Point Source vs. Non-Point Source Pollution: A Comparative Analysis of Impacts, Assessment, and Control Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of point source (PS) and non-point source (NPS) pollution, addressing critical gaps in understanding their distinct characteristics, impacts, and management.

Point Source vs. Non-Point Source Pollution: A Comparative Analysis of Impacts, Assessment, and Control Strategies

Abstract

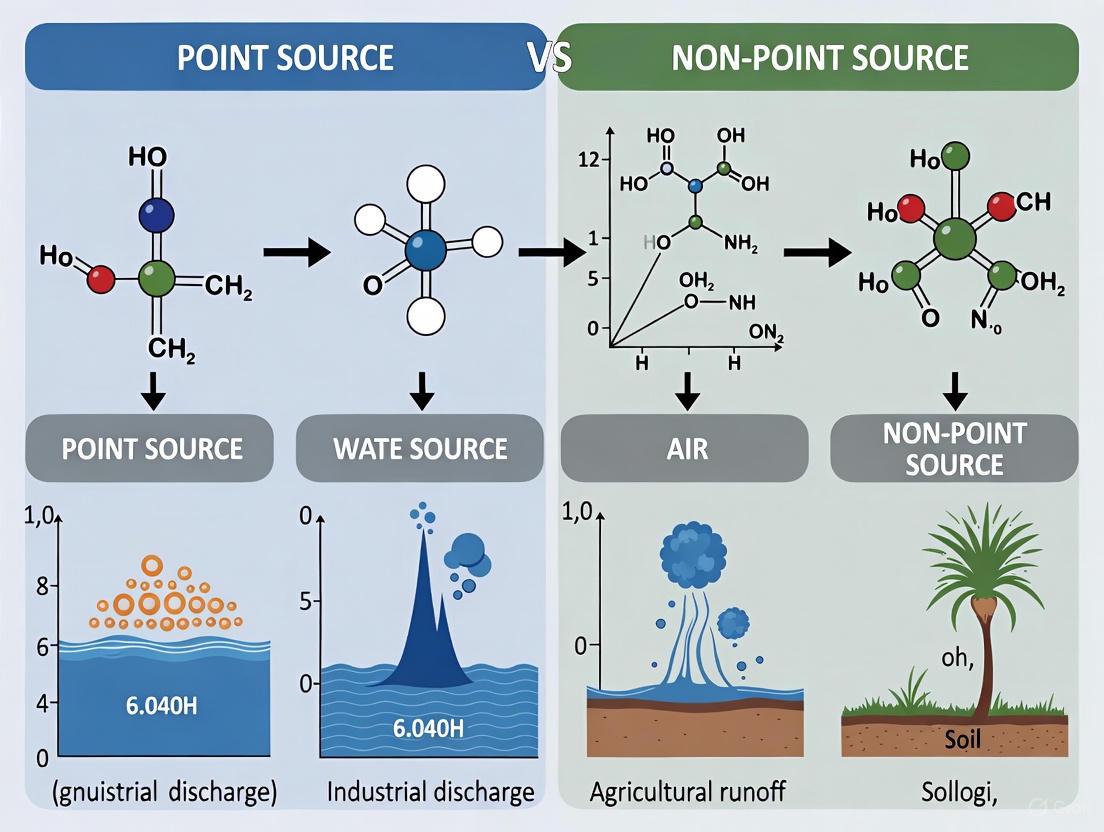

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of point source (PS) and non-point source (NPS) pollution, addressing critical gaps in understanding their distinct characteristics, impacts, and management. It explores the foundational definitions and pollution origins, contrasting single-identifiable discharges from industrial and sewage treatment plants with diffuse runoff from agricultural and urban landscapes. The content details advanced methodological frameworks for pollution assessment, including watershed-scale models like SWAT and HSPF, and investigates the unique challenges in controlling NPS pollution. Through validation and comparative case studies, such as those in the Chesapeake Bay and urban rivers, the article synthesizes evidence on the differential ecological and economic impacts of PS and NPS pollution. Finally, it outlines future directions for integrated pollution management, emphasizing the implications for environmental policy and sustainable watershed planning.

Defining the Sources: From Factory Pipes to Agricultural Runoff

Defining the Pollution Paradigm: A Comparative Framework

In environmental science and regulation, water pollution sources are fundamentally categorized by their origin and discharge characteristics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of point source and nonpoint source (NPS) pollution, focusing on their impacts, regulatory frameworks, and the methodologies used to research them. Understanding this distinction is critical for developing effective mitigation strategies and allocating scientific resources efficiently.

Point source pollution originates from any "discernible, confined, and discrete conveyance," including pipes, ditches, channels, tunnels, or vessels from which pollutants are discharged [1] [2]. The defining characteristic is its traceability to a single, identifiable location [3].

In contrast, nonpoint source (NPS) pollution comes from diffuse origins, not traceable to a single discharge point [1]. It is primarily caused by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground, picking up natural and human-made pollutants and depositing them into water bodies [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Point Source and Nonpoint Source Pollution

| Characteristic | Point Source Pollution | Nonpoint Source Pollution |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Single, identifiable source [4] [3] | Diffuse, from a wide area [1] [5] |

| Conveyance | Discernible, confined, discrete conveyance (e.g., pipe, ditch) [6] [2] | Overland flow and runoff [1] [7] |

| Regulatory Status | Primary target of federal permits (e.g., NPDES) [6] | Leading remaining cause of water quality problems; more difficult to regulate [1] |

| Example Sources | Factories, sewage treatment plants, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) [6] | Agricultural runoff, urban stormwater, atmospheric deposition [1] |

| Key Pollutants | Industrial chemicals, treated human waste, toxic effluents [6] | Excess fertilizers, herbicides, sediment, oil, grease [1] |

Quantitative Impact Assessment: Experimental Data and Findings

A comparative study of the East River (Dongjiang) in southern China provides robust, quantitative data on the relative contributions of these pollution types. The research utilized the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT), a physically-based hydrological and water quality model, to simulate and separate pollutant loads [8].

Table 2: Pollutant Load Contributions from Point and Nonpoint Sources in a Watershed Study

| Pollutant Type | Nonpoint Source (NPS) Contribution | Point Source (PS) Contribution | Dominant Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Loads (general) | >94% [8] | <6% [8] | Nonpoint Source |

| Mineral Phosphorus | ~50% [8] | ~50% [8] | Equal Contribution |

The study concluded that nonpoint source pollution was the dominant contributor to most nutrient loads in the studied basin. However, it also highlighted the significant role of point sources for specific pollutants like mineral phosphorus. The temporal analysis revealed that the critical period for NPS pollution occurs from the late dry season to the early wet season, while spatial mapping identified middle and downstream agricultural lands as critical source areas [8].

Experimental Protocol: Watershed Modeling with SWAT

The methodology from the cited study offers a replicable experimental framework for quantifying point and nonpoint source impacts [8].

1. Model Selection and Description: The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) is a physically-based, watershed-scale model developed by the USDA Agricultural Research Service. It simulates the terrestrial hydrological cycle, plant growth, soil erosion, sediment transport, and nutrient cycling (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) [8].

2. Input Data Preparation: The model requires extensive spatial and temporal data:

- Digital Elevation Model (DEM): To delineate the watershed and define flow paths.

- Land Use/Land Cover Data: To parameterize the spatial distribution of pollutant sources.

- Soil Data: To define hydrological soil groups and infiltration characteristics.

- Meteorological Data: Daily time-series of precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity.

- Point Source Data: Locations and daily loadings of pollutants from known point sources (e.g., industrial and municipal discharge records).

- Management Practices: Data on agricultural practices, such as fertilizer application rates and timing.

3. Model Calibration and Validation:

- Calibration: Use observed data (e.g., streamflow, sediment, and nutrient concentrations) from a historical period to adjust model parameters within acceptable ranges. The study used data from 1991-1994 for calibration [8].

- Validation: Run the calibrated model for a different time period without parameter adjustment and compare outputs to observed data to assess model performance. The study used data from 1995-1999 for validation [8].

4. Scenario Simulation and Analysis: Run the validated model with and without point source inputs to isolate and quantify the contribution of each source type to the total pollutant load at the watershed outlet.

Diagram 1: SWAT Model Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Research into pollution impacts relies on a suite of analytical and computational "reagent solutions." The following tools are essential for designing and executing studies in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pollution Impact Studies

| Tool/Solution | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrological/Watershed Models (e.g., SWAT) | Physically-based simulation of water, sediment, and pollutant transport at a watershed scale. Allows for source apportionment [8]. | Used to investigate PS and NPS processes in the East River study [8]. |

| Water Quality Index (WQI) | A single number derived from multiple water quality parameters to classify and compare water quality status simply and objectively [8]. | Allows for comparison of water quality among different locations and over time. |

| Geospatial Datasets | National-scale data on land use, hydrology, and anthropogenic activities used for large-scale contamination risk assessment [9]. | Enabled comparison of potential source water contamination across 100 U.S. cities [9]. |

| National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Data | Regulatory permit data that provides detailed information on regulated point source discharges, including location and effluent limits [6]. | Critical for identifying and modeling point source inputs in a study area. |

In water pollution research, contaminants are fundamentally categorized as originating from either point sources or non-point sources (NPS). This distinction is critical for developing effective monitoring, regulation, and mitigation strategies [10]. Point source pollution originates from a single, identifiable, and confined conveyance, such as a pipe from a factory or a sewage treatment plant [1] [11]. In contrast, non-point source pollution, the focus of this guide, is characterized by its diffuse origin, stemming from widespread land runoff, atmospheric deposition, and hydrologic modification rather than a discrete outlet [1] [12].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two pollution paradigms, emphasizing the complex methodologies required to study non-point source pollution. We present experimental data, modeling protocols, and essential research tools to equip scientists and environmental professionals in tackling the significant challenge NPS pollution poses to global water quality, which is cited as the leading remaining cause of water quality impairments in many regions [1] [13].

The following table summarizes the core differentiating attributes of point source and non-point source pollution, which dictate divergent research and management approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Point Source and Non-Point Source Pollution

| Characteristic | Point Source Pollution | Non-Point Source Pollution (Diffuse Runoff) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin & Definition | Discernible, confined, and discrete conveyance (e.g., pipe, ditch, channel) [1] [13]. | Diffuse sources without a single point of origin [12]. |

| Pollutant Pathways | Direct discharge from a specific outlet [11]. | Transported by rainfall/snowmelt moving over/through ground; atmospheric deposition [1] [12]. |

| Example Pollutants | Industrial process chemicals, treated/untreated sewage [10]. | Excess fertilizers, pesticides, oil/grease, sediments, bacteria from livestock, salt from irrigation [1] [13]. |

| Regulatory Framework | Explicitly regulated under Clean Water Act via permit systems (e.g., National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) [11]. | Largely unregulated by federal permit systems; managed through state-level programs, incentives, and voluntary Best Management Practices (BMPs) [14] [15] [11]. |

| Research & Monitoring Focus | Direct measurement at the point of discharge; compliance monitoring [11]. | Watershed-scale modeling, land-use analysis, water quality monitoring to infer sources, and effectiveness of landscape-scale interventions [16] [15]. |

Quantitative Comparisons: Pollutant Loads and Modeled Responses

Contribution to Water Quality Impairment

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicates that non-point source pollution is the predominant cause of water quality issues in the United States today. Specifically, of the assessed waterbodies across the nation where a source of impairment has been identified, NPS pollution contributes to 85% of impairments in rivers and streams and 80% of impairments in lakes and reservoirs [11]. This starkly contrasts with the more localized impact of point sources, which are more straightforward to identify and control.

Modeling the Response to Climate and Human Activities

Experimental modeling is crucial for quantifying NPS pollution loads and their drivers. A 2025 study on an agricultural watershed in China utilized the Soil and Water Assessment Tool Plus (SWAT+) model to disentangle the impacts of climate change and human activities on total nitrogen (TN) load [16].

Table 2: Quantified Contributions to Non-Point Source Total Nitrogen (TN) Load [16]

| Evolutionary Scenario (Period) | Contribution of Climate Change | Contribution of Human Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1998–2003 | 95.5% | 4.5% |

| 2003–2008 | 94.7% | 5.3% |

| 2008–2018 | 92.8% | 7.2% |

| 2018–2023 | 90.3% | 9.7% |

| Average across all scenarios | 93.6% | 6.4% |

The study found that while climate patterns (particularly precipitation) dominated the TN load contributions, the role of human activities has more than doubled over a 25-year period, indicating its growing influence [16]. Future projections using CMIP6 global climate models showed that TN load trends depend heavily on the socioeconomic pathway, with a consistent upward trend under the high-emission scenario SSP5-8.5, driven by agricultural land expansion [16].

Experimental Protocols for NPS Pollution Research

Watershed Modeling with SWAT+

The SWAT+ model is a widely used, public-domain tool for simulating water balance, sediment, and nutrient transport in watersheds.

- Objective: To quantify the impact of climate change and human activities on NPS pollution loads (e.g., total nitrogen) and project future changes under various scenarios [16].

- Methodology Workflow:

Key Data Inputs:

- Topography: Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to define the watershed and sub-basins.

- Land Use/Land Cover (LULC): Historical, current, and projected future maps.

- Soil Data: Soil type and properties across the watershed.

- Climate Data: Historical daily precipitation and temperature; future climate projections from General Circulation Models (GCMs) like those from CMIP6.

- Management Practices: Data on fertilizer application, tillage, and Best Management Practices (BMPs).

- Validation Data: Measured streamflow and water quality data (e.g., TN loads) for model calibration and validation [16].

Output Analysis: The calibrated model is run under different scenarios (e.g., changing climate only, changing land use only) to isolate and quantify the contributions of different drivers. Performance is often assessed with metrics like the coefficient of determination (R²), with values like 0.87 for streamflow and 0.71 for TN load indicating good model performance [16].

Spatial and Econometric Analysis

For large-scale regional studies, researchers employ statistical models to analyze panel data.

- Objective: To investigate the nonlinear impact and spatial spillover effects of socioeconomic factors (e.g., rural industrial integration) on agricultural NPS pollution, and the role of environmental regulations [17].

- Methodology Workflow:

- Key Data Inputs:

- NPS Pollution Measurement: Calculated emissions of total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and chemical oxygen demand (COD) from inventory analysis of multiple sources (fertilizer, livestock, rural waste) [17].

- Independent Variables: Indices for rural three-industry integration level, often constructed using methods like the entropy weight method based on dimensions like agricultural product processing income and leisure agriculture income [17].

- Moderating Variables: Data on different types of environmental regulations, classified as command-and-control, market-based, or public-voluntary [17].

- Control Variables: Data on economic development, industrial structure, technological level, etc.

- Model Specification: The study may employ a two-way fixed effects model to control for unobserved province and time effects, and a Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) to account for spatial dependence. A moderating effects model is used to test how environmental regulations alter the primary relationship of interest [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for NPS Pollution Research

| Research Tool / Solution | Primary Function in NPS Research |

|---|---|

| SWAT+ (Soil & Water Assessment Tool Plus) | A semi-distributed, physically-based watershed model used to simulate the long-term impact of land management practices on water balance, sediment, and agricultural chemical yields [16]. |

| CMIP6 Climate Data | Projections from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) General Circulation Models (GCMs) are used to force watershed models under future climate scenarios (e.g., SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5) [16]. |

| Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) | An econometric model that accounts for spatial autocorrelation in panel data, allowing researchers to estimate both direct effects and spatial spillover effects (indirect effects on neighboring regions) of drivers on NPS pollution [17]. |

| Environmental Regulation Indices | Quantitative indices constructed to represent the stringency of different types of environmental policies (command-control, market-based, public-voluntary), used to test their moderating effects [17]. |

| Best Management Practices (BMPs) | A suite of conservation practices, techniques, and structures (e.g., riparian buffers, cover crops, precision fertilization) that are modeled and evaluated for their efficacy in reducing NPS pollutant loads [16] [15]. |

| Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) | A regulatory framework that establishes the maximum amount of a pollutant a waterbody can receive and still meet water quality standards. It serves as a target for watershed-scale NPS pollution reduction plans [15]. |

Discussion and Research Outlook

The comparative study of pollution sources unequivocally shows that non-point source pollution presents a more formidable scientific and regulatory challenge than point source pollution due to its diffuse nature. The experimental data confirms that NPS pollution is highly sensitive to climatic drivers, but the increasing contribution from human activities underscores the need for proactive land and water management [16]. Furthermore, findings of spatial spillover effects indicate that pollution in one region can be influenced by the socioeconomic and regulatory activities in neighboring regions, necessitating inter-regional cooperation and policy coordination [17].

