Advanced Catalytic Remediation for Air Pollution Control: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced catalytic remediation technologies for air pollution control, tailored for researchers and scientists.

Advanced Catalytic Remediation for Air Pollution Control: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced catalytic remediation technologies for air pollution control, tailored for researchers and scientists. It explores the fundamental principles of environmental catalysis, from nanostructured single-atom catalysts to novel concepts like 'Environmental Catalytic Cities.' The scope includes a detailed examination of methodological applications such as Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) and catalytic thermal oxidation, alongside critical troubleshooting frameworks for catalyst deactivation, regeneration, and management of spent materials. Further, it covers validation protocols and comparative performance assessments of emerging technologies, including material-microbe hybrids and polymer nanocomposites. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge innovations and regulatory considerations, this review serves as a strategic resource for developing next-generation, efficient, and sustainable air purification systems.

The Science of Clean Air: Core Principles and Frontiers in Air Pollution Catalysis

Environmental catalysis encompasses catalytic technologies designed to reduce emissions of environmentally unacceptable compounds and develop sustainable chemical processes. [1] This field has grown from a niche specialty to a major driver of advances across the entire catalysis landscape, now accounting for approximately one-third of the worldwide catalyst market. [1] The historical focus of environmental catalysis was primarily on conventional cleanup technologies such as NOx removal from stationary and mobile sources, sulfur compound conversion, and volatile organic compound (VOC) abatement. [1] [2] Over the past two decades, however, the scope has expanded significantly to address broader environmental challenges, including liquid and solid waste treatment, greenhouse gas control, indoor air quality improvement, and the development of eco-compatible industrial processes. [1]

A key differentiator of environmental catalysis from other catalysis fields is the necessity to develop technologies that operate efficiently at conditions defined by upstream units, rather than optimizing reaction conditions for maximum conversion or selectivity as in traditional chemical processes. [1] This constraint has driven substantial innovation in catalyst design and implementation. Environmental catalysis now finds applications across an extraordinarily diverse range of domains, from traditional refinery and chemical production to emerging areas such as energy-efficient technologies, user-friendly applications, and reduction of the environmental impact associated with catalysts themselves. [1]

Historical Development and Expanding Applications

Traditional Foundations and Paradigm Shifts

The foundations of environmental catalysis were laid with the development of catalytic converters for automotive emissions control, which represented one of the first massive uses of catalysis outside traditional chemical and refinery production. [1] This application significantly contributed to public awareness of catalysis's benefits for environmental quality and life improvement. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, scientific interest progressively expanded from this cleanup-focused approach to broader applications aligned with sustainability principles. [1]

Three main driving forces have catalyzed renewed research activity in catalytic cleanup technologies: (1) the need to expand catalytic technologies from gaseous emissions to liquid emissions and solid waste treatment; (2) the demand for new post-treatment devices for mobile sources; and (3) the necessity of reconsidering post-treatment technologies from a systems integration perspective. [1] This evolution reflects a significant shift in how researchers approach environmental catalysis, moving from end-of-pipe solutions to integrated, preventive approaches.

Quantitative Comparison of Catalytic Systems

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Iron and Cobalt Fischer-Tropsch Catalysts

| Parameter | Iron-based Catalysts | Cobalt-based Catalysts |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Activity (TOF) | Baseline | 2.5 times higher than Fe |

| Typical Operating Temperature | 220-350°C | 200-240°C |

| H₂/CO Ratio Preference | 0.67-2.0 (CO-rich) | 1.2-2.0 (H₂-rich) |

| Water-Gas Shift Activity | High | Low |

| Methane Selectivity | Lower | Higher |

| CO₂ Selectivity | Higher | Lower |

| Olefin Content | Higher | Lower |

| H₂S Poisoning Threshold | 25-50 ppb | 25-50 ppb |

| NH₃ Poisoning Threshold | 80 ppm | 45 ppb |

| Cost Considerations | Less expensive | More expensive |

The quantitative comparison between iron and cobalt catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis illustrates how different catalytic systems are optimized for specific environmental and process applications. [3] While cobalt catalysts demonstrate higher activity under clean conditions, iron catalysts offer advantages in CO-rich environments and exhibit greater resistance to ammonia poisoning. [3] This comparative analysis highlights the importance of selecting catalyst materials based on specific process conditions and potential contaminants in the feed stream.

Modern Research Frontiers and Grand Challenges

Advanced Catalyst Architectures

Recent years have witnessed remarkable advances in catalyst design, particularly with the emergence of single-atom catalysts (SACs) and double-atom catalysts (DACs). SACs feature isolated metal atoms dispersed on support surfaces, achieving nearly 100% atomic utilization efficiency and unique electronic structures that often enhance catalytic performance. [4] These materials represent a bridge between heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis, offering unprecedented opportunities for environmental applications.

DACs represent a further evolution, featuring paired metal atoms that work synergistically to overcome fundamental limitations of single-atom systems. [4] The advantages of DACs primarily stem from four effects:

- Adsorption effect: Modified adsorption/desorption behavior of reactants and intermediates

- Electronic effect: Tunable electronic structure through metal-metal interactions

- Bifunctional effect: Complementary functions at different active sites

- Electronic metal-support interaction: Enhanced catalyst-support synergism [4]

Table 2: Environmental Applications of Double-Atom Catalysts

| Application Area | Target Pollutants/Processes | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Wastewater Treatment | Organic contaminants, halogenated compounds, nitrate | Simultaneous activation of multiple oxidants, enhanced electron transfer |

| Air Purification | VOCs, CO, NOx, ozone | Balanced adsorption energy for different pollutants, optimized reaction pathways |

| Plastic Conversion | Polyolefins, waste polymers | Tuned activation energy for C-C bond cleavage, selective product formation |

| CO₂ Reduction | Carbon dioxide to value-added products | Moderate binding energy for *COOH and *CO intermediates |

| Fuel Desulfurization | Sulfur compounds in fuels | Specific metal-sulfur interactions, resistance to poisoning |

| Disinfection | Pathogenic microorganisms | Reactive oxygen species generation, membrane disruption capabilities |

The development of these advanced catalytic architectures has been facilitated by sophisticated characterization techniques. For instance, researchers have combined high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy with deep learning and density functional theory calculations to determine with statistical significance the exact location and coordination environment of Pd single-atoms supported on MgO nanoplates. [5] This approach revealed preferential interaction of Pd single-atoms with cationic vacancies, followed by occupation of anionic defects on the {001} MgO surface. [5]

Emerging Concepts and Systems Approaches

Beyond novel materials, environmental catalysis is evolving toward integrated systems approaches. One particularly visionary concept is the "Environmental Catalytic City" paradigm, which proposes the direct purification of low-concentration urban air pollutants in the atmosphere through catalytic materials coated on artificial surfaces such as building walls, roads, and vehicle radiators. [6] [7] This approach would essentially give cities self-purification capabilities without additional energy consumption, representing a transformative shift from point-source treatment to distributed environmental remediation.

The Environmental Catalytic City concept leverages both photocatalysis and ambient non-photocatalytic approaches. [6] [7] Photocatalysis utilizes light-induced electron-hole pairs to initiate redox reactions that degrade pollutants, while ambient catalysis operates without light activation using materials such as TiO₂-supported noble metals or NiFe-layered double hydroxides for formaldehyde and ozone removal respectively. [6] Implementation of this concept requires developing stable, efficient, and low-cost catalysts that can withstand outdoor environmental conditions while maintaining high activity for pollutant removal.

Experimental Protocols in Environmental Catalysis Research

Synthesis and Characterization of Single-Atom Catalysts

Protocol: Preparation of Pd Single-Atom Catalysts on MgO Support

Objective: To synthesize and characterize well-defined Pd single-atom catalysts on high-surface-area MgO support for environmental applications.

Materials:

- Commercial MgO precursor

- Palladium precursor (e.g., Pd(NO₃)₂)

- Deionized water

- H₂/He mixture (5% H₂)

- High-pressure hydrothermal reactor

Procedure:

- Support Preparation: Transform commercial MgO into Mg(OH)₂ via hydrothermal method at elevated temperature and pressure.

- Thermal Treatment: Calcinate the resulting Mg(OH)₂ in H₂/He mixture (5% H₂) at 900°C for 6 hours to obtain MgO nanoplates with plate-like morphology.

- Metal Deposition: Apply wet impregnation technique using Pd(NO₃)₂ solution to deposit Pd species on MgO support.

- Activation: Apply appropriate thermal treatment to achieve atomically dispersed Pd species.

Characterization Techniques:

- High-Resolution HAADF-STEM: Perform aberration-corrected imaging to directly visualize single metal atoms.

- Deep Learning Analysis: Apply convolutional neural networks (CNN) for automated analysis of large datasets of STEM images to determine metal location with statistical significance.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Calculate electronic structure and binding energies to interpret experimental observations.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Determine oxidation states of metal centers.

- BET Surface Area Analysis: Measure specific surface area and pore structure. [5]

Assessment of Catalytic Performance for Air Pollution Control

Protocol: Evaluation of Photocatalytic Materials for NOx Abatement

Objective: To quantitatively assess the performance of photocatalytic materials for nitrogen oxides removal under simulated atmospheric conditions.

Materials:

- Photocatalytic material (e.g., TiO₂-based catalyst)

- NOx gas mixture (standard concentration)

- Continuous flow reactor with optical window

- Light source simulating solar spectrum (AM 1.5)

- NOx analyzer (chemiluminescence detection)

- Controlled humidity generation system

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Place photocatalytic material in flow reactor with defined geometry and surface area.

- Conditioning: Pre-treat catalyst under reaction conditions until stable performance is observed.

- Dark Activity Measurement: Measure NOx conversion in absence of light to establish baseline.

- Photocatalytic Testing: Expose catalyst to light source while maintaining controlled flow of NOx mixture.

- Parameter Variation: Systematically vary conditions including light intensity, relative humidity, NOx concentration, and flow rate.

- Long-Term Stability: Conduct extended duration tests to assess deactivation behavior.

Analysis Methods:

- Conversion Calculation: Determine NO to NO₂ conversion and total NOx removal efficiency.

- Product Identification: Monitor formation of reaction products (e.g., nitrate species).

- Quantum Yield Assessment: Calculate apparent quantum efficiency based on photon flux and reaction rate.

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine reaction rate constants and dependence on operating parameters. [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Catalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Atom Catalysts | Maximum atom efficiency, well-defined active sites | Pd/MgO, Pt/FeOx, Pt/TiO₂ | High metal dispersion, tailored coordination environment |

| Double-Atom Catalysts | Overcoming scaling relationship limitations | Pt-Ru/C₃N₄, Fe-Co/graphene | Synergistic effects, dual active sites |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks | Precursors for atomically dispersed catalysts; catalytic supports | ZIF-8, MIL-series, UiO-66 | High surface area, tunable porosity, structural diversity |

| Photocatalytic Materials | Light-driven pollutant degradation | TiO₂, g-C₃N₄, Bi-based compounds | Appropriate band gap, charge separation efficiency |

| Layered Double Hydroxides | Ambient temperature catalysis | NiFe-LDH, MgAl-LDH | Tunable composition, redox properties |

| Advanced Characterization Probes | Atomic-scale structure determination | HAADF-STEM, XAS, EPR | Spatial resolution, chemical sensitivity, in situ capability |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Environmental catalysis continues to evolve rapidly, driven by both scientific innovation and pressing environmental challenges. Several key trends are likely to shape future research directions:

First, the integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with catalyst discovery and optimization represents a paradigm shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches. [8] ML potentials can now simulate systems with thousands of atoms over nanoseconds with accuracy approaching density functional theory, enabling rapid screening of candidate materials and prediction of performance under realistic conditions. [8]

Second, the push to replace precious metals with earth-abundant alternatives continues to gain momentum. [8] Photocatalysis using non-precious materials such as iron-based systems for chemical transformations previously requiring ruthenium or other precious metals demonstrates the potential for more sustainable and economically viable catalytic technologies. [8]

Third, computational and theoretical methods are playing an increasingly central role in environmental catalysis. [9] These approaches enable researchers to model catalytic mechanisms, establish structure-property relationships, simulate reaction kinetics and dynamics, and develop predictive models for catalyst design and optimization before undertaking costly synthetic efforts.

Finally, the field continues to expand into new application domains, particularly in addressing the challenges of waste management and resource recovery. [8] Catalytic upcycling of plastic waste, development of circular economy approaches, and integration of catalysis with renewable energy sources represent important frontiers where environmental catalysis can contribute significantly to sustainability goals.

As environmental catalysis progresses, the traditional boundaries between different subdisciplines of catalysis are becoming increasingly blurred, fostering cross-fertilization of ideas and approaches. The ultimate goal remains the development of efficient, sustainable, and economically viable catalytic technologies that can address the pressing environmental challenges of our time while enabling a transition toward more sustainable patterns of resource use and industrial production.

Catalytic remediation represents a cornerstone technology in air pollution control, enabling the efficient transformation of hazardous pollutants into less harmful substances at manageable temperatures. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the catalytic elimination of key air pollutants—Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), and by extension, ozone and particulate matter precursors. The focus is on advanced materials and methods that align with sustainable environmental goals, including low-energy catalytic cycles and synergistic removal of multiple pollutants. The content is structured for researchers and scientists engaged in developing next-generation air purification technologies.

Catalytic Removal of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx)

NOx, primarily NO and NO2, are significant contributors to smog, acid rain, and respiratory problems. Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) is the most widely deployed technology, but other methods like direct decomposition and low-temperature reduction are emerging.

Table 1: Catalytic Systems for NOx Removal

| Catalytic Method | Representative Catalyst | Key Reaction/Feature | Typical Temperature Range | Performance Highlights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3-SCR | V2O5-WO3(MoO3)/TiO2 | Standard industrial SCR | High Temperature | Mature technology, widely used | [10] |

| NH3-SCR | Nb-promoted CeZrOx | Enhanced activity & N2 selectivity | 190–460 °C | Wide operational temperature window | [11] |

| CO-SCR | Spinel Oxides (e.g., Cu0.4Co2.6O4) | NO + CO → N2 + CO2 | Medium-High | Removes two pollutants simultaneously; utilizes flue gas CO | [10] |

| Direct NO Decomposition | Ca2Co1La0.1Al0.9 spinel mixed oxide | NO → N2 + O2 | Up to 300 °C | 75% NO conversion; no reducing agent needed | [10] |

| Room-Temperature NO Reduction | MIL-100(Fe) Metal-Organic Framework | Bio-inspired enzymatic process | Room Temperature | Functions in presence of O2 and H2O; sustainable material | [12] |

Detailed Protocol: CO-SCR over Spinel Oxide Catalysts

Objective: To evaluate the performance of a spinel oxide catalyst (e.g., Cu0.4Co2.6O4) in the selective catalytic reduction of NOx using CO.

Materials:

- Catalyst: Synthesized Cu0.4Co2.6O4 spinel powder, pelletized and sieved to 40-60 mesh.

- Gases: 500 ppm NO, 5% CO, 5% O2, balanced with N2 (all high purity).

- Reactor System: Fixed-bed quartz tubular reactor (ID: 8 mm).

Procedure:

- Catalyst Loading: Place 0.2 g of the catalyst in the isothermal zone of the reactor. Secure with quartz wool.

- Reaction Conditions: Set the gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) to 20,000 h⁻¹. The typical feed composition should be 500 ppm NO and 500 ppm CO in the presence of 2-5% O2.

- Temperature Program: Heat the reactor from room temperature to 500 °C at a ramp rate of 5 °C/min, holding at intervals for steady-state measurement.

- Product Analysis: Use a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) gas analyzer to quantify the concentrations of NO, CO, CO2, and N2O at the reactor outlet.

- Data Calculation: Calculate NO and CO conversion using the formula: Conversion (%) = [(C_in - C_out) / C_in] × 100, where Cin and Cout are the inlet and outlet concentrations, respectively. N2 selectivity is calculated to check for by-product formation [10].

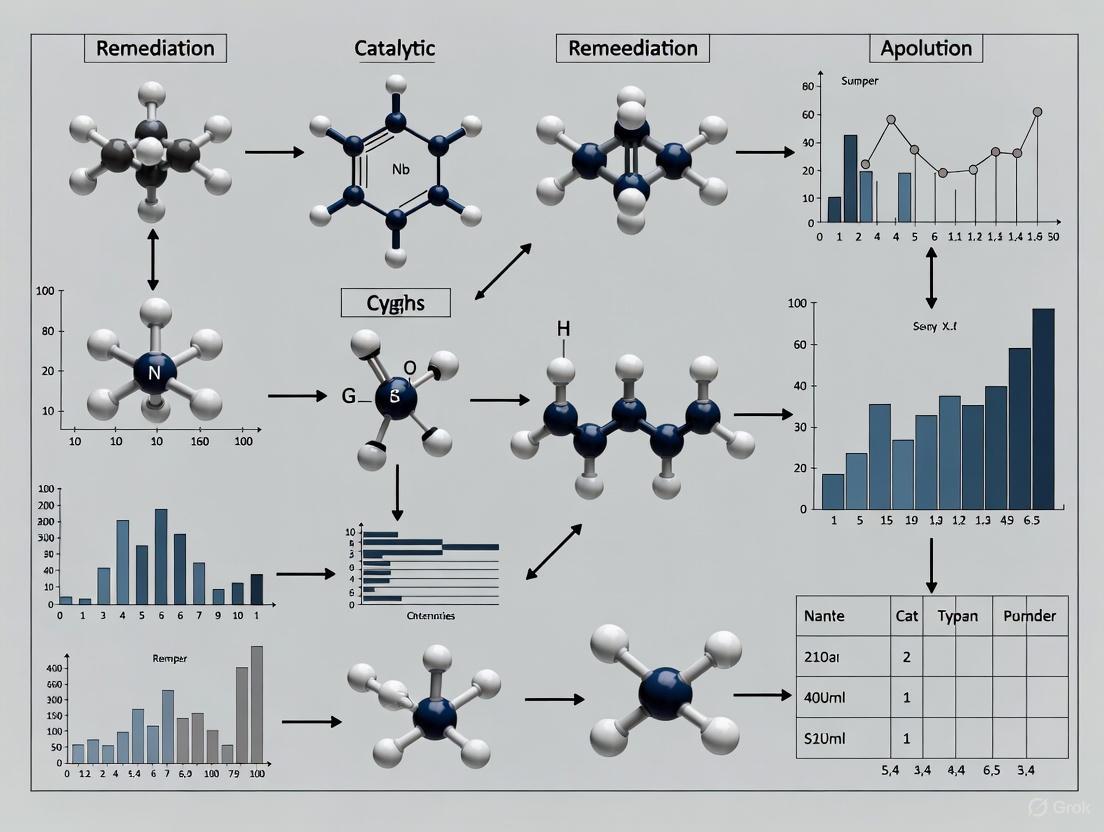

Reaction Pathway and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the reaction mechanism for CO-SCR over a spinel oxide catalyst, highlighting the role of oxygen vacancies.

Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

VOCs are carbon-based chemicals that vaporize at room temperature and are key precursors to ozone and secondary organic aerosols. Catalytic oxidation is a dominant destruction technology due to its high efficiency and lower energy requirement compared to thermal incineration.

Table 2: Catalytic Systems for VOC Oxidation

| VOC Category | Example Compound | Catalyst Example | Reaction Conditions | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Hydrocarbons | Toluene | Pt/MnOx-T | 30 ppm VOC, 300 ppm O3, Room Temp | 98% Conversion, 90% CO2 Selectivity | [13] |

| Aromatic Hydrocarbons | Benzene | MnO2/ZSM-5 | 30 ppm VOC, 450 ppm O3, 25 °C | 100% Conversion | [13] |

| Oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) | Formaldehyde | Noble metal single-atom catalysts | Ambient Temperature | High efficiency for degradable OVOCs | [13] |

| Chlorinated VOCs (CVOCs) | Dichloromethane | Durable metal oxides | Medium-High Temperature | Resistance to Cl poisoning is critical | [14] [15] |

| Aliphatic Hydrocarbons | Propane | Noble metal nanoparticles | Medium-High Temperature | Focus on C-H bond activation | [13] |

Detailed Protocol: Ambient Temperature Ozone-Assisted Oxidation of Toluene

Objective: To assess the catalytic activity of a Pt/MnOx-T catalyst in the ozone-assisted oxidation of toluene at room temperature.

Materials:

- Catalyst: 0.1 g of Pt/MnOx-T coated on a monolithic substrate.

- Gases: 30 ppm toluene in air (generated with a calibrated vapor generator), 300 ppm O3 (generated from pure O2 using an ozone generator).

- Reactor System: Continuous-flow glass reactor.

Procedure:

- System Setup: Place the catalyst monolith in the flow reactor. Ensure all gas lines are heated to 50 °C to prevent VOC condensation.

- Baseline Flow: Establish a flow of the toluene/air mixture at a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 60 L g⁻¹ h⁻¹.

- Ozone Introduction: Introduce the ozone stream, maintaining a concentration of 300 ppm.

- Reaction Monitoring: Maintain all conditions at room temperature (e.g., 25 °C). Analyze the inlet and outlet gas streams using an online Gas Chromatograph (GC) with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) for toluene and a Methanizer-FID for CO/CO2.

- Stability Test: Run the system for a minimum of 24 hours to evaluate catalyst stability and resistance to deactivation. Monitor for any partial oxidation products [13].

Experimental Workflow for VOC Oxidation

The workflow for evaluating a catalyst's performance in VOC oxidation, from preparation to stability testing, is outlined below.

Synergistic Removal and Advanced Concepts

Synergistic Catalytic Removal of VOCs and NOx

Industrial exhausts often contain complex mixtures of pollutants. Developing catalytic systems that can handle multiple pollutants simultaneously is a key research frontier.

- Challenge: Traditional systems often treat NOx (via NH3-SCR) and VOCs (via catalytic oxidation) in separate units.

- Opportunity: Catalysts can be designed with acid/redox binuclear active sites. The oxidation of VOCs can generate reactive intermediates that enhance the reduction of NOx, creating a synergistic cycle [15].

- Example System: Catalysts designed for the simultaneous removal of VOCs and NOx represent a significant market demand, moving beyond sequential treatment to integrated solutions [15].

Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration Protocols

Catalyst deactivation by poisoning, fouling, or thermal sintering is a major challenge in practical applications.

Common Regeneration Techniques:

- Thermal Treatment: Heating the catalyst to high temperatures in a controlled air flow to combust carbon-based deposits.

- Chemical Washing: Using specific chemical agents to dissolve inorganic contaminants (e.g., sulfur compounds).

- Steam Regeneration: Passing hot steam through the catalyst bed to remove hydrocarbon layers and rejuvenate active sites [16].

Protocol for Thermal Regeneration:

- Isolate the catalytic reactor and purge with inert N2.

- Heat the catalyst bed gradually (2-5 °C/min) to 450-500 °C under a controlled flow of air (2-5% O2 in N2).

- Hold at the target temperature for 4-8 hours to ensure complete oxidation of coke deposits.

- Cool slowly back to operating temperature under N2 flow before reintroducing the process stream [16].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Air Remediation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinel Oxides (AB₂O₄) | Active catalyst for NOx CO-SCR and N2O decomposition. | Accommodates various 3d transition metals; contains oxygen vacancies. | Non-precious, versatile catalyst platform [10]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (e.g., MIL-100(Fe)) | Low-temperature NO reduction catalyst. | Highly porous, tunable structure; bio-inspired active sites. | Emerging material for ambient temperature applications [12]. |

| Noble Metal Nanoparticles (Pt, Pd) | Active phase for VOC oxidation catalysts. | High intrinsic activity for C-H and C-C bond cleavage. | Often supported on high-surface-area oxides [14] [13]. |

| Niobia (Nb₂O₅) | Catalyst promoter in NH3-SCR. | Imparts strong Lewis and Brønsted acidity. | Enhances activity and N2 selectivity of oxide catalysts [11]. |

| Three-Dimensionally Ordered Macroporous (3DOM) Materials | Catalyst support structure. | High surface area, superior mass transfer for reactants. | Used to enhance performance of both noble metal and oxide catalysts [15]. |

The escalating challenges of air pollution and climate change have intensified the search for advanced remediation technologies. Among these, catalysis-based methods stand out for their potential to directly purify atmospheric pollutants under ambient conditions. Photocatalysis and ambient temperature catalysis represent two pivotal branches of this technology, leveraging fundamental redox reactions to degrade harmful pollutants into benign substances like carbon dioxide and water [17] [6]. These systems are central to pioneering concepts such as the "Environmental Catalytic City," which envisions urban spaces coated with catalytic materials capable of self-purification without additional energy consumption [17]. This document details the fundamental mechanisms, applications, and standardized experimental protocols for these catalytic technologies, providing a framework for their development in air pollution control research.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Pathways

Photocatalysis: Principles and Redox Mechanisms

Photocatalysis is a light-driven process where a semiconductor material absorbs photons to generate electron-hole pairs that initiate redox reactions at its surface.

- Photon Absorption and Charge Carrier Generation: The core process begins when a photocatalyst absorbs a photon with energy equal to or greater than its bandgap energy ((E_g)), promoting an electron ((e^-)) from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thereby creating a hole ((h^+)) in the VB [18]. This separation creates the redox-active species.

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation: The photo-generated electrons and holes migrate to the catalyst surface where they participate in redox reactions with adsorbed species. Electrons typically reduce atmospheric oxygen ((O2)) to form superoxide radical anions ((•O2^-)), while holes oxidize water vapor ((H_2O)) or hydroxide ions ((OH^-)) to form hydroxyl radicals ((•OH)) [19] [18]. These ROS are highly reactive and non-selectively oxidize a wide range of organic pollutants and inorganic gases.

- Pollutant Degradation: The reactive radicals mineralize volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ozone ((O3)), and other pollutants into harmless (CO2) and (H2O) [17] [20]. For instance, titanium dioxide ((TiO2)), a benchmark photocatalyst, under ultraviolet light can degrade formaldehyde and nitrogen oxides [17].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential mechanism of heterogeneous photocatalysis for air pollutant degradation:

Ambient Temperature Catalysis: Non-Photocatalytic Purification

In contrast, ambient temperature catalysis (also referred to as thermal catalysis at room temperature) facilitates the decomposition of pollutants without requiring light activation. This process relies on catalysts that possess high intrinsic activity, enabling them to activate oxygen molecules at ambient temperatures to drive oxidation reactions [17] [21].

- Oxygen Activation and Lattice Oxygen Role: The critical step is the activation of triatomic oxygen ((O2)) from air. Catalysts featuring transition metals (e.g., Pt, Ir, Co, Fe) or specific coordination structures (e.g., single-atom Ir-N(4)) can split (O2) into reactive atomic oxygen or facilitate its transfer to pollutants [21]. In some metal oxide systems, lattice oxygen atoms from the catalyst surface can directly participate in the oxidation, creating oxygen vacancies that are subsequently replenished by atmospheric (O2) [21] [22].

- Pollutant Decomposition Pathway: Formaldehyde ((HCHO)), for example, can be oxidized to formate species and finally to (CO2) and (H2O) on a Pt/(TiO2) surface [17] [21]. Similarly, ozone ((O3)) decomposes into oxygen on catalysts like NiFe-layered double hydroxide [17]. The mechanism often involves the pollutant molecule adsorbing onto an active site, where it is oxidized by activated oxygen species.

The diagram below outlines the general mechanism for ambient temperature catalytic oxidation:

Comparative Analysis of Key Mechanisms

The table below provides a quantitative and mechanistic comparison of these two catalytic pathways.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Photocatalysis and Ambient Temperature Catalysis

| Feature | Photocatalysis | Ambient Temperature Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Source | Light (UV/Visible photons) [19] | Chemical potential (Thermal energy at ambient temperature) [17] |

| Key Redox Initiator | Photo-generated electrons ((e^-)) and holes ((h^+)) [18] | Activated oxygen species from (O_2) dissociation or lattice oxygen [21] |

| Representative Catalysts | Titanium Dioxide ((TiO2)), Zinc Oxide ((ZnO)), graphitic Carbon Nitride ((g)-C(3)N(_4)) [19] [18] | Pt/(TiO_2), NiFe-LDH, Single-Atom Ir, Co-Ni hydrous oxides [17] [21] [22] |

| Typical Target Pollutants | VOCs, NOx, Ozone, Bacteria/Viruses [20] [18] | Formaldehyde, Ozone, Carbon Monoxide, NO [17] [21] [22] |

| Quantum Efficiency/Yield | Often low (<100% for solar photons) due to charge recombination [18] | Turnover Frequency (TOF) is a more relevant metric (e.g., 401.8 mmol g(_{Ir}^{-1}) h(^{-1}) for HCHO on Ir-SA [21]) |

| Dominant Reactive Species | Hydroxyl radicals ((•OH)), Superoxide radicals ((•O_2^-)) [19] | Activated oxygen atoms, Lattice oxygen, Surface hydroxyl groups [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating Photocatalytic VOC Degradation

This protocol outlines a standard method for assessing the efficiency of a photocatalyst in degrading gaseous volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in a continuous-flow reactor.

1. Principle: A stream of contaminated air passes through a photocatalyst bed under controlled illumination. The degradation efficiency is determined by monitoring the inlet and outlet pollutant concentrations using appropriate analytical instrumentation [20] [18].

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Bench-Scale Photocatalytic Reactor: Typically a quartz tube or coated wall reactor to allow maximum light penetration.

- Light Source: UV LED lamp (e.g., 365 nm) or simulated solar light (Xe lamp with AM 1.5 filter). Light intensity should be measured with a radiometer.

- Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs): To precisely control the flow rates of synthetic air and VOC vapor.

- VOC Generation System: Vapor generator or syringe pump for introducing a constant concentration of VOC (e.g., formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, toluene).

- Online Analytical Instrument: Gas Chromatograph (GC) with FID/TCD, FTIR Spectrometer, or specific gas sensor for real-time concentration monitoring.

3. Procedure: 1. Catalyst Preparation: Coat the catalyst (e.g., (TiO2) nanoparticles) onto a substrate (glass plate, quartz wool) or use a fixed bed of catalyst pellets. Dry and precondition as needed. 2. System Assembly & Leak Check: Assemble the flow system and perform a leak test with an inert gas (e.g., N(2)) at the intended operating pressure. 3. Adsorption Equilibrium: In the dark, introduce the reactant gas mixture (e.g., 10 ppm VOC in synthetic air) at a defined flow rate (e.g., 100 mL/min) and weight hourly space velocity (WHSV). Monitor the outlet concentration until it stabilizes, indicating adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Record this baseline concentration ((C0)). 4. Initiate Photocatalysis: Turn on the light source. Continuously monitor the outlet VOC concentration ((C)) until a new steady state is reached. 5. Data Collection: Record parameters: time, flow rate, light intensity, inlet concentration ((C{in})), and outlet concentration ((C_{out})). 6. Control Experiment: Repeat steps 3-5 with an inert substrate (no catalyst) to account for any direct photolysis.

4. Data Analysis:

- Removal Efficiency ((R)): Calculate using ( R (\%) ) = \frac{C{in} - C{out}}{C_{in}} \times 100 ).

- Reaction Rate ((r)): Determine using ( r = \frac{F \times (C{in} - C{out})}{m} ), where (F) is the volumetric flow rate (m³/s) and (m) is the mass of the catalyst (kg).

- Quantum Yield ((Φ)): For monochromatic light, calculate using ( Φ = \frac{\text{Rate of reaction (molecules/s)}}{\text{Photon flux (photons/s)}} ).

Protocol 2: Assessing Ambient Temperature Catalytic Oxidation of NO

This protocol describes a method for testing the performance of catalysts in removing nitric oxide (NO) at room temperature without light, based on studies of Co-Ni hydrous oxides [22].

1. Principle: The catalyst is exposed to a stream of NO in synthetic air at ambient temperature. The removal performance is evaluated by measuring the NO and potential by-product (e.g., NO(_2)) concentrations over time. In situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) can be used to identify surface reaction intermediates [22].

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Fixed-Bed Flow Reactor: Made of glass or Teflon to minimize surface adsorption.

- Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs): For NO (in N(2)), O(2), and balance gas (He or Ar).

- Gas Analyzer: Chemiluminescence NO/NO(x) analyzer or FTIR for simultaneous measurement of NO and NO(2).

- In situ DRIFTS Cell: Equipped with environmental chamber for catalyst samples.

- Test Catalyst: e.g., Co(1)Ni(1)O(z)·nH(2)O [22].

3. Procedure: 1. Catalyst Pretreatment: Load the catalyst into the reactor. Pre-treat at 60°C under Ar flow for 1 hour to remove surface contaminants [22]. 2. Cool Down: Cool the system to the test temperature (e.g., 25°C). 3. Baseline Measurement: Flush the system with inert gas and establish a stable baseline for the gas analyzer. 4. NO Exposure & Data Recording: Switch the gas flow to the reaction mixture (e.g., 10 ppm NO, 21% O(2), balance Ar). Continuously record the outlet concentrations of NO and NO(2) versus time. 5. In situ DRIFTS Analysis (Parallel): For mechanistic studies, place catalyst in the DRIFTS cell. After pretreatment and cooling, collect a background spectrum in Ar. Then, introduce the NO/O(2) mixture and collect spectra at regular intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes for 30 minutes) to monitor the formation and evolution of surface species like nitrites and nitrates [22]. 6. Regeneration Test (Optional): After saturation (indicated by NO breakthrough), regenerate the catalyst, for instance, by washing with a Na(2)S(2)O(8) solution [22], and repeat the test to assess recyclability.

4. Data Analysis:

- NO Storage Capacity (NSC): Calculate the total amount of NO removed by the catalyst before breakthrough by integrating the area between the inlet and outlet concentration curves over time: ( NSC = \frac{F}{m} \int0^t (C{in} - C_{out}) \, dt ).

- Identify Intermediates: Analyze DRIFTS spectra to assign IR bands to specific surface species (e.g., nitrites at ~1337 cm⁻¹, nitrates at ~1415 cm⁻¹) [22].

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for evaluating a catalyst's performance in NO removal:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and their specific functions in experimental research for catalytic air pollution control.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Catalytic Air Remediation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Representative Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Benchmark semiconductor photocatalyst; requires UV light for activation. | P25 Degussa (Aeroxide) is a common standard due to its mixed-phase (anatase/rutile) structure and high activity [17] [18]. |

| Platinum on Titania (Pt/TiO₂) | Noble-metal loaded photocatalyst or ambient temperature catalyst for formaldehyde oxidation. | Enhances charge separation in photocatalysis; provides active sites for O₂ activation in thermal catalysis [17] [21]. |

| NiFe-Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) | Ambient temperature catalyst for ozone decomposition. | Effective for decomposing O₃ into O₂ without light; non-precious metal-based [17]. |

| Single-Atom Ir on N-doped Carbon | High-efficiency ambient temperature catalyst for formaldehyde oxidation. | Maximizes atom utilization; Ir-N₄ site facilitates O₂ dissociation [21]. |

| Co-Ni Hydrous Oxides (CoxNiyOz·nH2O) | Bimetallic catalysts for ambient temperature NO capture and storage. | Synergy between Co (nitrite formation) and Ni (nitrate formation) enhances NOx storage capacity [22]. |

| In situ DRIFTS Cell | For mechanistic studies to identify surface-adsorbed intermediates and reaction pathways. | Allows tracking of species like nitrites, nitrates, and carbonyls on catalyst surface under reaction conditions [22]. |

The mechanistic understanding of photocatalysis and ambient temperature catalysis provides a solid foundation for developing advanced air pollution control technologies. While photocatalysis offers the promise of utilizing solar energy, challenges like limited visible-light absorption and rapid charge carrier recombination persist [23] [18]. Ambient temperature catalysis bypasses the need for light but often involves strategic use of metals and requires robust, low-cost materials [21]. Future research must focus on designing novel catalysts, such as S-scheme heterojunctions or single-atom catalysts, that maximize atomic efficiency and stability while minimizing cost [18]. Interdisciplinary efforts combining advanced in situ characterization, theoretical modeling, and systems engineering are crucial to translate these fundamental mechanisms from laboratory protocols into practical, large-scale applications for creating cleaner atmospheric environments [17] [18].

Air pollution, characterized by hazardous gases, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and particulate matter, remains a critical global environmental challenge with severe implications for public health and ecosystem sustainability [24]. In response, advanced catalytic remediation technologies have emerged as potent solutions for mitigating airborne pollutants. Among these, nanocatalysis represents a paradigm shift, leveraging the unique properties of materials engineered at the nanoscale, with Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs) standing at the forefront of this innovation [24] [25]. SACs, featuring isolated metal atoms anchored on suitable supports, achieve maximum atomic utilization efficiency and often exhibit superior catalytic performance compared to traditional nanoparticle-based catalysts [25] [26]. These materials effectively bridge the gap between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis, offering nearly 100% atom utilization, distinct electronic properties, and exceptional catalytic activity and selectivity [24] [27]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for utilizing nano-structured materials and SACs in air pollution control, supporting research and development efforts in environmental catalysis.

Application Notes: Performance and Efficacy

Performance of Single-Atom Catalysts in Gas-Phase Remediation

Single-Atom Catalysts have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in degrading various air pollutants, often operating at lower temperatures with higher selectivity than conventional catalysts [24]. Their application spans the treatment of inorganic gaseous pollutants, VOCs, and particulate matter.

Table 1: Performance of Single-Atom Catalysts in NOx Reduction via CO-SCR

| Catalyst Sample | Reaction Temperature (°C) | NO Conversion (%) | N₂ Selectivity (%) | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ir₁/m-WO₃ | 350 | 73 | 100 | High N₂ selectivity under oxidizing conditions (2% O₂). | [25] |

| 0.3Ag/m-WO₃ | 250 | ~73 | 100 | Superior performance compared to nanoparticle-loaded catalyst (5Ag/m-WO₃). | [25] |

| Cr₀.₁₉Rh₀.₀₆CeO₂ | 200 | 100 | 100 | Achieves complete conversion and selectivity at moderate temperature. | [25] |

| Fe₁/CeO₂-Al₂O₃ | 250 | 100 | 100 | Al₂O₃ support enhances activity at lower temperatures vs. Fe₁/Al₂O₃. | [25] |

| Cu₁-MgAl₂O₄ | 300 | ~93 | ~92 | Effective for simultaneous NO and CO conversion. | [25] |

The data in Table 1 highlights the exceptional activity and selectivity of various SACs for the Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) of NOx using CO as a reductant. The single-atom architecture facilitates optimal adsorption and activation of reactant molecules, leading to high efficiency in breaking down harmful nitrogen oxides [25].

Nanocatalysts for Particulate Matter and Ozone Mitigation

Beyond NOx, nanocatalysts are also critical for addressing other key pollutants like particulate matter (PM₂.₅) and ground-level ozone (O₃). Long-term air quality monitoring and modeling studies, validated by machine learning, show significant declining trends in these pollutants in regions like China, underscoring the impact of advanced emission control technologies [28].

Table 2: Nanocatalyst Performance for Key Air Pollutants

| Pollutant | Nanocatalyst Example | Mechanism | Performance Highlights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO₂ | Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Photocatalytic Oxidation | Machine learning predicts a 28% reduction potential in urban environments. | [29] |

| PM₂.₅ | Various SACs | Catalytic Degradation | SACs contribute to broader PM₂.₅ reduction trends (e.g., -22.1 µg/m³ nationwide in China). | [24] [28] |

| O₃ | Not Specified (Data Trends) | N/A | Summertime O₃ concentrations decreased by 28.5 µg/m³ on average in China (2014-2023). | [28] |

| VOCs & Heavy Metals | Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Adsorption, Precipitation, Redox | Effective in reducing mobility and bioavailability of pollutants in environmental matrices. | [30] [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Single-Atom Catalysts via Wet-Impregnation

This protocol details the synthesis of SACs using a conventional wet-impregnation method, suitable for creating catalysts such as Pt₁/FeOₓ [24] [25].

Workflow Overview

Materials:

- Support Material: e.g., FeOₓ nanocrystals, CeO₂, Al₂O₃.

- Metal Precursor: Salt of the target metal (e.g., H₂PtCl₆·6H₂O for Pt SACs).

- Solvent: Deionized water or appropriate organic solvent.

- Equipment: Round-bottom flask, magnetic stirrer, drying oven, muffle furnace, tube furnace.

Procedure:

- Support Preparation: Disperse 1.0 g of the purified support material (e.g., FeOₓ) in 100 mL of deionized water within a round-bottom flask. Sonicate for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve a calculated amount of the metal precursor (e.g., 0.05 mmol H₂PtCl₆·6H₂O) in 20 mL of deionized water. The metal loading is typically 0.1-2.0 wt\%.

- Impregnation and Drying: Add the metal precursor solution dropwise to the support suspension under vigorous stirring at room temperature. Continue stirring for 12 hours. Subsequently, evaporate the solvent at 70°C using a rotary evaporator to obtain a solid powder.

- Calcination and Activation: Transfer the dried powder to a muffle furnace. Calcinate in static air at 300°C for 2 hours (heating rate: 2°C/min) to decompose the precursor. For final activation, reduce the catalyst under a flowing H₂/Ar (5\%/95\%) atmosphere in a tube furnace at 300°C for 1 hour.

- Characterization: Confirm the atomic dispersion of metal atoms using High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and analyze the electronic state via X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS).

Protocol 2: Synthesis of SACs Integrated with Electrospun Nanofibers (SA-ENFs)

This protocol describes the integration of SACs with electrospun nanofibers, creating hierarchical structures that enhance mass transfer and stability [26].

Workflow Overview

Materials:

- Polymer: e.g., Polyacrylonitrile (PAN).

- Solvent: e.g., N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Metal Precursor: e.g., Metal acetylacetonate or chloride salt.

- Equipment: Electrospinning apparatus (high-voltage power supply, syringe pump, collector).

Procedure:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.0 g of PAN in 10 mL of DMF under stirring for 6 hours to form a clear, viscous solution (10 wt\%).

- Electrospinning: Load the polymer solution into a syringe. Set the syringe pump flow rate to 1.0 mL/h, the applied voltage to 15 kV, and the distance between the needle tip and the rotating collector to 15 cm. Collect the resulting nanofibers as a non-woven mat.

- Metal Incorporation: Impregnate the electrospun nanofiber mat with a solution containing the metal precursor (e.g., 0.5 wt\% Pt) using the wet-impregnation method described in Protocol 1.

- Pyrolysis and Activation: Place the impregnated nanofiber mat in a tube furnace. Perform stabilization in air at 250°C for 1 hour, followed by carbonization in an N₂ atmosphere at 800°C for 2 hours (heating rate: 2°C/min). This step carbonizes the polymer and anchors the metal as single atoms.

- Characterization: Use HAADF-STEM to observe the fiber morphology and confirm atomic dispersion. Evaluate the specific surface area and porosity using N₂ physisorption.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Catalytic Performance for CO-SCR of NOx

This protocol outlines a standard test for evaluating catalyst performance in the Selective Catalatalytic Reduction of NO by CO [25].

Materials:

- Reactor System: Fixed-bed quartz tubular reactor, temperature-controlled furnace.

- Gas Supply: Standard gas mixtures (NO, CO, O₂, N₂ as balance gas).

- Analytical Equipment: Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) or FTIR gas analyzer.

Procedure:

- Catalyst Loading: Load 100 mg of the catalyst (60-80 mesh) into the center of the quartz reactor.

- Reaction Conditions: Set the total gas flow rate to create a desired Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV), e.g., 50,000 h⁻¹. A typical feed gas composition is 0.1\% NO, 0.4\% CO, and 1\% O₂ in N₂.

- Temperature Program: Raise the reactor temperature from room temperature to the target temperature (e.g., 50-400°C) with a controlled ramp. Allow the system to stabilize for 30 minutes at each measurement temperature.

- Product Analysis: Use an online GC or FTIR analyzer to quantify the concentrations of NO, CO, N₂, and CO₂ at the reactor outlet.

- Data Calculation:

- NO Conversion (%) = ([NO]ᵢₙ - [NO]ₒᵤₜ) / [NO]ᵢₙ × 100%

- N₂ Selectivity (%) = (2 × [N₂]ₒᵤₜ) / ([NO]ᵢₙ - [NO]ₒᵤₜ) × 100%

Mechanisms and Pathways

The superior performance of SACs stems from their unique geometric and electronic structures, which optimize reaction pathways. In the CO-SCR reaction, the mechanism typically involves synergistic sites on the catalyst surface [25].

Catalytic Mechanism for CO-SCR on a Single-Atom Site

- NO Adsorption and Activation: NO molecules adsorb onto the isolated metal atom (M). The strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) facilitates the activation and dissociation of NO, leading to the formation of N-adatoms and the creation of oxygen vacancies on the support [25].

- CO Adsorption and Reaction: CO molecules adsorb on the metal site or nearby support. They subsequently react with surface oxygen atoms or fill oxygen vacancies, forming CO₂. This step is crucial for regenerating active sites [25].

- N₂ Formation and Desorption: The N-adatoms combine to form N₂, which desorbs from the catalyst surface, completing the catalytic cycle. The single-atom site prevents the formation of N₂O, a common by-product on nanoparticle catalysts, thereby ensuring high N₂ selectivity [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanocatalyst Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors (e.g., H₂PtCl₆, Pt(acac)₂) | Source of active metal for SACs. | Choice affects dispersion and stability. Acetylacetonates (acac) often provide better control. |

| Support Materials (FeOₓ, CeO₂, Al₂O₃, C3N₄) | Anchor single atoms; influences electronic structure & stability. | High surface area and defect density (e.g., oxygen vacancies in CeO₂) are critical. |

| Electrospinning Polymers (PAN, PVP) | Form nanofibrous support for SA-ENFs. | PAN is common for producing carbon nanofibers upon pyrolysis. |

| Porous Template Agents (ZIF-8) | Create micro/mesopores in nanofibers to trap single atoms. | Pyrolyzes during thermal treatment, introducing porosity and nitrogen dopants. |

| Standard Gas Mixtures (NO, CO, O₂ in N₂) | Simulate flue gas for catalytic activity testing. | Require proper handling and calibration for accurate concentration measurements. |

Visioning Self-Purifying 'Environmental Catalytic Cities'

The concept of the 'Environmental Catalytic City' represents a transformative paradigm in urban environmental management, integrating advanced catalytic remediation technologies directly into city infrastructure to achieve autonomous pollution mitigation. This framework moves beyond traditional end-of-pipe solutions by creating built environments capable of self-purification through engineered catalytic processes applied to air, water, and soil matrices. The following application notes provide structured protocols and quantitative frameworks for implementing catalytic systems within urban settings, specifically targeting researchers and scientists developing scalable pollution control technologies. By embedding catalysis into urban fabric—from building surfaces to transportation networks—cities can evolve toward smart, self-regulating systems that actively combat environmental degradation while supporting sustainable development goals.

Conceptual Framework and Quantitative Performance Metrics

The self-purifying city utilizes natural self-purifying processes found in the urban environment, combined with artificially-enhanced technologies, to achieve smart, quick, and low-carbon removal of pollutants across various mediums including air, water, and soil [32]. This approach represents a significant advancement over conventional remediation methods by creating continuously active, integrated systems rather than employing intermittent treatment protocols.

Table 1: National Air Quality Trends (U.S. EPA, 2023) demonstrates the substantial progress achieved through regulatory and technological interventions, providing baseline data for evaluating future catalytic city implementations [33].

Table 1: Percentage Change in National Air Pollution Concentrations (1980-2023)

| Pollutant | 1980 vs 2023 | 1990 vs 2023 | 2000 vs 2023 | 2010 vs 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Monoxide | -88% | -79% | -65% | -18% |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (Annual) | -68% | -62% | -54% | -30% |

| Ozone (8-hour) | -26% | -18% | -12% | -1% |

| PM2.5 (Annual) | --- | --- | -37% | -15% |

| Sulfur Dioxide (1-hour) | -95% | -92% | -87% | -78% |

Catalytic strategies function by accelerating chemical reactions that convert harmful pollutants into less toxic substances without consuming the catalysts themselves [34]. This principle enables the development of sustainable urban systems capable of continuous operation with minimal energy input. The versatility of catalytic systems allows for precise targeting of specific urban pollutants through tailored catalyst design and application methodologies.

Table 2: Catalytic Technology Applications for Urban Remediation summarizes the primary implementation pathways for catalytic systems within the urban fabric, along with their specific functions and representative catalysts [34] [35].

Table 2: Catalytic Technology Applications for Urban Remediation

| Technology | Primary Function | Target Pollutants | Representative Catalysts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Converters | Vehicular emission control | NOx, CO, Hydrocarbons | Platinum, Palladium, Rhodium |

| Photocatalysis | Air/water purification | VOCs, Organic pollutants, Microbial contaminants | Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) |

| Catalytic Ozonation | Wastewater treatment | Organic pollutants, Disinfection byproducts | Activated Carbon, Manganese Oxide, Cerium Oxide |

| Scrubbers | Industrial emission control | SO₂, Chlorine, H₂S, HCl | Various alkaline reagents |

Experimental Protocols for Catalytic System Implementation

Protocol: Photocatalytic Coating Application for Building Surfaces

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of titanium dioxide (TiO₂)-based photocatalytic coatings applied to building exteriors for nitrogen oxide (NOx) abatement in urban environments.

Materials:

- Titanium dioxide photocatalyst (P25 Degussa or equivalent)

- Silicon-based or acrylic binding medium

- Application equipment (airless spray, roller)

- NOx concentration monitoring system

- Weathering test apparatus

- Control surface samples

Methodology:

- Catalyst Preparation: Formulate coating suspension with 3-7% TiO₂ by weight in binding medium optimized for substrate adhesion and catalyst exposure.

- Surface Application: Apply coating to test substrates (concrete, metal, composite) at 150-200 g/m² coverage rate using controlled spray technique.

- Activity Validation: Mount coated panels in exposure chambers with continuous 0.5-1.0 ppm NOx input under simulated solar radiation (300-400 nm UV at 10-30 W/m²).

- Performance Quantification: Monitor NOx concentration differentials across chamber using chemiluminescence detection at regular intervals (0, 24, 168, 744 hours).

- Durability Assessment: Subject coated samples to accelerated weathering (QUV testing) per ASTM G154 standards with post-exposure catalytic activity measurement.

Data Analysis: Calculate NOx removal efficiency (%) as [(Cin - Cout)/Cin] × 100. Compare performance degradation rates across coating formulations and substrates. Statistically analyze variance in performance across triplicate samples using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing (p<0.05 significance threshold).

Protocol: Catalytic Ozonation for Urban Wastewater Streams

Objective: To implement and optimize catalytic ozonation for enhanced removal of emerging contaminants from municipal wastewater effluents.

Materials:

- Ozone generator system

- Cerium oxide or manganese oxide catalyst (3-5 mm pellets)

- Fixed-bed catalytic reactor system

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Dissolved ozone analyzer

- Target contaminant standards (pharmaceuticals, personal care products)

Methodology:

- System Configuration: Pack fixed-bed reactor with selected catalyst (40-60 cm bed depth, 35-45% void volume).

- Process Optimization: Establish ozone dosing rate (2-10 mg/L) and hydraulic retention time (10-30 minutes) through factorial experimental design.

- Contaminant Analysis: Spike wastewater samples with target contaminants (500 µg/L each) and monitor degradation kinetics via LC-MS/MS sampling at 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30-minute intervals.

- Byproduct Screening: Identify and quantify transformation products using full-scan high-resolution mass spectrometry with non-target analysis.

- Catalyst Stability: Assess metal leaching (ICP-MS analysis) and catalytic activity retention through multiple treatment cycles (≥10 cycles).

Data Analysis: Determine first-order degradation rate constants for target contaminants. Compare efficiency against conventional ozonation controls. Calculate catalyst service life based on activity decay modeling.

Protocol: Field Deployment of Self-Purifying Pavement Systems

Objective: To validate the performance of photocatalytic pavement systems in real-world urban environments for ground-level ozone reduction.

Materials:

- TiO₂-modified asphalt or concrete paving blocks

- Portable ozone monitors (dual-path monitoring recommended)

- Meteorological station (temperature, humidity, solar radiation sensors)

- Traffic density monitoring equipment

- Control pavement section (identical without catalyst)

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Identify paired urban test sites with similar traffic patterns, building geometries, and meteorological conditions.

- Installation: Deploy catalytic pavement in 100m road section with control section of identical dimensions nearby.

- Monitoring Protocol: Position ozone monitors at 0.5m and 2.0m heights above pavement surface with continuous data logging (1-minute intervals).

- Data Collection: Conduct continuous monitoring over minimum 30-day period capturing varied meteorological conditions.

- Confounding Factor Control: Record parallel traffic density, wind speed/direction, and background ozone concentrations.

Data Analysis: Apply multivariate regression to isolate catalytic effect from meteorological and emission variables. Calculate daily ozone removal flux (mg ozone/m²/day) and compare diurnal patterns between test and control sites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Catalytic Urban Remediation Studies catalogs critical reagents and their applications in developing and testing environmental catalytic systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Catalytic Urban Remediation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Photocatalyst for pollutant degradation | P25 Aeroxide recommended for balanced anatase/rutile phases; activates under UV-A spectrum |

| Platinum Group Metals | Redox catalyst for oxidation/reduction | High cost necessitates optimized loading; vulnerable to poisoning requiring pretreatment systems |

| Cerium Oxide | Oxygen storage catalyst for ozonation | Fluorite structure enables high oxygen mobility; effective for advanced oxidation processes |

| Activated Carbon | Catalyst support & adsorbent | High surface area (>1000 m²/g) crucial for dispersion; surface functionalization enhances performance |

| Manganese Oxide | Catalytic ozonation & NOx adsorption | Multiple oxidation states facilitate electron transfer; effective at ambient temperatures |

| Zeolite Frameworks | Molecular sieving & catalyst support | Tunable acidity and pore size enables shape-selective catalysis; hydrophobic variants for moist conditions |

| Silica-Based Binders | Catalyst immobilization for coatings | Transparent matrices maximize light penetration for photocatalysis; weather-resistant formulations required |

Workflow Visualization for Catalytic City Implementation

Catalytic City Implementation Workflow

Catalyst Screening and Selection Protocol

The vision of self-purifying 'Environmental Catalytic Cities' represents a viable pathway toward sustainable urban ecosystems through integrated catalytic technologies. The protocols and frameworks presented establish methodological standards for research, development, and implementation. Critical challenges remain in catalyst durability under real-world conditions, cost-effective manufacturing at scale, and seamless integration with existing urban infrastructure. Interdisciplinary collaboration between material scientists, environmental engineers, urban planners, and policymakers will be essential to advance this paradigm from conceptual framework to practical reality. Future research should prioritize development of broad-spectrum catalysts, energy-efficient activation mechanisms, and standardized performance metrics to enable comparative assessment across diverse urban applications.

Implementing Solutions: Catalytic Technologies from Lab to Industrial Scale

Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) represents a cornerstone of modern catalytic remediation methods for air pollution control, specifically targeting the abatement of nitrogen oxides (NOx). NOx, comprising primarily nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), is a class of highly threatening pollutants emitted from stationary sources (e.g., power plants, industrial boilers) and mobile sources (e.g., vehicles, ships) [36] [37]. These gases are potent precursors to fine particulate matter (PM2.5), contribute to acid rain formation, destroy the ozone layer, and have undeniable impacts on air quality and human health, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [36] [38]. SCR technology operates on the principle of using a reductant, typically ammonia (NH₃) or urea, which selectively reacts with NOx over a catalyst to form harmless nitrogen (N₂) and water vapor (H₂O) [39] [40]. The heart of this technology is the catalyst, which dictates the efficiency, temperature window, and selectivity of the reaction. For decades, vanadium-based catalysts have been the industrial workhorse for NOx removal, but ongoing research continues to develop and optimize these and alternative catalysts to meet increasingly stringent environmental regulations and diverse operational challenges [41] [37].

Catalyst Types and Reaction Mechanisms

Vanadium-Based SCR Catalysts

Vanadium-based catalysts, particularly V₂O₅-WO₃(MoO₃)/TiO₂, are the most widely deployed catalysts for industrial NH₃-SCR applications [36] [37]. Their composition is meticulously engineered to balance high activity with durability. The active component, vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅), is dispersed on a high-surface-area titanium dioxide (TiO₂) support, which is particularly resistant to sulfur poisoning. Promoters like tungsten trioxide (WO₃) or molybdenum trioxide (MoO₃) are added to enhance the thermal stability of the TiO₂ support, increase surface acidity, improve catalytic activity, and suppress the undesired oxidation of SO₂ to SO₃ [36] [42].

These catalysts are valued for their broad working temperature window (typically 300–400 °C) and high NOx removal efficiency, often exceeding 90% [36] [43]. They are commercially available in several forms to suit different applications: honeycomb catalysts offer high geometric surface area and low pressure drop; plate catalysts are known for their robustness against dust erosion; and corrugated catalysts provide a balance of performance and cost-effectiveness [41] [37].

The mechanism of the NH₃-SCR reaction on vanadium-based catalysts is well-established and revolves around both the catalyst's acidity and redox properties [36]. The Eley-Rideal (E-R) mechanism is widely accepted, where NH₃ is first adsorbed on the V⁵⁺-OH Brønsted acid sites or V⁵⁺=O Lewis acid sites to form an activated ammonia intermediate. This adsorbed NH₃ then reacts with gas-phase or weakly adsorbed NO to form the reaction products [36]. The "standard" SCR reaction is described by the following equation, which requires oxygen: 4NH₃ + 4NO + O₂ → 4N₂ + 6H₂O [36] [37]

When nitrogen monoxide and nitrogen dioxide are present in a 1:1 ratio, the much faster "fast" SCR reaction prevails, significantly enhancing low-temperature activity: 2NO + 2NO₂ + 4NH₃ → 4N₂ + 6H₂O [36] [37]

Alternative SCR Catalysts

While vanadium catalysts dominate many fields, other catalyst families have been developed to address specific limitations, such as low-temperature activity or high-temperature stability.

- Zeolite-based Catalysts: Ion-exchanged zeolites (e.g., with Cu or Fe) are prominent alternatives, especially in automotive applications. They offer a wide operating temperature window and high thermal durability. However, their susceptibility to hydrothermal deactivation and poisoning by sulfur and alkali metals can be a limitation in some industrial environments [36] [37].

- CO-SCR Catalysts: An emerging eco-friendly technology utilizes carbon monoxide (CO) as a reductant instead of NH₃, thus avoiding the issues of ammonia slip and secondary pollution. Catalysts for this process include noble metals (Ir, Rh), transition metal oxides (Co, Ce, Fe, Cu), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). The mechanism often involves the critical role of oxygen vacancies in facilitating the cleavage of the N–O bond [44].

Table 1: Comparison of Major SCR Catalyst Types

| Characteristic | Vanadium-Based | Zeolite-Based | CO-SCR Catalysts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Components | V₂O₅-WO₃/TiO₂ | Cu, Fe exchanged zeolites | Noble metals, Co/Ce/Fe/Cu oxides |

| Typical Reductant | NH₃ or Urea | NH₃ or Urea | CO |

| Optimal Temp. Range | 300–400 °C | 350–550 °C | Varies (e.g., 150–450 °C for some Cu-based) |

| NOx Reduction Efficiency | >90% [43] | >90% | Varies by formulation |

| Key Advantages | Excellent SO₂ resistance, cost-effective | High thermal stability, wide window | No ammonia slip, "waste to waste" |

| Key Challenges | Narrower temp. window, V toxicity | Hydrothermal instability, poisoning | Inhibition by O₂, SO₂ tolerance |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The performance of SCR catalysts is quantified by their NOx conversion efficiency, N₂ selectivity, and operational stability under various conditions. The following table summarizes key performance data and market metrics for vanadium-based SCR catalysts, highlighting their central role in emission control.

Table 2: Vanadium-Based SCR Catalysts: Performance and Market Data

| Parameter | Value / Range | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NOx Reduction Efficiency | 90 – 95% [43] | Under optimal temperature and dosing conditions |

| N₂ Selectivity | High | Can be reduced by side reactions (e.g., N₂O formation) at high temps [36] |

| Operating Temperature | 300 – 400 °C [36] | Low-temperature variants target 200 – 300 °C [36] |

| Ammonia Slip | 2 – 10 ppm [43] | Unreacted NH₃; regulated to prevent secondary pollution |

| Global Market Size (2025) | ~USD 1.2 Billion [41] | Projected estimate |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2033) | ~5.8% [41] | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| Annual Production Volume | 500 – 600 million units [41] | Global estimate |

| Catalyst Lifetime | 3 – 5 years [43] [42] | Varies with flue gas composition and operational conditions |

Experimental Protocols for SCR Catalyst Evaluation

This section provides a detailed methodology for the synthesis, characterization, and performance evaluation of vanadium-based SCR catalysts, suitable for reproducibility in a research setting.

Catalyst Synthesis: Wet Impregnation Method

Objective: To prepare a V₂O₅-WO₃/TiO₂ catalyst with a target loading of 1.5 wt% V₂O₅ and 6 wt% WO₃. Principle: This common method involves depositing active metal precursors onto a pre-formed porous support from an aqueous solution [36].

Reagents and Materials:

- Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) support, anatase phase

- Ammonium metavanadate (NH₄VO₃)

- Ammonium metatungstate ((NH₄)₆H₂W₁₂O₄₀)

- Oxalic acid ((COOH)₂·2H₂O)

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Solution A (Vanadium precursor): Dissolve a calculated amount of ammonium metavanadate in a warm aqueous solution of oxalic acid (molar ratio of oxalic acid to V is 2:1) under continuous stirring until a clear blue solution is obtained.

- Solution B (Tungsten precursor): Dissolve a calculated amount of ammonium metatungstate in deionized water under stirring.

- Impregnation: Slowly add the TiO₂ support powder to the mixed Solution A and B. The total volume of the solution should be slightly more than the pore volume of the support to achieve incipient wetness impregnation.

- Aging: Allow the mixture to age at room temperature for 12 hours.

- Drying: Remove water by evaporating the mixture at 105 °C for 12 hours in a drying oven.

- Calcination: Transfer the dried powder to a muffle furnace and calcine in static air at 500 °C for 5 hours to decompose the ammonium salts and form the metal oxides.

Catalyst Characterization Protocols

1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

- Purpose: To identify the crystalline phases present in the catalyst and support.

- Protocol: Analyze the powder sample using a diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. Scan a 2θ range from 10° to 80° with a step size of 0.02°. The dominant phase should be anatase TiO₂. Highly dispersed V₂O₅ and WO₃ may not show distinct crystalline peaks, indicating good dispersion.

2. NH₃-Temperature Programmed Desorption (NH₃-TPD)

- Purpose: To quantify the surface acidity (amount and strength) of the catalyst.

- Protocol: Pre-treat 100 mg of catalyst at 500 °C under He flow. Adsorb NH₃ at 100 °C until saturation. Purge with He to remove physisorbed NH₃. Then, heat the sample from 100 °C to 700 °C at a constant ramp rate (e.g., 10 °C/min) under He flow. The desorbed NH₃ is monitored by a mass spectrometer or TCD, and the desorption profile indicates acid site strength distribution.

Catalytic Activity Testing Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the NOx conversion efficiency and N₂ selectivity of the synthesized catalyst under simulated flue gas conditions.

Reactor Setup:

- A fixed-bed quartz tubular reactor (ID: 8 mm) placed in a temperature-controlled furnace.

- The catalyst is sieved to 40-60 mesh and packed in the middle of the reactor.

- Gas flows are controlled by mass flow controllers, and NH₃ is introduced via a saturator or a separate mass flow controller.

Standard Reaction Conditions:

- Reaction Gas Composition: [45]

- NO: 500 ppm

- NH₃: 500 ppm (NH₃/NO = 1)

- O₂: 5%

- SO₂ (if testing resistance): 50-100 ppm

- H₂O (if testing resistance): 5-10%

- N₂: Balance gas

- Total Gas Flow Rate: 500 mL/min (Weight Hourly Space Velocity, WHSV ~30,000 h⁻¹).

- Temperature Ramp: Measure steady-state activity from 150 °C to 450 °C in 50 °C increments.

Analysis and Calculation:

- The inlet and outlet gas concentrations are analyzed by a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) gas analyzer or a gas chromatograph.

- NOx Conversion (%) is calculated as:

[NOx]₍ᵢₙ₎ - [NOx]₍ₒᵤₜ₎ / [NOx]₍ᵢₙ₎ × 100%. - N₂ Selectivity is determined by analyzing N₂O formation in the outlet gas.

Visualization of SCR Processes and Experimental Workflow

NH₃-SCR Reaction Mechanism on Vanadium Catalyst

The following diagram illustrates the widely accepted Eley-Rideal mechanism for the standard SCR reaction on a vanadium oxide active site.

SCR Catalyst Testing Workflow

This flowchart outlines the comprehensive experimental workflow for synthesizing and evaluating an SCR catalyst, from preparation to performance assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for SCR Catalyst Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Typical Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | High-surface-area support material | Anatase phase is preferred for its high activity and stability [36]. |

| Ammonium Metavanadate (NH₄VO₃) | Precursor for the active vanadium oxide (V₂O₅) component | Often dissolved with a complexing agent like oxalic acid [36]. |

| Ammonium Metatungstate | Precursor for the tungsten oxide (WO₃) promoter | Enhances thermal stability and surface acidity [37]. |

| Ammonia (NH₃) Gas | Reducing agent for the NH₃-SCR reaction | Used in simulated gas mixtures for activity testing. |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) Gas | Reducing agent for CO-SCR research | Alternative to NH₃; requires different catalyst formulations [44]. |

| Standard Gas Mixtures | For creating simulated flue gas | High-precision mixtures of NO, NO₂, O₂, SO₂ in balance N₂. |

| Oxalic Acid | Complexing agent | Used to dissolve vanadium precursors during impregnation [36]. |

| Zeolite Supports (e.g., ZSM-5, SAPO-34) | Microporous support for alternative catalysts | Used for preparing metal-exchanged (Cu, Fe) zeolite catalysts [36]. |

Vanadium-based SCR catalysts remain a vital and effective technology for achieving global NOx emission targets, underpinned by a mature understanding of their synthesis, mechanism, and application. However, the relentless tightening of environmental regulations and the diverse needs of different industries drive continuous research and development. This pursuit focuses on enhancing low-temperature activity, improving resistance to poisoning (e.g., by alkali metals, SO₂, and H₂O), and extending catalyst longevity [36] [41]. Furthermore, the exploration of alternative catalysts, such as advanced zeolites and innovative CO-SCR systems, highlights a dynamic research field aimed at overcoming the limitations of traditional technologies and enabling more sustainable, efficient, and tailored solutions for catalytic air pollution remediation [37] [44]. The experimental protocols and data summarized in this document provide a foundation for researchers to contribute to these critical advancements.

Catalytic thermal oxidizers (CTOs), also known as catalytic incinerators, are advanced air pollution control systems designed to destroy Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) through catalytic oxidation. These systems facilitate the oxidation of pollutants to carbon dioxide (CO₂) and water vapor (H₂O) at significantly lower temperatures than conventional thermal oxidizers by using a catalyst to increase the kinetic reaction rate [46]. This technology provides an efficient remediation method for industrial exhaust streams, combining high destruction efficiency with reduced energy consumption. The operational principle centers on the catalyst providing an alternative reaction pathway, thereby lowering the activation energy required for the oxidation reaction [47]. This process is integral to catalytic remediation methods for air pollution control, offering a sustainable solution for emissions compliance.

Fundamental Design and Operating Principles

Core Mechanism

The catalytic oxidation process involves a heterogeneous catalytic reaction where gaseous pollutants diffuse to the catalyst surface and adsorb onto active sites. The core mechanism can be summarized in a simplified diagram:

Figure 1. Catalytic oxidation process flow. VOCs and oxygen are pre-heated and passed over a catalyst bed, where they are oxidized into benign compounds at temperatures between 500°F and 650°F [46] [47] [48].

Upon adsorption, the VOCs and HAPs undergo a surface reaction with oxygen, forming the oxidation products (CO₂ and H₂O), which subsequently desorb from the catalyst surface and are released into the gas stream. The catalyst itself remains unchanged, allowing for continuous operation [46] [49]. This entire process typically occurs within a temperature range of 500°F to 650°F (260°C to 343°C), substantially lower than the 1,400°F to 1,500°F (760°C to 815°C) required for thermal oxidation without a catalyst [47] [50]. The lower operating temperature is the primary factor behind the reduced auxiliary fuel requirement, making catalytic oxidation a more energy-efficient technology [51] [47].

Critical Design Parameters

The efficiency of a catalytic oxidizer is governed by several interdependent design and operational parameters, which must be optimized for the specific application. The key parameters are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Critical Design and Operational Parameters for Catalytic Oxidizers

| Parameter | Typical Operating Range | Function and Impact on System Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Temperature [46] [47] | 500°F - 650°F (260°C - 343°C) | Must be high enough to initiate catalytic oxidation. Directly influences destruction efficiency and fuel consumption. |

| Catalyst Bed Residence Time [46] | 0.3 - 0.5 seconds | Sufficient time is required for the gas stream to contact the catalyst and for the oxidation reaction to occur. |

| Catalyst Activity [46] [16] | N/A | A function of the catalytic metal (e.g., Pt, Pd), carrier material (e.g., Alumina), and catalyst structure. Determines reaction rate. |

| Turbulence/Mixing [46] | N/A | Ensures uniform distribution of VOCs and oxygen across the catalyst surface, preventing channeling and maximizing efficiency. |

| VOC/HAP Concentration & Species [46] [48] | Up to 2,500 ppm (for CatOx) | The chemical nature of the pollutants affects the required temperature and catalyst selection. Some compounds can poison the catalyst. |

| Heat Recovery Efficiency [46] [51] | Varies (Recuperative: ~50-70%) | Percentage of heat recovered from the clean exhaust to preheat incoming air, drastically reducing auxiliary fuel needs. |

The design must ensure a harmonious balance among these parameters. For instance, a higher operating temperature may compensate for a shorter residence time, but at the cost of increased fuel consumption [46]. Similarly, effective turbulence and mixing are prerequisites for realizing the full benefits of an optimal residence time and temperature.

Performance Monitoring and Diagnostic Protocols