Agricultural and Industrial Pollutants: Assessing Ecosystem Health Risks and Biomedical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of industrial discharges and agricultural runoff on ecosystem health, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development.

Agricultural and Industrial Pollutants: Assessing Ecosystem Health Risks and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of industrial discharges and agricultural runoff on ecosystem health, with a specific focus on implications for biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational science behind pollutant pathways and health effects, examines advanced methodological approaches for monitoring and risk assessment, discusses optimization strategies for pollution mitigation, and validates findings through comparative case studies and regulatory frameworks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the synthesis offers critical insights into the environmental origins of health risks and outlines future directions for interdisciplinary research.

Understanding the Contaminant Landscape: Sources, Pathways, and Direct Ecological Damage

Aquatic ecosystems worldwide face a mounting crisis from two interconnected classes of pollutants: agricultural nutrients and industrial toxins. These contaminants form a complex "pollution spectrum" that threatens freshwater and marine environments, biodiversity, and human health. Within the context of ecosystem health research, understanding this spectrum requires examining not only the distinct characteristics of each pollutant type but also their synergistic effects when they co-occur in environmental compartments. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers investigating the multifaceted impacts of these pollutants, with specific methodological protocols for quantifying exposure levels and biological effects.

The environmental burden from anthropogenic activities has created a scenario where many water bodies must simultaneously process excess nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) from agricultural runoff while dealing with persistent, bioaccumulative toxic substances from industrial discharges. This combination often triggers complex ecological cascades that challenge traditional single-stressor research models. This whitepaper establishes standardized approaches for characterizing this pollution spectrum, enabling more predictive assessments of ecosystem vulnerability and resilience.

Quantitative Profiling of Pollutant Classes

The Agricultural Nutrient Profile

Agricultural runoff represents a diffuse nonpoint source pollution characterized by high loads of nitrogen and phosphorus, which drive eutrophication in receiving waters. According to recent research, Illinois and Iowa are the greatest contributors of nutrients to the Gulf of Mexico, with nonpoint sources (primarily agriculture) contributing 80% of the nitrogen and approximately half of the phosphorus to rivers and streams [1]. This nutrient loading has created a persistent hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico measured at 6,334 square miles in 2024, with a historical maximum of 8,776 square miles recorded in 2017 [1].

The timing and form of nutrient application significantly impact runoff dynamics. Studies demonstrate that nitrate losses to tile drainage systems are substantially higher when nitrogen fertilizer is applied in fall rather than spring ahead of corn planting [1]. Surprisingly, research also indicates that soybean production aggravates nitrate losses through microbial decomposition of crop residues and soil organic matter when soil microbial communities exhaust easily accessible carbon sources [1].

Table 1: Agricultural Nutrient Pollutants and Ecosystem Impacts

| Pollutant Class | Primary Sources | Environmental Measurement | Ecosystem Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (Nitrates) | Synthetic fertilizers, manure, legume crops | 80% of nitrogen in IL rivers from nonpoint agricultural sources [1] | Gulf of Mexico dead zone (6,334 sq mi), algal blooms, hypoxia |

| Phosphorus | Synthetic fertilizers, manure | ~50% of phosphorus in IL rivers from agricultural sources [1] | Freshwater eutrophication, algal toxin production |

| Combined Nutrient Load | Tile drainage, surface runoff | Fall application increases nitrate losses versus spring [1] | Reduced biodiversity, fish kills, altered ecosystem structure |

Industrial Toxin Signatures

Industrial discharges introduce heavy metals and persistent toxic substances into aquatic systems, creating distinct contamination signatures based on industrial processes. A comprehensive river system assessment within an industrial zone revealed a clear pollution pattern, with zinc consistently demonstrating the highest concentration across all sample types [2]. The study employed highly sensitive analytical techniques to establish pollution trends, finding the concentration order in water samples was Zn > Cu > Ni > Cr > As > Pb > Hg > Cd, while in plants the order was Zn > Cr > Cu > Pb > Ni > As > Hg > Cd, and in sediments Zn > Cu > Pb > Ni > As > Hg [2].

Unlike agricultural nutrients, industrial toxins often bioaccumulate in biological tissues and persist in sediments for decades, creating long-term ecological impacts even after pollution sources are controlled. These contaminants directly affect aquatic organism health at multiple biological levels, from cellular and physiological processes to population and community dynamics.

Table 2: Industrial Heavy Metal Pollutants and Ecological Risks

| Heavy Metal | Concentration Trend (Water) | Concentration Trend (Sediment) | Ecological & Health Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn) | Highest concentration [2] | Highest concentration [2] | Aquatic toxicity, impaired reproduction |

| Copper (Cu) | Second highest [2] | Second highest [2] | Gill damage, oxidative stress in fish |

| Nickel (Ni) | Third highest [2] | Fourth highest [2] | Chronic toxicity to invertebrates |

| Chromium (Cr) | Fourth highest [2] | Not in top 5 in sediments [2] | Carcinogenic potential, developmental effects |

| Arsenic (As) | Fifth highest [2] | Fifth highest [2] | Human carcinogen, cardiovascular effects |

| Lead (Pb) | Sixth highest [2] | Third highest [2] | Neurotoxin, bioaccumulates in food webs |

| Mercury (Hg) | Seventh highest [2] | Sixth highest [2] | Neurotoxin, biomagnification |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Lowest concentration [2] | Not detected in trend [2] | Renal toxicity, osteoporosis |

Methodological Framework for Pollution Assessment

Analytical Techniques for Pollutant Quantification

Precise measurement of pollutant concentrations across environmental matrices requires sophisticated analytical instrumentation. The following protocols detail standardized methodologies for comprehensive pollution assessment.

Heavy Metal Analysis via ICP-MS and INAA

Instrumentation Principle: Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) utilizes high-temperature argon plasma to atomize and ionize samples, followed by mass separation and detection of specific isotopes. Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA) involves sample irradiation to produce radionuclides, whose decay characteristics enable element identification and quantification [2].

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Collect water samples in pre-cleaned HDPE bottles acidified to pH < 2 with ultrapure HNO₃

- Obtain sediment samples using a grab sampler, followed by freeze-drying and homogenization

- Harvest plant specimens, separating roots from shoots, washing with deionized water, and oven-drying at 70°C

- Digest 0.5g of solid samples with 10mL HNO₃:H₂O₂ (5:1) in microwave-assisted digestion system

- Dilute digestates to 50mL with ultrapure water and filter through 0.45μm membrane before analysis

Quality Assurance/Quality Control Measures:

- Include procedural blanks, certified reference materials (NIST 1640a for water, NIST 2702 for sediments), and duplicate samples

- Establish calibration curves with minimum R² = 0.999 for all target analytes

- Verify analytical accuracy with recovery rates of 85-115% for certified values

- Monitor instrument sensitivity with internal standards (e.g., Sc, Y, In, Bi)

Analysis Parameters:

- RF Power: 1550 W

- Nebulizer Gas Flow: 0.85-0.95 L/min

- Analysis Mode: Spectrum for qualitative, TQuant for quantitative

- Integration Time: 0.5-1.0 seconds per mass

- Detection Limits: Sub-μg/L for most elements [2]

Nutrient Loading Assessment in Agricultural Systems

Field Monitoring Design:

- Establish edge-of-field monitoring stations with automated water samplers

- Install flow-proportional sampling triggered by stage height or volume

- Collect samples across hydrographs, with intensified sampling during storm events

- Measure nitrate (NO₃-N), ammonium (NH₄-N), and soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP)

Analytical Methods:

- Nitrate: Cadmium reduction method (EPA 353.2) or ion chromatography

- Ammonium: Salicylate method (EPA 350.1)

- Phosphorus: Ascorbic acid method (EPA 365.1)

- Total Nitrogen and Phosphorus: Persulfate digestion followed by colorimetric analysis

Data Interpretation:

- Calculate nutrient loads using flow-weighted mean concentrations

- Express yields as mass per unit drainage area (kg/ha/year)

- Compare seasonal patterns related to fertilizer application and hydrology

Experimental Design for Ecosystem Impact Assessment

Controlled mesocosm studies provide critical data on the ecological effects of pollutants across biological organization levels.

Mesocosm Establishment:

- Configure 12-24 replicate aquatic mesocosms (1,000-2,000L)

- Establish native sediment and biological communities (phytoplankton, periphyton, invertebrates, fish)

- Allow systems to stabilize for 60-90 days before dosing

- Implement factorial designs crossing nutrient gradients with metal mixtures

- Include reference systems without contaminant additions

Response Variable Measurement:

- Water Quality: Daily measurement of dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity, temperature

- Nutrient Cycling: Weekly analysis of N and P species, chlorophyll a

- Community Structure: Biweekly sampling of plankton, monthly benthic invertebrate assessment

- Bioaccumulation: Tissue analysis from caged organisms at experiment termination

- Ecosystem Function: Measure primary production, respiration, decomposition rates

Statistical Analysis:

- Multivariate analysis (RDA, PERMANOVA) for community responses

- Dose-response modeling for threshold determinations

- Path analysis for direct and indirect effect quantification

- Time-series analysis for recovery trajectories

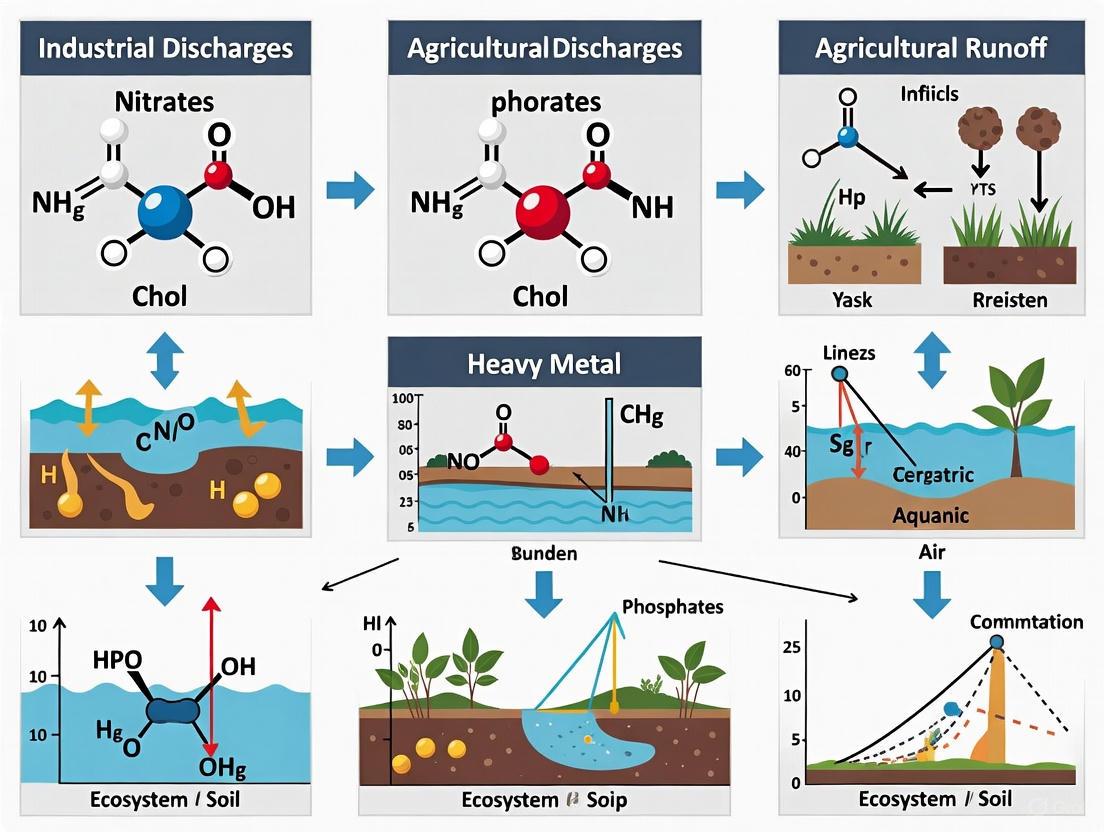

Research Visualization: Analytical Workflows

Comprehensive Environmental Assessment Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach for assessing combined impacts of agricultural and industrial pollutants on aquatic ecosystem health:

Diagram Title: Pollution Impact Assessment Workflow

Pollutant Fate and Transport Pathways

Understanding the movement and transformation of pollutants through environmental compartments is essential for predicting exposure scenarios:

Diagram Title: Pollutant Fate and Transport Pathways

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Comprehensive pollution impact research requires specialized reagents, reference materials, and analytical standards to ensure data quality and comparability across studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Reference Materials

| Reagent/Reference Material | Technical Specification | Research Application | Quality Assurance Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | NIST 1640a (Natural Water), NIST 2702 (Marine Sediment) | Calibration verification, accuracy assessment | Establish method recovery rates (85-115% acceptance) |

| Multi-element Stock Standards | 10-100 mg/L in 2% HNO₃, certified concentrations | ICP-MS/ICP-OES calibration | Primary instrument calibration traceable to NIST |

| Isotopic Tracers | Enriched stable isotopes (^65Cu, ^68Zn, ^111Cd) | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Correct for matrix effects, improve quantification |

| High-Purity Acids | Trace metal grade HNO₃, HCl (ppb level contaminants) | Sample digestion/preservation | Minimize background contamination |

| Certified Nutrient Standards | NO₃-N, NH₄-N, PO₄-P in aqueous matrix | Nutrient analyzer calibration | Ensure accurate nutrient quantification |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | C18, chelating resins, ion exchange media | Sample cleanup/preconcentration | Matrix elimination, analyte enrichment |

| Preservation Reagents | Zn acetate, H₂SO₄, HgCl₂, chloroform | Sample stabilization before analysis | Maintain analyte integrity during storage |

| Quality Control Materials | Laboratory fortified blanks, matrix spikes | Batch quality control | Monitor contamination, matrix effects |

Mitigation Approaches and Research Gaps

Agricultural Nutrient Intervention Strategies

Research demonstrates varying efficacy levels for different nutrient mitigation approaches:

Cover Cropping: Winter cover crops like cereal rye demonstrate 40% reductions in tile nitrate when grown ahead of soybean [1]. The "Fall Covers for Spring Savings" program in Illinois provides incentives for this practice [1].

Constructed Wetlands: Strategically placed wetlands achieve approximately 50% removal of tile nitrate while providing ancillary ecosystem benefits, though topographic constraints limit widespread implementation [1].

Bioreactors: Woodchip-filled trenches facilitating denitrification currently show <20% nitrate removal efficiency in field evaluations, though soil cap modifications may improve performance [1].

Diverse Crop Rotations: Corn-soybean-wheat rotations with double-cropped soybean following wheat and cereal rye after corn reduced tile nitrate losses over 30% while maintaining profitability in a six-year study [1].

Industrial Pollution Control Technologies

Advanced treatment technologies can significantly reduce industrial pollutant discharges:

Membrane Filtration: Reverse osmosis and nanofiltration effectively remove dissolved metals and inorganic contaminants.

Advanced Oxidation Processes: Utilize hydroxyl radicals to degrade persistent organic pollutants often co-discharged with metals.

Electrochemical Treatment: Electrocoagulation and electrooxidation can precipitate and transform heavy metals.

Adsorption Media: Specialty sorbents like ion-exchange resins, activated alumina, and functionalized clays target specific metal ions.

Critical Research Frontiers

Substantial knowledge gaps remain in several key areas:

- Synergistic Effects: Limited understanding of interactive impacts between nutrient enrichment and metal toxicity

- Ecosystem Recovery Trajectories: Insufficient data on restoration timelines following pollution abatement

- Nanoparticle Impacts: Emerging concerns about engineered nanomaterial effects in polluted ecosystems

- Climate Change Interactions: Uncertainties regarding how warming waters and altered hydrology will affect pollutant bioavailability

- Biomonitoring Advancements: Need for sensitive ecological indicators that provide early warning of ecosystem stress

The pollution spectrum spanning agricultural nutrients to industrial toxins presents complex challenges for ecosystem health research and environmental management. Effective mitigation requires integrated approaches that address both pollutant classes simultaneously, recognizing their interconnected impacts on aquatic ecosystems. Future research priorities should focus on developing multi-stressor assessment frameworks, validating innovative treatment technologies, and establishing evidence-based policies that incentivize pollution prevention at the watershed scale. Standardized methodologies, such as those presented in this technical guide, provide the foundation for generating comparable data across systems and temporal scales, ultimately supporting more effective ecosystem protection strategies.

Natural water purification is a critical ecosystem service, wherein biological, chemical, and physical processes within aquatic environments filter out pollutants and degrade organic matter. However, this service is experiencing significant disruption and collapse due to anthropogenic pressures. Framed within a broader thesis on the impact of industrial discharges and agricultural runoff on ecosystem health, this technical guide examines the mechanisms of this collapse. The influx of pollutants from these diffuse and point sources is overwhelming the self-purification capacity of freshwater and marine systems, leading to severe consequences for biodiversity, human health, and water security. This document provides a detailed analysis for researchers and scientists, integrating current data, experimental methodologies for monitoring, and visualizing the complex pathways of disruption.

Quantitative Impact of Key Pollutants

The following tables summarize the primary pollutants from industrial and agricultural activities, their direct effects on water purification mechanisms, and the resultant ecosystem-level consequences.

Table 1: Key Pollutants and Their Direct Impact on Purification Processes

| Pollutant Category | Source | Impact on Purification Mechanism | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive Nutrients (N, P) | Agricultural fertilizer runoff, untreated municipal wastewater [3] | Drives eutrophication; algal blooms deplete dissolved oxygen (DO), causing hypoxic "dead zones" and disrupting microbial communities [3]. | Chlorophyll-a, DO concentration, Secchi depth [4]. |

| Organic Matter | Food processing, pulp/paper mills, municipal sewage [3] | Increases biological oxygen demand (BOD), depleting DO and suffocating aerobic decomposers essential for breaking down waste [3]. | BOD, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), DO [3]. |

| Suspended Solids | Construction, soil erosion, industrial discharges | Blocks sunlight, reduces photosynthesis in aquatic plants, smothers benthic organisms and their habitats. | Total Suspended Solids (TSS), Turbidity (NTU). |

| Heavy Metals | Mining, smelting, industrial manufacturing | Toxicity disrupts enzyme functions in aquatic flora and fauna; bioaccumulates in the food web. | Concentrations of Pb, Hg, Cd, As (e.g., mg/L). |

| Emerging Contaminants / Inactive Ingredients | Herbicide formulations, pharmaceuticals [5] | Inert ingredients (e.g., amines) can transform during water disinfection into hazardous by-products like nitrosamines [5]. | Precursor concentration, DBP formation potential [5]. |

Table 2: Documented Ecosystem Consequences of Purification Collapse

| Ecosystem Consequence | Underlying Cause | Documented Example / Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Eutrophication & Hypoxia | Nutrient over-enrichment leading to algal blooms and subsequent oxygen depletion [3]. | >90% of rivers in Poland threatened by eutrophication; dead zones in Gulf of Mexico [3]. |

| Biodiversity Loss | Toxicity, habitat smothering, and oxygen deprivation [3]. | Changes in freshwater community structure; loss of sensitive species (e.g., certain fish, macroinvertebrates) [3]. |

| Human Health Risks | Pathogens and toxic chemicals entering water bodies used for recreation, irrigation, or drinking [3]. | Use of polluted water in irrigation linked to infectious diseases (e.g., hepatitis A, E. coli) [3]. |

| Disruption of Treatment Plants | High or toxic pollutant loads can overwhelm engineered treatment systems. | Emergency discharge of 3.65 million m³ of untreated wastewater in Warsaw, Poland [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring and Analysis

Tracking Agricultural Contaminant Precursors

Objective: To quantify and characterize the role of inactive ingredients in agricultural runoff as precursors for hazardous disinfection by-products (DBPs) in drinking water [5].

Methodology:

- Source Analysis: Compile inventory of commonly used herbicides, focusing on both active and inactive formulation components (e.g., stabilizing amines). Use agricultural agency data and sales records to estimate regional usage rates [5].

- Field Sampling: Collect water samples from agricultural drainage ditches, receiving streams, and nearby water treatment plant intakes. Sampling should be stratified by region and time (e.g., pre- and post-application seasons) to account for spatial and temporal variability [5].

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Targeted Analysis: Use Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to quantify specific amine-based compounds.

- DBP Formation Potential (FP) Assay: Subject water samples to controlled chlorination (or other disinfection methods) under standardized conditions (pH, chlorine dose, contact time, temperature). Subsequently, measure the formation of nitrogenous DBPs (N-DBPs), such as nitrosamines, using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [5].

- Data Correlation: Statistically correlate the concentrations of identified precursor amines in environmental samples with the measured N-DBP FP to establish their relative importance compared to other known precursors (e.g., from pharmaceuticals).

Machine Learning-Based Water Quality Dynamic Prediction

Objective: To develop a robust predictive model for water quality parameters, enabling proactive management.

Methodology (as per the integrated LSTM framework) [4]:

- Data Collection & Pre-processing: Collect high-frequency time-series data for multiple water quality parameters (e.g., DO, COD~Mn~, Water Temperature (WT), pH, electrical conductivity) from automated monitoring stations [4].

- Data Denoising: Apply techniques like Wavelet Transform (WL) or Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) to reduce noise and reveal underlying patterns in non-stationary time-series data [4].

- Feature Selection: Use statistical analyses (e.g., mutual information, correlation analysis) to identify the key driving factors (e.g., WT is a key driver for DO) and select the most relevant input features for the model [4].

- Model Building & Training:

- Architecture: Implement a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network. LSTM's gated structure (input, forget, output gates) is adept at capturing long-term temporal dependencies in time-series data [4].

- Data Partitioning: Partition the time-series dataset chronologically into training and testing sets, avoiding random splitting to preserve temporal context [4].

- Training: Train the LSTM model on the historical sequence data to learn the mapping between input features (e.g., past WT, pH, flow) and target outputs (e.g., future DO concentration).

- Model Validation & Deployment:

- Performance Evaluation: Validate the model on the testing set using metrics like R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Studies show LSTM can achieve R² > 0.99 for DO prediction [4].

- Application: The trained model can be used for multi-step-ahead forecasting of water quality, providing early warnings for degradation events and supporting management decisions for large-scale hydrological projects [4].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

Pollutant Impact Pathway on Aquatic Ecosystems

The following diagram illustrates the causal pathway through which industrial and agricultural discharges disrupt the natural water purification ecosystem service.

Predictive Modeling Experimental Workflow

This diagram outlines the integrated machine learning framework for predicting water quality dynamics, a key tool for researching ecosystem service disruption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents, materials, and tools required for conducting advanced research in water ecosystem disruption.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Technical Specification / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | Used for extraction and analysis of emerging organic contaminants (e.g., herbicide amines, pharmaceuticals) from water samples [5]. | High purity (>99.9%) minimizes background interference and enhances detection sensitivity and accuracy in mass spectrometry [5]. |

| Disinfection By-Product (DBP) Standards | Certified reference materials for nitrosamines and other DBPs. Used for calibrating GC-MS/MS systems and quantifying compounds in FP assays [5]. | Enables precise and accurate quantification of trace-level hazardous compounds; essential for method validation and data comparability. |

| LSTM-Based Modeling Framework | A predictive computational tool for modeling complex, non-linear water quality dynamics using time-series data [4]. | Superior to traditional models (e.g., ARIMA) for capturing temporal dependencies; demonstrated R² > 0.99 for DO prediction [4]. |

| Multi-Parameter Water Quality Sondes | In-situ sensors for continuous, high-frequency monitoring of key parameters (DO, pH, COD~Mn~, conductivity, temperature, turbidity) [4]. | Provides the dense, high-quality time-series data required for training and validating robust machine learning models [4]. |

| Wavelet Transform Toolbox | A computational data denoising technique (e.g., in Python or MATLAB) applied to raw sensor data before model training [4]. | Mitigates the challenge of non-stationarity in time-series data, improving the predictive performance and stability of LSTM models [4]. |

| Chlorination Reagents | Sodium hypochlorite solution and pH buffers for conducting standardized DBP Formation Potential (FP) tests in the laboratory [5]. | Allows for simulation of drinking water treatment conditions to assess the precursor potential of environmental samples under controlled settings [5]. |

Industrial discharges and agricultural runoff represent significant pathways for the introduction of harmful substances into ecosystems, driving complex environmental degradation processes. This technical guide examines three interconnected mechanisms—eutrophication, bioaccumulation, and toxicity—that mediate the impact of these anthropogenic activities on ecosystem health. These mechanisms operate across multiple biological scales, from molecular interactions to ecosystem-level dynamics, presenting substantial challenges for environmental risk assessment and mitigation. Understanding their underlying processes is crucial for researchers and environmental professionals developing intervention strategies and regulatory frameworks. This whitepaper synthesizes current scientific knowledge on these mechanisms, with a specific focus on quantitative assessment methods, experimental approaches, and implications for ecological and human health within the context of persistent pollutant exposure.

Eutrophication: Nutrient Over-enrichment of Aquatic Systems

Definition and Primary Causes

Eutrophication is a process in which nutrients accumulate in a body of water, resulting in an increased growth of organisms that may deplete the oxygen in the water [6]. While eutrophication occurs naturally over geological timescales, cultural eutrophication caused by human activities has dramatically accelerated this process globally [6]. The primary nutrients driving eutrophication are phosphorus (P) in freshwater ecosystems and nitrogen (N) in marine environments [6].

The main anthropogenic sources of these nutrients include:

- Agricultural runoff containing fertilizers and animal wastes [7] [6]

- Untreated or partially treated sewage and wastewater [8] [6]

- Industrial discharges and atmospheric deposition of nitrogen from combustion processes [6]

Agricultural non-point source pollution has been identified as a dominant contributor to eutrophication, responsible for approximately 52% and 54% of total nitrogen and phosphorus loading, respectively, in China's Taihu Lake Basin [7]. Similarly, in the United States, agricultural runoff is considered the primary source of nutrients in impaired lakes and streams [7].

Mechanistic Pathways and Ecological Impacts

The eutrophication process follows a sequential mechanistic pathway that fundamentally alters aquatic ecosystems:

Table 1: Ecological Effects of Eutrophication

| Effect Type | Primary Manifestations | Ecological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Production | Increased phytoplankton biomass; Algal blooms | Shading of benthic plants; Shift in dominant primary producers |

| Community Structure | Changes in macrophyte species composition; Decreased biodiversity | Loss of habitat-forming species; Simplified food webs |

| Water Quality | Dissolved oxygen depletion; Increased turbidity | Hypoxic/anoxic conditions; Fish kills; Loss of desirable species |

| Toxin Production | Proliferation of toxic cyanobacteria; Harmful algal blooms | Shellfish poisoning; Human health risks; Livestock mortality |

The progression begins with nutrient enrichment from agricultural and industrial sources, which stimulates rapid growth of phytoplankton and algae, leading to algal blooms [8] [6]. These blooms limit light penetration to submerged aquatic vegetation while simultaneously producing oxygen during daylight hours through photosynthesis. However, when the algae die, their decomposition by heterotrophic bacteria consumes dissolved oxygen, potentially creating hypoxic (low oxygen) or anoxic (no oxygen) conditions [6]. These oxygen-depleted "dead zones" cause suffocation and death of fish and other aerobic organisms, resulting in substantial ecological degradation [9] [6].

Eutrophication also drives significant biodiversity loss through competitive exclusion. Normally limiting nutrients become abundant, allowing competitive species to invade and outcompete native inhabitants [6]. This process has been documented in New England salt marshes, where nutrient enrichment alters competitive hierarchies and community structure [6].

Assessment Methodologies and Metrics

Eutrophication assessment has evolved from simple individual parameters to comprehensive multi-metric indexes. Key analytical approaches include:

Traditional Nutrient Limitation Bioassays:

- Principle: Determine whether N, P, or both nutrients limit algal growth through controlled nutrient addition experiments

- Methodology: Collection of water samples followed by laboratory incubation with nutrient amendments (N, P, N+P) while monitoring chlorophyll-a concentration or algal biomass accumulation

- Historical Context: Pioneered at the Experimental Lakes Area in Ontario, Canada, in the 1970s, providing definitive evidence that freshwater systems are typically phosphorus-limited [6]

Modern Comprehensive Assessment: Contemporary eutrophication assessment employs multiple complementary metrics:

- Nutrient concentrations: Total phosphorus (TP), total nitrogen (TN), N:P ratios

- Biological response indicators: Chlorophyll-a, phytoplankton composition and biomass, submerged aquatic vegetation coverage

- System-level parameters: Dissolved oxygen dynamics, water transparency (Secchi depth), hypolimnetic oxygen depletion rates

The development of total nutrient status indexes represents a significant advancement in eutrophication assessment, integrating multiple parameters into a unified framework for more robust ecosystem evaluation [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Nutrient Loss from Agricultural Runoff

| Agricultural System | Fertilizer Application (kg ha⁻¹ year⁻¹) | Runoff Loss Rate (%) | Annual Nutrient Discharge (kg ha⁻¹ year⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Cropland | 196 N, 87 P | 9.5% N, 3.3% P | 18.62 N, 2.87 P |

| Paddy Soils | 210 N, 36 P | 5.9% N, 0.52% P | 12.39 N, 0.18 P |

Note: Data compiled from multiple agricultural systems showing significant variation in nutrient runoff based on management practices [7].

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Bioaccumulation refers to the gradual increase of toxic chemicals in the body tissues of living organisms over time, occurring when chemical uptake exceeds the rate of elimination through excretion or catabolism [11]. This process is particularly concerning for Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals that resist metabolic breakdown [11].

Biomagnification (or bioamplification) describes the progressive concentration of chemical toxins at successively higher trophic levels in a food chain [11]. While bioaccumulation occurs within individual organisms, biomagnification operates across trophic transfers, resulting in the highest concentrations in apex predators.

The biological half-life of chemical toxins is a critical determinant of bioaccumulation potential—substances with longer half-lives present greater poisoning risks even when environmental concentrations are low [11].

Pathways and Mechanisms

The bioaccumulation and biomagnification process follows a predictable pathway through aquatic ecosystems:

Figure 1: Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification Pathways in Aquatic Ecosystems

The process begins when POPs such as organochlorine pesticides (DDT), industrial chemicals (PCBs), and heavy metals enter water bodies from industrial and agricultural sources [11]. These contaminants are absorbed by primary producers like phytoplankton directly from water, accumulating in their tissues at concentrations exceeding environmental levels [11]. With each trophic transfer, contaminants become more concentrated, resulting in apex predators accumulating toxins at levels millions of times higher than the surrounding water [11].

Case Study: Minamata Disease

The Minamata disaster in Japan represents a classic case study of bioaccumulation and biomagnification. Between 1932 and 1968, the Chisso Corporation discharged industrial waste containing mercury into Minamata Bay [11]. The inorganic mercury was transformed by microbial activity into methylmercury (MeHg), which subsequently bioaccumulated in fish and shellfish [11].

Marine products from the bay showed extremely high mercury contamination levels (5.6-35.7 ppm), with residents of the Shiranui coastline exhibiting hair mercury concentrations as high as 705 ppm [11]. The resulting mercury poisoning caused severe neurological symptoms including ataxia, sensory disturbance, dysarthria, and auditory and visual impairment in humans and other animals [11]. As of March 2001, 2,265 officially recognized cases of Minamata disease were documented, including 1,784 deaths [11].

Global Regulation of Persistent Organic Pollutants

The Stockholm Convention, signed in 2001 by the United States and 90 other countries including the European Union, represents a landmark international treaty to eliminate or reduce the production, use, and release of 12 priority POPs [11]. The original "dirty dozen" included:

- Pesticides: DDT, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, aldrin, toxaphene, mirex, hexachlorobenzene, and heptachlor

- Industrial chemicals: Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and hexachlorobenzene

- By-products: Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, hexachlorobenzene, and polychlorinated dibenzofurans

By 2017, sixteen additional POPs had been added to the treaty, reflecting growing recognition of their global threat [11].

Toxicity Mechanisms of Key Pollutants

Heavy Metal Toxicity

Heavy metals such as lead (Pb), chromium (Cr), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni) persist indefinitely in the environment, posing significant toxicological threats [12]. While some metals (Cu, Zn, Cr, Ni, Co, Mo, Fe) function as essential micronutrients at appropriate concentrations, all metals become toxic at elevated levels [12].

Table 3: Heavy Metal Toxicity Mechanisms and Effects

| Metal | Primary Toxicity Mechanisms | Biological Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | Antagonism with calcium absorption; disruption of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis | Skeletal deformities; developmental障碍; carcinogenic (lung, prostate, kidney cancers) |

| Lead (Pb) | Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE); stimulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Neurotoxicity; oxidative stress; reduced glutathione (GSH) levels |

| Mercury (Hg) | Particularly methylmercury; binding to sulfhydryl groups; lipid membrane disruption | Reduced sperm motility; DNA damage; embryonic developmental defects; neurotoxicity |

| Arsenic (As) | disruption of ATP production; oxidative stress; DNA damage | Skin lesions; cardiovascular disease; neurotoxicity; various cancers |

Heavy metals induce toxicity through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

- Oxidative stress via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage cellular components [12]

- Enzyme inhibition through binding to active sites or protein denaturation [12]

- DNA damage and disruption of genetic material, potentially leading to mutagenesis and carcinogenesis [12]

- Disruption of ion regulation, particularly through competition with essential cations like calcium [12]

The developmental stage significantly influences metal susceptibility, with younger organisms typically more vulnerable. For example, zebrafish larvae showed increased skeletal malformations when exposed to CdCl₂, with toxicity enhanced at higher water temperatures [12].

Antibiotic Toxicity and Resistance

Antibiotics entering aquatic environments through agricultural runoff, aquaculture, and wastewater discharges pose emerging threats to ecosystem health. China, as the world's largest antibiotic producer and consumer, used approximately 162,000 tons of 36 frequently detected antibiotics in 2013 alone—roughly nine times the consumption of the United States [12]. An estimated 58% of administered antibiotics are excreted unchanged or as metabolites into the environment [12].

Key antibiotic classes detected in water environments include:

- Sulfonamides

- Chloramphenicols

- Quinolones

- Tetracyclines

- Macrolides

Environmental antibiotics exert selective pressure on microbial communities, driving the development and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes [9]. This selection disrupts native microbial community structure and function, potentially compromising essential ecosystem processes mediated by bacterial communities [12]. Furthermore, antibiotics can directly affect non-target organisms across trophic levels, though these impacts remain inadequately characterized, particularly for chronic, low-level exposures typical of environmental scenarios.

Combined Toxicity of Complex Mixtures

Environmental pollutants rarely occur in isolation, forming complex mixtures that may interact to produce unexpected toxicological outcomes. Heavy metals and antibiotics frequently co-occur in aquatic systems receiving both industrial and agricultural inputs [12]. Their combined effects may manifest as:

- Additive toxicity: The combined effect equals the sum of individual effects

- Synergistic toxicity: The combined effect exceeds the sum of individual effects

- Antagonistic toxicity: The combined effect is less than the sum of individual effects

Research indicates that cadmium and antibiotic combinations can produce synergistic developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos [12]. Similarly, copper nanoparticles combined with tetracycline exhibit enhanced toxicity to aquatic bacteria compared to either contaminant alone [12]. These interactions highlight the critical need for mixture toxicity assessment in environmental risk evaluation, as regulatory frameworks based on single-substance toxicity may substantially underestimate ecological risks.

Experimental Approaches and Assessment Methodologies

Standardized Ecotoxicological Testing

Current ecotoxicological assessment employs standardized test organisms and endpoints to evaluate contaminant effects:

Acute Toxicity Testing:

- Organisms: Daphnia magna (water flea), Danio rerio (zebrafish), Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (green algae)

- Endpoints: Lethality (LC50), immobilization (EC50), growth inhibition (IC50)

- Duration: 24-96 hours depending on species and protocol

Chronic Toxicity Testing:

- Organisms: As above, plus additional model species relevant to specific ecosystems

- Endpoints: Reproduction, growth, development, teratogenicity, genotoxicity

- Duration: Days to weeks, encompassing critical life stages

Molecular Biomarkers:

- Oxidative stress: Glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), lipid peroxidation (MDA)

- Neurotoxicity: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition

- Detoxification: Glutathione S-transferase (GST), metallothioncins

- Cellular damage: DNA strand breaks, micronuclei formation, apoptosis markers

Advanced Analytical Techniques

Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) has emerged as a powerful tool for visualizing the spatial distribution of contaminants and their biological effects in tissue samples [13]. Key MSI modalities include:

Table 4: Mass Spectrometry Imaging Techniques for Contaminant Analysis

| Technique | Mass Analyzer | Applicable Analytes | Spatial Resolution | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI-MSI | TOF MS | Metabolites, proteins, peptides, drugs, pollutants | 5.0 μm (vacuum), 1.4 μm (ambient) | Matrix application required; ion suppression in low mass compounds |

| DESI-MSI | TOF MS | Compounds <2000 Da | Up to 10 μm | Lower spatial resolution |

| SI-MSI | TOF MS | Elements, compounds <1000 Da | 0.05-1.0 μm | Instrument expense; ion fragmentation |

| LA-ICP-MSI | TOF MS | Elements | Up to 5.0 μm | Matrix and fractionation effects |

MSI enables simultaneous detection of numerous endogenous and exogenous compounds while preserving their spatial information in biological tissues [13]. This capability provides unique insights into contaminant distribution, metabolism, and resulting physiological effects at the tissue and cellular levels.

Experimental Workflow for Combined Toxicity Assessment

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Assessing Pollutant Mixture Toxicity

This integrated approach combines traditional toxicity endpoints with advanced molecular and spatial analyses to characterize complex mixture interactions. The workflow begins with systematic experimental design, proceeds through tiered exposure studies, and culminates in data integration to model contaminant interactions and identify key toxicity pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Environmental Toxicology Research

| Reagent/Method | Category | Primary Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia magna | Model organism | Acute toxicity screening (immobilization); reproductive effects | 48-hour acute tests; 21-day chronic reproduction tests |

| Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | Model organism | Developmental toxicity; neurotoxicity; teratogenicity | Embryonic development complete at 96 hpf; transparent embryos ideal for visualization |

| Metallothionein antibodies | Biochemical reagent | Biomarker for metal exposure and detoxification | Protein levels increase with metal exposure; indicates physiological response |

| Acetylcholinesterase assay kit | Biochemical assay | Neurotoxicity assessment | Enzyme inhibition indicates pesticide or metal neurotoxicity |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) detection probes | Chemical probes | Oxidative stress measurement | DCFH-DA commonly used; fluorescence indicates oxidative stress |

| COMET assay reagents | Genotoxicity testing | DNA damage assessment | Single-cell gel electrophoresis visualizes DNA strand breaks |

| LC-MS/MS systems | Analytical instrument | Quantification of antibiotics, pesticides, and metabolites | High sensitivity and specificity; requires method development for new compounds |

| MALDI-MSI matrix compounds | MSI reagents | Facilitate desorption/ionization in mass spectrometry imaging | DHB, CHCA common for small molecules; matrix selection critical for sensitivity |

This toolkit represents essential resources for investigating eutrophication, bioaccumulation, and toxicity mechanisms. Selection of appropriate model organisms, biochemical assays, and analytical methods should align with specific research questions and contaminant properties.

Eutrophication, bioaccumulation, and toxicity represent interconnected mechanisms through which industrial discharges and agricultural runoff impact ecosystem health. Eutrophication driven by nitrogen and phosphorus inputs disrupts aquatic ecosystem structure and function through oxygen depletion and habitat degradation. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification processes concentrate persistent pollutants through food webs, threatening apex predators and human consumers. Complex toxicity mechanisms, particularly from contaminant mixtures, present challenges for ecological risk assessment and regulatory control.

Addressing these interconnected threats requires integrated approaches spanning source control, environmental monitoring, and advanced toxicological assessment. Future research priorities should include:

- Enhanced understanding of mixture toxicity interactions under environmentally relevant conditions

- Development of sensitive biomarkers for early detection of ecosystem stress

- Advanced modeling approaches to predict bioaccumulation potential of emerging contaminants

- Innovative treatment technologies for nutrient and contaminant removal from agricultural and industrial wastewater

By elucidating the mechanistic basis of these key harm pathways, researchers and environmental professionals can develop more effective strategies for protecting ecosystem health in the face of increasing anthropogenic pressures.

This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of ecosystem collapse in three major river basins—the Ganges (India), Citarum (Indonesia), and Mississippi (United States). Framed within broader research on industrial discharge and agricultural runoff impacts, this assessment examines the synergistic effects of multiple stressors on aquatic ecosystem health. Using standardized risk assessment protocols, including indicators from the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems framework, we document severe degradation across all three systems despite their geographical and socioeconomic differences. The analysis reveals that converging pressures from chemical pollution, nutrient loading, and hydrological modification have pushed these ecosystems toward critical thresholds, with profound implications for biodiversity, human health, and water security. Evidence-based solutions and research methodologies are presented to guide conservation interventions and monitoring efforts for researchers and environmental health professionals.

Ecosystem collapse represents the endpoint of severe degradation, where essential structures, processes, and biodiversity are irreversibly lost, compromising ecosystem service delivery. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Ecosystems (RLE) provides a standardized framework for assessing collapse risk, using indicators across distributional, abiotic, and biotic dimensions [14]. Climate change amplifies these risks by altering hydrological regimes and increasing extreme events, thereby reducing ecosystem resilience [14]. For river ecosystems, collapse manifests through biodiversity loss, hypoxic conditions, and functional impairment, often triggered by synergistic pressures from industrial, agricultural, and urban pollution sources.

Comparative Case Studies

Ganges River Basin, India

Pollution Profile and Stressors

The Ganges River exemplifies ecosystem collapse driven by multifaceted pollution pressures affecting over 500 million people across its 2,525-kilometer course [15]. The basin faces compounding stressors from industrial discharge, untreated sewage, agricultural runoff, and religious practices [16] [17].

Industrial pollution originates from approximately 1,100 industrial units along its banks, including tanneries, textile mills, and chemical plants that discharge untreated effluents containing heavy metals like mercury, lead, and cadmium [15] [17]. Municipal sewage from major population centers represents another primary stressor, with over 80% of wastewater entering the river untreated [15]. This creates dangerously high levels of fecal coliform bacteria, often measuring hundreds of times above safe bathing limits [17]. Agricultural runoff introduces pesticides and fertilizers that drive eutrophication, while religious practices contribute solid waste including floral offerings and non-biodegradable materials [16].

Table 1: Key Pollution Indicators in the Ganges River

| Parameter | Level/Measurement | Ecological Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Coliform | Hundreds of times above safe limits | Waterborne disease transmission [17] |

| Heavy Metals | Mercury, lead, cadmium exceeding safety standards | Bioaccumulation in aquatic food webs [15] |

| BOD/COD | Elevated levels indicating organic pollution | Oxygen depletion, habitat degradation [17] |

| Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria | Present in multiple stretches | Public health crisis, "superbugs" [15] |

Ecosystem Collapse Indicators

The Ganges exhibits multiple indicators of ecosystem collapse, including massive fish die-offs, loss of endemic species like the Ganges river dolphin, and functional impairment of natural purification processes [15] [17]. Economic impacts include healthcare costs from waterborne diseases, reduced agricultural productivity from contaminated irrigation, and diminished tourism potential [17]. The government's Namami Gange Programme has achieved limited success due to inadequate sewage infrastructure, weak enforcement of regulations, and insufficient public participation in conservation efforts [18] [17].

Citarum River Basin, Indonesia

Pollution Profile and Stressors

The Citarum River in West Java, Indonesia, represents one of the most severely degraded river ecosystems globally, with pollution primarily driven by industrial concentration, particularly from textile manufacturing [19]. Over 2,000 textile factories discharge untreated wastewater containing synthetic dyes, chemical finishing agents, and heavy metals directly into the river system [15]. Mercury levels in the river have been measured at 100 times international safety standards, creating severe toxicological risks [15].

The river's degradation reflects decades of unregulated industrial growth without corresponding investment in wastewater infrastructure. Additional stressors include untreated domestic sewage and agricultural runoff containing pesticides and herbicides [19]. The solid waste burden is extreme, with plastic debris and other materials creating physical barriers to flow and navigation.

Table 2: Pollution Sources and Impacts in the Citarum River

| Pollutant Category | Specific Contaminants | Human Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Chemicals | Heavy metals (lead, mercury, cadmium), textile dyes | Skin diseases, respiratory problems, cancer risks [19] |

| Domestic Waste | Untreated sewage, plastic debris | Gastrointestinal infections, skin irritation [15] [19] |

| Agricultural Runoff | Pesticides, herbicides | Developmental disorders, chronic poisoning [19] |

Ecosystem Collapse Indicators

The Citarum River exhibits advanced ecosystem collapse, with complete loss of commercial fisheries due to toxic conditions and oxygen depletion [19]. Biodiversity has dramatically declined, with most native species unable to survive in the polluted waters. The river's natural sediment composition has been altered by accumulated industrial waste, fundamentally changing benthic habitats [19]. Social impacts include economic losses from damaged agriculture, increased healthcare burdens, and the marginalization of traditional riverside communities [19].

Mississippi River Basin, United States

Pollution Profile and Stressors

The Mississippi River Basin faces a different collapse profile dominated by non-point source agricultural pollution across the American heartland [20] [21]. Intensive farming practices, particularly for corn (maize) production, drive massive inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers into the watershed [20]. Additional agricultural stressors include pesticide contamination, soil erosion, and runoff from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) [21].

Unlike point source pollution, agricultural runoff represents a diffuse challenge that remains largely exempt from Clean Water Act regulations, creating significant governance challenges [20] [21]. The basin's natural hydrology has been extensively modified through channelization, levee construction, and dam installation, compromising natural floodplain connectivity and sediment transport processes [21].

Ecosystem Collapse Indicators

The primary collapse indicator for the Mississippi River is the annual formation of a hypoxic "Dead Zone" in the Gulf of Mexico, which measured approximately 8,000 square miles in recent years [15] [21]. This hypoxic zone forms when excess nutrients from the river stimulate algal blooms that deplete oxygen through decomposition, creating conditions unsuitable for most marine life [20]. Within the river itself, biodiversity loss manifests through fish kills, harmful algal blooms, and impaired drinking water sources [21]. The ecological damage creates economic impacts through reduced fisheries productivity, increased water treatment costs, and lost recreational value [21].

Assessment Methodologies and Research Protocols

IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Framework

The IUCN RLE framework provides standardized protocols for assessing ecosystem collapse risk through multiple criteria [14] [22]. The following workflow outlines the application of this framework to river ecosystems:

Field Assessment and Monitoring Protocols

Water Quality Sampling Protocol

Objective: Quantify pollutant concentrations and assess compliance with water quality standards across river basins.

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Establish monitoring stations upstream and downstream of major pollution point sources (industrial discharges, municipal outfalls, agricultural regions)

- Sampling Frequency: Collect samples quarterly, with increased frequency during seasonal high-flow events

- Core Parameters:

- Physical: Temperature, turbidity, conductivity, total suspended solids

- Chemical: pH, dissolved oxygen, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus), heavy metals (mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium), pesticides, emerging contaminants

- Biological: Fecal coliform bacteria, antibiotic-resistant genes, chlorophyll-a

- Quality Assurance: Implement field blanks, duplicates, and certified reference materials to ensure data quality

Ecological Health Assessment Protocol

Objective: Evaluate biotic integrity and ecosystem function through biological indicators.

Methodology: 1. Fish Community Assessment: - Conduct electrofishing surveys at standardized reaches - Measure species richness, abundance, biomass, and functional composition - Calculate Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) scores - Examine fish for deformities, lesions, tumors as indicators of toxic exposure 2. Benthic Macroinvertebrate Sampling: - Collect composite samples using D-frame nets - Identify to genus or species level where possible - Calculate multivariate metrics (diversity, EPT index, tolerance measures) 3. Ecosystem Function Metrics: - Measure leaf litter decomposition rates - Assess nutrient uptake using stable isotope additions - Quantify primary production and community respiration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for River Ecosystem Assessment

| Reagent/Equipment | Technical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| YSI EXO2 Multiparameter Sonde | In-situ measurement of dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity, temperature, turbidity, chlorophyll | Continuous water quality monitoring at fixed stations [17] |

| ICP-MS System | Detection of heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cd, Cr) at parts-per-trillion levels | Quantifying industrial pollutant concentrations [15] [17] |

| HPLC with Fluorescence Detection | Analysis of pesticide residues and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Tracking agricultural chemical fate and transport [21] |

| qPCR Instrument | Quantification of fecal indicator bacteria (E. coli, Enterococcus) and antibiotic resistance genes | Assessing sewage contamination and public health risks [15] [17] |

| Stable Isotope Analyzer | Measurement of δ¹⁵N and δ¹³C ratios in biotic tissues | Tracing nutrient pollution sources through food webs [20] |

| GF/F Filters (0.7μm) | Particulate matter collection for chlorophyll-a, nutrient, and suspended solids analysis | Assessing eutrophication status and sediment loads [20] |

| D-frame Kick Nets | Standardized benthic macroinvertebrate collection | Biological monitoring and index development [22] |

Data Integration and Risk Analysis

Effective ecosystem risk assessment requires integrating diverse data sources to evaluate collapse risk. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between primary stressors, ecological mechanisms, and collapse indicators across the three river basins:

Quantitative Risk Assessment

The IUCN Red List of Ecosystems framework utilizes five criteria to evaluate ecosystem collapse risk [14] [22]:

- Criterion A: Current reduction in distribution

- Criterion B: Restricted geographic distribution

- Criterion C: Environmental degradation

- Criterion D: Disruption of biotic processes

- Criterion E: Quantitative modeling of collapse risk

For river ecosystems, Criterion C (environmental degradation) typically provides the strongest evidence of collapse risk, measured through:

- Water quality indices exceeding regulatory thresholds

- Sediment contaminant concentrations

- Biological integrity scores

- Nutrient loading rates

Uncertainty evaluation should acknowledge data limitations, especially for non-point source pollution tracking and emerging contaminant impacts [22].

Conservation and Restoration Strategies

Policy and Regulatory Interventions

Effective governance requires strengthened regulatory frameworks with robust enforcement mechanisms. The Clean Water Act's exemption for agricultural runoff represents a critical regulatory gap that must be addressed through state-level nutrient reduction strategies [21]. For industrial pollution, zero-discharge standards for priority pollutants and mandatory effluent treatment protocols are essential [15] [19]. Economic instruments including pollution taxes, water quality trading programs, and conservation subsidies can incentivize compliance [20].

Technological and Infrastructure Solutions

Investment in wastewater treatment infrastructure represents a fundamental priority, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions [15] [19]. Advanced treatment technologies including membrane filtration, advanced oxidation, and constructed wetlands can remove multiple pollutant classes simultaneously [19]. For agricultural pollution, precision farming technologies, buffer strips, and wetland restoration can significantly reduce nutrient loads [20] [21]. Real-time water quality monitoring networks enhance regulatory capacity and early warning systems [23].

Integrated River Basin Management

Sustainable solutions require cross-sectoral coordination at the river basin scale, addressing the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus [23]. Participatory approaches that engage farmers, industries, municipalities, and civil society in co-developing management strategies enhance implementation and compliance [21] [23]. Environmental flow assessments ensure that water allocation policies maintain ecological functions while meeting human needs [23].

The Ganges, Citarum, and Mississippi River case studies demonstrate that ecosystem collapse results from synergistic interactions among multiple stressors, with industrial discharges and agricultural runoff playing predominant roles. Despite differing socioeconomic contexts, all three basins exhibit similar collapse trajectories including biodiversity loss, hypoxic conditions, and impaired ecosystem services.

Critical research priorities include:

- Advanced contaminant tracking to identify pollution sources and transport pathways

- Ecosystem resilience thresholds to establish scientifically-defensible management targets

- Climate change interactions with existing stressors to forecast future collapse risks

- Remediation effectiveness evaluation to guide optimized intervention strategies

- Economic valuation of ecosystem services to justify conservation investments

Preventing complete ecosystem collapse in these and other major river basins requires immediate, science-based intervention combining regulatory strength, technological innovation, and inclusive governance. The methodologies and frameworks presented herein provide researchers and practitioners with standardized approaches for assessing collapse risk and guiding conservation investments.

Linking Environmental Degradation to Zoonotic and Waterborne Disease Risks

Environmental degradation, driven by industrial discharges and agricultural runoff, is a significant driver of ecological change that directly influences the emergence and transmission of zoonotic and waterborne diseases. This nexus represents a critical interface where ecosystem health, human activity, and pathogen dynamics converge [24] [25]. The deterioration of natural systems through pollution, habitat fragmentation, and biodiversity loss alters the delicate balance between pathogens, hosts, and the environment, creating new pathways for disease transmission [26] [25]. Understanding these interconnected relationships is paramount for researchers and public health professionals developing strategies to mitigate disease risks in an increasingly altered planet.

The "One Health" paradigm emphasizes the inextricable links between ecosystem health, animal health, and human well-being, highlighting that environmental degradation is not merely an ecological concern but a fundamental determinant of public health [26]. Within this framework, industrial and agricultural activities serve as primary drivers of environmental change, releasing contaminants that reshape microbial communities, compromise ecosystem services, and create conditions favorable for pathogen proliferation and transmission [24] [27]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms through which these environmental changes influence disease risks, providing researchers with methodologies and analytical frameworks for investigating these complex relationships.

Mechanisms Linking Environmental Degradation to Disease Emergence

Agricultural Intensification and Zoonotic Spillover

Agricultural intensification significantly modifies landscapes and ecological relationships, increasing the risk of zoonotic disease emergence through multiple pathways. The conversion of natural habitats to agricultural land reduces biodiversity and brings wildlife, livestock, and humans into closer proximity, facilitating pathogen spillover at these newly created interfaces [25]. This habitat destruction and fragmentation is a major cause of viruses jumping from wildlife to humans [28].

Industrial agriculture amplifies these risks through several specific mechanisms:

- Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs): These facilities house thousands of animals in close confinement, generating immense quantities of waste (1.4 billion tons annually in the U.S. alone) that contains high pathogen loads [27]. Waste storage lagoons can leak or rupture during storms, releasing pathogens and pharmaceuticals into water systems [27].

- Antibiotic Resistance: The extensive use of antibiotics in industrial agriculture contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance in environmental microorganisms, potentially creating reservoirs of drug-resistant genes that can be transferred to human pathogens [26].

- Nutrient Pollution: Runoff from fertilized fields carries excess nitrogen and phosphorus into water bodies, driving eutrophication that creates favorable conditions for pathogen survival and transmission [27].

Table 1: Agricultural Drivers of Zoonotic and Waterborne Disease Risk

| Agricultural Practice | Environmental Impact | Pathogen/Health Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Deforestation for Agriculture | Habitat destruction, wildlife-human interface expansion | Increased zoonotic spillover risk (e.g., novel viruses) [25] [28] |

| CAFO Waste Management | Surface and groundwater contamination with pathogens, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals | Multiple pathogens (100+ identified in swine waste); antibiotic resistance [27] |

| Synthetic Fertilizer Application | Eutrophication, algal blooms, hypoxia | Creation of pathogen-friendly environments; toxin production [27] |

| Pesticide Use | Soil and water contamination; disruption of aquatic ecosystems | Direct toxicity; ecosystem imbalance favoring disease vectors [24] |

Industrial Pollution and Microbial Ecology

Industrial discharges introduce complex mixtures of chemical pollutants into ecosystems, exerting selective pressures that reshape microbial communities and their functional attributes. The emerging field of microbial ecotoxicology investigates these interactions between pollutants and microorganisms, revealing several pathways through which industrial pollution influences disease risks [26].

Key mechanisms include:

- Pollution-Induced Community Tolerance (PICT): Exposure to chemical pollutants selects for tolerant microbial populations, often associated with decreased diversity and functional redundancy within ecosystems [26]. This loss of diversity may reduce the resilience of ecological systems to further disturbances and potentially create niches for pathogen establishment.

- Heavy Metal Selection Pressure: Industrial activities discharge heavy metals (e.g., mercury, lead, arsenic, cadmium) that persist in sediments and accumulate in aquatic organisms [29]. These metals can co-select for metal and antibiotic resistance in environmental bacteria, contributing to the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens [26].

- Biofilm Formation and Pathogen Protection: Chemical pollutants can stimulate biofilm formation in environmental bacteria, providing protected microenvironments where pathogens persist and potentially exchange genetic material, including antibiotic resistance genes [26].

The concept of "ecological costs of adaptation" illustrates the trade-offs wherein microbial communities that adapt to tolerate pollutants often experience a reduction in diversity and potentially a loss of functions important for ecosystem health [26]. This compromise to ecosystem integrity represents an indirect pathway through which industrial pollution may ultimately enhance disease transmission risks.

Water Pollution and Waterborne Disease Transmission

Water pollution creates direct pathways for human exposure to pathogens through contaminated drinking water, recreational activities, and consumption of contaminated seafood. The interface between industrial and agricultural pollutants and waterborne disease transmission involves both direct contamination with pathogens and indirect effects on aquatic ecosystems that favor disease transmission [30] [27].

Major transmission pathways include:

- Fecal Contamination: Inadequate sanitation and animal waste management introduce enteric pathogens directly into water sources [31] [30]. An estimated 1.1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water due to improper sanitation, resulting in approximately 2.2 million annual deaths from waterborne diseases [30].

- Nutrient-Driven Ecosystem Changes: Agricultural runoff rich in nitrogen and phosphorus drives eutrophication, leading to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and create "dead zones" where normal aquatic life cannot survive [27]. Some algal blooms produce biotoxins that directly harm human health, while others create environmental conditions that favor the survival and transmission of waterborne pathogens.

- Groundwater Contamination: Pathogens and pollutants from surface activities can infiltrate aquifers, creating persistent reservoirs of contamination in drinking water sources [30]. This is particularly concerning in areas relying on private wells, which are not regulated under EPA clean water standards and rarely undergo routine testing [27].

Table 2: Major Waterborne Pathogens and Their Environmental Sources

| Pathogen Category | Example Pathogens | Health Impacts | Primary Environmental Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella typhi, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli | Cholera, typhoid fever, gastroenteritis, hemorrhagic colitis | Human/animal waste, sewage overflows, agricultural runoff [31] [30] |

| Viral | Hepatitis A, Rotavirus | Hepatitis, gastroenteritis | Human fecal contamination, inadequate wastewater treatment [30] |

| Protozoan | Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Entamoeba histolytica | Giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, amoebic dysentery | Human/animal feces, contaminated surface water, sewage [31] [30] |

Quantitative Data on Environmental Drivers and Disease Burden

Systematic analysis of the relationship between environmental degradation and disease risk requires integration of quantitative data across multiple dimensions. The following tables summarize key metrics that enable researchers to quantify these relationships and prioritize intervention strategies.

Table 3: Quantitative Indicators Linking Agricultural Activity to Disease Risk

| Indicator | Measured Impact | Data Source/Region | Implications for Disease Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manure Generation | 1.4 billion tons/year from CAFOs in U.S. [27] | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | Massive reservoir of potential pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes |

| Nitrate Groundwater Contamination | 53% of Delaware groundwater >5 mg/L nitrates [27] | State groundwater surveys | Indicator of fecal contamination; direct health risk (methemoglobinemia) |

| Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone | 8,000+ square miles (variable by year) [27] | NOAA monitoring | Ecosystem disruption creating conditions favorable for pathogenic bacteria |

| Pesticide Runoff | 88% of waterborne illnesses linked to poor hygiene, sanitation, unsafe water [31] | WHO/UNICEF estimates | Chemical stressors on aquatic ecosystems; potential direct toxicity |

Table 4: Industrial Pollution Metrics with Health Implications

| Pollutant Category | Environmental Concentration | Ecological/Health Impact | Monitoring Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Variable by water body and metal (e.g., Hg, Pb, Cd) | Bioaccumulation in food chain; neurological, renal damage; co-selection for antibiotic resistance [29] | Atomic absorption spectroscopy, ICP-MS of water/sediments/biota |

| Nutrient Pollutants | N and P from fertilizers and detergents | Eutrophication, algal blooms, hypoxia, biodiversity loss [27] | Colorimetric analysis (spectrophotometry) of N, P compounds |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants | PCBs, dioxins, PAHs in sediments | Endocrine disruption, carcinogenicity, immune system suppression [30] | GC-MS, HPLC with appropriate detection methods |

| Pharmaceutical Residues | ng-μg/L range in surface waters | Antibiotic resistance development; physiological effects on aquatic organisms [26] | LC-MS/MS, immunoassay techniques |

Methodologies for Investigating Environment-Disease Relationships

Microbial Ecotoxicology Approaches

Investigating the interactions between environmental pollutants and microbial communities requires integrated methodologies that span molecular to ecosystem levels. The following experimental protocols provide frameworks for assessing how environmental degradation alters microbial communities and influences pathogen dynamics.

Protocol 1: Pollution-Induced Community Tolerance (PICT) Assessment

The PICT approach detects whether microbial communities have been exposed to and affected by pollutants, based on the principle that previously exposed communities develop increased tolerance to the contaminant of concern [26].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples (water, sediment, soil) from both reference (unpolluted) and contaminated sites.

- Community Exposure: Divide each sample into multiple aliquots and expose to a concentration gradient of the target pollutant (e.g., heavy metal, pesticide, antibiotic).

- Functional Response Measurement: Quantify microbial community function using:

- Substrate-Induced Respiration: Measure CO₂ production after adding an easily degradable substrate.

- Enzyme Activities: Assess hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., phosphatase, β-glucosidase) using fluorogenic substrates.

- Nitrogen Transformation: Measure potential nitrification rates.

- Dose-Response Modeling: Calculate EC₅₀ values (concentration causing 50% inhibition) for each sample.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare EC₅₀ values between reference and contaminated sites using t-tests or ANOVA. Significantly higher EC₅₀ values at contaminated sites indicate developed tolerance.

Interpretation: Developed tolerance in contaminated sites suggests that pollutants have exerted selective pressure, altering community composition and potentially ecosystem functioning. PICT is often associated with decreased microbial diversity, which may reduce functional resilience to additional stressors [26].

Protocol 2: Pathogen Survival and Transport in Agricultural Systems

This protocol assesses how agricultural practices influence pathogen persistence and movement through watersheds, critical for understanding waterborne disease risks.

Experimental Design:

- Source Tracking: Apply microbial source tracking (MST) markers (e.g., host-specific Bacteroidales, mitochondrial DNA) to identify contamination sources (human, bovine, poultry, swine).

- Mesocosm Studies: Establish controlled aquatic mesocosms simulating agricultural runoff conditions with varying:

- Nutrient levels (N, P from synthetic fertilizers)

- Organic matter content (from manure amendments)

- Turbidity (from soil erosion)

- Pathogen Inoculation: Introduce target pathogens (e.g., E. coli O157:H7, Cryptosporidium parvum) or appropriate surrogates at environmentally relevant concentrations.

- Persistence Monitoring: Sample water and sediment over time to quantify:

- Pathogen Survival: Using culture methods (for bacteria) and molecular detection (qPCR for viruses/protozoa).

- Genetic Markers: For antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., tetM, blaCTX-M) using qPCR.

- Transport Modeling: Apply hydrological models to predict pathogen movement through watersheds under different rainfall scenarios.

Analytical Methods:

- Culture-Based Enumeration: Membrane filtration with selective media for bacterial pathogens.

- Molecular Detection: DNA/RNA extraction followed by qPCR/qRT-PCR for pathogen quantification and viability assessment (using propidium monoazide pretreatment).

- Microbial Community Analysis: 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to assess overall microbial community shifts in response to agricultural pollutants.

Zoonotic Spillover Risk Assessment

Assessing the risk of zoonotic disease emergence at the agriculture-wildlife interface requires interdisciplinary approaches that integrate ecological, microbiological, and epidemiological methods.

Protocol 3: Landscape Epidemiology and Pathogen Surveillance

This protocol provides a framework for monitoring pathogen prevalence at human-wildlife-livestock interfaces created by agricultural expansion and environmental change [25].

Field Methods:

- Stratified Sampling Design: Establish transects across habitat gradients:

- Pristine habitat → Habitat edge → Agricultural land → Human settlements

- Multi-Host Sampling: Collect samples from:

- Wildlife: Small mammals (rodents, bats), birds, and other relevant reservoir species

- Livestock: Domestic animals at the interface (cattle, poultry, swine)

- Humans: High-risk populations (farm workers, hunters, rural communities)

- Sample Types: Blood (serology, molecular detection), feces (pathogen shedding), ectoparasites (ticks, fleas)

- Environmental Sampling: Soil, water, and vegetation at sampling sites

Laboratory Analysis:

- Pathogen Detection: Multiplex qPCR panels for known zoonotic pathogens

- Metagenomic Sequencing: For unbiased pathogen discovery in wildlife and environmental samples

- Serological Testing: ELISA or neutralization assays to detect previous exposure

- Whole Genome Sequencing: Of isolated pathogens to assess genetic relatedness across hosts and spatial locations

Data Integration:

- Geospatial Analysis: Map pathogen detections relative to landscape features (land use, vegetation cover, water sources)

- Statistical Modeling: Use generalized linear mixed models to identify environmental and ecological predictors of pathogen prevalence

- Network Analysis: Construct transmission networks based on pathogen genetic similarity and host movement data

Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Pathogen Detection