A Comprehensive Guide to MRM Pair Validation: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Application

This article provides a complete framework for the development, validation, and application of Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) assays for the confirmation and quantification of compounds in biomedical research and drug...

A Comprehensive Guide to MRM Pair Validation: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for the development, validation, and application of Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) assays for the confirmation and quantification of compounds in biomedical research and drug development. It covers the core principles of MRM on triple quadrupole mass spectrometers, method establishment and optimization, troubleshooting for complex matrices, and rigorous validation following international guidelines. Designed for researchers and scientists, this guide bridges the gap between foundational theory and practical implementation, emphasizing the critical role of robust MRM validation in generating reliable data for clinical diagnostics, therapeutic drug monitoring, and biomarker discovery.

Understanding MRM Fundamentals: Principles and Instrumentation for Targeted Quantification

What is MRM? Defining Multiple Reaction Monitoring in Mass Spectrometry

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), also known as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), is a targeted mass spectrometry technique renowned for its high specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy in quantifying specific molecules within complex mixtures [1] [2] [3]. It is particularly indispensable in fields such as proteomics, metabolomics, and preclinical drug studies, where precise measurement of target analytes is crucial for research and development [4] [5].

Core Principles of MRM

The MRM technique is performed on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Its fundamental principle involves two stages of mass selection to monitor a specific reaction transition [1] [2].

- Precursor Ion Selection (Q1): The first quadrupole (Q1) isolates ions based on a specific mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) corresponding to the target analyte.

- Fragmentation (Q2): The selected precursor ions are then directed into a collision cell (q2), where they are fragmented through processes like collision-induced dissociation (CID).

- Product Ion Selection (Q3): The third quadrupole (Q3) then selects a specific, characteristic fragment ion (product ion) derived from the precursor. This specific pair of m/z values—precursor ion and product ion—is known as a "transition." The high selectivity achieved by monitoring a specific transition allows MRM to distinguish target analytes from background noise and co-eluting compounds in complex samples like plasma, urine, or tissue digests with exceptional reliability [2] [6].

Figure 1: Instrumental principle of MRM on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

MRM Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Developing a robust MRM assay is a multi-stage process that requires careful optimization to achieve maximum sensitivity and specificity. The following workflow outlines the key steps for developing an MRM method for protein quantification, a common application in proteomics [7] [6].

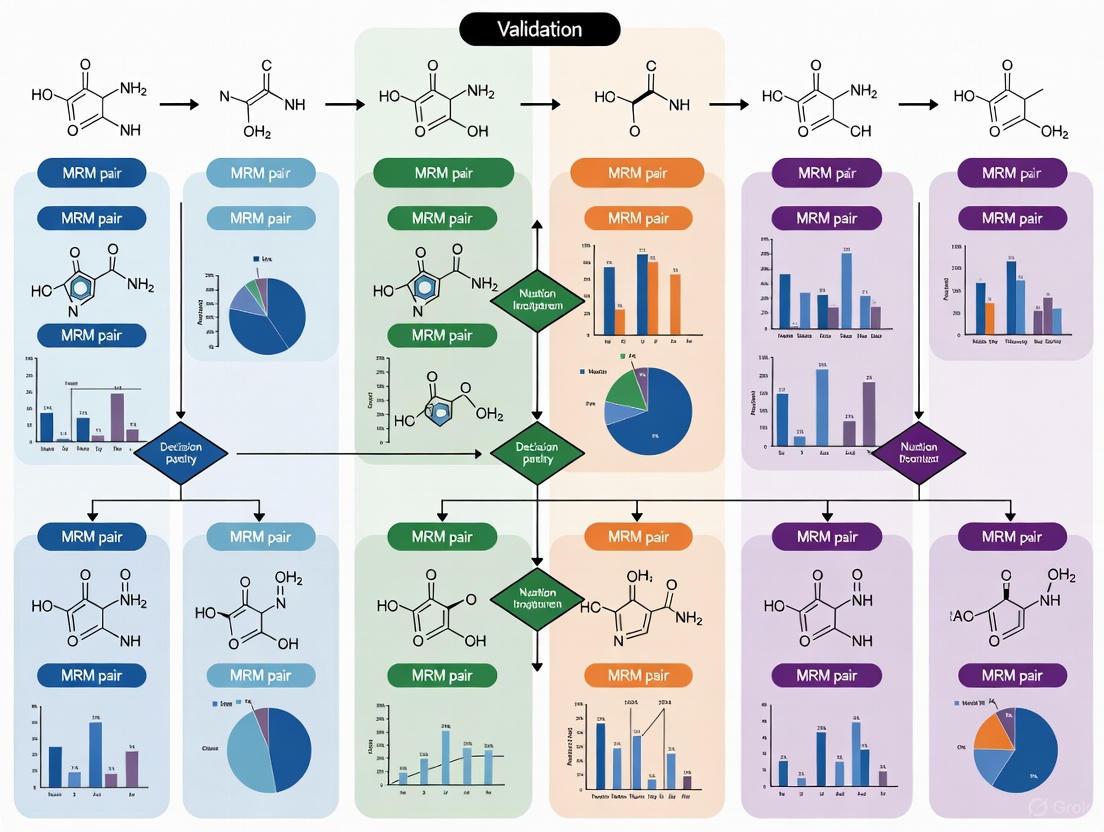

Figure 2: Key stages of MRM assay development.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

1. Selection of Signature Peptides For protein quantification, proteotypic peptides—peptides unique to the target protein—are selected as surrogates. Ideal peptides are typically 5-25 amino acids long, have fully enzymatic (e.g., tryptic) cleavage ends, and avoid amino acids prone to chemical modifications like methionine (oxidation) or asparagine (deamidation) [6].

2. Transition Selection and Optimization A key strength of MRM is the ability to monitor multiple transitions for one or more precursor ions [1]. For each peptide, several specific fragment ions (transitions) are selected, typically focusing on abundant y-ions with higher m/z values [6]. The instrument parameters for each transition, especially collision energy (CE), must be empirically optimized to generate the maximal product ion signal.

Research demonstrates that using generalized equations for CE may not yield optimal signal for all peptides. One proven protocol involves rapidly testing a range of CE values (e.g., ±6 V from the calculated value) in a single run by subtly adjusting the precursor and product m/z values to code for different energies. This workflow allows for the direct determination of the optimal CE for each transition, significantly enhancing sensitivity [7].

3. Method Validation The final developed MRM assay must be validated. This involves confirming peptide identity, for example, by acquiring a full MS/MS spectrum, and ensuring that the transition intensity ratios are consistent with standards. The final assay coordinates—including peptide, fragments, m/z ratios, optimized collision energies, and chromatographic retention time—are established for reproducible quantitative analysis [6].

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Data

MRM's primary advantage lies in its quantitative performance. When combined with stable isotope-labeled standard (SIS) peptides, it enables highly precise and accurate absolute quantification.

Table 1: Performance data of an MRM assay for multiplexed absolute quantitation of 45 proteins in human plasma.

| Performance Metric | Result | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity | Excellent linear response (r > 0.99) for 43 of 45 proteins [8]. | Simple tryptic digest of human plasma without depletion [8]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Attomole level LOQ for 27 of 45 proteins [8]. | LOQ defined as the lowest point in the calibration curve with a CV <20% [8]. |

| Precision | Analytical precision (CV <10%) for 44 of 45 assays [8]. | Inter-day CV <20% for 42 of 45 assays across different batches [8]. |

| Sensitivity in Yeast | ~50 copies/cell in whole cell extracts without fractionation [6]. | Demonstrated in a full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae [6]. |

A Comparative Look at MRM and Alternative Mass Spectrometry Techniques

MRM occupies a specific niche as a targeted quantification technique, contrasting with untargeted discovery methods.

