MS [8]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Selectively binds and purifies the analyte away from interfering matrix components like phospholipids and salts during sample preparation [8]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Added to assay buffers to occupy non-specific binding sites on surfaces or antibodies, reducing background noise in immunoassays [1]. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration Standards | Standards are prepared in a matrix that closely resembles the sample (e.g., synthetic urine, stripped serum) to mimic and account for matrix effects during calibration [1]. |

| Buffering Concentrates | Used to adjust and neutralize sample pH, rectifying pH-related interference that can affect antibody binding or chromatographic separation [1]. |

Matrix interference occurs when components in a sample affect the accuracy and precision of analytical measurements. For researchers detecting trace-level contaminants, interference from co-existing substances like heavy metals, organic matter, lipids, and salts presents a significant challenge. These components can cause signal suppression or enhancement, leading to inaccurate quantification. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice to help you identify, mitigate, and correct for these common interferents in your analytical workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My potentiometric sensor performs well in clean solutions but fails in high-salt samples like seawater. What can I do? A: High saline concentrations form a major interfering background that can mask the target analyte signal. A practical solution is to use an online electrochemically modulated preconcentration and matrix elimination (EMPM) system.

- Mechanism: This hyphenated system preconcentrates trace metals (e.g., cadmium) onto an electrode, then releases them into a medium favorable for detection, such as calcium nitrate, thereby circumventing the original saline matrix [9].

- Protocol:

- Use a bismuth-coated glassy carbon working electrode in a flow cell.

- Apply a deposition potential (e.g., -0.6 V) to accumulate target metals from the saline sample.

- Switch to an oxidizing potential to release the deposited metals.

- Direct the released metals into a calcium nitrate stream for detection with a solid-contact ion-selective electrode [9].

Q2: How do I prevent false positives or high background in my ELISA due to laboratory contaminants? A: ELISA kits are extremely sensitive, and concentrated sources of analytes (e.g., cell culture media, sera) in the lab environment can easily contaminate reagents.

- Best Practices:

- Dedicated Areas: Do not perform the assay in areas where concentrated forms of your analyte are handled.

- Aerosol Management: Use pipette tips with aerosol barrier filters. Do not talk or breathe over an uncovered microtiter plate.

- Equipment Segregation: Use dedicated pipettes and plate washers for the ELISA. Washers previously exposed to concentrated analytes can remain a source of contamination even after flushing.

- Reagent Handling: Recap all reagent bottles immediately after use. For alkaline phosphatase substrates (e.g., PNPP), withdraw only the needed amount to avoid environmental contamination from airborne bacteria or human dander [10].

Q3: My LC-MS/MS analysis of organic compounds in complex wastewater shows severe ion suppression. What strategies can help? A: High salinity and organic content can cause significant ion suppression in electrospray ionization (ESI). A robust method combines sample cleanup and internal standardization.

- Mechanism: Matrix components compete for ionization energy and can coprecipitate with analytes or reduce droplet evaporation efficiency [11].

- Solution Workflow:

- Solid Phase Extraction (SPE): Use SPE to desalt the sample and remove interfering organic matter.

- Stable Isotope Standards: Employ a suite of stable isotope-labelled internal standards (one for each target compound). These standards correct for ion suppression, SPE losses, and instrument variability, as they experience the same matrix effects as the native analytes [11].

Q4: What is the most effective way to quantify multiple heavy metals in a complex plant biomass sample? A: Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) is the dominant technique for ultra-trace multi-element analysis, but sample preparation is key.

- Sample Preparation - Microwave Digestion: This is a best practice for achieving high accuracy. It enables precise elemental recovery, lower detection limits, faster throughput, and reduced contamination risk compared to open-vessel digestion [12].

- Nebulizer Selection: For complex matrices, an innovative nebulizer with a non-concentric design and a larger sample channel diameter is recommended. This design provides superior resistance to clogging from particulates or high salt levels, reducing maintenance and downtime [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Heavy Metal Interference

- Symptoms: Unstable signal in potentiometry; inaccurate quantification in spectroscopic techniques; suppressed analyte signal in ICP-MS.

- Sources: Environmental samples, industrial effluents, biological tissues [13] [14].

- Solutions:

- Biosorption: Use low-cost lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., sawdust, bark) as a biosorbent to pre-concentrate and remove interfering heavy metals from aqueous samples [13].

- ICP-MS Optimization: Use collision/reaction cell technology to mitigate polyatomic interferences. For high dissolved solids, employ robust sample introduction systems with aerosol dilution/filtration to minimize cone clogging and matrix deposition [12].

Organic Matter & Lipid Interference

- Symptoms: High background noise in ELISA; ion suppression/enhancement in LC-MS/MS; co-elution during chromatographic separation.

- Sources: Humic substances in environmental waters, lipids in biological fluids (plasma, serum), cell culture media components [10] [14] [15].

- Solutions:

- Enhanced Extraction and Cleanup: For sediment or tissue samples, use techniques like Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) extraction or accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) to efficiently separate analytes from the organic matrix [16].

- Comprehensive LC Separation: Utilize mixed-mode liquid chromatography, which combines multiple separation mechanisms (e.g., reversed-phase and ion-exchange), to better resolve analytes from complex organic backgrounds [11].

Salt Interference

- Symptoms: Signal suppression in ESI-based MS; reduced activity of target ions in potentiometric sensors; capillary clogging in ICP-MS.

- Sources: Seawater (0.5 M NaCl), produced waters from oil and gas operations (salinity can range from 2000–30000 mg L⁻¹) [9] [11].

- Solutions:

- Electrochemical Matrix Elimination (EMPE): As detailed in FAQ A1, this technique physically separates analytes from the salt matrix [9].

- Solid Phase Extraction (SPE): Effective for desalting samples prior to LC-MS/MS or ICP-MS analysis [11].

- Internal Standardization: The use of isotope-labelled internal standards is critical for correcting for signal fluctuations caused by variable salt content [11].

Experimental Protocols for Matrix Challenge Studies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Matrix Effects in LC-MS/MS using Post-column Infusion

- Purpose: To visually identify regions of ion suppression or enhancement in a chromatographic run.

- Materials: LC-MS/MS system, syringe pump, T-connector, standard solution of the analyte.

- Steps:

- Prepare a constant infusion of your analyte standard using a syringe pump connected post-column via a T-connector.

- Inject a blank, but otherwise representative, sample extract (from your complex matrix) into the LC stream.

- Monitor the MS signal. A dip in the baseline indicates ion suppression, while a peak indicates ion enhancement at that specific retention time.

Protocol 2: Standard Addition for Quantification in Complex Matrices

- Purpose: To account for matrix effects that alter analytical sensitivity, providing more accurate quantification.

- Materials: Sample aliquots, concentrated standard solution, calibration solvents.

- Steps:

- Take several equal-volume aliquots of your unknown sample.

- Spike increasing, known amounts of the analyte standard into each aliquot, except one (the "blank" spike).

- Analyze all aliquots and plot the measured signal versus the concentration of the added standard.

