Performance Validation of Catalytic Remediation: From Novel Mechanisms to AI-Driven Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of performance validation strategies for advanced catalytic remediation technologies.

Performance Validation of Catalytic Remediation: From Novel Mechanisms to AI-Driven Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of performance validation strategies for advanced catalytic remediation technologies. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of emerging methods like contact-electro-catalysis and advanced oxidation processes, examines novel catalyst designs including single-atom and core-shell nanostructures, and investigates AI-driven optimization for complex environmental matrices. The review systematically compares catalytic efficiency, operational parameters, and sustainability metrics across technologies, offering researchers and drug development professionals validated frameworks for selecting and optimizing remediation strategies for pharmaceutical contaminants and industrial pollutants.

Fundamental Principles and Emerging Mechanisms in Catalytic Remediation

Contact-electro-catalysis (CEC) represents a paradigm-shifting approach in catalytic science that utilizes electron transfer during contact electrification to drive chemical reactions. This innovative mechanism stands at the frontier of mechanochemistry, contact electrification, and catalysis, enabling the direct conversion of ubiquitous mechanical energy into chemical energy without reliance on conventional energy inputs such as light or electricity [1] [2]. Unlike traditional catalytic methods that require specific material properties like photosensitivity or electrical conductivity, CEC takes advantage of the universal phenomenon of contact electrification, which occurs when materials with different electron affinities come into contact and separate [3]. This fundamental characteristic allows nearly all organic and inorganic materials to potentially serve as CEC catalysts, dramatically expanding the toolbox available for catalytic process design [2].

The core principle of CEC involves harnessing electrons exchanged during the contact-separation cycles between materials—typically at solid-liquid interfaces—to initiate redox reactions [4]. When mechanical energy induces frequent contact-electrification cycles, electrons can be transferred to reactant molecules, forming reactive species that drive chemical transformations [3]. This mechanism provides a sustainable pathway for environmental remediation, chemical synthesis, and energy conversion by utilizing otherwise wasted mechanical energy from sources such as wind, water flow, or ultrasonic waves [1]. The emergence of CEC as a distinct catalytic strategy complements existing approaches like photocatalysis and electrocatalysis, offering unique advantages in terms of catalyst selection, energy sustainability, and operational conditions [1] [2].

Fundamental Mechanisms and Principles

Theoretical Foundation of CEC

The theoretical underpinnings of contact-electro-catalysis center on the electron transfer events that occur during contact electrification (CE) at material interfaces. When two materials with differing electron affinities undergo contact and separation, a charge transfer process takes place that can involve electrons, ions, or material species [2]. Research has demonstrated that electron transfer dominates this process at water-dielectric interfaces, providing the fundamental basis for CEC [3]. During mechano-stimulation—such as that provided by ultrasonic waves—frequent contact-separation cycles occur at the catalyst surface, driven by the growth and collapse of cavitation bubbles [3]. These cycles enable continuous electron exchange between the catalyst and reactant molecules in solution.

The CEC mechanism differs significantly from conventional electrocatalysis, as it does not require the formation of an electron flow cycle or external power source [5]. Instead, it utilizes electrons temporarily stored on the tribolayer or catalyst surface, generated through the contact charging process, to directly participate in catalytic reactions [5]. This direct electron engagement mechanism reduces energy losses associated with multiple conversion steps in traditional catalytic processes. When dielectric materials contact water, the resulting surface charge density can reach approximately 50 μC/m², providing sufficient electrochemical potential to drive chemical reactions [3]. These transferred electrons possess adequate energy to initiate the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (•O₂⁻), which subsequently participate in advanced oxidation processes for environmental remediation [3].

Quantitative Analysis of Electron Transfer

Recent research has enabled quantitative analysis of the electron transfer processes in CEC, providing insights into efficiency optimization. A groundbreaking study introduced an analytical method for investigating CE-to-CEC conversion at various temperatures and ultrasonic conditions, establishing a quantitative metric for evaluating CEC catalyst performance [4]. This approach quantifies the number of activated electrons produced during a single charge transfer cycle that effectively participate in catalytic reactions.

Under typical CEC conditions (40 kHz ultrasound frequency, 30°C), the CE-to-CEC conversion efficiency was determined to be approximately 0.0934% [4]. This efficiency can be modulated by adjusting external parameters: increasing the temperature from 30°C to 70°C enhances the conversion efficiency by 25.5%, while optimizing ultrasonic frequency from 40 kHz to 28 kHz boosts efficiency by 28.3% [4]. These findings provide crucial quantitative benchmarks for comparing CEC performance across different material systems and reaction conditions, enabling more rational design of CEC processes.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Contact-Electro-Catalysis

| Performance Parameter | Value | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CE-to-CEC Conversion Efficiency | 0.0934% | 40 kHz, 30°C | [4] |

| CO Faradaic Efficiency | 96.24% | CO₂ reduction from air using Cu-PCN@PVDF/quaternized CNF TENG | [5] |

| CO Production Rate | 33 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ | Ambient air with 99% RH | [5] |

| MO Degradation Efficiency | ~100% | 180 min ultrasonication with FEP powder | [3] |

| Electron Transfer Enhancement from Temperature Increase | 25.5% | 30°C to 70°C | [4] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

CEC Versus Conventional Catalytic Methods

Contact-electro-catalysis demonstrates distinct advantages and limitations when compared to traditional catalytic approaches such as photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and piezoelectric catalysis. Unlike photocatalysis that requires specific light conditions and semiconductor materials with appropriate bandgaps, CEC can proceed under ambient conditions using a much broader range of materials, including commercially available polymers [1]. Similarly, while electrocatalysis depends on external power supplies and conductive electrodes, CEC operates without wired electrical connections, making it suitable for remote or resource-limited applications [1] [2].

The catalytic efficiency of CEC is comparable and in some cases superior to other mechanochemical strategies, though it generally remains lower than established electrocatalysis or photocatalysis methods [1]. However, CEC's unique advantage lies in its ability to utilize wasted or ambient mechanical energy, providing a sustainable pathway for chemical reactions without additional energy investment [2]. For material selection, CEC substantially expands available options beyond the constraints of traditional catalysts. Whereas photocatalysis requires photosensitive semiconductors and electrocatalysis demands conductive materials, CEC can employ virtually any material capable of contact electrification, including common polymers like FEP, PTFE, Nylon-6,6, and rubber [3]. This flexibility enables the use of environmentally friendly, low-cost, and recyclable catalysts, reducing both economic and environmental burdens [1].

Application-Specific Performance Metrics

Organic Pollutant Degradation

CEC has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in degrading organic pollutants, representing one of its most extensively studied applications. In a seminal study, fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) powder achieved complete degradation of a 5-ppm methyl orange (MO) solution after 180 minutes of ultrasonication (40 kHz, 120 W) [3]. The degradation process followed pseudo-first-order kinetics, with the rate constant directly correlating with the material's contact electrification capability [3]. Comparative studies using various dielectric powders revealed that materials with higher electron affinity (FEP, PTFE, PVDF) consistently outperformed those with lower electron affinity (Nylon-6,6, rubber) in degradation efficiency [3]. This performance hierarchy aligns with the fundamental principle that electron transfer during contact electrification drives the catalytic process.

CO₂ Reduction Reaction (CO₂RR)

Perhaps the most impressive demonstration of CEC capability comes from its application in CO₂ reduction. A pioneering study reported a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) system comprising electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) loaded with single Cu atoms-anchored polymeric carbon nitride (Cu-PCN) as the electron-rich tribolayer and quaternized cellulose nanofibers (CNF) as the CO₂-adsorbing tribolayer [5]. This system achieved an exceptional CO Faradaic efficiency of 96.24% and a CO production rate of 33 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ from ambient air, surpassing previous air-based CO₂ reduction technologies [5]. The quaternized CNF exhibited strong CO₂ adsorption capacity even at low concentrations, while the single Cu atoms on Cu-PCN effectively enriched electrons during contact electrification, facilitating electron transfer to adsorbed CO₂ molecules [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Catalytic Methods for Environmental Remediation

| Catalytic Method | Typical Catalysts | Energy Input | Application Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact-Electro-Catalysis | FEP, PTFE, PVDF, Cu-PCN | Mechanical (ultrasound, stirring) | Organic dye degradation, CO₂ reduction, H₂O₂ production | Wide catalyst selection, utilizes ambient mechanical energy, works under mild conditions | Relatively lower efficiency compared to established methods |

| Photocatalysis | TiO₂, ZnO, g-C₃N₄ | Light (UV/visible) | Organic pollutant degradation, water splitting, CO₂ reduction | Utilizes solar energy, well-established research foundation | Limited to light conditions, recombination of electron-hole pairs |

| Electrocatalysis | Noble metals, conductive polymers | Electricity | HER, OER, CO₂RR, heavy metal removal | High efficiency, precise control | Requires external power, electrode fouling, high cost |

| Piezocatalysis | BaTiO₃, ZnO, PVDF | Mechanical vibration | Organic degradation, water splitting | Utilizes mechanical energy, no external power needed | Limited to piezoelectric materials |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard CEC Reactor Setup

A typical CEC experimental apparatus consists of an ultrasonication bath capable of operating at various frequencies (commonly 20-40 kHz) and power outputs (typically 100-150 W), a reaction vessel containing the catalyst suspension and reactant solution, and temperature control systems [4] [3]. For quantitative analysis of electron transfer, additional equipment for fluorescence spectroscopy (detecting •OH radicals) and spectrophotometry (measuring •O₂⁻ concentration) is employed [4]. The ultrasonication process generates cavitation bubbles that facilitate frequent contact-separation cycles between the catalyst particles and water molecules, driving the contact electrification process essential for CEC [3].

