Validating Biotic Indices for Agricultural Impact on Rivers: A Framework for Robust Ecological Assessment

This article synthesizes current research and methodologies for validating biotic indices used to assess agricultural impacts on riverine ecosystems.

Validating Biotic Indices for Agricultural Impact on Rivers: A Framework for Robust Ecological Assessment

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research and methodologies for validating biotic indices used to assess agricultural impacts on riverine ecosystems. It explores the foundational principles of biomonitoring, examines the development and application of specific indices like multimetric indices (MMIs), and addresses key challenges such as distinguishing natural variability from anthropogenic stress. The content provides a critical comparison of index performance across different geographic and stressor contexts, offering researchers and environmental professionals a comprehensive guide for selecting, applying, and validating these essential ecological assessment tools.

The Basis of Biotic Indices: Core Principles and the Challenge of Agricultural Stressors

Biotic indices are essential tools in environmental management, providing a quantitative measure of ecosystem health by analyzing the composition and abundance of biological communities. These indices are central to legislative frameworks like the European Union's Water Framework Directive (WFD), which mandates the assessment of ecological status for water bodies [1]. Traditionally, assessment relied on structural metrics derived from taxonomy, such as species richness and diversity. However, an evolutionary shift toward functional traits—characteristics that describe an organism's role in the ecosystem—is providing deeper insights into ecological responses to stressors [2]. This guide compares the performance of these differing approaches, with a specific focus on their validation for assessing agricultural impacts on riverine systems.

Comparative Analysis of Biotic Index Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of different approaches to developing and applying biotic indices.

Table 1: Comparative overview of different biotic index approaches and their performance characteristics.

| Index Approach | Core Basis | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Biotic Indices (e.g., BMWP, ASPT) | Taxonomic composition and pollution tolerance of species [3]. | Widely adopted and standardized; provides an integrated overview of past conditions [4]. | Performance drops in non-native regions; may misclassify intermittent streams; assumes specific sensitivity traits [3]. | General water quality assessment. |

| Multimetric Indices (MMIs) | Combination of multiple metrics representing different community attributes (e.g., richness, composition, function) [5]. | More robust and effective than single metrics; incorporates a holistic view of the ecosystem [5]. | Susceptible to sampling error and variation; can yield inconsistent scores across jurisdictions [6]. | Assessing combined stressors (e.g., urban and agricultural pollution) [5]. |

| Functional Diversity Metrics | Ecological roles of organisms (functional traits) such as feeding habits, respiration, and locomotion [2]. | Reveals ecological patterns not captured by taxonomy; better links community structure to ecosystem functioning [2]. | May not capture all dimensions of biological integrity; requires detailed trait information [2]. | Detecting subtle or complex ecological changes. |

| Indicator Species Indices (e.g., AMBI, TSI-Med) | Relative proportions of pre-defined ecological groups (e.g., sensitive vs. tolerant species) [1] [7]. | Effectively captures environmental gradients when calibrated; useful for specific stressors like organic enrichment [1] [7]. | Species assignments can be region-specific; may require correction for natural environmental variation [7]. | Assessing organic matter enrichment in coastal waters [7]. |

Quantitative Performance Data from Recent Studies

Empirical studies directly testing these indices reveal critical variations in their effectiveness. The following table compiles key performance data from recent research.

Table 2: Documented performance data of various biotic indices from recent scientific studies.

| Index / Metric Name | Reported Performance | Stressor / Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Richness, EPT/EPT+OCH | Strong response to anthropogenic predictors; unaffected by natural predictors. | Disconnected pools in temporary rivers. | [8] |

| Niger Delta Urban-Agriculture MMI | 83.3% accuracy for least-impacted sites; 22.2% for heavily impacted sites. | River catchments with combined urban and agricultural pollution. | [5] |

| BMWP & ASPT | Effectively demonstrated impact of flow interruptions and regulation. | Regulated river in a semi-arid region (Iran). | [3] |

| LIFE Index & FFGs | Did not accurately represent environmental conditions, especially river drying. | Regulated river in a semi-arid region (Iran). | [3] |

| M-AMBI & BENFES | Correlated strongly with species diversity and captured environmental gradients effectively. | Heavy metal contamination in an estuary. | [1] |

| AMBI, BENTIX, BOPA/BO2A | Showed lower sensitivity to environmental gradients in a polluted estuary. | Heavy metal contamination in an estuary. | [1] |

| Stressor-Specific Indices | Highly inter-correlated; primarily reflected low oxygen, not their designated stressor. | Multiple freshwater stressors (e.g., sediment, nutrients). | [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Index Development and Validation

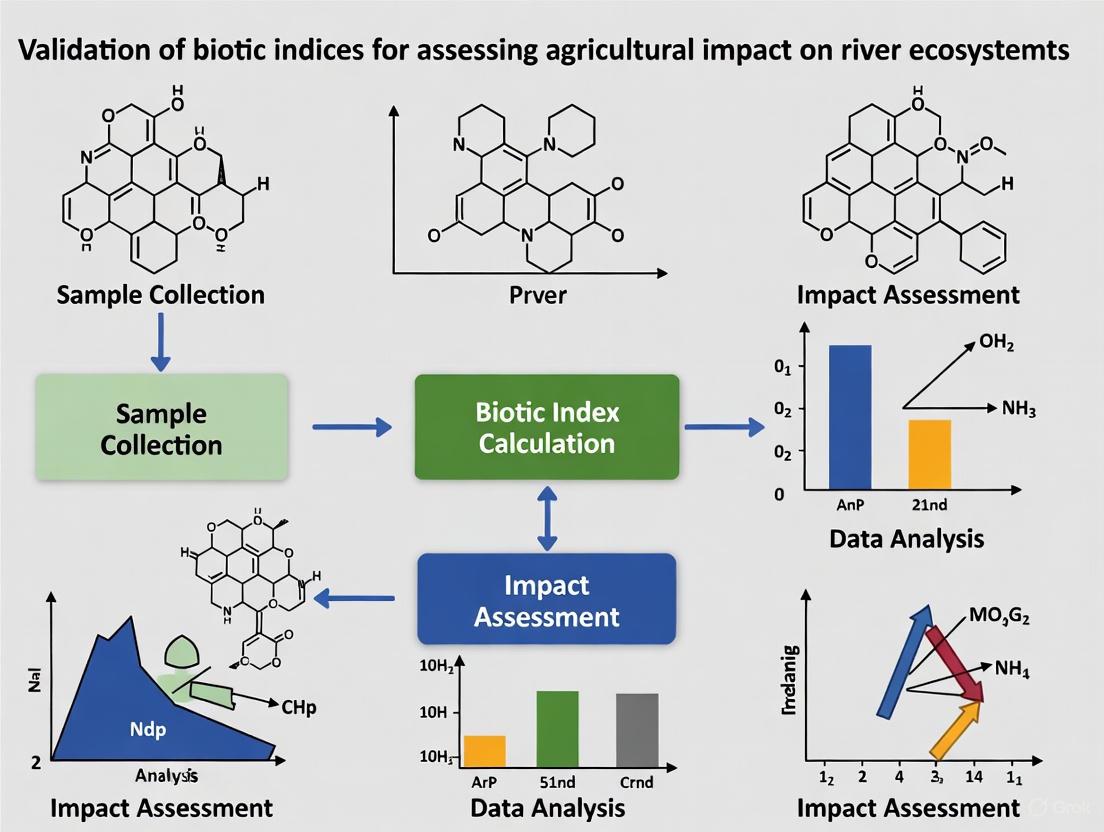

A critical component of using biotic indices is understanding how they are developed and tested. The following workflow outlines the general protocol for creating and validating a multimetric index (MMI), a common and robust approach.

