Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI): A Comprehensive Guide for River Basin Assessment and Management

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) as a critical tool for river basin assessment.

Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI): A Comprehensive Guide for River Basin Assessment and Management

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) as a critical tool for river basin assessment. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals, it covers the foundational principles, historical evolution, and core components of CWQI. The content details step-by-step methodologies for calculation and application, supported by global case studies from river basins like the Ganga, Arno, and Citarum. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, including the role of machine learning and sensitivity analysis. Finally, the article offers a framework for validating and comparing different water quality indices to ensure robust and reliable water quality assessments, equipping professionals with the knowledge to implement effective water resource management strategies.

Understanding Chemical Water Quality Index: Core Concepts and Historical Evolution for River Health

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) represents a sophisticated methodological framework designed to transform complex water chemistry data into a simple numerical value for assessing water quality status. As global challenges of water scarcity and pollution intensify, the CWQI has emerged as a critical decision-support tool for environmental managers, policymakers, and researchers. This technical guide examines the purpose, developmental evolution, computational methodologies, and practical applications of CWQI, with particular emphasis on its implementation in river basin assessment research. By providing a standardized approach to water quality evaluation, CWQI enables comparative analysis across temporal and spatial dimensions, facilitates identification of contamination hotspots, and supports sustainable water resource management strategies in the context of increasing anthropogenic pressures and climate change impacts.

Water quality indices have served as fundamental assessment tools since their initial development in the 1960s, providing a mechanism to simplify complex water quality data into accessible information for diverse stakeholders [1]. The foundational concept was established by Horton in 1965, who pioneered a system for rating water quality through index numbers to support water pollution abatement efforts [1]. This pioneering work established the basic framework for subsequent indices, initiating a field that has evolved significantly over decades to address emerging environmental challenges and regulatory requirements.

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) represents a specialized category of water quality indices focused specifically on chemical parameters, excluding biological indicators. This focus makes it particularly valuable for tracking chemical contamination trends, identifying pollution sources, and evaluating the effectiveness of remediation strategies [2]. Contemporary implementations of CWQI build upon this historical foundation while incorporating advanced statistical methods and region-specific adaptations to enhance their accuracy and applicability across diverse environmental contexts [1].

The Purpose and Significance of CWQI

Core Objectives in Water Resource Management

The implementation of CWQI serves multiple interconnected purposes within comprehensive water resource management frameworks. Primarily, it functions as a communication tool that translates complex chemical data into accessible information for policymakers and the public, thereby bridging the gap between scientific monitoring and environmental decision-making [2]. The index provides a standardized approach for tracking water quality evolution along river courses, identifying contamination hotspots, and assessing the contribution of different chemical constituents to overall water quality degradation [2].

Additionally, CWQI enables the evaluation of long-term trends in relation to environmental policies and regulatory interventions, allowing stakeholders to determine whether management strategies are effectively maintaining or improving water quality despite increasing anthropogenic pressures [2]. This temporal tracking capability was demonstrated in the Arno River Basin study in Italy, where CWQI analysis revealed that water chemistry remained relatively stable over three decades despite growing human impacts, suggesting that regulatory measures helped prevent further degradation [2].

Strategic Significance in Environmental Management

The significance of CWQI extends beyond mere monitoring to active management support. By providing a quantitative basis for comparison, CWQI enables prioritization of remediation efforts and allocation of limited resources to areas of greatest concern [3]. The index serves as an early warning system for emerging contamination issues, allowing for proactive intervention before ecosystem damage becomes irreversible [2]. Furthermore, CWQI supports compliance monitoring with water quality standards and regulations, providing a transparent metric for regulatory agencies and regulated entities alike [3].

In the context of sustainable development goals, CWQI contributes directly to targets related to clean water and sanitation, sustainable cities and communities, climate action, and life below water [3]. The index provides a measurable indicator for assessing progress toward these international commitments, making it increasingly relevant in global environmental governance frameworks.

Methodological Framework of CWQI

Fundamental Calculation Principles

The development of CWQI follows a structured methodological process that transforms raw chemical data into a comprehensive index value. While specific implementations may vary, the general framework typically involves four key stages that ensure consistency and reliability in water quality assessment [1]:

- Parameter selection: Identification of relevant chemical parameters based on monitoring objectives, regional characteristics, and data availability.

- Data transformation: Conversion of parameter concentrations to a common scale using standardized functions.

- Weight assignment: Allocation of relative importance factors to different parameters based on their environmental or health significance.

- Mathematical aggregation: Integration of transformed and weighted parameters into a single index value using appropriate computational techniques.

Parameter Selection Criteria

The initial phase of CWQI development involves selecting appropriate chemical parameters that collectively provide a comprehensive picture of water quality. Selection criteria typically consider parameters' environmental significance, health implications, and relevance to specific pollution sources in the study area. Common parameters incorporated in CWQI models include both conventional indicators and specific contaminants of concern:

Table 1: Essential Chemical Parameters for CWQI Development

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Environmental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Major Ions | Chloride, Sodium, Sulphate | Indicator of salinity, industrial, and agricultural pollution [2] |

| Oxygen Balance | Dissolved Oxygen, BOD, COD | Measures organic pollution and ecosystem health [1] |

| Nutrients | Nitrates, Phosphates, Ammonia | Indicates agricultural runoff and eutrophication risk [4] |

| Physical-Chemical | pH, Electrical Conductivity, TDS | Fundamental water chemistry characteristics [5] |

| Heavy Metals | Iron, Manganese, Zinc, Copper | Industrial contamination and toxicity assessment [4] |

Computational Methodologies

Various mathematical approaches have been developed for aggregating parameter data into a unified index value. The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) WQI method has gained international recognition and has been endorsed by the United Nations Environmental Program as a model for Global Drinking Water Quality Index [6]. The CCME WQI employs a structured approach based on three factors:

- Scope (F1): Represents the percentage of parameters that do not meet water quality guidelines.

- Frequency (F2): Indicates the percentage of individual tests that do not meet guidelines.

- Amplitude (F3): Measures the extent to which failed tests exceed guidelines.

The final index value is calculated using the formula:

CCME WQI = 100 - [√(F1² + F2² + F3²) / 1.732]

The divisor 1.732 normalizes the resulting values to a range between 0 and 100, where higher values indicate better water quality [6].

Alternative aggregation methods include additive approaches (weighted sum of sub-indices), multiplicative models (product of sub-indices), and logarithmic functions that can accommodate parameters with wide concentration ranges [1]. The choice of aggregation method significantly influences the sensitivity of the index to extreme values and its ability to represent overall water quality accurately.