- The absolute value of the x-intercept of the linear plot equals the concentration of the analyte in the original sample. This method corrects for multiplicative matrix effects.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Mitigating Matrix Interference

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Standards | Internal standards for mass spectrometry; correct for matrix-induced signal variation and preparation losses. | Quantifying ethanolamines in high-salinity produced waters [11]. |

| Bismuth-Film Electrode | An environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes for electrochemical preconcentration of trace metals. | Cadmium detection in seawater samples [9]. |

| Lignocellulosic Biosorbents | Low-cost sorbents for pre-concentrating or removing heavy metals from aqueous solutions. | Treatment of industrial wastewater [13]. |

| Mixed-Mode SPE Sorbents | Stationary phases with multiple interaction mechanisms (e.g., reversed-phase and ion-exchange) for selective cleanup. | Isolation of analytes from complex biological or environmental extracts [11]. |

| Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | A solid-contact material for ion-selective electrodes, improving potential stability. | Fabrication of solid-contact Cd²⁺-selective microelectrodes [9]. |

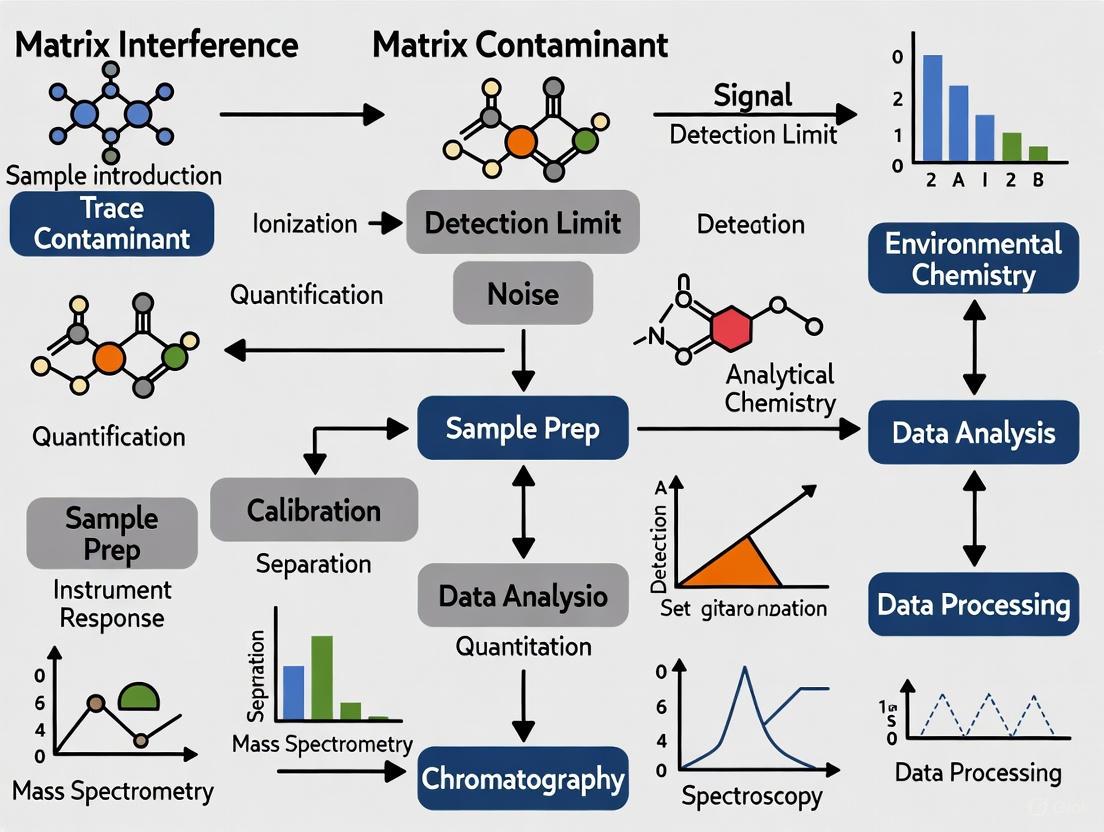

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Matrix Interference Troubleshooting Logic

Matrix Troubleshooting Logic

Diagram 2: LC-MS/MS Workflow with Matrix Mitigation

LC-MS/MS Matrix Mitigation Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of ion suppression in LC-MS? Ion suppression occurs when co-eluting substances from the sample matrix interfere with the ionization efficiency of your target analyte in the mass spectrometer's ion source. These matrix components can compete for charge or disrupt the droplet formation and evaporation process during electrospray ionization (ESI), leading to a reduced signal for your analyte [17] [18]. The effect is highly dependent on the specific chemistry of your sample and the chromatographic conditions.

Q2: My analyte signal has suddenly dropped. How can I quickly check if ion suppression is the cause? The most direct way to test for ion suppression is by performing a post-column infusion assay [18]. Continuously infuse your analyte into the MS detector while injecting a blank, matrix-free sample onto the LC column. A stable baseline indicates no suppression, whereas dips or drops in the signal at specific retention times correspond to regions where matrix components from the blank are causing suppression. Alternatively, you can compare the signal of your analyte in a neat solution to its signal when spiked into the sample matrix [17].

Q3: For my method analyzing phosphorylated compounds, I observe poor peak shape and low recovery. Could the hardware be a factor? Yes. Compounds that can chelate metals, such as organophosphorus pesticides (e.g., glyphosate) or nucleoside triphosphates, can interact with the metal surfaces (typically stainless steel 316) in standard HPLC columns and tubing [19]. This can cause adsorption, sample loss, and the formation of metal salts that lead to severe ion suppression. A key troubleshooting step is to switch to a metal-free HPLC column, which features PEEK-coated internal surfaces to prevent these interactions [19].

Q4: Are there advanced computational or sample preparation methods to correct for ion suppression? Yes. In non-targeted metabolomics, methods like the IROA (Isotopic Ratio Outlier Analysis) TruQuant Workflow use a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (IROA-IS) library to measure and computationally correct for ion suppression in each sample [17]. From a sample preparation perspective, techniques such as solid-phase extraction (SPE) or protein precipitation are highly effective at removing the endogenous interferences that cause suppression [18]. Nanohybrid-based clean-up technologies are also emerging for enhanced selectivity in complex matrices [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low analyte signal, poor sensitivity | Ion suppression from co-eluting matrix; Source contamination [18] | Optimize sample clean-up (e.g., SPE); Improve chromatographic separation; Use a metal-free column for chelating analytes [19] [18] | Incorporate efficient sample preparation; Regular ion source cleaning and maintenance [18] |

| Poor peak shape (tailing, broadening) for phosphorylated or chelating compounds | Analyte adsorption to active metal sites in LC system/column [19] | Switch to a metal-free LC column with PEEK-lined internals [19] | Use metal-free components (columns, tubing) for methods analyzing chelating compounds [19] |

| Signal drift and loss of precision over a batch run | Progressive buildup of contaminants in the ion source [18] | Clean the ion source; Use a guard column; Increase column washing between injections [18] | Implement a robust sample clean-up procedure; Use a guard column; Schedule routine instrument maintenance [21] [18] |

| High background noise, inconsistent MRM transitions | In-source contamination or suboptimal collision energy [18] | Re-tune and re-calibrate the instrument; optimize MRM transitions and collision energy [18] | Regularly run system suitability tests with quality control samples [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Using Metal-Free Columns to Overcome Suppression for Chelating Compounds

This protocol is adapted from a study examining organophosphorus pesticides and nucleoside triphosphates [19].

- Objective: To recover signal strength and improve peak shape for analytes prone to metal chelation.

- Materials:

- Standard HPLC column (stainless steel hardware) and a comparable metal-free column.

- Analytical standards of your target analytes (e.g., glyphosate, nucleoside triphosphates).

- Appropriate mobile phases (e.g., typical reversed-phase or ion-pairing solvents).

