Contaminants of Emerging Concern: Environmental Exposure, Molecular Mechanisms, and Analytical Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs), addressing their environmental pathways, effects on human health, and advanced detection methodologies.

Contaminants of Emerging Concern: Environmental Exposure, Molecular Mechanisms, and Analytical Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs), addressing their environmental pathways, effects on human health, and advanced detection methodologies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science behind CECs, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and industrial chemicals. It critically reviews state-of-the-art analytical techniques, from high-resolution mass spectrometry to biomonitoring, and tackles persistent challenges in risk assessment and data interpretation. The scope extends to evaluating current regulatory frameworks and proposing integrative strategies for future environmental health research and policy, synthesizing findings from recent studies and technological advancements to guide scientific and clinical priorities.

Defining the Spectrum: Sources, Pathways, and Health Impacts of CECs

Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) represent a vast array of chemical and biological substances detected in the environment at concentrations that may pose newly identified risks to ecosystem and human health [1] [2]. These contaminants are characterized not necessarily by their novelty but by the growing scientific recognition of their environmental presence, persistence, and potential ecological and health impacts [2]. The term "emerging" reflects evolving understanding rather than recent invention, as many CECs have been in use for decades while their environmental fate remained unstudied [2].

The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines CECs as substances "known or anticipated to be in the environment, that may pose newly identified risks to human health or the environment" [1]. This conceptual framework encompasses natural and manufactured chemicals with features that complicate traditional risk assessment paradigms, particularly their ability to cause significant biological effects at very low concentrations and through mechanisms not captured by conventional toxicity testing [3].

Table 1: Major Categories of Contaminants of Emerging Concern

| Category | Representative Compounds | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals & Personal Care Products (PPCPs) | Antibiotics, antidepressants, synthetic hormones, fragrances [3] [2] [4] | Wastewater treatment plants, agricultural runoff, direct disposal [2] |

| Industrial Chemicals | Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) [4] | Industrial discharge, fire-fighting foams, consumer product leaching [4] |

| Pesticides | Glyphosate, malathion, current-use formulations [2] [5] | Agricultural and urban runoff, atmospheric deposition [2] |

| Engineered Materials | Microplastics, nanoparticles [6] [2] | Plastic degradation, consumer products, industrial applications [6] |

| Biological CECs | Antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), antibiotic resistant genes (ARG) [2] | Wastewater discharge, agricultural operations [2] |

Analytical Methodologies for CEC Detection

Sample Collection and Preparation

Comprehensive CEC monitoring requires sophisticated sampling strategies across multiple environmental compartments. For aqueous matrices including irrigation water, infiltration water, and groundwater, solid-phase extraction (SPE) represents the most widely employed concentration technique [7]. This method involves passing water samples through cartridges containing specialized sorbents that selectively retain target analytes, followed by elution with organic solvents. For solid matrices including soil and sediment, ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE) and pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) have demonstrated efficacy in recovering diverse CECs while minimizing compound degradation [7].

Critical considerations for sample integrity include:

- Matrix Characterization: Measurement of pH, electrical conductivity, total organic carbon, and suspended solids to interpret extraction efficiency [7]

- Preservation: Immediate stabilization with appropriate preservatives (e.g., sodium azide) and storage at -20°C to prevent microbial degradation [7]

- Quality Assurance: Implementation of procedural blanks, matrix spikes, and surrogate standards to account for analytical artifacts and recovery variability [7]

Instrumental Analysis

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) employing triple quadrupole analyzers represents the gold standard for CEC quantification in environmental matrices [7]. This platform provides the sensitivity, selectivity, and multi-residue capability essential for detecting trace-level contaminants (typically ng/L to μg/L) in complex environmental samples.

Table 2: Optimized LC-MS/MS Parameters for Multi-Residue CEC Analysis

| Parameter | ESI+ Conditions | ESI- Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Solvent A: Ultrapure water with 0.1% formic acid; Solvent B: MeOH with 0.1% formic acid [7] | Solvent A: Ultrapure water with 1 mM ammonium fluoride; Solvent B: MeOH:AcN 65:35% (v/v) [7] |

| Ion Source Settings | Drying gas flow: 14 L/min; Nebulizer pressure: 35 psi; Drying gas temperature: 250°C; Sheath gas temperature: 350°C; Sheath gas flow: 12 L/min; Nozzle voltage: 500 V; Capillary voltage: 3500 V [7] | Same as ESI+ with polarity reversal |

| Data Acquisition | Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) with optimized fragmentor voltages and collision energies for each compound [7] | Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) with optimized fragmentor voltages and collision energies for each compound [7] |

Method validation studies demonstrate that this approach can simultaneously quantify 40 CECs in aqueous matrices and 28 in solid matrices with acceptable accuracy (70-120% recovery) and precision (<20% RSD) across diverse environmental samples [7]. The methodology effectively controls matrix effects through careful optimization of sample clean-up procedures and application of matrix-matched calibration standards.

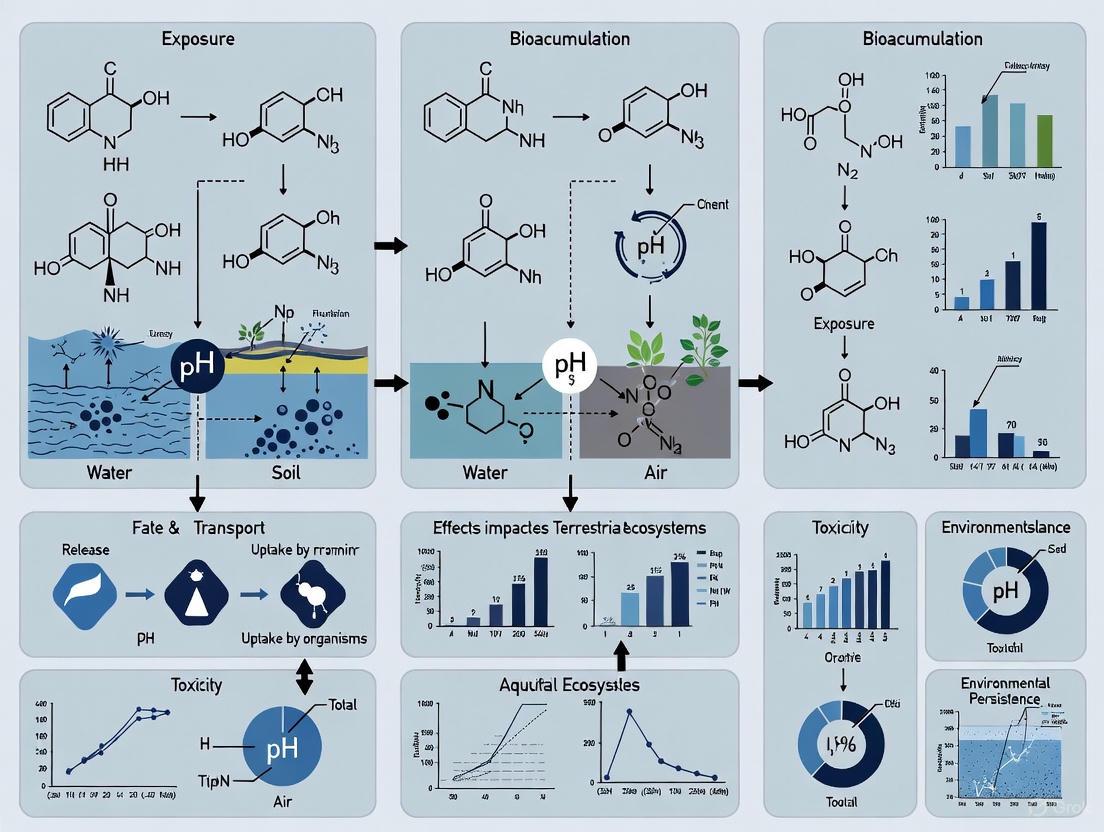

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for CEC Analysis in Environmental Matrices

Environmental Fate and Ecological Effects

Pathways and Persistence

CECs enter aquatic environments primarily through point sources such as wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents, industrial discharges, and hospital outflows [2]. Even with advanced treatment technologies, many CECs pass through WWTPs unaltered or only partially transformed, creating a continuous introduction pathway [2]. Non-point sources including agricultural runoff (carrying pesticides and veterinary pharmaceuticals) and urban stormwater (containing automotive chemicals, PPCPs, and microplastics) represent additional significant contribution routes [6] [2].

While some CECs demonstrate limited environmental persistence, their continuous release creates "pseudo-persistent" contamination scenarios, wherein transformation and removal processes are outpaced by ongoing inputs [2]. This phenomenon is particularly relevant for pharmaceuticals and personal care products designed for biological activity, which may retain their efficacy despite dilution in receiving waters.

Mechanisms of Ecological Impact

CECs pose unique challenges to aquatic organisms through several distinct mechanisms:

Endocrine Disruption: Many PPCPs and industrial chemicals function as endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) that alter normal hormonal functions in aquatic organisms [3] [2]. These substances can mimic or block natural hormones, leading to reproductive impairment, developmental abnormalities, and population-level consequences. The EPA notes that EDCs may cause effects that only manifest during later life stages after early-life exposure, complicating traditional toxicity assessment [3].

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: Lipophilic CECs including PBDEs and PFCs accumulate in tissue and increase in concentration as they move up food chains [4]. This biomagnification results in top predators experiencing body burdens several orders of magnitude higher than environmental concentrations, with documented population declines in vulnerable species [5] [4].

Antimicrobial Resistance Promotion: The environmental presence of antibiotics, preservatives, disinfectants, and biocides contributes to the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [2] [5]. AMR represents a rapidly escalating global health emergency that undermined antibiotic effectiveness and contributed to approximately five million deaths in 2019 [5].

Figure 2: Environmental Fate and Effects Pathway of CECs in Aquatic Ecosystems

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CEC Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| SPE Cartridges | Oasis HLB (Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance), 60 mg, 3 mL [7] | Extraction and concentration of diverse CECs from aqueous matrices |

| LC-MS/MS Mobile Phase | ESI+: 0.1% formic acid in water/MeOH; ESI-: 1 mM ammonium fluoride in water/MeOH:AcN [7] | Chromatographic separation with optimized ionization efficiency |

| Internal Standards | Isotope-labeled analogs of target compounds (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) [7] | Correction for matrix effects and quantification accuracy |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Ethyl Acetate (HPLC grade) [7] | Compound extraction from solid matrices and SPE elution |

| QuEChERS Kits | Pre-packaged salts and sorbents for dispersive solid-phase extraction [7] | Rapid sample preparation and clean-up for complex matrices |

Regulatory Framework and Research Priorities

The regulatory landscape for CECs remains fragmented, with significant gaps in monitoring and governance. The European Union's Water Framework Directive establishes environmental quality standards for only 45 priority substances, representing a small fraction of known CECs [2]. In the United States, the EPA has initiated a multi-year process to modernize its 1985 water quality criteria guidelines to better address the unique challenges posed by CECs, particularly endocrine disruptors that exhibit low acute toxicity but cause significant reproductive effects at very low exposure levels [3].

Critical research priorities identified include:

Risk-Based Prioritization: Development of frameworks to classify CECs and prioritize those of greatest concern based on integrated exposure and effects data [6]. Southern California Coastal Water Research Project (SCCWRP) is leading efforts to populate such frameworks with decade-long monitoring data to identify CECs with the highest potential for negative ecological impacts [6].

Global Data Equity: Addressing the substantial imbalance in CEC monitoring data, with approximately 75% of studies focused on North America and Europe despite the majority of the global population residing in Asia and Africa [5]. This geographical bias risks development of management strategies inappropriate for regions with different pollution profiles and environmental conditions [5].

Advanced Treatment Assessment: Evaluation of nature-based solutions and advanced treatment technologies for CEC removal, including constructed wetlands and vegetation filters that promote natural attenuation processes through soil-plant-microorganism systems [7]. Research demonstrates these approaches offer sustainable alternatives particularly suited to small communities where economic constraints limit conventional advanced treatment implementation [7].

Environmental exposure to contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) presents a critical research frontier in understanding ecological and public health risks. These pollutants, originating from diffuse and point sources, traverse complex pathways through agricultural, wastewater, and urban systems, often escaping conventional treatment processes. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of the primary sources, pathways, and environmental dynamics of these contaminants, framing them within the broader context of environmental exposure science. The persistence, bioaccumulative potential, and unknown toxicological profiles of many CECs highlight the urgent need for a multidisciplinary approach that integrates advanced monitoring, sophisticated analytical techniques, and innovative remediation technologies to mitigate their impacts on ecosystems and human health [8].

Contaminant Profiles and Quantitative Source Apportionment

The environmental burden of CECs is distributed across multiple primary sources. The tables below summarize the key contaminant classes and their typical loads from major anthropogenic pathways.

Table 1: Primary Contaminant Classes from Major Environmental Pathways

| Source Pathway | Key Contaminant Classes | Representative Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Runoff | Nutrients, Pesticides, Sediments, Pathogens | Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Atrazine, Glyphosate, E. coli [9] [10] [11] |

| Wastewater Discharge | Pharmaceuticals, Personal Care Products (PCPs), Nutrients, Surfactants | Carbamazepine, Triclosan, Ibuprofen, Bisphenol A [8] [12] [13] |

| Urban Stormwater Runoff | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), Heavy Metals, Pesticides, Microplastics | Fluoranthene, Pyrene, Copper, Zinc, DEET, Phthalates [14] [15] |

Table 2: Quantitative Load from Primary Sources (United States)

| Pollutant | Agricultural Runoff (Annual Estimate) | Wastewater Discharge (Daily Volume) | Urban Stormwater (Findings from National Study) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | 12 million tons (fertilizer application) [11] | --- | Episodic loads often exceed those from wastewater plants [14] |

| Phosphorus | 4 million tons (fertilizer application) [11] | --- | --- |

| Pesticides | ~500,000 tons [11] | --- | Frequently detected; numerous pesticides per event [14] |

| Wastewater Volume | --- | 34 billion gallons [12] | --- |

| Organic Chemical Mixtures | --- | --- | Median: 73 chemicals/site; Cumulative conc. up to 263,000 ng/L [14] |

Environmental Pathways and Fate of Contaminants

Contaminants follow distinct hydrological and engineered pathways from their sources to receiving environments, with their fate determined by chemical properties and ecosystem processes.

Agricultural Runoff Pathway

Agricultural runoff is a non-point source of pollution, primarily driven by precipitation and irrigation events. Water flows over fields, picking up excess nutrients, pesticides, and soil sediments, subsequently discharging into groundwater or surface water bodies like streams and rivers [9] [10]. A significant environmental impact is eutrophication, where excess nitrogen and phosphorus stimulate algal blooms. The subsequent decomposition of this algal biomass depletes dissolved oxygen, creating hypoxic "dead zones" that are incapable of supporting most aquatic life, as exemplified by the annual 6,000-square-mile dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico [9] [10]. This pathway also facilitates the transport of pathogens from animal waste and pesticides, which can cause sublethal and lethal effects on aquatic organisms and bioaccumulate through the food web [9] [11].

Wastewater Discharge Pathway

Wastewater systems collect effluent from domestic and industrial sources, channeling it to treatment plants (WWTPs). While conventional WWTPs effectively remove many pollutants, a wide range of CECs, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and plasticizers, are often recalcitrant to treatment and are released into receiving waters with the effluent [8] [12]. Treated wastewater is a recognized point source of nutrients and CECs to rivers, lakes, and coastal waters [12]. Septic systems, used by approximately 20% of U.S. households, represent another significant pathway; system failures can lead to the contamination of groundwater and nearby surface waters with nutrients and pathogens [12].

Urban Stormwater Runoff Pathway

Urban stormwater runoff is a complex mixture of contaminants washed from impervious surfaces such as roads, parking lots, and roofs during rain events. This pathway is a major conveyor of hydrocarbons (e.g., PAHs), heavy metals, pesticides, and household chemicals [14] [15]. A multi-agency national study demonstrated that stormwater transports substantial mixtures of bioactive contaminants, with the number and concentration of chemicals positively correlated with the density of impervious surfaces and urban development [14]. The study noted that episodic storm-event organic concentrations and loads were comparable to, and often exceeded, those of daily wastewater plant discharges [14]. Atmospheric deposition and vehicular transportation are identified as major ongoing sources of urban stormwater pollution [15].

Urban contaminant transport pathway from sources to receiving waters.

Advanced Methodologies for Exposure Assessment

Tracking the fate and exposure of CECs requires sophisticated sampling and analytical protocols.

National Stormwater Contaminant Study Protocol

A seminal multi-agency study established a rigorous methodology for characterizing the national-scale contaminant profile of urban stormwater [14].

- Site Selection & Sampling: The study collected 50 flow-weighted composite samples from 21 sites across 17 states. Samples were collected from stormwater conveyance infrastructure discharging mixed runoff from residential, commercial, and industrial landscapes. Both automated refrigerated samplers and manual isokinetic samplers were employed to collect 10-L composite samples across the storm-runoff hydrograph [14].

- Analytical Techniques: Samples were analyzed for 438 organic chemicals and 62 inorganic chemicals/parameters using eight analytical methods. Key techniques included Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for pharmaceuticals, Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) for hormones, and GC-MS for household chemicals, pesticides, and semivolatiles. Inorganic parameters, including trace elements and total mercury, were analyzed via established EPA methods [14].

- Quality Assurance: A comprehensive QA/QC protocol was implemented, including field equipment blanks, laboratory reagent water blanks, and field replicates. Isotope-dilution standards or surrogate compounds were added to all organic samples prior to extraction to account for analytical variability [14].

Wastewater-Based Epidemiology (WBE)

WBE is an innovative, non-invasive tool for assessing community-wide exposure to CECs by analyzing chemical biomarkers in raw wastewater [13].

- Concept & Workflow: WBE estimates the collective exposure of a population serviced by a specific wastewater treatment plant. The core principle involves the selection of specific human excretion products (biomarkers) of a contaminant, sampling raw wastewater, and using analytical techniques to quantify the biomarkers. The measured concentrations are then back-calculated to estimate the population's exposure load [13].

- Biomarker Selection & Challenges: A critical step is the identification of appropriate biomarkers, which must be specific to human metabolism and sufficiently stable in the sewer environment. For instance, 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) is a common urinary metabolite of many pyrethroid pesticides but lacks specificity for a single compound. Stability tests are crucial, as some biomarkers (e.g., certain phthalate metabolites) can degrade significantly within 24 hours in wastewater, leading to underestimation of exposure [13].

- Application to Pollutants: WBE has been applied to assess exposure to pesticides, plasticizers (phthalates, bisphenols), personal care products, and heavy metals. For heavy metals, biomarkers can include the parental substance (e.g., total arsenic), metabolic biomarkers, or non-substance biomarkers like metallothionein (MT) or δ-Aminolevulinic acid (δ-ALA), which indicate broader metal exposure and toxicological effect [13].

Wastewater-based epidemiology workflow for exposure assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advanced research and monitoring in this field rely on a suite of specialized reagents, standards, and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Dilution Standards (iDS) | Internal standards for mass spectrometry; correct for matrix effects and analyte loss during sample preparation. | Added to all samples prior to extraction; crucial for achieving high-precision quantitation in complex environmental matrices [14]. |

| Surrogate Compounds | Monitor extraction efficiency and correct for variability in sample processing for analytes where a stable isotope-labeled analogue is unavailable. | Added at the beginning of the analytical procedure; recovery rates are used to adjust final reported concentrations [14]. |

| LC-MS/MS & GC-MS/MS Reagents | High-purity solvents and reagents for the extraction, separation, and detection of trace organic contaminants. | Enable multi-residue analysis of hundreds of CECs (e.g., pharmaceuticals, pesticides) at nanogram-per-liter levels [14] [13]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibrate analytical instruments and validate methods against certified, traceable values. | Essential for ensuring the accuracy of data for heavy metals and other inorganic analytes [14]. |

| Stable Biomarkers | Specific human metabolic products used as indicators of exposure in Wastewater-Based Epidemiology. | Must be resistant to degradation in sewer conditions; e.g., some phthalate metabolites and pesticide biomarkers [13]. |

Agricultural runoff, wastewater discharge, and urban stormwater represent three critical, interconnected pathways that facilitate the transport of CECs into the environment. Quantitative data and advanced methodological protocols, such as those from national stormwater studies and WBE, are essential for characterizing the complex nature of these contaminant mixtures. Understanding these primary sources and environmental pathways is foundational to the broader thesis of environmental exposure, enabling the development of targeted monitoring strategies, accurate ecological risk assessments, and effective remediation technologies to safeguard ecosystem integrity and public health. Future research must focus on the long-term ecological impacts of these complex mixtures and the development of standardized, actionable monitoring guidelines [8].

The study of molecular toxicity has evolved to encompass the complex interplay between environmental exposures and the human genome. A growing body of evidence indicates that environmental contaminants of emerging concern can induce toxicity through mechanisms that extend beyond direct genetic damage to include profound epigenetic alterations and gene-environment interactions (GEI). These mechanisms explain how exposures can reprogram gene expression and biological pathways without altering the underlying DNA sequence, with significant implications for disease etiology and public health [16] [17].

This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms through which environmental toxicants induce epigenetic changes and how genetic background modulates individual susceptibility. Within the broader context of environmental exposure research, understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing biomarkers of effect, advancing precision environmental health, and designing targeted therapeutic interventions against toxicant-associated diseases [18] [19].

Epigenetic Alterations Induced by Environmental Toxicants

Epigenetic mechanisms represent a crucial interface between environmental exposures and gene expression. The major classes of epigenetic modifications include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression, all of which can be perturbed by various environmental toxicants [16].

DNA Methylation Changes

DNA methylation involves the addition of methyl groups to cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, primarily mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). This modification typically leads to transcriptional repression when it occurs in promoter regions. Environmental toxicants can disrupt normal DNA methylation patterns through several mechanisms:

- Altered methyl donor availability: The universal methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is required for all methylation reactions. SAM synthesis depends on one-carbon metabolism, which requires nutrients including folate, methionine, and serine. Environmental toxicants can disrupt this metabolic pathway, thereby affecting SAM availability and global DNA methylation patterns [20].

- Inhibition of demethylation enzymes: Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes catalyze DNA demethylation. Certain environmental pollutants can inhibit TET activity, leading to hypermethylation of specific genomic regions [20].

- Direct modulation of DNMT expression: Studies have shown that phthalates and other environmental toxicants can directly alter the expression of DNMTs, leading to widespread changes in DNA methylation [16].

Phthalate exposure has been linked to organ-specific epigenetic changes in hormone-related genes, which associate with neurodevelopmental disorders, infertility, and metabolic diseases [16]. Strikingly, evidence from animal models supports the potential for transgenerational inheritance of these epigenetic changes, suggesting that toxicant-induced epigenetic alterations may persist across multiple generations [16].

Histone Modifications

Histone modifications constitute another major epigenetic mechanism vulnerable to environmental disruption. These post-translational modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination of histone tails, which collectively regulate chromatin structure and gene accessibility.

The balance of histone acetylation is maintained by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). This balance is particularly susceptible to metabolic disruptions because acetyl-CoA, the substrate for acetylation, is a central metabolite [20]. In cancer cells, metabolic reprogramming often increases acetyl-CoA production through various pathways, including:

- Fatty acid oxidation producing mitochondrial acetyl-CoA

- ACLY-mediated conversion of citrate to cytosolic acetyl-CoA

- ACSS2-mediated synthesis of acetyl-CoA from acetate during metabolic stress [20]

Environmental toxicants can mimic this effect by disrupting normal metabolic pathways, leading to altered histone acetylation patterns. Furthermore, histone methylation depends on SAM availability, creating another pathway through which toxicants can influence the epigenetic landscape [20].

Non-Coding RNA Regulation

Non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), have emerged as important mediators of toxicant-induced epigenetic changes. These molecules can regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and can themselves be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms.

Specific miRNAs, including miR-21, miR-155, and several lncRNAs, have been identified as intermediaries between environmental exposures and epigenetic remodeling [21]. Phthalate exposure has been shown to induce abnormal noncoding RNA expression patterns that contribute to its toxic effects [16].

Table 1: Environmental Toxicants and Their Epigenetic Targets

| Toxicant Class | Specific Examples | Primary Epigenetic Effects | Associated Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phthalates | DEHP, DBP, DEP | Altered DNA methylation of hormone-related genes; histone modifications; miRNA dysregulation | ADHD, infertility, metabolic disorders [16] |

| Heavy Metals | Uranium, Arsenic, Mercury | DNA methylation changes; altered histone acetylation; miRNA expression | Autoimmune disorders, neurodevelopmental issues [19] [21] |

| Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFOA, PFOS | Immunotoxicity through epigenetic mechanisms; altered DNA methylation | Immune suppression, inflammatory diseases [19] |

| Airborne Particulates | PM2.5, PM10 | DNA methylation shifts; histone modifications; chromatin accessibility changes | Respiratory inflammation, cardiovascular disease [21] |

Gene-Environment Interactions in Toxicology

Gene-environment interactions occur when the effect of environmental exposure on disease risk differs based on an individual's genetic makeup. The statistical definition of GEI exists on both additive and multiplicative scales, but the biological reality is far more complex [18].

Fundamental Concepts and Models

The traditional model of GEI can be represented mathematically as:

P = G + E + G×E

Where P represents the phenotype, G represents genetic factors, E represents environmental exposures, and G×E represents their interaction. However, contemporary understanding recognizes that this simplified model fails to capture the dynamic nature of these interactions across the lifespan and their dependence on developmental timing [18].

The concept of "window of opportunity" emphasizes that the timing of exposure to environmental agents is critical in determining health outcomes. Exposures during sensitive developmental periods, such as prenatal or early childhood stages, may have more profound and lasting effects than exposures during adulthood [17].

Biological Mechanisms Underlying GEI

Several biological processes mediate gene-environment interactions in toxicology:

- Xenobiotic Metabolism: Genetic polymorphisms in metabolic enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 family, glutathione S-transferases) can significantly alter an individual's capacity to detoxify environmental chemicals, leading to differential susceptibility [22] [18].

- Cellular Distribution and Transport: Transporters determine the localization, accumulation, and elimination of toxicants from body compartments. Genetic variations in these transporters can dramatically affect tissue concentrations of chemicals and their toxicologically effective concentrations at target sites [22].

- Cellular Resilience and Repair Mechanisms: Cells have evolved elaborate mechanisms to compensate, buffer, and repair damage. Genetic differences in these resilience pathways can determine why some individuals remain healthy despite exposure while others develop disease [22].

- Target Molecular Interactions: Genetic variations can alter the affinity between toxicants and their molecular targets, potentially leading to differential activation of adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) [22].

Table 2: Documented Gene-Environment Interactions in Human Health

| Gene | Environmental Exposure | Health Outcome | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1-Associated Protein (BAP1) | Asbestos | Mesothelioma | Impaired DNA repair and cellular response to asbestos fibers [18] |

| Chromodomain Helicase DNA-Binding Protein 8 (CHD8) | Pesticides | Autism Spectrum Disorder | Disrupted chromatin remodeling and gene expression in neurodevelopment [18] |

| Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated (FTO) | Physical Activity | Obesity | Altered energy homeostasis and metabolic programming [18] |

| Dopamine Receptor D4 (DRD4) | Parenting Style | ADHD | Modified neurodevelopmental trajectory and behavioral regulation [18] |

| Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) | Organophosphorous Pesticides | Neurological Symptoms | Differential detoxification capacity due to enzyme polymorphisms [23] |

Integrated Molecular Pathways

Environmental toxicants can activate conserved molecular pathways that interface with both epigenetic machinery and immune function, creating a complex network of interactions that ultimately determine toxicological outcomes.

Shared Signaling Pathways in Toxicant Response

Multiple classes of environmental pollutants converge on common signaling pathways that mediate their toxic effects:

- Toll-like Receptor (TLR)-NF-κB Signaling: Various environmental toxicants can activate TLR signaling, leading to NF-κB activation and subsequent inflammatory responses. This pathway can induce epigenetic changes by recruiting chromatin-modifying enzymes to inflammatory gene promoters [21].

- NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation: The NLRP3 inflammasome serves as a sensor for environmental stressors and can be activated by multiple toxicants. Inflammasome activation leads to caspase-1-mediated cytokine maturation and inflammation, with associated epigenetic changes [21].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Pathways: Many environmental toxicants induce oxidative stress by generating ROS. ROS can function as signaling molecules that modulate the activity of epigenetic enzymes, including HDACs, HATs, and TET proteins [21].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated signaling pathways through which environmental pollutants exert immune-epigenetic effects:

Metabolic-Epigenetic Interplay in Toxicity

Cellular metabolism is intricately connected to epigenetic regulation, as many epigenetic modifications depend on metabolic cofactors. This relationship creates a mechanism through which environmental toxicants that disrupt metabolism can subsequently alter the epigenome:

- SAM-Dependent Methylation: The ratio of SAM to SAH (S-adenosylhomocysteine) regulates the activity of DNMTs and HMTs. Toxicants that affect one-carbon metabolism can shift this ratio and globally alter methylation patterns [20].

- Acetyl-CoA-Mediated Acetylation: Nuclear acetyl-CoA levels directly influence histone acetylation. Toxicants that disrupt mitochondrial function or energy metabolism can alter acetyl-CoA production and consequently affect histone acetylation [20].

- NAD+-Dependent Deacetylation: The NAD+-dependent sirtuin family of deacetylases links cellular energy status to epigenetic regulation. Environmental toxicants that affect NAD+ levels can influence sirtuin activity and gene expression patterns [20].

The integrated relationship between metabolic disruption and epigenetic changes in environmental toxicology can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research on epigenetic alterations and gene-environment interactions requires sophisticated methodological approaches that span multiple technological domains.

Assessing Epigenetic Modifications

Comprehensive evaluation of toxicant-induced epigenetic changes involves multiple complementary techniques:

DNA Methylation Analysis:

- Bisulfite Sequencing: The gold standard for DNA methylation analysis at single-base resolution. Treatment with bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing for precise mapping of methylation patterns.

- EPIC BeadChip Arrays: Provide a cost-effective method for profiling methylation at over 850,000 CpG sites throughout the genome, suitable for large epidemiological studies.

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing: Offers comprehensive methylation mapping across the entire genome, including non-CpG and repetitive regions.

Histone Modification Profiling:

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq): Utilizes antibodies specific to histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3) to pull down associated DNA fragments, which are then sequenced to map the genomic distribution of these marks.

- Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: Enables quantitative analysis of histone modifications without antibody bias.

Non-Coding RNA Analysis:

- Small RNA Sequencing: Identifies and quantifies miRNA expression changes in response to environmental exposures.

- lncRNA Microarrays and RNA-seq: Profile expression of long non-coding RNAs associated with toxicant exposure.

GEI Study Designs

Different study designs are employed to investigate gene-environment interactions:

- Candidate Gene Studies: Focus on pre-specified genes with known biological relevance to the exposure or disease. These studies have higher statistical power for the specific variants tested but are limited by prior knowledge.

- Genome-Wide Interaction Studies (GWIS): Test for interactions across the entire genome without prior hypothesis. While comprehensive, these studies require large sample sizes to achieve sufficient statistical power.

- Family-Based Designs: Utilize twin studies or family trios to control for genetic background and shared environment.

- Case-Only Studies: Estimate GEI by examining the correlation between genetic variants and environmental exposures among cases only. This design provides improved statistical power but requires the assumption that genes and environment are independent in the population.

Table 3: Methodologies for Assessing Biomarkers in Environmental Health

| Biomarker Category | Specific Methods | Applications in Environmental Toxicology | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Biomarkers | Mass spectrometry (targeted and untargeted), HPLC, GC-MS | Quantification of specific chemical residues and metabolites in biological matrices [24] | Requires validation of analytical performance; must consider kinetics of biomarkers |

| Effect Biomarkers | Cytogenetic assays (micronuclei, chromosome aberrations), oxidative stress markers, omics technologies | Detection of quantifiable changes in biochemical/physiologic parameters [24] | Multi-omics approaches allow comprehensive assessment but require sophisticated bioinformatics |

| Susceptibility Biomarkers | Genotyping of polymorphic variants, metabolic phenotyping | Identification of intrinsic susceptibility to adverse effects of exposure [24] | Genetic polymorphisms must have functional significance to be meaningful |

| Epigenetic Biomarkers | Bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq, miRNA profiling | Assessment of DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNA expression [16] [21] | Tissue-specificity and cellular heterogeneity must be considered in interpretation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advanced research on molecular mechanisms of toxicity requires specialized reagents and tools designed specifically for investigating epigenetic alterations and gene-environment interactions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Toxicity Mechanisms Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Enzyme Assays | DNMT Activity Assays, HDAC/HAT Activity Kits, HMT Inhibitor Screening | Quantifying changes in epigenetic enzyme activity following toxicant exposure [16] [20] | Measures catalytic function using colorimetric, fluorometric, or radioisotopic methods |

| Methylation Detection Reagents | Bisulfite Conversion Kits, Methylated DNA Standards, Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | DNA methylation analysis at specific loci or genome-wide [16] | Chemical or enzymatic conversion of DNA for methylation status determination |

| Chromatin Analysis Tools | ChIP-Validated Antibodies, Chromatin Accessibility Assays, Histone Modification Panels | Histone modification profiling and chromatin structure analysis [21] | Specific binding to epigenetic marks or assessment of nucleosome positioning |

| Gene Expression Profiling | miRNA Inhibition/ Mimic Systems, lncRNA Functional Assays, Pathway-Specific Reporter Constructs | Functional studies of non-coding RNAs in toxicant response [21] | Modulation of specific RNA molecules to determine functional consequences |

| Metabolic Epigenetic Probes | SAM/SAH Measurement Kits, Acetyl-CoA Quantitation Assays, NAD+ Detection Systems | Linking metabolic changes to epigenetic alterations [20] | Quantitative measurement of metabolic cofactors that influence epigenetic regulation |

| GEI Analysis Resources | GWIS Analysis Software, Genotyping Arrays, Exposure Assessment Platforms | Statistical analysis of gene-environment interactions [18] | Computational tools and genomic resources for interaction studies |

The investigation of epigenetic alterations and gene-environment interactions has fundamentally transformed our understanding of molecular toxicity mechanisms. Environmental toxicants can exert lasting biological effects through epigenetic reprogramming that influences gene expression patterns without altering DNA sequences. These effects are further modulated by individual genetic background through complex gene-environment interactions that determine susceptibility.

The integration of multi-omics approaches with advanced computational methods has created unprecedented opportunities to decipher these complex relationships. Future research directions should focus on developing temporally-resolved exposure assessments, expanding multi-ethnic GEI studies, and advancing epigenetic editing technologies for functional validation of findings.

Understanding these molecular mechanisms is essential for advancing precision environmental health, developing targeted intervention strategies, and informing evidence-based regulatory decisions to protect vulnerable populations from environmental toxicants. The continued elucidation of these complex interactions will ultimately enable more personalized approaches to environmental health protection and disease prevention.

Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) represent a diverse group of chemical and biological substances not commonly monitored or regulated in the environment, yet possessing potential for adverse ecological and human health effects. The scope of these contaminants is vast, with approximately 350,000 chemical substances in use that may enter the environment, while less than 1% are currently regulated by international conventions and environmental standards [25]. This regulatory gap represents a critical public health challenge, as global environmental pollution from all contaminants is estimated to cause approximately 9 million premature human deaths annually, with toxic chemical exposure contributing to over 1.8 million of these deaths [25].

This whitepaper synthesizes current epidemiological and experimental evidence linking CEC exposure to chronic disease outcomes, focusing on the biological mechanisms, advanced methodological approaches, and public health implications within environmental health research. We examine several prominent CEC classes including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs), and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [26]. Understanding the exposure pathways and health effects of these substances is essential for developing evidence-based public health interventions and regulatory policies.

Major CEC Classes and Exposure Pathways

Definition and Classification of CECs

The term "contaminants of emerging concern" refers to a heterogeneous group of synthetic or naturally occurring chemicals or microorganisms that are not commonly monitored in the environment but have the potential to cause known or suspected adverse ecological and/or health effects [26]. According to the Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC), CECs are formally defined as "substances and microorganisms including physical, chemical, biological, or radiological materials known or anticipated in the environment, that may pose newly identified risks to human health or the environment" [27].

CECs encompass several broad categories:

- Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs): Including antidepressants, blood pressure medications, over-the-counter drugs like ibuprofen, bactericides like triclosan, sunscreens, antifungal agents, and hormones [26].

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Synthetic compounds known as "forever chemicals" due to their environmental persistence [26] [28].

- Micro- and Nano-plastics (MNPs): Plastic fragments smaller than 5 mm (microplastics) and particles ranging between 1-1000 nm (nanoplastics) [26].

- Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs): Compounds that alter the normal functions of hormones [3].

- Biological Contaminants: Including viruses, pathogenic bacteria, protozoa, and antibiotic resistance genes [25].

Environmental Prevalence and Human Exposure Pathways

CECs enter the environment through multiple pathways, with wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) being a primary conduit for surface water contamination [29]. It is estimated there are over 900 streams in the US composed of at least 50% effluent, a phenomenon extending beyond arid to temperate regions due to increased urbanization and climate change [29].

Table 1: Primary Exposure Pathways for Major CEC Classes

| CEC Category | Environmental Sources | Primary Human Exposure Routes | Environmental Persistence |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | Industrial sites, firefighting foam, consumer products | Drinking water, food packaging, dust | Extremely high ("forever chemicals") |

| PPCPs | Wastewater effluent, agricultural runoff | Drinking water, food products | Variable; some highly persistent |

| Microplastics | Plastic waste degradation, personal care products | Seafood, drinking water, air inhalation | High; slow degradation |

| EDCs | Plasticizers, pesticides, industrial chemicals | Food, water, consumer products | Variable; some highly persistent |

The pervasive nature of CECs is demonstrated by their detection in virtually all environmental matrices, from deep ocean trenches to mountain peaks, and in biological samples from plants, animals, and humans [25]. For instance, microplastics have been found in various human organs, including the brain, placenta, liver, kidneys, lungs, and blood [25].

Epidemiological Evidence Linking CECs to Chronic Diseases

Developmental and Reproductive Health Effects

Strong epidemiological evidence connects CEC exposure with adverse developmental and reproductive outcomes. A pioneering study from the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) tracked 200 mother-baby pairs, measuring PFAS compounds in maternal blood during pregnancy and profiling infants' T-cell populations at birth, six months, and one year [30]. The findings revealed that by age 12 months, infants with higher prenatal PFAS exposure exhibited:

- Significantly fewer T follicular helper (Tfh) cells - vital for helping B cells produce strong, long-lasting antibodies

- Disproportionately more Th2, Th1, and regulatory T cells (Tregs)

- Immune profiles linked to allergies, autoimmunity, or immune suppression when out of balance [30]

This research provides the first evidence identifying changes in specific immune cells during development due to PFAS exposure, opening possibilities for early monitoring or mitigation strategies to prevent lifelong diseases [30].

The CLEAR research center in Detroit focuses on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as urban CECs, investigating their role in adverse birth outcomes. Detroit has the highest preterm birth rate in the country (15.2%), and researchers hypothesize that VOC exposure through vapor intrusion during early life incites inflammatory responses that reprogram developing immune systems, setting the stage for preterm birth and associated adverse health outcomes [31].

Neurodevelopmental and Behavioral Effects

Emerging evidence indicates concerning neurodevelopmental impacts from CEC exposure, with potential male-bias in vulnerability. University of Rochester research on PFHxA (a short-chain PFAS previously thought to be less harmful) found that early life exposure in male mice resulted in:

- Increased anxiety-related behaviors

- Memory deficits

- Decreased activity levels [30]

Researchers noted that finding behavioral effects only in males was reminiscent of the male-biased prevalence in many neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and ADHD, suggesting the male brain might be more vulnerable to environmental insults during neurodevelopment [30].

Immune Dysregulation and Allergic Diseases

CEC exposure appears to contribute to the disproportionate burden of allergic diseases in urban populations. URMC researchers discovered a previously uncharacterized subset of pro-allergic T helper 2 (Th2) cells with distinct molecular characteristics that are more frequently found in urban infants who later developed allergies [30]. The comparative analysis revealed:

- Urban infants had higher levels of aggressive pro-allergic Th2 cells

- Old Order Mennonite (rural) infants had more regulatory T cells that help maintain immune balance

- The farming environment, rich in microbial exposure, appears to support a more tolerant immune system [30]

This suggests that CECs and other environmental factors in urban settings may promote immune cells primed for allergic inflammation, providing new insight into why urban children are more prone to allergies than children from rural areas [30].

Carcinogenic and Metabolic Effects

Epidemiological evidence continues to accumulate regarding the carcinogenic potential of certain CEC classes. Long-term, low-dose exposure to PFAS has been linked to:

- Increased risk of breast cancer

- Reproductive dysfunction

- Birth defects

- Metabolic diseases [25]

Notably, the adverse health effects of many CECs often emerge after prolonged latency periods. For example, lung cancer resulting from exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may take 10 to 30 years to manifest, equivalent to delaying the onset of population-level disease burdens by approximately two decades [25].

Table 2: Chronic Disease Outcomes Associated with CEC Exposure

| CEC Category | Associated Health Outcomes | Strength of Evidence | Vulnerable Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | Immune dysfunction, thyroid disease, kidney/testicular cancer, elevated cholesterol | Strong human epidemiological evidence | Developing fetus, children |

| PPCPs | Antibiotic resistance, endocrine disruption, developmental reproductive effects | Growing evidence; mixture effects concerning | Aquatic organisms; human evidence emerging |

| Plasticizers (e.g., BPA, phthalates) | Developmental effects, reduced fertility, insulin resistance | Strong experimental; human evidence growing | Pregnant women, infants |

| Microplastics | Oxidative stress, inflammation, cellular damage | Emerging evidence; mechanism plausible | General population |

Methodological Approaches in CEC Research

Advanced Biomarker Development

Innovative biomarker approaches are essential for establishing connections between CEC exposure and health outcomes. The FDA-NIH Joint Leadership Council BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource defines a biomarker as a "characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or biological responses to an exposure or intervention" [32]. The historical development of biomarker science dates back to Dr. Herbert Needleman's pioneering work in the 1960s-70s using lead in teeth as a biomarker for lead neurotoxicity in children [32].

Modern approaches include:

- Non-invasive matrices: Placenta, cord blood, umbilical cord, hair, urine, saliva, vernix, and meconium for measuring fetal/neonatal biomarkers [32]

- Exhaled breath analysis: Emerging as a promising matrix for detecting and monitoring chemical exposures [32]

- Cell-free fetal DNA: Present in maternal blood as early as 10 weeks of pregnancy, used to detect chromosomal anomalies and expanding to environmental exposure assessment [32]

The biomarker development pathway requires rigorous validation, including demonstration of biological plausibility, analytical validation, and clinical validation for each intended use [32].

Transcriptomic and Systems Biology Approaches

Advanced molecular techniques are revealing subtle but significant health impacts of CEC exposure. An in-situ study on fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to WWTP effluent revealed significant neurobiological effects through RNA-sequencing analysis of brain tissues [29]. The experimental protocol included:

- Caged-fish exposure: Fish were deployed in modified mesh minnow traps above and below a WWTP effluent outfall for a 4-day (96 h) exposure during baseflow conditions [29]

- RNA-sequencing: Conducted on brain tissues to assess transcriptomic changes [29]

- Water sampling: Analyzed for 14 pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical degradates, with one sample analyzed for 113 pharmaceuticals/degradates and other CECs [29]

The results demonstrated 280 gene isoforms significantly differentially expressed in male fish and 293 gene isoforms in female fish between upstream and downstream sites, with only 13% overlap between sexes, indicating sex-dependent impacts on neuronal gene expression [29]. This systems biology approach, paired with functional enrichment analyses, identified novel gene biomarkers for effluent exposure that could expand monitoring of environmental effects.

Mixture Toxicity Assessment

A critical methodological challenge in CEC research involves assessing the combined effects of chemical mixtures. Traditional single-compound laboratory exposures may not accurately reflect real-world scenarios where organisms encounter complex mixtures [29]. When comparing transcriptomic results from real-world effluent exposure to those from single-compound studies, there was relatively little overlap in terms of gene-specific effects, bringing into question the application of single-compound exposures in accurately characterizing environmental risks [29].

This complexity is magnified by the dynamic nature of WWTP effluent, where composition fluctuates with patterns of human use and environmental factors that lead to differential attenuation [29]. The environmental risk of these contaminants remains largely undercharacterized, hampering the development of CEC mixture regulations [29].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Methodologies and Reagents

Analytical Methods for CEC Detection

Advanced analytical techniques are required to detect CECs at environmentally relevant concentrations (typically ng/L to μg/L). The most common approaches include:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Central to identification and quantification of polar CECs at trace levels [26] [28]

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Effective for volatile and semi-volatile compounds [26]

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Provides accurate mass measurements for identifying unknown compounds [26]

Supplementary methods include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for biological contaminants, and various biosensors [26]. For microplastics analysis, techniques include visual microscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and Raman spectroscopy, though methodological standardization remains a challenge [25].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Solutions for CEC Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Systems | HPLC, UPLC, GC | Separation of complex mixtures | Column selection critical for resolution |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, HRMS | Identification and quantification | Requires reference standards for quantification |

| Molecular Biology Assays | RNA-seq, PCR, ELISA | Biomarker discovery and validation | Sample quality critical for reliability |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Differential expression analysis, Pathway enrichment (GO, KEGG) | Data analysis and interpretation | Statistical rigor essential |

| Cell-Based Assays | Bioluminescent yeast estrogen screen (BLYES) | Endocrine disruption screening | High-throughput capability |

Experimental Models in CEC Toxicology

Various model systems provide complementary insights into CEC health effects:

- In vitro systems: Cell lines for high-throughput screening of toxicity mechanisms

- In vivo models: Zebrafish (Danio rerio) for developmental toxicity assessment [31], fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) for aquatic toxicology [29], and mouse models for immune and neurological effects [30] [31]

- Human epidemiological studies: Cohort designs tracking exposure and health outcomes over time [30] [31]

The CLEAR research center exemplifies this integrated approach, combining phytoscreening for VOC detection, sensor technology for real-time monitoring, zebrafish toxicity bioassays, pregnant mouse models, and human epidemiology in an at-risk population [31].

Public Health Implications and Regulatory Challenges

Risk Assessment and Management Gaps

Significant challenges exist in regulating CECs due to scientific and technical barriers:

- Toxicity assessment limitations: Traditional ecotoxicity tests for a single chemical cost approximately USD 118,000 on average, making comprehensive assessment of thousands of chemicals prohibitively expensive and time-consuming [25]

- Analytical limitations: Standardized protocols for detecting and quantifying many CECs are underdeveloped or nonexistent [25]

- Mixture effects: Risk assessment approaches struggle to address combined effects of multiple contaminants [29]

The European Union's REACH regulation addresses this by mandating that chemical substances be registered and assessed, placing the burden of proof for chemical safety on manufacturers and importers [25]. Similarly, the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) adopts a risk-based regulatory approach [25].

Socioeconomic Burden of CEC Exposure

The economic implications of unregulated CECs are substantial:

- PFAS management is estimated to have a social cost as high as EUR 16 trillion - approximately 4000 times the net annual profit of the global PFAS industry (around USD 4 billion) [25]

- Antibiotic resistance, exacerbated by pharmaceutical CECs, directly and indirectly caused approximately 5 million deaths in 2019, potentially rising to 10 million deaths annually by 2050 [25]

- By 2050, antibiotic resistance could result in a global GDP loss of USD 3.4 trillion annually and push an additional 24 million people into extreme poverty [25]

Epidemiological evidence increasingly links CEC exposure to various chronic diseases, including immune dysfunction, neurodevelopmental disorders, reproductive impairment, and metabolic diseases. The distinctive challenges of CECs—including environmental persistence, ubiquitous distribution, low-dose effects, and complex mixture interactions—necessitate novel approaches to environmental health protection.

Future research priorities should include:

- Advanced monitoring techniques utilizing sensor technology, remote sensing, and citizen science for better exposure assessment

- High-throughput toxicology approaches to efficiently screen priority CECs

- Biomarker development for early detection of exposure and biological effects

- Mixture toxicology research to understand combined effects

- Susceptibility research identifying vulnerable populations and life stages

Addressing the challenges posed by CECs requires transdisciplinary collaboration across scientific fields, regulatory agencies, and public health organizations. Only through integrated approaches can we effectively characterize risks, develop protective policies, and implement mitigation strategies that safeguard both ecosystem and human health across the lifespan.

This whitepaper provides a technical examination of three critical classes of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in aquatic environments: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), pharmaceuticals, and cyanotoxins. With the escalating threat of water pollution globally, understanding the environmental exposure pathways and toxicological effects of these contaminants is paramount for environmental and public health protection. This guide synthesizes current research on the sources, environmental fate, and ecological impacts of these compounds, with a particular emphasis on advanced analytical methodologies, experimental protocols for toxicity assessment, and emerging bioremediation strategies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document serves as a comprehensive resource for navigating the complexities of CEC research and contributes to the broader thesis on predicting and mitigating the environmental effects of emerging contaminants.

Contaminants of emerging concern represent a diverse group of chemical compounds that are now being detected in the environment with potential consequences for ecosystem and human health, but are not yet consistently regulated. Their persistence, bioaccumulative potential, and often unknown chronic toxicity pose significant challenges for risk assessment and water quality management.

The aquatic environment serves as a primary sink for these pollutants, which enter water bodies through multiple pathways including wastewater effluent, agricultural runoff, and industrial discharges [33] [34]. Among CECs, PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and cyanotoxins have garnered significant scientific and regulatory attention due to their unique properties and widespread occurrence. PFAS are characterized by their extreme persistence, earning the nickname "forever chemicals," with thousands of variants existing in commercial use [33] [34]. Pharmaceuticals, designed to be biologically active, can disrupt endocrine and metabolic functions in non-target aquatic organisms at low concentrations. Cyanotoxins, produced during harmful algal blooms (HABs) fueled by eutrophication and climate change, represent natural toxicants with increasing global distribution [35] [36].

Understanding the interplay between these contaminants adds another layer of complexity. Recent research indicates that co-occurring contaminants can interact, potentially altering their toxicity and environmental behavior. For instance, certain PFAS have been shown to influence cyanobacterial blooms and metabolic pathways, demonstrating unanticipated ecological interactions [37]. This guide presents detailed case studies on each contaminant class, providing structured data, experimental protocols, and visual tools to advance research in this critical field.

Contaminant Profiles and Environmental Exposure Pathways

PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances)

PFAS are a group of over 4,700 man-made chemicals characterized by fully fluorinated carbon chains that confer exceptional stability and resistance to degradation [34]. Their amphipathic nature, with both hydrophobic and lipophobic properties, makes them highly effective in numerous industrial and consumer applications.

Primary Sources and Exposure Pathways: PFAS enter aquatic systems through multiple vectors, including firefighting foam (AFFF), industrial discharges from manufacturing facilities, landfill leachate, and wastewater treatment plant effluent [33]. Due to their high mobility and persistence, they contaminate groundwater and surface water, leading to human exposure primarily through contaminated drinking water and food, particularly fish from contaminated waters [33] [34].

Key Compounds: The most extensively studied PFAS compounds are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), which are now considered "legacy" PFAS. While their production has been phased out in many regions, they remain environmentally persistent and have been largely replaced by shorter-chain alternatives (e.g., GenX) with similar concerns regarding mobility and persistence [33] [34].

Table 1: Characteristic Profiles of Major PFAS Compounds

| PFAS Compound | Chain Length | Primary Use | Key Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA | C8 | Non-stick coatings, waterproofing | Persistent, bioaccumulative |

| PFOS | C8 | Fire-fighting foam, stain repellents | Persistent, bioaccumulative |

| PFBS | C4 | Replacement for PFOS | Highly mobile in water |

| GenX | C6 | Industrial processing | Persistent, mobile |

Cyanotoxins

Cyanotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by various species of cyanobacteria during Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs). Their occurrence is increasing globally due to eutrophication and climate change, posing significant threats to aquatic ecosystems and human health [35] [36].

Primary Sources and Exposure Pathways: Cyanotoxins originate from bloom-forming cyanobacteria such as Microcystis, Dolichospermum, and Planktothrix in eutrophic freshwater systems [35] [36]. Human exposure occurs primarily through recreational water contact, consumption of contaminated drinking water or fish, and accidental ingestion of water during swimming.

Key Toxin Classes: The major cyanotoxin classes include:

- Microcystins (MCs): Hepatotoxic cyclic peptides with over 200 variants (e.g., MC-LR, MC-RR, MC-YR); MC-LR is the most toxic and well-studied [35].

- Cylindrospermopsins (CYN): Alkaloid hepatotoxins that inhibit protein synthesis.

- Anatoxins (ATXs): Alkaloid neurotoxins, with ATX-a being the most significant congener [35].

Table 2: Major Cyanotoxin Classes and Their Characteristics

| Cyanotoxin Class | Toxic Mechanism | Primary Producers | Key Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcystins | Hepatotoxicity, protein phosphatase inhibition | Microcystis, Planktothrix | MC-LR, MC-RR, MC-YR |

| Cylindrospermopsins | Hepatotoxicity, protein synthesis inhibition | Cylindrospermopsis, Dolichospermum | CYN |

| Anatoxins | Neurotoxicity, acetylcholine mimicry | Dolichospermum, Tychonema | ATX-a, dhATX |

Environmental Exposure Framework

The transport and fate of CECs in aquatic systems follow complex pathways influenced by chemical properties, environmental conditions, and anthropogenic factors. Exposure pathways begin with contaminant release and involve transport through multiple environmental media before reaching human and ecological receptors [38]. Critical exposure routes for aquatic contaminants include:

- Ingestion: Consumption of contaminated drinking water or aquatic food sources

- Dermal Contact: Direct skin exposure during recreational activities

- Inhalation: Aerosolized contaminants from water surfaces

The diagram below illustrates the complex pathways and interrelationships between different environmental compartments for CECs.

Quantitative Data on Occurrence and Risk

Cyanotoxin Occurrence in Six Chinese Lakes

A 2022 study investigating six eutrophic lakes across China revealed widespread cyanotoxin contamination with significant spatial heterogeneity linked to environmental conditions [35].

Table 3: Cyanotoxin Occurrence and Environmental Factors in Six Chinese Lakes (Summer 2022)

| Lake Name | Region | MC Concentration (μg/L) | Dominant MC Variant | Key Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taihu Lake | Eastern Plain | 0.45 (avg) | MC-LR | High water temperature (33.01°C), high TP |

| Dianchi Lake | Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau | 0.92 (avg) | MC-RR | High NH₄-N, high Chl-a |

| Chaohu Lake | Eastern Plain | 0.21 (avg) | MC-LR | Moderate TN, TP |

| Hulun Lake | Inner Mongolia | 0.08 (avg) | MC-LR | Low water temperature (22.41°C), high DO, high TN |

| Xingyun Lake | Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau | 0.35 (avg) | MC-RR | High pH, high TP |

| Wuliangsuhai Lake | Inner Mongolia | 0.11 (avg) | MC-LR | Grass-algae lake type, moderate nutrients |

The study demonstrated that microcystins were prevalent across all surveyed lakes, with concentrations varying significantly based on geographic location and hydrological conditions [35]. Total phosphorus (TP) and water temperature (WT) were identified as critical factors influencing cyanotoxin production, with warmer temperatures and higher nutrient levels generally correlating with increased MC concentrations [35].

PFAS and Cyanotoxin Risk Assessment Values

Regulatory agencies and scientific studies have established various guideline values for CECs based on toxicological assessments.

Table 4: Human Health Risk Assessment Values for Selected Contaminants

| Contaminant | Health Effect | Risk Value | Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA | Kidney/testicular cancer | -- | EPA: Increased risk evidence [33] [39] |

| PFOS | Increased cholesterol | -- | ATSDR: Consistent association [39] |

| MC-LR | Hepatotoxicity | 1.0 μg/L (WHO drinking water guideline) | WHO provisional value [36] |

| PFOS | Reduced antibody response | -- | ATSDR: Epidemiological evidence [39] |

| PFOA | Pregnancy-induced hypertension | -- | CDC/ATSDR: Association observed [39] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing PFAS Effects on Cyanobacterial Metabolomics

This protocol, adapted from Liao et al. (2025), examines the impact of single PFOS versus mixed PFAS exposure on Microcystis aeruginosa using metabolomic profiling [37].

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key stages of the experimental workflow for assessing PFAS effects on cyanobacteria.

Detailed Methodology

Cyanobacteria Culture and Maintenance:

- Obtain Microcystis aeruginosa from a certified culture collection (e.g., Freshwater Algae Culture Collection at the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

- Maintain in BG11 medium at pH 7.4, 25°C, with 2200 lux light intensity under a 12:12 light:dark cycle.

- Use cells in the exponential growth phase for all experiments to ensure metabolic consistency.

Exposure Experiment Design:

- Prepare three exposure scenarios:

- Control: BG11 medium only

- PFOS exposure: BG11 with perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (0.5 mg/L)

- PFAS mixture: BG11 with multiple PFAS compounds at environmentally relevant concentrations

- Culture algae in continuous or batch systems with continuous bubbling of air with 5% CO₂ (v/v) to ensure non-limiting carbon supply.

- Maintain constant light intensity at 150 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ using full-spectrum LED lamps.

- Monitor pH daily using a calibrated pH meter (e.g., HI 9124 pH meter).

- Prepare three exposure scenarios:

Physiological Parameter Assessments:

- Algal Density: Measure daily using optical density at 680 nm or cell counting with a hemocytometer.

- Chlorophyll-a Content: Extract with methanol and measure fluorescence or spectrophotometrically.

- Photochemical Efficiency (Fv/Fm): Determine using a pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometer after dark adaptation.

- Oxidative Stress Markers: Measure malondialdehyde (MDA) content as a lipid peroxidation indicator via thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay.

- Microcystin Production: Quantify intracellular and extracellular microcystins using ELISA or LC-MS/MS.

Metabolomic Profiling:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest cells by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. Quench metabolism immediately using liquid nitrogen.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use 80% methanol with repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Concentrate extracts using a speed vacuum concentrator.

- LC-MS Analysis: Perform untargeted metabolomics using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS with both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Data Processing: Use software (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) for peak picking, alignment, and annotation against databases (e.g., HMDB, KEGG).

- Pathway Analysis: Identify significantly altered metabolic pathways using pathway enrichment analysis and pathway impact values.

Key Findings from Original Study

The study revealed that PFOS exposure inhibited algal growth and photosynthetic capacity, accompanied by elevated peroxidation levels and increased microcystin synthesis. In contrast, combined PFAS exposure enhanced both algal growth and photosynthetic efficiency. Metabolic profiling indicated that PFOS's inhibitory effects were potentially due to the disruption of purine/pyrimidine metabolism and the TCA cycle, while mixed PFAS stimulated glutathione metabolism and fatty acid biosynthesis, suggesting a hormetic effect [37].

Protocol: Cyanotoxin Monitoring in Lakes

This protocol, based on Yang et al. (2025), details comprehensive sampling and analysis of multiple cyanotoxins across diverse lake systems [35].

Field Sampling Design:

- Select sampling sites to represent different hydrological regions and potential nutrient gradients.

- Collect surface water and sediment samples during peak bloom season (typically summer).

- Record in-situ environmental parameters including water temperature (WT), dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, and chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) at each sampling point.

Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Collect water samples in pre-cleaned amber glass bottles.

- Gather sediment samples using a grab sampler or core sampler.

- Filter water samples through GF/F filters (0.7 μm pore size) immediately after collection.

- Freeze all samples at -20°C until analysis to preserve analyte integrity.

Analytical Methods:

- Nutrient Analysis: Measure total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and phosphate (PO₄-P) using standard colorimetric methods (e.g., automated flow injection analysis).

- Cyanotoxin Extraction:

- Water samples: Solid-phase extraction (SPE) using hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) cartridges.

- Sediment samples: Accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) or ultrasonic extraction with methanol/water mixtures.

- Cyanotoxin Quantification:

- Use liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for multiple cyanotoxins.

- Analyze for major microcystin variants (MC-LR, MC-RR, MC-YR), cylindrospermopsin (CYN), and anatoxins (ATX-a).

- Include quality control samples (blanks, spikes, duplicates) in each batch.

Risk Assessment:

- Calculate risk quotients (RQs) by comparing measured concentrations to toxicity reference values.

- Evaluate spatial patterns in toxin distribution and correlation with environmental parameters using statistical analysis (e.g., principal component analysis, redundancy analysis).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for CEC Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| BG11 Medium | Cyanobacteria culture and maintenance | Standard recipe with nitrate, phosphate, and micronutrients [37] |

| HLB Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Concentration of cyanotoxins and PFAS from water samples | 200 mg, 6 cc cartridge volume [35] |

| UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS System | Untargeted metabolomic profiling | High-resolution mass accuracy (<5 ppm) [37] |

| LC-MS/MS System | Targeted quantification of cyanotoxins and PFAS | Triple quadrupole with ESI source [35] |

| PAM Fluorometer | Measurement of photosynthetic efficiency | Pulse-amplitude modulation technology [37] |

| Certified Reference Standards | Quantification of target analytes | PFOA, PFOS, MC-LR, CYN, ATX-a [35] [37] |

The complex interplay between PFAS, pharmaceuticals, and cyanotoxins in aquatic systems presents significant challenges for researchers and risk assessors. This technical guide has synthesized current knowledge on the environmental exposure pathways, ecological effects, and advanced methodologies for studying these contaminants of emerging concern. The structured data, experimental protocols, and visualization tools provided herein offer a foundation for advancing research in this critical field. As climate change and anthropogenic activities continue to influence contaminant distribution and transformation, interdisciplinary approaches integrating chemistry, toxicology, and systems biology will be essential for protecting aquatic ecosystem health and human populations dependent on safe water resources. Future research directions should prioritize understanding mixture toxicity, developing advanced remediation strategies, and refining risk assessment frameworks to address the evolving landscape of aquatic contamination.

Advanced Detection and Monitoring: From Laboratory Analysis to Real-Time Sensing

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Chromatography for Trace-Level Analysis

The expanding anthropogenic environmental chemical space, driven by industrial activity and diverse consumer products, has made the comprehensive characterization of environmental samples a significant analytical challenge [40]. Contaminants of emerging concern (CECs), including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, pesticides, and industrial chemicals, represent a growing threat to ecosystems and human health due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and often-unknown toxicological profiles [41]. Addressing these challenges necessitates advanced analytical tools capable of detecting and quantifying trace levels of these compounds in complex environmental matrices such as water, soil, and air [41].

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) coupled with chromatography has emerged as a powerful tool for tackling this challenge. Its high sensitivity, specificity, and versatility facilitate real-time detection of volatile organic compounds, comprehensive non-targeted screening of unknown contaminants, and accurate quantification in diverse matrices [41]. This technical guide explores the core methodologies, workflows, and applications of these techniques within environmental exposure and effects research, providing researchers with detailed protocols and frameworks for implementing these advanced analytical strategies.

Analytical Techniques and Instrumentation

Chromatographic Separation and Mass Spectrometric Detection

The analysis of trace-level organic micropollutants (OMPs) requires sophisticated separation and detection strategies. Considering the diverse physicochemical characteristics of OMPs, the coupling of both liquid (LC) and gas chromatography (GC) to high-resolution mass spectrometry is often mandatory for comprehensive screening [42].