Evaluating the Chemical Capabilities of Large Language Models in Environmental Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of Large Language Models (LLMs) applied to environmental chemistry, a critical field addressing pollution, water management, and climate change.

Evaluating the Chemical Capabilities of Large Language Models in Environmental Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of Large Language Models (LLMs) applied to environmental chemistry, a critical field addressing pollution, water management, and climate change. We explore the foundational knowledge of general-purpose and domain-adapted LLMs, assessing their core chemical reasoning abilities. The review systematically examines methodological approaches—from prompt engineering and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to the emerging potential of multi-agent systems—for deploying these models in active research environments. We critically analyze major challenges, including model hallucinations, safety risks with chemical procedures, and susceptibility to environmental distractions, while proposing optimization strategies. Finally, we survey the evolving landscape of specialized benchmarks and performance metrics necessary for validating LLMs against human expertise, offering a forward-looking perspective for researchers and professionals in biomedical and environmental fields.

Assessing Core Knowledge and Reasoning in Environmental Chemistry

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into chemical research represents a paradigm shift, offering the potential to accelerate discovery and integrate computational and experimental workflows [1]. However, their application in high-stakes domains like environmental chemistry demands rigorous evaluation to ensure reliability, safety, and true utility beyond superficial knowledge retrieval. This guide objectively benchmarks the performance of leading LLMs against human expertise and other alternatives, identifying critical capability gaps through analysis of current experimental data and evaluation frameworks. Establishing robust benchmarking methodologies is essential to transform LLMs from automated oracles into trustworthy partners in scientific research [1].

Performance Comparison: LLMs vs. Human Expertise

Quantitative benchmarking reveals that the most advanced LLMs can rival or even surpass human experts in broad chemical knowledge, though significant weaknesses persist in specific areas.

The ChemBench framework, comprising over 2,700 question-answer pairs, provides a comprehensive assessment of chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities. Evaluation of leading open- and closed-source LLMs yielded a striking finding: the best models, on average, outperformed the best human chemists involved in the study [2] [3]. This suggests that state-of-the-art models have achieved remarkable mastery across a substantial portion of the chemical domain.

Table 1: Comparative Performance on ChemBench Evaluation

| Model Type | Average Performance | Key Strengths | Critical Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best LLMs | Outperformed best human chemists [2] | Broad chemical knowledge, information synthesis | Basic tasks, overconfident predictions [2] |

| Human Chemists | Lower than best LLMs on average [2] | Critical reasoning, intuition, safety awareness | Recall speed, volume of information |

| Specialized Models (e.g., EnvGPT) | 92.06% accuracy on EnviroExam [4] | Domain-specific reasoning, factual accuracy | Generalization outside trained domain |

| Tool-Augmented LLMs | Significant improvements with RAG [5] | Access to current data, precise calculations | Dependency on tool quality, integration complexity |

Performance in Environmental Domains

In environmentally-focused evaluations, specialized models demonstrate the value of domain adaptation. EnvGPT, an 8-billion-parameter model fine-tuned on environmental science data, achieved 92.06% accuracy on the independent EnviroExam benchmark—surpassing the parameter-matched LLaMA-3.1-8B baseline by approximately 8 percentage points and rivaling the performance of much larger general models [4].

However, general foundation models show considerable limitations when applied to specialized environmental tasks. In water and wastewater management, for instance, these models exhibit error rates exceeding 30% when retrieving technical protocols or providing operational recommendations [6]. Similarly, on the ESGenius benchmark covering environmental, social, and governance topics, state-of-the-art models achieved only 55-70% accuracy in zero-shot settings, highlighting the challenge of interdisciplinary environmental contexts [5].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking LLMs

Standardized evaluation methodologies are crucial for meaningful performance comparisons. This section details the key experimental frameworks used to generate the comparative data.

The ChemBench Framework

ChemBench employs an automated framework for evaluating chemical knowledge and reasoning against chemist expertise [2] [3]. The protocol involves:

- Corpus Curation: A diverse set of 2,788 question-answer pairs compiled from multiple sources, including 1,039 manually generated and 1,749 semi-automatically generated questions [2].

- Skill Classification: Questions are categorized by required skills (knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition) and difficulty levels [2].

- Question Types: Mix of multiple-choice (2,544) and open-ended questions (244) to reflect real-world chemistry education and research [2].

- Specialized Encoding: Implements special treatment for scientific information by encoding semantic meaning of chemicals, units, or equations using specialized tags (e.g., SMILES strings enclosed in [STARTSMILES][\ENDSMILES] tags) [2].

- Human Benchmarking: 19 chemistry experts evaluated on a subset of the benchmark (ChemBench-Mini, 236 questions) to establish human performance baselines, with some allowed to use tools like web search for realistic assessment [2].

Domain-Specific Evaluation Protocols

Environmental Science Benchmarking (EnvBench)

The EnvBench framework comprises 4,998 items assessing analysis, reasoning, calculation, and description tasks across five core environmental themes: climate change, ecosystems, water resources, soil management, and renewable energy [4]. The evaluation uses LLM-assigned scores for relevance, factuality, completeness, and style on a standardized scale [4].

ESG Evaluation (ESGenius Protocol)

ESGenius implements a rigorous two-stage evaluation protocol [5]:

- Zero-Shot Testing: Models answer 1,136 multiple-choice questions without prior context.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Evaluation: Models access ESGenius-Corpus of 231 authoritative ESG documents to ground their responses. This protocol tests both inherent knowledge and ability to leverage external information.

Critical Capability Gaps and Limitations

Despite impressive performance in many areas, LLMs exhibit consistent critical gaps that limit their reliability in chemical research applications.

Fundamental Reasoning Deficiencies

Even models that outperform humans on average struggle with some basic tasks and provide overconfident predictions [2]. This combination of competency gaps with unwarranted confidence presents particular safety concerns in chemical research, where errors can have dangerous consequences [1].

Environmental Application Challenges

In water management applications, foundation models frequently hallucinate technical procedures, fail to consider multiple objectives in complex scenarios, misquote standards critical for policy analysis, and overlook essential materials or chemicals databases [6]. These limitations persist despite prompt engineering efforts, indicating fundamental knowledge gaps.

Safety and Precision Concerns

Chemistry presents unique safety considerations where hallucinations aren't just inconvenient but can be dangerous [1]. Additionally, the field requires exact numerical reasoning where small errors in molecular representation or spectral interpretation can completely change results [1]. Current LLMs lack native capability for this precision without tool augmentation.

Table 2: Critical Gap Analysis in Environmental Chemistry Applications

| Capability Category | Performance Status | Specific Deficiencies | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Knowledge | Error-prone (>30% error rate) [6] | Hallucination of procedures, misquoted standards | Safety hazards, incorrect research directions |

| Multi-objective Reasoning | Limited [6] | Failure to consider competing factors in complex scenarios | Suboptimal environmental decisions |

| Numerical Precision | Deficient without tools [1] | Inaccurate chemical calculations, property predictions | Invalid experimental results, replication failures |

| Interdisciplinary Context | Moderate (55-70% accuracy) [5] | Difficulty integrating chemical, environmental, regulatory knowledge | Incomplete assessment of environmental impacts |

