Advancing Environmental Hazard Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide to QSAR Model Development and Validation

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model development for environmental chemical hazard assessment.

Advancing Environmental Hazard Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide to QSAR Model Development and Validation

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model development for environmental chemical hazard assessment. It explores the foundational principles driving the shift from animal testing to New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), details advanced machine learning and meta-learning techniques for model building, and addresses critical troubleshooting for sparse data and applicability domains. The content systematically covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analysis of model performance, with practical applications illustrated through case studies on endocrine disruption, aquatic toxicity, and cosmetic ingredient assessment. This resource supports the development of robust, reliable computational tools for predicting chemical hazards and filling data gaps in regulatory decision-making.

The Foundation of QSAR: Principles, Drivers, and Current Landscape in Environmental Toxicology

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) represent a suite of innovative scientific tools and frameworks designed to modernize chemical safety assessment. These methodologies, which include in vitro models, computational approaches, and high-throughput screening methods, are increasingly critical for environmental chemical hazard assessment, particularly as we face the challenge of evaluating thousands of chemicals lacking complete toxicological profiles [1]. The drive toward NAMs is fueled by both ethical imperatives to reduce animal testing and the scientific need for more human-relevant data, as traditional animal models often demonstrate poor predictivity for human toxicity, with rates as low as 40-65% [2]. Within this paradigm, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling stands as a cornerstone computational tool, enabling researchers to predict chemical hazards based on structural properties without additional animal experimentation.

The integration of NAMs into regulatory frameworks is already underway. Agencies including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), and Health Canada are developing structured approaches to implement these methods [1]. For instance, Health Canada's HAWPr computational toolkit automates chemical prioritization by integrating diverse data streams like ToxCast assay results and OECD QSAR Toolbox predictions, establishing a data hierarchy that prioritizes in vivo > in vitro > in silico evidence while assigning confidence levels to computational predictions [3]. This transition toward a new testing paradigm aligns with the principles of Next Generation Risk Assessment (NGRA), an exposure-led, hypothesis-driven approach that integrates various NAMs to evaluate chemical safety [2].

Application Notes: QSAR and Integrated Approaches

QSAR for Predicting Thyroid Hormone System Disruption

The application of QSAR models for identifying endocrine-disrupting chemicals demonstrates their significant value in environmental hazard assessment. A recent review spanning 2010-2024 identified eighty-six different QSARs specifically developed to predict thyroid hormone (TH) system disruption, highlighting the research community's substantial investment in this area [4]. These models typically focus on Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) within the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework for TH disruption, such as chemical binding to thyroid receptors or transport proteins.

Successful QSAR development for this endpoint requires careful consideration of several components:

- Endpoint Selection: Models target specific MIEs like thyroperoxidase inhibition or transthyretin binding rather than apical adverse outcomes.

- Chemical Domain Definition: Establishing clear applicability boundaries ensures reliable predictions for structurally similar compounds.

- Descriptor Mechanistic Interpretation: Molecular descriptors must have biological relevance to TH system disruption pathways.

- Validation Protocols: Both internal (cross-validation) and external (hold-out test sets) validation are essential for assessing predictive performance.

The review also identified critical research gaps needing attention, including limited models for certain TH disruption mechanisms and insufficient coverage of diverse chemical classes, pointing toward necessary future development directions [4].

Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA)

The true power of NAMs emerges when QSAR models are integrated within broader Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) frameworks. These approaches combine multiple data sources – in silico, in chemico, and in vitro – to reach robust hazard conclusions while minimizing animal use [1]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) actively promotes IATA as a mechanism for regulatory decision-making, particularly for complex toxicity endpoints where single-assay replacements are insufficient.

A demonstrated application involved the crop protection products Captan and Folpet, where a multiple NAM testing strategy comprising 18 in vitro studies successfully identified these chemicals as contact irritants, producing risk assessments consistent with those derived from traditional mammalian test data [2]. This case exemplifies how defined combinations of NAMs can provide sufficient evidence for regulatory decisions without additional animal testing.

Quantitative Implementation Data

Table 1: Current Implementation Status of Selected NAMs in Hazard Assessment

| Methodology | Familiarity & Use Level | Primary Applications | Regulatory Adoption Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSARs/Read-Across | High familiarity and use | Prioritization, hazard identification | Established in OECD Toolbox, EPA TSCA, Health Canada HAWPr |

| Transcriptomics | Emerging use | Point of Departure (POD) derivation, mechanism screening | EPA's ETAP workflow, Corteva Agriscience case studies |

| Organ-on-Chip | Limited but growing | ADME modeling, complex toxicity | FDA pilot programs, first IND approval (NCT04658472) |

| -Omics Approaches | Seldom used | AOP development, biomarker discovery | OECD OORF reporting framework, Health Canada tPOD approaches |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Alternative Methods for Thyroid Hormone Disruption Prediction

| Model Type | Endpoint | Accuracy Range | Chemical Space | Regulatory Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | Thyroperoxidase inhibition | 75-89% | Mostly phenols | Medium |

| Molecular Docking | Transthyretin binding | 80-85% | Diverse structures | Low-Medium |

| In Vitro Assays | Receptor binding/activity | 70-82% | Broad applicability | Medium-High |

| Integrated Testing Strategy | Overall TH disruption | >90% | Limited validation set | High |

Survey data indicates significant heterogeneity in the familiarity and use of specific NAMs across different sectors. While QSARs represent one of the most established and widely used approaches, particularly in regulatory contexts, other promising methodologies like transcriptomics and microphysiological systems show substantial potential but currently have more limited implementation [5] [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: QSAR Model Development for Thyroid Hormone Disruption Prediction

Objective

To develop a validated QSAR model for predicting chemical disruption of the thyroid hormone system through competitive binding to transthyretin.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR and Computational Analysis

| Reagent/Software | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Chemical grouping, analogue identification | Version 4.5 or higher |

| Dragon Descriptor Software | Molecular descriptor calculation | Latest version with 5000+ descriptors |

| KNIME Analytics Platform | Workflow integration and model building | With chemistry extensions |

| R/Python | Statistical analysis and machine learning | Caret (R) or Scikit-learn (Python) |

| Transthyretin Binding Assay Data | Model training and validation | IC50 values from published literature |

| Chemical Structures | Model input | SMILES notation, purified structures |

Methodology

Step 1: Data Curation and Preparation

- Compile a dataset of chemicals with experimentally determined transthyretin binding affinities (IC50 values) from peer-reviewed literature.

- Standardize chemical structures using IUPAC conventions, removing duplicates and salts, and generating optimized 3D conformations.

- Critical Consideration: Ensure chemical diversity to build a robust model with broad applicability.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Calculate molecular descriptors using appropriate software (e.g., Dragon).

- Apply pre-filtering to remove constant and near-constant descriptors.

- Use multivariate analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) and expert knowledge to select descriptors mechanistically relevant to protein binding.

- Validation Check: Assess descriptor redundancy using correlation matrices.

Step 3: Dataset Division and Applicability Domain Definition

- Split data into training (≈70%), validation (≈15%), and test (≈15%) sets using rational methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone) to ensure representative distribution.

- Define the model's applicability domain using approaches such as leverage and Euclidean distance to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable.

Step 4: Model Building and Internal Validation

- Employ multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Partial Least Squares Regression).

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation on the training set.

- Assess internal performance using Q² and R² values from cross-validation.

Step 5: External Validation and Reporting

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using OECD validation principles.

- Calculate key performance metrics: R²ₑₓₜ, Q²ₑₓₜ, RMSE, and MAE.

- Prepare complete documentation following OECD QSAR Model Reporting Format.

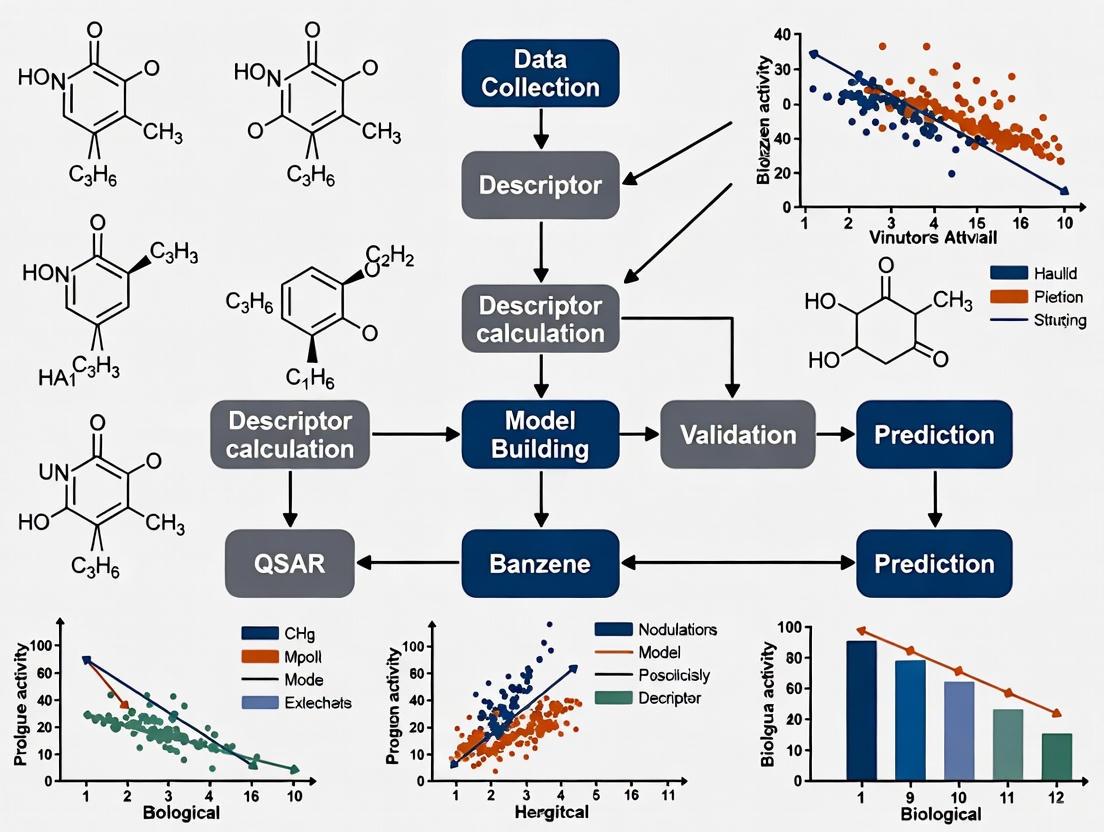

Diagram 1: QSAR Model Development Workflow

Protocol 2: Integrated Testing Strategy for Thyroid Disruption

Objective

To implement a tiered testing strategy that combines QSAR predictions with in vitro assays for comprehensive thyroid hormone disruption assessment without animal testing.

Materials and Reagents

- Pre-validated QSAR models for thyroid-related endpoints

- Transthyretin (TTR) binding assay kit

- Thyroperoxidase (TPO) inhibition assay system

- Thyroid receptor beta (TRβ) reporter gene assay

- Relevant positive and negative controls

Methodology

Tier 1: Computational Prioritization

- Screen chemicals using multiple QSAR models for key MIEs in thyroid disruption AOP.

- Apply structural alerts for thyroid disruption identified from existing databases.

- Criteria for Progression: Chemicals predicted positive by ≥2 computational methods advance to Tier 2.

Tier 2: In Vitro Confirmation

- Perform TTR binding assay following standardized protocol with 8-point concentration series.

- Conduct TPO inhibition assay for chemicals showing TTR binding activity.

- Quality Control: Include reference chemicals in each assay run.

Tier 3: Mechanistic Characterization

- For chemicals positive in Tier 2, implement TRβ reporter gene assay to assess receptor activation/suppression.

- Consider additional mechanistic assays based on chemical structure and prior results.

Data Integration and WoE Assessment

- Combine results from all tiers using a predefined scoring system.

- Apply WoE approach to classify thyroid disruption potential.

- Reporting: Document all data and decision points for regulatory submission.

Diagram 2: Tiered Testing Strategy for Thyroid Disruption

Technical and Regulatory Considerations

Overcoming Barriers to NAM Implementation

Despite their promise, NAMs face several implementation barriers that have slowed regulatory adoption. These include scientific and technical challenges, regulatory inertia, and perceptions that NAM-derived data may not gain regulatory acceptance [2]. A key scientific concern involves the benchmarking of NAMs against traditional animal data, which creates a circular problem where novel human-relevant methods are judged against potentially flawed animal models [2].

Successful cases of NAM implementation offer valuable insights for overcoming these barriers. The development of Defined Approaches (DAs) – specific combinations of data sources with fixed data interpretation procedures – has facilitated regulatory acceptance for endpoints like skin sensitization and eye irritation [2]. These DAs are now codified in OECD Test Guidelines (e.g., OECD TG 467, 497), providing clear frameworks for standardized application [2].

Regulatory Confidence Building

Building regulatory confidence in NAMs requires addressing several critical aspects:

- Demonstration of Reliability and Relevance: NAMs must consistently produce reliable results relevant to human biology across different chemical classes.

- Development of Performance Standards: Standardized assessment criteria help evaluate NAM performance for specific applications.

- Generation of Public Data: Open-access databases of NAM data for reference chemicals facilitate independent validation.

- Development of IATA Case Studies: Real-world examples demonstrating successful NAM application strengthen regulatory trust.

Initiatives like the European Partnership for the Assessment of Risks from Chemicals (PARC) and the EPA's Transcriptomic Assessment Product (ETAP) represent structured efforts to build this evidence base [3] [1]. The HAWPr toolkit from Health Canada exemplifies how regulatory agencies are already integrating NAMs into practical workflows for chemical prioritization and screening [3].

The rise of New Approach Methodologies represents a fundamental transformation in environmental chemical hazard assessment, with QSAR model development playing a central role in this paradigm shift. The protocols and application notes presented here provide actionable frameworks for implementing these approaches in research and regulatory contexts. As the field evolves, the integration of QSAR with emerging technologies like transcriptomics, organ-on-chip systems, and artificial intelligence will further enhance our ability to predict chemical hazards using human-relevant mechanisms while progressively reducing reliance on animal testing. The ongoing challenge remains to standardize these approaches, build regulatory confidence through validation studies, and train a new generation of scientists in these innovative methodologies.

Global regulatory policies are fundamentally transforming chemical hazard and risk assessment, creating a powerful driver for the adoption of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. Motivated by the pursuit of a "toxic-free environment" and the operationalization of Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD) frameworks, regulatory bodies are increasingly mandating the use of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) to overcome the limitations of traditional animal testing and address data gaps for thousands of chemicals [6] [7]. The European Union's Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability and ambitious Zero Pollution Action Plan exemplify this shift, creating an urgent need for reliable, predictive in-silico tools [7]. QSAR methodologies, which mathematically link a chemical's molecular structure to its biological activity or properties, have consequently moved from a supportive role to a central position in regulatory science [8] [9]. This application note details the essential protocols and frameworks for developing QSAR models that meet rigorous regulatory standards for environmental chemical hazard assessment, enabling researchers to contribute to the design of safer, more sustainable chemicals.

Regulatory Frameworks and Quantitative Requirements

International regulatory frameworks have established clear, quantitative principles to ensure the scientific validity and regulatory acceptability of (Q)SAR models. The foundational guidance from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been augmented by a new assessment framework to increase regulatory uptake.

Table 1: Core Principles of the OECD (Q)SAR Validation and Assessment Frameworks

| Principle | Description | Regulatory Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Endpoint | "A defined endpoint" must be specified, ensuring the model's purpose is unambiguous [10]. | Enforces scientific clarity and prevents misuse of models for unintended endpoints. |

| Unambiguous Algorithm | "An unambiguous algorithm" is required for model building and prediction [10]. | Ensures transparency, reproducibility, and reliability of predictions. |

| Defined Applicability Domain | "A defined domain of applicability" specifies the chemical space and data on which the model is valid [10]. | Critical for determining when a model can be reliably used for a new chemical, preventing over-extrapolation. |

| Appropriate Validation | "Measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity" must be provided [10]. | Quantifies the model's performance and reliability for regulatory decision-making. |

| Mechanistic Interpretation | "A mechanistic interpretation, if possible," is encouraged [8]. | Increases scientific confidence in the model by linking descriptors to biological or toxicological mechanisms. |

A significant recent development is the OECD (Q)SAR Assessment Framework (QAF), which provides structured guidance for regulators to evaluate the confidence and uncertainties in (Q)SAR models and their predictions [11]. The QAF establishes new principles for evaluating individual predictions and results from multiple predictions, offering a pathway to increase regulatory acceptance by providing "clear requirements to meet for (Q)SAR developers and users" [11].

QSAR Model Development: Application Protocol

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for constructing a validated QSAR model suitable for use in environmental hazard assessment, aligned with regulatory standards.

Stage 1: Data Curation and Preparation

Objective: To compile and standardize a high-quality dataset of chemical structures and associated biological activities.

- Dataset Collection: Compile structures and associated activity data (e.g., LC50, EC50) from reliable public or proprietary databases. Ensure the dataset covers a diverse chemical space relevant to the assessment [9] [12].

- Data Cleaning and Preprocessing:

- Standardize chemical structures: Remove salts, normalize tautomers, and handle stereochemistry consistently [9].

- Handle duplicates: Resolve multiple activity entries for the same structure, for example, by taking the mean or median value [12].

- Convert biological activities to a common unit and scale, typically using logarithmic transformations (e.g., pLC50 = -logLC50) [9].

- Data Splitting: Divide the cleaned dataset into a training set (for model building), a validation set (for hyperparameter tuning), and an external test set (for final model evaluation). The external test set must be strictly reserved and not used in any model training steps [9].

Stage 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

Objective: To generate quantitative numerical representations of the molecular structures and select the most relevant features.

- Descriptor Calculation: Use software tools such as PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, or RDKit to calculate a wide array of molecular descriptors. These can include constitutional, topological, geometric, and electronic descriptors [9].

- Feature Selection:

- Apply feature selection methods to reduce dimensionality and avoid overfitting.

- Filter Methods: Rank descriptors based on their individual correlation with the activity [9].

- Wrapper/Embedded Methods: Use algorithms like genetic algorithms or LASSO regression to select the most informative descriptor subset [9] [12].

- The goal is to remove a high percentage (e.g., 62-99%) of redundant or irrelevant data to improve model performance [12].

Stage 3: Model Building and Training

Objective: To construct a mathematical model that relates the selected molecular descriptors to the biological endpoint.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose an appropriate algorithm based on the dataset's characteristics and the relationship's complexity.

- Model Training: Train the model using only the training set. If using a validation set, use it to tune the model's hyperparameters [9].

Stage 4: Model Validation and Application

Objective: To rigorously assess the model's predictive performance and define its limits of use.

- Internal Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) or leave-one-out cross-validation on the training set to estimate model robustness [9].

- External Validation: Test the final model on the held-out external test set to obtain a realistic measure of its predictive power on unseen chemicals [9] [12].

- Define Applicability Domain (AD): Establish the chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions. This is a critical requirement for regulatory acceptance [10] [9].

Diagram 1: QSAR modeling workflow.

Advanced Application: Machine Learning for Ecosystem-Level Hazard Prediction

Advanced machine learning techniques are now being deployed to bridge critical data gaps in ecotoxicology on an unprecedented scale, enabling ecosystem-level hazard assessment.

Protocol: Pairwise Learning for Chemical Hazard Distribution (CHD)

Objective: To predict ecotoxicity (e.g., LC50) for any combination of chemical and species, filling data gaps for millions of untested (chemical, species) pairs [7].

Methodology:

- Input Data Matrix Construction: Compile a sparse matrix of experimental LC50 values, where rows represent chemicals and columns represent species. Coverage in such a matrix is typically very low (~0.5%) [7].

- Bayesian Matrix Factorization:

- Treat the problem as a matrix completion task.

- Represent each (chemical, species, exposure duration) triplet as a sparse binary feature vector.

- Employ a Factorization Machine model, as represented by the equation:

y(x) = w_0 + ∑(w_i x_i) + ∑∑(x_i x_j ∑(v_i,k v_j,k))[7] - Here, the global bias (

w_0), species/chemical/duration bias terms (w_i), and factorized pairwise interactions (v_i,k) are learned. - The pairwise interactions specifically capture the "lock and key" effect between individual species and chemicals.

- Output Generation and Application:

- Generate a fully populated matrix of Predicted LC50s.

- Use this matrix to construct novel hazard assessment tools:

- Hazard Heatmaps: Visualize the predicted sensitivity of all species to all chemicals.

- Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSD): Create SSDs for any chemical based on 1,000+ species, far exceeding the data available from traditional testing.

- Chemical Hazard Distributions (CHD): A new format showing the distribution of a chemical's hazard across all tested species [7].

Diagram 2: Regulatory QSAR framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in QSAR Development |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for batch chemical structures [9]. |

| KNIME | Workflow Platform | Provides an open-source, graphical environment for building and automating complex QSAR modeling workflows [12]. |

| OECD QSAR Assessment Framework (QAF) | Guidance Document | Provides structured criteria for evaluating the confidence in (Q)SAR models and predictions for regulatory purposes [11]. |

| libfm | Software Library | Implements factorization machines for advanced pairwise learning tasks, such as predicting chemical-species interactions [7]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) | Methodological Concept | Defines the chemical space where a QSAR model is valid, a critical requirement for regulatory acceptance [10] [9]. |

The field of environmental chemical hazard assessment is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). The application of these technologies is experiencing exponential growth, reshaping how environmental chemicals are monitored and their hazards evaluated for human health and ecosystems [13]. This growth is characterized by a notable surge in publications, dominated by environmental science journals, with China and the United States leading research output [13]. The research landscape has evolved from modest annual publication numbers to a rapidly accelerating field, with output nearly doubling from 2020 to 2021 and reaching hundreds of publications annually [13]. This expansion reflects a broader shift within toxicology from an empirical science to a data-rich discipline ripe for AI integration, enabling the analysis of complex, high-dimensional datasets that characterize modern chemical research [13]. Within this landscape, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, enhanced by ML, has emerged as a particularly powerful development for predicting the toxicological or pharmacological activities of chemicals based on their structural information [14].

Quantitative Landscape Analysis

Publication Growth and Geographic Distribution

Systematic analysis of the research landscape reveals distinct patterns in publication growth and geographic contributions. A bibliometric analysis of 3,150 peer-reviewed articles from the Web of Science Core Collection demonstrates an exponential publication surge from 2015 onward [13]. Until 2015, annual publication output remained modest with fewer than 25 papers per year, indicating limited engagement from research institutions [13]. A notable shift occurred in 2020, when publications rose sharply to 179, nearly doubling to 301 in 2021, and exceeding 719 publications in 2024 [13]. This trajectory highlights the field's accelerating momentum and growing global interest.

The research contribution spans 4,254 institutions across 94 countries [13]. The table below summarizes the contributions of the top 10 countries, indicating both publication volume and collaborative intensity through Total Link Strength (TLS).

Table 1: Top 10 Contributing Countries to ML in Environmental Chemical Research

| Country | Number of Publications | Total Link Strength (TLS) |

|---|---|---|

| People's Republic of China | 1,130 | 693 |

| United States | 863 | 734 |

| India | 255 | Information missing |

| Germany | 232 | Information missing |

| England | 229 | Information missing |

| Other contributing countries | Smaller proportions | Information missing |

Source: Adapted from [13]

At the institutional level, the Chinese Academy of Sciences leads with 174 publications over the past decade, followed by the United States Department of Energy with 113 publications [13].

Thematic Research Clusters and Methodological Trends

Co-citation and co-occurrence analyses have identified eight major thematic clusters within the research landscape [13]. These clusters are centered on:

- ML model development

- Water quality prediction

- Quantitative structure-activity applications

- Per-/polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

- Risk assessment applications

Among algorithms, XGBoost and random forests emerge as the most frequently cited models [13]. A distinct risk assessment cluster indicates the migration of these tools toward dose-response and regulatory applications, reflecting the field's evolving maturity [13].

Table 2: Prominent ML Algorithms and Their Applications in Environmental Hazard Assessment

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) | QSAR models for microplastic cytotoxicity prediction [15]; Aquatic toxicity prediction [16] | Superior prediction performance; handles complex non-linear relationships [15] |

| Random Forests | Predicting toxicity endpoints; identifying molecular fragments impacting nuclear receptors [16] | Robust performance; can be combined with explainable AI techniques [16] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Prediction of specific toxicity endpoints [17] | Effective for classification tasks |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) / Deep Learning | Identification of lung surfactant inhibitors [16]; Multi-modal toxicity prediction [17] | Capable of learning complex hierarchical feature representations |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) | Processing molecular structure images in multi-modal frameworks [17] | Advanced architecture for image-based feature extraction |

Application Notes: Advanced ML Approaches in Hazard Assessment

Direct Toxicity Classification Strategy

Conventional QSAR approaches typically predict specific toxicity values (e.g., LC50) before classifying chemicals into hazard categories. Researchers have developed an innovative alternative that skips the explicit toxicity value prediction step altogether [18]. This approach uses machine learning for direct classification of chemicals into predefined toxicity categories based on molecular descriptors [18].

Experimental Protocol: Direct Classification Workflow

- Data Collection: Compile experimental acute toxicity data (e.g., 96h LC50 values for fish toxicity).

- Category Definition: Define toxicity categories according to regulatory systems (e.g., Globally Harmonized System).

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors for each chemical.

- Model Training: Train ML models to directly map molecular descriptors to toxicity categories.

- Validation: Validate model performance using hold-out test sets.

This strategy demonstrated a fivefold decrease in incorrect categorization compared to conventional QSAR regression models and explained approximately 80% of variance in test set data [18].

Multimodal Deep Learning for Toxicity Prediction

Advanced frameworks now integrate multiple data modalities to enhance prediction accuracy. One approach combines chemical property data with 2D molecular structure images using a Vision Transformer (ViT) for image-based features and a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) for numerical data [17]. A joint fusion mechanism effectively combines these features, significantly improving predictive performance for multi-label toxicity classification [17].

Experimental Protocol: Multimodal Framework Implementation

- Data Curation:

- Collect molecular structure images from databases (e.g., PubChem, eChemPortal).

- Compile corresponding chemical property data (numerical and categorical features).

- Image Processing:

- Utilize a pre-trained Vision Transformer (ViT-Base/16) fine-tuned on molecular structures.

- Extract 128-dimensional feature vectors from molecular images.

- Tabular Data Processing:

- Process chemical property data using a Multi-Layer Perceptron.

- Generate 128-dimensional feature vectors from numerical data.

- Feature Fusion:

- Concatenate image and tabular feature vectors to create a 256-dimensional fused vector.

- Model Training & Validation:

- Train the integrated model for multi-label toxicity prediction.

- Evaluate using accuracy, F1-score, and Pearson Correlation Coefficient.

This approach has demonstrated an accuracy of 0.872, F1-score of 0.86, and PCC of 0.9192 [17].

ML-Driven QSAR for Microplastics Toxicity Assessment

The prediction of microplastics (MPs) cytotoxicity represents a specialized application of ML-driven QSAR. Research has focused on five common MPs in the environment: polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [15].

Experimental Protocol: MPs Toxicity Prediction

- Material Characterization:

- Analyze MPs morphology using scanning electron microscopy.

- Measure Z-average size and zeta potential in suspension.

- Cytotoxicity Testing:

- Expose BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cells to MPs.

- Assess cell viability using CCK-8 assay.

- Descriptor Selection:

- Utilize physical-chemical descriptors: Z-average size, polymer type, zeta potential, shape, exposure concentration.

- Model Development:

- Apply six ML algorithms: MLR, RF, KNN, SVM, GBDT, XGB.

- Compare model performance using training and test set R² values.

- Feature Importance Analysis:

- Apply Embedded Feature Importance, Recursive Feature Elimination, and SHapley Additive exPlanations.

- Identify critical features dominating toxicity prediction.

In this application, the XGBoost model showed the best prediction ability with R² values of 0.9876 (training) and 0.9286 (test), with particle size consistently identified as the most critical feature affecting toxicity prediction [15].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Direct Toxicity Classification Strategy

Direct Toxicity Classification

Multimodal Deep Learning Framework

Multimodal Deep Learning Framework

ML-QSAR for Microplastics

ML-QSAR for Microplastics Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for ML in Environmental Hazard Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| BEAS-2B Cell Line | In vitro model for respiratory toxicity testing | Assessing cytotoxicity of inhaled microplastics and environmental pollutants [15] |

| Microplastics Standards | Reference materials for toxicity testing | PE, PP, PS, PVC, PET standards for controlled exposure studies [15] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representation of chemical structures | Feature input for QSAR and direct classification models [18] |

| Toxicity Databases | Repositories of experimental toxicity data | PubChem, ChEMBL, ACToR, Tox21/ToxCast for model training [19] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explainable AI method for model interpretation | Identifying key features (e.g., particle size) in microplastics toxicity [15] |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) | Deep learning architecture for image processing | Analyzing 2D molecular structure images in multimodal learning [17] |

| Federated Learning Framework | Privacy-preserving distributed ML approach | Training models on sensitive data without centralization [19] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The research landscape continues to evolve with several emerging trends. Explainable AI (XAI) is gaining prominence to interpret "black box" models, improving transparency for regulatory and public health decision-making [16]. Techniques like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) are being combined with Random Forest classifiers to identify molecular fragments impacting specific nuclear receptors [16]. Large Language Models (LLMs) fine-tuned on toxicological data show potential for automating data extraction, organization, and summarization, reducing manpower and time while maintaining regulatory compliance [19]. Research is also expanding to include mixture toxicity prediction [20] [16], life-cycle environmental impact assessment [21], and the integration of omics technologies for mechanistic insights [22]. These advancements collectively address critical gaps in chemical coverage and health integration while fostering international collaboration to translate ML advances into actionable chemical risk assessments [13].

Thyroid Hormone System Disruption (THSD) represents a critical endpoint in the ecological risk assessment of environmental chemicals. The thyroid hormone (TH) system is essential for regulating growth, development, and metabolism in aquatic vertebrates, and its disruption by chemicals can lead to severe population-relevant adverse outcomes [23]. This application note details the experimental and computational methodologies for assessing chemical-induced THSD in aquatic species, framed within the broader context of developing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models for environmental hazard assessment. The integration of in vivo assays and New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), particularly QSARs, is crucial for advancing the identification of Thyroid Hormone System Disrupting Compounds (THSDCs) while reducing reliance on animal testing [4] [23] [5].

Key Endpoints and Biomarkers for THSD Assessment

The assessment of THSD relies on measuring specific molecular, biochemical, and morphological endpoints along the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis. The following table synthesizes the critical endpoints identified from recent studies, particularly in zebrafish embryos and other fish models.

Table 1: Critical Endpoints for Assessing Thyroid Hormone System Disruption in Aquatic Species

| Endpoint Category | Specific Biomarker/Parameter | Measurement Technique | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Levels | Whole-body Thyroxine (T4) and Triiodothyronine (T3) levels | ELISA, RIA | Direct measure of systemic thyroid hormone status [24] [25] |

| Gene Expression | DEIO1, DEIO2, TRα, TTR, UGT1ab | qPCR, Transcriptomics | Key genes in HPT axis regulating hormone activation, transport, and metabolism [24] [25] |

| Receptor Binding | Binding affinity to TSHβ, TR | Molecular Docking | Predicts direct interference with thyroid hormone receptors and synthesis [24] [25] |

| Oxidative Stress | SOD, CAT, GSH, MDA levels, CYP1A1 activity | Enzymatic assays, Spectrophotometry | Indicates secondary toxicity pathways linked to endocrine disruption [24] [25] |

| Developmental Toxicity | Melanin deposition, locomotor activity, developmental abnormalities | Morphological analysis, behavioral assays (e.g., larval locomotion) | Functional adverse outcomes resulting from TH disruption [24] [25] |

| Immunotoxicity | Immune-related gene expression, pathogen resistance challenge | qPCR, survival assays | Connects TH disruption to impaired immune function and reduced fitness [26] |

Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Assessment in Zebrafish Embryos

The following protocol details a standardized methodology for assessing THSD and associated multi-toxicity endpoints in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos, based on the study of the fungicide hymexazol [24] [25].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for THSD Assessment

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Zebrafish Embryos | Model organism for vertebrate development and toxicity testing. | Wild-type AB or TU strain, 2-4 hours post-fertilization (hpf). |

| Test Chemical | The substance under investigation for thyroid-disrupting potential. | Hymexazol (CAS: 10004-44-1) or other environmental chemical. Prepare stock solution in solvent. |

| E3 Medium | Standard medium for maintaining zebrafish embryos. | 5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl₂, 0.33 mM MgSO₄, pH 7.2-7.4. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Vehicle solvent for poorly water-soluble chemicals. | High-purity grade. Final concentration in test medium should not exceed 0.1% (v/v). |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from pooled embryos/larvae. | e.g., TRIzol reagent or commercial spin-column kits. |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA for qPCR analysis. | Kits containing reverse transcriptase, random hexamers, and dNTPs. |

| qPCR Master Mix | SYBR Green or TaqMan-based mix for quantitative gene expression analysis. | Includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye. |

| ELISA Kits | Quantification of whole-body T3 and T4 hormone levels. | Species-specific or broad-range kits validated for zebrafish. |

| SOD/CAT/GSH Assay Kits | Colorimetric or fluorometric measurement of oxidative stress markers. | Commercial kits based on standard enzymatic methods. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Embryo Collection and Exposure:

- Collect healthy zebrafish embryos at the 2-4 cell stage (2-4 hpf). Manually clean and stage the embryos under a stereomicroscope.

- Prepare a concentration range of the test chemical (e.g., hymexazol) by serially diluting the stock solution in DMSO into E3 medium. Include a solvent control (0.1% DMSO v/v) and a blank control (E3 medium only).

- Randomly distribute 20-30 embryos per well into 24-well plates, with each well containing 2 mL of the respective test solution or control.

- Incubate the plates at 28 ± 0.5°C with a 14h:10h light:dark cycle until 120 hpf. Renew the test solutions daily to ensure stable chemical concentration.

- Observe and record mortality and gross morphological malformations (e.g., pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, spinal curvature) daily.

Sampling and Homogenization:

- At 120 hpf, randomly pool 30-50 larvae from each treatment group.

- For biochemical and molecular analyses, snap-freeze the pools in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. For hormone analysis, whole-body homogenates are prepared in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) using a motorized homogenizer. The homogenate is then centrifuged (e.g., 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), and the supernatant is aliquoted for subsequent assays.

Endpoint Measurement:

- Thyroid Hormone Quantification: Use commercial ELISA kits to measure T3 and T4 levels in the supernatant according to the manufacturer's instructions. Measure absorbance using a microplate reader.

- Gene Expression Analysis (qPCR):

- Extract total RNA from pooled larvae using a commercial kit. Assess RNA purity and integrity.

- Synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA using a reverse transcription kit.

- Perform qPCR reactions in triplicate using a master mix and gene-specific primers for target genes (e.g., DEIO1, DEIO2, TRα, TTR, UGT1ab, MITFB, TYR) and reference genes (e.g., β-actin, gapdh).

- Analyze data using the comparative 2^–ΔΔCq method to determine relative gene expression.

- Oxidative Stress Biomarkers: Use commercial kits to measure the activity of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT), and the levels of Glutathione (GSH) and Malondialdehyde (MDA) in the supernatant, following the provided protocols.

- Behavioral Assessment: At 120 hpf, transfer individual larvae to a 96-well plate. After an acclimation period, record larval movement (total distance traveled, activity duration) using an automated video-tracking system.

Molecular Docking (In Silico Supplement):

- To predict the binding affinity of the test chemical to key proteins like TSHβ, retrieve the 3D crystal structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Prepare the protein and ligand (test chemical) structures using appropriate software (e.g., AutoDock Tools), including adding hydrogens and assigning charges.

- Define a grid box encompassing the active site of the protein.

- Perform docking simulations using software like AutoDock Vina.

- Analyze the resulting docking poses and binding energies to evaluate the potential for direct molecular interaction.

QSAR Model Development for Predicting THSD

The adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework provides a structured basis for developing QSAR models that predict molecular initiating events (MIEs) leading to THSD [4] [26]. A simplified AOP links THSD to reduced pathogen resistance in fish, demonstrating population-relevant outcomes [26].

Data Curation and Endpoint Selection

For QSAR modeling, data from standardized in vivo tests, such as the fish endocrine screening assays [23] or the zebrafish embryo multi-endpoint assay described above, serve as the primary source of experimental training data. The critical endpoints from Table 1, particularly the binding affinity to key targets (MIE) and the significant downregulation of genes like DEIO2, are suitable endpoints for model development [24] [4] [25].

Model Building and Validation

A recent review of 86 QSAR models for THSD highlights the importance of the Applicability Domain (AD) and model transparency [4]. The following workflow outlines the core process for developing a regulatory-grade QSAR model.

Table 3: Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches for THSD Prediction

| Modeling Aspect | Options and Best Practices | Considerations for THSD |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Classes | Diverse training sets covering pesticides, industrial chemicals, PFAS [27] [13] | Avoid extrapolation outside the model's Applicability Domain (AD) [4] [28] |

| Molecular Descriptors | 2D/3D molecular descriptors, fingerprints | Selection should be mechanistically interpretable related to thyroid pathways [4] |

| Algorithms | XGBoost, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM) [13] | XGBoost and Random Forests are most cited for environmental chemical ML [13] |

| Validation | Internal (cross-validation) and external validation | Essential for assessing predictive power and regulatory acceptance [4] [28] |

| Applicability Domain (AD) | Defining the chemical space where the model is reliable | A critical component of the new OECD QSAR Assessment Framework (QAF) [29] |

| Endpoint | Molecular initiating events (MIEs) in the AOP [4] | e.g., Binding to TH receptor, inhibition of thyroid peroxidase |

Integrated Testing Strategy and Regulatory Context

A key recommendation in the field is to integrate data from various sources within a weight-of-evidence approach. The OECD Conceptual Framework outlines a tiered testing strategy from Level 1 (QSARs and existing data) to Level 5 (life-cycle studies) [23]. The experimental and computational protocols described herein provide critical data for the lower tiers of this framework, enabling prioritization for higher-tier testing.

The recent introduction of the OECD QSAR Assessment Framework (QAF) provides a transparent and consistent checklist for regulators and industry to evaluate QSAR results, thereby boosting confidence in their use for meeting regulatory requirements under programs like REACH and reducing animal testing [29]. While familiarity and use of NAMs like QSARs are high, barriers remain for the adoption of more complex methodologies, underscoring the need for robust and well-documented protocols [5].

The integration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modelling with the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework represents a paradigm shift in modern toxicology and environmental hazard assessment [30]. This synergy offers a powerful, mechanistic-based strategy for predicting the toxicological effects of chemicals while reducing reliance on traditional animal testing [31] [32]. QSAR models predict the biological activity of chemicals based on their structural features, quantified as molecular descriptors [33]. When focused on predicting molecular initiating events (MIEs) within AOPs, these models provide a chemically agnostic method to prioritize compounds for further experimental evaluation, enabling significant resource savings in safety assessment [31] [34]. This Application Note details the essential concepts, descriptors, and protocols for developing QSAR models within an AOP context for environmental chemical hazard assessment.

Core Concepts

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

QSAR is a computational methodology that establishes a quantitative relationship between a chemical's structure, described by molecular descriptors, and its biological activity or toxicity [33]. The fundamental principle is that the biological activity of a new, untested chemical can be inferred from the known activities of structurally similar compounds.

A robust QSAR model intended for regulatory use must adhere to the OECD Principles, which require:

- A defined endpoint

- An unambiguous algorithm

- A defined domain of applicability

- Appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity

- A mechanistic interpretation, if possible [33]

Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs)

An AOP is a conceptual framework that describes a sequential chain of causally linked events at different biological levels of organization, beginning with a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) and leading to an Adverse Outcome (AO) of regulatory relevance [31] [32]. The MIE is the initial interaction of a chemical with a biomolecule, which is followed by a series of intermediate Key Events (KEs), connected by Key Event Relationships (KERs) [35]. The AOP framework is chemically agnostic, meaning a single pathway can describe the potential toxicity of multiple chemicals capable of interacting with the same MIEs [31]. This makes AOPs exceptionally valuable for structuring and contextualizing QSAR predictions.

Table 1: Core Components of an Adverse Outcome Pathway

| Component | Description | Role in QSAR Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) | The initial chemical-biological interaction (e.g., binding to a protein, inhibition of an enzyme). | Primary endpoint for QSAR model development. |

| Key Event (KE) | A measurable change in biological state that is essential for progression to the adverse outcome. | Can serve as a secondary endpoint for intermediate QSAR models. |

| Key Event Relationship (KER) | The causal or correlative link between two Key Events. | Informs the assembly of multiple QSAR models into a predictive network. |

| Adverse Outcome (AO) | The toxic effect of regulatory concern at the individual or population level. | The ultimate hazard being predicted through the integrated model. |

Integrating QSAR and AOPs

Integrating QSAR with AOPs involves developing computational models to predict chemical activity against specific MIEs or KEs [30]. This approach simplifies complex systemic toxicities into more manageable, single-target predictions that QSAR models can effectively capture [31]. For instance, instead of building a single, complex model to predict "liver steatosis," one would develop individual QSAR models for MIEs like "aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonism" or "peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation," which are known initiators in the steatosis AOP network [31]. This strategy provides a mechanistically grounded context for QSAR predictions, significantly enhancing their interpretability and utility in risk assessment [34].

Molecular Descriptors in QSAR

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of a molecule's structural and physicochemical properties that serve as the independent variables in a QSAR model [33]. The choice of descriptor is critical as it determines the model's mechanistic interpretability and predictive capability.

Table 2: Key Categories and Examples of Molecular Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Description | Example Descriptors | Mechanistic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical | Describe atomic and molecular properties arising from the structure. | LogP (lipophilicity), pKa, water solubility [33]. |

LogP influences passive cellular absorption and bioavailability. High LogP may indicate potential for bioaccumulation. |

| Electronical | Describe the electronic distribution within a molecule, influencing interactions with biological targets. | Hammett constant (σ), dipole moment, HOMO/LUMO energies [33]. | The Hammett constant predicts how substituents affect the electron density of a reaction center, relevant for binding to enzymes or receptors. |

| Topological | Describe the molecular structure based on atom connectivity, without 3D coordinates. | Molecular weight, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds, molecular connectivity indices [33]. | Used in "rule-based" filters like Lipinski's Rule of Five to assess drug-likeness and potential oral bioavailability [33]. |

| Structural Fragments | Represent the presence or absence of specific functional groups or substructures. | Molecular fingerprints, presence of aniline, nitro, or carbonyl groups. | Can serve as structural alerts for specific toxicities (e.g., anilines for methemoglobinemia). |

| Geometrical | Describe the 3D shape and size of a molecule. | Molecular volume, surface area, polar surface area (PSA) [33]. | Polar Surface Area (PSA) is a key predictor for a compound's ability to permeate cell membranes and cross the blood-brain barrier. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a QSAR Model for an MIE

This protocol outlines the steps for building a robust classification QSAR model to predict activity against a specific MIE target, such as a receptor or enzyme.

1. Define the Endpoint and Collect Bioactivity Data

- Endpoint Definition: Clearly define the MIE and the biological activity (e.g., "PPAR-γ inactivation," "TLR4 activation") [35].

- Data Source: Manually extract relevant bioactivity data from public databases such as ChEMBL [31] or PubChem [35]. Prioritize data for Homo sapiens where available.

- Activity Threshold: Convert continuous bioactivity values (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀) into a binary classification (active/inactive). A common threshold is 10,000 nM (or 10 µM); compounds with activity < 10,000 nM are classified as "active," while those ≥ 10,000 nM are "inactive" [31].

2. Curate and Prepare the Dataset

- Curation: Remove duplicates and records flagged with data validity issues [31].

- Standardization: Standardize chemical structures (e.g., neutralize charges, remove salts) and generate canonical representations (e.g., SMILES).

- Calculate Descriptors: Use cheminformatics software (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL) to calculate a wide range of molecular descriptors for all compounds.

- Data Splitting: Split the curated dataset into a training set (∼80%) for model building and a hold-out test set (∼20%) for final validation.

3. Model Building and Validation

- Address Class Imbalance: If the dataset is imbalanced, apply techniques like the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to the training set to generate synthetic samples for the minority class [30].

- Algorithm Selection: Train multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, Gradient Boosting) on the training data [31] [30].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize model parameters using cross-validation on the training set.

- Model Validation: Assess the performance of the optimized models on the hold-out test set using metrics such as Balanced Accuracy (BA), sensitivity, and specificity. A BA > 0.80 is indicative of high predictive performance [31] [30].

- Define Applicability Domain (AD): Establish the chemical space region where the model can make reliable predictions. Methods like leverage or distance-based approaches can be used.

4. Model Application and Interpretation

- Screening: Use the validated model to screen new environmental chemicals for potential MIE activity.

- Interpretation: Analyze the importance of molecular descriptors in the model to gain mechanistic insight into the structural features associated with the MIE.

Protocol 2: Contextualizing QSAR Predictions Using an AOP Network

This protocol describes how to use AOP knowledge to frame and interpret QSAR predictions for a higher-level hazard, such as pulmonary fibrosis or thyroid hormone system disruption [35] [36].

1. Identify Relevant AOPs

- Consult the AOP-Wiki (https://aopwiki.org/) to identify established AOPs or AOP networks leading to the adverse outcome of interest (e.g., AOP 347 for pulmonary fibrosis) [35].

- Map all MIEs and KEs within the network.

2. Develop or Curate QSAR Models for Key MIEs

- For each critical MIE in the AOP network (e.g., PPAR-γ inactivation and TLR4 activation in AOP 347), either develop a novel QSAR model following Protocol 1 or select existing, validated models from the literature [35].

3. Apply the QSAR Battery for Screening

- Screen the chemical(s) of interest against each QSAR model in the battery.

- Record the prediction (active/inactive) and the associated reliability measure (e.g., within the applicability domain).

4. Conduct a Weight-of-Evidence Assessment

- Integrate the predictions from all relevant QSAR models.

- A chemical predicted to active multiple MIEs within a shared AOP network is considered to have a higher potential to cause the downstream adverse outcome [34] [35].

- This contextualized prediction provides a more robust and mechanistically grounded hazard prioritization than a single model output.

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

QSAR Model Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in developing a QSAR model for an MIE.

Diagram Title: QSAR Model Development Workflow

AOP Contextualization of QSAR Predictions

This diagram shows how multiple QSAR models, each predicting an MIE, are integrated within an AOP network to forecast an adverse outcome.

Diagram Title: QSAR Model Integration in an AOP Network

Table 3: Key Resources for QSAR and AOP Research

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. It is a primary source of high-quality bioactivity data for MIE target modelling [31]. |

| AOP-Wiki | Knowledgebase | The central repository for collaborative AOP development, providing detailed information on MIEs, KEs, KERs, and supporting evidence [31]. |

| PubChem BioAssay | Database | A public repository of biological assays, providing chemical structures and bioactivity data for developing and testing QSAR models [35]. |

| RDKit | Software | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprinting, and molecular standardization in QSAR workflows. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software | A software application designed to help users group chemicals into categories and fill data gaps by (Q)SAR approaches, with integrated AOP knowledge. |

| SMOTE | Algorithm | A synthetic data generation technique used to balance imbalanced training datasets in machine learning, improving model performance for minority classes [30]. |

Building Predictive Models: Advanced Techniques and Practical Applications

The application of machine learning (ML) in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling has revolutionized the approach to environmental chemical hazard assessment. By leveraging computational power and algorithmic sophistication, researchers can now predict the potential toxicity and environmental impact of chemicals with increasing accuracy, reducing reliance on resource-intensive animal testing [4]. This evolution from classical statistical methods to advanced ML algorithms enables the handling of complex, high-dimensional chemical datasets, capturing nonlinear relationships that traditional linear models cannot adequately address [37].

Within environmental hazard assessment, ML-based QSAR models serve as crucial New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that support the principles of green toxicology by minimizing experimental testing. Regulatory agencies like the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) acknowledge properly validated QSAR models as suitable for fulfilling information requirements for physicochemical properties and certain environmental toxicity endpoints [38]. The ongoing development of these models aligns with the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework, allowing researchers to link molecular initiating events to adverse effects at higher levels of biological organization [4].

Machine Learning Algorithm Portfolio for QSAR Modeling

Algorithm Comparison and Performance Metrics

Multiple machine learning algorithms have been successfully applied to QSAR modeling, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. The selection of an appropriate algorithm depends on factors including dataset size, descriptor dimensionality, required interpretability, and the specific prediction task (regression or classification).

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms Used in QSAR Modeling

| Algorithm | Best Use Cases | Key Advantages | Performance Examples | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Large, noisy datasets, feature importance analysis [39] [40] | Robust to outliers, built-in feature selection, handles collinearity well [37] | Adj. R²test = 0.955 for nano-mixture toxicity prediction [39] | Medium (feature importance) |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Complex nonlinear relationships, pattern recognition [41] | High predictive accuracy, learns intricate patterns | 96% accuracy, F1=0.97 for lung surfactant inhibition [41] | Low (black-box) |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | High-dimensional data with limited samples [41] [37] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile kernels | Strong performance with lower computation costs [41] | Medium |

| Logistic Regression | Linear classification, baseline modeling [41] | Computational efficiency, probabilistic output, simple implementation | Good performance with low computation costs [41] | High |

| Gradient-Boosted Trees (GBT) | Predictive accuracy competitions, structured data [41] | High predictive power, handles mixed data types | Evaluated for lung surfactant inhibition [41] | Medium |

Advanced and Emerging Approaches

Beyond the classical ML algorithms, the field of QSAR modeling is witnessing rapid advancement through sophisticated learning paradigms:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent molecules as graph structures, directly learning from atomic connections and molecular topology. These deep descriptors capture hierarchical chemical features without manual engineering, offering superior performance for complex endpoint prediction [37].

Prior-Data Fitted Networks (PFNs) leverage transformer architectures pretrained on extensive tabular datasets, enabling rapid predictions without extensive hyperparameter tuning. This approach is particularly valuable for small dataset scenarios common in specialized toxicity endpoints [41].

Meta-Learning approaches allow models to leverage knowledge across multiple related prediction tasks, improving performance for endpoints with limited training data. While not explicitly detailed in the search results, this represents the natural evolution toward more sophisticated AI-integrated QSAR modeling [37].

Application Notes: Implementing ML-QSAR for Specific Environmental Hazards

Thyroid Hormone System Disruption Prediction

Thyroid hormone (TH) system disruption represents a significant concern in environmental toxicology due to the critical role of thyroid hormones in metabolism, growth, and brain development [4]. A recent review identified 86 different QSAR models developed between 2010-2024 specifically for predicting TH system disruption, focusing primarily on molecular initiating events (MIEs) within the adverse outcome pathway framework [4].

Protocol 1: Random Forest Implementation for TH Disruption Prediction

Data Compilation: Collect known TH-disrupting chemicals from dedicated databases such as the THSDR (Thyroid Hormone System Disruptor Database) or specialized literature compilations.

Descriptor Calculation: Generate molecular descriptors using tools like RDKit or Mordred, focusing particularly on descriptors related to endocrine activity (e.g., structural alerts for thyroid receptor binding, transporter inhibition potential) [4] [41].

Model Training: Implement Random Forest regression or classification using scikit-learn with key hyperparameters:

Validation: Apply rigorous k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold) and external validation with hold-out test sets to ensure model robustness and generalizability [40].

Applicability Domain Assessment: Define the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions using distance-based methods or leverage approaches [4].

Nano-Mixture Toxicity Prediction to Daphnia magna

The unique challenge of predicting mixture toxicity, particularly for engineered nanomaterials like TiO₂ nanoparticles, requires specialized modeling approaches that account for interactions between components [39].

Protocol 2: Nano-Mixture QSAR Development

Mixture Descriptor Formulation: Create mixture descriptors (Dmix) that combine quantum chemical descriptors of individual components using mathematical operations (e.g., arithmetic means, weighted sums) based on concentration ratios [39].

Algorithm Selection: Employ Random Forest as the primary algorithm due to its demonstrated success with mixture datasets (achieving Adj.R²test = 0.955 ± 0.003 for TiO₂-based nano-mixtures) [39].

Web Application Deployment: Implement trained models in user-friendly web interfaces using R Shiny or Python Flask to enable accessibility for environmental risk assessors without programming expertise [39].

Validation with Experimental Data: Compare predictions against experimental EC50 values for Daphnia magna immobilization to ensure ecological relevance [39].

Placental Transfer Prediction for Environmental Chemicals

Assessing the transfer of environmental chemicals across the placenta is critical for understanding developmental toxicity risks. ML-QSAR models offer a non-invasive approach to predict this important exposure pathway [42].

Protocol 3: Placental Transfer Modeling

Data Curation: Compile cord to maternal serum concentration ratios from scientific literature, ensuring consistent measurement protocols and chemical identification [42].

Descriptor Selection: Calculate 214+ molecular descriptors using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software, emphasizing physicochemical properties relevant to placental transfer (e.g., log P, molecular weight, hydrogen bonding capacity) [42].

Model Building: Compare multiple algorithms including Partial Least Squares (PLS) and SuperLearner, with PLS demonstrating superior performance (external R² = 0.73) for this specific endpoint [42].

Applicability Domain Verification: Use the Applicability Domain Tool v1.0 or similar software to ensure predictions fall within the validated chemical space [42].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized QSAR Modeling Workflow

The development of reliable ML-QSAR models follows a systematic workflow that aligns with OECD validation principles to ensure regulatory acceptance and scientific robustness [40].

Model Validation and Documentation Protocol

Comprehensive validation and documentation are essential for regulatory acceptance of ML-QSAR models, particularly following OECD guidelines [40] [38].

Principle 0: Data Characterization

- Data Quality Assessment: Implement rigorous curation of chemical structures and associated biological data, resolving identifier inconsistencies and removing duplicates [40].

- Structural Verification: Verify chemical structures through cyclic conversion between molecular file formats and InChI keys to ensure consistency [40].

- Data Provenance: Document original data sources, measurement conditions, and any normalization procedures applied [40].

Defined Endpoint (OECD Principle 1)

Unambiguous Algorithm (OECD Principle 2)

Applicability Domain (OECD Principle 3)

Validation Metrics (OECD Principle 4)

Mechanistic Interpretation (OECD Principle 5)

Successful implementation of ML-QSAR models requires access to specialized software tools, databases, and computational resources that facilitate model development, validation, and deployment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML-QSAR

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Generation | RDKit, Mordred, PaDEL, DRAGON [41] [37] | Calculate molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Open-source & Commercial |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn, XGBoost, PyTorch, TensorFlow [41] [37] | Implement ML algorithms for model development | Open-source |

| Model Interpretability | SHAP, LIME [37] | Explain model predictions and identify important features | Open-source |

| Chemical Databases | eChemPortal, AqSolDB, DSSTox [40] | Source chemical structures and associated property/toxicity data | Public & Regulatory |

| Validation Tools | Applicability Domain Tool, QSARINS [42] [40] | Assess model applicability domain and validation metrics | Open-source & Commercial |

| Deployment Platforms | R Shiny, Python Flask, KNIME [39] [37] | Create user-friendly interfaces for model deployment | Open-source |

The integration of machine learning algorithms into QSAR modeling represents a paradigm shift in environmental chemical hazard assessment, enabling more accurate, efficient, and ethical evaluation of potential hazards. From robust ensemble methods like Random Forests to advanced deep learning approaches, these computational tools provide powerful capabilities for predicting diverse toxicity endpoints while reducing reliance on animal testing.

Successful implementation requires careful attention to OECD validation principles, comprehensive documentation, and clear definition of applicability domains to ensure regulatory acceptance. As the field continues to evolve, emerging approaches including graph neural networks, meta-learning, and improved interpretability methods will further enhance our ability to assess chemical hazards computationally, ultimately supporting safer chemical design and more efficient risk assessment paradigms.

Leveraging Meta-Learning for Knowledge Transfer Across Species and Endpoints

In the field of environmental chemical hazard assessment, the necessity to predict toxicological effects for thousands of chemicals across diverse biological species presents a fundamental challenge, exacerbated by stringent ethical policies aiming to reduce animal testing. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models have emerged as crucial in silico tools for addressing these data sparsity issues. However, building robust, species-specific models for many ecologically relevant organisms remains difficult due to the inherently low-resource nature of available toxicity data, where many tasks involve few associated compounds [43]. Meta-learning, a subfield of artificial intelligence dedicated to "learning to learn," offers a transformative approach by enabling knowledge sharing across related prediction tasks [43] [44]. This framework allows models to leverage information from data-rich species to improve predictive performance for data-poor species, thereby accelerating chemical safety assessment and supporting the goals of regulatory programs like the European Union's Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) [43].

Meta-Learning Paradigms in Ecotoxicology

Core Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Meta-learning techniques facilitate knowledge transfer across related toxicity prediction tasks, each typically corresponding to a different species or toxicological endpoint. Several state-of-the-art approaches have been benchmarked for aquatic toxicity modeling, demonstrating significant advantages over traditional single-task learning [43].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Meta-Learning Approaches for Aquatic Toxicity QSAR Modeling

| Meta-Learning Approach | Key Mechanism | Recommended Use Case | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Task Learning (MTL) | Jointly learns multiple tasks using a single model, enabling knowledge sharing across tasks [43]. | Low-resource settings with multiple related species [43]. | Multi-task random forest matched or exceeded other approaches and robustly produced good results [43] [45]. |

| Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) | Learns optimal initial model weights that can be rapidly adapted to new tasks with few gradient steps [43] [44]. | Rapid adaptation to new, data-scarce species or endpoints [44]. | Effective when source and target tasks show significant similarity; performance can be compromised by negative transfer [44]. |

| Fine-Tuning | Pre-trains a model on all available source tasks, then fine-tunes the model on a specific target task [43]. | Scenarios with a sufficiently large and relevant source domain [43]. | Established knowledge-sharing technique that generally outperforms single-task approaches [43]. |

| Transformational Machine Learning | Learns multi-task-specific compound representations that encapsulate general consensus on biological activity [43]. | Integrating diverse activity data to create enriched molecular representations. | Provides an alternative knowledge-sharing mechanism; performance benchmarked against other methods [43]. |

These meta-learning strategies directly address the "low-resource" challenge prevalent in ecotoxicology, where data for many species is sparse. Empirical benchmarks demonstrate that established knowledge-sharing techniques consistently outperform single-task modeling approaches [43].

Mitigating Negative Transfer

A significant challenge in transfer learning, including meta-learning applications, is negative transfer—the phenomenon where knowledge transfer from a source domain decreases performance in the target domain [44]. This typically occurs when source and target tasks lack sufficient similarity. A novel meta-learning framework has been proposed to algorithmically balance this issue by identifying an optimal subset of source domain training instances and determining weight initializations for base models [44]. This approach combines task and sample information with a unique meta-objective: optimizing the generalization potential of a pre-trained model in the target domain. In proof-of-concept applications predicting protein kinase inhibitors, this method resulted in statistically significant increases in model performance and effective control of negative transfer [44].

Application Notes: Protocol for Cross-Species Aquatic Toxicity Modeling

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Task Meta-Learning

The following protocol outlines the end-to-end process for developing a meta-QSAR model for predicting aquatic toxicity across multiple species, based on benchmarked methodologies [43].

Detailed Protocol Steps

Data Collection and Curation

- Data Source: Compile aquatic toxicity data from the ECOTOX knowledgebase, which contained 24,816 assays, 351 separate species, and 2,674 chemicals in a recent benchmark study [43].

- Curation Steps: Standardize molecular structures, remove duplicates, and aggregate multiple measurements for the same chemical-species pair using geometric means when appropriate [43] [44].

- Endpoint Harmonization: Focus on mortality-based toxicity endpoints (e.g., LC50, EC50) across exposure durations, while recording specific experimental conditions for each assay [43].

Molecular Representation

- Featurization: Generate Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP4) with a fixed size of 4,096 bits from canonical SMILES strings using cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit [44].

- Descriptor Alternatives: Consider additional molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, physicochemical) to enrich feature representation, though fingerprints have demonstrated strong performance [43].

Meta-Task Formulation

- Task Definition: Define each prediction task as estimating toxicity for a specific species [43].

- Train-Test Splitting: Implement a meta-learning split where species in the meta-test set are held out during meta-training to evaluate cross-species generalization [43] [46].

- Low-Resource Simulation: For robustness testing, artificially downsample data to simulate few-shot learning scenarios with limited assays per species [43].

Model Selection and Training

- Algorithm Choice: Based on empirical benchmarks, implement a Multi-Task Random Forest as the primary model, which has shown robust performance in low-resource aquatic toxicity settings [43] [45].

- Alternative Models: Consider multi-task neural networks or MAML for specific applications, though random forests provide a strong baseline [43].

- Training Regimen: For MAML, use an inner-loop learning rate of 0.01 and outer-loop rate of 0.001, with 5-10 gradient steps for adaptation to new species [44].

Validation and Applicability Domain

- Validation Strategy: Employ both internal (cross-validation) and external (hold-out set) validation following QSAR best practices [43].

- Applicability Domain: Assess model confidence by evaluating chemical similarity to training compounds, ensuring predictions fall within a defined chemical space [43] [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Meta-QSAR Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Source | Function in Meta-QSAR Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Databases | ECOTOX Knowledgebase [43] | Primary source of curated aquatic toxicity data across multiple species and endpoints. |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [44], BindingDB [44] | Sources of bioactivity data for pre-training or transfer learning applications. |

| Cheminformatics Tools | RDKit [44] | Open-source toolkit for molecular standardization, fingerprint generation, and descriptor calculation. |