To monitor reaction progress, researchers typically collect aliquots at regular intervals and analyze them using UV-Vis spectroscopy to track the disappearance of characteristic absorption peaks of target compounds [3]. For more detailed product identification, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) provides comprehensive information on intermediate and final degradation products [3]. Additionally, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy with appropriate spin-trapping agents (e.g., DMPO for •OH and •O₂⁻) directly confirms the generation of reactive oxygen species during CEC processes [3].

Protocol for Organic Dye Degradation

The following protocol details a standardized approach for evaluating CEC performance in organic dye degradation, based on established methodologies [3]:

Catalyst Preparation: Select dielectric powders (e.g., FEP, PTFE, PVDF) with particle sizes typically ranging from 100-500 μm. Pre-treat materials by stirring in deionized water for 48 hours to ensure proper wetting and contact electrification capability.

Reaction Mixture: Add 20 mg of catalyst powder to 50 mL of organic dye solution (e.g., 5 ppm methyl orange) in a glass reaction vessel.

Mechanical Stimulation: Subject the suspension to ultrasonication at specified frequency (e.g., 40 kHz) and power (e.g., 120 W) for predetermined time intervals (typically 0-180 minutes).

Sampling and Analysis: Withdraw 2 mL aliquots at regular time intervals, separate catalyst particles via centrifugation or filtration, and analyze the supernatant using UV-Vis spectroscopy at the characteristic absorption wavelength of the dye (e.g., 464 nm for methyl orange).

Control Experiments: Conduct parallel control experiments without catalyst particles to account for potential direct sonolytic degradation.

Radical Detection: Confirm reactive oxygen species generation using EPR spectroscopy with appropriate spin-trapping agents or fluorescent probes.

Product Identification: Identify degradation intermediates and products using LC-MS to elucidate degradation pathways.

Catalyst Characterization: Examine catalyst materials before and after reaction using SEM, FTIR, XPS, and Raman spectroscopy to confirm stability and exclude physical adsorption effects.

Protocol for CO₂ Reduction from Ambient Air

The experimental setup for CEC-based CO₂ reduction involves a more specialized configuration centered on a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) system [5]:

Tribolayer Fabrication:

- Negative Tribolayer: Prepare electrospun PVDF fibers loaded with single Cu atoms-anchored polymeric carbon nitride (Cu-PCN) at an optimal mass ratio of 1:100 (catalyst:PVDF) to prevent agglomeration.

- Positive Tribolayer: Synthesize quaternized cellulose nanofibers (CNF) with strong CO₂ adsorption capacity and water molecule fixation ability.

TENG Assembly: Construct the triboelectric nanogenerator by arranging the positive and negative tribolayers with appropriate separation to allow periodic contact-separation motion.

Reaction Chamber Setup: Place the TENG in a controlled humidity chamber (99% relative humidity) to facilitate proton generation from water oxidation at the positive tribolayer.

CO₂ Reduction Operation: Expose the system to ambient air or controlled CO₂ streams while applying mechanical energy to drive contact-separation cycles in the TENG.

Product Analysis: Quantify gaseous products (CO, O₂) using gas chromatography with appropriate detectors. Determine Faradaic efficiency based on charge transfer measurements and product quantification.

Isotope Labeling: Conduct experiments with ¹³CO₂ to confirm the carbon source in reaction products through mass spectrometric analysis.

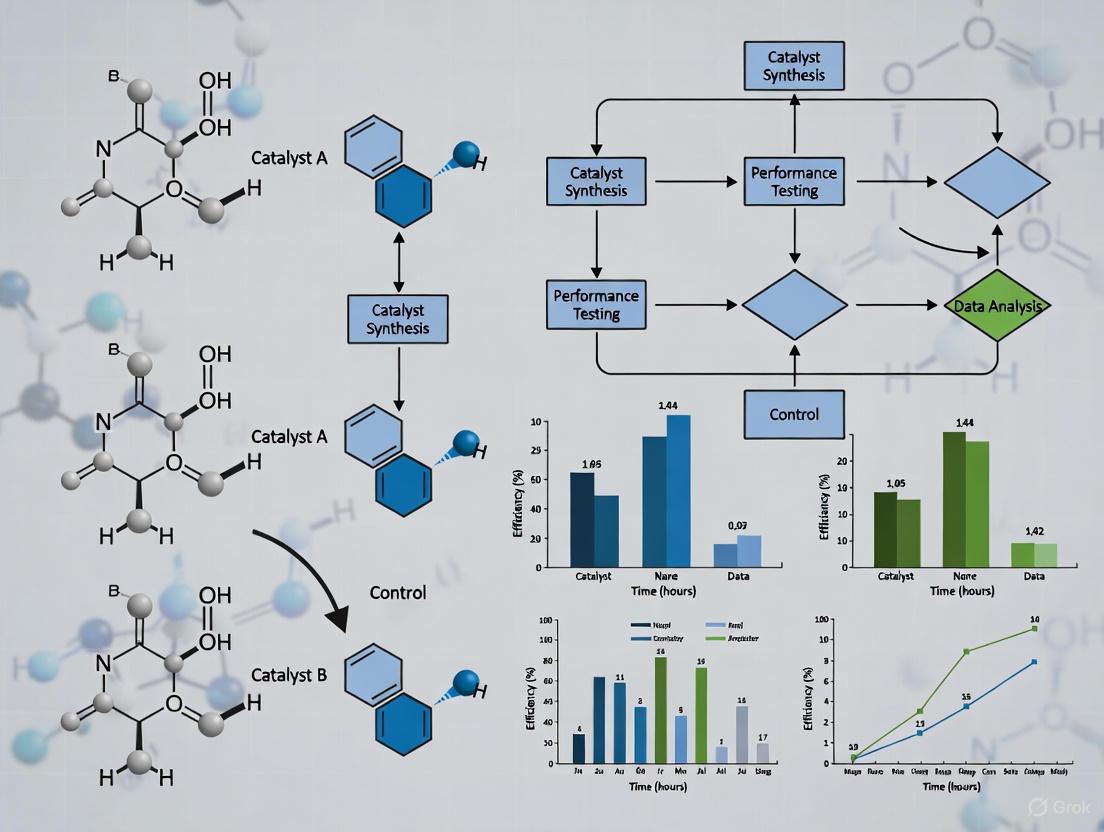

Diagram 1: CEC CO₂ Reduction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of CO₂ reduction via contact-electro-catalysis, highlighting the dual tribolayer system and key mechanistic steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of contact-electro-catalysis research requires specific materials and characterization tools. The following table summarizes essential components of the CEC researcher's toolkit, based on materials referenced in experimental studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CEC Investigations

| Material/Reagent | Function in CEC | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEP Powder | Primary catalyst for electron transfer | Organic dye degradation [3] | High electron affinity, chemical stability, reusable |

| PTFE Powder | Alternative catalyst material | Comparative degradation studies [3] | Excellent charge retention, hydrophobic |

| PVDF | Piezoelectric polymer matrix | Catalyst support in CO₂RR TENG [5] | Piezoelectric properties, fibrous structure |

| Cu-PCN | Single-atom catalyst | CO₂ reduction to CO [5] | Atomically dispersed Cu sites, electron enrichment capability |

| Quaternized CNF | CO₂ adsorption tribolayer | CO₂ capture and reduction [5] | Strong CO₂ adsorption, water fixation ability |

| Spin Trapping Agents | Radical detection in EPR | Confirmation of •OH and •O₂⁻ generation [3] | DMPO, TEMP for radical identification |

| Fluorescent Probes | ROS quantification | •OH radical detection [4] | High sensitivity, specific binding |

| Nitroblue Tetrazolium | Superoxide radical detection | Spectrophotometric analysis of •O₂⁻ [4] | Specific colorimetric reaction with •O₂⁻ |

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

Despite significant advances in contact-electro-catalysis, several challenges remain to be addressed before widespread practical implementation can be realized. The comparatively lower efficiency of CEC relative to established catalytic methods represents the primary limitation, with current CE-to-CEC conversion efficiencies remaining below 0.1% in most systems [4]. Enhancing this efficiency requires multifaceted strategies, including development of advanced materials with superior contact electrification capabilities, optimization of mechanical stimulation parameters, and engineering of reactor designs that maximize contact-separation frequency [1] [4].