Diagram 1: MMI Development and Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Site Classification and Metric Testing

The foundational step involves classifying sampling stations based on the degree of human impact, typically using physico-chemical variables and catchment land-use data. Stations are categorized as Least-Impacted Stations (LIS), Moderately Impacted Stations (MIS), or Heavily Impacted Stations (HIS) [5]. A large set of candidate metrics (e.g., 67 potential metrics in the Niger Delta study) are statistically tested for their ability to discriminate between these impact categories. Only the most significant and non-redundant metrics are retained for the final index. For instance, in the Niger Delta MMI, the five retained metrics included %Odonata and Oligochaete richness [5].

Scoring System Implementation: Continuous vs. Discrete

A pivotal methodological choice is the scoring system. The continuous scoring system (e.g., scores of 0–10) uses fractional values and is considered less subjective, as it allows for direct rescaling of metrics [5]. In contrast, the discrete scoring system uses predetermined integer scores (e.g., 1, 3, 5) without allowing for fractions, which can make interpretation more complex if disturbance levels vary from initial projections [5]. Recent research suggests the continuous system may be more effective.

Independent Validation

A crucial, yet often overlooked, step is validating the constructed index with a separate dataset not used in its development. This process tests the index's real-world applicability and robustness. Performance is reported as accuracy rates for each impact category, which can vary significantly—as evidenced by the Niger Delta MMI's 83.3% accuracy for LIS but only 22.2% for HIS [5].

Conceptual Framework: From Environmental Stress to Ecological Response

The theoretical foundation of biotic indices is rooted in understanding how communities respond to stress. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway from anthropogenic pressure to the final index calculation, integrating both structural and functional approaches.

Diagram 2: From Stress to Index Calculation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Benthic Macroinvertebrate Studies

Field and laboratory work for developing biotic indices based on benthic macroinvertebrates requires specific equipment and reagents. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for benthic macroinvertebrate biomonitoring.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Surber Sampler / D-net | Quantitative (Surber) and qualitative (D-net) collection of benthic macroinvertebrates from stream substrates [3] [2]. | Standardized surface area (e.g., 25x25 cm frame) and kick-sampling time are critical for comparability [2]. |

| Van Veen Grab | Collecting soft-bottom macrofauna samples in marine and estuarine environments [9]. | Typical surface area is 0.1 m²; ensures standardized sampling of sediment-dwelling organisms. |

| Rose Bengal Stain | Staining living (cytoplasm-containing) foraminifera specimens to distinguish them from dead tests at the time of collection [7]. | Typically used as a 2 g/L solution in 96% ethanol; crucial for accurate ecological interpretation. |

| Ethanol (70-96%) | Preservation and fixation of biological samples immediately after collection to prevent decomposition [2] [7]. | Concentration may vary (70% for macroinvertebrates, 96% in stain for foraminifera). |

| Stereomicroscope | Sorting and initial taxonomic identification of preserved macroinvertebrate samples in the laboratory [2]. | Essential for observing key morphological characteristics for family or genus-level ID. |

| Sodium Polytungstate | A heavy liquid used to concentrate foraminiferal tests from sandy sediments via flotation [7]. | Used at a density of 2.3; improves processing efficiency for specific sediment types. |

The comparative data and protocols presented in this guide highlight that no single biotic index is universally superior. The choice of tool must be context-dependent. For assessing agricultural impacts, which often involve multiple, diffuse stressors, Multimetric Indices (MMIs) show significant promise due to their holistic nature [5]. However, their variable performance across impact levels necessitates caution. Furthermore, the common inter-correlation of stressor-specific indices suggests that a diagnosis based on a single index may be misleading; low oxygen from organic matter decomposition, a common consequence of agricultural runoff, can confound indices for other stressors like fine sediment or nutrients [4]. Therefore, a multi-faceted approach that combines functional and taxonomic metrics [2], and is independently validated for the specific region of interest, provides the most robust framework for accurate agricultural impact assessment.

Agricultural activities disrupt freshwater ecosystems through multiple interconnected pressures, including diffuse pollution, water abstraction, and hydromorphological alteration [10] [11]. These pressures collectively impair riverine biodiversity and ecosystem function, necessitating robust assessment methodologies. The European Water Framework Directive (WFD) and other environmental policies have established frameworks requiring the assessment of water bodies against their reference conditions—the expected biological and physicochemical state under minimal human impact [10] [1]. This comparative guide evaluates the efficacy of various biotic indices used to measure ecological status in agriculturally impacted rivers, providing researchers with validated protocols and performance data for selecting appropriate assessment tools.

The fundamental challenge in agricultural impact assessment lies in distinguishing anthropogenic pressures from natural environmental variability, a difficulty amplified in naturally stressed systems like estuaries—a phenomenon known as the Estuarine Quality Paradox [1]. Furthermore, the application of non-indigenous biotic indices without regional validation can lead to significant misclassifications of ecological status [3]. This guide synthesizes experimental data from recent studies across diverse geographical contexts to establish a evidence-based framework for biotic index selection and application in agricultural impact assessment.

Comparative Performance of Biotic Assessment Indices

Biotic indices utilize the composition of aquatic communities—particularly benthic macroinvertebrates and fish—to evaluate ecosystem health. These organisms provide ideal bioindicators due to their relative sedentarity, longevity, diverse biological traits, and sensitivity to various stressors [1]. Different index types have been developed with varying theoretical foundations:

- Multimetric indices combine multiple metrics representing different aspects of community structure (e.g., diversity, composition, function) into a single value [6].

- Multivariate methods analyze community composition patterns in relation to environmental gradients [6].

- Biotic indices (e.g., BMWP, ASPT, AMBI) assign sensitivity scores to specific taxa based on their tolerance to pollution [1] [3].

- Functional approaches focus on biological traits such as feeding mechanisms rather than taxonomic composition [3].

The selection of an appropriate index depends on the specific agricultural pressure of interest, the spatial and temporal scale of assessment, and the ecological context of the water body being evaluated [12].

Quantitative Comparison of Index Performance

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Benthic Macroinvertebrate Indices

| Index Name | Theoretical Basis | Effective Stressors Detected | Limitations | Geographical Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-AMBI | Multivariate analysis of benthic communities | Multiple stressors, organic pollution, heavy metals [1] | Requires reference conditions; moderate sensitivity to hydromorphological alteration [1] | Validated for European transitional waters [1] |

| BENFES | Benthic community structure and function | General degradation, water quality parameters [1] | Limited application in temporary rivers [1] | Developed for estuarine systems; limited freshwater validation [1] |

| BMWP | Family-level tolerance scores | Organic pollution, water quality deterioration [3] | Developed for temperate climates; inaccurate in semi-arid regions [3] | Widely applied but requires regional adaptation [3] |

| ASPT | Average score per taxon (BMWP derivative) | Organic pollution, flow regulation [3] | Similar limitations to BMWP; insensitive to flow intermittency [3] | Same as BMWP [3] |

| AMBI | Ecological groups based on sensitivity | Chemical pollution, particularly in marine/estuarine systems [1] | Low sensitivity in naturally stressed environments [1] | Primarily marine and estuarine systems [1] |

| LIFE | Flow velocity preferences of macroinvertebrates | Flow regime alterations [3] | Fails in intermittent rivers; assumes continuous flow [3] | Developed for UK rivers; limited transferability [3] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Fish-Based Indices

| Index Name | Theoretical Basis | Effective Stressors Detected | Limitations | Geographical Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBI (Index of Biotic Integrity) | Multimetric (richness, composition, tolerance) | Multiple agricultural pressures [6] | Susceptible to sampling error; inconsistent across regions [6] | Variable performance across management jurisdictions [6] |

| Multivariate IBI variants | Statistical patterns in community composition | Land use intensity, cumulative pressures [6] | Complex interpretation; requires specialized expertise [6] | Limited large-scale comparability [6] |

Recent research demonstrates that the agricultural intensity index, which incorporates data on nutrient application, pesticide use, water abstraction, and riparian land use, nearly doubles the correlative strength with river ecological status compared to simple measurements of agricultural land cover [11]. This highlights the importance of considering not just the presence of agriculture, but its specific practices and intensity when assessing impacts.