Table 2: Comparison of MRM with other common mass spectrometry approaches.

| Technique | Principle | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) | Targeted detection of predefined precursor-product ion transitions [2]. | Absolute quantification of specific targets in complex mixtures [8] [4]. | High sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy; broad dynamic range; high throughput for targeted analyses [5]. | Requires prior knowledge of analyte; long method development time; dependent on standards [5]. |

| Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) | Targeted high-resolution MS/MS where all product ions for a precursor are recorded in parallel [1]. | Targeted quantification with high resolution and mass accuracy. | Simplified method development; post-acquisition transition selection; increased specificity. | Typically requires high-resolution instruments; data file sizes can be large. |

| Untargeted Discovery (Full Scan MS/MS) | Data-dependent acquisition of MS and MS/MS spectra without predefined targets. | Global protein or metabolite identification and relative quantification. | Ability to discover novel analytes; no prior knowledge required. | Lower dynamic range and sensitivity; less precise for quantification; complex data analysis [8]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful MRM experimentation relies on a set of key research reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential research reagent solutions for MRM experiments.

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards (SIS) | Internal standards for absolute quantification; correct for sample loss and ionization variability [8]. | Synthetic peptides with [13C6]Arg or [13C6]Lys for protein quantitation [8]. |

| Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer | The core instrument platform capable of the two stages of mass filtering required for MRM [2] [6]. | Used for all targeted MRM quantitation workflows [4]. |

| Tryptic Digest Reagents | Enzymes and buffers to cleave proteins into predictable peptides for bottom-up proteomics analysis. | Sequencing-grade trypsin used to digest a standard protein mixture prior to MRM analysis [7]. |

| Chromatography Columns | For reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) separation of peptides or small molecules prior to MS analysis. | Used to separate analytes to reduce matrix effects and isocratically separate venlafaxine and its metabolite [4]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits | For sample clean-up and concentration of target analytes from complex biological matrices. | Used to purify plasma samples before LC-MRM/MS analysis to remove interfering salts and lipids [4]. |

Advantages and Challenges in Practice

MRM technology offers a powerful set of advantages but also presents distinct challenges that researchers must navigate.

- High Sensitivity and Selectivity: MRM can detect target molecules at very low concentrations (attomole levels) in complex samples like plasma [8] [5]. The two-stage mass filtering effectively eliminates background noise and interference signals.

- Accurate Quantification: The use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards allows for highly precise and accurate absolute quantification, making it suitable for biomarker validation and drug monitoring [8] [5].

- High Throughput: MRM can simultaneously monitor hundreds of analytes in a single run, enabling large-scale screening and comparison of clinical samples [8] [5].

Despite its strengths, MRM has limitations. The method development process can be time-consuming and complex, requiring optimization of parameters for each transition [7] [5]. The technique is also dependent on the availability of high-purity synthetic standards, which can be costly [5]. Furthermore, the required mass spectrometry instrumentation and its maintenance involve significant expense [5].

In conclusion, Multiple Reaction Monitoring stands as a cornerstone technique for targeted quantification in mass spectrometry. Its rigorous validation requirements, high specificity, and proven quantitative performance make it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in compound confirmation and biomarker verification.

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) is a highly specific and sensitive tandem mass spectrometry technique central to targeted quantitative analyses in fields such as proteomics, metabolomics, and clinical diagnostics [2] [1]. Its power lies in the unique combination of precursor ion selection, controlled fragmentation, and product ion monitoring to minimize background interference and accurately quantify target analytes within complex mixtures [9] [10]. This guide details the core principles and experimental protocols for validating MRM transitions, providing a direct comparison with alternative mass spectrometry approaches to inform method development.

Core Instrumental Principles of MRM

The MRM process is executed on a tandem mass spectrometer, most commonly a triple quadrupole system, where each quadrupole performs a distinct function [2] [9].

- Quadrupole 1 (Q1): Precursor Ion Selection: The first mass analyzer (Q1) filters ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), allowing only the precursor ion of a specific target analyte to pass through. This initial selection provides the first level of specificity by excluding the vast majority of matrix-derived ions [9] [1].

- Collision Cell (q2): Fragmentation: The selected precursor ions are then accelerated into a collision cell (q2), which is filled with an inert gas such as nitrogen or argon. Collisions between the precursor ions and gas molecules cause Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID), fragmenting the precursor ions into product ions [9]. The degree of fragmentation can be controlled by the applied collision energy [9].

- Quadrupole 3 (Q3): Product Ion Monitoring: The second mass analyzer (Q3) is set to filter a specific, characteristic product ion resulting from the fragmentation of the precursor ion. Monitoring this specific precursor-product ion pair, known as a "transition," provides a second layer of specificity, making MRM exceptionally robust against chemical noise [9] [1].

The combination of these steps results in a highly selective technique where the signal is generated only when the instrument detects the specific ion pair, enabling reliable quantification even for low-abundance analytes in complex samples like plasma, urine, or cellular extracts [2] [11] [10].

Diagram 1: The MRM process on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

Establishing and Validating MRM Transitions: Experimental Workflows

Developing a robust MRM assay requires a systematic approach to select and validate the optimal precursor ion and product ion pairs.

Peptide and Transition Selection for Proteomics

In quantitative proteomics, proteins are digested into peptides, which act as surrogates for quantification [11]. The process begins with selecting proteotypic peptides—peptides that uniquely represent the target protein and are consistently detected by mass spectrometry [10]. For each candidate peptide, a product ion scan is performed, where Q1 is fixed on the peptide's m/z, and Q3 scans across a range to capture all resulting fragment ions [9]. The top two or three most intense and unique product ions are typically chosen for the final MRM assay [11].

Full Experimental Protocol for MRM Assay Validation

The following protocol, adapted from a study on urinary kidney injury biomarkers, outlines the key steps for developing and validating a multiplex LC-MRM-MS assay [11]:

- Step 1: Peptide Selection: Digest target proteins in silico using tools like ExPASy PeptideMass. Select signature peptides based on uniqueness, detectability, and lack of susceptible modifications. Synthesize stable-isotope-labeled (SIL) versions of these peptides to serve as internal standards [11].

- Step 2: Sample Preparation (Immunocapture): To quantify low-abundance proteins from complex matrices, use biotinylated antibodies immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to capture target proteins from the sample. Optimize antibody amount, incubation time, and temperature [11].

- Step 3: Digestion and Clean-up: Denature and reduce captured proteins, then digest them with trypsin. The SIL internal standards are added at this stage to correct for variability in digestion and ionization [11].

- Step 4: LC-MRM-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Perform peptide separation on a reversed-phase C18 column using a water/organic solvent gradient [11].

- Mass Spectrometry: Monitor at least two transitions per peptide (three transitions per peptide is common) for analytical selectivity. The relative response (peak area ratio of analyte to internal standard) is used for quantification via an external calibration curve [11].

- Step 5: Validation against Guidelines: Validate the method against regulatory agency criteria, which typically include calibration curve linearity, specificity, sensitivity (LLOQ), carryover, precision, accuracy, matrix effects, recovery, dilution integrity, and stability [12] [13].

Diagram 2: Workflow for MRM transition development.

Performance Comparison of MRM with Alternative Mass Spectrometry Techniques

The selectivity of MRM comes from monitoring specific transitions, which differentiates it from other scanning modes available on tandem mass spectrometers [9]. The table below compares these key scanning modes.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Scanning Modes in Tandem Mass Spectrometry [9]

| Scan Mode | Q1 Operation | Q3 Operation | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Ion Scan | Fixed on one m/z | Scans a mass range | Identifying fragments of a known ion | Generates full fragment spectrum for identification |

| Precursor Ion Scan | Scans a mass range | Fixed on one m/z | Finding all precursors that make a common fragment | Useful for screening compounds with a common group |

| Neutral Loss Scan | Scans a mass range | Scans synchronously with a fixed offset | Finding all precursors that lose a common neutral group | Identifies compounds with a specific functional group |

| Selected/Multiple Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) | Fixed on one m/z | Fixed on one m/z | Targeted quantification | Highest sensitivity and specificity for target analytes |

MRM provides superior quantitative performance for targeted analysis compared to other MS techniques. A study comparing GC-MS, GC-MRM-MS, and comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC) for analyzing plant biomarkers in complex oil and rock extracts found that while GC×GC offered superior separation of co-eluting compounds, the MRM technique provided excellent sensitivity and selectivity for targeted quantification [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MRM Assays

Successful development and validation of an MRM assay rely on a suite of specific reagents and software tools.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for MRM Assay Development

| Item | Function in MRM Workflow | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer | Instrument platform for performing MRM experiments | Agilent Triple Quadrupole MS [11] |

| Stable Isotope Labeled (SIL) Peptides | Internal standards for precise quantification; correct for sample prep and ionization variability | Synthetic [13C6, 15N2]-Lysine or [13C6, 15N4]-Arginine peptides [11] |

| Immunocapture Reagents | Enrich low-abundance target proteins from complex matrices prior to digestion and analysis | Biotinylated antibodies on streptavidin magnetic beads [11] |

| Skyline Software | Open-source tool for designing MRM assays, analyzing data, and quantifying results | Skyline output files used for validation portal [12] |

| Method Validation Portal (M-MVP) | Web-based tool for automated analytical validation of MRM assays against FDA/EMA guidelines | https://pnbvalid.snu.ac.kr [12] |

MRM mass spectrometry stands as a powerful technique for targeted quantification due to its foundational principles of selective precursor ion filtering, controlled fragmentation, and specific product ion monitoring. Its robustness is demonstrated by its widespread application in demanding clinical and research settings, from quantifying urinary kidney injury biomarkers [11] to determining absolute protein copy numbers in single cells [1]. While full-scan and data-dependent acquisition methods are superior for untargeted discovery, the unmatched sensitivity, specificity, and precision of a well-validated MRM assay make it the gold standard for targeted quantification where the highest data quality is required.

The triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (TQMS or QqQ) represents one of the most significant analytical instruments for targeted quantitative analysis across biomedical, pharmaceutical, and clinical research. First developed in the late 1970s by Christie G. Enke and Richard A. Yost, this tandem mass spectrometry configuration has revolutionized how scientists detect and quantify specific compounds in complex mixtures [15]. The fundamental architecture of the TQMS consists of three sequential quadrupoles: the first (Q1) and third (Q3) function as mass filters, while the second (q2) operates as a radio frequency (RF)–only collision cell [15]. This configuration enables exceptional specificity and sensitivity by performing two stages of mass selection separated by a fragmentation event, effectively isolating the analyte of interest from complex matrix interferences.

The relevance of the TQMS has grown substantially in biomedical research and clinical applications, with the number of biomedical studies utilizing QqQ increasing 2–3 times this decade [16]. Its dominance is particularly pronounced in targeted quantitative analyses, where its robust operation, relatively low cost, and variety of operation modes provide superior specificity and sensitivity compared to alternative platforms [16]. Within the context of Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) assay validation—a cornerstone technique for compound confirmation—the TQMS serves as the instrumental cornerstone, providing the rigorous analytical performance required for clinical applications, diagnostic testing, and pharmaceutical development [12] [17].

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Core Components and Operation

The triple quadrupole mass spectrometer operates on the principle of tandem-in-space mass analysis, where ionization, primary mass selection, collision-induced dissociation (CID), mass analysis of fragments, and detection occur in separate physical segments of the instrument [15]. The three quadrupole components each serve distinct functions:

- Q1 (First Quadrupole): This initial mass filter selects specific precursor ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) by applying combined RF and DC voltages. Only ions with stable trajectories pass through to the next stage, while all others are filtered out [18].

- q2 (Collision Cell): Operating with RF voltage only, this non-mass-resolving quadrupole contains inert gas molecules (such as argon or nitrogen) where collision-induced dissociation occurs. The selected precursor ions from Q1 collide with the gas molecules, fragmenting into product ions through predictable cleavage pathways [15] [18].

- Q3 (Third Quadrupole): This final mass analyzer filters the resulting product ions based on their m/z, allowing only specific fragments to reach the detector. This second stage of mass filtration provides an additional dimension of selectivity [15].

This sequential filtering process—precursor ion selection, fragmentation, and product ion selection—enables the TQMS to achieve exceptional specificity by monitoring specific "mass transitions" that serve as molecular fingerprints for target compounds [18].

Instrumental Configuration and Scan Modes

The TQMS offers several operational modes, each designed to address specific analytical questions. These scan modes leverage the instrument's tandem configuration to provide different dimensions of information:

Product Ion Scan: In this mode, Q1 is fixed to select a specific precursor ion, which is fragmented in q2, and Q3 scans across a range of m/z values to record all resulting fragments. This mode is essential for structural elucidation and for identifying characteristic fragments that can be used for quantification [15].

Precursor Ion Scan: Q3 is fixed to monitor a specific product ion, while Q1 scans through a range of precursor masses. This mode identifies all precursors that generate a common fragment, making it valuable for detecting compounds sharing specific functional groups or structural motifs [15].

Neutral Loss Scan: Both Q1 and Q3 scan simultaneously with a constant mass offset, detecting ions that lose a specific neutral fragment during CID. This approach is particularly useful for identifying closely related compounds that undergo common fragmentation pathways [15].

Selected/Multiple Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM): Both Q1 and Q3 are fixed at specific m/z values to monitor a predefined precursor-product ion transition. MRM extends this concept to monitor multiple transitions simultaneously. This mode provides the highest sensitivity and specificity for quantitative analysis and is the cornerstone of targeted quantification workflows [15] [18].

TQMS vs. Alternative Mass Spectrometry Platforms

Comparative Performance Characteristics

When selecting a mass spectrometry platform for targeted quantification, researchers must consider several performance characteristics, including sensitivity, resolution, throughput, and operational requirements. The following table compares triple quadrupole systems with other common mass spectrometry platforms:

| Instrument | Mass Analyzer Type | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSQ Series (Triple Quad) | Triple Quadrupole | MRM/SRM, H-SRM, fast polarity switching | High sensitivity and selectivity for quantification; robust; cost-effective | Lower resolution; less suited for unknown identification | Targeted quantification, clinical assays, environmental monitoring [19] |

| Q-TOF Systems | Quadrupole + Time-of-Flight | High mass accuracy, Auto MS/MS, full-spectrum acquisition | Good resolution; accurate mass; fast MS/MS | Higher cost; lower throughput for targeted quant vs. TQMS | Small molecule ID, metabolomics, fast screening [19] |

| Orbitrap Platforms | Quadrupole + Orbitrap | Ultrahigh resolution, HCD fragmentation, PRM | Excellent resolution; flexible scan modes; high mass accuracy | Complex operation; high cost; moderate throughput | Advanced proteomics, PTM analysis, untargeted workflows [19] |

| Q Exactive Plus | Quadrupole + Orbitrap | Higher resolution (to 280,000), PRM, DIA | Enhanced quantification; better dynamic range | No MSn capability; mid-range speed | Quantitative proteomics, DIA workflows [19] |

MRM vs. PRM: A Technical Comparison for Targeted Quantification

For researchers focused on MRM validation, understanding the distinction between MRM on TQMS and Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) on high-resolution instruments is crucial:

| Feature | MRM on TQMS | PRM on High-Resolution Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | Triple Quadrupole | Orbitrap, Q-TOF |

| Resolution | Unit resolution | High (HRAM) |

| Fragment Ion Monitoring | Predefined transitions | All fragments (full MS/MS spectrum) |

| Selectivity | Moderate | High (less interference) |

| Sensitivity | Very high | High, depending on resolution |

| Throughput | High | Moderate |

| Method Development | Requires transition tuning | Quick, minimal optimization |

| Data Reusability | No | Yes (retrospective) |

| Best Applications | High-throughput screening, routine quantification | Low-abundance targets, PTMs, validation [20] |

Key Decision Factors: Choose MRM on TQMS when conducting high-throughput, routine quantification where speed, sensitivity, and reproducibility are critical, particularly with well-characterized targets and validated panels. Choose PRM when working with complex matrices where interference is a concern, when analyzing low-abundance or post-translationally modified targets, or when retrospective data flexibility is needed [20].

TQMS Performance and Application-Specific Considerations

Performance Metrics Across TQMS Systems

Different TQMS systems offer varying performance characteristics optimized for specific application requirements. The following table compares representative Thermo Scientific TSQ systems across key performance parameters:

| Performance Parameter | Fortis | Endura | Quantis | Altis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ |

| Resolution | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Scan Speed | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| High Resolution SRM | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Segmented Quadrupoles | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Increased Dynodes in Detector | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Polarity Switching | + | + | + | + |

| Applications | Fortis | Endura | Quantis | Altis |

| Targeted Quantitation in Proteomics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Peptide/Protein Quantitation (Biopharma) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Small Molecule Quantitation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Environmental, Food Safety, Forensics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Trace Impurity Analysis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Omics (Metabolomics, Lipidomics) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes [21] |

Application-Specific Workflows

Clinical Biomarker Validation: In clinical proteomics, MRM assays on TQMS platforms are frequently combined with stable isotope-labeled standard (SIS) peptides for absolute protein quantification. These assays enable highly specific measurement of candidate biomarkers in complex biological samples such as plasma, urine, and tissue lysates, bypassing the need for antibodies and their associated specificity challenges [17].

Endocrine Testing: TQMS has revolutionized steroid hormone analysis, enabling simultaneous measurement of multiple steroids with high specificity. This capability allows for comprehensive steroid profiling for complex evaluation of steroidogenesis in the organism, a significant advantage over traditional immunoassays which often suffer from cross-reactivity issues [16]. The United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UK NEQAS) has reported a significant increase in participants using LC-MS/MS for steroid hormone analysis, rising from 3% to 18% between 2011 and 2019 [16].

Newborn Screening: TQMS serves as the primary instrumental platform for expanded newborn screening programs, enabling early detection of congenital metabolic disorders. Research indicates that at least 84% of studies in newborn screening utilized mass spectrometry, with 823 out of 924 papers explicitly mentioning tandem mass spectrometry or triple quadrupole [16].

Pharmaceutical Impurity Analysis: In biotherapeutic development, TQMS-based workflows enable characterization and quantification of process-related and product-related impurities at extremely low concentrations. The high specificity of MRM assays allows for selective quantification of compounds within complex mixtures, essential for ensuring product quality and patient safety [22].

MRM Assay Validation: Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comprehensive MRM Validation Framework

The validation of MRM assays for clinical applications requires rigorous assessment across multiple analytical performance parameters. Regulatory agencies including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) have established guidelines encompassing 11 key validation criteria [12]:

Calibration Curve: Must demonstrate linearity across the quantitative range of the assay. The relationship between analyte concentration and instrument response should be well-characterized with appropriate regression models [12].

Specificity: The method must distinguish the target analyte and internal standards from endogenous components in the matrix with confidence. This is typically assessed by analyzing blank matrix samples to verify the absence of interfering signals at the retention times of interest [12].

Sensitivity: Defined by the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), which is the lowest concentration on the calibration curve that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy (typically ±20% for small molecules) [12].

Precision and Accuracy: Precision assesses the closeness of repeated individual measurements, while accuracy determines the closeness of observed values to nominal concentrations. These parameters are evaluated across multiple runs (inter-day) and within a single run (intra-day) at multiple concentration levels [12].

Matrix Effects: Critical in LC-MS/MS, ion suppression or enhancement can significantly impact results. Matrix effects are typically evaluated by comparing analyte response in neat solution versus spiked matrix, with calculation of matrix factors [12].

Stability: Must demonstrate analyte stability during handling and storage conditions, including benchtop, freeze-thaw, and long-term storage stability [12].

Transition Optimization and Selection

The performance of an MRM-based method depends strongly on selecting optimal product ions and collision energies. This process requires striking a balance between signal intensity (optimized by choosing the most abundant product ion) and specificity (achieved by selecting unique product ions) [18]. Method development should generally avoid product ions formed by common neutral losses (e.g., H₂O or NH₃), as these occur across many parent ion structures and reduce specificity [18].

For example, when analyzing glucose-6-phosphate, the fragment ion at m/z 199 is specific, enabling use of the transition 259 → 199 to differentiate it from the isomer glucose-1-phosphate. In contrast, glucose-1-phosphate lacks specific product ions, requiring either chromatographic separation or mathematical correction based on signals from glucose-6-phosphate [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful MRM assay development and validation requires specific reagents and materials to ensure analytical robustness:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards (SIS) | Internal standards for absolute quantification | Correct for matrix effects and variability; should be added early in sample processing [17] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance | Should include blank matrix, low, medium, and high QCs; used to assess precision and accuracy [12] |

| Chromatography Columns | Analyte separation | Various chemistries (C18, HILIC, etc.) selected based on analyte properties; maintained at consistent temperature |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Enhance ionization and separation | High-purity acids (formic, acetic), buffers (ammonium acetate/formate); prepared daily for optimal performance |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Plates | Sample cleanup and concentration | Remove interfering matrix components; improve sensitivity and assay robustness |

| Calibrator Materials | Establish quantitative range | Prepared in appropriate matrix; cover expected physiological or experimental concentration range |

| Enzymatic Digestion Reagents | Protein processing (for proteomics) | High-purity trypsin/Lys-C; reduction and alkylation reagents; controlled digestion time/temperature |

The triple quadrupole mass spectrometer remains an indispensable platform for targeted quantitative analysis, particularly in applications requiring robust, sensitive, and specific quantification of predefined analytes in complex matrices. Its fundamental architecture—two mass filters separated by a collision cell—enables the MRM detection mode that has become the gold standard in clinical assay development, pharmaceutical analysis, and biomarker validation.

While high-resolution alternatives like PRM on Orbitrap or Q-TOF instruments offer advantages for certain applications, particularly those requiring retrospective data analysis or dealing with extensive sample complexity, the TQMS maintains distinct advantages in throughput, sensitivity, and operational cost for routine quantification. The rigorous validation frameworks established by regulatory agencies provide a roadmap for developing robust MRM assays that generate clinically and scientifically defensible data.

As mass spectrometry technology continues to evolve, the role of the triple quadrupole remains secure in the analytical landscape, particularly for applications where quantitative precision, high throughput, and operational robustness are paramount. Understanding its operational principles, performance characteristics, and appropriate application domains enables researchers to leverage this powerful technology effectively within their targeted quantification workflows.

In the field of mass spectrometry-based analysis, the choice of data acquisition method profoundly impacts the selectivity, sensitivity, and overall success of quantitative experiments. This comparison guide examines three fundamental approaches: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), and Full-Scan MS. For researchers validating MRM pairs for compound confirmation—particularly in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring—understanding the distinct capabilities and limitations of each technique is essential. This article provides a structured comparison based on current experimental data to inform analytical method selection within the context of compound confirmation research.

Core Principles and Definitions

The foundational difference between these techniques lies in their operation within the mass spectrometer. The following table summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of MRM, SRM, and Full-Scan MS

| Technique | Full Name | Primary Use | Mass Analysis Stages | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRM | Multiple Reaction Monitoring | Targeted Quantification | Two (MS1 & MS2) | Monitors multiple precursor-to-product ion transitions simultaneously [1] [2]. |

| SRM | Selected Reaction Monitoring | Targeted Quantification | Two (MS1 & MS2) | Monitors a single, specific precursor-to-product ion transition [1]. |

| Full-Scan MS | Full Scan Mass Spectrometry | Untargeted Screening | One (MS1) | Scans a broad range of m/z values to record all ions present in a sample [23]. |

SRM/MRM are targeted techniques performed on tandem mass spectrometers (e.g., triple quadrupoles). The first mass analyzer (Q1) selects a specific precursor ion, which is then fragmented in a collision cell (q2). A resulting specific product ion is selected in the second mass analyzer (Q3) for detection. While the terms are often used interchangeably, SRM typically refers to monitoring a single transition, whereas MRM monitors multiple transitions for one or more analytes in a single analysis [1] [2]. This two-stage mass selection provides high specificity by filtering out chemical noise from co-eluting compounds.

Full-Scan MS, in contrast, is an untargeted approach. It uses a single mass analysis stage to record all ions within a specified m/z range, generating a complete mass spectrum at each point in time [23]. This makes it ideal for discovery and screening but typically offers lower sensitivity for quantification compared to targeted methods.

Diagram 1: Conceptual workflow of MRM/SRM versus Full-Scan MS.

Comparative Performance Data

The choice between MRM/SRM and Full-Scan MS involves a direct trade-off between sensitivity and the breadth of information. Experimental data highlights the quantitative performance of these techniques.

Sensitivity and Quantitative Performance

MRM is renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in quantifying target analytes, even in complex matrices. A study analyzing over 600 pesticides and mycotoxins demonstrated that MRM on a modern triple quadrupole system could achieve limits of quantification (LOQ) at 1 ng/mL (ppb) for 89% of the compounds, even with a fast acquisition rate and an injection volume of just 1 µL [24]. This high sensitivity is crucial for detecting low-abundance proteins or contaminants.

Full-Scan MS, while useful for screening, typically requires a higher limit of detection. Research on food and feed matrices showed that for reliable mass assignment (<2 ppm error) of contaminants at low levels (10-250 ng/g) in complex samples, a high resolving power (≥50,000) is necessary [23]. Without sufficient resolving power, co-eluting interferences at the same nominal mass can compromise both selectivity and quantitative performance.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Experimental Studies

| Technique | Application Context | Reported LOQ/LOD | Key Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRM | Pesticide Analysis in Food [24] | 1 ng/mL (for 89% of 560 pesticides) | Fast MRM (3 ms acquisition rate), 1 µL injection volume. |

| MRM | Protein Quantification in Plasma [25] | Low µg/mL to ng/mL range (highly dependent on enrichment) | Often requires immunoaffinity depletion or target enrichment for low-abundance proteins. |

| Full-Scan MS | Residue Analysis in Food/Feed [23] | 10-250 ng/g (Requires ≥50,000 resolving power for <2 ppm mass error) | Single-stage Orbitrap; complex matrices (e.g., animal feed) required higher resolving power than simple ones (e.g., honey). |

| MRM | Nitrosamine Impurities in Risperidone [26] | LOQ: 0.23 - 0.93 µg/mL | LC-ESI-MS/MS, positive ion mode, MRM. |

Selectivity and Specificity

The two-stage mass filtering in MRM/SRM provides superior selectivity by monitoring a specific precursor ion and a unique fragment, minimizing background interference [2] [25]. This is paramount for compound confirmation, as it ensures the signal originates from the intended analyte.

Full-Scan MS relies on a single stage of mass analysis and chromatographic separation for selectivity. While high resolving power (as in Orbitrap instruments) can distinguish ions with small mass differences, it may not always resolve isobaric compounds with identical elemental composition [23]. The selectivity of Full-Scan MS is therefore more dependent on chromatographic separation and instrumental resolving power.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To illustrate how these techniques are applied in practice, here are detailed protocols from key studies.

Protocol 1: Fast MRM for Multi-Residue Analysis

This protocol, used for the analysis of over 600 pesticides and mycotoxins, highlights the optimization for high-throughput, sensitive quantification [24].

- Sample Preparation: Food matrices (avocado, soybean, tea) were spiked with analytes and extracted using the QuEChERS CEN method, followed by a specific cleanup procedure.

- Chromatography:

- Column: Phenomenex Kinetex C18 (2.1 x 100 mm, 2.6 µm).

- Gradient: 28-minute gradient with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid, 2mM ammonium acetate in water) and B (0.1% formic acid, 2mM ammonium acetate in methanol).

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Injection Volume: 1 µL.

- Mass Spectrometry (SCIEX 7500+ System):

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI).

- Acquisition Mode: MRM.

- Optimized Parameters: Dwell time: 1 ms, Pause time: 2 ms, Settling time: 5 ms. This resulted in a total of 1,462 MRM transitions monitored in a single injection.

- Data Processing: SCIEX OS software 3.4.0.

Protocol 2: Full-Scan MS for Comprehensive Residue Screening

This protocol emphasizes the critical role of resolving power for accurate mass assignment in untargeted screening [23].

- Sample Preparation: Honey and animal feed samples were spiked with 151 pesticides, veterinary drugs, and toxins at 10-250 ng/g levels.

- Chromatography: Liquid Chromatography separation.

- Mass Spectrometry (Orbitrap):

- Acquisition Mode: Full-Scan MS.

- Key Parameter: Resolving power was systematically varied from 10,000 to 100,000 (FWHM) to assess its impact on mass accuracy.

- Finding: A resolving power of ≥50,000 was required for consistent, reliable mass assignment (<2 ppm error) in complex matrices like animal feed. For simpler matrices like honey, 25,000 was often sufficient.

- Data Analysis: Mass extraction with narrow windows was dependent on the achieved mass accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of MRM/SRM assays, especially for complex biological samples, often requires a suite of reagents and materials to enhance sensitivity and specificity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted MS Quantification

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIS) | Provides precise normalization for quantification, accounting for sample loss and ion suppression [1] [25]. | Absolute quantification of peptides/proteins in proteomics; pharmacokinetic studies of drugs [27]. |

| Immunoaffinity Depletion Columns | Removes high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) to reduce dynamic range and reveal low-abundance targets [25]. | Quantification of low ng/mL level candidate protein biomarkers in plasma or serum. |

| Anti-peptide Antibodies | Enriches specific proteolytic peptides and their SIS counterparts from complex digests, dramatically improving sensitivity [25]. | Detection of very low-abundance proteins (e.g., potential biomarkers, signaling proteins). |

| Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) Chromatography | Offline fractionation method to reduce sample complexity prior to LC-MRM/MS analysis [25]. | In-depth proteomic analysis to increase the number of proteins quantified. |

| LC-MS/MS System (Triple Quadrupole) | The core instrumental platform for executing SRM/MRM experiments, offering high sensitivity and robustness [24] [2]. | All targeted quantification applications, from small molecules (drugs, contaminants) to peptides. |

The selection of an appropriate mass spectrometry technique is a strategic decision dictated by the analytical goals. For the validation of MRM pairs and confirmation of specific compounds, MRM/SRM is the unequivocal choice, offering unmatched sensitivity, selectivity, and quantitative robustness. Its ability to reliably detect and quantify predefined targets at low concentrations in complex matrices makes it indispensable for pharmaceutical quality control [26], clinical biomarker verification [25], and regulatory food safety testing [24].

Conversely, Full-Scan MS is a powerful discovery tool ideal for untargeted screening, metabolite identification, and applications where a comprehensive view of the sample composition is required [23] [28]. Its main limitation for confirmation and quantification is its inherently lower sensitivity and potential for interference in complex backgrounds.

For researchers focused on compound confirmation, the experimental path is clear: MRM/SRM provides the specific, sensitive, and reproducible data necessary to meet rigorous validation standards.

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), also known as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), is a targeted mass spectrometry technique that has become the gold standard for quantitative analysis in complex biological matrices [29] [30]. For researchers and drug development professionals validating MRM pairs for compound confirmation, this technique offers a powerful combination of sensitivity, selectivity, and quantitative robustness that is particularly valuable for biomarker verification, pharmacokinetic studies, and systems biology applications [25] [30]. Operating on a triple quadrupole platform, MRM achieves its analytical power through two stages of mass selection, monitoring specific precursor-to-product ion transitions that provide exceptional specificity against background interference [25] [30]. This guide examines the key advantages of MRM technology, supported by experimental data and comparisons with alternative analytical approaches.

MRM Fundamental Principles and Workflow

The core principle of MRM involves precise selection of a target precursor ion in the first quadrupole (Q1), fragmentation in the second quadrupole (Q2), and specific monitoring of a characteristic product ion in the third quadrupole (Q3) [30] [2]. This two-stage mass filtering significantly reduces chemical noise and enables reliable detection and quantification of target analytes even in highly complex samples like plasma, serum, and tissue extracts [25] [5].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and logical relationships in MRM method development:

Key Advantages of MRM Technology

Unmatched Selectivity in Complex Matrices

MRM's two-stage mass filtering provides exceptional selectivity, effectively distinguishing target analytes from co-eluting compounds and matrix components [5] [31]. The selection of specific precursor-product ion pairs creates a highly specific analytical channel that minimizes background interference [30]. For particularly challenging matrices, advanced MRM³ technology provides an additional fragmentation stage, further enhancing specificity by generating second-generation product ions that are virtually interference-free [31].

Experimental evidence demonstrates that MRM³ can completely eliminate co-eluting interferences that plague standard MRM assays. In one study analyzing clenbuterol in urine, MRM³ successfully removed a substantial co-eluting interference present in conventional MRM analysis, improving the limit of quantification by 10-fold [31].

Exceptional Sensitivity for Trace-Level Detection

MRM delivers extremely high sensitivity, enabling detection of target molecules at very low concentrations [5]. This capability is particularly crucial for detecting low-abundance biomarkers in plasma, which are often present at ng/mL to pg/mL concentrations [25]. The non-scanning nature of MRM increases sensitivity by nearly one to two orders of magnitude compared to full-scan MS techniques [25].

Recent advancements have further enhanced MRM sensitivity. The Sum-MRM (SMRM) approach, which sums multiple MRM transitions from different charge states of the same molecule, has been shown to boost detection sensitivity for large molecules while maintaining analytical specificity [32]. This approach counters the signal dilution that occurs when large biomolecules distribute into multiple charged forms during electrospray ionization [32].

Robust Quantitative Accuracy and Precision

MRM provides highly accurate quantification with a linear dynamic range spanning up to 5 orders of magnitude [30]. When combined with stable isotope-labeled internal standards, MRM assays demonstrate exceptional reproducibility and precision [30]. This quantitative robustness makes MRM particularly valuable for biomarker verification and pharmaceutical development, where reliable quantification is essential [25] [30].

Experimental validation studies consistently demonstrate MRM's quantitative capabilities. In one study developing a UPLC-MS/MS MRM method for analyzing traditional herbal formulas, the method showed recovery rates of 90.36-113.74% and precision with relative standard deviation ≤15%, confirming high reliability for quantitative analysis [33].

High-Throughput Multiplexing Capability

MRM enables simultaneous monitoring of multiple analytes in a single analytical run, providing significant advantages for large-scale screening applications [5] [30]. Scheduled MRM techniques can monitor more than 100 proteins in a single LC-MS run, making the technology suitable for verifying large sets of candidate biomarkers [25] [30]. This multiplexing capability surpasses traditional immunoassays, which have limited capacity for parallel analysis [25].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of MRM compared to alternative mass spectrometry techniques:

Table 1: MRM Performance Comparison with Alternative Mass Spectrometry Techniques

| Parameter | MRM | Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Analyzer | Triple Quadrupole | Quadrupole-Orbitrap/TOF | Quadrupole-TOF/Orbitrap |

| Resolution | 0.7 Da (285 @ m/z=200) [30] | 0.0033 Da (60,000 @ m/z=200) [30] | Variable, typically high |

| Mass Accuracy | ~250 ppm [30] | ~5 ppm [30] | High (~5 ppm) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (~500 peptides) [30] | Moderate (~500 peptides) [30] | Very High (entire proteome) |

| Sensitivity | Very High (ng/mL range) [25] [30] | High [30] | Moderate (10x lower than MRM) [30] |

| Quantitative Workflow | Targeted (predefined transitions) | Targeted (post-acquisition transition selection) | Global (targeted data extraction) |

| Best Application | High-sensitivity quantification of predefined targets | High-selectivity quantification with simplified method development | Discovery-scale targeted quantification |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MRM Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function and Importance in MRM Analysis |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Critical for accurate quantification; correct for matrix effects and variability [30] |

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Essential for method development and transition optimization; poor quality compromises accuracy [5] |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Sample cleanup and concentration; improve sensitivity and reduce matrix effects [32] |

| Immunoaffinity Depletion Columns | Remove high-abundance proteins; enhance detection of low-abundance biomarkers in plasma [25] |

| LC Separation Columns (C18, Phenyl, etc.) | Analyte separation before MS detection; different selectivities address various compound classes [33] [32] |

| Enzymes for Proteolysis (Trypsin) | Generate predictable peptides for protein quantification in bottom-up proteomics [25] |

Advanced MRM Methodologies and Applications

MRM³ for Enhanced Selectivity

MRM³ represents a significant advancement for analyzing challenging samples. This approach incorporates an additional fragmentation step in a linear ion trap, generating second-generation product ions that provide exceptional specificity [31]. The diagram below illustrates this enhanced workflow:

Sum-MRM for Sensitivity Enhancement

The SMRM approach significantly boosts detection sensitivity for large molecules by summing signals from multiple charge states [32]. Traditional MRM selects a single charged form of a large biomolecule as the precursor ion, distributing the total analyte signal and reducing sensitivity. SMRM counters this by superimposing signals from multiple MRM transitions, effectively utilizing more of the total ion current while maintaining specificity through chromatographic separation of background noise [32].

MRM technology delivers an unmatched combination of selectivity, sensitivity, and quantitative accuracy that makes it indispensable for compound confirmation research and targeted quantification in complex matrices. While alternative techniques like PRM offer higher resolution and DIA provides greater proteome coverage, MRM remains superior for high-sensitivity quantification of predefined targets [30]. Recent advancements including MRM³ and SMRM have further expanded MRM's capabilities, addressing challenging applications from low-abundance biomarker verification to complex pharmaceutical analyses [31] [32]. For researchers and drug development professionals requiring robust, reproducible quantification of specific analytes in complex biological samples, MRM continues to offer the gold standard for targeted mass spectrometry.

Developing Robust MRM Assays: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide

In targeted quantitative proteomics and metabolomics, the selective and sensitive detection of molecules relies heavily on Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM). The fundamental principle of MRM involves selecting a precursor ion (the intact molecule) and specific product ions (its fragments) to create a highly specific assay [34]. The particular combination of precursor ion, product ions, and their characteristic retention time is referred to as a transition [34]. Selecting the optimal precursor-product ion pair is the most critical step in designing a robust MRM assay, as it directly influences the method's specificity, sensitivity, and overall success in quantifying target compounds in complex biological matrices [35]. This guide objectively compares the data-dependent and data-independent methodologies used for this selection process, providing experimental protocols and data to inform researchers in drug development.

Core Concepts and Definitions

To understand the process of transition selection, one must first grasp the key terminology and the underlying principle of MRM:

- Precursor Ion: The initial, intact ion of the target compound (peptide or metabolite) selected for fragmentation in the first stage of mass spectrometry [34].

- Product Ion: A fragment ion generated from the collision-induced dissociation (CID) of the precursor ion, detected in the second stage of mass spectrometry [34].

- Transition: The specific pair of a precursor ion and a product ion used for monitoring and quantification [34].

- Proteotypic Peptides: For proteins, these are unique peptides that are characteristic of a specific protein and are readily detectable by mass spectrometry, forming the basis for the precursor ion selection [34].

The fundamental principle behind MRM is that for a given compound, a set of unique transitions can be programmed into the mass spectrometer. By focusing on specific masses at specific retention times, chemical noise is minimized, and sensitivity for quantifying the target analyte is maximized [34].

Methodologies for Selecting and Optimizing Transitions

Several experimental and computational approaches exist for selecting and validating optimal ion pairs. The following sections detail the most common protocols.

Experimental Protocol 1: Empirical Optimization via Direct Infusion

This hands-on method is considered the gold standard for establishing transitions for a novel compound.

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare Standard Solution: Dissolve a pure standard of the target analyte in a suitable solvent at a concentration of approximately 1 µg/mL.

- Direct Infusion: Infuse the solution directly into the mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS or GC-MS/MS) using a syringe pump, bypassing the liquid chromatography system.

- Precursor Ion Identification: Perform a full scan (MS1) to identify the molecular ion of the compound. Look for the most abundant ion species, which could be the

[M+H]⁺or[M-H]⁻ion or a relevant adduct (e.g.,[M+Na]⁺). This becomes the candidate precursor ion [35]. - Product Ion Spectrum Acquisition: Fix the first quadrupole (Q1) on the selected precursor ion mass. Ramp the collision energy in the collision cell (Q2) while scanning the third quadrupole (Q3) to generate a product ion scan (MS2). This spectrum reveals all potential product ions [35].

- Transition Selection: From the product ion spectrum, select 3-5 of the most intense and structurally specific fragment ions. The most abundant ion is typically chosen as the quantifier (for quantification), while the others serve as qualifiers (for confirmatory identity) [35].

- Collision Energy Optimization: For each short-listed precursor-product ion pair, systematically optimize the collision energy to maximize the signal intensity of the product ion.

Experimental Protocol 2: Library Mining and In Silico Prediction

This method leverages existing data to accelerate assay development, especially for large sets of targets.

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Source Identification: Mine spectral data from public repositories such as the PRIDE database for proteomics or GnPS for metabolomics [34]. Tools like MRMaid automate this process for human proteins by mining PRIDE evidence to suggest optimal transitions [34].

- Spectral Library Search: Query the database using the compound's identity or sequence. Retrieve experimentally observed spectra containing precursor and product ion information.

- Transition Ranking: Use algorithms to rank potential transitions based on metrics such as product ion intensity, peptide score (a weighted sum of spectral evidence and peptide characteristics), and observation probability across multiple experiments [34].

- In Silico Fragmentation: For compounds without experimental spectra, use software tools to predict theoretical fragmentation patterns and generate candidate product ions.

Performance Comparison of Selection Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary transition selection methodologies.

Table 1: Objective Comparison of Transition Selection Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Resource Intensity | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Optimization | Direct measurement of precursor and product ions from a standard [35]. | Low | High (requires pure standard and instrument time) | Novel compounds; final assay validation; when ultimate sensitivity is required. |

| Library Mining | Leveraging previously acquired, curated experimental spectra [34]. | High | Low | High-throughput projects; well-studied organisms/compounds; initial assay design. |

| In Silico Prediction | Computational prediction of theoretical fragments. | Very High | Very Low | Preliminary screening; when no experimental data exists (results require validation). |

Comparative Data: PRM vs. DIA for Quantitative Analysis

While MRM on a triple quadrupole is the historical gold standard, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) offers alternative acquisition modes. A recent study comparing Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) for quantifying hydrophilic compounds in white tea provides insightful experimental data [36].

Experimental Summary: The study developed both PRM and DIA methods on an HRMS platform to simultaneously quantify 44 hydrophilic compounds (amino acids, alkaloids, nucleosides, nucleotides). Both methods were validated by assessing linearity, limits of detection (LOD), and application to real tea samples [36].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data of PRM vs. DIA from Experimental Comparison [36]

| Performance Metric | Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.004 – 200 μg/mL | 0.004 – 200 μg/mL |

| LOD Range | 0.001 – 0.309 μg/mL | 0.001 – 0.564 μg/mL |

| Key Advantage | High specificity; uses product ion chromatograms to reduce background noise [36]. | Unbiased acquisition; captures all ions, enabling retrospective analysis [36]. |

| Key Limitation | Targeted; number of compounds per method is limited. | Complex data processing; requires spectral libraries for deconvolution. |

| Result | Caffeine content: 32,529.02 mg/kg | Caffeine content: 32,529.02 mg/kg |

| Suitability | Optimal for targeted quantification of a defined set of compounds. | Ideal for non-targeted screening or projects where targets may evolve. |

The Transition Validation Workflow

Selecting candidate transitions is only the first step. A rigorous validation process is essential to ensure the chosen pairs are specific and robust in the context of a complex sample matrix. The following diagram illustrates the critical steps for this validation.

A critical step in this workflow is testing candidate transitions in a real sample matrix to check for interferences. As noted by experienced practitioners, "It is depressing how often, in real samples, a beautifully promising transition gives an array of peaks," making it necessary to sometimes "reject one of your best initial transitions because it lacks specificity... and fall back on a less abundant transition that gives a clear peak" [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for the experimental protocols described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for MRM Transition Development

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Pure Analytical Standard | Serves as the reference material for empirical optimization of transitions and for generating calibration curves [35]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-IS) | Corrects for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation, crucial for accurate quantification. |

| Appropriate Solvent (e.g., MS-grade Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Used for preparing standard stock solutions and sample reconstitution, minimizing background interference. |

| Sample Matrix (e.g., Plasma, Urine, Tissue Homogenate) | Used to validate transition specificity and quantify matrix effects during method development [35]. |

| LC-MS/MS System (Triple Quadrupole) | The core instrument platform for developing and executing MRM assays [34]. |

| Spectral Library (e.g., PRIDE Database) | A public repository of experimental spectra used for in silico transition selection and validation [34]. |

Selecting optimal precursor-product ion pairs is a critical, multi-faceted process in MRM assay development. While empirical optimization remains the most reliable method for achieving maximum sensitivity, computational approaches using spectral libraries offer high-throughput advantages for large-scale projects. The choice of methodology should be guided by the project's scope, availability of standards, and required performance. Furthermore, the emerging data shows that HRMS-based techniques like PRM provide a powerful alternative to traditional MRM, offering high specificity and simplified method development. Ultimately, regardless of the selection method, rigorous validation in the intended sample matrix is non-negotiable for generating robust, publication-quality quantitative data.

In the field of targeted proteomics and quantitative mass spectrometry, the validation of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) pairs stands as a critical pathway for compound confirmation in biomedical research. MRM, a highly sensitive targeted mass spectrometry technique, has emerged as a powerful alternative to antibody-based methods for validating discovery-phase data and quantifying proteins in complex biological matrices [37] [17]. The technique operates on the principle of selecting precursor ions in the first quadrupole, fragmenting them in the collision cell, and monitoring specific product ions in the third quadrupole, thus providing exceptional selectivity and sensitivity for quantitative analyses [7].

The analytical power of MRM, however, is heavily dependent on the precise optimization of critical mass spectrometry parameters, particularly collision energy (CE) and declustering potential (DP). These parameters fundamentally govern the efficiency of ion transmission and fragmentation, directly impacting assay sensitivity, reproducibility, and overall robustness [7] [38]. Optimal CE facilitates the generation of abundant product ions, while appropriate DP ensures efficient ion declustering and transmission into the mass analyzer. This guide provides a comparative examination of optimization strategies for these parameters, presenting objective experimental data and protocols to inform researchers in drug development and clinical proteomics.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Methodologies

Traditional Equation-Based Approach vs. Experimental Optimization

The optimization of collision energy and declustering potential can be approached through generalized equations or through rigorous experimental determination. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of these two fundamental approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Equation-Based and Experimental Optimization Approaches

| Feature | Equation-Based Approach | Experimental Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Applies manufacturer-provided linear equations relating CE to m/z (e.g., CE = 0.034 × (m/z) + 3.314) [7] | Empirically tests a range of parameter values for each specific transition [7] |

| Throughput | High; quickly applicable to large peptide sets | Lower; requires individual assessment for each transition |

| Optimal Signal | May be suboptimal for non-typical peptides (e.g., with missed cleavages, non-tryptic) [7] | Aims to achieve maximum signal response for each specific transition [7] |

| Resource Demand | Low; minimal instrument time and effort | High; significant instrument time and data analysis |

| Best Use Case | Initial method scoping, large-scale screening where ultimate sensitivity is not critical | Final quantitative assay development, applications requiring maximum sensitivity and robustness |

Experimental data consistently reveals the limitations of relying solely on generalized equations. A systematic investigation demonstrated that for a set of 90 transitions from triply charged peptides, the optimal collision energy frequently deviated from the equation-derived value, sometimes by as much as ±6 volts [7]. This deviation can translate to a significant difference in signal intensity, directly impacting the sensitivity and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of an MRM assay.

Workflow for Experimental Parameter Optimization

A robust workflow for the experimental optimization of collision energy and declustering potential is essential for developing high-quality MRM assays. The following diagram illustrates the key steps in this process, from sample preparation to final parameter selection.

Advanced Rapid Optimization Strategy

For large-scale projects involving hundreds of transitions, a sophisticated rapid optimization method has been developed. This approach uses subtle adjustments to precursor and product m/z values (at the hundredth decimal place) to code for different collision energies. This allows a single precursor-product pair to be programmed as multiple MRM targets at different CEs, enabling the cycling and testing of multiple parameter values within a single LC-MS run, thereby eliminating run-to-run variability [7].

Table 2: Excerpt from a Rapid Optimization MRM Transition List

| Peptide | Original Q1 m/z | Original Q3 m/z | Adjusted Q1 m/z | Adjusted Q3 m/z | Adjusted CE (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.21 | 7.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.22 | 9.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.23 | 11.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.24 | 13.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.25 | 15.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.26 | 17.4 |

| TPHPALTEAK | 355.53 | 448.24 | 355.51 | 448.27 | 19.4 |

This method, functional on instruments like the Waters Quattro Premier and ABI 4000 QTRAP, was demonstrated to efficiently determine the optimal instrument parameters for each MRM transition, maximizing product ion signal and overall assay performance [7].

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Optimization

Protocol 1: Foundational Compound Optimization

This protocol is adapted from a general guide for LC-MS/MS compound optimization [38] and is applicable to small molecules and peptides.

Step 1: Standard Preparation

- Obtain a pure chemical standard of the target compound.

- Dilute to a suitable concentration (e.g., 50 ppb to 2 ppm) in a solvent compatible with the LC mobile phase (e.g., a mixture of water and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid).

Step 2: MS/MS Optimization via Direct Infusion

- Infuse the standard solution directly into the mass spectrometer, bypassing the LC.

- For the precursor ion ([M+H]+ or [M-H]- typically), perform a Q1 scan to confirm the m/z.

- Optimize the Declustering Potential (DP) by scanning through a range of voltages (e.g., ±20 V from the default) to find the value that yields the maximum intensity of the precursor ion.

- Introduce the precursor into the collision cell and optimize the Collision Energy (CE). Scan a range of CE values (e.g., 10-50 V) to generate a breakdown curve. Identify the CE that produces the most intense signature product ions.

Step 3: Establish MRM Transitions

- Select at least two MRM transitions per compound. The most intense transition serves as the quantifier for concentration calculation, while the second (and third) serve as qualifiers for confirmatory identification [38].

- A compound is confirmed when both MRM transitions are detected and their intensity ratio matches that of the pure standard within a pre-defined tolerance.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Peptide CE Optimization

This protocol details the rapid optimization strategy for large-scale proteomic studies, as demonstrated in a study optimizing 90 transitions from 22 peptides [7].

Step 1: Generate Transition List

- Compile a list of target MRM transitions, including peptide sequence, precursor m/z, product m/z, and a default CE calculated from a generalized equation.

Step 2: Program the m/z Adjustment Script

- Use a script (e.g., in Perl) to create multiple entries for each transition. The script rounds the precursor and product m/z to the nearest tenth, using the second decimal place to code for different collision energies.

- For example, to test CEs from 7.4 V to 19.4 V in 2 V steps for a single transition, seven unique MRM targets are created with subtly different Q1 and Q3 m/z values, each programmed with a different CE.

Step 3: Execute Single-Run Analysis

- The modified list containing all "unique" transitions is loaded into the instrument method.

- The sample is analyzed in a single LC-MS/MS run. The instrument rapidly cycles through all the programmed transitions.

- Software like Mr. M is used to process the data, easily visualizing the signal intensity at each CE and determining the optimal value for each original peptide transition.

Impact on Assay Performance and Validation

Rigorous optimization of CE and DP is not an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity for achieving the sensitivity and robustness required for clinical and preclinical applications. The downstream impact is quantifiable in key assay performance metrics.

In a large-scale study to develop MRM assays for 2118 unique proteins across 20 mouse organs, optimal CE was a critical factor in determining the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ). The LLOQ was rigorously defined as the lowest concentration where the coefficient of variation (CV) was less than 20% and the mean peak area was within ±20% of the expected concentration [39]. Suboptimal CE would have resulted in a higher LLOQ, impairing the ability to detect low-abundance proteins. Furthermore, the repeatability of the final assays was assessed using five independently prepared samples analyzed on five different days, a level of robustness that is unattainable without properly optimized parameters [39].

For clinical bioanalytical validation, as required for methods quantifying drugs and metabolites in human blood, optimized MRM parameters ensure the method meets strict validation criteria for precision (CV ±20%) and bias (±20%) across a wide range of analytes, as demonstrated in a method validating 520 psychoactive substances [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for successfully developing and executing optimized MRM assays.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MRM Assay Development

| Item | Function / Application | Representative Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards (SIS) | Internal standards for precise absolute quantification; corrects for sample prep and ionization variability [39]. | Synthetic peptides with heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N). |

| Sequencing-Grade Trypsin | Proteolytic enzyme for reproducible protein digestion to generate peptides for analysis [41] [39]. | Promega sequencing-grade modified trypsin. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for mobile phase to minimize background noise and ion suppression. | JT Baker HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile, methanol. |

| Mass Spectrometer Tuning & Calibration Solution | For regular instrument calibration ensuring mass accuracy and sensitivity. | Agilent ESI Tuning Mix [42]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample clean-up and peptide desalting to improve signal-to-noise ratio. | Waters Oasis MCX, Microspin C18 columns [7] [41]. |

| Protein Assay Kit | Accurate determination of protein concentration prior to digestion. | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit [41]. |

| Reducing & Alkylating Reagents | For denaturing proteins and preventing disulfide bond reformation during sample preparation. | Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), Iodoacetamide (IAA) [7] [41]. |

The optimization of collision energy and declustering potential is a non-negotiable step in the development of robust, sensitive, and reliable MRM assays for compound confirmation. While generalized equations offer a starting point, the empirical, transition-specific optimization of these parameters has been conclusively shown to enhance signal intensity, improve the lower limit of quantification, and ensure the reproducibility required for translational research and clinical assay validation. The methodologies and data presented herein provide researchers with a clear framework for implementing these critical optimization procedures, thereby strengthening the foundational thesis that meticulous MRM assay development is paramount to generating high-quality quantitative data in drug development and biomedical science.

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) represents a significant evolutionary advancement in chromatographic science, enabling superior peak resolution and faster analysis times compared to traditional High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). This technology leverages columns packed with smaller particles and instrumentation capable of operating at significantly higher pressures to achieve enhanced separation performance [43] [44]. For researchers validating Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) assays for compound confirmation, understanding and optimizing UHPLC conditions is paramount for developing robust, sensitive, and high-throughput analytical methods.

The fundamental principle underlying UHPLC performance stems from the van Deemter equation, which describes the relationship between linear flow velocity and plate height [44]. By utilizing stationary phases with particle sizes typically at 2 μm or less (compared to 3-5 μm for HPLC), UHPLC achieves flatter van Deemter curves, allowing faster flow rates without sacrificing efficiency [43]. This technological advancement directly addresses the critical need in MRM assay development for precise compound separation and confirmation within complex matrices, where resolution and speed are often competing priorities that must be carefully balanced.

Fundamental UHPLC Parameters for Separation Optimization