Future research directions should prioritize quantitative understanding of the relationship between material properties and CEC performance, establishment of standardized evaluation protocols, and exploration of synergistic effects between CEC and other catalytic mechanisms [1] [4]. The integration of CEC with complementary approaches such as photocatalysis (creating "mechano-photocatalysis" systems) may unlock new efficiencies and applications [6]. Additionally, expanding CEC beyond its current applications in environmental remediation to include organic synthesis, energy conversion, and biomedical applications represents a promising frontier [1] [2].

From a fundamental perspective, developing more sophisticated in-situ characterization techniques to directly observe electron transfer during contact electrification will be crucial for elucidating detailed mechanisms [7]. Similarly, computational modeling and data-mining approaches adapted from electrocatalysis research could accelerate catalyst discovery and optimization [7]. As research in this emerging field continues to mature, contact-electro-catalysis holds exceptional promise for sustainable chemical transformation by harnessing ubiquitous mechanical energy sources.

Diagram 2: CEC Electron Transfer Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the fundamental process from mechanical stimulation to reactive species generation and practical applications in contact-electro-catalysis.

Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) represent a suite of chemical treatment technologies designed for the remediation of water and wastewater by degrading persistent organic pollutants through reaction with powerful, transient reactive species [8]. Their efficacy hinges on the in-situ generation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), most notably the hydroxyl radical (•OH), which non-selectively oxidizes a wide range of recalcitrant contaminants, from pharmaceuticals to industrial chemicals, into simpler, less harmful compounds, ultimately leading to mineralization to CO₂ and H₂O [9] [10] [8]. The exploration of AOP mechanisms, particularly the radical generation pathways and their subsequent interaction with pollutants, is fundamental to the performance validation of catalytic remediation methods, enabling the selection and optimization of processes for specific contamination scenarios.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Radical Generation

The core principle of AOPs is the efficient generation of ROS, which can be categorized into radical pathways (e.g., hydroxyl and sulfate radicals) and non-radical pathways (e.g., singlet oxygen, surface-activated complexes) [11]. The dominant reactive species and the pathway of its formation vary significantly with the specific AOP technology employed.

- Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) Pathways: The hydroxyl radical is one of the most potent oxidants (E° = 2.8 V) and is central to many AOPs [8]. In the classic Fenton reaction, •OH is generated from hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) in the presence of ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) under acidic conditions:

Fe²⁺ + H₂O₂ → Fe³⁺ + •OH + OH⁻[9] [8]. The Photo-Fenton process enhances this system by using light to regenerate Fe²⁺ from Fe³⁺, sustaining the catalytic cycle and increasing the radical yield:Fe(OH)²⁺ + hν → Fe²⁺ + •OH[9] [12]. In semiconductor photocatalysis (e.g., using TiO₂ or ZnO), photon energy equal to or greater than the bandgap of the catalyst excites an electron from the valence band to the conduction band, creating an electron-hole pair. The positive hole can then react with water or hydroxide ions to produce •OH [13] [8]. - Sulfate Radical (SO₄•⁻) Pathways: Persulfate-based AOPs generate sulfate radicals, which have a high redox potential (E° = 2.5-3.1 V) and are more selective than •OH, particularly towards compounds with electron-rich moieties [11] [12]. Persulfate (S₂O₈²⁻) can be activated by heat, UV light, or transition metals (e.g., Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺):

S₂O₈²⁻ + heat/UV/Fe²⁺ → SO₄•⁻[13] [11]. - Non-Radical Pathways: Some AOPs operate through non-radical mechanisms. For instance, in certain persulfate-activated systems, the reaction can proceed via singlet oxygen (¹O₂) or high-valent metal-oxo species (e.g., Cu³⁺) [11] [12]. These pathways are often less susceptible to scavenging by common water matrix constituents and may preferentially target specific functional groups [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of reactive species generation from different AOPs and their subsequent interaction with pollutants.

Experimental Protocols for AOP Performance Evaluation

Validating the performance of AOPs requires standardized experimental methodologies to ensure comparability and scalability. The following protocols are representative of rigorous AOP research.

Protocol for Photo-Fenton Treatment of Cosmetic Wastewater

A study evaluating AOPs for real cosmetic wastewater provides a robust experimental model [14] [15].

- Wastewater Source and Characteristics: Real, untreated wastewater was collected from a cosmetics factory in Badr City, Egypt. Its composition included stearic acid, cetyl alcohol, dimethyl phthalate, parabens, and dyes, with an initial COD of 1450 mg/L and a poor biodegradability index (BOD₅/COD) of 0.28 [14].

- Reactor Configuration: Batch experiments were conducted in a 1 L quartz cylinder reactor. Two high-pressure mercury lamps (TQ 75 W each, total UV power 150 W, primary emission at 254 nm) were mounted symmetrically around the reactor. A magnetic stirrer ensured complete mixing of reactants [14].

- Experimental Procedure: For each test, 1 L of wastewater was adjusted to the desired pH (optimized to 3) using sulfuric acid. Pre-determined doses of ferrous salt (FeSO₄·7H₂O, optimized to 0.75 g/L) and hydrogen peroxide (30%, optimized to 1 mL/L) were added. The reaction was initiated by switching on the UV lamps and stirrer. All experiments were conducted at ambient temperature (25 ± 2 °C). After the set irradiation time (optimized to 40 min), the reaction was quenched with sodium hydroxide to decompose residual H₂O₂ and raise the pH [14].

- Analytical Methods: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was measured using the closed reflux colorimetric method with a HANNA photometer. Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD₅) was determined via the standard 5-day incubation method. The biodegradability index was calculated as BOD₅/COD [14].

Protocol for Comparative Degradation of a Pharmaceutical

Research on the antidepressant maprotiline illustrates a protocol for comparing multiple AOPs and identifying transformation products [13].

- Target Pollutant: Aqueous solution of maprotiline at an initial concentration relevant to environmental detection (e.g., µg L⁻¹ range).

- AOP Systems Compared: The study evaluated (i) semiconductor photocatalysis using Fe-ZnO, Ce-ZnO, and TiO₂, and (ii) heterogeneous photo-Fenton with magnetite coated with humic acid (Fe₃O₄/HA) activating H₂O₂ and persulfate (S₂O₈²⁻) [13].

- Reaction Monitoring: Maprotiline removal was followed by Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC/HRMS). Pseudo-first-order kinetics were applied to model degradation:

C/C₀ = exp(-k × t), wherekis the rate constant [13]. - Transformation Product Identification: LC/HRMS data were processed using specialized software (SPIX) to identify statistically relevant ions corresponding to transformation products (TPs) without operator bias. Structures were proposed based on accurate mass and expected fragmentation patterns [13].

- Toxicity Assessment: An in-silico evaluation was performed on the identified TPs to estimate potential mutagenicity, developmental toxicity, and ecotoxicity (e.g., Fathead minnow LC₅₀) [13].

Comparative Performance Data

The efficacy of different AOPs is highly dependent on the target pollutant and operational parameters. The tables below summarize key performance metrics from experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Different AOPs in Treating Real Cosmetic Wastewater [14]

| AOP Technology | Optimal Conditions | COD Removal (%) | Final BOD₅/COD Index | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Photolysis | pH 3, 40 min | Low | Minimal Change | Least effective, relies on direct photolysis only. |

| UV/H₂O₂ | pH 3, 1 mL/L H₂O₂, 40 min | Moderate | Improved | H₂O₂ enhances radical generation under UV. |

| Photo-Fenton-like | pH 3, 0.75 g/L Fe³⁺, 1 mL/L H₂O₂, 40 min | High | Significantly Improved (0.75) | Fe³⁺ requires reduction to Fe²⁺ for optimal activity. |

| Photo-Fenton | pH 3, 0.75 g/L Fe²⁺, 1 mL/L H₂O₂, 40 min | 95.5% | 0.8 | Most effective; synergistic effect of Fe²⁺ and UV. |

