Environmental Chemistry Method Transfer: Validation Protocols for Seamless Lab-to-Lab Transitions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating and transferring analytical methods in environmental chemistry.

Environmental Chemistry Method Transfer: Validation Protocols for Seamless Lab-to-Lab Transitions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating and transferring analytical methods in environmental chemistry. It covers foundational principles from regulatory bodies like the EPA and ICH, details practical methodological approaches for successful transfer, and offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls. The content also explores the critical integration of green chemistry metrics and sustainability assessments into validation protocols, ensuring methods are not only robust and compliant but also environmentally conscious. A forward-looking perspective on emerging trends, including automation and digital tools, is included to prepare laboratories for future advancements.

The Pillars of Validated Methods: Principles and Regulatory Frameworks

Defining Analytical Method Transfer and Validation in Environmental Contexts

This guide examines the critical processes of analytical method transfer and validation within environmental chemistry, framing them as complementary pillars of data quality assurance. We objectively compare the performance of different method transfer approaches—comparative testing, co-validation, and revalidation—against key criteria such as regulatory suitability, resource demands, and implementation speed. Supporting experimental data and detailed protocols are provided to equip researchers and scientists with practical tools for ensuring analytical reliability during technology transfer between laboratories, with a specific focus on applications governed by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines.

In environmental monitoring and pharmaceutical development, the reliability of analytical data is paramount. Analytical method validation is the comprehensive, documented process of proving that an analytical method is suitable for its intended use, establishing performance characteristics such as accuracy, precision, and specificity [1]. Method verification, in contrast, is the process of confirming that a previously validated method performs as expected in a specific laboratory [1].

Analytical method transfer is a closely related, documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use an analytical method that originated in a transferring laboratory [2] [3]. Its primary goal is to demonstrate that the method yields equivalent results in both laboratories, ensuring data consistency across different sites, instruments, and personnel [2] [4]. In environmental contexts, this process is often mandated by regulations, such as the EPA's requirement that "all methods of analysis must be validated, and peer reviewed prior to being issued" [5]. The recent Clean Water Act Methods Update Rule exemplifies the dynamic nature of approved methods, where new procedures for contaminants like PFAS are regularly incorporated, necessitating robust transfer protocols [6].

Comparative Analysis of Method Transfer Approaches

Selecting the correct transfer strategy is critical for success and compliance. The choice depends on the method's complexity, its regulatory status, and the experience level of the receiving laboratory [2] [3]. The table below compares the three primary transfer approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Analytical Method Transfer Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Key Principle | Regulatory Suitability | Resource Intensity | Implementation Speed | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [2] [4] | Both labs analyze identical samples; results are statistically compared for equivalence. | High for well-established, validated methods. | Moderate | Medium (weeks) | Transfer of established methods between labs with similar capabilities; ideal for assay, impurity, and particle size testing [3]. |

| Co-validation [2] [3] | The receiving laboratory participates in the original validation, often for intermediate precision. | High for new methods or those developed for multi-site use. | High | Slow (months) | Introduction of novel methods; transfers where close collaboration from the outset is possible. |

| Revalidation [2] [7] | The receiving laboratory performs a full or partial revalidation of the method. | High when significant differences in lab conditions or equipment exist. | Very High | Slow (months) | Scenarios where the transferring lab is unavailable or when method conditions have changed significantly. |

Supporting Experimental Data from Environmental Analysis

A 2025 study developing a pipette-tip micro-solid-phase extraction (PT-µSPE) method for analyzing water-based perfumes demonstrates the validation and transfer process. The method was compared against conventional approaches using the White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework, which balances analytical performance (red), greenness (green), and practical effectiveness (blue) [8].

Table 2: Performance Data of PT-µSPE vs. Conventional Methods

| Performance Metric | PT-µSPE Method | Conventional SPE | Direct Injection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume Required | 10 mg | ~100 mL | 1 µL |

| Solvent Consumption | 100 µL heptane/ethyl acetate | >10 mL | Not applicable |

| Analysis Time | ~30 minutes | Several hours | <1 hour (but with instrument maintenance) |

| Analytical Recovery (%) | 85-105% for target analytes [8] | Comparable | Inaccurate due to water/interferences |

| Greenness Score (WAC) | Balanced/Higher | Lower | Lower |

The data shows the PT-µSPE method offers a balanced alternative, reducing environmental impact and resource use while maintaining analytical integrity—a key consideration in modern environmental labs [8].

Experimental Protocols for Method Transfer and Validation

Detailed Protocol: Comparative Testing for an HPLC Method

This protocol is adapted from best practices for transferring a method for contaminant analysis in water samples [2] [3].

1. Pre-Transfer Planning (Protocol Development)

- Define Objective: To transfer a validated HPLC-MS/MS method for PFAS analysis from a research lab (TL) to a routine monitoring lab (RL).

- Develop Protocol: A detailed, pre-approved protocol is essential. It must specify: the method scope, responsibilities of both labs, list of materials and equipment, detailed analytical procedure, acceptance criteria (e.g., ±15% agreement for quantitation, precision RSD <10%), and a statistical analysis plan [2] [3].

2. Execution and Data Generation

- Sample Preparation: The TL prepares homogeneous, representative samples, including a blank, a calibration standard, and a spiked water sample at a known concentration (e.g., 100 ppt PFAS). These are split and shipped to the RL.

- Training & Familiarization: RL analysts receive training from the TL and a feasibility run is performed [4].

- Formal Testing: Both laboratories analyze the sample set in replicate (e.g., n=6) over different days or by different analysts to incorporate intermediate precision [2].

3. Data Evaluation and Reporting

- Statistical Comparison: Results are compared using pre-defined statistical tests (e.g., student's t-test for accuracy, F-test for precision) to demonstrate equivalence [2].

- Report: A comprehensive transfer report is generated, summarizing activities, results, deviations, and a final statement of acceptance [2] [3].

