Green Chemistry in Drug Development: The Anastas-Warner Principles for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to green chemistry for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Green Chemistry in Drug Development: The Anastas-Warner Principles for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to green chemistry for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational 12 Principles of Green Chemistry established by Paul Anastas and John Warner, detail methodological applications in pharmaceutical synthesis and process design, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in implementing greener routes, and validate the approach through comparative analysis of traditional vs. green methods in terms of efficiency, cost, and environmental impact. The article synthesizes current knowledge to empower the biomedical field in adopting sustainable chemistry practices.

What is Green Chemistry? Defining the Anastas-Warner 12 Principles for Biomedical Research

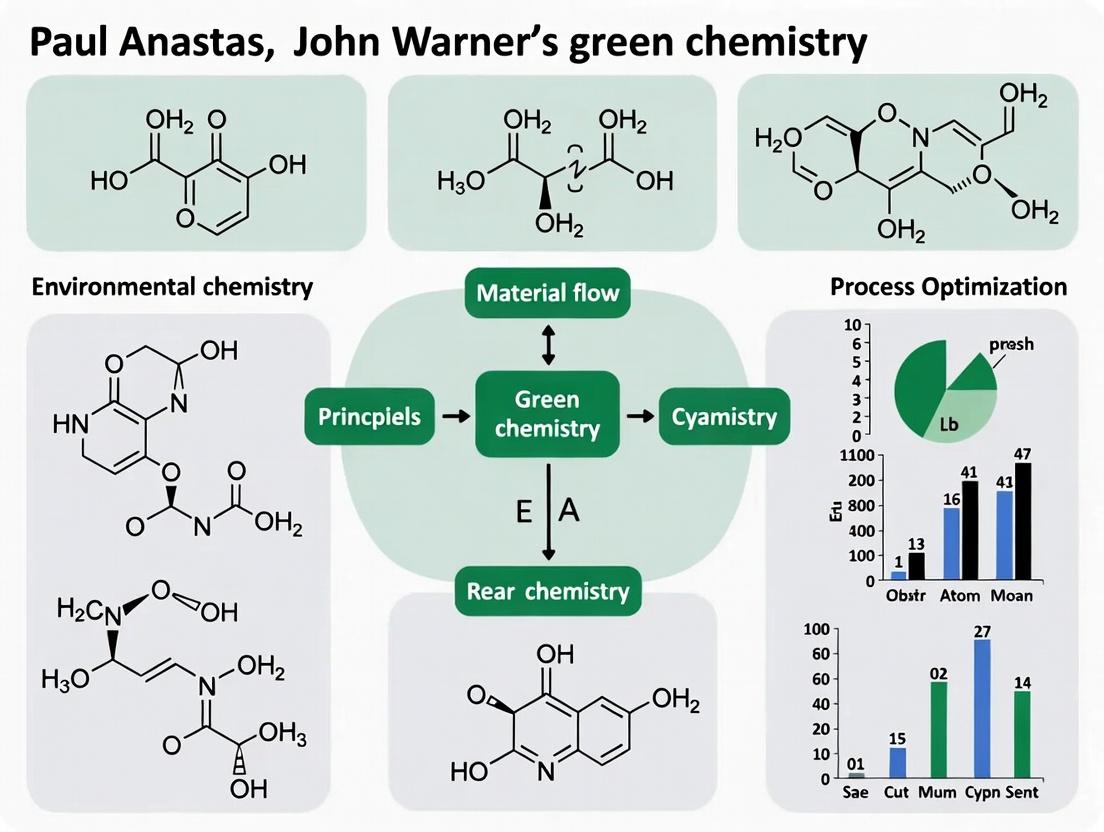

The research of Paul Anastas and John Warner established green chemistry not merely as a sub-discipline but as a foundational philosophy for modern chemical synthesis. Their seminal work posits that environmental impact and hazard are not inevitable byproducts of chemical innovation but can be designed out at the molecular level. This whitepaper contextualizes their principles within contemporary research and drug development, providing a technical guide to their implementation.

The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry: A Quantitative Framework

The core of Anastas and Warner's thesis is codified in the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics associated with each principle, providing targets for researchers.

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry with Associated Metrics

| Principle | Key Quantitative Metric(s) | Target/Benchmark for Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prevent Waste | E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) | Aim for <5-50 for Pharma (vs. traditional 25-100+) |

| 2. Atom Economy | % Atom Economy = (MW product/Σ MW reactants)*100 | Target >80% for key bond-forming steps |

| 3. Less Hazardous Synthesis | Acute Toxicity (LD50), Carcinogenicity Classification | Use reagents with LD50 > 500 mg/kg (oral, rat); avoid Class 1&2 carcinogens |

| 4. Designing Safer Chemicals | Biodegradability (% BOD), Bioaccumulation Factor (BCF) | >60% ultimate biodegradation; BCF < 1000 |

| 5. Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries | Process Mass Intensity (PMI), VOC emissions | Prefer water, scCO₂, or approved green solvents (e.g., Cyrene) |

| 6. Design for Energy Efficiency | Cumulative Energy Demand (CED), Reaction Temperature | Perform reactions at ambient T&P where possible |

| 7. Use Renewable Feedstocks | % Renewable Carbon Content | Maximize use of sugars, lipids, bio-derived platform molecules |

| 8. Reduce Derivatives | Number of Protection/Deprotection Steps | Minimize steps requiring temporary modification (e.g., protecting groups) |

| 9. Catalysis (prefer selective) | Turnover Number (TON), Turnover Frequency (TOF) | Prefer catalytic (esp. enzymatic, photocatalytic) over stoichiometric reagents |

| 10. Design for Degradation | Half-life in environment (t½, hydrolysis, photolysis) | Design APIs with benign degradation fragments; t½ in water < 365 days |

| 11. Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | In-line/On-line monitoring capability | Implement PAT (Process Analytical Technology) for key intermediates |

| 12. Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Process Safety Index (e.g., Dow F&EI), Flash Point | Design processes with minimal explosion, fire, or release potential |

Core Experimental Protocols: Implementing the Principles

Protocol 1: Assessing Atom Economy in API Synthesis

Objective: To calculate and optimize the atom economy for a key bond-forming step in active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis.

- Define the Balanced Reaction Equation: Write the complete equation for the synthetic step, including all stoichiometric reagents and by-products.

- Calculate Molecular Weights: Determine the molecular weight (MW) of the target product and the sum of the MWs of all reactants.

- Compute Atom Economy: Apply the formula: Atom Economy (%) = (MW of Desired Product / Σ MW of All Reactants) x 100.

- Iterative Redesign: Evaluate alternative disconnections, reagents, or routes. Catalytic or rearrangement reactions typically achieve 100% atom economy.

Protocol 2: Determination of Environmental (E) Factor

Objective: To quantify the mass efficiency of a synthetic process.

- Mass Inventory: Accurately weigh all input materials (raw materials, solvents, reagents, catalysts) used in the process (kg).

- Isolate and Weigh Product: Obtain the mass of the purified, dry product (kg).

- Calculate Total Waste: Total Waste (kg) = Total mass of inputs - Mass of product.

- Compute E-Factor: E-Factor = Total Waste (kg) / Mass of Product (kg). Segment analysis (e.g., distinguishing organic, aqueous, solid waste) is recommended for targeted improvement.

Visualization of Green Chemistry Decision Pathways

Title: Green Chemistry Route Design Workflow

Title: Interdisciplinary Impact of Green Chemistry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents & Materials for Green Chemistry Research

| Item/Category | Function in Green Chemistry | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Solvents | Replace hazardous, volatile organic solvents (VOCs). | Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone): Bio-derived, dipolar aprotic solvent alternative to DMF/DMAc. 2-MeTHF: Renewable, preferable to THF. scCO₂: Non-toxic, tunable solvent for extraction and reactions. |

| Supported Catalysts | Enable efficient catalysis with easy recovery and reuse, reducing metal waste. | Silica- or polymer-supported reagents (e.g., PS-TPP, immobilized enzymes). Heterogeneous metal catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, Ti on silica). |

| Bio-Catalysts | Provide high selectivity under mild conditions using renewable resources. | Engineered enzymes (e.g., ketoreductases for chiral alcohol synthesis, transaminases). Whole-cell systems for multi-step biotransformations. |

| Renewable Building Blocks | Shift feedstock base from petroleum to biomass. | Platform molecules: 5-HMF, levulinic acid, succinic acid, glucaric acid. Chiral pool: Amino acids, terpenes, sugars. |

| In-line Analytics (PAT) | Enable real-time monitoring for waste prevention and control. | ReactIR/ReactRaman: For real-time reaction profiling. Inline HPLC/UPC²: For continuous purity assurance. |

| Safer Reagents | Reduce intrinsic hazard while maintaining reactivity. | Polymer-bound reagents for reduced exposure. Iron, copper catalysts vs. heavy metals. Diethyl carbonate as a greener ethylating agent. |

The foundational work of Paul Anastas and John Warner established the intellectual framework for preventing pollution at the molecular level. Their seminal 1998 publication, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, introduced the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, a paradigm shift from remediation to intrinsic design safety. This whitepaper reframes those principles for contemporary pharmaceutical R&D, positing that molecular design is the most effective point of intervention to eliminate waste, hazard, and energy inefficiency. The core philosophy is not additive but foundational: environmental performance must be a primary constraint in the structure-activity relationship (SAR) from the earliest discovery phases.

