Coastal Aquifers in Crisis: Unraveling the Impact of Urbanization on Groundwater Chemistry Evolution

This article synthesizes global research on the evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas, a critical nexus of hydrogeological and anthropogenic processes.

Coastal Aquifers in Crisis: Unraveling the Impact of Urbanization on Groundwater Chemistry Evolution

Abstract

This article synthesizes global research on the evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas, a critical nexus of hydrogeological and anthropogenic processes. It explores the foundational natural and human-induced drivers altering aquifer geochemistry, from seawater intrusion to contaminant infiltration. The scope encompasses advanced methodological approaches for investigation, including isotopic dating and multivariate statistics, and addresses troubleshooting for pervasive challenges like nitrate pollution and salinization. Through comparative validation of management strategies across diverse geographical cases, from China to Argentina, this review provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and environmental professionals tasked with protecting vulnerable coastal groundwater resources, which are essential for drinking water, ecosystems, and sustainable development.

The Dual Forces Reshaping Coastal Groundwater: From Natural Geochemistry to Anthropogenic Pressures

Coastal hydrogeology is a critical sub-discipline of hydrology focused on the movement and chemical properties of groundwater in coastal areas, specifically studying the interaction between fresh groundwater and seawater [1]. These systems are dynamic and sensitive to both natural processes and anthropogenic pressures. In the context of increasing urbanization and climate change, understanding the evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas has become a paramount research focus [2] [3]. This guide provides a technical overview of the fundamental components of coastal hydrogeological systems, detailing the aquifer types, the dynamics of the freshwater-seawater interface, and the methodologies essential for their study, all framed within the scope of contemporary research challenges.

Core Components of a Coastal Hydrogeological System

Aquifer Types and Classifications

Coastal aquifers are classified based on their geological composition, which directly controls their hydraulic properties and susceptibility to contamination and seawater intrusion. The primary classifications are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Coastal Aquifers

| Aquifer Type | Geological Description | Hydraulic Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Sedimentary Aquifers [1] | Consist of coarse-grained and fine-grained sediments (e.g., sand, silt, clay). | Permeability is highly variable and typically decreases towards the seaside. |

| Hard Rock Aquifers [1] | Composed of igneous or metamorphic rock with networks of joints and fractures. | Groundwater flow is controlled by the orientation and connectivity of fractures; generally low porosity. |

| Limestone Aquifers [1] | Formed from carbonate minerals. Can develop into extensive karst systems. | Can have very high permeability and rapid flow where dissolution has occurred (karst). |

Furthermore, these geological formations can be configured as either unconfined aquifers (where the water table is open to the atmosphere through pore spaces) or confined aquifers (where groundwater is trapped under pressure between impermeable layers) [1]. The configuration significantly influences the system's vulnerability to surface contaminants and the mechanics of seawater intrusion.

The Freshwater-Seawater Interface (FSI)

The Freshwater-Seawater Interface (FSI) is the dynamic boundary where freshwater, originating from land-based precipitation, meets denser saltwater from the ocean [4]. This interface is not a sharp line but a transition zone of mixing characterized by a salinity gradient from freshwater (Total Dissolved Solids, TDS < 1000 mg/L) to saline water (TDS ≈ 35,000 mg/L) [1] [4].

The fundamental principle governing the static position of this interface is the Ghyben-Herzberg principle [1] [4]. This principle establishes a simple relationship between the elevation of the freshwater table above sea level and the depth of the interface below sea level, demonstrating that for every unit of freshwater above sea level, a column of freshwater approximately 40 units high extends below it, owing to the density contrast.

Table 2: Salinity Classification of Groundwater [1]

| Classification | Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) (mg L⁻¹) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 0 – 1,000 | Suitable for drinking; highly diluted chemistry. |

| Brackish | 1,000 – 10,000 | Too saline for drinking; result of mixing or evaporation. |

| Saline | 10,000 – 36,000 | Similar to seawater. |

| Brine | >100,000 | Result of extreme evaporation or salt dissolution. |

Dynamics and Perturbations of the Interface

The FSI is a dynamic equilibrium, sensitive to various natural and anthropogenic drivers.

- Anthropogenic Perturbations: Groundwater pumping is a primary cause of seawater intrusion. Excessive extraction lowers the freshwater hydraulic head, causing the saltwater wedge to move landward [4]. A 2025 study in Alabama demonstrated that a 50% increase in groundwater withdrawals caused seawater to advance ~320 meters inland, while a 50% reduction led to a ~270-meter retreat [5]. This process can be localized, such as pumping-induced saltwater up-coning beneath a well, or regional [1]. Urbanization also alters natural recharge patterns and introduces contaminants like nitrate, which can be a more immediate water quality concern than salinity in some urban coastal areas [3].

- Natural Perturbations: Tides cause cyclical oscillations of the interface and enhance mixing [1]. Storm surges, as studied during Tropical Storm Claudette (2021), can cause a substantial inland movement of the saltwater wedge, with effects persisting for nine months or more [5]. Climate change and sea-level rise pose a long-term threat by exerting sustained landward pressure on the interface [6] [4].

- Geochemical Processes: The FSI is an active hydro-biogeochemical reactor. Key processes include cation exchange (where marine Na⁺ and Mg²⁺ displace Ca²⁺ from sediment surfaces and vice-versa), calcite dissolution/precipitation, and redox reactions such as sulfate reduction and methanogenesis [7]. Episodic events like storm flooding can trigger pulses of seawater that rapidly alter these chemical equilibria, leading to long-term decalcification of the aquifer matrix [7].

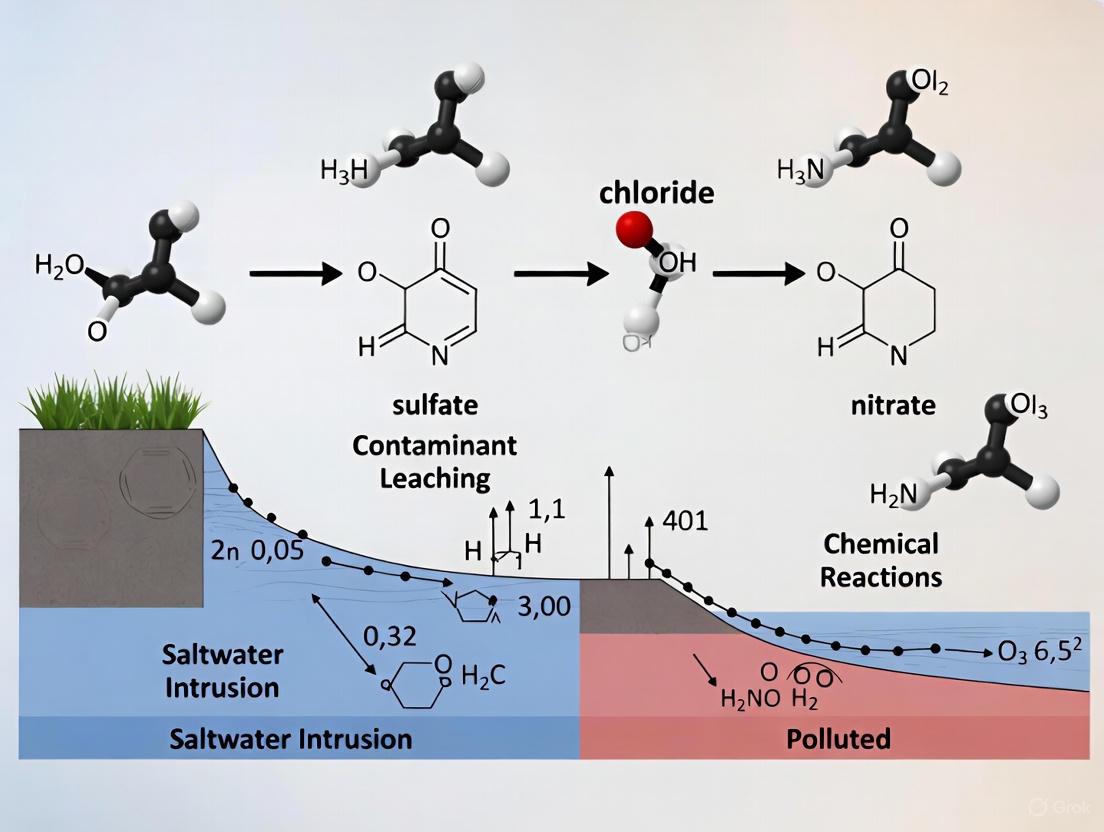

The diagram below illustrates the structure of a coastal hydrogeological system and the dynamic interactions between its components and external stressors.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Studying coastal hydrogeological systems requires a multi-faceted approach, combining field investigation, physical and numerical modeling, and emerging data-science techniques.