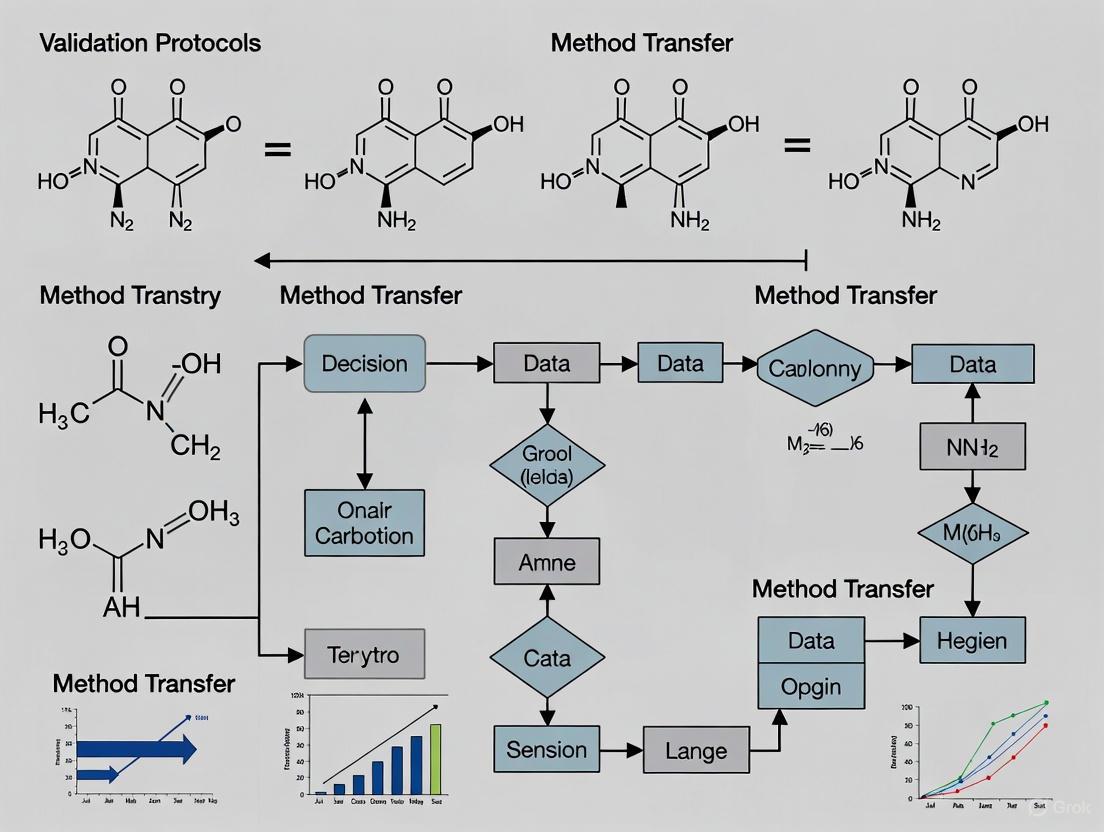

Workflow Diagram: Analytical Method Transfer Process

The following diagram visualizes the end-to-end method transfer process, highlighting the roles and responsibilities of the transferring and receiving laboratories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method transfer relies on the precise use of qualified materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the context of environmental and pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Transfer

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Example in Environmental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards [3] | Serves as the benchmark for quantifying analyte concentration and ensuring method accuracy. | Certified PFAS mixture in methanol for calibrating LC-MS/MS systems in water analysis [6]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used for sample preparation, dilution, and mobile phase preparation; purity is critical to prevent interference. | HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol for residue analysis; heptane/ethyl acetate for extracting fragrances [8]. |

| Sorbent Materials [8] | Used in sample preparation (e.g., SPE, PT-μSPE) to selectively isolate and concentrate target analytes from a matrix. | Celite 545 for pipette-tip micro-solid-phase extraction of allergens from water-based perfumes [8]. |

| System Suitability Solutions [3] | A mixture of key analytes used to verify that the entire analytical system (instrument, column, reagents) is performing adequately before sample analysis. | A test mix containing caffeine, uracil, and phenol for verifying HPLC system performance under specified parameters. |

Analytical method transfer and validation are not standalone events but integral parts of a method lifecycle that begins with development and continues through routine use [9]. In environmental chemistry, where regulatory frameworks like the EPA's Clean Water Act methods are constantly evolving [5] [6], a rigorous and documented approach to transferring methods is non-negotiable for data integrity.

The comparative data shows that comparative testing remains the most efficient and widely applicable strategy for transferring well-established methods between competent laboratories. However, for novel methods or those moving to labs with significantly different capabilities, co-validation or revalidation provide the necessary depth of assessment. Ultimately, the choice of transfer strategy must be guided by a risk-based assessment, focusing on the method's complexity, intended use, and the operational differences between laboratories to ensure the continued generation of reliable, high-quality environmental data.

In the fields of environmental chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the generation of reliable analytical data is paramount. Regulatory guidelines provide the critical framework that ensures methods are scientifically sound, reproducible, and suitable for their intended purpose, whether for monitoring environmental pollutants or ensuring drug safety. The global environmental testing market, projected to grow from USD 7.43 billion in 2025 to USD 9.32 billion by 2030, is propelled by stringent pollution control policies and heightened public health concerns [10]. This growth underscores the necessity for robust regulatory compliance. Navigating the complexities of various guidelines—from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and other global standards—is a fundamental challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. This guide provides a structured comparison of these frameworks, focusing on their application to method validation and transfer protocols, which form the bedrock of data integrity in environmental chemistry research.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

Scope, Core Principles, and Application

Different regulatory bodies have developed guidelines tailored to their specific domains, but all converge on the principle that analytical methods must be validated to prove their reliability.

- EPA Guidelines: The EPA provides method-specific protocols for environmental monitoring, covering air, water, soil, and waste. Their focus is on protecting human health and the environment, with an emphasis on method-specific acceptance criteria for parameters like precision and accuracy in detecting pollutants such as heavy metals and organic compounds [10] [11].

- ICH Q2(R2): The recently updated ICH Q2(R2) guideline, officially adopted in November 2023, provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of analytical procedures in the pharmaceutical industry. It builds upon Q2(R1) with expanded guidance, emphasizing a life-cycle approach to method development and validation, and is integrated with ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development [12]. Its primary focus is on ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of human pharmaceuticals.

- Global Standards (e.g., USP): Standards like the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) General Chapter

<1225>detail the validation of compendial methods. USP<1224>provides specific guidance on the transfer of analytical procedures. A key concept in this framework is the distinction between method validation (full qualification of a non-compendial method), method verification (confirming a compendial method works in a specific laboratory), and method transfer (qualifying a receiving laboratory to use an existing validated method) [2] [13].

Key Validation Parameters and Method Transfer Requirements

The following table summarizes the key validation parameters as emphasized by different regulatory bodies and their stance on method transfer.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Validation Parameters and Transfer Requirements

| Feature | ICH Q2(R2) / USP <1225> |

EPA Guidelines | Global Consensus (e.g., GBC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | Pharmaceutical quality control | Environmental monitoring (air, water, soil) | Bioanalytical methods (PK/toxicology) |

| Core Principles | Lifecycle approach, risk-based, integrated with development (Q14) | Environmental protection, public health | Documentation, traceability, continuous improvement |

| Validation Parameters | Specificity, Accuracy, Precision (Repeatability, Intermediate Precision), Linearity, Range, Detection Limit (LOD), Quantitation Limit (LOQ), Robustness [13] | Accuracy, Precision, Specificity/Selectivity, LOD, LOQ, Linearity | Accuracy, Precision, Selectivity, LOD, LOQ, Stability [14] |

| Method Transfer Approach | Comparative testing, co-validation, revalidation, waiver (USP <1224>) [2] |

Often method-specific or comparative testing | Defined tiers: internal vs. external transfer [14] |

| Key Documentation | Validation Protocol & Report, method suitability | Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP), method SOPs | Transfer Protocol, statistical equivalence report |

Experimental Protocols for Method Transfer and Validation

A successful method transfer is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use an analytical method that originated in a transferring laboratory, proving that it yields equivalent results [2] [13]. The following workflow and details outline the standard experimental protocols.

Phase 1: Pre-Transfer Planning and Assessment

This initial phase is critical for de-risking the entire process.

- Define Scope and Objectives: Clearly articulate the method's intended use and define pre-defined acceptance criteria for success (e.g., statistical limits for comparability) [2].

- Form Cross-Functional Teams: Designate leads and team members from both transferring and receiving labs, including Analytical Development, QA/QC, and Operations [2].

- Gather Method Documentation: Collect all relevant method validation reports, development reports, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), and raw data from the transferring lab [2].

- Conduct Gap and Risk Analysis: Compare equipment, reagents, software, and personnel expertise between the two labs. Identify potential risks (e.g., complex method steps, unique equipment) and develop mitigation strategies [2].

- Select Transfer Approach: Based on the risk assessment, choose the most appropriate strategy [2] [13]:

- Comparative Testing: Both labs analyze the same set of homogeneous samples; results are statistically compared. This is the most common approach.

