From Field to Lab: Validating In-Situ Monitoring Against Laboratory Analysis for Environmental Samples

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating in-situ monitoring technologies against traditional laboratory analysis.

From Field to Lab: Validating In-Situ Monitoring Against Laboratory Analysis for Environmental Samples

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on validating in-situ monitoring technologies against traditional laboratory analysis. It explores the fundamental principles of both approaches, details methodological applications across various environmental contexts, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous protocols for comparative validation. By synthesizing current research and real-world case studies, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to ensure data integrity, enhance measurement accuracy, and make informed decisions on integrating in-situ monitoring into quality assurance programs.

Understanding the Core Principles: In-Situ Monitoring and Laboratory Analysis

In-situ monitoring represents a paradigm shift in environmental data collection, enabling researchers to gather real-time information directly from a substance's native environment. This approach involves placing sensors or instruments at the exact location where measurements are needed, providing continuous data about environmental conditions, chemical processes, or physical changes without disturbing the system being studied. For researchers and drug development professionals working with environmental samples, understanding the capabilities and limitations of in-situ monitoring is crucial for designing effective sampling strategies and interpreting analytical results. This guide examines how in-situ monitoring compares with traditional laboratory analysis across multiple environmental matrices, supported by experimental data and methodological details from current research.

Core Principles and Key Comparisons

Fundamental Definitions

In-situ monitoring refers to on-site data collection that measures parameters directly where they occur, providing immediate results crucial for time-sensitive decisions [1]. This method captures real-world conditions precisely by avoiding sample degradation during transport [1]. By contrast, laboratory-based analysis involves collecting samples and testing them in a controlled laboratory setting, allowing for precise analysis of multiple parameters simultaneously and detection of trace contaminants [2].

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

The selection between in-situ and laboratory methodologies involves strategic trade-offs between temporal resolution and analytical precision, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of In-Situ versus Laboratory-Based Analysis

| Aspect | In-Situ Monitoring | Laboratory-Based Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Data temporal resolution | Real-time/continuous data streams [1] | Days to weeks delay for results [2] |

| Measurement context | Directly in native environment without disturbance [1] | Removed from environmental context [2] |

| Parameter range | Limited to sensor capabilities; typically physical parameters (temperature, pH, conductivity) and some chemicals [1] [2] | Broad range; can test multiple parameters simultaneously, including trace contaminants [2] |

| Accuracy concerns | Sensor drift, fouling, environmental interference [2] [3] | Controlled conditions minimize interference; can detect trace amounts [2] |

| Operational requirements | Lower long-term manpower; reduced sample transport [1] [2] | Specialized equipment, trained personnel, sample transportation [2] |

| Cost structure | Higher initial investment; lower operational costs [2] | Lower initial costs; higher per-sample operational costs [2] |

Experimental Validation: Methodologies and Data

Water Quality Monitoring in Lake Ecosystems

A 2020-2021 study on Lake Maggiore, Italy, implemented a high-frequency monitoring (HFM) system to complement long-term discrete sampling programs [4]. The research aimed to validate in-situ fluorometric sensors for chlorophyll-a measurement against traditional laboratory methods.

Table 2: Chlorophyll-a Measurement Comparison Across Methodologies

| Methodology | Technique Description | Frequency Capability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-situ fluorescence sensors | Cyclops7 sensor deployed on buoy system | Continuous high-frequency data | Influenced by phytoplankton community composition |

| Laboratory fluorescence | BBE FluoroProbe analysis | Discrete sampling intervals | Requires sample transport and processing |

| Spectrophotometry | UV-VIS analysis following extraction | Discrete sampling intervals | Time-consuming extraction protocols |

| Microscopy analysis | Taxonomic identification and enumeration | Discrete sampling intervals | Labor-intensive; requires specialist expertise |

The validation protocol involved regular comparison of chlorophyll-a data from in-situ fluorescent sensors with laboratory fluorescence analysis, UV-VIS spectrophotometry, and phytoplankton microscopy. Researchers found general agreement between methods, confirming in-situ sensors as a reliable approach for assessing seasonal phytoplankton dynamics and short-term variability [4]. However, phytoplankton community composition substantially affected method performance, necessitating regular validation against laboratory analyses.

Soil Property Analysis Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy

A 2022 investigation compared in-situ versus laboratory mid-infrared spectroscopy (MIRS) for predicting key soil properties including organic carbon, total nitrogen, clay content, and pH [3]. The study implemented multiple calibration strategies across three loess sites in Germany with different tillage treatments.

Experimental Protocol:

- Field MIRS: Surface measurements taken directly in the field at multiple locations

- Laboratory MIRS: Analysis of dried/ground soil samples (<0.2 mm) collected from same sites

- Reference analysis: Conventional determination of OC, TN, clay, and pH

- Model development: Partial least squares regression models with local and regional calibration strategies

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Lab vs. In-Situ MIRS for Soil Properties (RPIQ Values)

| Soil Property | Lab MIRS (Regional n=38) | Field MIRS (Regional n=150) | Field MIRS (Spiked Regional) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Carbon | 4.3 | ≥1.89 | ≥1.89 |

| Total Nitrogen | 6.7 | ≥1.89 | ≥1.89 |

| Clay | Variable (0.89-2.8) | Lower accuracy | Improved with spiking |

| pH | Variable (0.60-3.2) | Lower accuracy | Improved with spiking |

The study demonstrated that laboratory MIRS consistently outperformed field MIRS across all properties and calibration strategies. Field MIRS required more complex calibration procedures, including "spiking" regional calibrations with local samples, to achieve satisfactory accuracy (RPIQ ≥ 1.89) [3]. Soil moisture content was identified as a major confounding factor, particularly affecting organic carbon prediction and sandier soils.

Antibiotic Measurement in Sediments

A 2023 study developed and validated a novel in-situ technique for high-resolution measurement of antibiotics in sediments using diffusive gradients in thin-films (DGT) probes [5].

Methodological Details:

- DGT Probe Design: Systematic development for organic contaminant measurement

- Spatial Resolution: Capability for millimeter-scale compound distribution mapping

- Comparison Method: Traditional Rhizon pore-water sampling

- Validation Environment: Controlled sediment system and intact sediment core from Chinese lake

The research demonstrated that DGT probes successfully resolved antibiotic distributions at millimeter scales and reflected fluxes from sediment pore-water plus remobilization from solid phases [5]. Antibiotic concentrations obtained by DGT probes were lower than pore-water concentrations from Rhizon sampling, as DGT measures only the labile (bioavailable) fraction rather than total concentrations.

Technical Workflows and Signaling Pathways

In-Situ Monitoring Validation Workflow

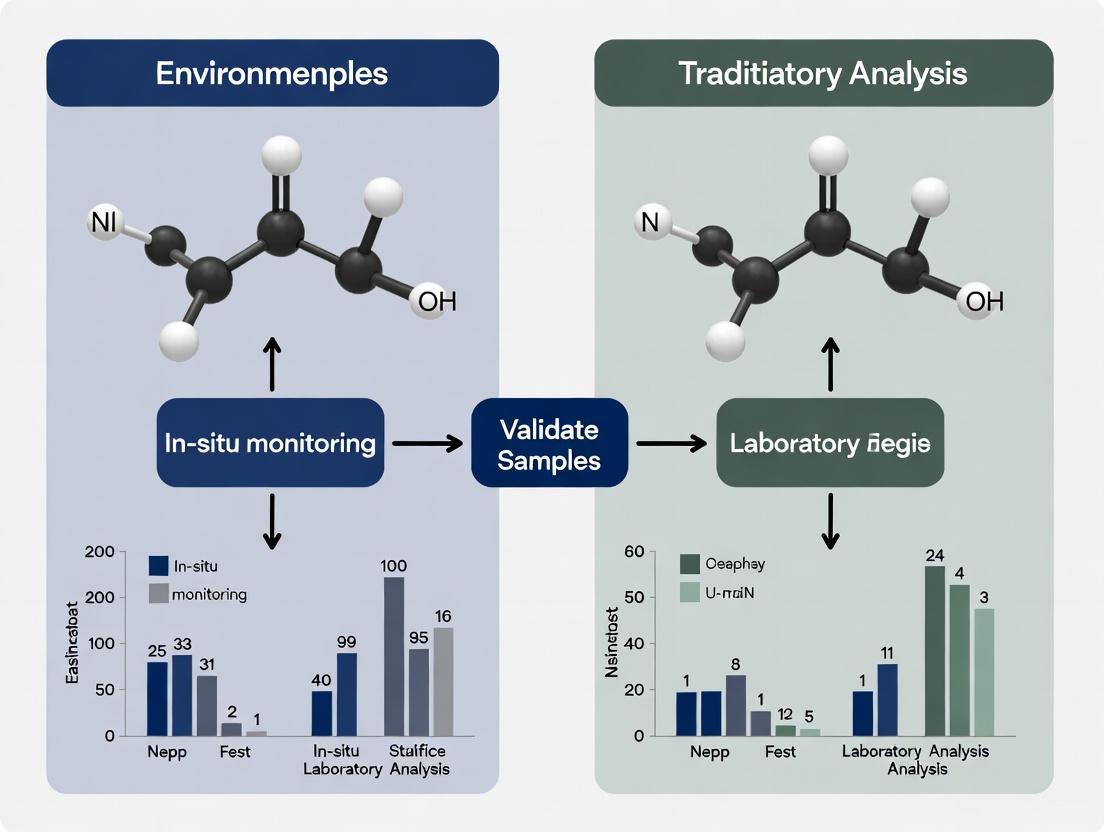

In-Situ Method Validation Workflow

This workflow illustrates the standardized approach for validating in-situ monitoring methods against laboratory benchmarks, as demonstrated across multiple environmental matrices in the cited studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Instrumentation and Materials for In-Situ Environmental Monitoring

| Instrument/Material | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multiparameter water quality probes | Simultaneous measurement of temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, turbidity [1] [2] | Continuous water quality monitoring in rivers, lakes, oceans [2] |

| DGT (Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films) probes | In-situ measurement of organic contaminants at high spatial resolution [5] | Antibiotic detection in sediments; mm-scale compound distribution mapping [5] |

| Mid-infrared spectroscopy (MIRS) sensors | Field-based soil property prediction using spectral analysis [3] | Soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, clay content, and pH estimation [3] |

| Fluorometric sensors (Cyclops7) | In-situ chlorophyll-a and algal pigment measurement via fluorescence [4] | Phytoplankton biomass monitoring; algal bloom detection [4] |

| TEROS 21/MPS-6 | Soil water potential (matric potential) measurement [6] | In-situ soil moisture release curves; irrigation management [6] |

| Open-source CTD sensors | Customizable conductivity, temperature, depth profiling [7] | Estuarine water quality monitoring; spatial and temporal variability assessment [7] |

| Cellular telemetry (VuLink) | Remote data transmission from field sensors [8] | Real-time data access from remote monitoring sites; global deployments [8] |

The validation studies comprehensively demonstrate that in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis serve complementary roles in environmental research. In-situ techniques provide unprecedented temporal resolution and real-time detection of dynamic processes, while laboratory methods deliver higher analytical precision and broader contaminant detection capabilities. The optimal monitoring strategy incorporates both approaches, leveraging their respective strengths to create a comprehensive understanding of environmental systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated approach enables both immediate intervention capabilities and definitive analytical characterization, supporting evidence-based decision-making in environmental management and public health protection.

In the field of environmental monitoring, the choice between traditional laboratory analysis and in-situ testing represents a critical decision point for researchers and drug development professionals. For decades, traditional laboratory methods have been regarded as the gold standard for environmental testing, providing unparalleled accuracy, precision, and regulatory compliance for analyzing air, water, and soil samples [9]. This comprehensive guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of established laboratory protocols against emerging in-situ alternatives within the context of environmental sample validation research.

The global environmental testing market, projected to expand from USD 7.43 billion in 2025 to USD 9.32 billion by 2030, reflects the growing importance of both methodologies [9]. While laboratory analysis remains foundational for its definitive measurements, technological innovations are accelerating the development of rapid, field-deployable solutions. Understanding the appropriate application for each method—whether utilizing laboratory precision or in-situ immediacy—is essential for designing environmentally valid research studies.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Traditional Laboratory vs. In-Situ Methods

Accuracy and Precision Metrics

Traditional laboratory analysis maintains its gold-standard status through demonstrated performance characteristics across multiple environmental parameters. The controlled environment of laboratories enables the application of highly sensitive techniques such as chromatography, mass spectrometry, and molecular spectroscopy, which offer detection capabilities often surpassing field-deployable alternatives [10].

For soil analysis in raw earth construction, strong correlations (R² = 0.8863) have been established between field tests like the cigar test and laboratory-measured plasticity index, validating field methods while confirming laboratory analysis as the reference point [11]. Similarly, ring test scores show significant correlation with laboratory-measured clay-sized particle content percentages, though laboratory methods provide more granular data (detecting clay content ranging from 5% to 75%) essential for precise material specification [11].

When monitoring emerging contaminants like perfluoroalkyl compounds (PFAS) in water matrices, laboratory-based methodologies offer significant advantages in sensitivity, accuracy, and selectivity compared to sensor technologies [10]. This precision is particularly crucial for drug development professionals requiring definitive contaminant identification in water sources used for pharmaceutical production.

Analytical Scope and Detection Capabilities

Traditional laboratories provide comprehensive analytical profiles essential for complex environmental assessments. Where in-situ methods typically target specific parameters, laboratory analysis can simultaneously detect diverse pollutant classes including heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, inorganic non-metallic pollutants, emerging contaminants, and biological agents [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Detection Capabilities

| Analytical Parameter | Traditional Laboratory Methods | In-Situ Testing Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Range | Broad-spectrum pollutant identification | Targeted parameter measurement |

| Sensitivity | Parts-per-trillion for specific contaminants | Generally parts-per-million to parts-per-billion |

| Selectivity | High (can distinguish structurally similar compounds) | Variable (potential cross-sensitivity) |

| Multi-analyte Capacity | Simultaneous analysis of multiple contaminant classes | Typically focused on single or few parameters |

| Standardization | Well-established protocols (EPA, ISO) | Emerging standardization frameworks |

The establishment of environmental monitoring networks and data-sharing platforms further enhances laboratory capabilities by providing solid data support for public health initiatives [12]. This infrastructure enables researchers to contextualize their findings within larger environmental trends.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Laboratory Protocols for Soil Analysis

Laboratory analysis of soil samples for construction applications follows rigorous standardized methodologies that enable reliable comparison across studies and locations [11]. The research integrating field tests with laboratory analyses for 39 soils from France's Nouvelle-Aquitaine region demonstrates the comprehensive nature of laboratory assessment.

The experimental protocol includes five standardized geotechnical tests:

- Particle size distribution analysis using sieve and hydrometer methods

- Atterberg limits determination (liquid limit, plastic limit, plasticity index)

- Methylene blue value (MBV) testing for clay activity assessment

- Organic matter content measurement through loss on ignition

- Density measurements using standardized compaction protocols

These laboratory methods provide quantitative data that validates field observations, with plasticity indices ranging from 0% to 50% across tested soils, enabling precise classification of material behavior [11]. The laboratory environment allows for careful control of testing conditions (temperature, humidity, sample preparation) that is not achievable in field settings.

Water Contaminant Analysis Protocols

For emerging water contaminants like PFAS, laboratory-based methodologies follow stringent protocols to ensure accuracy. Traditional approaches utilize liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which provides the sensitivity and selectivity required for regulatory compliance [10].

The experimental workflow involves:

- Sample preservation and transportation under controlled conditions

- Solid-phase extraction for analyte concentration and matrix clean-up

- Chromatographic separation using optimized mobile and stationary phases

- Tandem mass spectrometric detection with multiple reaction monitoring

- Quality control measures including blanks, spikes, and duplicates

These protocols enable detection at ng/L levels, which is essential for assessing contaminants of emerging concern that pose risks at minute concentrations [10]. While sensor technologies show promise for on-site screening, they currently lack the reliability for definitive quantification of emerging contaminants.

Protocol for Comparative Method Validation

Studies validating in-situ against laboratory methods follow rigorous experimental designs. The soil suitability assessment research employed statistical correlation analysis between field observations and laboratory measurements, establishing reliability metrics for traditional field tests [11]. This approach demonstrates how laboratory analysis serves as the reference method for validating alternative approaches.

Diagram 1: Method Validation Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Analytical Solutions

Laboratory Instrumentation and Reagents

Traditional laboratory analysis relies on sophisticated instrumentation and specialized reagents to achieve its gold-standard status. The environmental testing market encompasses various product categories that form the foundation of reliable analytical results [13].

Table 2: Essential Laboratory Research Reagents and Instruments

| Instrument/Reagent | Primary Function | Application in Environmental Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometers | Compound identification and quantification | PFAS, pesticide, and emerging contaminant analysis |

| Chromatography Systems | Separation of complex mixtures | VOC analysis, contaminant profiling |

| pH Meters | Acidity/alkalinity measurement | Water quality assessment, soil characterization |

| Molecular Spectroscopy Products | Structural analysis and concentration measurement | Organic matter characterization, contaminant identification |

| TOC Analyzers | Total organic carbon quantification | Water purity assessment, pollution tracking |

| Methylene Blue Reagent | Clay activity determination | Soil suitability for construction applications |

These instruments enable the precise measurements required for environmental research, particularly when assessing compliance with stringent regulatory limits for contaminants in various matrices [11] [13].

Emerging Sensor Technologies

While traditional laboratory methods provide definitive analysis, the scientific literature reveals growing development of alternative technologies for environmental monitoring. Printed sensors fabricated using techniques such as inkjet printing, screen printing, and roll-to-roll printing offer potential for cost-effective, large-scale deployment [14]. These sensors utilize advanced materials including graphene, carbon nanotubes, and conductive polymers to detect environmental parameters, though they face challenges in sensitivity, stability, and standardization compared to established laboratory techniques [14].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with both laboratory and field-deployable sensors represents a significant advancement, enabling more accurate predictions and enhanced data analysis capabilities [15]. AI-driven tools can process large volumes of data from sources such as satellite imagery, sensor networks, and historical datasets, offering insights that complement traditional laboratory findings [15].

Method Selection Framework for Environmental Research

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

The validation of in-situ monitoring against laboratory analysis requires understanding the distinct advantages and limitations of each approach. Traditional laboratory analysis provides definitive data for regulatory decisions, while in-situ methods offer temporal resolution and immediate insights [16] [10].

Table 3: Comprehensive Method Comparison

| Characteristic | Traditional Laboratory Analysis | In-Situ Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | High (gold standard) | Variable (technology-dependent) |

| Cost Structure | High capital and operational expense | Lower initial investment |

| Time to Results | Days to weeks (including transport) | Minutes to hours (real-time potential) |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established for compliance | Emerging acceptance for screening |

| Sample Integrity | Potential degradation during transport | Immediate analysis preserves sample state |

| Spatial Coverage | Limited by sampling logistics | Potential for dense sensor networks |

| Analytical Scope | Comprehensive contaminant profiling | Targeted parameter measurement |

| Quality Assurance | Established QC/QA protocols | Developing quality control frameworks |

Laboratory practices themselves face sustainability challenges, as they consume 5-10 times more energy than equivalent office space and generate an estimated 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste annually [17]. These environmental impacts present additional considerations for researchers designing studies with significant laboratory components.

Integrated Methodologies for Comprehensive Assessment

Rather than positioning traditional laboratory analysis and in-situ monitoring as mutually exclusive alternatives, emerging research frameworks advocate for integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of each methodology. The development of systems like HeatSuite, which monitors local environmental conditions alongside physiological responses, demonstrates the value of combining precise environmental measurements with contextual data [18].

Diagram 2: Integrated Assessment Strategy

For soil characterization in construction applications, research demonstrates that while traditional field tests provide reliable preliminary assessment tools, laboratory testing remains essential for final material validation [11]. This hybrid approach maximizes efficiency while maintaining scientific rigor—using field methods for rapid screening and laboratory analysis for definitive characterization of critical parameters.

Traditional laboratory analysis maintains its position as the gold standard for accuracy and precision in environmental testing, providing the definitive measurements required for regulatory compliance, method validation, and complex contaminant characterization. The experimental data and performance comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that laboratory methods offer unrivaled sensitivity, selectivity, and analytical scope for environmental samples.

Nevertheless, the evolving landscape of environmental research increasingly recognizes the value of integrated approaches that combine laboratory precision with in-situ monitoring capabilities. As sensor technologies advance and artificial intelligence enhances data interpretation, the scientific community moves toward frameworks that utilize each methodology's strengths—laboratory analysis for definitive quantification and in-situ methods for temporal resolution and spatial coverage.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, methodological selection should be guided by study objectives, regulatory requirements, and the specific performance characteristics needed. Traditional laboratory analysis remains indispensable when uncompromising accuracy and precision are paramount, while emerging technologies offer complementary capabilities that expand environmental monitoring possibilities.

Validating analytical methods is a cornerstone of environmental science, particularly in research supporting drug development where understanding the environmental fate of pharmaceuticals is critical. A central theoretical debate involves choosing between in-situ monitoring, which provides real-time, on-site data, and laboratory analysis, which offers high precision under controlled conditions. This framework objectively compares these paradigms by examining their performance across key metrics, supported by experimental data. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the specific research question, weighing factors such as required data precision, temporal resolution, and operational constraints [1].

Theoretical Foundations of the Two Paradigms

The theoretical distinction between in-situ and laboratory methods lies in their fundamental approach to data collection and the associated information each one captures.

In-Situ Monitoring is defined by its operation within the native environment of the sample. This paradigm prioritizes temporal resolution and contextual integrity, capturing dynamic processes like diurnal cycles or rapid pollutant pulses without the artifacts introduced by sample transport and storage [19] [1]. The core strength of this "seeing it happen" approach is its ability to provide a direct, real-time understanding of environmental systems.

Laboratory Analysis, in contrast, is built on the principle of controlled measurement. By removing samples from their environment and processing them under standardized, optimized conditions (e.g., controlled temperature, precise instrumentation, and specialized reagents), this paradigm maximizes analytical precision and accuracy [20] [3]. It is the benchmark for data quality, capable of detecting lower concentrations of a wider range of contaminants, including emerging pollutants analyzed via techniques like LC-MS/MS [21].

The following conceptual framework visualizes the decision-making logic for selecting the appropriate methodological paradigm.

Experimental Comparison and Performance Data

Direct comparisons in research studies reveal the quantifiable performance trade-offs between these two methodologies.

Case Study 1: Soil Spectroscopy

A 2022 study directly compared in-situ (field) and laboratory Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy (MIRS) for predicting key soil properties, using statistical metrics like the Ratio of Prediction to Interquartile distance (RPIQ) to gauge accuracy [3]. A higher RPIQ indicates a more accurate model.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Lab vs. In-Situ MIRS for Soil Analysis [3]

| Soil Property | Laboratory MIRS (RPIQ) | In-Situ MIRS (RPIQ) | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Carbon (OC) | 4.3 (Highly Accurate) | 1.89 (Satisfactory) | Soil moisture content negatively impacted field accuracy, especially in sandier soils. |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | 6.7 (Highly Accurate) | 1.89 (Satisfactory) | Field MIRS required complex "spiked" calibrations to match lab-detected tillage effects. |

| Clay Content | 0.89 - 2.8 (Variable) | Lower than OC/TN | Accuracy was more variable for both methods, but moisture had less negative impact than on OC. |

Experimental Protocol: Surface MIRS measurements were taken at three sites in Germany with different tillage treatments. Soil samples (0–2 cm) were then collected from the same spots for lab MIRS analysis on dried and ground material. Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) models were built using various calibration strategies, from purely local to regional models supplemented ("spiked") with a few local samples [3].

Theoretical Implication: This study demonstrates that while laboratory analysis provides superior accuracy, in-situ methods can achieve satisfactory results for specific properties (like OC and TN) but require more complex and arduous calibration procedures to compensate for environmental variables like moisture.

Case Study 2: Water Quality Monitoring

A 2025 study evaluated the feasibility of in-situ Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) for monitoring nutrients in dynamic rivers, comparing them to online analysers and laboratory Ion Chromatography (IC) [19].

Table 2: Performance of In-Situ ISEs for River Water Monitoring [19]

| Analyte | In-Situ ISE Performance | Comparative Method |

|---|---|---|

| Chloride (Cl⁻) | Good agreement | Laboratory IC |

| Nitrate (NO₃⁻) | Good agreement | Optical UV Probe & Laboratory IC |

| Ammonium (NH₄⁺) | Not comparable at low concentrations | Photometric/Gas-Sensitive Analyser & Laboratory IC |

| All Parameters | Effective for qualitative "event detection" (e.g., pollution spikes) | All Methods |

Experimental Protocol: ISEs from three manufacturers were deployed at a river monitoring station for five months, collecting data at 5-minute intervals. Concurrently, grab samples were taken for laboratory IC analysis, and data from other online analysers (e.g., photometers, UV probes) was recorded. The ISE data was evaluated for challenges like temperature fluctuations, interfering ions, and long-term drift [19].

Theoretical Implication: The feasibility of in-situ sensors is highly analyte-dependent. They excel at tracking relative changes and detecting pollution events, but their accuracy for quantitative analysis, especially at low concentrations, can be compromised by environmental interferences, necessitating careful validation against laboratory standards.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of both in-situ and laboratory analyses relies on specialized materials and reagents. The following toolkit details essential items for the experiments cited in this framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | Potentiometric sensor for detecting specific ions (e.g., NH₄⁺, NO₃⁻) in water. | In-situ water quality monitoring [19] |

| Chitin-based Bioanode | A slow-release carbon source that sustains exoelectrogenic microbes in a Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC). | Used in self-powered in-situ dissolved oxygen sensors [22] |

| Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler (POCIS) | A passive sampler that accumulates contaminants from water over time for laboratory analysis. | Provides time-weighted average concentrations for contaminants like pharmaceuticals [21] |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry to prevent instrument contamination and ensure accuracy. | Essential for laboratory analysis of emerging contaminants (e.g., PFAS, pharmaceuticals) in environmental samples [21] |

| Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectrometer | Instrument that measures molecular absorption of MIR light to characterize soil composition. | Used for both field (in-situ) and laboratory soil analysis [3] |

Integrated Workflow for Method Validation

Given their complementary strengths, a hybrid approach that strategically combines in-situ and laboratory methods provides the most robust validation. The following workflow diagrams a recommended protocol for such a study, derived from the cited experimental designs.

This theoretical framework demonstrates that the choice between in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis is a strategic trade-off. In-situ monitoring provides unparalleled temporal resolution and context for dynamic systems, while laboratory analysis delivers superior precision and breadth of analytes for definitive quantification [20] [19] [3]. The most robust research outcomes are achieved not by choosing one paradigm over the other, but by implementing a hybrid approach. This integrated methodology uses high-frequency in-situ data to capture critical environmental events and patterns, which are then validated and quantified through targeted, high-precision laboratory analysis. This synergistic strategy ensures data integrity and provides a comprehensive understanding of environmental samples, ultimately supporting more informed decision-making in drug development and environmental health research.

The Critical Need for Validation in Regulatory and Research Contexts

In the realms of regulatory compliance and scientific research, the data generated from environmental monitoring forms the bedrock of decision-making, from pharmaceutical cleanroom control to watershed management. The unwavering quality of analytical output is not merely advantageous but essential, serving as the foundation for legal defensibility, research reproducibility, and ultimately, public and environmental health protection [24]. The credibility of an environmental laboratory rests upon a robust validation framework that proves its methods yield reproducible and accurate results [25]. This article provides a critical comparison between in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis, presenting validation data and experimental protocols that highlight the necessity of a context-dependent approach to environmental sampling and analysis. As global challenges such as emerging contaminants like perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) intensify, the pressure on analytical infrastructure to provide accurate, timely, and contextually rich data has never been greater [10] [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Monitoring Approaches

The choice between in-situ and laboratory analysis involves navigating a complex landscape of trade-offs between accuracy, precision, cost, and operational feasibility. The following tables summarize critical performance and operational metrics based on comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of In-Situ versus Laboratory Analysis

| Parameter | In-Situ Monitoring | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Accuracy (Example: pH) | Within ±0.2 units [26] | High sensitivity and accuracy on calibrated equipment [10] [26] |

| Precision & Data Variability | Higher variance, especially with short half-life contaminants [27] | Lower variability; tightly controlled conditions [27] [26] |

| Key Limiting Factors | Environmental interference (temp, humidity); instrument recalibration needs [26] | Sample stability during transport; chain-of-custody integrity [24] |

| Best Application Context | Quick decision-making, trend spotting, high-frequency screening [26] | Regulatory compliance, definitive quantification, method development [10] [25] |

Table 2: Operational and Economic Considerations

| Consideration | In-Situ Monitoring | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of Results | Minutes to hours [26] | 5-10 business days, plus shipping [26] |

| Cost Profile | Low-cost, high-frequency option; one-time instrument purchase [26] | Higher cost per sample; depth of insight can justify expense [26] |

| Analyte Range | Limited to pH, EC, DO, temperature; some semi-quantitative kits for nutrients [26] | Comprehensive: macronutrients, trace metals, pesticides, emerging contaminants [10] [26] |

| Data Documentation | Prone to human error; rarely meets strict audit trail requirements [26] | Standardized reports with QC; legally defensible; suitable for compliance [24] [26] |

Experimental Validation Protocols for Method Comparison

A rigorous, protocol-driven approach is fundamental to validating any monitoring method. The following sections detail specific experimental designs that have been employed to generate the comparative data discussed in this article.

Protocol 1: Modeling Pulsed Aquatic Exposure Scenarios

Objective: To quantitatively compare the accuracy of discrete grab sampling versus integrative passive sampling in estimating time-weighted average (TWA) concentrations of contaminants with short, pulsed aquatic half-lives [27].

- Exposure Scenario Design: A known peak 96-hour TWA concentration was modeled, simulating a single contamination pulse. The dissipation of the contaminant followed first-order kinetics with a range of aquatic half-lives (0.5, 2, and 8 days) [27].

- Sampling Method Simulation:

- Discrete Sampling: Simulated by taking single, instantaneous concentration measurements from the model.

- Integrative Sampling: Simulated as a continuous accumulation of the contaminant over the deployment period, providing a true TWA [27].

- Variable Testing: The modeling exercise was run with 1,000 iterations for each combination of sampling method (discrete vs. integrative), sampling frequency (1 to 7 samples over 96 hours), and contaminant half-life [27].

- Validation & Analysis: For each iteration, the measured or estimated TWA was compared to the known true TWA. Accuracy was assessed by calculating the percentage of results that fell within 50% and 10% of the true value [27].

Protocol 2: Field Validation of Low-Cost Colorimetric Kits

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy, precision, and bias of low-cost colorimetric phosphate and nitrate test kits used by citizen scientists against accredited laboratory methods [28].

- Paired Sample Collection: During mass sampling events on the River Wye, volunteers collected water samples and immediately performed in-situ analysis using three test kits: Hanna Phosphate Checker, Hach Nitrate Test Strips, and La Motte Phosphate Insta-Test Strips. A second, preserved sample was simultaneously collected from the same location for accredited (UKAS ISO/IEC 17025) laboratory analysis [28].

- Controlled Lab Testing: To understand bias in field kits, controlled laboratory tests were conducted to investigate the influence of water temperature and the time between test initiation and analysis on the reported results [28].

- Data Analysis: The performance of each low-cost test was quantified by comparing its result directly with the paired laboratory result. Agreement was defined based on the accuracy required for the monitoring context. Precision and systematic bias were also statistically assessed [28].

Protocol 3: Validation of a Predictive Model for API Concentrations

Objective: To develop and validate a new method combining emission and hydrodynamic modeling to predict spatiotemporal concentrations of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) in a lake, offering an alternative to resource-intensive monitoring [29].

- Model Development: An emission model predicted API concentrations in wastewater effluent based on Swedish prescription data, factoring in human metabolization and WWTP retention. This was coupled with a 3D hydrodynamic model of Lake Ekoln, Sweden, which simulated dilution, transport, and temperature-dependent biodegradation of over 500 APIs [29].

- Validation Against Physical Measurements: The model's predictions were validated against two datasets:

- WWTP Effluent: 103 monthly measurements of 10 different APIs at the treatment plant effluent.

- Lake Water: 321 historical measurements of 20 different APIs from various points in the lake [29].

- Acceptance Criteria: Predictive accuracy was measured by the percentage of results that fell within a factor of 10 and a factor of 100 of the empirically measured concentrations [29].

Visualizing the Method Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized validation workflow for evaluating an environmental monitoring method, integrating principles from the experimental protocols described above.

Validation Workflow

Essential Research Reagent and Material Solutions

The execution of reliable environmental monitoring and validation studies depends on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used across the featured protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Monitoring

| Item or Solution | Function and Application in Validation |

|---|---|

| Integrative Passive Samplers (e.g., POCIS) | Continuously accumulates freely dissolved contaminants from water over a deployment period, providing a Time-Weighted Average (TWA) concentration for validating against grab samples [27]. |

| Optical Sensor Spots (O₂/CO₂) | Affixed to growth surfaces in cell cultures or environmental vessels for in-situ, real-time, non-invasive monitoring of dissolved gas concentrations, validating environmental stability [30]. |

| Colorimetric Test Kits (Nitrate/Phosphate) | Low-cost, field-deployable reagents that produce a color change indicative of analyte concentration. Used for comparing performance (accuracy, bias) against reference lab methods [28]. |

| Sample Preservation Reagents | Chemicals (e.g., acid for metals, quenching agents for chlorine) added to samples during collection to maintain analyte stability from field to lab, ensuring integrity for reference analysis [24]. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) Samples | Commercially provided samples of known but undisclosed concentration, used as an external audit to objectively validate a laboratory's analytical competence and method performance [24]. |

| Hydrodynamic & Emission Models | Computational tools (software and algorithms) that predict the fate and transport of contaminants in water bodies, serving as a supplement or guide for physical chemical monitoring [29]. |

The critical need for validation in regulatory and research contexts is unambiguous. Whether relying on rapid in-situ screens or definitive laboratory measurements, the data that informs decisions must be grounded in demonstrated competence and proven methodology. The comparative data and experimental protocols presented herein underscore that no single approach is universally superior; each has its place within a holistic monitoring strategy. The emerging integration of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning with sensor innovations promises to further enhance real-time monitoring capabilities [10]. Ultimately, a rigorous, validated framework—whether for monitoring a pharmaceutical cleanroom, a river catchment, or a cell culture environment—is the indispensable link between raw data and trustworthy knowledge, ensuring that scientific outcomes remain relevant, reproducible, and legally defensible [24].

In environmental research and drug development, the choice between in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis is fundamental, influencing data accuracy, temporal resolution, and operational cost. In-situ monitoring involves deploying sensors directly in the environment or process stream, providing real-time, high-frequency data that captures dynamic changes as they happen [31]. Conversely, laboratory techniques involve collecting discrete samples for subsequent, often more precise, analysis under controlled conditions using specialized instrumentation [32]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two paradigms, providing a structured overview of common technologies, their capabilities, and their validation against reference methods.

Comparative Analysis of In-Situ and Laboratory Techniques

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics for a range of common monitoring technologies used in environmental science.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of In-Situ Sensor Technologies

| Technology | Typical Measured Parameters | Key Performance Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma Spectrometry [32] | 226Ra, 40K, 137Cs | Higher minimum detectable activity; Major uncertainty from soil humidity (55%) [32] | Operational & emergency monitoring of nuclear facilities; environmental radioactivity [32] |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) [33] | Cu, Pb, Zn, and other metals | In-situ measurement in <5 minutes; Definitive quantitation after lab prep (R²>0.90) [33] | Rapid biomonitoring of metal pollution in mosses and other biological monitors [33] |

| Marine CO₂ Sensors [34] | pH, pCO₂ (partial pressure of CO₂) | Sufficient accuracy for short-term/seasonal studies; enables derived parameters (DIC within ±5 μmol/kg) [34] | Ocean acidification studies; air-sea CO₂ flux measurements; marine carbon cycle [34] |

| Soil Matric Potential Sensors [35] | Soil water potential (suction) | Enables field-derived soil water characteristic curves; wide measurement range beyond tensiometers [35] | Irrigation scheduling; geotechnical engineering studies; soil-plant-atmosphere continuum research [35] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Laboratory Analytical Techniques

| Technique | Typical Measured Parameters | Key Performance Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Gamma Spectrometry [32] | 226Ra, 40K, 137Cs | Lower minimum detectable activity; Major uncertainty from net counting (71%) [32] | Validation of in-situ data; precise quantification of radionuclides in soil/water [32] |

| ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry) [33] | Multi-element metal analysis | Used as a reference method for validating other techniques like XRF; requires sample digestion [33] | High-accuracy determination of metal concentrations in environmental, biological samples [33] |

| Benchtop Seawater CO₂ Analysis [34] | pH, pCO₂, DIC, AT | High-precision measurements used to assess accuracy of autonomous in-situ sensors [34] | Climate and ocean acidification research; calibration of sensor networks [34] |

| Chilled Mirror Dewpoint Hygrometer / HYPROP [35] | Soil water potential | Laboratory benchmark for generating soil water characteristic curves (SWCC) [35] | Soil physics research; hydraulic property characterization [35] |

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Paired In-Situ and Laboratory Methods

| Comparison Aspect | In-Situ Gamma Spectrometry [32] | Laboratory Gamma Spectrometry [32] |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Detectable Activity (MDA) | Higher | Lower |

| Repeatability & Reproducibility | Lower | Higher |

| Major Source of Uncertainty | Soil humidity (55% contribution) | Net counting rate (71% contribution) |

| Throughput & Cost | Faster, less costly per site | Slower, higher cost per sample |

| Agreement | Good agreement for 40K, 226Ra, 137Cs demonstrated | Good agreement for 40K, 226Ra, 137Cs demonstrated |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

This protocol outlines the steps for using portable XRF for direct field measurement and laboratory analysis of moss samples to monitor atmospheric metal pollution, with validation via ICP-OES.

A. Field Measurements (In-Situ XRF):

- Site Selection: Identify epiphytic moss (e.g., Orthotrichum lyelli) growing on tree trunks at least one meter off the ground to avoid contaminants.

- Instrument Setup: Use a portable XRF analyzer (e.g., Bruker Tracer III-SD) with a protective gridded window and a yellow filter (0.001″ Ti, 0.012″ Al). Settings: voltage 40 keV, current 25 µA, no vacuum.

- Measurement: Visually inspect the moss mat to ensure it is green and covers the instrument window. Place the nozzle directly against the moss to compact it. Acquire spectra for 60 seconds per assay. Take measurements from three different moss mats per tree to capture micro-scale variation.

- Quality Control: Wear powder-free nitrile gloves. Wipe the instrument nozzle with a lint-free tissue before each measurement.

B. Field Sample Collection (for Lab XRF and ICP-OES):

- Collection: Using gloves, collect approximately 30 g (dry weight) of moss from 3-10 mats on the same tree, including those measured in-situ.

- Storage: Place the material in sterile polyethylene bags, seal them, and store at 4°C until analysis.

C. Laboratory XRF Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: Clean, sort, and dry the moss. Grind the dried moss to a homogeneous powder and press it into a pellet using pure-aluminum oven dishes and ceramic tools to avoid contamination.

- Measurement: Analyze the pellet using the same portable XRF instrument with identical settings as used in the field.

D. Validation via ICP-OES:

- The moss pellets are subsequently digested using acid digestion protocols.

- The digestate is analyzed using ICP-OES to determine reference mass fractions of metals.

- XRF results (both in-situ and laboratory) are statistically compared (e.g., linear regression) against ICP-OES data to determine accuracy (with lab XRF achieving R² > 0.90 for definitive quantitation).

This protocol describes a systematic laboratory-based evaluation of the performance of autonomous sensors against benchtop reference measurements.

- A. Experimental Setup:

- Test Tank: A 5000 L seawater tank is used to create a controlled environment.

- Condition Variation: Tank conditions (e.g., Total Alkalinity (AT), pH, pCO₂, temperature, salinity) are artificially varied over a ~12-day period to encompass a wide range of values.

- B. Sensor Deployment:

- A suite of up to 10 autonomous in-situ sensors (e.g., for pH, pCO₂, AT) are immersed in the tank and set to log data according to their standard operating procedures.

- C. Reference (Benchmark) Measurements:

- Discrete water samples are collected from the tank throughout the experiment.

- These samples are analyzed using high-precision benchtop instrumentation (e.g., for pH, pCO₂, Dissolved Inorganic Carbon (DIC), and AT) to establish "ground truth" values.

- D. Data Analysis and Validation:

- Accuracy Assessment: Sensor readings are directly compared against the results from the discrete sample analysis.

- Internal Consistency Check: The marine CO₂ system parameters are cross-verified. For example, pCO₂ values measured directly by a sensor are compared against pCO₂ values calculated from measured AT and pH, to evaluate the internal consistency of the data.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflows for in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis, highlighting their parallel paths and the critical point of data comparison and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting the experiments described in the featured protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example Context / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Portable XRF Analyzer [33] | Direct, non-destructive elemental analysis in the field or lab. | Measurement of Cu, Pb, Zn concentrations in epiphytic moss [33]. |

| ICP-OES Instrument [33] | High-accuracy, multi-element analysis of digested samples; used as a reference method. | Validation of XRF measurements for metal quantitation [33]. |

| Sterile Polyethylene Sampling Bags [33] | Inert container for sample collection and storage, preventing contamination. | Storage of collected moss samples after field measurement [33]. |

| Pure-Aluminum Oven Dishes / Ceramic Blades [33] | Metal-free tools for sample preparation to avoid introducing contaminants. | Grinding and pelletizing moss samples for laboratory XRF analysis [33]. |

| Powder-Free Nitrile Gloves [33] | Prevent contamination of samples from oils and particulates on hands. | Mandatory during field measurement and sample handling [33]. |

| Autonomous pH/pCO₂/AT Sensors [34] | Continuous, in-situ measurement of marine carbonate system parameters. | Inter-comparison study of ocean CO₂ measurements in a controlled tank [34]. |

| TEROS 21 / MPS 6 Sensor [35] | Measures soil water potential (matric potential) in situ over a wide range. | Generating field-derived soil water characteristic curves (SWCC) [35]. |

| Chilled Mirror Dewpoint Sensor / HYPROP [35] | Laboratory benchmark instruments for generating soil water characteristic curves. | Creating reference SWCCs for comparison with in-situ derived curves [35]. |

Deployment and Analysis: A Practical Guide to Methodologies

In environmental health research, particularly concerning hazardous drug contamination, accurately assessing exposure risk is paramount for protecting healthcare workers. A key challenge lies in the methodological divide between highly accurate, yet slow, laboratory analysis and rapid, on-site screening tools whose real-world performance must be validated. This guide objectively compares these two paradigms—conventional laboratory-based wipe sampling and a novel, in-situ lateral flow immunoassay—framed within a broader thesis on validating field methods against laboratory benchmarks. The necessity for such comparison is underscored by the deleterious health effects, including reproductive toxicity and genotoxic effects, associated with occupational exposure to hazardous drugs [36]. This guide provides a detailed comparison based on a side-by-side validation study, offering researchers a framework for evaluating analytical methods intended for environmental monitoring [36] [37].

Comparative Performance Data: Field Immunoassay vs. Laboratory LC-MS/MS

A controlled laboratory study directly compared the performance of a novel lateral-flow immunoassay (LFIA) system (HD Check) with the conventional wipe sampling and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis for detecting hazardous drug contamination on surfaces [36]. The following tables summarize the key quantitative findings for the two drugs investigated, methotrexate (MTX) and cyclophosphamide (CP).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Monitoring Methods for Methotrexate (MTX)

| Drug & HD Check LOD | Test Concentration (ng/cm²) | HD Check Result (Positive/Trials) | Conventional Method Result (Mean ng/cm²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate (LOD = 0.93 ng/cm²) [36] | 0 (Control) | 0/10 | Not Detected |

| 50% of LOD (0.465 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | 0.457 | |

| 75% of LOD (0.698 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | 0.690 | |

| 100% of LOD (0.93 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | 0.919 | |

| 200% of LOD (1.86 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | 1.854 |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Monitoring Methods for Cyclophosphamide (CP)

| Drug & HD Check LOD | Test Concentration (ng/cm²) | HD Check Result (Positive/Trials) | Conventional Method Result (Mean ng/cm²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide (LOD = 4.65 ng/cm²) [36] | 0 (Control) | 0/10 | Not Detected |

| 50% of LOD (2.325 ng/cm²) | 9/10 | Data Available in [36] | |

| 75% of LOD (3.488 ng/cm²) | 9/10 | Data Available in [36] | |

| 100% of LOD (4.65 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | Data Available in [36] | |

| 200% of LOD (9.30 ng/cm²) | 10/10 | Data Available in [36] |

Key Findings from Comparative Data

- High Reliability for MTX: The HD Check system demonstrated 100% detection across all tested concentrations for methotrexate, including levels below its stated limit of detection (LOD), showing high sensitivity for this drug [36].

- Variable Sensitivity for CP: For cyclophosphamide, the HD Check system showed 100% detection only at and above its LOD. At concentrations of 50% and 75% of the LOD, it detected the drug in 90% of trials (9 out of 10), indicating slightly less consistent sensitivity at lower concentrations [36].

- Quantitative Accuracy of Conventional Method: The conventional LC-MS/MS method accurately quantified the drug concentrations with a high degree of accuracy and reproducibility, serving as a reliable reference for the qualitative HD Check system [36].

Experimental Protocols for Side-by-Side Comparison

The following workflow and detailed methodology outline the protocol used for the direct comparison of the two monitoring methods, providing a template for researchers designing similar validation studies [36].

Detailed Methodology

1. Test Surface Preparation: The study used 10 cm x 10 cm stainless steel plates to simulate the work surface of biological safety cabinets where hazardous drugs are typically prepared [36].

2. Drug Concentration Ranges: For each drug (MTX and CP), five different concentrations were tested. These ranged from 0 ng/cm² (control) to 200% of the manufacturer's stated Limit of Detection (LOD) for the HD Check system (0.93 ng/cm² for MTX and 4.65 ng/cm² for CP). Intermediate concentrations of 50% and 75% of the LOD were also included [36].

3. Sample Collection Protocol:

- Application and Drying: A 50 µl volume of the known drug concentration was applied to each test plate and allowed to dry naturally for approximately 15 minutes [36].

- Wiping Procedure: A single trained individual performed all wiping to minimize variability. The wiping pattern consisted of a back-and-forth motion in the vertical direction, followed by a back-and-forth motion in the horizontal direction.

- For the conventional method, a Whatman filter moistened with a solution of water/methyl alcohol (20:80) with 0.1% formic acid was used. The wipe was folded to expose a fresh side before the horizontal wipe [36].

- For the HD Check system, the proprietary wiping materials and procedure supplied with the test kit were followed [36].

- Replication: For each drug and each concentration, 10 replicate samples were collected for each method, resulting in 100 test plates per drug [36].

4. Sample Analysis:

- Conventional Analysis: Wipes from the conventional method were transported to a laboratory and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) to obtain precise quantitative results (ng/cm²) [36].

- HD Check Analysis: The HD Check cassettes were inserted into the system's digital reader according to the manufacturer's instructions, which provided a qualitative positive or negative result within minutes [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Environmental Monitoring Validation Studies

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Stainless Steel Test Plates | A non-porous, standardized surface (e.g., 10cm x 10cm) that mimics real-world workstations in biological safety cabinets for controlled contamination studies [36]. |

| Hazardous Drug Standards | Pure analytical standards of the target compounds (e.g., Methotrexate, Cyclophosphamide) used to create precise calibration curves and spiked samples for method validation [36]. |

| Conventional Wipe Samplers | Typically consisting of Whatman filters or similar wipes, moistened with a collection solvent (e.g., water/methanol with formic acid), for standardized surface sampling and subsequent lab analysis [36]. |

| HD Check System | A commercial lateral-flow immunoassay kit containing all necessary components (wipes, cassettes, digital reader) for near real-time, qualitative detection of specific hazardous drugs on surfaces [36]. |

| HPLC-MS/MS System | The gold-standard laboratory instrument for quantifying trace levels of chemical contaminants. It provides high sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility for validating the performance of field-based methods [36]. |

| Solvents for Extraction | High-purity solvents (e.g., methanol, water, formic acid) used to extract analytes from wipe samples and for mobile phases in chromatographic analysis [36]. |

In environmental research, the choice between in-situ monitoring and laboratory analysis represents a fundamental trade-off between ecological realism and experimental control. The validation of data derived from field-deployed sensors is paramount, as uncalibrated measurements are merely assumptions, while calibrated measurements constitute scientific truth [38]. Sensor calibration is a foundational practice that configures a sensor to output accurate and reliable readings that match known physical quantities, thereby minimizing measurement uncertainty [39]. This process is particularly crucial in environmental monitoring where data informs public health advisories, pollution control measures, and regulatory compliance [39] [38].

Environmental sensors are inherently susceptible to drift—a gradual deviation from their calibrated state—due to exposure to environmental stressors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity variations, and particulate accumulation [40]. Without proper calibration and maintenance, the data collected can be misleading, resulting in flawed analyses, ineffective mitigation strategies, and potentially harmful policies [39]. This guide objectively compares the performance of in-situ versus laboratory-based approaches, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data validation frameworks necessary for generating defensible environmental data.

Comparative Analysis: In-Situ versus Laboratory-Based Sensing

The decision to deploy sensors in the field or conduct analyses in the laboratory significantly impacts the type, quality, and applicability of the resulting data. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of In-Situ and Laboratory-Based Sensing Approaches

| Feature | In-Situ Sensing | Laboratory-Based Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Context | Real-time, in the actual environment [2] | Controlled laboratory conditions [2] |

| Temporal Resolution | Continuous, real-time data streams [2] | Discrete, with significant time delays (days to weeks) [2] |

| Ecological Representativeness | High, captures natural variability and site-specific conditions [16] [41] | Lower, may not reflect complex real-world interactions [2] [41] |

| Data Accuracy (Control) | Can be affected by fouling, drift, and environmental interference [2] [40] | High precision under controlled conditions; can detect trace contaminants [2] |

| Key Operational Challenges | Sensor drift, biofouling, required maintenance, and harsh environmental exposure [2] [40] | Sample transport and preservation, limited throughput, high cost per sample [2] |

| Best Suited For | Continuous monitoring, trend detection, and understanding real-world system behavior [2] [16] | Regulatory compliance, precise quantification, and research requiring extensive, controlled analysis [2] |

Environmental Stressors and Sensor Performance

Field-deployed sensors face a hostile environment that directly impacts their accuracy and longevity. Understanding these stressors is essential for designing robust monitoring campaigns and appropriate calibration intervals.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Temperature changes cause physical expansion or contraction of sensor materials and components, leading to misalignment, material stress, and electronic variability that disrupt the sensor's calibrated state [40].

- Humidity Variations: High humidity can cause condensation on sensor components, potentially resulting in short-circuiting or corrosion [40]. Conversely, low humidity can desiccate certain sensor elements, altering their chemical balance and responsiveness [40].

- Dust and Particulate Accumulation: Particulate matter (e.g., dust, pollen) can physically settle on and obstruct sensor elements, reducing their sensitivity and altering their response. This buildup is a common cause of calibration drift, particularly in arid or industrial environments [40].

Table 2: Impact of Environmental Stressors and Mitigation Strategies

| Environmental Stressor | Impact on Sensor Performance | Preventative Maintenance Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Dust & Particulates | Obstructs sensor elements; reduces sensitivity; causes false readings [40] | Regular cleaning with soft brushes/air blowers; use of protective housings or filters; strategic sensor placement [40] |

| High Humidity | Condensation leading to short-circuiting or corrosion; chemical reactions within sensors [40] | Protective housings; use of dehumidifiers; regular calibration checks; robust sensor design [40] |

| Temperature Extremes | Physical expansion/contraction of components; misalignment; electronic signal variability [40] | Use of sensors with materials resistant to thermal stress; regular recalibration; seasonal calibration checks [40] |

Calibration Fundamentals and Advanced Protocols

Calibration is the process of configuring a sensor to output values that accurately reflect the true concentration of the target analyte [38]. It involves exposing the sensor to calibration standards—reference materials or instruments with known, traceable values—and adjusting the sensor's output to match these known values [39].

Core Calibration Methods

- Single-Point Calibration: A simple adjustment at a single reference point, suitable only for sensors with a linear response and minimal drift [39].

- Two-Point Calibration: Adjustment at two reference points (typically low and high ends of the measurement range), which compensates for both offset and gain errors [39].

- Multi-Point Calibration: Adjustment at multiple points across the sensor's range, providing the highest accuracy and compensating for non-linearities in the sensor's response [39].

Field-Based Calibration Protocols

For field-deployed sensors, several established protocols exist to ensure data quality, each with varying levels of robustness and resource requirements.

1. Co-location Calibration (Type A1) This is the most robust field calibration method. It involves placing the field sensor alongside a certified reference measurement station for a defined period (several days to weeks) [38].

- Procedure: Data is collected simultaneously from both the field sensor and the reference instrument. The differences are analyzed, and adjustments are made to the field sensor's baseline (zero point) and span (sensitivity) to minimize discrepancies [38].

- Application: Recommended for new critical installations, audits, and deployments in highly regulated environments [38].

2. Certified Gas Calibration (Type A2) This method uses certified gas cylinders with known concentrations of the target analyte, traceable to international standards (e.g., NIST) [38].

- Procedure: A gashood is used to channel the certified gas directly to the sensor. The sensor's response is then adjusted to match the known concentration, primarily allowing for span adjustment [38].

- Application: Ideal for laboratories, industrial facilities, or for recalibrating stations on-site without dismantling them [38].

3. Field Calibration Using Linear and Nonlinear Methods Advanced statistical techniques can further enhance the accuracy of field-calibrated sensors, particularly for complex pollutants like particulate matter (PM2.5).

- Experimental Protocol: A study evaluating low-cost PM2.5 sensors collected data from both the low-cost sensors and a research-grade DustTrak monitor at a roadside location. The data was processed at different time resolutions (e.g., 20-minute intervals) [42].

- Data Analysis: The raw sensor data was calibrated using both linear regression and nonlinear machine learning methods (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting). Key environmental factors such as temperature, wind speed, and heavy vehicle density were included in the nonlinear models [42].

- Performance Outcome: The study concluded that nonlinear models significantly outperformed linear models, achieving a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.93 at a 20-minute resolution, thus meeting U.S. EPA calibration standards [42].

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the core calibration process and the decision framework for selecting a validation strategy.

Figure 1: The essential steps in the sensor calibration process, from standard selection to documentation [39].

Figure 2: A decision framework for selecting an appropriate calibration or analysis strategy based on availability and requirements [2] [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful deployment and validation of environmental sensors rely on a suite of essential tools and reagents. The following table details key items and their functions in calibration and monitoring experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Sensor Calibration

| Item | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Certified Gas Mixtures | Reference materials with known, traceable concentrations of target gases (e.g., CO, NOx, Ozone) used for calibrating gas sensors in the lab or field [39] [38]. |

| Standard Solutions | Aqueous solutions with known concentrations of specific parameters (e.g., pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen) used for calibrating water quality sensors [39]. |

| Gashood | A device that channels certified gas from a cylinder directly to a sensor's inlet, ensuring controlled exposure during field calibration (Type A2) [38]. |

| Research-Grade Reference Monitor | A high-accuracy instrument (e.g., beta attenuation monitor, gravimetric sampler, DustTrak) used as a benchmark in co-location studies to calibrate lower-cost field sensors [39] [42]. |

| Traceable Calibration Standards | Reference materials or instruments whose accuracy is verified through an unbroken chain of comparisons to national or international standards, ensuring data comparability [39]. |

The validation of in-situ monitoring against laboratory analysis is not a matter of choosing one superior method, but of understanding their complementary strengths and limitations. In-situ sensors provide high-resolution, ecologically relevant data that captures the dynamic nature of environmental systems, while laboratory analysis offers definitive, high-precision measurements under controlled conditions [2] [16] [41].

The key to robust environmental research lies in integrated validation protocols. This includes establishing rigorous, statistically sound field calibration routines—such as co-location with reference instruments or the application of nonlinear calibration models—that are tailored to the specific environmental stressors of the deployment site [42] [38]. Furthermore, pairing a limited number of laboratory-grade analyses with continuous in-situ sensor data can create a powerful framework for validating and scaling environmental observations [41]. By adopting these best practices in sensor calibration and deployment, researchers can generate the accurate, reliable, and defensible data necessary to advance our understanding of complex environmental challenges.

In environmental research, the journey of a sample from the field to the laboratory is a critical period where its integrity can be compromised, potentially invalidating data and derailing projects. Chain-of-Custody (CoC) is the systematic, documented process that tracks a sample's chronological journey, creating a verifiable trail that demonstrates the sample has been collected, handled, and preserved in a manner that prevents tampering, loss, or contamination [43] [44]. For researchers validating in-situ monitoring against laboratory analysis, a robust CoC is not merely administrative; it is the foundational practice that guarantees the comparability and credibility of data generated by these two methods. It provides the documented assurance that any variances detected are due to analytical differences and not to mishandling during the sample's transit and storage.

The consequences of a broken chain are severe. A study by the Innocence Project found that improper handling of evidence contributed to approximately 29% of DNA exoneration cases, highlighting the very real risk of data corruption [43]. In environmental sampling, failures can lead to misguided conclusions about contamination, incorrect resource calculations, and regulatory non-compliance, with significant financial and legal repercussions [45]. This guide objectively compares the protocols that underpin sample integrity, providing researchers with the framework to ensure their data is beyond reproach.

Core Principles and Components of Chain of Custody

The integrity of the chain of custody is upheld by several interdependent pillars, each serving as a critical checkpoint in a sample's lifecycle [43].

- Documentation: Every interaction with a sample must be documented to create a transparent and traceable history. This includes the "who, what, when, where, and why" of each handling event [43] [44].

- Secure Storage: Samples must be stored in a secure environment that protects them from tampering, contamination, or environmental degradation. Standards often require physical safeguards and specific environmental controls, such as refrigeration for biological samples [43].

- Transfer Protocols: The movement of samples from one custodian to another is a critical vulnerability. Strict protocols, including the use of sealed containers, documented handovers, and secure transport methods, are essential during these transfers [43].

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Adherence to clear, concise, and established SOPs ensures consistency and reliability across all operations, significantly reducing the risk of human error [43].

- Personnel Training: All individuals involved in the chain must be adequately trained. They must understand the importance of the CoC, the specific procedures to follow, and the implications of any breaches [43].

Table 1: Core Components of a Chain of Custody Protocol

| Component | Description | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation | Chronological record of all sample interactions [43] [44]. | Creates an auditable paper trail for verification. |

| Secure Storage | A controlled-access environment with appropriate conditions [43]. | Prevents unauthorized access and sample degradation. |

| Transfer Protocols | Formalized procedures for moving samples between custodians [43]. | Ensures integrity is maintained during transit. |

| Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Detailed, step-by-step instructions for all handling processes [43]. | Standardizes practice and minimizes human error. |

| Personnel Training | Education on the importance and execution of CoC protocols [43]. | Ensures all personnel are competent and aware of their role. |

Comparative Analysis: Field-Based vs. Laboratory-Based Integrity Measures

Validating in-situ monitoring against laboratory analysis requires an understanding of the different integrity challenges each method faces. The table below compares their key aspects, supported by data on common failure points.

Table 2: Comparison of Field vs. Laboratory Sample Integrity Management

| Aspect | Field Collection & In-Situ Monitoring | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Integrity Focus | Preventing contamination during collection and ensuring stabilization [45]. | Preventing mix-ups, cross-contamination, and ensuring proper storage conditions [43]. |

| Common Failure Modes | Improper container sealing; cross-contamination; lack of temperature control; incomplete field notes [45]. | Documentation gaps; mislabeling; improper storage temperatures; unauthorized access [43] [45]. |

| Quantitative Data on Failures | ~15% of evidence degradation incidents are due to improper environmental controls during storage/transit [43]. | Human error is the most pervasive challenge, with flaws like missing signatures being common [43] [46]. |

| Typical Technologies Used | Mobile apps with GPS; barcodes; tamper-evident bags; portable coolers [45]. | Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS); barcode scanners; secure, access-controlled freezers [43] [45]. |

| Key Documentation | Chain of Custody forms; sample log sheets; photographs of collection site [44] [47]. | Internal chain of custody forms; analysis worksheets; audit logs from LIMS [43] [48]. |

Experimental Protocols for Integrity Validation

To objectively compare and ensure the integrity of both field and lab processes, researchers can implement the following experimental quality control protocols:

- Sample Tracking Experiments: Purpose: To quantify the error rate in sample identification and tracking. Methodology: Process a batch of samples using traditional paper forms and a parallel batch using electronic tracking (e.g., barcodes or RFID). The metric for comparison is the number of transcription errors, misplaced samples, or documentation gaps per 100 samples [43] [45].

- Contamination Control Studies: Purpose: To assess the efficacy of contamination prevention protocols. Methodology: Introduce known quantities of a tracer compound into selected samples at the point of collection. During analysis in the lab, monitor control samples (blanks) for the presence of the tracer. The rate of tracer detection in blanks indicates the level of cross-contamination occurring during handling and analysis [45].

- Sample Stability Testing: Purpose: To validate storage and preservation conditions for specific analytes. Methodology: Collect a homogeneous set of samples and divide them. Analyze one subset immediately and store the others under different conditions (e.g., room temperature, 4°C, -20°C) for varying durations before analysis. The divergence of results over time establishes the allowable holding times and optimal storage conditions [43].

Visualization of the End-to-End Chain of Custody Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete lifecycle of a sample, from collection to final disposition, highlighting critical control points where integrity must be verified.

The workflow shows a linear process with three main phases: Field Operations (yellow), Transfer (blue), and Laboratory Operations (green), concluding with Reporting and Disposition (red). Each arrow represents a transfer of custody that must be documented on the CoC form to maintain an unbroken chain [43] [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Sample Integrity

Maintaining sample integrity requires specific tools and reagents at each stage of the process. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the context of environmental sampling.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Sampling

| Item/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|