Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution: A 2025 Analysis of Sources, Assessment, and Mitigation

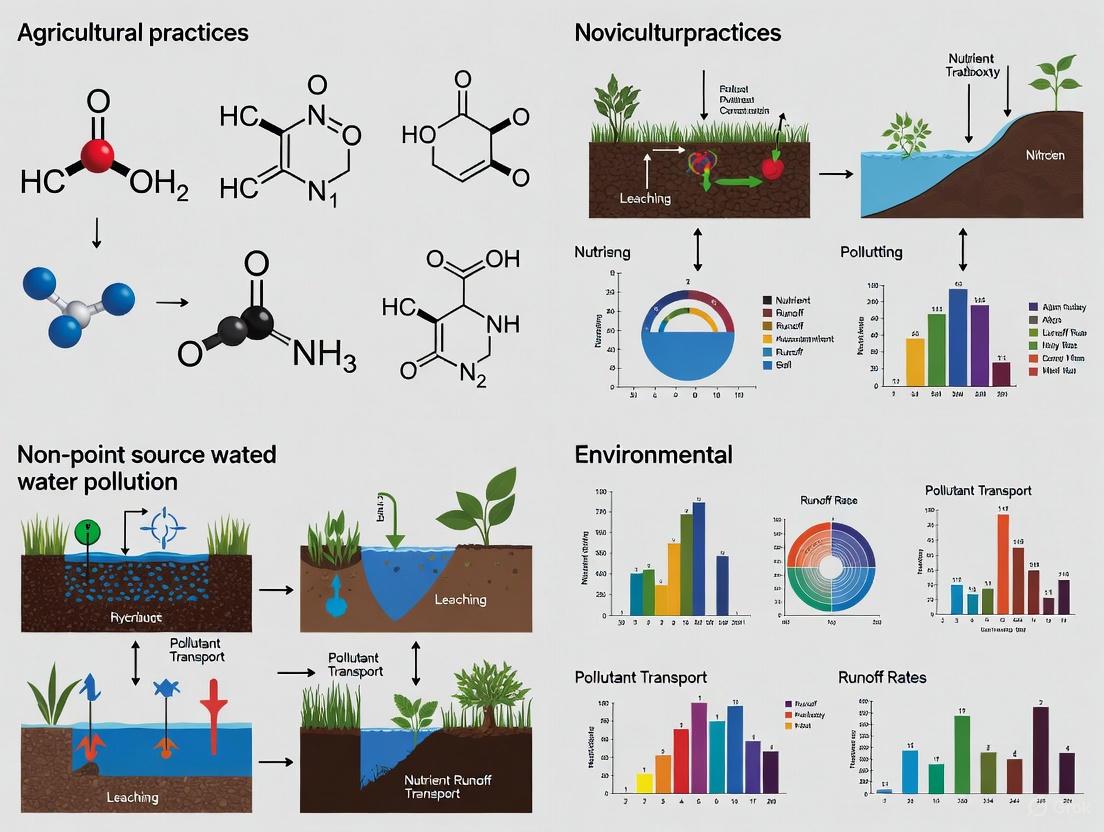

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of agricultural non-point source (ANPSP) pollution, a leading global cause of water quality degradation.

Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution: A 2025 Analysis of Sources, Assessment, and Mitigation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of agricultural non-point source (ANPSP) pollution, a leading global cause of water quality degradation. Tailored for researchers and scientific professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of nutrient, sediment, and emerging contaminant runoff. The scope spans advanced assessment methodologies, including AI, ML, and watershed modeling (SWMM), and evaluates the efficacy of Best Management Practices (BMPs) through validation studies. It further examines innovative remediation technologies and offers a comparative analysis of control strategies, synthesizing current research to guide future scientific and policy initiatives for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem protection.

Understanding the Scope and Impact of Agricultural Runoff

Defining Non-Point Source Pollution in an Agricultural Context

Non-point source (NPS) pollution, particularly from agricultural activities, represents a pervasive environmental challenge that threatens water security and ecosystem integrity globally. Unlike pollution from discrete, identifiable outlets, agricultural non-point source pollution (ANPSP) originates from diffuse sources across the landscape, making it notoriously difficult to monitor, quantify, and control [1]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms, impacts, and methodological frameworks for researching ANPSP, providing scientists and researchers with comprehensive tools for investigating this complex phenomenon within watershed systems.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency identifies NPS pollution as the leading remaining cause of water quality problems in the nation's waters [1]. With nearly 1.2 billion acres of land devoted to agriculture in the United States alone—approximately half the nation's total land area—farming activities constitute a dominant influence on hydrological systems [2]. The scale of agricultural chemical usage is substantial, with approximately half a million tons of pesticides, 12 million tons of nitrogen, and 4 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer applied annually to crops in the continental United States [2].

Defining Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollution

Conceptual Framework and Regulatory Definition

Non-point source pollution is legally defined in contrast to "point source" pollution as established in Section 502(14) of the Clean Water Act. Specifically, NPS pollution includes any source of water pollution that does not meet the definition of a "point source," which is characterized as "any discernible, confined and discrete conveyance" including pipes, ditches, channels, tunnels, or other discrete conduits [1].

Agricultural NPS pollution generally results from land runoff, precipitation, atmospheric deposition, drainage, seepage, or hydrologic modification [1]. Unlike controlled discharges from industrial or municipal treatment facilities, ANPSP originates from multiple diffuse sources across agricultural landscapes, transported primarily through hydrological processes as rainfall or snowmelt moves over and through the ground [1].

Primary Agricultural Pollutants and Pathways

The principal pollutants associated with ANPSP include nutrients, sediments, pathogens, pesticides, and salts, each with distinct environmental impacts and transport mechanisms.

Table 1: Major Agricultural Non-Point Source Pollutants and Their Impacts

| Pollutant Category | Specific Pollutants | Primary Agricultural Sources | Environmental Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients | Nitrogen, Phosphorus | Synthetic fertilizers, animal manure | Eutrophication, hypoxia, harmful algal blooms [2] [3] |

| Sediments | Soil particles, Suspended solids | Eroded cropland, unpaved roads, construction | Aquatic habitat destruction, turbidity, sediment deposition [1] [2] |

| Pathogens | Bacteria, Viruses | Livestock manure, faulty septic systems | Beach and shellfish bed closures, drinking water contamination [2] |

| Pesticides | Herbicides, Insecticides, Fungicides | Crop protection applications | Aquatic toxicity, drinking water contamination, wildlife impacts [2] |

| Salts | Sodium, Calcium, Magnesium salts | Irrigation practices | Soil salinization, water quality degradation [1] |

The transport mechanisms for these pollutants involve complex interactions between hydrological processes and agricultural landscapes. Rainfall and snowmelt transport the majority of these pollutants to surface waters, though other factors (e.g., cattle access to stream corridors, stream channel erosion) also contribute significantly to water quality degradation [2]. Pollutants can also infiltrate through soil profiles and contaminate groundwater resources, particularly in areas with vulnerable hydrogeological conditions [2].

Quantitative Assessment of Agricultural NPS Pollution

National and Global Scale Impacts

The National Water Quality Assessment demonstrates that agricultural runoff is the leading cause of water quality impacts to rivers and streams, the third leading source for lakes, and the second largest source of impairments to wetlands [2]. Recent assessments indicate approximately 46% of U.S. rivers and streams have excess nutrients, and only 28% are assessed as "healthy" based on their biological communities [2]. For lakes, 21% have high levels of algal growth and 39% have measurable levels of cyanotoxins—byproducts of certain bacterial species such as blue-green algae [2].

In China, according to the Second National Pollution Source Census Bulletin released in 2020, total nitrogen and total phosphorus emissions from agricultural sources reached 1.41 million tons and 0.21 million tons, respectively, accounting for 46.5% and 67.2% of the country's total water pollutant emissions [4]. This demonstrates the global significance of ANPSP as a primary contributor to water quality degradation.

Pollutant Loadings and Water Quality Correlations

The relationship between agricultural activity and water quality impairment follows dose-response patterns, though with substantial spatial and temporal variability due to confounding factors including soil type, climate, topography, and management practices.

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships Between Agricultural Activities and Water Quality Parameters

| Agricultural Stressor | Magnitude of Loading | Water Quality Response | Spatial Scale Documented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Fertilizer | 12 million tons applied annually (U.S.) [2] | Hypoxic conditions in receiving waters | Regional (e.g., Gulf of Mexico) |

| Phosphorus Fertilizer | 4 million tons applied annually (U.S.) [2] | Freshwater eutrophication | Lake watersheds |

| Soil Erosion | Varies by slope, management, precipitation | Sediment loading to rivers and reservoirs | Field to watershed scale |

| Pesticides | 500,000 tons applied annually (U.S.) [2] | Aquatic toxicity, drinking water standards exceedances | Groundwater aquifers, surface waters |

Methodological Frameworks for ANPSP Research

Remote Sensing and Monitoring Technologies

Remote sensing technology has emerged as a critical methodology for monitoring and assessing soil erosion and nutrient transport across multiple spatial and temporal scales [5]. The multi-spatial and temporal resolution of remote sensing data offers advantages in extracting key erosion factors, including land cover, rainfall intensity, and topographic parameters, making it indispensable for comprehensive ANPSP assessment [5].

Table 3: Remote Sensing Platforms and Applications in ANPSP Research

| Spatial Scale | Remote Sensing Platforms | Spatial Resolution | Primary ANPSP Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local/Micro-scale | WorldView, QuickBird, IKONOS, UAVs | < 5 meters | High-precision soil erosion maps, gully erosion monitoring, plot-scale mechanisms [5] |

| Regional Scale | Landsat series, Sentinel series, SPOT | 10-30 meters | Watershed-scale soil erosion risk assessment, land use change impacts [5] |

| Global Scale | MODIS, AVHRR | 250-1000 meters | Large-area soil research and mapping, global erosion hotspots [5] |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) provide particularly high-resolution data for plot-scale studies. Research demonstrates that UAV-acquired data combined with structure-from-motion (SfM) and multi-view stereo (MVS) algorithms can effectively identify erosion and sedimentation processes larger than 0.040 m, making them suitable for detailed agricultural erosion research [5].

Experimental Watershed Monitoring Protocols

Long-term watershed monitoring provides essential data for understanding ANPSP processes and evaluating conservation effectiveness. The USDA National Water Quality Initiative (NWQI) implements standardized monitoring protocols in high-priority agricultural watersheds to assess whether water quality and/or biological conditions related to nutrients, sediments, or pathogens from livestock have changed in response to conservation implementation [2].

Core Monitoring Parameters and Methods:

- Water Quality Sampling: Grab samples and automated sampling during storm events analyzed for nitrate, ammonium, total phosphorus, soluble reactive phosphorus, suspended sediments, and pesticides

- Biological Assessment: Benthic macroinvertebrate and fish community surveys as indicators of ecological condition

- Hydrological Monitoring: Continuous stream discharge measurements using calibrated flumes or weirs

- Conservation Practice Documentation: Geospatial inventory and field verification of implemented best management practices (BMPs)

The objective of NWQI instream monitoring is to establish cause-effect relationships between conservation implementation and measurable improvements in water quality parameters [2].

Modeling Approaches for NPS Pollution

Computational models represent essential tools for predicting ANPSP transport and evaluating scenarios intervention. The novel Non-Point Source Assessment Tool (NPSAT) exemplifies recent advancements—a physically based and computationally efficient framework for simulating groundwater flow and diffuse pollution/tracer transport processes [6]. This approach integrates regional-scale hydrologic models, high-resolution landscape recharge and pollution/tracer loading models, and well placement models with particle-tracking and reactive transport frameworks [6].

Key applications of NPSAT include groundwater age modeling, which refines understanding of aquifer porosities and flow velocities, and nitrate transport modeling, which evaluates contaminant movement and attenuation under varying agricultural practices [6].

Research Reagents and Analytical Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Methods for ANPSP Investigation

| Research Reagent/Analytical Tool | Technical Function | Application in ANPSP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Tracers (Rhodamine WT, Bromide ions) | Hydrological pathway delineation | Surface and subsurface flow path identification, residence time estimation |

| Stable Isotopes (δ¹⁵N, δ¹⁸O of NO₃) | Nutrient source fingerprinting | Discriminating between fertilizer, manure, and natural nutrient sources |

| Molecular Microbial Source Tracking (qPCR assays) | Fecal pollution source identification | Differentiating livestock from human fecal contamination in waterways |

| Soil Extractants (KCl, Mehlich-3, Bray-1) | Bioavailable nutrient quantification | Measuring plant-available nitrogen and phosphorus in agricultural soils |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs) | Pesticide detection | High-throughput screening of herbicide and insecticide concentrations |

| Ion Chromatography | Anion/cation quantification | Simultaneous measurement of multiple nutrient species in water samples |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry | Trace element analysis | Detection of heavy metals and micronutrients in soils and waters |

Management Interventions and Conservation Practice Systems

Evidence-Based Conservation Practices

Effective ANPSP control employs systems of conservation practices, often termed best management practices (BMPs), tailored to specific operation types, landscape conditions, soils, climate, and management activities [2]. These practices include both structural and non-structural approaches, many demonstrating high effectiveness at relatively low cost.

Nutrient Management: Comprehensive nutrient management practices include soil testing, crop-specific calibration, and timing applications to maximize uptake and minimize runoff [2] [3]. Research indicates that adopting nutrient management techniques—applying nutrients in the right amount, at the right time of year, with the right method and placement—significantly reduces nitrogen and phosphorus losses [3].

Conservation Tillage: Reducing tillage frequency and intensity helps improve soil health, reduce erosion, runoff and soil compaction, thereby decreasing nutrient transport to waterways [3]. Practices include no-till or conservation tillage to maintain residue cover, which also builds soil organic matter over time, enhancing water and nutrient retention capacity [2].

Vegetative Buffers: Planting trees, shrubs and grasses along field edges and water bodies helps prevent nutrient loss by absorbing or filtering out nutrients before they reach water bodies [3]. Research demonstrates that riparian buffers are particularly effective at removing nitrate from subsurface flows through plant uptake and microbial denitrification.

Watershed-Scale Implementation Frameworks

The USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service launched the National Water Quality Initiative (NWQI) in 2012 to address agricultural contributions to NPS pollution through targeted, watershed-scale implementation [2]. This partnership between NRCS, EPA, and state nonpoint source programs accelerates voluntary conservation practice adoption using funding from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), Clean Water Act Section 319 Program, and other resources [2].

A critical innovation in NWQI is the focus on implementing on-farm conservation systems that avoid, trap, and control runoff in high-priority watersheds, strategically targeting areas that have the greatest influence on water quality (i.e., critical source areas) [2].

The 4R Nutrient Stewardship framework (Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, Right Place) has been successfully implemented in regions experiencing severe eutrophication, such as the Lake Erie basin, demonstrating significant reductions in phosphorus loading when consistently applied at watershed scales [3].

Emerging Research Directions and Innovation

Precision Agriculture and Digital Conservation

Precision agriculture represents a paradigm shift from uniform field management to spatially variable, data-driven approaches that optimize resource use [7]. Variable Rate Technology (VRT) utilizes GPS, sensors, and data analysis to determine precise input requirements at specific locations within fields, applying fertilizers, pesticides, and water only where and when needed [7]. This targeted approach reduces waste and minimizes runoff while maintaining agricultural productivity.

Integration of advanced technologies, including remote sensing, GIS (Geographic Information Systems), and machine learning, further enhances farming precision [7]. Remote sensing provides synoptic views of crops, enabling identification of areas needing attention before problems become visually apparent, while machine learning algorithms analyze large datasets to improve decision-making in nutrient management and irrigation scheduling [7].

Zoning Management Frameworks

Given the spatial heterogeneity of agricultural systems and environmental vulnerabilities, zoning management approaches offer promising frameworks for targeted ANPSP control. Recent research proposes national-scale ANPSP zoning strategies that integrate ecological sensitivity, pollution load intensity, and agricultural production structures [4].