Field Investigation and Monitoring

A foundational step is the installation of a monitoring well network. As detailed in a study of a sandy aquifer in Denmark, this involves driving piezometers (e.g., polyethylene pipes with 12-cm screens) into the aquifer using a drilling rig (e.g., Geoprobe 54 DT) to allow for periodic sampling and hydraulic testing at multiple depths and locations [7]. Key monitored parameters and their analytical methods include:

- Major Ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻): Analyzed using ion chromatography to understand hydrochemical facies and mixing [3] [7].

- Nutrients and Organic Carbon: Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) is measured using instruments like a Shimadzu TOC analyser [3].

- Water Level and Salinity Dynamics: Multilevel wells instrumented with electrical conductivity and water pressure sensors provide continuous data on groundwater head and salinity variations, crucial for understanding tidal influences and intrusion events [6].

Numerical and Machine Learning Modeling

- Physics-Based Numerical Models: Tools like HydroGeoSphere (HGS) are used to simulate fully coupled surface-subsurface flow and solute transport with variable density [5]. These models are essential for predicting the response of the FSI to scenarios like pumping changes or storm surges. The protocol involves constructing a 3D model of the aquifer, calibrating it with field data, and running predictive simulations [5].

- Machine Learning (ML) Models: ML approaches are increasingly combined with physical models. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are effective for forecasting groundwater levels over decadal timescales under different pumping scenarios, using sequences of meteorological data as input [5]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) can be used for spatial prediction and to validate the results of physical models [5]. Model performance is typically evaluated using metrics like the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), where a value above 0.8 is considered acceptable [5].

Data Analysis Techniques

- Statistical Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) are powerful statistical tools to distinguish the impact of natural processes (e.g., seawater intrusion, water-rock interaction) from anthropogenic activities (e.g., industrial pollution, sewage intrusion) on groundwater chemistry [2].

- Risk Assessment: Non-cancer risk models calculate a Hazard Quotient (HQ) to evaluate age-specific health risks from contaminants like nitrate in drinking water, an important consideration in urbanized coastal areas [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Field and laboratory investigations in coastal hydrogeology rely on a suite of specialized tools and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Coastal Hydrogeology Studies

| Item / Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Piezometers / Monitoring Wells [7] | Allows for discrete groundwater sampling and water level measurement at specific depths. | Fundamental for characterizing vertical and horizontal hydrochemical gradients across the FSI. |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) Sensors [6] | Measures water's ability to conduct electricity, serving as a proxy for salinity (TDS). | Real-time, in-situ monitoring of salinity dynamics and intrusion events. |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) [3] | Separates and quantifies concentrations of major anions and cations in a water sample. | Determining the ionic composition of groundwater to identify water type and geochemical processes. |

| TOC Analyser [3] | Quantifies the concentration of Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC). | Assessing organic pollution and understanding biogeochemical cycling (e.g., organic matter mineralization). |

| Geophysical Surveys (e.g., ERT) [6] | Images the subsurface resistivity structure without direct drilling. Resistivity is inversely related to salinity. | Regional mapping of the saltwater intrusion plume and identifying subsurface structures. |

| Variable-Density Flow & Solute Transport Models (e.g., HGS) [5] | Simulates the movement of freshwater and saltwater and their mixing, accounting for density differences. | Predictive modeling of intrusion scenarios, testing mitigation strategies, and understanding system dynamics. |

The coastal hydrogeological system, defined by its aquifer types and the dynamic freshwater-seawater interface, is a complex and critically important environment. Its chemistry and structure are evolving under the dual pressures of natural change and intense human activity, particularly urbanization. A modern research approach requires an integrated methodology, combining traditional field hydrogeology, advanced numerical modeling, and emerging machine learning techniques. Understanding this system in its entirety—from the physical flow and geochemical reactions to the anthropogenic impacts—is essential for developing sustainable management strategies to protect vulnerable groundwater resources in coastal regions worldwide.

The chemical evolution of groundwater in coastal aquifers is a complex process governed by a suite of natural geochemical mechanisms. As highlighted in global studies, understanding these processes is critical for managing water resources in urbanized coastal areas, where anthropogenic pressures exacerbate natural vulnerabilities [6] [8]. The core natural evolutionary processes include water-rock interaction, which controls the acquisition of solutes; cation exchange, which alters the cationic composition; and paleo-water mixing, which reflects historical hydrological changes [9] [10]. Within the context of intensively developed coastal regions, these processes are often overprinted by pollution from seawater intrusion, domestic sewage, and agricultural practices, making it essential to disentangle the natural evolutionary footprint from anthropogenic contamination [8] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the methodologies and principles underlying the identification and quantification of these primary natural processes.

Core Process Definitions and Hydrochemical Signatures

This section details the fundamental definitions and characteristic hydrochemical indicators of each primary natural evolutionary process.

Water-Rock Interaction: This process encompasses the dissolution of primary silicate, carbonate, and sulfate minerals within the aquifer matrix, releasing major ions into the groundwater. Its signature is identified through ionic ratios and saturation indices. For instance, a (Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺) vs. HCO₃⁻ + SO₄²⁻ plot can reveal carbonate dissolution, while Na⁺/Cl⁻ ratios versus Cl⁻ can indicate silicate weathering if the ratio decreases with increasing Cl⁻ [9] [10]. Gibbs diagrams are a standard tool for delineating the dominance of rock weathering from other processes like evaporation or precipitation [10].

Cation Exchange: This is a reversible process where cations in solution exchange with those adsorbed on clay mineral surfaces in the aquifer. In coastal settings, seawater intrusion often triggers this process, leading to the adsorption of Ca²⁺ and release of Na⁺, resulting in Na-HCO₃ type water with characteristically low calcium concentrations [9]. The key diagnostic is the Chloro-Alkaline Index (CAI), where negative values indicate the exchange of Na⁺ and K⁺ in water with Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ on rocks [9].

Paleo-Water Mixing (or Hydrologic Mixing): This process involves the intermingling of distinct water masses, such as fresh shallow groundwater, deep thermal water, and seawater, each with a unique chemical and isotopic signature. In the Pocheon spa area, multivariate mixing and mass balance modeling (M3 modeling) successfully identified mixing between Ca-HCO₃ type shallow water, Na-HCO₃ type deep water, and surface water [9]. Stable isotopes of water (δ²H and δ¹⁸O) are powerful tracers for identifying and quantifying the contributions from different end-member water sources [10].

Table 1: Characteristic Signatures of Primary Natural Evolutionary Processes in Groundwater

| Process | Key Hydrochemical Signatures | Diagnostic Tools & Ratios |

|---|---|---|

| Water-Rock Interaction | - Increase in TDS, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, SiO₂- Specific ionic facies (e.g., HCO₃-Ca) | - Gibbs Diagrams- Ionic Ratios (e.g., Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺, Na⁺/Cl⁻)- Saturation Indices (e.g., for Calcite, Dolomite) |

| Cation Exchange | - Na⁺ enrichment and Ca²⁺ depletion- Evolution from Ca-HCO₃ to Na-HCO₃ water type- Modified hardness | - Chloro-Alkaline Index (CAI)- Scatter plots of (Na⁺ - Cl⁻) vs. (Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺ - HCO₃⁻ - SO₄²⁻) |

| Paleo-Water Mixing | - Non-conservative behavior of ions- Linear trends in ionic and isotopic plots- Presence of multiple, distinct water types | - Multivariate Mixing (M3) Modeling- Piper Diagrams- Stable Isotope Analysis (δ¹⁸O, δ²H) |

Quantitative Data and Analytical Methodologies

This section summarizes quantitative findings and outlines standardized experimental protocols for investigating groundwater evolutionary processes.

Summarized Quantitative Data from Field Studies

Field studies from various coastal aquifers provide quantitative evidence of the influence of these natural processes, often in conjunction with anthropogenic factors.

