Green Analysis of Pharmaceutical Residues: Leveraging Ionic Liquids as Advanced Analytical Solvents

This article explores the transformative role of ionic liquids (ILs) as green solvents in the analysis of pharmaceutical residues.

Green Analysis of Pharmaceutical Residues: Leveraging Ionic Liquids as Advanced Analytical Solvents

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of ionic liquids (ILs) as green solvents in the analysis of pharmaceutical residues. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination from foundational principles to practical applications. The content covers the unique tunable properties of ILs that make them 'designer solvents' for green analytical chemistry, their specific use in techniques like headspace gas chromatography for monitoring residual solvents, and advanced microextraction methods for environmental and biological samples. It further addresses critical challenges including toxicity assessments, method optimization, and validation protocols. By synthesizing the latest research, this review serves as a strategic guide for implementing robust, sustainable, and effective analytical methods that align with the principles of green chemistry while meeting stringent pharmaceutical quality control standards.

Ionic Liquids as Designer Solvents: Principles and Green Chemistry Alignment

The pursuit of sustainable and efficient methodologies in pharmaceutical analysis has catalyzed the shift from traditional organic solvents to advanced green solvents. Among these, Ionic Liquids (ILs) and Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) have emerged as versatile, tunable, and environmentally benign alternatives. Their unique physicochemical properties—such as negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, and tunable solubility—make them particularly suitable for the extraction, separation, and analysis of residual pharmaceuticals and impurities [1]. This document delineates the structures, properties, and key subclasses of ILs and DESs, providing application notes and detailed protocols for their use in green analytical chemistry.

Ionic Liquids (ILs): Definition and Core Structure

Ionic Liquids (ILs) are a class of organic salts, typically composed of bulky, asymmetric organic cations and organic or inorganic anions, that are liquid at temperatures below 100 °C [2] [3]. Unlike conventional molecular solvents, ILs consist entirely of ions, which confers their characteristic low vapor pressure and high thermal stability [2] [4].

The extensive possible combinations of cations and anions (theoretically up to 10¹⁸) allows for the precise tuning of their physicochemical properties, earning them the moniker "designer solvents" [3] [5].

- Common Cations: Include imidazolium (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium, EMIM), pyridinium, pyrrolidinium, and quaternary ammonium (e.g., choline) [2] [6].

- Common Anions: Encompass tetrafluoroborate (BF₄⁻), hexafluorophosphate (PF₆⁻), bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (NTf₂⁻), and chloride (Cl⁻) [2] [6].

Classification and Generations of Ionic Liquids

The evolution of ILs can be categorized into three generations, reflecting their developing functionality and biocompatibility [6] [5].

Table 1: Generations of Ionic Liquids

| Generation | Key Characteristics | Example Components | Primary Applications/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Low melting point, high thermal stability; sensitive to air and water [4] [5]. | Dialkylimidazolium cations with halogenoaluminate anions (e.g., AlCl₄⁻) [4]. | Electrochemistry and catalysis; limited by moisture sensitivity and toxicity [3] [5]. |

| Second Generation | Air- and water-stable; adjustable physical and chemical properties [6] [5]. | Imidazolium cations with [BF₄]⁻ or [PF₆]⁻ anions [4]. | Broad applications as green solvents and functional materials; some toxicity concerns persist [5]. |

| Third Generation | Low toxicity, good biodegradability, often derived from biological precursors [6] [5]. | Cholinium, betainium, or amino acid-based ions [5]. | Biopharmaceutical applications, including Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids (API-ILs) [6] [5]. |

Key Subclasses of Ionic Liquids

Protic Ionic Liquids (PILs)

Protic Ionic Liquids (PILs) are formed through a straightforward proton transfer from a Brønsted acid to a Brønsted base [3] [4]. This simple synthesis, often a neutralization reaction, distinguishes them from aprotic ILs, which require quaternization and anion exchange [3].

- Synthesis Protocol: Equimolar amounts of a pure Brønsted acid (e.g., nitric acid) and a Brønsted base (e.g., ethylamine) are mixed under controlled cooling, typically in an ice bath. The reaction is exothermic. The resulting liquid, ethylammonium nitrate, may require further purification steps such as vacuum drying to remove residual water or unreacted starting materials [3].

- Applications: PILs are particularly useful in applications where low-cost, simple synthesis is paramount, and in systems where proton activity is desired, such as in fuel cell electrolytes [2].

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids (API-ILs)

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-Ionic Liquids (API-ILs) represent a paradigm shift in drug formulation, where an ionizable API is paired with a biocompatible counterion to form a liquid salt [5] [7]. This strategy can address common pharmaceutical challenges like polymorphic instability, low solubility, and poor bioavailability [6] [5].

- Synthesis Protocol: A common method involves the metathesis of an API-containing salt (e.g., sodium ibuprofenate) with an ammonium-based salt (e.g., benzalkonium chloride) in a suitable solvent like deionized water or acetone [7]. The reaction proceeds as follows:

API⁻Na⁺ + Counterion⁺Cl⁻ → API⁻Counterion⁺ + NaCl↓The insoluble byproduct (e.g., NaCl) is removed by filtration, and the solvent is evaporated under reduced pressure to yield the pure API-IL [7]. - Applications: API-ILs are primarily investigated to enhance the delivery and performance of poorly soluble drugs, for instance, in transdermal patches or oral formulations, improving skin permeation or gastrointestinal absorption [5] [7].

Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs): Definition and Core Structure

Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) are mixtures of a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) and a Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) that, when combined in a specific molar ratio, form a eutectic mixture with a melting point significantly lower than that of each individual component [8]. The complex hydrogen-bonding network between the components is responsible for this profound freezing point depression [8].

A classic example is a mixture of choline chloride (HBA) and urea (HBD) in a 1:2 molar ratio. While choline chloride decomposes at 302°C and urea melts at 133°C, their combination results in a clear liquid with a freezing point of 12°C [8].

Classification of DESs

DESs are categorized into four main types based on their composition [8].

Table 2: Classification of Deep Eutectic Solvents

| Type | Components | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Quaternary ammonium salt + Metal Chloride | Choline Chloride + CuCl₂ |

| Type II | Quaternary ammonium salt + Metal Chloride Hydrate | Choline Chloride + CrCl₃·6H₂O |

| Type III | Quaternary ammonium salt + Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Choline Chloride + Urea (Reline) |

| Type IV | Metal Chloride Hydrate + Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | ZnCl₂·4H₂O + Urea |

Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) and Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Solvents (TheDESs) are subclasses of Type III DESs. NADES are composed of primary plant metabolites (e.g., sugars, organic acids, amino acids) [8], while TheDESs incorporate APIs as one or both components, similar in function to API-ILs, creating a liquid form of a drug for enhanced delivery [5].

Comparative Analysis: Properties and Applications

The properties of ILs and DESs make them superior to volatile organic solvents for many pharmaceutical applications.

Table 3: Comparative Properties and Applications of ILs and DESs

| Parameter | Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) |

|---|---|---|

| Vapor Pressure | Negligible [2] [1] | Negligible [8] |

| Thermal Stability | High, often >300°C [4] | Good, but generally lower than ILs [8] |

| Viscosity | Moderate to high (20 - 40,000 cP) [4] | Typically high, can be a limitation [8] |

| Synthesis | Multi-step, may require purification [3] | Simple, mix-and-heat; atom-economical [8] |

| Cost | Can be high, especially for complex ions | Generally low-cost, readily available components [8] |

| Toxicity & Biodegradability | Varies widely; 3rd gen (Bio-ILs) are greener [5] [1] | Often low toxicity and biodegradable, especially NADES [8] [1] |

| Key Pharmaceutical Applications | - Catalysis and synthesis [2] [6]- API-ILs for drug delivery [5]- Solvents in microextraction [9] | - Extraction of biomolecules [8]- TheDESs for drug delivery [5]- Green mobile phase additives [10] |

Application Note: Microextraction of Pharmaceutical Residues

Background

Liquid-phase microextraction using ILs or DESs provides a green, efficient, and miniaturized alternative to conventional liquid-liquid extraction for isolating drug residues from complex aqueous matrices (e.g., wastewater, biological fluids) prior to chromatographic analysis [9] [10]. The high affinity and selectivity of these solvents for target analytes improve pre-concentration and reduce organic solvent consumption.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To extract and pre-concentrate residual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen) from a simulated water sample using a hydrophobic DES.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): DL-Menthol (>95% purity).

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): Acetic acid (>99% purity).

- Standard Solution: Ibuprofen certified reference standard in methanol.

- Model Sample: Deionized water adjusted to pH 3 with hydrochloric acid.

- Equipment: 10 mL glass conical centrifuge tubes, analytical balance, magnetic hotplate stirrer, thermometer, micro-syringe, vortex mixer, and a HPLC system with UV detection.

Procedure:

- DES Synthesis: Weigh DL-menthol and acetic acid in a 1:2 molar ratio into a vial. Heat the mixture at 60°C under continuous stirring (300 rpm) on a magnetic hotplate until a homogeneous, clear liquid is formed (~30 minutes). Label this as the extraction solvent. Allow it to cool to room temperature. It should remain liquid.

- Sample Preparation: Spike deionized water (pH 3) with the ibuprofen standard to a final concentration of 1 µg/mL.

- Microextraction: a. Transfer 5 mL of the spiked sample into a 10 mL centrifuge tube. b. Using a micro-syringe, swiftly inject 100 µL of the synthesized DES directly into the sample solution. c. Vigorously vortex the mixture for 2 minutes to form a cloudy emulsion, ensuring maximum surface contact between the DES and the aqueous sample. d. Centrifuge the tube at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to break the emulsion and sediment the DES phase at the bottom of the tube.

- Analysis: a. Carefully retrieve ~80 µL of the sedimented DES phase using a micro-syringe. b. Dilute the extract with an appropriate volume of methanol or the HPLC mobile phase. c. Inject an aliquot into the HPLC system for quantification.

- Calculation: Determine the concentration of ibuprofen in the original sample by comparing the peak area to a calibration curve prepared from standard solutions.

Troubleshooting:

- No emulsion forms: Ensure the DES is hydrophobic. Check the synthesis and consider increasing vortex speed or time.

- DES does not sediment: Increase centrifugation speed or time. Ensure the density of the DES is sufficiently different from water.

- Low recovery: Adjust the sample pH to suppress the ionization of the target acid drug, favoring its partitioning into the organic DES phase. Optimize the volume of DES and extraction time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents for Working with ILs and DESs in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([C₄mim][PF₆]) | Hydrophobic IL for liquid-liquid microextraction [9]. | Extracting lipophilic pharmaceutical residues from aqueous samples. |

| Choline Chloride | Versatile, low-cost, and biocompatible HBA for DES synthesis [8]. | Preparing Type III DESs (e.g., with urea or glycerol) for biomass extraction. |

| DL-Menthol | Natural, biodegradable HBA or HBD for hydrophobic DESs [1]. | Forming low-viscosity DESs with fatty acids for drug microextraction. |

| Urea | Common HBD for forming low-melting-point DESs [8]. | Synthesizing the classic DES "Reline" with Choline Chloride (1:2). |

| Docusate (Dioctyl sulfosuccinate) | Biocompatible counterion for the formation of API-ILs [5]. | Converting a basic drug into an API-IL to enhance solubility and permeability. |

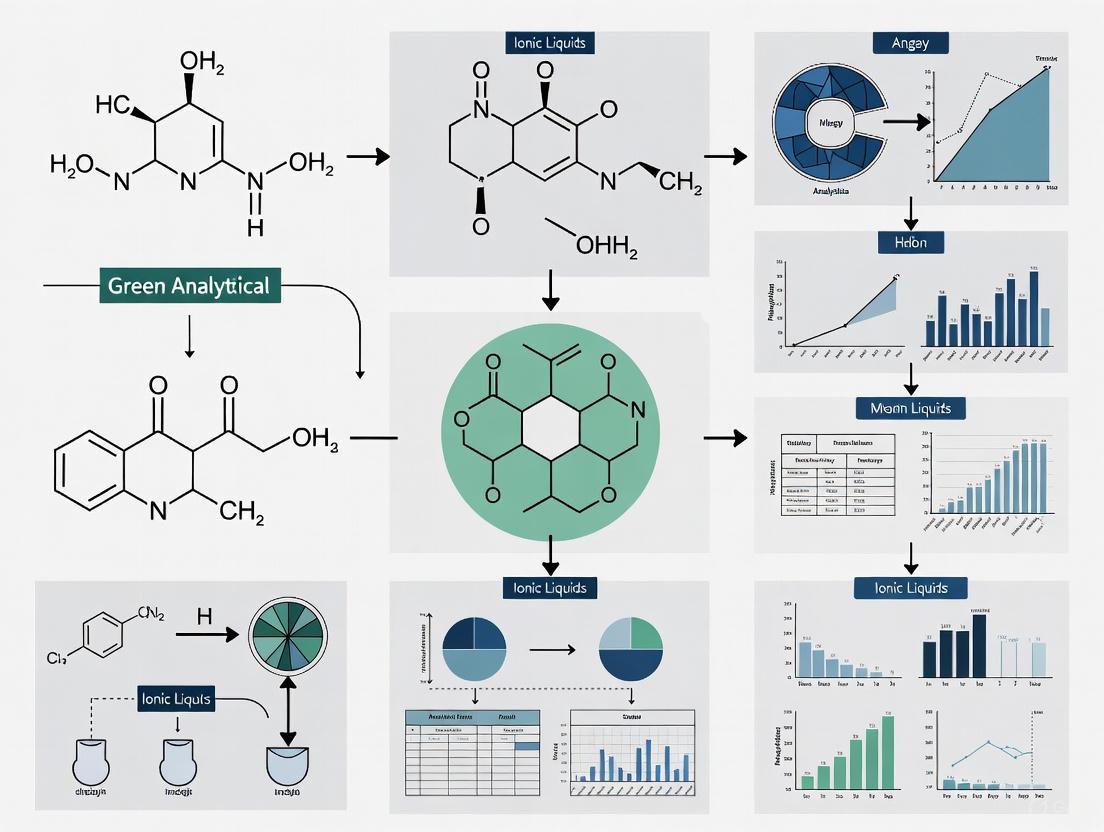

Logical Workflow and Structural Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical classification and relationship between the key solvents and subclasses discussed in this document.

Ionic liquids (ILs), a class of solvents with salt structures and melting points below 100°C, have emerged as transformative materials in analytical science. Their most defining characteristic is their status as "designer solvents" – their physicochemical properties can be precisely tuned by selecting and modifying their constituent organic cations and inorganic or organic anions [11]. This tunability allows researchers to design solvents with specific melting temperatures, viscosity, volatility, conductivity, and solubility to meet exact methodological requirements, often overcoming limitations of traditional organic solvents [11]. The capability to functionalize ILs with specific moieties has led to specialized subclasses including polymeric ionic liquids (PILs), magnetic ionic liquids (MILs), and chiral ionic liquids (CILs), each offering unique advantages for analytical applications [11].

In the context of green analytical methods, ILs provide an environmentally benign alternative to conventional volatile organic solvents due to their negligible vapor pressure and high thermal stability [12] [13]. This review details the application of these designer solvents, specifically within the framework of residual pharmaceutical analysis, providing both theoretical foundations and practical protocols for implementing IL-based methodologies.

Key Properties and Tunability of Ionic Liquids

The designer solvent concept originates from the intricate relationship between IL structure and function. By interchanging cations and anions or incorporating functional groups, analysts can engineer solvents with optimized properties for specific applications.

Core Physicochemical Properties

The properties of ILs most relevant to analytical science include:

- Negligible vapor pressure: Prevents solvent evaporation and atmospheric release, enhancing workplace safety and enabling high-temperature operations [12] [14].

- High thermal stability: Allows use at elevated temperatures (often >140°C in HS-GC) without degradation, improving extraction efficiency and sensitivity [12].

- Variable viscosity: Affects diffusion rates and mass transfer, can be modulated through cation alkyl chain length and anion selection [15].

- Broad electrochemical windows: Enable applications in electrochemistry and sensors [16].

- Dual nature polarity: Can dissolve both polar and non-polar compounds, enhancing extraction capabilities [11].

Structural Tunability and IL Subclasses

The ability to fine-tune these properties has led to advanced IL subclasses with specialized functions:

Table 1: Tunable Properties and Subclasses of Ionic Liquids

| Tunable Feature | Impact on Properties | Resulting IL Subclass | Analytical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cation alkyl chain length | Modifies hydrophobicity, viscosity, & solvation power | Pyrrolidinium ILs with varying chains (PYR11, PYR14, PYR18) [15] | Stationary phases, extraction solvents |

| Polymerizable groups | Enhances thermal/chemical stability, enables solid supports | Polymeric ILs (PILs) [11] | Sorbents in SPE, GC stationary phases |

| Chiral centers | Imparts stereoselectivity | Chiral ILs (CILs) [11] | Enantioseparations in chromatography |

| Paramagnetic anions | Introduces magnetic susceptibility | Magnetic ILs (MILs) [11] [14] | Magnetic-assisted extractions |

| Fluorinated anions | Increases hydrophobicity & thermal stability | [BMIM][NTf2], [P66614][NTf2] [12] | HS-GC diluents for residual solvents |

Application Note: ILs as Green Diluents in Residual Solvent Analysis

Principle and Advantages

Static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) is the standard technique for determining residual solvents in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Traditional diluents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) present issues including volatility, degradation at high temperatures, and interference with analysis [13]. ILs serve as superior diluents due to their negligible vapor pressure and high thermal stability, enabling higher incubation temperatures that improve partitioning of volatile analytes into the headspace without solvent interference [12] [13].

Performance Comparison

Studies demonstrate significant improvements when employing ILs as HS-GC diluents compared to conventional solvents:

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of ILs vs. Traditional Diluents in HS-GC

| Diluent | Incubation Temperature | LOD Improvement Factor | Analyte Recovery | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [BMIM][NTf2] [12] | 140°C | 25-fold vs. NMP | Excellent with various APIs | Superior sensitivity, high thermal stability |

| [P66614][NTf2] [12] | 140°C | Significant vs. conventional | Excellent with various APIs | High temperature stability |

| [EMIM][EtSO4] [13] | Optimized per method | Improved sensitivity | >95% for IPA and DCM | Minimal expansion during heating, green credentials |

| Conventional (NMP/DMSO) | Typically <100°C | Baseline | Variable | Established methods, lower cost |

The implementation of IL-based methods addresses green chemistry principles by replacing volatile organic solvents with non-volatile alternatives while simultaneously improving analytical performance [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Residual Solvents in Pharmaceuticals Using IL-Based HS-GC

This validated protocol adapts methodologies from published studies for determining Class 1, 2, and 3 residual solvents in API samples [12] [13].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for IL-Based HS-GC

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid Diluent | [BMIM][NTf2] or [EMIM][EtSO4], high purity (>99%) | Primary diluent; provides non-volatile matrix for headspace analysis |

| Pharmaceutical Standard | Certified reference standards of target solvents (e.g., IPA, DCM) | Quantification and method validation |

| Internal Standard | Suitable deuterated or structural analog solvent | Correction for injection volume variability |

| API Samples | Pharmaceutical compounds under investigation | Target matrix for residual solvent determination |

| Headspace Vials | 20 mL, sealed with PTFE/silicone septa | Containment for sample incubation and headspace sampling |

Instrumentation and Conditions

- Gas Chromatograph: Equipped with flame ionization detector (FID) or mass spectrometer (MS)

- Column: DB-1 or equivalent capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 1.8 μm) [13]

- Headspace Sampler: Automated static headspace system

- HS Conditions: Incubation temperature: 140°C; Incubation time: 15 min; Pressurization time: 1 min; Injection volume: 1 mL [12]

- GC Temperature Program: 40°C (hold 5 min), ramp 20°C/min to 200°C (hold 2 min)

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow 1.5 mL/min

- FID Temperature: 250°C

Sample Preparation Procedure

- IL Preparation: Dry the ionic liquid ([BMIM][NTf2] or equivalent) under vacuum at 80°C for 2 hours to remove residual moisture and volatiles.

- Standard Solutions: Prepare stock solutions of target residual solvents in appropriate concentration ranges (e.g., IPA: 25-375 μg/mL; DCM: 3.5-53 μg/mL) [13].

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 50 ± 1 mg of API sample into a 20 mL headspace vial. Add 5.0 mL of the purified IL diluent. Seal immediately with crimp cap.

- Calibration Standards: Fortify IL with known concentrations of residual solvents to create calibration standards covering the expected concentration range.

Analysis and Quantification

- Load prepared samples into the headspace autosampler.

- Execute the analytical method with parameters specified above.

- Quantify residual solvents using external calibration or internal standard method.

- For method validation, determine linearity, precision, accuracy, LOD, LOQ following ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [13].

Protocol: IL-Assisted Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) for Aqueous Samples

This protocol outlines an environmentally-friendly microextraction technique for preconcentrating analytes from aqueous samples prior to analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- Hydrophobic IL: [C4MIm][PF6] or other water-immiscible IL

- Aqueous sample: Environmental, biological, or pharmaceutical samples

- Disperser solvent: Methanol or acetone (optional for assisted methods)

- Ion-exchange reagent: Ammonium hexafluorophosphate (for effervescence-assisted methods) [11]

Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Adjust pH of aqueous sample if needed for target analytes.

- IL Dispersion: Add 50-100 μL of hydrophobic IL to the sample (typically 5-10 mL volume).

- Dispersion Assistance:

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate the IL phase.

- Analysis: Collect the sedimented IL phase using a microsyringe and inject directly into GC or HPLC systems.

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

HS-GC Analytical Workflow Using IL Diluents

HS-GC Workflow with IL

IL Selection Strategy for Analytical Applications

IL Selection Strategy

Discussion and Outlook

The implementation of ILs as designer solvents in analytical science, particularly for pharmaceutical analysis, represents a significant advancement toward greener methodologies while simultaneously improving analytical performance. The tunable nature of ILs allows researchers to overcome specific methodological constraints that traditional solvents cannot address [11].

The exceptional thermal stability of ILs like [BMIM][NTf2] enables higher headspace incubation temperatures, dramatically improving sensitivity for residual solvent detection [12]. Furthermore, their negligible vapor pressure eliminates solvent interference peaks and reduces environmental impact compared to conventional diluents [13] [14]. The emerging trend toward third-generation ILs derived from natural sources (amino acids, sugars, choline) promises even greener alternatives with reduced toxicity and improved biodegradability [6] [14].

Future directions in IL-based analytical methods include the development of more specialized task-specific ILs, expanded applications in mass spectrometry and spectroscopy, and integration with portable analytical devices for point-of-care testing [11]. As the design principles governing IL structure-property relationships become better understood, the potential for creating customized solvents for specific analytical challenges will continue to grow, solidifying the role of ILs as indispensable tools in the analytical scientist's toolkit.

Ionic liquids (ILs), a class of materials often defined as organic salts with melting points below 100 °C, have transitioned from academic curiosities to potential green solvents in various fields, including analytical chemistry [5] [17]. Their reputation as environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional volatile organic compounds (VOCs) is largely founded on their negligible vapor pressure, which minimizes atmospheric emissions and inhalation risks [1] [18]. The modular nature of ILs, allowing for a multitude of cation-anion combinations, earns them the moniker "designer solvents," as their physicochemical properties can be tailored for specific applications [19] [20].

Within the context of a thesis on green analytical methods for residual pharmaceutical analysis, this document provides a critical evaluation of ILs against the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry. It offers detailed application notes and standardized protocols to assist researchers in making informed decisions about the use of ILs in sustainable laboratory practices. As the field progresses, ILs have evolved through generations, with the latest focusing on sustainability and multifunctionality [20]. This evaluation encompasses their role as solvents for the extraction and analysis of pharmaceutical residues, balancing their significant advantages with an honest assessment of their potential environmental trade-offs.

The Evolutionary Generations of Ionic Liquids

The development of ILs can be categorized into four distinct generations, each with a specific design focus [20] [17]. Understanding this evolution is critical for selecting ILs that align with green chemistry goals.

Table 1: Generations of Ionic Liquids

| Generation | Primary Focus | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | Green Solvents | Low melting point, high thermal stability, low vapor pressure; often sensitive to air/water and poorly biodegradable [17]. | Replacement for volatile organic solvents [20]. |

| Second | Tunable Properties | Air and water stability; adjustable physical and chemical properties for specific tasks [17]. | Catalysis, lubricants, electrochemical systems [20] [17]. |

| Third | Biological Applications | Incorporation of bio-derived or task-specific ions; improved biocompatibility, lower toxicity, and often better biodegradability [20] [17]. | Drug delivery systems, pharmaceutical synthesis, biomedicine [20] [17]. |

| Fourth | Sustainability & Multifunctionality | Focus on biodegradability, sustainability, and smart functionality; biocompatible with unexpected properties in mixtures [20] [17]. | Advanced energy storage, precision medicine, sustainable industrial processes [20]. |

For green analytical chemistry, the shift towards third- and fourth-generation ILs, such as Bio-ILs derived from cholinium or amino acids, is particularly relevant due to their enhanced biocompatibility and reduced environmental footprint [5] [17].

Evaluation of Ionic Liquids Against the 12 Principles

The following section provides a detailed evaluation of ILs against the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, with a specific focus on their application as solvents in analytical methods for pharmaceutical residues.

Principles Where Ionic Liquids Demonstrate Strong Alignment

Principle 5: Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries ILs excel in this area due to their negligible vapor pressure, which eliminates inhalation risks and reduces atmospheric pollution compared to conventional VOCs [1] [18]. Their high thermal stability also enhances operational safety by reducing flammability risks [1].

Principle 6: Design for Energy Efficiency The use of ILs in microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted extraction techniques for analytes demonstrates energy efficiency. These methods, when combined with ILs, often result in faster extraction times and lower overall energy consumption compared to traditional Soxhlet extraction [21].

Principle 9: Use of Catalysis ILs are extensively employed as green catalytic solvents in various chemical syntructions, including pharmaceutical manufacturing. Their unique ionic environment can enhance reaction rates and selectivity, reducing the need for stoichiometric reagents and minimizing waste [17].

Principles with Mixed or Context-Dependent Alignment

Principle 3: Less Hazardous Chemical Synthesis The greenness of an IL's own synthesis is highly variable. While some Bio-ILs are derived from renewable resources like choline, the production of many conventional ILs can involve volatile solvents and energy-intensive processes, offsetting their end-use benefits [1].

Principle 4: Designing Safer Chemicals The toxicity of ILs is not inherent but structurally dependent. Key findings include:

- Cation Effect: Toxicity often increases with the length of the alkyl chain in the cation [19] [1].

- Anion Effect: Anions like [PF₆]⁻ and [BF₄]⁻ can hydrolyze and release toxic species, whereas anions derived from natural products (e.g., amino acids) are generally safer [5].

- Innovative Designs: Third- and fourth-generation ILs, including API-ILs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient ILs) and Bio-ILs, are explicitly designed for reduced toxicity and improved safety profiles [5] [17].

Principle 7: Use of Renewable Feedstocks This is a key differentiator between IL generations. First-generation ILs are typically petroleum-based, while third- and fourth-generation Bio-ILs and natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDES) are derived from biomass-based sources, such as choline, amino acids, and organic acids, aligning with this principle [5] [17].

Principle 10: Design for Degradation The biodegradability of ILs is a significant concern. Many early ILs, particularly those with quaternary ammonium cations and halogenated anions, demonstrate poor biodegradability and can persist in the environment [19] [22]. However, newer ILs designed with ester groups or readily metabolizable fragments in their structure show significantly improved biodegradation profiles [5].

Principles Presenting Significant Challenges

Principle 12: Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention A major environmental concern is the persistence and potential ecotoxicity of some ILs. Studies show that certain ILs, especially hydrophobic ones, can strongly bind to sediments and exhibit toxicity to aquatic organisms and plants [19] [22] [1]. Their high water solubility and stability can lead to persistence in the environment if released [18]. Therefore, they cannot be universally classified as inherently safer without a case-specific assessment.

Table 2: Comprehensive Evaluation of Ionic Liquids Against the 12 Principles

| Principle | Alignment | Key Findings & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Waste Prevention | Medium | Potential for recycling and reuse in catalytic systems; but synthesis waste must be considered. |

| 2. Atom Economy | Low-Medium | Applies to synthesis of ILs themselves; often involves multi-step synthesis with poor atom economy. |

| 3. Less Hazardous Synthesis | Variable | Synthesis of some Bio-ILs is green; many conventional ILs require hazardous reagents and energy. |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Variable | Toxicity is tunable: Alkyl chain length and anion choice are critical. Bio-ILs and API-ILs are safer by design. |

| 5. Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | High | Negligible vapor pressure, non-flammable, reduce VOC emissions and inhalation hazards. |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | High | Excellent performance in microwave- and ultrasound-assisted extraction methods. |

| 7. Renewable Feedstocks | Variable | 1st/2nd Gen: Often petroleum-based. 3rd/4th Gen: Use choline, amino acids, and other renewables. |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Medium | Can simplify synthesis pathways, but not a primary advantage in analytics. |

| 9. Catalysis | High | Widely used as green catalytic solvents and organocatalysts, enhancing efficiency. |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Variable | Many ILs are persistent environmental pollutants [22]. Newer ILs with ester groups show improved biodegradability [5]. |

| 11. Real-time Analysis | Low | Not a inherent property of ILs, though they can be used in sensing platforms. |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry | Low-Medium | Persistence and ecotoxicity are key concerns [19] [18]. Not automatically "inherently safer"; requires lifecycle assessment. |

Application Note: IL-Based Extraction of Pharmaceutical Residues

Background and Objective

Residual pharmaceuticals in environmental samples are often present at trace levels within complex matrices. This application note details a green analytical method using a bio-derived IL for the efficient extraction of common pharmaceutical residues (e.g., antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) from water samples prior to chromatographic analysis. The method aims to replace traditional solvents like dichloromethane.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for IL-Based Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Green Chemistry Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Choline Geranate IL (CAGE) | Primary extraction solvent. A bio-IL formed from choline (a vitamin) and geranic acid [23]. | High biocompatibility, low toxicity, and derived from renewable feedstocks. |

| Amino Acid-Based ILs (e.g., Choline Alaninate) | Alternative extraction solvent for polar pharmaceuticals. | Biodegradable components and low ecotoxicity. |

| Model Pharmaceutical Mixture | Analytical standards of target analytes (e.g., sulfamethoxazole, diclofenac, carbamazepine). | Enables method development and validation. |

| Ultrapure Water | Matrix for calibration standards and sample reconstitution. | The greenest solvent available. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For sample clean-up and pre-concentration if required. | Reduces solvent consumption compared to liquid-liquid extraction. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Ultrasound-Assisted IL-Based Extraction of Pharmaceuticals from Water

Safety Notes: Standard personal protective equipment (PPE) including lab coat, gloves, and safety glasses must be worn.

Step 1: Preparation of IL Stock Solution

- Weigh 100 mg of choline geranate (CAGE) IL into a 10 mL volumetric flask.

- Dilute to the mark with ultrapure water and vortex vigorously for 2 minutes to create a homogeneous 10 mg/mL aqueous stock solution. This solution is stable for one week when refrigerated at 4°C.

Step 2: Sample Preparation and Extraction

- Collect water samples (e.g., effluent from wastewater treatment plants) in amber glass bottles.

- Filter samples through a 0.45 μm glass fiber filter to remove particulate matter.

- Pipette 50 mL of the filtered water sample into a 100 mL conical centrifuge tube.

- Add 500 μL of the 10 mg/mL CAGE stock solution to the sample tube.

- Cap the tube and place it in an ultrasonic water bath.

- Sonicate the mixture for 15 minutes at 40°C, ensuring the sample is fully submerged.

Step 3: Phase Separation and Recovery

- After sonication, centrifuge the sample tube at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to facilitate complete phase separation.

- Carefully collect the lower IL-rich phase containing the extracted analytes using a glass syringe with a long needle.

- Transfer the extracted phase to a 2 mL HPLC vial.

Step 4: Analysis

- The extract is now ready for direct analysis via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a mass spectrometer (MS) or a diode-array detector (DAD).

- Chromatographic Conditions (Example):

- Column: C18 reversed-phase (150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: (A) Water with 0.1% formic acid, (B) Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 20 minutes

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Detection: MS/MS in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode for optimal sensitivity and selectivity.

The evaluation of ionic liquids against the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry reveals a nuanced picture. ILs are not a monolithic "green" solution but a highly diverse class of materials whose environmental profile is entirely dependent on their specific design. They show outstanding performance in principles related to safer solvents (Principle 5) and energy efficiency (Principle 6). However, their alignment with principles concerning degradation (Principle 10) and inherent safety (Principle 12) is a major challenge for many early-generation ILs.

The future of ILs in green analytical chemistry lies in the rational design and adoption of third- and fourth-generation ILs, such as Bio-ILs and API-ILs, which prioritize biodegradability and low toxicity from the outset [23] [20] [5]. The integration of lifecycle assessment (LCA) is critical for a holistic judgment of their sustainability [21]. Furthermore, emerging innovations like AI-driven design of ILs and the development of smart, recyclable IL-based materials promise to further enhance their green credentials [23] [20]. For researchers analyzing pharmaceutical residues, the selective use of tailored, benign ILs offers a powerful pathway to develop more sustainable and effective analytical methods.

Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as a cornerstone of green analytical chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector for the analysis of residual solvents. Their celebrated negligible vapor pressure reduces the risk of atmospheric emissions and occupational exposure, presenting a significant advantage over traditional volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [13] [24]. This property has fueled their adoption as advanced diluents in static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC), where their thermal stability allows for higher incubation temperatures, leading to superior sensitivity and throughput in the quantification of residual solvents like isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and dichloromethane (DCM) in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [13] [12].

However, the "green" credential of an IL cannot be established on low volatility alone. The environmental footprint of these compounds is a function of their entire lifecycle, with aquatic toxicity and ready biodegradability being critical parameters [25] [26]. Early-generation ILs, while excellent in performance, often exhibited significant toxicity and poor biodegradability, creating a paradox where "green" solvents posed potential environmental hazards [25] [27]. This application note critically examines the duality of ILs—their analytical benefits versus their ecological impacts—framed within pharmaceutical residual solvent analysis. It provides structured data, validated protocols, and a framework for selecting sustainable, task-specific ILs that align with the principles of green chemistry.

Quantitative Data on IL Toxicity and Biodegradability

The environmental and toxicological profile of an IL is predominantly determined by the chemical structure of its constituent cation and anion. Understanding these structure-activity relationships (SARs) is essential for the rational design of benign solvents.

Table 1: Ecotoxicity Data of Common Ionic Liquid Cations against Various Test Organisms

| Ionic Liquid Cation | Test Organism | Endpoint | Value (EC50 or LC50) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Methyl-3-octylimidazolium[C8MIM]+ | Freshwater Algae(Selenastrum capricornutum) | 72h EC50 | 0.056 mg/L | High toxicity, increasing with alkyl chain length [25] |

| 1-Methyl-3-hexylimidazolium[C6MIM]+ | Freshwater Algae(Selenastrum capricornutum) | 72h EC50 | 0.25 mg/L | Toxicity increases with alkyl chain length [25] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium[BMIM]+ | Marine Algae(Oocystis submarina) | 96h EC50 | 6.66 mg/L | Demonstrates toxicity in marine environment [25] |

| 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium[BMIM]+ | Frog Embryo(Rana nigromaculata) | 96h LC50 | 1.32 mg/L | Shows developmental toxicity [25] |

| N-butylpyridinium[BPYR]+ | Rat (F-344) / Mouse (B6C3F1) | In vivo LD50 / Toxicokinetics | Transported by organic cation transporter 2 [25] | Mechanism of mammalian toxicity identified [25] |

Table 2: Biodegradability and Biocompatibility of Ionic Liquid Classes

| Ionic Liquid Type | Example | Biodegradability | Toxicity Profile | Key Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation ILs | [BMIM][PF6], [BMIM][BF4] | Low to Non-biodegradable [27] | Moderate to High (e.g., cytotoxic) [25] [27] | Air/moisture sensitive; limited "green" value [27] |

| Second-Generation ILs | Task-specific ILs | Varies with design | Tunable, but can be high | Air/water stable; focus on physicochemical tuning [27] |

| Third-Generation (Bio-ILs) | Choline-amino acid ILs(e.g., Choline-Geranate) | Readily Biodegradable [27] | Low cytotoxicity, high biocompatibility [23] [27] | Derived from natural, renewable sources; GRAS status components [27] |

| Phosphonium-based ILs | [P66614][NTf2] | Often Low | Can be highly toxic | Used in specific applications despite toxicity profile [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HS-GC Analysis of Residual Solvents Using an IL Diluent

This protocol describes a validated method for quantifying Class 2 and 3 residual solvents in APIs using [BMIM][NTf2] as a green diluent, offering enhanced sensitivity over traditional solvents like N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) [12] [24].

1. Principle: The API is dissolved in the IL diluent. In a sealed headspace vial, volatile residual solvents partition between the non-volatile IL phase and the headspace gas at an elevated temperature. The headspace vapor is then injected into a GC-FID for separation and quantification [13] [24].

2. Materials:

- Ionic Liquid Diluent: 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis[(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl]imide ([BMIM][NTf2]), high purity grade.

- API: The drug substance to be analyzed.

- Standards: Certified reference standards of target residual solvents (e.g., IPA, DCM, methanol, acetonitrile).

- Equipment: Static Headspace Autosampler, Gas Chromatograph equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID), and a DB-1 (or equivalent) capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 1.8 µm) [13] [12].

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 100 mg of the API into a headspace vial. Add 1.0 mL of [BMIM][NTf2] diluent. Seal the vial immediately with a crimp cap and PTFE/silicone septum. 2. Calibration Standards: Prepare a series of calibration standards in [BMIM][NTf2] covering the concentration range of interest (e.g., 25-375 µg/mL for IPA). Use the same API matrix if possible to account for any matrix effects [13]. 3. Headspace Incubation: Load the vials into the autosampler and incubate at 140°C for 15 minutes with constant agitation to achieve equilibrium partitioning [24]. 4. GC-FID Analysis: * Injection: Inject a defined volume (e.g., 1 mL) of the headspace gas from each vial. * Carrier Gas: Helium or Nitrogen at a constant linear velocity. * Oven Program: Use a temperature ramp suitable for resolving all target solvents. Example: 40°C (hold 5 min), ramp at 20°C/min to 200°C (hold 2 min). * Detector Temperature: 250°C [13] [24]. 5. Quantification: Identify solvents based on retention time and quantify by comparing peak areas against the calibrated standard curve.

4. Key Advantages:

- Enhanced Sensitivity: The low volatility and high thermal stability of the IL allow for higher incubation temperatures, leading to a 25-fold improvement in the limit of detection (LOD) for some solvents compared to NMP [24].

- Reduced Interference: Negligible diluent vapor pressure minimizes background chromatographic noise [12].

- Robustness: The method is validated for repeatability, accuracy, and linearity per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [13].

Protocol 2: Assessing the Biodegradability of Ionic Liquids

Evaluating biodegradability is crucial for determining the environmental persistence of ILs. The Closed Bottle Test (OECD 301D) is a standard method for this purpose.

1. Principle: The IL is incubated in a dilute aqueous solution containing a defined population of microorganisms. Biodegradation is measured by the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) over 28 days, compared to the theoretical chemical oxygen demand (ThOD). A substance is considered "readily biodegradable" if it achieves >60% biodegradation within 10 days of the degradation curve reaching 10% [26].

2. Materials:

- Test Substance: High-purity ionic liquid.

- Inoculum: Activated sewage sludge from a treatment plant receiving domestic sewage.

- Mineral Medium: Contains essential inorganic nutrients (N, P, K, etc.).

- Equipment: BOD bottles, air-tight seals, BOD measuring system (e.g., respirometer), controlled-temperature incubator at 20°C ± 1 [26].

3. Procedure: 1. Preparation: Dissolve the IL in mineral medium to achieve a concentration of 10-20 mg/L as carbon. Add a small, standardized volume of inoculum. 2. Setup: Fill BOD bottles with the test solution, seal to exclude air, and incubate in the dark at 20°C. Include control bottles with a reference compound (sodium acetate) and without the test substance (blank). 3. Monitoring: Measure the oxygen consumption in the test and control bottles over a 28-day period. 4. Calculation: * Calculate the cumulative oxygen consumption (BOD) for the test substance, correcting for the blank. * Determine the percentage biodegradation as: (BOD / ThOD) × 100.

4. Interpretation: ILs with alkyl chains (e.g., in imidazolium cations) often show poor biodegradability. In contrast, ILs derived from natural precursors, such as choline-based cations and fatty acid anions, consistently demonstrate ready biodegradability, making them superior choices for sustainable method development [27] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for IL-Based Analytical and Environmental Assessment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Green Chemistry Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| [EMIM][EtSO4] (1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate) | Green diluent for HS-GC analysis of residual solvents in pharmaceuticals [13]. | Offers improved peak resolution and minimal expansion during heating, reducing vial leakage risk [13]. |

| Choline Geranate (CAGE) | Biocompatible IL for transdermal drug delivery and formulation; a model third-generation Bio-IL [23] [27]. | Composed of GRAS components; shows excellent biocompatibility and has entered clinical trials for topical applications [23]. |

| [BMIM][NTf2] (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide) | High-performance, thermally stable diluent for sensitive HS-GC methods [12] [24]. | High performance but scrutinized: While non-volatile, its toxicity and poor biodegradability require careful environmental risk assessment [25] [24]. |

| Choline Chloride | Precursor cation for synthesizing a wide range of biodegradable, low-toxicity Bio-ILs [27]. | Derived from an essential nutrient; listed as "generally regarded as safe" (GRAS) by the FDA, forming the basis of sustainable IL design [27]. |

| Activated Sewage Sludge | Inoculum for OECD-standard biodegradability tests (e.g., OECD 301D) [26]. | Provides a realistic microbial community to assess the environmental persistence of ILs under standardized conditions [26]. |

Workflow for Sustainable IL Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical decision pathway for selecting an appropriate ionic liquid for pharmaceutical analysis that balances analytical performance with environmental responsibility.

IL Selection Workflow: A logical pathway for selecting ionic liquids that meet both analytical and environmental criteria.

The journey of ionic liquids from laboratory curiosities to green analytical tools is maturing beyond the singular metric of negligible vapor pressure. A truly green assessment demands a holistic view that includes toxicity, biodegradability, and the full lifecycle impact [25] [28] [1]. While first- and second-generation ILs like [BMIM][NTf2] provide unparalleled analytical performance, their potential environmental persistence is a significant drawback [24].

The future of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis lies in the strategic adoption of third-generation, biocompatible ILs (Bio-ILs). Derived from natural, renewable sources like choline and amino acids, these solvents offer a compelling combination of low toxicity, ready biodegradability, and tunable physicochemical properties [27]. By employing the structured data, protocols, and selection framework outlined in this note, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed decisions. This approach ensures that the pursuit of analytical excellence goes hand-in-hand with the fundamental principles of environmental stewardship, ultimately leading to greener and more sustainable pharmaceutical practices.

Ionic liquids (ILs) have emerged as transformative solvents in green analytical chemistry, particularly for the analysis of pharmaceutical compounds and residual solvents. Their unique molecular architecture, composed of bulky, asymmetric organic cations and organic or inorganic anions, results in a set of designable properties, including negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, and tunable solvation behavior [6] [29]. This tunability allows for the precise control of molecular interactions—such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, and π-π stacking—which govern how ILs solvate and bind pharmaceutical analytes. This application note delineates the core molecular interactions involved, provides a validated protocol for residual solvent analysis, and outlines essential tools for implementing IL-based analytical methods, thereby supporting the advancement of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis.

Molecular Interaction Mechanisms

The solvation power and binding efficacy of ILs towards pharmaceutical analytes stem from a complex interplay of multiple non-covalent interactions. The table below summarizes the key molecular interactions and their roles in pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 1: Key Molecular Interactions Between Ionic Liquids and Pharmaceutical Analytes

| Interaction Type | Molecular Basis | Impact on Pharmaceutical Analytes | Common IL Components Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic/Electrostatic | Coulombic forces between charged ions of the IL and ionizable groups on the analyte [23]. | Improves solubility of ionic drugs; enables formation of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient-ILs (API-ILs) [23] [5]. | Imidazolium, pyridinium, ammonium cations; [PF₆]⁻, [BF₄]⁻ anions [6]. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Donation and acceptance of protons between IL ions and analyte functional groups (e.g., -OH, -NH) [23]. | Disrupts analyte crystal lattice, enhancing dissolution; stabilizes protein-based biologics [23] [30]. | Protic ILs (PILs); anions like [CH₃COO]⁻; cations with hydroxyl groups (e.g., choline) [23] [31]. |

| Van der Waals & Hydrophobic | Weak dipole-dipole and induced dipole interactions; strengthened by long alkyl chains on IL cations [23]. | Enhances solubility of non-polar analytes; facilitates incorporation into lipid-based nanocarriers [23] [30]. | ILs with long alkyl chains (e.g., C₈, C₁₀); Surface-Active ILs (SAILs) [5]. |

| π-π / n-π Stacking | Interactions between aromatic systems in the IL (e.g., imidazolium ring) and aromatic moieties in the analyte [23]. | Aids in solvating planar, aromatic drug molecules; can influence spectroscopic analysis [23] [29]. | Imidazolium, pyridinium cations [6]. |

The solvation properties of ILs, quantified by Kamlet-Aboud-Taft parameters, are highly tunable [31]. For instance, a key structure-property relationship indicates that increasing the alkyl chain length on a PIL cation leads to an increase in its hydrogen-bond accepting basicity (β), which can enhance interactions with hydrogen-donating analytes [31]. Furthermore, the presence of hydroxyl groups on the PIL cation increases its hydrogen-bond donating acidity (α) and dipolarity/polarizability (π*), making the IL more effective at solvating polar compounds [31].

Experimental Protocol: Analysis of Residual Solvents Using an IL-Based Static Headspace-GC-FID Method

This protocol details a green analytical method for quantifying residual Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) and Dichloromethane (DCM) in pharmaceutical tablets using the IL [EMIM][EtSO₄] as a diluent, adapted from a published study [13].

Principle

The method leverages the low volatility and high thermal stability of [EMIM][EtSO₄] to efficiently partition volatile residual solvents from the sample matrix into the headspace for analysis by Gas Chromatography with a Flame Ionization Detector (GC-FID). The IL minimizes the environmental and operational hazards associated with conventional solvents [13].

Reagents and Equipment

- Ionic Liquid: 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate ([EMIM][EtSO₄])

- Pharmaceutical Samples: Hydrochlorothiazide and Losartan Potassium tablets

- Standards: Certified reference standards of IPA and DCM

- GC System: Gas Chromatograph equipped with Flame Ionization Detector (FID) and a DB-1 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 1.8 µm)

- Headspace Autosampler

- Analytical Balance

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh and finely powder the pharmaceutical tablets.

- Weigh approximately 100 mg of the powdered sample into a headspace vial.

- Add 1.0 mL of [EMIM][EtSO₄] to the vial, ensuring the powder is fully dispersed in the IL.

- Seal the vial immediately with a crimp cap.

Headspace Generation:

- Place the prepared vials in the headspace autosampler.

- Condition the vials at a defined temperature (e.g., 80°C) for a set time (e.g., 15 minutes) to allow for equilibrium of the volatile solvents between the IL phase and the headspace.

GC-FID Analysis:

- Inject a defined volume of the headspace gas (e.g., 1 mL) into the GC system in split mode.

- Oven Program: Initial temperature 40°C (hold 5 min), ramp to 120°C at 20°C/min, final hold 2 min.

- Carrier Gas: Helium or Nitrogen, constant flow.

- FID Temperature: 250°C.

Calibration:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of IPA and DCM in [EMIM][EtSO₄] across the concentration ranges of 24.96–374.43 µg mL⁻¹ and 3.53–52.92 µg mL⁻¹, respectively [13].

- Analyze the standard solutions following the same headspace and GC-FID conditions as the samples.

- Construct calibration curves by plotting the peak area against the concentration for each analyte.

Key Advantages of the IL-Based Method

- Green Alternative: Replaces volatile organic solvents as a diluent, aligning with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles [21].

- Improved Performance: The IL provides enhanced peak resolution, reduced sample consumption, and minimizes the risk of vial leakage due to its low volumetric expansion during heating [13].

- Sensitivity and Reproducibility: The method has been validated per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, demonstrating high sensitivity, linearity, and reproducibility [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of IL-based analytical methods requires specific reagents and an understanding of their function.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IL-Based Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Dilution Solvent | Serves as a non-volatile, thermally stable medium for sample preparation in headspace GC, improving the partitioning of volatile analytes into the headspace [13]. | [EMIM][EtSO₄] |

| Hydrogen-Bond Modulator | Tunes the H-bond acidity (α) and basicity (β) of the IL to optimize solvation for specific analyte classes, such as polar or hydrogen-bonding compounds [31]. | Hydroxyl-functionalized cations (e.g., Choline), Carboxylate anions (e.g., [CH₃COO]⁻) |

| Extraction Solvent | Used in microextraction techniques for pre-concentrating analytes from complex matrices, leveraging IL tunability for high selectivity and recovery [32] [9]. | Imidazolium-based ILs (e.g., [C₄C₁im][PF₆]) |

| Analytical Column | Provides the stationary phase for chromatographic separation of the volatile analytes in the gas phase. | DB-1 capillary column (non-polar) |

| Solvatochromic Dyes | Probe molecules used to experimentally characterize the solvation properties (polarity, H-bonding ability) of newly synthesized or selected ILs [31]. | Reichardt's Dye 33, 4-Nitroaniline, N,N-Diethyl-4-nitroaniline |

Workflow and Structure-Property Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying an ionic liquid in a green analytical method, from design to analysis, based on understanding its molecular interactions.

Diagram 1: Workflow for IL-based analytical method development, highlighting key structure-property relationships that guide IL selection. The path from defining the analytical goal to final analysis involves strategic ion selection, experimental characterization of the IL's solvation properties, and protocol execution. Critical molecular design rules, such as the effect of alkyl chain length and hydroxyl groups on hydrogen-bonding parameters, directly inform the selection and characterization steps.

Implementing IL-Based Methods: From Headspace GC to Advanced Microextraction

Within pharmaceutical quality control, the precise determination of residual solvents and genotoxic impurities in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and finished drug products is a critical safety requirement. These volatile organic compounds, classified by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, must be monitored at trace levels, often posing significant analytical challenges. Traditional headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) methods employing conventional organic diluents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) are limited by the volatile nature of these solvents themselves, which restricts practical incubation temperatures and thereby limits sensitivity for high-boiling point analytes.

Ionic liquids (ILs), characterized by their negligible vapor pressure, exceptional thermal stability, and tunable physicochemical properties, present a transformative alternative as green diluents in HS-GC. Their application significantly enhances method sensitivity, reduces environmental impact compared to traditional volatile organic solvents, and expands the analytical scope to include a wider range of impurities. This application note details the use of ILs as superior diluents for residual solvent analysis, framed within the broader context of advancing green analytical methods in pharmaceutical research and development.

The Principle: Why Ionic Liquids Excel in HS-GC

Ionic liquids are organic salts that exist as liquids below 100°C. Their unique properties stem from their ionic composition and bulky, asymmetric cations, which prevent efficient packing and crystallization. The combination of these properties makes them nearly ideal for HS-GC applications [33]:

- Negligible Vapor Pressure: This is the most critical advantage. ILs do not significantly volatilize at standard HS-GC incubation temperatures (e.g., 100–150°C), eliminating solvent peak interference and allowing the use of highly sensitive detectors like the Electron Capture Detector (ECD) or Flame Ionization Detector (FID) without signal masking. It also enables the use of much higher incubation temperatures than with traditional diluents [34] [33].

- High Thermal Stability: Many ILs are stable at temperatures exceeding 200°C, allowing for high-temperature headspace incubation that efficiently partitions medium- and high-boiling analytes into the gas phase. This directly translates to lower detection limits for these challenging compounds [33] [35].

- High Solubilizing Power: ILs can dissolve a wide range of materials, including various APIs and complex matrices like cellulose-based pharmaceutical formulations. This often eliminates the need for extensive sample pre-treatment, such as extraction, simplifying the analytical workflow and reducing potential analyte loss [33].

- Tunable Nature: By selecting different cation-anion pairings, the properties of an IL (e.g., hydrophilicity, polarity, and hydrogen-bonding capacity) can be fine-tuned to optimize the extraction and chromatographic behavior for specific analytes and sample matrices [33].

The following workflow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the general procedure for analyzing residual solvents in a pharmaceutical solid dosage form using an IL diluent.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for HS-GC Analysis Using an IL Diluent

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The transition from traditional diluents to ILs provides quantitatively superior analytical performance. The following tables summarize key metrics from validated methods, demonstrating the enhanced sensitivity, broader linearity, and improved analyte recovery achievable with IL-based methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Performance of ILs vs. Traditional Diluents in HS-GC

| Analytical Parameter | Traditional Diluents (e.g., DMSO, NMP) | Ionic Liquid Diluents (e.g., [BMIM][NTf₂]) | Key Findings and Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Varies; higher for high-boiling analytes | 5–500 ppb for GTIs [34]; 5.8–20 ppm for residual solvents [35] | Up to 25-fold improvement in LOD for residual solvents reported [35]; tens of thousands-fold improvement for some GTIs [34]. |

| Linear Range | Limited, especially for trace analysis | Up to five orders of magnitude for GTIs [34]; up to two orders of magnitude for Class 3 solvents [35] | Exceptional dynamic range reduces need for sample re-analysis and dilution. |

| Optimal Incubation Temperature | Limited by solvent volatility (often <100°C) | Can be elevated to 140°C [35] or higher | Higher temperature improves partitioning of high-boiling analytes into the headspace, directly boosting sensitivity. |

| Analyte Recovery | Good for low-boiling analytes | Excellent recovery demonstrated across multiple APIs for both residual solvents and GTIs [34] [35] | Robust method performance unaffected by complex API matrices. |

| Green Chemistry Profile | Poor (volatile, often hazardous) | Superior (non-volatile, reduced waste, safer operation) [13] [33] | Aligns with principles of Green Analytical Chemistry. |

Table 2: Summary of Validated IL-Based HS-GC Methods for Specific Applications

| Application / Analytic | Ionic Liquid Used | Detection | Validated Method Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotoxic Impurities (Alkyl/aryl halides, Nitro-aromatics) | Various ILs screened | GC-ECD | LOD: 5–500 ppb; Linear Range: Up to 5 orders of magnitude; Excellent recovery validated on two APIs. | [34] |

| Residual Solvents (Isopropyl alcohol, Dichloromethane) | [EMIM][EtSO₄] | GC-FID | Linear range: 24.96–374.43 μg/mL (IPA) & 3.53–52.92 μg/mL (DCM); High reproducibility and minimal vial leakage. | [13] |

| Class 3 Residual Solvents in APIs | [BMIM][NTf₂] | GC-FID | LODs: 5.8–20 ppm; Linear Range: Up to 2 orders of magnitude; Excellent repeatability and analyte recovery. | [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Trace Genotoxic Impurities

This protocol is adapted from a study analyzing alkyl/aryl halides and nitro-aromatic GTIs in small molecule drug substances [34].

4.1.1 Materials and Reagents

- Ionic Liquid Diluent: Select an appropriate IL (e.g., 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, [BMIM][NTf₂]) based on analyte solubility and compatibility. Ensure it is of high purity.

- Standard Solutions: Prepare certified reference standards of target GTIs in a suitable solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) at high concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL) for spiking.

- Drug Substance: The API under investigation.

- Headspace Vials: 20 mL clear glass vials with PTFE/silicone septa and crimp caps.

4.1.2 Instrumentation and Conditions

- GC System: Configured with Electron Capture Detector (ECD).

- Column: Standard non-polar or mid-polarity capillary GC column (e.g., DB-5, 30 m × 0.32 mm × 1.0 μm).

- Headspace Autosampler: Capable of high-temperature incubation.

- Example Method Parameters:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 50–100 mg of drug substance into a headspace vial. Add 1.0 mL of the selected IL diluent and spike with an appropriate volume of GTI standard solution. Seal immediately.

- Headspace Conditions:

- Incubation Temperature: 100–130°C

- Incubation Time: 15–30 minutes

- Loop Temperature: 150–170°C

- Transfer Line Temperature: 170°C

- Injection Volume: 1 mL (from headspace loop)

- GC-ECD Conditions:

- Injector Temperature: 200°C

- Detector Temperature: 300°C

- Oven Program: Ramp from 50°C (hold 2 min) to 280°C at 15°C/min.

- Carrier Gas: Helium or Nitrogen, constant flow 1.5 mL/min.

4.1.3 Method Validation Validate the method as per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, including:

- Specificity: No interference from the API or diluent at the retention times of the GTIs.

- Linearity and Range: Prepare a minimum of five concentration levels. A typical range can be from the LOQ to 120% of the specification limit.

- Accuracy (Recovery): Perform by spiking the API at three concentration levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150% of the specification level) in triplicate. Report percent recovery.

- Precision (Repeatability): Analyze six independently prepared samples at 100% of the specification level. %RSD of the peak areas should be ≤15%.

Protocol 2: Analysis of Residual Solvents in a Tablet Formulation

This protocol is based on a study analyzing Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) and Dichloromethane (DCM) in pharmaceutical tablets using [EMIM][EtSO₄] [13].

4.2.1 Materials and Reagents

- Ionic Liquid Diluent: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate ([EMIM][EtSO₄]).

- Standard Solutions: Prepare individual or mixed stock solutions of target residual solvents (IPA, DCM) in [EMIM][EtSO₄] or water.

- Tablet Formulation: The drug product to be analyzed.

4.2.2 Instrumentation and Conditions

- GC System: Configured with Flame Ionization Detector (FID).

- Column: DB-1 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 1.8 μm) or equivalent.

- Headspace Autosampler.

- Example Method Parameters:

- Sample Preparation: Grind a representative number of tablets to a homogeneous powder. Accurately weigh a portion (e.g., 100–500 mg) into a headspace vial. Add 2.0–5.0 mL of [EMIM][EtSO₄], vortex to dissolve/disperse, and seal.

- Headspace Conditions:

- Incubation Temperature: 90–110°C

- Incubation Time: 20–30 minutes

- Loop/Transfer Line Temperature: 120–140°C

- GC-FID Conditions:

- Injector Temperature: 180°C

- Detector Temperature: 250°C

- Oven Program: Hold at 40°C for 5 min, ramp to 150°C at 20°C/min, hold for 2 min.

- Carrier Gas: Helium or Nitrogen, constant flow.

4.2.3 Method Validation Validate per ICH Q2(R1). The method should demonstrate linearity over the specified range (e.g., 24.96–374.43 μg/mL for IPA), accuracy with recoveries close to 100%, and precision with %RSD < 5% for retention times and <10% for peak areas [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for IL-Based HS-GC Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid Diluents | Solubilizing the sample matrix without interfering with volatile analyte detection. | [BMIM][NTf₂] (for high-temperature methods, GTIs) [34] [35]; [EMIM][EtSO₄] (a "green" solvent for residual solvents) [13] |

| GC Capillary Columns | Separation of volatile analytes after headspace injection. | DB-1, DB-5 (standard stationary phases); Ionic Liquid-based Columns (e.g., Watercol for water analysis) [36] [37] |

| Headspace Vials/Closures | Contain the sample during incubation and allow for reproducible vapor sampling. | 20 mL clear glass vials with PTFE/silicone septa and aluminum crimp caps (must be certified for high-temperature use) |

| Certified Reference Standards | Method development, calibration, and quantification. | Neat materials or certified solutions of target residual solvents (e.g., IPA, DCM) and genotoxic impurities (e.g., alkyl halides, epoxides). |

| High-Purity Gases | Function as GC carrier gas, detector gas, and purge gas. | Helium or Nitrogen (≥99.999% purity) for carrier gas; Hydrogen, Zero Air, and Nitrogen for FID detector. |

The adoption of ionic liquids as diluents in HS-GC represents a significant advancement in pharmaceutical analysis. The experimental data and protocols presented herein confirm that ILs overcome the fundamental limitations of traditional organic solvents, enabling more sensitive, robust, and wider-ranging analytical methods for monitoring volatile impurities.

The practical benefits are substantial:

- Enhanced Sensitivity: The ability to use high incubation temperatures dramatically lowers detection limits for high-boiling analytes, which is critical for meeting stringent regulatory requirements for genotoxic impurities [34].

- Method Ruggedness: The non-volatile nature of ILs minimizes issues like vial over-pressurization and septum failure, leading to more robust and transferable methods suitable for quality control (QC) environments [34] [33].

- Green Analytical Chemistry: ILs align with the principles of green chemistry by reducing the use and emission of volatile organic solvents. Their non-volatility also improves workplace safety for analysts [13] [38].

In conclusion, leveraging ionic liquids in HS-GC provides a powerful, green analytical strategy for residual solvent and genotoxic impurity analysis. Their superior physicochemical properties directly translate into enhanced analytical performance, making them a superior choice for modern pharmaceutical development and quality control. Future work in this field will continue to explore novel IL structures tailored for specific analyte classes and matrices, further solidifying their role in the analytical chemist's toolkit.

The determination of residual pharmaceuticals and impurities is a critical aspect of drug safety and quality control. Traditional extraction methods often require large volumes of hazardous organic solvents, generating significant waste and posing environmental and operational hazards [10]. In alignment with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) techniques have emerged as sustainable alternatives that minimize solvent consumption while maintaining high analytical performance [39] [40].

Ionic liquids (ILs) have revolutionized green sample preparation as advanced solvents with exceptional properties. These organic salts, consisting of asymmetric cations and anions, remain liquid at room temperature and possess negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, and tunable physicochemical characteristics [41] [5]. Their versatility allows for customization of hydrophobicity, viscosity, and selectivity simply by altering cation-anion combinations, making them ideal for pharmaceutical residue analysis [42] [43]. The application of ILs in dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (DLLME) and single-drop microextraction (SDME) has demonstrated significant improvements in extraction efficiency, sensitivity, and environmental sustainability for monitoring pharmaceutical compounds in complex matrices [41] [40].

Theoretical Foundations of IL-Based Microextraction

Ionic Liquids: Structure and Properties

Ionic liquids belong to a class of non-molecular solvents with melting points below 100°C, often liquid at room temperature. Their structure typically features an organic cation (e.g., imidazolium, pyridinium, phosphonium, ammonium) coupled with an organic or inorganic anion (e.g., hexafluorophosphate, tetrafluoroborate, alkyl sulfate) [5]. The extensive combinatorial possibilities of cations and anions enable the design of ILs with specific properties tailored to particular extraction needs, earning them the designation "designer solvents" [5].

Key properties making ILs advantageous for LPME include:

- Negligible vapor pressure: Eliminates evaporation losses and reduces environmental exposure [42]

- High thermal stability: Enables compatibility with various analytical techniques including HPLC and GC [42]

- Tunable viscosity and density: Can be optimized for efficient phase separation [41]

- Dual nature: Possess both hydrophilic and lipophilic characteristics that enhance extraction of diverse analytes [5]

- Multiple interaction capabilities: Provide hydrogen bonding, π-π, ion-dipole, and electrostatic interactions for improved selectivity [42]

Microextraction Principles with Ionic Liquids

In pharmaceutical analysis, microextraction techniques utilizing ILs operate on principles of mass transfer from an aqueous sample (donor phase) to a small volume of IL (acceptor phase). The high surface area between phases and the multiple interaction capabilities of ILs facilitate efficient transfer and preconcentration of target analytes [42] [40]. The selectivity can be fine-tuned by selecting ILs with specific functional groups that interact preferentially with particular pharmaceutical compounds through hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, or ion exchange [5].

The exceptional solvation properties of ILs and their ability to form hydrogen bonds with analytes significantly enhance extraction efficiency compared to conventional organic solvents [41]. Furthermore, their ionic nature enables unique applications such as in-situ metathesis reactions, where the solubility of the IL can be altered during the extraction process to improve phase separation [40].

Techniques and Methodologies

Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) with ILs

DLLME utilizing ionic liquids (IL-DLLME) represents a major advancement in sample preparation technology. This technique employs a ternary component system consisting of an aqueous sample, IL extractant, and disperser solvent [41] [43]. The disperser solvent (typically acetone, methanol, or acetonitrile) miscible with both the sample and IL facilitates the formation of a cloudy solution with fine IL droplets, creating an extensive surface area for rapid analyte extraction [43].

Optimized IL-DLLME Protocol for Pharmaceutical Compounds [41] [43]:

Sample Preparation: Adjust pH and salt content of aqueous pharmaceutical sample to optimize analyte solubility and extraction efficiency.

IL and Disperser Selection:

- Select appropriate IL based on target pharmaceutical compounds' physicochemical properties

- Choose disperser solvent miscible with both aqueous phase and IL

Extraction Procedure:

- Inject appropriate mixture of IL and disperser solvent into sample solution

- Form cloudy solution via rapid dispersion of fine IL droplets

- Allow extraction to proceed with or without agitation for predetermined time

Phase Separation:

- Centrifuge to sediment IL phase

- Carefully collect IL phase using microsyringe

Analysis:

- Direct injection into analytical instrument (HPLC, GC, etc.)

- Alternatively, dilute or derivative as needed for detection

Table 1: Key Parameters for IL-DLLME Optimization

| Parameter | Optimization Considerations | Typical Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| IL Selection | Hydrophobicity, viscosity, chemical compatibility with analytes | [C₈MIM][PF₆] for PAHs [43] |

| IL Volume | Balance between enrichment factor and analytical sensitivity | 20-100 μL [43] |

| Disperser Solvent | Miscibility with IL and aqueous phase, toxicity | Acetone, methanol, acetonitrile (0.5-2 mL) [43] |

| Extraction Time | Equilibrium establishment, analysis throughput | Instantaneous to 5 minutes [43] |

| Salt Addition | Salting-out effect, ionic strength modification | 0-10% (w/v) [43] |

| pH Adjustment | Analyte ionization control, extraction efficiency | Compound-specific optimization [41] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the IL-DLLME process:

IL-DLLME Workflow

Single-Drop Microextraction (SDME) with ILs

SDME with ionic liquids utilizes a single microdroplet of IL suspended at the tip of a microsyringe needle, either directly immersed in the sample solution (DI-SDME) or exposed to the headspace above it (HS-SDME) [40]. The IL droplet serves as a miniature extraction phase that concentrates analytes from the sample matrix, then is directly retracted into the microsyringe for instrumental analysis.

Optimized IL-SDME Protocol for Pharmaceutical Compounds [40]:

Sample Preparation:

- Place aqueous pharmaceutical sample in appropriate vial with stirring capability

- Adjust matrix conditions (pH, ionic strength) to favor extraction

IL Selection:

- Choose IL with appropriate density, viscosity, and immiscibility with sample

- Consider functional groups for specific analyte interactions

Extraction Procedure:

- Expose IL droplet (1-10 μL) to sample solution or headspace

- Maintain controlled agitation and temperature during extraction

- Allow predetermined extraction time for equilibrium establishment

Drop Retrieval and Analysis:

- Retract IL droplet back into microsyringe

- Directly inject into analytical instrument

- For GC analysis, ensure IL thermal stability and compatibility

Table 2: Key Parameters for IL-SDME Optimization

| Parameter | Direct Immersion SDME | Headspace SDME |

|---|---|---|

| IL Requirements | High hydrophobicity, low solubility in water, appropriate viscosity | Moderate volatility for headspace analysis, thermal stability |

| Drop Volume | 1-10 μL | 1-5 μL |

| Extraction Time | 5-30 minutes | 5-30 minutes |

| Agitation | Essential for reducing boundary layer | Beneficial for sample homogeneity |