Table 2: Kinetics and Ecotoxicity of Maprotiline Degradation by Various AOPs [13]

| AOP Technology | Catalyst/Oxidant | Degradation Efficiency | Transformation Products (TPs) | Ecotoxicity Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photocatalysis | Fe-ZnO, Ce-ZnO, TiO₂ | Fastest kinetics (>99% in <40 min) | Multi-hydroxylated derivatives, ring-opening species. | TPs from hydroxylation on the bridge or ring-opening estimated to have low toxicant properties. |

| Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton | Fe₃O₄/HA + H₂O₂ | Slower than photocatalysis | Similar to photocatalysis pathways. | - |

| Persulfate-Based AOP | Fe₃O₄/HA + S₂O₈²⁻ | Slower than photocatalysis | Different TPs, with ring-opening species showing higher persistence. | SO₄•⁻ mediated pathway can lead to distinct, sometimes more persistent TPs. |

Table 3: Merits and Limitations of Radical vs. Nonradical Pathways in Persulfate-Based AOPs [11]

| Aspect | Radical Pathways (•OH, SO₄•⁻) | Nonradical Pathways (¹O₂, High-valent metals) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Rate | High rate constants for contaminant degradation. | Generally slower, more selective reactions. |

| Selectivity | Non-selective, attacks most electron-rich organics. | Selective for contaminants with specific electron-donating groups. |

| Matrix Interference | High susceptibility to scavenging by carbonates, chlorides, etc. | Minimal interference from common water constituents. |

| Energy Consumption | Lower estimated Electrical Energy per Order (EE/O). | Significantly higher EE/O, making them more energy-intensive. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The experimental execution of AOPs relies on a core set of chemical reagents and analytical tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions in AOP research.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AOP Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in AOPs | Common Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Primary oxidant source for generating •OH in Fenton, Photo-Fenton, and UV/H₂O₂ processes. | Typically used at 30% concentration. Requires careful dosing to avoid scavenging effects [14] [8]. |

| Persulfate (Na₂S₂O₈ or K₂S₂O₈) | Oxidant precursor for generating sulfate radicals (SO₄•⁻). | Can be activated by heat, UV, transition metals, or alkaline conditions [13] [11]. |

| Ferrous Salts (FeSO₄·7H₂O) | Homogeneous catalyst for Fenton and Photo-Fenton reactions. Provides Fe²⁺ to decompose H₂O₂. | Works optimally at pH 2.5–3.5. Sludge formation is a drawback [9] [14]. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Fe₃O₄, CuFeS₂, TiO₂) | Solid catalysts for heterogeneous Fenton, photo-Fenton, and photocatalysis. Enable catalyst recovery and reuse. | Mitigate sludge issues. Catalysts like chalcopyrite (CuFeS₂) can self-regulate pH and provide multiple active sites [13] [8] [12]. |

| pH Adjusters (H₂SO₄, NaOH) | To optimize reaction pH for specific AOPs (e.g., pH 3 for Fenton) and to quench reactions post-treatment. | Essential for reproducible results. Quenching with NaOH stops radical generation by decomposing H₂O₂ [14]. |

| Scavengers (e.g., Methanol, TBA, NaN₃) | Used in mechanistic studies to identify the contribution of specific radicals (e.g., •OH vs. SO₄•⁻ vs. ¹O₂). | Methanol quenches both •OH and SO₄•⁻; tert-Butanol (TBA) is more selective for •OH; Sodium Azide quenches ¹O₂ [16] [11]. |

The systematic comparison of Advanced Oxidation Processes reveals a complex landscape where the optimal technology is dictated by the specific pollutant matrix, desired treatment goals, and economic constraints. Radical generation pathways, particularly those producing hydroxyl and sulfate radicals, offer rapid and non-selective destruction of contaminants, making them highly effective for a broad spectrum of pollutants. However, challenges such as matrix sensitivity, energy consumption, and the potential formation of transformation products necessitate a careful, well-instrumented approach to process validation. The integration of AOPs—particularly using the Photo-Fenton process as a pre-treatment to enhance biodegradability—presents a promising and sustainable strategy for treating complex industrial wastewaters, effectively bridging advanced chemical oxidation with biological remediation [9] [14]. Future research must continue to focus on standardizing experimental protocols, developing more stable and active heterogeneous catalysts, and conducting thorough toxicity assessments of transformation products to ensure the safe and scalable application of these powerful technologies.

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) represent a revolutionary class of catalytic materials defined by the isolation of individual metal atoms on solid supports. These catalysts create a bridge between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis, combining the high activity and selectivity of molecular catalysts with the stability and recyclability of traditional heterogeneous systems [17]. The fundamental architectural principle of SACs involves stabilizing individual metal atoms through coordination with surface atoms of a support material, typically through heteroatoms such as nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur, or at defect sites [18] [19]. This unique structural configuration eliminates ensemble effects—a characteristic of nanoparticle catalysts where multiple adjacent metal atoms can promote undesired reaction pathways—and instead creates uniform, well-defined active sites that can be precisely engineered at the atomic level [19]. The maximized atomic utilization efficiency, potentially approaching 100%, coupled with the uniformity of active sites, gives SACs their distinctive catalytic properties, making them particularly promising for applications requiring high selectivity, such as pharmaceutical synthesis and environmental remediation [18] [17].

The field has expanded rapidly since the term "single-atom catalyst" was first formally coined in 2011 with the demonstration of single platinum atoms stabilized on iron oxide [17] [19]. Research has since progressed to encompass a wide variety of metal centers and support materials, with applications spanning thermal, electrochemical, and photocatalytic processes [19]. This review examines the fundamental atomic-scale mechanisms governing the efficiency and selectivity of SACs, provides comparative performance data against traditional catalytic systems, and details experimental methodologies for their study, all within the context of validating catalytic remediation technologies.

Atomic-Scale Mechanisms of Performance

Electronic and Geometric Structure of Active Sites

The exceptional catalytic properties of SACs originate from their distinctive electronic and geometric structures. Unlike metal nanoparticles where continuous energy bands form, the isolated nature of single atoms creates discrete molecular orbitals, leading to unique adsorption properties for reactant molecules [19]. The local coordination environment—comprising the number, type, and spatial arrangement of atoms directly bonded to the metal center—fundamentally determines the electronic structure of the active site and thus its binding energy with reaction intermediates [18] [20]. This strong metal-support interaction is crucial for both stabilizing the single atoms against aggregation and modulating their catalytic behavior [17].

For instance, the introduction of heteroatoms such as sulfur or oxygen into the common metal-nitrogen-carbon (M-N-C) structure can significantly alter the electron density distribution around the metal center. Studies have demonstrated that single-atom cobalt centers anchored to both nitrogen and sulfur atoms (SA Co-N/S) exhibit enhanced catalytic activity for sulfur reduction reactions in sodium-sulfur batteries compared to conventional Co-N-C sites [20]. This enhancement is attributed to the optimized electronic structure that facilitates the adsorption and transformation of reaction intermediates. The geometric confinement of single atoms in specific coordination environments, such as the pore structures of zeolites or defects on carbon surfaces, further constrains the orientation and configuration in which substrate molecules can approach the active site, imparting shape selectivity reminiscent of enzymatic catalysis [19].

Selectivity Mechanisms in SACs

The high selectivity observed in SAC-mediated reactions stems primarily from two atomic-level phenomena: the absence of ensemble effects and the tailored intermediate binding energies.

Elimination of Ensemble Effects: In nanoparticle catalysts, the presence of contiguous metal atoms (ensembles) creates multiple potential adsorption sites with varying geometries. This multiplicity can lead to the stabilization of different reaction intermediates and thus diverse reaction products. In contrast, the singular, isolated nature of SAC active sites ensures that reactant molecules interact with only one metal atom in a consistent, well-defined coordination environment [19]. This uniformity dramatically reduces the parallel pathways available for reaction, funneling substrates toward a specific product. For example, in the two-electron oxygen reduction reaction (2e- ORR) crucial for hydrogen peroxide production, SACs can achieve selectivity exceeding 90% for H₂O₂, whereas nanoparticle catalysts often favor the competing four-electron pathway to water due to the presence of ensemble sites that facilitate O-O bond cleavage [21].

Precise Energetic Tuning: The binding energy of reaction intermediates represents a critical determinant of catalytic selectivity. SACs offer unparalleled opportunities for fine-tuning these energies through rational design of the metal center's coordination environment [18] [21]. By systematically varying the coordination number and the electronegativity of coordinating atoms, researchers can precisely adjust the d-band center of the metal atom, which in turn governs its adsorption properties [18]. This capability enables the optimization of catalyst performance near the theoretical maxima described by Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi relationships [19]. In the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), for instance, different M-N-C configurations exhibit markedly different overpotentials due to variations in the binding strength of oxygen-containing intermediates, directly impacting both efficiency and selectivity [22].

Table 1: Comparative Selectivity in Key Catalytic Reactions

| Reaction | Catalyst Type | Selectivity/Efficiency | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2e- Oxygen Reduction (H₂O₂ production) | Pt Nanoparticles | 40-60% [21] | Multiple adsorption modes on metal ensembles |

| Fe-N-C SAC | 90-95% [21] | Isolated sites prevent O-O bond cleavage | |

| Sulfur Reduction (Na-S batteries) | Carbon alone | Low, incomplete transformation [20] | Slow reaction kinetics |

| SA Co-N/S | Near-complete transformation [20] | Optimal polysulfide adsorption energy | |

| Oxygen Evolution Reaction | IrO₂/RuO₂ Nanoparticles | High activity but low atom efficiency [22] | Surface metal atoms participate |

| Ni-N-C SAC | Comparable activity, high atom efficiency [22] | Tunable metal-oxo intermediate binding |

Performance Comparison: SACs vs. Traditional Catalysts

Quantitative Activity and Efficiency Metrics

The atom efficiency of SACs represents one of their most significant advantages over conventional nanoparticle and bulk catalysts. By utilizing nearly every metal atom as an active site rather than burying the majority in the particle interior, SACs achieve extraordinary mass activity values, particularly important for reactions involving precious metals [17]. For example, Pt-based SACs have demonstrated mass activities for oxygen reduction reactions that are 10-50 times higher than commercial Pt/C nanoparticle catalysts [19]. This enhancement translates directly to reduced material costs, especially crucial for noble metals like Pt, Pd, and Ir, which are often essential for key energy conversion and pharmaceutical reactions but are limited by scarcity and expense.

Beyond mere atom utilization, the intrinsic activity (turnover frequency, TOF) of properly designed SACs can rival or exceed that of nanoparticle analogues. This counters the initial assumption that single atoms might be inherently less active due to their strong interaction with supports. For instance, in the electrocatalytic production of hydrogen peroxide, Co-N₄ sites embedded in graphene have shown turnover frequencies superior to conventional Au-Pd bimetallic nanoparticles, while also maintaining higher selectivity [21]. Similarly, for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), single-atom Ir catalysts on hematite supports have achieved high current densities at significantly reduced overpotentials compared to benchmark IrO₂ and RuO₂ catalysts [22].

Table 2: Comparative Performance Metrics for Oxygen Reduction Reaction

| Catalyst Type | Metal Loading | Mass Activity | Selectivity for H₂O₂ | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt Nanoparticles (Commercial) | ~20 wt% | Baseline | 40-60% [21] | Good, but Pt leaching possible |

| Au-Pd Nanoparticles | 1-5 wt% | Comparable to Pt | 70-80% [21] | Deactivation via alloy restructuring [21] |

| Fe-N-C SAC | 0.5-2 wt% | 5-10x higher than Pt [21] | 90-95% [21] | Excellent in acidic media |

| Co-N-C SAC | 0.5-2 wt% | 3-8x higher than Pt [21] | 85-90% [21] | Good, but sensitive to coordination environment |

Stability and Durability Considerations

While SACs offer exceptional performance advantages, their stability under operational conditions presents both challenges and unique opportunities. The high surface free energy of individual metal atoms creates a thermodynamic driving force for aggregation into clusters or nanoparticles, particularly under reducing conditions or at elevated temperatures [19]. This instability was observed in early SAC systems, where single atoms would agglomerate during reaction, leading to performance degradation. However, advanced stabilization strategies have yielded remarkable improvements. Properly designed SACs with strong covalent metal-support interactions can exhibit exceptional stability, even under harsh reaction conditions [19].

The dynamic behavior of SACs under operating conditions is complex and reaction-dependent. For example, Pt/CeO₂ catalysts demonstrate reversible structural transformations where single atoms disperse under oxidizing conditions but form nanoparticles under reducing environments [19]. Similarly, Rh/TiO₂ catalysts show nanoparticle disintegration into single atoms under CO₂ reduction conditions [19]. This structural flux highlights the importance of operando characterization to identify the true active species during catalysis. When optimally stabilized—often through confinement in porous matrices or strong coordination to heteroatom-doped supports—SACs have demonstrated operational stability exceeding hundreds of hours in reactions such as electrochemical CO₂ reduction and selective hydrogenation [19].

Experimental Protocols for SAC Characterization

Synthesis and Anchoring Strategies

The successful preparation of SACs requires precisely controlled synthesis methods that prevent nuclearization and aggregation while achieving sufficient metal loading. Common approaches include:

Wet-Impregnation and Strong Electrostatic Adsorption: This method involves depositing metal precursors from solution onto oppositely charged surface sites on the support, leveraging electrostatic interactions to achieve high dispersion [17]. Subsequent careful thermal treatment removes ligands and establishes metal-support bonds.

Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD): ALD offers exceptional control over metal deposition at the atomic scale through self-limiting gas-surface reactions [17]. This technique enables precise tuning of metal loading by controlling the number of deposition cycles and is particularly valuable for creating model SAC systems.

High-Temperature Atom Trapping: This innovative approach utilizes the reversible transformation between single atoms and nanoparticles under different atmospheres. For instance, Pt/CeO₂ catalysts can be cycled between oxidized single atoms and reduced nanoparticles, allowing the formation of thermally stable SACs [19].

Co-precipitation and Chemical Vapor Deposition: These methods enable the direct synthesis of SACs by either co-precipitating metal precursors with support materials or through gas-phase deposition of volatile metal complexes [17].

Critical to all these methods is the presence of effective anchoring sites on the support material. These include doped heteroatoms (e.g., N, S, P in carbon materials), surface defects (vacancies, step edges), cavity sites (in zeolites or MOFs), and surface functional groups that can strongly coordinate with metal cations [17].

Operando Characterization Techniques

Understanding the structure and function of SACs under realistic working conditions requires advanced characterization techniques, particularly operando methods that simultaneously monitor catalyst structure and catalytic performance.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS): As a local structural probe, XAS is arguably the most powerful technique for SAC characterization [19]. It provides element-specific information about oxidation state (XANES region) and local coordination environment (EXAFS region). The absence of metal-metal scattering paths in EXAFS spectra provides definitive evidence of atomic dispersion. Operando XAS cells have been developed for both gas-phase and electrochemical reactions, enabling researchers to correlate structural changes with catalytic activity in real time [19].

Advanced Electron Microscopy: Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) allows direct visualization of individual heavy metal atoms on lighter supports [19]. When combined with electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), it can provide information about the electronic structure of single atoms.

Infrared Spectroscopy: Probe molecules such as CO can be used in IR spectroscopy to identify single atoms through their distinct vibrational frequencies compared to metal clusters or nanoparticles [19].

Synchrotron-Based X-ray Techniques: Methods such as X-ray photon spectroscopy operando provide additional electronic structure information complementary to XAS [19].

The integration of these experimental findings with computational modeling, particularly density functional theory (DFT) calculations and emerging machine learning approaches, has proven invaluable for deciphering the complex structure-activity-stability relationships in SACs [19].

Diagram 1: SAC Experimental Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SAC Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | Metal acetylacetonates (Fe(acac)₃, Co(acac)₃), Chlorides (H₂PtCl₆, PdCl₂), Nitrates | Source of active metal centers for SAC synthesis |

| Support Materials | High-surface-area carbon, Graphene oxide, g-C₃N₄, Zeolites (ZSM-5, HY), Metal-organic frameworks (ZIF-8, UiO-66) | Provide anchoring sites and high surface area for dispersion |

| Heteroatom Dopants | Melamine (N source), Thiourea (S source), Phytic acid (P source) | Create coordination sites for metal anchoring and modulate electronic structure |

| Characterization Probes | CO for IR spectroscopy, NO for EPR studies | Identify nature and coordination environment of active sites |

| Synthesis Equipment | Tube furnaces for pyrolysis, ALD reactors, Ultrasonication baths | Enable controlled synthesis under specific conditions |

| In Situ Cells | Electrochemical flow cells, High-temperature/pressure reaction cells | Allow operando characterization under working conditions |

Single-atom catalysts represent a transformative approach to catalytic design, offering unprecedented control over active site structure at the atomic level. Their exceptional efficiency and selectivity stem from fundamental mechanisms including the elimination of ensemble effects, precise tuning of intermediate binding energies through coordination engineering, and maximum atom utilization efficiency. While challenges remain in achieving high metal loadings with uniform site distribution and ensuring stability under demanding operational conditions, advanced synthesis strategies and stabilization methods continue to push the boundaries of SAC performance.

The future of SAC research lies in several promising directions: the rational design of dual-atom and multi-atom sites to exploit synergistic effects between adjacent metal centers [18]; the application of machine learning and natural language processing approaches to accelerate catalyst discovery and optimization [20]; the development of more sophisticated operando characterization techniques to capture dynamic structural changes during catalysis [19]; and the scaling of synthesis methods to enable industrial application beyond laboratory demonstrations [23]. As these advancements mature, SACs are poised to make significant contributions to sustainable chemical synthesis, environmental remediation, and energy conversion technologies by maximizing efficiency and minimizing waste of precious resources.

Photocatalytic materials transform solar energy into chemical energy to drive reactions critical for environmental remediation, such as breaking down organic pollutants in wastewater [24]. The effectiveness of this process depends on a semiconductor's ability to absorb light and utilize the resulting energetic charge carriers [25]. When a photocatalyst absorbs photons with energy exceeding its bandgap energy, electrons (e⁻) are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), generating positively charged holes (h⁺) in the VB [26]. These photogenerated electron-hole pairs are the primary agents for initiating surface redox reactions [27].

However, the full potential of photocatalysis is limited by two intrinsic and competing material properties: (1) Rapid electron-hole recombination, where photogenerated charges recombine on picosecond to millisecond timescales, dissipating their energy as heat or light before they can participate in surface reactions; and (2) Limited visible-light absorption, as many effective photocatalysts like TiO₂ and ZnO possess wide bandgaps, restricting their photoactivity to the ultraviolet (UV) region, which constitutes only a small fraction (~4%) of solar energy [28] [29]. This review objectively compares leading material engineering strategies—bandgap engineering and charge dynamics optimization—by synthesizing experimental data to validate their performance in catalytic remediation.

Core Principles and Performance-Limiting Dynamics

The photocatalytic process involves three sequential steps: light absorption, charge separation and migration, and surface redox reactions [27] [30]. The overall efficiency is the product of the quantum yields for each step. The charge separation step is particularly critical as it links ultrafast photoexcitation (femtoseconds to picoseconds) to much slower surface reactions (microseconds to seconds), creating a vast temporal span where recombination is favored [31].

The inherent Coulombic attraction between photogenerated electrons and holes drives recombination, which occurs through both bulk and surface pathways [26]. Material properties such as a low dielectric constant can lead to the formation of bound electron-hole pairs (excitons) with limited mobility. Furthermore, intrinsic defects (e.g., point defects, grain boundaries) often act as recombination centers, trapping charge carriers and increasing the probability of non-productive recombination [26]. The performance of a photoelectrode can be quantified by the photocurrent density (J), which is a function of three key efficiencies: J = ηabs × ηsep × ηinj, where ηabs is the light absorption efficiency, ηsep is the bulk charge separation efficiency, and ηinj is the surface charge injection efficiency [31].

Table 1: Key Performance-Limiting Factors in Photocatalytic Materials

| Factor | Impact on Performance | Characteristic Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Wide Bandgap | Limits light absorption to UV spectrum; poor utilization of solar energy. | UV-Vis DRS shows no absorption above ~400 nm (e.g., pure TiO₂, ZnO) [24] [28]. |

| Fast Charge Recombination | Reduces the number of available electrons/holes for surface reactions; lowers quantum yield. | PL and TRPL spectra show high intensity and short carrier lifetime; low photocurrent in TPC measurements [31] [26]. |

| Low Surface Area & Active Sites | Limits adsorption of reactant molecules (e.g., pollutants, CO₂, H₂O). | BET analysis shows low specific surface area; low degradation efficiency despite good charge separation [30]. |

| Slow Surface Reaction Kinetics | Creates a bottleneck; accumulated charges can recombine at the surface. | SPECM reveals low surface redox currents; product yield does not scale with improved photocurrent [31]. |

Comparative Analysis of Bandgap Engineering Strategies

Bandgap engineering aims to extend the spectral response of wide-bandgap semiconductors into the visible light region and to enhance the separation of photogenerated charges. The following strategies are systematically compared.

Doping with Metal and Non-Metal Elements

Doping introduces foreign atoms into the semiconductor lattice to create new energy states within the bandgap, reducing the energy required for electron excitation.

- Metal Doping (Cu, Ce, etc.): Incorporating metal ions into a host lattice like ZnO or TiO₂ can introduce impurity levels within the bandgap. For instance, constructing atomic-level redox sites (Cu-Vo-Ti) in TiO₂ enhanced electron spin polarization and built "frustrated" electron-hole pairs, which decreased the carrier recombination rate. This extended light absorption and enabled photocatalytic conversion of low-concentration CO₂ (15%) to CH₄ at a rate of 25.87 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ [32].

- Non-Metal Doping (N, P, etc.): Doping with non-metals such as nitrogen or phosphorus is a prominent method for modifying the band structure of TiO₂. Similarly, P-doped TiO₂-MWCNT composites have demonstrated significant bandgap reduction and improved charge carrier dynamics [28] [33].

Heterojunction Engineering

Constructing heterojunctions between two or more semiconductors with aligned band structures is a powerful strategy to improve charge separation by creating an internal electric field that drives electrons and holes in opposite directions.

- Traditional Heterojunctions (Type-II): In a ZnO/CuO system, CuO is a p-type narrow-bandgap (~1.35-1.7 eV) semiconductor. When combined with n-type ZnO, a p-n heterojunction forms. The internal electric field at the junction promotes the migration of electrons to ZnO and holes to CuO, effectively separating the charge carriers [29] [33]. A composite film of ZnO nanorods and CuO demonstrated a significantly enlarged absorption range into visible light and suppressed the recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, leading to a 93% degradation efficiency of Rhodamine B dye, outperforming pure ZnO (78%) or CuO (55%) films [29].

- Z-Scheme and S-Scheme Heterojunctions: These advanced heterojunctions mimic natural photosynthesis and are designed to achieve more efficient charge separation while preserving the strong redox ability of the photocatalyst. For example, ultrathin nanosheet CeVO₄/WO₃·H₂O Z-scheme heterojunction effectively separates photo-carriers, while the charge carriers in NiTiO₃/CdS follow the S-scheme transfer pathway, which effectively hinders their recombination and prevents the photodegradation of the metal sulfide [30].

Dye Sensitization and Carbon Nanomaterial Composites

- Dye Sensitization: This process involves attaching dye molecules with broad visible light absorption to the surface of a wide-bandgap semiconductor. The dye acts as a photosensitizer, absorbing visible light and injecting excited electrons into the conduction band of the semiconductor.

- Carbon Nanomaterial Composites: Integrating carbon nanomaterials like Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) or graphene can enhance electron transfer and provide a high surface area. MWCNTs possess substantial electron storage capacity and can accept photo-generated electrons across a heterojunction, thereby increasing the electron-hole pair recombination time [24]. The synthesis method is critical; an in-situ sol-gel synthesized CNTs-TiO₂ nanocomposite achieved 94% degradation of Methylene Blue, while an ex-situ mechanically mixed composite with ten times more MWCNT content showed only 89% degradation, highlighting the importance of strong chemical interactions for efficient charge transfer [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bandgap Engineering Strategies for TiO₂ and ZnO

| Engineering Strategy | Material System | Bandgap Reduction / Absorption Range | Reported Performance Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Doping | Cu-Vo/TiO₂ [32] | Enhanced visible light absorption | CH₄ production: 25.87 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ (at 15% CO₂) |

| Non-Metal Doping | N-doped ZnO [28] | Extended absorption into visible region | Improved degradation of organic dyes under visible light |

| Heterojunction (Type-II) | ZnO NRs/CuO film [29] | Broad absorption up to 800 nm | RhB degradation: 93% (vs. 78% for ZnO alone) |

| Heterojunction (Z-Scheme) | CeVO₄/WO₃·H₂O [30] | Improved charge separation | Enhanced CO₂ photoreduction efficiency |

| Carbon Composite | In-situ CNTs-TiO₂ [24] | Bandgap tuning with MWCNTs | MB degradation: 94% (vs. 89% for ex-situ) |

| Ternary Composite | Chitosan-CuO-ZnO [33] | Bandgap reduced from 3.2 eV to 2.2 eV | Direct Violet 51 degradation: 92.3% in 80 min |

Advanced Characterization of Electron-Hole Pair Dynamics

Optimizing material performance requires precise characterization of charge carrier dynamics, which occur across multiple time and space scales [26].

Key Characterization Techniques

- Time-Resolved Photoluminescence (TRPL): Measures the decay lifetime of photoluminescence emission, which is directly related to the recombination rate of electron-hole pairs. A longer lifetime indicates more effective charge separation and a higher probability of charges reaching the surface to participate in reactions [31] [26].

- Transient Absorption Spectroscopy (TAS): Probes the transient relaxation processes of electron-hole pairs in excited states, typically with picosecond resolution. It can track the population and dynamics of photogenerated charges directly, providing insights into trapping and recombination pathways [31] [26].

- Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM): Enables direct mapping of surface potentials and charge carrier accumulation under operational conditions with high spatial resolution. It can visualize surface photovoltage differences across different crystal planes and in heterostructures [31] [26].

- Photoelectrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (PEIS) & Transient Photocurrent (TPC): PEIS measures the charge transfer resistance at the electrode/electrolyte interface, while TPC provides insights into carrier separation efficiency and the kinetics of surface reactions by analyzing the current response to a light pulse [31] [26].

- In-situ and Operando Techniques: In-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can monitor surface redox processes and interfacial charge redistributions under realistic reaction conditions. In-situ TEM allows for real-time observation of structural changes and even photocatalytic reactions in specially designed liquid cells [31] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Photocatalyst Development

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium n-butoxide (C₁₆H₃₆O₄Ti) | Common Ti precursor for sol-gel synthesis of TiO₂ nanoparticles and films. | Synthesis of TiO₂ nanopowder and in-situ CNT-TiO₂ composites [24] [32]. |

| Zinc Acetate Dihydrate | Zn precursor for synthesizing ZnO nanostructures (e.g., nanorods, nanoparticles). | Formation of ZnO nanorods in ZnO/CuO heterojunctions [29] [33]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Electron acceptor and conductive scaffold to enhance charge separation in composites. | Fabrication of CNT-TiO₂ and CNT-ZnO composites for dye degradation [24]. |

| Copper Nitrate / Chloride | Source of Cu ions for doping or forming CuO in heterostructures. | Creating Cu-doped TiO₂ and CuO/ZnO p-n junctions [33] [32]. |

| Chitosan | Biopolymer matrix to improve nanoparticle dispersion, stability, and prevent agglomeration. | Synthesis of Chitosan-CuO-ZnO ternary nanocomposites [33]. |

| Methylene Blue (C₁₆H₁₈ClN₃S) | Model organic pollutant dye for standardized assessment of photocatalytic degradation efficiency. | Benchmarking performance of catalysts like CNT-TiO₂ and ZnO/CuO [24] [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

To ensure the reproducibility and objective comparison of photocatalytic materials, standardized experimental protocols are critical. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the cited research.

Protocol for Photocatalytic Dye Degradation

This test assesses a material's ability to decompose organic pollutants under light irradiation [24] [29].

- Catalyst Preparation: The photocatalyst is typically immobilized as a film on a substrate (e.g., glass) or used as a powder suspension in the dye solution.

- Adsorption-Desorption Equilibrium: The catalyst is mixed with the dye solution (e.g., 10-20 mg/L Methylene Blue) and stirred in the dark for 30-60 minutes to establish a baseline concentration and account for any adsorption.

- Light Irradiation: The mixture is illuminated under a controlled light source (e.g., a 100 W Xe lamp with a λ > 420 nm cut-off filter to exclude UV light for visible-light tests). Constant stirring is maintained.

- Sampling and Analysis: At regular time intervals, aliquots of the solution are extracted. The concentration of the remaining dye is determined by measuring its characteristic absorption peak intensity (e.g., 664 nm for Methylene Blue) using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Data Calculation: The degradation efficiency (η) is calculated as η (%) = [(C₀ - Cₜ) / C₀] × 100%, where C₀ is the initial concentration after dark adsorption, and Cₜ is the concentration at time t. The kinetics are often analyzed using a pseudo-first-order model.

Protocol for Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Characterization

PEC measurements evaluate the electrical properties related to charge generation and separation within the photocatalyst [31] [26].

- Working Electrode Fabrication: The photocatalytic material is deposited onto a conductive substrate (e.g., Fluorine-doped Tin Oxide glass, FTO) to create a photoanode or photocathode.

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: A standard three-electrode configuration is used with the prepared photoanode as the working electrode, a platinum wire or mesh as the counter electrode, and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or SCE). An aqueous electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M Na₂SO₄) is used.

- Transient Photocurrent (TPC) Measurement: The electrode is illuminated with intermittent light (e.g., using a mechanical chopper). The resulting current spikes and decays are recorded, which provide information about charge separation efficiency and recombination rates.

- Photoelectrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (PEIS): This is performed by applying a small AC voltage bias (e.g., 10 mV) over a wide frequency range (e.g., 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz) under light illumination. The resulting Nyquist plot is fitted with an equivalent circuit to extract the charge transfer resistance (R_ct) at the electrode/electrolyte interface.

The objective comparison of experimental data confirms that no single material engineering strategy universally outperforms all others. The optimal approach depends on the target application and the specific performance bottleneck being addressed. Heterojunction engineering, particularly p-n junctions like ZnO/CuO, has proven highly effective for enhancing the separation of electron-hole pairs, directly tackling the recombination challenge [29]. Concurrently, doping and composite formation with carbon materials are powerful for extending the optical response of wide-bandgap semiconductors into the visible light region, thereby maximizing solar energy utilization [24] [32].

Future developments in photocatalytic remediation will likely involve the rational design of more complex multi-component systems that synergistically combine multiple strategies. The integration of advanced characterization techniques like in-situ TEM and KPFM is crucial for moving beyond correlative studies to establish causative links between material structure, charge dynamics, and catalytic function at the atomic level [26] [27]. Furthermore, the application of machine learning is emerging as a powerful tool for the high-throughput screening and prediction of new photocatalytic materials, potentially accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalysts with precisely engineered band structures and optimized charge carrier dynamics for superior performance in environmental remediation [30].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are a group of oxygen-derived, highly reactive molecules that serve as pivotal intermediates in catalytic processes central to sustainable energy and environmental remediation. In electrocatalytic systems such as fuel cells and metal-air batteries, the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) proceeds through multiple pathways (2e⁻, 3e⁻, and 4e⁻) that generate distinct ROS intermediates, significantly influencing both efficiency and durability [34]. These ROS, including superoxide radical (O₂•⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radical (•OH), exhibit markedly different reactivities, lifetimes, and diffusion capabilities, making their precise identification and quantification essential for understanding catalytic mechanisms and optimizing system performance [35] [36]. The accurate measurement of these transient species presents substantial analytical challenges due to their high reactivity, low steady-state concentrations, and short lifespans at catalytic interfaces [34] [37]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of contemporary analytical techniques for ROS detection, equipping researchers with the methodological foundation necessary for rigorous performance validation of catalytic remediation methods.

Comparative Analysis of ROS Detection Methodologies

The selection of an appropriate detection method is paramount, as each technique possesses unique strengths, limitations, and suitability for specific ROS and experimental conditions. The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison of the primary methodologies used in catalytic systems.

Table 1: Core Analytical Techniques for ROS Identification and Quantification

| Technique | Principle | Key ROS Detected | Sensitivity | Spatio-Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Oxidation of fluorescent probes (e.g., DCFH-DA, MitoSOX) yields fluorescent products [34]. | H₂O₂, O₂•⁻, •OH (indirect) [34] [38]. | High (nanomolar range) [38]. | Real-time (ms), subcellular [34]. | Real-time monitoring in live cells; catalyst surface activity mapping [34] [38]. | High sensitivity and selectivity with specific probes; real-time kinetics [34]. | Probe instability in harsh (acidic/alkaline, high T) conditions; potential photobleaching [34]. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Direct detection of unpaired electrons in radical species using spin traps (e.g., DMPO, TEMP) [34] [37]. | O₂•⁻, •OH (direct) [34] [36]. | Very High (direct radical detection) [37]. | Bulk measurement, no inherent spatial resolution. | "Gold standard" for definitive radical identification; quantifying ROS production rates in materials [37] [39]. | Direct, unambiguous identification of radical species; quantitative potential [35] [37]. | Requires sophisticated instrumentation; spin trap artifacts possible; not all ROS are paramagnetic. |

| Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) & Chemiluminescence (CL) | ROS reaction with luminescent reagents (e.g., luminol) generates light emission [34] [39]. | O₂•⁻, H₂O₂, •OH [36] [39]. | Very High (single-molecule potential) [34]. | High temporal resolution; ECL imaging (ECLM) enables spatial mapping [34]. | Evaluating oxygen vacancy content on catalysts; online detection of photogenerated ROS [39]. | Extremely high sensitivity; simple operation for CL; can be correlated with surface defects [39]. | Signal can be influenced by non-ROS factors (pH, ions); requires specific luminescent probes. |

| UV-vis Absorption Spectroscopy | Measurement of absorbance changes from ROS or reaction products with chromogenic substrates (e.g., TMB, ABTS) [34] [36]. | H₂O₂, •OH (often via nanozyme-catalyzed reactions) [36]. | Moderate to High | Bulk measurement. | Quantitative H₂O₂ detection; monitoring nanozyme peroxidase-/oxidase-like activity [36]. | Simple, cost-effective, and readily accessible instrumentation. | Lower specificity and sensitivity compared to fluorescence/EPR; indirect measurement. |

| Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM) | Electrochemical current measurement at an ultramicroelectrode tip scanned near a surface [34]. | O₂•⁻, H₂O₂ (redox mapping) [34]. | High (micromolar) | Micrometer-level spatial resolution. | Mapping spatial distribution of ROS generation at electrode/electrocatalyst surfaces [34]. | Provides spatially resolved activity maps; operates in liquid environments. | Complex setup; relatively slow imaging; can perturb the local environment. |

Table 2: Advanced and Emerging Techniques for ROS Analysis

| Technique | Principle | Key ROS Detected | Spatio-Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Molecule Fluorescence Microscopy (SMFM) | Detection of stochastic fluorescence bursts from single ROS generation events at catalytic sites [34]. | H₂O₂, O₂•⁻ | Single-catalyst level, millisecond temporal resolution [34]. | Probing intrinsic heterogeneity and structure-activity relationships of individual nanocatalysts [34]. | Reveals catalytic heterogeneity and dynamics hidden in ensemble averages. | Technically demanding; very low signals require highly sensitive detectors. |

| Computational Studies (e.g., DFT) | Modeling adsorption energies and reaction pathways for ROS formation on catalyst surfaces [40]. | O₂, H₂O, •OOH, OH (=adsorbed) [40]. | Atomic scale, theoretical predictions. | Predicting favorable ROS generation pathways; guiding rational catalyst design (e.g., ZnO, TiO₂) [40]. | Provides atomic-level mechanistic insights not easily accessible experimentally. | Results are dependent on the accuracy of the computational model and functional used. |

| Nanozyme-Based Detection | Catalytic activity of nanomaterials (e.g., CeO₂, IONPs) mimicking natural enzymes (SOD, POD) to produce or scavenge ROS [36]. | O₂•⁻, H₂O₂ | Varies with detection method (often colorimetric/fluorimetric). | Biosensing, antioxidant therapy, and as tunable catalysts for ROS-mediated reactions [36]. | High stability, tunable activity, cost-effective compared to natural enzymes. | Complex reaction mechanisms; activity depends on size, composition, and surface chemistry. |

Experimental Protocols for Key ROS Detection

Protocol: Quantifying Superoxide Radical (O₂•⁻) via Chemiluminescence

This protocol utilizes a Continuous Flow Chemiluminescence (CFCL) system to rapidly evaluate the O₂•⁻ generation capacity of photocatalysts, a method effectively demonstrated with nano-TiO₂ [39].

- Principle: Luminol, a chemiluminescent probe, reacts with photogenerated O₂•⁻ in the presence of dissolved oxygen and a catalyst (e.g., nano-TiO₂), producing a light signal proportional to the O₂•⁻ concentration. The intensity of this signal has been shown to correlate positively with the density of surface oxygen vacancies on the catalyst, which are active sites for O₂ adsorption and reduction [39].

- Materials:

- Catalyst suspension (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL nano-TiO₂ in purified water)

- Luminol stock solution (e.g., 50 μM in pH 10.6 carbonate buffer)

- Continuous Flow Chemiluminescence (CFCL) apparatus

- Peristaltic pumps

- Spiral flow cell housed in a chemiluminescence analyzer

- Photomultiplier Tube (PMT)

- Procedure:

- Setup: Connect separate reservoirs for the catalyst suspension and the luminol solution to the peristaltic pumps. The pumps should feed these streams into a mixing tee, which then leads into the spiral flow cell positioned directly in front of the PMT.

- Dark Baseline: Initiate flow of both catalyst suspension and luminol solution in the absence of light. Record the background CL signal, which may originate from surface defects interacting with luminol [39].

- Photo-Illumination: Expose the catalyst suspension reservoir to light (e.g., UV or simulated solar light) with a defined intensity and wavelength.

- Signal Acquisition: Monitor the CL intensity generated in the flow cell using the PMT. The signal is recorded as a function of time.

- Specificity Control: To confirm the signal originates from O₂•⁻, introduce a specific scavenger like Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) into the reaction stream. A significant decrease in CL signal confirms the involvement of O₂•⁻ [39].

- Data Interpretation: The steady-state CL intensity under illumination, after subtracting the dark signal, is proportional to the rate of O₂•⁻ generation. This method allows for the rapid ranking of different catalysts or the same catalyst modified to have different surface defect densities [39].

Protocol: Direct Identification of Radicals using Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR)

EPR spectroscopy is considered the "gold standard" for the direct and definitive detection of paramagnetic ROS radicals like O₂•⁻ and •OH [35] [37].

- Principle: Radicals with unpaired electrons are detected by their resonance in a magnetic field. Due to their short lifetimes, spin trap agents (e.g., DMPO for •OH and O₂•⁻) are used, which react with transient radicals to form more stable, EPR-detectable nitroxide radical adducts, each with a characteristic spectrum [34] [36].

- Materials:

- Catalytic reaction mixture

- Spin trap (e.g., 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide, DMPO)

- EPR spectrometer with resonant cavity

- Aqueous flat cell or quartz capillary tubes

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the catalyst with relevant reactants (e.g., H₂O₂ for Fenton-type reactions, or O₂-saturated solvent for photocatalytic systems) in the presence of the spin trap.

- Reaction & Loading: Allow the reaction to proceed for a defined time and then transfer the mixture into a flat cell or capillary suitable for EPR measurement.

- Spectrum Acquisition: Place the sample in the EPR resonator and record the spectrum under specified instrument parameters (e.g., microwave power, modulation amplitude). Measurements can be performed in situ or ex situ.

- Validation: Use specific antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD for O₂•⁻) or scavengers to validate the identity of the radical adduct. The disappearance of the specific signal upon adding the scavenger confirms its identity.

- Data Interpretation: Identify the radical species by comparing the hyperfine splitting patterns of the recorded EPR spectrum with standard spectra for known spin trap-radical adducts (e.g., DMPO-OH for •OH, DMPO-OOH for O₂•⁻) [35].

Protocol: Spatial Mapping of ROS with Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM)

SECM enables the mapping of local electrochemical activity, providing spatial resolution of ROS generation across an electrode or catalyst surface [34].

- Principle: An ultramicroelectrode (UME) tip is scanned closely over the substrate surface in a solution containing electrolytes. The tip potential is held at a value sufficient to oxidize or reduce a specific ROS (e.g., O₂•⁻). Variations in the faradaic current at the tip reflect local variations in the concentration of that ROS generated by the substrate.

- Materials:

- SECM instrument with positioning system

- Ultramicroelectrode (UME) tip (e.g., Pt disk)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and counter electrode

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., O₂-saturated buffer)

- Substrate (working electrode) with deposited catalyst

- Procedure:

- Setup & Approach: Position the UME tip in the bulk solution far from the substrate. Apply the detecting potential to the tip and record the steady-state current. Approach the substrate surface until a negative feedback current is observed, indicating close proximity.

- Scanning: Initiate a raster scan of the tip over the region of interest on the catalyst surface while maintaining a constant tip-substrate distance.

- Data Collection: Record the tip current as a function of its (x, y) position.

- Control Experiments: Perform scans under different conditions (e.g., in the dark for photoelectrocatalysts, or at different substrate potentials) to establish the origin of the activity.

- Data Interpretation: The collected current data is used to generate a 2D map of electrochemical activity. Regions of high current correspond to areas of high ROS generation flux, allowing visualization of active sites and heterogeneity on the catalyst surface [34].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision-making process for selecting and applying the key ROS detection methodologies discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ROS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | Selective detection and imaging of specific ROS in solution or cells. | DCFH-DA: General oxidative stress (broad ROS sensitivity) [34].MitoSOX Red / DHE: Highly specific for superoxide (O₂•⁻), particularly in mitochondria [34] [38].Amplex Red: Specific for hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [34]. |

| Spin Traps | Stabilize transient radicals for definitive identification by EPR. | DMPO: Forms adducts with •OH and O₂•⁻ [34] [36].TEMP: Used for trapping singlet oxygen (¹O₂) [34]. |

| Chemiluminescent Probes | Highly sensitive, rapid detection of ROS, often in flow systems. | Luminol: Reacts with O₂•⁻, •OH, and other oxidants to produce light; useful for evaluating photocatalyst surface defects [39]. |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Colorimetric detection of ROS or nanozyme activity via UV-vis. | TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine): Oxidized to a blue product by H₂O₂ in peroxidase-like reactions [36].ABTS (2,2'-Azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)): Yields a green product upon oxidation [36]. |

| Specific Scavengers & Inhibitors | Validating the identity of ROS and elucidating generation pathways. | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD): Specifically scavenges O₂•⁻ [39].Sodium Azide (NaN₃): Scavenger of singlet oxygen (¹O₂) [39].Catalase: Decomposes H₂O₂. |