A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Chemiluminescent Materials for Advanced Bioanalysis

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate chemiluminescent materials for biological sample analysis.

A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Chemiluminescent Materials for Advanced Bioanalysis

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate chemiluminescent materials for biological sample analysis. It covers the foundational principles of chemiluminescence and explores innovative materials like MOFs and AIEgens. The guide details methodological applications across pharmaceutical and clinical diagnostics, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous validation protocols with comparative analyses against traditional techniques. The content synthesizes the latest advancements to ensure reliable, sensitive, and specific assay performance in complex matrices.

Core Principles and Next-Generation Chemiluminescent Materials

Chemiluminescence (CL) represents a unique class of chemical reactions that emit light as a result of electronic excited-state species formed through chemical processes, without the requirement of an external light source [1] [2]. This fundamental characteristic distinguishes CL from photoluminescence (such as fluorescence and phosphorescence), where light absorption precedes emission, and provides significant advantages for analytical applications, including minimal background interference, high sensitivity, and simplified instrumentation [3] [4]. In biological and medical research, CL systems have become indispensable tools for detection, imaging, and biosensing, particularly through the development of both natural and synthetic CL compounds [3] [2].

The exploration of CL mechanisms spans from foundational systems like luminol to sophisticated biological light-emission processes. Each system operates through distinct yet conceptually related pathways where chemical energy is converted directly into photon emission [1]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who utilize these systems for analyzing biological samples, detecting specific analytes, and developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic platforms [5] [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of major CL systems, detailing their reaction mechanisms, experimental protocols, and performance characteristics to facilitate informed selection and application in biomedical research.

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Chemiluminescence Systems

| System Type | Key Characteristics | Primary Excitation Mechanism | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct CL | Light emitted directly from the excited-state product of a chemical reaction | Chemiexcitation via intramolecular electron transfer | Luminol, Cypridina luciferin [2] |

| Indirect CL/CRET | Energy transfer from excited intermediate to a fluorophore | Chemiluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (CRET) | Peroxyoxalate systems [2] [4] |

| Bioluminescence (BL) | CL occurring in living organisms | Enzyme-catalyzed oxidation of substrate | Firefly luciferase, Renilla luciferase [3] [2] |

| Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) | Excitation triggered by electrochemical reactions | Electron transfer at electrode surfaces | Luminol electrochemical oxidation [2] [6] |

Fundamental Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The Luminol Oxidation Pathway

The luminol reaction represents one of the most extensively studied and utilized CL systems, particularly in forensic science and immunoassays [7] [8]. The mechanism begins with the deprotonation of luminol in basic conditions, forming a monoanion that undergoes oxidation to form a diazaquinone intermediate [7] [6]. This critical oxidation step can occur via one-electron or two-electron pathways, ultimately leading to the formation of a cyclic peroxide intermediate (a hydroperoxide adduct) [6]. The decomposition of this peroxide intermediate proceeds through a high-energy transition state, resulting in the elimination of nitrogen gas and formation of 3-aminophthalate in an electronically excited state [7] [9]. As this excited-state molecule relaxes to its ground state, it emits a photon with a wavelength of approximately 425 nm (blue light) [8] [6].

Recent theoretical investigations combining DFT and CASPT2 methodologies have provided enhanced molecular-level understanding of this process, demonstrating that the luminol dianion activates molecular oxygen without forming diazaquinone as a discrete intermediate [7]. Instead, the reaction proceeds through concerted oxygen addition and nitrogen elimination, with the peroxide bond playing a critical role in the chemiexcitation efficiency [7]. The excitation process is promoted by electron transfer from the aniline ring to the OO bond, creating an excited state that requires highly localized vibrational energy during chemiexcitation for proton transfer between amino and carbonyl groups to produce the light emitter [7].

Advanced Reaction Systems: Direct versus Indirect Chemiluminescence

Beyond the foundational luminol system, CL mechanisms can be broadly categorized as direct or indirect processes, each with distinct characteristics and applications [2]. In direct CL, the excited-state product of the chemical reaction itself emits light upon returning to the ground state, as exemplified by luminol, cypridina luciferin, and certain peroxide compounds [2]. These systems typically involve the formation of a high-energy intermediate (often a peroxide) that decomposes to yield an electronically excited product species [2].

In contrast, indirect CL operates through a chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer (CRET) mechanism, where the initial chemical reaction produces an excited intermediate that subsequently transfers energy to an adjacent fluorophore or photosensitizer [2]. This acceptor molecule then emits light at its characteristic wavelength. A prominent example is the peroxyoxalate system, where the reaction of TCPO (bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) oxalate) with hydrogen peroxide produces a high-energy intermediate (likely 1,2-dioxetanedione) that excites a fluorophore such as 9,10-diphenylanthracene, which then emits light [4]. This indirect mechanism enables wavelength tuning by selecting different fluorophores and often yields enhanced emission intensity compared to direct CL systems [2].

Comparative Performance Analysis of CL Systems

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

The selection of an appropriate CL system for specific research applications requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of major CL systems based on their emission characteristics, sensitivity, and practical implementation requirements.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Chemiluminescence Systems

| System | Emission Maximum (nm) | Quantum Yield | Key Reaction Components | Optimal pH Range | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol | 425 [8] [6] | ~0.01 [6] | Luminol, H₂O₂, Catalyst (Fe³⁺, Cu²⁺, HRP) [8] [6] | 8-11 [6] | Forensic blood detection, immunoassays, metal ion detection [8] |

| Peroxyoxalate (TCPO) | Depends on fluorophore (e.g., 425 nm with diphenylanthracene) [4] | Varies with fluorophore | TCPO, H₂O₂, Fluorophore [4] | Requires mixed solvent system [4] | HPLC detection, chemical sensing [4] |

| Firefly Luciferase | 560 (approx.) [3] | ~0.41 [3] | Luciferin, O₂, ATP, Mg²⁺ [1] [3] | 7.5-8.5 [3] | Bioluminescence imaging, gene expression assays, ATP detection [3] |

| Enhanced CL (ECL) | 425-430 (luminol-based) [6] | Enhanced vs. standard luminol | Luminol, H₂O₂, Enhancing agents (e.g., p-iodophenol) [6] | ~8.0 [6] | Western blotting, immunoassays [6] |

Experimental Factors Influencing System Performance

The performance of CL systems in biological sample analysis is significantly influenced by various experimental parameters. For luminol-based detection, the oxidation pathway is highly dependent on catalyst selection, with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enabling reactions at lower pH (8.0-8.5) compared to chemical catalysts that typically require pH 10-11 [6]. Metal ion catalysts like cobalt(II) can form peroxide complexes that facilitate the primary oxidation of luminol, while heme-containing proteins leverage their inherent peroxidase activity [6]. The emission intensity increases with pH up to approximately pH 11, reflecting increased dissociation of H₂O₂ into its more reactive anion form and diminished competition from non-chemiluminescent side reactions [6].

For advanced systems like peroxyoxalate CL, the reaction efficiency depends critically on solvent composition, often requiring mixed solvent systems to ensure reagent solubility and compatibility with analytes [4]. The energy transfer efficiency in indirect CL systems is influenced by the spectral overlap between the excited intermediate and the acceptor fluorophore, as well as their spatial proximity [2]. In biological applications, factors including tissue penetration depth, metabolic stability, and compatibility with physiological conditions become crucial considerations [3]. Bioluminescence systems typically offer superior signal-to-noise ratios in cellular and in vivo imaging due to the absence of background autofluorescence, while synthetic CL systems can be optimized for specific detection scenarios through chemical modification [3] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Standard Luminol-Based Detection Protocol

The following protocol details a standard method for chemiluminescence detection using the luminol-hydrogen peroxide system, adaptable for various analytical applications including immunoassays and biological sample analysis [6]:

Reagent Preparation:

- Luminol Stock Solution: Prepare 10 mM luminol in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 0.1 M sodium hydroxide. Store in a dark container at 4°C.

- Hydrogen Peroxide Solution: Prepare 0.1 M solution in deionized water. Standardize by UV absorbance at 240 nm (ε = 43.6 M⁻¹cm⁻¹).

- Carbonate Buffer: Prepare 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 10.5, by dissolving Na₂CO₃ (1.06 g) and NaHCO₃ (0.84 g) in 100 mL deionized water.

- Catalyst Solution: Prepare 1 mM horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in deionized water or 10 μM copper(II) sulfate for metal catalysis.

Assay Procedure:

- Mix 100 μL of sample or standard with 500 μL of carbonate buffer in a transparent cuvette or microplate well.

- Add 100 μL of catalyst solution and mix thoroughly.

- Initiate the reaction by adding 100 μL of hydrogen peroxide solution followed immediately by 200 μL of luminol stock solution.

- Measure light emission immediately using a photomultiplier tube, luminometer, or charge-coupled device (CCD) camera.

- For quantitative analysis, integrate the light signal over a predetermined time period (typically 30 seconds to 5 minutes).

Optimization Notes:

- For HRP-catalyzed reactions, the pH can be lowered to 8.0-8.5 while maintaining sufficient signal intensity [6].

- Signal duration can be extended by continuous reagent addition or using enhanced CL formulations containing proprietary enhancers.

- For biological samples, include appropriate controls to account for potential interferences from endogenous peroxidases or antioxidants.

Protocol for Nitric Oxide Metabolite Detection via Chemiluminescence

This specialized protocol demonstrates the application of CL for detecting nitric oxide metabolites in biological samples, highlighting critical considerations for sample handling to prevent artifacts [5]:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect blood samples using anticoagulant ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or heparin.

- Process plasma by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Avoid snap-freezing and thawing cycles, which promote interconversion of NO species [5].

- Analyze samples immediately or store at -80°C with minimal freeze-thaw cycles.

Reagent Setup:

- Prepare tri-iodide (I₃⁻) reagent by dissolving 1.0 g potassium iodide and 0.6 g iodine in 20 mL deionized water with 40 mL acetic acid.

- Alternatively, prepare acid sulfanilamide solution (5% w/v in 1 M HCl) for nitrite elimination controls.

- Prepare mercury chloride (HgCl₂) solution (10 mM) for selective S-nitrosothiol (SNO) detection.

Detection Procedure:

- Place 4 mL of I₃⁻ reagent in the purge vessel of the chemiluminescence analyzer.

- Purge with nitrogen gas for 5-10 minutes to eliminate oxygen.

- Inject 10-100 μL of sample into the reagent.

- Record the CL signal generated from the reaction of NO with ozone in the gas phase.

- For selective detection of different NO species:

- Nitrite: Pre-treat aliquots with acid sulfanilamide for 10 minutes to eliminate nitrite-derived signals.

- SNOs: Pre-treat with HgCl₂ (final concentration 0.1-1 mM) for 10-30 minutes to convert SNOs to nitrite.

- Calculate specific NO species concentrations by signal difference between treated and untreated samples.

Critical Methodological Considerations:

- Avoid "stop solutions" containing ferricyanide, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), or NP-40 detergent, as these can destabilize certain NO species and introduce artifacts [5].

- Account for signal quenching effects from residual blood components in the purge vessel [5].

- Include standard curves for each NO species (nitrite, S-nitrosothiols, heme-NO) using freshly prepared standards.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of chemiluminescence-based assays requires careful selection and preparation of specialized reagents. The following table outlines key solutions and their specific functions in CL research methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chemiluminescence Research

| Reagent/Chemical | Primary Function | Application Notes | Common Formulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) | Chemiluminescent substrate | Sensitivity to modifications: changes to heterocyclic ring abolish CL; substitutions on benzenoid ring can enhance intensity [6] | 1-10 mM in DMSO or alkaline aqueous solution [6] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Enzymatic catalyst | Enables reaction at physiological pH (8.0-8.5); used as label in immunoassays [6] | 0.1-1 mg/mL in buffer [6] |

| TCPO (bis(2,4,6-trichlorophenyl) oxalate) | Peroxyoxalate chemiluminescence reagent | Requires anhydrous conditions; reacts with H₂O₂ to form high-energy intermediate [4] | 10-50 mM in ethyl acetate or acetonitrile [4] |

| Enhanced CL Substrates | Signal amplification | Contains proprietary enhancers (e.g., p-iodophenol) that increase light output and duration [6] | Commercial formulations available |

| Tri-iodide Reagent | Detection of nitric oxide species | Converts various NO metabolites to NO gas for ozone-based detection [5] | KI/I₂/acetic acid mixture; must be fresh [5] |

| Stop Solution Components | Preservation of specific NO species | Actually promotes interconversion; use with caution for NO metabolite studies [5] | Typically contains ferricyanide, NEM, NP-40 [5] |

Methodological Challenges and Validation Considerations

The application of chemiluminescence systems to biological sample analysis presents several significant methodological challenges that require careful validation. Sample handling introduces substantial artifacts in CL assays, as demonstrated in studies of nitric oxide metabolites where room temperature placement, snap freezing, and thawing led to significant interconversion between different NO species [5]. Common preservation methods, including "stop solutions" containing ferricyanide, N-ethylmaleimide, and NP-40 detergent, may inadvertently destabilize target analytes rather than preserve them [5]. These findings highlight the critical need for method-specific validation when adapting CL protocols for novel applications.

The selectivity of CL detection represents another fundamental challenge, particularly in complex biological matrices. While CL offers exceptional sensitivity, its inherent versatility can limit selectivity in samples containing multiple potential interferents [6]. This limitation can be mitigated through coupling with separation techniques such as liquid chromatography or capillary electrophoresis, or by incorporating specific enzymatic steps or molecular recognition elements (antibodies, molecularly imprinted polymers) [6]. Researchers must also consider the dynamic equilibria between different reactive species in biological systems and the potential for signal quenching by sample components, which can lead to substantial underestimation of target analyte concentrations if not properly accounted for [5].

For imaging applications, CL systems face additional challenges related to light penetration through tissues, spatial resolution, and quantification accuracy. While bioluminescence imaging benefits from negligible background autofluorescence, the signal intensity decreases rapidly in deep tissues, limiting its application to small animal models or superficial structures [3]. The development of novel luciferase-luciferin pairs with red-shifted emission spectra and improved quantum yields represents an active area of research aimed at overcoming these limitations [3]. Similarly, the design of CL probes with appropriate physicochemical properties for target engagement and signal generation remains a crucial consideration for both in vitro and in vivo applications.

The validation of novel materials for biological sample analysis represents a critical frontier in biomedical research and drug development. Traditional analytical reagents, particularly natural enzymes,, , face significant limitations including poor stability under harsh conditions, high production costs, complex purification processes, and batch-to-batch variability [10] [11]. These challenges have driven the search for innovative material classes that can match or surpass the performance of conventional biological reagents while offering enhanced robustness and tailorability for specific diagnostic applications.

Within this context, three advanced material classes have emerged as particularly promising for chemiluminescent bioanalysis: Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), nanozymes, and Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens (AIEgens). MOFs offer exceptional structural diversity and porosity, enabling precise control over reaction environments. Nanozymes provide remarkable catalytic stability and tunable enzyme-mimicking activities at a fraction of the cost of natural enzymes. AIEgens defy conventional photophysical limitations by exhibiting enhanced emission in aggregated states, offering unprecedented opportunities for signal amplification in concentrated biological environments. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these three material classes, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental implementation, and potential to address longstanding challenges in chemiluminescent bioanalysis.

Material Class Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Definition and Core Characteristics

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a class of porous polymers consisting of metal clusters (secondary building units, or SBUs) coordinated with organic ligands to form one-, two-, or three-dimensional crystalline structures [12]. Their defining characteristic is their extraordinary porosity and surface area, which can be systematically tuned by selecting different metal clusters and organic linkers. The reticular synthesis approach allows for precise control over pore size and functionality, making MOFs particularly valuable for gas storage, separation, and catalytic applications [12].

Nanozymes are functional nanomaterials that exhibit intrinsic enzyme-mimicking activities [10] [11]. Since the landmark discovery in 2007 that Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles possess peroxidase-like activity, numerous nanomaterials including metals, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and MOFs have been found to mimic various natural enzymes such as peroxidase, oxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase [10] [13]. Unlike natural enzymes, nanozymes offer exceptional stability, lower production costs, ease of mass production, and customizable catalytic activities through nanomaterial engineering [10] [11].

Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens (AIEgens) represent a class of fluorescent materials that exhibit weak or no emission in molecularly dissolved states but become highly emissive in aggregated states [14]. This phenomenon stands in direct contrast to conventional fluorophores that suffer from aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ). The mechanism behind AIE is primarily attributed to the restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM), including rotations and vibrations, which blocks non-radiative pathways and activates radiative decay in the aggregated state [13] [14]. Recent research has revealed that some AIEgens can also generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), suggesting potential enzyme-like activities, leading to the emergence of the term "AIEzymes" [13].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Material Properties for Bioanalysis

| Property | MOFs | Nanozymes | AIEgens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Porous scaffolds, catalytic centers | Enzyme mimics, signal generators | Light emitters, photosensitizers |

| Structural Diversity | Very High (tunable porosity & topology) [12] | Moderate (varies by nanomaterial type) [10] | High (organic molecular diversity) [13] |

| Catalytic Activity | Variable (depends on metal nodes/ligands) [15] [16] | High (mimics peroxidases, oxidases, etc.) [10] [11] | Emerging (ROS generation, "AIEzymes") [13] |

| Optical Properties | Limited intrinsic emission | Variable (depends on composition) | Exceptional (bright aggregation-enhanced emission) [13] [14] |

| Stability | High (but can vary with metal-ligand combination) [12] | Very High (robust inorganic cores) [10] [11] | High (excellent photostability) [13] [14] |

| Surface Area | Extremely High (500-6000 m²/g) [12] | Moderate to High (depends on nanomaterial) | Low (molecular materials) |

| Signal Intensity | Moderate | High (for catalytic signal amplification) [10] | Very High (high quantum yield in aggregate state) [14] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Moderate | High (for catalytic assays) [11] | Very High (low background, large Stokes shift) [13] [14] |

| Production Cost | Moderate | Low (facile synthesis) [10] [11] | Moderate (organic synthesis required) |

| Functionalization Ease | High (coordination chemistry) [12] | High (nanomaterial surface chemistry) [10] | Moderate (covalent modification) |

Table 2: Analytical Performance in Representative Biosensing Applications

| Parameter | MOF-based Systems | Nanozyme-based Systems | AIEgen-based Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit (GSH) | - | 229.2 nM (Co-MOF nanozyme) [15] | - |

| Detection Limit (Tumor Biomarkers) | - | Comparable to ELISA [17] | - |

| Dynamic Range | Wide (tunable porosity) [12] | Wide (catalytic amplification) [11] | Wide (concentration-dependent aggregation) [13] |

| Assay Time | Minutes to hours | Minutes (rapid catalysis) [10] [11] | Minutes to hours |

| Multiplexing Capability | Moderate | Moderate | High (multiple emission colors) [14] |

| Reusability | Good (for some frameworks) | Excellent (robust catalysts) [11] | Limited (molecular probes) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Key Experimental Workflows

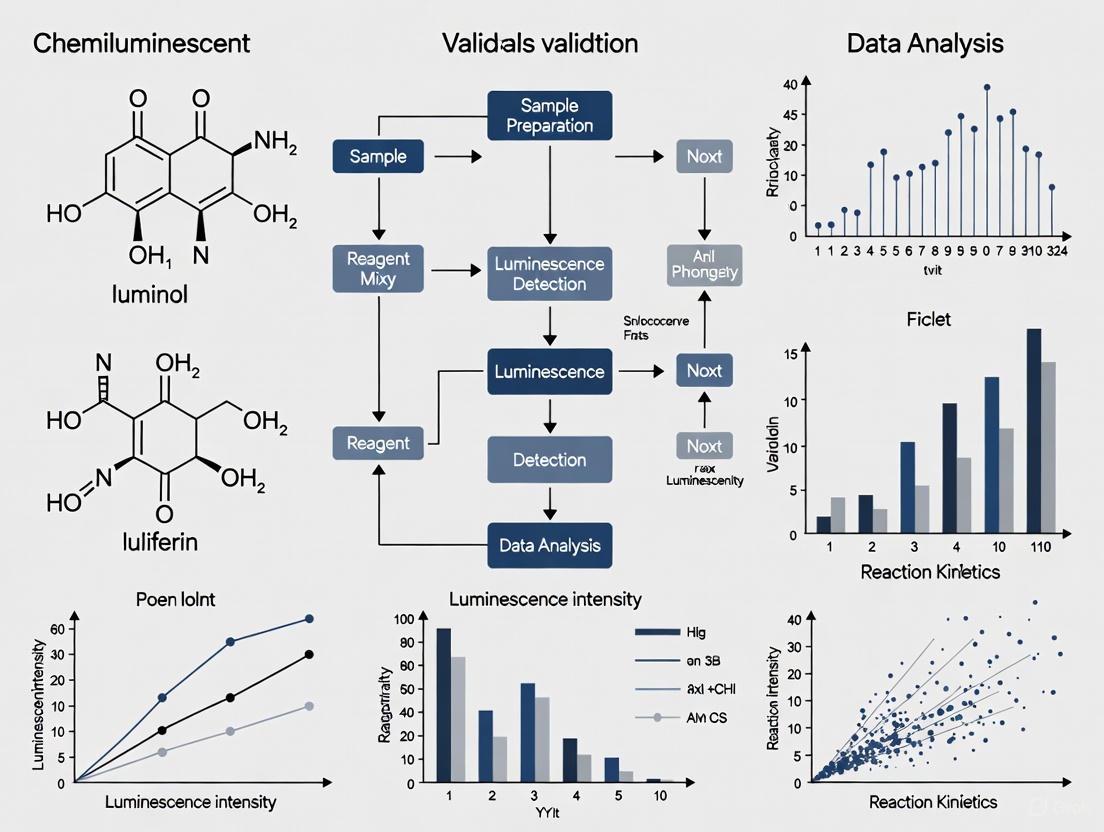

The practical implementation of these advanced materials follows distinct experimental pathways tailored to their unique properties. The workflow diagrams below illustrate common experimental setups for evaluating and utilizing each material class in bioanalytical applications.

Diagram 1: MOF Experimental Workflow illustrating the synthesis and application process for MOF-based bioanalysis, highlighting the solvothermal synthesis and subsequent activation steps critical for achieving porosity.

Diagram 2: Nanozyme Experimental Workflow showing the preparation of enzyme-mimicking nanomaterials and their implementation in catalytic biosensing assays.

Diagram 3: AIEgen Experimental Workflow depicting the design, synthesis, and application process for AIEgen-based bioanalysis, emphasizing the critical aggregation step that enables signal generation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MOF-Based Nanozyme for Glutathione (GSH) Detection [15]

- Materials Synthesis: Prepare a 2D Co-MOF (D-ZIF-67) nanosheet through a solvothermal reaction combining cobalt nitrate and 2-methylimidazole in methanol, followed by a delamination process to obtain ultrathin nanosheets with high specific surface area and numerous exposed active sites.

- Oxidase-like Activity Assessment: Test the oxidase-mimicking activity by incubating the Co-MOF nanosheets with 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate in acetate buffer (pH 4.0) at 37°C. Observe the color change from colorless to blue due to the oxidation of TMB to oxTMB, with the characteristic absorbance at 652 nm measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- GSH Detection: Introduce varying concentrations of GSH to the Co-MOF/TMB system. Monitor the reduction in blue color intensity or absorbance at 652 nm, as GSH inhibits the catalytic activity and reduces oxTMB back to colorless TMB. Generate a standard curve by plotting absorbance against GSH concentration, achieving a detection limit of 229.2 nM.

Protocol 2: Chemiluminescence Western Blot Using HRP-Mimicking Nanozymes [18]

- Protein Separation and Transfer: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane. Activate the PVDF membrane in methanol before incubation in transfer buffer.

- Membrane Blocking: Incubate the membrane in a blocking solution (non-fat dry milk or BSA in TBST) for 30 minutes to 1 hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Incubation:

- Primary Antibody: Incubate membrane with primary antibody (diluted 1:500 to 1:2,000 in blocking buffer) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Wash membrane to remove unbound antibodies.

- Secondary Antibody: Incubate with nanozyme-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:5,000 to 1:20,000) for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Chemiluminescent Detection: Prepare chemiluminescent substrate solution according to manufacturer's instructions. For HRP-mimicking nanozymes, use luminol-based substrates with hydrogen peroxide as the oxidant. Apply substrate to the membrane and capture the chemiluminescent signal using a digital imaging system or X-ray film, with exposure times optimized for signal intensity.

Protocol 3: AIEzyme-Based Chemiluminescence Detection [13]

- AIEgen Preparation: Synthesize or obtain AIEgens with demonstrated enzyme-like activity (e.g., compounds capable of generating singlet oxygen under light excitation).

- Chemiluminescence Assay: Under alkaline conditions, mix the AIEzyme with luminol in the absence of hydrogen peroxide. The AIEzyme catalyzes luminol oxidation through generated reactive oxygen species, producing sustained chemiluminescence.

- Signal Detection: Measure the chemiluminescence intensity using a plate reader or luminescence detector. The system demonstrates afterglow luminescence that continues after light irradiation stops, enabling sensitive detection without the need for external hydrogen peroxide addition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic substrate for peroxidase/oxidase mimics [10] [15] | Colorimetric detection in nanozyme-based sensors |

| Luminol | Chemiluminescent substrate for peroxidase mimics [18] | Western blot detection, chemiluminescent immunoassays |

| ABTS (2,2'-Azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Chromogenic substrate for peroxidase mimics [10] [11] | Antioxidant capacity assays, hydrogen peroxide detection |

| H₂O₂ (Hydrogen Peroxide) | Oxidant for peroxidase-mimicking reactions [10] [18] | Signal generation in catalytic assays |

| Zinc Nitrate/Cobalt Nitrate | Metal precursors for MOF synthesis [12] [15] | Construction of MOF structures with catalytic centers |

| Terephthalic Acid/Fumaric Acid | Organic ligands for MOF synthesis [12] [16] | Framework construction with tunable porosity |

| TPE (Tetraphenylethylene) | Fundamental AIEgen building block [13] [14] | Design of aggregation-induced emission probes |

| PVDF/Nitrocellulose Membranes | Protein immobilization substrates [18] | Western blotting, protein detection assays |

| Secondary Antibody Conjugates | Signal generation with target recognition [18] | Immunoassays, biosensor development |

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Insights

The fundamental mechanisms through which these advanced materials generate and amplify signals are critical to understanding their analytical performance. The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways for each material class.

Diagram 4: MOF Catalytic Mechanism showing how hard Lewis acid metals in MOFs activate substrates for hydrolysis by accepting electron lone pairs from carbonyl or phosphoryl groups.

Diagram 5: Nanozyme Catalytic Pathways illustrating the enzyme-mimicking mechanisms, particularly the Fenton reaction-based hydroxyl radical generation that drives substrate oxidation.

Diagram 6: AIEgen Signaling Mechanisms depicting how restriction of intramolecular motions in aggregated states leads to both enhanced fluorescence emission and reactive oxygen species generation for chemiluminescence applications.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that MOFs, nanozymes, and AIEgens each offer distinctive advantages for chemiluminescent bioanalysis. MOFs provide exceptional structural tailorability and high surface areas for analyte concentration and reaction engineering. Nanozymes deliver robust, cost-effective catalytic activity that can be fine-tuned through nanomaterial design. AIEgens introduce unique photophysical properties that overcome traditional limitations of fluorescent materials in concentrated biological environments.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on hybrid materials that combine the strengths of multiple material classes. Examples include MOF-based nanozymes with enhanced catalytic activity [15] [16] and AIEgen-functionalized nanozymes that integrate catalytic signal amplification with superior optical properties [13]. Such integrated approaches promise to address the ASSURED (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to end-users) criteria defined by the WHO for next-generation diagnostic tools [11].

As research progresses, these innovative material classes are poised to transform the landscape of biological sample analysis, enabling more sensitive, reliable, and accessible diagnostic platforms for research and clinical applications. Their continued development and validation will be essential for advancing personalized medicine and addressing emerging healthcare challenges.

Dopamine (DA) is a crucial neurotransmitter that controls central nervous system functions, cardiovascular, renal, and hormonal activities, and is significantly implicated in conditions ranging from Parkinson's disease to substance addiction [19]. The accurate and expeditious detection of minute concentrations of DA within human body fluids holds paramount significance in the advancement of novel diagnostic materials and electrode systems [20] [19]. Traditional detection methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography offer accuracy but rely on expensive instruments and professional operation, making them unsuitable for rapid, in-situ sensing [21].

In recent years, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as promising candidates for sensing applications due to their large specific surface area, tunable pore sizes, multiple functional sites, high stability, and ease of functionalization [22] [20]. Among these, manganese-porphyrin MOFs represent a specialized class of materials that combine the unique redox properties of manganese with the exceptional photophysical characteristics of porphyrins [23] [24]. This case study examines the development, performance, and application of a manganese porphyrin-based MOF for the ultra-sensitive detection of dopamine, situating this advancement within the broader validation of chemiluminescent materials for biological sample analysis research.

Material Synthesis and Characterization

Synthesis of Mn-Porphyrin MOFs

The manganese-porphyrin MOFs were synthesized via a facile one-pot method using manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate and 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (TCPP) as the organic ligand [23]. The direct synthesis approach involves a solvothermal reaction where a mixture of metal salts and organic ligands is heated in a high-boiling solvent such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) in a sealed reactor at 60-120°C under autogenous pressure [24]. This method results in high product yields with excellent crystallinity.

Porphyrin-based MOFs constructed using TCPP ligands benefit from structural versatility, tunable porosity, and high catalytic activity [21] [24]. The TCPP ligand is widely employed in developing stable porphyrin-based MOF sensors due to its excellent photophysical properties and ability to form coordinated structures with various metal ions [24]. The unique redox transition between Mn(III)-porphyrin and Mn(IV)-porphyrin centers confers exceptional catalytic properties to the resulting Mn-porphyrinic frameworks [23].

Key Structural and Functional Properties

The synthesized Mn-porphyrin MOFs exhibit several critical properties that make them ideal for sensing applications:

- Large surface area and high porosity: These characteristics allow for abundant active sites and enable mass transfer during catalytic processes [20].

- Tunable pore sizes: The customizable functional framework and variable pore size contribute to excellent selectivity for target molecules [24].

- Exceptional peroxidase-mimetic activity: The Mn-porphyrin centers demonstrate unprecedented catalytic efficiency, enhancing luminol/H₂O₂ chemiluminescence by over 1200-fold [23].

- Redox activity: The unique transition between Mn(III)-porphyrin and Mn(IV)-porphyrin centers provides the fundamental mechanism for catalytic function [23].

Performance Comparison with Alternative MOF Sensors

The performance of the manganese-porphyrin MOF-based sensor for dopamine detection demonstrates significant advantages when compared to other MOF-based sensors reported in recent literature. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MOF-Based Sensors for Dopamine Detection

| Sensor Material | Detection Mechanism | Linear Detection Range | Detection Limit | Application in Real Samples | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn-Porphyrin MOF | Chemiluminescence | 5-1000 nM | 3.95 nM | Human serum (98.3%-104.4% recovery) | [23] |

| Au@Ni-MOF | Electrochemical | 0.1 µM - 2 mM | Not specified | Human serum and urine | [19] |

| Suc-Ce-OH BioMOF | Fluorescence-Chemiluminescence | Not specified | Not specified | Food samples | [21] |

| Zr-Porphyrin MOFs | Luminescence | Varies by target | Not specified | Biological sensing | [24] |

The manganese-porphyrin MOF sensor demonstrates a remarkably wide linear detection range spanning three orders of magnitude (5-1000 nM) while maintaining an exceptionally low detection limit of 3.95 nM [23]. This combination of broad dynamic range and high sensitivity is particularly notable for clinical applications where dopamine concentrations can vary significantly.

When compared to alternative sensing platforms, the Mn-porphyrin MOF system offers several distinct advantages over traditional detection methods:

Table 2: Comparison with Traditional Dopamine Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Comparison with Mn-Porphyrin MOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Separation and quantification | Excellent selectivity, accurate quantification | Expensive equipment, time-consuming, requires separation steps | Mn-porphyrin MOF provides faster detection without separation steps [22] |

| Electrochemical Methods | Electron transfer reactions | Simplicity, portability | Moderate selectivity, electrode fouling | Mn-porphyrin MOF offers superior specificity through selective quenching [23] [20] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Detection of fluorescence changes | High sensitivity, fast response | Requires fluorophores, prone to interference | Mn-porphyrin MOF utilizes enhanced chemiluminescence with lower interference [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sensor Development and Optimization Protocol

The development of the Mn-porphyrin MOF-based chemiluminescence sensor for dopamine detection follows a systematic experimental protocol:

Step 1: Material Synthesis

- Prepare precursor solutions of manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate and TCPP ligand in appropriate solvents.

- Conduct solvothermal synthesis in a sealed reactor at controlled temperature (60-120°C) for 24-48 hours.

- Recover resulting crystals through centrifugation and wash with DMF to remove unreacted precursors.

- Activate the MOF through solvent exchange and drying under vacuum [23] [24].

Step 2: Sensor Characterization

- Analyze structural properties using powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) to verify crystallinity.

- Characterize morphological features through scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

- Confirm elemental composition using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) [21].

- Evaluate peroxidase-mimetic activity through catalytic assays with luminol/H₂O₂ substrate [23].

Step 3: Analytical Performance Evaluation

- Prepare dopamine standards across concentration range (1 nM - 1000 nM).

- Optimize reaction conditions including pH, temperature, and reagent concentrations.

- Establish calibration curve by measuring chemiluminescence intensity versus dopamine concentration.

- Determine detection limit based on signal-to-noise ratio (S/N = 3) [23].

Chemiluminescence Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for dopamine detection using the Mn-porphyrin MOF sensor:

Mechanism of Dopamine Sensing

The sensing mechanism relies on the selective quenching effect of dopamine on the Mn-MOFs/luminol/H₂O₂ chemiluminescence system [23]. The unique redox transition between Mn(III)-porphyrin and Mn(IV)-porphyrin centers confers exceptional peroxidase-mimetic activity to the framework, dramatically enhancing the luminol/H₂O₂ chemiluminescence reaction. Dopamine selectively quenches this enhanced chemiluminescence through a specific interaction with the active sites of the Mn-porphyrin MOF.

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway and mechanism of dopamine detection:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful development and implementation of Mn-porphyrin MOF-based dopamine sensors require several key research reagents and materials. The table below details these essential components and their specific functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mn-Porphyrin MOF Dopamine Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications | Role in Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manganese(II) Chloride Tetrahydrate | Metal precursor | MnCl₂·4H₂O, ≥99% purity | Provides metal centers for MOF construction and catalytic sites |

| 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin (TCPP) | Organic ligand | >95% purity, molecular weight: 790.72 g/mol | Forms porphyrin framework structure and enables redox activity |

| Luminol | Chemiluminescence substrate | 3-Aminophthalhydrazide, ≥97% purity | Generates light emission upon oxidation in presence of catalyst |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Co-substrate | 30% w/w solution, stabilized | Oxidizing agent for luminol chemiluminescence reaction |

| Dopamine Hydrochloride | Analytic standard | C₈H₁₁NO₂·HCl, ≥99% purity | Target analyte for method development and calibration |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Solvent | Anhydrous, 99.8% purity | Primary solvent for MOF synthesis and crystallization |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Buffer solution | 0.01 M, pH 7.4 | Provides physiological conditions for sensing experiments |

| Human Serum | Biological matrix | Pooled, sterile-filtered | Validates method performance in complex biological samples |

Application in Biological Sample Analysis

The manganese-porphyrin MOF-based sensor was successfully applied for the quantitative determination of dopamine in human serum samples, achieving an exceptional recovery rate of 98.3%-104.4% [23]. This demonstrates the method's accuracy and reliability for complex biological matrices, a critical requirement for clinical applications.

The successful implementation of this sensor in biological sample analysis validates the broader potential of chemiluminescent materials, particularly MOF-based systems, for biomedical sensing applications. The method's performance in serum samples confirms several advantages:

- High specificity: The selective quenching mechanism minimizes interference from other biological compounds.

- Excellent accuracy: Recovery rates near 100% indicate minimal matrix effects.

- Practical sensitivity: The detection limit of 3.95 nM is sufficient for measuring physiologically relevant dopamine concentrations.

- Robustness: The MOF structure remains stable and functional in complex biological environments.

These findings highlight the potential of manganese-porphyrin MOFs as efficient catalysts in chemiluminescence detection platforms, paving the way for their broader application in bioanalytical sensing [23]. The combination of exceptional catalytic activity, high sensitivity, and reliable performance in biological samples positions this material as a promising tool for clinical diagnostics and neuroscience research.

This case study demonstrates that manganese-porphyrin MOFs represent a significant advancement in chemiluminescent materials for biological sample analysis. The unprecedented peroxidase-mimetic activity, enabling over 1200-fold enhancement of luminol/H₂O₂ chemiluminescence, combined with the selective quenching response to dopamine, provides a highly sensitive and specific detection platform.

The successful application of this sensor for dopamine quantification in human serum samples, with excellent recovery rates, validates its potential for clinical diagnostics and biomedical research. The performance advantages over alternative MOF-based sensors and traditional detection methods position manganese-porphyrin MOFs as promising candidates for further development as versatile bioanalytical tools.

Future research directions should explore the application of similar manganese-porphyrin MOF structures for detecting other clinically relevant biomarkers, optimization of material properties for enhanced stability and sensitivity, and development of portable sensing devices for point-of-care applications. The exceptional catalytic properties and tunable nature of these materials suggest broad potential for advancing chemiluminescence-based detection across diverse biomedical applications.

Chemiluminescence is the conversion of chemical energy into the emission of visible light (luminescence) as the result of an oxidation or hydrolysis reaction [25]. This technology provides a very sensitive, cost-effective detection alternative to many radioisotopic and fluorescence techniques, and most chromogenic detection processes [25]. In biological research and drug development, chemiluminescence has become indispensable for detecting specific molecules at remarkably low concentrations, often down to the picogram or femtogram level, making it ideal for studying proteins in complex biological samples [18].

The strategic selection of chemiluminescent materials is paramount for achieving accurate and reproducible analytical results. Different enzymes, substrates, and membranes possess distinct properties that directly impact key performance parameters including sensitivity, dynamic range, signal duration, and background noise [18]. Understanding these properties enables researchers to align their material choices with specific experimental goals, whether for high-throughput drug screening, diagnostic assay development, or fundamental protein expression studies.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of chemiluminescent materials, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform evidence-based selection for biological sample analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Chemiluminescent Systems

Enzyme Systems: HRP vs. Alkaline Phosphatase

Two primary enzyme systems dominate chemiluminescent detection: Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). Each offers distinct advantages suited to different analytical scenarios.

Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) is a heme-containing enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of luminol, producing a light signal [18]. This system is favored for its high sensitivity and rapid signal generation, making it ideal for detecting low-abundance proteins [18]. The HRP-catalyzed oxidation of luminol involves a redox reaction where HRP catalyzes the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) into water and reactive oxygen species [18]. This process converts luminol into an unstable intermediate that eventually forms excited 3-aminophthalate, emitting light at 425 nm as it returns to its ground state [18].

Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) is an enzyme that dephosphorylates substrates, generating a detectable signal in both colorimetric and chemiluminescent assays [18]. AP is known for its stability and extended signal duration, allowing for longer exposures during detection processes, making it suitable for experiments requiring high sensitivity and signal persistence [18]. AP systems typically use 1,2-dioxetane-based substrates, which produce a highly sensitive light-emitting reaction when dephosphorylated [18].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of HRP and AP Enzyme Systems

| Parameter | HRP System | AP System |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Excellent for low-abundance proteins [18] | High, with extended signal duration [18] |

| Signal Kinetics | Rapid signal generation [18] | Sustained signal, suitable for multiple exposures [18] |

| Common Substrates | Luminol, Acridan-based [18] | 1,2-dioxetane-based (e.g., CSPD, CDP Star) [25] |

| Reaction Chemistry | Oxidation of luminol via H₂O₂ reduction [18] | Dephosphorylation of dioxetane substrates [18] |

| Optimal Use Cases | High-throughput assays, rapid detection | Experiments requiring signal stability, quantitative assays |

Substrate Formulations and Properties

Substrate selection critically influences detection sensitivity, signal strength, and duration. The chemical properties of different substrates determine their compatibility with specific analytical goals.

Luminol-based substrates, often used with HRP, provide highly sensitive detection for various biomolecules [18]. In the presence of HRP and hydrogen peroxide, luminol undergoes oxidation, emitting light that enables precise quantification of proteins, antibodies, or nucleic acids [18]. This method is favored for its cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and high sensitivity.

Acridan-based substrates for HRP and AP are chemiluminescent reagents that offer high sensitivity and enhanced signal stability [18]. These substrates are used in western blotting to detect proteins by generating light, which can be captured during the enzyme-substrate reaction for precise and sensitive analysis.

1,2-dioxetane-based substrates for AP produce a highly sensitive light-emitting reaction when dephosphorylated by AP [18]. These substrates generate a metastable dioxetane phenolate intermediate, which decomposes and emits light, making them ideal for detecting low-abundance proteins in western blotting and other applications [18].

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Chemiluminescent Substrates

| Substrate Type | Compatible Enzyme | Signal Duration | Sensitivity | Emission Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol-based | HRP [18] | Rapid, intense signal [18] | High [18] | 425 nm [18] |

| Acridan-based | HRP, AP [18] | Enhanced stability [18] | High [18] | Varies by formulation |

| 1,2-dioxetane-based | AP [18] | Prolonged, stable [18] | Excellent for low-abundance targets [18] | ~470 nm (CDP Star) [25] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental signaling pathways in HRP and AP chemiluminescent systems:

Membrane Selection for Optimal Protein Binding

The choice of membrane significantly impacts protein binding capacity, retention, and detection sensitivity. The two primary membrane types used in western blotting offer distinct advantages for different molecular weight targets.

Nitrocellulose membranes are commonly used in western blot analysis for their high protein-binding capacity, especially for low molecular weight proteins [18]. They provide fast transfer times and are ideal for detecting proteins with a smaller molecular size due to their consistent pore structure [18].

Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes are highly hydrophobic and offer excellent protein-binding capabilities, particularly for larger molecular weight proteins and glycoproteins [18]. They are durable, making them ideal for experiments requiring reprobing and long-term storage [18].

Experimental Protocols for Chemiluminescent Detection

Standard Chemiluminescent Western Blot Protocol

A robust western blot protocol ensures accurate and reproducible protein detection. The following step-by-step methodology outlines the critical phases from sample preparation to imaging:

Sample Preparation: Protein extraction is a critical step in preparing biological samples for analysis [18]. This process involves lysing cells to release their proteins, which are then measured to ensure accurate amounts are loaded for further experimental processes [18]. Consistent protein quantification is essential to maintain reliability in downstream techniques [18].

Protein Separation and Transfer: SDS-PAGE is a technique used to separate proteins by size [18]. After loading protein samples onto the gel, an electric current is applied, causing the proteins to migrate with smaller proteins moving faster through the gel matrix [18]. Once separated, the proteins are transferred onto a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane for detection [18]. For PVDF membranes, activation by soaking in methanol is required before incubation in transfer buffer [18].

Blocking the Membrane: Blocking is a crucial step to prevent the non-specific binding of antibodies to the membrane [18]. After transferring proteins onto the membrane, it is incubated in a blocking solution containing proteins such as non-fat dry milk or bovine serum albumin (BSA) in buffers like Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) [18]. Blocking typically lasts 30 minutes to 1 hour at room temperature or can be extended overnight at 4°C [18].

Antibody Incubation: Selecting the right primary antibody is crucial for success, as it ensures specific binding to the target protein [18]. The secondary antibody should be chosen based on the host species of the primary antibody and must be conjugated to a detection enzyme, such as HRP [18]. Typically, primary antibodies are diluted in the range of 1:500 to 1:2,000, and secondary antibodies are diluted between 1:5,000 to 1:20,000 [18]. Primary antibody incubation should be performed for approximately 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [18]. Secondary antibody incubation typically lasts for 1-2 hours at room temperature [18].

Substrate Application and Detection: Apply chemiluminescent substrate according to manufacturer's instructions. The signal is then captured using X-ray film or digital imaging systems [18]. Digital imaging systems offer superior sensitivity and flexibility over film-based methods, allowing for multiple exposures to optimize signal capture without saturation [18].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of the chemiluminescent western blot protocol:

Chemiluminescence Inhibition Assay for Antioxidant Quantification

The chemiluminescence inhibition assay provides a method to quantify the overall activity of low-molecular-weight antioxidants in biological samples [26]. This protocol is based on enhanced horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed luminol chemiluminescence and can be fine-tuned so that biological samples meet the requirements of the light detector [26].

The procedure is quick, inexpensive, and reproducible, making it applicable to diverse fields including crop breeding, medical diagnostics, and food sciences [26]. When processing five samples with five replicates sequentially, the protocol typically takes one working day to complete [26]. The assay measures the inhibition of chemiluminescence signal by antioxidants present in the sample, providing a summary parameter of total antioxidative capacity [26].

Light-Initiated Chemiluminescent Assay for Hormone Detection

The Light-Initiated Chemiluminescent Assay (LICA) represents an emerging homogeneous quantitative immunoassay technology with demonstrated excellent repeatability and intermediate imprecision in detecting hormones such as progesterone [27]. Performance characteristics of LICA for progesterone quantification show low coefficients of variation (calculated synthetic CV of 2.16%) and high reproducibility [27].

The LICA method exhibited excellent linearity in the assay measuring range (0.37–40 ng/mL for progesterone) with percentage deviation meeting quality requirements of allowable deviation of 10.00% [27]. The detection capability parameters for LICA included a limit of blank of 0.046 ng/mL, limit of detection of 0.057 ng/mL, and limit of quantitation of 0.161 ng/mL [27].

Performance Comparison with Alternative Detection Methods

Chemiluminescence offers distinct advantages over other detection methodologies, though each approach has appropriate applications depending on analytical requirements.

Colorimetric western blotting is a cost-effective method that produces a visible colored product on the membrane [18]. While simple and easy to perform, it is less suitable for low-abundance proteins due to potential background signals and does not allow for membrane stripping and reprobing [18].

Fluorescent western blotting provides a linear detection range, reducing the risk of signal saturation, especially in high-abundance proteins [18]. It allows for dual labeling, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple proteins in a single experiment [18]. The use of infrared fluorescent dyes increases sensitivity and allows for more accurate quantification of protein expression [18].

Radioactive detection, while highly sensitive, is less commonly used today due to health and safety risks associated with handling radioactive materials and the availability of safer, equally effective alternatives like chemiluminescence and fluorescence detection [18].

Table 3: Comparison of Western Blot Detection Methodologies

| Detection Method | Sensitivity | Dynamic Range | Multiplexing Capability | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence | High to excellent [18] [25] | Wide dynamic range [18] | Limited (sequential reprobing) | Relatively low hazards [25] |

| Colorimetric | Lower, less suitable for low-abundance targets [18] | Narrow | Limited | Safe |

| Fluorescence | High sensitivity [18] | Linear range [18] | Excellent (simultaneous multiplexing) [18] | Safe |

| Radioactive | Excellent [25] | Wide | Limited | Significant health hazards [25] |

Compared to autoradiography, chemiluminescence provides very good to excellent sensitivity, very sharp banding resolution, and significantly shorter exposure times (minutes to hours versus days to weeks) [25]. Additionally, chemiluminescence poses relatively low potential health hazards compared to the very high risks associated with radioactive methods [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of chemiluminescent detection requires strategic selection and combination of key reagents. The following toolkit outlines essential materials and their functions:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemiluminescent Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [18] | Catalyze chemiluminescent reaction | HRP for rapid, sensitive detection; AP for stable, prolonged signals [18] |

| Substrates | Luminol-based, Acridan-based, 1,2-dioxetane-based [18] | Generate light upon enzyme catalysis | Match to enzyme; consider sensitivity and signal duration requirements [18] |

| Membranes | Nitrocellulose, PVDF [18] | Immobilize transferred proteins | Nitrocellulose for low MW proteins; PVDF for high MW targets and reprobing [18] |

| Blocking Agents | Non-fat dry milk, BSA [18] | Reduce non-specific antibody binding | Milk for general use; BSA for phospho-specific antibodies [18] |

| Detection Systems | X-ray film, Digital imagers [18] | Capture chemiluminescent signal | Film for convenience; digital for quantitative analysis and dynamic range [18] |

Strategic selection of chemiluminescent materials requires careful consideration of analytical goals, sample characteristics, and performance requirements. HRP-based systems with luminol substrates offer rapid, high-sensitivity detection ideal for most routine applications, while AP-based systems with dioxetane substrates provide extended signal stability beneficial for quantitative assays requiring multiple exposures. Membrane choice should align with target protein characteristics, with nitrocellulose preferable for low molecular weight proteins and PVDF superior for larger proteins and experiments requiring reprobing.

The experimental data presented demonstrates that modern chemiluminescent methods achieve excellent sensitivity, precision, and linearity across diverse applications from western blotting to clinical hormone detection. By matching material properties to specific analytical goals through the framework provided in this guide, researchers can optimize detection capabilities for their biological sample analysis needs.

Implementation Strategies and Real-World Applications in Bioanalysis

Chemiluminescence (CL), the emission of light from a chemical reaction, has become a cornerstone technology in biomedical research and diagnostic assay design due to its exceptional sensitivity and broad dynamic range [28] [29]. Unlike fluorescence, CL does not require an excitation light source, which eliminates problems associated with background autofluorescence and photobleaching, resulting in a superior signal-to-noise ratio [29] [3]. The effectiveness of a chemiluminescence-based assay is profoundly influenced by the interplay between reagent formulation and the selection of an appropriate detection platform. This guide provides a comparative analysis of microplate-based systems and emerging portable sensors, offering experimental data and protocols to assist researchers in validating chemiluminescent materials for the analysis of biological samples.

Principles and Advantages of Chemiluminescence

A chemiluminescent reaction typically involves two key reactants, A and B, which form an electronically excited intermediate or product (C*). As this excited state relaxes to its ground state (C), a photon is emitted [28]. In many bioassays, this process is enhanced through sensitized or indirect chemiluminescence, where the excited product transfers its energy to a nearby fluorophore, which then emits light at its characteristic wavelength [28].

The overall efficiency of the process is governed by the chemiluminescence quantum yield, which is the proportion of reactant molecules that ultimately lead to photon emission. This yield depends on the efficiency of the chemical reaction, the conversion of chemical energy into electronic excitation, and the emission efficiency of the excited species [28]. While quantum yields for common systems like luminol are typically below 0.01, enzyme-catalyzed bioluminescence systems can achieve yields as high as 0.9, and certain diaryloxalates used in glow sticks reach around 0.5 [28]. The key advantage for analytical applications is that the absence of an excitation source provides extremely low background, allowing for highly sensitive detection even with relatively low quantum yields [28].

Reagent Formulation and Chemiluminescent Systems

The choice of reagent system is the foundational step in assay design, dictating the sensitivity, kinetics, and required conditions for detection.

Common Chemiluminescent Reagents

Table 1: Key Chemiluminescence Reagent Systems and Their Properties.

| Reagent System | Core Reaction Components | Typical Emission Wavelength | Key Characteristics & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol/H₂O₂ [28] [30] | Luminol, Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂), Catalyst (e.g., HRP, metal ions) | 425 nm [30] | Often used in immunoassays; catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or transition metal ions; signal can be enhanced with compounds like phenothiazine derivatives [31] [30]. |

| Acridinium Esters [29] [3] | Acridinium Ester, Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide | ~430 nm [3] | "Flash" kinetics (rapid light emission); used in automated immunoassays; does not require a catalyst. |

| Dioxetanes [29] [3] | Enzyme-Activatable Dioxetane Substrates (e.g., for Alkaline Phosphatase) | Varies (can be tuned) | "Glow" kinetics (long-lasting emission); extremely sensitive; widely used in Western blotting and DNA detection. |

| Bioluminescence (e.g., NanoLuc) [29] | Luciferase Enzyme (e.g., NanoLuc), Substrate (e.g., Furimazine) | 460 nm [29] | Very high quantum yield; high sensitivity and stability; genetically encodable; ideal for reporter gene assays and HTS. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key materials and reagents for developing a chemiluminescence assay.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [31] [30] | An enzyme label that catalyzes the oxidation of luminol by H₂O₂, generating a light signal. Highly stable with a high turnover number. |

| Luminol [32] [30] | A foundational CL substrate that, upon oxidation, produces a blue light emission at 428 nm. |

| Signal Enhancers (e.g., Phenothiazine derivatives) [31] [30] | Compounds that act as electron-transfer mediators to intensify and stabilize the light output from HRP-catalyzed luminol reactions. |

| NanoLuc Luciferase [29] | A small, engineered luciferase with high specific activity (>150x FLuc/RLuc) and stability. Ideal for sensitive reporter assays and protein tagging. |

| White or Grey Microplates [33] | Microplates with white wells reflect light, amplifying the weak CL signal. Grey or black plates with white inner coating reduce cross-talk between wells. |

| Black Microplates [33] | Used for bright luminescence assays to reduce background and cross-talk. Not suitable for weak signals due to signal quenching. |

| Smartphone-based Luminometer [32] [34] | A portable, cost-effective detection system that uses a smartphone camera to capture and quantify CL signals via a dedicated app, enabling point-of-care testing. |

Platform Integration and Comparative Performance

The detection platform significantly influences the workflow, scalability, and applicability of the assay.

Conventional Microplate-Based Systems

Microplates are the standard platform for high-throughput laboratory testing. For luminescence assays, white plates are recommended because they reflect the emitted light, thereby amplifying the signal and improving the lower detection limit [33]. The assay is typically read by a luminometer, which measures the Relative Light Units (RLUs). A key advantage of RLUs is their wide dynamic range, which can span from hundreds to millions, offering better analytical sensitivity and separation between data points compared to colorimetric Optical Density (OD) readings [35].

Diagram 1: Microplate CL Immunoassay Workflow.

Emerging Portable and Point-of-Care Sensors

Recent advances focus on miniaturizing CL detection for point-of-care (POC) applications. These systems often integrate paper-based micro-pads, 3D-printed dark boxes, and smartphones as signal capture and analysis devices [32] [34]. A major innovation in this area is the development of long-lasting "glow-type" CL systems, which overcome the traditional limitation of rapid signal decay ("flash" kinetics), thereby improving detection accuracy and reproducibility for in-situ monitoring [34]. For instance, modifying nanozymes with amino acids can slow reagent diffusion, producing a stable luminescence intensity crucial for use with smartphone cameras [34].

Diagram 2: Portable Smartphone-Based CL Sensor Workflow.

Performance Comparison: Colorimetric vs. Chemiluminescence ELISA

Table 3: A direct comparison between colorimetric and chemiluminescence ELISA formats.

| Parameter | Colorimetric ELISA | Chemiluminescence ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Enzymatic conversion of substrate (e.g., TMB) causing a color change [35]. | Enzymatic reaction with substrate (e.g., luminol) producing light emission [35]. |

| Readout | Optical Density (OD) at a specific wavelength (e.g., 450 nm) [35]. | Relative Light Units (RLUs) [35]. |

| Dynamic Range | Limited (OD readings typically 0–4) [35]. | Very broad (RLUs can range from hundreds to millions) [35]. |

| Sensitivity | Good | Superior, due to wider dynamic range and higher signal-to-noise [35]. |

| Required Plate | Clear plates [35] [33]. | Opaque plates (white or black) to contain/reflect signal [35] [33]. |

| Typical Workflow | Requires a final "stop solution" to halt the color development reaction [35]. | No stop solution needed; measurement is direct [35]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Microplate-Based DNA Detection using a Hybridization Assay

This protocol is adapted from a study detecting a hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA fragment [31].

- Conjugate Synthesis: Oxidize horseradish apoperoxidase (apoHRP) with sodium periodate. Dialyze and then react with an amino-modified capture oligonucleotide. Reduce the resulting conjugate with sodium borohydride and purify via ultrafiltration [31].

- Plate Coating: Coat a black high-binding polystyrene microplate with the synthesized apoHRP-capture oligonucleotide conjugate. Incubate at 4°C to allow passive adsorption of the protein component to the plate [31].

- Hybridization: Add the target DNA to the coated wells. Subsequently, add a biotinylated reporter oligonucleotide to form a sandwich complex. Incubate to allow for hybridization.

- Signal Generation: Introduce a Streptavidin-HRP conjugate, which binds to the biotin on the reporter oligonucleotide. After washing, add a enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (e.g., luminol with a phenothiazine enhancer) [31].

- Detection and Analysis: Immediately read the plate in a luminometer. The limit of detection (LOD) for this assay was reported as 3 pM, with a working range of 6–100 pM and a coefficient of variation (CV) below 6% [31].

Protocol: Portable Glucose Detection on a Paper-based Sensor

This protocol outlines the steps for a smartphone-integrated glucose biosensor [32].

- Sensor Fabrication: Create a wax-printed micro-pad (WPµ-pad) on a paper substrate to define hydrophilic sensing zones surrounded by hydrophobic barriers [32].

- Sensor Functionalization: Apply optimized concentrations of luminol (3 mM) and cobalt chloride (3 mM) onto the sensing zone. Incubate at 70°C for 20–25 minutes to activate the sensor [32].

- Glucose Reaction: Mix a sample containing glucose with glucose oxidase (GOx). Apply this mixture to the functionalized sensing zone. GOx oxidizes glucose, generating H₂O₂, which in the presence of cobalt ions, oxidizes luminol to produce light [32].

- Signal Capture and Analysis: Place the sensor in a custom 3D-printed dark box to eliminate ambient light. Use a smartphone app to capture an image of the chemiluminescence emission. The intensity is correlated to glucose concentration. This platform demonstrated a linear detection range of 10–1000 µM and an LOD of 8.68 µM [32].

The choice between microplate systems and portable sensors hinges on the specific application requirements. Microplate-based chemiluminescence remains the gold standard for laboratory environments where maximum sensitivity, high-throughput capacity, and quantitative precision are paramount, such as in drug discovery and clinical diagnostics [29] [35]. In contrast, portable chemiluminescence sensors offer a transformative potential for point-of-care testing, resource-limited settings, and applications requiring rapid, on-site results [32] [34]. While they may sometimes trade absolute sensitivity for convenience, innovations in glow-type chemistry and AI-powered signal analysis are rapidly closing this performance gap [32] [34].

In conclusion, the successful validation of chemiluminescent materials for biological analysis requires a holistic "reagent-to-platform" design strategy. Researchers must align the properties of the chemiluminescent system (kinetics, quantum yield) with the strengths of the detection platform (throughput, portability). The experimental data and protocols provided here serve as a foundation for making these critical decisions, enabling the development of robust, sensitive, and fit-for-purpose assays.

Chemiluminescence (CL) has emerged as a transformative analytical principle in biomedical research, characterized by the emission of light resulting from a chemical reaction without the need for an external light source [36]. This phenomenon offers distinct advantages for analyzing biological samples, including intrinsically ultra-low background signals, high signal-to-noise ratios, and exceptional sensitivity capable of detecting targets at picogram to femtogram levels [36] [18]. The validation of chemiluminescent materials and methodologies forms a critical thesis in modern bioanalysis, where accuracy, reproducibility, and scalability are paramount. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of chemiluminescence performance across three key application areas—pharmaceutical analysis, infectious disease serology, and therapeutic drug monitoring—contextualized within experimental frameworks and supported by quantitative data to inform researcher selection and implementation.

Fundamental Principles of Chemiluminescence Detection

Chemiluminescence occurs when chemical energy is converted directly into light energy through a reaction that produces an excited electronic state intermediate, which subsequently emits photons as it returns to its ground state [3]. The most significant CL systems in biological applications involve the oxidation of substrates like luminol or acridan by enzymes such as Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [18]. In the HRP-catalyzed oxidation of luminol, for instance, HRP catalyzes the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide, converting luminol into an excited-state 3-aminophthalate dianion that emits light at approximately 425 nm upon returning to its ground state [18] [37].

The core advantage of CL detection lies in its minimal background interference compared to fluorescence methods (which require external excitation light) and colorimetric methods (which rely on absorbance measurements) [3] [35]. This fundamental characteristic enables exceptional detection sensitivity and a broad dynamic range, making it particularly valuable for quantifying low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological matrices [36] [18].

Figure 1: Fundamental Chemiluminescence Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the core chemical mechanism where substrates, enzymes, and oxidants react to produce light emission through an excited state intermediate.

Performance Comparison Across Application Areas

The application of chemiluminescence spans multiple domains of biological analysis, each with distinct performance requirements and methodological considerations. The tables below provide a detailed comparison of key performance metrics and experimental parameters across the three primary application areas.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Application Areas

| Application Area | Detection Limit | Dynamic Range | Key Performance Advantages | Common CL System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Analysis [36] | Picogram to femtogram level | Broad (4-5 logs) | Ultra-high sensitivity for low-abundance compounds; Minimal sample preparation | HRP-Luminol-H₂O₂; Nanomaterial-enhanced |

| Infectious Disease Serology [38] [39] | High (20x more sensitive than colorimetric) [40] | Extended (RLUs: 100s to millions) [35] | Detects past exposure regardless of symptoms; Captures asymptomatic cases | HRP-Luminol; Acridan-based |

| Therapeutic Drug Monitoring [36] | Superior to HPLC/GC-MS for trace analysis | Broad linear range | Enables portable platforms for decentralized testing; Rapid analysis time | HRP-Luminol; AP-based dioxetanes |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol Parameters and Methodologies

| Application | Sample Type | Key Assay Format | Signal Detection Method | Critical Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Analysis [36] | Active pharmaceutical ingredients; Complex drug formulations | CL biosensors; Microarray assays | Photomultiplier tube; CCD imager | Nanomaterial integration for signal amplification; Matrix effect minimization |

| Infectious Disease Serology [38] [39] | Human serum/plasma; Saliva | Chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA); Western blot | Luminometer (RLU measurement) | Antibody specificity; Cross-reactivity assessment; Kinetics of antibody persistence |

| Therapeutic Drug Monitoring [36] [18] | Patient serum; Plasma | Automated CLIA platforms; Portable biosensors | Photodetector; CCD in microplate readers | Correlation with pharmacological effects; Narrow therapeutic index drugs |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chemiluminescent Western Blot for Protein Detection

The chemiluminescent western blot remains a cornerstone technique for protein analysis, valued for its exceptional sensitivity in detecting low-abundance proteins [18].

Sample Preparation: Extract proteins from biological samples using appropriate lysis buffers. Quantify protein concentration precisely using colorimetric assays (e.g., BCA assay) to ensure equal loading [18].

Electrophoresis and Transfer: Separate proteins by molecular weight using SDS-PAGE. Transfer proteins from gel to a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane using wet or semi-dry transfer systems. Activate PVDF membrane in methanol prior to transfer [18].

Blocking and Antibody Incubation:

- Block membrane with 5% non-fat dry milk or BSA in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Incubate with primary antibody (diluted 1:500-1:2,000 in blocking buffer) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Wash membrane 3× with TBST for 5 minutes each.

- Incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:5,000-1:20,000) for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Perform final washes (3× with TBST for 5 minutes each) [18].

Chemiluminescent Detection:

- Prepare enhanced chemiluminescent substrate by mixing luminol-based solution with enhancer (or oxidizing agent) according to manufacturer instructions.

- Incubate membrane with substrate for 3-5 minutes.

- Detect signal using digital imaging systems or X-ray film. Multiple exposures may be needed to optimize signal capture without saturation [18].

Figure 2: Chemiluminescent Western Blot Workflow. This experimental workflow details the sequential steps from protein separation to signal detection for analyzing specific proteins in complex mixtures.

Protocol 2: Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CLIA) for Serological Analysis

CLIA provides a robust platform for detecting pathogen-specific antibodies, offering superior sensitivity compared to colorimetric ELISAs [35].

Assay Principle: Utilize sandwich immunoassay format with specific capture antibodies coated on microplate wells. For serological applications, this may involve coating with pathogen-specific antigens to detect corresponding antibodies in patient samples [35].

Procedure:

- Add standards, controls, and samples to appropriate wells. Incubate to allow analyte binding to coated antibody.

- Wash plate to remove unbound materials using automated or manual plate washers.

- Add detection antibody conjugated with HRP or AP. Incubate to form antibody-analyte-antibody sandwich complexes.

- Wash plate thoroughly to remove unbound detection antibody.

- Prepare chemiluminescent substrate: For HRP, use luminol-based substrate with hydrogen peroxide; for AP, use dioxetane-based substrate [35].

- Add substrate to wells and incubate for precise duration (typically 5-10 minutes).

- Measure light emission using a luminometer, reporting results as Relative Light Units (RLUs) [35].