For instance, China has delineated seven distinct governance zones with tailored strategies:

- Middle and Lower Yangtze River: Implements 4R strategy (source reduction, process retention, nutrient reuse, water restoration) for intensive rice production and aquaculture

- Hilly Areas in the South: Focuses on runoff retention, integration of planting and breeding, and endpoint treatment for decentralized production systems

- Huang-Huai-Hai Region: Emphasizes groundwater protection through rational nitrogen management and agricultural waste recycling

- Northeast Plain: Promotes conservation tillage and clean production to protect black soil resources [4]

This zoning approach acknowledges regional differences in agricultural production modes, environmental vulnerabilities, and management capacities, enabling more efficient and cost-effective pollution control than uniform national approaches [4].

Integrated Watershed Management

Effective watershed-scale management requires understanding the complex array of stressors and underlying conditions unique to individual systems [8]. Research demonstrates that collaboration among all local partners benefits ecological conditions at landscape scales, particularly in watersheds with varied landownership and uses [8].

Social-network studies reveal that key landowners with strong linkages to other stakeholders can be pivotal in developing practitioner networks interested in preserving entire watersheds [8]. Additionally, protection measures designed to protect ecosystems must be coordinated across ownership boundaries, as fragmented applications compromise their effectiveness for targeted species-recovery goals [8].

Long-term monitoring datasets (e.g., 25 years of stream-habitat and watershed-condition data from the Northwest Forest Plan's Aquatic and Riparian Effectiveness Monitoring Program) show that forest and stream conditions recover over time with appropriate protection, though climate-linked disturbances are increasingly strong drivers of stream condition [8].

Agricultural non-point source pollution (ANPSP) represents a pervasive and complex challenge for global water quality, distinguished from point-source pollution by its diffuse origin and transport across the landscape [9] [1]. Non-point source pollution is defined as contamination derived from broad land areas, carried by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground, which picks up and transports natural and human-made pollutants into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters, and groundwater [1]. As the single largest user of global freshwater resources, accounting for approximately 70% of all surface water use, agriculture is both a cause and victim of water pollution [9]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the four primary pollutant categories—nutrients, sediments, pesticides, and pathogens—within the context of agricultural non-point source pollution, framing this discussion within the broader research on sustainable agricultural practices and water quality management.

The environmental and economic significance of ANPSP is substantial. In the United States, agricultural operations affect water quality through the extent of farm activities on the landscape, with agricultural runoff identified as the leading cause of water quality impacts to rivers and streams, the third leading source for lakes, and the second largest source of impairments to wetlands [2]. Globally, the pressure to produce sufficient food has resulted in expanded irrigation and steadily increasing use of fertilizers and pesticides to achieve and sustain higher yields, with consequent impacts on water resources [9]. This review synthesizes current research on pollutant sources, pathways, impacts, and assessment methodologies to provide researchers and scientists with a comprehensive technical foundation for addressing this multifactorial environmental challenge.

Pollutant Characterization and Environmental Impact

Nutrients (Nitrogen and Phosphorus)

Nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) constitute the primary nutrient pollutants originating from agricultural activities, with significant implications for aquatic ecosystem functioning. These nutrients enter water bodies through runoff and leaching, primarily from inorganic fertilizers, livestock manure, and leguminous crops [9] [2]. The overutilization of fertilizers and manure contributes substantially to water pollution, leading to eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, and degradation of aquatic ecosystems [10].

The quantitative impact of nutrient pollution is demonstrated through global monitoring data. In China's Taihu Basin, ANPSP accounts for 52% of phosphorus and 54% of total nitrogen loading, while in Italy, these contributions are 24% and 71%, respectively [10]. In the United States, approximately 12 million tons of nitrogen and 4 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer are applied annually to crops in the continental United States, with agricultural runoff contributing 10% of the nitrogen and 30% of the phosphorus load in the Mississippi River Basin [2] [10]. Nutrient utilization efficiencies highlight the magnitude of the problem, with recent data from China indicating nitrogen utilization efficiency at 30-35%, phosphorus at 10-20%, and potassium at 35-50%, leaving substantial residues available for environmental transport [10].

Table 1: Global Nutrient Pollution Indicators from Agricultural Sources

| Region | Nitrogen Contribution to Water Bodies | Phosphorus Contribution to Water Bodies | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| China (Taihu Basin) | 54% | 52% | Fertilizers, livestock waste [10] |

| Italy | 71% | 24% | Fertilizer application [10] |

| United States (Mississippi River) | 10% of total load | 30% of total load | Agricultural runoff [10] |

| European Danube River | ~55% of water pollution | ~55% of water pollution | Agricultural activities [10] |

Sediments

Sediment pollution represents the physical transport of soil particles from agricultural lands through water erosion processes. Improperly managed agricultural activities, including conventional tillage, bare soil exposure, and insufficient erosion control measures, significantly accelerate sediment delivery to water bodies [2] [1]. The environmental impacts of sediment pollution include aquatic habitat degradation through smothering of benthic organisms, impairment of fish spawning grounds, reduction of light penetration affecting photosynthetic organisms, and transport of adsorbed pollutants including nutrients and pesticides [2].

The United States National Water Quality Assessment identifies soil erosion as a primary stressor to water quality, with excessive sedimentation from erosion capable of overwhelming aquatic ecosystems and degrading coastal and marine ecosystems, including coral reefs [2]. Sediment fences, grass planting, conservation tillage, and buffer strips represent key management strategies for controlling sediment mobilization and transport from agricultural landscapes [11].

Pesticides

Pesticide pollution encompasses herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and other biocides used in agricultural production that are transported to water bodies through spray drift, surface runoff, and leaching. Approximately a half million tons of pesticides are applied annually to crops in the continental United States [2]. The environmental and health concerns associated with pesticide pollution include acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic organisms, contamination of drinking water supplies, and impacts on human health through exposure to pesticide residues [9] [2].

Older chlorinated agricultural pesticides have been implicated in a variety of human health issues and ecosystem dysfunction through their toxic effects on organisms, leading to international efforts to ban these worldwide as part of the protocol for Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) [9]. Pesticide runoff to streams can pose risks to aquatic life, fish-eating wildlife, and drinking water supplies, with certain compounds exhibiting persistence in the environment and bioaccumulation in aquatic food webs [2]. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies, including the use of beneficial insects and targeted application methods, represent important approaches for reducing pesticide loads in agricultural runoff [9] [11].

Pathogens

Pathogenic microorganisms originating from agricultural operations include bacteria, viruses, and protozoa primarily derived from livestock manure, poultry operations, and faulty septic systems [2] [1]. These contaminants enter water bodies through runoff from land-applied manure, direct deposition by livestock in streams, and inadequate manure storage or treatment systems. Pathogen pollution poses significant public health risks through contamination of drinking water supplies and recreational waters, with potential transmission of diseases to consumers and farm workers [9].

The World Health Organization estimates that five million people die annually from water-borne diseases, with agricultural sources contributing to this burden through pathogen contamination of water resources [9]. Bacteria and nutrients from livestock and poultry manure can cause beach and shellfish bed closures and affect drinking water supplies, representing a significant concern for both human health and economic activities [2]. Proper disposal of sewage from human settlements and manure from intensive livestock breeding represents a critical management priority for reducing pathogen loads from agricultural operations [9].

Table 2: Characteristics and Impacts of Primary Agricultural Pollutants

| Pollutant Category | Primary Agricultural Sources | Transport Mechanisms | Key Environmental Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients (N, P) | Chemical fertilizers, livestock manure, leguminous crops | Surface runoff, subsurface drainage, leaching | Eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, hypoxia, ecosystem degradation [2] [10] |

| Sediments | Soil erosion from croplands, pastures, eroding streambanks | Overland flow, channel erosion | Habitat destruction, reduced light penetration, transport of adsorbed pollutants [2] [1] |

| Pesticides | Herbicides, insecticides, fungicides applied to crops | Spray drift, surface runoff, leaching | Acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic life, drinking water contamination, human health risks [9] [2] |

| Pathogens | Livestock manure, poultry operations, faulty septic systems | Surface runoff, direct deposition, groundwater flow | Waterborne disease transmission, beach and shellfish bed closures [9] [2] |

Assessment Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Field-Scale Monitoring Approaches

Field-scale monitoring provides direct measurement of pollutant concentrations and loads from specific agricultural land uses and management practices. Effective monitoring protocols employ a combination of in-situ sensors, automated samplers, and manual sampling to characterize the temporal dynamics of pollutant transport.

Water Quality Sampling Protocol:

- Site Selection: Identify monitoring locations to represent specific land uses, soil types, and hydrological conditions. Include edge-of-field stations for agricultural fields and strategic positions in receiving streams.

- Flow Measurement: Install and maintain flow gauges (e.g., flumes, weirs, acoustic Doppler instruments) to continuously measure water discharge, enabling calculation of pollutant loads.

- Sample Collection: Deploy automated samplers programmed to collect samples based on flow stage, time, or precipitation triggers. Collect manual grab samples during baseflow conditions to complement automated sampling.

- In-Situ Sensors: Implement continuous monitoring sensors for parameters including turbidity (sediment proxy), nitrate, conductivity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen.

- Sample Analysis: Process samples according to standardized methods (e.g., EPA methods) for nutrient forms (NO₃-N, NH₄-N, TN, PO₄-P, TP), pesticide compounds, and pathogen indicators (E. coli, fecal coliform).

- Data Management: Establish quality assurance/quality control procedures for data collection, processing, and analysis.

Recent technological advances include the use of portable optical nitrate sensors for detecting nitrate pollution in drainage water and soil probes to evaluate nitrogen and phosphorus loss from agricultural fields, providing real-time data for nutrient management decisions [10].

Watershed-Scale Modeling Approaches

Watershed-scale models provide a computational framework for integrating landscape characteristics, agricultural management practices, and hydrological processes to simulate pollutant transport across spatial and temporal scales. These tools are essential for predicting the effects of management scenarios and identifying critical source areas for targeted interventions.

Commonly employed models include:

- Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT): A public-domain model that operates on a daily time step to predict the impact of land management practices on water, sediment, and agricultural chemical yields in large complex watersheds [10].

- Hydrological Simulation Program-Fortran (HSPF): A comprehensive watershed model that simulates hydrologic and water quality processes on pervious and impervious land surfaces and in streams and well-mixed impoundments [10].

- Annualized Agricultural Non-Point Source (AnnAGNPS) model: A continuous simulation, daily time step watershed-scale model developed to predict runoff, sediment, nutrient, and pesticide transport from agricultural watersheds [10].

- DeNitrification-DeComposition (DNDC) model: A process-based biogeochemistry model that simulates carbon and nitrogen cycling in agricultural systems, particularly useful for estimating greenhouse gas emissions and nitrate leaching [10].

These models investigate the interactions between slopes and channels among several components, including surface water, groundwater, soil erosion, hydrologic processes, sediment transport, and nutrient dispersion [10].

Watershed Modeling Framework

Emerging Technologies and Advanced Assessment Methods

Recent technological innovations offer new capabilities for monitoring and assessing agricultural non-point source pollution with improved spatial and temporal resolution. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) approaches are being integrated with traditional monitoring to identify complex patterns in pollutant transport and predict water quality responses to management interventions [10]. These methods can process large multivariate datasets from multiple monitoring platforms to identify critical source areas and optimize conservation practice implementation.

Internet of Things (IoT) applications in agriculture include networks of wireless sensors deployed across landscapes to provide real-time monitoring of soil moisture, nutrient levels, and weather conditions, enabling dynamic management decisions to reduce pollutant losses [10]. Remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), provide synoptic assessment of land use, vegetation cover, and even direct detection of certain water quality parameters like turbidity and algal blooms at the watershed scale.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for ANPSP Assessment

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Monitoring Equipment | Automated water samplers, flow gauges, in-situ sensors (nitrate, turbidity) | Continuous measurement of pollutant concentrations and hydrologic parameters | Edge-of-field monitoring, watershed-scale assessment [10] |

| Laboratory Analytical Methods | Ion chromatography (nutrients), GC-MS (pesticides), PCR (pathogens) | Quantitative analysis of specific pollutant compounds | Water sample analysis, method development and validation |

| Biogeochemical Models | SWAT, HSPF, AnnAGNPS, DNDC | Simulation of hydrologic and water quality processes | Watershed planning, scenario analysis, policy assessment [10] |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Satellite imagery (Landsat, Sentinel), UAVs (drones) | Spatial assessment of land use, vegetation, soil erosion | Watershed-scale mapping, change detection, model parameterization |

| Molecular Biology Tools | Microbial source tracking (MST) markers, qPCR assays | Identification and quantification of pathogen sources | Fecal pollution source identification, water quality monitoring |

Pollution Control and Management Strategies

Effective management of agricultural non-point source pollution requires a systems approach that integrates multiple conservation practices tailored to specific farming operations, landscape conditions, soils, and climate [2]. These strategies can be categorized into structural practices that involve physical modifications to the landscape and non-structural practices that emphasize management and behavioral changes.

Nutrient Management addresses nutrient runoff through application management, including soil testing, crop-specific calibration, and timing applications to maximize uptake and minimize runoff [2] [11]. Conservation Tillage practices, such as no-till or reduced tillage, leave crop residue from previous harvests while planting new crops, reducing soil erosion and helping nutrients and pesticides stay where they are applied [11]. These practices also improve soil health by building up organic material over time, which helps retain water and excess nutrients [2].

Buffer Strips and Vegetated Filter Strips planted between farm fields and water bodies effectively absorb soil, fertilizers, pesticides, and other pollutants before they can reach the water [11]. Constructed Wetlands represent another innovative approach in which areas are designed to slow runoff and absorb sediments and contaminants, while also providing habitat for wildlife [11].

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies reduce pesticide loads by employing beneficial insects to control agricultural pests, decreasing the need for chemical interventions [11]. Common predators include ladybugs, praying mantises, and spiders, which feed on aphids, mites, and caterpillars, helping to control infestations on valuable crops [11].

ANPSP Management Strategy Framework

The United States Department of Agriculture's National Water Quality Initiative (NWQI) exemplifies a targeted approach to addressing agricultural pollution, focusing on small high-priority watersheds and implementing on-farm conservation systems that avoid, trap, and control runoff [2]. This partnership between NRCS, EPA, and state nonpoint source programs accelerates voluntary conservation practice adoption to improve water quality using funding from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Clean Water Act Section 319 Program [2].

Agricultural non-point source pollution of nutrients, sediments, pesticides, and pathogens represents a complex environmental challenge that requires integrated, multidisciplinary approaches for effective management. The diffuse nature of these pollutants, their interconnections within agricultural landscapes, and their varied pathways to water bodies necessitate comprehensive assessment and tailored solutions. Current research demonstrates that while significant progress has been made in understanding pollutant sources and transport mechanisms, substantial gaps remain in monitoring technologies, predictive modeling, and implementation of conservation practices at appropriate scales.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing real-time monitoring capabilities through emerging technologies such as AI, machine learning, and IoT applications; improving the spatial and temporal resolution of watershed-scale models to better identify critical source areas; and developing more targeted conservation practices that simultaneously address multiple pollutants while maintaining agricultural productivity. The integration of economic incentives with technical solutions remains essential for encouraging widespread adoption of conservation practices by agricultural producers. By addressing these research priorities, the scientific community can contribute to more effective policies and management strategies that protect water resources while supporting sustainable agricultural production systems.

The Economic and Ecological Toll on Aquatic Ecosystems

Non-point source pollution from agricultural activities represents a primary cause of water quality impairment in freshwater and marine ecosystems globally [2]. The diffuse nature of this pollution, stemming from widespread farmland activities across nearly 1.2 billion acres in the United States alone, complicates both measurement and mitigation [2]. This whitepaper examines the multi-faceted impacts of agricultural runoff on aquatic systems, quantifying the economic consequences and ecological damage through synthesis of current research. The analysis encompasses the transport pathways of pollutants from farm fields to water bodies, the resultant ecosystem degradation, and the emerging technologies and management strategies aimed at mitigating these impacts within a broader research context on sustainable agricultural practices.

Quantifying the Pollutant Load

Agricultural operations contribute significantly to water quality impairments through the release of sediment, nutrients, pesticides, and pathogens. Approximately half a million tons of pesticides, 12 million tons of nitrogen, and 4 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer are applied annually to crops in the continental United States [2]. These substances do not remain stationary but are transported via runoff, infiltration, and irrigation return flows into local streams, rivers, and groundwater.

Table 1: Annual Agricultural Pollutant Load in the United States

| Pollutant Category | Estimated Annual Application/Release | Primary Ecological Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Fertilizer | 12 million tons | Stimulates algal blooms, creates hypoxic conditions |

| Phosphorus Fertilizer | 4 million tons | Freshwater eutrophication driver |

| Pesticides | 500,000 tons | Aquatic toxicity, drinking water contamination |

| Sediment | Not quantified in results | Smothers aquatic habitats, transports nutrients |

The National Water Quality Assessment identifies agricultural runoff as the leading cause of water quality impacts to rivers and streams, the third leading source for lakes, and the second largest source of impairments to wetlands [2]. The impacts vary regionally based on farm types, conservation practices, soils, climate, and topography.

Economic Consequences

The economic ramifications of agricultural water pollution extend across multiple sectors, including increased water treatment costs, fisheries depletion, tourism revenue losses, and healthcare expenses. The European Central Bank reports that ecosystem services provide substantial economic value, with ten ecosystem services in the EU28 generating €234 billion in annual benefits [12]. Degradation of these services directly impacts economic stability.

Table 2: Economic Impacts of Agricultural Water Pollution

| Impact Category | Economic Measure | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Macroeconomic Risk | GDP impact | Nature-related risks could result in a 12% loss to UK's GDP [13] |

| Financial Stability | Portfolio risk | Some banks could see portfolio value reductions of 4-5% due to nature-related risks [13] |

| Ecosystem Services | Annual value | Ten ecosystem services in EU28 worth €234 billion annually [12] |

| Disaster Mitigation | Cost avoidance | Coastal wetlands prevented $625 million in flood damages during Hurricane Sandy [12] |

Financial institutions are increasingly recognizing nature-related risks as material to their stability, with central banks highlighting how physical and transition risks from environmental degradation can affect price and financial stability through multiple transmission channels [12]. Soil erosion and loss of pollinators can impair agricultural productivity, pushing up food prices while simultaneously reducing land values and farmers' income [12].

Ecological Impacts

Eutrophication and Hypoxic Zones

Excess nutrients from fertilizers and livestock manure stimulate algal blooms in lakes, rivers, and coastal waters. As algae die and decompose, bacteria consume dissolved oxygen, creating hypoxic (low-oxygen) conditions that can approach zero concentration, effectively suffocating aquatic life [14]. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association has forecasted hypoxic zones in the Gulf of Mexico the size of Massachusetts, with size variability dependent on seasonal precipitation patterns [14].

In freshwater systems, phosphorus typically limits algal growth, while in coastal salt waters, nitrogen is normally the limiting nutrient [14]. This distinction is critical for targeting mitigation efforts. Agricultural areas with extensive artificial drainage are the primary source of nitrogen reaching coastal waters, while phosphorus primarily travels attached to sediment or dissolved in surface runoff [14].

Freshwater Ecosystem Degradation

Nationwide assessments reveal the extent of ecological impairment, with approximately 46% of rivers and streams having excess nutrients and only 28% classified as healthy based on their biological communities [2]. For lakes, 21% exhibit high levels of algal growth and 39% have measurable levels of cyanotoxins—byproducts of certain bacteria including blue-green algae [2]. These toxins compromise water quality and pose serious sanitation risks when they reach elevated growth levels [15].

Pollutant Persistence and Emerging Concerns

Beyond conventional pollutants, emerging concerns include the role of previously overlooked ingredients in agricultural products. Inactive components in herbicide formulations, such as amines used as stabilizing agents, may serve as important precursors for nitrogenous disinfection byproducts (DBPs) during water treatment [16]. These DBPs, including nitrosamines, pose serious health risks even at low concentrations.

Additionally, fecal contamination from livestock operations presents persistent challenges. Research demonstrates that decomposing cowpats on pasture maintain a substantial E. coli reservoir for at least five months, serving as a long-term source of microbial contamination [17]. This chronic contamination impacts both ecological integrity and human health risks.

Figure 1: Nutrient Pollution Impact Pathway

Monitoring and Assessment Technologies

Traditional vs. Advanced Monitoring Approaches

Traditional water quality monitoring involves site-specific sample collection with laboratory analysis, which provides accuracy but suffers from temporal gaps, high costs, and limited spatial coverage [18]. These limitations have driven the development of advanced monitoring technologies that enable more comprehensive assessment.

Table 3: Water Quality Monitoring Technologies Comparison

| Monitoring Approach | Key Parameters Measured | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sampling | Full suite of chemical/biological parameters | High accuracy for specific points | Time-consuming, limited spatial/temporal coverage |

| Remote Sensing | Chlorophyll-a, TSM, CDOM, turbidity | Large-scale, synoptic coverage | Requires atmospheric correction, indirect measurement |

| Sensor Networks | pH, DO, conductivity, temperature, turbidity | Real-time, continuous data | Biofouling, calibration requirements |

| AI-Integrated Systems | Multiple parameters via pattern recognition | Handles complex nonlinear relationships | Model training data requirements |

Remote Sensing and AI Integration

Remote sensing technology has demonstrated significant potential for addressing water quality monitoring challenges through efficient, large-scale, real-time acquisition of water quality distribution characteristics [18]. Satellite imagery from platforms such as Landsat, SPOT, Terra/Aqua/MODIS, and ENVISAT/MERIS, combined with retrieval algorithms, enables tracking of both optically active constituents (OACs) and non-optically active constituents (NOACs).

Artificial intelligence methods have revolutionized monitoring capabilities by handling complex nonlinear relationships between different spectral bands' apparent optical properties and various water quality parameter concentrations [18]. Machine learning approaches, including hybrid models like genetic algorithm-optimized support vector machines (GA-SVM), have demonstrated extremely high prediction accuracy (R² = 0.96580) for water quality trends [19].

Figure 2: Advanced Water Quality Monitoring System Architecture

Mitigation Strategies and Experimental Approaches

Agricultural Conservation Practices

Farmers can implement systems of conservation practices, often called best management practices (BMPs), to reduce pollutant runoff. These include both structural and non-structural approaches:

- Nutrient management through soil testing, crop-specific calibration, and timed applications to maximize uptake [2]

- Conservation tillage (no-till or reduced tillage) to leave soil surface undisturbed from harvest to planting, reducing runoff [2]

- Cover crops to uptake residual nutrients and improve soil health [2]

- Vegetated buffer strips around fields and streams to intercept runoff [2] [15]

- Edge-of-field practices including controlled drainage, denitrification bioreactors, and saturated buffers [14]

Research demonstrates that proper nitrogen fertilizer management alone will not solve the problem of excess nitrogen in surface waters [14]. Stacking multiple practices—including in-field management, edge-of-field interventions, and downstream restoration—can reduce nitrogen losses by 45% or more over current losses [14].

Circular Nutrient Management

Innovative approaches focus on circular nutrient management, such as the NuReCycle approach which integrates engineered vegetative buffer strips enhanced with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and plant beneficial bacteria (PBB) [15]. This myco-phytoremediation system enhances nutrient retention in soil, reduces runoff volume, promotes biodiversity, and increases plant biomass. The harvested biomass can be converted to biochar, which serves as an effective sorbent for dissolved and particulate nutrients from surface waterways [15]. The resulting nutrient-rich biochar can be repurposed as bio-fertilizer, creating a closed-loop system that optimizes fertilizer consumption and reduces depletion of finite phosphorus resources.

Policy Initiatives and Incentive Programs

The USDA National Water Quality Initiative (NWQI), launched in 2012, represents a partnership between NRCS, EPA, and state nonpoint source programs to accelerate voluntary conservation practice adoption in small high-priority watersheds [2]. Using funding from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Clean Water Act Section 319 Program, NWQI implements on-farm conservation systems that avoid, trap, and control runoff.

Internationally, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) has set targets including protection of at least 30% of the world's land and water by 2030 and reduction of harmful government subsidies by at least $500 billion per year [12]. The European Union's Nature Restoration Law similarly focuses on restoring degraded ecosystems, enhancing biodiversity, and improving climate resilience [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Aquatic Ecosystem Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Application in Research | Functional Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 24-ethylcoprostanol | Chemical fecal source tracking | Stable bovine-specific fecal steroid marker for tracking agricultural contamination [17] |

| Bacteroidales bovine-associated MST markers | Microbial source tracking | DNA-based targets for bovine fecal contamination using qPCR [17] |

| Chlorophyll-a extraction solvents | Phytoplankton biomass assessment | Quantification of algal abundance via spectrophotometry or fluorometry [18] |

| CDOM reference standards | Colored dissolved organic matter analysis | Calibration of optical measurements for organic matter transport [18] |

| Nutrient analysis reagents | Nitrogen/phosphorus quantification | Colorimetric determination of nutrient concentrations (e.g., cadmium reduction for nitrate) [18] |

| Biochar substrates | Nutrient capture and recycling | Porous carbon material for sorbing dissolved nutrients from agricultural runoff [15] |

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculants | Enhanced phytoremediation | Soil amendments to improve plant nutrient uptake in buffer strips [15] |

The economic and ecological toll of agricultural pollution on aquatic ecosystems represents a complex challenge requiring integrated solutions. The scale of impact—from hypoxic zones impairing commercial fisheries to treatment costs for contaminated drinking water—underscores the material significance of these issues for both ecological integrity and economic stability. Effective mitigation demands a systems approach combining in-field conservation practices, edge-of-field technologies, downstream restoration, and advanced monitoring capabilities. Emerging circular economy strategies that view nutrients as resources to be recovered rather than wastes to be managed offer promising pathways for reducing environmental impacts while maintaining agricultural productivity. Future research priorities should focus on optimizing practice effectiveness, improving monitoring technologies through AI integration, and developing economic incentives that align agricultural production with water quality protection.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in agricultural runoff represent a critical environmental challenge due to their extreme persistence, mobility in water systems, and potential for bioaccumulation. As agricultural land covers approximately 485 million hectares (1.2 billion acres) in the United States, it constitutes a significant non-point pollution source for water quality degradation [20]. Understanding the fate, transport, and remediation of these "forever chemicals" in agricultural contexts is essential for protecting water resources and human health, particularly within the framework of sustainable agricultural practices.

The environmental persistence of PFAS stems from their strong carbon-fluorine bonds, which resist natural degradation processes. This technical review examines current research on PFAS sources, transport mechanisms, analytical methodologies, and remediation strategies specific to agricultural environments, providing researchers and scientists with comprehensive data and experimental frameworks for addressing this complex contamination issue.

PFAS enter agricultural systems through multiple pathways, with contaminated runoff serving as a significant transport mechanism to surface and groundwater. Primary contamination sources include the land application of biosolids, irrigation with contaminated water, and atmospheric deposition from industrial sources [20] [21]. These initial inputs lead to PFAS accumulation in soils, creating long-term reservoirs that continuously release these compounds into water systems through runoff and leaching.

Biosolids application represents a particularly significant pathway. A 2025 study of ten northeastern U.S. farms demonstrated that biosolids-treated soils contained significantly higher PFAS concentrations compared to untreated control soils, with ∑40PFAS values ranging substantially across sites [22]. Wastewater treatment plants effectively concentrate PFAS from industrial discharges, household products, and commercial wastes, resulting in biosolids that reintroduce these contaminants to agricultural landscapes when applied as soil amendments.

Irrigation with PFAS-impacted water sources provides another major contamination pathway. Recycled water, particularly from wastewater treatment facilities, may contain PFAS at levels that lead to soil accumulation and subsequent crop uptake [23]. Additionally, aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) used at military bases and airports can migrate to adjacent farmlands, creating point sources for continued contamination [20] [23].

Table 1: Primary PFAS Sources in Agricultural Systems

| Source Category | Specific Pathways | Key PFAS Compounds | Contamination Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosolids | Land application of sewage sludge | diPAPs, FTMAPs, diSAmPAP | ∑40PFAS: 1.0-98 ng/g in treated soils [22] |

| Irrigation Water | Recycled wastewater, contaminated surface/groundwater | PFOA, PFOS, short-chain PFAS | Varies by source water quality |

| Industrial Sources | Aqueous film-forming foams, manufacturing discharges | PFOS, PFOA | Point source contamination |

| Atmospheric Deposition | Industrial emissions, volatile precursor compounds | Fluorotelomer alcohols | Regional background contamination |

Fate and Transport Mechanisms

PFAS behavior in agricultural environments is governed by complex fate and transport processes that influence their mobility, persistence, and ultimate impact on water quality. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting contamination spread and developing effective mitigation strategies [24].

Phase Partitioning and Soil Interactions

PFAS exhibit unique amphiphilic properties due to their hydrophobic fluorinated carbon tails and hydrophilic functional groups. This structure promotes accumulation at interfaces, including air-water and soil-water boundaries [24]. The soil partitioning behavior of PFAS is influenced by chain length, functional groups, soil organic matter content, and mineral composition. Shorter-chain PFAS (C < 6) demonstrate higher mobility in soil systems, while longer-chain compounds exhibit greater retention through hydrophobic interactions and sorption to soil organic matter [24].

Critical transport mechanisms include leaching to groundwater, surface runoff during precipitation events, and air-water interfacial transport in unsaturated soils. Recent research has highlighted the significance of PFAS retention at the air-water interface, a process that can substantially retard transport under unsaturated conditions but may be overcome during intense irrigation or precipitation events [24].

Transformation of Precursor Compounds

A crucial aspect of PFAS persistence in agricultural environments involves the biodegradation of precursor compounds into more stable terminal products. Polyfluorinated precursors, which constitute a substantial portion of PFAS in biosolids and other agricultural inputs, can transform through biological and abiotic processes into perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) such as PFOA and PFOS [25].

Microcosm studies conducted on PFAS precursor-contaminated agricultural soils have determined generation rate constants for short-chain perfluorocarboxyl acids (PFCAs) ranging from 0.02 to 0.50 year⁻¹, depending on specific PFAS compounds and soil physicochemical properties [25]. Principal component analysis indicates that acid phosphomonoesterase activity and microbial biomass significantly influence these production rates. This continuous transformation creates a long-term source of PFAS contamination, with studies indicating that production and release from precursor decay will continue for years to decades [25].

Figure 1: PFAS Fate and Transport Pathways in Agricultural Systems

Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Data

Field Sampling and Monitoring Approaches

Recent monitoring initiatives have employed innovative passive sampling technologies to characterize PFAS contamination in agricultural waterways. The Waterkeeper Alliance 2025 study utilized PFASsive passive samplers deployed upstream and downstream of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and biosolids application fields for at least 20 days, providing more accurate temporal data than traditional grab sampling [26]. This approach detected PFAS at 98% of sampled sites, with 95% of downstream WWTP locations and 80% of downstream biosolids application sites showing elevated concentrations compared to upstream locations [26].

A 2025 farm-scale investigation in Pennsylvania employed a paired control-treatment approach, collecting soil samples from two depths at biosolids-treated fields and control fields without biosolids history [22]. Researchers employed EPA Method 1633 to quantify 40 target analytes, including perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids, fluorotelomer sulfonic acids, and additional compounds. Soil physicochemical properties were characterized, and management history was obtained from farm operators to correlate with PFAS distribution patterns [22].

Table 2: PFAS Concentrations in Agricultural Matrices Based on 2025 Studies

| Matrix Type | PFAS Compounds | Concentration Range | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosolids-Treated Soils | ∑40PFAS | 1.0 - 98 ng/g | 10 Pennsylvania farms, 2025 [22] |

| Surface Water | Total PFAS | 106.51 - 228.29 ppt | Downstream of biosolids application sites [26] |

| Background Soils | ∑28PFAS | 0.40 - 6.6 ng/g | Swedish forest soils (reference) [22] |

| Agricultural Soils | PFOA + PFOS | 1.0 - 24 ng/g | Biosolids-amended soils [22] |

Laboratory Transformation Studies

Microcosm experiments investigating PFAS precursor biodegradation in agricultural soils provide critical data on long-term contamination potential. These studies employ targeted analysis via high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) and non-target screening using HPLC quadrupole time-of-flight (HPLC-QTOF) instrumentation [25]. The total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay is employed to quantify precursors through conversion to perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids, with repeated oxidations sometimes necessary to achieve complete fluorine mass balance in organic carbon-rich samples [25].

Experimental protocols typically involve:

- Soil characterization for physicochemical properties including organic carbon, pH, and enzyme activities

- Microcosm setup under controlled laboratory conditions

- Incubation monitoring with periodic sampling over extended durations

- Target and non-target analysis via LC-MS/MS and LC-QTOF

- Data analysis including principal component analysis to identify significant factors influencing transformation rates [25]

These experiments have demonstrated that short-chain PFAS will continuously leach from contaminated soils for decades, creating persistent contamination of adjacent environmental compartments [25].

Mitigation and Remediation Strategies

Biochar-Based Remediation Approaches

Biochar applications represent a promising strategy for PFAS mitigation in agricultural environments. Biochar—a stable, carbon-rich material produced through pyrolysis of organic waste—functions as an effective adsorbent through multiple retention mechanisms [20] [23]. Research indicates that biochar production parameters, particularly pyrolysis temperature and feedstock selection, significantly influence PFAS adsorption capacity. Higher temperatures generally create biochars with greater surface area and hydrophobic characteristics, enhancing PFAS removal efficiency [20].

The USDA Agricultural Research Service has identified three primary application strategies for biochar in PFAS mitigation:

- Soil amendment - Mixing biochar with contaminated soil to reduce PFAS mobility and bioavailability

- Water filtration - Implementing biochar-based systems to treat irrigation water before use

- Biosolid treatment - Incorporating biochar into biosolids to trap PFAS before land application [20]

Compared to traditional adsorbents like activated carbon or ion-exchange resins, biochar offers a cost-effective alternative with a smaller ecological footprint, making it particularly suitable for agricultural applications [20].

Figure 2: Biochar Optimization Parameters for PFAS Remediation

Agricultural Management Practices

Alternative mitigation approaches include crop selection strategies based on varietal differences in PFAS uptake. USDA researchers are identifying crop varieties that demonstrate resilience to PFAS accumulation, potentially enabling growers to select cultivars that minimize transfer into the human food chain [23]. Additionally, site-specific risk assessments and precision application techniques can help align PFAS management with circular economy principles while reducing contamination risks [21].

Water treatment technologies for agricultural operations include granular activated carbon (GAC) filtration and various resin-based systems that effectively bind PFAS compounds [27]. Emerging destruction technologies aimed at breaking the carbon-fluorine bond show promise for permanent PFAS destruction but require further development for agricultural implementation.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Significant knowledge gaps persist regarding PFAS behavior in agricultural systems. Key research priorities include:

- Long-term transformation kinetics of precursor compounds in diverse agricultural soils

- Plant uptake mechanisms and varietal differences across crop species

- Field-scale validation of biochar and other remediation technologies

- Impacts of co-contaminants on PFAS fate and transport

- Ecological and human health risks associated with chronic low-level exposure

The conflict between PFAS contamination and circular economy principles presents particular challenges for beneficial waste utilization practices like biosolids application [21]. Developing integrated management approaches that balance resource conservation with contamination prevention represents a critical research frontier.

Future research should prioritize standardized analytical methods, comprehensive monitoring programs, and validated remediation techniques specific to agricultural environments. Additionally, policy development must be informed by robust scientific evidence to effectively address PFAS contamination while maintaining agricultural productivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for PFAS Investigation in Agricultural Systems

| Research Tool | Specific Application | Technical Function | Example Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-MS/MS Systems | Target PFAS quantification | High-sensitivity detection at parts-per-trillion levels | EPA Method 1633 [23] [22] |

| HPLC-QTOF Instrumentation | Non-target screening & precursor identification | Comprehensive PFAS characterization with mass accuracy | Non-target identification of precursors [25] |

| PFASsive Passive Samplers | Field monitoring of water concentrations | Time-integrated sampling over extended deployments (≥20 days) | Waterkeeper Alliance monitoring [26] |

| TOP Assay Reagents | Precursor oxidation & mass balance assessment | Chemical conversion of precursors to measurable PFAAs | Fluorine mass balance studies [25] |

| Biochar Amendments | PFAS mobility reduction & adsorption studies | Soil and water remediation through multiple retention mechanisms | USDA biochar research [20] [23] |

| Microcosm Test Systems | Transformation rate studies under controlled conditions | Laboratory investigation of biodegradation kinetics | PFAS generation rate constant determination [25] |

Regulatory Framework and Policy Implications

Current regulatory approaches to PFAS in agriculture remain fragmented. In April 2024, the EPA established national drinking water limits for six PFAS chemicals, though recent announcements indicate reconsideration of standards for four compounds while retaining PFOA and PFOS limits [28]. The designation of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under CERCLA (Superfund) creates potential liability concerns, though EPA has indicated enforcement discretion for agricultural operations not intentionally contributing to contamination [28].

State-level responses vary significantly, with Maine implementing comprehensive testing programs and developing action levels for agricultural products (210 ppt for milk, 3.4 ppb for beef) [27]. This patchwork regulatory landscape complicates management approaches across jurisdictions, highlighting the need for scientifically-grounded federal standards specific to agricultural matrices.

USDA offers support programs including the Dairy Indemnity Payment Program for contaminated operations and conservation evaluation funding for PFAS testing through Natural Resources Conservation Service programs [28]. These initiatives represent initial steps toward addressing economic impacts on agricultural producers affected by PFAS contamination.

Advanced Tools for Monitoring and Modeling Pollution

Field- and Watershed-Scale Assessment Techniques

The management of agricultural non-point source pollution (ANPSP) is a critical global challenge, directly impacting water quality, ecosystem health, and food security. ANPSP refers to the pollution of water bodies by nutrients, sediments, and pesticides from diffuse sources such as farmland, making it difficult to monitor and regulate [29] [10]. Effective mitigation hinges on precise assessment techniques that operate at two fundamental, interconnected scales: the field-scale, which focuses on processes within individual plots of land, and the watershed-scale, which encompasses the entire land area draining into a common river or lake [10]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the assessment methodologies, models, and emerging technologies used by researchers and environmental professionals to quantify and manage ANPSP.

Field-Scale Assessment Techniques

Field-scale techniques are designed to understand and quantify the vertical and horizontal movement of water and pollutants at a high resolution within a specific agricultural field. These methods are essential for identifying specific pollution sources and validating the effectiveness of on-farm best management practices (BMPs).

Direct Measurement and Monitoring

Direct monitoring provides ground-truthed data on pollutant levels and hydrological processes.

- In-Situ Sensor Networks: Automated sensors can be deployed to provide continuous, real-time data on key water quality parameters [10]. These systems often include:

- Optical Nitrate Sensors: Portable sensors used to detect nitrate concentrations in drainage and pore water [10].

- Soil Probes: Used to evaluate the leaching losses of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) through the soil profile [10].

- Electromagnetic Sensors: Tools like Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) and Frequency Domain Reflectometry (FDR) are used to measure volumetric soil water content, a critical variable governing pollutant transport [30].

- Field Sampling and Analysis: Conventional methods involve collecting water (runoff, drainage) and soil samples for laboratory analysis. This includes measuring Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP), turbidity, and pesticide residues. Protocols emphasize rigorous chains of custody and quality control to ensure data integrity [31] [32].

Proximal Sensing and Geophysical Techniques

These methods allow for non-invasive investigation of sub-surface soil properties that influence pollutant transport.

- Electromagnetic Induction (EMI): Maps soil texture (relative proportions of sand, silt, and clay) and salinity variations across a field, which govern water retention and infiltration rates [30].