- Method:

- Set up your LC-MS system with the standard stainless-steel column.

- Inject the analyte standard and record the chromatogram and MS signal.

- Without changing any other parameters (mobile phase, gradient, MS method), replace the standard column with the metal-free column.

- Re-inject the same analyte standard.

- Expected Outcome: A dramatic improvement in signal strength and peak symmetry is expected on the metal-free column. In the cited study, glyphosate signal was completely absent on the metal column but was successfully detected using the metal-free hardware [19].

Protocol 2: The IROA TruQuant Workflow for Ion Suppression Correction in Non-Targeted Metabolomics

This protocol summarizes a comprehensive method for measuring and correcting ion suppression [17].

- Objective: To quantitatively correct for ion suppression across all detected metabolites in a complex sample.

- Materials:

- IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS): A library of metabolites synthesized with 95% 13C-labeling.

- IROA Long-Term Reference Standard (IROA-LTRS): A 1:1 mixture of the same metabolites at 95% 13C and natural 13C abundance.

- ClusterFinder software (IROA Technologies) or equivalent.

- Method:

- Spike a constant amount of the IROA-IS into all your experimental samples.

- Analyze the samples alongside the IROA-LTRS using your standard LC-MS method (compatible with RPLC, HILIC, or IC).

- The software identifies true metabolites by their unique IROA isotopolog ladder pattern—a decreasing amplitude in the 12C channel and an increasing amplitude in the 13C channel.

- The algorithm uses the signal loss observed in the spiked-in 13C-labeled standards to calculate and correct for the ion suppression affecting the corresponding endogenous (12C) metabolites using a dedicated equation.

- Key Equation (Simplified): The correction is based on the principle that the 12C and 13C isotopologs experience identical suppression. The signal for the endogenous metabolite (AUC-12C) is corrected using the observed (AUC-13Cobs) and expected (AUC-13Cexp) signals of the internal standard [17].

- Outcome: This workflow can nullify ion suppression effects ranging from 1% to over 90%, restoring linearity and quantitative accuracy [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-free HPLC Column | Prevents adsorption and ion suppression for chelating analytes by eliminating metal-contact surfaces [19]. | Analysis of organophosphorus pesticides (glyphosate), nucleotides, and phosphopeptides [19]. |

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | A library of 13C-labeled metabolites used to measure and computationally correct for ion suppression in each sample [17]. | Non-targeted metabolomics studies in complex biological matrices like plasma, urine, or cell cultures [17]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits | Selectively removes proteins, lipids, and other matrix interferences from samples prior to LC-MS analysis [18]. | Cleaning up plasma or tissue homogenate samples to reduce background noise and ion suppression [18]. |

| Pierce Peptide Desalting Spin Columns | Rapid removal of salts, detergents, and other small-molecule contaminants from peptide/protein samples [21]. | Desalting tryptic digests before LC-MS/MS analysis for proteomics. |

| Pierce HeLa Protein Digest Standard | A well-characterized standard used to test and validate the entire LC-MS/MS system performance and sample preparation workflow [21]. | Troubleshooting to isolate whether a problem originates from the sample preparation or the LC-MS instrument itself [21]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Ion Suppression Identification Flow

IROA Suppression Correction

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Matrix-Related Issues

Matrix effects occur when components in a sample other than the analyte (the "matrix") interfere with the chromatographic analysis, leading to inaccurate results. [3] These effects are a significant challenge for the accurate quantitation of trace-level contaminants, as they can alter the detector's response to the analyte. [3]

The table below summarizes frequent symptoms, their likely causes, and immediate corrective actions.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Retention Time Drift | Incomplete column equilibration; active sites becoming saturated over initial injections. [22] | Perform 5-6 rapid, initial injections to saturate active sites; disregard the first injection. [22] |

| Peak Tailing or Fronting | Sample solvent is stronger (more eluting) than the mobile phase. [22] | Dissolve the sample in a solvent that matches the mobile phase or is slightly weaker. [22] |

| Variable Peak Area/Height (especially with MS, ELSD, or CAD detection) | Ion suppression/enhancement (MS): Co-eluting compounds compete for available charge. [3]Aerosol formation effects (ELSD/CAD): Matrix components alter droplet formation. [3] | Dilute the sample; improve sample cleanup; use internal standard quantitation. [3] |

| Diurnal Retention Time Shifts | Laboratory temperature fluctuations affecting the column. [22] | Use a thermostatted column oven to maintain a constant temperature. [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is a "matrix effect" in chromatography?

The sample matrix is the portion of your sample that is not the analyte. [3] A matrix effect refers to the impact this matrix has on various parts of your LC method. For quantitation, the critical problem is that the matrix can enhance or suppress the detector's response to your analyte, making your quantitative results inaccurate. [3] This is most commonly discussed in the context of co-eluting compounds that enter the detector at the same time as your analyte. [3]

Q2: How can I quickly test if my method has a matrix effect?

A simple and effective approach is to compare detector responses under different conditions. [3] For example, you can prepare calibration standards in a pure solvent and in a blank matrix extract. If the slopes of the two calibration curves are significantly different, you have a matrix effect to address. [3]

For mass spectrometry, a common test is the post-column infusion experiment. [3] A dilute solution of the analyte is infused into the effluent stream after the column. As a blank matrix sample is injected, a constant analyte signal is monitored. A drop or rise in this signal during the chromatogram indicates regions of ion suppression or enhancement caused by eluting matrix components. [3]

Q3: What is the most effective way to compensate for matrix effects in quantitative analysis?

The internal standard (IS) method is one of the most potent tools for mitigating matrix effects. [3] It involves adding a known amount of a suitable compound (the internal standard) to every sample and standard. Quantitation is then based on the ratio of the analyte signal to the internal standard signal. [3] For this to work well, the internal standard should behave very similarly to the analyte throughout sample preparation and analysis. A stable isotopically-labeled version of the analyte is often the best choice. [3]

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Matrix Effects

Protocol 1: Post-Column Infusion for MS Detection

This experiment visually maps regions of ionization suppression or enhancement in your chromatographic method. [3]

- Setup: Connect a syringe pump containing a dilute solution of your analyte to a T-union placed between the column outlet and the MS inlet.

- Infusion: Start the infusion to maintain a stable, constant signal for your analyte.

- Injection: Inject a blank sample (containing the matrix but not the analyte) and run the chromatographic method.

- Observation: Monitor the signal for your infused analyte. A depression in the signal indicates ion suppression from co-eluting matrix; an increase indicates enhancement. [3]

The workflow for this diagnostic method is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Standard Addition for Quantitation in Complex Matrices

When matrix effects are severe and unavoidable, the standard addition method can be used to achieve accurate results.

- Preparation: Take several aliquots of your unknown sample.

- Spiking: Spike all but one aliquot with known and varying increasing amounts of the analyte standard.

- Analysis: Analyze all aliquots (including the unspiked one).

- Calculation: Plot the measured signal (e.g., peak area) against the amount of analyte added. The absolute value of the x-intercept (where the signal is zero) gives the concentration of the analyte in the original sample.

Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Matrix Interference

The following table details key materials and strategies used to prevent or compensate for matrix effects in trace analysis.

| Research Reagent / Strategy | Function in Mitigating Matrix Effects |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-IS) | The gold standard for compensation. [3] It has nearly identical chemical properties to the analyte, co-elutes, and experiences the same matrix-induced ionization effects, allowing for perfect correction. [3] |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | A sample preparation technique used to remove interfering matrix components and pre-concentrate analytes, thereby reducing the matrix load entering the LC-MS system. [23] |

| Sr-Resin | A specific chelating resin used in ICP-MS to selectively separate a heavy matrix (like lead) from trace impurities, dramatically reducing spectral interferences. [24] |

| Zwitterionic Detergents (e.g., DDAPS) | Used in capillary electrophoresis as a dynamic coating agent to suppress analyte adsorption to the capillary wall and modify the separation selectivity, improving peak shape and resolution in complex matrices. [25] |

| Column Equilibration with Mock Injections | The process of making several initial, rapid injections to actively saturate active sites on the stationary phase, leading to more stable retention times in subsequent analytical runs. [22] |

The table below consolidates key quantitative benchmarks and performance criteria related to matrix effects, as drawn from advanced analytical methodologies.

| Parameter | Impact / Acceptable Range | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Recovery & Matrix Effect | 60–130% [23] | Method robustness criteria for multiclass assays; values outside this range indicate significant interference. [23] |

| Method Precision (Inter-/Intra-day) | ≤ 30% RSD [23] | Acceptance criterion for multiclass biomarker analysis in exposomics. [23] |

| Retention Time Change with Temperature | ~2% decrease per 1°C increase [22] | A general rule of thumb highlighting the need for column temperature control. [22] |

| HAA Recovery in Validated Method | 82–118% [25] | Recovery performance for haloacetic acids in water, falling within the U.S. EPA acceptance range (70-130%). [25] |

| Regulatory Limit for Total HAAs | 60 µg/L [25] | U.S. EPA maximum contaminant level in drinking water, underscoring the need for accurate trace-level detection. [25] |

In the broader context of thesis research focused on addressing matrix interference in trace-level contaminant detection, understanding the direct impact of the sample matrix on detector response is paramount. The sample matrix, defined as all components of a sample other than the analyte of interest, can significantly alter analytical results through effects like fluorescence quenching and solvatochromism [26]. These phenomena are a substantial challenge in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring, as they can lead to suppressed or enhanced signals, ultimately compromising the accuracy and reliability of quantitative analyses [27] [3]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help researchers identify, understand, and mitigate these specific matrix effects.

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

Q1: What exactly is meant by "matrix effect" in analytical chemistry? In chemical analysis, the matrix refers to all components of a sample that are not the analyte of interest [26]. The matrix effect is the phenomenon where these components alter the detector's response to the analyte, leading to either signal suppression (a decrease) or signal enhancement (an increase) [27] [26]. This effect is quantifiable; a matrix effect value of 100 indicates no effect, a value less than 100 indicates suppression, and a value greater than 100 indicates enhancement [26].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between fluorescence quenching and solvatochromism? Both are matrix-dependent phenomena, but they operate through different mechanisms:

- Fluorescence Quenching: This occurs when matrix components cause a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the analyte. This is often due to interactions that provide non-radiative pathways for the excited state to return to ground state, effectively "quenching" the light emission [3]. For example, heavy atoms or specific ions in the matrix can facilitate this process [28].

- Solvatochromism: This is a change in the color (absorption or emission spectrum) of a compound depending on the solvent or matrix polarity [29]. It does not necessarily quench the signal but shifts its wavelength. A bathochromic (red) shift occurs with increasing polarity in positive solvatochromism, while a hypsochromic (blue) shift occurs in negative solvatochromism [29] [30].

Q3: How can I quickly check if my analysis is suffering from matrix effects? A common and effective strategy is to perform a simple comparison of detector responses under different conditions [3]. You can compare the calibration curve slope of your analyte in a pure solvent to the slope obtained when the analyte is in a matrix-matched solution or a representative sample extract. If the slopes are significantly different, a matrix effect is likely present. For mass spectrometry, the post-column infusion experiment is a standard diagnostic tool [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Matrix Interference

Problem 1: Unexplained Reduction in Fluorescence Signal

Potential Cause: Fluorescence quenching by matrix components. Solutions:

- Employ Far-Red Tracers: If using a fluorescence polarization assay, switch from a fluorescein-based tracer to a far-red tracer. These longer-wavelength probes are substantially less susceptible to interference from autofluorescent library compounds and scattered light from precipitated compounds [31].

- Modify Sample Preparation: Improve extraction and clean-up methods to remove the quenching agents from the sample matrix [27]. This could involve more selective solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges or additional purification steps.

- Use the Standard Addition Method: This technique involves adding known quantities of the analyte to the sample itself. It accounts for matrix effects by building a calibration curve in the exact sample matrix, thereby compensating for the quenching and providing a more accurate quantification [26].

Problem 2: Shifts in Wavelength or Changes in Color in Absorption/Emission

Potential Cause: Solvatochromism due to changes in the local chemical environment around the analyte. Solutions:

- Control Solvent Polarity: Ensure the solvent composition is consistent and appropriate. Be aware that impurities, such as trace water in organic solvents, can induce significant solvatochromic shifts [30].

- Utilize Solvatochromism as a Tool: In sensor design, solvatochromic dyes can be leveraged to detect specific solvents or water content qualitatively and quantitatively [30]. The observed color change can be the basis of the analytical signal.

- Optimize Chromatography: In LC-based methods, adjust the chromatographic conditions (e.g., mobile phase gradient, column temperature) to better separate the analyte from matrix components that may be causing the local environmental shift [27].

Problem 3: General Signal Instability or Inaccuracy in Complex Matrices

Potential Cause: Combined and variable matrix effects. Solutions:

- Use Internal Standardization: The internal standard method is one of the most potent ways to mitigate matrix effects [3]. A known amount of a compound (ideally a stable isotope-labeled version of the analyte) is added to every sample. By monitoring the ratio of the analyte signal to the internal standard signal, variations caused by the matrix can be corrected.

- Change Ionization Sources (for MS): In mass spectrometry, matrix effects are often tied to the ionization process (e.g., electrospray ionization). Switching to an alternative ionization source (e.g., APCI) that is less prone to these effects can be a viable solution [27].

- Implement Effective Clean-up: As emphasized in a 2023 review, a multifaceted approach combining improved sample preparation, optimized chromatography, and corrective calibration methods is the most promising avenue for resolving matrix effects in complex samples [27].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of Fluorescence Tracers

The following table summarizes key experimental data from a study that successfully mitigated compound interference by switching fluorescent tracers.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fluorescence Polarization Tracers for Kinase Assays [31]

| Tracer Type | Excitation/Emission Wavelength | Key Advantage | Demonstrated Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein-based | Shorter wavelength (e.g., ~495/520 nm) | Traditional standard | Susceptible to interference from autofluorescent compounds and scattered light. |

| Far-Red Tracer (PanVera PolarScreen) | Longer wavelength (Far-Red) | Reduced compound interference | Substantially less interference from library compounds and light scatter than fluorescein. |

| Cy5-based | Longer wavelength (Far-Red) | Popular far-red option | Produced a smaller assay window than the proprietary far-red tracer. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Assessing Quenching with EEM-PARAFAC

This protocol is adapted from studies using fluorescence quenching to diagnose matrix composition in water samples [32].

Objective: To detect changes in the chemical composition underlying a fluorescent signal using an extrinsic quencher.

Materials:

- Fluorescence spectrometer capable of measuring Excitation-Emission Matrices (EEMs).

- Potassium Iodide (KI), purified, as the extrinsic quencher.

- Sample vials and pipettes.

- Software for EEM preprocessing and PARAFAC analysis (e.g., Python package

eempy).