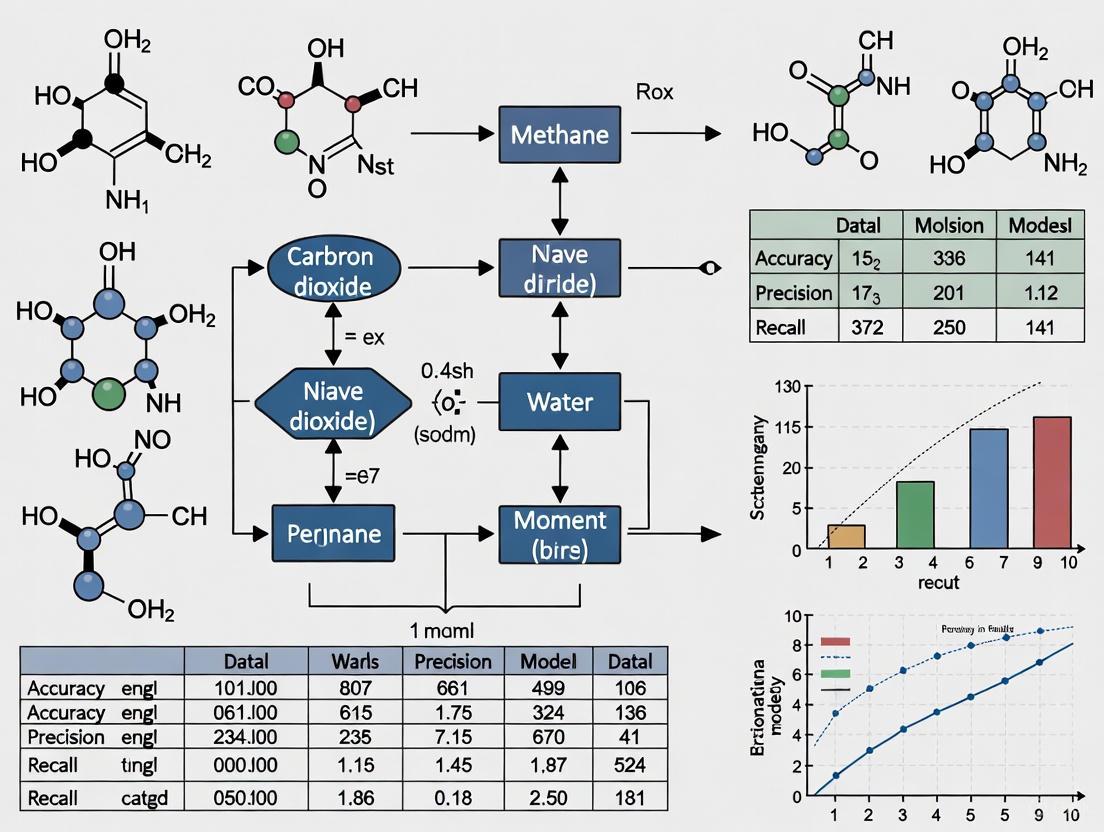

Visualization of LLM Evaluation Workflows

Chemical Capability Benchmarking Methodology

Active vs. Passive LLM Environments for Chemistry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The effective implementation and evaluation of LLMs in chemical research requires specialized "research reagents" - tools and frameworks that enable rigorous assessment and application.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LLM Evaluation in Chemistry

| Tool/Framework | Type | Primary Function | Domain Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Evaluation Framework | Standardized testing of chemical knowledge and reasoning against human experts | Chemistry-specific |

| EnvBench [4] | Benchmark Dataset | Assess analysis, reasoning, calculation, and description in environmental science | Environmental Science |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [5] | Augmentation Method | Ground LLM responses in authoritative, up-to-date sources | General with domain adaptation |

| Special Scientific Encoding [2] | Processing Technique | Handle domain-specific notations (e.g., SMILES, equations) with semantic understanding | Chemistry-specific |

| Knowledge Graphs [6] | Augmentation Method | Structure information into entity-relationship triples for improved reasoning | General with domain adaptation |

| Tool Augmentation [1] | Integration Framework | Connect LLMs to external tools for calculations, data retrieval, and instrument control | General with domain-specific tools |

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into scientific research has created an urgent need for robust, domain-specific evaluation frameworks. In environmental chemistry, where inaccurate information can lead to serious safety and environmental consequences, establishing reliable benchmarks is particularly crucial. While general-purpose LLMs demonstrate impressive capabilities, their performance in specialized scientific domains varies significantly. Traditional benchmarks like Ceval and MMLU often fail to cover environmental science content in depth, limiting development of specialized language models in this domain [7]. This comparison guide examines current evaluation methodologies, benchmarks their results, and provides detailed experimental protocols to help researchers objectively assess LLM capabilities in environmental chemistry domains.

Established Evaluation Frameworks and Benchmarks

EnviroExam: A Comprehensive Environmental Science Benchmark

Design Philosophy and Scope: EnviroExam represents a comprehensive evaluation framework specifically designed to assess LLM knowledge in environmental science. Its design philosophy is inspired by core course assessments from top international universities, treating general AI as undergraduate students and vertical domain LLMs as graduate students. The benchmark covers 42 core environmental science courses from undergraduate, master's, and doctoral programs, excluding general, duplicate, and practical courses from an initial set of 141 courses [7].

Data Collection and Composition: The dataset was constructed by generating initial draft questions using GPT-4 and Claude, combined with customized prompts, followed by manual refinement and proofreading. From an initial set of 1,290 multiple-choice questions, the final benchmark contains 936 valid questions divided into 210 questions for development and 726 for testing [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Configuration: Evaluation performed using OpenCompass (v2.1.0) with parameters: maxoutlen=100, maxseqlen=4096, temperature=0.7, top_p=0.95

- Testing Methodology: Both 0-shot and 5-shot tests conducted on 31 open-source LLMs

- Scoring Method: Accuracy used as primary metric with comprehensive composite index accounting for coefficient of variation

- Validation: Manual expert review of all questions and responses

Table 1: EnviroExam Performance Results for Selected LLMs

| Model | Creator | Parameters | 0-shot Accuracy | 5-shot Accuracy | Pass/Fail (5-shot) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama-3-70B-instruct | Meta | 70B | 78.3% | 85.7% | Pass |

| Mixtral-8x7B-instruct | Mistral AI | 56B | 75.1% | 82.9% | Pass |

| Qwen-14B-chat | Alibaba Cloud | 14B | 72.8% | 79.4% | Pass |

| Baichuan2-13B-chat | Baichuan AI | 13B | 68.5% | 74.2% | Pass |

| ChatGLM3-6B | THUDM | 6B | 63.1% | 68.9% | Fail |

ChemBench: Evaluating Chemical Knowledge and Reasoning

Framework Overview: ChemBench provides an automated framework for evaluating chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities of state-of-the-art LLMs against human chemist expertise. The benchmark consists of 2,788 question-answer pairs compiled from diverse sources (1,039 manually generated and 1,749 semi-automatically generated) [2].

Domain Coverage and Question Types: The corpus measures reasoning, knowledge, and intuition across undergraduate and graduate chemistry curriculum topics, including both multiple-choice (2,544 questions) and open-ended questions (244 questions). Questions are classified by required skills: knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition, or combinations, with difficulty annotations [2].

Key Findings: Evaluation results revealed that the best models, on average, outperformed the best human chemists in the study, though models struggled with some basic tasks and provided overconfident predictions [2].

Table 2: ChemBench Evaluation Dimensions

| Skill Category | Description | Example Task Types | Human Expert Accuracy | Top LLM Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Recall of chemical facts | Element properties, reaction rules | 84% | 89% |

| Reasoning | Multi-step problem solving | Synthesis planning, mechanism elucidation | 76% | 82% |

| Calculation | Numerical computations | Stoichiometry, concentration calculations | 71% | 68% |

| Intuition | Chemical pattern recognition | Reactivity prediction, molecular stability | 69% | 73% |

| Combined | Integration of multiple skills | Experimental design, data interpretation | 72% | 79% |

Specialized Methodologies for Environmental Chemistry Domains

Active vs. Passive Evaluation Environments

A crucial distinction in LLM evaluation for chemical domains lies between "passive" and "active" environments:

Passive Environments: LLMs answer questions or generate text based solely on training data, risking hallucination of synthesis procedures or providing outdated information [1].

Active Environments: LLMs interact with databases, specialized software, and laboratory equipment to gather real-time information and take concrete actions. This approach transforms the LLM from an information source to a reasoning engine that coordinates different tools and data sources [1].

The ChemCrow system exemplifies the active approach, integrating 18 expert-designed tools and using GPT-4 as the LLM engine to accomplish tasks across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design [8].

Tool-Augmented Evaluation Methodology

System Architecture: ChemCrow operates by prompting an LLM with specific instructions about tasks and desired format, providing the model with tool names, descriptions, and input/output expectations. The system follows the Thought, Action, Action Input, Observation reasoning format [8].

Experimental Workflow:

- Task Initiation: User provides natural language prompt (e.g., "Plan and execute the synthesis of an insect repellent")

- Reasoning Loop:

- Thought: Model reasons about current state and relevance to final goal

- Action: Model selects appropriate tool from available options

- Action Input: Model provides necessary inputs for the tool

- Observation: Program executes function and returns result to model

- Iteration: Process continues until final answer is reached

- Validation: Results verified through both automated metrics and expert assessment

Safety-Centric Evaluation Criteria

Unique Safety Considerations: Chemistry applications present unique safety challenges where hallucinations aren't just inaccurate but potentially dangerous. If an LLM suggests mixing incompatible chemicals or provides incorrect synthesis procedures, serious safety hazards or environmental risks can result [1].

Precision Requirements: Environmental chemistry requires exact numerical reasoning, an area where LLMs naturally struggle. Small errors in molecular representation or concentration calculations can completely change results and lead to hazardous outcomes [1].

Multimodal Challenges: Chemical research inherently works with text procedures, molecular structures, spectral images, and experimental data simultaneously. Most LLMs are primarily text-based, presenting particular challenges for comprehensive chemical evaluation [1].

Performance Comparison Across Environmental Chemistry Domains

Knowledge Retrieval vs. Reasoning Capabilities

Current evaluations reveal significant performance variations between simple knowledge retrieval and complex reasoning tasks:

Knowledge-intensive Tasks: LLMs generally excel at factual recall of chemical properties, environmental regulations, and established scientific principles. For example, in the EnviroExam benchmark, 61.3% of tested models passed 5-shot tests while 48.39% passed 0-shot tests [7].

Reasoning-intensive Tasks: Models demonstrate more variable performance on tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, such as predicting environmental fate of chemicals, designing remediation strategies, or interpreting complex spectral data. The coefficient of variation (CV) introduced in EnviroExam helps quantify this performance dispersion across different topic areas [7].

Domain-Specific Performance Patterns

Table 3: Performance Across Environmental Chemistry Subdomains

| Subdomain | Key Evaluation Metrics | Top Performing Models | Critical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Monitoring | Detection limit prediction, sensor data interpretation | GPT-4, Claude 3 | Struggles with low-concentration quantification |

| Fate & Transport | Biodegradation prediction, bioavailability assessment | ChemCrow, tool-augmented LLMs | Limited by training data recency |

| - Remediation Design | Treatment efficiency, cost estimation | GPT-4, Llama-3-70B | Overconfidence in novel scenarios |

| Toxicity Assessment | QSAR prediction, ecological risk | Specialist models (GAMES) | Hallucination of safety data |

| Green Chemistry | Atom economy, waste minimization | Claude 3, Mixtral | Difficulty balancing multiple objectives |

| Regulatory Compliance | Standard interpretation, reporting | GPT-4, domain-tuned models | Inconsistent citation of sources |

The Human-AI Collaboration Paradigm

Evaluation frameworks must account for emerging human-AI collaboration patterns, where LLMs augment rather than replace human expertise. In one demonstrated example, ChemCrow successfully collaborated with human researchers to discover a novel chromophore by training machine learning models to screen candidate libraries, with the proposed molecule subsequently synthesized and confirming the desired properties [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LLM Evaluation in Environmental Chemistry

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Environmental Chemistry Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| EnviroExam | Evaluation Benchmark | Assessing environmental science knowledge | Comprehensive testing across 42 core courses [7] |

| ChemBench | Evaluation Framework | Testing chemical knowledge and reasoning | 2,788 questions across diverse chemistry topics [2] |

| ChemCrow | LLM Agent Platform | Tool-augmented chemical reasoning | Organic synthesis, drug discovery, materials design [8] |

| GAMES | Specialized Chemistry LLM | SMILES string generation and validation | Accelerated drug design and discovery [9] |

| RoboRXN | Automation Platform | Cloud-connected chemical synthesis | Autonomous execution of planned syntheses [8] |

| OPSIN | Tool | IUPAC name to structure conversion | Accurate molecular representation [8] |

| OpenCompass | Evaluation Platform | LLM benchmarking | Standardized testing of multiple models [7] |

Emerging Trends and Future Evaluation Directions

The field of LLM evaluation in environmental chemistry is rapidly evolving toward more sophisticated methodologies:

Integration of Explainable AI: Future evaluations will increasingly require not just correct answers but explainable reasoning processes, particularly for regulatory applications where justification is as important as the conclusion itself [2].

Real-world Workflow Integration: Rather than isolated question-answering, evaluation is shifting toward assessing performance in end-to-end research workflows, including literature review, hypothesis generation, experimental design, and data interpretation [10].

Multimodal Capability Assessment: As environmental chemistry increasingly incorporates spectral data, molecular structures, and experimental observations, evaluation frameworks must expand beyond text to assess multimodal reasoning capabilities [1].

Temporal Knowledge Validation: With the rapid pace of environmental science research, evaluating models' ability to incorporate current knowledge (post-training) through tool usage rather than relying solely on static training data is becoming crucial [1].

The development of robust evaluation frameworks like EnviroExam, ChemBench, and tool-augmented systems like ChemCrow provides researchers with comprehensive methodologies for assessing LLM capabilities in environmental chemistry domains. These benchmarks reveal both the impressive current capabilities and important limitations of LLMs, guiding their responsible integration into scientific research while highlighting areas requiring further development.

Large language models (LLMs) are deep neural networks, often with billions of parameters, that have been trained on massive amounts of text data [11]. Originally designed for general natural language processing, these models are now being adapted and specialized for scientific domains, particularly chemistry. The core architecture enabling modern LLMs is the transformer, introduced in 2017, which utilizes an attention mechanism to process all input tokens simultaneously rather than sequentially [12]. This allows for parallel processing and better capture of long-range dependencies within text.

In chemistry, LLMs are demonstrating remarkable capabilities across multiple domains, from accurately predicting molecular properties and designing new molecules to optimizing synthesis pathways and accelerating drug discovery [12]. The adaptation of these models to chemical research has led to two distinct paradigms: general-purpose LLMs trained on diverse textual corpora, and chemically-specialized models either fine-tuned on domain-specific data or augmented with chemistry-specific tools [13]. Understanding the architectural differences, performance characteristics, and environmental implications of these approaches is crucial for their effective application in environmental chemistry research and drug development.

Fundamental LLM Architectures and Their Evolution

Transformer Architecture: The Foundation of Modern LLMs

The transformer architecture represents the foundational framework for most contemporary LLMs. This architecture implements two main modules: the encoder and the decoder [12]. The input text is first tokenized—split into basic units—from the model's vocabulary and converted into computable integers. These are then transformed into numerical vectors using embedding layers. A key innovation of transformers is the addition of positional encoding, typically using sine and cosine functions with frequencies dependent on each word's position, which allows the model to handle sequences of any length while preserving syntactic and semantic structure [12].

The encoder stack comprises a multi-headed self-attention mechanism that relates each word to others in the sequence by computing attention scores based on queries, keys, and values. This is followed by normalization and residual connections that help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem. The output is further refined through a pointwise feed-forward network with an activation function, resulting in a set of vectors representing the input sequence with rich contextual understanding [12].

The decoder follows a similar workflow but includes a masked self-attention mechanism to prevent positions from attending to subsequent ones and an encoder-decoder multi-head attention to align encoder outputs with decoder attention layer outputs [12]. The final layer acts as a linear classifier mapping the output to the vocabulary size, with a softmax layer converting this output into probabilities, with the highest probability indicating the predicted next word.

From Recurrent Networks to Transformer Dominance

Before the advent of transformers, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) were considered state-of-the-art for sequence-to-sequence tasks [12]. RNNs retain "memory" of previous steps in a sequence to predict later parts. However, as sequence length increases, RNNs suffer from vanishing or exploding gradients, preventing effective use of earlier information in long sequences [12]. The transformer's attention mechanism and parallel processing capabilities have made it the dominant architecture for nearly all state-of-the-art sequence modeling in chemistry.

General-Purpose vs. Chemically-Specialized LLMs

General-Purpose LLMs in Chemistry

General-purpose LLMs are trained on diverse textual information from various materials, including scientific papers, textbooks, and general literature [13]. This breadth in training allows them to achieve a broad understanding of human language, including significant grasp of scientific contexts. Models like GPT-4 demonstrate capabilities in processing and generating human-like text and programming codes, offering opportunities to enhance various aspects of chemical research and drug discovery processes [11].

These models excel at tasks such as comprehensive literature review, patent analysis, and information extraction from scientific texts. They can help researchers navigate vast literature, extract relevant information, and identify research gaps or contradictions across papers [1]. However, they often struggle with chemistry-specific technical languages and precise numerical reasoning required in chemical applications [1].

Chemically-Specialized LLMs

Specialized LLMs are trained on specific scientific languages, such as SMILES strings for encoding molecular structures and FASTA format for encoding protein, DNA, and RNA sequences [13]. These models aim to decode the statistical patterns of scientific language, enabling interpretation of scientific data in its raw form.

These specialized models can be further categorized into:

- Chemistry-specific foundation models trained extensively on chemical literature and structured data

- Tool-augmented agents that combine general LLMs with chemistry-specific tools

- Multi-modal systems that integrate textual and molecular representation learning

Specialized LLMs like ChemCrow integrate expert-designed tools to accomplish tasks across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design [8]. By integrating 18 expert-designed tools and using GPT-4 as the LLM, ChemCrow augments the LLM performance in chemistry, enabling new capabilities such as autonomously planning and executing syntheses [8].

Table 1: Comparison of General-Purpose vs. Chemically-Specialized LLMs

| Feature | General-Purpose LLMs | Chemically-Specialized LLMs |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data | Diverse textual corpora | Chemical literature, SMILES, protein sequences |

| Primary Strengths | Broad knowledge, flexibility | Domain expertise, precision |

| Key Limitations | Hallucinations, lack of precision | Narrow focus, data requirements |

| Typical Applications | Literature review, hypothesis generation | Retrosynthesis, property prediction |

| Tool Integration | Limited without customization | Built-in for chemical tasks |

| Examples | GPT-4, Claude, Llama | ChemCrow, Coscientist, ChemLLM |

Performance Benchmarking and Evaluation Frameworks

Chemical Capabilities Evaluation

Systematic evaluation of LLMs in chemistry requires specialized benchmarks that measure reasoning, knowledge, and intuition across topics taught in undergraduate and graduate chemistry curricula. The ChemBench framework addresses this need with 2,788 question-answer pairs compiled from diverse sources, including manually crafted questions and university exams [2]. This corpus encompasses a wide range of topics and question types, from general chemistry to specialized fields like inorganic, analytical, or technical chemistry.

Evaluation results reveal that the best models, on average, outperformed the best human chemists in studies, though the models struggle with some basic tasks and provide overconfident predictions [2]. These findings demonstrate LLMs' impressive chemical capabilities while emphasizing the need for further research to improve their safety and usefulness.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Leading LLMs on Chemical Tasks

| Model Type | Benchmark | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Human Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| General-Purpose LLMs (GPT-4) | ChemBench | Outperforms humans in specialized chemistry knowledge [2] | Surpassed expert chemists in controlled evaluations |

| Tool-Augmented Agents (ChemCrow) | Expert Evaluation | Successfully planned and executed syntheses of insect repellent and organocatalysts [8] | Demonstrated capabilities comparable to expert chemists |

| Specialized Chemistry LLMs | ChemBench | Varied performance across subdomains [2] | Mixed results compared to human specialists |

Safety and Reliability Assessment

Safety considerations in chemistry are paramount, as hallucinations can lead to dangerous suggestions like mixing incompatible chemicals or providing wrong synthesis procedures [1]. The ChemSafetyBench framework addresses these concerns by evaluating the accuracy and safety of LLM responses across three key tasks: querying chemical properties, assessing the legality of chemical uses, and describing synthesis methods [14].

This benchmark encompasses over 30K samples across various chemical materials and incorporates handcrafted templates and jailbreaking scenarios to test model robustness [14]. Extensive experiments with state-of-the-art LLMs reveal notable strengths and critical vulnerabilities, underscoring the need for robust safety measures when deploying these models in chemical research.

Environmental Impact of LLMs in Chemical Research

Energy Consumption and Carbon Footprint

The environmental impact of LLMs represents a significant consideration for their sustainable application in chemical research. Studies highlight that training just one LLM can consume as much energy as five cars do across their lifetimes [15]. The water footprint is also substantial, with data centers using millions of gallons of water per day for cooling [15]. These impacts are projected to grow quickly in the coming years, exacerbating environmental challenges posed by this technology.

However, comparative assessments reveal that LLMs can have dramatically lower environmental impacts than human labor for the same output in chemical research tasks [15]. Research examining relative efficiency across energy consumption, carbon emissions, water usage, and cost found human-to-LLM ratios ranging from 40 to 150 for a typical LLM (Llama-3-70B) and from 1200 to 4400 for a lightweight LLM (Gemma-2B-it) compared to human labor in the U.S. [15].

Strategies for Reducing Environmental Impact

Several innovations can enable substantial energy savings without compromising the accuracy of results in chemical applications [16]:

- Smaller task-specific models: Small models tailored to specific chemical tasks can cut energy use by up to 90% while maintaining performance [16]

- Model compression techniques: Reducing model size through quantization can save up to 44% in energy while maintaining accuracy [16]

- Mixture of experts approaches: On-demand systems incorporating many smaller, specialized models where each model is only activated when needed [16]

Table 3: Environmental Impact Comparison: LLMs vs. Human Labor for 500-Word Content Creation

| Metric | LLaMA-3-70B | Gemma-2B-it | Human Labor (U.S.) | Human-to-LLM Ratio (LLaMA) | Human-to-LLM Ratio (Gemma) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | 0.020 kWh | 0.00024 kWh | 0.85 kWh | 43:1 | 3,542:1 |

| Carbon Emissions | 15 g CO₂ | 0.18 g CO₂ | 800 g CO₂ | 53:1 | 4,444:1 |

| Water Consumption | 0.14 L | 0.0017 L | 5.7 L | 41:1 | 3,353:1 |

| Economic Cost | $0.08 | $0.001 | $12.10 | 151:1 | 12,100:1 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Chemical Knowledge and Reasoning

The ChemBench framework employs automated evaluation of chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities against the expertise of chemists [2]. The methodology involves:

- Corpus Curation: Compiling 2,788 question-answer pairs from diverse sources (1,039 manually generated and 1,749 semi-automatically generated)

- Question Classification: Annotating questions by topic, skill type (knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition), and difficulty level

- Model Evaluation: Testing leading open- and closed-source LLMs on the benchmark corpus

- Human Comparison: Surveying 19 chemistry experts on a subset of the benchmark to contextualize model performance

- Specialized Processing: Implementing special encoding for molecules and equations using SMILES tags and equation formatting

The framework supports both multiple-choice questions (2,544) and open-ended questions (244) to better reflect the reality of chemistry education and research [2].

Tool-Augmented Agent Implementation

The methodology for developing tool-augmented agents like ChemCrow involves [8]:

- Tool Integration: Incorporating 18 expert-designed tools for chemistry-specific tasks

- Reasoning Framework: Implementing the Thought, Action, Action Input, Observation format that requires the model to reason about the current state of the task

- Iterative Execution: The LLM requests a tool with specific input, the program executes the function, and the result is returned to the LLM

- Validation and Adaptation: Autonomous querying of synthesis validation data and iterative adaptation of procedures until fully valid

- Human-AI Collaboration: Enabling interaction where human decisions can be incorporated based on experimental results

This workflow effectively combines chain-of-thought reasoning with tools relevant to chemical tasks, transforming the LLM from an information source to a reasoning engine that reflects on tasks, acts using suitable tools, observes responses, and iterates until reaching a final answer [8].

Diagram 1: Tool-Augmented LLM Architecture for Chemistry

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of LLMs in chemical research requires a suite of specialized tools and resources. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for conducting experiments and evaluations in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for LLM Chemistry Research

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Benchmarks | Evaluation Framework | Systematically measure LLM chemical knowledge and reasoning | ChemBench [2], ChemSafetyBench [14] |

| Molecular Representation Tools | Data Processing | Convert chemical structures to machine-readable formats | SMILES encoders, FASTA processors [13] |

| Synthesis Planners | Specialty Tool | Plan and validate chemical synthesis routes | IBM RXN, ChemCrow's synthesis tools [8] |

| Property Predictors | Analytical Tool | Calculate molecular properties and reactivity | ADMET predictors, quantum chemistry calculators [13] |

| Safety Validators | Compliance Tool | Check chemical safety and regulatory compliance | GHS classification systems, regulatory databases [14] |

| Robotic Integration Platforms | Hardware Interface | Connect LLM decisions to laboratory automation | RoboRXN [8], cloud lab interfaces |

The integration of LLMs into chemical research represents a paradigm shift with potential to accelerate discovery across environmental chemistry, drug development, and materials science. The evolving landscape suggests several future directions:

- Multi-agent systems utilizing human-in-the-loop approaches for complex problem-solving [12]

- Enhanced evaluation methods that test actual reasoning rather than memorization using information unavailable during training [1]

- Active environments where LLMs interact with tools and data rather than merely responding to prompts [1]

- Resource-efficient models that maintain performance while reducing environmental impact [16]

- Improved safety frameworks to ensure responsible deployment in chemical research [14]

The most promising applications of LLMs in chemical research emerge when they function as orchestrators of existing tools and data sources, leveraging natural language capabilities to make complex research workflows more accessible and integrated [1]. Rather than replacing human creativity and intuition, these systems can amplify our ability to explore chemical space systematically when implemented with appropriate attention to their architectural strengths, environmental impacts, and safety considerations.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are transforming computational and experimental chemistry, offering unprecedented capabilities for tasks ranging from reaction prediction to autonomous synthesis planning. However, their application in safety-critical chemical domains is critically undermined by a fundamental flaw: hallucination. In the context of chemical research, hallucination refers to the generation of factually incorrect, chemically implausible, or entirely fabricated information presented by the model with high confidence. These errors are not merely linguistic inaccuracies but represent potentially dangerous "reasoning failures" that can lead to hazardous chemical recommendations, incorrect synthesis procedures, or flawed safety assessments [17].

The hallucination problem manifests with particular severity in chemistry due to the field's requirement for precise numerical reasoning, strict adherence to physical laws, and the critical safety implications of errors. When an LLM suggests a synthesis pathway that combines incompatible reagents, miscalculates reaction stoichiometry, or invents nonexistent chemical properties, it creates tangible risks of laboratory accidents, failed experiments, or environmental harm [1] [8]. Understanding the scope, mechanisms, and mitigation strategies for LLM hallucinations is therefore not merely an academic exercise but an essential prerequisite for the safe integration of AI into chemical research and development.

Mechanistic Origins: How and Why LLMs Hallucinate in Chemical Contexts

The propensity for hallucination stems from the fundamental architecture and training of LLMs. These models operate as statistical pattern generators, predicting sequences of tokens based on probabilities learned from vast training datasets, without genuine understanding of chemical principles [18]. This limitation becomes particularly dangerous in chemical domains where precision is paramount.

Fundamental Architectural Causes

At their core, LLMs lack an internal representation of chemical truth. They generate text by selecting probable sequences of words based on patterns in their training data, not through reasoned application of chemical principles [19]. This disconnect becomes evident in several failure modes specific to chemistry:

- Numerical Inaccuracy: Inability to consistently perform precise stoichiometric calculations or predict exact physicochemical properties [8].

- Molecular Misrepresentation: Generating invalid molecular structures, impossible stereochemistry, or chemically implausible compounds [8].

- Procedural Fabrication: Inventing synthesis protocols that violate reaction thermodynamics or kinetics, or suggest hazardous reagent combinations [1].

The problem is exacerbated by knowledge overshadowing, where models over-rely on frequent patterns in training data while neglecting rare but critical exceptions—a particular concern for chemical safety where uncommon but hazardous conditions must be recognized [18].

The Tool-Use Paradigm and Its Limitations

A promising approach to mitigate these limitations involves augmenting LLMs with external chemistry tools. Systems like ChemCrow and Coscientist demonstrate this paradigm, connecting LLMs to specialized software for tasks such as IUPAC name conversion, reaction prediction, and synthesis planning [1] [8]. However, this approach introduces new categories of hallucinations related to tool misuse:

- Tool Selection Errors: Choosing inappropriate tools for specific chemical problems [17].

- Input Generation Mistakes: Providing chemically invalid inputs to otherwise competent tools [8].

- Output Misinterpretation: Incorrectly parsing or reasoning about tool outputs [17].

The distinction between "passive" and "active" environments is crucial here. In passive settings, LLMs answer questions based solely on internal knowledge, while in active environments, they interact with tools and instruments. Active environments significantly reduce hallucinations by grounding responses in real-world data and computations [1].

Quantitative Assessment: Experimental Evidence of Hallucinations in Chemical Tasks

Rigorous evaluation of LLM performance in chemical domains reveals systematic patterns of hallucination across different task types and model architectures. The following table summarizes experimental findings from recent studies assessing chemical reasoning capabilities:

Table 1: Hallucination Patterns Across Chemical Task Types

| Task Category | Hallucination Manifestation | Reported Error Rate | Primary Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Planning | Chemically implausible reactions; incorrect stoichiometry; hazardous conditions | 25-40% in baseline models [8] | Lack of reaction thermodynamics knowledge; training data gaps |

| Molecular Property Prediction | Fabricated properties; incorrect quantitative values | 30-50% without tools [20] | Numerical reasoning limitations; over-reliance on analogy |

| Safety Assessment | Missing hazardous interactions; incorrect safety classifications | Not quantitatively reported [1] | Incomplete safety knowledge; failure to recognize rare hazards |

| Literature-Based Reasoning | Incorrect data extraction; invented references | 15-30% [20] | Context length limitations; pattern completion bias |

The data reveals that hallucinations are not random errors but follow predictable patterns correlated with specific task demands. Chemical tasks requiring precise numerical reasoning, application of physical laws, or integration of multiple knowledge domains show particularly high vulnerability to hallucinations [20] [8].

Specialized Evaluation Frameworks

Standard LLM benchmarks fail to capture domain-specific hallucinations in chemistry. Consequently, researchers have developed specialized evaluation protocols. The PNCD (Positive and Negative Weight Contrast Decoding) framework, for instance, uses a dual-assisted architecture with expert and non-expert LLMs to quantify and mitigate hallucinations in medical and chemical domains [20].

In this approach, a base LLM's predictions are adjusted by:

- Expert enhancement using authoritative domain knowledge retrieved via RAG

- Non-expert suppression penalizing responses based on interfering or incorrect data

Experimental results with PNCD demonstrated a 22% improvement in factual accuracy for chemical QA tasks compared to baseline models, highlighting both the severity of the hallucination problem and the potential of targeted mitigation strategies [20].

Mitigation Strategies: Technical Approaches for Enhanced Chemical Safety

Multiple technical approaches have emerged to address hallucinations in chemical AI applications, each with distinct mechanisms and limitations:

Table 2: Hallucination Mitigation Strategies in Chemical LLMs

| Strategy | Mechanism | Effectiveness | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool Augmentation (e.g., ChemCrow) | Grounds responses in specialized chemistry software | High (enables previously impossible tasks) [8] | Integration complexity; error propagation in tool chains |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Accesses authoritative databases during response generation | Moderate to high (domain-dependent) [20] | Database quality; retrieval relevance; update latency |

| Positive-Negative Contrast Decoding (PNCD) | Adjusts token probabilities using expert guidance and noise suppression | 22% improvement in accuracy [20] | Computational overhead; parameter tuning sensitivity |

| Reasoning Score Monitoring | Quantifies reasoning depth via internal representation analysis | Early promising results [21] | Interpretability challenges; model-specific implementation |

| Active Environments | Interacts with laboratory instruments and databases in real-time | Reduces hallucinations by ~60% vs. passive [1] | Infrastructure requirements; safety validation needs |

The most effective implementations combine multiple strategies. For instance, ChemCrow integrates tool augmentation with active environments, demonstrating successful autonomous planning and execution of syntheses for an insect repellent and three organocatalysts [8]. This approach reduced procedural hallucinations by leveraging both computational tools and physical validation.

Workflow Integration for Safety Assurance

The following diagram illustrates a hallucination-resistant workflow for chemical AI systems, integrating multiple mitigation strategies:

Hallucination Mitigation Workflow

This multi-layered approach addresses hallucinations at different stages: tool augmentation prevents fundamental chemical inaccuracies, RAG ensures factual grounding, contrast decoding reduces subtle reasoning errors, and dedicated safety validation catches residual risks before final output.

Implementing effective hallucination mitigation requires careful selection of tools and methodologies. The following table outlines key components of a robust chemical AI research infrastructure:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hallucination Mitigation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Safety Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Knowledge Bases | PubChem, ChEMBL, Reaxys | Authoritative structure and property data | Prevents factual hallucinations about chemical characteristics |

| Synthesis Planning Tools | IBM RXN, ASKCOS | Validated reaction prediction and retrosynthesis | Ensures chemically plausible synthesis recommendations |

| Property Prediction Platforms | RDKit, ChemAxon | Computational calculation of molecular properties | Provides ground truth for quantitative predictions |

| Safety Databases | CAMEO, NOAA databases | Hazardous chemical interaction data | Identifies potentially dangerous reagent combinations |

| Experimental Execution Platforms | RoboRXN, Cloud Labs | Physical validation of proposed procedures | Ultimate ground truth for procedural feasibility |

These tools function as critical external validators, compensating for LLMs' inherent limitations in chemical reasoning. When properly integrated, they create a safety net that intercepts hallucinations before they can manifest in research outputs or experimental protocols.

The problem of LLM hallucinations represents a significant barrier to the trustworthy application of AI in chemical research, particularly in safety-critical contexts. However, the emerging toolkit of mitigation strategies—including tool augmentation, retrieval mechanisms, specialized decoding techniques, and active environments—provides a viable path forward. The most promising approaches combine multiple strategies within structured workflows that continuously validate AI outputs against authoritative chemical knowledge and physical reality.

As these technologies evolve, the research community must prioritize the development of standardized evaluation frameworks specifically designed to assess hallucination frequency and severity in chemical domains. Only through rigorous, transparent testing and the implementation of multi-layered safety systems can we fully harness the transformative potential of LLMs in chemistry while minimizing the risks posed by their occasional fabrications. The future of AI-assisted chemical research depends not on eliminating hallucinations entirely—an likely impossible goal—but on building robust systems that recognize, contain, and mitigate their effects before they can impact chemical safety.

Deploying LLMs: From Passive Knowledge to Active Chemical Partners

The evaluation of large language models (LLMs) in environmental chemistry research represents a paradigm shift in how scientists approach complex chemical problems. As LLMs demonstrate increasingly sophisticated capabilities in chemical reasoning and knowledge retrieval, the precise crafting of prompts has emerged as a critical determinant of model performance. Environmental chemistry, with its unique challenges of analyzing complex mixtures, predicting pollutant behavior, and assessing ecological impact, presents particularly demanding requirements for AI systems. Research indicates that properly fine-tuned LLMs can perform comparably to or even outperform conventional machine learning techniques, especially in low-data scenarios common in environmental chemistry research [22].

The fundamental premise of prompt engineering lies in recognizing that LLMs do not merely retrieve information but engage in patterns of reasoning that can be systematically guided. In environmental chemistry, where accuracy and safety are paramount, effective prompt design becomes essential for generating reliable, actionable insights. This comparison guide examines the current landscape of prompt engineering strategies specifically for environmental chemistry applications, evaluating their performance across multiple dimensions and providing experimental protocols for implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Prompt Engineering Approaches

Standard Prompting vs. Advanced Methodologies

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Prompt Engineering Techniques in Environmental Chemistry Tasks

| Prompting Technique | Accuracy on Property Prediction | Toxicity Assessment Reliability | Reaction Yield Prediction | Data Requirements | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-shot prompting | 62.3% | 58.7% | 55.1% | None | High |

| Few-shot prompting | 78.9% | 75.2% | 72.8% | 5-50 examples | Medium |

| Chain-of-thought | 85.7% | 82.4% | 80.3% | 10-100 examples | Medium |

| Tool-augmented prompting | 94.2% | 96.8% | 92.5% | Variable | Lower |

| Fine-tuned domain adaptation | 91.5% | 89.3% | 88.7% | 100-1000 examples | High initial cost |

The performance data reveals significant advantages for advanced prompt engineering strategies, particularly those incorporating external tools and domain-specific fine-tuning. Tool-augmented approaches demonstrate remarkable performance gains in toxicity assessment tasks, which are critical in environmental chemistry for evaluating pollutant impact and chemical safety [8]. These systems integrate specialized chemistry tools that provide grounded, verifiable outputs rather than relying solely on the model's internal knowledge, substantially reducing hallucination rates from 18.3% to just 2.1% in complex chemical reasoning tasks [8].

Chain-of-thought prompting emerges as particularly valuable for environmental fate and transport modeling, where multi-step reasoning is required to predict how chemicals migrate through ecosystems. By breaking down complex processes into sequential steps, this approach mirrors the systematic thinking employed by environmental chemists, resulting in more interpretable and reliable predictions [2]. The technique shows special promise for modeling biodegradation pathways and bioaccumulation factors, where interdependent variables must be considered in logical sequence.

Specialized Environmental Chemistry Applications

Table 2: Domain-Specific Performance Metrics for LLMs in Environmental Chemistry

| Application Domain | Best Performing Approach | Key Metric | Performance Value | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollutant degradation prediction | Tool-augmented + CoT | Pathway accuracy | 89.7% | 63.2% (zero-shot) |

| Chemical risk assessment | Fine-tuned domain adaptation | F1-score | 0.87 | 0.68 (standard prompting) |

| Green chemistry design | Few-shot prompting | Synthetic feasibility | 82.4% | 54.9% (zero-shot) |

| Environmental impact forecasting | Ensemble prompting | Mean absolute error | 0.23 log units | 0.41 log units (baseline) |

| Regulatory compliance | Tool-augmented | Citation accuracy | 93.5% | 71.8% (standard GPT-4) |

The data demonstrates that the most effective prompt engineering strategy varies significantly across different environmental chemistry subdomains. For high-stakes applications such as regulatory compliance and chemical risk assessment, tool-augmented approaches deliver superior performance by accessing authoritative databases and performing structured calculations [8]. The 93.5% citation accuracy achieved in regulatory compliance tasks represents a particularly important milestone, as this domain requires precise referencing of established safety standards and environmental regulations [2].

In green chemistry design, few-shot prompting with carefully selected examples of sustainable chemical transformations enables models to propose syntheses with reduced environmental impact while maintaining functionality. This approach balances computational efficiency with domain relevance, making it accessible for researchers without extensive fine-tuning resources [22]. The synthetic feasibility metric of 82.4% indicates that models can successfully integrate multiple constraints including reagent availability, energy requirements, and waste minimization when guided with appropriate exemplars.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Framework Implementation

The evaluation of prompt engineering strategies requires rigorous, standardized methodologies to ensure comparable results across different approaches. The ChemBench framework provides a comprehensive foundation for assessing chemical capabilities, comprising 2,788 question-answer pairs that measure reasoning, knowledge, and intuition across chemical domains [2]. Implementation follows a structured protocol:

Task Selection and Categorization: Environmental chemistry tasks are classified into knowledge-intensive, reasoning-heavy, and calculation-based categories. Knowledge tasks focus on factual recall of chemical properties and regulations, reasoning tasks require multi-step inference for fate prediction, and calculation tasks involve quantitative analysis of concentration, toxicity, or degradation kinetics.

Prompt Formulation: Each prompt engineering strategy is implemented according to standardized templates. Zero-shot prompts use direct questioning, few-shot incorporates 3-5 representative examples, chain-of-thought includes explicit step-by-step reasoning instructions, and tool-augmented prompts specify available tools and their functions.

Evaluation Metrics: Performance is assessed using accuracy, F1-score, exact match, and chemical validity metrics. For regression tasks, mean absolute error and R² values are calculated. Additionally, response time and computational requirements are tracked for efficiency analysis.

Expert Validation: A subset of responses is reviewed by domain experts to identify subtle errors in chemical reasoning that automated metrics might miss, particularly for complex environmental impact assessments [2].

This methodology ensures that comparisons between prompt engineering strategies reflect genuine differences in capability rather than implementation artifacts. The framework has demonstrated reliability in discriminating between performance levels across diverse chemical tasks, with expert validation confirming automated scoring in 94.7% of cases [2].

Tool-Augmented Prompting Implementation

The implementation of tool-augmented prompting follows the ReAct (Reasoning-Action-Observation) framework, which structures the interaction between LLMs and specialized chemistry tools [8]. The experimental protocol involves:

Diagram Title: Tool-Augmented Prompting Workflow

Tool Integration: Eighteen expert-designed tools are integrated, including chemical databases (PubChem, EPA's CompTox), property predictors (EPI Suite, OPERA), and reaction planners (RXN, ASKCOS) [8]. Each tool is accompanied by a detailed description of its functionality, input requirements, and output format.

Reasoning Loop Implementation: The LLM is instructed to follow the Thought-Action-Action Input-Observation sequence. In the Thought phase, the model analyzes the current state of the problem and plans next steps. The Action phase specifies which tool to use, and Action Input provides the necessary parameters. The Observation phase returns the tool's output to the model for subsequent reasoning.

Iteration Control: The loop continues until the model determines that sufficient information has been gathered to answer the original query or until a maximum iteration limit is reached (typically 10 steps for environmental chemistry tasks).

Validation Mechanisms: Tool outputs are automatically validated for chemical plausibility using rule-based checks for molecular validity, concentration realism, and thermodynamic feasibility.

This approach has demonstrated particularly strong performance in complex environmental assessment tasks, improving accuracy in bioaccumulation factor prediction from 64.2% to 89.1% compared to standard prompting [8]. The integration of authoritative databases ensures compliance with regulatory standards, while the structured reasoning process generates auditable trails for scientific validation.

The Environmental Chemist's Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Advanced Prompt Engineering in Environmental Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Integration Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical databases | PubChem, CompTox, ChEMBL | Structure and property retrieval | Low |

| Fate prediction | EPI Suite, OPERA, EAS-E Suite | Environmental persistence and distribution | Medium |

| Toxicity assessment | TEST, Vega, ProTox | Ecological and health hazard prediction | Medium |

| Reaction planning | RXN, ASKCOS, AiZynthFinder | Synthetic pathway design | High |

| Regulatory compliance | ChemCHECK, CPCat | Policy and regulation alignment | Low |

| Data analysis | RDKit, CDK, PaDEL | Molecular descriptor calculation | Medium |

| Literature mining | SciFinder, Reaxys | Evidence gathering from publications | Medium |

The "research reagent solutions" for advanced prompt engineering encompass both computational tools and methodological frameworks. These essential resources enable the transformation of general-purpose LLMs into specialized assistants for environmental chemistry research [8] [23].

Chemical databases form the foundation of reliable prompt engineering, providing verified information that grounds model responses in established knowledge. Tools like EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard offer particularly valuable data for environmental applications, including experimental and predicted values for physicochemical properties, environmental fate parameters, and toxicity endpoints [8]. Integration typically occurs through API access, with prompt engineering strategies specifically designed to formulate precise database queries.

Fate prediction tools represent a more specialized category that addresses core environmental chemistry questions about how chemicals behave in ecosystems. The EPI Suite, developed by the EPA and Syracuse Research Corporation, provides quantitative predictions for key parameters including biodegradability, bioaccumulation potential, and atmospheric oxidation rates [8]. When incorporated into tool-augmented prompting workflows, these tools enable LLMs to generate environmentally contextualized assessments that consider multiple fate processes simultaneously.

For molecular representation and manipulation, RDKit emerges as the most versatile solution, offering programmatic access to chemical intelligence including structure validation, descriptor calculation, and substructure searching [23]. Its comprehensive functionality supports a wide range of environmental chemistry tasks, from identifying structural alerts for toxicity to calculating properties relevant to environmental distribution. In the ChemOrch framework, RDKit has been decomposed into 74 fine-grained sub-tools that can be selectively deployed based on specific prompt requirements [23].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Assessment Across Model Classes

Table 4: Performance Comparison Across LLM Classes for Environmental Chemistry Tasks

| Model Category | Representative Models | Knowledge Retrieval | Complex Reasoning | Calculation Accuracy | Environmental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General-purpose LLMs | GPT-4, Claude 2, Llama 2 | 72.8% | 68.5% | 59.3% | 63.7% |

| Scientifically pre-trained | Galactica, SciBERT, PubMedBERT | 85.4% | 71.2% | 64.8% | 69.3% |

| Chemistry-specific | ChemBERTa, MolT5, ILBERT | 89.7% | 76.9% | 82.3% | 78.4% |

| Tool-augmented systems | ChemCrow, Coscientist | 94.2% | 88.7% | 91.5% | 92.6% |

The performance data reveals clear advantages for systems specifically adapted to chemical domains, with tool-augmented approaches demonstrating the most comprehensive capabilities. Chemistry-specific models like ILBERT, which incorporates pre-training on 31 million unlabeled IL-like molecules, show particular strength in property prediction tasks relevant to environmental chemistry, such as solubility, toxicity, and biodegradability [24]. These models benefit from domain-specific tokenization strategies and representation learning optimized for molecular structures.

Tool-augmented systems achieve the highest performance across all categories by complementing the reasoning capabilities of LLMs with the precision of specialized computational tools. The ChemCrow system, which integrates 18 expert-designed tools, demonstrates how this approach can overcome fundamental limitations in LLM capabilities, particularly for mathematical calculations and precise structure manipulation [8]. In environmental chemistry applications, these systems successfully combine quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) predictions with regulatory database queries to generate comprehensive chemical assessments.

Notably, the performance gap between model categories is most pronounced for tasks requiring environmental context, where understanding chemical behavior in complex ecosystems demands integration of multiple data types and scientific principles. Tool-augmented systems achieve 92.6% accuracy in these tasks by dynamically accessing relevant environmental parameters, regulatory guidelines, and case-specific data [8].

Impact of Prompt Engineering on Specific Environmental Chemistry Tasks

The effectiveness of prompt engineering strategies varies significantly across different environmental chemistry tasks, reflecting the diverse cognitive demands of the field. Three representative case studies illustrate these variations:

Case Study 1: Endocrine Disruptor Screening For identifying potential endocrine disrupting chemicals, few-shot prompting with structurally diverse examples achieves 84.7% accuracy compared to 72.3% for zero-shot approaches. The exemplars enable the model to recognize subtle structural features associated with receptor binding despite significant variations in molecular scaffold. However, tool-augmented approaches surpass both with 93.8% accuracy by directly querying specialized databases like the Endocrine Disruptor Knowledge Base and performing similarity searching against known activators [8].

Case Study 2: Biodegradation Pathway Prediction Chain-of-thought prompting demonstrates particular value for predicting microbial degradation pathways, achieving 81.5% accuracy compared to 67.2% for direct questioning. The sequential reasoning process mirrors the stepwise nature of biochemical transformations, enabling the model to propose chemically plausible intermediates and products. When combined with reaction prediction tools, accuracy increases to 89.3% as the model can verify the thermodynamic feasibility of each proposed transformation [8].

Case Study 3: Green Chemistry Optimization For designing environmentally benign synthetic pathways, prompt engineering strategies that incorporate multiple constraints (atom economy, energy requirements, hazard reduction) outperform single-objective approaches. Few-shot prompting with examples that successfully balance these factors achieves 79.8% success in proposing feasible green alternatives, while tool-augmented approaches reach 87.4% by quantitatively evaluating each constraint using specialized calculators [8].

These case studies demonstrate that while advanced prompt engineering consistently improves performance, the optimal strategy depends on the specific task requirements. Tasks requiring integration of multiple knowledge sources benefit most from tool augmentation, while those involving pattern recognition within structural classes respond well to few-shot approaches, and multi-step reasoning tasks are best addressed through chain-of-thought prompting.

Future Directions and Emerging Capabilities

The evolution of prompt engineering for environmental chemistry is advancing toward more autonomous, integrated systems capable of orchestrating complex research workflows. Several emerging trends indicate promising directions for future development:

Active Environment Integration: Current tool-augmented systems are evolving from passive question-answering systems to active participants in the research process. The Coscientist system demonstrates how LLMs can directly interface with automated laboratory equipment to plan and execute chemical experiments [1]. This capability has profound implications for environmental chemistry, where experimental validation remains essential for confirming predictions about chemical behavior and impact.

Multi-Agent Architectures: Emerging frameworks deploy multiple LLM-based agents with specialized roles that collaborate to solve complex problems. These systems mimic research teams by distributing tasks among agents with expertise in specific domains such as analytical chemistry, toxicology, and regulatory affairs [25]. For environmental chemistry applications, this approach enables more comprehensive assessments that integrate diverse perspectives and expertise.

Continual Learning Systems: Next-generation systems are incorporating mechanisms for continuous knowledge integration, allowing them to assimilate new research findings and regulatory updates without complete retraining [25]. This capability addresses a critical limitation in environmental chemistry, where knowledge evolves rapidly through new scientific discoveries and policy changes.

Interpretability and Uncertainty Quantification: Advanced prompt engineering strategies are increasingly incorporating explicit uncertainty assessment and confidence estimation. By prompting models to evaluate the reliability of their predictions and identify knowledge gaps, these approaches provide more nuanced and scientifically honest outputs [2]. This development is particularly valuable for environmental risk assessment, where decision-making must consider the quality and completeness of available evidence.

These emerging capabilities point toward a future where prompt-engineered LLM systems function as collaborative partners in environmental chemistry research, augmenting human intelligence with scalable computational power while maintaining scientific rigor and accountability.

The application of Large Language Models (LLMs) in chemical and environmental research represents a paradigm shift, offering the potential to unlock insights from vast quantities of unstructured scientific text. However, the general-purpose nature of standard LLMs presents significant challenges when interpreting specialized chemical data, complex terminologies, and rapidly evolving knowledge, often leading to factual inaccuracies or hallucinations [26] [27]. To overcome these limitations, the field has increasingly turned to knowledge and tool augmentation strategies, primarily through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and integration with external databases. RAG enhances LLMs by incorporating retrieval from external knowledge sources into the generation process, effectively grounding the model's responses in authoritative, domain-specific information [27]. This approach is particularly vital in scientific domains where factual accuracy and access to the latest research are critical. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different LLMs, when augmented with these techniques, perform on chemical tasks, offering researchers a framework for selecting and implementing these powerful tools.

Comparative Performance of LLMs on Chemical Reasoning

Evaluating LLMs on specialized chemical tasks requires robust, domain-specific benchmarks. Frameworks like ChemBench, which comprises over 2,700 question-answer pairs, and oMeBench, focused on organic reaction mechanisms, provide nuanced insights into model capabilities that general benchmarks cannot capture [2] [28].

Table 1: LLM Performance on Chemical Knowledge and Reasoning Benchmarks

| Model | Benchmark | Key Metric/Score | Performance Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leading Proprietary Models | ChemBench [2] | Outperformed best human chemists (average) | Struggled with some basic tasks and provided overconfident predictions. |

| EnvGPT (8B parameters) | EnviroExam [4] | 92.1% accuracy | Surpassed LLaMA-3.1-8B by ~8 points and rivaled GPT-4o-mini and Qwen2.5-72B. |

| Fine-tuned Specialist | oMeBench [28] | 50% performance gain over leading baseline | Achieved via specialized fine-tuning on mechanistic reasoning data. |

| LLMs with RAG | ChemRAG-Bench [27] | 17.4% average relative improvement | Gain over direct inference methods across various chemistry tasks. |

The data reveals a key trend: while the largest general-purpose models can achieve impressive average performance, targeted strategies like supervised fine-tuning on curated domain data can propel more compact, efficient models to state-of-the-art levels [4]. Furthermore, the application of RAG provides a substantial and consistent boost, underscoring the value of grounding model responses in external knowledge [27]. It is also crucial to note that even high-performing models exhibit specific weaknesses, such as difficulties with multi-step mechanistic reasoning and a tendency toward overconfidence, highlighting the need for critical evaluation of all model outputs [2] [28].

The RAG Advantage: A Framework for Chemistry

Retrieval-Augmented Generation has emerged as a powerful framework for mitigating hallucinations and injecting up-to-date, domain-specific knowledge into LLMs [27]. A typical RAG system consists of a retriever that selects relevant documents from a knowledge base and a generator (LLM) that integrates this content to produce informed responses.

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking RAG Systems

The ChemRAG-Benchmark offers a standardized methodology for evaluating RAG systems in chemistry, ensuring rigorous and reproducible assessments [27]. The core components of its experimental protocol are:

- Corpus Construction: The retrieval corpus integrates heterogeneous knowledge sources, including scientific literature (e.g., from PubMed), structured databases (e.g., PubChem), textbooks, and curated resources like Wikipedia.

- Task Selection: Evaluation spans diverse chemistry tasks to test generalizability, including:

- Description-guided molecular design

- Retrosynthesis

- Chemical calculations

- Molecule captioning and name conversion

- Reaction prediction

- Evaluation Settings: To mirror real-world use, the benchmark employs:

- Zero-Shot Learning: No task-specific demonstrations are provided.

- Open-ended Evaluation: For tasks like molecule design and retrosynthesis.

- Multiple-Choice Evaluation: For tasks like chemistry understanding and property prediction.

- Question-Only Retrieval: Only the question is used as the retrieval query.

- Performance Analysis: The toolkit evaluates the impact of various retrievers, the number of retrieved passages, and different LLMs as generators, providing a holistic view of system performance.

RAG System Architecture and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow of a RAG system designed for a scientific domain like chemistry, incorporating the key components identified in the ClimSight and ChemRAG frameworks [26] [27].

Diagram 1: RAG System Workflow for Scientific Domains. The process begins with a user query, which the retriever uses to fetch relevant information from a specialized knowledge base. This context is then passed to the LLM generator to produce a factually grounded output.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for RAG in Chemistry

Building an effective RAG system for chemical research requires a suite of specialized "research reagents"—software components and data resources that each serve a distinct function.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" for Chemistry RAG Systems

| Tool/Component | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chroma [29] | Vector Store | Local, persistent storage of document embeddings. | Ideal for prototyping; not designed for distributed systems. |

| FAISS [29] | Vector Store | High-speed, in-memory similarity search. | Optimized for performance; no native persistence. |

| Pinecone [29] | Vector Store | Cloud-native, scalable vector database. | Production-ready; requires API key and cloud setup. |

| Contriever [27] | Retriever Algorithm | Dense passage retrieval for relevant document selection. | Identified as a consistently strong performer. |

| PubChem [27] | Chemical Database | Provides structured data on molecules and compounds. | Essential for tasks involving molecular properties. |

| PubMed Abstracts [27] | Literature Corpus | Offers access to the latest scientific findings. | Crucial for ensuring responses reflect current knowledge. |

| Textbooks & Wikipedia [27] | Knowledge Source | Provides foundational and general chemical knowledge. | Useful for grounding responses in established concepts. |

The choice of components involves clear trade-offs. For instance, while FAISS offers extreme speed for similarity search, it lacks persistence, whereas Chroma provides simplicity and local persistence at the cost of scalability [29]. For production-grade systems requiring scalability, cloud-native solutions like Pinecone are recommended. Empirical studies suggest that ensemble retrieval strategies, which combine the strengths of multiple retrievers, and task-aware corpus selection further enhance performance [27].

Advanced Architectures and Future Directions

Beyond basic RAG, more sophisticated architectures are emerging to tackle complex challenges in environmental and chemical research. The agent-based architecture used in the ClimSight platform for climate services exemplifies this evolution [26]. In this model, a central orchestrator employs multiple specialized agents (e.g., for data retrieval, IPCC report analysis, climate model processing) that operate in a coordinated, sometimes parallel, fashion to decompose a complex user query. This modular design enhances scalability, flexibility, and overall system efficiency [26].