Future research will likely focus on refining integrated models that couple climate, hydrological, and socioeconomic factors at higher resolutions. The exploration of innovative financing mechanisms, such as those linking wastewater utilities with farm-based projects, and the precise quantification of the cost-effectiveness of various BMPs under different future scenarios will be critical for informing evidence-based policies to mitigate this pervasive environmental problem [14].

Within environmental science and policy, water pollution is fundamentally categorized into two distinct types based on its origin: point source and nonpoint source pollution. This classification is critical, as it dictates the entire regulatory and management approach for mitigating environmental impacts. Point source pollution originates from a single, identifiable location, such as a pipe or ditch [18]. In contrast, nonpoint source (NPS) pollution comes from diffuse origins, encompassing a wide area, and is primarily transported by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis for researchers and professionals, dissecting the key distinctions in the origin and regulation of these pollution types, which is essential for designing effective control strategies and remediation protocols.

Comparative Analysis of Origins and Characteristics

The core distinction between point and nonpoint source pollution lies in the nature of their discharge points, which directly influences their traceability, the composition of pollutants, and their environmental behavior.

Point Source Pollution: Discrete and Identifiable

- Origin: As defined in Section 502(14) of the Clean Water Act (CWA), a point source is "any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance" [1] [18]. This includes specific structures like pipes, ditches, tunnels, or vessels.

- Key Characteristics:

- Single Source: Emissions originate from one fixed, easily located point, such as a factory smokestack or a sewage treatment plant's discharge pipe [19] [10].

- High Traceability: The origin of the pollutant is easily identified, making it straightforward to establish accountability [20].

- Consistent Discharge: The pollution often occurs continuously or at regular intervals, allowing for consistent monitoring at the source [18].

- Plume Formation: In water bodies, point source pollution often creates a "plume," an area where the pollutant is most concentrated [19].

Nonpoint Source Pollution: Diffuse and Widespread

- Origin: Nonpoint source pollution is defined as any source of water pollution that does not meet the legal definition of a point source [1] [21]. It arises from land runoff, precipitation, atmospheric deposition, and drainage across a broad landscape [1].

- Key Characteristics:

- Multiple Diffuse Sources: Pollution originates from numerous, scattered locations, such as all the farms in a watershed or all the lawns in a suburban neighborhood [19] [20].

- Low Traceability: It is difficult or impossible to trace the pollution back to a single, specific origin, making accountability a significant challenge [20].

- Weather-Dependent Transport: The mobilization and transport of pollutants are directly linked to precipitation events; the volume and intensity of rainfall directly influence the amount of pollution washed into waterways [1].

- Complex Mixture: Runoff typically carries a complex mixture of pollutants, including excess fertilizers, pesticides, oil, grease, and sediment from various land uses [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the origin of each pollution type and its fundamental characteristics, which in turn dictate the regulatory response.

Diagram 1: Logical flow from pollution origin to characteristics and regulatory response.

Regulatory Frameworks and Control Methodologies

The fundamental differences in origin have led to the development of two starkly different regulatory frameworks in the United States, primarily under the Clean Water Act (CWA).

Point source pollution is primarily controlled through a direct, command-and-control regulatory system.

- Legal Basis: The CWA makes it unlawful to discharge any pollutant from a point source into waters of the United States without a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit [18].

- Permit Structure: The NPDES permit is a comprehensive legal document that sets specific limits on pollutants, mandates monitoring and reporting requirements, and stipulates special conditions for compliance [18].

- Technology and Water Quality Standards:

- Technology-Based Limits: These are uniform national standards based on the performance of available pollution control technologies (e.g., "Best Available Technology Economically Achievable" or BAT for existing industrial dischargers) [18].

- Water Quality-Based Limits: If technology-based limits are insufficient to protect a specific water body, more stringent limits are set based on the water quality standards for that river or lake [18].

- Enforcement: Permittees must self-monitor and report compliance. Regulatory agencies perform periodic inspections, and violations can lead to enforcement actions, including penalties [18].

The regulation of nonpoint source pollution is more complex and less direct, relying on a combination of federal guidance, state-led programs, and voluntary measures.

- Legal Basis: Unlike point sources, there is no federal permit system for nonpoint source pollution. The primary legal basis for addressing NPS pollution is Section 319 of the CWA [21]. This section provides grants and guidance to states to develop and implement nonpoint source management programs [21].

- Core Strategy: Best Management Practices (BMPs): Control relies on the implementation of BMPs, which are practices, prohibitions, or procedures designed to prevent or reduce water pollution [20]. Examples include:

- Implementation Challenges: The 319 program is largely non-regulatory. States are not required to implement their NPS management plans, and there are no federal enforcement mechanisms against individual nonpoint source polluters [21]. Success hinges on voluntary adoption, education, and funding incentives.

Table 1: Side-by-Side Comparison of Point Source and Nonpoint Source Pollution

| Feature | Point Source Pollution | Nonpoint Source Pollution |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Single, identifiable location (e.g., pipe, factory) [20] | Diffuse, widespread sources (e.g., farmland, city streets) [20] |

| Traceability | Easily traceable to a specific source [20] | Difficult or impossible to trace to a specific origin [20] |

| Primary U.S. Regulation | Clean Water Act, NPDES Permit Program [18] | Clean Water Act, Section 319 (non-regulatory) [21] |

| Key Control Methods | Technology-based effluent limits, NPDES permits, enforcement actions [18] | Best Management Practices (BMPs), education, voluntary programs [20] |

| Primary Pollutants | Industrial chemicals, untreated sewage, thermal pollution, specific toxic effluents [18] | Excess fertilizers & pesticides, oil/grease, sediment, pathogens from livestock [1] |

| Relative Ease of Control | Easier to monitor and regulate due to defined source [19] | More difficult and costly to control due to diffuse nature [19] [20] |

The following workflow visualizes the stark contrast in the regulatory pathways for the two pollution types.

Diagram 2: Contrasting regulatory and management pathways for point and nonpoint sources.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Analytical Methods

Investigating and quantifying pollution impacts requires a suite of analytical techniques and reagents. The following table details essential tools for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Analytical Methods

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Pollution Research |

|---|---|

| BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) Analysis Kits | A key metric for assessing water quality; measures the amount of oxygen consumed by microorganisms to decompose organic waste in water [18]. High BOD indicates severe organic pollution. |

| Nutrient Analysis Reagents (for Nitrogen & Phosphorus) | Used with colorimetric methods to quantify concentrations of nitrates and phosphates, the primary nutrients driving eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems [21]. |

| Fecal Coliform Test Kits | Contains selective growth media to detect and enumerate bacteria from fecal matter (e.g., E. coli), indicating contamination from sewage or animal waste [18]. |

| Heavy Metal Test Kits (e.g., for Lead, Mercury) | Includes reagents for techniques like Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to detect toxic metal contaminants from industrial and urban runoff [21]. |

| Turbidity and Total Suspended Solids (TSS) Kits | Measures the cloudiness of water (turbidity) and the dry-weight of suspended particles (TSS), crucial for assessing sediment pollution from erosion and construction [18]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Used to concentrate and clean up complex water samples (e.g., urban runoff) before analysis for pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and other organic pollutants via GC-MS or LC-MS [1]. |

| Sampling Equipment (Automatic Samplers, Flow Meters) | Enables the collection of representative water samples, both discrete and flow-weighted, which is critical for accurately characterizing nonpoint source pollution loads during storm events [1]. |

The dichotomy between point and nonpoint source pollution is a cornerstone of environmental management. While significant progress has been made in controlling point sources through the NPDES system, nonpoint source pollution remains the nation's largest cause of water quality problems [1]. The diffuse nature of NPS pollution makes it resistant to traditional regulatory approaches, necessitating a shift towards landscape-scale management, innovative monitoring technologies, and integrated policies that incentivize conservation practices across agricultural, urban, and industrial sectors. For researchers and policymakers, understanding this fundamental distinction is the first step in designing targeted, effective strategies to restore and protect water resources.

In environmental science, pollution sources are fundamentally categorized as either point sources or non-point sources (NPS), a distinction critical for both regulation and research design. Point source pollution originates from a single, identifiable location, such as a pipe or ditch from an industrial facility or wastewater treatment plant [10] [22]. Its discrete nature makes it relatively straightforward to monitor, regulate, and trace. In contrast, non-point source pollution comes from diffuse origins, with no single identifiable point of entry [11]. It is primarily carried by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground, collecting pollutants from vast areas and depositing them into waterways [10] [22]. This diffuse characteristic makes NPS pollution more complex to quantify, model, and mitigate.

The comparative analysis of pollutant profiles from these two sources is essential for developing targeted mitigation strategies. This guide provides a structured, data-driven comparison for researchers, focusing on the distinct chemical profiles, transport mechanisms, and advanced methodologies for assessing pollution impacts.

Comparative Pollutant Profiles and Environmental Impact

The nature and origin of pollutants directly influence their chemical profiles, environmental behavior, and ultimate impact on ecosystems and human health. The tables below provide a detailed comparison of the defining characteristics and pollutant constituents from each source.

Table 1: Characteristics and Sources of Point Source and Non-Point Source Pollution

| Feature | Point Source Pollution | Non-Point Source Pollution |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Single, identifiable source (e.g., pipe, factory) [10] [22] | Diffuse, multiple sources across a landscape [11] |

| Traceability | Easily traceable to a specific discharge point [22] | Difficult or impossible to trace to a single origin [11] [22] |

| Primary Regulators | Industrial facilities, Wastewater treatment plants, Power plants [22] | Agricultural operations, Urban runoff, Forestry activities [10] [22] |

| Regulatory Framework | Governed by permits (e.g., NPDES under the Clean Water Act) [22] | Largely voluntary & incentive-based (e.g., EPA's Section 319 Program) [11] [22] |

| Key Transport Mechanism | Direct discharge via confined conveyances [11] | Stormwater runoff and snowmelt [10] [11] |

Table 2: Common Pollutants and Their Documented Impacts

| Pollutant Category | Point Source Profile | Non-Point Source Profile | Primary Documented Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | Often from sewage treatment plants (Nitrogen, Phosphorus) [22] | Fertilizer runoff (Nitrogen, Phosphorus) [22] | Eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion (e.g., Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone) [22] |

| Pathogens | Bacteria and viruses from sewage discharges [22] | Bacteria from animal and human waste (e.g., pets, livestock, septic systems) [11] [22] | Waterborne diseases, recreational hazards, shellfish bed closures [22] |

| Toxic Organic Chemicals | Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) from manufacturing [10], solvents, pesticides from industrial discharges [22] | Pesticides and herbicides from agricultural and urban runoff [22] | Bioaccumulation in food webs [23]; PCBs are legacy contaminants affecting species like salmon and orcas [23] |

| Heavy Metals | Lead, mercury, cadmium, and other metals from industrial and mining operations [22] | Oil, grease, and heavy metals from urban stormwater [22] | Induction of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease in humans [24]; accumulation in bivalves and harbor seals [23] |

| Other | Thermal pollution from power plant cooling systems [22] | Sediments from construction sites and eroded landscapes [22] | Habitat destruction; sedimentation smothers aquatic habitats [22]; thermal discharge alters temperature-sensitive ecosystems [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Pollution Research and Modeling

A critical challenge in environmental research, particularly for NPS pollution, is accurate pollution profiling and load prediction. The following section outlines established and emerging methodological approaches.

Modeling Non-Point Source Pollution in Data-Limited Scenarios

A recent study systematically evaluated three widely used NPS modeling approaches using a large-scale field monitoring dataset from an urban area in China [25]. The performance and utility of these models were assessed based on a multi-criteria framework including accuracy, generalizability, robustness, and cost-efficiency.

Experimental Workflow: The research followed a structured protocol applicable to many urban NPS studies, as visualized below.

Key Findings from the Comparative Modeling Study [25]:

- Improved Export Coefficient Method (IECM): An empirical statistical model that achieved high accuracy for Total Nitrogen (TN) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) (R² > 0.7) but showed significant risks of overfitting due to collinearity among predictor variables.

- Random Forest (RF) Regression: A machine learning model that predicted COD, TN, NH₃-N, and Total Phosphorus (TP) effectively (R² > 0.6) but struggled with predicting Total Suspended Solids (TSS) loads. It was identified as a robust and practical approach for data-limited scenarios.

- Storm Water Management Model (SWMM): A physical process-based model that failed to deliver reliable predictions even after auto-calibration, underscoring its limitations in situations where detailed drainage network data and user expertise are lacking.

- Factor Contribution Analysis: The study identified the antecedent dry period, rainfall depth, and land use as key predictors. It further revealed that nitrogen-related pollutants were more influenced by dry deposition, while phosphorus was more affected by rainfall-triggered wash-off processes.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models for Pollution Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

| Item / Methodology | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Improved Export Coefficient Method (IECM) | Empirical Statistical Model | Establishes multiple linear regression relationships between pollution load and influential factors (e.g., land use, rainfall) for rapid nutrient profiling [25]. |

| Random Forest (RF) Regression | Machine Learning Algorithm | Predicts pollution load by considering parameter combinations and interactions; resistant to overfitting and useful for identifying key variables [25]. |

| Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) | Physical Process-Based Model | Simulates the hydrology and hydraulics of stormwater runoff; requires extensive input data but can map spatio-temporal distribution of pollutants [25]. |

| National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) | Regulatory Database | Provides permitted discharge data for point sources, serving as a critical data source for monitoring and compliance audits [22]. |

| Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) Analysis | Analytical Chemistry Method | Quantifies concentrations of these legacy toxic organic chemicals in water, sediment, and biota to track long-term trends and bioaccumulation [23]. |

| Mussel Watch Program | Biomonitoring Protocol | Uses bivalve shellfish as sentinel organisms to monitor spatial and temporal trends of metal and organic contaminants in coastal waters [23]. |

Mechanistic Pathways to Human Health Impacts

Pollutants from both point and non-point sources can enter the human body through ingestion of contaminated water or food, inhalation, or dermal contact. A key mechanism by which many toxicants exert their effects is the induction of oxidative stress, a common initiating event for multiple non-communicable diseases [24]. The following diagram illustrates the cascade from exposure to cardiovascular and neurodevelopmental outcomes, as documented in the literature.

Supporting Evidence for Mechanistic Pathways:

- Heavy Metals: Cadmium, lead, and arsenic can trigger cardiovascular diseases by producing oxidative stress via mechanisms such as Fenton reactions and disruption of antioxidant responses, leading to vascular damage and endothelial dysfunction [24].

- Air Pollution and Neurodevelopment: A systematic review of 26 publications found that prenatal and childhood exposure to outdoor air pollution (e.g., particulate matter) is associated with structural and functional brain variations in children, as measured by MRI [26]. The direction and magnitude of findings were inconsistent, but the evidence suggests pollution acts as a developmental neurotoxicant.

- Organic Chemicals: PCBs, PBDEs, and pesticides can induce oxidative stress and inflammation, increasing the risk for cancer, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis. There is also preclinical and clinical evidence that these chemicals can lead to dysregulation of the endogenous circadian clock, a known risk factor for cardiovascular diseases [24].