Procedure:

- EEM Measurement (Original): Measure the EEM of the original, unaltered sample. This signal is designated as

F_original. - Quencher Addition: Add a specific, non-fluorescent concentration of KI to the sample. KI is ideal as it has negligible absorbance and does not introduce new fluorescence [32].

- EEM Measurement (Quenched): Measure the EEM of the sample after KI addition. This signal is designated as

F_quenched. - PARAFAC Modeling: Process both the original and quenched EEMs together using a PARAFAC model to decompose the data into underlying fluorescent components.

- Calculate Apparent Quenching Ratio: For each PARAFAC component, calculate the apparent

F0/Fratio using the formula:Apparent F0/F = F_max,original / F_max,quenchedwhereF_maxis the maximum intensity of the PARAFAC component [32].

- Interpretation: A shift in the apparent

F0/Fvalue indicates a change in the composition of fluorophores within that PARAFAC component, which can be used to diagnose matrix-related prediction inaccuracies.

Key Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Matrix Effects in LC-MS

This standard protocol helps visualize ion suppression/enhancement in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) methods [3].

Objective: To identify regions of the chromatogram where co-eluting matrix components suppress or enhance the ionization of the analyte.

Materials:

- LC-MS system with an infusion tee located between the column outlet and the MS inlet.

- A syringe pump for continuous infusion.

- A dilute solution of the target analyte in a suitable solvent.

Procedure:

- Set Up Infusion: Connect the syringe pump containing the analyte solution to the infusion tee. Start a continuous, low-flow infusion of the analyte so that a steady signal is observed at the MS detector.

- Inject Matrix: Inject a blank or representative sample extract onto the LC column and run the chromatographic method as usual.

- Monitor Signal: Observe the MS signal of the infused analyte throughout the chromatographic run.

- Interpretation: In an ideal scenario, the analyte signal remains constant. A dip in the signal indicates a region where co-eluting matrix components are causing ion suppression. A spike in the signal would indicate ion enhancement [3].

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Fluorescence Quenching Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of fluorescence quenching by matrix components, a key source of signal suppression.

Matrix Effect Troubleshooting Workflow

This workflow provides a logical sequence of steps for diagnosing and addressing matrix effects in analytical methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Mitigating Matrix Effects

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Far-Red Fluorescent Tracers (e.g., PanVera PolarScreen) | Reduces interference from autofluorescent compounds and scattered light in fluorescence-based assays [31]. | Provides a larger assay window and less interference than common dyes like Cy5 or fluorescein. |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Used as an extrinsic, non-fluorescent quencher in fluorescence quenching studies to diagnose matrix composition [32]. | Chosen for its negligible absorbance in measured ranges and low toxicity, making it practical for routine use. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (e.g., ¹³C-labeled analyte) | Corrects for variable matrix effects in mass spectrometry by normalizing the analyte response [3]. | Must be an almost identical analog of the analyte that co-elutes and responds to sample preparation similarly. |

| High-Purity Acids & Solvents | Used in sample preparation and dilution to minimize the introduction of contaminants that cause background interference [33]. | Always check the certificate of analysis for elemental contamination levels; use LC-MS or ICP-MS grade where possible. |

| Solvatochromic Dyes (e.g., Reichardt's dye) | Act as molecular sensors to probe solvent polarity and detect impurities like water in organic solvents [29] [30]. | The observed color change provides a simple, visual indicator of the chemical environment. |

Practical Strategies: From Sample Preparation to Analysis for Minimizing Interference

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Strong Matrix Effects in LC-MS/MS Analysis

Problem: Strong signal suppression or enhancement during the analysis of trace organic contaminants in complex matrices like sediments, leading to inaccurate quantification.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low analyte recovery or high internal standard variation during validation [34] | High organic matter content in the sample [34] | - Employ two successive PLE extractions: first with methanol, then with a methanol-water mixture [34].- Optimize the use of internal standards to correct for matrix effects [34]. | - Characterize the organic matter content of your sample matrix beforehand. |

| Consistent signal suppression/enhancement correlated with analyte retention [34] | Co-eluting matrix components interfering with ionization [34] | - Use matrix-matched calibration standards.- Apply post-column infusion to visualize matrix effects throughout the chromatogram.- Implement effective sample clean-up using dispersive μ-SPE [35]. | - Use a chromatographic method with better separation. |

| High background noise or poor detection limits in trace analysis [36] | Contamination from labware, reagents, or environment [36] | - Use high-purity plastic labware (e.g., PP, LDPE) instead of glass [36].- Soak new vials and tubes in dilute acid (e.g., 0.1% HNO₃) or UPW to remove contaminants [36].- Work in a controlled, low-particulate environment if possible [36]. | - Establish a dedicated, clean workspace for trace analysis. Use high-purity reagents. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low Extraction Recovery in Dispersive μ-SPE

Problem: Inefficient extraction of target analytes leading to low recovery rates and poor method sensitivity.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low recovery for a wide range of analytes | Inefficient dispersion of the sorbent in the sample solution [37] | - Improve dispersion by using vortex mixing or sonication during the extraction step [37].- Ensure the sorbent material is finely ground and well-dispersed. | - Select a sorbent with appropriate particle size and surface properties for your sample. |

| Low recovery for specific analytes only | Unsuitable sorbent-analyte chemistry (e.g., polarity, functional groups) | - Screen different sorbent materials (e.g., C18, MCX, PSA) for your specific application [35].- Consider using a mixed-mode sorbent for a broader range of analytes [35]. | - Conduct a literature review for sorbents used successfully for similar analytes. |

| Poor reproducibility (high RSD) | Inconsistent sorbent separation after extraction [37] | - Ensure a reliable and consistent method for sorbent separation, such as centrifugation or filtration [37].- Automate the μSPE process to eliminate manual variability [35]. | - Use an automated platform like the PAL System for superior precision and traceability [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between traditional Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) and dispersive μ-SPE?

Traditional SPE is an exhaustive extraction method where the sample is passed through a packed sorbent bed in a cartridge. Almost all the analyte is transferred from the sample to the sorbent, requiring multiple partition equilibriums. In contrast, dispersive μ-SPE is a non-exhaustive extraction method where a small amount of sorbent is directly dispersed into the sample solution. This maximizes the contact surface area between the sorbent and the analytes, significantly speeding up the extraction process and reducing solvent consumption [37].

Q2: Why are my matrix effects highly correlated with the retention time of my analytes?

Matrix effects in techniques like LC-MS/MS are primarily caused by co-eluting matrix components that alter ionization efficiency in the source. In complex samples, these interfering compounds often exhibit a chromatographic pattern. Research has shown a strong and significant negative correlation (e.g., r = -0.9146) between matrix effect and retention time, meaning early-eluting compounds generally suffer from stronger signal suppression. This is because highly polar matrix components, which are often abundant, tend to elute early and cause more pronounced interference [34].

Q3: What is the most effective way to correct for matrix effects in quantitative analysis?

While several methods exist, the use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) is widely considered the most effective technique. Because a SIL-IS is chemically identical to the analyte but with a different mass, it experiences nearly identical matrix effects, extraction efficiency variations, and instrument fluctuations. Using these standards for correction provides the best results without compromising the method's sensitivity. This approach has been validated as superior for analyzing trace organic contaminants in challenging matrices like sediments [34].

Q4: How does automated μ-SPE improve upon the manual QuEChERS d-SPE cleanup?

Automated μ-SPE addresses several bottlenecks of the manual dispersive-SPE (d-SPE) step in QuEChERS:

- Superior Cleanup: The packed μ-SPE cartridge bed provides a more efficient and selective cleanup compared to loose d-SPE sorbent powder, leading to cleaner extracts and less instrument downtime.

- Full Automation: Systems like the PAL RTC can condition the cartridge, load the sample, and elute the cleaned extract unattended, in as little as 8 minutes per sample, increasing throughput.

- Enhanced Precision & Green Chemistry: Automation eliminates manual variability and digitally logs every step. The miniaturized format also drastically reduces solvent and sorbent consumption [35].

Q5: What are the critical steps to control contamination for ultratrace analysis?

For ultratrace analysis, controlling contamination is paramount. Key steps include [36]:

- Labware: Use clear plasticware (PP, LDPE, PFA) instead of glass. Pre-clean all new labware by soaking in dilute acid or UPW.

- Reagents: Use high-purity acids and 18 MΩ.cm deionized water. Decant small volumes of acid from the bottle to avoid contaminating the stock.

- Environment: Minimize particulate sources (e.g., printers, dusty shoes). Use laminar flow hoods (HEPA-filtered) for sample and standard preparation.

- Practices: Use powder-free nitrile gloves and establish dedicated, clean workspaces for specific tasks.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Analysis of Trace Organic Contaminants in Sediments

This protocol is adapted from a validated method for determining pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, and additives in lake sediments [34].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Freeze-dry and homogenize the sediment sample.

- Mix the sediment with a diatomaceous earth dispersant to improve extraction efficiency.

2. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE):

- Perform two successive extractions in the PLE system.

- First Extraction: Use methanol as the solvent.

- Second Extraction: Use a methanol-water mixture as the solvent.

- Combine the extracts.

3. Extract Clean-up & Pre-concentration (via Dispersive μ-SPE principles):

- The combined extract is purified and pre-concentrated using Solid Phase Extraction (SPE).

- The choice of SPE sorbent should be optimized for the target analytes and matrix.

4. Analysis:

- Analyze the cleaned extract using Liquid Chromatography coupled to a triple quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (LC-QqQMS).

- Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards to correct for matrix effects and ensure quantitative accuracy.

5. Method Validation:

- Validate the method by assessing linearity (R² > 0.990), recovery (>60% for most compounds), trueness (bias < ±15%), and precision (RSD < 20%) [34].

Protocol 2: Automated μSPE Clean-up for QuEChERS Extracts

This protocol outlines the automated cleanup of raw QuEChERS extracts, transforming a manual d-SPE step into a faster, more robust process [35].

1. System Setup:

- Use an automated liquid handling system (e.g., PAL System) equipped for μSPE.

- Prime the system with the required solvents.

2. Cartridge Conditioning:

- The system automatically conditions the μSPE cartridge with a suitable solvent to activate the sorbent.

3. Sample Loading:

- The raw sample extract is loaded onto the conditioned μSPE cartridge.

- The target analytes are retained on the sorbent while matrix interferents are either retained or washed through.

4. Washing (Optional):

- A wash step with a weak solvent may be applied to remove additional matrix components without eluting the analytes.

5. Elution:

- The target analytes are eluted from the μSPE cartridge using a small volume of a strong solvent.

- The system collects the cleaned eluent, which is now ready for direct injection into LC-MS or GC-MS.

- The entire process, from conditioning to elution, can be completed in approximately 8 minutes per sample [35].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and troubleshooting a sample preparation method focused on matrix clean-up.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and reagents essential for implementing the featured sample preparation techniques.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diatomaceous Earth | Optimal dispersant for Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) of solid samples like sediments. Improves solvent contact and extraction efficiency [34]. | Helps prevent sample agglomeration in the PLE cell, leading to more uniform and efficient extraction. |

| Mixed-mode µSPE Sorbents (e.g., MCX, C18) | Used in automated µSPE for selective clean-up or class fractionation (e.g., separating neutral lipids, fatty acids, phospholipids) [35]. | The choice of sorbent (C18 for reversed-phase, MCX for mixed-mode cation exchange) dictates selectivity for target analytes. |

| High-Purity Plastic Labware (PP, LDPE, PFA) | Sample vials, centrifuge tubes, and containers for trace analysis. Essential for minimizing elemental background contamination [36]. | Must be used instead of glass. Should be pre-cleaned by soaking in dilute acid or ultrapure water before use. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | The most efficient method for correcting matrix effects during LC-MS/MS analysis without sacrificing sensitivity [34]. | Should be added to the sample as early as possible in the preparation process to account for all losses and variations. |

| Dispersive µSPE Sorbents (General) | The core material for DSPME/D-µSPE. Directly dispersed into the sample solution to extract, clean up, and preconcentrate analytes [37]. | Selection is critical; depends on analyte properties (polarity, charge). Includes materials like primary secondary amine (PSA), C18, and graphitized carbon black (GCB). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides practical solutions for researchers facing challenges in extracting trace-level contaminants from complex sludge and sediment matrices. The following guides address common experimental issues within the broader context of overcoming matrix interference in environmental analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide for Extraction and Analysis

| PROBLEM | CAUSE | SOLUTION |

|---|---|---|

| Low Analytical Recovery | Time-dependent dissolution of specific nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, CuO) during extraction [38]. | Analyze extracts immediately after preparation. For spiked Ag and CuO NPs, immediate analysis is critical to prevent dissolution [38]. |

| High Matrix Interference | Co-extraction of non-target matrix components (e.g., sulfates, organic matter) that interfere with detection [39] [40]. | Implement a cleanup step. Use a Ba column to remove sulfate interference [40] or employ functionalized magnetic adsorbents like Fe3O4@SiO2-PSA for selective purification [41]. |

| Poor Extraction Efficiency | Inefficient release of target analytes from the complex sludge/sediment matrix [38] [42]. | Optimize the extraction solution. For metallic nanoparticles, 2.5 mM Tetrasodium Pyrophosphate (TSPP) is highly effective. For organic pollutants, a mixture of Acetonitrile and MTBE (1:1) shows high recovery [38] [39]. |

| Particle Aggregation or Transformation | Harsh extraction conditions that alter the native state of nanomaterials [38]. | Use milder extractants. Compare aggressive agents (e.g., TMAH) with gentler ones (e.g., TSPP or milli-Q water) to find the optimal balance between recovery and particle integrity [38]. |

| Carryover of Inhibitors | Incomplete removal of salts or humic substances that inhibit downstream analysis [43]. | Employ thorough washing steps during purification. Ensure wash buffers are completely removed before the final elution step [43]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most versatile and efficient extraction technique for a wide range of emerging pollutants in sewage sludge? Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) is widely considered the most preferable option, as it can effectively extract a broad spectrum of compounds without requiring expensive specialized equipment [42]. For higher throughput and automation, Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE/ASE) is an excellent alternative, offering reduced solvent usage and processing time [42] [39].

Q2: How can I quickly remove matrix interference without a lengthy cleanup procedure? Innovative materials like Fe3O4@SiO2-PSA nanoparticles for Magnetic Dispersive Solid-Phase Extraction (MDSPE) offer a rapid solution. These particles can be easily separated using a magnet, eliminating the need for centrifugation or filtration and significantly speeding up the cleanup process [41].

Q3: My target analyte is at a trace level, and the sample has a high sulfate background. How can I achieve accurate quantification? High sulfate concentrations can cause peak drift and reduced signal response [40]. Two effective methods are:

- Matrix Elimination: Use an in-line Ba column to chemically remove sulfate before the analytes reach the detector [40].

- Hyphenated Techniques: Couple ion chromatography with Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (IC-ICP-MS). The mass spectrometer's detector is highly resistant to this type of chemical interference [40].

Q4: What is a critical but often overlooked factor in sample preparation for sludge analysis? Sample pre-treatment and storage are critical. Improper handling can lead to complete analyte degradation or loss. For sludge, the most common and reliable method is to freeze-dry (lyophilize) the sample immediately after collection, followed by homogenization through grinding and sieving. This process preserves analyte integrity and ensures a representative, homogeneous sample [42].

Summarized Data from Key Studies

Table 1: Comparison of Extraction Methods for Environmental Matrices

| Method | Key Application | Optimal Conditions / Reagents | Performance Metrics | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrasodium Pyrophosphate (TSPP) Extraction [38] | Metallic Nanoparticles (Ag, Au, Ce, Cu, Pb, Ti, Zn) in sludge | 2.5 mM TSPP, 1:100 sludge-to-reagent ratio | >75% particle number recovery, >84.5% mass recovery [38] | High recovery while minimizing particle transformation |

| Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) [39] | Fluorinated alternatives in soil & sediment | ACN:MTBE (1:1) as extractant | Recovery: 85.4%-95.5%; LOD: 0.14–0.80 ng/g [39] | Rapid, automated, reduces solvent use and processing time |

| Magnetic Dispersive SPE (MDSPE) [41] | Diazepam in aquatic products | Fe3O4@SiO2-PSA as adsorbent | Recovery: 74.9–109%; LOD: 0.20 μg/kg [41] | Fast cleanup, eliminates need for centrifugation |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) [42] | Broad-range Emerging Pollutants in sludge | Various solvents, depending on target analytes | High versatility for multiple compound classes [42] | No specialized equipment needed, highly adaptable |

Table 2: Method Performance for Trace-Level Contaminant Detection

| Analytical Method | Target Contaminant | Matrix | LOQ | Recovery % | RSD % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sp-ICP-MS with TSPP Extraction [38] | Metallic Nanoparticles (e.g., Zn, Ag) | Sewage Sludge | Particle conc. 1×10⁷–3×10¹⁰ particles/g [38] | >75% (particle number) [38] | Information missing |

| UPLC-MS/MS with MDSPE [41] | Diazepam | Complex aquatic products | 0.50 μg/kg | 74.9–109 | 1.24–11.6 |

| IC-ICP-MS [40] | Bromate | High-sulfate mineral water | < 10.0 μg/L | 95.9–97.7 | 0.31–0.48 |

| ASE with UPLC-MS/MS [39] | Fluorinated Alternatives | Soil & Sediment | 0.56 to 0.80 ng/g | 85.4–95.5 | < 10 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol uses single-particle ICP-MS (sp-ICP-MS) for high-throughput quantification and size characterization of seven environmentally relevant metallic nanoparticles (MNPs): Ag, Au, Ce, Cu, Pb, Ti, and Zn.

Key Reagents:

- Tetrasodium pyrophosphate (TSPP), 2.5 mM solution

- Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) solution, for comparison

- Milli-Q water

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Air-dry collected sewage sludge and sieve it through a 2-mm mesh.

- Extraction: Weigh the sludge and add the 2.5 mM TSPP solution at a 1:100 sludge-to-reagent ratio.

- Extraction Process: Agitate the mixture to ensure complete mixing and efficient release of MNPs from the solid matrix.

- Analysis: Immediately analyze the extract using sp-ICP-MS. Use short dwell times (50–100 μs) to capture transient nanoparticle signals and distinguish them from dissolved analyte background.

Note: Immediate analysis is critical for accurate quantification of certain MNPs like Ag and CuO, which can undergo time-dependent dissolution in the extractant [38].

This method utilizes Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) for a fast, efficient, and automated pretreatment, eliminating the need for a separate cleanup step.

Key Reagents:

- Extractant: Acetonitrile and Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) mixture (1:1 v/v)

- Purified siliceous earth

- Glass fiber filter membranes

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Freeze-dry, homogenize, and sieve soil/sediment samples.

- ASE Setup: Place the sample in the ASE cell lined with a glass fiber filter and mixed with purified siliceous earth.

- Extraction: Load the ACN:MTBE (1:1) solvent and run the ASE under high temperature and pressure according to the manufacturer's settings. The entire extraction process is completed in approximately 23 minutes per sample.

- Post-Extraction: Collect the extract and filter it through a membrane (e.g., 0.22 μm) before direct analysis by UHPLC-MS/MS.

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Extraction and Analysis | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrasodium Pyrophosphate (TSPP) [38] | Chelates metal cations and promotes electrostatic dispersion, releasing nanoparticles from organic-mineral aggregates in sludge. | Optimal extractant for Metallic Nanoparticles (Ag, Ti, Zn) in sewage sludge. |

| Fe3O4@SiO2-PSA Nanoparticles [41] | Magnetic adsorbent for dispersive solid-phase extraction; removes matrix interferents (proteins, lipids) via easy magnetic separation. | Cleanup of complex aquatic product extracts for diazepam analysis by UPLC-MS/MS. |

| Ba Cartridge/Column [40] | Selectively removes sulfate ions from the sample matrix, preventing peak drift and signal suppression in chromatography. | Pre-treatment of high-sulfate karst water for trace-level bromate analysis by IC. |

| ACN:MTBE (1:1) Mixture [39] | Effective solvent mixture for Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE); provides high recovery while reducing co-extraction of polar impurities. | Extraction of fluorinated alternatives from soils and sediments. |

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic-Balanced (HLB) SPE [42] | A widely used solid-phase extraction sorbent for retaining a broad range of emerging organic pollutants from aqueous and extract solutions. | General-purpose cleanup and concentration of diverse emerging pollutants in sludge extracts. |

Troubleshooting Guides

This guide provides targeted troubleshooting for UHPLC-MS/MS and HS-GC-FID systems used in trace-level contaminant analysis, where matrix effects are a primary concern.

UHPLC-MS/MS Troubleshooting

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Tailing Peaks [44] [45] | Column void due to poorly installed fittings or improper tubing cut [44]. | Check and re-make connections before the column; ensure tubing is properly cut [44]. |

| Contaminated or old guard cartridge/column [45]. | Replace guard cartridge; wash or replace the column [45]. | |

| Injection solvent stronger than mobile phase [45]. | Ensure injection solvent is same or weaker strength than the mobile phase [45]. | |

| Varying Retention Times [44] [45] | Pump not mixing solvents properly (aqueous for decreasing RT, organic for increasing RT) [44] [45]. | Purge pump, clean check valves, replace consumables, check for leaks [44]. |

| Temperature fluctuations [45]. | Use a thermostatically controlled column oven [45]. | |

| System not fully equilibrated [45]. | Equilibrate the column with 10 volumes of mobile phase [45]. | |

| Signal Suppression (or Enhancement) [3] | Ionization suppression/enhancement from co-eluting matrix components [3]. | Improve sample cleanup; use internal standard (e.g., stable isotope-labeled analog) for quantitation [3]. |

| Extra Peaks [44] [45] | Late-eluting peak from a previous injection [44]. | Adjust method to ensure all peaks elute; optimize needle rinse settings [44]. |

| Contaminated solvents or column [45]. | Use fresh HPLC-grade solvents; wash or replace the column [45]. | |

| Jagged or Noisy Baseline [44] [46] | Dissolved air in mobile phase or insufficient mixing [44]. | Degas mobile phase; ensure proper mixing [44]. |

| Contaminated gas supplies (for MS vacuum system) or detector [46]. | Confirm gas purity; clean FID jet and collector [46]. |

HS-GC-FID Troubleshooting

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background or Noise [46] | Contaminated FID jet or collector [46]. | Clean or replace the FID jet; clean the collector and PTFE insulators [46]. |

| Contaminated gas supplies (H₂, Air, Makeup) [46]. | Check gas purity; install or replace gas traps in supply lines [46]. | |

| Gas flows incorrect [46]. | Measure H₂, Air, and makeup flows independently; ensure they are within ±10% of setpoint [46]. | |

| FID Will Not Ignite [46] | FID temperature set too low [46]. | Ensure detector temp is at least 20°C higher than the highest oven temperature [46]. |

| Incorrect gas flows (H₂ or Air) [46]. | Verify and adjust H₂ and Air flow rates [46]. | |

| Peak Tailing (GC) | Inactive liner or column. | Re-place or re-condition the liner; cut a small section from the column inlet or replace the column. |

| Cycling Baseline [46] | Defective gas compressor or tank regulator [46]. | Check house air compressor system or gas regulator [46]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a "matrix effect" in UHPLC-MS/MS, and how can I identify it?

A matrix effect occurs when components in the sample (other than your analyte) alter the detector's response to your analyte, most commonly causing ionization suppression or enhancement in MS detection [3]. You can identify it using a post-column infusion experiment: continuously infuse your analyte into the MS while injecting a blank, matrix-containing sample. A steady signal indicates no effect; a dip or rise in the baseline at specific retention times indicates suppression or enhancement from co-eluting matrix components [3].

2. What are the most effective strategies to mitigate matrix effects in quantitative UHPLC-MS/MS analysis?

Several strategies can be employed [3]:

- Internal Standardization: Using a stable isotope-labeled internal standard is highly effective, as it co-elutes with the analyte and experiences nearly identical matrix effects, correcting for them [3].

- Improved Sample Cleanup: Techniques like solid-phase extraction can remove interfering matrix components before injection.

- Chromatographic Optimization: Adjusting the gradient to shift the analyte's retention away from the region where matrix components elute can separate the analyte from interferents.

3. My FID baseline is noisy and the background is high. What is the first thing I should check?

First, confirm the integrity and purity of your gas supplies (Hydrogen, Air, and Makeup gas) and perform a thorough leak check on all gas lines [46]. Contaminated gases are a common source of high background and noise.

4. How do I know if my UHPLC-MS/MS peak shape issues are due to the instrument or the column?

A good diagnostic step is to examine all peaks in the chromatogram. If all peaks are showing tailing or broadening, the issue is likely systemic, such as a void volume from a poor connection before the column [44] or excessive extra-column volume [45]. If only one peak is affected, the issue is more likely related to the method or a specific chemical interaction with the column [44].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Matrix Effects via Post-Column Infusion

Purpose: To visually identify regions of ionization suppression or enhancement in an LC-MS/MS method [3].

Materials:

- LC-MS/MS system

- Analytical column

- Syringe pump

- 3-port T-union

- Analyte standard solution

- Processed blank matrix sample

Method:

- Setup: Connect the effluent from the LC column to one port of the T-union. Connect the syringe pump, loaded with a dilute solution of your analyte, to the second port. Connect the outlet of the union to the MS ion source.

- Infusion: Start the LC gradient (as per your method) and begin infusing the analyte at a constant rate to establish a stable baseline signal.

- Injection: Inject the processed blank matrix sample.

- Data Analysis: Observe the analyte signal across the chromatographic run time. A constant signal indicates no matrix effect. A depression in the signal indicates ionization suppression; an elevation indicates enhancement [3].

Visual Workflow:

Protocol 2: Systematic Troubleshooting of FID High Background

Purpose: To logically isolate and resolve the cause of an excessively high or noisy baseline in an HS-GC-FID system [46].

Materials:

- GC system with FID

- Leak checker

- Electronic bubble meter (or soap film flow meter)

- Appropriate wrenches and cleaning tools

- Spare FID jet and PTFE insulators

Method:

- Leak Check: Cool the FID to <50°C. Check all gas lines and fittings for leaks.

- Measure Flows: Disconnect the column from the FID and cap the inlet. Use a flow meter to independently measure H₂, Air, and Makeup gas flows. Compare to manufacturer setpoints (e.g., H₂ ~30-40 mL/min, Air ~400 mL/min) [46].

- Clean FID: If flows are correct, clean the FID jet and collector assembly according to the manufacturer's instructions. Inspect the PTFE insulators for damage and the interconnect spring for deformation or contamination [46].

- Bake Out: Reassemble the FID and perform a bake-out at 350°C for one hour with gases flowing [46].

- Check Electronics: If the problem persists, the issue may be electronic (e.g., faulty interconnect or board). Contact technical support [46].

Logical Troubleshooting Pathway:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to every sample to correct for matrix-induced ionization effects and losses during sample preparation, ensuring quantitative accuracy in MS [3]. |

| HPLC/Grade Solvents | High-purity mobile phase components are critical to minimize background noise, prevent system contamination, and ensure reproducible chromatography [45]. |

| Guard Cartridge | A short, disposable column placed before the main analytical column to trap particulate matter and chemical contaminants, extending the analytical column's life [45]. |

| Gas Traps & Filters | Moisture and hydrocarbon traps installed in carrier and detector gas lines protect the GC column and FID from contamination, reducing baseline noise and drift [46]. |

| Blanking Plug / No-Hole Ferrule | Used to cap the FID inlet when the column is removed during troubleshooting, isolating the detector to diagnose background problems [46]. |

In analytical method development, especially for the trace-level detection of contaminants, achieving high extraction efficiency is critical. Traditional optimization using a one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach, where a single variable is altered while others remain constant, is inefficient and can lead to misinterpretations. This is because it ignores the complex interactions between factors that can significantly impact the final result [47]. Multivariate optimization through Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a systematic, statistically sound framework to overcome these limitations. It allows researchers to efficiently identify significant factors, understand their interactions, and locate true optimal conditions with fewer experimental trials, making it particularly valuable for complex sample preparations like those required for challenging matrices in contaminant analysis [47] [48].

When analyzing for trace organic contaminants (TrOCs) in complex samples such as sediments or food, matrix interference is a major hurdle. Matrix components can suppress or enhance analyte signals, leading to inaccurate quantification [34] [49]. A robustly optimized extraction method, developed using DoE, is the first line of defense against such interference, ensuring that the target analytes are efficiently and selectively isolated from the matrix.

Core DoE Concepts and Terminology

- Factor: An independent variable that is deliberately varied during an experiment to study its impact on the response (e.g., extraction temperature, solvent pH, purge volume) [48].

- Level: The specific value or setting at which a factor is tested (e.g., temperatures of 40°C, 60°C, and 80°C).

- Response: The measured output or outcome of an experiment that is dependent on the factor levels (e.g., extraction yield, total peak area, recovery percentage) [50] [48].

- Interaction: When the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor. Capturing these interactions is a key advantage of DoE over OFAT [47].

- Screening Design: Used in the initial phase to identify which factors, from a potentially large list, have a significant effect on the response. Examples include full factorial (FFD) and fractional factorial designs [47].