Table 2: Quantitative Source Apportionment of Groundwater Salinity in a Coastal Aquifer (Dongshan Island, China) [8]

| Pollution Source | Contribution in Dry Season (%) | Contribution in Wet Season (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Seawater Intrusion | 49.5 | 41.8 |

| Water-Rock Interaction | 23.0 | 28.8 |

| Domestic Sewage | 13.4 | 19.5 |

| Agricultural Practices | 11.6 | 8.0 |

| Industrial Wastewater | 2.5 | 1.9 |

Table 3: Isotopic Apportionment of Nitrate Sources in Coastal Groundwater (Quanzhou, China) [10]

| Nitrate Source | Average Contribution (%) |

|---|---|

| Sewage and Manure | 66.6 |

| Soil Nitrogen | 21.5 |

| Synthetic Fertilizer | 15.0 |

| Atmospheric Deposition | 2.5 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

A robust hydrogeochemical investigation relies on a systematic workflow from field sampling to advanced data modeling.

Protocol 1: Field Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

- Well Purging: Prior to sampling, purge the well for at least 10 minutes or until physiochemical parameters (pH, EC, T) stabilize to remove stagnant water [10].

- Field Measurements: Measure in-situ parameters like pH, temperature, electrical conductivity (EC), and redox potential (Eh) using a calibrated multi-parameter instrument [10].

- Sample Collection: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned polyethylene bottles. For cation and trace element analysis, acidify samples with high-purity HNO₃ to pH < 2. Filter samples through 0.45 μm membranes as required [10].

- Laboratory Analysis: Analyze major cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) via Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Analyze major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) using Ion Chromatography (IC). Determine HCO₃⁻ by acid-base titration [10].

Protocol 2: Stable Isotope Analysis of Water and Nitrate

- Water Stable Isotopes (δ²H, δ¹⁸O): Analyze water samples using a Stable Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) coupled with a suitable equilibration or pyrolysis system. Results are reported relative to VSMOW [10].

- Nitrate Stable Isotopes (δ¹⁵N, δ¹⁸O): Convert NO₃⁻ in the water sample to nitrous oxide (N₂O) via denitrifying bacteria or chemical reduction. Concentrate and purify the N₂O on a trace gas system, and determine the isotopic composition using an IRMS. Use international reference standards (e.g., USGS32, USGS34) for calibration [10].

Protocol 3: Multivariate Mixing and Mass Balance (M3) Modeling

- End-Member Definition: Use hydrochemical and isotopic data to identify potential end-member water masses (e.g., seawater, fresh rainwater, deep thermal water) [9].

- Factor Analysis: Perform Q-mode factor analysis on the dataset to identify the number of significant end-members contributing to the observed water chemistry [9].

- Mass Balance Calculation: Using a geochemical modeling code like PHREEQC, compute the proportional contribution of each end-member to a given water sample by solving a set of mass-balance equations for conservative tracers (e.g., Cl⁻, δ¹⁸O) [9].

- Net Mass Transfer: After establishing the mixing proportions, calculate the net mole transfer of minerals required to explain the non-conservative behavior of other solutes, accounting for water-rock interaction and cation exchange [9].

Process Visualization and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows for the key processes discussed.

Groundwater Chemical Evolution Pathway

Integrated Hydrogeochemical Investigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful hydrogeochemical study requires specific reagents, standards, and instrumentation.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Hydrogeochemical Studies

| Item Name | Specification / Purity | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Trace metal grade, >99.999% | Acidification of water samples for cation and trace element analysis to prevent adsorption onto container walls and preserve sample integrity. |

| Ion Chromatography Eluents | e.g., Carbonate/Bicarbonate solutions | Mobile phase for the separation and quantification of major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) in water samples. |

| International Isotopic Standards | VSMOW (for water isotopes), USGS32, USGS34 (for nitrate) | Calibration of stable isotope ratio mass spectrometers to ensure accurate and comparable measurement of δ¹⁸O, δ²H, δ¹⁵N, and δ¹⁸O-NO₃ values. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Certified groundwater or synthetic standard solutions | Validation of analytical accuracy for major ion and trace element concentrations during ICP-MS and IC analysis. |

| Cation Exchange Resins | e.g., Amberlite or Dowex resins | Used in laboratory experiments to simulate and study cation exchange processes occurring in natural aquifers. |

| Hydrochemical Modeling Software | PHREEQC, Geochemist's Workbench | Performing mass-balance modeling, calculation of mineral saturation indices, and simulation of reaction pathways. |

The rapid expansion of coastal urban areas represents one of the most significant anthropogenic forcings on groundwater systems globally. As populations concentrate in low-lying coastal zones, the resulting land use changes, industrial activities, and infrastructure development collectively alter the physical and geochemical conditions of underlying aquifers. This transformation is particularly critical in coastal regions, where groundwater systems exist in a delicate equilibrium with seawater, and urbanization pressures can disrupt this balance with lasting consequences. The evolution of groundwater chemistry in these urbanized coastal areas provides a critical indicator of environmental change, reflecting the complex interplay between human activities and hydrological systems. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing sustainable management strategies to protect water resources in densely populated coastal regions, where over half the world's population resides and depends heavily on groundwater for domestic, agricultural, and industrial purposes [11].

Key Drivers of Hydrochemical Evolution

Land Use Change and Urbanization Patterns

The conversion of natural landscapes to urban environments fundamentally alters groundwater recharge patterns and introduces novel contamination pathways. Research from Taejon, South Korea, demonstrates that groundwater chemistry is more influenced by land use and urbanization than by aquifer rock type [12]. This study revealed systematic variations in hydrochemical facies across an urbanization gradient: groundwater from green areas and new residential districts typically exhibited low electrical conductance and Ca-HCO3 type water, whereas samples from old downtown and industrial districts shifted toward Ca-Cl(NO3+SO4) types with high electrical conductance [12]. This transition reflects the progressive overlay of anthropogenic influences on natural hydrochemical backgrounds.

The stage of urbanization further modulates these impacts. In Shijiazhuang, China, researchers documented evolving contamination drivers across different urbanization phases. During the primary stage (1985-1995), carbonate and rock salt dissolution, cation exchange, and industrial activities dominated hydrochemical evolution. By the advanced urbanization stage (2006-2015), these drivers had shifted to carbonate and gypsum dissolution, groundwater over-exploitation, agricultural fertilization, and domestic sewage influences [13]. This temporal evolution underscores how the dominant mechanisms of groundwater quality degradation transform as urban areas develop and intensify.

Table 1: Evolution of Groundwater Chemistry Drivers Across Urbanization Stages in Shijiazhuang, China [13]

| Urbanization Stage | Time Period | Urbanization Rate | Dominant Hydrochemical Processes | Key Contaminants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Stage | 1985-1995 | <30.0% | Carbonate and rock salt dissolution, cation exchange, industrial activities | Initial nitrate increase (13.7 mg/L) |

| Intermediate Stage | 1996-2005 | 30.1%-50.0% | Transition period with mixed influences | Rising nitrate concentrations |

| Advanced Stage | 2006-2015 | 50.1%-75.0% | Carbonate and gypsum dissolution, groundwater over-exploitation, agricultural fertilization, domestic sewage | High nitrate (65.1 mg/L, exceeding WHO standards) |

Industrialization and Anthropogenic Contamination

Industrial activities introduce distinct chemical signatures to groundwater systems, often characterized by elevated concentrations of specific ions, heavy metals, and industrial solvents. In the Recife Metropolitan Region of Brazil, a complex "biogeochemical patchwork reactor" has developed in shallow aquifers, where anthropogenic inputs from sewage and industrial effluents interact with natural attenuation processes [14]. This system exhibits contrasted redox states that control the fate of contaminants, with potential natural attenuation occurring especially for nitrogen and sulfur species [14].

The Taejon study employed factor analysis to distinguish anthropogenic inputs from natural weathering processes, revealing that HCO3- and NO3- concentrations had the highest factor loadings on two separate factors representing natural processes and human activities respectively [12]. The results indicated that levels of Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, Cl- and SO42- derived from both pollution sources and natural weathering reactions, illustrating the challenge of disentangling anthropogenic influences in urbanized settings [12]. Industrialization further contributes to groundwater degradation through inadequate waste disposal, accidental chemical releases, and atmospheric deposition of industrial emissions.

Infrastructure Development and Its Consequences

Urban infrastructure creates multiple pathways for groundwater contamination while simultaneously altering flow regimes. Buried infrastructure including roads, sewers, septic systems, gas and electric lines, and building foundations are all vulnerable to groundwater rise and corrosion from saltwater intrusion [6]. Aging and leaking sewage networks represent a particularly significant contamination source in rapidly urbanizing areas, where approximately 50% of transported water may be lost through defective systems [14].

The style of urban development further influences hydrochemical outcomes. Research indicates that urban spatial structure has transformed from highly concentrated compact forms to more irregular, discontinuous patterns characterized by "leapfrogging" or "ribbon" development [15]. These dispersed urbanization patterns increase the spatial extent of impervious surfaces, reducing natural recharge while expanding the area subject to contaminant loading. Additionally, infrastructure demands drive extensive groundwater extraction, potentially inducing seawater intrusion in coastal settings through reduction of freshwater hydraulic heads [11].

Table 2: Infrastructure-Related Threats to Coastal Groundwater Identified in Multiple Studies

| Infrastructure Type | Primary Impact Mechanisms | Documented Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Water Supply Systems | Groundwater over-extraction | Seawater intrusion, saltwater upconing, land subsidence [11] |

| Sewage Networks | Leakage from defective systems | Nitrate, ammonium, and chloride contamination; microbial pollution [14] |

| Transportation Networks | Impervious surface creation | Reduced recharge, increased runoff, hydrocarbon and heavy metal contamination |

| Building Foundations | Physical infrastructure damage | Corrosion from saline groundwater, structural instability [6] |

| Industrial Facilities | Process water discharge, accidental spills | Heavy metal contamination, organic pollutant release [16] |

Compound Hazards in Coastal Urban Settings

Coastal urban areas face unique challenges due to the interplay between freshwater and seawater systems. Climate change exacerbates these issues through groundwater rise and seawater intrusion, posing significant threats to aging urban infrastructure [6]. These "invisible groundwater threats" include water table rise, groundwater salinization, and compound man-made and climate-related groundwater changes [6]. The resulting impacts include damage to buried infrastructure, impaired wastewater systems, reduced surface drainage capacity, and rendering groundwater unsuitable for drinking purposes.

In Pinghu City, China, seasonal groundwater variations demonstrate the complex interplay of natural and anthropogenic factors, where seawater intrusion and heavy metal pollution collectively degrade groundwater quality [16]. This research identified arsenic and chromium as major carcinogenic risk factors, with their spatial distribution showing distinct patterns related to both natural hydrogeological conditions and human activity hotspots [16]. The compounding effects of multiple stressors create management challenges that transcend traditional single-issue approaches.

The physical process of seawater intrusion follows the Ghyben-Herzberg principle, where a small elevation of the fresh water head is sufficient to maintain equilibrium with denser seawater [11]. However, urbanization pressures disrupt this balance through multiple mechanisms including groundwater extraction, reduced freshwater recharge due to impervious surfaces, and sea level rise. The intrusion length (L) of seawater into coastal aquifers can be estimated as L ≈ kD²/(2αQ), where k is hydraulic conductivity, D is aquifer depth, α is approximately 40 (inverse relative density difference), and Q is fresh groundwater discharge to the sea per unit width [11]. This relationship highlights the sensitivity of coastal aquifers to changes in freshwater flux driven by urban water demands.

Diagram 1: Compound hazard pathways from urbanization drivers to groundwater impacts in coastal areas.

Methodologies for Investigating Urban Groundwater Systems

Field Sampling and Monitoring Protocols

Comprehensive assessment of urbanization impacts on groundwater requires rigorous sampling methodologies. The study in Shijiazhuang, China, employed longitudinal data collection from 19 groundwater monitoring sites across multiple decades, with samples collected during dry seasons to minimize seasonal precipitation effects [13]. Standardized protocols included: purging wells for 5-10 minutes until pH stabilization before sample collection; using high-density polyethylene sampling bottles rinsed three times with groundwater at the sampling site; acidifying samples for cation analysis to pH <2 with HCl; and storing all samples at 4°C in iceboxes prior to analysis [13].

Advanced monitoring approaches incorporate multilevel wells instrumented with electrical conductivity and water pressure sensors to capture vertical variations in groundwater chemistry and dynamics [6]. In coastal settings, monitoring should specifically target parameters indicative of seawater intrusion (Cl-, Na+, electrical conductivity) and anthropogenic contamination (NO3-, SO42-, specific industrial markers), with sampling frequency designed to capture both seasonal variations and long-term trends.

Analytical Framework and Statistical Approaches

Multivariate statistical methods have proven particularly valuable for disentangling complex urbanization influences on groundwater chemistry. Factor analysis, as applied in the Taejon study, enables researchers to identify the most important factors contributing to data structure and similarities between factors [12]. This approach allows differentiation between contributions from natural weathering processes and anthropogenic inputs.

Contemporary research employs increasingly sophisticated analytical frameworks. The Pinghu City study integrated hydrogeochemical analysis, positive matrix factorization for source apportionment, Entropy Water Quality Index development, Human Health Risk Assessment, and Monte Carlo Simulation to develop a comprehensive assessment framework [16]. This multi-method approach enables researchers to quantify contribution sources, assess quality status, evaluate health implications, and address uncertainty in their findings.

Table 3: Essential Analytical Techniques for Urban Groundwater Studies

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application in Urban Groundwater Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Major Ion Chemistry | Ion chromatography, ICP-MS, titration | Characterize fundamental hydrochemical facies and evolution [13] |

| Isotopic Tracers | δ¹¹B, δ¹⁸O-SO4, δ³⁴S-SO4 | Identify contamination sources and biogeochemical processes [14] |

| Statistical Analysis | Factor analysis, principal component analysis, cluster analysis | Distinguish natural vs. anthropogenic contributions to chemistry [12] |

| Risk Assessment | Human Health Risk Assessment, Monte Carlo Simulation | Quantify health risks and uncertainty in contaminated aquifers [16] |

| Spatial Analysis | Geostatistical interpolation, GIS overlay | Map contamination patterns and identify hotspot areas |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

A systematic approach to investigating urbanization impacts on coastal groundwater requires specialized methodologies and analytical tools. The following experimental workflow outlines key processes from field sampling to data interpretation:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for urban groundwater hydrochemical studies.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Solutions for Groundwater Studies

| Item Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Equipment | Multiparameter field meter (pH, EC, ORP, temperature) | In-situ determination of physical and chemical parameters [13] |

| Peristaltic pump or bailer | Groundwater sampling with minimal aeration | |

| High-density polyethylene sampling bottles | Chemical inert container for sample transport | |

| Portable filtration apparatus | Field filtration for specific analyte preservation | |

| Preservation Reagents | Hydrochloric acid (HCl), trace metal grade | Sample acidification for cation analysis (pH <2) [13] |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Preservation for anion analysis in specific cases | |

| Chemical preservatives for nutrient analysis | Various preservatives for NO3-, NH4+, PO4³⁻ | |

| Laboratory Analytical | Ion chromatography system | Determination of major anions (Cl-, SO4²⁻, NO3-) [13] |

| Inductively coupled plasma systems (ICP-OES/MS) | Major and trace metal quantification [13] | |

| Gas chromatography systems | Analysis of dissolved gases (O2, CO2, CH4, N2) [14] | |

| Isotope ratio mass spectrometry | Stable isotope analysis for source attribution [14] | |

| Quality Control | Certified reference materials | Accuracy verification for analytical methods |

| Method blanks and replicates | Contamination assessment and precision determination | |

| Standard solutions for calibration | Instrument calibration and quantification |

The urbanization footprint on coastal groundwater systems manifests through complex, interacting pathways driven by land use change, industrial activities, and infrastructure development. The evidence from diverse global settings reveals consistent patterns of hydrochemical evolution characterized by increasing mineralization, contaminant specialization, and a gradual overlay of anthropogenic signatures on natural hydrochemical backgrounds. The compound hazards emerging in these environments—particularly the interaction between seawater intrusion and contamination from diverse urban sources—present particularly challenging management scenarios.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies that capture the temporal evolution of groundwater systems across urbanization gradients, with enhanced focus on the interface between surface and subsurface systems. The development of advanced monitoring technologies, including high-resolution sensors for continuous chemical measurement, will provide richer datasets for understanding dynamic processes. Additionally, interdisciplinary approaches that integrate hydrogeology, urban planning, social science, and materials science offer promise for developing more resilient water management strategies in increasingly urbanized coastal regions [6]. As climate change and population growth intensify pressures on coastal groundwater resources, understanding and mitigating the urbanization footprint becomes increasingly critical for ensuring sustainable water futures.

Groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas represents a critical field of study, as these regions face intense anthropogenic pressures while being particularly vulnerable to natural hydrogeological processes. The interplay between human activities and coastal dynamics creates a complex environment where multiple contaminants of concern co-occur and interact. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of three major contaminant categories—nitrate, heavy metals, and salinity—that collectively drive groundwater quality degradation in these sensitive environments. Understanding the sources, pathways, interactions, and transformation mechanisms of these contaminants is essential for developing effective monitoring and remediation strategies to protect coastal groundwater resources, which serve as vital sources of freshwater for nearly half the global population residing in coastal zones [10] [16].

Salinity Intrusion

Salinity intrusion in coastal aquifers manifests through multiple pathways and driving mechanisms. Primary salinization occurs through seawater intrusion, where saltwater infiltrates freshwater aquifers due to hydraulic gradient changes, while secondary salinization results from anthropogenic activities including drainage systems, groundwater pumping, and land use practices that mobilize connate saline waters [17] [16].

The key drivers include unsustainable groundwater extraction during dry periods, land subsidence, sea-level rise, and drainage systems that lower water tables below sea level [18] [17]. In the Emilia-Romagna region, Italy, drainage systems create vertical gradients that mobilize connate saline groundwater from deeper aquifer layers, resulting in unstable hydrodynamic conditions where freshwater lenses are thinner than 4.5 meters in most areas [17]. Similarly, in the Ravenna coastal area, land reclamation drainage has caused water tables to drop below sea level, creating upward gradients that transport saline water from deeper aquifer zones [17].

Table 1: Primary Drivers and Manifestations of Coastal Aquifer Salinization

| Driver Category | Specific Mechanisms | Geographic Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Sea-level rise, altered precipitation patterns, increased evaporation | Mediterranean regions, low-lying coastal plains |

| Anthropogenic | Groundwater over-extraction, land drainage, irrigation practices | Ravenna, Italy (drainage systems); Pinghu City (over-pumping) |

| Geological/Hydrological | Land subsidence, high aquifer conductivity, riverbed geometry | Northern Adriatic coast (land subsidence); Pearl River estuary |

Nitrate Contamination

Nitrate contamination predominantly originates from anthropogenic sources, with concentrations frequently exceeding recommended guidelines for drinking water. In coastal aquifers, nitrate presents a particularly complex challenge due to its high solubility and mobility, which facilitates transport through the subsurface into groundwater systems.

Multiple studies employing isotopic tracing (δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3−) have quantified nitrate sources in coastal environments. In Quanzhou City, China, research identified sewage and manure as the dominant contributor (66.6%), followed by soil nitrogen (21.5%), synthetic fertilizer (15.0%), and atmospheric deposition (2.5%) [10]. Similarly, in the Pearl River estuary, mean NO3–N concentrations reached 6.58 mg/L in porous medium groundwater and 3.07 mg/L in semiconfined fissure groundwater, with isotopic values ranging from +2.35‰ to +27.54‰ for δ15N–NO3− and +0.39‰ to +18.95‰ for δ18O–NO3−, confirming significant anthropogenic inputs [19].

Agricultural intensification represents a major contributing factor, with deep learning models identifying fecal coliforms (regression coefficient: 0.52) and electrical conductivity (0.48) as dominant predictors of nitrate contamination in agricultural and peri-urban areas [20]. The Metauro River plain in Italy exemplifies the long-term nature of this challenge, with nitrate pollution persisting since the 1970s when agricultural fertilizer use intensified, leading to concentrations exceeding 100 mg/L and necessitating engineered remediation solutions [21].

Heavy Metal Contamination

Heavy metal contamination in coastal environments arises from both geogenic and anthropogenic sources, with industrial activities, urban runoff, and agricultural practices serving as primary contributors. These metals persist indefinitely in the environment due to their low degradation rates and high stability, accumulating in sediments that act as both sinks and potential sources for future contamination [22].

The ecological impacts are profound, with heavy metals entering biological systems through bioaccumulation and biomagnification processes, leading to biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, and reduced ecosystem functionality [22]. In Pinghu City, positive matrix factorization analysis identified four primary sources: Cr-containing chemical agent discharges (25.88%), natural sources (29.81%), industrial sources (26.58%), and agricultural sources (17.73%) [16].

Table 2: Heavy Metal Sources, Pathways, and Environmental Behavior

| Metal Category | Primary Sources | Transport Pathways | Key Environmental Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Industrial discharge, natural geological weathering | Reductive dissolution of Fe/Mn-oxy-hydroxides | Carcinogenicity, groundwater quality degradation |

| Chromium (Cr) | Industrial applications, chemical manufacturing | Direct discharge, surface runoff | Carcinogenic risk, particularly in western/southwestern regions |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Phosphate fertilizers, industrial waste | Agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition | Bioaccumulation in shellfish, renal toxicity |

| Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg) | Vehicle emissions, industrial processes | Atmospheric deposition, urban runoff | Neurotoxicity, persistence in sediments |

Interactions and Compound Effects

Contaminants in coastal groundwater systems do not exist in isolation but interact through complex geochemical processes that significantly influence their mobility, bioavailability, and ultimate environmental impact. Salinity intrusion particularly modulates the behavior of other contaminants through multiple mechanisms including ion exchange, complexation, and solubility changes [23].

In contaminated coastal sites, trace elements demonstrate distinct clustering behavior in response to groundwater salinization. Group 1 (Se, Cu, Crtot, V, Ni) shows high correlation with electrical conductivity and chlorides due to strong affinity for chloride complexes and ion competition effects. Group 2 (Zn, Pb) exhibits less reactivity to salinization but greater sensitivity to cation/anion competition and organic matter content. Group 3 (Hg, As) mobility primarily correlates with Fe and Mn cycles, dominated by reductive dissolution of trace elements-bearing minerals (Fe/Mn/Al-oxy-hydroxides) and metal-organic complexes [23].

Nitrate behavior also changes under saline conditions. In the Pearl River estuary, denitrification processes identified through dual nitrogen isotopic evidence became the predominant biogeochemical process in porous medium groundwater and recharged fissure groundwater zones, with nitrate reduction occurring at salinity thresholds that promote anaerobic microbial activity [19]. This finding highlights the potential for natural attenuation under specific geochemical conditions, though this capacity varies significantly across different coastal aquifer systems.

Analytical Methodologies and Assessment Approaches

Field Sampling and Hydrochemical Characterization

Comprehensive groundwater assessment requires rigorous sampling protocols and multiple analytical techniques to characterize contaminant distribution and behavior. Standard practice involves collecting samples from monitoring wells using low-flow purging techniques to obtain representative groundwater samples without altering chemical parameters through excessive drawdown or aeration [19] [10].

Essential hydrochemical parameters include pH, electrical conductivity (EC), major ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−), and nutrient species (NO3−, NH4+, PO43−). For heavy metal analysis, samples are typically acidified to pH <2 using high-purity nitric acid to preserve metal solubility, with analysis conducted via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) [10] [16]. Isotopic analyses provide crucial information on contaminant sources and transformation pathways, with δ15N–NO3− and δ18O–NO3− ratios particularly valuable for identifying nitrate origins and denitrification processes [19].

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for coastal groundwater contamination assessment, showing the sequential stages from field sampling to risk evaluation with key methodological components at each stage.

Advanced Statistical and Modeling Approaches

Modern contamination assessment employs sophisticated statistical and computational methods to identify patterns, sources, and future risks in complex coastal groundwater systems.

Multivariate statistical techniques including principal component analysis (PCA) and positive matrix factorization (PMF) enable source apportionment of contaminants. In Pinghu City, PMF successfully quantified four contamination sources with their respective contributions, providing crucial information for targeted management strategies [16].

Machine learning and deep learning models represent cutting-edge approaches for predicting contamination patterns. The TabNet architecture, an attention-based deep learning model, achieved 81.60% overall accuracy in predicting nitrate contamination hotspots by integrating hydrochemical parameters (EC, Cl−, OM, FC) with remote-sensing indicators (NDVI, LU/LC) [20]. This approach outperformed traditional multilayer perceptron models and provided transparent feature attribution, identifying fecal coliforms and electrical conductivity as dominant predictors.

Health risk assessment models coupled with Monte Carlo simulation quantify potential human health impacts, particularly important for carcinogenic contaminants like arsenic and chromium. In Quanzhou City, health risk evaluation revealed population-dependent non-carcinogenic risk probabilities from nitrate: 4.31% (males), 5.71% (females), 13.93% (children), and 25.80% (infants), highlighting the heightened vulnerability of younger populations [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Reagents and Materials for Coastal Groundwater Contamination Research

| Reagent/Material | Technical Specifications | Application Context | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Trace metal grade, ≤ 0.5 ppb heavy metal impurities | Heavy metal sample preservation | Acidification to pH <2 for metal solubility preservation |

| Sulfuric Acid | Analytical grade, 0.1 N solutions | Nitrate sample stabilization | Sample acidification for nitrate preservation (1 mL/L, pH <2) |

| Certified Isotopic Standards | USGS34, USGS32, USGS35 KNO3/NaNO3 | Isotopic analysis of nitrate | Calibration reference for δ15N and δ18O measurements |

| Ion Chromatography Eluents | Carbonate/bicarbonate buffers, purity >99.9% | Major anion quantification | Mobile phase for separation of Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, F− |

| ICP-MS Tuning Solutions | Multi-element standards (Li, Y, Ce, Tl) | Trace metal analysis | Instrument calibration and mass axis alignment |

| Reference Materials | Certified river water, groundwater standards | Quality assurance/control | Verification of analytical accuracy and precision |

The evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas is governed by complex interactions between natural hydrogeological processes and intense anthropogenic pressures. Nitrate, heavy metals, and salinity represent three major contaminants of concern that frequently co-occur and interact in these environments, creating multifaceted management challenges. Salinity intrusion not only degrades water quality directly but also modulates the mobility and transformation of other contaminants through ion exchange, complexation, and redox processes. Comprehensive assessment requires integrated approaches combining traditional hydrochemical analysis with advanced statistical methods, isotopic tracing, and emerging machine learning techniques. Future research priorities should include long-term monitoring of seasonal dynamics, improved understanding of compound contaminant effects, development of predictive models incorporating climate change scenarios, and evaluation of remediation effectiveness in complex coastal settings. Such efforts will contribute significantly to the sustainable management of coastal groundwater resources, which remain indispensable for supporting ecosystems and human populations in increasingly pressurized coastal zones worldwide.

The evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas represents a critical research frontier in hydrogeology, essential for sustainable water resource management. This case study focuses on the south-eastern White Sea area in northwestern Russia, a region that exemplifies the complex interplay between Pleistocene-Holocene hydrogeological processes and contemporary anthropogenic pressures. The White Sea aquifers contain a paleo-hydrogeological archive of exceptional value, preserving distinct water masses from multiple climatic periods that have undergone complex geochemical evolution [24]. These aquifers are of paramount importance for supporting large urban centers, including Arkhangelsk, Novodvinsk, and Severodvinsk, which collectively require over 300,000 m³ of water per day [24]. Understanding the formation, evolution, and mixing of these groundwater bodies is not only scientifically significant but crucial for informing water supply strategies, managing industrial operations, and mitigating environmental risks in coastal urban settings.

Geological and Hydrogeological Setting

The study area encompasses the Northern Dvina Basin (NDB), an onshore continuation of the Dvina Bay that extends from the Dvina Estuary in the north-west to the Pinega River mouth in the south-east [24]. The aquifer system features a complex stratigraphic sequence including Middle-Upper Carboniferous carbonate-terrigenous formations, Upper Devonian-Lower Carboniferous terrigenous deposits, and Vendian terrigenous formations [24]. A critical characteristic of this system is the general lack of effective aquicludes between major aquifers, facilitating vertical and lateral groundwater mixing and creating temporally variable salinity conditions that complicate resource utilization [24].

The region's geological history includes repeated marine transgressions during the late Pleistocene and Holocene, evidenced by the widespread development of marine deposits, which have led to multiple episodes of aquifer salinization [24]. During continental periods, partial desalinization occurred through infiltration of atmospheric precipitation and meltwater from glaciers [24]. This dynamic history has created a multi-layered groundwater system with distinct chemical fingerprints reflecting different climatic and sea-level conditions.

Table 1: Stratigraphic Units and Hydrogeological Characteristics of the White Sea Study Area

| Geological Period | Formation | Lithology | Aquifer Designation | Key Hydrochemical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | Marine deposits | - | Shallow aquifers | Modern seawater influence, variable salinity |

| Late Pleistocene | Mikulino | Marine deposits | - | Seawater end-member |

| Late Pleistocene | - | - | Vpd aquifer | Brackish to salty water from mixing processes |

| Middle Pleistocene-Holocene | - | - | Vmz aquifer | Mixing of glacial meltwater and brines |

| Vendian | Terrigenous | Sandstones, siltstones | Deep aquifers | Brine influence, high mineralization |

Methodology for Groundwater Characterization

Field Sampling and Analytical Techniques

Comprehensive field campaigns conducted between 2006 and 2014 collected 56 water samples from various sources, including rivers, springs, and boreholes tapping Quaternary, Carboniferous, Kimberlite, and Vendian aquifers [24]. Samples were analyzed for major ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻) and environmental isotopes to determine groundwater origin, age, and evolution processes.

A critical component of the methodology involved precise dating of groundwater residence times using ¹⁴C and ²³⁴U/²³⁈U isotope systems, with particular attention to accounting for mixing processes between different water masses [24]. This approach allowed researchers to distinguish between modern recharge, Pleistocene water remnants, and mixed groundwater bodies.

Experimental Workflow for Groundwater Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated methodological approach for characterizing groundwater evolution in coastal aquifers:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Analytical Reagents and Materials for Coastal Groundwater Research

| Research Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application in White Sea Study |

|---|---|---|

| Radiocarbon (¹⁴C) Dating Standards | Determination of groundwater residence time | Age dating of "brackish1" water (32.96 ± 2.3 ka) [24] |

| Uranium Isotope Standards (²³⁴U/²³⁸U) | Complementary dating method for older groundwater | Validation of residence times and identification of mixing [24] |

| Ion Chromatography Reagents | Quantification of major ions (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻) | Characterization of hydrochemical facies and evolution trends [24] |

| Isotopic Reference Materials (δ¹⁸O, δ²H) | Tracing water origin and recharge processes | Identification of meteoric, glacial, and marine water sources [24] |

| Field Filtration Apparatus | In-situ sample preservation and particle removal | Prevention of chemical alteration between sampling and analysis [24] |

| Calibration Standards for ICP-MS | Trace element analysis | Detection of arsenic, selenium, and other trace constituents [25] |

Results: Groundwater Evolution and Mixing Processes

Analysis of the White Sea coastal aquifers revealed three principal evolutionary trends that have shaped the modern groundwater chemistry:

Evolutionary Trend 1: Late Pleistocene Seawater Mixing

The first identified trend involves mixing between a Late Pleistocene brackish water end-member and a Mikulino seawater end-member, resulting in the formation of strongly brackish and salty water in the Vpd aquifer [24]. Groundwater dating established a residence time of 32.96 ± 2.3 ka for the brackish end-member, indicating recharge likely occurred during Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3) [24]. This water mass represents a relict hydrological signature preserved from the Pleistocene era.

Evolutionary Trend 2: Late Pleistocene Fresh-Saline Interaction

The second evolutionary pathway involves mixing between a Late Pleistocene freshwater end-member and the previously formed salty Vpd aquifer water, producing a distinct brackish water type (brackish2) [24]. Dating of this mixed groundwater yielded residence times ranging from 25.1 ± 0.7 to 39.2 ± 6.3 ka, suggesting the freshwater component also recharged during MIS 3 [24].

Evolutionary Trend 3: Glacial Meltwater-Brine Mixing

The third trend comprises mixing between Middle Pleistocene-Holocene freshwater from melting glaciers and a deep brine end-member, forming the strongly brackish to salty water found in the Vmz aquifer [24]. Recharge of the glacial meltwater component occurred from the Middle Pleistocene through the Holocene (MIS 12-MIS 1), with intensive and rapid recharge following glacial melting enabling penetration to depths exceeding 200 meters [24].

Table 3: Quantitative Characteristics of Groundwater End-Members in White Sea Aquifers

| Groundwater Type | Residence Time (ka) | Recharge Period | Primary Geochemical Processes | TDS Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brackish1 (Late Pleistocene) | 32.96 ± 2.3 | MIS 3 | Water-rock interaction, cation exchange | Brackish |

| Brackish2 (Mixed) | 25.1 ± 0.7 to 39.2 ± 6.3 | MIS 3 | Mixing of fresh LP and salty Vpd waters | Brackish |

| Fresh MP-H (Glacial) | Middle Pleistocene-Holocene | MIS 12-MIS 1 | Rapid infiltration of meltwater | Fresh |

| Mikulino Seawater | Late Pleistocene | Mikulino Period | Marine transgression | Saline |

| Deep Brines | Paleozoic | - | Water-rock interaction, evapoconcentration | Brine |

Implications for Urbanized Coastal Area Management

The detailed characterization of White Sea aquifers provides critical insights for managing groundwater resources in urbanized coastal regions globally:

Water Supply Security for Urban Centers

The identification of relict Pleistocene water with specific chemical characteristics informs strategies for providing high-quality drinking water to major urban centers [24]. Understanding the distribution and quality of these deep groundwater bodies allows for targeted exploitation of resources less vulnerable to modern contamination.

Industrial Resource Development

The research supports the sustainable operation of an industrial iodine deposit associated with seawater from marine sediments of the Northern Dvina Basin [24]. The geochemical understanding enables optimized extraction while minimizing environmental impacts.

Environmental Risk Assessment

The study provides critical data for assessing risks associated with dumping saline drainage water from an exploited diamond deposit into the Zolotitsa River [24]. Understanding natural groundwater chemistry baselines and flow paths enables prediction of contaminant transport and potential ecosystem impacts.

The White Sea aquifer system represents a natural laboratory for studying the complex evolution of groundwater chemistry in coastal urban settings. Through integrated hydrochemical and isotopic analysis, researchers have unraveled a multi-stage evolutionary history involving distinct mixing processes between Late Pleistocene brackish water, freshwater, seawater, and deep brines. The preservation of 32.96 ka old groundwater highlights the potential for deep aquifers to archive paleoenvironmental conditions while serving as modern water resources [24].

This case study demonstrates that effective management of groundwater resources in urbanized coastal areas requires a thorough understanding of both natural evolutionary trends and anthropogenic influences. The methodologies applied—including advanced dating techniques, mixing models, and geochemical analysis—provide a template for similar investigations in vulnerable coastal aquifers worldwide. As coastal urban populations continue to grow and climate change alters hydrological cycles, such detailed paleohydrogeological understanding becomes increasingly essential for sustainable water resource management.

Advanced Tools for Decoding Aquatic Systems: From Field Sampling to Integrated Modeling

Conventional and Emerging Analytical Techniques for Major Ions and Trace Elements

The evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas presents a complex analytical challenge, requiring precise determination of both major ions and trace elements. Understanding these hydrochemical compositions is fundamental to assessing water quality, identifying pollution sources, and supporting sustainable resource management in densely populated coastal regions [25]. Coastal aquifers, serving as critical freshwater resources for nearly one billion people worldwide, are increasingly vulnerable to multiple stressors including seawater intrusion, anthropogenic contamination, and natural geochemical processes [25] [16].

The analytical framework for characterizing groundwater encompasses techniques ranging from established conventional methods to emerging technologies with enhanced sensitivity and spatial resolution. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of these methodologies, detailing their principles, applications, and experimental protocols within the context of coastal groundwater research. Accurate measurement is particularly crucial for trace elements, defined as those having an average concentration of less than 100 parts per million (ppm) or 100 μg/g [26] [27], as their presence and speciation—even at ultra-trace levels (below 1 ppb)—can significantly impact human health and ecosystem integrity [26] [28].

Major Ion Analysis: Conventional Techniques and Protocols

Major ions (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻, NO₃⁻) constitute the primary dissolved species in groundwater and define its basic chemical character. Their analysis is the first step in understanding hydrochemical facies and geochemical processes.

Ion Chromatography (IC)

Principle and Application: Ion Chromatography is the benchmark technique for simultaneous determination of major anions and cations in water samples. It is particularly effective for quantifying common anions like chloride, sulfate, nitrate, and fluoride in coastal groundwater studies, where distinguishing between seawater intrusion and anthropogenic contamination is essential [29]. The technique separates ions based on their interaction with a resin-based stationary phase, followed by suppressed conductivity detection which enhances sensitivity by reducing background conductance [29].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Groundwater samples are collected in high-density polyethylene bottles. Prior to sampling, wells should be purged for at least 10 minutes to remove stagnant water. Samples are filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filters to remove particulates and stored at 4°C [10].

- Instrument Calibration: Prepare a series of multi-anion standard solutions (e.g., chloride, nitrate, sulfate) from certified stock solutions. A minimum of five calibration points is recommended to establish a linear calibration curve.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- System: Thermo Scientific Dionex Easion IC System or equivalent.

- Eluent: For anions, a carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (e.g., 1.8 mM Na₂CO₃/1.7 mM NaHCO₃) is commonly used. Modern systems allow for preparation from concentrates.

- Column: High-capacity anion exchange column (e.g., Dionex IonPac AS22).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Injection Volume: 25 μL.

- Analysis and Quantification: Samples are injected automatically. Ions are identified based on retention time and quantified by comparing peak area to the calibration curve. The method can be extended to include disinfection byproducts like bromate, chlorate, and chlorite [29].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) for Cations

Principle and Application: ICP-OES is a robust, multi-element technique for determining major and trace cations. Liquid samples are nebulized and transported to argon plasma, where high temperatures (6000–8000 K) excite atoms and ions. The emitted element-specific light is separated by a spectrometer and detected [30]. It is ideal for quantifying Ca, Mg, Na, and K in groundwater, providing a wide dynamic range.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Groundwater samples are typically acidified with ultrapure nitric acid (HNO₃) to a pH < 2 to prevent precipitation and adsorption of elements to container walls. For total element analysis, samples can be digested, though this is often unnecessary for major cations in filtered water.

- Instrument Calibration: Prepare multi-element calibration standards in a matrix matching the sample acid concentration.

- Operational Conditions:

- RF Power: 1.0–1.5 kW.

- Nebulizer Flow: 0.6–1.0 L/min.

- Plasma View: Radial for high concentrations; axial for improved detection limits.

- Analytical Wavelengths: Ca (317.933 nm), Mg (285.213 nm), Na (589.592 nm), K (766.491 nm).

Trace Element Analysis: Emerging and Advanced Techniques

Trace element analysis demands higher sensitivity and lower detection limits. Techniques have evolved to meet the need for accurate measurements at ultra-trace levels in complex matrices like coastal groundwater [26].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Principle and Application: ICP-MS is the leading technique for ultra-trace element analysis due to its exceptionally low detection limits (ppt to ppq range) and multi-element capability. It couples an ICP source with a mass spectrometer to separate and detect ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio. It is indispensable for quantifying trace metals (As, Cr, Cd, Pb, U) and rare earth elements (REEs) in groundwater, which serve as critical tracers for geochemical processes and anthropogenic impacts [31] [28]. Specialized configurations like ICP-MS/MS and MC-ICP-MS further enable interference removal and precise isotope ratio analysis, which is valuable for source apportionment [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Digestion (for total element analysis): For solid samples (e.g., sediments, suspended solids), a microwave-assisted acid digestion is performed.

- Transfer 0.25–0.5 g of dried, homogenized sample into a Teflon vessel.

- Add 5–10 mL of concentrated HNO₃ and 1–2 mL of HCl or HF (if silicate dissolution is required).

- Run a stepped temperature program (ramp to 180–200°C over 20 min, hold for 15 min).

- Cool, dilute with deionized water, and filter [30].

- Instrument Tuning and Calibration: Tune the instrument for optimal sensitivity (Ce, Co, In, Li oxides) and minimize doubly charged ions and oxide formation using a tuning solution. Use internal standards (e.g., Sc, Ge, In, Bi) to correct for matrix effects and instrumental drift.

- Operational Conditions:

- RF Power: 1.5 kW.

- Nebulizer: Micro-concentric or ESI PFA-ST.

- Nebulizer Flow: 0.9–1.1 L/min.

- Data Acquisition: Peak hopping or scanning mode; 3–5 points per peak.

Emerging and Solid-Sample Techniques

X-ray Based Techniques (XRF, XAS, XRD): These are powerful non-destructive methods for direct solid sample analysis. X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), both laboratory and portable (pXRF), provides rapid, in-situ elemental analysis of soils, sediments, and rocks, crucial for field screening and understanding geological controls on groundwater chemistry [27]. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), typically at synchrotron facilities, determines the speciation (oxidation state and local molecular environment) of trace elements, which governs their mobility and toxicity [27].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): LIBS uses a focused laser pulse to ablate a micro-volume of material, creating a plasma whose emitted light is analyzed. It offers rapid, minimally destructive multi-element analysis and is increasingly deployed in handheld formats for field exploration of REEs and other elements [31].

Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA): INAA is a nuclear technique that involves irradiating samples with neutrons to create radioactive isotopes, which are then quantified by their decay gamma-rays. It is a primary method for quantifying a wide range of elements, including REEs, with minimal sample preparation and no matrix digestion required [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Analytical Techniques for Trace Elements.

| Technique | Typical Detection Limits | Analytical Throughput | Key Strengths | Primary Applications in Coastal Groundwater Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS | ppt – ppq | High | Ultra-trace detection, multi-element, isotopic analysis | Quantifying toxic metals (As, Cd, Pb), REEs, source tracing |

| ICP-OES | ppb – ppm | High | Robust, wide linear dynamic range, low interference | Major and minor cations (Ca, Mg, Na, K, Fe, Mn) |

| IC | ppb – ppm | High | Simultaneous anion analysis, high precision | Major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻), seawater intrusion mapping |

| pXRF | ppm | Very High | In-situ, non-destructive, rapid screening | Field-based soil and sediment characterization |

| LIBS | ppm | Very High | Handheld capability, minimal sample prep | Field exploration and screening of REEs and metals [31] |

| INAA | ppb – ppm | Low | Non-destructive, minimal matrix effects | Validation of other methods, REE analysis [31] |

Integrated Analytical Workflow for Coastal Groundwater Studies

A systematic approach from field sampling to data interpretation is essential for reliable conclusions in coastal groundwater research. The workflow below integrates the techniques discussed to characterize hydrochemical evolution.

Step 1: Field Sampling and In-situ Measurement. The protocol begins with representative groundwater sampling from monitoring wells, ensuring purging until stable field parameters (pH, Electrical Conductivity, Dissolved Oxygen, Oxidation-Reduction Potential) are achieved [10]. Samples for cation and trace element analysis are filtered and acidified, while those for anion analysis are filtered only.

Step 2: Laboratory Analysis of Major Ions. Filtered samples are analyzed using IC for anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) and ICP-OES for major cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺). Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) is typically determined by acid-base titration in the field or lab. This data is used to construct Piper diagrams and classify hydrochemical facies (e.g., Cl-Na type indicating seawater influence) [10].

Step 3: Laboratory Analysis of Trace Elements. Filtered and acidified samples are analyzed using ICP-MS for a suite of trace elements, including potentially toxic ones like As, Cr, Cd, and Pb, as well as REEs. The results are used for health risk assessment and understanding geogenic contamination [16] [28].

Step 4: Isotopic and Advanced Solid Analysis. To identify nitrate sources (e.g., manure, fertilizers), stable isotopes of nitrogen (δ¹⁵N) and oxygen (δ¹⁸O) in NO₃⁻ are analyzed using isotope ratio mass spectrometry after sample preparation to convert nitrate to N₂O gas [10]. For solid samples like aquifer sediments, techniques like XAS and XRD are employed to determine the speciation of trace elements and the mineralogical hosts, which control their long-term release into groundwater [27].

Step 5: Data Integration and Interpretation. All data is integrated using statistical methods (e.g., Principal Component Analysis), geochemical modeling, and spatial analysis. This holistic view allows researchers to delineate the driving factors of groundwater chemistry, such as water-rock interaction, seawater intrusion, and anthropogenic pollution, and to assess associated health risks [16] [10].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

A successful analytical program relies on high-purity reagents and certified reference materials to ensure data quality and accuracy.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Groundwater Analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digesting acid; sample preservation and acidification. | Essential for dissolving metal cations and preventing their adsorption; purity is critical for low-blank ICP-MS analysis [30]. |

| High-Purity Deionized Water (>18 MΩ·cm) | Preparation of all standards, blanks, and dilution of samples. | Prevents contamination of trace elements; used for rinsing all labware [30]. |

| Certified Multi-Element & Anion Standard Solutions | Instrument calibration and quality control. | Used to create calibration curves and verify instrument performance over time. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Method validation and accuracy control. | CRMs with matrices similar to the studied groundwater or sediments (e.g., NIST 1640a) are analyzed to confirm reliable results [26]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Oxidizing agent in sample digestion. | Added with HNO₃ to enhance the decomposition of organic matter in solid samples [30]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Dissolution of silicate minerals. | Used with caution in closed-vessel microwave digestion for total dissolution of soil and sediment matrices [31]. |

| Carbonate/Bicarbonate Salts | Preparation of eluents for Ion Chromatography. | Used to create the mobile phase for the separation of anions [29]. |

The accurate characterization of major ions and trace elements in coastal groundwater is a multi-faceted endeavor that leverages a suite of complementary analytical techniques. From the routine power of IC and ICP-OES for major ions to the ultra-trace detection capability of ICP-MS and the speciation power of synchrotron-based XAS, the modern analytical toolkit provides researchers with an unprecedented ability to decipher complex hydrogeochemical narratives. As coastal regions continue to face intense pressure from urbanization and climate change, the integration of these conventional and emerging methodologies, following rigorous and validated protocols, is paramount for understanding groundwater evolution, assessing risks, and informing sustainable management policies to protect this vital resource.

The sustainable management of water resources, particularly in coastal areas experiencing rapid urbanization and climate change pressures, requires a deep understanding of groundwater systems. Within this context, the evolution of groundwater chemistry in urbanized coastal areas represents a critical research focus. Isotopic dating techniques, specifically using Carbon-14 (14C) and the Uranium isotope ratio (234U/238U), serve as powerful tools for quantifying groundwater residence times, flow dynamics, and mixing processes. These tracers provide temporal constraints essential for developing accurate conceptual models of aquifer behavior, identifying sources of salinization, and evaluating the vulnerability of groundwater to contamination and over-exploitation. This technical guide examines the principles, applications, and methodologies of these isotopic systems for researchers and scientists working in hydrogeology and environmental science.

Fundamental Principles of Isotopic Tracers

Carbon-14 (14C) Dating

Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope of carbon with a half-life of 5,730 years, making it ideal for dating groundwater with residence times ranging from approximately 1,000 to 30,000 years [32]. The method relies on measuring the residual concentration of 14C in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in groundwater. As water moves through an aquifer and isolates from sources of modern carbon, its 14C content decreases through radioactive decay, providing a measure of the time elapsed since recharge.

The application is complicated by geochemical processes that alter the carbon isotope composition. The dissolution of 14C-free carbonate rocks ("dead carbon") or the introduction of geogenic CO2 can dilute the initial 14C activity, making water appear older than its true age [32]. Furthermore, the input function is not constant; 14C activities in the unsaturated zone (14C~uz~) are commonly far lower than atmospheric values and decrease with depth, a critical factor often overlooked in residence time calculations [32].

Uranium (234U/238U) Activity Ratios

The 234U/238U dating method is based on the disequilibrium between these two isotopes in aqueous systems. In a closed system, they exist in secular equilibrium with an activity ratio of 1. However, in groundwater, activity ratios almost always exceed 1 due to two primary mechanisms: alpha recoil, where the decay of 238U ejects the daughter 234Th nucleus from the mineral grain into the surrounding water, where it decays to 234U; and preferential leaching of 234U from mineral surfaces damaged by the recoil process [33].

This isotopic fractionation results in 234U excess in groundwater. The subsequent decay of this excess 234U along flow paths, along with mixing of different water masses, allows the 234U/238U activity ratio to be used as a tracer of water-rock interaction, flow paths, and residence time on timescales up to ~1.5 million years [34] [35]. Unlike 14C, uranium is largely conservative under oxidizing conditions, making it a robust tracer where carbon system corrections are problematic.

Applications in Coastal Groundwater Research

The combined use of 14C and 234U/238U is particularly powerful in constraining the complex hydrogeology of coastal systems. The following table summarizes key applications and findings from field studies.

Table 1: Summary of 14C and 234U/238U applications in groundwater studies

| Study Location | Isotopic Tracers Used | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kurnub Group Aquifer (Israel) | 234U/238U, 81Kr | Systematic exponential decrease in 234U/238U AR downflow allowed estimation of a long-term average flow rate of 24 cm/year and maximum residence times of ~1.3 million years. | [35] |

| Complexe Terminal Aquifer (Tunisia) | 234U/238U, 14C, δ13C | 234U/238U activity ratios distinguished between aquifer lithologies (carbonates: 1.1-1.8; sandy: 1.8-3.2). 14C dating indicated recharge occurred during the end of the last Glacial and throughout the Holocene (<22 ka). | [34] |