Quantitative Analysis of Traditional vs. Green Metrics in Pharma

The environmental impact of drug manufacturing is starkly quantified by the Environmental Factor (E-Factor) and Process Mass Intensity (PMI), defined as the total mass of materials used per mass of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) produced. Recent industry analyses reveal the scale of the opportunity.

Table 1: Comparative Process Efficiency Metrics (2020-2024 Industry Benchmarks)

| API Synthesis Type | Average PMI (kg/kg API) | Average E-Factor (kg waste/kg API) | Typical Solvent Contribution to Waste |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Small Molecule | 100 - 250 | 50 - 200 | 80-90% |

| Biotechnology (mAb) | 5,000 - 10,000 | 4,000 - 9,000 | 30-50% |

| Green Chemistry-Optimized | 25 - 50 | 10 - 25 | 60-75% |

| Continuous Flow Synthesis | 15 - 40 | 5 - 20 | 50-70% |

Table 2: Hazard Reduction via Molecular Design (Selected Case Studies)

| Design Intervention | Traditional Reagent | Green Alternative | Toxicity Reduction (GHS Category) | Waste Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Selection | Heavy Metal (Pd, Pt) | Fe-based Organocatalyst | Acute Toxicity: Cat. 1 → Non-hazardous | Metal waste eliminated |

| Oxidation Method | Cr(VI) reagents | O2 / Biocatalyst | Carcinogen Mutagen → Non-hazardous | >90% |

| Chlorinated Solvent | DCM, Chloroform | 2-MeTHF, Cyrene | Health Hazard Cat. 2 → Low Hazard | 100% (direct replacement) |

| Protecting Group | PMB-Cl (Cl source) | Dihydrolevoglucosenone | Corrosive → Non-corrosive | 40% step reduction |

Foundational Experimental Protocols for Green Molecular Design

Protocol: In Silico Toxicity Screening Early in Lead Optimization

Objective: To predict and avoid molecules with inherent environmental persistence (P), bioaccumulation potential (B), and toxicity (T) using computational tools before synthesis. Methodology:

- Descriptor Calculation: For all lead series (≥100 compounds), calculate key PBT descriptors: log P (octanol-water), molecular weight, topological polar surface area, and biodegradability probability using software like EPI Suite or OPEN-SAR.

- Threshold Application: Flag compounds violating two or more criteria: log P > 4.5, Molecular Weight > 500 g/mol, Biodegradability probability < 0.5.

- Alternative Design: For flagged compounds, use fragment replacement libraries to suggest isosteres with lower log P and higher predicted biodegradability. Recalculate descriptors iteratively.

- Validation: Synthesize top 5 green-designed analogs and benchmark against original lead for key pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties.

Protocol: Atom Economy-Driven Route Scouting

Objective: To maximize the incorporation of reactant atoms into the final API, minimizing byproduct formation. Methodology:

- Retrosynthetic Analysis with Green Metrics: For a target molecule, generate 3-5 divergent retrosynthetic pathways using AI-assisted tools (e.g., ASKCOS, Synthia).

- Calculate Atom Economy (AE): For each proposed step and the overall sequence: AE = (MW of product / Σ MW of reactants) x 100%.

- Prioritize Convergent & Catalytic Steps: Select routes with AE > 85% per step. Favor reactions with high inherent AE (e.g., Diels-Alder, olefin metathesis, rearrangement) over traditional coupling reactions requiring stoichiometric activators.

- Experimental Validation: Conduct small-scale (100 mg) reactions for the top two routes. Isolate and characterize all major byproducts (>5%) via LC-MS to confirm AE calculations and identify real waste streams.

Visualizing the Green Chemistry Decision Framework

Diagram 1: The Iterative Green Chemistry Design & Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Linear vs. Convergent Synthesis: Atom Economy Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents & Materials for Green Molecular Design Experiments

| Item Name | Category | Function & Green Rationale | Example Supplier/CAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-MeTHF (2-Methyltetrahydrofuran) | Solvent | Bio-derived from furfural; superior replacement for THF, DCM, and ethers in extractions and reactions. Lower persistence than THF. | Sigma-Aldrich, 96-47-9 |

| Cyrene (Dihydrolevoglucosenone) | Solvent | Non-toxic, non-mutagenic dipolar aprotic solvent derived from cellulose. Direct replacement for DMF, NMP, and DMAc. | Circa Group, 53716-82-8 |

| SiliaCat DPP-Pd | Heterogeneous Catalyst | Polystyrene-immobilized Pd catalyst for cross-couplings. Enables simple filtration recovery, reduces metal leaching to <1 ppm in API. | SiliCycle, n/a |

| CAL-B (Candida antarctica Lipase B) | Biocatalyst | Immobilized enzyme for enantioselective resolutions, esterifications, and ammonolysis. Operates in water or solvent-free conditions. | Novozymes 435, n/a |

| Polymeric Reagents (PS-TsCl, MP-Carbonate) | Functionalized Supports | Enable reagent sequestration and purification by filtration. Eliminate aqueous workups, reducing solvent waste. | ArgoFilm, Biotage |

| Continuous Flow Reactor (Lab-scale) | Equipment | Enables precise control of exothermic reactions, use of unstable intermediates, and dramatic reduction in solvent volume and energy. | Vapourtec, Chemtrix |

| EcoScale Calculator | Software | Assigns penalty points to non-ideal reaction parameters (yield, cost, safety, etc.) to quantitatively compare greenness of synthetic routes. | Free web tool |

| DOZN 2.0 Web Tool | Software | Quantitative green chemistry evaluator based on the 12 Principles, providing a score to benchmark against alternatives. | MilliporeSigma |

The seminal work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, formalized in their 1998 book, established Green Chemistry as a proactive, fundamental framework to reduce or eliminate hazardous substances in the design, manufacture, and application of chemical products. Their foundational thesis posits that environmental and economic goals in chemistry are not mutually exclusive but can be synergistically achieved through intelligent molecular design. Within drug discovery, this paradigm shift moves sustainability from an end-of-pipe regulatory concern to a core driver of innovation, aiming to reduce the resource intensity and environmental burden of pharmaceutical development while maintaining efficacy and safety.

The 12 Principles: A Technical Guide for Medicinal Chemistry

The following section details each principle with specific applications, quantitative data, and experimental protocols relevant to modern drug discovery.

Prevention

It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it is formed.

- Application: Designing synthetic routes with high atom economy to minimize byproduct formation at the outset.

- Protocol (Model Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling for Biaryl Synthesis):

- Charge a microwave vial with aryl halide (1.0 mmol), aryl boronic acid (1.2 mmol), and Pd catalyst (e.g., SPhos Pd G3, 0.5 mol%).

- Add K3PO4 (2.0 mmol) as base and a green solvent mixture (e.g., Cyrene:Water 9:1, 2 mL).

- Seal the vial and heat under microwave irradiation at 100°C for 10 minutes.

- Cool, dilute with ethyl acetate, filter through a pad of Celite, and concentrate. Analyze yield and purity by HPLC and NMR. Calculate Atom Economy: (MW of desired product / Σ MW of all reactants) x 100%.

- Data: Comparison of Atom Economy for Common Reactions in API Synthesis

| Reaction Type | Typical Atom Economy | Green Chemistry Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | 100% | Maintain high economy |

| Rearrangement | 100% | Maintain high economy |

| Substitution | Moderate to Low | Replace with addition/rearrangement |

| Elimination | Low | Minimize use |

| Wittig Reaction | <40% | Use catalytic olefination |

Atom Economy

Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize the incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product.

- Application: Favoring catalytic C-H activation over traditional cross-coupling, which requires pre-functionalized substrates (e.g., halides) and generates stoichiometric metallic waste.

Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses

Wherever practicable, synthetic methodologies should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment.

- Application: Replacing phosgene and its derivatives in carbamate and urea synthesis with safer alternatives like carbonyl diimidazole (CDI) or employing oxidative carbonylation with CO and a catalyst.

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- DMC (Dimethyl Carbonate): Non-toxic, biodegradable alternative to methyl halides or dimethyl sulfate for methylation.

- Cyrene (Dihydrolevoglucosenone): Bio-derived, dipolar aprotic solvent replacement for toxic DMF or NMP.

- Immobilized Enzymes (e.g., CAL-B Lipase): For regioselective acylations, avoiding heavy metal catalysts.

- Polystyrene-Supported Burgess Reagent: For dehydration reactions, eliminating soluble reagent waste.

Designing Safer Chemicals

Chemical products should be designed to preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity.

- Application: In silico toxicity prediction (e.g., using DEREK, Toxtree) early in lead optimization to flag and redesign structures with mutagenic alerts (e.g., aniline impurities, Michael acceptors).

Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries

The use of auxiliary substances (e.g., solvents, separation agents) should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used.