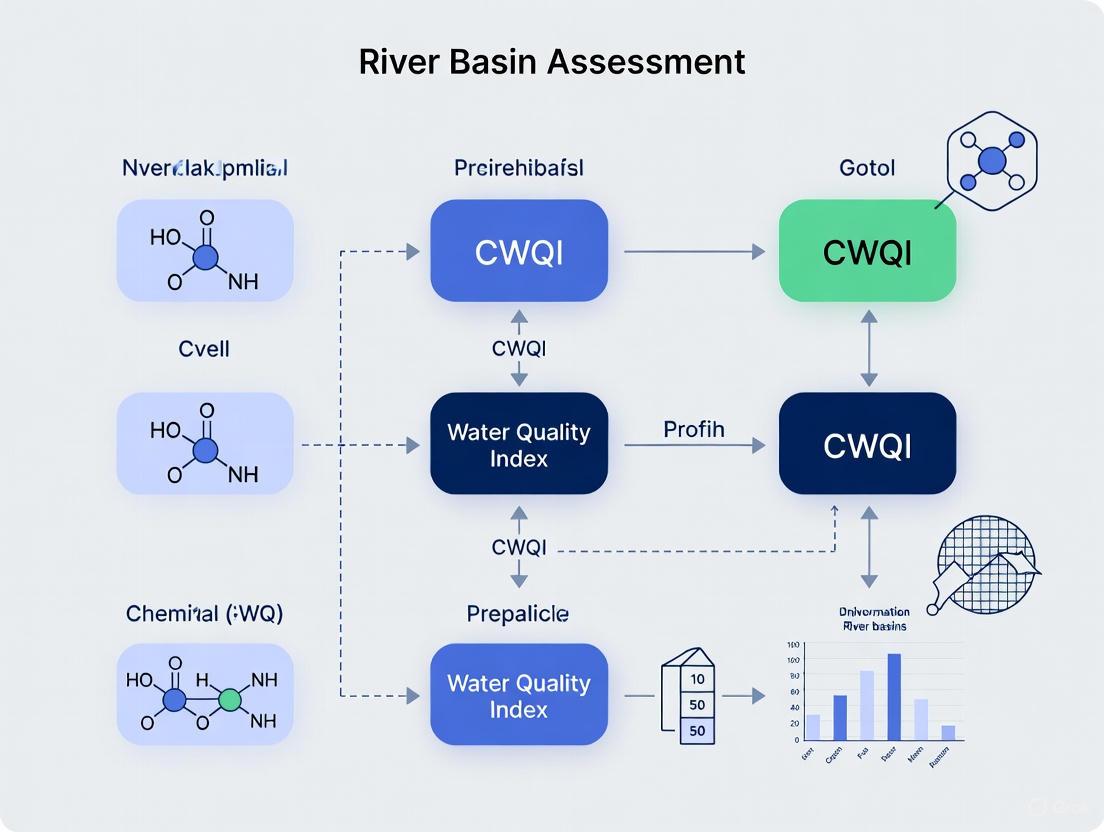

Diagram: Computational Workflow for CWQI Determination. This flowchart illustrates the systematic process for calculating CWQI, from initial parameter selection through final quality classification, including the primary methodological approaches used in aggregation.

Comparative Analysis of Water Quality Indices

Distinctive Features of CWQI

The CWQI differs from other water quality indices through its specific focus on chemical parameters and its adaptable framework that can be customized to regional priorities and specific water use purposes. Unlike biological indices that assess ecosystem health through aquatic organism communities, or physical indices that focus on characteristics like turbidity and temperature, CWQI specifically targets chemical contaminants that may pose risks to human health, aquatic life, or industrial processes [7].

A comparative study of various indices applied to the Lower Danube region demonstrated that different indices applied to the same dataset could yield varying water quality classifications due to differences in their underlying algorithms and parameter weighting schemes [8]. The CWQI results were particularly influenced by parameters with low maximum allowable concentrations, such as heavy metals and nitrites, making it especially sensitive to specific contaminant types [8].

Regional Adaptations and Specific Implementations

The flexibility of the CWQI framework has led to numerous regional adaptations designed to address local environmental conditions and pollution concerns. These include the Malaysian WQI (MWQI), the West Java Water Quality Index (WJWQI) in Indonesia, and various national implementations that incorporate regionally significant parameters and locally appropriate water quality standards [1].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Water Quality Index Models

| Index Type | Key Parameters | Aggregation Method | Scale Range | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CWQI (Canadian) | Variable selection based on objectives | CCME method (F1, F2, F3 factors) | 0-100 | Multipurpose water quality assessment [6] |

| NSF WQI | DO, fecal coliforms, pH, BOD, nitrates, phosphates, temperature, turbidity, total solids | Additive with expert weighting | 0-100 | General water quality rating [1] |

| Oregon WQI | DO, BOD, pH, temperature, total solids, nitrates, total phosphates | Unweighted harmonic square mean | 0-100 | Watershed management effectiveness [4] |

| British Columbia WQI | Variable based on monitoring program | Object-based with exceedance frequency | 0-100 | Compliance with water quality objectives [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Standardized Monitoring Framework

Implementing CWQI requires a structured approach to water sampling, chemical analysis, and data processing to ensure consistency and comparability of results. The monitoring protocol should be designed to capture spatial and temporal variations in water quality, with sampling frequency and location selection based on the specific objectives of the assessment [5].

Sampling Design Considerations:

- Spatial coverage: Sampling stations should represent different segments of the water body (upstream, midstream, downstream) and areas influenced by known pollution sources [2].

- Temporal frequency: Seasonal variations should be captured through regular monitoring, with consideration of high-flow and low-flow conditions [5].

- Quality control: Field blanks, duplicate samples, and standard reference materials should be incorporated to ensure data quality and analytical precision.

Analytical Methods for Key Parameters

Standardized analytical procedures are essential for generating reliable data for CWQI calculation. The following table outlines essential research reagents and methodologies for determining key parameters in CWQI assessment:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Methods for CWQI Parameters

| Parameter | Standard Analytical Method | Key Reagents/Solutions | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen | Electrochemical probe method [4] | Electrolyte solution, membrane | Assessment of oxygen balance and ecosystem health |

| Heavy Metals | Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry [7] | Metal-specific lamps, nitric acid for preservation | Detection of toxic metal contamination |

| Nutrients | Molecular absorption spectrophotometry [7] | Cadmium reductant, NEDD, sulfanilamide | Eutrophication potential assessment |

| pH | Electrometric method [4] | pH buffer solutions for calibration | Fundamental water chemistry characteristic |

| Chloride | Ion chromatography [4] | Carbonate/bicarbonate eluent | Salinity and contamination indicator |

Data Processing and Validation

Following chemical analysis, data must undergo rigorous validation and processing before CWQI calculation. This includes checking for analytical errors, applying appropriate detection limits for non-detect values, and normalizing data distributions when necessary. Statistical techniques such as hierarchical cluster analysis have been successfully employed to identify spatial patterns and validate the formation of meaningful water quality clusters [9].

Advanced modeling approaches, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Multi Linear Regression (MLR) models, have shown promise in predicting CWQI values based on limited parameter sets, potentially reducing monitoring costs while maintaining assessment accuracy [9]. These computational methods can enhance the efficiency of CWQI implementation in large-scale or long-term monitoring programs.

Case Studies and Practical Applications

River Basin Assessment Applications

CWQI has been extensively applied in river basin assessments worldwide, providing valuable insights into spatial and temporal water quality patterns. In the Arno River Basin (Italy), CWQI implementation demonstrated a clear deterioration gradient from upstream to downstream sections, with significant quality decline downstream of urban and industrial centers, primarily linked to chloride, sodium, and sulphate inputs from anthropogenic activities [2].

Similarly, a study on the Olt River in Romania utilized CWQI to classify water quality across different river segments, identifying values ranging from "fair" to "good" in various sections [5]. The index successfully captured spatial variations attributable to different anthropogenic influences along the river course, demonstrating its utility in identifying pollution hotspots and prioritizing management interventions.

Industrial and Specialized Applications

Beyond general river assessment, CWQI has proven valuable in specialized industrial contexts where water quality directly impacts operational efficiency and equipment integrity. At the Atinkou Thermal Power Plant in Côte d'Ivoire, CWQI was employed to evaluate borehole water quality used for cooling processes [7]. The assessment revealed a significant deterioration in water quality between 2019 (CWQI = 0.70, acceptable quality) and 2024 (CWQI = 0.05, poor quality), indicating increasing corrosion risks to plant equipment and highlighting the need for enhanced water treatment [7].

This industrial application demonstrates how CWQI can be adapted to address specific water use requirements beyond environmental protection, extending to industrial process maintenance and infrastructure protection.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Current Methodological Constraints

Despite its widespread utility, CWQI has several inherent limitations that must be acknowledged in research applications. The index's simplification of complex data inherently results in information loss, as multiple parameters are aggregated into a single value [9]. This can mask important patterns in individual parameters that might be critical for specific applications. Additionally, CWQI results are sensitive to the selection of parameters, weighting schemes, and aggregation methods, potentially leading to different assessments of the same water body using alternative approaches [8].

The focus on chemical parameters alone represents another limitation, as it does not capture biological integrity or ecosystem health directly. As noted in the Arno River Basin study, future developments should aim to integrate CWQI with biological indicators to provide a more comprehensive assessment of aquatic ecosystem health [2].