- Co-validation: The method is validated simultaneously by both labs, ideal for new methods intended for multi-site use.

- Revalidation: The receiving lab performs a full or partial revalidation, used when there are significant differences in lab conditions or equipment.

- Transfer Waiver: Used rarely, with strong justification, when the receiving lab already has extensive proven proficiency with the method.

- Develop a Detailed Transfer Protocol: This is the cornerstone document. It must specify method details, responsibilities, materials, equipment, analytical procedures, pre-defined acceptance criteria for each performance parameter (e.g., %RSD for precision, %recovery for accuracy), and the statistical analysis plan [2] [14].

Phase 2: Execution and Data Generation

This phase involves the practical implementation of the transfer protocol.

- Personnel Training: Ensure analysts at the receiving lab are thoroughly trained by the transferring lab, with all training documented [2].

- Equipment Qualification and Calibration: Verify that all instruments at the receiving lab are comparable, properly qualified, and calibrated [2].

- Execute Protocol: Both laboratories perform the analytical method on the pre-defined samples according to the approved protocol. For a comparative testing of a wastewater method, this might involve analyzing a minimum of two sets of accuracy and precision data over a 2-day period, including quality controls at the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) [14]. All raw data, chromatograms, and calculations must be meticulously recorded [2].

Phase 3: Data Evaluation and Reporting

The generated data is rigorously evaluated to determine the success of the transfer.

- Data Compilation and Statistical Analysis: Collect all data from both laboratories and perform the statistical comparison outlined in the protocol (e.g., t-tests, F-tests, equivalence testing) [2].

- Evaluate Against Acceptance Criteria: Compare the results against the pre-defined acceptance criteria. Any deviations from the protocol or out-of-specification results must be thoroughly investigated and documented [2].

- Draft and Approve Final Transfer Report: A comprehensive report summarizing the activities, results, statistical analysis, deviations, and conclusions is prepared. This report must clearly state whether the transfer was successful and requires formal approval by all stakeholders and Quality Assurance [2] [13].

Supporting Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Statistical Performance of Analytical Methods

The choice of analytical and statistical method can significantly impact the results, especially when dealing with complex environmental mixtures. A 2025 simulation study compared traditional and machine-learning methods for analyzing the effect of environmental mixtures on survival outcomes, a common challenge in environmental epidemiology.

Table 2: Comparison of Statistical Methods for Environmental Mixture Analysis (Simulation Study Data) [15]

| Method | Model Flexibility | Performance under High Correlation | Performance with PH Violation | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox PH (Linear) | Low | Low coverage, high bias | Poor | Simple, widely used | Misses non-linear effects, strict assumptions |

| Cox PH (with Splines) | Medium | Medium coverage | Medium | Captures non-linearity | Computationally intensive, requires specification |

| Cox Elastic Net | Medium | Medium (with variable selection) | Medium | Handles high dimensions, selects variables | Constrained to linear/log-linear effects |

| BART (Bayesian Additive Regression Trees) | High | High coverage | High coverage | Excellent for complex interactions, automated | High variability, computationally demanding |

| MARS (Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines) | High | High coverage | High coverage | Models non-linearity and interactions | Can produce complex, less interpretable models |

The study found that while flexible models like BART and MARS were better at estimating the true mixture effect under most scenarios (especially with correlated exposures or violations of the proportional hazards (PH) assumption), they introduced higher variability. In contrast, traditional log-linear models like the standard Cox Proportional Hazards (PH) model achieved low coverage and high bias under these complex, real-world conditions [15]. This highlights the importance of aligning the analytical method with the complexity of the data and evaluating findings across multiple methods.

Method Transfer Success Rates and Common Pitfalls

While quantitative success rates are often proprietary, regulatory audits and industry consensus highlight recurring challenges that lead to transfer failure or delay. A primary cause is inadequate pre-planning and gap analysis, leading to unforeseen differences in equipment or analyst skill [16] [2]. Furthermore, a lack of technical skill and equipment in the receiving laboratory is a major factor that dampens market growth and hampers successful transfer [16]. Finally, failures often stem from poorly defined acceptance criteria in the transfer protocol and insufficient statistical power in the experimental design, resulting in inconclusive or failed comparative testing [2] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The reliability of analytical results is fundamentally dependent on the quality of materials used throughout method validation and transfer.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation and Transfer

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | To calibrate instruments and establish the accuracy of an analytical method. They provide a traceable chain of measurement. | Source and certification traceability to national/international standards (e.g., NIST). Purity and stability during storage [13]. |

| High-Purity Solvents and Reagents | Used for sample preparation, mobile phases, and standard solutions. Their quality is vital for achieving low background noise and specific detection. | Grade suitability (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS), lot-to-lot consistency, and levels of interfering impurities [14]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Used in chromatographic assays (e.g., LC-MS) to correct for matrix effects, recovery losses, and instrument variability. | Isotopic purity, chemical stability, and identical behavior to the analyte during extraction. |

| Critical Reagents (e.g., Antibodies, Enzymes) | Essential for ligand binding assays (e.g., ELISA) and biosensors. They define the method's specificity [14]. | Lot-to-lot variability, which requires bridging studies; storage conditions and shelf-life [14] [11]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Used to monitor the performance of the assay during validation, transfer, and routine use. | Preparation in the same matrix as the study samples (e.g., surface water, serum); characterization of target concentrations (low, mid, high) [14]. |

Navigating the landscape of EPA, ICH Q2(R2), and global standards reveals a unified goal: ensuring the generation of reliable and meaningful analytical data. While their applications differ—environmental protection versus pharmaceutical quality—the core principles of validation are consistent. The emergence of advanced statistical models and rapid testing technologies offers powerful tools for tackling complex environmental mixtures [10] [15] [11]. Success, however, ultimately hinges on a rigorous, well-documented, and collaborative approach to method transfer. By adhering to structured protocols, leveraging high-quality reagents, and implementing a risk-based strategy informed by the specific regulatory framework, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure robust method performance across laboratories, thereby safeguarding public health and the environment.

In the realm of environmental chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the reliability of analytical data is paramount for regulatory compliance and informed decision-making. Analytical method validation provides documented evidence that a laboratory procedure is fit for its intended purpose, ensuring that results are consistent, reliable, and accurate [17]. Within the framework of method transfer between laboratories—a common practice in multi-site operations and contract research—demonstrating the equivalence of methods across different locations becomes a critical scientific and regulatory imperative [2]. At the heart of this validation process lie four core parameters: accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity. These parameters form the foundation for assessing method performance, and their rigorous evaluation is essential for successful method transfer and acceptance in regulated environments [13].

The broader thesis of this work positions these parameters within the context of validation protocols for environmental chemistry method transfer research. Unlike pharmaceutical applications, environmental analytical chemistry often lacks specific regulatory guidelines for method validation, particularly for emerging contaminants like organic micropollutants in water samples [18]. This gap places greater responsibility on researchers to adopt robust, scientifically sound validation protocols. By systematically comparing experimental approaches for establishing accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity, this guide provides a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to ensure their transferred methods generate data of known and acceptable quality.

Parameter Definitions and Experimental Protocols

Specificity

Definition and Importance: Specificity is the ability of an analytical method to unequivocally assess the target analyte in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix, such as impurities, degradants, or other matrix components [19] [17]. It is the parameter that confirms the measured response is due solely to the analyte of interest and not interferents. In qualitative terms, a specific method should generate a response only when the target analyte is present, avoiding false positives [19]. For environmental chemistry, where complex sample matrices are common, establishing specificity is particularly challenging yet crucial for accurate quantification of trace-level contaminants like pesticides or emerging organic micropollutants [18].