- Resistivity Methods: Provide 2D and 3D images of the subsurface, helping to identify areas of potential nutrient leaching or preferential flow paths [30].

- Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR): Used to characterize soil structure, map the depth to bedrock, and identify soil layers, all of which affect water movement [30].

Field-Scale Modeling

Models simulate the complex vertical exchanges of water, nutrients, and carbon between the soil and atmosphere.

- The DeNitrification–DeComposition (DNDC) Model: A well-established process-based model that simulates carbon and nitrogen biogeochemistry in agricultural ecosystems. It is particularly effective for estimating greenhouse gas emissions and nitrate leaching from specific fields [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these various field-scale assessment techniques, from data collection to application.

Watershed-Scale Assessment Techniques

Watershed-scale assessment is critical for understanding the cumulative impact of multiple pollution sources across a landscape. It integrates data from various fields and land uses to model hydrological pathways and pollutant loads at a basin level.

Watershed Modeling Frameworks

Numerical models are the primary tool for watershed-scale assessment, simulating the interplay of hydrology, sediment transport, and nutrient cycling.

- The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT): A widely used, public-domain model that operates on a continuous time step. SWAT is highly effective for predicting the long-term impacts of land management practices on water, sediment, and agricultural chemical yields in large, complex watersheds with varying soils, land use, and management conditions [33] [34] [10]. It can be calibrated and validated using remote sensing data like evapotranspiration (ET) and Leaf Area Index (LAI) [33].

- The Storm Water Management Model (SWMM): While traditionally used for urban drainage, SWMM has been successfully optimized and applied to simulate rainfall-runoff and NPS pollution processes in agricultural watersheds. It is particularly useful for quantifying spatio-temporal characteristics of TN and TP pollution and for simulating the effectiveness of various BMPs [29].

- Other Common Models:

- Hydrological Simulation Program-Fortran (HSPF): Used for simulating watershed hydrology and water quality for conventional and toxic organic pollutants [10].

- Annualized Agricultural Non-Point Source (AnnAGNPS) Model: A continuous simulation model used to estimate runoff, sediment, and nutrient loads from agricultural watersheds [10].

Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis

Remote sensing provides synoptic, repetitive coverage of the Earth's surface, making it invaluable for watershed-scale monitoring.

- Evapotranspiration (ET) Estimation: Satellite-derived ET is a key component of the water balance, used to calibrate models and assess crop water consumption [33] [30].

- Leaf Area Index (LAI) and Biomass: Indicators of crop health and growth stage, which influence nutrient uptake and water use [33] [30].

- Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Mapping: Essential for defining model input parameters and understanding how different land uses contribute to the pollutant load [35].

Table 1: Key Watershed-Scale Simulation Models and Their Applications

| Model Name | Primary Spatial Scale | Key Simulated Processes | Common Application in ANPSP |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWAT+ [34] | Watershed (Basin) | Water balance, sediment transport, nutrient cycling (N, P) | Quantifying impacts of climate change & land use on TN/TP loads; evaluating long-term BMP efficacy. |

| SWMM [29] | Urban & Natural Watershed | Rainfall-runoff, hydraulic routing, water quality | Simulating TN/TP pollution from mixed land-use watersheds; testing BMP scenarios for pollution reduction. |

| HSPF [10] | Watershed | Hydrology, sediment, water quality (incl. pesticides) | Comprehensive watershed analysis of conventional and toxic pollutants. |

| AnnAGNPS [10] | Agricultural Watershed | Runoff, sediment, nutrient load | Estimating pollutant loads from agricultural landscapes and identifying critical source areas. |

Integrating Field and Watershed Scales: Protocols and Data Governance

A cohesive assessment strategy requires integrating data across field and watershed scales. Standardized protocols and clear data governance are fundamental to this effort.

The Amazon Regional Monitoring Protocols, approved in 2025, provide a framework for such integration. They establish a common technical basis for water resource management across large basins [31]. The four protocols cover:

- Modernization and Operation of Stations: Guidelines for installing and operating monitoring stations in hydrological and water quality networks, including criteria for site selection and cooperation in transboundary areas [31].

- Field Data Quality: Harmonizes field sampling and analysis procedures, including equipment calibration and chains of custody, to ensure data reliability and integrity [31].

- Data Processing and Publication: Defines technical guidelines for data verification, storage, and public availability to democratize access to information [31].

- Data Governance: Establishes shared responsibilities where member countries are responsible for national data collection and publication, while a central body (e.g., ACTO) consolidates and disseminates regional information [31].

Quantitative Assessment of Best Management Practices (BMPs)

Simulation models are extensively used to quantify the effectiveness of BMPs before implementation. The following table summarizes findings from recent studies on the efficacy of different BMPs in reducing nutrient loads.

Table 2: Effectiveness of Simulated Best Management Practices (BMPs) on Nutrient Reduction

| BMP Category | Specific Practice | Average TN Reduction | Average TP Reduction | Study Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Management [29] | Precision fertilization, timing & rate control | 8.03% - 10.07% | 5.28% - 10.26% | Includes practices like soil testing and crop-specific calibration. |

| Landscape Management [29] | Vegetative buffer strips, contour farming | 5.28% - 10.26% | Not Specified | Effective at trapping sediment and particulate P. |

| Combined Practices [29] | Integrated nutrient & landscape management | 19.34% | 16.34% | Demonstrates synergistic effects of a systems approach. |

| Future Scenario (BMPs) [34] | Precision fertilization & vegetative strips | TN load lower than baseline (2071-2100) | Not Specified | Projected long-term mitigation under climate change scenarios (SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, tools, and technologies essential for conducting field- and watershed-scale ANPSP research.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Technologies for ANPSP Assessment

| Tool / Technology Category | Specific Item | Primary Function in ANPSP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Field Monitoring Equipment | Optical Nitrate Sensor [10] | Provides in-situ, continuous measurement of nitrate concentrations in soil water and drainage. |

| Soil Moisture Probes (TDR, FDR) [30] | Measures volumetric water content in the soil profile to understand hydrologic fluxes. | |

| Automatic Water Samplers | Collects water samples from streams or runoff during storm events for later lab analysis of TN, TP, etc. | |

| Geophysical Instruments | Electromagnetic Induction (EMI) Sensor [30] | Maps spatial variability of soil properties (texture, salinity) that control water and solute movement. |

| Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) [30] | Characterizes subsurface soil structure, stratigraphy, and depth to bedrock. | |

| Modeling & Computational Tools | SWAT/SWMM+ Software [33] [29] [34] | Open-source modeling platforms for simulating watershed hydrology and pollutant transport. |

| GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) [35] | Processes and analyzes spatial data on topography, land use, and soils for model input and result mapping. | |

| Remote Sensing Data | MODIS/Landsat/Sentinel-2 Imagery [33] [35] | Provides regional-scale data for estimating Evapotranspiration (ET), Leaf Area Index (LAI), and land cover. |

The precise assessment of agricultural non-point source pollution demands a multi-scale approach, leveraging both field-based measurements and watershed-scale modeling. Field-scale techniques provide the high-resolution data necessary to understand fundamental processes and validate practices, while watershed-scale models offer the predictive capacity to manage cumulative impacts. The integration of these approaches is being revolutionized by emerging technologies, including AI, IoT, and advanced remote sensing, which enable more real-time, accurate, and accessible monitoring. As the global challenge of ANPSP intensifies under pressures of climate change and food demand, the continued refinement and application of these field- and watershed-scale assessment techniques will be paramount in developing effective, evidence-based strategies for protecting our vital water resources.

Leveraging AI, Machine Learning, and IoT for Predictive Monitoring

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and the Internet of Things (IoT) is revolutionizing the predictive monitoring of non-point source (NPS) water pollution from agricultural activities. These technologies enable a shift from reactive, traditional methods to a proactive, data-driven paradigm capable of real-time anomaly detection, accurate pollutant load prediction, and precise assessment of conservation practice effectiveness. This transformation is critical for safeguarding water resources, ensuring sustainable agricultural production, and supporting the health of aquatic ecosystems. This technical guide details the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and technological synergies that form the foundation of these advanced monitoring systems, providing researchers and scientists with a framework for implementation and future innovation.