Emerging Innovations and Enhancement Opportunities

Future research directions for CWQI development focus on addressing current limitations while enhancing applicability to emerging environmental challenges. Promising areas include:

- Integration with advanced statistical models: Machine learning approaches like Artificial Neural Networks have shown potential for improving CWQI prediction accuracy and identifying non-linear relationships between parameters [9].

- Inclusion of emerging contaminants: Expanding parameter lists to include pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and other contaminants of emerging concern.

- High-resolution temporal assessment: Utilizing automated monitoring networks to capture seasonal and event-driven variations in water quality [2].

- Climate change resilience assessment: Adapting CWQI frameworks to evaluate water quality vulnerability to climate-induced changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and flow regimes.

The continued refinement of CWQI methodologies will enhance their value as scientific tools while maintaining their utility as communication devices for stakeholders across technical and non-technical backgrounds.

The Chemical Water Quality Index represents a sophisticated yet accessible methodology for assessing and communicating the chemical status of water resources. By transforming complex multivariate data into a single numerical value, CWQI enables efficient comparison across spatial and temporal scales, supports targeted management interventions, and facilitates communication between scientists, policymakers, and the public. Its flexibility allows adaptation to diverse geographical contexts and specific water use requirements, from ecological protection to industrial applications.

As freshwater resources face increasing pressures from anthropogenic activities and climate change, the role of robust assessment tools like CWQI becomes increasingly critical. Future methodological enhancements, particularly through integration with biological assessment approaches and advanced computational techniques, will further strengthen the index's utility as a comprehensive water resource management tool. For researchers engaged in river basin assessment, CWQI provides a standardized framework that supports scientifically defensible decisions while promoting sustainable water management practices across local, regional, and global scales.

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) represents a cornerstone methodology in environmental sciences, providing researchers and water resource managers with a vital tool for quantifying the complex chemical status of water bodies. For river basin assessment research, these indices transform extensive and often cumbersome chemical data into a single, comprehensible value, enabling efficient communication of water quality status to stakeholders and supporting informed decision-making [2] [1]. The evolution of Water Quality Indices (WQIs) from simple conceptual frameworks to sophisticated analytical tools mirrors the growing understanding of aquatic chemistry and the increasing pressures of global change and anthropogenic activity on freshwater resources [2] [10]. This whitepaper delineates the historical development of WQIs, details the core methodological protocols for their calculation, and explores their application in contemporary research, providing scientists with a technical foundation for their implementation in river basin studies.

The Historical Evolution of Water Quality Indices

The development of Water Quality Indices spans over half a century, marked by significant methodological refinements and the creation of indices tailored to specific regional and application needs. The following timeline and table summarize the key milestones in the evolution of the water quality index concept.

Figure 1: Historical Progression of Key Water Quality Index Models

The foundational work was established by Horton in 1965, who introduced the first systematic method for rating water quality using index numbers [1] [10]. His approach was designed as a comparative tool for evaluating water pollution abatement programs. Horton selected ten variables, including dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, coliforms, and specific conductance, established a rating scale for each, and assigned relative weighting factors to reflect their importance. The final index was a weighted sum of the sub-indices [10].

Subsequent developments saw significant contributions from Brown et al. (1970), who developed a WQI based on the professional opinions of 142 water quality experts [1] [10]. This index initially used nine variables and an arithmetic aggregation function. Recognizing the need for an index that was more sensitive to individual parameters exceeding norms, Brown et al. (1973) later refined their model to employ a geometric aggregation function. This work was supported by the U.S. National Sanitation Foundation (NSF), leading to the widely adopted NSFWQI [1] [11] [10].

Over the decades, numerous other indices were developed worldwide, adapting the core concept to local contexts and evolving scientific understanding.

Table 1: Historical Development of Selected Water Quality Indices

| Index (Developer, Year) | Number of Parameters | Key Parameters | Aggregation Method | Notable Features/Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horton (1965) [10] | 10 | DO, pH, Fecal Coliforms, Conductivity, etc. | Weighted Sum (Arithmetic) | First formal WQI; included "obvious pollution" as a parameter. |

| Brown et al. / NSF (1970/1973) [1] [10] | 9 | DO, FC, pH, BOD, Turbidity, Nitrate, etc. | Geometric Mean | Expert-derived weights; became a standard model globally. |

| Prati et al. (1971) [10] | 13 | pH, COD, DO, Ammonium, Chloride, etc. | Sum of Pollution Levels | Based on transformation of concentrations to pollution levels. |

| Dinius (1987) [1] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Multiplicative | Final score expressed as a percentage, with 100% indicating perfect quality. |

| CCME WQI (2001) [1] [10] | Flexible | User-defined based on guidelines | Non-linear | Developed for Canada; measures frequency of guideline excursions. |

| Malaysian WQI (MWQI) (2007) [1] | 6 | DO, BOD, COD, AN, SS, pH | Additive | Uses pre-established sub-index curves for parameter transformation. |

| West Java WQI (WJWQI) (2017) [1] | 9 (from 13) | Temp, SS, COD, DO, Nitrite, Phosphate, etc. | Multiplicative (like NSF) | Incorporated statistical screening to reduce parameter redundancy. |

The field continues to evolve, with recent research focusing on overcoming limitations such as parameter redundancy, eclipsing problems, and uncertainty in aggregation. Future perspectives include the development of more sophisticated indices that integrate statistical methods, account for ecological factors, and leverage technological advancements for better support of sustainable water resource management [2] [1] [10].

Methodological Framework and Core Protocols

The calculation of a robust Chemical Water Quality Index, suitable for river basin assessment, follows a structured multi-step process. Adherence to a detailed experimental protocol is essential for ensuring the reproducibility and scientific validity of the results.

The Four-Step WQI Calculation Process

The development and computation of any WQI universally involve four critical phases [1] [10]:

- Parameter Selection: Choosing a set of physical, chemical, and/or biological variables relevant to the water body and its intended use (e.g., drinking water, aquatic life).

- Transformation of Raw Data: Converting the measured concentration or value of each parameter into a dimensionless sub-index value, typically on a common scale (e.g., 0 to 100).

- Weight Assignment: Assigning a relative weight to each parameter that reflects its perceived importance for overall water quality.

- Aggregation of Sub-Indices: Mathematically combining the weighted sub-indices into a single, final index value.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for CWQI Application

The following workflow and detailed steps outline a standard methodology for applying a CWQI in a river basin assessment study.

Figure 2: Generalized Workflow for River Basin CWQI Assessment

Phase 1: Study Design and Site Selection

- Objective Definition: Clearly state the purpose of the assessment (e.g., spatial trend analysis, temporal monitoring, impact evaluation of a point source) [2] [12].

- Basin Characterization: Delineate the river basin and compile georeferenced data on land use, pollution sources (industrial, agricultural, urban), and hydrology [12].

- Monitoring Network Design: Select sampling stations that represent upstream (background) conditions, major pollutant inputs, and downstream gradients. For example, a study on the Arno River used stations to track quality deterioration downstream of urban centers like Florence [2].

Phase 2: Field Sampling and Parameter Measurement

- Sampling Frequency and Campaigns: Conduct sampling campaigns that capture seasonal variability (e.g., dry and rainy seasons) [12]. Consistency in timing and methods is critical for long-term trend analysis [2].

- Core Parameter Selection: Based on the literature, a robust CWQI for a river basin should include, but not be limited to, the following key chemical and physical parameters [2] [12] [1]:

- Dissolved Oxygen (DO): Critical for aquatic life.

- pH: Measures water acidity/alkalinity.

- Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD): Indicates organic pollution.

- Nutrients: Nitrates, Nitrites, Ammonia, Total Phosphorus.

- Major Ions: Chloride, Sulfate, Sodium.

- Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) / Conductivity: Measures salinity/inorganic content.

- Turbidity / Total Suspended Solids (TSS): Measures water clarity.

- Sample Collection and Analysis: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned containers, preserve them as required (e.g., cooling to 4°C), and analyze using standardized methods (e.g., DR 6000 spectrophotometer for ions, volumetric methods for alkalinity) [12] [7].

Phase 3: Data Quality Control and Transformation

- Data Validation: Perform statistical analysis (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk test for normality) and check for outliers [12].

- Sub-index Calculation: Transform each parameter's raw data into a sub-index value (e.g., 0-100 scale) using established rating curves or functions. For instance, the NSF WQI and others provide predefined curves for this purpose [1] [13].

Phase 4: Index Calculation and Aggregation

- Weight Assignment: Assign weights to each parameter based on expert opinion, statistical analysis (like Principal Component Analysis), or literature values to reflect their relative importance [12] [1]. For example, parameters with greater health or ecological impacts receive higher weights.

- Final Aggregation: Use a mathematical aggregation function to compute the final CWQI value. Common methods include:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for CWQI Studies

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-parameter Probe | HANNA HI 9829 [7] | Simultaneous in-situ measurement of pH, temperature, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), conductivity, TDS. |

| Spectrophotometer | HACH DR 6000 [7] | Laboratory analysis of specific ion concentrations (e.g., Iron, Sulphates, Chloride) in water samples. |

| Turbidity Meter | HANNA HI 98703 [7] | Quantitative measurement of water clarity/turbidity, a key physical parameter. |

| Sample Containers | Polyethylene bottles (500 mL) [7] | Collection and transportation of water samples, pre-washed to prevent contamination. |

| Titration Apparatus | Burettes, indicators [7] | Volumetric analysis for parameters like alkalinity and hardness. |

| Statistical Software | R, SPSS, PAST | Performing multivariate statistics (PCA, CA), trend analysis, and index calculation [12]. |

Contemporary Applications and Advanced Analysis

The application of CWQI in modern research extends beyond simple classification, serving as a powerful tool for diagnosing pollution sources and informing management policies.

Case Study: Diagnosing Trends in the Arno River Basin

A recent study (2025) applied a CWQI to the Arno River in Italy, utilizing historical geochemical data from 1988 to 2017. The study demonstrated the index's utility for:

- Tracking Spatial Evolution: The CWQI successfully identified a clear deterioration in water quality downstream of the major urban center of Florence, pinpointing a significant contamination hotspot [2].

- Attributing Pollution Sources: The decline in index value was primarily driven by elevated levels of chloride, sodium, and sulphate, linking the degradation to urban, industrial, and agricultural discharges [2].

- Evaluating Policy Effectiveness: Despite increasing anthropogenic pressures over three decades, the CWQI revealed that water chemistry remained relatively stable, suggesting that environmental regulations helped prevent further degradation [2].

Integration with Multivariate Statistical Techniques

To enhance the diagnostic power of a CWQI, researchers often integrate it with multivariate statistical methods [12].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): This technique helps reduce data dimensionality and identify the parameters that contribute most to water quality variation. For example, a study of the Piabanha River in Brazil used PCA to confirm that sewage discharge was the primary pollution source, as parameters like ammonia and total phosphorus loaded strongly on the main components [12].

- Cluster Analysis (CA): CA groups monitoring stations with similar water quality characteristics. This can optimize a monitoring network by reducing redundant stations and identifying zones of similar impairment, allowing for more targeted management actions [12].

The journey of Water Quality Indices from Horton's foundational model to today's specialized Chemical Water Quality Indices underscores their enduring value as a synthesis and communication tool in water resources management. For researchers engaged in river basin assessment, the CWQI provides a methodologically sound framework for transforming complex chemical data into actionable intelligence. The protocol's robustness is further enhanced when coupled with geospatial analysis and multivariate statistics, enabling a comprehensive diagnosis of pollution sources and trends. Future developments in this field will likely focus on integrating biological indicators, leveraging high-resolution sensor data, and refining aggregation techniques to reduce uncertainty. As pressures from global change intensify, the CWQI will remain an indispensable component of the scientist's toolkit, providing critical evidence to support the sustainable management of vital river basin resources.

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) is an essential tool in water resource management, transforming complex hydrological data into a single, comprehensible value that describes the quality of a water body. For researchers and scientists engaged in river basin assessment, the CWQI provides a standardized methodological framework for tracking geochemical evolution, identifying contamination hotspots, and evaluating long-term trends in relation to environmental policies and anthropogenic pressures [2]. The development and application of a robust CWQI rely on three fundamental pillars: the careful selection of parameters, the objective assignment of weights, and the mathematical aggregation of these components into a final index value. This guide examines these core components in detail, providing a technical foundation for their implementation in research contexts.

Parameter Selection

The first and most critical step in constructing a reliable CWQI is the selection of appropriate water quality parameters. This process involves identifying which physical, chemical, and biological characteristics best represent the overall water quality and the specific pressures on the river basin being studied.

Historical and Contemporary Parameter Choices

The practice of selecting parameters for water quality indices dates back to Horton's pioneering work in 1965, which established a framework using ten variables, including dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, coliforms, and electroconductivity (EC) [1]. This established the principle that parameter selection should reflect both the core physicochemical properties of water and key contaminants. Over time, the selection has evolved to address region-specific concerns and pollution sources.

Modern indices typically incorporate parameters that detect influences from major anthropogenic activities such as urbanization, industrial discharge, and agricultural runoff. For instance, a recent study on the Arno River Basin in Italy tracked parameters like chloride, sodium, and sulphate to pinpoint contamination from urban, industrial, and agricultural sources [2]. Similarly, a CWQI applied to a thermal power plant in Côte d'Ivoire included parameters like iron, sulphates, chloride, and silica to assess scaling and corrosion potential in industrial equipment [7].

Statistical and Expert-Driven Selection Methods

Parameter selection is often refined through a combination of statistical analysis and expert judgment to avoid redundancy and enhance the index's efficiency. The development of the West Java Water Quality Index (WJWQI) exemplifies this approach; it began with thirteen crucial water quality variables but used statistical assessment to eliminate redundant parameters, ultimately retaining nine: temperature, suspended solids, COD, DO, nitrite, total phosphate, detergent, phenol, and chloride [1].

Table 1: Common Water Quality Parameters and Their Environmental Significance

| Parameter | Environmental Significance | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Indicator of aquatic ecosystem health | Atmospheric diffusion, photosynthesis |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Measures organic pollution | Municipal wastewater, agricultural runoff |

| pH | Affects chemical and biological processes | Industrial discharge, natural geology |

| Total Phosphates/Nitrates | Indicators of eutrophication | Fertilizers, detergents, sewage |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Pb, Hg) | Toxicity to life forms | Industrial effluents, mining |

| Total Coliforms/Fecal Coliforms | Indicator of pathogenic contamination | Sewage, wildlife, livestock |

| Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | Measures inorganic salinity | Agricultural runoff, industrial waste |

| Turbidity/Suspended Solids | Measures water clarity | Soil erosion, urban runoff |

Weight Assignment

After parameter selection, the next step is to assign a weight to each parameter, signifying its relative importance in the overall index calculation. Weights ensure that parameters with greater significance to water quality or human health have a proportionally larger impact on the final index score.

Methodologies for Determining Weights

The assignment of weights has evolved from simple expert opinion to more sophisticated, statistically-grounded methods that minimize subjectivity.

- Expert Opinion Panels: Early indices like the National Sanitation Foundation WQI (NSFWQI) relied heavily on the judgments of expert panels to assign relative weights [1]. While this method incorporates valuable practical experience, it can introduce subjectivity.

- Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): To reduce this subjectivity, modern approaches often employ multi-criteria decision analysis tools like Saaty's Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [14]. The AHP provides a structured framework for comparing parameters against each other in a pairwise fashion, leading to a set of weights that minimizes personal bias. A study developing a Composite Water Quality Index (CWQI) for Indian conditions used AHP to compute weights for 25 selected parameters, ensuring a more objective and defensible weighting system [14].

- Statistical Analysis: Some methodologies use statistical measures, such as the sensitivity of a parameter's response to pollution or its frequency of violation against standards, to inform weight assignment.