The comparative analysis of pollutant profiles from point and non-point sources reveals fundamental differences that demand distinct research and mitigation strategies. Point source pollutants, characterized by their identifiable origin and often chemical-specific nature, are amenable to direct regulation and end-of-pipe treatment technologies. In contrast, the diffuse and variable nature of non-point source pollution, dominated by nutrients, sediments, and pesticides, requires a landscape-level approach utilizing advanced modeling and best management practices.

For researchers, the choice of investigative tool is critical. While physical process-based models offer mechanistic depth, machine learning models like Random Forest currently provide a more practical and robust solution for pollution profiling in data-limited environments [25]. Future research must continue to integrate these modeling approaches with advanced biomonitoring and mechanistic toxicology to fully elucidate the complex pathways from pollutant release to human health impacts, thereby informing more effective and targeted environmental protection policies.

Tools for Assessment: Monitoring and Modeling Pollution Pathways

In water quality research and environmental management, accurately distinguishing and quantifying the impacts of point source (PS) and non-point source (NPS) pollution is a fundamental challenge. Non-point source pollution, which originates from diffuse sources such as agricultural runoff and atmospheric deposition, is particularly difficult to manage due to its complex mechanisms and dependence on hydrological events, land use practices, and climatic conditions [27] [28]. Watershed-scale simulation models have emerged as indispensable tools for investigating these complex processes, enabling researchers and policymakers to predict pollutant loads, identify critical source areas, and evaluate the potential effectiveness of various intervention strategies [29] [30]. Among the most prevalent watershed models are the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT), the Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN (HSPF), and the Generalized Watershed Loading Functions (GWLF). Each offers distinct approaches, capabilities, and data requirements, making them suitable for different research contexts and objectives. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three modeling frameworks, focusing on their application in PS versus NPS pollution research, supported by experimental data, methodological protocols, and visualization tools to assist environmental researchers and scientists in selecting the appropriate model for their specific investigations.

Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)

SWAT is a semi-distributed, physically-based hydrological model designed to simulate water quality and quantity, predict the impacts of land management practices, and assess environmental changes over long time periods in large, complex watersheds [29] [28]. It operates on a continuous daily time step and divides a watershed into subbasins, which are further subdivided into Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs) - unique combinations of land use, soil type, and slope [29]. This spatial discretization allows SWAT to capture heterogeneity within the watershed. The model simulates the hydrological cycle based on the water balance equation and incorporates detailed processes for sediment erosion, nutrient cycling (nitrogen and phosphorus), and pollutant transport [28]. Its comprehensive process representation makes it a powerful tool for studying non-point source pollution, particularly from agricultural landscapes.

Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN (HSPF)

HSPF is a comprehensive, continuous, and physically-based model that simulates watershed hydrology and water quality for both conventional and toxic organic pollutants [31] [32]. It represents the watershed using interconnected land segments (pervious and impervious) and channel/reach segments, allowing for integrated modeling of land and water processes. HSPF is renowned for its detailed simulation of in-stream water quality processes and its ability to model a wide array of pollutants. It has been widely used in conjunction with the BASINS (Better Assessment Science Integrating Point and Non-Point Source) framework for efficient land and water resource management [31]. Studies have shown that HSPF can effectively simulate streamflow, sediment, and nutrient loadings, sometimes with higher accuracy than SWAT in certain watershed settings [32].

Generalized Watershed Loading Functions (GWLF)

GWLF is a combined distributed/lumped parameter, continuous simulation model that strikes a balance between empirical and complex process-based models [29] [33]. Developed at Cornell University, it simulates runoff, sediment, and nutrient transport with a daily time step, but typically provides monthly or annual output. Its key advantage lies in its relatively simple input data requirements and user-friendly operation compared to more complex models like SWAT and HSPF [33]. GWLF identifies surface loading from different land covers in a distributed manner but lacks spatial conception and channel routing components, treating subsurface processes with lumped parameters for the entire watershed [29]. The model has been endorsed for use in Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) development and is available in enhanced versions such as GWLF-E and MapShed, which offer improved accessibility and functionality [33].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of SWAT, HSPF, and GWLF Models

| Characteristic | SWAT | HSPF | GWLF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Structure | Semi-distributed, physically-based | Physically-based, continuous | Combined distributed/lumped parameter, semi-process-based |

| Spatial Discretization | Subbasins and Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs) | Land segments (pervious/impervious) and channel reaches | Lumped parameter for groundwater; distributed for land cover |

| Temporal Scale | Continuous daily time step | Continuous time step | Daily time step (output often monthly/annual) |

| Primary Developer | USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | Cornell University |

| Theoretical Basis | Water balance equation; modified USLE (MUSLE) for sediment | Comprehensive hydrological and water quality processes | SCS-CN for runoff; USLE for erosion; lumped groundwater reservoir |

| Typical Applications | Hydrologic assessments, pollutant assessments, climate change impacts | TMDL development, urban and mixed-use watershed simulation | Regional screening, TMDL development, watershed planning |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Experimental Data and Quantitative Results

Simulation of Hydrology, Sediment, and Nutrients

Direct comparisons of SWAT and GWLF in two contrasting Chinese catchments (humid Tunxi and semi-arid Hanjiaying) revealed that both models could satisfactorily simulate monthly streamflow, sediment yield, and total nitrogen loads [29]. Statistical measures such as the coefficient of determination (R²), Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), percent bias (PBIAS), and RMSE-observations standard deviation ratio (RSR) were used for performance evaluation. The study concluded that while SWAT performed better for detailed temporal representations, GWLF could produce more accurate long-term average values of observed data, making it a viable alternative in data-scarce regions [29].

A comparison between SWAT and HSPF in the Polecat Creek watershed (Virginia, USA) demonstrated that both models could effectively simulate streamflow, sediment, and nutrient loadings [32]. However, HSPF exhibited superior accuracy in capturing hydrology and water quality components at all monitoring sites within the watershed, with annual runoff errors ranging from 1.7% to 14.7% [32]. In contrast, SWAT tended to underestimate total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN) and total phosphorus (TP) loads, indicating potential discrepancies in its representation of fertilizer application impacts [32].

Spatial Analysis and Critical Source Area Identification

SWAT's semi-distributed structure facilitates the identification of Critical Source Areas (CSAs) - specific areas within a watershed that contribute disproportionately high pollutant loads. A study in Jincheng City utilized SWAT with dynamic land use updates (SWAT-LUT) to analyze nitrogen pollution sources [27]. The model quantified contributions from various sources, revealing a significant shift between 1997 and 2022: atmospheric deposition was the primary source (39.8%) in 1997, but by 2022, nitrogen fertilizer application (35.6%) became dominant due to agricultural expansion [27]. This type of spatiotemporal analysis is crucial for targeted NPS pollution management.

Performance in Data-Scarce Regions and Specialized Conditions

The application of GWLF is particularly advantageous in data-scarce regions or for projects with limited resources, as it requires simpler input data compared to SWAT and HSPF [29] [33]. SWAT has also been successfully adapted for specialized hydrological conditions. For instance, in the depression-dominated Red River of the North Basin, a modified SWAT approach that incorporated surface depressions demonstrated significant improvement in simulating surface runoff and associated water quality, with NSE values increasing by 30.4% and 19.6% for calibration and validation periods, respectively [34].

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Performance Metrics from Comparative Studies

| Study / Model Comparison | Performance Metric | Streamflow | Sediment | Total Nitrogen (TN) | Total Phosphorus (TP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWAT vs. GWLF [29] | R² / NSE (Monthly) | Good performance for both models | Good performance for both models | Good performance for both models | Not Reported |

| SWAT vs. HSPF (Polecat Creek) [32] | Annual Runoff Error | HSPF: 1.7% - 14.7%SWAT: Underestimation | Not Specified | SWAT underestimated TKN | SWAT underestimated TP |

| SWAT in Depression-Based Basins [34] | NSE Improvement (Calibration/Validation) | 30.4% / 19.6% improvement with depression-oriented scenario | Improved with depression-oriented scenario | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| HSPF for BOD in Nakdong River [31] | R² (Flow Rate) | 0.71 - 0.93 | - | - | - |

| BOD Difference (Simulated vs. Measured) | - | - | 0.5% - 20% | - |

Experimental Protocols for Model Application

Standardized Workflow for Watershed Modeling

Applying SWAT, HSPF, or GWLF to a comparative study of PS and NPS pollution requires a systematic approach. The following protocol outlines the key steps, integrating best practices from the literature.