Experimental Protocols for Index Validation

Standardized Field Sampling Methodologies

Benthic Macroinvertebrate Sampling

The most widely adopted protocol involves quantitative sampling using a Surber sampler (25 × 25 cm frame) with three replicate samples per station [3]. Each sample should be collected via standardized kick-sampling for 3 minutes, followed by an additional 1-minute hand search of characteristic microhabitats. This approach ensures representative collection while maintaining comparability across studies. Supplementary qualitative sampling using a D-net expands taxonomic representation for presence-absence data [3]. Sampling should be stratified across seasons and flow conditions to account for temporal variability, particularly in regulated or intermittent systems.

Fish Community Sampling

Fish-based indices require systematic sampling approaches that account for habitat heterogeneity and species-specific detectability. While specific methodologies vary by ecosystem type, standardized protocols include electrofishing along predetermined river stretches with multiple passes, gill netting in larger water bodies, and seining in appropriate habitats. The critical consideration is consistency in effort across sampling locations and temporal repeats to ensure comparability [6].

Laboratory Processing and Taxonomic Identification

Benthic samples require preservation in 70-95% ethanol and sorting under magnification (6-10× magnification stereomicroscope) [3]. Identification should be to the finest practicable taxonomic level (typically genus or species for sensitive indices, family level for coarser indices like BMWP). Quality control measures should include cross-verification by multiple taxonomists and reference to validated specimen collections. For molecular approaches, DNA extraction and amplification protocols must be standardized across samples to ensure consistent results.

Data Analysis and Index Calculation

Calculation of biotic indices follows standardized equations specific to each index. For multimetric fish indices, this typically involves normalization of individual metrics (e.g., species richness, percentage of tolerant individuals, trophic composition) and integration into a final score [6]. Benthic indices like BMWP involve summing tolerance scores across all identified families, while ASPT represents the average score per taxon [3]. Multivariate indices like M-AMBI require reference databases and statistical software for proper implementation [1]. All analyses should incorporate uncertainty estimation through bootstrapping or similar resampling methods, as index scores can vary by up to 50 points due to natural community variation and sampling error [6].

Experimental workflow for validating biotic indices

Research Reagent Solutions for Aquatic Biomonitoring

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Equipment for Biotic Assessment

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling Equipment | Surber sampler, D-nets, Kick nets, Van Dorn bottle | Quantitative and qualitative collection of benthic organisms | Surber sampler provides standardized area coverage; D-nets for qualitative habitat-specific sampling [3] |

| Sample Preservation | 70-95% ethanol, formaldehyde, coolers | Preservation of specimen integrity for taxonomic identification | Ethanol preferred for DNA analysis; formaldehyde for specific morphological studies [3] |

| Laboratory Identification Tools | Stereomicroscope (6-50× magnification), taxonomic keys, reference collections | Taxonomic identification to required level | Digital imaging systems enhance verification and data sharing [3] |

| Water Quality Instrumentation | Multiparameter sondes, spectrophotometers, nutrient analyzers | Measurement of physicochemical parameters | Essential for correlating biotic responses with environmental drivers [1] [3] |

| Statistical Software | R packages (vegan, PRIMER, IBM SPSS) | Data analysis and index calculation | Multivariate analyses require specialized software capabilities [1] [6] |

Integration of Novel Monitoring Technologies

Satellite-Based River Monitoring

Remote sensing technologies provide complementary approaches to traditional biomonitoring by offering synoptic, frequent coverage of large river systems. Satellite data can monitor key water quality parameters including turbidity, chlorophyll-a, colored dissolved organic matter, and surface temperature [13]. These technologies are particularly valuable for:

- Large-scale assessment: Monitoring river reaches inaccessible to ground crews

- Trend analysis: Detecting long-term changes through time-series data

- Event response: Rapid assessment of pollution events or extreme flow events

- Watershed context: Linking terrestrial land use with in-stream conditions [13]

Successful applications include the Zambezi Basin, where satellite data on water quality and discharge supports regional management despite scarce ground stations, and the Rio Doce in Brazil, where turbidity maps traced a 650 km mudflow after a dam collapse [13]. The integration of satellite data with biological indices creates a powerful multi-scale assessment framework.

Molecular Techniques

Environmental DNA (eDNA) methodologies are emerging as complementary tools to traditional morphological identification. While not yet widely incorporated into standard biotic indices, molecular approaches offer potential for rapid biodiversity assessment and detection of cryptic species. The current limitation lies in establishing quantitative relationships between eDNA signals and traditional metrics used in biotic indices.

Pathways of agricultural impact on river biota

The validation of biotic indices for agricultural impact assessment requires careful matching of index selection to specific research questions and environmental contexts. Based on comparative performance data:

- For comprehensive assessment in European temperate rivers, M-AMBI provides the most robust evaluation of multiple agricultural pressures [1].

- For organic pollution monitoring in regions with established tolerance scores, BMWP and ASPT offer reliable, cost-effective approaches despite limitations in intermittent systems [3].

- For flow alteration studies, LIFE index can be informative but requires validation in non-perennial systems [3].

- For large-scale comparative studies, fish-based IBIs show promise but require standardization across jurisdictions to enable meaningful comparison [6].

A tiered monitoring approach is recommended, beginning with simpler screening methods followed by sophisticated multi-index assessments for prioritized areas [12]. Critically, the application of non-indigenous indices without regional validation should be avoided, as evidenced by the failure of standard metrics in semi-arid regulated rivers like the Zayandehrud in Iran [3]. Future methodological development should focus on creating regionally adapted indices that account for specific agricultural practices and natural environmental gradients, particularly in the context of increasing climate variability and water scarcity.

Agricultural activities are a significant source of non-point source pollution, affecting river ecosystems through runoff containing fertilizers, pesticides, and sediment. Biotic indices have emerged as powerful tools for assessing these impacts by transforming complex biological data into simple, managerially relevant scores of ecological condition [14]. These indices are environmental scoring tools that translate raw biological data collected from a water body into a numerical score representing overall ecological condition [14]. Unlike instantaneous chemical measurements, biotic indices provide integrated, long-term assessments of ecosystem health by tracking the response of biological communities to anthropogenic stressors [1]. For researchers and environmental managers, these tools offer a systematic approach for evaluating compliance with discharge permits, setting conservation priorities, and assessing the effectiveness of mitigation and restoration projects in watersheds affected by agricultural activities [14].

The fundamental premise underlying biotic indices is that the structure and composition of aquatic communities reflect the cumulative effects of environmental stressors. Sensitive species decline under pollution pressure while tolerant species thrive, creating measurable shifts in community composition that can be quantified through standardized metrics. This article provides a comparative analysis of major biotic indices used in agricultural impact assessment, detailing their experimental protocols, applications, and performance characteristics to guide researchers in selecting appropriate tools for riverine ecosystem monitoring.

Core Principles and Theoretical Framework

Ecological Foundations of Biotic Indices

Biotic indices function on several well-established ecological principles. First, they rely on the concept of ecological gradients, where species distributions correspond to environmental conditions along a stress gradient [1]. In agricultural contexts, this typically involves gradients of nutrient enrichment, sedimentation, or pesticide contamination. Second, they employ the principle of indicator taxa, where certain organisms with known tolerance levels serve as proxies for overall ecosystem health [15]. The "Estuarine Quality Paradox" noted in marine environments [1] has parallels in agricultural streams, where distinguishing natural variability from anthropogenic impacts remains challenging.

The theoretical framework incorporates the understanding that biological communities integrate stressors over time and space, providing a more comprehensive picture of ecosystem health than periodic chemical measurements. Different taxonomic groups offer complementary insights: benthic organisms reflect sediment conditions, fish communities indicate habitat connectivity and water quality, and algal assemblages respond rapidly to nutrient changes. Effective agricultural impact assessment therefore often requires multiple indices targeting different biological components.