The underlying principle is that parameters with more severe health implications or greater influence on ecosystem integrity should receive higher weights. For example, toxic substances or pathogens are typically weighted more heavily than aesthetic parameters.

Table 2: Example Weight Assignments from Different WQI Models

| Parameter | NSFWQI (Historical Example) | Malaysian WQI (MWQI) | Composite WQI (Indian Study) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | High | High | High (calculated via AHP) |

| Fecal Coliforms | High | - | - |

| pH | Medium | Included | - |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | High | Included | - |

| Total Nitrate/Phosphate | Medium | Included (as Ammonia Nitrogen) | - |

| Total Suspended Solids | - | Included | - |

| Heavy Metals | - | - | Included (Weighted via AHP) |

| Methodology Basis | Panel Opinion | Panel Opinion | Saaty's AHP [14] |

Aggregation Functions

The final technical stage is aggregation, where the normalized sub-index values of each parameter are mathematically combined with their weights to produce a single score. The choice of aggregation function is crucial as it determines the index's sensitivity to different types of water quality issues.

Common Types of Aggregation Functions

Several mathematical approaches exist, each with distinct advantages and drawbacks.

- Additive (Arithmetic Mean) Aggregation: This is one of the simplest forms, where the final index is a weighted sum of the sub-indices. The Malaysian WQI (MWQI) uses this approach, making it straightforward to calculate [1]. However, it can suffer from eclipsing, where a very poor value in one parameter is masked by acceptable values in others.

- Multiplicative (Geometric Mean) Aggregation: Developed to address the limitations of additive models, geometric aggregation is more sensitive to parameters that exceed acceptable limits. The Brown et al. index and the NSFWQI eventually adopted a geometric mean, which is less compensatory than an arithmetic mean [1]. This means that a low score in any single parameter will have a more pronounced effect on the final index, making it better at identifying polluted waters.

- Logarithmic Aggregation: Some indices, like the one developed by Said et al. (2004) for Florida streams, use logarithmic aggregation. A key advantage is that it can sometimes eliminate the need for pre-defined sub-indices and standardization [1].

- Min/Max Operator Models: Other models, such as the Oregon WQI (OWQI), use different forms of aggregation that may involve harmonic means or other functions to balance sensitivity and compensation [15].

Impact of Aggregation Choice

The selection of an aggregation function directly influences how the index communicates risk. A geometric mean will more aggressively flag water with one critically bad parameter, even if others are normal, while an arithmetic mean might report a more "average" score for the same data. Therefore, the choice should align with the index's purpose—whether it is to ensure no critical parameter is overlooked or to represent overall average conditions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflow

Implementing a CWQI for river basin research requires a rigorous, systematic protocol. The following workflow outlines the key stages, from initial planning to the final interpretation of results.

CWQI Development Workflow

Detailed Methodological Steps

- Define Study Scope and Objectives: Clearly articulate the purpose of the assessment (e.g., general quality, fitness for irrigation, detection of industrial pollution). This determines the spatial and temporal scale of sampling [2] [15].

- Parameter Selection: Choose parameters based on the study's objectives, local pollution sources, regulatory standards (e.g., WHO, CPCB, EQS), and data availability. Employ statistical screening (e.g., as in the WJWQI) to eliminate redundancy [1] [15].

- Data Collection and Laboratory Analysis: Establish a sampling plan covering strategic locations (e.g., upstream, downstream of cities/industries) and multiple seasons. Collect samples following standardized protocols [15] [7]. Analyze parameters using approved methods:

- Data Normalization: Convert the raw data of each parameter (with different units) into a non-dimensional sub-index value, typically on a scale of 0–100. This is done using rating curves or transformation functions that reflect the parameter's conformity to water quality standards [1].

- Weight Assignment: Calculate the relative weight of each parameter using a chosen method like the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), engaging with domain experts to perform pairwise comparisons [14].

- Index Aggregation: Compute the final CWQI score using the selected aggregation function (e.g., weighted arithmetic or geometric mean). The result is a single number representing overall water quality.

- Validation and Interpretation: Classify the index score according to pre-defined categories (e.g., Excellent, Good, Poor, Polluted). Validate the results by correlating them with known pollution events or land-use patterns, as demonstrated in the Arno River study, which linked quality deterioration to urban and agricultural inputs downstream of Florence [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful CWQI development and application depend on both conceptual rigor and the use of precise analytical tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for CWQI Studies

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in CWQI Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Field Measurement Instruments | Multi-parameter probe (pH, EC, TDS, DO), Turbidity Meter | Enables accurate in-situ measurement of labile parameters, providing the foundational dataset [7]. |

| Laboratory Analytical Instruments | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (e.g., DR 6000 HACH) | Quantifies concentrations of key chemical species like nitrates, sulphates, chlorides, and heavy metals [7]. |

| Titrimetric Analysis Reagents | Reagents for Alkalinity and Hardness titration | Allows for the determination of carbonate system parameters and water hardness through volumetric analysis [7]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Arc GIS, Statistical Software (R, Python) | Supports spatial analysis of sampling sites, statistical screening of parameters, and calculation of the final index [15]. |

| Sample Containers and Preservation | Polyethylene Bottles, Coolers, Refrigerant Packs | Ensures sample integrity during transport and storage, preventing chemical or biological alteration before analysis [7]. |

The construction of a scientifically defensible Chemical Water Quality Index rests on the meticulous integration of its three core components: relevant parameter selection, objective weight assignment, and an appropriate aggregation function. The parameter suite must reflect the hydrological and anthropogenic context of the river basin. The weighting system, increasingly supported by structured methods like AHP, must accurately represent the relative importance of each parameter. Finally, the aggregation function must be chosen with a clear understanding of how it will synthesize complex, multi-parameter data into a single, meaningful value. As the field advances, future developments in CWQI will likely involve greater integration with biological indicators, the use of high-resolution datasets to capture seasonal variability, and more sophisticated methods to disentangle natural and anthropogenic drivers [2]. For researchers, mastering these core components is fundamental to generating reliable data that can effectively support sustainable river basin management and environmental policy.

The Role of CWQI in Sustainable River Basin Management and Policy Support

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) represents a methodological framework designed to provide a simple, flexible, and widely applicable approach for quantifying water quality in river basin systems [2] [16]. As a robust scientific tool, CWQI transforms complex hydrochemical data into a single numerical value that effectively communicates water quality status to researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders involved in river basin management. This index serves as a critical component in sustainable water resource management by tracking the evolution of water chemistry along river courses, assessing the contribution of different solutes to overall quality, detecting contamination hotspots, and exploring long-term trends in relation to environmental policies [2].

The development of water quality indices dates back to the 1960s when Horton first established a system for rating water quality through index numbers, offering a tool for water pollution abatement [1]. Since then, numerous WQI models have evolved globally, including the National Sanitation Foundation WQI (NSF-WQI), Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment WQI (CCME-WQI), British Columbia WQI (BCWQI), and other region-specific indices [11] [1] [15]. The CWQI builds upon this historical foundation while addressing contemporary challenges in river basin assessment under changing climatic conditions and increasing anthropogenic pressures [2].

Methodological Framework of CWQI

Fundamental Computational Structure

The CWQI methodology operates through a structured multi-phase process that converts raw chemical parameters into a comprehensive quality index. The computational framework involves four critical processes: (1) parameter selection, (2) transformation of raw data onto a common scale, (3) assignment of parameter weights, and (4) aggregation of sub-index values [11]. This systematic approach ensures that the resulting index value accurately reflects the composite water quality while maintaining scientific rigor and practical applicability.

The index typically generates a single value ranging from 0 to 100, which is categorized into quality classes such as excellent, good, fair, marginal, and poor to facilitate clear interpretation and communication [1] [15]. This classification enables direct comparison of water quality across different spatial and temporal scales, supporting informed decision-making in river basin management.

Parameter Selection and Weighting

The selection of appropriate chemical parameters forms the foundation of an effective CWQI implementation. Commonly incorporated parameters include chloride, sodium, sulphate, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), total phosphate, nitrate concentrations, turbidity, and solid content [2] [1]. The specific choice of parameters should align with the dominant anthropogenic pressures and natural geochemical characteristics of the target river basin.

Table 1: Essential Chemical Parameters for CWQI Development in River Basin Assessment

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Environmental Significance | Typical Weighting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Ions | Chloride, Sodium, Sulphate | Indicator of urban, industrial, and agricultural inputs [2] | Medium to High |

| Oxygen Balance | Dissolved Oxygen (DO), BOD, COD | Ecosystem health and organic pollution [1] [15] | High |

| Nutrients | Total Phosphate, Nitrate | Agricultural runoff and eutrophication potential [1] | Medium |

| Physical Properties | pH, Temperature, Turbidity | Baseline chemical conditions and erosion [1] [15] | Low to Medium |

| Toxic Substances | Heavy metals, Phenol | Industrial pollution and human health impacts [1] | Variable |

Parameter weighting reflects the relative importance of each variable concerning overall water quality. Established methods for weight assignment include statistical approaches (e.g., principal component analysis), expert opinion surveys, and regulatory guidelines based on environmental and health significance [11] [1]. The CWQI framework maintains flexibility in parameter selection and weighting to accommodate region-specific priorities and data availability.

Index Calculation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized computational workflow for CWQI determination:

CWQI Computational Workflow

Experimental Protocols for CWQI Implementation

Basin-Scale Sampling Design

Implementing CWQI for river basin assessment requires a strategic sampling protocol that captures spatial and temporal variations in water quality. The experimental design must consider the river network structure, key anthropogenic pressure points (urban centers, industrial zones, agricultural areas), and seasonal hydrological variations [2] [15]. A robust sampling strategy includes:

- Longitudinal profiling: Sampling sites distributed along the river course from headwaters to confluence points to track chemical evolution [2]

- Impact gradient: Positioning sites upstream, adjacent to, and downstream of significant pollution sources

- Seasonal frequency: Conducting sampling campaigns during both high-flow and low-flow periods to account for dilution effects and concentration patterns [15]

- Basin representation: Ensuring coverage of major sub-basins and tributaries to identify regional contributions to water quality issues

The application of CWQI in the Arno River Basin (Tuscany, Italy) exemplifies this approach, using published geochemical data from four distinct periods (1988-1989, 1996-1997, 2002-2003, and 2017) to assess long-term trends [2] [16]. This temporal scope enabled researchers to evaluate water quality stability over three decades despite increasing anthropogenic pressures.

Analytical Methods and Quality Assurance

Laboratory analysis for CWQI parameters must follow standardized protocols to ensure data comparability and reliability. The table below outlines essential analytical methods and quality control measures:

Table 2: Standard Analytical Methods for Core CWQI Parameters

| Parameter | Standard Method | Detection Limits | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Ions (Cl⁻, Na⁺, SO₄²⁻) | Ion Chromatography (EPA Method 300) | 0.1 mg/L | Calibration verification, continuing calibration checks, duplicate analysis |

| Dissolved Oxygen | Electrochemical probe (ASTM D888) | 0.1 mg/L | Air calibration, salinity compensation, precision checks with Winkler method |

| BOD₅ | 5-Day incubation (EPA 405.1) | 0.5 mg/L | Glucose-glutamic acid check, seed control, dilution water blanks |

| Nutrients (NO₃⁻, PO₄³⁻) | Colorimetric (EPA 353.2, 365.3) | 0.01 mg/L | Calibration standards, spike recovery, method blanks |

| pH | Electrometric (EPA 150.1) | 0.1 pH units | Multi-point buffer calibration, temperature compensation |

| Turbidity | Nephelometry (EPA 180.1) | 0.1 NTU | Formazin primary standards, geometric mean calculation for flow-weighted composites |

Quality assurance protocols should include field blanks, duplicate samples, certified reference materials, and laboratory control samples to maintain data integrity throughout the CWQI assessment process [15]. The use of standardized methods ensures that CWQI values remain comparable across different monitoring campaigns and between river basins.

Research Reagents and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of CWQI requires specific research-grade reagents and materials to ensure analytical accuracy and reproducibility. The following table details essential solutions and their functions in the analytical processes:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CWQI Parameter Analysis

| Reagent Solution | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Chromatography Eluent | Carbonate/Bicarbonate buffer (1.8mM Na₂CO₃/1.7mM NaHCO₃) | Separation of major anions | Isocratic separation of F⁻, Cl⁻, NO₂⁻, Br⁻, NO₃⁻, PO₄³⁻, SO₄²⁻ [15] |

| BOD Dilution Water | Phosphate buffer, MgSO₄, CaCl₂, FeCl₃ | Nutrient-rich dilution medium | Provides optimal conditions for biochemical oxidation during BOD testing [1] |

| Nutrient Analysis Reagents | Cd reduction column, NEDD, sulfanilamide | Nitrate color development | Forms pink-colored diazo compound measurable at 540nm [15] |

| DO Fixing Reagents | MnSO₄, alkaline iodide-azide | Oxygen fixation in Winkler method | Forms Mn(OH)₂ precipitate that oxidizes to Mn(OH)₃ in presence of oxygen [1] |

| Preservation Reagents | H₂SO₄ (for COD), HNO₃ (metals) | Sample stabilization | Maintains original analyte concentrations until analysis [15] |

| Calibration Standards | NIST-traceable multi-element | Instrument calibration | Establishes quantitative relationship between response and concentration [15] |

Case Study: CWQI Application in the Arno River Basin

The implementation of CWQI in the Arno River Basin, one of the largest and most impacted catchments in central Italy, demonstrates the practical utility of this methodology in sustainable river basin management [2] [16]. The study applied CWQI to assess water quality using historical geochemical data spanning three decades, revealing distinct spatial patterns of chemical evolution along the river course.

Results indicated good to fair water quality in upstream reaches, with clear deterioration downstream of the Florence urban area, primarily linked to chloride, sodium, and sulphate inputs from urban, industrial, and agricultural activities [2]. Despite increasing anthropogenic pressures over the study period, water chemistry remained relatively stable, suggesting that regulatory measures implemented in the region helped prevent further degradation [2] [16]. This finding highlights the value of CWQI in evaluating the effectiveness of environmental policies and management interventions.

The Arno River case study further illustrates how CWQI serves as an operational tool for detecting contamination hotspots, tracking water chemistry evolution, and assessing the contribution of different solutes to overall water quality [2]. The identification of specific pollutant sources and pathways enables targeted management responses, optimizing resource allocation for pollution control measures within the river basin.

Integration with River Basin Management Policies

Policy Support and Regulatory Frameworks

CWQI provides critical scientific support for implementing and evaluating river basin management policies, particularly within regulatory frameworks like the European Union's Water Framework Directive (WFD) [17]. The WFD represents comprehensive legislation requiring member states to achieve "good status" for all water bodies, supported by monitoring requirements and River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) [17]. The CWQI methodology aligns perfectly with these requirements by offering a standardized approach to assess water quality trends and identify priority intervention areas.

The index's ability to simplify complex chemical data into communicable values facilitates evidence-based decision-making across administrative boundaries, a essential requirement in transboundary river basin management [18]. More than 260 transboundary river basins span approximately 45.3% of the Earth's land surface (excluding Antarctica) and support over 40% of the global population [18], highlighting the critical importance of standardized assessment tools like CWQI for cooperative management.

Monitoring and Assessment Cycles

Effective river basin management depends on continuous monitoring and periodic assessment, processes significantly enhanced through CWQI implementation. The index supports the cyclical nature of river basin planning through:

- Baseline assessment: Establishing initial water quality status against which future changes can be measured

- Trend analysis: Tracking water quality evolution in response to management interventions and external pressures

- Programme of measures evaluation: Assessing the effectiveness of specific management actions

- Reporting compliance: Generating simplified communication tools for regulatory reporting requirements

The experience from China's seven major river basins demonstrates how long-term water quality indexing can reveal improvement trends resulting from coordinated policy interventions [19]. Between 2001 and 2020, the overall water quality in China's seven major river basins exhibited gradual improvement, with different basins demonstrating varied growth values for Grade I-III water and reduction values for Grade IV-V and inferior Grade V water [19]. This large-scale application underscores the value of standardized water quality assessment for tracking national progress against environmental targets.

Future Perspectives and Methodological Refinements

While CWQI represents a significant advancement in water quality assessment methodology, several areas warrant further development to enhance its application in sustainable river basin management. Future refinements should focus on:

- Integration with biological indicators: Combining chemical and biological assessment frameworks to provide a more comprehensive ecological status evaluation [2]

- High-resolution temporal sampling: Capturing seasonal variability and episodic pollution events through more frequent monitoring [2]

- Source apportionment techniques: Enhancing the ability to separate natural geochemical background from anthropogenic contributions [2]

- Climate change incorporation: Developing adjustment factors to account for changing hydrological regimes and temperature effects on chemical processes

- Real-time monitoring integration: Adapting the CWQI framework to incorporate data from continuous sensor networks for rapid response management

The continuing evolution of CWQI methodologies will further strengthen their application in addressing the complex challenges of sustainable river basin management under global change conditions, ultimately contributing to the achievement of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals related to clean water and ecosystem conservation [3].

CWQI in Action: A Step-by-Step Methodology and Real-World River Basin Case Studies

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) is a powerful tool used by hydrologists, environmental scientists, and resource managers to transform complex water quality data into a single, comprehensible value [1]. This quantification is essential for assessing the health of river basins, tracking changes over time, and supporting evidence-based decision-making for environmental protection [20]. By integrating multiple physico-chemical parameters, the CWQI provides a standardized methodology for evaluating water quality, which is a critical component of any research focused on basin-scale assessment and management. This guide details the step-by-step process for calculating a robust CWQI.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

The development of water quality indices dates back to the 1960s, with Horton's work forming the foundation for modern indices like the CWQI [1]. The core principle involves aggregating measurements of various water quality parameters into a single, unitless number that reflects the overall water quality status.

It is important to distinguish the Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) from the Comprehensive Water Quality Index, which is sometimes abbreviated the same way. The former focuses on physico-chemical parameters, while the latter may also include biological and microbiological indicators [21] [22]. This guide focuses on the chemical index.

Step-by-Step Calculation Methodology

Step 1: Parameter Selection and Data Collection

The first step involves selecting a suite of key physico-chemical parameters relevant to the river basin being studied. Common parameters and their standard values are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Common Water Quality Parameters and Standards for CWQI Calculation

| Parameter | Common Standard Value (C₀) | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.5 - 8.5 [23] | - | A range, not a single value. |

| Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | 1000 [23] | mg/L | |

| Nitrates (NO₃⁻) | 50 [23] | mg/L | |

| Fluorides (F⁻) | 1.5 [23] | mg/L | |

| Total Hardness (as CaCO₃) | 500 [23] | mg/L | |

| Arsenic (As) | 0.01 [23] | mg/L | |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Varies | mg/L | Higher values typically indicate better quality. |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Varies | mg/L | Lower values typically indicate better quality. |

| Total Phosphorus (TP) | 0.2 [22] | mg/L | |

| Ammonia Nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N) | 0.6-1.5 [22] | mg/L |

Step 2: Calculation of the Individual Parameter Rating (Qₙ)

For each parameter, a quality rating (Qₙ) is calculated. This rating normalizes the measured value against its standard, converting all parameters to a common scale.

The general formula is:

Qₙ = [ (Vₙ - Vᵢ) / (Sₙ - Vᵢ) ] × 100

Where:

- Vₙ is the measured value of the nth parameter.

- Sₙ is the standard value (C₀) for the nth parameter.

- Vᵢ is the ideal value for the nth parameter.

The determination of Sₙ and Vᵢ depends on the nature of the parameter:

- For parameters with a maximum permissible limit only (e.g., TDS, Nitrates): Vᵢ is typically 0. Therefore, the formula simplifies to Qₙ = (Vₙ / Sₙ) × 100 [21] [22].

- For parameters with a permissible range (e.g., pH): Vᵢ is the ideal value within the range (e.g., 7.45, often determined graphically based on temperature for neutral water). If Vₙ < Vᵢ, then Sₙ is the minimum allowable value. If Vₙ ≥ Vᵢ, then Sₙ is the maximum allowable value [21].

Step 3: Determination of the Relative Weight (Wₙ)

Each parameter is assigned a unit weight (Wₙ) to reflect its relative importance in the overall water quality assessment. Parameters with greater potential impact on health or the environment are given higher weights.

The unit weight is inversely proportional to the standard value and is calculated as follows:

Wₙ = K / Sₙ

Where:

- Sₙ is the standard value (C₀) for the nth parameter.

- K is a proportionality constant, calculated to make the sum of the weights equal to 1: K = 1 / ( Σ 1/Sₙ ) [21].

Table 2: Example of Relative Weight (Wₙ) Calculation for Selected Parameters

| Parameter | Standard Value (Sₙ) | 1 / Sₙ | Unit Weight (Wₙ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | 0.01 | 100.000 | 0.40 |

| Nitrates (NO₃⁻) | 50 | 0.020 | 0.00008 |

| TDS | 1000 | 0.001 | 0.000004 |

| Sum (Σ 1/Sₙ) | 100.021 | ||

| K = 1 / 100.021 | ≈ 0.01 |

Step 4: Aggregation into the Final CWQI Score

The final CWQI value is calculated by taking the weighted sum of all individual quality ratings.

CWQI = Σ (Qₙ × Wₙ) / Σ Wₙ

Since Σ Wₙ is designed to be 1, the formula can be simplified to:

CWQI = Σ (Qₙ × Wₙ) [21]

A lower CWQI value indicates better water quality. The calculated index value can then be interpreted using a classification scale.

Table 3: CWQI Score Interpretation and Water Quality Classification

| CWQI Value | Classification | Water Quality Status |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 50 | B | Excellent |

| 50 - 100 | C | Good |

| 100 - 200 | D | Low Quality Water |

| 200 - 300 | E | Very Low Quality Water |

| 300 - 500 | F | Water Unsuitable for Drinking |

| > 500 | G | Water Very Unsuitable for Drinking [21] |

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

For more complex research applications, the CWQI can be integrated with statistical and computational models. For instance, the Monte Carlo simulation can be used to predict CWQI values with high confidence based on limited water quality monitoring samples, accounting for uncertainty in the input data [22]. Furthermore, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Multi Linear Regression (MLR) models have been successfully applied to predict CWQI, providing a reliable and cost-effective alternative to direct calculation, especially for large datasets [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete CWQI calculation process, from data collection to final classification.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful CWQI assessment relies on precise laboratory analysis. The following table details key reagents and materials required for measuring common parameters.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Water Quality Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Parameter of Interest | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nessler's Reagent | Ammonia Nitrogen (NH₄⁺-N) | Used in spectrophotometric methods to determine ammonia concentration via colorimetric reaction [22]. |

| Alkaline Potassium Persulfate | Total Nitrogen (TN) | Acts as an oxidizing agent in the digestion step to convert various nitrogen forms to nitrate for measurement [22]. |

| Ammonium Molybdate | Total Phosphorus (TP) | Forms a phosphomolybdate complex in spectrophotometric methods, which is then reduced to a blue compound for measurement [22]. |

| Potassium Hexachloroplatinate(IV) / Cobalt(II) Chloride | APHA Color (Hazen Scale) | Used to create standard solutions for the visual or instrumental measurement of water color [24]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges (e.g., LC-C18) | PAHs, n-Alkanes | Used to concentrate and clean up trace organic pollutants from large water samples before instrumental analysis [22]. |

| Sulfuric Acid (for acidification) | Sample Preservation | Added to samples immediately after collection to lower pH and prevent microbial degradation of target analytes before analysis [22]. |

The Chemical Water Quality Index is an indispensable tool for the holistic assessment of river basins. This guide has provided a detailed, step-by-step framework for its calculation, from the critical initial stage of parameter selection and data collection to the final aggregation and interpretation of the score. By adhering to this standardized methodology and leveraging advanced modeling techniques where appropriate, researchers and water resource managers can generate reliable, comparable, and actionable data. This information is fundamental for tracking environmental health, evaluating the impact of anthropogenic pressures, and informing policies for the sustainable management of vital water resources.

The Chemical Water Quality Index (CWQI) represents a significant methodological advancement in environmental science, addressing persistent flaws in traditional water quality assessment frameworks. This technical guide examines the core principles, computational methodologies, and applications of CWQI as a standardized approach for evaluating water quality in river basin assessment research. By integrating multiple physicochemical parameters into a single quantitative value, CWQI enables researchers to track spatial and temporal variations in water chemistry, identify contamination hotspots, and assess the contribution of individual pollutants to overall water quality degradation. The framework's flexibility allows adaptation across diverse hydrological contexts while maintaining scientific rigor, offering researchers and environmental professionals an operational tool for supporting evidence-based decision-making in water resource management.

Water quality assessment has evolved significantly since Horton's pioneering index development in 1965, which introduced a systematic approach using ten water quality parameters [1]. Subsequent refinements by Brown et al. (1970) established a nine-parameter model using arithmetic weighting, while the National Sanitation Foundation further advanced the field through geometric aggregation functions that increased sensitivity to parameters exceeding normative values [1]. The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) enhanced methodological rigor through their 2001 index, which evaluated water quality through scope, frequency, and amplitude [25].

Traditional water quality indices face several methodological limitations that the CWQI framework specifically addresses:

- Subjective parameter weighting reliant on expert opinion rather than statistical significance

- Inconsistent aggregation functions that either overemphasize or mask critical parameter outliers

- Limited spatial and temporal comparability due to region-specific customization

- Inadequate handling of missing parameters within multivariate assessment frameworks

- Poor discrimination sensitivity across the quality spectrum, particularly in moderately impaired systems

The CWQI framework emerged to overcome these limitations through standardized methodological protocols that maintain contextual flexibility while ensuring scientific objectivity in water quality benchmarking and trend analysis [2] [1].

Core Principles of the CWQI Methodology

Theoretical Foundation

The CWQI operates on the fundamental principle that multiple physicochemical parameters can be systematically integrated into a single numerical value that accurately reflects overall water quality status. This value ranges typically from 0 to 100, where higher values indicate superior water quality [1]. The index transforms complex multidimensional data into an accessible format for both technical decision-making and stakeholder communication, serving as a reliable tool for quantifying water chemistry evolution under escalating anthropogenic pressures and global change scenarios [2].

Unlike simplistic averaging methods, the CWQI incorporates weighted aggregation that accounts for the differential environmental significance of various parameters and their potential synergistic effects. The framework maintains hydrological relevance by preserving sensitivity to critical parameters that may indicate specific contamination sources or ecosystem stressors, enabling targeted management interventions [2] [26].

Methodological Workflow

The CWQI development process comprises five systematic phases that ensure methodological rigor and reproducible results:

- Parameter Selection: Identification of physiochemically significant variables relevant to the specific aquatic system and assessment objectives

- Threshold Definition: Establishment of quality benchmarks based on regulatory standards or ecological requirements

- Data Normalization: Transformation of heterogeneous parameter measurements onto a consistent dimensionless scale

- Parameter Weighting: Assignment of relative importance factors based on environmental impact and health significance

- Index Aggregation: Mathematical integration of normalized, weighted parameters into a composite quality score [7]

This structured approach eliminates arbitrary decision-making while maintaining adaptability to diverse hydrological contexts, from temperate river systems to industrial water supplies [2] [7].

Computational Architecture of CWQI

Parameter Selection and Standardization

The initial phase of CWQI implementation involves curating a parameter set that comprehensively captures relevant water quality dimensions. Research demonstrates that effective CWQI models typically incorporate between 9-13 critical parameters, with studies on the Yeşilırmak River (Turkey) utilizing 15 parameters including pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia, ammonium, nitrite, nitrate, phosphate, iron, copper, zinc, potassium, sulfate, sulfite, and chlorine [26].

Parameter selection follows a systematic screening process to eliminate redundancy while maintaining assessment comprehensiveness. The West Java Water Quality Index (WJWQI) development exemplifies this approach, applying statistical assessment to reduce an initial 13 parameters to 9 critical variables: temperature, suspended solids, COD, DO, nitrite, total phosphate, detergent, phenol, and chloride [1].

Table 1: Essential Water Quality Parameters for CWQI Development

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Environmental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Regime | Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | Indicator of organic pollution and aquatic ecosystem health |

| Nutrients | Ammonia, Nitrate, Nitrite, Total Phosphate | Eutrophication potential and agricultural runoff impact |

| Physical Properties | pH, Temperature, Turbidity, Total Dissolved Solids | Baseline habitat suitability and aesthetic quality |

| Major Ions | Chloride, Sulfate, Potassium | Geochemical background and anthropogenic contamination |

| Trace Metals | Iron, Copper, Zinc, Manganese | Industrial discharge and corrosion potential |

Weighting and Aggregation Functions

Parameter weighting establishes relative importance within the index structure, with weights typically derived through statistical analysis (e.g., principal component analysis) or expert elicitation protocols. Research on the Yeşilırmak River demonstrated that hierarchical cluster analysis effectively identifies parameters with the greatest influence on final index scores, with ammonia, phosphate, COD, sulfide, iron, ammonium, nitrite, and DO exhibiting predominant effects [26].

Aggregation functions mathematically combine standardized parameters into the composite index value. The CWQI typically employs modified geometric aggregation that enhances sensitivity to severely impaired parameters, overcoming the masking effect prevalent in arithmetic means. This approach ensures that a single critically impaired parameter appropriately influences the overall score, reflecting its potential ecological impact [1].

The fundamental CWQI aggregation formula follows this structure:

CWQI = [Σ(wi × si)^p]^(1/p)

Where:

- w_i = weight assigned to parameter i

- s_i = subindex score for parameter i

- p = sensitivity parameter (typically 1-2)

Table 2: Comparison of Aggregation Techniques in Water Quality Indices

| Aggregation Method | Mathematical Formula | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic Mean | CWQI = Σ(wi × si) | Simple computation, intuitive interpretation | Masking effect: poor sensitivity to severely impaired parameters |

| Geometric Mean | CWQI = Π(si)^(wi) | Penalizes individual low values, no eclipsing | Over-penalizes isolated poor parameters |

| Root Mean Square | CWQI = √[Σ(wi × si²)] | Emphasizes extreme values | Can overemphasize measurement outliers |

| Harmonic Mean | CWQI = n / [Σ(wi / si)] | Strong sensitivity to low values | Excessive influence from single poor parameters |

Quality Classification Framework

CWQI values are typically classified into qualitative water quality categories to facilitate interpretation and management response. While specific thresholds may vary by jurisdiction, a representative classification scheme demonstrates the index's discriminatory power:

- Excellent (90-100): Water quality protected with minimal impairment; virtually undisturbed conditions

- Good (70-89): Water quality protected with only minor degradation; slightly impaired conditions

- Fair (50-69): Water quality usually protected but occasionally threatened; moderate impairment

- Marginal (25-49): Water quality frequently threatened; consistently impaired conditions

- Poor (0-24): Water quality almost always threatened; severely impaired conditions [26]

Application of this classification to the Yeşilırmak River in Northern Turkey yielded CWQI scores ranging from 33-64, indicating "poor to marginal" water quality across the study area and triggering targeted management intervention [26].

Experimental Protocols for CWQI Implementation

Field Sampling and Analytical Methods

Proper CWQI determination requires rigorous sampling protocols and standardized analytical procedures. The methodology implemented at the Atinkou Thermal Power Plant (Côte d'Ivoire) exemplifies appropriate technical standards, with samples collected in pre-cleaned 500mL polyethylene bottles, preserved at 4°C, and protected from light during transport [7].