- Protocol (Solvent Selection Guide for Crystallization):

- Using the CHEM21 or GSK solvent sustainability guides, rank potential solvents based on safety, health, and environmental (SHE) score.

- Perform small-scale (10 mg) crystallization trials in 96-well plates with primary candidates like ethyl acetate, 2-MeTHF, CPME, or ethanol.

- Use automated microscopy and XRD to assess crystal form, purity, and yield.

- Select the safest, most effective solvent. Avoid Class 1 (benzene, CCl4) and Class 2 (DMF, DCM, NMP) solvents per ICH Q3C.

- Data: Solvent Environmental Impact Comparison

| Solvent | GSK SHE Score (Lower=Better) | Boiling Point (°C) | ICH Class | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 1 | 100 | - | Ideal |

| Ethanol | 5 | 78 | 3 | Preferred, renewable |

| 2-MeTHF | 6 | 80 | 3 | Bio-derived, good for Grignard |

| Ethyl Acetate | 8 | 77 | 3 | Common, biodegradable |

| Heptane | 9 | 98 | 3 | - |

| Acetonitrile | 10 | 82 | 2 | High waste, avoid |

| DMF | 14 | 153 | 2 | Reprotoxic, avoid |

| DCM | 16 | 40 | 2 | Carcinogenic, avoid |

Design for Energy Efficiency

Energy requirements of chemical processes should be recognized for their environmental and economic impacts and should be minimized.

- Application: Adopting flow chemistry for exothermic or high-temperature reactions, enabling precise temperature control, improved heat transfer, and reduced reaction times.

Use of Renewable Feedstocks

A raw material or feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting whenever technically and economically practicable.

- Application: Developing biocatalytic routes to chiral intermediates using engineered enzymes (ketoreductases, transaminases) starting from sugar-based feedstocks, replacing petroleum-derived racemates and wasteful resolution processes.

Reduce Derivatives

Unnecessary derivatization (use of blocking groups, protection/deprotection, temporary modification of physical/chemical processes) should be minimized or avoided if possible.

- Application: Designing synthetic routes with innate chemoselectivity (e.g., leveraging orthogonal reactivity) or employing enzymatic catalysis known for its selectivity, reducing the need for protecting groups.

Catalysis

Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents.

- Application: Widespread adoption of Pd, Ni, Cu, and photoredox catalysts for C-C and C-X bond formation, with a focus on developing immobilized heterogeneous catalysts or metal-free organocatalysts for easier recovery and reduced metal contamination in APIs.

Design for Degradation

Chemical products should be designed so that at the end of their function they break down into innocuous degradation products and do not persist in the environment.

- Application: Incorporating biodegradable motifs (e.g., esters, amides susceptible to hydrolysis) into non-persistent fluorophores for imaging or into excipients, while ensuring API stability is not compromised.

Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention

Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances.

- Application: Implementing Process Analytical Technology (PAT) such as in-line FTIR, Raman, or UV/Vis spectroscopy to monitor reaction progression and key impurity formation in flow reactors, enabling immediate feedback and control.

Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention

Substances and the form of a substance used in a chemical process should be chosen to minimize the potential for chemical accidents, including releases, explosions, and fires.

- Application: Replacing pyrophoric reagents (e.g., t-BuLi) with safer, more stable alternatives (e.g., Grignard reagents from Mg turnings) or using continuous flow to generate and consume hazardous intermediates in situ.

Integrating Principles: A Green Drug Discovery Workflow

Diagram: Green Chemistry in Drug Discovery Flow

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, as conceived by Anastas and Warner, provide a robust, systematic framework to re-engineer drug discovery. By integrating these principles from target identification through to manufacturing, the pharmaceutical industry can achieve significant reductions in waste, hazard, and cost, driving innovation towards more sustainable and socially responsible therapeutics. The adoption of this framework is no longer just an environmental imperative but a cornerstone of modern, efficient, and competitive pharmaceutical R&D.

The principles of Green Chemistry, as formally articulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner, provide a foundational framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances. This whitepaper examines three core quantitative metrics—Atom Economy, E-Factor, and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—that operationalize the 12 Principles, enabling researchers and development professionals to measure, benchmark, and improve the environmental performance of chemical syntheses, particularly in pharmaceutical development.

Atom Economy

Definition & Theoretical Basis Atom Economy, a concept championed by Barry Trost, evaluates the efficiency of a chemical reaction by calculating the proportion of reactant atoms that are incorporated into the desired final product. It directly connects to Anastas and Warner's 2nd Principle (Atom Economy) and is a powerful tool for preventing waste at the molecular design stage, rather than treating it after generation.

Calculation & Methodology

Experimental Protocol for Calculation:

- Write a balanced chemical equation for the synthetic transformation.

- Obtain the molecular weights (g/mol) of the desired product and all stoichiometric reactants from reliable sources (e.g., PubChem, supplier catalogs).

- Sum the molecular weights of all reactants, respecting stoichiometric coefficients.

- Apply the formula above to calculate the percentage.

Quantitative Data

| Reaction Type | Typical Atom Economy Range | Example Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | 100% | Ethene + HBr → Bromoethane |

| Rearrangement | 100% | Claisen rearrangement |

| Substitution | Moderate | SN2 reactions |

| Elimination | Low | Dehydrohalogenation to form alkenes |

Environmental Factor (E-Factor)

Definition & Theoretical Basis Introduced by Roger Sheldon, the E-Factor measures the actual waste generated per unit of product manufactured. It quantifies the realized waste, accounting for yield, solvents, reagents, and process chemicals, aligning with the 1st Principle (Prevention) and the 3rd Principle (Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses). It provides a cradle-to-gate perspective for a specific process.

Calculation & Methodology

Experimental Protocol for Measurement:

- Scale: Perform the reaction at a representative laboratory or pilot scale.

- Inventory: Record the exact masses (or volumes converted to mass using density) of all input materials: reactants, catalysts, solvents, work-up, and purification agents.

- Product Isolation: Accurately weigh the mass of the isolated, pure final product.

- Waste Calculation: Subtract the mass of the final product from the total mass of all input materials. This remainder is the total process waste.

- Calculation: Divide the total waste mass by the product mass.

Quantitative Data

| Industry Sector | Typical E-Factor Range (kg waste/kg product) |

|---|---|

| Oil Refining | <0.1 |

| Bulk Chemicals | 1–5 |

| Fine Chemicals | 5–50 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 25–100+ |

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

Definition & Theoretical Basis Life Cycle Assessment is a comprehensive, systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life—from raw material extraction (cradle) to disposal or recycling (grave). It embodies the holistic, systems-thinking approach central to Green Chemistry, particularly the broader context of sustainability beyond the reaction flask.

Methodological Framework (ISO 14040/14044) Experimental Protocol for Conducting an LCA:

- Goal and Scope Definition:

- Define the purpose, functional unit (e.g., "manufacture 1 kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient"), and system boundaries (e.g., cradle-to-gate vs. cradle-to-grave).

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis:

- Compile a quantified inventory of all energy and material inputs (e.g., petroleum, water, minerals) and environmental releases (e.g., CO2, wastewater, solid waste) associated with the defined system.

- Data is collected from laboratory notebooks, pilot plant records, supplier Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), and commercial LCA databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi).

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA):

- Translate inventory data into potential environmental impacts using impact categories (see table below).

- Common methodologies: ReCiPe, TRACI, CML.

- Interpretation:

- Analyze results, check sensitivity, and draw conclusions to inform decision-making (e.g., comparing two synthetic routes).

Quantitative Impact Categories

| Impact Category | Unit of Measurement | Example Contributing Input/Output |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | kg CO2-equivalent | Carbon dioxide, methane emissions |

| Acidification Potential | kg SO2-equivalent | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides |

| Eutrophication Potential | kg PO4-equivalent | Phosphate, nitrate releases |

| Abiotic Resource Depletion | kg Sb-equivalent | Extraction of metals, fossil fuels |

| Water Use | Cubic meters (m³) | Process water, irrigation for feedstocks |

Visualization of Relationships

Title: Green Chemistry Metrics Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function in Green Chemistry Context |

|---|---|

| Catalytic Reagents | Enable lower-energy pathways, higher atom economy, and replace stoichiometric, waste-generating reagents. |

| Alternative Solvents (e.g., water, scCO2, bio-based) | Reduce use of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and hazardous solvents, improving E-Factor and safety. |

| Renewable Feedstocks | Shift raw material sourcing from petrochemicals to biomass, improving LCA profile (resource depletion). |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Calculator | Software/tool to track all material inputs against product output, directly calculating E-Factor. |

| LCA Software (e.g., SimaPro, OpenLCA) | Platforms to model and analyze cradle-to-grave environmental impacts of chemical processes. |

| Continuous Flow Reactors | Technology enabling precise reaction control, reduced solvent/sample use, and inherently safer design. |

The seminal work of Paul Anastas and John Warner, codified in their 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, provides the foundational thesis for modern sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. This whitepaper examines the current convergence of stringent global regulations and ambitious corporate sustainability targets, framing them not as mere compliance challenges but as direct applications of Anastas and Warner's principles. For researchers and drug development professionals, this translates into a paradigm shift where atom economy, waste prevention, and safer solvents are integral to process design from Discovery through Commercial Manufacturing.