Standard Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a blank sample (containing all components except the target analyte) and a fortified sample (blank spiked with the analyte at a known concentration). For chromatography-based methods, this tests for interfering peaks at the retention time of the analyte [17].

- Analysis: Analyze the blank, the fortified sample, and a standard solution of the pure analyte using the identical method conditions.

- Evaluation: In the blank chromatogram or spectrum, there should be no significant response (e.g., peak) at the retention time or spectral position of the analyte. The response for the fortified sample should match that of the pure standard, confirming no matrix suppression or enhancement [17]. For methods where a blank matrix is unavailable, standard addition techniques can be employed [17].

Typical Acceptance Criteria: The blank sample should show no peak (or a signal less than a pre-defined threshold like 5% of the target analyte peak) at the same retention time as the analyte. The chromatographic resolution between the analyte peak and the closest eluting potential interferent should be greater than a specified value (e.g., 1.5 or 2.0) [20].

Linearity

Definition and Importance: Linearity refers to the ability of an analytical procedure to produce test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a given range [17]. The range is the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels of analyte for which demonstrated linearity, precision, and accuracy are achieved [19]. A linear relationship between concentration and response is fundamental for accurate quantification, as it allows for the use of a calibration curve to determine unknown sample concentrations.

Standard Experimental Protocol:

- Calibration Standards: Prepare a minimum of 6 calibration standards whose concentrations span the entire claimed working range of the method, typically from 80% to 120% of the expected concentration level for assay methods, though wider ranges are needed for impurity methods [17] [20].

- Analysis: Analyze each standard in a randomized order to minimize the effect of instrument drift.

- Data Analysis: Plot the instrumental response (e.g., peak area) against the concentration of the standard. Perform linear regression analysis to determine the slope, y-intercept, and correlation coefficient (r).

Typical Acceptance Criteria: The correlation coefficient (r) should be greater than or equal to 0.990 [17]. Additionally, the y-intercept should be statistically indistinguishable from zero, and the residual plot should show random scatter, indicating a good fit to the linear model.

Accuracy

Definition and Importance: Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and a value accepted as a true or reference value [13] [19]. It is a measure of trueness and is often reported as percent recovery. In the context of method transfer, demonstrating equivalent accuracy between the transferring and receiving laboratories is a primary objective [2].

Standard Experimental Protocols:

- Analysis of Certified Reference Materials (CRMs): The preferred method, where a CRM with a known concentration of the analyte is analyzed, and the measured value is compared to the certified value. Recovery is calculated as (Measured Value / Certified Value) * 100%.

- Spiking/Recovery Experiments: This is widely used, especially when CRMs are unavailable.

- Prepare a blank matrix (the sample without the analyte).

- Spike the analyte into the blank matrix at multiple concentration levels (e.g., low, mid, high within the linear range), typically in triplicate.

- Analyze the spiked samples and calculate the concentration using the calibration curve.

- Calculate the percent recovery for each spike level: (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) * 100% [17].

- Standard Addition Method: Suitable for complex matrices where a true blank is unavailable.

- Split the sample into multiple aliquots.

- Spike known and varying amounts of the analyte into all but one aliquot.

- Analyze all aliquots, plot the signal against the amount added, and extrapolate the line to find the original concentration in the unspiked sample [17].

Typical Acceptance Criteria: Acceptance criteria are matrix- and analyte-dependent. For pharmaceutical assays, recovery is often required to be between 98.0% and 102.0% [20]. For environmental contaminants at trace levels, recovery limits of 70-120% may be acceptable, provided they are consistent and justified [18].

Precision

Definition and Importance: Precision expresses the closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [13]. It is a measure of random error and is typically expressed as variance, standard deviation, or relative standard deviation (%RSD). Precision is evaluated at multiple levels:

- Repeatability: Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time (intra-assay precision) [13].

- Intermediate Precision: Precision within the same laboratory but on different days, with different analysts, or different equipment [13].

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories, which is the primary focus of method transfer studies [2] [13].

Standard Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous sample at a specified concentration (e.g., 100% of the target level).

- Replicate Analysis: Perform a minimum of six replicate determinations of the same sample [17]. For intermediate precision, this is repeated by a different analyst on a different day and/or with a different instrument.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and relative standard deviation (%RSD) for the replicate measurements. %RSD = (Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100%.

Typical Acceptance Criteria: For pharmaceutical assay of active ingredients, the %RSD for repeatability is typically required to be less than 1.0% [20]. For impurity methods or environmental analysis at lower concentrations, a higher %RSD (e.g., <5% or <10%) may be acceptable, depending on the level and the data quality objectives [18].

Comparative Analysis of Parameter Performance

The following tables summarize the experimental methodologies, key statistical measures, and typical acceptance criteria for the four core validation parameters, providing a direct comparison of their performance evaluation.

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Metrics for Core Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Core Objective | Standard Experimental Approach | Key Statistical Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Confirm signal is from analyte only | Analyze blank, pure analyte, and spiked matrix; check for interference [17]. | Resolution factor; visual absence of interfering peaks. |

| Linearity | Establish proportional response to concentration | Analyze ≥6 standards across the specified range [17]. | Correlation coefficient (r), slope, y-intercept, residual plot. |

| Accuracy | Measure closeness to true value | Spiked recovery experiments or analysis of Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [17]. | Percent Recovery (%) = (Measured Value / True Value) * 100. |

| Precision | Measure method variability/random error | Replicate analysis (n≥6) of a homogeneous sample [17]. | Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) = (SD / Mean) * 100. |

Table 2: Comparison of Acceptance Criteria Across Application Domains

| Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criterion (Pharmaceutical Assay) | Typical Acceptance Criterion (Environmental Chemistry) | Key Consideration in Method Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | No interference from blank; resolution >1.5-2.0 [20]. | No interference; confirmation with MS/MS recommended for OMPs [18]. | Receiving lab must demonstrate equivalent specificity in its matrix. |

| Linearity | Correlation coefficient, r ≥ 0.990 [17] [20]. | Correlation coefficient, r ≥ 0.990 is generally targeted. | Calibration curves from both labs should have statistically equivalent slopes and intercepts. |

| Accuracy | Recovery of 98-102% [20]. | Recovery of 70-120% may be acceptable for trace OMPs [18]. | The primary metric for comparative testing; results between labs must be statistically equivalent [2]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | %RSD < 1.0% for assay [20]. | %RSD < 5-10% for trace analysis, depending on the level [18]. | Receiving lab's precision must meet pre-defined criteria and be comparable to the transferring lab's [2]. |

Workflow for Method Validation and Transfer

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and interdependence of the core validation parameters within a typical method transfer workflow, from initial qualification to final acceptance.

Figure 1: Method validation and transfer workflow. This diagram outlines the critical path for validating and transferring an analytical method, highlighting the sequence in which core parameters are typically assessed. The process is iterative, and failure at the comparison stage necessitates re-evaluation of one or more foundational parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of validation protocols relies on the use of high-quality, traceable materials. The following table details key reagent solutions and their critical functions in generating reliable analytical data.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function in Validation | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Primary standard for establishing method accuracy and calibration [13]. | Must be traceable to a national metrology institute and supplied with a certificate of analysis. |

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Used to prepare calibration standards and spiking solutions for linearity, accuracy, and precision studies. | Purity should be well-characterized and documented. Stability under storage conditions must be confirmed. |

| Blank Matrix | Essential for evaluating specificity and for preparing spiked samples for accuracy (recovery) experiments [17]. | Should be free of the target analyte but otherwise representative of the sample composition (e.g., clean water, placebo). |

| Quality Control (QC) Check Samples | A stable, homogeneous sample of known concentration used to monitor method performance over time, including during transfer exercises. | Used to demonstrate intermediate precision and to ensure the receiving lab can control the method. |

| Appropriate Solvents & Reagents | Required for sample preparation, extraction, dilution, and mobile phase preparation (for chromatography). | Grade and purity must be suitable for the technique (e.g., HPLC-grade for liquid chromatography). |

The comparative analysis of the four core validation parameters—accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity—reveals a structured framework for demonstrating the reliability of an analytical method within the context of environmental chemistry method transfer. Each parameter addresses a distinct aspect of data quality: specificity ensures the identity of the measured signal, linearity defines the quantitative relationship, accuracy confirms trueness, and precision quantifies variability. The experimental protocols and acceptance criteria, while more flexible in environmental chemistry compared to the highly standardized pharmaceutical industry, must be rigorously designed and documented to provide defensible evidence of method equivalence [18]. Successful method transfer, ultimately, is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use an analytical method with the same confidence as the originating laboratory, ensuring that data integrity is maintained across different sites and instruments [2]. This is typically achieved through comparative testing, where these core parameters are evaluated in both laboratories using the same validated protocols and pre-defined statistical acceptance criteria, forming the bedrock of reliable and compliant analytical data in research and regulation.

The Growing Imperative of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) in Validation

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a significant paradigm shift to align with sustainability science, moving beyond mere analytical performance to incorporate environmental considerations throughout the method development and validation lifecycle [21]. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a systematic approach to eliminating or minimizing the environmental impact of analytical procedures while maintaining the rigorous data quality required for regulatory compliance and scientific validity. This evolution is particularly crucial in validation protocols for environmental chemistry method transfer, where the cumulative impact of analytical practices can be substantial given their widespread and repeated application across laboratories globally.

The foundational principle of GAC in validation contexts is that environmental sustainability and analytical robustness are not mutually exclusive but are complementary attributes of modern analytical methods. The traditional "take-make-dispose" linear model in analytical chemistry creates unsustainable pressures on the environment through resource-intensive processes, energy consumption, and waste generation [21]. In response, GAC frameworks provide metrics and assessment tools to guide method developers and validators toward more sustainable choices without compromising the fundamental requirements of accuracy, precision, reliability, and transferability between laboratories.

A recent evolution in this field is the emergence of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which expands the GAC framework by integrating a holistic RGB model (Red for analytical effectiveness, Green for environmental sustainability, and Blue for practical and economic feasibility) [22]. This triple-bottom-line approach balances performance metrics with ecological and practical considerations, creating a more comprehensive assessment framework for validated methods intended for transfer across research environments, particularly in environmental chemistry applications where methodological consistency and reproducibility are paramount.

Green Assessment Metrics and Method Comparison

Established Green Metric Tools for Method Validation

The implementation of GAC principles in method validation requires standardized assessment tools to quantitatively evaluate and compare the environmental performance of analytical procedures. Several validated metric systems have emerged as industry standards, each with specific focal points and scoring mechanisms that allow for objective comparison between conventional and green method alternatives.

Table 1: Green Metric Assessment Tools for Analytical Method Validation

| Metric Tool | Full Name | Assessment Focus | Scoring System | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE | Analytical Greenness Metric Approach and Software | Comprehensive environmental impact assessment | 0-1 scale (1 = greenest) | Overall method greenness evaluation |

| AGREEprep | Analytical Greenness Metric for Sample Preparation | Sample preparation environmental impact | 0-1 scale (1 = greenest) | Sample preparation step evaluation |

| BAGI | Blue Applicability Grade Index | Practical applicability and economic feasibility | Threshold score of 60+ for industrial use | Method practicality assessment |

| Complex GAPI | Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index | Holistic lifecycle impact from sampling to result | Pictorial representation with colored segments | Comprehensive method lifecycle assessment |

Recent studies applying these metrics to analytical validation have revealed significant insights. An assessment of 174 standard methods from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias using the AGREEprep metric demonstrated that 67% of methods scored below 0.2 on the 0-1 scale, highlighting the urgent need for updating official methods with greener alternatives [21]. This finding is particularly relevant for environmental chemistry method transfer, where standardized methods are frequently adopted across multiple laboratories, amplifying their environmental footprint.

Comparative Case Study: UV Spectrophotometry vs. HPLC for Fosravuconazole

A direct comparison of validated methods for pharmaceutical analysis illustrates the practical application of GAC principles in method validation. A recent study developed and validated both UV spectrophotometric and Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) methods for the determination of Fosravuconazole, with both methods validated according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [23].

Table 2: Method Comparison - UV Spectrophotometry vs. HPLC for Fosravuconazole Analysis

| Validation Parameter | UV Spectrophotometry Method | RP-HPLC Method | Green Chemistry Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Metric Scores | AGREE: Higher score; BAGI: 82.5 | AGREE: Lower score; BAGI: 72.5 | UV method demonstrates superior environmental profile |

| Solvent Consumption | Minimal solvent use | ACetonitrile/ammonium acetate buffer mobile phase | Reduced waste generation with UV method |

| Energy Requirements | Lower energy consumption | Higher energy for pump operation and column heating | UV method has lower carbon footprint |

| Practical Feasibility | Simpler, faster operation | More complex instrumentation and operation | UV method offers higher throughput |

| Industrial Applicability | Above BAGI threshold (>60) | Above BAGI threshold (>60) | Both qualify for industrial use |

The experimental data demonstrated that both methods were rigorously validated according to international standards, showing similar analytical performance in terms of accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity, thereby meeting all regulatory requirements for method validation [23]. However, the green metric assessment revealed decisive differences in environmental impact, with the UV method exhibiting a superior green profile while maintaining equivalent analytical validity. This case study exemplifies how GAC principles can be successfully integrated into analytical validation without compromising methodological rigor.

Experimental Protocols for Green Method Validation

Green HPLC Method Protocol for Pharmaceutical Analysis

The experimental protocol for the greener RP-HPLC method for Fosravuconazole analysis exemplifies how conventional chromatographic methods can be optimized for reduced environmental impact while maintaining ICH Q2(R1) compliance [23]:

Chromatographic Conditions: The method employed an isocratic approach with a reversed-phase CHROMASIL C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of Acetonitrile and 10 mM Ammonium Acetate buffer (pH adjusted to 4.5 using acetic acid) in a ratio optimized for efficient separation. A flow rate of 0.9 mL/min was established, representing a reduction from conventional flow rates of 1.0-1.5 mL/min, thereby decreasing solvent consumption.

Detection and Injection: Detection wavelength was set at 287 nm with an injection volume of 10 µL. The total run time was optimized to under 10 minutes to enhance throughput and reduce solvent consumption per analysis.

Validation Parameters: The method was systematically validated for specificity, linearity (with R² > 0.999), accuracy (recovery studies 98-102%), precision (RSD < 2%), and robustness following ICH Q2(R1) guidelines. The robustness testing included deliberate variations in mobile phase pH (±0.2 units), organic modifier ratio (±2%), and column temperature (±2°C) to establish method reliability under transfer conditions.

Green Method Validation Workflow: Integration of GAC principles with ICH Q2(R1) requirements

Green Sample Preparation (GSP) Protocol

Adapting traditional sample preparation techniques to align with Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles involves strategic optimization to reduce energy consumption and solvent use while maintaining analytical quality [21]:

Parallel Processing: Utilizing miniaturized systems that enable simultaneous processing of multiple samples significantly increases throughput and reduces energy consumption per sample. This approach makes extended preparation times less impactful on overall laboratory efficiency.

Automated Systems: Implementation of automated sample preparation systems saves time, lowers consumption of reagents and solvents, and consequently reduces waste generation. Automation also minimizes human intervention, reducing operator exposure to hazardous chemicals and potential handling errors.

Integrated Workflows: Traditional multi-step sample preparation methods are consolidated into single, continuous workflows to simplify operations while cutting down on resource use and waste production. This approach also improves the precision and accuracy of analyses by reducing material loss and handling variations.

Energy-Efficient Techniques: Replacement of conventional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction with assisted fields such as ultrasound and microwaves enhances extraction efficiency and accelerates mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy. These approaches are particularly suited to miniaturized sample preparation that additionally minimizes sample size and solvent consumption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of green analytical methods requires specific reagents, materials, and instrumentation optimized for both analytical performance and environmental sustainability. The following toolkit details essential components for establishing green analytical methods in validation laboratories.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Tool/Reagent | Function in GAC | Environmental Advantage | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHROMASIL C18 Column | Stationary phase for reversed-phase separation | Enables lower flow rates and reduced solvent consumption | HPLC/UHPLC method development |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Organic mobile phase component | Recyclable waste streams; enabled by method optimization | Chromatographic separations |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | Aqueous mobile phase component for pH control | Less hazardous than traditional phosphate buffers | Bioanalytical method development |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Direct concentration measurement without separation | Eliminates solvent consumption entirely | Pharmaceutical quality control |

| Automated Sample Preparation System | Standardized reagent dispensing and handling | Reduces solvent consumption and human exposure | High-throughput analysis laboratories |

| Miniaturized Extraction Devices | Small-scale sample preparation | Dramatically reduces solvent volumes | Environmental trace analysis |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials represents only one component of comprehensive GAC implementation. The Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) tool specifically assesses the practical feasibility and economic aspects of analytical methods, with scores above 60 indicating suitability for industrial implementation [23]. This practical assessment is crucial for method transfer in environmental chemistry, where methods must balance sustainability with real-world applicability across different laboratory environments.

Green Metric Assessment and Visualization Framework

The quantitative assessment of method greenness employs multiple complementary metrics to provide a comprehensive sustainability profile. The RGB model underlying White Analytical Chemistry offers a balanced evaluation framework that aligns analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical/economic feasibility (Blue) [22].

WAC RGB Assessment Model: Integrating performance, environmental, and practical metrics

The implementation of this framework in analytical validation provides several strategic advantages for environmental chemistry method transfer. First, it enables quantitative comparison between alternative methods using standardized metrics. Second, it identifies specific aspects of methods that require optimization to improve sustainability. Third, it provides documented evidence of environmental consideration for regulatory submissions and sustainability reporting. Finally, it facilitates more informed method selection decisions when transferring methodologies between laboratories with different equipment and expertise levels.

Recent applications of this framework demonstrate its practical utility. In the development of green RP-HPLC methods for pharmaceutical compounds in human plasma, a WAC-assisted AQbD (Analytical Quality by Design) strategy led to a validated, sustainable, and cost-effective procedure with an excellent overall WAC score [22]. This approach systematically integrates green considerations throughout the method development lifecycle rather than as an afterthought, resulting in methods that are inherently more sustainable without compromising performance characteristics.

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Barriers to GAC Adoption in Validation Frameworks

Despite the clear benefits and emerging tools, significant barriers impede the widespread adoption of GAC principles in analytical method validation and transfer. Analytical chemistry largely operates under a weak sustainability model, which assumes that natural resources can be consumed and waste generated as long as technological progress and economic growth compensate for the environmental damage [21]. This mindset prioritizes performance and economic considerations over environmental impacts, creating resistance to changing established methods.

The regulatory landscape presents another substantial challenge. A comprehensive assessment of 174 standard methods from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias revealed that 67% scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale, where 1 represents the highest possible greenness score [21]. This demonstrates that many official methods still rely on resource-intensive and outdated techniques, creating institutional barriers to implementing greener alternatives that may not yet be recognized in standardized protocols.

The rebound effect presents a more subtle but equally important challenge in green analytical chemistry. This phenomenon occurs when efforts to reduce environmental impact lead to unintended consequences that offset or even negate the intended benefits [21]. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method that uses minimal solvents might lead laboratories to perform significantly more extractions than before, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated. Similarly, automation in analysis can lead to over-testing, where analyses are performed more frequently than necessary simply because the technology allows it.

Future Perspectives: Green Financing and Method Transformation

Overcoming these challenges requires coordinated action across multiple stakeholders in the analytical chemistry community. Regulatory agencies have a critical role in driving the adoption of sustainable practices by establishing clear timelines for phasing out methods that score low on green metrics and integrating these metrics into method validation and approval processes [21]. Additionally, financial incentives for early adopters, such as tax benefits, grants, or reduced regulatory fees, can serve as powerful motivators for change.

The proposed Green Financing for Analytical Chemistry (GFAC) model represents a promising approach to dedicated funding designed to promote innovations aligned with GAC and WAC goals [22]. This funding mechanism could bridge critical gaps in current practices by supporting the development and commercialization of green analytical technologies, which often struggle to reach the market despite promising academic research.

The transition from linear to circular analytical chemistry frameworks requires unprecedented collaboration between manufacturers, researchers, routine laboratories, and policymakers [21]. Breaking down traditional silos and building cooperative networks is crucial to accelerate the shift toward a waste-free and resource-efficient sector. Such collaborative efforts will not only streamline innovation but also ensure that sustainable practices are widely adopted and effectively implemented across the environmental chemistry community.

For method transfer specifically, the implementation of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and Design of Experiment (DoE) approaches provides a systematic methodology for building sustainability into methods from their initial development rather than as a retrospective addition [22]. This proactive approach facilitates more robust and transferable methods while simultaneously optimizing their environmental performance, creating a new paradigm where green attributes are fundamental quality parameters rather than optional additions.

Executing a Successful Transfer: Protocols, Practices, and Green Integration

In the field of environmental chemistry and pharmaceutical development, the transfer of analytical methods between laboratories is a critical process for ensuring consistent and reliable data. Selecting the appropriate transfer protocol is fundamental to maintaining data integrity, regulatory compliance, and operational efficiency. This guide provides an objective comparison of the three primary methodological approaches for analytical method transfer: Comparative Testing, Co-validation, and Revalidation. Framed within the context of validation protocols for environmental chemistry method transfer research, this article equips scientists and drug development professionals with the data and criteria necessary to select the optimal strategy for their specific projects.

Understanding the Core Transfer Protocols

Analytical method transfer is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory (RL) to use an analytical method that originated in a transferring laboratory (TL), ensuring the RL can perform the procedure with equivalent accuracy, precision, and reliability [2]. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <1224> formally recognizes several transfer approaches [24] [25].

- Comparative Testing involves both the transferring and receiving laboratories analyzing the same set of homogeneous samples. The results are then statistically compared to demonstrate equivalence [2] [3]. This is the most commonly used strategy [3].

- Co-validation occurs when the receiving laboratory participates in the initial validation of the analytical procedure alongside the transferring laboratory. This parallel execution of validation and transfer is particularly advantageous when project timelines are constrained [24] [25].

- Revalidation requires the receiving laboratory to perform a complete or partial revalidation of the already-validated method. This approach is common when the transfer was not planned during the initial validation or when minor changes have been made to the method [24] [26].

The choice between these protocols depends on multiple factors, including timeline, method maturity, and resource availability. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each approach.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Analytical Method Transfer Protocols

| Feature | Comparative Testing | Co-validation | Revalidation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Both labs test identical samples; results are statistically compared for equivalence [2]. | Simultaneous method validation and receiving lab qualification [25]. | Complete or partial revalidation of the method by the receiving lab [24]. |

| Typical Use Case | Well-established, validated methods; similar lab capabilities [2]. | New methods; accelerated development timelines; methods designed for multi-site use [24] [25]. | Transfer to a lab with significantly different conditions; substantial method changes; TL unavailable [24] [26]. |

| Time Efficiency | Sequential process (validation, then transfer); can be time-consuming [25]. | Parallel process (validation & transfer together); can reduce timelines by over 20% [25]. | Highly rigorous and resource-intensive; can be lengthy [2]. |

| Resource Intensity | Moderate; requires careful sample preparation and statistical analysis [2]. | High collaboration; requires early and deep involvement from the RL [25]. | Very high; the RL performs a full or partial validation suite [2]. |

| Key Advantage | Well-understood, widely accepted by regulators [3]. | Streamlines documentation; enhances method knowledge at RL; builds method robustness from the start [25]. | Ensures method suitability for the RL's specific environment and equipment [26]. |

| Primary Challenge | Requires highly homogeneous and stable samples [2]. | Risk associated with transferring a not-yet-fully-validated method [25]. | Most demanding approach in terms of workload and scientific justification [2]. |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

A direct comparison from an industrial case study provides quantitative insight into the efficiency of these protocols. A pilot project at Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) transitioning from a traditional comparative testing model to a co-validation model demonstrated significant benefits [25].

Table 2: Performance Metrics from a BMS Pilot Study on Method Transfer [25]

| Metric | Comparative Testing Model | Co-validation Model | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project Time | 13,330 hours | 10,760 hours | -19.3% |

| Process Duration (per method) | ~11 weeks | ~8 weeks | -27.3% |

| Methods Requiring Comparative Testing | 60% | 17% | -71.7% |

The data shows that co-validation can drastically reduce the number of methods requiring direct comparative testing, resulting in significant time and resource savings. The success of co-validation, however, is predicated on the robustness of the method, which must be systematically evaluated during development using approaches like Quality by Design (QbD) [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Implementation

Protocol for Comparative Testing

A robust comparative testing protocol should include [2] [3]:

- Sample Selection: A sufficient number of homogeneous samples (e.g., from the same production lots) are selected to provide a statistically sound comparison.

- Analysis: Both the TL and RL analyze the samples independently using the same validated method.

- Statistical Comparison: Results are compared using pre-defined statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, F-tests, equivalence testing) to evaluate inter-laboratory precision.

- Acceptance Criteria: Success is determined by meeting pre-defined acceptance criteria for the results, such as a pre-determined level of statistical equivalence.

Protocol for Co-validation

The co-validation process integrates the RL into the validation lifecycle [25]:

- Team Formation: A joint team with representatives from both TL and RL is established.

- Protocol Development: A single, harmonized validation protocol is created, outlining the roles and responsibilities of both laboratories.

- Parallel Execution: Both labs simultaneously perform the validation studies, with the RL's data contributing directly to the assessment of method reproducibility.

- Unified Reporting: Results are compiled into a single validation report, eliminating the need for separate transfer protocols and reports.

Protocol for Revalidation

Revalidation, whether partial or full, follows a structured assessment [26]:

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate the impact of the change (e.g., new equipment, different sample matrix) on method performance.

- Scope Definition: Identify which validation parameters (e.g., accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range) need to be reassessed.

- Experimental Execution: The RL performs the necessary validation studies as if the method were new.

- Data Comparison: The new validation data is compared against the original validation data and acceptance criteria to confirm the method's performance is maintained.

Decision Framework and Workflow

Selecting the right transfer strategy is a systematic process. The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points based on method status, timeline, and laboratory readiness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful method transfer relies on high-quality, traceable materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in ensuring transfer success.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Transfer

| Reagent/Material | Function | Criticality for Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides the benchmark for quantifying analytes and calibrating instruments. | High: Essential for establishing accuracy and linearity across both laboratories. Must be traceable and from a qualified source [2] [3]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Mobile Phases | Used in sample preparation and as the carrier phase in chromatographic separations. | High: Purity and consistency are vital for achieving reproducible retention times, baseline stability, and detector response [2]. |

| Well-Characterized Samples | Homogeneous samples from identical lots (e.g., drug substance, environmental matrix). | High for Comparative Testing: The foundation for a statistically sound comparison between labs. Sample homogeneity is paramount [2] [3]. |

| System Suitability Test Mixtures | Verifies that the analytical system is performing adequately at the time of the test. | High: A pass/fail checkpoint that ensures the method is operating as validated in the receiving lab's environment before transfer data is collected [3] [26]. |

The strategic selection of an analytical method transfer protocol is a cornerstone of data integrity in research and quality control. Comparative Testing remains a robust and widely applicable choice for stable methods. Co-validation offers a powerful pathway for accelerating development, particularly for breakthrough therapies and new methods, by leveraging parallel execution and enhanced collaboration. Revalidation provides a comprehensive, albeit resource-intensive, solution for qualifying a method in a significantly different operational environment. By applying the quantitative data, experimental protocols, and decision framework presented in this guide, researchers and scientists can make informed, defensible choices that ensure regulatory compliance, optimize resource utilization, and safeguard the reliability of their analytical results.

In the dynamic landscape of environmental analytical chemistry, the integrity and consistency of data are paramount. Analytical method transfer is a documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory (RL) to use an analytical procedure that originated in another laboratory (transferring laboratory, or TL), ensuring that the RL can perform the method with equivalent accuracy, precision, and reliability [2]. This process is not merely a logistical exercise but a scientific and regulatory imperative, particularly when methods for detecting organic micropollutants and other environmental contaminants are moved between development and commercial testing facilities or between different contract research organizations [18].

A poorly executed method transfer can lead to significant issues, including delayed project timelines, costly retesting, regulatory non-compliance, and ultimately, a loss of confidence in environmental monitoring data [2]. For researchers and scientists in drug development and environmental chemistry, understanding and implementing a robust roadmap for method transfer is fundamental to maintaining data integrity. This guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework—from initial planning to final reporting—ensuring a seamless, compliant, and defensible transfer of analytical methods.

Comparative Analysis of Method Transfer Approaches

Selecting the appropriate transfer strategy is a critical first step, dictated by the method's complexity, its validation status, the experience of the receiving lab, and the specific project requirements. There is a notable lack of specific guidelines for environmental analytical chemistry, which makes a scientifically sound approach even more critical [18]. The following table compares the most common approaches as defined by regulatory guidance and industry best practices [3] [27] [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Method Transfer Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Core Principle | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing | Both laboratories analyze identical samples from the same lots; results are statistically compared against pre-defined acceptance criteria [3] [28]. | Well-established, validated methods; laboratories with similar equipment and capabilities [2]. | Requires homogeneous, stable samples; relies on robust statistical analysis and clear acceptance criteria [3]. |

| Co-validation | The RL participates in the method validation study, often for assessing inter-laboratory precision (reproducibility) [3] [28]. | New methods or methods being established for multi-site use from the outset [2]. | Demands close collaboration and harmonized protocols from the beginning of the method's life cycle [14]. |

| Partial or Full Revalidation | The RL performs a full or partial revalidation of the method [3] [28]. | Transfers to a lab with significantly different equipment; when the TL is unavailable; or for high-risk methods [2]. | Most resource-intensive approach; essentially treats the method as new to the receiving site [27]. |

| Transfer Waiver | The formal transfer process is waived based on strong scientific justification [27] [2]. | Receiving lab has proven proficiency with highly similar methods; transfer of simple, robust pharmacopoeial methods [28]. | Requires robust documentation and risk assessment; subject to high regulatory scrutiny [2]. |

A Detailed Roadmap for Successful Method Transfer

A successful analytical method transfer is a phased process that hinges on meticulous planning, clear communication, and rigorous documentation. The following workflow and detailed breakdown outline the essential activities from initiation to closure.

Diagram 1: Analytical method transfer workflow.

Phase 1: Pre-Transfer Planning and Assessment

This foundational phase determines the entire project's trajectory and potential for success.

- Define Scope and Objectives: Clearly articulate why the method is being transferred and what constitutes a successful outcome. This includes defining specific acceptance criteria for key performance parameters like precision, accuracy, and sensitivity [2].

- Form Cross-Functional Teams: Designate leads and team members from both the TL and RL, including representatives from Analytical Development, QA/QC, and Operations. Clear points of contact are essential for robust communication [3] [2].

- Gather Method Documentation: The TL must provide the RL with a comprehensive transfer package. This includes the analytical procedure, method validation report, method development report, known issues and resolutions, sample chromatograms, and a list of critical equipment and reagents [3] [27].

- Conduct Gap and Risk Analysis: Compare equipment, software, reagents, and personnel expertise between the two labs. Identify potential discrepancies and perform a formal risk assessment to pinpoint challenges (e.g., complex method steps, unique equipment) and develop mitigation strategies [2].

- Select Transfer Approach and Develop Protocol: Based on the risk assessment, select the most appropriate strategy from Table 1. A detailed, approved transfer protocol is the cornerstone of the entire process. It must specify method details, responsibilities, experimental design, predefined acceptance criteria, and the statistical analysis plan [3] [27] [2].

Phase 2: Execution and Data Generation

This phase involves the practical implementation of the approved protocol.

- Personnel Training: The RL analysts must be thoroughly trained by the TL. This may involve on-site sessions to convey tacit knowledge not captured in the written procedure, such as practical tips for handling or instrument operation [3] [28]. All training must be documented.

- Equipment and Reagent Readiness: Verify that all necessary instruments at the RL are properly qualified, calibrated, and maintained. Ensure the use of traceable and qualified reference standards and reagents [27] [2].

- Sample Preparation and Analysis: Prepare homogeneous, representative samples (e.g., spiked samples, production batches, placebo) for comparative testing. Both labs then perform the analytical method strictly as outlined in the approved protocol [2].

- Meticulous Documentation: All raw data, instrument printouts, calculations, and any observations or deviations must be meticulously recorded in real-time to ensure data integrity and traceability [2].

Phase 3: Data Evaluation and Reporting

The final phase involves determining the success of the transfer and formally documenting the outcome.

- Data Compilation and Statistical Analysis: Collect all data from both laboratories and perform the statistical comparison (e.g., t-tests, F-tests, equivalence testing) as pre-defined in the protocol [2].

- Evaluation Against Acceptance Criteria: Compare the results, including parameters like system suitability, precision, and accuracy, against the protocol's pre-defined acceptance criteria [3]. The transfer is successful only if all criteria are met.

- Investigate Deviations: Any deviation from the protocol or out-of-specification results must be thoroughly investigated. The root cause must be identified, documented, and justified [3] [2].

- Draft and Approve Final Report: A comprehensive transfer report is generated, summarizing all activities, results, statistical analysis, deviations, and the final conclusion on whether the method was successfully transferred. This report requires formal approval by both laboratories and the Quality Assurance unit [3] [27] [2].

Experimental Protocols and Acceptance Criteria

The experimental design and success criteria for a method transfer must be tailored to the specific method and its intended use.

Defining the Experimental Design

For the most common approach, comparative testing, the experiment involves both the TL and RL analyzing a predetermined number of samples. As per industry standards, this typically includes a minimum of one batch for an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or one batch each for the lowest and highest strengths of a drug product [27]. The samples should be homogeneous and from the same lot to ensure a fair comparison. Testing often encompasses all critical tests defined in the method, such as assay, related substances, and dissolution [27].

Establishing Acceptance Criteria

Defining clear, justified acceptance criteria is a critical component of the transfer protocol. These criteria are often based on the method's validation data and historical performance, particularly its reproducibility [3] [28]. The following table provides examples of typical acceptance criteria for common test types.

Table 2: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Analytical Method Transfer [28]

| Test Type | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | Positive (or negative) identification obtained at the receiving site. | Comparison of results (e.g., retention time, spectrum) against reference standard. |

| Assay | Absolute difference between the sites' results is not more than 2-3%. | Requires a sufficient number of replicate determinations to ensure statistical power. |

| Related Substances (Impurities) | Absolute difference criteria vary with impurity level. For spiked impurities, recovery may be set at 80-120%. | For low-level impurities, more generous criteria are used. Samples may be spiked with known impurities. |

| Dissolution | Absolute difference in mean results: NMT 10% at <85% dissolved; NMT 5% at >85% dissolved. | Testing should cover multiple time points to profile the entire dissolution curve. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of a method transfer is contingent on the quality and consistency of the materials used. The following table details key reagents and materials critical for success.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Transfer

| Item | Critical Function | Considerations for Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serves as the benchmark for quantifying the analyte and confirming method identity and performance. | Must be properly qualified with supporting documentation (e.g., Certificate of Analysis). Traceability to a primary standard is key [27]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | The heart of HPLC/GC methods; critical for achieving required separation, retention, and peak shape. | The protocol must specify the manufacturer and product number. Having a spare column from the same manufacturing lot is ideal [27]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Essential for preparing mobile phases, standards, and samples. Impurities can cause high background noise or interference. | Grades and suppliers should be consistent with those used during method development and validation [27] [2]. |

| Critical Biological Reagents | For ligand binding assays (e.g., for biomarker studies); these define method specificity and sensitivity. | Includes antibodies, antigens, and enzymes. Transfer is complex due to lot-to-lot variability; requires careful planning and characterization [14]. |

| Stable, Homogeneous Samples | Provides the medium for comparing laboratory performance. | Using expired samples, spiked samples, or experimental batches can avoid depleting commercial stock [27]. Sample homogeneity is non-negotiable. |

A successful analytical method transfer is a systematic and documented process that verifies a receiving laboratory's competency to execute an analytical procedure without compromising its validated state. In environmental chemistry, where methods for organic micropollutants often lack specific regulatory guidelines, a rigorous and scientifically sound approach is not just best practice—it is a necessity for generating defensible data [18]. By adhering to a structured roadmap that emphasizes comprehensive pre-transfer planning, robust experimental design with clear acceptance criteria, and meticulous documentation, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure data integrity, maintain regulatory compliance, and ultimately support sound decision-making for environmental and public health.