Validating Hierarchical Cluster Analysis for Groundwater Quality Classification: A Comprehensive Framework for Researchers

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) has emerged as a powerful, data-driven tool for identifying natural groupings in complex groundwater quality datasets, moving beyond traditional graphical methods.

Validating Hierarchical Cluster Analysis for Groundwater Quality Classification: A Comprehensive Framework for Researchers

Abstract

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) has emerged as a powerful, data-driven tool for identifying natural groupings in complex groundwater quality datasets, moving beyond traditional graphical methods. This article provides a comprehensive validation framework for HCA, addressing its foundational principles, methodological application to hydrochemical data, troubleshooting of common pitfalls, and rigorous performance validation against other techniques. By synthesizing current research and best practices, we equip environmental scientists and hydrologists with the knowledge to reliably apply HCA for robust groundwater quality classification, pattern recognition, and informed water resource management decisions.

Understanding Hierarchical Cluster Analysis and Its Role in Hydrogeology

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) is a fundamental method of unsupervised machine learning that builds a hierarchy of clusters to group similar data points based on their distance or similarity [1]. Unlike partitioning methods that require pre-specifying the number of clusters, HCA organizes data into a tree-like structure called a dendrogram, which reveals nested clustering patterns at different levels of granularity [2]. This characteristic makes HCA particularly valuable for exploratory data analysis in scientific research, including groundwater quality classification, where natural groupings may not be known in advance.

In groundwater quality research, HCA serves as a powerful tool for identifying patterns and relationships within complex hydrochemical datasets. By analyzing parameters such as pH, electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids, and concentrations of elements like iron and arsenic, researchers can classify water samples into distinct quality groups based on their chemical characteristics [3]. This classification provides critical insights for environmental monitoring, contamination source identification, and public health risk assessment, forming an essential component of water resource management strategies.

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

The Dendrogram: Visualizing Cluster Hierarchies

A dendrogram serves as the primary visualization tool for hierarchical clustering, functioning as a "family tree for clusters" that illustrates how individual data points or groups merge or split at different similarity levels [2]. In this tree-like diagram, the vertical axis represents the distance or dissimilarity at which clusters combine, while the horizontal axis displays the data points. The height of the connection points between clusters indicates their similarity—lower merge points signify greater similarity between clusters [4] [2].

Interpreting a dendrogram involves identifying the natural cutoff points where branches become significantly longer, indicating less similar clusters are being merged. Researchers can determine the optimal number of clusters by drawing a horizontal line across the dendrogram and counting how many vertical lines it intersects [1]. This visual approach allows scientists to make informed decisions about cluster selection based on their research objectives and the inherent structure of the data.

Distance Metrics and Dissimilarity Measures

The foundation of hierarchical clustering lies in quantifying the similarity or dissimilarity between data points through distance metrics. These metrics determine how the algorithm calculates proximity in the feature space:

- Euclidean Distance: The straight-line distance between two points, most suitable for continuous variables with similar scales [1]

- Manhattan Distance: The sum of absolute differences along coordinate axes, less sensitive to outliers than Euclidean distance [1]

- Minkowski Distance: A generalized metric that includes both Euclidean and Manhattan as special cases [1]

- Hamming Distance: Used for categorical data, measuring the number of positions at which corresponding symbols differ [1]

- Mahalanobis Distance: Accounts for correlations between variables and is scale-invariant [1]

In groundwater quality studies, the choice of distance metric significantly impacts clustering results. For example, when analyzing parameters with different measurement units (e.g., pH, conductivity in μS/cm, and element concentrations in mg/L), data standardization is often necessary before applying distance calculations to prevent variables with larger scales from dominating the cluster solution [3].

Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering

Theoretical Framework and Algorithm

Agglomerative clustering, often referred to as the "bottom-up" approach, begins with each data point as an individual cluster and successively merges the most similar pairs of clusters until all data points unite into a single cluster [4] [1]. This method follows a greedy strategy, making locally optimal choices at each merge step without reconsidering previous decisions [1]. The algorithm maintains a dissimilarity matrix that tracks distances between clusters, updating it after each merge operation.

The standard agglomerative clustering algorithm has a time complexity of O(n³) for naive implementations, though more efficient implementations can achieve O(n²) time complexity using priority queues [4]. The space complexity is O(n²) due to the storage requirements of the distance matrix [4]. These computational characteristics make agglomerative clustering suitable for small to medium-sized datasets, typically up to several thousand observations, which aligns well with typical groundwater quality datasets.

Linkage Criteria: Determining Cluster Similarity

The linkage criterion defines how the distance between clusters is calculated and profoundly influences the shape and compactness of the resulting clusters. The most common linkage methods include:

Single Linkage (Minimum Linkage) This method uses the minimum distance between any two points in different clusters [4] [1]. Represented as mina∈A,b∈Bd(a,b), single linkage can handle non-elliptical shapes but is sensitive to noise and outliers, potentially creating "chains" that connect distinct clusters through bridging points [1].

Complete Linkage (Maximum Linkage) This approach uses the maximum distance between any two points in different clusters [4] [1]. Expressed as maxa∈A,b∈Bd(a,b), complete linkage tends to produce more compact, spherical clusters and is less sensitive to noise but may struggle with large, irregularly shaped clusters [1].

Average Linkage This method calculates the average distance between all pairs of points in different clusters [4] [1]. The unweighted version (UPGMA) uses 1|A|·|B|∑a∈A∑b∈Bd(a,b), while the weighted version (WPGMA) employs d(i∪j,k)=d(i,k)+d(j,k)2. Average linkage offers a balanced approach between single and complete linkage [1].

Ward's Method This approach minimizes the total within-cluster variance by evaluating the increase in the sum of squares when clusters are merged [4] [1]. The formula is expressed as |A|·|B||A∪B|‖μA−μB‖2=∑x∈A∪B‖x−μA∪B‖2−∑x∈A‖x−μA‖2−∑x∈B‖x−μB‖2. Ward's method often produces clusters of relatively equal size and is well-suited for quantitative variables commonly found in groundwater quality data [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Linkage Methods in Agglomerative Clustering

| Linkage Method | Mathematical Formula | Cluster Shape Tendency | Sensitivity to Noise | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | mina∈A,b∈Bd(a,b) | Elongated, chain-like | High | Non-elliptical shapes, outlier detection |

| Complete Linkage | maxa∈A,b∈Bd(a,b) | Compact, spherical | Low | Well-separated globular clusters |

| Average Linkage | 1∣A∣·∣B∣∑a∈A∑b∈Bd(a,b) | Balanced, intermediate | Moderate | General purpose, mixed cluster shapes |

| Ward's Method | ∣A∣·∣B∣∣A∪B∣‖μA−μB‖2 | Approximately equal size | Low | Quantitative variables, hydrological data |

Workflow Implementation

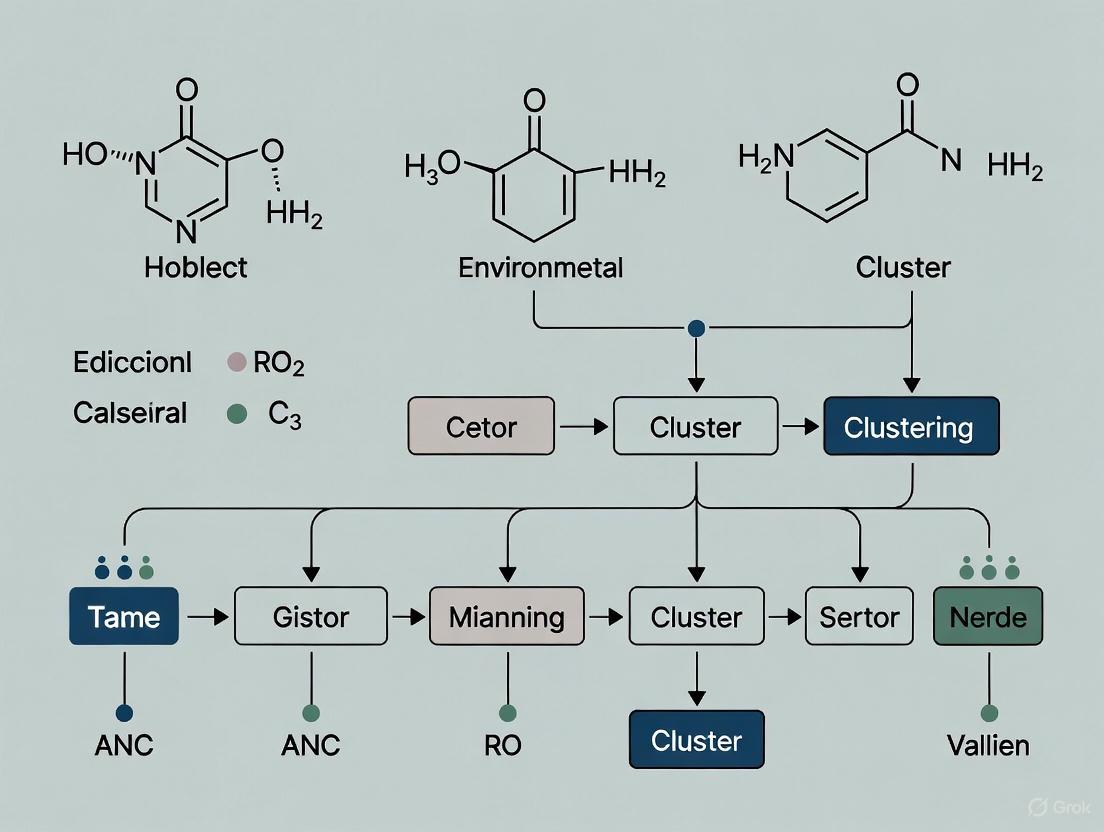

The agglomerative clustering process follows a systematic workflow that can be visualized and implemented as follows:

Agglomerative Clustering Workflow

The implementation begins with each of the n data points as individual clusters, followed by computation of an n×n dissimilarity matrix using an appropriate distance metric [2]. The algorithm then iteratively identifies and merges the two closest clusters based on the selected linkage criterion, updates the distance matrix to reflect the new cluster structure, and continues this process until all points unite into a single cluster or a stopping criterion is met [1] [2]. Throughout this process, the algorithm records the merge history and distances, enabling the construction of a dendrogram that visualizes the complete clustering hierarchy.

Divisive Hierarchical Clustering

Theoretical Framework and Algorithm

Divisive clustering, known as the "top-down" approach, begins with all data points contained within a single cluster and recursively partitions the data into smaller clusters until each point forms its own cluster or a stopping criterion is satisfied [4] [1]. This method follows a strategy opposite to agglomerative clustering, starting with the complete dataset and successively splitting it into finer partitions.

The computational complexity of divisive clustering is significantly higher than agglomerative approaches. While a naive implementation with exhaustive search has a complexity of O(2^n), practical implementations using flat clustering algorithms like k-means for splitting operations can achieve better performance [4] [1]. Divisive methods are particularly effective for identifying large, distinct clusters early in the process and can be more accurate than agglomerative methods because the algorithm considers the global data distribution from the outset [1].

Splitting Criteria and Methods

The key operation in divisive clustering is determining how to split clusters at each stage. The most common approach uses the k-means algorithm (with k=2) to bipartition clusters [1]. This method works by:

- Identifying the largest cluster or the cluster with the greatest internal variance

- Applying k-means with k=2 to partition the selected cluster into two subsets

- Evaluating the quality of the split based on within-cluster sum of squares (inertia)

- Retaining the split if it improves the overall clustering structure

Alternative splitting criteria include:

- Maximum diameter splitting: Selecting the cluster with the largest diameter (maximum distance between any two points) for division

- Principal direction splitting: Using principal component analysis to identify the direction of maximum variance for splitting

- Minimum similarity splitting: Dividing the cluster based on the pair of points with the greatest dissimilarity

The DIANA (Divisive ANAlysis clustering) algorithm, developed by Kaufman and Rousseeuw, represents one of the most well-known implementations of divisive hierarchical clustering [1]. This algorithm selects clusters for splitting based on their diameter and uses a typicality measure to determine the optimal division point.

Workflow Implementation

The divisive clustering process follows this systematic workflow:

Divisive Clustering Workflow

The implementation begins with all data points in a single cluster, then iteratively selects the most appropriate cluster for splitting based on criteria such as size, diameter, or variance [1] [2]. The selected cluster is divided using a bipartitioning method like k-means with k=2, and the quality of the split is evaluated using measures such as the inertia criterion (within-cluster sum of squares) [1]. This process continues until each data point forms its own cluster or a predefined stopping condition (such as a specific number of clusters) is met, with the entire splitting history recorded for dendrogram construction [2].

Comparative Analysis: Agglomerative vs. Divisive Approaches

Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

Table 2: Direct Comparison Between Agglomerative and Divisive Hierarchical Clustering

| Characteristic | Agglomerative Clustering | Divisive Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Approach | Bottom-up: starts with individual points | Top-down: starts with complete dataset |

| Initial State | n singleton clusters | One cluster containing all n points |

| Computational Complexity | O(n³) naive, O(n²) with optimization | O(2^n) naive, better with k-means splitting |

| Memory Requirements | O(n²) for distance matrix | Varies, typically lower than agglomerative |

| Sensitivity to Initial Choices | Low (deterministic with fixed linkage) | Moderate (depends on splitting method) |

| Cluster Shape Identification | Better for small, local clusters | Better for large, global clusters |

| Handling of Outliers | Sensitive with single linkage | More robust with appropriate splitting |

| Implementation Prevalence | More commonly used | Less common but growing |

| Optimal Use Cases | Small to medium datasets, local patterns | Larger datasets, global structure identification |

Performance Evaluation in Groundwater Quality Context

In groundwater quality classification research, the choice between agglomerative and divisive approaches depends on specific research objectives and dataset characteristics. Agglomerative methods have demonstrated effectiveness in identifying local contamination patterns, where the gradual merging of clusters reveals subtle relationships between sampling sites with similar hydrochemical characteristics [3]. For example, in a study of tubewell water in Bangladesh, agglomerative clustering successfully identified regions with similar iron and arsenic contamination patterns, revealing 68% and 48% of samples exceeded WHO and USEPA limits for Fe and As, respectively [3].

Divisive methods offer advantages when the research goal is to identify major hydrochemical facies or distinct water types before examining finer subdivisions. This approach can more efficiently separate major groundwater groups based on dominant ions or contamination levels, then progressively refine the classification [1]. The global perspective of divisive clustering makes it particularly valuable for identifying regional-scale patterns in groundwater quality, such as separating anthropogenically influenced samples from those reflecting natural geochemical processes.

Table 3: Experimental Comparison in Groundwater Quality Studies

| Performance Metric | Agglomerative Clustering | Divisive Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy in IdentifyingContamination Hotspots | 87% accuracy in ANN modelswith hierarchical features [3] | Limited experimental datain groundwater studies |

| Computational Efficiency | Suitable for typical groundwaterdatasets (75-200 samples) [3] | More efficient for identifyingmajor water types first |

| Handling of CorrelationBetween Parameters | Effectively manages TDS-ECcorrelation (r=0.92) [3] | Better preserves globalcorrelation structure |

| Identification ofSpatial Patterns | Successfully mapped Fe and Ashotspots in SW Bangladesh [3] | Potentially better forregional-scale patterns |

| Sensitivity toMeasurement Units | Requires data standardizationfor mixed parameter units | Same standardizationrequirements |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for Groundwater Quality Clustering

Implementing hierarchical clustering for groundwater quality classification requires a systematic methodology to ensure reproducible and scientifically valid results. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect water samples following standardized sampling procedures to prevent contamination

- Measure key parameters including pH, electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS), and specific contaminants (e.g., Fe, As) using approved analytical methods [3]

- Compile data into a structured matrix with samples as rows and parameters as columns

- Address missing values through appropriate imputation methods or exclusion

- Standardize data to mean=0 and variance=1 to prevent scale-dependent clustering

2. Dissimilarity Matrix Computation

- Select appropriate distance metric based on data characteristics (Euclidean for continuous variables, Manhattan for outlier-prone data)

- Compute pairwise distances between all samples to form dissimilarity matrix

- Verify matrix symmetry and non-negativity properties

3. Clustering Execution

- Choose between agglomerative or divisive approach based on research questions

- Select linkage criterion (for agglomerative) or splitting method (for divisive)

- Implement clustering algorithm with recording of merge/split history

- Construct dendrogram to visualize hierarchical relationships

4. Cluster Validation and Interpretation

- Determine optimal cluster number using the elbow method or gap statistic [1]

- Validate cluster stability through internal measures (silhouette index) or external validation (known classifications)

- Interpret clusters based on centroid values and identify characteristic parameters for each cluster

- Map spatial distribution of clusters if location data available

Validation Framework for Groundwater Clustering

Validating clustering results is essential for ensuring scientific rigor in groundwater quality classification:

Internal Validation Measures

- Silhouette Width: Measures how similar an object is to its own cluster compared to other clusters (-1 to +1, higher better)

- Dunn Index: Ratio between minimal inter-cluster distance to maximal intra-cluster distance (higher better)

- Within-Cluster Sum of Squares: Measures compactness of clusters (lower better)

External Validation (when reference classification exists)

- Adjusted Rand Index: Measures similarity between two clusterings, adjusted for chance

- F-Measure: Harmonic mean of precision and recall for cluster comparison

- Jaccard Similarity: Compares common elements between cluster pairs

Stability Assessment

- Bootstrap Methods: Resample data with replacement and examine cluster consistency

- Subsampling Approaches: Repeatedly cluster random subsets and measure agreement

In the Bangladesh groundwater study, researchers complemented hierarchical clustering with artificial neural network (ANN) modeling, achieving 87% accuracy in estimating safe water intake levels based on cluster-derived features [3]. This integration of unsupervised and supervised methods represents a robust validation approach for practical applications.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Computational Tools and Software

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Hierarchical Clustering Research

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application in Groundwater Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python Scikit-learn | Machine learning library | AgglomerativeClustering implementation | from sklearn.cluster import AgglomerativeClustering |

| SciPy Hierarchy Module | Hierarchical clustering | Dendrogram visualization and linkage computation | from scipy.cluster.hierarchy import dendrogram, linkage |

| R hclust function | Statistical clustering | Comprehensive hierarchical clustering implementation | hclust(d, method="ward.D2") |

| MATLAB Cluster Analysis | Algorithm implementation | Pattern recognition in multivariate data | Z = linkage(data,'ward','euclidean') |

| IBM SPSS Statistics | Statistical analysis | GUI-based clustering for non-programmers | Analyze > Classify > Hierarchical Cluster |

| PAST Software | Paleontological statistics | User-friendly multivariate analysis | Specifically designed for scientific data |

Analytical Instruments and Laboratory Materials

For groundwater quality studies employing hierarchical clustering, the following field and laboratory materials are essential:

Field Sampling Equipment

- Water Sampling Bottles: HDPE or glass containers of appropriate volumes (250ml-1000ml) for element analysis

- Portable Measurement Devices: pH meter, conductivity meter, and multiparameter water quality probes for in-situ measurements

- Sample Preservation Kits: Chemical preservatives (HCl for metals, cool packs for temperature maintenance) to maintain sample integrity

- GPS Equipment: For precise location mapping of sampling points for spatial cluster analysis

Laboratory Analytical Instruments

- Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS): For precise measurement of heavy metals (Fe, As, etc.) in water samples [3]

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS): For multi-element analysis at trace concentrations

- Ion Chromatograph: For anion and cation analysis relevant to water quality assessment

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: For colorimetric determination of specific parameters like arsenic using test kits [3]

Reference Materials and Reagents

- Certified Reference Materials: Standard solutions with known concentrations for instrument calibration

- Quality Control Standards: Laboratory-fortified blanks and duplicates for data quality assurance

- Chemical Reagents: Acids, buffers, and developing reagents for specific analytical methods

The Bangladesh groundwater study utilized Hanna Iron Checker and Hach Arsenic Test Kit for field screening, complemented by more sophisticated laboratory analyses for validation [3]. This combination of field and laboratory methods ensures both practical feasibility and scientific accuracy in data collection for clustering analysis.

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis offers a powerful methodological framework for groundwater quality classification, providing researchers with flexible tools to identify natural groupings in complex hydrochemical datasets. The agglomerative approach, with its bottom-up methodology, excels at revealing local patterns and gradual transitions between water quality classes, while the divisive approach offers advantages in identifying major hydrochemical facies before examining finer subdivisions.

The application of HCA in groundwater quality research, as demonstrated in the Bangladesh study, enables evidence-based decision-making for water resource management, contamination source identification, and public health protection [3]. By following standardized experimental protocols and implementing appropriate validation frameworks, researchers can generate robust clustering solutions that advance our understanding of hydrochemical systems and support environmental policy development.

As computational methods continue to evolve, the integration of hierarchical clustering with other multivariate techniques, machine learning approaches, and spatial analysis will further enhance its utility in environmental research. The continued refinement of these methods promises more sophisticated approaches to water quality assessment and management in increasingly complex hydrogeological settings.

Why HCA for Groundwater? Addressing the Limitations of Traditional Classification Methods like Piper Diagrams

In the field of hydrogeology, accurately classifying groundwater is crucial for understanding its chemical evolution, pollution sources, and suitability for use. For decades, traditional graphical methods like Piper diagrams have been the standard for hydrochemical classification. However, the increasing complexity of environmental datasets has exposed significant limitations in these conventional approaches. This guide objectively compares these traditional methods with Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA), a multivariate statistical technique, using supporting experimental data to validate HCA's efficacy for modern groundwater quality classification research.

Limitations of Traditional Classification Methods

Traditional hydrochemical classification methods, including Piper diagrams and Schuka Lev classification, have provided a valuable foundation for understanding water chemistry. However, their effectiveness is constrained by several inherent drawbacks when faced with complex, modern datasets.

Subjectivity and Simplification: Piper diagrams plot only a few major anions and cations, which can lead to vague and ineffective classification as they obscure the inherent fuzziness in water quality data [5]. The resulting classifications can be broad and lack the detail needed to discern subtle differences between water samples.

Limited Parameter Utilization: Methods like the Schuka Lev classification rely on a subjective predetermined threshold (in milliequivalents) for ions. This approach does not detailedly capture water quality variations and can be insensitive to the combined effects of multiple chemical parameters [5].

Inability to Handle Complex Data: Traditional methods are susceptible to limited and biased results when a study relies solely on a single one of them. They are less diversified and are constrained to limited objects and conditions, often leading to poor accuracy and reliability [5]. Consequently, they are frequently used in complement or combined with other methods to solve practical problems.

The HCA Alternative: Principles and Advantages

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) is a multivariate statistical technique that groups a set of objects in such a way that objects in the same group (called a cluster) are more similar to each other than to those in other groups [6]. In groundwater studies, these "objects" are water samples, and their "similarity" is determined based on multiple hydrochemical parameters simultaneously.

Key Advantages of HCA

- Comprehensive Data Utilization: HCA can process and extract useful information from complex, high-dimensional datasets, incorporating a wide array of physical and chemical parameters beyond just major ions [5].

- Objective Classification: It provides a data-driven, objective framework for classifying groundwater samples, eliminating the subjectivity associated with interpreting traditional diagrams [7].

- Revealing Hidden Patterns: HCA can identify internal relationships and hidden patterns within data that may not be apparent through graphical methods, such as revealing hydraulic connections, recharge sources, and transport laws of groundwater [5].

Experimental Workflow for HCA in Groundwater Studies

The standard methodology for applying HCA in groundwater research involves a structured process, from field sampling to statistical interpretation. The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the logical relationship between each step.

Experimental Data: Direct Performance Comparison

A comparative study of leakage water samples from the Bayi Tunnel in Chongqing directly evaluated six different HCA methods against the limitations of traditional approaches [5].

Experimental Protocol

- Sample Collection: 19 groups of water samples were collected, including precipitation, underground sewer water, bedrock fissure water, and leakage water from multiple points in the tunnel [5].

- Chemical Analysis: Samples were analyzed for major cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) and anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻, CO₃²⁻, F⁻, NO₃⁻), as well as pH, temperature, and electrical conductivity (EC). Cations were measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES), and anions were analyzed with an Ion Chromatograph (IC) [5].

- Data Processing: The hydrochemical data were subjected to six different HCA linkage methods: Single Linkage, Complete Linkage, Median Linkage, Centroid Linkage, Average Linkage (between-group and within-group), and Ward's Minimum-Variance [5].

Quantitative Performance of HCA Methods

Table 1: Comparison of HCA Method Performance for Groundwater Classification [5]

| HCA Method | Accuracy & Reliability | Sample Size Suitability | Key Limitations | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | Poor | Not Specified | Unsuitable for complex practical conditions | Not recommended for complex groundwater data |

| Complete Linkage | Poor | Not Specified | Unsuitable for complex practical conditions | Not recommended for complex groundwater data |

| Median Linkage | Moderate | Not Specified | Likely causes reversals in dendrograms | Use with caution; can distort cluster relationships |

| Centroid Linkage | Moderate | Not Specified | Likely causes reversals in dendrograms | Use with caution; can distort cluster relationships |

| Average Linkage | Good | Multiple samples and big data | Fewer limitations for large datasets | General purpose for large, complex datasets |

| Ward's Minimum-Variance | Better (Optimal) | Fewer samples and variables | May be less suitable for very large datasets | Optimal for studies with limited sample sizes |

The study concluded that Ward's minimum-variance method achieved better results for fewer samples and variables, while average linkage was generally suitable for classification tasks with multiple samples and big data [5].

Case Study: HCA in Groundwater Quality Index Development

The development of a Groundwater Quality Index (GWQI) for the aquifers of Bahia, Brazil, provides a compelling case for HCA's practical application and superiority [7].

Experimental Protocol and HCA Workflow

- Initial Data Collection: 600 wells across four hydrogeological domains (sedimentary, crystalline, karstic, and metasedimentary) were sampled, analyzing 26 water quality parameters [7].

- Data Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) extracted 5 factors sufficient to explain the cumulative variance in the data [7].

- Parameter Selection via HCA: A dendrogram generated from HCA was used to objectively select the most representative parameters for the GWQI, ultimately identifying hardness, total residue, sulphate, fluoride, and iron [7].

- Index Formulation: Relative weights for each parameter were determined based on their communality values, and the GWQI was calculated using a multiplicative formula similar to the NSF-WQI [7].

Comparative Outcomes

This HCA-based approach demonstrated key advantages over traditional methods:

- Objectivity: HCA provided a rational, data-driven method for selecting parameters and assigning weights, eliminating the subjective assessments that often plague traditional WQI development [7].

- Efficiency: By identifying the most significant parameters, HCA reduced the number of variables needed for ongoing monitoring from 26 to 5, saving time, effort, and cost without sacrificing informational value [7].

- Accuracy: The spatialization of 1369 GWQI values across the state of Bahia showed a good correlation between the groundwater quality and the index quality classification, validating the HCA-based methodology [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hydrochemical and HCA Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dilute Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Sample preservation for cation analysis; added until pH < 2 to prevent precipitation and adsorption onto container walls. | Used in the Bayi Tunnel study for cation sample preservation [5]. |

| Polyethylene Sample Bottles | Inert containers for water sample collection and storage, pre-cleaned with distilled water to prevent contamination. | Standard practice for groundwater sampling [5] [6]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) Standard Solution (0.05 mol/L) | Titration for determining bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) alkalinity in water samples. | Used in the Dehui City study for bicarbonate measurement [8]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) Solution | Titration for determining chloride (Cl⁻) concentration in water samples. | A standard method for chloride analysis [9]. |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) Eluents | Mobile phase for separation and quantification of anions (Cl⁻, F⁻, NO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻) and cations. | Used for anion analysis in the Bayi Tunnel study [5]. |

Integrated Approaches: HCA with Complementary Multivariate Techniques

While powerful alone, HCA is most effective when integrated with other multivariate statistical techniques, forming a robust analytical framework for groundwater studies.

HCA and Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A study in Dehui City, China, successfully combined HCA and PCA to characterize groundwater systems [8]. HCA was used to classify 217 groundwater samples into hydrochemical groups, while PCA helped identify the underlying factors controlling water chemistry, such as water-rock interaction and anthropogenic pollution [8]. This synergy simplifies complex datasets and reveals the main mechanisms driving hydrogeochemical composition.

HCA for Aquifer Response Characterization: Research in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, applied HCA innovatively to groundwater level fluctuation patterns rather than chemical data [10]. Using Pearson’s correlation coefficient as a similarity measure, HCA classified observation wells into five distinct clusters based on their hydrograph responses. This classification corresponded perfectly with basic lithology distribution and sedimentary age, providing newer insights into aquifer behavior and pumping effects [10]. This demonstrates HCA's versatility beyond pure hydrochemistry.

The experimental data and case studies presented provide compelling evidence for adopting HCA in groundwater research.

- Addressing Traditional Limitations: HCA successfully overcomes the key shortcomings of traditional methods like Piper diagrams by handling complex, multi-parameter datasets objectively and without information loss [5].

- Methodological Superiority: Among HCA methods, Ward's minimum-variance and average linkage have been validated as particularly effective for groundwater studies, depending on sample size [5].

- Practical Utility: From developing accurate Water Quality Indices [7] to characterizing aquifer dynamics [10], HCA provides a robust, rational framework for groundwater classification that aligns with the goals of modern, data-driven hydrogeology.

For researchers and scientists, mastering HCA is no longer just an option but a necessity for advancing groundwater quality classification beyond the limitations of 20th-century graphical methods into the realm of 21st-century data science.

Within the framework of research validating hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) for groundwater quality classification, the interpretation of dendrograms and cluster structures is a fundamental competency. These graphical and structural outputs are not merely illustrations; they are the core results of the analysis, providing an objective basis for classifying water samples into hydrochemically distinct groups. This guide objectively compares the performance and output of different HCA methodologies, supported by experimental data from hydrochemical studies. The correct selection and interpretation of HCA methods enable researchers to decipher complex hydrochemical datasets, identify the sources and processes influencing water composition, and validate these classifications against other multivariate statistical techniques [11] [12].

Comparative Analysis of HCA Method Performance

The choice of HCA method significantly influences the structure of the dendrogram and the resulting hydrochemical classification. Different linkage algorithms make varying assumptions about cluster similarity, leading to distinct performance characteristics suited to specific types of data and research objectives. The following table synthesizes findings from a comparative study of six hierarchical cluster analysis methods, outlining their advantages, disadvantages, and ideal application contexts in hydrochemical research [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) Methods for Hydrochemical Classification

| HCA Method | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | - | - Highly susceptible to "chaining"- Unsuitable for complex practical conditions | Complex hydrochemical datasets with noisy or irregular cluster shapes [11] |

| Complete Linkage | - | - Tends to find compact, spherical clusters- Unsuitable for complex practical conditions | - |

| Average Linkage | - Generally suitable for multiple samples and big data- Robust to outliers | - | Classification tasks with multiple samples and large datasets [11] |

| Ward's Minimum-Variance | - Achieves better results for fewer samples and variables- Minimizes within-cluster variance | - Tends to create clusters of similar size | Datasets with fewer samples and variables; creates clusters of roughly equal size [11] [13] |

| Median Linkage | - | - Likely causes reversals in dendrograms- Less computationally intensive | - |

| Centroid Linkage | - | - Likely causes reversals in dendrograms- Interpretational challenges | - |

Beyond the linkage algorithm, the entire analytical workflow from data preparation to validation is critical for generating meaningful and interpretable dendrograms. The process involves multiple stages, each with specific considerations for ensuring the resulting cluster structure accurately reflects the underlying hydrochemical reality.

Diagram 1: HCA Workflow for Hydrochemical Data. This workflow outlines the standard process for applying Hierarchical Cluster Analysis to hydrochemical data, from initial collection to final classification.

Experimental Protocols for HCA in Groundwater Studies

Data Collection and Preprocessing Protocol

The reliability of any dendrogram is contingent on the quality of the input data. Standardized collection and preprocessing protocols are therefore essential.

- Sample Collection: Groundwater samples should be collected in clean, pre-rinsed polyethylene bottles. For cation analysis, samples are typically acidified with dilute nitric acid (HNO₃) to a pH < 2 to preserve metal ions. Samples for anion analysis are generally unacidified. Field measurements of parameters like pH, temperature, and electrical conductivity (EC) should be conducted on-site using calibrated portable meters [11].

- Laboratory Analysis: Major cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) are often determined using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES), while anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) are analyzed by Ion Chromatography (IC). Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) is frequently measured in the field by titration. The analytical precision for each parameter must be documented [11].

- Data Quality Assurance: Use of national reference materials for instrument calibration is critical. An ion balance error calculation should be performed to verify the analytical quality, typically accepting results with an error below ±5% [11] [12].

HCA Execution and Validation Protocol

The core analytical steps transform the prepared data into a validated hydrochemical classification.

- Data Standardization: Due to the different units and variances of hydrochemical parameters, data standardization (e.g., z-score normalization) is often necessary to prevent variables with larger scales from dominating the cluster analysis [11] [13].

- Distance and Linkage: The Euclidean distance is a common choice for calculating the dissimilarity between samples in the c-dimensional space defined by the hydrochemical variables. This distance matrix is then processed by a linkage algorithm. As shown in Table 1, Ward's method is frequently used in hydrochemistry as it tends to create clusters of minimal variance and is effective for the typically smaller sample sizes in these studies [11] [13].

- Cluster Validation: The cluster structure derived from HCA should not be interpreted in isolation. Validation is achieved by:

- Geochemical Plots: Plotting the clustered groups on Piper, Gibbs, or other hydrochemical diagrams to check if the statistical groups correspond to chemically distinct water types [12] [13].

- Spatial Analysis: Mapping the cluster groups to see if they form coherent spatial patterns, which can indicate common hydrogeological controls or contamination sources [12].

- Comparison with Other Multivariate Methods: Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to see if the main principal components differentiate the same clusters identified by HCA, thereby confirming the internal structure of the data [11] [12].

Core Outputs: Interpreting Dendrograms and Cluster Structures

The dendrogram is the primary visual output of HCA, and its correct interpretation is crucial. The branch lengths and fusion points represent the relative similarity between samples and clusters. A key decision is determining where to "cut" the dendrogram to define the final cluster groups, which is often informed by the research context and the magnitude of the fusion coefficients [11] [14].

Interpreting these structures in a hydrochemical context means associating statistical groups with geochemical processes. For example, a study in the Debrecen area of Hungary used HCA to reveal a temporal shift from six clusters in 2019 to five clusters in 2024, indicating a gradual homogenization of groundwater quality over time. This statistical finding was validated by linking it to a hydrochemical shift from Ca-Mg-HCO₃ towards Na-HCO₃ water types, driven by ongoing water-rock interactions [12]. Similarly, another study used HCA to group samples, which were then identified as distinct hydrochemical facies (e.g., Mg-HCO₃ and Mg-SO₄) using Stiff diagrams, effectively linking the statistical cluster to a geological interpretation [13].

Diagram 2: Dendrogram Interpretation Process. This diagram illustrates the logical flow for extracting meaningful hydrochemical insights from a dendrogram, from determining the number of clusters to identifying governing geochemical processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of HCA for groundwater classification relies on a foundation of precise analytical techniques and computational tools. The following table details key solutions and materials used in featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Hydrochemical HCA Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in Hydrochemical HCA |

|---|---|

| Polyethylene Sampling Bottles | Sample container for collecting and transporting groundwater, pre-cleaned with distilled water to avoid contamination [11]. |

| Dilute Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Added to cation samples to acidify and preserve them (pH < 2), preventing precipitation and adsorption of metals to container walls [11]. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) | Analytical instrument for precise determination of major cation (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) and trace metal concentrations [11]. |

| Ion Chromatograph (IC) | Analytical instrument for accurate measurement of major anion concentrations (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) in water samples [11]. |

| Calibration Standard Reference Materials (NRM/GSB) | Certified reference materials used to calibrate ICP-OES, IC, and other instruments, ensuring analytical accuracy and data quality [11]. |

| STATISTICA / R / Python | Statistical software environments used to perform the HCA, generate dendrograms, and execute other multivariate analyses like PCA [11] [14]. |

| Portable Conductivity/pH Meter | Field instrument for in-situ measurement of physical parameters like Electrical Conductivity (EC) and pH, which are critical variables for clustering [11] [13]. |

Integrated Performance and Best Practices

The performance of HCA is rarely judged in isolation but rather by how well its outputs integrate with other lines of evidence to form a coherent hydrogeochemical narrative. A powerful demonstration of this is the synergy between HCA and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). HCA provides a definitive classification of samples into groups, while PCA explains the key variables responsible for that classification. For instance, a study might find that the primary division between two main clusters in a dendrogram corresponds to the spread of samples along a PCI axis, which is heavily weighted on parameters like EC, K⁺, and SO₄²⁻, pointing to a specific geogenic or anthropogenic process [12].

For researchers, the following best practices are recommended:

- For Data with Fewer Samples/Variables: Ward's method is often the most effective, producing well-defined, distinct clusters [11].

- For Large, Complex Datasets: Average linkage methods are generally more robust and suitable [11].

- Always Validate Statistically: Use PCA and geochemical plots to provide a geochemical meaning to the statistical clusters. A cluster is only meaningful if it represents a chemically and hydrologically distinct entity [12] [13].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Newer approaches integrating deep learning with HCA show promise in automatically extracting complex features from multidimensional data, potentially capturing relationships missed by traditional HCA alone [15].

In conclusion, the objective comparison of HCA outputs confirms that Ward's method and Average linkage are among the most reliable for hydrochemical classification tasks. The dendrograms and cluster structures they produce, when validated through a rigorous protocol and integrated with other multivariate and geochemical tools, provide a powerful and objective framework for classifying groundwater quality and unraveling the processes that control it.

This guide provides an objective comparison of core components in hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), specifically focusing on the performance of linkage methods and distance metrics. Framed within the context of validating HCA for groundwater quality classification, we synthesize experimental data from multiple studies to guide researchers in selecting optimal clustering configurations. The analysis demonstrates that the choice of linkage and distance criteria significantly impacts clustering quality, with specific combinations such as Ward linkage with Euclidean distance or average linkage with maximum distance yielding superior results in empirical benchmarks. Supporting data from groundwater case studies illustrate how these methodological choices directly influence the interpretation of water quality clusters and the identification of contamination patterns.

Hierarchical clustering is a fundamental unsupervised machine learning method that builds a hierarchy of clusters, widely used for exploring patterns in complex environmental data [4]. In groundwater quality research, it helps identify spatially similar contamination profiles, classify aquifers based on hydrochemical facies, and inform targeted remediation strategies [16] [17]. The technique operates through two primary approaches: agglomerative (bottom-up), where each data point starts as its own cluster and pairs are merged recursively, and divisive (top-down), where all data points start in one cluster that is recursively split [4]. The agglomerative approach is more commonly implemented due to its computational efficiency for small to medium-sized datasets [4].

The effectiveness of hierarchical clustering in groundwater studies depends critically on three interconnected components: the dissimilarity matrix, which stores pairwise distances between all data points; distance metrics, which quantify the difference between individual observations; and linkage methods, which define how distances between clusters are calculated [18] [4]. inappropriate selection of these components can lead to misleading clustering results, potentially compromising water quality assessments and subsequent management decisions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential elements, supported by experimental data, to inform their application in groundwater quality research and validation.

Core Terminology and Mathematical Foundations

The Dissimilarity Matrix

The dissimilarity matrix is a fundamental prerequisite for hierarchical clustering, serving as the input upon which the algorithm operates. This (n \times n) matrix stores all pairwise distances between (n) data points, providing a comprehensive representation of data similarity [4]. In groundwater quality studies, each data point typically represents a sampling location, with measured parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), fluoride, nitrate, and heavy metal concentrations [16] [17]. The matrix is symmetric (since the distance between point A and point B equals that between B and A) with zeros along the diagonal (each point's distance to itself is zero), requiring storage of (n(n-1)/2) unique pairwise distances [18].

Distance Metrics

Distance metrics quantify the dissimilarity between individual data points. The choice of metric determines which data points are considered similar, fundamentally influencing the resulting cluster structure [18]. Below are commonly used distance metrics in environmental data analysis:

Euclidean Distance: The straight-line distance between points in multivariate space, calculated using the Pythagorean theorem. For n-dimensional space, the distance between points x and y is: (d(x,y) = \sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - y_i)^2}) [19]. It works well when data dimensions have similar scales and clusters are spherical.

Manhattan Distance: The sum of absolute differences along each dimension: (d(x,y) = \sum{i=1}^{n}|xi - y_i|) [19]. Also known as the L1 norm, it is less sensitive to outliers than Euclidean distance.

Maximum Distance: Also called Chebyshev distance or the supremum norm, this takes the maximum absolute difference along any single dimension: (d(x,y) = \maxi(|xi - y_i|)) [19]. It tends to emphasize dominant variables in the dataset.

Correlation Distance: Measures pattern similarity regardless of magnitude, calculated as (1 - r) where (r) is the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient between two points [18]. This is particularly useful for gene expression data but less common in groundwater studies.

For groundwater quality datasets, which often contain parameters with different units and scales (e.g., pH, TDS in ppm, ion concentrations in meq/L), data normalization is essential before applying distance metrics like Euclidean or Manhattan to prevent variables with larger numerical ranges from dominating the distance calculations [18].

Linkage Methods

Linkage criteria determine how the distance between two clusters is calculated from the pairwise distances of their members, significantly influencing the shape and compactness of resulting clusters [4]. The most commonly used linkage methods include:

Single Linkage: Also known as minimum linkage, defines cluster distance as the shortest distance between any two points in the different clusters: (L(R,S) = \min(D(i,j)), i\epsilon R, j\epsilon S) [20]. This approach can create elongated, chain-like clusters but is sensitive to outliers [21].

Complete Linkage: Also called maximum linkage, uses the farthest pair of points between clusters to determine distance: (L(R,S) = \max(D(i,j)), i\epsilon R, j\epsilon S) [20]. It tends to produce compact, spherical clusters and is more robust to outliers than single linkage [21].

Average Linkage: Computes the average of all pairwise distances between points in the two clusters: (L(R,S) = \frac{1}{n{R}\times n{S}}\sum{i=1}^{n{R}}\sum{j=1}^{n{S}} D(i,j), i\in R, j\in S) [20]. This approach offers a balance between single and complete linkage [21].

Ward Linkage: Minimizes the total within-cluster variance by evaluating the increase in the sum of squared errors when clusters are merged [4]. The formula is: (L(R,S) = \frac{nR \cdot nS}{nR + nS} \|\muR - \muS\|^2) where (\mu) represents cluster centroids [4]. Ward's method typically produces compact, well-separated clusters of roughly equal size.

Centroid Linkage: Uses the distance between cluster centroids as the linkage distance: (L(R,S) = D(\bar{R}, \bar{S})) where (\bar{R}) and (\bar{S}) are the mean vectors of clusters R and S respectively [20]. This method can exhibit inversion phenomena where clusters appear to become more similar after merging.

Table 1: Summary of Key Linkage Methods and Their Properties

| Linkage Method | Mathematical Formula | Cluster Shape Tendency | Sensitivity to Outliers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | (\min(D(i,j))) | Elongated, chain-like | High |

| Complete Linkage | (\max(D(i,j))) | Compact, spherical | Low to moderate |

| Average Linkage | (\frac{1}{nR nS}\sum\sum D(i,j)) | Moderately compact | Moderate |

| Ward Linkage | (\frac{nR nS}{nR+nS}|\muR-\muS|^2) | Compact, similar size | Low |

| Centroid Linkage | (D(\bar{R}, \bar{S})) | Varies | Moderate |

Experimental Comparison of Method Performance

Benchmarking Distance-Linkage Combinations

A comprehensive study comparing distance metrics and linkage methods across multiple datasets provides empirical evidence for performance differences [19]. Researchers evaluated three distance metrics (Euclidean, Manhattan, and Maximum) with four linkage methods (Single, Complete, Average, and Ward) using a fitness function combining silhouette width and within-cluster distance. The findings revealed significant performance variations:

Table 2: Performance of Distance-Linkage Combinations Based on Fitness Scores [19]

| Distance Metric | Best-Performing Linkage | Typical Application Context | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Distance | Average (medium datasets), Ward (large datasets) | Gene expression data, large environmental datasets | Produces highest-quality clusters across diverse data types |

| Euclidean Distance | Ward linkage | Groundwater quality classification, general scientific data | Excellent for compact, spherical clusters |

| Manhattan Distance | Complete or Average linkage | Data with outliers, high-dimensional spaces | Robust to outliers and noise |

The maximum distance metric consistently produced the highest-quality clusters across diverse datasets when combined with appropriate linkage methods [19]. For medium-sized datasets, average linkage paired with maximum distance achieved optimal results, while for larger datasets, Ward linkage with maximum distance performed best. These findings challenge the conventional default of Euclidean distance with complete linkage, suggesting that alternative combinations may yield superior clustering quality for specific data characteristics.

Groundwater Quality Case Study

In groundwater quality assessment, clustering methods help identify regions with similar contamination patterns and hydrochemical processes [16]. A study in Northern India analyzed 115 groundwater samples from 23 locations for 12 water quality parameters, including pH, TDS, fluoride, and various ions [16]. The researchers applied multiple machine learning approaches, with clustering serving as a foundational analysis to identify spatial patterns of contamination.

The experimental protocol involved:

- Sample Collection: Groundwater samples were collected from tube wells, submersibles, and hand pumps after stale water evacuation, stored in pre-washed high-thickness polypropylene bottles [16].

- Parameter Analysis: Twelve water quality parameters (pH, TDS, total alkalinity, total hardness, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻) were analyzed using titration, flame photometry, and spectrophotometry [16].

- Data Preprocessing: Parameter normalization to ensure equal weighting in distance calculations.

- Cluster Validation: The resulting clusters were validated against known hydrochemical facies from Piper diagram analysis, with most samples classified into Ca-Mg-Cl dominant groups [16].

This application demonstrates how hierarchical clustering can reveal meaningful patterns in complex groundwater quality data, particularly when appropriate distance and linkage choices are made.

Computational Considerations

The computational complexity of hierarchical clustering represents an important practical consideration, especially for large environmental monitoring datasets. The standard agglomerative clustering algorithm has a time complexity of (O(n^3)) and requires (O(n^2)) memory, where (n) is the number of data points [4]. This quadratic memory requirement can become prohibitive for datasets with thousands of sampling points, though optimized algorithms can achieve (O(n^2)) time complexity [4].

For the linkage methods specifically, the time complexity is generally (O(n^2)) for the initial distance matrix calculation, with the overall clustering process reaching (O(n^3)) due to the hierarchical merging process [21]. Single, complete, and average linkage share similar time complexities, though practical performance may vary based on implementation details [21].

Implementation Workflow for Groundwater Quality Classification

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for implementing hierarchical clustering in groundwater quality studies, incorporating validation steps essential for research credibility:

Research Reagent Solutions for Groundwater Clustering Studies

The following table outlines essential "research reagents" - computational tools and methodological components - required for implementing hierarchical clustering in groundwater quality studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Groundwater Quality Clustering Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Distance Metrics | Quantify dissimilarity between sampling locations based on water quality parameters | Euclidean, Manhattan, Maximum distances [19] |

| Linkage Methods | Determine how distances between clusters are calculated during hierarchical merging | Ward, Complete, Average, Single linkage [4] |

| Validation Metrics | Assess clustering quality and optimal cluster number | Silhouette Width, Within-Cluster Distance, Calinski-Harabasz Index [19] |

| Statistical Software | Implement clustering algorithms and visualization | R (cluster, hclust), Python (scipy.cluster.hierarchy, scikit-learn) |

| Visualization Tools | Represent clustering results for interpretation | Dendrograms, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots, Spatial mapping |

This comparison guide demonstrates that the selection of distance metrics and linkage methods significantly influences hierarchical clustering outcomes in groundwater quality research. Empirical evidence indicates that maximum distance combined with average or Ward linkage often produces superior clustering quality, though Euclidean distance with Ward linkage remains a robust default for many groundwater applications [19].

For researchers validating hierarchical clustering in groundwater quality classification, we recommend:

- Contextual Method Selection: Choose distance and linkage methods based on dataset characteristics and research objectives rather than default settings.

- Comprehensive Validation: Employ multiple validation metrics (silhouette width, within-cluster distance) alongside domain expertise to assess clustering quality.

- Computational Efficiency: Consider dataset size and computational constraints when selecting methods, as hierarchical clustering becomes resource-intensive with large sample numbers.

The integration of appropriate clustering methodologies strengthens groundwater quality assessment frameworks, enabling more accurate identification of contamination patterns and informing targeted remediation strategies. Future research directions should include developing hybrid approaches that combine hierarchical clustering with other machine learning techniques for enhanced pattern recognition in complex hydrochemical datasets.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying HCA for Groundwater Quality Classification

In the realm of environmental science, the validation of hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) for groundwater quality classification represents a significant advancement in water resource management. The accuracy and reliability of such analytical frameworks are profoundly dependent on the preparatory stages of data handling. Data preparation serves as the foundational step that dictates the success of all subsequent analyses, transforming raw, often disparate water quality measurements into a structured dataset capable of revealing meaningful hydrogeochemical patterns [15]. Within a broader thesis on validating HCA for groundwater classification, this process ensures that the identified clusters genuinely reflect underlying environmental processes rather than artifacts of data inconsistencies.

The challenges inherent in groundwater quality data are multifaceted. Datasets typically comprise measurements of various physical, chemical, and biological parameters—such as pH, temperature, specific conductance (EC), and concentrations of major ions like Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻, and NO₃⁻—collected from diverse monitoring wells over extended periods [22] [23]. These parameters are often measured on different scales and units, may contain missing observations due to logistical constraints, and are susceptible to contamination from sampling or analytical errors. Furthermore, the complex interdependencies between these parameters can be obscured without proper preprocessing [15].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various data preparation techniques, with a particular emphasis on scaling and normalization, framing them within the experimental protocols used in groundwater studies. By providing supporting data and detailed methodologies, it aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to build robust, validated HCA models for groundwater quality classification, ultimately supporting sustainable water resource management and protection.

Data Preparation Fundamentals for Hydrochemical Data

The journey from raw field measurements to a clean, analysis-ready dataset involves several critical steps. Each step directly impacts the performance of HCA, which relies on distance calculations between data points to form clusters of similar water samples.

Data Cleaning and Handling Missing Values

Data cleaning begins with the identification and treatment of outliers—data points that deviate significantly from the majority. In groundwater studies, outliers may arise from laboratory errors, transcription mistakes, or genuine but extreme hydrogeochemical conditions. Techniques for handling outliers include:

- Visual Inspection: Using box plots or scatter plots of parameters like TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) or ion concentrations to identify anomalous values.

- Statistical Methods: Employing Z-scores or Interquartile Range (IQR) rules to flag data points that fall beyond a statistically defined range.

- Domain Knowledge Consultation: Collaborating with hydrogeologists to determine if an outlier represents a data error or a true hydrochemical anomaly that should be retained.

The handling of missing values is another pivotal step. Common strategies include:

- Deletion: Removing samples with excessive missing values (e.g., more than 20% of parameters unmeasured). This approach is simple but can lead to loss of valuable information.

- Imputation: Replacing missing values with estimated ones. For groundwater data, this can be effectively done using:

- Mean/Median Imputation: Replacing missing values with the mean or median of the available data for that parameter from the same aquifer or hydrochemical facies.

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) Imputation: Estimating the missing value based on the values from the k most similar water samples, where similarity is defined by the measured parameters [24].

- Regression Imputation: Using relationships between parameters (e.g., the strong correlation often observed between EC and TDS) to predict and fill missing values.

Failure to adequately address missing data can introduce bias and reduce the statistical power of the cluster analysis, potentially leading to the misclassification of water types.

The Critical Role of Scaling and Normalization

Scaling and normalization are preprocessing techniques that adjust the scale or distribution of features. Their importance in HCA for groundwater studies cannot be overstated for several reasons:

- Mitigating Dominant Features: Groundwater parameters are measured on different scales (e.g., pH on a logarithmic scale of 0-14, ion concentrations in mg/L ranging from tens to thousands). Without scaling, parameters with larger numerical ranges, such as Ca²⁺ or HCO₃⁻, can disproportionately influence the distance calculations in HCA, effectively causing the algorithm to ignore more subtle variations in parameters with smaller ranges, like certain heavy metals [25] [5].

- Improving Algorithm Performance: HCA is a distance-based algorithm. When features are on comparable scales, the Euclidean or other distance metrics used to define similarity between samples provide a balanced and meaningful representation of their hydrochemical differences [26].

- Enhancing Interpretability: Clusters derived from scaled data are more likely to represent true hydrochemical affinities rather than being artifacts of measurement units, leading to more accurate interpretations of hydrogeochemical processes, such as ion exchange or rock-water interactions [23].

The choice of scaling technique is not merely a procedural formality but a critical decision that shapes the analytical outcome. For instance, in a study comparing clustering techniques, preprocessing data with UMAP consistently improved clustering quality across all algorithms [27]. The following section provides a detailed comparison of the most common scaling methods used in hydrochemical studies.

Comparative Analysis of Scaling and Normalization Techniques

A wide array of scaling and normalization techniques exists, each with distinct mechanisms and effects on data structure. The performance of these techniques is highly dependent on the characteristics of the dataset and the chosen clustering algorithm [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Feature Scaling Techniques

| Technique | Mathematical Formula | Key Characteristics | Best Suited For Data With | Impact on HCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardization (Z-score) | ( z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} ) | Centers data to mean=0, scales to standard deviation=1. | Gaussian (normal) distribution; presence of outliers. | Creates spherical clusters; sensitive to outliers. |

| Min-Max Scaling | ( X{\text{norm}} = \frac{X - X{\text{min}}}{X{\text{max}} - X{\text{min}}} ) | Scales data to a fixed range, often [0, 1]. | Bounded ranges; no strong outliers; algorithms requiring input range (e.g., NN). | Can compress inliers if outliers are extreme. |

| Robust Scaling | ( X_{\text{robust}} = \frac{X - \text{Median}}{IQR} ) | Uses median and Interquartile Range (IQR). | Significant outliers; non-Gaussian distributions. | Mitigates outlier influence; preserves core data structure. |

| Max Abs Scaling | ( X{\text{scaled}} = \frac{X}{\lvert X{\text{max}} \rvert} ) | Scales each feature by its maximum absolute value. | Data centered around zero; sparse data. | Maintains sparsity and sign of data. |

| Quantile Transformer | Non-linear, based on rank statistics. | Maps data to a uniform or normal distribution. | Non-linear relationships; non-Gaussian distributions. | Can improve separation of complex clusters. |

Experimental Data on Technique Performance

Empirical studies across various domains provide quantitative evidence of how scaling choices impact clustering outcomes. Research evaluating 12 scaling techniques across 14 machine learning algorithms found that while ensemble methods are largely independent of scaling, other models show significant performance variations [25]. Specifically for clustering:

- A comparative analysis of clustering techniques on high-dimensional data demonstrated that preprocessing with UMAP, a manifold-learning technique that often incorporates internal normalization, consistently improved clustering quality across K-means, DBSCAN, and Spectral Clustering algorithms [27].

- The study further revealed that Spectral Clustering, a graph-based algorithm closely related to HCA, demonstrated superior performance in capturing complex, non-linear relationships after appropriate dimensionality reduction and scaling [27].

In the specific context of hydrochemistry, a comparative study of HCA methods found that the success of different linkage criteria (e.g., Ward's, average, complete) is contingent on proper data pretreatment [5]. Ward's minimum-variance method, which is one of the most popular linkage methods for hydrochemical classification, is particularly sensitive to scaling as it aims to minimize the variance within clusters and is inherently based on Euclidean distance [5] [26].

Table 2: Impact of Data Preprocessing on HCA Performance in Hydrochemical Studies

| Study Context | Preprocessing Method | HCA Linkage Method | Key Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayi Tunnel Leakage Water Classification [5] | Standardization & Log-ratio | Ward's Minimum-Variance | Achieved clearest separation of water types and leakage sources. |

| Shallow Aquifer Hydrochemistry [23] | Log-transformation & Euclidean Distance | Ward's Method | Effectively identified hydrochemical facies and evolutionary trends from Kandi to Sirowal formations. |

| Groundwater Contamination Time Series [28] | Not Explicitly Stated (DTW inherently handles shifts) | Not Applicable (Used Dynamic Time Warping) | Successfully clustered multivariate time series, identifying contamination hotspots and background trends. |

Experimental Protocols for Groundwater Data Preparation

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of HCA in groundwater classification, a standardized experimental protocol for data preparation is essential. The following workflow outlines the key stages, from data collection to the final prepared dataset ready for cluster analysis.

Diagram 1: Data Preparation Workflow for HCA

Protocol 1: Data Collection and Initial Validation

Objective: To gather a robust set of groundwater quality parameters and perform initial quality checks. Materials:

- Sampling Bottles: Pre-cleaned high-density PVC bottles for cation and anion analysis [22].

- Field Meters: Calibrated portable meters for in-situ measurement of pH, temperature, EC, and TDS [22] [23].

- Laboratory Equipment: Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) for cations, Ion Chromatograph (IC) for anions, titrimetric setup for hardness and alkalinity [5].

Methodology:

- Collect water samples from monitoring wells or borewells, ensuring geographic and hydrogeological representation.

- For cation analysis, acidify samples with dilute HNO₃ to pH < 2 to preserve metal ions.

- Measure field parameters immediately at the sampling site.

- Analyze major ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻, NO₃⁻) in the laboratory using standard methods [23].

- Perform an ion balance check to validate the analytical data. The error should generally be within ±5% [23]. Reject samples with excessive error as outliers.

Protocol 2: Data Cleaning and Imputation

Objective: To create a consistent and complete dataset by addressing data quality issues. Materials: Statistical software (e.g., R, Python, SPSS).

Methodology:

- Visual Data Inspection: Create boxplots for each parameter to visually identify potential outliers.

- Statistical Outlier Detection: Calculate Z-scores. Consider capping or winsorizing values with a Z-score beyond ±3, but only after consulting domain expertise to rule out genuine hydrochemical anomalies.

- Handle Missing Values:

- For datasets with a small percentage (<5%) of randomly missing values, use mean/median imputation.

- For larger or non-random gaps, employ model-based imputation like KNN. Using the

KNNImputerfrom Python'sscikit-learnlibrary withk=5is a common and effective approach, as it leverages the multivariate structure of the data.

Protocol 3: Application of Scaling Techniques

Objective: To normalize the parameter scales for unbiased distance calculation in HCA.

Materials: Statistical software with preprocessing libraries (e.g., scikit-learn in Python).

Methodology:

- Assess Data Distribution: Plot histograms or Q-Q plots for key parameters to check for normality and the presence of outliers.

- Select and Apply Scaling:

- If the data is roughly normally distributed and outliers are minimal, apply Standardization (Z-score).

- If the data contains significant outliers, apply Robust Scaling.

- For a comparative study, create multiple datasets, each transformed with a different scaling method (e.g., Z-score, Min-Max, Robust).

- Dimensionality Reduction (Optional but Recommended): For high-dimensional data (many parameters), apply dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or UMAP on the scaled data to reduce noise and multicollinearity before HCA [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Groundwater Quality Analysis

| Item | Function in Data Preparation & Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Density PVC Sampling Bottles | Inert containers for collecting water samples, preventing contamination and adsorption of ions, which is crucial for data accuracy. |

| Portable Multi-Parameter Meter | For in-situ measurement of pH, EC, TDS, and temperature. Provides immediate, critical data points for the initial dataset. |

| Dilute Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Used to acidify samples for cation analysis, preventing precipitation and preserving the true concentration of metals for reliable measurements. |

| EDTA Titrant | Used in titrimetric analysis to determine total hardness, and calcium and magnesium concentrations—fundamental hydrochemical parameters. |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) System | Precisely separates and quantifies anion concentrations (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, F⁻), forming a major part of the ionic dataset for HCA. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python with scikit-learn) | The computational engine for performing data cleaning, scaling, normalization, and executing the hierarchical cluster analysis itself. |

The journey toward a validated and scientifically robust hierarchical cluster analysis for groundwater quality classification is paved with meticulous data preparation. This guide has demonstrated that cleaning, handling missing values, and the critical step of scaling are not mere preludes to analysis but are integral to the analytical process itself. The choice of scaling technique—be it Standardization for Gaussian-like data, Robust Scaling for outlier-prone datasets, or more advanced non-linear transformers for complex distributions—directly and measurably influences the cluster structure output by HCA.

The experimental protocols and comparative data presented provide a reproducible framework for researchers. By adopting these standardized procedures, scientists can ensure that the resulting clusters, whether identifying hydrochemical facies [23], pinpointing contamination sources [5] [28], or classifying water types [15], are a reliable reflection of true subsurface processes. In doing so, they strengthen the foundation upon which critical decisions about water resource management and environmental protection are made.

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) is a fundamental technique in unsupervised machine learning and exploratory data analysis, with applications spanning numerous scientific disciplines [29]. For researchers in fields like groundwater quality classification, the choice of clustering methodology is not merely a procedural step but a critical decision that directly influences the interpretation of complex environmental systems. The performance of HCA is profoundly affected by two core components: the linkage method, which determines how the distance between clusters is calculated, and the distance metric, which defines the pairwise dissimilarity between individual data points [21] [30]. Within the specific context of validating groundwater quality classifications, studies have demonstrated that linkage rules often have a higher impact on the final clusters than the choice of distance metric itself [31]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary linkage methods—Ward's, Average, and Complete—to equip researchers with the evidence needed to make an informed algorithmic selection.

Theoretical Foundations of Linkage Methods

How Hierarchical Clustering Works

Hierarchical clustering constructs a tree-like structure of clusters (a dendrogram) by iteratively merging or splitting groups based on their similarity. The process can be either agglomerative (bottom-up, starting with single points) or divisive (top-down, starting with one cluster). Agglomerative clustering is more common and involves the following steps: First, the algorithm begins by calculating a distance matrix containing all pairwise dissimilarities between data points. Second, it identifies the two closest points and merges them into a new cluster. Finally, it updates the distance matrix to reflect the distance between the new cluster and all other clusters, repeating the merge process until only a single cluster remains [30]. The central challenge in this process lies in step three: how to define the distance between two clusters that may contain multiple data points. This is precisely what the linkage method determines.

The Role of Distance Metrics

Before a linkage method can be applied, a distance metric must be selected to quantify the dissimilarity between two individual data points. Common metrics include: