A Practical Guide to ICH Q2(R1) Method Validation for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying ICH Q2(R1) guidelines to the validation of analytical methods for pharmaceutical residue analysis. It covers foundational principles, from understanding regulatory requirements and defining key validation parameters like specificity, accuracy, and precision, to their practical application in methods for cleaning validation and impurity testing. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, optimization strategies for low-level residue detection, and the implementation of modern, risk-based lifecycle approaches, including trends toward ICH Q2(R2) and Quality-by-Design (QbD). The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop robust, compliant, and reliable analytical procedures that ensure product safety and quality.

A Practical Guide to ICH Q2(R1) Method Validation for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying ICH Q2(R1) guidelines to the validation of analytical methods for pharmaceutical residue analysis. It covers foundational principles, from understanding regulatory requirements and defining key validation parameters like specificity, accuracy, and precision, to their practical application in methods for cleaning validation and impurity testing. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, optimization strategies for low-level residue detection, and the implementation of modern, risk-based lifecycle approaches, including trends toward ICH Q2(R2) and Quality-by-Design (QbD). The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop robust, compliant, and reliable analytical procedures that ensure product safety and quality.

Understanding ICH Q2(R1) and Its Role in Pharmaceutical Residue Control

The Critical Importance of Validated Methods for Residue and Impurity Analysis

In the development and manufacturing of biopharmaceuticals, profiling process-related impurities and residuals is not merely a scientific best practice but a firm regulatory expectation [1] [2]. These impurities, which can be introduced at various stages of bioprocessing—from upstream cell culture to downstream purification—must be monitored and controlled to ensure patient safety and product quality [1] [3]. Because these residuals are typically present at low levels within complex and variable sample matrices, the development, validation, and application of robust analytical methods present a significant scientific challenge [1] [2]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, "Validation of Analytical Procedures," provides the foundational framework for demonstrating that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and consistency of the data used to make critical decisions about drug substance and drug product quality [4] [5].

Adherence to ICH Q2(R1) is crucial for global regulatory submissions, and it outlines the key validation parameters required for a variety of analytical procedures [4] [6]. This article will explore the major classes of process-related impurities, compare the analytical techniques used for their detection, and detail the experimental protocols for method validation, all within the critical context of ICH Q2(R1).

Bioprocessing is a complex sequence of steps, each of which can introduce specific residual impurities that must be cleared from the final product [1] [2]. These impurities can be broadly categorized based on their origin in the manufacturing process.

Table 1: Common Classes of Process-Related Impurities

| Impurity Class | Examples | Typical Origin in Process |

|---|---|---|

| Host Cell-Derived | Host Cell Proteins (HCP), DNA, RNA [1] [2] | Cell lysis following upstream culture [1] |

| Upstream Additives | Antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin, Gentamicin), Inducers (e.g., IPTG) [1] [2] | Cell-culture media to control contamination or induce expression [1] |

| Process-Enhancing Agents | Solubilizers (e.g., Guanidine, Urea), Reducing Agents (e.g., DTT, Glutathione) [1] [2] | Steps for solubilization, reduction, and refolding of proteins [1] |

| Downstream Reagents | Surfactants (e.g., Triton X-100, Tween), Chromatographic Ligands, Organic Solvents [1] [2] [3] | Purification, separation, and formulation steps [1] |

| Extractables & Leachables | Phthalates, Antioxidants, Metal Ions [2] [3] | Single-use bioprocessing systems like bags, filters, and tubing [2] |

Analytical Techniques for Impurity Monitoring

A diverse array of analytical techniques is required to detect and quantify the wide range of potential residual impurities, each with specific strengths for different types of analytes and matrices.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Analytical Techniques for Residual Impurity Analysis

| Analytical Technique | Best Suited For | Typical Sensitivity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Non-volatile organics (Antibiotics, Surfactants, Inducers) [1] [3] | Part-per-billion (ppb) levels [1] [2] | High selectivity and sensitivity; uses specific daughter ions for quantification [1] |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Volatile and semi-volatile organics (Residual Solvents) [1] [2] | Varies by analyte and detector | Robust technique for volatile impurities; can use headspace sampling [1] |

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry) | Elemental Impurities (Metal Ions, Inorganics) [2] [3] | Very high (e.g., parts-per-trillion) | Capable of multi-element analysis; extremely sensitive for metals [3] |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) | Ionic species [1] | Low concentrations of ions [1] | High selectivity for charged molecules [1] |

| PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | Residual Host Cell DNA [1] [2] | High (amplifies few copies) [1] | Highly specific and sensitive for trace DNA contamination [1] |

| ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | Host Cell Proteins (HCP) [1] [2] | Varies by kit | High throughput; specific to a given cell line [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: LC-MS/MS for Trace Antibiotic Analysis

- Sample Preparation: The complex sample matrix, often containing the protein of interest, may require protein precipitation. The supernatant is obtained via centrifugation or filtration, with validation to ensure the target impurity is not co-precipitated [1]. Further sample clean-up may involve liquid-liquid extraction [1].

- Chromatographic Separation: The sample is introduced to a High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system, where components of the mixture are separated based on their partition between a stationary phase and a mobile phase gradient [2].

- Detection & Quantification: Eluting components are ionized in the mass spectrometer's ion source (e.g., by electrospray). The triple quadrupole mass analyzer first selects the parent ion of the target antibiotic, fragments it in a collision cell, and then selects a specific daughter ion for highly selective and sensitive quantification, often using Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) [2] [3]. The use of internal standards is common for accurate quantitation [2].

Protocol 2: PCR for Residual DNA Clearance

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is isolated from the sample.

- Amplification: The DNA is heat-denatured into single strands. Specific oligonucleotide primers complementary to the 3' ends of the target host cell DNA sequence are added in excess. These primers hybridize with their complementary sequences when the temperature is lowered. A heat-stable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase) then extends the primers to synthesize new DNA strands [2].

- Detection: The cycle of denaturation, annealing, and extension is repeated multiple times, exponentially amplifying the target DNA fragment to a detectable level, confirming the presence and allowing for quantification of residual DNA [1] [2].

The ICH Q2(R1) Validation Framework

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline, "Validation of Analytical Procedures," provides a harmonized framework for validating analytical methods to ensure they are reliable and reproducible for their intended use [4] [5]. It defines the key validation characteristics that must be evaluated.

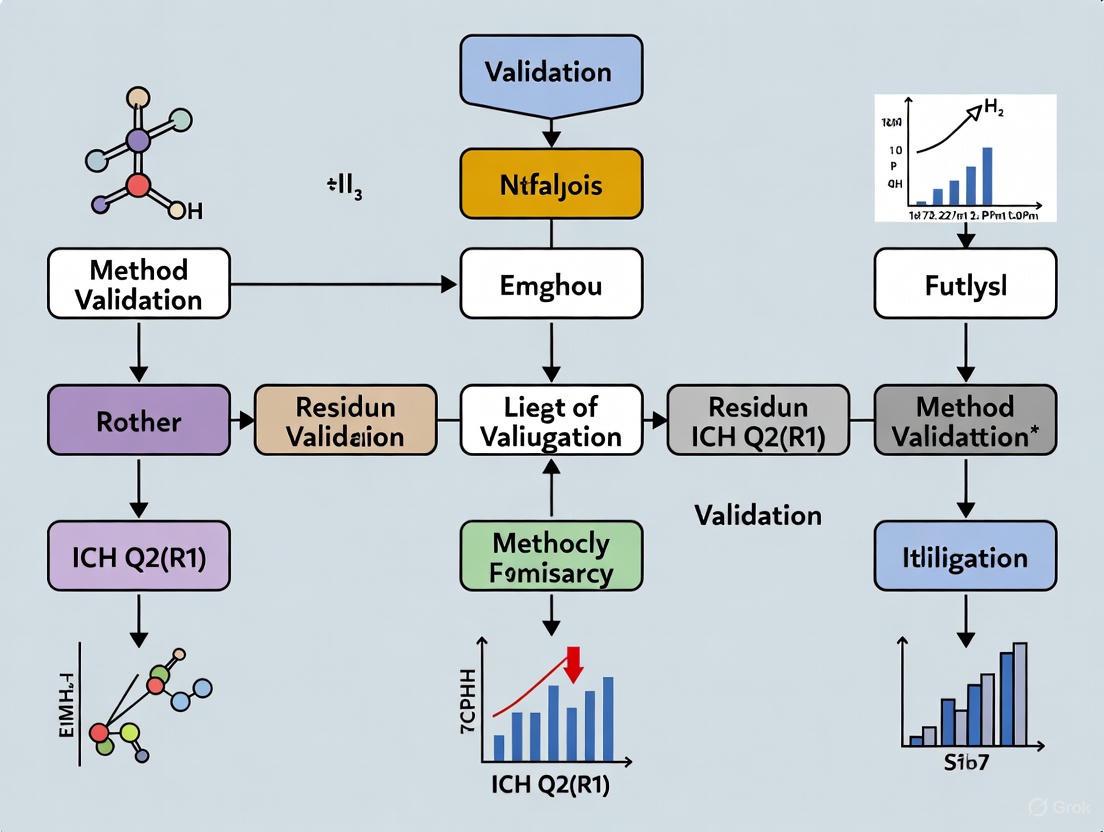

Diagram 1: ICH Q2(R1) Method Validation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the interconnected sequence of validation parameters that must be assessed to confirm an analytical procedure is fit for purpose.

Table 3: Core Validation Parameters as Defined by ICH Q2(R1)

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Experimental Approach for Impurity Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components [5] | Demonstrate resolution of impurity peak from the main product and other potential impurities (e.g., degradants) [5] |

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value [5] | Spike recovery experiments in the sample matrix (e.g., drug substance/product) at known concentrations [5] |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among individual test results (includes repeatability and intermediate precision) [5] | Multiple analyses of homogeneous sample by same analyst (repeatability) and different analysts/days/instruments (intermediate precision) [5] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration [5] | Analyze samples with impurity across a defined range (e.g., from LOQ to 120% or 150% of specification) [5] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower concentration with suitable linearity, accuracy, and precision [5] | Established based on linearity data and the intended use of the method (e.g., from LOQ to 150% of specification) [5] |

| LOD / LOQ | Lowest amount detected (LOD) or quantified with accuracy and precision (LOQ) [5] | Signal-to-noise ratio or based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [5] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [5] | deliberate variations in parameters (e.g., HPLC column temperature, mobile phase pH, flow rate) [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The development and execution of validated methods for residue analysis require specific, high-quality reagents and materials.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Impurity Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to the sample prior to analysis by LC-MS/MS or GC-MS to correct for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation, improving accuracy and precision [2]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Highly purified and well-characterized analytes used for calibration and qualification; essential for demonstrating method accuracy and linearity [5]. |

| MS-Grade Mobile Phase Modifiers | High-purity solvents and additives (e.g., formic acid, ammonium acetate) for LC-MS that minimize background noise and ion suppression, enhancing sensitivity [1]. |

| Specific Antibodies for ELISA | Antibodies raised against a spectrum of Host Cell Proteins (HCP) from the specific production cell line; critical for the specificity of HCP assays [1] [2]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers for PCR | Synthetic oligonucleotides designed to be complementary to the host cell's genomic DNA; ensure the specific and sensitive amplification of residual DNA [2]. |

Within the highly regulated biopharmaceutical industry, the critical importance of validated methods for residue and impurity analysis is unequivocal. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides the essential, globally recognized framework for proving that these analytical procedures are scientifically sound and fit for their purpose—ensuring that potentially harmful process residuals are accurately monitored and controlled to safe levels [4] [5]. As the industry evolves with more complex molecules and advanced technologies, the principles of ICH Q2(R1) remain the bedrock of quality control. The strategic application of sophisticated techniques like LC-MS/MS and PCR, guided by a thorough understanding of validation parameters, is fundamental to upholding the highest standards of patient safety and drug product quality.

Defining the Four Core Types of Analytical Procedures in ICH Q2(R1)

Analytical procedures are fundamental to ensuring the identity, purity, and content of pharmaceutical products, forming the foundation of product quality and patient safety [7]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," serves as the globally recognized standard for validating these analytical methods [8] [9]. This guideline harmonizes requirements across major regulatory regions, including the United States, Europe, and Japan, providing a unified framework for pharmaceutical analysis [9]. Validation under ICH Q2(R1) demonstrates that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose and will yield reliable and reproducible results throughout its lifecycle [7]. For researchers focused on pharmaceutical residue analysis, a thorough understanding of these procedure categories and their respective validation requirements is not just a regulatory formality but a critical scientific endeavor to ensure data integrity and product quality.

The Four Core Types of Analytical Procedures

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline primarily categorizes analytical procedures based on their fundamental objectives in assessing pharmaceutical quality. These categories directly address the core quality attributes of a drug substance or product.

Identification Tests

Purpose and Scope: Identification tests are designed to confirm the identity of an analyte in a given sample, ensuring that the drug substance present is indeed what is declared [7]. This is a fundamental requirement for all pharmaceutical products, as it verifies that the patient is receiving the correct active pharmaceutical ingredient. These tests typically work by comparing a property of the sample analyte to that of a authenticated reference standard.

Common Techniques and Examples:

- Spectroscopic Techniques: Techniques such as Infrared (IR) spectroscopy or Mass Spectrometry (MS) are commonly used for identity confirmation by matching spectral fingerprints to reference materials [10].

- Immunoassays: Techniques like Western Blotting or immunofluorescence use specific antibody-antigen interactions to identify proteins or viral antigens, commonly applied for biologics and vaccines [7].

- Genetic Methods: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is employed for identifying viral vaccines or products containing nucleic acids by amplifying specific, unique gene sequences [7].

- Chromatographic Methods: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with retention time matching against a reference standard can serve as an identity test.

- Simple Chemical Tests: Pharmacopoeias often include straightforward identification methods such as color reactions or precipitation tests for active pharmaceutical ingredients [7].

Testing for Impurities

Purpose and Scope: Impurity tests are crucial for defining the purity profile of a drug substance or product, detecting and quantifying unwanted chemical species that may arise from synthesis, degradation, or storage [7]. These procedures ensure that all impurities are below acceptable safety thresholds, thereby demonstrating the product's harmlessness to patients. Impurity testing can be performed as either quantitative tests, which determine the exact amount of an impurity present, or limit tests, which simply verify that an impurity is below a specified acceptance level [7].

Common Techniques and Examples:

- Chromatographic Methods: HPLC with various detectors (UV, MS) is the workhorse for impurity separation and quantification, especially for related substances in small molecules.

- Limit Tests for Contaminants: Tests for residual solvents, heavy metals, or arsenic often employ specific limit tests as described in pharmacopoeias [7].

- Electrophoretic Techniques: Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) is used for separating charged impurities, particularly relevant for biologics like proteins and peptides.

Assays (Content/Potency)

Purpose and Scope: Assays are quantitative procedures designed to measure the amount or potency of the major analyte in a sample [7]. These tests serve two primary functions: they determine the content of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (how much is present) and they may assess the potency (biological activity) of the substance. This dual approach ensures that the drug contains the claimed amount of active ingredient and that the ingredient possesses the intended therapeutic activity.

Common Techniques and Examples:

- Content Assays: UV-Vis spectrophotometry for concentration determination or HPLC-UV assays for specific compound quantification are standard for content determination [7].

- Potency Assays (Bioassays): For biologics, cell-based assays measure the biological effect of a molecule, such as a clot lysis assay for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or cell proliferation assays for growth factors [7].

- Viral Titrations: For live viral vaccines, Plaque Forming Unit (PFU) assays determine the concentration of infectious virus particles, which correlates with vaccine potency [7].

- Enzymatic Activity Assays: These measure the catalytic activity of enzyme therapeutics, often using substrate-to-product conversion metrics.

Table 1: Core Analytical Procedure Types in ICH Q2(R1)

| Procedure Type | Primary Objective | Key Validation Parameters | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification Tests | To verify the identity of an analyte [7] | Specificity [7] | IR spectroscopy, PCR, peptide mapping [7] |

| Impurity Tests (Quantitative) | To accurately measure impurity content [7] | Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, LOD, LOQ, Linearity, Range [7] | HPLC-UV/MS for related substances [7] |

| Impurity Tests (Limit Tests) | To ensure impurities are below a specified limit [7] | Specificity, LOD [7] | Heavy metals testing, residual solvents [7] |

| Assays | To quantify the major analyte or its potency [7] | Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, Linearity, Range [7] | HPLC assay for content, cell-based bioassays [7] |

Method Validation Parameters Across Procedure Types

The validation parameters required for each analytical procedure type vary according to its intended use and criticality. ICH Q2(R1) defines a set of characteristic parameters that must be validated to demonstrate procedure suitability.

Definition of Validation Parameters

- Specificity: The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [7] [9]. For identification tests, this is the critical parameter [7].

- Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between the value found and the value accepted as a true or reference value. It expresses the trueness of the method [9].

- Precision: The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions. It includes repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [9].

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range [9].

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity [9].

- Detection Limit (DL): The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified [9].

- Quantitation Limit (QL): The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy [9].

- Robustness: A measure of the procedure's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, indicating its reliability during normal usage [9].

Parameter Requirements by Procedure Type

Table 2: Validation Parameter Requirements by Analytical Procedure Type

| Validation Parameter | Identification | Impurity Tests (Quantitative) | Impurity Tests (Limit) | Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Yes [7] | Yes [7] | Yes [7] | Yes [7] |

| Accuracy | No | Yes [7] | No | Yes [7] |

| Precision | No | Yes [7] | No | Yes [7] |

| Linearity | No | Yes [7] | No | Yes [7] |

| Range | No | Yes [7] | No | Yes [7] |

| Detection Limit (DL) | No | No | Yes [7] | No |

| Quantitation Limit (QL) | No | Yes [7] | No | No |

Analytical Procedure Workflow and Lifecycle

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting, developing, and validating an analytical procedure based on the ICH Q2(R1) framework and its subsequent evolution toward a full lifecycle approach.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Procedures

The successful implementation of analytical procedures according to ICH Q2(R1) requires carefully selected reagents and materials to ensure reliability and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provides an authentic sample of the analyte with known identity and purity for comparison and calibration [7]. | Identification tests, assay calibration, impurity quantification [7]. |

| Critical Reagents | Specific binding reagents essential for the function of certain bioanalytical methods. | Antibodies for immunoassays, enzymes for enzymatic activity tests, cell lines for bioassays [7]. |

| Chromatographic Materials | Stationary phases and columns for separation sciences. | HPLC/UPLC columns for impurity profiling, assay content determination. |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Solvents, extraction buffers, dilution media, and derivatization agents. | Protein precipitation solvents, solid-phase extraction cartridges, dilution buffers for sample preparation. |

| System Suitability Solutions | Mixtures used to verify that the analytical system is operating correctly before sample analysis. | Resolution mixtures for chromatography, precision standards for injection repeatability. |

Regulatory Context and Evolution to ICH Q2(R2)

While ICH Q2(R1) remains the current implemented guideline in most regions, understanding its evolution provides valuable context for pharmaceutical analysts. The ICH has recently finalized Q2(R2) on "Validation of Analytical Procedures" and introduced Q14 on "Analytical Procedure Development" [11]. These updates reflect the increasing complexity of pharmaceutical products, particularly biologics, and the advancement of analytical technologies.

Key enhancements in Q2(R2) include:

- Formalization of a lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, advocating for continuous validation and assessment throughout the method's operational use [11].

- Enhanced method development principles incorporating Quality by Design (QbD) and defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) early in development [11] [12].

- Refinements to validation parameters, including explicit guidance for multivariate methods and non-linear responses [11] [10].

- Mandatory robustness testing integrated with the lifecycle approach [11].

For researchers conducting pharmaceutical residue analysis, these developments emphasize the importance of robust, well-developed methods from the outset, with validation parameters carefully selected based on the specific analytical question being addressed—whether it concerns identity, purity, or content.

The validation of analytical methods is a critical prerequisite in pharmaceutical research to ensure that the data generated is reliable and fit for its intended purpose. For residue analysis, which often involves quantifying trace levels of substances, demonstrating that a method is rigorously characterized is paramount. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline provides a foundational framework for this process, outlining the key parameters that must be evaluated. This guide focuses on four of these essential parameters—Specificity, Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), and Accuracy—by comparing different analytical approaches, detailing experimental protocols, and presenting objective performance data to inform method development and validation.

Specificity: Ensuring Analytical Selectivity

Specificity is the ability of an analytical method to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [13]. A specific method ensures that the signal measured is solely due to the target analyte.

Experimental Protocol for Demonstrating Specificity

To challenge the specificity of a method, a series of experiments should be performed [13]:

- Analyze a blank sample: The sample matrix (e.g., plasma, tissue homogenate) without the analyte should be analyzed to demonstrate the absence of interfering signals at the retention time of the analyte.

- Analyze a spiked sample: The sample matrix spiked with the analyte at a relevant concentration (e.g., the LOQ) should be analyzed to confirm the analyte's response.

- Challenge with potential interferents: The sample matrix should be spiked with the analyte and all potential interferents. These typically include:

- Degradation products (from forced degradation studies)

- Process impurities

- Excipients (for drug products)

- Other analytes that may be co-administered or co-extracted.

- Chromatographic examination: For chromatographic methods like HPLC, the resulting chromatograms are examined for baseline resolution. The method is considered specific if the analyte peak is unaffected by the presence of interferents and no significant interference is observed at the same retention time.

Limits of Detection (LOD) and Quantitation (LOQ): Defining Method Sensitivity

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest amount of analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under the stated experimental conditions. The Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) is the lowest amount of analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy [14] [13]. These parameters are crucial for residue methods where analytes are present at very low concentrations.

Comparison of Calculation Approaches

There is no universal protocol for determining LOD and LOQ, and different approaches can yield significantly different results [15] [16]. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline describes several methods, each with its own advantages and applications [13] [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Approaches for Determining LOD and LOQ

| Approach | Description | Typical Formula | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) [18] [19] | Measures the ratio of the analyte signal to the background noise. | LOD: S/N ≥ 2 or 3LOQ: S/N ≥ 10 | Simple, intuitive, and directly applicable to chromatographic methods. | Can be subjective; depends on how noise is measured; may not account for matrix effects. |

| Standard Deviation of the Blank [14] [19] | Based on the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the response from multiple blank samples. | LOB = Meanblank + 1.645*SDblankLOD = LOB + 1.645*SD_low concentration sample | Statistically rigorous; defined in CLSI EP17 guideline. | Requires a large number of replicates; a genuine analyte-free blank matrix can be difficult to obtain. |

| Calibration Curve: SD of Response & Slope [13] [17] | Uses the standard error of the regression (or y-intercept) and the slope of the calibration curve. | LOD = 3.3σ / SLOQ = 10σ / SWhere σ = standard deviation of response, S = slope | Scientifically robust; uses data from the calibration curve; does not require a separate blank. | Assumes the calibration curve is linear in the low-concentration range; the estimate of σ can vary. |

| Accuracy Profile [15] [18] | A graphical tool based on tolerance intervals that combines bias and precision to define the lowest level meeting accuracy criteria. | Based on β-content tolerance intervals | Provides a realistic and relevant assessment; considers total error. | More complex to compute and implement. |

| Visual Evaluation [13] [19] | The lowest concentration is determined by the analyst or instrument to be reliably detected or quantified. | Determined by logistic regression of binary (detect/non-detect) data. | Practical for non-instrumental methods (e.g., visual tests). | Subjective and highly variable between analysts. |

Experimental Data and Protocol for Calibration Curve Method

A practical example for calculating LOD and LOQ via the calibration curve method using HPLC is provided below [17].

- Procedure:

- Prepare a calibration curve with at least 5 concentrations in the range of the expected LOD/LOQ.

- Inject each calibration level and record the analyte response (e.g., peak area).

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the data (Concentration vs. Response) to obtain the slope (S) and the standard error of the regression (σ, or ( s_{y/x} )).

- Sample Calculation:

- From the regression output: Slope (S) = 1.9303, Standard Error (σ) = 0.4328.

- LOD = (3.3 × 0.4328) / 1.9303 = 0.74 ng/mL

- LOQ = (10 × 0.4328) / 1.9303 = 2.24 ng/mL [17]

- Validation: The calculated LOD and LOQ must be verified experimentally by preparing and analyzing multiple replicates (e.g., n=6) at these concentrations. The LOQ, in particular, should demonstrate an accuracy and precision (e.g., %CV) within ±20% [18].

Table 2: Comparison of LOD/LOQ Values for Different Drugs Using Various Methods [16]

| Analyte | Calculation Method | LOD | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Lowest Value | Lowest Value |

| Carbamazepine | Standard Deviation of Response (SDR) | Highest Value | Highest Value |

| Phenytoin | Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Lowest Value | Lowest Value |

| Phenytoin | Standard Deviation of Response (SDR) | Highest Value | Highest Value |

This table highlights that the choice of calculation method significantly influences the reported sensitivity of a method, underscoring the need to specify the approach used.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for determining and validating the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), incorporating common calculation methods and the essential step of experimental confirmation.

Accuracy: Establishing Trueness of Measurement

Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and the value accepted as a true or reference value. It is often reported as percent recovery of the known, spiked amount of analyte [13]. For residue methods, accuracy is typically assessed across the validated range, including the LOQ.

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Accuracy

The following protocol is standard for evaluating accuracy in bioanalytical methods:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of five replicates per concentration level. Accuracy should be evaluated at a minimum of three concentration levels (low, medium, and high) within the range of the method [13].

- Spiking: Spike the analyte of interest into the blank matrix (e.g., plasma) at the known concentrations.

- Analysis: Analyze the spiked samples using the validated method.

- Calculation: Calculate the mean measured concentration for each level and determine the accuracy as % Recovery:

- % Recovery = (Mean Measured Concentration / Nominal Spiked Concentration) × 100

- Acceptance Criteria: For bioanalytical methods, accuracy should be within ±15% of the nominal value, except at the LOQ, where it should be within ±20% [18].

Table 3: Example Accuracy and Precision Data for a Residue Method

| Nominal Concentration (ng/mL) | Mean Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Accuracy (% Recovery) | Precision (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 (LOQ) | 2.45 | 98.0% | 5.2% |

| 50.0 | 51.2 | 102.4% | 3.1% |

| 100.0 | 97.8 | 97.8% | 2.0% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials required for the development and validation of residue methods, particularly those based on HPLC.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | The analyte-free biological material (e.g., plasma, urine, tissue homogenate) used to prepare calibration standards and quality control samples. It is critical for assessing specificity and matrix effects [20]. |

| Reference Standard | A highly characterized substance of known purity and identity used to prepare the analyte stock and working solutions for spiking [13]. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | A compound added in a constant amount to all samples, blanks, and calibration standards to correct for variability during sample preparation and instrument analysis [15]. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, water) and buffers used to elute the analyte from the chromatographic column. |

| Sample Preparation Materials | Supplies for extraction and purification, such as solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, protein precipitation plates, and liquid-liquid extraction solvents. |

The validation of specificity, LOD, LOQ, and accuracy forms the cornerstone of a reliable analytical method for pharmaceutical residue analysis. As demonstrated, multiple approaches exist for determining LOD and LOQ, each with its own merits and limitations. The classical statistical methods can sometimes provide underestimated values, while more modern graphical tools like the accuracy or uncertainty profile offer a more realistic assessment by incorporating total error [15]. The choice of method should be justified and aligned with the regulatory guidelines and the intended use of the method. Ultimately, whichever parameters and calculation methods are selected, they must be supported by robust experimental data and rigorous validation protocols to ensure the method is truly fit for purpose.

For researchers and scientists in drug development, navigating the regulatory requirements of major health authorities is a critical component of bringing pharmaceutical products to market. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides a foundational framework through guidelines like ICH Q2(R1) on analytical method validation, which establishes harmonized standards for validating analytical procedures. These guidelines form the scientific and regulatory bedrock for ensuring that analytical methods used in pharmaceutical residue analysis are reliable, reproducible, and fit for their intended purpose [5].

While ICH guidelines create a platform for harmonization, regulatory authorities in different regions implement and enforce these standards with varying emphases and additional requirements. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) represent two of the most influential regulatory bodies whose compliance standards impact global drug development. Understanding their distinct approaches, particularly in areas such as Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP), inspection procedures, and the management of post-approval changes, is essential for successful regulatory strategy and global market access [21] [22].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the regulatory landscapes of the FDA and EMA, with a specific focus on requirements relevant to pharmaceutical residue analysis research. It is structured within the context of method validation according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, providing scientists with practical frameworks for compliance and operational excellence.

Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Regulatory Requirements

The following table summarizes the key regulatory aspects of the FDA and EMA relevant to pharmaceutical analysis and method validation.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Requirements Comparison for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Aspect | U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration) | EMA (European Medicines Agency) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Legal Framework | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; 21 CFR Parts 210 & 211 (CGMP) [21] | Directive 2001/83/EC; Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 [22] |

| GMP/GDP Regulations | Current Good Manufacturing Practice (CGMP) in 21 CFR 210, 211, and 212 [21] | EU GMP Guidelines; EudraGMDP database for certificates and non-compliance statements [22] |

| Guidance on Method Validation | Adheres to ICH Q2(R1) and Q2(R2); FDA guidance documents [5] | Adheres to ICH Q2(R1) and Q2(R2); EU GMP Annexes [22] |

| Approach to Inspections | Risk-based pre-approval and surveillance inspections; Domestic and international inspections [23] | Risk-based inspections by National Competent Authorities; Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) for non-EU sites [22] |

| Lifecycle Management | CFR 314.70 for post-approval changes; Emerging advanced manufacturing guidance (2025) [24] | EU Variations Guidelines (2025) with Types IA, IB, and II; PACMPs and PLCM documents [25] |

| Governance of Analytical Procedures | ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 on Analytical Procedure Lifecycle [5] | ICH Q2(R2) and Q14; Compilation of Union procedures for harmonization [22] |

Key Regulatory Concepts and Recent Developments

FDA's CGMP and Advanced Manufacturing: The FDA's CGMP regulations are the minimum requirements for ensuring drug quality. A January 2025 draft guidance clarifies considerations for in-process controls under 21 CFR 211.110, supporting the use of advanced manufacturing technologies like continuous manufacturing and real-time quality monitoring. The FDA encourages a scientific and risk-based approach for in-process sampling but currently advises that process models should be paired with physical testing, not used alone [24].

EMA's Variations System and Lifecycle Management: The EMA's updated Variations Guidelines, effective in 2025, introduce a more streamlined, predictable system for managing post-approval changes to medicines. The system is based on a risk-based classification (Type IA, IB, and II) and supports modern tools like Post-Approval Change Management Protocols (PACMPs) and Product Lifecycle Management (PLCM) documents. This facilitates faster implementation of changes, benefiting complex products like Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) [25].

Method Validation According to ICH Q2(R1) Guidelines

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline, "Validation of Analytical Procedures," provides a foundational framework for establishing that analytical methods are suitable for their intended purpose. For pharmaceutical residue analysis, this translates to demonstrating that the method can reliably detect, identify, and quantify residue levels in specific matrices [5] [6].

The core validation parameters mandated by ICH Q2(R1) and their relevance to residue analysis are detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Core ICH Q2(R1) Validation Parameters for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Application in Residue Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value. | Assessed by spiking the matrix with known analyte concentrations and measuring recovery [5]. |

| Precision | Degree of scatter among individual test results. Includes repeatability and intermediate precision. | Critical for ensuring consistent measurement of residue levels across different days, analysts, or equipment [5]. |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | Demonstrates the method can distinguish the residue from interfering matrix components, impurities, or degradation products [5]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected. | Important for establishing the method's sensitivity and the threshold for residue presence [5]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | Defines the lower limit of the quantitative range for the residue [5]. |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain test results proportional to analyte concentration. | Established across a range encompassing the expected residue levels [5]. |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity. | The validated range must cover all potential residue concentrations from the cleaning or manufacturing process [5]. |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Evaluates method reliability during normal use, e.g., small changes in pH, temperature, or mobile phase composition [5]. |

Experimental Protocol for a Validated Residue Analysis Method

The following workflow provides a generalized protocol for developing and validating an analytical method for pharmaceutical residue analysis, based on ICH Q2(R1) principles and the modernized ICH Q14 on Analytical Procedure Development [5].

Figure 1: Analytical Method Lifecycle Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages from defining the method's purpose to its ongoing management, aligning with modern ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines.

Title: Analytical Method Lifecycle Workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP): Before development, prospectively define the method's purpose and the required performance criteria for the residue analysis. This includes the analyte, matrix, required sensitivity (LOD/LOQ), and acceptable levels of accuracy and precision [5].

- Conduct Risk Assessments: Use a systematic, risk-based approach (as described in ICH Q9) to identify and prioritize potential variables that could impact method performance. This guides the robustness studies and informs the overall control strategy [5].

- Develop a Formal Validation Protocol: Create a detailed protocol that specifies the validation parameters to be tested (from Table 2), the experimental design, acceptance criteria (justified by the ATP and risk assessment), and sampling procedures [5].

- Execute the Validation Study: Perform laboratory experiments to collect data for each validation parameter as per the protocol. For residue analysis, this typically involves preparing samples by spiking the specific matrix (e.g., equipment surface swabs, manufacturing components) with known concentrations of the analyte.

- Document and Establish Control Strategy: Compile the data and report the outcome. Justify that the method is validated for its intended use. Define the control strategy, including system suitability tests and procedures for any future method changes [5].

- Lifecycle Management: Implement a procedure for managing post-approval changes to the method. The enhanced approach in ICH Q14 allows for more flexible management of changes through an established control strategy and continued monitoring [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful method validation and routine analysis require high-quality materials. The following table lists key research reagent solutions and their critical functions in pharmaceutical residue analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides a benchmark of known identity, purity, and strength to calibrate instruments, validate methods, and ensure accuracy [5]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used for sample preparation, dilution, and as mobile phase components in chromatography; purity is critical to prevent background interference. |

| Chromatographic Columns | The heart of separation (HPLC/UPLC, GC); critical for achieving specificity and resolving the analyte from matrix components [5]. |

| Sample Preparation Kits | (e.g., Solid-Phase Extraction, Filters) Isolate and concentrate the target residue from the complex sample matrix, improving sensitivity and accuracy. |

| System Suitability Test Solutions | A mixture of analytes used to verify that the chromatographic system is performing adequately at the time of testing, ensuring data integrity [5]. |

Navigating the regulatory landscape for pharmaceutical analysis requires a deep understanding of both the harmonized ICH guidelines and the specific implementations of regional authorities like the FDA and EMA. The core principles of ICH Q2(R1) provide the universal framework for demonstrating that an analytical method is valid and reliable. However, success in global drug development depends on appreciating the nuances of FDA's CGMPs, including their evolving stance on advanced manufacturing, and the EMA's centralized procedures and streamlined variation guidelines.

By integrating a modern, lifecycle approach to method validation—beginning with a clear ATP and supported by robust risk management—scientists can not only meet current regulatory expectations but also build a flexible foundation for continuous improvement. This ensures that pharmaceutical products, supported by rigorously validated analytical data, consistently meet the highest standards of quality, safety, and efficacy for patients worldwide.

Implementing ICH Q2(R1): A Step-by-Step Approach for Residue Methods

Analytical method validation serves as a critical foundation for ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility of data in pharmaceutical residue analysis research. This process provides documented evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, establishing a foundation of confidence in the results generated during drug development and quality control. For researchers and scientists working with pharmaceutical residues, a properly validated method ensures that trace-level analyses are scientifically sound and defensible, which is particularly important given the complex matrices and low concentration levels often involved.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," represents the internationally recognized standard for validating analytical methods. This guideline provides a comprehensive framework that harmonizes requirements across regulatory jurisdictions, ensuring that methods developed in one region will be accepted in others. The validation process under ICH Q2(R1) involves testing a series of performance characteristics to demonstrate that a method consistently produces results that meet predefined acceptance criteria, thereby confirming its fitness for the intended application in pharmaceutical analysis [9].

For the analysis of pharmaceutical residues, which often involves detecting and quantifying trace-level compounds in complex matrices, a rigorous validation protocol is not merely a regulatory formality but a scientific necessity. This article provides a structured comparison of validation approaches according to IICH Q2(R1) guidelines, offering researchers a framework for developing robust validation protocols with clearly defined scope and acceptance criteria tailored to pharmaceutical residue analysis.

Core Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria According to ICH Q2(R1)

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline defines eight key validation characteristics that collectively demonstrate an analytical method's suitability for its intended purpose. For pharmaceutical residue analysis, each parameter must be carefully evaluated with acceptance criteria that reflect the method's specific application, whether for identity testing, assay, impurity quantification, or limit testing.

Specificity is the ability of a method to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix. For pharmaceutical residue analysis, this parameter is crucial as it demonstrates that the method can distinguish and quantify the target residue without interference from excipients, degradation products, or matrix components. Specificity is typically established by comparing chromatograms or spectra of blank matrices with those spiked with the target analyte, demonstrating baseline separation from potential interferents [26] [27].

Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value. For quantitative methods in residue analysis, accuracy is typically expressed as percent recovery of known amounts of analyte spiked into the matrix. ICH Q2(R1) recommends establishing accuracy across the method's range using a minimum of nine determinations over at least three concentration levels (e.g., three concentrations with three replicates each). Acceptance criteria for accuracy in pharmaceutical analysis generally require mean recovery between 80-120% for impurity methods and 98-102% for assay methods, though these ranges may be justified based on the analytical technique and analyte concentration [27].

Precision encompasses both repeatability (intra-assay precision) and intermediate precision (inter-assay precision). Repeatability expresses the precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time, typically demonstrated through multiple measurements of homogeneous samples. Intermediate precision examines the influence of variations such as different analysts, equipment, or days on analytical results. For residue analysis methods, precision is usually expressed as the relative standard deviation (%RSD) of multiple measurements. Acceptance criteria typically require RSD values below 2% for assay methods of drug substances and below 15% for impurity quantification, though these limits must be scientifically justified based on the method's intended use [27].

Detection Limit (DL) and Quantitation Limit (QL) are critical parameters for residue analysis, where trace-level detection is often required. The DL represents the lowest concentration of analyte that can be detected but not necessarily quantified, while the QL is the lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. These limits can be determined based on visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio (typically 3:1 for DL and 10:1 for QL), or the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [27].

Linearity demonstrates the ability of the method to produce results that are directly proportional to analyte concentration within a specified range. Linearity is typically established by preparing and analyzing a series of standard solutions at different concentration levels, then evaluating the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line. For chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis, correlation coefficients (r) of ≥0.999 are generally expected for assay methods, while r≥0.995 may be acceptable for impurity methods [27].

Range defines the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which the method has suitable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity. The appropriate range depends on the method's application, with typical recommendations being 80-120% of the target concentration for assay methods, and from the reporting threshold to 120% of the specification for impurity methods [27] [10].

Robustness evaluates the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, such as pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, or flow rate in chromatographic methods. Robustness testing helps identify critical parameters that must be closely controlled during method execution and establishes system suitability criteria to ensure method performance [27].

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Approach | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Compare analyte response in presence of potentially interfering compounds | No interference observed; baseline separation |

| Accuracy | Spike recovery studies at multiple levels | Recovery 80-120% (impurities); 98-102% (assay) |

| Precision | Multiple measurements of homogeneous samples | RSD <2% (assay); <15% (impurities) |

| Linearity | Analyze minimum of 5 concentration levels | Correlation coefficient r ≥ 0.999 (assay); r ≥ 0.995 (impurities) |

| Range | Establish interval where validation parameters are acceptable | 80-120% of test concentration (assay); QL to 120% of spec (impurities) |

| Detection Limit | Signal-to-noise ratio or statistical approach | S/N ≥ 3:1 |

| Quantitation Limit | Signal-to-noise ratio or statistical approach | S/N ≥ 10:1; Accuracy and precision as defined |

Comparative Analysis of ICH Q2(R1) with Other Regulatory Frameworks

While ICH Q2(R1) serves as the international benchmark for analytical method validation, various regional pharmacopeias and regulatory bodies have established their own guidelines with subtle but important differences. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for researchers developing methods intended for global regulatory submissions or comparing performance across different regulatory frameworks.

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) provides guidance on analytical method validation in General Chapter <1225>, which aligns closely with ICH Q2(R1) but includes terminology differences, such as the use of "ruggedness" instead of "intermediate precision." USP places greater emphasis on system suitability testing (SST) as a prerequisite for method validation and provides more practical examples tailored to compendial methods. For pharmaceutical residue analysis, this focus on system suitability ensures that the analytical system is functioning correctly at the time of analysis, which is particularly important for methods analyzing trace-level compounds where system performance directly impacts data quality [9].

The Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) outlines validation requirements in General Information Chapter 17, which closely follows ICH Q2(R1) but with a stronger emphasis on robustness and system suitability testing. JP guidelines may be more prescriptive in certain areas, reflecting Japan's regulatory environment, and may require additional documentation to meet Japanese regulatory standards. For researchers developing methods for pharmaceutical residue analysis that might be submitted in Japan, this heightened focus on robustness warrants additional experimental designs to test method performance under varied conditions [9].

The European Union (EU) guidelines incorporate ICH Q2(R1) into the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) through General Chapter 5.15. While fully adopting ICH principles, the EU provides supplementary guidance for specific analytical techniques, such as chromatography and spectroscopy, and places strong emphasis on robustness testing, particularly for methods used in stability studies. For pharmaceutical residue analysis, this emphasis ensures that methods remain reliable when transferred between laboratories or when slight variations in analytical conditions occur [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Regional Guidelines Based on ICH Q2(R1)

| Regulatory Body | Key Guidance Document | Alignment with ICH Q2(R1) | Unique Emphases |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICH | Q2(R1): Validation of Analytical Procedures | Foundation document | Science- and risk-based approach; global harmonization |

| USP | General Chapter <1225> | Highly aligned | Terminology differences ("ruggedness"); emphasis on system suitability testing |

| JP | General Information Chapter 17 | Highly aligned | Strong emphasis on robustness; may require additional documentation |

| EU | Ph. Eur. General Chapter 5.15 | Fully adopted | Supplementary guidance for specific techniques; emphasis on robustness |

Despite these regional variations, the core principles of ICH Q2(R1) remain the foundation for all major guidelines, ensuring a high degree of global harmonization. All guidelines emphasize the importance of accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range, detection limit, quantitation limit, and robustness, and all adopt a risk-based approach that allows for flexibility in validation extent based on the method's intended use [9].

For researchers developing validation protocols for pharmaceutical residue analysis, this harmonization means that a well-designed protocol based on ICH Q2(R1) will generally satisfy the core requirements of other regions, though attention should be paid to specific additional expectations based on the target regulatory markets.

Experimental Design and Protocol Development

Developing a robust validation protocol requires careful planning of experimental designs for each validation parameter. The protocol should clearly define the scope of validation, including the type of method (identification, quantitative impurity testing, limit testing, or assay), the analytical technique, and the specific conditions under which the method will be applied.

For accuracy evaluation in pharmaceutical residue analysis, a typical experiment involves preparing a minimum of nine determinations over at least three concentration levels covering the specified range. For example, for an impurity method, this might include preparations at 50%, 100%, and 150% of the specification level. Each preparation is analyzed, and the recovery is calculated by comparing the measured value to the known spiked value. The results should meet predefined acceptance criteria for accuracy, typically expressed as percent recovery, with tighter limits for assay methods (e.g., 98-102%) and wider but justified limits for impurity methods (e.g., 80-120%) [27].

Precision assessment encompasses both repeatability and intermediate precision. Repeatability is demonstrated by analyzing a minimum of six independent preparations at 100% of the test concentration or multiple determinations at three different concentrations (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120%) covering the specified range. Intermediate precision is evaluated by having different analysts perform the analysis on different days using different instruments, when possible. The precision is expressed as the relative standard deviation (%RSD) of the results, with acceptance criteria typically set at ≤2% for assay methods and ≤15% for impurity methods, though these should be justified based on the analytical requirements [27].

Linearity and range are typically established by preparing a series of standard solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels, ideally evenly spaced across the specified range. The results are plotted as analyte response versus concentration, and statistical calculations are performed to determine the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line. The range is derived from the linearity data and represents the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels where the method demonstrates acceptable linearity, accuracy, and precision [27] [10].

Specificity for pharmaceutical residue analysis methods is demonstrated by showing that the method can unequivocally identify and quantify the analyte in the presence of other components that might be present in the sample matrix. This is typically achieved by analyzing blank matrices, matrices spiked with the target analyte, and matrices spiked with potential interferents. For stability-indicating methods, specificity should include demonstration of separation from degradation products generated under stress conditions (e.g., acid, base, oxidation, heat, and light) [27].

Robustness testing involves deliberate variations of method parameters to identify critical factors that affect method performance. For a chromatographic method, this might include variations in flow rate (±10%), mobile phase composition (±2% absolute for organic modifier), column temperature (±5°C), pH (±0.2 units), and detection wavelength (±3 nm). The results of robustness testing inform the system suitability criteria and help define the controlled parameters in the final method [27].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic approach to developing a comprehensive validation protocol:

Validation Protocol Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a validation protocol requires carefully selected reagents, reference standards, and analytical materials. The following table outlines essential components for validating methods in pharmaceutical residue analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Functional Role | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provide traceable quantification and method calibration | System suitability testing; preparation of calibration curves; accuracy studies |

| High-Purity Solvents | Serve as mobile phase components and sample diluents | HPLC mobile phases; sample preparation; extraction procedures |

| Characterized Matrix Blanks | Enable specificity demonstration and background interference assessment | Selectivity studies; accuracy/recovery determinations |

| System Suitability Solutions | Verify chromatographic system performance before analysis | Resolution, efficiency, and reproducibility checks |

| Stable Derivatization Reagents | Enhance detection sensitivity for trace-level analysis | Pre-column or post-column derivatization for improved detection |

Developing a comprehensive validation protocol with clearly defined scope and acceptance criteria is fundamental to establishing reliable analytical methods for pharmaceutical residue analysis. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides an internationally harmonized framework for this process, with specific parameters that must be evaluated based on the method's intended purpose. While regional variations exist in implementation through USP, JP, and EU guidelines, the core principles remain consistent, ensuring that validated methods generate scientifically sound and defensible data.

For researchers and drug development professionals, a well-designed validation protocol serves not only as a regulatory requirement but as a scientific demonstration of method reliability. By systematically addressing each validation parameter with appropriate experimental designs and scientifically justified acceptance criteria, analysts can ensure the generation of high-quality data that supports the safety and efficacy assessment of pharmaceutical products. As analytical technologies continue to evolve, the fundamental principles of ICH Q2(R1) remain relevant, providing a stable foundation for method validation while allowing sufficient flexibility to accommodate technological advancements in pharmaceutical analysis.

Within the framework of ICH Q2(R1) validation guidelines, establishing the specificity of an analytical method is paramount to ensuring the accurate and reliable assessment of a drug's identity, potency, and purity throughout its shelf life. For methods detecting pharmaceutical residues and impurities, two experimental approaches stand as critical pillars: forced degradation studies and peak purity assessment. Forced degradation proactively generates potential impurities, while peak purity assessment ensures the analytical procedure can detect and resolve them. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and emerging techniques within these domains, providing a structured evaluation of their capabilities in delivering the specificity required for robust method validation.

Forced Degradation Studies: A Proactive Approach to Stability

Forced degradation studies are an essential, proactive exercise that subjects a drug substance or product to exaggerated stress conditions. The primary objective is to elucidate potential degradation pathways, identify degradation products, and, most critically, demonstrate that the analytical method can reliably separate and quantify the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from its degradation products—thus proving its stability-indicating property [28] [29].

Core Stress Conditions and Experimental Protocols

A comprehensive forced degradation study investigates a molecule's vulnerabilities across a range of conditions. The table below summarizes the standard stress conditions, their implementations, and the typical degradation reactions they induce [28] [29] [30].

Table 1: Standard Forced Degradation Stress Conditions and Methodologies

| Stress Condition | Experimental Protocol | Common Degradation Pathways | Key Method Development Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic Hydrolysis | Exposure to strong mineral acids (e.g., 0.1-1 M HCl) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 40-80°C) for specified durations [28]. | Cleavage of esters, lactones, acetals, and some amides [28]. | Informs formulation strategy for drugs exposed to stomach acid [28]. |

| Basic Hydrolysis | Exposure to strong bases (e.g., 0.1-1 M NaOH) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 40-80°C) for specified durations [28]. | Degradation of esters, amides, lactones, and carbamates; possible β-elimination [28]. | Reveals sensitivity to alkaline environments or basic excipients [28]. |

| Oxidative Degradation | Treatment with oxidizing agents such as hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 0.1-3%) or radical initiators like AIBN (azobisisobutyronitrile) [28]. | Oxidation of electron-rich groups (phenols, amines, sulfides); N-oxide formation [28]. | Identifies oxidative hotspots; guides antioxidant selection in formulation [28]. |

| Thermal Degradation | Exposure to elevated temperatures (e.g., 70-100°C) in solid state or solution for days to weeks [28] [29]. | Decarboxylation, deamination, cyclization, and rearrangement [28]. | Simulates long-term storage in hot climates; informs packaging needs [28]. |

| Photolytic Degradation | Exposure to UV (320-400 nm) and visible light per ICH Q1B guidelines to simulate sunlight [28] [29]. | Bond cleavage, isomerization, ring rearrangement [28]. | Critical for identifying light-sensitive APIs and selecting protective packaging [28]. |

| Humidity Stress | Exposure to high-humidity conditions (e.g., 75-85% relative humidity) at elevated temperatures [28]. | Hydrolysis, recrystallization of amorphous forms, Maillard reactions [28]. | Assesses need for desiccants and moisture-barrier packaging [28]. |

The general workflow for executing and interpreting forced degradation studies is systematic, as illustrated below.

Diagram 1: Forced Degradation Workflow

Performance Comparison: Small Molecules vs. Biologics

The execution and focus of forced degradation studies differ significantly between small molecule drugs and complex biologics, impacting the choice of analytical techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of Forced Degradation Approaches

| Aspect | Small Molecule Drugs | Biologics (Proteins) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Degradation Pathways | Hydrolysis, oxidation, photolysis [28]. | Aggregation, deamidation, oxidation, fragmentation, disulfide scrambling [29] [31]. |

| Key Analytical Techniques | Reversed-Phase HPLC with DAD/MS [28]. | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEC), Peptide Mapping, Capillary Electrophoresis (CE-SDS) [29] [31]. |

| Extent of Degradation | Typically 5-15% degradation is considered adequate for method validation [29]. | No fixed percentage; aim is to generate meaningful degradants to challenge methods; aggregation levels of 10-15% may be sufficient [29]. |

| Regulatory Focus | ICH Q1A(R2), Q1B, Q2(R1) [30]. | ICH Q1B, Q2(R1), Q5C, Q6B; case-by-case approach is common [29] [31]. |

| Major Challenge | Ensuring method resolves all degradants from the main peak [28]. | Characterizing a wide variety of heterogeneous variants and complex higher-order structure changes [31]. |

Peak Purity Assessment: Ensuring Chromatographic Resolution

Peak purity assessment is the practice of verifying that a chromatographic peak corresponds to a single chemical entity, free from co-eluting impurities. This is a direct measure of an analytical method's specificity [32] [33].

Established Techniques and Emerging Solutions

The pharmaceutical industry relies on several techniques for peak purity assessment, each with distinct strengths and limitations.

Table 3: Comparison of Peak Purity Assessment Techniques

| Technique | Principle of Operation | Performance Data & Capabilities | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diode Array Detector (DAD) | Compares UV spectra across a chromatographic peak; spectral similarity is calculated via vector comparison or correlation coefficient [32]. | Detects impurities with dissimilar UV spectra; commercial software provides purity indices (e.g., spectral contrast angle, r²) [32]. | Cannot detect impurities with nearly identical UV spectra (e.g., isomers); low-level impurities may be missed [32] [33]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Detects co-eluting substances based on differences in mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [34] [33]. | High sensitivity and specificity; can provide structural identity via MS/MS [34]. | Cannot differentiate isomers with identical m/z; signal suppression can mask low-level impurities [34] [33]. |

| Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography (2D-LC) | Heart-cuts a peak from the 1st dimension and re-chromatographs it in a 2nd dimension with orthogonal separation mechanism [34] [33]. | High resolving power; can separate structurally similar impurities and isomers missed by DAD/MS. A study successfully separated API/impurity mixtures in all 10 test cases [33]. | Method development is complex; requires sophisticated instrumentation; longer analysis times [34]. |

The logical relationship for selecting a peak purity technique based on analytical needs is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Peak Purity Technique Selection

Experimental Protocol: A Standardized 2D-LC Screening Platform for Peak Purity

Recent advancements have led to the development of standardized 2D-LC screening platforms for peak purity, designed to overcome the limitations of DAD and MS [33]. The following protocol provides a general framework.

Objective: To detect co-eluting impurities, including isomers, that are not discernible by DAD or MS. Instrumentation: A 2D-LC system equipped with a switching valve, two pumps, and DAD detection. A ten-port, five-position valve with active solvent modulation (ASM) is recommended [33]. Procedure:

- First Dimension (¹D): The sample is analyzed using the existing 1D method (e.g., C18 column, specific mobile phase and gradient) [33].

- Peak Heart-Cutting: Multiple narrow segments ("heart-cuts") are taken across the width of the target API peak as it elutes from the ¹D column [33].

- Transfer and Modulation: Each heart-cut is transferred to a sample loop and then to the ²D column. ASM is used to reduce the strength of the incoming ¹D eluent, focusing the analytes at the head of the ²D column [33].

- Second Dimension (²D) Separation: The trapped analytes are separated using a fast, orthogonal gradient. To maximize orthogonality while staying in reversed-phase mode, the ²D employs a different stationary phase (e.g., C8, PFP, phenyl-hexyl, HILIC) and/or a different mobile phase pH than the ¹D [34] [33].

- Detection and Analysis: The ²D effluent is monitored by DAD (and optionally MS). A pure ¹D peak will yield a single peak in the ²D, while an impure peak will show multiple resolved peaks [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents critical for conducting high-quality forced degradation and peak purity studies.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Specificity Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stress Reagents | To induce specific degradation pathways for method validation [28] [30]. | Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂). Concentrations typically 0.1-1.0 M [28]. |

| MS-Compatible Mobile Phase Additives | To facilitate LC-MS analysis and 2D-LC-MS peak purity assessment without ion suppression [34]. | Formic Acid, Ammonium Acetate, Ammonium Hydroxide. Preferable to non-volatile additives like TFA and phosphates for MS work [34]. |

| Orthogonal HPLC Columns | To achieve separation of structurally similar impurities and isomers in 2D-LC peak purity analysis [34] [33]. | A screening set for the 2nd dimension may include C18, C8, PFP, Phenyl-Hexyl, Biphenyl, HILIC, and Cyano columns to maximize orthogonality [33]. |

| Photostability Chamber | To conduct controlled photodegradation studies in compliance with ICH Q1B [30]. | Must produce combined visible and ultraviolet (UV, 320-400 nm) output. Exposure levels must be justified and documented [29] [30]. |

Forced degradation studies and peak purity assessment are not merely regulatory checkboxes but are fundamental to developing robust, stability-indicating methods. While traditional techniques like DAD and MS are powerful, the emerging data confirms that 2D-LC provides a superior level of assurance for detecting co-elutions, particularly for challenging impurities like isomers. The choice of technique should be guided by the molecule's complexity and the criticality of the method. A holistic strategy, integrating proactive forced degradation with orthogonal peak purity analysis, delivers the specificity required by ICH Q2(R1) and, ultimately, ensures patient safety and drug product efficacy.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of swab and rinse sampling procedures for cleaning validation in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Recovery studies are central to demonstrating that an analytical method can accurately and precisely detect residue on manufacturing equipment. Framed within the requirements of the ICH Q2(R1) validation guideline, this article details experimental protocols, presents quantitative recovery data, and outlines the critical parameters for designing a study that ensures reliable measurement of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) residues [35].

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, cleaning validation is mandated by cGMP and FDA regulations to prevent cross-contamination and ensure drug product safety [35]. It demonstrates that a cleaning process consistently removes product and process residues from equipment. A pivotal component of validation is the recovery study, which qualifies the sampling and analytical methods used to detect residues. It confirms that the method accurately (closeness to the true value) and precisely (closeness of repeated measurements) recovers a known amount of analyte spiked onto a surface [36]. The data generated must provide confidence that the residue levels measured during routine monitoring are a true reflection of the cleanliness of the equipment.

Experimental Design for Recovery Studies

A well-designed recovery study investigates the major parameters that influence the efficiency of residue recovery from product contact surfaces.

Key Experimental Parameters

The following parameters should be systematically evaluated [35]:

- Sampling Method: A direct comparison between swab and rinse sampling.

- Surface Material: Representative coupons (e.g., Stainless Steel, PVC, Plexiglas) of equipment surfaces.

- Swab Characteristics: Material, texture, and releasability of fibers.

- Solvent and Extraction: Choice of solvent for wetting the swab and for extracting the analyte from the swab and surface.

- Spiking Technique: Including the concentration of the spike solution and allowing it to dry to simulate process conditions.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol, adapted from a published study on Chlordiazepoxide, provides a template for a robust recovery investigation [35]:

- Surface Preparation: Clean surface coupons (e.g., 5cm x 5cm) of Stainless Steel, PVC, and Polyester via ultrasonication in water, rinsing with purified water, and drying.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock standard solution of the target analyte (API) in an appropriate solvent. Dilute to create spiking and standard solutions at known concentrations.

- Surface Spiking: Spike a known volume of standard solution onto a defined area of the surface coupon. Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature.

- Swab Sampling:

- Use a validated swab type (e.g., Alpha swabs, Texwipe).

- Wet the first swab with a specified solvent (e.g., purified water).

- Swab the surface systematically: wipe horizontally with one side, flip the swab, and wipe vertically.

- Use a second, dry swab to repeat the process on the same area.

- Place both swabs in a test tube and add extraction solvent (e.g., Methanol and water mix).

- Hand-shake for approximately 2 minutes to desorb the analyte.

- Rinse Sampling:

- After spiking and drying, rinse the surface with a defined volume of rinse solvent (e.g., purified water or a solvent mix).

- Shake the surface in the solvent for approximately 5 minutes to extract the residue.

- Collect the rinse solvent for analysis.

- Analysis by HPLC:

- Instrument: HPLC system with UV-VIS detector.

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 250mm x 4.6mm, 5µm).

- Mobile Phase: Isocratic elution with a mix of methanol and water (60:40).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection: UV at 254 nm.

- Injection Volume: 5 µL.

The entire process, from sampling to analysis, can be visualized in the following workflow:

Comparative Performance Data: Swab vs. Rinse Sampling