Pharmaceutical innovation is increasingly measured by both therapeutic efficacy and environmental footprint. The following tables summarize key quantitative drivers.

Table 1: Key Global Regulatory Drivers Impacting Pharma Sustainability (2023-2025)

| Regulatory Body/Initiative | Key Metric/Target | Implementation Timeline | Potential Impact on R&D |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Mandatory Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) for new Marketing Authorizations | Phased from 2025 | Requires API ecotoxicity data; promotes greener molecular design. |

| U.S. FDA (CCEP) | Acceptance of Continuous Manufacturing; Guidance on Genotoxic Impurities | Ongoing (Pilot Active) | Encourages flow chemistry (Principle #6), reduces waste & energy. |

| China MEE | Stricter limits on VOCs & API residues in wastewater | 2023-2025 Standards | Drives adoption of water-based or solvent-free reactions (Principle #5). |

| UN SDGs | Corporate reporting on SDG 3, 6, 12, 13 | Annual Reporting | Links operational EHS metrics to global sustainability goals. |

Table 2: Industry-Wide Sustainability Targets (Based on 2023 IFPMA Data)

| Metric | 2025 Industry Average Target | 2030 Ambitious Target | Green Chemistry Principle Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | Reduce by 20% (vs. 2016 baseline) | Reduce by 50% | #2 (Atom Economy), #1 (Waste Prevention) |

| Green Solvent Usage | 50% of total solvent volume | >75% of total solvent volume | #5 (Safer Solvents & Auxiliaries) |

| Energy Consumption | Carbon-neutral for direct operations (Scope 1 & 2) | Full value-chain decarbonization | #6 (Energy Efficiency) |

| Water Consumption | Reduce by 10% in water-stressed areas | Reduce by 25% in water-stressed areas | #1 (Waste Prevention) |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Green Chemistry in API Synthesis

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments demonstrating the alignment of modern pharmaceutical research with regulatory and sustainability goals.

Protocol 1: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis via Organocatalysis (Replacing Heavy Metal Catalysts)

Objective: To synthesize a chiral intermediate for a kinase inhibitor using a proline-derived organocatalyst, eliminating the need for rhodium or palladium catalysts (addressing Principle #9—Catalysis and regulatory concerns over metal residues).

Materials:

- Substrate: 4-(4-Nitrobenzyl)cyclohexanone (10 mmol)

- Catalyst: (S)-Proline-tert-butyl ester (0.1 mmol, 1 mol%)

- Solvent: Ethyl acetate (green alternative to DMF or DCM)

- Quenching Agent: Saturated aqueous NH₄Cl solution

- Purification: Biobased silica gel for column chromatography.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: In a 50 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, dissolve the substrate (2.17 g) and catalyst (21.3 mg) in 20 mL of ethyl acetate.

- Reaction Execution: Stir the reaction mixture at 25°C (room temperature) for 16 hours. Monitor reaction completion by TLC (9:1 Hexanes:EtOAc, UV visualization).

- Work-up: Quench the reaction by adding 10 mL of saturated NH₄Cl solution. Transfer to a separatory funnel, extract the aqueous layer with ethyl acetate (3 x 15 mL). Combine the organic layers.

- Purification: Dry the combined organic extracts over anhydrous MgSO₄, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product via flash column chromatography using a biobased silica gel stationary phase and a gradient elution of Hexanes to EtOAc.

- Analysis: Determine enantiomeric excess (ee) by chiral HPLC (Chiralpak AD-H column). Calculate PMI: (Total mass of materials used in grams) / (grams of purified product).

Protocol 2: Continuous Flow Synthesis of a Small Molecule API Intermediate

Objective: To demonstrate the enhancement of energy efficiency, safety, and yield for a nitration reaction using continuous flow technology, directly applicable to regulatory-compliant manufacturing.

Materials:

- Reactant A: Benzoic acid in concentrated sulfuric acid (1.0 M)

- Reactant B: Fuming nitric acid (1.05 M in concentrated H₂SO₄)

- Equipment: Two HPLC pumps, PTFE tubing coil reactor (10 mL internal volume), back-pressure regulator (BPR, set to 50 psi), ice bath, continuous flow liquid-liquid separator.

Methodology:

- System Priming: Calibrate pumps for accurate delivery of Reactant A and Reactant B at desired flow rates (e.g., 0.5 mL/min each).

- Reaction Execution: Connect pump outlets to a T-mixer, which feeds into the PTFE coil reactor submerged in an ice-water bath (0-5°C). Attach the BPR at the reactor outlet. Start pumps simultaneously to achieve a total residence time of 10 minutes.

- In-line Quenching & Separation: Direct the reactor outflow into a vigorously stirred vessel containing ice water for quenching. Alternatively, use an in-line mixer with a chilled water stream, followed by a continuous liquid-liquid separator to isolate the organic phase containing the nitro product.

- Process Monitoring: Use an in-line FTIR or UV probe immediately before the BPR to monitor conversion in real-time.

- Data Collection: Collect the organic phase over a defined period. Isolate the product via crystallization. Calculate E-Factor: (mass of total waste) / (mass of product), and compare to batch process data.

Visualizing the Strategic and Molecular Pathways

Title: Drivers & Outcomes of Green Pharma Strategy

Title: Green Chemistry Integrated Drug Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Green Pharmaceutical Research

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Function & Green Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Solvents | Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone), 2-MeTHF, Cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) | Safer, often biobased, replacements for dipolar aprotic solvents (DMF, NMP) or hazardous ethers (THF). Aligns with Principle #5. |

| Heterogeneous & Organocatalysts | Immobilized enzymes, polymer-supported reagents, proline derivatives | Enable catalysis (Principle #9), reduce metal contamination, simplify separation, and improve recyclability. |

| Flow Chemistry Systems | Microreactor chips, packed-bed columns, in-line mixers | Enhance heat/mass transfer (Principle #6), improve safety with hazardous intermediates, reduce scale-up footprint. |

| Green Derivatization Reagents | DMT-MM, CDI for amide bond formation | Promote atom-efficient coupling reactions with fewer toxic byproducts compared to traditional agents like DCC. |

| Analytical Method Greenness Tools | AGP (Analytical Greenness Profile) calculators, UHPLC with water/ethanol gradients | Quantify and reduce the environmental impact of analytical methods (solvent use, waste generation). |

| Biobased Chromatography Media | Silica gel from rice husk ash, cellulose-based chiral stationary phases | Utilize renewable resources for purification, moving towards a circular economy in lab operations. |

Implementing Green Chemistry: Practical Strategies and Case Studies in Drug Synthesis

Green Chemistry, as articulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner in their 12 foundational principles, provides a framework for reducing the environmental and health impacts of chemical products and processes. This guide focuses on the practical application of Principle 4 (Designing Safer Chemicals) and Principle 7 (Use of Renewable Feedstocks), viewed through the lens of contemporary pharmaceutical and fine chemical research. The overarching thesis of Anastas and Warner positions these principles not as constraints, but as drivers of innovation that yield efficacious and economically viable products with inherently reduced hazard.

Technical Guide: Designing Safer Chemicals (Principle 4)

Core Philosophy: The design of chemical products should preserve efficacy of function while reducing toxicity. This requires a fundamental understanding of the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity (SAR) and environmental fate.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Hazard Assessment Protocols

A cornerstone methodology for Principle 4 is the use of in silico predictive toxicology to guide synthesis.

Protocol 1.1: In Silico Toxicity Screening for Molecular Design

- Objective: Predict key toxicity endpoints (e.g., mutagenicity, aquatic toxicity, endocrine disruption) for candidate molecules prior to synthesis.

- Software/Tools: Utilize platforms such as OECD QSAR Toolbox, VEGA, or commercial suites like StarDrop or Derek Nexus.

- Methodology: a. Draw/Specify the molecular structure of the candidate. b. Define the chemical category (e.g., acrylate, aromatic amine). The software identifies analogous structures with experimental data. c. Apply relevant "profiles" and "alerts" based on known toxicophores (e.g., epoxide rings, unsubstituted aromatic amines). d. Run probabilistic models (e.g., read-across, consensus QSAR models) for endpoints of concern. e. Key Step: Analyze the results to identify specific structural motifs contributing to predicted hazard.

- Design Iteration: Modify the candidate structure to eliminate or mitigate the toxicophore (e.g., through steric hindrance, electronic deactivation, or metabolic blocking groups) while maintaining core functionality. Re-run the prediction cycle.

- Validation: Prioritize synthesis of the lowest-hazard design for in vitro confirmatory testing (e.g., Ames test, cytotoxicity assays).

Table 1: Common Toxicophores and Safer Design Strategies

| Toxicophore | Associated Hazard | Safer Design Strategy | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxide | Mutagenicity, DNA alkylation | Replace with aziridine (with electron-withdrawing groups) or redesign route to avoid intermediate | Reduces electrophilicity and DNA reactivity |

| Aromatic Nitro Group | Mutagenicity, Reduction to toxic arylamines | Substitute with safer bioisostere (e.g., cyanide, ester) or use in immobilized form | Prevents metabolic activation to reactive species |

| Persistent, Bioaccumulative Chains (e.g., PFAS) | Environmental persistence, chronic toxicity | Use shorter, degradable alkyl chains or non-fluorinated alternatives | Enhances environmental degradation and reduces bioaccumulation potential |

| Reactive Aldehyde | Protein cross-linking, irritation | Mask as acetal or use in situ generation for immediate consumption | Minimizes exposure to free, reactive form |

Title: Safer Chemical Design Workflow

Technical Guide: Utilizing Renewable Feedstocks (Principle 7)

Core Philosophy: Raw material feedstock should be renewable rather than depleting, wherever technically and economically practicable. This principle addresses resource scarcity and often reduces the net carbon footprint of a process.

Experimental Protocol for Biobased Platform Chemical Conversion

Protocol 2.1: Catalytic Upgrading of Levulinic Acid to a Pharmaceutical Intermediate Levulinic acid, a platform chemical derived from cellulosic biomass (e.g., via acid hydrolysis), serves as a model renewable feedstock.

- Objective: Convert levulinic acid to gamma-valerolactone (GVL), a versatile green solvent and intermediate, and subsequently to a targeted pharmaceutical precursor (e.g., 1,4-pentanediol).

- Materials:

- Levulinic acid (≥97%, from biomass)

- Heterogeneous catalyst: Ru/SnO2 (5 wt% Ru)

- High-pressure Parr reactor (100 mL)

- Hydrogen gas (H2, 99.99%)

- Solvent: Water or GVL (for solvent-free reactions)

- Methodology: a. Charge the reactor with levulinic acid (5.0 g, 43 mmol) and Ru/SnO2 catalyst (0.25 g, 5 wt% loading relative to substrate). b. Purge the reactor three times with H2 to ensure an inert atmosphere. c. Pressurize the reactor with H2 to 30 bar at room temperature. d. Heat the reactor to 200°C with vigorous stirring (1000 rpm) and maintain for 4 hours. e. Cool the reactor to room temperature in an ice bath and carefully vent excess pressure. f. Separate the catalyst via filtration. Analyze the liquid product mixture by GC-MS and NMR to determine conversion and selectivity. g. Downstream Processing: The resulting GVL can be further hydrogenated over a Cu-ZrO2 catalyst at 140°C and 50 bar H2 to yield 1,4-pentanediol, a potential monomer or pharmaceutical building block.

Table 2: Comparison of Feedstock Sources for Key Chemical Intermediates

| Intermediate | Traditional Petrochemical Feedstock & Route | Renewable Feedstock & Route | Key Advantage (Renewable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipic Acid | Benzene -> Cyclohexane -> KA Oil -> Nitric Acid Oxidation | D-Glucose (Fermentation) -> cis,cis-Muconic Acid -> Hydrogenation | Avoids benzene and N2O greenhouse gas byproduct |

| 1,4-Pentanediol | Propylene -> Allyl Alcohol -> Hydroformylation -> Hydrogenation | Cellulosic Biomass -> Levulinic Acid -> GVL -> Hydrogenation | Uses inedible biomass, lower process energy intensity |

| Polyethylene Furanoate (PEF) | Ethylene Glycol + Terephthalic Acid (from p-xylene) | Ethylene Glycol + FDCA (from fructose dehydration/oxidation) | Superior barrier properties, 100% biobased carbon content |

Title: Renewable Feedstock Valorization Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Green Chemistry Experimentation (Principles 4 & 7)

| Item/Reagent | Function in Research | Relevance to Principles |

|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software for predicting chemical toxicity based on structural alerts and read-across. | Principle 4: Enables a priori design of safer molecules by identifying and avoiding toxicophores. |

| Biobased Platform Chemicals (e.g., Levulinic acid, Succinic acid, HMF) | Renewable starting materials for synthesizing polymers, solvents, and fine chemicals. | Principle 7: Direct replacement for petrochemical-derived feedstocks (e.g., adipic acid, BTX). |

| Supported Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ru/SnO2, Pd on carbon, immobilized enzymes) | Heterogeneous catalysts for selective hydrogenation, oxidation, or rearrangement of biobased substrates. | Both: Enables efficient, selective conversion of renewables (P7) and can replace hazardous stoichiometric reagents (P4). |

| Green Solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF, Cyrene, Supercritical CO2) | Reaction media with improved environmental, health, and safety profiles. | Principle 4: Reduces exposure to volatile, flammable, or toxic solvents (e.g., benzene, DCM). |

| In Vitro Toxicity Assay Kits (Ames II, HepG2 cytotoxicity) | Biological assays for experimental validation of predicted low toxicity. | Principle 4: Provides essential biological data to confirm safer chemical design. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software (e.g., SimaPro, GaBi) | Quantifies environmental impacts (carbon, water, energy) across a product's lifecycle. | Principle 7: Critical for verifying the net benefit of switching to a renewable feedstock. |

The synergistic application of Principles 4 and 7 represents a paradigm shift in sustainable molecular design. For the pharmaceutical researcher, this means developing Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) with inherently reduced environmental persistence and toxicity (e.g., via the design of readily biodegradable auxiliaries or metabolically labile prodrugs) while sourcing key chiral pools or building blocks from fermentation or catalytic upgrading of biomass. The work of Anastas and Warner compels the field to view these principles not in isolation, but as interconnected components of a holistic strategy for innovation that minimizes hazard at the molecular level and maximizes resource sustainability from the outset.

The ninth principle of Green Chemistry, as articulated by Paul Anastas and John Warner, states: Catalytic reagents (as selective as possible) are superior to stoichiometric reagents. Within the context of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis, this principle is paramount for minimizing waste, enhancing energy efficiency, and improving selectivity to reduce downstream purification burdens. This guide explores modern catalytic methodologies that embody this principle, moving beyond traditional stoichiometric processes toward sustainable, atom-economical transformations critical for modern drug development.

Quantitative Comparison of Catalytic vs. Stoichiometric Methods

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for catalytic versus traditional stoichiometric approaches in common API synthetic steps, based on recent literature and industrial case studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Catalytic vs. Stoichiometric Methods in API Synthesis

| Synthetic Transformation | Stoichiometric Method (Typical Reagent) | Catalytic Method (Typical Catalyst) | Atom Economy (Stoich.) | Atom Economy (Catalytic) | Estimated E-Factor Reduction | Selectivity Improvement (ee/regio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Oxidation | Jones Reagent (CrO₃/H₂SO₄) | TEMPO/NaOCl (Organocatalytic) | ~40% | ~85% | 60-75% | High Chemoselectivity |

| Amine Synthesis (Reductive Amination) | NaBH₄ or NaBH₃CN | Pd/C or Ir-based Transfer Hydrogenation | 30-50% | 70-90% | 50-70% | Improved Diastereoselectivity |

| Cross-Coupling (C-C Bond) | Organometallic (e.g., R-MgBr) Stoichiometric | Pd(PPh₃)₄ (Suzuki, Negishi) | <35% | >80% | 70-85% | High Regioselectivity |

| Asymmetric Hydrogenation | Chiral Auxiliary (Stoichiometric) | Ru-BINAP or Rh-DuPhos | <50% | ~100% | 60-80% | >99% ee (Common) |

| C-H Activation | Halogenation then Coupling | Pd⁰/Pd²⁺ with Directing Group | <40% | >85% | 70-90% | High Site-Selectivity |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Continuous Flow Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation for Chiral Amine Intermediate

This protocol details a scalable, catalytic method for synthesizing a chiral amine precursor, replacing a classical stoichiometric resolution process.

Objective: Synthesis of (S)-N-(1-phenylethyl)acetamide from acetophenone. Green Principle Application: Uses a catalytic amount of a chiral Ru(II) complex with formic acid as a safe, stoichiometric reductant.

Materials & Setup:

- Reactor: Packed-bed continuous flow reactor (10 mL volume).

- Catalyst: Immobilized [RuCl((S,S)-TsDPEN)(p-cymene)] on silica support (2 mol% loading relative to substrate flow).

- Substrate Solution: Acetophenone (1.0 M) and formic acid (5.0 M) in a 1:1 mixture of ethanol and water.

- Temperature Control: Oven set to 70°C.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Pack the flow reactor column with the immobilized Ru catalyst. Flush the system with pure ethanol for 10 minutes.

- Reaction: Pump the substrate solution through the catalyst bed at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min (Residence Time: ~100 min).

- Monitoring: Collect effluent and monitor conversion by ¹H-NMR (disappearance of ketone peak at ~2.5 ppm) and enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC (Chiralcel OD-H column).

- Work-up: Combine product fractions, evaporate solvent under reduced pressure, and recrystallize from heptane/ethyl acetate to yield the chiral amide. Typical yield: 92-95% with 98-99% ee.

Protocol: Photoredox-Catalyzed Late-Stage C-H Functionalization of a Complex Molecule

This protocol demonstrates a mild, selective C-H arylation using visible light catalysis, avoiding pre-functionalization steps.

Objective: Direct arylation of an N-methyl pyrrole moiety within a drug-like scaffold. Green Principle Application: Replaces a traditional two-step halogenation/Stille coupling sequence with a single catalytic step using light as a traceless reagent.

Materials & Setup:

- Photoreactor: Blue LEDs (450 nm, 30 W) arranged around a jacketed reaction vessel.

- Catalyst System: [Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy)]PF₆ (1 mol%), N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (2.0 equiv), Aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate salt (1.2 equiv).

- Solvent: Degassed acetonitrile (0.05 M concentration of substrate).

- Temperature: Maintained at 25°C via cooling jacket.

Procedure:

- Charge: In a dry, nitrogen-purged vial, combine the substrate (1.0 equiv), photoredox catalyst, and aryl diazonium salt. Add degassed acetonitrile and DIPEA.

- Irradiate: Place the vial in the photoreactor under vigorous stirring. Irradiate with blue LEDs for 18 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Monitor: Track reaction progress by LC-MS for consumption of starting material.

- Quench & Purify: Dilute the reaction mixture with dichloromethane and wash with saturated aqueous NaHCO₃ solution. Dry the organic layer over MgSO₄, filter, and concentrate. Purify by flash chromatography (SiO₂, gradient elution). Typical isolated yield: 65-80%.

Visualizing Catalytic Cycles and Workflows

Diagram 1: Generic Asymmetric Hydrogenation Catalytic Cycle

Diagram 2: Photoredox C-H Functionalization Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Catalytic Reagents for API Synthesis

| Reagent/Catalyst | Supplier Examples | Primary Function in API Synthesis | Green Chemistry Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd PEPPSI Precatalysts | Sigma-Aldrich, Strem | Robust, air-stable catalysts for Negishi, Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings. | Enable low catalyst loadings (<0.5 mol%), room temperature reactions, broad functional group tolerance. |

| Ru-Macho-BH | Aldrich, Takasago | Asymmetric hydrogenation catalyst for ketones and imines. | Delivers high enantioselectivity (>99% ee) under mild H₂ pressure, replacing stoichiometric chiral auxiliaries. |

| OrganoPhotocatalysts (4CzIPN) | TCI, Fluorochem | Metal-free, organic photocatalyst for energy transfer and single-electron transfer reactions. | Enables C-C/C-X bond formations using visible light, avoiding toxic heavy metals and harsh oxidants. |

| Immobilized CAL-B (Lipase) | Novozymes, Codexis | Biocatalyst for kinetic resolutions, esterifications, and aminolyses. | High selectivity in water or solvent-free systems; recyclable; operates under mild pH/temp. |

| Shvo's Catalyst | Strem, Umicore | Bifunctional catalyst for transfer hydrogenation and hydrogen auto-transfer reactions. | Uses benign hydrogen donors (e.g., iPrOH); enables borrowing hydrogen amination without stoichiometric reductants. |

| Organocatalyst (MacMillan type) | Enamine, Merck | Imidazolidinone catalysts for asymmetric Diels-Alder, α-alkylations. | Metal-free, often tolerant of water/air, low toxicity, derived from renewable amino acids. |

The strategic implementation of catalysis, as mandated by Green Chemistry's Principle 9, is no longer a niche pursuit but a foundational requirement for efficient and selective API synthesis. The transition from stoichiometric to catalytic methodologies—encompassing homogeneous, heterogeneous, bio-, and photocatalysis—directly addresses the core goals of the Anastas and Warner framework by drastically reducing waste, improving energy efficiency, and enabling simpler, safer synthetic routes. As the toolkit of catalytic solutions expands, their integration from discovery through to manufacturing represents the most viable path toward a sustainable and economically sound pharmaceutical industry.

The concept of "Benign by Design," championed by Paul Anastas and John Warner, is the philosophical cornerstone of modern green chemistry. Their 12 Principles provide a framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances. Principle 5, which advocates for the use of safer solvents and auxiliaries, is not merely a suggestion but a critical design imperative. This principle directly targets one of the largest contributors to the environmental footprint and toxicity profile of chemical manufacturing, particularly in pharmaceutical development where solvent mass can vastly exceed product mass. This guide translates Principle 5 into a practical, data-driven decision-making framework for researchers and process chemists, prioritizing human health and environmental integrity without compromising scientific efficacy.

The Hierarchy of Solvent Selection: A Practical Framework

An effective solvent selection strategy moves beyond simple substitution to a systematic evaluation. The following hierarchy should be applied sequentially.

Step 1: Solvent Elimination

The greenest solvent is no solvent. Consider:

- Mechanochemistry: Solvent-free grinding or ball-milling.

- Neat Reactions: Conducting reactions with reactants in a molten state.

- Solid-State Synthesis.

Step 2: Use of Innocuous or Benign Solvents

If a solvent is necessary, prioritize those with minimal health, safety, and environmental impact. Benign solvents are typically characterized by:

- High boiling point (>150°C) for safety or low boiling point for easy recovery.

- Low vapor pressure.

- Non-flammable or high flash point.

- Non-toxic, non-carcinogenic, non-mutagenic, non-teratogenic.

- Readily biodegradable.

- Not ozone-depleting.

- Derived from renewable feedstocks where possible.

Step 3: Minimization and Closed-Loop Recycling

When less-preferable solvents must be used, their volume must be minimized, and systems for efficient recovery and reuse must be integrated into the process design.

Quantitative Solvent Assessment & Selection Tables

Selection requires comparative data. The following tables summarize key metrics for common solvents, categorizing them based on the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Solvent Sustainability Guide and Pfizer's Green Chemistry Solvent Guide, which are industry standards derived from Anastas and Warner's principles.

Table 1: Preferred Green Solvents (Recommended for Use)

| Solvent | Boiling Point (°C) | GSK Score* | Key Advantages | Primary Concerns/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 100 | 10 | Nontoxic, nonflammable, inexpensive. | Poor solubility for many organics, hydrolysis risk, high heat capacity. |

| Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) | 106 | 9 | Excellent stability, low peroxide formation, forms azeotropes with water. | Can be more expensive than traditional ethers. |

| 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) | 80 | 8 | Derived from renewables, good solvent power, immiscible with water. | Can form peroxides; requires stabilization. |

| Ethyl Acetate | 77 | 8 | Readily biodegradable, low toxicity. | Flammable, can hydrolyze. |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | 82 | 8 | Low toxicity, readily available. | Flammable. |

| Acetone | 56 | 8 | Low toxicity, good solvent power. | Highly flammable, volatile. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | 90 | 8 | Biodegradable, low toxicity, versatile reagent. | Can be slow to react as a methylating agent. |

*GSK Score: A composite lifecycle score (1=worst, 10=best) assessing waste, environmental impact, health, and safety.

Table 2: Solvents to be Used with Justification and Caution

| Solvent | Boiling Point (°C) | GSK Score* | Justification for Limited Use | Required Controls/Mitigations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | 65 | 7 | Useful for SN2 reactions, recrystallization. | Highly flammable, toxic. Use in well-ventilated areas, minimize volumes. |

| Heptane | 98 | 7 | Aliphatic hydrocarbon with lower toxicity than hexane. | Flammable, environmental pollutant. Prioritize recovery. |

| Toluene | 111 | 6 | Excellent solvent for many reactions, high b.p. | Reproductive toxin, environmental hazard. Use only in closed systems. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | 66 | 5 | Excellent solvent for organometallics. | Forms explosive peroxides, flammable. Must be tested for peroxides, use stabilized grades. |

| Acetonitrile | 82 | 5 | High dielectric constant, useful for HPLC. | Toxic to aquatic life, energy-intensive production. Rigorous recycling is mandatory. |

Table 3: Undesirable Solvents (Avoid or Seek Alternative)

| Solvent | Boiling Point (°C) | GSK Score* | Primary Hazards | Common Green Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 153 | 4 | Reproductive toxicity, difficult to remove, poor biodegradability. | N-Butyronitrile, 2-MeTHF, Acetone/Water mixtures. |

| N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | 202 | 3 | Reproductive toxicity, high boiling point. | Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME), Dimethyl Isosorbide. |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | 40 | 3 | Carcinogenic suspect, ozone depletion potential (low), VOC. | 2-MeTHF, Ethyl Acetate, MTBE, CPME. |

| Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE) | 68 | 3 | Extremely prone to peroxide formation. | MTBE, CPME, 2-MeTHF. |

| Hexane(s) | 69 | 3 | Neurotoxic, highly flammable, environmental pollutant. | Heptane, Cyclohexane, 2-MeTHF. |

| Benzene | 80 | 1 | Known human carcinogen. | Toluene, Xylene (with caution), CPME. |

| Carbon Tetrachloride | 77 | 1 | Severe liver toxin, carcinogen, ozone depleter. | Avoid entirely. Use alternative chlorination methods. |

Detailed Protocols for Evaluating Solvent Greenness

Protocol 1: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Screening for Solvent Selection

Objective: To compare the cradle-to-grave environmental impact of two or more candidate solvents for a specific process. Materials: LCA software (e.g., SimaPro, GaBi) or databases (Ecoinvent, USLCI); process mass and energy data. Methodology:

- Define Goal & Scope: Specify the functional unit (e.g., "to dissolve 1 kg of API intermediate at 25°C").

- Inventory Analysis: Compile data on raw material extraction, synthesis, transportation, use-phase energy, and end-of-life treatment (incineration, recycling, biodegradation) for each solvent.

- Impact Assessment: Calculate impacts across categories: Global Warming Potential (GWP), Cumulative Energy Demand (CED), Human Toxicity Potential (HTP), Aquatic Ecotoxicity, and Photochemical Ozone Creation.

- Interpretation: Use the results to identify the solvent with the lowest overall environmental burden. This protocol provides the most comprehensive assessment aligned with the systems-thinking aspect of Anastas and Warner's thesis.

Protocol 2: Experimental Measurement of Solvent Biodegradability (Closed Bottle Test OECD 301D)

Objective: To determine the ready ultimate biodegradability of an organic solvent in an aqueous medium. Materials: Test solvent; mineral nutrient solution; activated sludge inoculum; BOD bottles; dissolved oxygen meter; biological oxygen demand (BOD) detection system. Methodology:

- Prepare bottles with a defined concentration of the test solvent (typically 2-10 mg/L of organic carbon) in mineral medium, inoculated with a small amount of pre-washed activated sludge.

- Prepare control bottles: without inoculum (abiotic control) and with a reference compound (sodium acetate).

- Seal bottles and incubate in the dark at 20°C for up to 28 days.

- Measure dissolved oxygen (DO) regularly. The biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) is the difference between DO in the abiotic control and the test vessel.

- Calculation: % Biodegradation = (BOD of test substance / Theoretical Oxygen Demand (ThOD)) x 100. A solvent achieving >60% degradation in 28 days is considered "readily biodegradable," a key green metric.

Protocol 3: Kamlet-Taft Solvatochromic Parameter Measurement

Objective: To quantitatively characterize the polarity, hydrogen-bond donor (HBD), and hydrogen-bond acceptor (HBA) ability of a solvent, enabling rational substitution. Materials: UV-Vis spectrophotometer; carefully dried solvent samples; solvatochromic probe dyes: Reichardt's Dye 30 (ET(30)), 4-nitroanisole, and N,N-diethyl-4-nitroaniline. Methodology:

- Prepare dilute solutions (~10^-4 M) of each probe dye in the solvent of interest.

- Record the UV-Vis absorption spectrum for each solution. Precisely determine the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax).

- Calculate Parameters:

- π* (Polarity/Polarizability): Derived from the shift of nitroanisole and nitroaniline probes.

- α (HBD Acidity): Calculated from ET(30) and the π* value.

- β (HBA Basicity): Derived from the shift of the nitroanisole probe.

- Compare the (π*, α, β) triplet of a hazardous solvent to databases to identify greener solvents with similar solvation properties, enabling a functionally equivalent but safer replacement.

Visualizing the Solvent Selection Workflow

Title: Green Solvent Selection Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Solvent Evaluation

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Solvent Greenness Assessment

| Item | Function in Evaluation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Reichardt's Dye 30 | Solvatochromic probe for measuring ET(30) and calculating solvent α (HBD acidity) parameter. | Must be kept dry; solutions are light-sensitive. |

| 4-Nitroanisole & N,N-Diethyl-4-nitroaniline | Probe pair for determining π* (polarity) and β (HBA basicity) Kamlet-Taft parameters. | Purity is critical for accurate λmax determination. |

| Activated Sludge Inoculum | Microbial community for biodegradability testing (OECD 301D). | Should be fresh, from a domestic wastewater plant, and pre-washed to remove residual carbon. |

| Sodium Acetate (Anhydrous) | Reference compound for biodegradability tests to validate inoculum activity. | Readily biodegradable standard; result is invalid if acetate fails. |

| Oxygen-Sensitive Test Strips | Rapid, qualitative detection of peroxide formation in ethers (e.g., THF, 2-MeTHF). | Essential for lab safety; does not replace quantitative titration for aged solvents. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) with Headspace Sampler | Quantifying residual solvent in APIs (per ICH Q3C guidelines) and monitoring solvent recovery purity. | Method must be validated for each solvent of interest. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measuring melting point depression to assess solvent suitability for crystallization/purification. | Can determine if a green solvent provides adequate solubility and crystal form control. |

Process Intensification and Continuous Flow for Waste Minimization (Principle 1)

The foundational work of Paul Anastas and John Warner established the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, a framework designed to reduce the environmental impact of chemical processes at the molecular level. Principle 1, "Waste Prevention," is paramount: it is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean it up after it is formed. This whitepaper explores the synergistic application of Process Intensification (PI) and Continuous Flow (CF) technology as a primary, modern strategy for actualizing this principle, particularly within pharmaceutical research and development. By integrating unit operations, enhancing mass/heat transfer, and moving from batch to continuous operation, these paradigms fundamentally redesign processes to minimize E-factor (kg waste/kg product) at the source.

Technical Deep Dive: Mechanisms of Intensification & Flow

Core Concepts and Quantitative Impact

Process Intensification aims to dramatically reduce the size of chemical plants while boosting production capacity. Continuous Flow chemistry executes reactions in narrow channels, offering superior control over reaction parameters. The combination delivers waste minimization through:

- Enhanced Mass & Heat Transfer: Micro/meso-scale channels enable rapid mixing and efficient temperature control, suppressing side reactions and improving selectivity/yield.

- Reduced Reaction Volumes: Smaller, dedicated flow reactors inherently generate less in-process inventory and hold-up waste.

- Integrated Synthesis & Purification: Inline workup, extraction, and purification (e.g., via membrane separations) prevent the accumulation of intermediary waste streams.

- Access to Novel Processing Windows: Safe operation at elevated temperatures and pressures unlocks more efficient reaction pathways with fewer steps.

- Precision and Reproducibility: Automated, consistent control minimizes failed batches and off-spec product, a significant source of waste.

The quantitative benefits are evident in comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Metrics: Batch vs. Continuous Flow Processes

| Metric | Traditional Batch Process | Intensified Continuous Flow Process | Impact on Waste (Principle 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical E-Factor (Pharma) | 25 - 100+ kg waste/kg API | 5 - 50 kg waste/kg API | >50% reduction common |

| Reaction Volume | 100s - 1000s L | 10s - 100s mL | Drastically reduces solvent use & inventory |

| Mixing Time Scale | Seconds to Minutes | Milliseconds to Seconds | Improves selectivity, reduces by-products |

| Temperature Control | Slower, gradients possible | Near-instant, isothermal | Suppresses decomposition pathways |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | High (Solvent dominates) | Lower (Reduced solvent, higher yield) | Direct measure of improved material efficiency |

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Flow Hydrogenation

Hydrogenations are high-risk batch operations often requiring dilution and generating waste. This protocol illustrates an intensified, continuous alternative.

Title: Continuous Flow Hydrogenation with Inline IR Monitoring and Quench

Objective: To catalytically reduce a nitroarene to an aniline with high conversion and minimal waste, using a packed-bed flow reactor.

Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate: Nitrobenzene (1.0 M solution in ethanol).

- Catalyst: Pd/Al₂O³ pellets (10% wt Pd, 100 µm mesh).

- Reductant: Hydrogen gas (H₂), 99.9%.

- Solvent: Anhydrous Ethanol.

- Quench Solution: Ethyl acetate for inline extraction.

- Reactor System: Pumps (Teflon or SS), mixing T-piece, stainless-steel tube reactor (1/8" OD, 10 mL volume) packed with catalyst, back-pressure regulator (BPR, 50 psi), inline FTIR flow cell, liquid-gas separator.

Procedure:

- Reactor Packing: The stainless-steel tube is dry-packed with Pd/Al₂O³ catalyst beads. Both ends are secured with porous metal frits (2 µm) to retain the catalyst.

- System Assembly & Purging: The reactor is installed in a flow system. Ethanol is pumped (1 mL/min) to wet the catalyst bed. H₂ gas is introduced via a mass flow controller (MFC) and merged with the liquid stream at a T-mixer prior to the reactor.

- Reaction Execution: The substrate solution (1.0 M) and H₂ gas are co-fed. Typical conditions: Liquid flow rate = 0.2 mL/min, Gas flow rate = 5 sccm (Standard Cubic Centimeters per Minute), Temperature = 80°C (via oil bath), System Pressure = 50 psi (maintained by BPR). The total residence time in the catalyst bed is ~5 minutes.

- Inline Analysis: The reactor effluent passes through a flow cell connected to an FTIR spectrometer. The disappearance of the NO² peak (~1520 cm⁻¹) and appearance of NH² peaks (~3450 cm⁻¹) are monitored in real-time.

- Inline Quench/Workup: The product stream is immediately merged with a stream of ethyl acetate (0.5 mL/min) and aqueous citric acid (10% wt, 0.5 mL/min) in a coiled flow mixer. The mixture passes through a membrane-based liquid-liquid separator. The organic phase (containing product aniline) is directed to collection, while the aqueous waste is isolated.

Analysis: The organic product stream is analyzed by GC-MS and NMR to determine conversion (>99%) and purity. The E-factor is calculated from the total mass of solvent, quench reagents, and catalyst used versus the mass of isolated aniline.

Continuous Flow Hydrogenation with Inline Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Flow Chemistry & Process Intensification

| Item | Function & Relevance to Waste Minimization |

|---|---|

| Peristaltic or HPLC Pumps | Provide precise, pulseless delivery of reagents. Minimizes overuse of materials and ensures stoichiometric accuracy, preventing excess reagent waste. |

| Microfluidic Chip Reactors (Glass/Si) | Enable ultra-fast mixing and heat exchange for high-speed screening. Allows optimization with microgram quantities, drastically reducing solvent and substrate waste during R&D. |

| Solid-Supported Reagents & Catalysts | Packed in cartridges or columns for inline use. Eliminates workup for catalyst removal, reduces metal leaching, and enables reagent recycling. |

| Tube-in-Tube Reactor (Gas-Liquid) | Semipermeable Teflon AF-2400 tube for efficient gas delivery (e.g., O², H², CO). Enables safe, efficient use of hazardous gases, improving atom economy and reducing headspace/venting losses. |

| Inline Analytical Probes (FTIR, UV) | Real-time reaction monitoring. Provides immediate feedback for control, preventing generation of off-spec material and allowing for dynamic optimization. |

| Membrane Separators | For continuous liquid-liquid or gas-liquid separation. Replaces bulk batch separation funnels, reducing solvent use for extraction and enabling closed-loop solvent recycling. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Maintains system pressure, keeping solvents/gases in solution at elevated temperatures. Allows use of superheated solvents, accelerating reactions and reducing processing time/material holdup. |

The strategic merger of Process Intensification and Continuous Flow technology provides a tangible, engineered path to fulfill Green Chemistry's first and most critical principle: Waste Minimization. By fundamentally rethinking process design from the ground up—prioritizing efficiency, integration, and control—researchers and development scientists can achieve dramatic reductions in E-factor and PMI. This aligns perfectly with the visionary framework of Anastas and Warner, moving sustainable chemistry from theory to standard practice. As these technologies become more accessible and integrated with automation and AI-driven optimization, their role as a cornerstone of green drug development will only solidify.

Within the framework of Paul Anastas and John Warner's Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, the pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a transformative shift towards sustainable synthesis. This whitepaper presents technical case studies of redesigned routes to commercial drugs, emphasizing waste reduction, hazard minimization, and energy efficiency. The principles of atom economy, benign solvents, and catalysis are central to these modern synthetic strategies.

Green Chemistry Principles & Pharmaceutical Metrics

The following table quantifies the improvements achieved through green chemistry route redesigns, aligned with Anastas and Warner's principles.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Greener Pharmaceutical Syntheses

| Drug (Company) | Original Route | Redesigned Green Route | Key Green Principle(s) | Impact (e.g., % Yield Increase, Waste Reduction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sertraline (Pfizer) | 3 linear steps, extensive TiCl4 reduction, large solvent volume. | Convergent 3-step process using benign ethanol solvent and catalytic hydrogenation. | #5 Safer Solvents, #9 Catalysis, #1 Waste Prevention | 97% reduction in solvent usage, 50% increase in overall yield, elimination of TiCl4. |

| Sitagliptin (Merck) | High-pressure asymmetric hydrogenation with rhodium catalyst, requiring separation of enantiomers. | Enzymatic transamination using a designed transaminase biocatalyst. | #6 Energy Efficiency, #9 Catalysis (Biocatalysis), #3 Less Hazardous Synthesis | 100% enantiomeric excess (ee), 10-13% increase in yield, 50% reduction in overall waste. |

| Pregabalin (Pfizer) | Resolution via diastereomeric salt formation, wasting 50% of undesired enantiomer. | Enzymatic asymmetric synthesis followed by a racemization-recycle process. | #2 Atom Economy, #8 Reduce Derivatives, #9 Catalysis | Atom economy improved from ~45% to ~85%, overall yield doubled, complete conversion of undesired enantiomer. |

| Montelukast (Merck & Codexis) | Stoichiometric use of hazardous reagents (e.g., borane). | Hybrid chemoenzymatic process with a redesigned ketoreductase enzyme. | #12 Inherently Safer Chemistry, #9 Catalysis | >99.5% ee, 99.9% pure product, 50% reduction in E-factor (mass waste per mass product). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Enzymatic Synthesis of Sitagliptin

Objective: Replace a high-pressure metal-catalyzed step with a stereoselective biocatalytic transamination. Methodology:

- Enzyme Engineering: A transaminase from Arthrobacter sp. was subjected to multiple rounds of directed evolution using error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling to improve activity against the bulky prositagliptin ketone substrate.

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable bioreactor, combine the prositagliptin ketone (200 mM) with isopropylamine (IPA, 1 M) as the amine donor. Add the engineered transaminase (3-5 mg/mL) and pyridoxal phosphate (PLP, 0.1 mM) as a cofactor in a 2:1 mixture of DMSO and 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5).

- Process Conditions: Maintain the reaction at 30°C with gentle agitation (200 rpm). Monitor conversion by HPLC.

- Work-up and Isolation: Upon completion (>99% conversion), separate the enzyme by filtration. The product, sitagliptin free base, is crystallized directly from the reaction mixture by pH adjustment and cooling. The yield and enantiomeric excess are determined by chiral HPLC.

Case Study 2: Greener Synthesis of Sertraline

Objective: Streamline synthesis and replace hazardous reagents (TiCl4) and solvents. Methodology:

- Catalytic Hydrogenation: Charge a pressure vessel with the tetralone imine intermediate (1.0 equiv) and 5% Pd/C catalyst (0.05 equiv Pd). Add absolute ethanol as the solvent (5 L/kg imine).

- Reaction Execution: Pressurize the vessel with hydrogen gas to 60 psi and heat to 50°C with stirring. Monitor hydrogen uptake until completion (typically 12-18 hours).

- Purification: Cool the reaction mixture, filter to remove the catalyst, and concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure. Crystallize sertraline free base from ethanol/water. The hydrochloride salt is formed by treating the free base with HCl in isopropanol.

Visualization of Green Chemistry Workflows

Diagram: Biocatalytic Synthesis of Sitagliptin

Diagram: Green Catalytic Hydrogenation for Sertraline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Green Pharmaceutical Route Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Chemistry | Example in Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Biocatalysts (e.g., Transaminases, Ketoreductases) | Enable highly selective, efficient, and mild transformations, replacing heavy metals and harsh conditions. | Codexis-engineered transaminase for Sitagliptin synthesis. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, supported metals) | Facilitate efficient catalytic hydrogenation; easily separable and recyclable, reducing metal waste. | Pd/C for the hydrogenation step in Sertraline synthesis. |

| Benign Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Water, 2-MeTHF, Cyrene) | Replace chlorinated and hazardous solvents (DCM, DMF, NMP) to reduce toxicity and environmental impact. | Ethanol as the sole solvent for Sertraline hydrogenation and crystallization. |

| Renewable Amine Donors (e.g., Isopropylamine) | Serve as efficient, often recyclable, nitrogen sources in biocatalytic aminations. | Isopropylamine (IPA) used in the transaminase reaction for Sitagliptin. |

| Pyridoxal Phosphate (PLP) | Essential cofactor for transaminase enzymes, required in catalytic (not stoichiometric) amounts. | Cofactor for the engineered transaminase in Sitagliptin synthesis. |

| Continuous Flow Reactor Systems | Enhance mass/heat transfer, improve safety with hazardous intermediates, and reduce solvent and energy use. | Enabling technology for safer handling of reactions in many modern route designs. |

The application of Anastas and Warner's principles through advanced catalysis, solvent substitution, and process intensification demonstrably leads to more sustainable, efficient, and economically viable pharmaceutical manufacturing. The continued integration of biocatalysis, flow chemistry, and continuous manufacturing promises to further green the lifecycle of drug production from research to commercial scale.

Overcoming Barriers: Troubleshooting Common Challenges in Green Chemistry Adoption

Balancing Green Metrics with Cost, Timeline, and Performance Requirements

The pursuit of sustainable pharmaceutical development necessitates a paradigm shift, one eloquently framed by the Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry established by Paul Anastas and John Warner. Their seminal research argues that environmental impact is not an external add-on but an intrinsic design criterion. This whitepates this philosophy into a practical technical guide for balancing core green metrics—such as Process Mass Intensity (PMI), E-Factor, and solvent selection scores—against the traditional triumvirate of cost, timeline, and performance (e.g., yield, purity) in drug development.

Foundational Green Metrics & Quantitative Benchmarks

Green metrics provide the quantitative backbone for objective decision-making. The following table summarizes key metrics, their calculation, and industry benchmarks derived from current literature and industry reports.

Table 1: Core Green Chemistry Metrics and Pharmaceutical Industry Benchmarks

| Metric | Formula | Ideal Target (Pharma) | Current Industry Average (API Manufacturing) | Primary Drivers for Improvement |