Index Development and Validation Methodology

Developing a robust biotic index follows a standardized protocol. Researchers first classify species according to their sensitivity or tolerance to environmental degradation based on distribution and abundance variations along a known water quality gradient [16]. This classification forms the foundation for metrics that distinguish impaired from reference sites [16]. Validation involves testing the index across independent datasets [15] and different stressor gradients to ensure reliable performance. Region-specific adaptations are often necessary, as species sensitivities can vary geographically [15]. The validation process must confirm that index scores respond predictably to anthropogenic stressors while remaining insensitive to natural environmental variation [8].

Comparative Analysis of Major Biotic Indices

The table below summarizes key biotic indices used in environmental monitoring, their applications, and performance characteristics based on current research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biotic Indices for Ecosystem Assessment

| Index Name | Biological Group | Primary Application Context | Performance in Agricultural Assessment | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBI (AZTI Marine Biotic Index) | Marine benthic invertebrates | Coastal/transitional waters [1] | Variable performance; requires regional adaptation [15] | Well-established with extensive species list | Developed for European waters; limited accuracy without local calibration [15] |

| Foram-AMBI | Benthic foraminifera | Transitional waters [15] | Accurately reflects degraded conditions in polluted areas [15] | High potential as environmental health indicator; significant correlation with TOC [15] | Requires development of regional species lists [15] |

| BENTIX | Benthic invertebrates | Marine ecosystems [1] | Lower sensitivity in comparative studies [1] | Simplified classification system | Reduced effectiveness in naturally stressed systems |

| Family Richness, EPT/EPT+OCH | Macroinvertebrates | Disconnected pools in temporary rivers [8] | Strong response to anthropogenic predictors; unaffected by natural variation [8] | Effective in temporary river systems; resistant to natural environmental interference | Limited application in perennial systems |

| Fish-based Biotic Index | Fish assemblages | River systems [16] | Effectively distinguishes impaired from reference sites [16] | Reflects watershed conditions; sensitive to water quality changes [16] | Requires local calibration; limited to fish-bearing waters |

Performance Considerations for Agricultural Applications

When applying biotic indices to agricultural impact assessment, several critical factors emerge from recent research. Indices vary significantly in their sensitivity to different stressors, with some showing strong responses to anthropogenic predictors while remaining unaffected by natural environmental variation [8]. This distinction is particularly valuable in agricultural watersheds where natural and human-induced stressors often interact. The spatial gradient of impact is another crucial consideration, with inner estuary areas typically showing poorer condition compared to outer marine zones [1] – a pattern that mirrors the downstream impact gradient commonly observed in agricultural watersheds.

Temporal sensitivity represents another key performance characteristic, as effective monitoring must detect improvements following management interventions [1]. Research in the Odiel Estuary demonstrated detectable improvements in benthic community structure and water quality over an 18-year monitoring period, particularly following implementation of corrective measures [1]. This underscores the importance of selecting indices with sufficient sensitivity to track recovery trajectories in restoration programs.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Field Sampling Procedures

The reliability of biotic indices depends fundamentally on standardized sampling protocols. For macroinvertebrate-based indices, sampling typically involves collecting benthic organisms from specific habitats using standardized methods such as kick nets, Surber samplers, or grab samplers, depending on the water body type. The experimental workflow for developing and applying biotic indices follows a systematic process that can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Biotic Index Development Workflow (47 characters)

In temporary river systems, special consideration must be given to sampling disconnected pools, which serve as biodiversity refugia when flow ceases [8]. These habitats require adapted sampling approaches that account for their unique hydrology and community assembly processes. For fish-based indices, methodologies typically involve stratified sampling across representative habitats using electrofishing, seining, or trapping, with effort standardized by distance or time [16].

Laboratory Processing and Analysis

Laboratory processing varies by taxonomic group but generally involves specimen identification to standardized taxonomic levels (usually species or genus), enumeration, and sometimes biomass determination. For macroinvertebrates, the EPT (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera) index is frequently utilized, with these insect orders serving as indicators of good water quality due to their sensitivity to pollution [8]. Quality control procedures include specimen vouchering, expert verification of difficult taxa, and inter-laboratory calibration to ensure consistent identification.

For foraminiferal analyses, processing includes rose-bengal staining to distinguish living specimens from empty tests, followed by identification and enumeration under microscopy [15]. The Foram-AMBI methodology involves assigning species to five ecological groups based on their weighted-averaging optimum and tolerance to total organic carbon contents [15].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Biotic Index Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Equipment | Kick nets, Surber samplers, benthic grabs, electrofishing gear, rose-bengal stain | Field collection of biological samples | Standardized sampling across study sites [8] [15] [16] |

| Laboratory Supplies | Microscopes, sorting trays, preservatives (ethanol, formaldehyde), staining materials | Sample processing and taxonomic identification | Specimen analysis and ecological classification [15] [16] |

| Reference Collections | Taxonomic keys, regional species lists, digitized specimen databases | Accurate species identification | Critical for assigning organisms to correct ecological groups [15] |

| Water Chemistry Kits | TOC analyzers, nutrient assay kits, multiparameter probes | Physicochemical parameter quantification | Correlation of biological responses with environmental gradients [8] [15] |

| Statistical Software | R packages, PRIMER, specialized index calculation tools | Data analysis and index computation | Metric calculation and validation [17] [8] |

Implementation Framework and Data Interpretation

Application Workflow for Agricultural Assessment

Implementing biotic indices for agricultural impact assessment follows a logical sequence from study design to management response. The relationship between agricultural stressors and biological responses can be visualized as a conceptual model:

Diagram 2: Agricultural Impact Assessment Pathway (46 characters)

The implementation begins with reference condition establishment, followed by strategic site selection along suspected impact gradients. After standardized field sampling and laboratory processing, data undergoes quality assurance before index calculation. Interpretation requires comparing scores to reference conditions and established thresholds for ecological status classification. Effective communication of results to stakeholders completes the cycle, potentially triggering management responses where impairments are detected.

Interpretation Guidelines and Ecological Status Classification

Interpreting biotic index scores requires understanding their ecological significance within specific regional contexts. Most indices classify water bodies into ecological status categories ranging from "high" to "bad" based on deviation from reference conditions. For example, the Foram-AMBI index developed for Brazilian transitional waters successfully identified moderate to poor ecological quality status in the most polluted areas of Sepetiba Bay and Guanabara Bay [15]. This classification was further validated by significant correlations between Foram-AMBI and total organic carbon content in both ecosystems [15].

Temporal trends often provide more meaningful information than single measurements, revealing whether conditions are improving or deteriorating in response to management actions or changing agricultural practices. The Odiel Estuary study demonstrated this principle by tracking index values over 18 years, showing detectable improvements in benthic community structure and water quality, particularly in 2016, following long-term mitigation efforts [1].

Future Directions and Research Priorities

The field of biotic index development continues to evolve with several promising research frontiers. Multi-index approaches are increasingly recommended, as different indices provide complementary information and collectively enhance assessment reliability [1]. This is particularly relevant for agricultural impact assessment where multiple stressors often interact. Functional metrics represent another emerging frontier, with recent research evaluating traits such as functional redundancy and response diversity alongside traditional structural indices [8].

Regional adaptations remain a critical priority, as demonstrated by the improved accuracy of the Brazilian Foram-AMBI list compared to European lists [15]. Similar regional calibration efforts are needed globally, particularly in tropical agricultural regions where index development has been limited. Finally, technological innovations in DNA metabarcoding, remote sensing, and automated image recognition promise to revolutionize data collection, potentially expanding the spatial and temporal scale of biotic index applications while reducing costs. These advances will further solidify the role of biotic indices as essential tools for sustainable agricultural management and river conservation.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three primary biological indicator groups—diatoms, macroinvertebrates, and fish—used for assessing the ecological health of riverine ecosystems, with a specific focus on agricultural impact assessment. The selection of appropriate bio-indicators is a critical step for researchers and environmental managers aiming to diagnose the complex pressures stemming from agricultural activities, such as nutrient enrichment, sedimentation, and habitat alteration. The following data, derived from global studies, demonstrate that each group offers distinct advantages and sensitivities, making them suited for different aspects of ecological validation.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Bio-indicator Groups for Agricultural Impact Assessment

| Indicator Group | Primary Sensitivities | Response Time | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diatoms | Nutrients (N, P) [18], pH, conductivity [19], ionic composition [18] | Rapid (days-weeks) | High precision for nutrient loading [18]; Cost-effective; Integrates water quality over time [20] | Less sensitive to physical habitat degradation [18] |

| Macroinvertebrates | Organic pollution [18], sedimentation [21], habitat structure [22] | Intermediate (months) | Well-established protocols (e.g., SASS5, BMWP) [18]; Good indicators of overall ecosystem health [23] | Response can be confounded by dispersal processes [23] |

| Fish | Habitat fragmentation [18], flow regime [18], overall ecosystem integrity [22] | Slow (years) | Reflect long-term and broad-scale effects [22]; High public and economic value | Low sensitivity to water quality variables; Omnivores/air-breathers can mask pollution [18] |

Detailed Response Profiles to Agricultural Stressors

Agricultural activities impose a suite of stressors on river ecosystems. The responsiveness of each bio-indicator group to these specific stressors is detailed below.

Table 2: Documented Responses to Common Agricultural Stressors

| Agricultural Stressor | Diatom Response | Macroinvertebrate Response | Fish Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Enrichment (Eutrophication) | Strong response. Community composition shifts towards motile, nutrient-tolerant species [20]; Trophic Diatom Index (TDI) increases [18]. | Moderate response. Diversity metrics (e.g., Shannon Weiner) and tolerance indices (e.g., ASPT) decrease with high nutrients [22]. | Weak or indirect response. Assemblages may show little change; omnivorous species may proliferate [18]. |

| Increased Sedimentation/Siltation | Moderate response. Can smother epilithic (rock-attached) communities [22]. | Strong response. Diversity decreases; community shifts to sediment-tolerant taxa (e.g., some Annelida) [22]. | Strong response. Direct impact on spawning grounds for lithophilic species; assemblage integrity declines [18]. |

| Habitat Degradation (Riparian loss) | Weak response. Primarily driven by water chemistry [18]. | Strong response. Loss of sensitive taxa (e.g., EPT) reliant on specific substrates and flow conditions [22]. | Strong response. Fish Assemblage Integrity Index (FAII) declines; loss of habitat specialists [18] [22]. |

| Organic Pollution | Community composition shifts; sensitive species replaced by pollution-tolerant ones [24]. | Strong response. Core metric for indices like BMWP and Biotic Index (BI) [23] [24]. | Variable response. Depletes oxygen, affecting sensitive species; tolerant air-breathers persist [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bio-indication Studies

Standardized protocols are essential for generating reliable, comparable data in biomonitoring programs. The following methodologies are widely cited in the literature.

Diatom Sampling and Analysis (Epilithic Communities)

- Sampling Technique: At each sampling station, a standard area (e.g., 11.34 cm²) of surface from three randomly selected pebbles is scraped clean using a toothbrush and rinsed into a sample bottle [22] [24].

- Laboratory Processing: Samples are digested with strong oxidizing agents (e.g., hydrogen peroxide) to clean organic matter from the silica frustules (cell walls). Permanent microscope slides are prepared using a high-resolution mounting medium (e.g., Naphrax) [18].

- Identification and Metric Calculation: A minimum of 400 valves are identified to the species level using high-powered microscopy (1000x magnification). The species counts are used to calculate biotic indices such as the Trophic Diatom Index (TDI), which reflects nutrient status [18].

Macroinvertebrate Sampling and Analysis

- Sampling Technique: Macroinvertebrates are typically collected using a Surber sampler (30 x 30 cm frame with a 500 µm mesh net) [22] [23]. For a comprehensive site assessment, multiple samples are taken from different microhabitats (e.g., riffles, pools, submerged vegetation) and pooled.

- Laboratory Processing: Organisms are preserved in 70-95% ethanol and identified in the laboratory to the lowest practical taxonomic level (usually family or genus) using dichotomous keys [22] [23].

- Metric Calculation: Multiple indices can be calculated, including:

- Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H'): Measures overall taxonomic diversity.

- Biological Monitoring Working Party (BMWP) Score: Assigns tolerance scores to families; the Average Score Per Taxon (ASPT) is the BMWP score divided by the number of scoring taxa, which is less sensitive to sampling effort [23].

- EPT Richness: The number of taxa from the orders Ephemeroptera (mayflies), Plecoptera (stoneflies), and Trichoptera (caddisflies), which are generally pollution-sensitive [23].

Fish Sampling and Assessment

- Sampling Technique: In wadable streams, fish are collected via electrofishing (pulsed DC) across a defined reach (e.g., 200-300 m) encompassing all major habitat types (pools, riffles, runs) [22] [24]. In deeper rivers, boat-based seining may be employed.

- Field Processing: Fish are identified, counted, measured (length), and weighed. All individuals are returned alive to the river after processing [24].

- Metric Calculation: The Fish Assemblage Integrity Index (FAII) is one index that evaluates community structure, the presence of exotic species, and the health of individual fish to provide a holistic assessment of anthropogenic impact [18].

Conceptual Workflow for Bio-indicator Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of selecting and validating bio-indicator groups for a specific agricultural context, such as assessing the impact of different farming practices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biomonitoring relies on specialized equipment and materials for field collection, sample preservation, and laboratory analysis.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Bio-indicator Studies

| Item | Primary Function | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Surber Sampler | Quantitative sampling of benthic macroinvertebrates from a defined substrate area [22] [23]. | Field collection of macroinvertebrates in wadable streams. |

| Electrofishing Unit | Generating an electric field in water to temporarily stun fish for capture and enumeration [22] [24]. | Field collection of fish assemblages in wadable streams. |

| Diatom Sampling Kit (Toothbrush, Ruler, Bottles) | Standardized scraping of a known surface area from hard substrates for epilithic diatom collection [22]. | Field collection of diatom communities. |

| Preservative Solutions (95% Ethanol, 70% Ethanol) | Fixing and preserving biological samples to prevent decomposition and degradation. | 95% ethanol for macroinvertebrates [22]; 70% ethanol for long-term storage [23]. |

| Compound Microscope with 1000x Magnification | High-resolution identification of diatom species based on frustule morphology [18]. | Laboratory analysis of diatom samples. |

| Stereo Microscope (Anatomical Lens) | Identification and sorting of macroinvertebrates based on morphological characteristics [22] [23]. | Laboratory analysis of macroinvertebrate samples. |

| Oxidizing Agents (e.g., H₂O₂) | Cleaning organic material from diatom frustules to enable clear microscopic observation [18]. | Laboratory processing of diatom samples. |

| High-Resolution Mounting Medium (e.g., Naphrax) | Creating permanent microscope slides with a high refractive index for diatom identification [18]. | Slide preparation for diatom analysis. |

No single bio-indicator group provides a complete diagnostic picture. The most robust assessments for agricultural impacts are achieved through an integrated multi-assemblage approach [24]. Diatoms offer an unparalleled, precise measure of water quality, particularly nutrient loading. Macroinvertebrates are excellent for detecting organic pollution and intermediate-scale habitat degradation. Fish communities provide a holistic, long-term reflection of ecosystem integrity and are highly sensitive to physical and hydrological alterations.

Therefore, the choice of indicator(s) should be guided by the specific agricultural stressors of concern. For routine monitoring focused on water quality, diatoms are exceptionally powerful [18]. For a comprehensive assessment of overall ecosystem health, integrating all three groups is recommended to validate biotic indices and accurately diagnose the multifaceted impacts of agriculture on river ecosystems.

Developing and Applying Effective Biotic Indices in Agricultural Landscapes

Multimetric Indices (MMIs) have emerged as a cornerstone of modern bioassessment, providing a robust, integrated tool for evaluating the ecological health of freshwater ecosystems. These indices synthesize various biological metrics into a single, comprehensive value that reflects the condition of an ecosystem, effectively integrating both structural and functional attributes of biological communities [25]. Their development represents a significant advancement over traditional single-metric approaches, which often fail to capture the complex, multifaceted responses of ecosystems to anthropogenic stressors such as agricultural pollution [26].

The fundamental strength of MMIs lies in their ability to detect cumulative and synergistic impacts of multiple pressures, including water pollution, hydrological alteration, and physical habitat degradation [26]. By combining metrics from different categories—such as taxonomic richness, composition, tolerance to disturbance, and functional traits—MMIs provide a more holistic view of ecological integrity than any single metric could achieve alone [25] [27]. This comprehensive approach is particularly valuable in agricultural landscapes, where diffuse pollution and habitat modification create complex stressor gradients that demand sophisticated assessment tools.

Biological assemblages, especially benthic macroinvertebrates, are widely used in MMI development due to their sensitivity to environmental changes, limited mobility, and representation across various trophic levels [26] [28]. Their responses to anthropogenic pressures are well-documented and provide reliable signals of ecosystem health degradation or recovery. As freshwater ecosystems worldwide face increasing threats from agricultural intensification, MMIs offer managers and researchers a scientifically rigorous method for tracking changes and evaluating conservation interventions.

Methodological Framework: Protocols for MMI Development and Validation

The development of a robust MMI follows a structured, iterative process that ensures the resulting index is both sensitive to human disturbance and ecologically meaningful. This process typically involves site classification, metric screening, index construction, and validation, with careful attention to reducing subjectivity throughout.

Site Selection and Classification

The initial phase establishes a disturbance gradient by classifying sites into categories based on human influence. Researchers typically employ the reference condition approach, identifying least-disturbed sites that represent the best available ecological state within a region [25] [27]. For example, in a study of Nigerian river systems, sites were classified into three distinct categories: least-impacted stations (LIS), moderately impacted stations (MIS), and heavily impacted stations (HIS) based on the intensity of urban and agricultural activities in their catchments [5]. This classification enables the testing of metric sensitivity across a known gradient of anthropogenic pressure.

Independent criteria for site classification often include measurements of physical habitat quality, water chemistry parameters (e.g., total phosphorus, total nitrogen), and assessment of catchment land use [29] [27]. In large-scale assessments like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's National Lake Assessment, reference sites are identified using regionally explicit definitions that account for natural variability across ecoregions, ensuring that appropriate benchmarks are established for different ecological contexts [27].

Metric Screening and Selection

The core of MMI development involves testing candidate metrics for their ability to discriminate between reference and impaired conditions. This process typically evaluates metrics for three key properties:

- Responsiveness: The metric must show statistically significant differences along the disturbance gradient [30] [31].

- Redundancy: Metrics conveying similar information are identified and removed to avoid overweighting any single dimension of the biological community [25] [32].

- Reproducibility: The metric should demonstrate low natural variability in stable conditions [27] [32].

Advanced approaches now differentiate between correlation in metric values (which may be expected among disturbance-sensitive metrics) and correlation in their errors, with only the latter representing true redundancy that should be eliminated [25]. This refinement allows for the inclusion of multiple metrics that respond similarly to disturbance but provide complementary information.

Index Calculation and Validation

Once metrics are selected, they are normalized and combined into a single index value. Two primary scoring systems exist: continuous scoring (using numerical values, e.g., 0-10) and discrete scoring (using predetermined categories, e.g., 1, 3, 5) [5]. Evidence suggests continuous scoring may be preferable due to reduced subjectivity and greater flexibility [5].

Crucially, the final MMI must be validated using an independent dataset not used during development. For instance, the Niger Delta urban-agriculture MMI achieved performance rates of 83.3% for least-impacted stations and 75% for moderately impacted stations during validation, demonstrating its utility as a biomonitoring tool [5]. This step ensures that the index performs reliably when applied to new sites.

Table 1: Comparison of MMI Development Approaches

| Development Aspect | Traditional Metric-Based Approach | Novel Index-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Method | Selects individual metrics with strongest correlation to disturbance | Randomly generates thousands of metric combinations, selects best-performing MMI |

| Handling of Weak Metrics | Excludes metrics weakly related to disturbance individually | Retains metrics that may contribute unique information when combined |

| Subjectivity | Higher (relies on arbitrary correlation thresholds) | Lower (minimizes subjective decision-making) |

| Performance | Good (validated R² = 0.2518 in prairie pothole wetlands) | Superior (validated R² = 0.2706 in same system) |

Comparative Analysis: MMI Performance Across Ecosystems and Regions

MMIs have been successfully developed and applied across diverse freshwater ecosystems and geographical regions, demonstrating their adaptability to different ecological contexts and stressor types.

Lotic Ecosystems: Rivers and Streams

In riverine systems, MMIs effectively track the impacts of agricultural land use on ecological condition. A nine-year study of the Geum River in South Korea demonstrated that MMIs based on fish assemblages showed clear degradation in downriver regions, with conditions categorized as "fair-poor" [29]. The analysis revealed that nutrient enrichment (particularly phosphorus), organic pollution, and habitat alteration were the primary drivers of ecological decline, with tolerant fish species showing positive functional relationships with increasing disturbance levels [29].

Similarly, research in Mexican mountain rivers developed a benthic macroinvertebrate-based MMI that responded negatively to decreased dissolved oxygen and increased land-use change in catchment areas [30]. The study highlighted that taxonomic and functional diversity loss occurred progressively along disturbance gradients, providing insights for targeted conservation strategies.

Lentic Ecosystems: Lakes and Wetlands

While initially developed for flowing waters, MMIs have proven equally valuable in standing water ecosystems. In the Prairie Pothole Region, where up to 70% of historic wetlands have been lost primarily to agricultural development, vegetation-based MMIs have been crucial for assessing remaining wetlands and evaluating restoration efforts [25].

A macroinvertebrate-based MMI developed for Ethiopian wetlands in predominantly agricultural landscapes successfully distinguished between reference and impaired sites, with nearly 70% of impaired sites exhibiting "bad to poor" ecological conditions [26]. The index showed strong negative relationships with physicochemical variables and human disturbance factors, confirming its utility for wetland assessment in agricultural regions [26].

Advancements in MMI Methodology

Recent research has focused on refining MMI development to enhance sensitivity and ecological relevance. Two significant advancements show particular promise:

Incorporating Functional Traits: Including metrics based on biological traits (e.g., feeding groups, habit traits, physiological tolerances) significantly improves MMI performance and facilitates ecological interpretation [31]. Trait-based metrics provide mechanistic understanding of how disturbances affect ecosystem functioning beyond structural changes alone.

Index Performance-Driven Approach: Rather than selecting metrics based solely on individual performance, generating numerous random metric combinations and selecting the best-performing MMI produces superior results in terms of precision, sensitivity, and responsiveness [25] [31]. This approach acknowledges that metrics with weak individual relationships to disturbance may nonetheless contribute valuable unique information when combined with complementary metrics.

Table 2: Core Metrics in Recently Developed MMIs

| Ecosystem Type | Region | Key Metrics in Final MMI | Primary Stressors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wetlands | Prairie Pothole Region, Canada | Presence/Absence of S. galericulata & H. jubatum; Cover of annuals/biennials; Proportion of annual richness [25] | Agricultural development, hydrologic alteration |

| Rivers | Niger Delta, Nigeria | Chironomidae/Diptera abundance; %Odonata; Margalef index; Oligochaete richness; Logarithmic abundance of sprawler [5] | Urban and agricultural pollution |

| Mountain Rivers | Mexico | Total Abundance; Diptera Richness; Crawler Richness; % Scrapers; % Temporarily Attached Organisms [30] | Land-use change, decreased dissolved oxygen |

| Lakes | United States (National Assessment) | Metrics from six groups: composition, diversity, feeding group, habit, richness, pollution tolerance [27] | Multiple stressors at national scale |

Visualization: Workflow for MMI Development

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in developing and validating a robust Multimetric Index:

MMI Development and Validation Workflow: This diagram outlines the key phases in creating a robust Multimetric Index, from initial planning through implementation, highlighting important considerations at each stage.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for MMI Development

Successful development and application of MMIs requires specific methodological components and analytical tools. The following table outlines key elements in the researcher's toolkit for creating effective multimetric indices.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MMI Development

| Toolkit Component | Function in MMI Development | Examples/Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Site Criteria | Establish ecological benchmarks for least-disturbed conditions | Physical, chemical, and disturbance variables; Land use thresholds [27] |

| Biological Sampling Protocols | Standardized collection of indicator organisms | Rapid bioassessment protocols; D-frame nets; Multi-habitat sampling [5] [28] |

| Metric Screening Framework | Identify metrics with optimal performance characteristics | Tests for responsiveness, redundancy, reproducibility; Random forest modeling [27] [31] |

| Natural Gradient Modeling | Account for natural environmental variation | Residual adjustment; Random forest modeling [27] [31] |

| Validation Dataset | Test MMI performance independently | Split-sample approach; Temporal validation; Spatial validation [5] |

Multimetric Indices represent a powerful approach for assessing the ecological impacts of agricultural activities on freshwater ecosystems. By integrating structural and functional metrics, MMIs provide a holistic view of ecosystem health that transcends what single metrics can achieve. The methodological refinements in MMI development—particularly the incorporation of functional traits, accounting for natural gradients, and adopting index performance-driven approaches—have substantially enhanced their sensitivity and reliability.

As freshwater ecosystems face increasing pressure from agricultural intensification and other human activities, MMIs offer researchers and resource managers a scientifically robust tool for detecting degradation, prioritizing conservation actions, and evaluating restoration outcomes. Their adaptability across diverse ecosystem types and regional contexts makes them particularly valuable for addressing the complex challenges of agricultural impact assessment in a changing world.

Multimetric indices (MMIs) have become a cornerstone for assessing ecological condition, providing a holistic tool that integrates multiple biological metrics into a single, powerful indicator of environmental health. This guide objectively compares the core methodologies for developing these indices, with a specific focus on assessing agricultural impacts on riverine systems. The following sections break down the procedural frameworks, provide direct performance comparisons, and detail the experimental protocols that underpin robust MMI creation.

Core Methodologies for MMI Development

The development of a Multimetric Index (MMI) is a structured process designed to transform raw biological data into a reliable indicator of ecological condition. Two primary methodological approaches have emerged: the traditional metric-based approach and the more contemporary index-based approach. The table below summarizes the foundational concepts and rationales behind these two core methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Core MMI Development Approaches

| Aspect | Metric-Based Approach | Index-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Rationale | Combines the individual metrics that show the strongest independent response to a disturbance gradient. [25] | Assembles metrics into an index where their collective information provides the strongest possible response to disturbance, even if individual metrics are weakly related. [25] |

| Selection Philosophy | "Select the best metrics, then build one index." | "Build many indices from random metric combinations, then select the best-performing index." [25] |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive and straightforward; metrics have clear, individual ecological relevance. | Minimizes subjective decision-making; can capture unique, non-redundant information from a wider pool of metrics, potentially leading to a superior final index. [25] |

| Typical Workflow | Linear and sequential. [32] | Iterative and computational, involving the generation and validation of thousands of candidate MMIs. [25] |

Comparative Performance & Experimental Data

The theoretical differences between the two approaches translate into tangible variations in performance. A direct comparison in the development of a vegetation-based MMI for prairie pothole wetlands quantified these differences, providing clear experimental data on their effectiveness. [25]

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Metric-Based vs. Index-Based MMIs

| Performance Criterion | Metric-Based MMI | Index-Based MMI |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Result (R²) | 0.2518 (F₁,₂₂ = 7.404, p = 0.012) [25] | 0.2706 (F₁,₂₂ = 8.163, p = 0.009) [25] |

| Model Fit (AICc) | Higher (Poorer fit) [25] | 754.93 (Superior fit, AICc weight = 0.97) [25] |

| Conclusion | Successfully validated but was outperformed by the index-based alternative. [25] | Generated a superior biomonitoring tool; recommended as the standard method for MMI creation. [25] |

Beyond the core methodology, the scoring system used for metrics significantly influences an MMI's precision. The continuous scoring system (e.g., scoring from 0–10) offers greater statistical flexibility, is less subjective, and produces more easily interpretable ecological condition classes. In contrast, the discrete scoring system (e.g., scoring 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) uses arbitrary ranges and does not allow for rescaling, making it less robust for river management. [5]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Metric Screening and Selection Protocol

The initial phase of MMI development involves refining a broad list of candidate metrics into a core set for the index. The following workflow outlines the critical steps for screening and selecting robust metrics.

The screening process, as illustrated, involves several statistical filters applied to candidate metrics [32]:

- Range and Repeatability: Metrics must exhibit sufficient variation across sites and produce consistent results upon resampling. [33]

- Responsiveness: This is a critical test where metrics must demonstrate a statistically significant relationship (e.g., p < 0.1) with an independent gradient of human disturbance, such as the percentage of agricultural land use in a catchment. [26] [25]

- Redundancy Check: To avoid compounding error, metrics with strongly correlated residuals from their relationship with disturbance are excluded, ensuring each selected metric contributes unique information. [25]

Index Validation and Application Protocol

Once an MMI is constructed, its validity and applicability must be rigorously tested before it can be trusted for environmental monitoring. The protocol for this phase is outlined below.

Key validation steps include [26] [34]:

- Correlation with Stressors: A strong negative relationship between the MMI score and physicochemical variables (e.g., nutrient levels) or human disturbance factors confirms the index's sensitivity. [26]

- Site Discrimination: The MMI must effectively differentiate between least-disturbed (reference) and heavily-impaired sites. Studies show validated MMIs can achieve performance rates of 83.3% for correctly classifying reference sites. [5]

- Independent Validation: Applying the MMI to a separate dataset is crucial for testing its stability and real-world applicability, a process known as model stability analysis. [35] [5]

- Status Classification: Finally, thresholds are set to translate the continuous MMI score into ecological condition categories (e.g., Poor, Fair, Good), often based on the distribution of scores in least-disturbed reference sites. [33]

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The development and application of a robust MMI rely on a suite of "research reagents"—both conceptual and physical. The following table details these essential components and their functions in the MMI development process.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for MMI Development

| Category | Item/Concept | Function in MMI Development |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Assemblage | Macroinvertebrate Communities | Primary source of candidate metrics; ideal due to differential pollution tolerance, sedentary nature, and key role in ecosystem function. [26] [34] [36] |

| Reference Framework | Least-Disturbed Reference Sites | Provide the baseline "healthy" conditions; used to calibrate metrics and set expectations for biological integrity in the absence of significant human impact. [25] [33] |

| Stressor Quantification | Disturbance Gradient Index | An independent measure of human pressure (e.g., % agricultural land use, water chemistry); essential for testing metric responsiveness and validating the final MMI. [26] [25] |

| Statistical Software | R or Python with specialized packages | Used for multivariate analyses (PCA, CFA), correlation tests, model competition frameworks, and the random generation of candidate MMIs. [35] [25] |

| Field Equipment | D-nets, Kick-nets, Sample Preservation Kits | For standardized collection and preservation of biological samples (e.g., macroinvertebrates) to ensure data consistency and comparability. [26] |

Implementation Guide for Researchers

Selecting the appropriate methodology depends on the research context. The index-based approach is superior for maximizing the statistical power and sensitivity of the final index, as evidenced by experimental data. [25] However, the metric-based approach remains a valid and more straightforward option for more constrained projects. Regardless of the chosen path, employing a continuous scoring system (0-10) for individual metrics enhances the precision and interpretability of the results. [5]

When working in agricultural landscapes, specific metrics have proven highly responsive. These include traits related to tolerant taxa (e.g., Chironomidae/Diptera abundance), sensitive taxa (e.g., %Odonata), and community structure (e.g., Margalef index, Oligochaete richness). [5] [36] Finally, validation is not optional. The "Estuarine Quality Paradox"—where naturally stressful conditions mimic anthropogenic stress—highlights the challenge in transitional waters, reinforcing the need for multi-index approaches and rigorous, site-specific validation. [1]

The validation of biotic indices is paramount for accurately diagnosing the ecological impacts of agriculture on riverine ecosystems. A critical component in constructing these indices is the scoring system used to transform raw biological data into a standardized, unitless value that reflects ecosystem health. The choice between continuous and discrete scoring methods is not merely a technicality but a fundamental decision that influences the sensitivity, accuracy, and ultimate utility of an index of biotic integrity (IBI). Biotic indices based on assemblages such as benthic macroinvertebrates are widely used because these organisms provide a cumulative record of environmental stress and are highly sensitive to local pollution, habitat alteration, and diffuse agricultural runoff [37] [36].

The core distinction between the two methods lies in how they handle the transformation of metric values. Discrete scoring, first pioneered by Karr in 1981, assigns a series of categorical scores (e.g., 1, 3, or 5) to predefined ranges of metric values, where a score of 5 typically represents an undisturbed or least-disturbed condition [37]. In contrast, continuous scoring relies on setting upper and lower thresholds, or expectations, based on the statistical distribution of values. Metric values falling between these thresholds are scored on a continuous scale as fractions of the expected value, allowing for more granular differentiation between sites [37] [38]. This comparative guide examines the performance characteristics of both approaches within the context of agricultural impact assessment, providing researchers with the empirical data needed to select an appropriate methodology.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Discrete Scoring Method

The discrete scoring method, also known as discrete scaling, is characterized by its use of a limited set of possible scores. This approach segments the range of possible metric values into distinct categories, each corresponding to a single score.

- Core Principle: This method assigns a series of categorical scores to specific ranges of metric values, severely limiting the number of possible outcomes for each metric [37]. For instance, a metric might be assigned a score of 5 for values indicative of reference conditions, 3 for moderately impaired conditions, and 1 for severely impaired conditions.

- Statistical Nature: It produces discrete data, which is characterized by specific, separate values that cannot be meaningfully subdivided. You count discrete data, and its results are often integers, though averages can be fractional [39].

- Application in IBI Development: In the development of a benthic macroinvertebrate-based IBI (B-IBI) for the Poyang Lake wetland, discrete scoring was one of the methods applied for metric scoring, demonstrating its real-world applicability in assessing wetland health degraded by anthropogenic pressures [37].

Continuous Scoring Method

The continuous scoring method offers a more fluid approach by calculating a score based on a metric's position relative to established benchmarks.

- Core Principle: This method sets upper and lower thresholds based on the statistical distribution of metric values (e.g., percentiles from reference sites). The actual score for a metric is then calculated as a continuous function between these thresholds, resulting in a spectrum of possible scores [37] [38].

- Statistical Nature: It generates continuous data, which can assume any numeric value within a range and can be meaningfully split into smaller parts. This data type has an infinite number of potential values between any two points and is typically measured rather than counted [39].

- Application in IBI Development: A performance comparison of metric scoring methods for a multimetric index in Mid-Atlantic highlands streams found that a specific continuous method—using continuous scaling and setting expectations with the 95th percentile of the entire site distribution—outperformed other discrete and continuous variants [38].

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison of Discrete and Continuous Scoring Methods

| Feature | Discrete Scoring | Continuous Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Assigns categorical scores to value ranges [37] | Calculates scores as a function of distance between thresholds [37] |

| Number of Possible Scores | Limited (e.g., 1, 3, 5) [37] | Essentially infinite within the bounds |

| Data Type Produced | Discrete Data [39] | Continuous Data [39] |

| Handling of Intermediate Values | Groups them into a category with a single score | Assigns a unique, fractional score |

| Statistical Simplicity | Simple to calculate and communicate | More complex, requires defining a scoring function |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Empirical studies directly comparing scoring methods have provided evidence-based insights into their relative strengths and weaknesses, particularly regarding the responsiveness and variability of the final multimetric index.

Index Responsiveness and Discrimination Power

A study in the Poyang Lake wetland developed a B-IBI and applied two scoring and three classification methods. The results were striking: health status assessments varied considerably among the various metric scoring and classification methods [37]. This finding underscores the critical importance of method selection, as different choices can lead to different conclusions about the ecological state of a water body. The Poyang Lake study concluded that standardizing these methods is essential for comparing assessment results across different areas and time periods [37].

A more focused comparison was conducted for the Macroinvertebrate Biotic Integrity Index (MBII) in Mid-Atlantic highlands streams. This research evaluated six metric scoring methods using specific performance measures, including the degree of overlap between impaired and reference distributions and the relationships to a stressor gradient [38]. The study concluded that the method of scoring metrics significantly affects the properties of the final index, particularly its variability, which in turn influences the number of condition classes (e.g., unimpaired, impaired) an index can reliably distinguish [38].

Index Variability and Statistical Properties

The Mid-Atlantic highlands study revealed that measures of index variability were affected to a greater degree than index responsiveness by the choice of scoring method. Specifically, both the type of scaling (discrete or continuous) and the method for setting metric expectations influenced the index's temporal variability and the minimum detectable difference [38]. These properties are crucial for monitoring programs that aim to detect changes in ecological status over time, whether for assessing restoration success or tracking further degradation.

The best-performing method in the Mid-Atlantic study used continuous scaling and set metric expectations using the 95th percentile of the entire distribution of sites. This approach achieved the best overall performance for the MBII, demonstrating the potential superiority of continuous methods under specific conditions [38].

Table 2: Empirical Performance Comparison from Scientific Studies

| Performance Metric | Discrete Scoring Findings | Continuous Scoring Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Health Status Classification | Leads to varying assessment results depending on the method used [37] | Leads to varying assessment results depending on the method used [37] |

| Overlap between Impaired/Reference | Performance varies; generally less discriminating in the Mid-Atlantic study [38] | The 95th percentile continuous method showed superior discrimination [38] |

| Relationship to Stressor Gradient | Responsiveness is less affected by scoring type than variability is [38] | Responsiveness is less affected by scoring type than variability is [38] |

| Temporal Variability | Affected by both scaling type and expectation setting method [38] | Affected by both scaling type and expectation setting method; best method had favorable variability [38] |

| Minimum Detectable Difference | Generally higher (less sensitive) for discrete methods [38] | Can be lower (more sensitive) with optimized continuous methods [38] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

For researchers seeking to validate or compare scoring methods, adhering to a structured experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow, derived from the methodologies of the cited studies, provides a robust framework for such comparisons.

Study Design and Site Selection

The initial phase involves establishing a rigorous experimental design capable of testing the discriminatory power of different scoring systems.

- Step 1: Define Study Area and Stressor Gradient: Clearly delineate the geographical scope of the study. A critical component is establishing a stressor gradient related to agricultural intensity. This can be quantified using proxies such as the percentage of agricultural land use in the sub-catchment, pesticide and nutrient application data, or a composite agricultural intensity index [11]. For example, a Pan-European study found that incorporating an agricultural intensity index nearly doubled the correlation strength between agriculture and the ecological status of rivers compared to using the simple share of agriculture in the sub-catchment [11].

- Step 2: Select Reference and Impaired Sites: Identify and select sites across the stressor gradient. Reference sites should be located in least-disturbed conditions, representing the best achievable ecological state. Impaired sites should be selected to represent a range of anthropogenic pressures, particularly from different agricultural types (e.g., intensive cropland, livestock farming) [37] [36]. A meta-analysis on agricultural land use effects confirmed the importance of this step, noting that biotic responses differ markedly based on the agricultural types and practices present in the catchment [36].

Data Collection and Metric Calculation

This phase involves gathering the fundamental biological data that will be processed using the different scoring methods.