- Problem Definition and Scope: Precisely define the research questions. Determine the specific pollutants of interest (e.g., sediment, nitrogen, phosphorus, BOD), the required temporal resolution (daily, monthly, annual), and the spatial scale of the analysis (e.g., identifying CSAs versus watershed-level loads) [27] [28].

- Watershed Delineation and Data Collection: Delineate the watershed boundary and its internal sub-units (subbasins, HRUs) using a Digital Elevation Model (DEM). Assemble all necessary input data, which is a critical factor in model selection [35] [30].

- Model Setup and Configuration: Build the model by integrating all spatial and temporal data. This includes defining land use/land cover (LULC), soil types, weather data (precipitation, temperature), and point source discharge locations if applicable [27] [28]. For SWAT, this involves creating HRUs; for HSPF, defining land segments and reaches; and for GWLF, defining land use areas and lumped parameters.

- Model Calibration and Validation: This is a crucial step for ensuring model reliability. Split the observed data into two periods: calibration and validation.

- Calibration: Manually or automatically adjust key model parameters within plausible ranges to minimize the difference between simulated and observed data (e.g., streamflow, sediment, nutrients) [34]. Use statistical metrics like R², NSE, PBIAS, and RSR to evaluate goodness-of-fit [29].

- Validation: Run the model with the calibrated parameters using an independent dataset (not used in calibration) to assess the model's predictive capability and robustness [32].

- Scenario Analysis and Simulation: Run the calibrated and validated model to simulate various management or future scenarios. Examples include:

- LULC Change: Evaluating the impact of historical or projected land use change on NPS pollution [27] [28].

- Best Management Practices (BMPs): Assessing the effectiveness of BMPs like filter strips or reduced fertilizer application in reducing pollutant loads [31].

- Climate Change: Investigating how changing climate patterns may affect hydrology and water quality.

- Interpretation and Reporting: Analyze the model outputs to draw conclusions about PS and NPS pollution contributions, identify primary sources, and provide science-based recommendations for watershed management.

Protocol for a Comparative Study of PS vs. NPS Contributions

To specifically investigate the relative impacts of PS and NPS pollution using these models, the following focused protocol is recommended:

- Base Scenario: Run a calibrated model for a baseline period, simulating total pollutant loads at the watershed outlet.

- PS Exclusion Scenario: Run the model again, setting all point source discharges (e.g., from wastewater treatment plants) to zero. The resulting load represents the contribution from NPS pollution alone.

- NPS Isolation Scenario: Some models allow for the "switching off" of specific NPS processes. Alternatively, the NPS contribution can be estimated as the difference between the total load (Base Scenario) and the PS load (from monitoring or model output).

- Source Apportionment: Quantify the percentage contribution of PS and NPS to the total load. Spatially explicit models like SWAT can further break down NPS contributions by land use type (e.g., agriculture, urban) or subbasin [27].

Successful implementation of watershed models requires a suite of data inputs and computational tools. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for experiments in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Watershed Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function/Description | Relevance to Model Application |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | A digital representation of ground surface topography. | Fundamental for watershed delineation, defining stream networks, and calculating slope. Required by all three models. |

| Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Data | Spatial datasets classifying earth's surface into types (e.g., forest, agriculture, urban). | Used to define runoff and pollutant generation characteristics for different areas. Critical for simulating NPS pollution. Required by all models [27] [28]. |

| Soil Data (e.g., SSURGO/FAO) | Spatial datasets of soil properties (texture, hydrologic group, organic matter). | Determines infiltration rates, water holding capacity, and erosion potential. Required by SWAT and HSPF; used in GWLF for erosion calculations [29]. |

| Meteorological Time Series | Daily data for precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity. | The primary driver of hydrological processes and NPS pollution. Required by all models. |

| Streamflow & Water Quality Data | Time-series measurements of discharge, sediment concentration, and nutrient levels at gauging stations. | Absolute necessity for model calibration and validation. Used to assess model accuracy and performance [29] [32]. |

| Point Source Discharge Data | Location, flow rate, and pollutant concentration data for wastewater discharges. | Essential for accurately separating PS and NPS contributions in a watershed. Can be input into all models [30]. |

| GIS Software (e.g., QGIS, ArcGIS) | Geographic Information System for spatial data management, analysis, and visualization. | Used for pre-processing spatial data (delineation, LULC/soil overlay) and post-processing model results. SWAT has QSWAT; GWLF has MapShed [33] [30]. |

| Calibration & Uncertainty Analysis Tools (e.g., SWAT-CUP, PEST) | Software for automating parameter sensitivity analysis, calibration, and quantifying uncertainty. | Increases the efficiency and rigor of model calibration. Available for SWAT and HSPF, but less common for GWLF [34] [30]. |

The selection of an appropriate watershed model (SWAT, HSPF, or GWLF) for a comparative study of point source and non-point source pollution is not a one-size-fits-all decision. It depends heavily on the specific research objectives, data availability, and the required level of process detail.

SWAT is the most suitable model for projects requiring spatially detailed identification of Critical Source Areas (CSAs) and for long-term continuous simulations in predominantly agricultural watersheds. Its balance of process representation and usability has made it a widely accepted tool in the scientific and policy-making community [29] [30]. However, it requires significant input data and may be less suitable for data-scarce regions or for modeling complex in-stream chemical processes.

HSPF should be selected when the research demands highly accurate simulation of hydrology and in-stream water quality processes, including toxic organics. It has been shown to outperform SWAT in some comparative studies [32]. Its main drawback is its complexity and steep learning curve, requiring expert knowledge for proper calibration and application.

GWLF offers an excellent alternative for regional screening, rapid assessment, and studies in data-scarce regions. Its simpler structure and lower input data requirements make it a user-friendly and efficient tool for estimating average annual loads and for situations where the detailed data required for SWAT or HSPF are unavailable [29] [33]. Its limitations include the lack of spatial routing and more simplified process representations.

In conclusion, the choice between SWAT, HSPF, and GWLF should be guided by a clear understanding of the trade-offs between model complexity, data requirements, and the specific questions driving the research on point and non-point source pollution. By leveraging the experimental protocols and comparative data presented in this guide, researchers can make an informed decision and robustly apply these powerful modeling frameworks to advance water quality science and management.

The SWAT and PLUS Integrated Model for Future Risk Projection

The comparative study of point source (PS) versus non-point source (NPS) pollution impacts represents a critical frontier in environmental research, requiring advanced modeling capabilities to project future risks under changing climatic and land use conditions. Non-point source pollution, characterized by its diffuse nature and complex transport mechanisms, has progressively become the primary cause of deteriorating water quality in aquatic environments worldwide [27]. Unlike point source pollution, which originates from identifiable locations such as industrial and municipal discharge pipes, NPS pollution stems from widespread sources including agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition, and urban stormwater, making it significantly more challenging to quantify, monitor, and control [27]. The integration of the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT+) and the Patch-generating Land Use Simulation (PLUS) model provides researchers with a powerful coupled framework to simulate the interdependent dynamics of land use change and hydrological processes, enabling sophisticated projection of future pollution scenarios.

The SWAT+ model improves upon its predecessor by incorporating a more flexible spatial representation of interactions and processes within a watershed, including decision tables that allow for the specification of different land use management activities and scenarios [36] [37]. This restructuring facilitates the simulation of complex environmental processes, including the distinction between upland regions and floodplains, providing a more detailed and realistic representation of hydrological processes [36]. When combined with the PLUS model's capability to project future land use evolution, this integrated approach offers unprecedented capacity for analyzing how expanding agricultural land, urbanization, and climate change collectively influence future pollution risks [27]. This comparative guide objectively evaluates the performance of this integrated modeling framework against alternative approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies to assist researchers in selecting appropriate tools for PS and NPS pollution impact studies.

Model Fundamentals: SWAT+ and PLUS Architectures

SWAT+ Model Structure and Capabilities

The SWAT+ model represents a completely revised version of the SWAT model, featuring an object-based code structure and relational input files that enhance model maintenance, future modifications, and collaboration [37]. This ecohydrological model operates as a semi-distributed, continuous-time process simulator that divides watersheds into subbasins and further into Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs) based on unique soil, land use, and slope characteristics [38] [39]. The model's foundation rests on the water balance equation, expressed as:

[ SWt = SW0 + \sum{i=1}^{t}(R{day} - Q{surf} - Ea - W{seep} - Q{gw}) ]

Where (SWt) represents the final soil water content, (SW0) is the initial soil water content, (R{day}) is precipitation, (Q{surf}) is surface runoff, (Ea) is evapotranspiration, (W{seep}) is water entering the vadose zone, and (Q_{gw}) is groundwater discharge [39].

For sediment and nutrient simulation, SWAT+ incorporates the Modified Universal Soil Loss Equation (MUSLE) to estimate sediment yield:

[ Sed = 11.8 \times (Q{surf} \times q{peak} \times Area{hru})^{0.56} \times K{USLE} \times C{USLE} \times P{USLE} \times LS{USLE} \times C{FRG} ]

Where (Q{surf}) is surface runoff volume, (q{peak}) is peak runoff rate, (Area_{hru}) is HRU area, and the remaining factors represent soil erodibility, cover management, support practice, topographic, and coarse fragment components, respectively [39].

PLUS Model Framework for Land Use Projection

The PLUS model is a land use simulation framework that combines a rule-mining mechanism based on land expansion analysis strategy with a multi-type random patch seeds cascade based on cellular automata [27]. This dual approach enables the model to precisely simulate the evolution of multiple land use types under complex competition and interaction scenarios. The model leverages historical land use transition patterns to project future spatial configurations, making it particularly valuable for assessing how anthropogenic activities might alter landscape patterns and subsequently affect NPS pollution generation and transport. The integration of PLUS with SWAT+ through the SWAT-Land Use Update Tool (SWAT-LUT) allows for dynamic updating of multi-year land use data into the SWAT model database, facilitating the investigation of pollution sources under different LULC scenarios [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated SWAT+ and PLUS Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for integrated SWAT+ and PLUS modeling, highlighting the sequential processes and feedback mechanisms essential for future risk projection:

Integrated SWAT+ and PLUS Modeling Workflow

The experimental protocol for implementing the coupled SWAT+ and PLUS framework involves multiple structured phases:

Data Collection and Preparation: Researchers assemble spatial datasets including digital elevation models (DEM), soil maps, land use/land cover (LULC) data, climate records, and water quality measurements. For example, studies may utilize high-resolution DEMs (5×5 m) from national geographic information institutes, soil texture maps from soil information systems, and daily weather data from meteorological monitoring stations [39].

Land Use Change Projection: Historical land use transitions are analyzed to derive development rules, which the PLUS model employs to project future LULC scenarios. In the Jincheng City case study, researchers used PLUS to forecast land use evolution from 2022 to 2032, revealing continued expansion of agricultural land at slightly decelerated paces [27].

SWAT+ Model Configuration: The watershed is delineated into subbasins and HRUs using QSWAT+ within QGIS. Two model configurations are typically constructed: a static model (SWAT-UNI) using single-year LULC data, and a dynamic model (SWAT-MULTI) incorporating time-varying LULC data from PLUS projections [27].

Model Calibration and Validation: Parameter sensitivity analysis is performed followed by sequential uncertainty fitting using algorithms such as SUFI-2 and Dynamically Dimensioned Search (DDS). Model performance is assessed using statistical metrics including Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE), with successful applications achieving NSE values exceeding 0.82 during calibration periods and remaining above 0.76 during validation [36] [27].

Pollution Source Analysis and Scenario Projection: The calibrated integrated model simulates current and future pollution loads under different climate and land use scenarios, quantitatively distinguishing between point and non-point sources and their respective contributions to total pollutant loads.

Performance Assessment Methodologies for Hydro-climatic Extremes

For assessing model performance specifically for hydro-climatic extremes, researchers have developed specialized protocols that focus on the accurate representation of both high-flow (flood) and low-flow (drought) conditions [38]. These methodologies involve:

- Extreme Flow Separation: Observed streamflow records are processed to isolate extreme events using peak-over-threshold or annual maxima approaches, with particular emphasis on comparing simulated versus observed peak flows.

- Performance Metrics for Extremes: In addition to standard metrics (NSE, R²), extreme-focused assessments employ additional indicators including relative error in flood volume, peak flow timing error, and low flow duration discrepancies.

- Climate Scenario Integration: Future climate projections from CMIP6 models are incorporated to evaluate model performance under altered climatic conditions, with particular attention to bias correction of extreme precipitation events [38] [39].

Comparative Performance Analysis

SWAT+ Software and Calibration Tool Performance

The selection of calibration tools significantly impacts SWAT+ model performance, particularly for streamflow simulation. Recent comparative studies have evaluated the effectiveness of various calibration platforms:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SWAT+ Calibration Tools [36]

| Calibration Tool | Algorithm | Monthly Calibration (NSE) | Monthly Calibration (KGE) | Daily Validation (NSE) | Daily Validation (KGE) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWAT+ Toolbox | SUFI-2, DDS | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.78 | Limitations in baseflow representation |

| R-SWAT | SUFI-2, DDS | Lower than Toolbox | Lower than Toolbox | Lower than Toolbox | Lower than Toolbox | Higher uncertainty in parameter estimation |

| IPEAT+ | Built-in optimization | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | No intuitive graphical interface |

The superiority of SWAT+ Toolbox was demonstrated in a rural watershed study in southern Brazil, where it achieved better accuracy in both monthly calibration and daily validation compared to R-SWAT when using the same algorithms (SUFI-2 and DDS) and observational data [36]. However, both tools exhibited limitations in representing baseflow, and the uncertainty analysis emphasized the need for higher-quality input data, particularly regarding soil characterization [36].

Point Source vs. Non-point Source Pollution Contributions

The integrated SWAT+ and PLUS framework enables precise quantification of different pollution sources, revealing significant shifts in dominant contributors over time:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Pollution Sources in Jincheng City (1997-2022) [27]

| Pollution Source | 1997 Contribution (%) | 2022 Contribution (%) | Change Trend | Critical Control Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric Deposition | 39.8 | Decreased | Decreasing | Autumn and winter seasons |

| Nitrogen Fertilizer Application | 29.8 | 35.6 | Increasing | Crop growing season (March-September) |

| Soil Nitrogen Reservoirs | 21.4 | Second highest | Increasing | Autumn and winter seasons |

| Other Sources | 9.0 | Not specified | Variable | Season-dependent |

The analysis reveals a fundamental shift in nitrogen pollution dynamics over the 25-year period, with nitrogen fertilizer application surpassing atmospheric deposition to become the dominant contributor to total nitrogen load in water bodies by 2022 [27]. This transition correlates directly with continuous agricultural expansion documented through land use change analysis. Future projections indicate a continuing increase in annual TN inflow from nitrogen fertilizer and soil nitrogen reservoirs, expected to reach 1841.6 tons by 2032 and account for 65.2% of total nitrogen inflow [27].

Model Performance Across Watershed Scales and Conditions

The performance of SWAT+ models varies significantly based on watershed characteristics, data quality, and calibration approaches:

Table 3: Watershed Scale and Model Performance Comparison

| Watershed Characteristics | Example Location | Model Performance (NSE) | Key Challenges | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small rural watershed with limited data | Southern Brazil | 0.69-0.74 (Streamflow) | Greater hydrological variability, baseflow representation | Observed precipitation, limited streamflow records |

| Highland agricultural watershed | Korea | Satisfactory for hydrology and water quality | Steep topography, climate change impacts | High-resolution DEM (5×5 m), long-term weather data |

| Karst terrain with NPS pollution | Lijiang River, China | Errors within ±30% (acceptable range) | Complex groundwater-surface water interactions | Water quality monitoring, pollution statistics |

| Global scale implementation | CoSWAT Framework | 23.02% of stations with positive KGE | Computational demands, lack of reservoir implementation | Global DEM, land use, soil, and climate datasets |

The CoSWAT global modeling implementation represents a particularly significant advancement, demonstrating the feasibility of high-resolution (2 km) global hydrological modeling using SWAT+, though with limitations in river discharge performance due to lack of reservoir implementation [40]. This framework provides a reproducible approach for large-scale applications but requires further refinement for accurate extreme flow simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Tools and Resources for Integrated SWAT+ and PLUS Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSWAT+ | QGIS interface for watershed delineation and HRU definition | SWAT+ model setup in QGIS environment | Free, open-source |

| SWAT+ Editor | User interface for modifying SWAT+ inputs and running the model | Model configuration and execution | Free, open-source |

| SWAT+ Toolbox | Sensitivity analysis, calibration, validation | Model parameter optimization and uncertainty analysis | Free, open-source (Windows) |

| SWAT-LUT | Dynamic updating of LULC data into SWAT database | Integration of PLUS projections with SWAT+ | Available with SWAT+ |

| pySWATPlus | Python library for SWAT+ interaction | Automated calibration and data manipulation | Free, open-source |

| R-SWAT | R integration with SWAT+ | Statistical analysis and model diagnostics | Free, open-source |

| MapSWAT | Automated preparation of SWAT+ input maps via Google Earth Engine | Streamlining model setup for global applications | Free, open-source QGIS plugin |

| Global SWAT Data Portal | Source for weather, landuse and soil map data | Data acquisition for global applications | Free access |

The integrated SWAT+ and PLUS modeling framework represents a significant advancement in the comparative study of point source versus non-point source pollution impacts, providing researchers with a sophisticated tool for future risk projection. Performance evaluations demonstrate that this coupled approach effectively captures the complex interactions between land use change, hydrological processes, and pollution dynamics, with the SWAT+ Toolbox emerging as the superior calibration platform despite limitations in baseflow representation [36].

The comparative analysis reveals a critical transition in pollution dominance, with non-point sources—particularly nitrogen fertilizer application in expanding agricultural areas—increasingly surpassing both point sources and atmospheric deposition as the primary contributors to nitrogen pollution in aquatic systems [27]. This shift underscores the importance of adaptive management strategies that account for temporal variations in pollution dominance, with targeted interventions during critical control periods such as the growing season for agricultural NPS and autumn/winter months for atmospheric deposition.

Future research should prioritize the enhancement of extreme flow simulation capabilities, refinement of global soil datasets, incorporation of CMIP6 climate projections with appropriate bias correction, and more sophisticated representation of groundwater flow dynamics [41] [38]. The ongoing development of community resources like the CoSWAT framework for global applications and the pySWATPlus Python library for automated workflows promises to increase the accessibility and reproducibility of integrated modeling approaches, ultimately advancing our capacity to project and mitigate future pollution risks in a rapidly changing world.

Nontarget Screening and Environmental DNA for Ecosystem Health Assessment

Understanding the origin and impact of pollutants is fundamental to effective ecosystem management. Environmental pollution is broadly categorized as either point source or non-point source pollution. Point source pollution originates from a single, identifiable conveyance, such as a factory discharge pipe or a wastewater treatment plant [10]. In contrast, non-point source pollution comes from diffuse origins, caused by rainfall or snowmelt picking up and carrying natural and human-made pollutants from land into lakes, rivers, and groundwater [1]. This distinction is critical for monitoring; point sources can be measured at the outlet, while non-point sources require landscape-scale assessment.

This guide compares two advanced monitoring technologies—Nontarget Screening (NTS) and Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis—for assessing ecosystem health within this research context. NTS uses high-resolution mass spectrometry to detect a wide array of chemical pollutants [42], making it ideal for identifying both known and unknown contaminants. eDNA analysis uses genetic material shed by organisms into the environment to determine species presence and community composition [43] [44]. Together, they provide complementary chemical and biological data essential for a holistic understanding of pollution impacts, particularly for non-point sources which are the leading remaining cause of water quality problems [1].

The following table provides a high-level comparison of these two technologies, summarizing their core principles, applications, and key strengths in assessing ecosystem health.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Nontarget Screening and Environmental DNA Analysis

| Aspect | Nontarget Screening (NTS) | Environmental DNA (eDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry to detect unknown chemicals [42] | Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect species-specific or multi-species DNA in environmental samples [44] |

| Primary Application | Detection and identification of chemicals of emerging concern (CECs) and unknown pollutants [45] | Detection of species distribution, including invasive, endangered, or cryptic species [43] [46] |

| Key Strength | Broad chemical coverage without prior target list; discovery of new pollutants [42] | High sensitivity for low-biomass species; non-invasive and less labour-intensive than traditional surveys [44] [46] |

| Data Output | Chemical features (mass-to-charge ratio, retention time, intensity) [42] | DNA sequences for species identification and community composition [44] |

| Ecosystem Insight | Pressure: Direct measurement of chemical pollution exposure [45] | State: Measurement of biological community response to pollution [47] |

Performance Comparison in Pollution Impact Research

A direct comparison of NTS and eDNA reveals how their performances differ in sensitivity, applicability to pollution sources, and the type of ecological information they yield. A mesocosm study simulating treated wastewater discharge (a point source) found that both methods significantly detected the disturbance, but with differing sensitivities [47].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Detecting Treated Wastewater Impact

| Performance Metric | Nontarget Screening (NTS) | Environmental DNA (Metabarcoding) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Efficacy | Effective throughout a 10-day experiment [47] | 18S V9 rRNA gene metabarcoding was superior initially and a top-performer throughout; 16S rRNA was sensitive only in the initial hour [47] |

| Temporal Sensitivity | Signal-to-noise ratio remained stable, increasing its relative strength over time [47] | Sensitivity was highest immediately following the introduction of the pollutant [47] |

| Key Application in Pollution Research | Identifying unknown organic pollutants and transformation products [42] [45] | Detecting changes in microeukaryotic and prokaryotic diversity due to pollution [47] |

| Complementary Nature | Covariation of detected patterns between NTS and metabarcoding methods was observed [47] | Covariation of detected patterns between NTS and metabarcoding methods was observed [47] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, detailed protocols for each technology are outlined below.

Protocol for Nontarget Screening in Water Analysis

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collection: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned glass containers. For point source studies, sample directly from the effluent. For non-point source studies, use a grid or transect sampling approach across the landscape [1].

- Preservation: Immediately acidify samples to pH ~6-8 and store at 4°C or freeze to prevent microbial degradation of target analytes.

- Extraction: Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is commonly used to concentrate a broad range of organic contaminants from water samples. Pass the water sample through a cartridge (e.g., Oasis HLB) which is subsequently eluted with an organic solvent like methanol [42].

Instrumental Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separate compounds using Liquid Chromatography (LC) or Gas Chromatography (GC). LC is suitable for non-volatile and polar compounds, while GC is ideal for volatile and semi-volatile compounds.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the chromatographic output with a High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) such as an Orbitrap or time-of-flight (TOF) system. This provides accurate mass measurements, enabling the determination of elemental compositions [42].

Data Processing and Compound Identification:

- Feature Extraction: Use open-source software (e.g., XCMS, MZmine, PatRoon) or vendor software to convert raw data into a list of chemical features, defined by mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), retention time, and intensity [42].

- Prioritization: Apply prioritization strategies to reduce thousands of features to a manageable number for identification. Strategies include:

- Process-driven: Compare samples upstream/downstream of a point source or before/after a rain event causing non-point runoff [45].

- Chemistry-driven: Prioritize features indicative of halogenated compounds or transformation products [45].

- Effect-directed analysis (EDA): Link features to biological activity [45].

- Identification: Query features against chemical databases (e.g., PubChem, NORMAN) using the accurate mass. Confirm identities by comparing experimental MS/MS fragmentation spectra with reference spectra where available [42] [48].

Protocol for Environmental DNA Analysis in Aquatic Ecosystems

Sample Collection and Filtration: