Ensuring Model Generalizability: A Comprehensive Guide to External Dataset Validation in Environmental Machine Learning

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists on achieving robust model generalizability through rigorous external validation in environmental machine learning applications.

Ensuring Model Generalizability: A Comprehensive Guide to External Dataset Validation in Environmental Machine Learning

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists on achieving robust model generalizability through rigorous external validation in environmental machine learning applications. It explores the foundational challenges of data heterogeneity and dataset shift, outlines practical methodologies for model adaptation and transfer learning, and presents strategies for troubleshooting performance degradation. Through comparative analysis of validation frameworks and real-world case studies from clinical and environmental domains, we establish best practices for assessing model performance across diverse, unseen datasets. The insights are tailored to inform the development of reliable, deployable ML models in critical fields like biomedical research and drug development.

Why Models Fail: The Critical Importance of External Validation for Generalizability

In environmental machine learning (ML) research, a model's true value is not determined by its performance on its training data, but by its generalizability—its ability to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data from different locations or time periods. Validation is the rigorous process of assessing this generalizability, and it is typically structured in three main tiers: internal, temporal, and external. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these validation types, underpinned by experimental data and methodologies relevant to environmental science.

The Three Pillars of Model Validation

The following table defines the core validation types and their role in assessing model generalizability.

| Validation Type | Core Question | Validation Strategy | Role in Assessing Generalizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Has the model learned generalizable patterns from its development data, or has it simply memorized it (overfitting)? | Techniques like bootstrapping or cross-validation are applied to the same dataset used for model development [1] [2]. | Serves as the first sanity check. It assesses reproducibility and optimism (overfitting) but cannot prove performance on data from new sources [3]. |

| Temporal Validation | Does the model maintain its performance when applied to data from a future time period? | The model is trained on data from one time period and validated on data collected from a later, distinct period [3]. | Evaluates stability over time, crucial for environmental models where underlying conditions (e.g., climate, land use) may shift [3]. |

| External Validation | How well does the model perform on data from a completely new location or population? | The model is validated on data from a different geographic region, institution, or population than was used for development [1] [3]. | Provides the strongest evidence of transportability and real-world utility. It directly tests whether the model can be generalized across spatial or institutional boundaries [3]. |

A model is never truly "validated" in a final sense. Rather, these processes create a body of evidence about its performance across different settings and times [3]. Performance will naturally vary—a phenomenon known as heterogeneity—due to differences in patient populations, measurement procedures, and changes over time [3].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

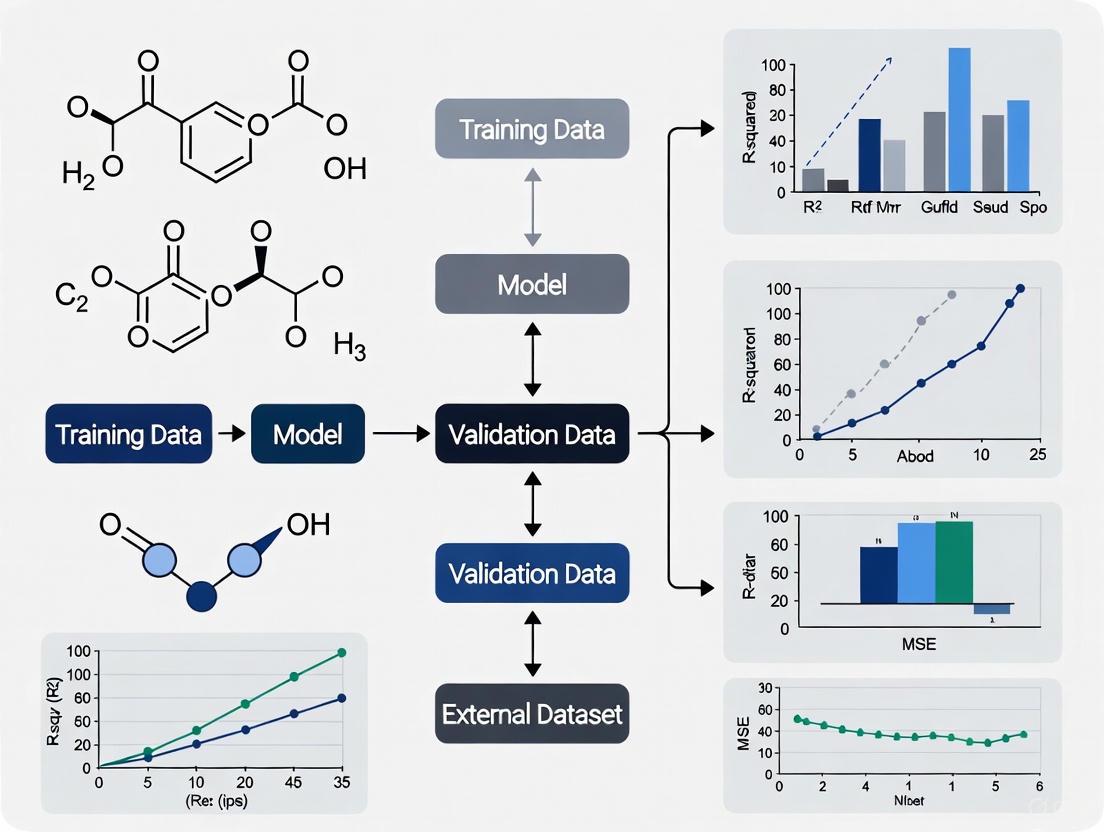

To ensure rigorous and replicable results, specific experimental protocols must be followed for each validation type. The workflows for internal and external validation are summarized in the diagrams below.

Internal Validation via Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is the preferred method for internal validation, as it provides a robust assessment of model optimism without reducing the effective sample size for training [1].

Key Steps:

- Bootstrap Sampling: Generate a large number (e.g., 200) of bootstrap samples from the original development dataset by random drawing with replacement. Each sample is the same size as the original dataset [1].

- Model Training & Testing: For each bootstrap sample, train the model and then test its performance on both the bootstrap sample and the original dataset [1].

- Optimism Calculation: The difference in performance (e.g., in C-statistic or calibration) between the bootstrap sample and the original dataset is the "optimism" for that iteration [1].

- Performance Correction: The average optimism across all bootstrap iterations is subtracted from the apparent performance of the model developed on the original dataset, yielding an optimism-corrected estimate [1].

External & Temporal Validation

External and temporal validation follow a similar high-level protocol, distinguished primarily by the nature of the data split.

Key Steps:

- Non-Random Data Split: The dataset is partitioned based on time (for temporal validation) or location/study (for geographic external validation). This is distinct from a random holdout and is essential for testing generalizability [1] [3].

- Model Training: The model is trained exclusively on the development set (e.g., data from earlier years or Location A).

- Model Validation: The final model is applied to the held-out validation set to estimate its performance on new data.

- Heterogeneity Analysis: For external validations across multiple locations, performance metrics (e.g., C-statistic, calibration slope) should be calculated per site. The variation in these metrics is quantified to understand the model's transportability. A useful approach is to calculate 95% prediction intervals for performance, indicating the expected range of performance in a new setting [3].

Comparative Experimental Data from Research

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from validation studies, illustrating how model performance can vary across different contexts.

| Model / Application Domain | Internal Validation Performance | External/Temporal Validation Performance | Key Findings & Observed Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Model for Ovarian Cancer [3] | Not specified in summary. | C-statistics varied between 0.90–0.95 in oncology centers vs. 0.85–0.93 in other centers. | Model discrimination was consistently higher in specialized oncology centers compared to other clinical settings, highlighting the impact of patient population differences. |

| Wang Model for COVID-19 Mortality [3] | Not specified in summary. | Pooled C-statistic: 0.77. Calibration varied widely (O:E ratio: 0.65, Calibration slope: 0.50). | A 95% prediction interval for the C-statistic in a new cluster was 0.63–0.87. This wide interval underscores significant performance heterogeneity across different international cohorts. |

| 104 Cardiovascular Disease Models [3] | Median C-statistic in development: 0.76. | Median C-statistic at external validation: 0.64. After adjustment for patient characteristics: 0.68. | About one-third of the performance drop was attributed to more homogeneous patient samples in the validation data (clinical trials vs. observational data). |

| HV Insulator Contamination Classifier [4] | Models (Decision Trees, Neural Networks) optimized and evaluated on an experimental dataset. | Accuracies consistently exceeded 98% on a temporally and environmentally varied experimental dataset. | The study simulated real-world variation by including critical parameters like temperature and humidity in its dataset, creating a robust test of generalizability. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods & Reagents

Success in environmental ML validation relies on a toolkit of statistical techniques and methodological considerations.

| Tool / Technique | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Environmental ML |

|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap Resampling [1] | Quantifies model optimism and corrects for overfitting during internal validation without needing a dedicated hold-out test set. | Crucial for providing a realistic baseline performance estimate before committing resources to costly external validation studies. |

| Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation [2] | A robust internal validation method for smaller datasets; ensures each fold preserves the distribution of the target variable. | Useful for imbalanced environmental classification tasks (e.g., predicting rare pollution events). |

| Time-Series Split (e.g., TimeSeriesSplit) [2] | Prevents data leakage in temporal validation by ensuring the training set chronologically precedes the validation set. | Essential for modeling time-dependent environmental phenomena like pollutant concentration trends, river flow, or deforestation. |

| Spatial Blocking | Extends the principle of temporal splitting to space; data is split into spatial blocks (e.g., by watershed or region) to test geographic generalizability. | Addresses spatial autocorrelation, a common challenge where samples from nearby locations are not independent [5]. |

| Bayesian Optimization [4] | An efficient algorithm for hyperparameter tuning that builds a probabilistic model of the function mapping hyperparameters to model performance. | Used to optimally configure complex models (e.g., neural networks) while mitigating overfitting, as demonstrated in the HVI contamination study [4]. |

| Calibration Plots & Metrics | Assess the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. Key metrics include the calibration slope and intercept. | Poor calibration is the "Achilles heel" of applied models; a model can have good discrimination but dangerous miscalibration [3]. |

In conclusion, robust validation is a multi-faceted process. Internal validation checks for overfitting, temporal validation assesses stability, and external validation is the ultimate test of a model's utility in new environments. For environmental ML researchers, embracing this hierarchy and the accompanying heterogeneity is key to developing models that are not only statistically sound but also genuinely useful for decision-making in a complex and changing world.

In the pursuit of developing robust machine learning (ML) models for healthcare, researchers face a fundamental obstacle: the pervasive nature of data heterogeneity. Electronic Health Records (EHRs) contain multi-scale data from heterogeneous domains collected at irregular time intervals and with varying frequencies, presenting significant analytical challenges [6]. This heterogeneity manifests across multiple dimensions—institutional protocols, demographic factors, and missing data patterns—creating substantial barriers to model generalizability and external validation. The performance of ML systems is profoundly influenced by how they account for this intrinsic diversity, with traditional algorithms designed to optimize average performance often failing to maintain reliability across different subpopulations and healthcare settings [7].

The implications extend beyond technical performance to tangible health equity concerns. Studies have demonstrated that data for underserved populations may be less informative, partly due to more fragmented care, which can be viewed as a type of missing data problem [6]. When models are trained on data where certain groups are prone to have less complete information, they may exhibit unfair performance for these populations, potentially exacerbating existing health disparities [6] [7]. This creates an urgent need for systematic approaches to quantify, understand, and mitigate the perils of data heterogeneity throughout the ML pipeline.

Conceptual Framework: Understanding Data Heterogeneity

Defining Levels of EHR Data Complexity

The terminology for delineating EHR data complexity remains inconsistently applied across institutions. To standardize discourse, research literature has proposed three distinct levels of information complexity in EHR data [6]:

- Level 0 Data: Raw data residing in EHR systems without any pre-processing steps, lacking structure or standardization (e.g., narrative text, non-codified fields).

- Level 1 Data: Data after limited pre-processing including harmonization, integration, and curation, typically appearing as sequences of events with heterogeneous structure (e.g., templated text, codified prescriptions and diagnoses mapped to standard terminologies).

- Level 2 Data: EHR data in matrix form with a priori selected and well-defined features extracted through chart reviews or other mechanisms, representing significant information loss from Level 1 but being amenable to classical statistical and ML methods.

The transformation from Level 1 to Level 2 data typically involves substantial information loss, as non-conformant or non-computable data becomes "missing" or lost during feature engineering [6]. For machine learning models to be effectively adopted in clinical settings, it is highly advantageous to build models that can use Level 1 data directly, though this presents significant technical challenges.

Typology of Heterogeneity in Healthcare

Data heterogeneity in medical research encompasses multiple dimensions that collectively impact model generalizability:

- Demographic Heterogeneity: Refers to variation in vital parameters such as birth and death rates that is unrelated to age, stage, sex, or environmental fluctuations [8]. This inherent variability affects population dynamics and can significantly influence longitudinal health outcomes.

- Hospital Protocol Heterogeneity: Differences in data collection practices, measurement frequencies, documentation standards, and technical implementations across healthcare institutions [6] [9]. This includes variability in how patients are connected to monitoring equipment, sampling frequencies for laboratory tests, and institutional priorities in data capture.

- Missing Data Heterogeneity: Systematic patterns in data absence that vary across patient subpopulations and clinical scenarios [6] [10]. This includes not only completely missing observations but also misaligned unevenly sampled time series that create the appearance of missingness through analytical choices.

The following diagram illustrates the complex relationships between these heterogeneity types and their impact on ML model performance:

Data Heterogeneity Impact Pathway: This diagram illustrates how diverse data sources generate different types of heterogeneity that collectively impact machine learning model performance and equity.

Experimental Comparisons: Frameworks for Assessing Heterogeneity

Knowledge Graph Framework for Realistic Missing Data Simulation

Experimental Protocol: A novel framework was developed to simulate realistic missing data scenarios in EHRs that incorporates medical knowledge graphs to capture dependencies between medical events [6]. This approach creates more realistic missing data compared to simple random event removal.

Methodology:

- Define three levels of EHR data complexity (Level 0, 1, and 2)

- Construct medical knowledge graphs representing dependencies between diagnoses, medications, and laboratory tests

- Simulate missingness patterns that follow medical logic rather than random removal

- Assess impact on disease prediction models in intensive care unit settings

- Compare model performance across patient subgroups with different access to healthcare

Key Findings: The impact of missing data on disease prediction models was stronger when using the knowledge graph framework to introduce realistic missing values compared to random event removal. Models exhibited significantly worse performance for groups that tend to have less access to healthcare or seek less healthcare, particularly patients of lower socioeconomic status and patients of color [6].

Table 1: Performance Impact of Realistic vs. Random Missing Data Simulation

| Patient Subgroup | Random Missing Data (AUC) | Knowledge Graph Simulation (AUC) | Performance Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Healthcare Access | 0.84 | 0.81 | 3.6% |

| Low Healthcare Access | 0.79 | 0.72 | 8.9% |

| Elderly Patients | 0.82 | 0.78 | 4.9% |

| Minority Patients | 0.77 | 0.70 | 9.1% |

Dynamic Data Quality Assessment Framework

Experimental Protocol: The AIDAVA (Artificial Intelligence-Powered Data Curation and Validation) framework introduces dynamic, life cycle-based validation of health data using knowledge graph technologies and SHACL (Shapes Constraint Language)-based rules [9].

Methodology:

- Transform raw data into Source Knowledge Graphs (SKGs) aligned with a reference ontology

- Integrate multiple SKGs into a unified Personal Health Knowledge Graph (PHKG)

- Apply SHACL validation rules iteratively during integration process

- Introduce structured noise including missing values and logical inconsistencies to MIMIC-III dataset

- Assess data quality under varying noise levels and integration orders

Key Findings: The framework effectively detected completeness and consistency issues across all scenarios, with domain-specific attributes (e.g., diagnoses and procedures) being more sensitive to integration order and data gaps. Completeness was shown to directly influence the interpretability of consistency scores [9].

Table 2: Data Quality Framework Comparison

| Framework Feature | Traditional Static Approach | AIDAVA Dynamic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Timing | Single point in time | Continuous throughout data life cycle |

| Rule Enforcement | Batch processing after integration | Iterative during integration process |

| Heterogeneity Handling | Limited to predefined structures | Adapts to evolving data pipelines |

| Scalability | Challenging with complex data | Designed for heterogeneous sources |

| Missing Data Detection | Basic pattern recognition | Context-aware classification |

Classification-Based Missing Data Management

Experimental Protocol: A statistical classifier followed by fuzzy modeling was developed to accurately determine which missing data should be imputed and which should not [10].

Methodology:

- Create test beds with missing data ranging from 10-50%

- Align misaligned unevenly sampled data using gridding and templating techniques

- Apply statistical classification to differentiate absent values resulting from low sampling frequencies from true missingness

- Use fuzzy modeling to classify missing data as recoverable or not-recoverable

- Compare modeling performance parameters including accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity

Key Findings: This approach improved modeling performance by 11% in classification accuracy, 13% in sensitivity, and 10% in specificity, including AUC improvement of up to 13% compared to conventional imputation or deletion methods [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Solutions for Heterogeneity Challenges

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Knowledge Graphs | Captures dependencies between medical events | Realistic missing data simulation [6] |

| SHACL (Shapes Constraint Language) | Defines and validates constraints on knowledge graphs | Dynamic data quality assessment [9] |

| Subtype and Stage Inference (SuStaIn) Algorithm | Identifies distinct disease progression patterns | Heterogeneity modeling in Alzheimer's disease [11] |

| MIMIC-III Dataset | Provides critical care data for simulation studies | Framework validation and testing [9] |

| AIDAVA Reference Ontology | Enables semantic interoperability across sources | Standardizing heterogeneous health data [9] |

| LASSO Regression | Selects relevant variables from high-dimensional data | Feature selection in environmental exposure studies [12] |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) | Handles complex non-linear relationships | Predictive modeling with heterogeneous features [12] |

Analytical Approaches: Managing Missing Data Patterns

Categorizing Missing Data Mechanisms

The handling of missing data in medical databases requires careful classification of the underlying mechanisms [6] [10]:

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR): The probability of data being missing is unrelated to both observed and unobserved variables. Example: A lab technician forgetting to input data points regardless of patient attributes.

- Missing at Random (MAR): Missingness depends on observed data but not on unobserved values. Example: A patient's recorded demographic characteristics are associated with seeking less healthcare and therefore having sparser medical records.

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): The probability of missingness depends on the unobserved values themselves. Example: A patient's unobserved underlying condition (e.g., undiagnosed depression) prevents them from traveling to see a healthcare provider.

The following workflow illustrates a sophisticated approach to classifying and managing different types of missing data in clinical datasets:

Missing Data Management Workflow: This diagram outlines a comprehensive approach to classifying and handling different types of missing data in clinical datasets, incorporating statistical classification and fuzzy modeling.

Demographic Heterogeneity in Population Dynamics

Demographic heterogeneity—referring to among-individual variation in vital parameters such as birth and death rates that is unrelated to age, stage, sex, or environmental fluctuations—has been shown to significantly impact population dynamics [8]. This form of heterogeneity is prevalent in ecological populations and affects both demographic stochasticity in small populations and growth rates in density-independent populations through "cohort selection," where the most frail individuals die out first, lowering the cohort's average mortality as it ages [8].

In healthcare contexts, this translates to understanding how inherent variability in patient populations affects disease progression and treatment outcomes. Research in Alzheimer's disease, for instance, has identified distinct atrophy subtypes (limbic-predominant and hippocampal-sparing) with different progression patterns and cognitive profiles [11]. These heterogeneity patterns have significant implications for clinical trial design and patient management strategies.

Implications for Model Generalizability and External Validation

Challenges in Cross-Institutional Validation

The heterogeneity of hospital protocols and data collection practices creates substantial barriers to external validation of ML models. Studies have demonstrated that models achieving excellent performance within a single healthcare system often experience significant degradation when applied to new institutions [6] [9]. This performance drop stems from systematic differences in how data is collected, coded, and managed across settings rather than true differences in clinical relationships.

The AIDAVA framework addresses this challenge through semantic standardization using reference ontologies that align Personal Health Knowledge Graphs with established standards such as FHIR, SNOMED CT, and CDISC [9]. This approach enables more consistent data representation across institutions, facilitating more reliable external validation.

Environmental Exposure Modeling in Heterogeneous Data

Machine learning applications in environmental health must contend with multiple dimensions of heterogeneity. A review of 44 articles implementing ML and data mining methods to understand environmental exposures in diabetes etiology found that specific external exposures were the most commonly studied, and supervised models were the most frequently used methods [13].

Well-established specific external exposures of low physical activity, high cholesterol, and high triglycerides were predictive of general diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and prediabetes, while novel metabolic and gut microbiome biomarkers were implicated in type 1 diabetes [13]. However, the use of ML to elucidate environmental triggers was largely limited to well-established risk factors identified using easily explainable and interpretable models, highlighting the need for more sophisticated heterogeneity-aware approaches.

The perils of data heterogeneity in healthcare—manifesting through variable hospital protocols, demographic diversity, and complex missing data patterns—represent both a challenge and an opportunity for the development of generalizable ML models. Traditional approaches that optimize for average performance inevitably fail to maintain reliability across diverse populations and clinical settings, potentially exacerbating health disparities [6] [7].

A new paradigm of heterogeneity-aware machine learning is emerging that systematically integrates considerations of data diversity throughout the entire ML pipeline—from data collection and model training to evaluation and deployment [7]. This approach, incorporating frameworks such as knowledge graph-based missing data simulation [6], dynamic quality assessment [9], and sophisticated missing data classification [10], offers a path toward more robust, equitable, and clinically useful predictive models.

The implementation of heterogeneity-specific endpoints and validation procedures has the potential to increase the statistical power of clinical trials and enhance the real-world performance of algorithms targeting complex conditions with diverse manifestation patterns, such as Alzheimer's disease [11] and diabetes [13]. As healthcare continues to generate increasingly complex and multidimensional data, the ability to explicitly account for and model heterogeneity will become essential for trustworthy clinical machine learning.

In the evolving landscape of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), the ability of a model to perform reliably on data outside its original training set—a property known as model generalizability—is paramount for real-world efficacy. Dataset shift, the phenomenon where the joint distribution of inputs and outputs differs between the training and deployment environments, presents a fundamental challenge to this generalizability [14]. Research in environmental ML and external dataset validation consistently identifies dataset shift as a primary cause of performance degradation in production systems [15] [16]. Within this broad framework, two specific types of shift are critically important: covariate drift and concept drift. While both lead to a decline in model performance, they stem from distinct statistical changes and require different detection and mitigation strategies [15] [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these drifts, detailing their theoretical foundations, detection methodologies, and management protocols, with a focus on applications in scientific domains such as drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Definitions

At its core, a supervised machine learning model is trained to learn the conditional distribution ( P(Y|X) ), where ( X ) represents the input features and ( Y ) is the target variable. Dataset shift occurs when the real-world data encountered during deployment violates the assumption that the data is drawn from the same distribution as the training data [14]. The table below delineates the key characteristics of covariate drift and concept drift.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Covariate Drift and Concept Drift

| Aspect | Covariate Drift (Data Drift) | Concept Drift (Concept Shift) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Change in the distribution of input features ( P(X) ) [14] [18]. | Change in the relationship between inputs and outputs ( P(Y | X) ) [15] [14]. | ||

| Mathematical Formulation | ( P{train}(X) \neq P{live}(X) ), but ( P(Y | X) ) is stable [14]. | ( P_{train}(Y | X) \neq P_{live}(Y | X) ), even if ( P(X) ) is stable [15] [14]. |

| Primary Cause | Internal data generation factors or shifting population demographics [15] [18]. | External, real-world events or evolving contextual definitions [15] [19]. | |||

| Impact on Model | Model encounters unfamiliar feature spaces, leading to inaccurate predictions [18]. | Learned mapping function becomes outdated and incorrect, rendering predictions invalid [15]. | |||

| Example | A model trained on clinical data from 20-30 year-olds performs poorly on data from 50+ year-olds [18]. | The clinical definition of a disease subtype evolves, making a diagnostic model's learned criteria incorrect [15]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical difference between a stable environment and these two primary drift types, based on their mathematical definitions.

Diagram 1: Logical flow of model performance under stable conditions, covariate drift, and concept drift.

Experimental Protocols for Drift Detection

Detecting dataset shift requires robust statistical tests and monitoring frameworks. The protocols below are widely used for external dataset validation and can be integrated into continuous MLOps pipelines.

Detecting Covariate Drift

Covariate drift detection focuses on identifying statistical differences in the feature distributions between a reference (training) dataset and a current (production) dataset [17] [20].

Protocol 1: Population Stability Index (PSI) and Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test The PSI is a robust metric for monitoring shifts in the distribution of a feature over time, while the K-S test is a non-parametric hypothesis test [16] [20].

- Data Preparation: For a given feature, define the reference dataset (e.g., training data) and the current dataset (e.g., recent production data). For continuous features, create bins based on the percentile breaks (e.g., 10 buckets using 10th, 20th, ..., 100th percentiles) of the reference distribution [20].

- Percentage Calculation: Calculate the percentage of observations (( \%{ref} ) and ( \%{curr} )) that fall into each bin for both the reference and current datasets.

- PSI Calculation: Compute the PSI for each feature using the formula: ( PSI = \sum (\%{curr} - \%{ref}) \cdot \ln(\frac{\%{curr}}{\%{ref}}) ) [20].

- Interpretation:

- K-S Test Implementation: As a complementary method, use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to compare the two continuous distributions. A resulting p-value below a significance level (e.g., 0.05) rejects the null hypothesis that the two samples are drawn from the same distribution, indicating drift [20].

Table 2: Detection Methods and Interpretation for Covariate Drift

| Method | Data Type | Key Metric | Interpretation Guide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Stability Index (PSI) | Categorical & Binned Continuous | PSI Value | < 0.1: Stable; 0.1-0.2: Slight Shift; >0.2: Large Shift [20] |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) Test | Continuous | p-value | p-value < 0.05 suggests significant drift [20] |

| Wasserstein Distance | Continuous | Distance Metric | Larger values indicate greater distributional difference [16] |

| Model-Based Detection | Any | Classifier Accuracy | Train a model to distinguish reference vs. current data; high accuracy indicates easy separability, hence drift [20] |

Detecting Concept Drift

Concept drift detection is more challenging as it involves monitoring the relationship between ( X ) and ( Y ), which requires ground truth labels for the target variable [15] [17].

Protocol 2: Adaptive Windowing (ADWIN) and Performance Monitoring ADWIN is an algorithm designed to detect changes in the data stream by dynamically adjusting a sliding window [20].

- Data Stream Setup: Maintain a sliding window ( W ) of recent data points, where each point can be a model prediction or an input-output pair.

- Window Splitting: For every new data point added to ( W ), the algorithm checks every possible split of ( W ) into two sub-windows (( W0 ) for old data and ( W1 ) for new data).

- Mean Comparison: Calculate the mean of a metric (e.g., prediction error, feature value) in ( W0 ) and ( W1 ).

- Drift Decision: If the absolute difference between the two means exceeds a pre-defined threshold ( \theta ), derived from the Hoeffding bound, a drift is detected. The older sub-window ( W_0 ) is then dropped [20].

- Performance Monitoring: A direct method is to track model performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) on a holdout validation set or on newly labeled production data. A sustained drop in performance is a strong indicator of concept drift [15] [21].

The workflow for a comprehensive, drift-aware monitoring system is depicted below.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for monitoring and detecting both covariate and concept drift in a production ML system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing the aforementioned experimental protocols requires a suite of statistical tools and software libraries. The following table details essential "research reagents" for scientists building drift-resistant ML systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Drift Detection and Management

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test [16] [20] | Statistical Test | Compare cumulative distributions of two samples. | Non-parametric testing for covariate shift on continuous features. |

| Population Stability Index (PSI) [16] [20] | Statistical Metric | Quantify the shift in a feature's distribution over time. | Monitoring stability of categorical and binned continuous features in production. |

| ADWIN Algorithm [20] | Change Detection Algorithm | Detect concept drift in a data stream with adaptive memory. | Real-time monitoring of model predictions or errors for sudden or gradual concept drift. |

| Page-Hinkley Test [21] [20] | Change Detection Algorithm | Detect a change in the average of a continuous signal. | Detecting subtle, gradual concept drift by monitoring the mean of a performance metric. |

| Evidently AI / scikit-multiflow [21] [17] | Open-Source Library | Provide pre-built reports and metrics for data and model drift. | Accelerating the development of monitoring dashboards and automated tests in Python. |

| Unified MLOps Platform (e.g., IBM Watsonx, Seldon) [16] [18] | Commercial Platform | End-to-end model management, deployment, and drift detection. | Enterprise-grade governance, automated retraining, and centralized monitoring of model lifecycle. |

Mitigation Strategies and Best Practices for Model Generalizability

Detecting drift is only the first step; a proactive strategy for mitigation is crucial for maintaining model generalizability. The chosen strategy often depends on the type and nature of the drift.

For Covariate Drift:

- Periodic Retraining: The most common approach is to regularly retrain the model on a more recent and representative dataset [17] [20]. This updates the model's understanding of the current feature space.

- Importance Weighting: Assign higher weights to examples in the training dataset that are more similar to the current production data distribution, thereby correcting for the shift [15].

- Domain Adaptation: Techniques that explicitly learn a mapping between the old (source) and new (target) feature distributions can be employed to adapt the model without complete retraining [15].

For Concept Drift:

- Triggered Retraining: Instead of a fixed schedule, implement event-driven retraining that is activated when a drift detection algorithm, like ADWIN, fires an alert [19] [20].

- Online Learning: Implement models that can update their parameters incrementally with each new data point, allowing them to adapt continuously to a changing concept [16] [19].

- Ensemble Methods: Use ensembles of models trained on different time periods. This allows the system to weigh the predictions of models that are more relevant to the current concept more heavily [22].

A unified best practice is to manage models in a centralized environment that provides a holistic view of data lineage, model performance, and drift metrics across development, validation, and deployment phases [16]. This is essential for rigorous external dataset validation and environmental ML research, where transparency and reproducibility are critical. Furthermore, root cause analysis should be performed to understand whether drift is sudden, gradual, or seasonal, as this informs the most appropriate mitigation response [16] [19].

Within the critical framework of model generalizability, understanding and managing dataset shift is non-negotiable for deploying reliable ML systems in dynamic real-world environments. Covariate drift and concept drift represent two distinct manifestations of this challenge, one stemming from a change in the input data landscape and the other from a change in the fundamental rules mapping inputs to outputs. As detailed in this guide, their differences necessitate distinct experimental protocols for detection—focusing on feature distribution statistics and model performance streams, respectively. A rigorous, scientifically grounded approach combines the statistical "reagents" and mitigation strategies outlined here, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to build more robust, drift-aware systems that maintain their validity and utility over time and across diverse datasets.

The deployment of machine learning (ML) models for COVID-19 diagnosis represented a promising technological advancement during the global pandemic. However, the transition from controlled development environments to real-world clinical application has revealed significant performance gaps across different healthcare settings. This case study systematically examines the generalizability challenges of COVID-19 diagnostic models when validated on external datasets, focusing on the environmental and methodological factors in ML research that contribute to these disparities. As healthcare systems increasingly rely on predictive algorithms for clinical decision-making, understanding these limitations becomes paramount for developing robust, translatable models that maintain diagnostic accuracy across diverse patient populations and institutional contexts. Through analysis of multi-site validation studies, we identify key determinants of model performance degradation and propose frameworks for enhancing cross-institutional reliability.

Performance Disparities in External Validation

Quantitative Evidence of Performance Gaps

External validation studies consistently demonstrate that COVID-19 diagnostic models experience significant performance degradation when applied to new healthcare settings. The following table synthesizes key findings from multi-site validation studies:

Table 1: Performance Gaps in External Validation of COVID-19 Diagnostic Models

| Study Description | Original Performance (AUROC) | External Validation Performance (AUROC) | Performance Gap | Key Factors Contributing to Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 prognostic models for mortality risk in older populations across hospital, primary care, and nursing home settings [23] | Varies by original model (e.g., 4C Mortality Score) | 0.55-0.71 (C-statistic) | Significant miscalibration and overestimation of risk | Population heterogeneity (age ≥70), setting-specific protocols, overfitting |

| ML models for COVID-19 diagnosis using CBC data across 3 Italian hospitals [24] | ~0.95 (internal validation) | 0.95 average AUC maintained | Minimal gap with proper validation | Cross-site transportability achieved through rigorous external validation |

| ML screening model across 4 NHS Trusts using EHR data [25] | 0.92 (internal at OUH) | 0.79-0.87 (external "as-is" application) | 5-13 point AUROC decrease | Site-specific data distributions, processing protocols, unobserved confounders |

| 6 clinical prediction models for COVID-19 diagnosis across two ED triage centers [26] | Varied by original model | AUROC <0.80 for symptom-based models; >0.80 for models with biological/radiological parameters | Poor agreement between models (Kappa and ICC <0.5) | Variable composition, differing predictor availability |

Cross-Setting Performance Variations

The performance degradation manifests differently across healthcare settings, with particularly notable disparities in specialized environments. A comprehensive validation of six prognostic models for predicting COVID-19 mortality risk in older populations (≥70 years) across hospital, primary care, and nursing home settings revealed substantial calibration issues [23]. The 4C Mortality Score emerged as the most discriminative model in hospital settings (C-statistic: 0.71), yet all models demonstrated concerning miscalibration, with calibration slopes ranging from 0.24 to 0.81, indicating systematic overestimation of mortality risk, particularly in non-hospital settings [23].

Similarly, a multi-site study of ML-based COVID-19 screening across four UK NHS Trusts reported performance variations directly attributable to healthcare setting differences [25]. When applied "as-is" without site-specific customization, ready-made models experienced AUROC decreases of 5-13 points compared to their original development environment. This performance gap was most pronounced when models developed in academic hospital settings were applied to community hospitals or primary care facilities with different patient demographics and data collection protocols [25].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Site Validation

External Validation Methodologies

Rigorous external validation protocols are essential for quantifying model generalizability. The following experimental approaches have been employed in COVID-19 diagnostic model research:

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Multi-Site Model Validation

| Protocol Component | Implementation Examples | Purpose | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Source Separation | Training and validation splits by hospital rather than random assignment [27] | Prevent data leakage and overoptimistic performance estimates | Reveals true cross-site performance gaps that random splits would mask |

| Site-Specific Customization | Transfer learning, threshold recalibration, feature reweighting [25] | Adapt ready-made models to new settings with limited local data | Transfer learning improved AUROCs to 0.870-0.925 vs. 0.79-0.87 for "as-is" application |

| Calibration Assessment | Brier score, calibration plots, calibration-in-the-large [24] [23] | Evaluate prediction reliability beyond discrimination | Widespread miscalibration detected despite acceptable discrimination in mortality models [23] |

| Comprehensive Performance Metrics | Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV across prevalence scenarios [27] | Assess clinical utility under real-world conditions | High NPV (97-99.9%) maintained across prevalence levels for CBC-based models [27] |

Case Study: Complete Blood Count Model Validation

A particularly robust validation protocol was implemented for ML models predicting COVID-19 diagnosis using complete blood count (CBC) parameters and basic demographics [24]. The study employed three distinct datasets collected at different hospitals in Northern Italy (San Raffaele, Desio, and Bergamo), encompassing 816, 163, and 104 COVID-19 positive cases respectively [24]. The external validation procedure assessed both error rate and calibration using multiple metrics including AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and Brier score.

Six different ML architectures were evaluated: Random Forest, Logistic Regression, SVM (RBF kernel), k-Nearest Neighbors, Naive Bayes, and a voting ensemble model [24]. The preprocessing pipeline included missing data imputation using multivariate nearest neighbors-based imputation, feature scaling, and recursive feature elimination for feature selection. Hyperparameters were optimized using grid-search 5-fold nested cross-validation [24].

This rigorous methodology demonstrated that models based on routine blood tests could maintain performance across sites, with the best-performing model (SVM) achieving an average AUC of 97.5% (sensitivity: 87.5%, specificity: 94%) across validation sites, comparable with RT-PCR performance [24].

Factors Influencing Model Generalizability

Data Quality and Variability Issues

Multisource data variability represents a fundamental challenge to model generalizability. Analysis of the nCov2019 dataset revealed that cases from different countries (China vs. Philippines) were separated into distinct subgroups with virtually no overlap, despite adjusting for age and clinical presentation [28]. This source-specific clustering persisted across different analytical approaches, suggesting profound underlying differences in data generation or collection protocols.

The specific factors contributing to performance gaps include:

Population Heterogeneity: Models developed on general adult populations show significantly degraded performance in specialized populations like older adults (≥70 years), with miscalibration and overestimation of risk [23].

Temporal Shifts: Models developed during early pandemic waves may not maintain performance during later waves with new variants, as demonstrated by changing test sensitivity patterns between delta and omicron variants [29].

Site-Specific Protocols: Differences in laboratory techniques, sample collection methods, and data recording practices introduce systematic variations that models cannot account for without explicit training [28] [25].

Unmeasured Confounders: Environmental factors, socioeconomic variables, and local healthcare policies that are not captured in the model can significantly impact performance across sites [30] [31].

Environmental and Social Confounders

The complex interplay between environmental factors and COVID-19 transmission further complicates model generalizability. Research examining early-stage COVID-19 transmission in China identified 113 potential influencing factors spanning meteorological conditions, air pollutants, social data, and intervention policies [31]. Through machine learning-based classification and regression models, researchers found that traditional statistical approaches often overestimate the impact of environmental factors due to unaddressed confounding effects [31].

A Double Machine Learning (DML) causal model applied to COVID-19 outbreaks in Chinese cities demonstrated that environmental factors are not the dominant cause of widespread outbreaks when confounding factors are properly accounted for [30]. This research revealed significant heterogeneity in how environmental factors influence COVID-19 spread, with effects varying substantially across different regional environments [30]. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for geographic and environmental context when developing diagnostic and prognostic models for infectious diseases.

Visualization of External Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for assessing model generalizability across healthcare settings:

External Validation Assessment Workflow

This workflow illustrates the transition from single-site model development through multi-site external validation to customization strategies that enhance generalizability.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols for evaluating COVID-19 diagnostic model generalizability rely on specific methodological components and data resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Generalizability Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Site Datasets | Enable external validation across diverse populations and settings | Electronic Health Records from 4 NHS Trusts with different demographic profiles [25] |

| Preprocessing Pipelines | Standardize data handling while accounting for site-specific characteristics | Multivariate nearest neighbors-based imputation with recursive feature elimination [24] |

| Calibration Assessment Tools | Evaluate prediction reliability beyond discrimination metrics | Brier score, calibration plots, and calibration-in-the-large metrics [24] [23] |

| Transfer Learning Frameworks | Adapt pre-trained models to new settings with limited data | Neural network fine-tuning using site-specific data [25] |

| Causal Inference Methods | Disentangle confounding effects in observational data | Double Machine Learning (DML) to estimate debiased causal effects [30] |

| Performance Metrics Suite | Comprehensive assessment of clinical utility | Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV across prevalence scenarios with decision curve analysis [26] [27] |

This case study demonstrates that performance gaps in COVID-19 diagnostic models across hospitals represent a significant challenge to real-world clinical implementation. The evidence from multiple validation studies reveals consistent patterns of performance degradation when models are applied to new healthcare settings, particularly across different care environments (hospital vs. primary care vs. nursing homes) and patient populations. The factors underlying these gaps are multifaceted, encompassing data quality variability, population heterogeneity, temporal shifts, and unmeasured confounders.

However, rigorous external validation protocols and strategic customization approaches show promise in mitigating these gaps. Methods such as transfer learning, threshold recalibration, and causal modeling techniques can enhance model generalizability without requiring complete retraining. Future research should prioritize prospective multi-site validation during model development, standardized reporting of cross-site performance metrics, and the development of more adaptable algorithms capable of maintaining performance across diverse healthcare environments. As infectious disease threats continue to emerge, building diagnostic tools that remain accurate across healthcare settings is paramount for effective pandemic response.

The exposome is defined as the totality of human environmental (all non-genetic) exposures from conception onwards, complementing the genome in shaping health outcomes [32]. This framework provides a new paradigm for studying the impact of environment on health, encompassing environmental pollutants, lifestyle factors, and behaviours that play important roles in serious, chronic pathologies with large societal and economic costs [32]. The classical orientation of exposure research initially focused on biological, chemical, and physical exposures, but has evolved to integrate the social environment—including social, psychosocial, socioeconomic, sociodemographic, and cultural aspects at individual and contextual levels [33].

The exposure concept is grounded in systems theory and a life cycle approach, providing a conceptual framework to identify and compare relationships between differential levels of exposure at critical life stages, personal health outcomes, and health disparities at a population level [34]. This approach enables the generation and testing of hypotheses about exposure pathways and the mechanisms through which exogenous and endogenous exposures result in poor personal health outcomes. Recent research has demonstrated that the exposure explains a substantially greater proportion of variation in mortality (an additional 17 percentage points) compared to polygenic risk scores for major diseases [35], highlighting its critical role in understanding aging and disease etiology.

Comparative Frameworks for Exposure Assessment

Approaches to Exposure Science

The field of exposure science employs multiple methodological frameworks for assessing and comparing exposures across populations and contexts. These approaches range from comparative exposure assessment in chemical alternatives to comprehensive exposure-wide association studies (XWAS) in large-scale epidemiological research.

Table 1: Comparison of Exposure Assessment Frameworks

| Framework Type | Primary Focus | Key Applications | Methodological Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Exposure Assessment (CEA) [36] [37] | Chemical substitution | Alternatives assessment for hazardous chemicals | Compares exposure routes, pathways, and levels between chemicals of concern and alternatives |

| Social Exposure Framework [33] | Social environment | Health equity research | Examines multidimensional social, economic, and environmental determinants of health |

| Exposome-Wide Association Study (XWAS) [35] | Systematic exposure identification | Large-scale cohort studies | Serially tests hundreds of environmental exposures in relation to health outcomes |

| Public Health Exposure [34] | Translational research | Health disparities and community engagement | Applies transdisciplinary tools across exposure pathways and mechanisms |

Comparative Exposure Assessment in Chemical Alternatives

Comparative Exposure Assessment (CEA) plays a crucial role in alternatives assessment frameworks for evaluating safer chemical substitutions [36]. The committee's approach to exposure involves: (a) considering the potential for reduced exposure due to inherent properties of alternative chemicals; (b) ensuring any substantive changes to exposure routes and increases in exposure levels are identified; and (c) allowing for consideration of exposure routes (dermal, oral, inhalation), patterns (acute, chronic), and levels irrespective of exposure controls [36].

The NRC framework outlines a staged approach for comparative exposure assessment [36]:

- Problem formulation to identify expected exposure patterns and routes

- Comparative exposure assessment to estimate relative exposure differences

- Additional assessment when concerns are identified through life cycle thinking

- Optional quantitative assessment for comprehensive evaluation

This approach focuses on factors intrinsic to chemical alternatives or inherent to the product into which the substance will be integrated, excluding extrinsic mitigation factors like engineering controls or personal protective equipment, consistent with the industrial hierarchy of controls [36].

Validation of Exposure Frameworks

Recent research has developed robust validation pipelines for exposure assessment to address reverse causation and residual confounding [35]. This involves:

- Exposome-wide analysis to identify exposures associated with mortality

- Phenome-wide analysis for each mortality-associated exposure to remove exposures sensitive to confounding

- Biological aging correlation to ensure exposures associate with proteomic aging clocks

- Hierarchical clustering to decompose confounding through exposure correlation structure

This systematic approach has identified 25 independent exposures associated with both mortality and proteomic aging, providing a comprehensive map of the contributions of environment and genetics to mortality and incidence of common age-related diseases [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Exposome-Wide Association Study (XWAS) Protocol

The exposure-wide association study represents a systematic approach for identifying environmental factors associated with health outcomes, mirroring the comprehensive nature of genome-wide association studies [35].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Exposome-Wide Analysis

| Protocol Step | Methodological Details | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure Assessment | 164 environmental exposures tested via Cox proportional hazards models | Independent discovery and replication subsets; sensitivity analyses excluding early deaths |

| Confounding Assessment | Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) for each exposure | Exclusion of exposures strongly associated with disease, frailty, or disability phenotypes |

| Biological Validation | Association testing with proteomic age clock | False discovery rate correction; direction consistency with mortality associations |

| Cluster Analysis | Hierarchical clustering of exposures | Decomposition of confounding through correlation structure |

The proteomic age clock serves as a crucial validation tool, representing the difference between protein-predicted age and calendar age, and has been demonstrated to associate with mortality, major chronic age-related diseases, multimorbidity, and aging phenotypes [35]. This multidimensional measure of biological aging captures biology relevant across multiple aging outcomes.

Mechanistic Pathway Analysis: Benzo(a)pyrene-Induced Immunosuppression

Research elucidating the mechanism of exposure-induced immunosuppression by benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P] provides a detailed example of exposure pathway analysis [34]. The experimental workflow examined the effects of B(a)P exposure on lipid raft integrity and CD32a-mediated macrophage function.

Diagram 1: B(a)P Immunosuppression Pathway (76 chars)

The methodology involved [34]:

- Cell culture: Fresh human CD14+ monocytes cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, penicillin/streptomycin

- Exposure protocol: Treatment with Benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P] powder dissolved in DMSO

- Lipid raft analysis: Cholesterol measurement using Amplex Red Cholesterol Assays

- Receptor localization: CD32a detection using PE anti-human CD32 antibody

- Functional assays: IgG binding assessment with Anti-Human IgG(γ)-FITC conjugate

Results demonstrated that exposure of macrophages to B(a)P alters lipid raft integrity by decreasing membrane cholesterol 25% while increasing CD32 into non-lipid raft fractions [34]. This robust diminution in membrane cholesterol and 30% exclusion of CD32 from lipid rafts caused significant reduction in CD32-mediated IgG binding, suppressing essential macrophage effector functions.

Machine Learning Integration in Exposure Research

Machine learning approaches provide tools for improving discovery and decision making for well-specified questions with abundant, high-quality data in exposure research [38]. ML applications in drug discovery and development include:

- Target validation and identification of prognostic biomarkers

- Analysis of digital pathology data in clinical trials

- Bioactivity prediction and de novo molecular design

- Biological image analysis at all levels of resolution

Deep learning approaches, including deep neural networks (DNNs), have shown particular utility in exposure research due to their ability to handle complex, high-dimensional data [38]. Specific architectures include:

- Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for speech and image recognition

- Graph convolutional networks for structured graph data

- Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for analyzing dynamic changes over time

- Deep autoencoder neural networks (DAEN) for dimension reduction

The predictive power of any ML approach in exposure research is dependent on the availability of high volumes of data of high quality, with data processing and cleaning typically consuming at least 80% of the effort [38].

Data Integration and Analytical Approaches

Relative Contributions of Exposure and Genetics

Large-scale studies have quantified the relative contributions of the exposure and genetics to aging and premature mortality, providing insights into their differential roles across disease types [35].

Table 3: Exposome vs. Genetic Contributions to Disease Incidence

| Disease Category | Exposome Contribution (%) | Polygenic Risk Contribution (%) | Key Associated Exposures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Diseases | 25.1-49.4 | 2.3-5.8 | Smoking, air pollution, occupational exposures |

| Hepatic Diseases | 15.7-33.2 | 3.1-6.9 | Alcohol consumption, dietary factors, environmental toxins |

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 5.5-28.9 | 4.2-9.7 | Diet, physical activity, socioeconomic factors |

| Dementias | 2.1-8.7 | 18.5-26.2 | Education, social engagement, cardiovascular health factors |

| Cancers (Breast, Prostate, Colorectal) | 3.3-12.4 | 10.3-24.8 | Variable by cancer site |

The findings demonstrate that the exposure shapes distinct patterns of disease and mortality risk, irrespective of polygenic disease risk [35]. For mortality, the exposure explained an additional 17 percentage points of variation compared to information on age and sex alone, while polygenic risk scores for 22 major diseases explained less than 2 percentage points of additional variation.

Integration of Social and Environmental Determinants

The Social Exposure framework addresses the gap in terms of the social domain within current exposure research by integrating the social environment in conjunction with the physical environment [33]. This framework emphasizes three core principles underlying the interplay of multiple exposures:

- Multidimensionality: The complex, interconnected nature of social exposures

- Reciprocity: Bidirectional relationships between exposures and health outcomes

- Timing and continuity: The importance of life course exposure patterns

The framework incorporates three transmission pathways linking social exposures to health outcomes [33]:

- Embodiment: Biological incorporation of social experiences

- Resilience, Susceptibility, and Vulnerability: Differential response to exposures

- Empowerment: Capacity to modify exposures and responses

This approach incorporates insights from research on health equity and environmental justice to uncover how social inequalities in health emerge, are maintained, and systematically drive health outcomes [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Exposure Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | Fresh human CD14+ monocytes | Model system for immune response | Macrophage effector function studies [34] |

| Antibodies for Immunophenotyping | PE anti-human CD32, CD68-FITC, CD86-Alexa-Fluor | Cell surface receptor detection | Flow cytometry, receptor localization [34] |

| Chemical Exposure Standards | Benzo(a)pyrene [B(a)P] powder | Model environmental contaminant | PAH exposure studies [34] |

| Cholesterol Assays | Amplex Red Cholesterol Assay | Lipid raft integrity assessment | Membrane fluidity studies [34] |

| Proteomic Analysis Kits | Plasma proteomics platforms | Biological age assessment | Proteomic age clock development [35] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | High-dimensional data analysis | Exposure pattern recognition [38] |

The exposure framework represents a paradigm shift in environmental health research, moving from single-exposure studies to a comprehensive approach that captures the totality of environmental exposures across the lifespan. The integration of environmental, clinical, and lifestyle data provides powerful insights into disease etiology and aging processes.

Recent methodological advancements include:

- Systematic exposure-wide analyses that account for correlation structures across exposures [35]

- Robust validation pipelines that address reverse causation and residual confounding

- Integration with high-dimensional omics technologies for biological validation

- Machine learning approaches for pattern recognition in complex exposure data

The evidence demonstrates that the exposure explains a substantial proportion of variation in mortality and age-related disease incidence, exceeding the contribution of genetics for many disease categories, particularly those affecting the lung, heart, and liver [35]. This highlights the critical importance of environmental interventions for disease prevention and health promotion.

Future directions in exposure research include greater integration of social and environmental determinants, development of more sophisticated analytical approaches for exposure-wide studies, and application of the framework to inform targeted interventions that address the most consequential exposures for population health and health equity.

Building Robust Models: Methodologies for Cross-Site and Cross-Population Generalization

Meta-validation represents a critical methodological advancement for assessing the soundness of external validation (EV) procedures in medical machine learning (ML) and environmental ML research. In clinical and translational research, ML models often demonstrate inflated performance on data from their development cohort but fail to generalize to new datasets, primarily due to overfitting or covariate shifts [39]. External validation is thus a necessary practice for evaluating medical ML models, yet a significant gap persists in interpreting EV results and assessing model robustness [39] [40]. Meta-validation addresses this gap by providing a framework to evaluate the evaluation process itself, ensuring that conclusions about model generalizability are scientifically sound.

The core premise of meta-validation is that a proper assessment of external validation must extend beyond simple performance metrics to consider two fundamental aspects: dataset cardinality (the adequacy of sample size) and dataset similarity (the distributional alignment between training and validation data) [39]. These complementary dimensions inform researchers about the reliability of their validation procedures and help contextualize performance changes when models are applied to external datasets. As ML models increasingly inform critical decisions in drug development and healthcare, establishing rigorous meta-validation practices becomes essential for determining which models are truly ready for real-world deployment.

Theoretical Framework of Meta-Validation

The Dual Pillars: Data Cardinality and Similarity

Meta-validation introduces a structured approach to assessing external validation procedures through two complementary criteria:

Data Cardinality Criterion: This component focuses on sample size adequacy for the validation set. It ensures that the external dataset contains sufficient observations to provide statistically reliable performance estimates. The cardinality assessment helps researchers avoid drawing conclusions from validation sets that are too small to detect meaningful performance differences or variability [39].

Data Representativeness Criterion: This element evaluates the similarity between the training and external validation datasets. It addresses distributional shifts that can undermine model generalizability, including differences in population characteristics, measurement techniques, or clinical practices across data collection sites [39].

The interplay between these criteria creates a comprehensive framework for interpreting external validation results. A model exhibiting performance degradation on a large, highly similar external dataset raises more serious concerns than the same performance drop on a small, dissimilar dataset, as the former more likely indicates genuine limitations in model generalizability.

Methodological Foundations

The meta-validation methodology integrates recent metrics and formulas into a cohesive toolkit for qualitatively and visually assessing validation procedure validity [39]. This lean meta-validation approach incorporates:

Similarity Quantification: Statistical measures to quantify the distributional alignment between training and validation datasets, including potential use of maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) or similar distribution distance metrics [39].

Cardinality Sufficiency Tests: Analytical methods to determine whether external datasets meet minimum sample size requirements for reliable performance estimation [39].

Integrated Visualizations: Composite graphical representations that simultaneously display cardinality and similarity relationships across multiple validation datasets, enabling intuitive assessment of validation soundness [39].

This methodological framework shifts the focus from simply whether a model passes external validation to how confidently we can interpret the results of that validation given the characteristics of the datasets involved.

Quantitative Metrics for Meta-Validation Assessment

Core Metrics and Their Interpretation

Meta-validation employs specific quantitative metrics to operationalize the assessment of external validation procedures. The table below summarizes the key performance dimensions and similarity measures used in a comprehensive meta-validation assessment:

Table 1: Key Metrics for Meta-Validation Assessment

| Assessment Dimension | Specific Metrics | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Model Discrimination | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Good: ≥0.80Acceptable: 0.70-0.79Poor: <0.70 |

| Model Calibration | Calibration Error | Excellent: <0.10Acceptable: 0.10-0.20Poor: >0.20 |

| Clinical Utility | Net Benefit | Context-dependent, higher values indicate better tradeoff between benefits and harms |

| Dataset Similarity | Pearson Correlation (ρ) | Strong: >0.50Moderate: 0.30-0.50Weak: <0.30 |

| Statistical Significance | p-value | <0.05 indicates statistically significant relationship |

In practice, these metrics are applied collectively rather than in isolation. For example, a COVID-19 diagnostic model evaluated through meta-validation demonstrated good discrimination (average AUC: 0.84), acceptable calibration (average: 0.17), and moderate utility (average: 0.50) across external validation sets, with dataset similarity moderately impacting performance (Pearson ρ = 0.38, p < 0.001) [39] [40].

Advanced Statistical Measures for Inconsistency Assessment

Beyond basic performance metrics, meta-validation can incorporate specialized statistical tests to evaluate between-study inconsistency, particularly relevant when validating models across multiple external datasets. Recent methodological advancements propose alternative heterogeneity measures beyond conventional Q statistics, which may have limited power when between-study distribution deviates from normality or when outliers are present [41].

These advanced measures include:

Q-like Statistics with Different Mathematical Powers: Alternative test statistics based on sums of absolute values of standardized deviates with different powers (e.g., square, cubic, maximum) designed to capture different patterns of between-study distributions [41].

Hybrid Tests: Adaptive testing approaches that combine strengths of various inconsistency tests, using minimum P-values from multiple tests to achieve relatively high power across diverse settings [41].

Resampling Procedures: Parametric resampling methods to derive null distributions and calculate empirical P-values for hybrid tests, properly controlling type I error rates [41].

These sophisticated statistical tools enhance the meta-validation framework by providing more nuanced assessments of performance consistency across validation datasets with different characteristics.

Experimental Protocols for Meta-Validation

Standardized Meta-Validation Workflow

Implementing meta-validation requires a systematic approach to assessing external validation procedures. The following workflow provides a detailed protocol for conducting comprehensive meta-validation:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Meta-Validation Assessment

| Protocol Step | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dataset Characterization | Profile training and validation datasets for key characteristics, distributions, and demographics | Document source populations, collection methods, temporal factors |

| 2. Similarity Quantification | Calculate distributional similarity metrics between training and validation sets | Use appropriate statistical measures (e.g., MMD, correlation) for data types |

| 3. Cardinality Assessment | Evaluate whether validation datasets meet minimum sample size requirements | Consider performance metric variability and statistical power |

| 4. Multi-dimensional Performance Evaluation | Assess model discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility across datasets | Use consistent evaluation metrics aligned with clinical application |

| 5. Correlation Analysis | Analyze relationships between similarity metrics and performance changes | Statistical significance testing for observed correlations |

| 6. Visual Integration | Create composite visualizations of cardinality, similarity, and performance | Enable intuitive assessment of validation soundness |

| 7. Soundness Interpretation | Draw conclusions about validation procedure robustness | Consider both individual and collective evidence across datasets |

This protocol emphasizes the importance of systematic documentation at each step to ensure transparent and reproducible meta-validation assessments. The workflow is illustrated in the following diagram:

Case Study Implementation: COVID-19 Diagnostic Model

The practical application of meta-validation is illustrated through a case study validating a COVID-19 diagnostic model across 8 external datasets collected from 3 different continents [39] [40]. The implementation followed these specific experimental procedures:

Model and Data Selection: A state-of-the-art COVID-19 diagnostic model based on routine blood tests was selected, with training data from original development cohorts and external validation sets from geographically distinct populations.

Similarity Measurement: Distributional similarity between training and each validation set was quantified using statistical measures, revealing moderate correlation with performance impact (Pearson ρ = 0.38, p < 0.001).

Cardinality Evaluation: Each validation dataset was assessed for sample size adequacy relative to minimum requirements for reliable performance estimation.

Performance Assessment: The model was evaluated across all external datasets using discrimination (AUC), calibration, and clinical utility metrics, with performance variability analyzed in context of dataset characteristics.

Meta-Validation Conclusion: The soundness of the overall validation procedure was determined based on the adequacy of validation datasets in terms of both cardinality and similarity, supporting the reliability of conclusions about model generalizability.

This case study demonstrates how meta-validation provides a structured approach to interpreting external validation results, moving beyond simplistic pass/fail assessments to contextualized understanding of model robustness.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Internal vs. External Validation

Understanding meta-validation requires situating it within the broader landscape of validation approaches. The table below compares key characteristics of internal and external validation methods:

Table 3: Comparison of Internal and External Validation Approaches

| Validation Aspect | Internal Validation | External Validation | Meta-Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Random splits from development dataset (hold-out, cross-validation) | Fully independent datasets from different sources/sites | Assessment of external validation procedures |

| Primary Focus | Performance estimation on similar data | Generalizability to new populations/settings | Soundness of generalizability assessment |

| Key Strengths | Convenient, efficient for model development | Real-world generalizability assessment | Contextualizes interpretation of EV results |

| Key Limitations | Risk of overfitting, optimistic estimates | Resource-intensive, may show performance drops | Additional analytical layer required |

| Role in Validation Hierarchy | Foundational performance screening | Essential for clinical readiness assessment | Quality control for EV procedures |

Internal validation methods, including hold-out, bootstrap, or cross-validation protocols, partition the original dataset to estimate performance on unseen but distributionally similar data [39]. While computationally efficient, these approaches are increasingly recognized as insufficient for critical applications like medical ML, where models must demonstrate robustness across different clinical settings and population distributions [39].

Meta-Validation in the Context of Related Methodological Approaches

Meta-validation shares conceptual ground with several other methodological approaches focused on assessment quality:

Network Meta-Analysis Comparisons: Similar to approaches that compare alternative network meta-analysis methods when standard assumptions like proportional hazards are violated [42], meta-validation provides frameworks for selecting appropriate validation strategies based on dataset characteristics.

Algorithm Validation Frameworks: The development and validation of META-algorithms for identifying drug indications from claims data [43] [44] exemplifies the type of comprehensive validation approach that meta-validation seeks to assess and standardize.

Software Comparison Methods: Systematic comparisons of software dedicated to meta-analysis [45] parallel the systematic assessment focus of meta-validation, though applied to different analytical tools.

Method Comparison Approaches: Critical analyses of how methods are compared in fields like life cycle assessment (LCA) [46] highlight the broader need for standardized comparison frameworks that meta-validation addresses for external validation procedures.

These connections position meta-validation as part of an expanding methodological ecosystem focused on improving assessment rigor across scientific domains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions