Headspace Extraction Gas Chromatography: Principles, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Headspace Extraction Gas Chromatography (HS-GC), a powerful technique for analyzing volatile compounds in complex solid and liquid matrices.

Headspace Extraction Gas Chromatography: Principles, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Headspace Extraction Gas Chromatography (HS-GC), a powerful technique for analyzing volatile compounds in complex solid and liquid matrices. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from equilibrium and the partition coefficient to modern instrumentation. The scope extends to detailed methodologies, key applications in pharmaceutical and clinical settings, practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and a comparative validation of different HS-GC techniques. By synthesizing theory with practical application, this guide serves as a vital resource for implementing and optimizing HS-GC in research and quality control workflows.

Understanding the Core Principles of Headspace Extraction

What is Headspace? Defining the Gas Phase Above a Sample

Headspace extraction is a sample preparation technique for gas chromatography (GC) that involves analyzing the volatile compounds present in the gas phase—the headspace—above a solid or liquid sample sealed in a vial [1] [2]. This approach is fundamental to analyzing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in complex matrices because it minimizes interference from non-volatile residues, simplifies sample preparation, and significantly reduces the introduction of non-volatile materials into the GC system, thereby extending column life and improving analytical reproducibility [1] [3].

The technique is built on a straightforward principle: a sample is placed in a sealed vial and heated to a specific temperature, allowing the volatile analytes to partition between the sample matrix and the gas phase above it [1]. After the system reaches equilibrium, a portion of the headspace gas is withdrawn and injected into the gas chromatograph for separation and detection [1] [4]. Its widespread adoption across pharmaceuticals, environmental science, food and beverage, and forensics is a testament to its reliability for determining volatile constituents, from residual solvents in drug products to flavors in food and ethanol in blood [1] [2].

Static vs. Dynamic Headspace Techniques

Headspace gas chromatography is primarily categorized into two distinct sampling methods: static and dynamic. Each method caters to specific analytical needs, predominantly differing in how the volatile analytes are transferred from the sample to the analytical instrument.

Table: Comparison of Static and Dynamic Headspace Techniques

| Feature | Static Headspace (SHS) | Dynamic Headspace (DHS/Purge & Trap) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Equilibrium-based sampling of the vapor in a closed vial [1] [4] | Non-equilibrium, exhaustive extraction by continuously purging the sample [1] [5] |

| Process | Sample is heated and equilibrated; an aliquot of the vapor is sampled [6] | Inert gas is bubbled through the sample, transferring volatiles to an adsorbent trap [1] [6] |

| Sensitivity | Parts per billion (ppb) to low percentage levels [1] | Generally lower detection limits than static; parts per trillion (ppt) possible [6] [5] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, robustness, minimal maintenance [1] [3] | High sensitivity, exhaustive extraction, pre-concentration on a trap [5] |

| Key Disadvantage | Limited sensitivity for very trace-level analytes [6] | More complex setup, requires more maintenance, potential for foaming [1] |

| Ideal For | Routine analysis of samples with relatively high volatility (e.g., residual solvents, blood alcohol) [1] [4] | Ultrapure water analysis, trace-level flavor and fragrance analysis, environmental contaminants [6] [5] |

A third technique, Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME), is also often grouped with headspace methods. SPME is a solvent-free technique that uses a fused-silica fiber coated with a stationary phase to extract analytes from the headspace or directly from a liquid sample [1]. The fiber is then thermally desorbed in the GC injector to introduce the analytes into the system [1].

The Scientific Principles of Headspace Analysis

The theoretical foundation of static headspace extraction is rooted in thermodynamic equilibrium and is a practical application of Henry's Law, which states that the vapor pressure of a solute is proportional to its concentration in the solution at equilibrium [6]. The entire process aims to establish a stable, reproducible state where the volatile compounds are distributed between the sample (liquid or solid) and the vapor phase [4] [2].

The Partition Coefficient (K) and Phase Ratio (β)

The distribution of an analyte between the two phases at equilibrium is described by the partition coefficient, K, defined as the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase to its concentration in the gas phase [3]: K = CS / CG A low K value signifies that the analyte has a higher tendency to reside in the gas phase, leading to a stronger detector signal [2]. The partition coefficient is highly dependent on temperature and the nature of the sample matrix [4] [3].

The phase ratio, β, is another critical parameter, defined as the ratio of the volume of the gas phase (VG) to the volume of the sample phase (VS) within the sealed vial [4] [2]: β = VG / VS

The relationship between the initial concentration of the analyte in the sample (C0), the partition coefficient (K), the phase ratio (β), and the resulting concentration in the gas phase (CG) is given by the fundamental headspace equation [4] [2]: CG = C0 / (K + β)

This equation is the cornerstone of headspace method development. To maximize the amount of analyte in the headspace (and thus the detector response), the sum of K + β must be minimized [2].

The Headspace Process Workflow

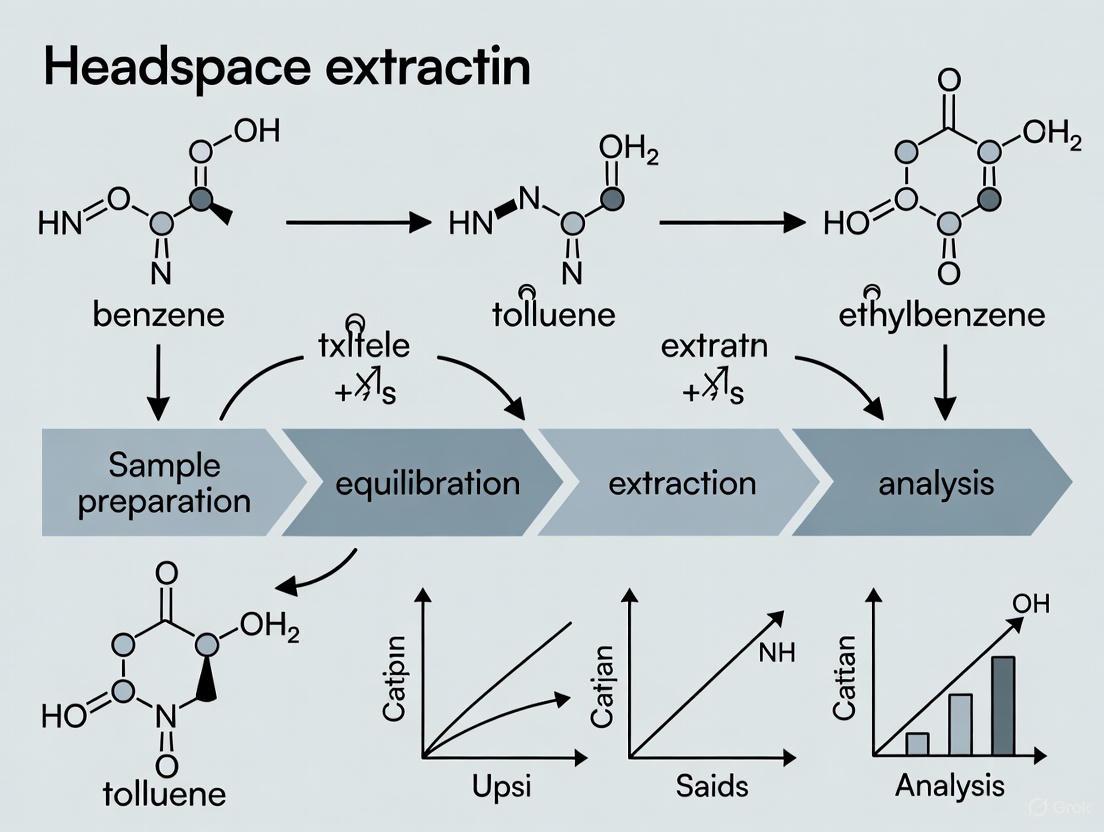

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key parameters that influence the equilibrium in a static headspace extraction process.

Diagram: Headspace Extraction Workflow and Key Parameters

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: Static Headspace-GC Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps for automated static headspace analysis using a valve-and-loop system, suitable for analyzing volatile compounds in liquid samples like residual solvents in pharmaceuticals [1] [2].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh or pipette a defined volume of the sample into a headspace vial. For liquid samples, this is typically 1-10 mL [6] [2].

- For quantitative analysis, add a suitable internal standard to the vial at this stage to correct for injection volume variability and matrix effects [6].

- Immediately cap the vial with a septum and a crimp or screw cap to ensure a tight seal and prevent loss of volatiles [2].

2. Equilibration:

- Place the sealed vial into the temperature-controlled oven of the headspace autosampler.

- The vial is heated and may be agitated for a predetermined time to accelerate the achievement of equilibrium. Common temperatures range from 60°C to 80°C, but this must be optimized and kept below the solvent's boiling point [6] [2]. Equilibration times can vary from a few minutes to over an hour [2].

3. Pressurization and Sampling:

- Once equilibrium is reached, the vial is pressurized with carrier gas [6] [2].

- The pressurized vapor is then vented through a heated sampling loop of fixed volume, filling the loop with the headspace sample [2].

- The flow path is switched, and the carrier gas sweeps the contents of the sample loop through a heated transfer line and into the GC inlet for analysis [2].

4. GC Analysis:

- The volatile compounds are separated on a GC column. A standard choice is a mid-polarity capillary column, such as a 30m x 0.32mm ID, 1.8µm film thickness DB-624, which is well-suited for volatile organics [6].

- Detection is commonly performed by Mass Spectrometry (MS) for identification and confirmation or by Flame Ionization Detection (FID) for quantification of organic compounds [1].

Key Experimental Parameters for Optimization

Robust and sensitive headspace analysis requires careful optimization of several key parameters.

Table: Key Method Parameters for Headspace Analysis Optimization

| Parameter | Influence on Analysis | Optimization Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibration Temperature | Increases vapor pressure of analytes, enriching the headspace. Higher temperature decreases K, increasing signal [4] [2]. | Increase temperature to maximize response, but stay ~20°C below solvent boiling point to avoid excessive pressure [2]. |

| Equilibration Time | Time required for the system to reach a stable equilibrium between the sample and gas phase [2]. | Determine experimentally by analyzing peak areas over time; area becomes constant at equilibrium [2]. |

| Sample Volume (Phase Ratio β) | Increasing sample volume in a fixed vial size decreases β, which can increase CG for analytes with low K [4] [2]. | Use at least 50% headspace in the vial. For volatile analytes (low K), use a larger sample volume to minimize β [2]. |

| Vial Pressure & Loop Fill Time | Affects the volume of headspace vapor transferred to the sample loop and subsequently to the GC [4]. | Ensure sufficient pressure and loop fill time for reproducible transfer. These are typically fixed in automated systems [2]. |

| Salting-Out Effect | Adding non-volatile salts (e.g., NaCl, Na₂SO₄) to aqueous samples decreases the solubility of organic analytes, reducing K and increasing their concentration in the headspace [2] [3]. | Experimentally determine the optimal salt type and concentration for your target analytes. |

Advanced Quantitative Technique: Multiple Headspace Extraction (MHE)

For complex solid matrices or when matrix-matched standards are impossible to prepare, Multiple Headspace Extraction (MHE) provides a solution for accurate quantification [7]. MHE is a stepwise gas extraction performed on the same sample vial [7].

- Principle: The first headspace analysis is performed as usual. After sampling, the headspace is removed, perturbing the equilibrium. The system is allowed to re-equilibrate, and a second, smaller headspace analysis is performed. This process is repeated several times, effectively stripping the analyte from the sample in an exponential decay [7].

- Quantification: The peak areas (A₁, A₂, A₃...) from the successive extractions are plotted against the extraction number on a semi-log scale. The total original amount of analyte is determined by extrapolating this linear decay back to time zero, which gives a total area independent of the sample matrix [7]. This technique eliminates the matrix effect, providing matrix-independent calibration [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful headspace analysis relies on the consistent quality of consumables and reagents. The following table details the essential items for a headspace laboratory.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Headspace-GC

| Item | Function / Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Containers for holding samples during incubation. Common sizes are 10 mL and 20 mL [2]. | Must be chemically inert and capable of withstanding pressure. Volume choice depends on required phase ratio (β) [2]. |

| Septa & Caps | Provide a gas-tight seal for the vial to prevent volatile loss before and during analysis [2]. | Septa must be thermally stable and non-absorbent. Use crimp caps for full security or torque-controlled screw caps [4]. |

| Internal Standards | Compounds added in a known concentration to the sample to correct for analytical variability [6]. | Must be a stable, volatile compound not present in the sample and with similar behavior to the analytes (e.g., deuterated analogs) [6]. |

| Salt Additives | Non-volatile salts like Sodium Chloride (NaCl) or Anhydrous Sodium Sulfate (Na₂SO₄) [3]. | Used to modify the matrix, "salting-out" organic analytes from aqueous solutions to improve volatility and sensitivity [3]. |

| Calibration Standards | Solutions of known concentration of the target analytes, used to build a calibration curve for quantification [6]. | Should be prepared in the same or a similar solvent as the sample. For MHE, standard solutions are submitted to the same MHE procedure [6] [7]. |

| Adsorbent Traps | Used in Dynamic Headspace (Purge & Trap); contain materials like Tenax TA, activated charcoal, or silica gel to trap purged volatiles [1] [5]. | Choice of adsorbent depends on the volatility and polarity of the target analytes. Multi-bed traps can handle a wider volatility range [5]. |

Headspace extraction gas chromatography is a powerful and versatile technique founded on well-established principles of equilibrium and volatility. By analyzing the gas phase above a sample, it offers a clean, robust, and often simple solution for determining volatile compounds in a vast array of complex matrices. A deep understanding of the core principles—the partition coefficient, phase ratio, and the factors affecting equilibrium—is essential for developing reliable methods. Whether using the straightforward static approach, the highly sensitive dynamic technique, or the advanced quantitative capability of Multiple Headspace Extraction, this methodology remains an indispensable tool in the modern analytical laboratory, playing a critical role in drug development, quality control, and scientific research.

Headspace Gas Chromatography (HS-GC) is a powerful sample introduction technique designed specifically for the analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in complex matrices. The core principle involves sampling the gas phase (the headspace) above a solid or liquid sample in a sealed vial rather than introducing the sample matrix directly into the chromatographic system [8] [9]. This method serves a dual critical purpose: it enables the accurate quantification of volatile target analytes while simultaneously protecting the sensitive GC instrument from non-volatile matrix components that could cause damage, contamination, or analytical interference. By avoiding the introduction of complex sample matrices such as polymers, blood, foods, or environmental solids directly into the GC inlet and column, HS-GC significantly reduces maintenance requirements, extends instrument uptime, and ensures data integrity and reproducibility [8].

The technique is particularly valuable when analyzing samples where the compounds of interest are volatile, but the sample matrix itself is either non-volatile or would be detrimental to the chromatographic system [8]. Common applications leveraging these protective benefits include residual solvent analysis in pharmaceuticals (USP method 467), blood alcohol testing, monitoring volatiles in environmental samples, and characterizing flavor compounds in foods and beverages [8].

Fundamental Principles of Headspace Extraction

The Equilibrium System

Static headspace analysis operates on the foundational principle of thermodynamic equilibrium established within a sealed vial. When a sample is heated in a sealed container, volatile compounds distribute themselves between the sample matrix (liquid or solid) and the inert gas phase (headspace) above it [10] [8]. At equilibrium, the rate of evaporation for each volatile component from the sample phase equals its rate of condensation from the gas phase back into the sample [10]. This equilibrium state is mathematically described by the partition coefficient (K), defined as K = C~S~/C~G~, where C~S~ is the concentration of the analyte in the sample phase and C~G~ is its concentration in the gas phase [8]. Compounds with low K values exhibit higher volatility and preferentially concentrate in the headspace, making them ideal candidates for HS-GC analysis.

The relationship between the initial sample concentration and the final detector response is governed by the equation: A ∝ C~G~ = C~0~/(K + β) [8]. In this equation, the chromatographic peak area (A) is proportional to the gas phase concentration (C~G~), which is determined by the original analyte concentration (C~0~) divided by the sum of its partition coefficient (K) and the phase ratio (β). The phase ratio (β) represents the relative volumes of the gas and sample phases within the vial (β = V~Gas~/V~Sample~) [8]. Successful method development focuses on optimizing conditions to minimize the combined value of (K + β), thereby maximizing the amount of analyte in the headspace and resulting in a strong detector signal.

Modes of Headspace Sampling

HS-GC analysis can be performed in two primary operational modes, each with distinct mechanisms and applications:

Static Headspace Sampling: This is an equilibrium-based technique where a single aliquot of the vapor phase is extracted from the sealed vial after equilibrium is reached and injected into the GC [10] [9]. The process involves three key steps: (1) sample equilibration at a controlled temperature, (2) pressurization and sampling of the headspace via a gas-tight syringe or valve-and-loop system, and (3) injection of the extracted vapor into the GC inlet [8] [9]. This mode is robust, simple, and provides excellent reproducibility for relatively abundant volatile analytes.

Dynamic Headspace Sampling: Also known as Purge and Trap, this is a non-equilibrium, exhaustive extraction technique. An inert gas continuously purges the sample, sweeping volatile compounds from the headspace onto an adsorbent trap [9]. This process displaces the equilibrium continuously, allowing for more complete transfer of volatiles from the sample. Once trapping is complete, the trap is heated to desorb the concentrated analytes directly into the GC [9]. Dynamic headspace offers significantly higher sensitivity than static methods and is preferred for trace-level analysis, but involves more complex instrumentation.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and decision process for implementing HS-GC:

Protective Mechanisms and Instrument Safeguarding

The design of headspace sampling systems incorporates multiple protective mechanisms that shield the sensitive and costly components of the gas chromatograph from potential damage.

The primary protection arises from the selective transfer of only volatile components into the GC system. Non-volatile matrix components, such as salts, proteins, polymers, and particulate matter, remain contained within the headspace vial and never enter the chromatographic inlet, column, or detector [8]. This prevents a range of potential issues including inlet contamination, column degradation, detector fouling, and the formation of non-volatile residues that would require frequent maintenance. Furthermore, since no or minimal organic solvent is introduced, the solvent peak is substantially reduced, minimizing the risk of it obscuring early-eluting analytes and reducing the overall chemical background [8].

Modern automated headspace samplers, such as Agilent's 7697A or SCION's HT3 series, incorporate heated transfer lines and thermostatically controlled valves that maintain the integrity of the volatile sample from the vial to the GC inlet, preventing premature condensation that could lead to system contamination [8] [9]. The Multiple Headspace Extraction (MHE) technique offers an additional layer of protection for complex matrices. By performing successive extractions from the same vial, it enables accurate quantitation without directly introducing the challenging sample matrix into the GC, even when matrix-matched calibration standards are difficult or impossible to prepare [8].

Table 1: How HS-GC Components Protect the Instrument

| GC Component Protected | Potential Threat | HS-GC Protective Mechanism | Resulting Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Inlet / Liner | Non-volatile residues, particulate matter | Selective transfer of only volatile analytes | Reduced contamination, longer liner lifetime, stable analyte response |

| Chromatographic Column | Matrix-induced degradation, active sites creation | Sample matrix never enters the column | Maintained column efficiency and resolution, extended column life |

| Detector (FID, MS, etc.) | Contamination, ion source fouling, burner clogging | Cleaner sample vapor without matrix interference | Stable baseline, consistent sensitivity, reduced downtime for cleaning |

| Overall System | Complex sample preparation errors, solvent effects | Minimal sample prep, reduced solvent introduction | Higher instrument uptime, better reproducibility, lower maintenance costs |

Quantitative Optimization and Experimental Design

Critical Method Parameters

Achieving optimal analytical performance in HS-GC requires the systematic optimization of several interdependent parameters that influence the partitioning of analytes into the headspace. A robust, statistically validated method must balance these factors to maximize sensitivity, precision, and throughput while maintaining the protective benefits for the instrument.

Equilibration Temperature: Temperature has a profound effect on the partition coefficient (K). Increasing temperature decreases K for most analytes, driving more analyte into the headspace and enhancing the detector signal [8]. As demonstrated in Figure 8 of the search results, a higher equilibration temperature for a constant time (20 minutes) resulted in a significantly higher detector response [8]. However, the temperature must remain approximately 20°C below the solvent boiling point to avoid excessive pressure and potential vial leakage [8]. Different compound classes also respond differently to temperature changes, making this a critical optimization parameter [10].

Equilibration Time: This is the duration required for the system to reach stable equilibrium between the sample and vapor phases. Insufficient time leads to poor reproducibility and low response, while excessively long times reduce analytical throughput without meaningful signal improvement. The optimal time is sample-dependent and must be determined experimentally [8].

Sample Volume and Phase Ratio (β): The phase ratio β = V~Gas~/V~Sample~ is a key geometric factor. For a given vial size, increasing the sample volume decreases β, which in turn increases the concentration of analyte in the headspace (C~G~) [11] [8]. A best practice is to fill no more than 50% of the vial volume to ensure adequate headspace for sampling [8]. Recent research using Central Composite Face-centered (CCF) experimental design identified sample volume as having the strongest negative impact on the response variable (peak area per μg), meaning larger volumes (smaller β) generally improve sensitivity [11].

Matrix Modification (Salting Out): The addition of non-volatile salts like ammonium sulfate or sodium chloride to aqueous samples increases ionic strength, which decreases the solubility of hydrophobic VOCs in water via the salting-out effect. This drives a greater proportion of analytes into the headspace phase, boosting sensitivity [10]. Agitation (shaking) of the vial during incubation can also accelerate the equilibration process, reducing the required time [8].

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for HS-GC Methods

| Parameter | Impact on Analysis | Optimization Guideline | Instrument Protection Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibration Temperature | Higher temperature increases volatile transfer to headspace; Too high may degrade sample | Set 20°C below solvent boiling point; Balance sensitivity and stability | Prevents vial over-pressurization and septum failure |

| Equilibration Time | Must be sufficient for equilibrium; Affects reproducibility | Determine experimentally; Use statistical design | Ensures consistent sampling pressure, protecting valve integrity |

| Sample Volume (Phase Ratio β) | Larger sample volume (smaller β) increases headspace concentration | Fill ≤50% of vial volume; Use larger vials (20-22 mL) for better sensitivity | Maintains consistent headspace pressure for reproducible injections |

| Salting Out (Ionic Strength) | Decreases analyte solubility in aqueous matrix, boosting headspace concentration | Use salts like sulfate, chloride; Optimize concentration | Salt remains in vial, preventing column and detector contamination |

| Agitation (Shaking) | Accelerates equilibrium attainment, reducing required time | Useful for viscous samples; Not always required | Reduces overall cycle time, decreasing instrument wear |

Statistical Optimization and Protocol

A 2025 study by Ruggieri et al. exemplifies a modern approach to HS-GC method development using a Central Composite Face-centered (CCF) experimental design to optimize the extraction of C5–C10 volatile petroleum hydrocarbons (VPHs) from aqueous matrices [11]. The researchers modeled the chromatographic peak area per microgram of analyte (Area per μg) as the response variable to objectively evaluate extraction efficiency.

The optimized protocol derived from such a statistical approach typically involves:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer a precisely measured volume of aqueous sample (e.g., 10-20 mL) into a headspace vial (e.g., 20 mL). Add an internal standard if required for quantification. Seal the vial immediately with a PTFE/silicone septum cap to prevent loss of volatiles [11] [8].

- Equilibration: Place the vial in the headspace sampler oven and incubate at the optimized temperature (e.g., 60-80°C for many VOCs) with optional agitation for a predetermined equilibration time (e.g., 15-30 minutes) [11].

- Pressurization and Injection: Pressurize the vial with carrier gas, then transfer an aliquot of the headspace vapor (e.g., 1 mL) to the GC inlet via a heated transfer line. The sample loop and transfer line temperatures are typically maintained 10-15°C above the oven temperature to prevent condensation [8].

- Chromatographic Separation: Analyze the extracted vapors using a GC equipped with a suitable capillary column (e.g., a mid-polarity stationary phase like RTX-200 for VOCs) and an appropriate detector—most commonly a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) or Mass Spectrometer (MS) [11] [12].

- System Cleanliness Maintenance: Following injection, the sample pathway (loop, transfer line) is purged with inert gas to remove any residual analytes, preventing carryover between samples and maintaining system integrity [9].

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) from the referenced study confirmed the global significance of the fitted model (R² = 88.86%, RMSE = 4.997, p < 0.0001), with significant main, quadratic, and interaction effects observed for the tested parameters [11]. This rigorous, statistically grounded approach ensures that the final method is not only highly sensitive but also robust and reproducible, fully leveraging the protective nature of HS-GC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of HS-GC requires specific consumables and reagents, each serving a distinct function in ensuring analytical accuracy and instrument protection.

Table 3: Essential Materials for HS-GC Analysis

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Containment of sample during equilibration | 10-22 mL capacity; Clear glass; Chemically inert |

| Crimp Caps & Septa | Hermetic sealing to prevent volatile loss | Aluminum caps with PTFE/silicone septa; Pre-slit for needle penetration |

| Internal Standards | Correction for injection volume variability and sample matrix effects | Deuterated or structural analog of analyte; Must be stable and volatile |

| Salt Additives (e.g., NaCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄) | "Salting out" to improve VOC partitioning from aqueous phases | High purity, non-volatile; Optimized concentration for specific matrix |

| Calibration Standards | Construction of quantitative calibration curves | Prepared in same/similar matrix or via standard addition method; Cover expected concentration range |

| Gas-Tight Syringes (Manual) | For method development checks or manual static sampling | Fixed volume; Blunt tip for septum penetration; Minimize dead volume |

Advanced Detection and Future Directions

While HS-GC with FID detection is a well-established workhorse, advanced detection technologies are expanding the capabilities of headspace analysis. The integration of micro-plasma ion sources (MPIS) with differential mobility spectrometers (DMS) represents a significant innovation for detecting volatile organic compounds [12]. This technology ionizes eluting VOCs using hydrated protons (H+(H₂O)~n~) produced in air at ambient pressure through atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) reactions, providing an additional dimension for VOC characterization alongside GC retention time [12]. Such non-radioactive ion sources are becoming attractive alternatives for field-deployable instruments, overcoming regulatory and safety concerns associated with traditional radioactive sources (e.g., ⁶³Ni) while maintaining sensitive, quantitative performance with detection limits reaching <10 pg for molecules with strong dipoles [12].

The convergence of optimized headspace sampling with these advanced detection technologies continues to strengthen the core principle of HS-GC: enabling the precise and sensitive analysis of volatile signatures from the most complex and challenging matrices while providing an indispensable protective barrier for the chromatographic instrumentation.

The Principle of Thermodynamic Equilibrium in a Sealed Vial

Within the broader discipline of headspace extraction gas chromatography (HS-GC) research, the principle of thermodynamic equilibrium in a sealed vial is the foundational concept that transforms this technique from a simple sampling method into a powerful, quantitative analytical tool. Headspace sampling is a premier sample introduction technique for gas chromatography, involving the analysis of the vapor layer above a sample in a sealed vial rather than the sample itself [13]. This approach is particularly advantageous for analyzing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in complex matrices such as solids, viscous liquids, blood, or medications where the sample itself may not be volatile or easily soluble in GC-appropriate solvents [13].

The attainment of thermodynamic equilibrium represents a critical juncture in the headspace process, where the system reaches a state of dynamic balance between the sample and vapor phases. Failing to achieve this equilibrium stands as the leading cause of reproducibility problems in analytical methods involving extraction, including static headspace extraction [4]. This technical guide examines the theoretical framework, experimental parameters, and practical implementations of this fundamental principle, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the comprehensive understanding necessary to optimize headspace methodologies for various applications, from pharmaceutical residual solvent analysis to environmental monitoring and flavor compound characterization [13].

Theoretical Foundation

The Fundamental Equilibrium

At the core of static headspace analysis lies a simple yet powerful phase-transfer equilibrium, governed by the partition coefficient. When a sample is placed in a sealed vial and heated, volatile compounds distribute themselves between the sample matrix (liquid or solid) and the vapor phase (headspace) above it [4] [9]. This equilibrium can be represented by the chemical equation:

[ \text{Analyte}{\text{(Sample Phase)}} \rightleftharpoons \text{Analyte}{\text{(Vapor Phase)}} ]

The extent to which an analyte partitions between the two phases is quantified by the partition coefficient (K), defined as:

[ K = \frac{CS}{CG} ]

Where (CS) is the concentration of the analyte in the sample phase and (CG) is the concentration in the gas phase [13]. A lower K value indicates higher volatility and greater preference for the gas phase, which is desirable in headspace analysis as it leads to higher detector response.

Mathematical Model of Headspace Sensitivity

The relationship between the initial sample concentration and the final detector response is mathematically described by the fundamental headspace equation [4] [13]:

[ A \propto CG = \frac{C0}{K + \beta} ]

Where:

- (A) = Peak area obtained at the detector

- (C_G) = Concentration of analyte in the gas phase

- (C_0) = Initial concentration of analyte in the sample

- (K) = Partition coefficient

- (\beta) = Phase ratio (ratio of vapor phase volume to sample phase volume)

This equation reveals that the detector response is proportional to the initial concentration of the analyte, divided by the sum of the partition coefficient and the phase ratio. To maximize detector response, conditions for K and β should be selected to minimize their sum, thereby increasing the proportional amount of volatile targets in the gas phase of the sample [13].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Headspace Thermodynamic Equilibrium

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Impact on Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partition Coefficient | K | Ratio of analyte concentration in sample phase to gas phase ((CS/CG)) | Lower K increases sensitivity |

| Phase Ratio | β | Ratio of vapor phase volume to sample phase volume ((VG/VS)) | Lower β increases sensitivity |

| Initial Concentration | (C_0) | Original concentration of analyte in the sample | Directly proportional to response |

| Equilibrium Constant | - | Position of solution-vapor equilibrium | Shift to vapor phase increases sensitivity |

Experimental Parameters and Optimization

Temperature Optimization

Temperature serves as the most critical parameter influencing the partition coefficient in headspace analysis. As temperature increases, the solution-vapor equilibrium shifts toward the vapor phase, effectively decreasing the partition coefficient and increasing the concentration of analyte in the headspace [4]. This relationship is demonstrated in chromatographic overlays where samples equilibrated at higher temperatures show significantly higher detector responses [13].

The effect of temperature on the partition coefficient follows an exponential relationship, with K values decreasing substantially as temperature increases. For example, the K value for ethanol in water decreases from approximately 1350 at 40°C to about 330 at 80°C [13]. However, temperature optimization must consider matrix effects and solvent properties. Strong solute-solvent interactions can reduce the impact of temperature on the partition coefficient, while non-polar solutes in polar solvents may experience enhanced vaporization due to repulsive matrix effects [4]. A critical limitation is that the maximum oven temperature should be maintained approximately 20°C below the solvent boiling point to prevent excessive solvent vaporization [13].

Phase Ratio and Sample Volume

The phase ratio (β) represents the relationship between the headspace volume and sample volume in the vial ((β = VG/VS)) and significantly impacts method sensitivity when its magnitude is comparable to the partition coefficient [4]. When K and β have similar orders of magnitude, which occurs with volatile analytes or weak matrix effects, the phase ratio substantially influences peak area, with larger phase ratios increasing the denominator in the fundamental equation and reducing detector response [4].

Best practice for optimizing phase ratio involves leaving at least 50% of the vial volume as headspace [13]. The impact of vial selection and sample volume is demonstrated in chromatographic overlays showing that the same 4-mL sample produces different responses when prepared in 10-mL versus 20-mL vials due to the different phase ratios [13]. When the partition coefficient is much larger than the phase ratio (as with low volatility analytes or strong matrix effects), the phase ratio has minimal effect on final peak area. Conversely, when K is very low compared to β (highly volatile analytes), the phase ratio dramatically impacts peak area, requiring extremely careful sample volume control to ensure reproducibility [4].

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Headspace Method Development

| Parameter | Optimization Principle | Practical Recommendation | Impact on Equilibrium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases vapor pressure; decreases K | Set 20°C below solvent boiling point; balance sensitivity with matrix effects | Exponential effect on K; major impact on equilibrium position |

| Sample Volume | Affects phase ratio (β) | Fill 50% of vial volume; use larger vials for larger samples | Critical when K ≈ β; minimal when K >> β |

| Equilibration Time | Must reach full equilibrium | Determine experimentally; typically 10-40 minutes | Essential for reproducibility; incomplete equilibrium causes major errors |

| Vial Pressure | Minor effect on K | Pressurize for consistent transfer | No effect on equilibrium position at constant volume |

| Agitation | Increases equilibration rate | Use shaking if available | Reduces equilibration time; no effect on final equilibrium |

Matrix Modification Techniques

The sample matrix profoundly influences the partition coefficient through chemical interactions between analytes and matrix components. Matrix modification represents a strategic approach to manipulate these interactions and improve method sensitivity. For liquid samples, solvent selection is crucial—choosing a solvent with weaker solvation capability for the analytes enhances their volatility [13]. Additionally, salt addition through the saturation of aqueous samples with non-volatile salts like sodium sulfate or potassium carbonate can significantly decrease analyte solubility through the "salting-out" effect, thereby reducing K and increasing headspace concentration [13]. For solid samples, the addition of a small amount of water or appropriate solvent can facilitate the release of volatile compounds by disrupting matrix-analyte interactions [13]. In cases of particularly complex matrices, multiple headspace extraction (MHE) techniques can be employed, which involve a series of sampling cycles from the same vial to improve quantitative accuracy [13].

Experimental Protocol for Equilibrium Method Development

Establishing Optimal Equilibration Conditions

Step-by-Step Methodology

Vial Preparation: Place a consistent sample volume into headspace vials, ensuring the vial size provides the desired phase ratio. Seal immediately with appropriate septa and crimp caps to prevent volatile loss [13]. Record exact sample weights and volumes for phase ratio calculation.

Temperature Gradient Study: Incubate sample replicates at different temperatures ranging from 40°C to 20°C below the solvent boiling point [13]. Maintain constant equilibration time (typically 20 minutes) and pressure conditions. Plot detector response versus temperature to identify the point where increased temperature no longer significantly improves sensitivity.

Equilibration Time Study: At the optimal temperature determined in step 2, conduct a time study with varying equilibration times (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 40, 60 minutes) [13]. Maintain all other parameters constant. Plot detector response versus time to identify the minimum equilibration time required to reach stable response.

Equilibrium Verification: Confirm equilibrium has been reached when consecutive time points show less than 5% relative standard deviation in peak areas for target analytes [4]. This stability indicates the system has reached dynamic equilibrium between the sample and vapor phases.

Method Validation: Validate the optimized method by assessing precision (typically <5% RSD), linearity (R² > 0.995), and detection limits to ensure the equilibrium conditions provide reproducible quantitative analysis [4].

Advanced Applications and Techniques

Multiple Headspace Extraction

For complex matrices where complete extraction is challenging or where matrix effects vary significantly between samples and standards, Multiple Headspace Extraction (MHE) provides a solution. This technique involves performing successive headspace extractions from the same vial, with each extraction removing a portion of the volatile compounds [13]. By analyzing the decay curve of peak areas over multiple extractions, the total analyte content can be determined through mathematical extrapolation, effectively eliminating matrix effects and improving quantitative accuracy [13].

Comparison of Static and Dynamic Headspace

While this guide focuses on static headspace extraction, understanding its relationship to dynamic headspace (purge and trap) provides valuable context for method selection. Static headspace is an equilibrium technique where the system reaches equilibrium before sampling, making it ideal for routine applications with analyte concentrations in the high part-per-billion range or higher [4]. In contrast, dynamic headspace continuously purges the sample with inert gas, transferring volatiles to a sorbent trap, providing exhaustive extraction rather than equilibrium-based sampling [9]. This approach typically offers greater sensitivity, enabling detection at part-per-trillion levels, but requires more complex instrumentation and longer analysis times [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Headspace Research

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Containment of sample during equilibration | 10-22 mL capacity; borosilicate glass; clear or amber | Larger vials allow greater sample volume or headspace; 50% headspace minimum recommended [13] |

| Septa & Caps | Maintain sealed system during heating | PTFE/silicone septa; aluminum or magnetic crimp caps | Must withstand temperature without leaking or introducing contaminants; proper seal critical [13] |

| Quantitative Standards | Normalization of analytical response | Certified reference materials; internal standards (e.g., deuterated analogs) | Should be chemically similar to analytes; must not interact with matrix; used for response normalization [4] |

| Salt Additives | Modify partition coefficient through salting-out | High purity NaCl, K₂CO₃, Na₂SO₄ | Decreases analyte solubility in aqueous matrices; increases headspace concentration; concentration must be optimized [13] |

| Heating Block/Oven | Temperature control for equilibration | Precision ±0.1°C; temperature range 40-150°C | Must provide stable, uniform heating; temperature accuracy critical for reproducible K values [13] |

| Gas-Tight Syringe | Manual sampling of headspace | Heated syringe; fixed or variable volume; lockable plunger | For manual systems; must maintain sample integrity during transfer to GC; temperature control prevents condensation [4] |

The principle of thermodynamic equilibrium in a sealed vial represents the theoretical cornerstone of static headspace gas chromatography, transforming it from a simple vapor sampling technique into a precise quantitative analytical methodology. Through careful manipulation of temperature, phase ratio, and matrix effects, researchers can optimize the partition coefficient to maximize sensitivity and reproducibility for diverse applications ranging from pharmaceutical residual solvent analysis to environmental monitoring and food flavor characterization. The mathematical relationship defined by the fundamental headspace equation provides a predictive framework for method development, while the experimental protocols outlined enable systematic optimization of critical parameters. As headspace technology continues to evolve, with advanced techniques like multiple headspace extraction addressing complex matrix challenges, the fundamental thermodynamic principles governing equilibrium in a sealed vial remain essential knowledge for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage this powerful sample preparation technique.

In the domain of chemical separations, the partition coefficient (K) is a fundamental thermodynamic parameter that quantifies the distribution of a solute between two immiscible phases at equilibrium [14]. This ratio is a critical comparison of the solubilities of the solute in the two liquids and serves as a direct measure of whether a chemical substance is hydrophilic ("water-loving") or hydrophobic ("water-fearing") [14]. Within the specific context of headspace extraction gas chromatography (HS-GC), the partition coefficient governs the transfer of volatile analytes from the sample matrix into the vapor phase (headspace) above it, thereby forming the very foundation of the analytical technique's operation and sensitivity [4] [15]. A deep understanding of this equilibrium is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to develop robust, sensitive, and reproducible methods for analyzing volatile compounds in complex matrices such as pharmaceuticals, biological fluids, and environmental samples [16] [15].

The partition coefficient, often designated as P or K for un-ionized species, is defined as the concentration of the solute in one phase divided by its concentration in a second phase [14]. In contrast, the distribution coefficient (D) refers to the concentration ratio of all species of the compound (both ionized and un-ionized) and is pH-dependent, making it particularly important for analytes that can undergo ionization in solution [14] [17]. For octanol-water systems, which are frequently used as a model for lipophilicity, the partition coefficient is expressed as log P [14]. The relationship between the partition coefficient (K), the concentration of analyte in the sample phase (C_S), and the concentration in the gas phase (C_G) is defined as K = C_S / C_G [15].

The Central Role of (K) in Headspace Extraction Gas Chromatography

Fundamental Principles of Static Headspace Extraction

Static headspace extraction (SHE) is a sample preparation technique that analyzes the volatile compounds present in the gas phase above a solid or liquid sample sealed in a vial [16] [4]. The process involves placing a sample in a sealed vial, heating it to a controlled temperature to allow volatile analytes to vaporize, and permitting the system to reach equilibrium between the sample and gas phases [16] [15]. Once equilibrium is established, an aliquot of the headspace gas is injected into the gas chromatograph for separation and analysis [16]. The mathematical expression that relates headspace concentration to GC detector response is fundamental to the technique [15]:

A ∝ CG = C0 / (K + β)

This equation demonstrates that the chromatographic peak area (A) is proportional to the analyte concentration in the gas phase of the vial (C_G). This concentration is defined by dividing the initial concentration of the analyte in the sample (C_0) by the sum of two sample-specific terms: the partition coefficient (K) and the phase ratio (β) [15]. To maximize detector response and therefore analytical sensitivity, conditions for K and β should be selected to minimize their sum, which increases the proportional amount of volatile targets in the gas phase of the sample [15].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental equilibrium established in a headspace vial and the subsequent transfer to the GC system:

Factors Influencing the Partition Coefficient in HS-GC

The partition coefficient K in headspace gas chromatography is influenced by several critical parameters that researchers must optimize for each specific application. The following table summarizes these key factors and their effects on the partition coefficient and overall analytical response:

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting the Partition Coefficient in Headspace GC

| Factor | Effect on Partition Coefficient (K) | Impact on Analytical Signal | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Inverse relationship; increasing temperature decreases K [4] [15] | Higher temperature increases signal by driving more analyte to vapor phase [15] | Keep approximately 20°C below solvent boiling point [15] |

| Matrix Composition | Strong solute-solvent interactions increase K, reducing volatility [4] | Strong matrix effects can reduce signal; salt addition or solvent choice can modify K [15] | Use minimal solvent for solid samples; add salt to aqueous samples to modify K [15] |

| Analyte Properties | Volatility and hydrophobicity directly affect K value [17] | More volatile compounds naturally yield stronger signals [16] | Compound-specific; must be determined experimentally [4] |

| Phase Ratio (β) | Independent of K but affects overall response A ∝ 1/(K+β) [15] | Smaller β (more sample volume) increases signal [15] | Leave at least 50% headspace in vial; use larger vials for better sensitivity [15] |

The temperature dependence of the partition coefficient is particularly significant in method development. As temperature increases, the partition coefficient decreases, meaning more analyte partitions into the headspace vapor phase, resulting in a higher detector response [4] [15]. For instance, the K value for ethanol in water decreases from approximately 1350 at 40°C to about 330 at 80°C, significantly enhancing sensitivity at higher temperatures [15]. However, there is a practical upper limit, as temperatures too close to the solvent boiling point can cause excessive solvent vaporization and potentially degrade analytes [15].

Matrix effects represent another crucial consideration. Strong intermolecular interactions between the analyte and sample matrix (such as hydrogen bonding or dipole-dipole interactions) can increase the partition coefficient, thereby reducing the amount of analyte available in the headspace [4]. This phenomenon explains why headspace analysis is particularly challenging for polar compounds in aqueous matrices. To overcome this, strategies such as salt addition (salting out) or pH adjustment (for ionizable compounds) can be employed to favorably modify the partition coefficient and improve sensitivity [15].

Experimental Methodology and Protocol Design

Establishing Equilibrium Conditions

The foundation of reproducible quantitative analysis in SHE is ensuring that the two-phase system in the vial has reached dynamic equilibrium between the solution and vapor phases before sampling [4]. Failure to achieve equilibrium is cited as the leading cause of reproducibility problems in analytical methods involving extraction [4]. The equilibrium state is influenced by temperature, sample volume, vial size, and the specific physicochemical properties of both the analyte and matrix [15].

To experimentally determine the optimal equilibration time, a series of vials containing identical samples should be prepared and equilibrated for different time intervals at a constant temperature [15]. Each vial is then analyzed, and the peak areas are plotted against equilibration time. The minimum time required to reach a plateau in the peak area response indicates the optimal equilibration time for that specific sample type and temperature [15]. Modern automated headspace instruments often include tools to help experimentally determine these optimal parameters [15].

Detailed Protocol for Static Headspace Analysis

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in a static headspace extraction protocol, from sample preparation to data analysis:

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol:

Sample Preparation: Precisely introduce the sample into a headspace vial. For liquid samples, this typically involves transferring a specific volume (0.5-5 mL, considering the phase ratio optimization). For solid samples, an exact weight is used. Immediately cap the vial with a septum and crimp seal to prevent loss of volatile compounds [15]. Vials are commonly available in 10-mL, 20-mL, and 22-mL capacities [15].

Equilibration: Place the sealed vial in the headspace sampler oven and incubate at a predetermined temperature for a specific time to establish equilibrium. Typical temperatures range from 40°C to 150°C, depending on the analyte volatility and solvent boiling point [15]. The equilibration time must be experimentally determined as described in Section 3.1 and can range from a few minutes to over 30 minutes [4].

Pressurization and Sampling: In automated valve-and-loop systems, the sampling process involves pressurizing the vial with carrier gas, then venting a portion of the pressurized headspace through a sample loop of fixed volume [15]. This ensures reproducible injection volumes.

Transfer and Analysis: The contents of the sample loop are transferred through a heated transfer line to the GC inlet [15]. The GC method then separates the analytes on an appropriate column, with detection typically performed by mass spectrometry (MS) or flame ionization detection (FID) [16].

Quantitation: Quantification is typically performed using external standard calibration, internal standard calibration, or standard addition methods. For complex matrices where creating matched calibration standards is challenging, Multiple Headspace Extraction (MHE) can be employed [15]. MHE involves performing several consecutive extractions from the same vial to determine the total extractable amount of analyte, improving accuracy when matrix effects vary significantly between samples and standards [15].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of headspace GC methodology requires specific reagents and materials optimized for volatile compound analysis. The following table details the essential components of the "Researcher's Toolkit" for headspace extraction:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Headspace GC

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | 10-mL, 20-mL, or 22-mL capacity; clear glass [15] | Larger vials allow for greater sample volume or headspace; must be sealable with septum and cap [15] |

| Septa & Caps | PTFE/silicone septa; aluminum or magnetic crimp caps [15] | Critical for maintaining a tight seal to prevent loss of volatile compounds during equilibration [15] |

| Internal Standards | Deuterated analogs of analytes or similar volatility compounds [4] | Correct for variability in sample preparation, injection, and matrix effects; must be non-interfering and behave similarly to analytes |

| Salt Additives | Anhydrous salts (e.g., NaCl, Na₂SO₄) for salting-out effect [15] | Added to aqueous samples to decrease solubility of organic analytes, reducing K and increasing headspace concentration [15] |

| Syringes | Gas-tight syringes for manual sampling [16] | Used in simple manual setups; must be heated to prevent condensation of volatiles [16] |

| GC Columns | Capillary columns with appropriate stationary phase [16] | Fused silica columns common; polarity selected based on analyte properties [16] |

| Calibration Standards | Pure analyte compounds for standard preparation [15] | Used to prepare calibration curves in appropriate solvent or matrix; purity must be verified |

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Headspace gas chromatography finds extensive application in pharmaceutical research and quality control, particularly for the analysis of residual solvents in drug substances and products [16]. The technique is ideal for this application because it minimizes the introduction of non-volatile sample components into the GC system, thereby reducing maintenance and extending column life [16]. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) method <467> is a standardized headspace procedure specifically designed to detect and measure Class 1, 2, and 3 solvents from pharmaceutical manufacturing, ensuring products meet regulatory guidelines for safety [15].

Beyond residual solvents, headspace GC is also employed in pharmaceutical development for analyzing volatile impurities, degradation products, and leachables from packaging [16]. The technique's ability to handle various sample matrices—including solids, viscous liquids, and complex formulations—with minimal sample preparation makes it particularly valuable in drug development workflows [15]. Furthermore, the application of headspace GC has expanded to cannabis product analysis, where it is used to monitor residual solvents in concentrates and extracts following the legalization of medical marijuana in many jurisdictions [15].

Headspace Gas Chromatography (HS-GC) is a cornerstone technique for analyzing volatile compounds in complex solid or liquid matrices, forming a critical research pillar in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to environmental science [18]. This technique specializes in sampling the vapor phase, or "headspace," above a sample sealed within a vial, thereby offering a clean analytical pathway with minimal interference from non-volatile sample components [19] [3]. The principle of headspace extraction leverages thermodynamics, where a sample is heated in a sealed vial to promote the volatilization of target analytes until equilibrium is established between the sample and the gas phase above it [18] [4]. Subsequent analysis of this headspace gas provides a robust and reproducible method for qualitative and quantitative analysis. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the essential hardware components that constitute a headspace gas chromatography system, tracing the analytical journey from the vial to the detector and framing it within the broader context of rigorous analytical research.

Core Principles of Headspace Extraction

At its core, static headspace extraction is an equilibrium technique governed by a straightforward chemical principle: when a sample is sealed and heated in a vial, volatile compounds distribute themselves between the sample matrix (liquid or solid) and the inert gas phase above it [4] [19]. The system is allowed to reach a state of dynamic equilibrium, where the rate of a compound evaporating from the sample equals the rate of its condensation back into the sample.

The fundamental relationship governing this process and the resulting detector response is expressed by the equation:

A ∝ CG = C0 / (K + β) [19]

Where:

- A is the peak area obtained from the GC detector.

- CG is the concentration of the analyte in the gas phase (headspace).

- C0 is the initial concentration of the analyte in the original sample.

- K is the partition coefficient, defined as the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase to its concentration in the gas phase (K = CS/CG) at equilibrium [4] [3].

- β is the phase ratio, which is the ratio of the volume of the gas phase to the volume of the sample phase (β = VG/VS) within the vial [4] [19].

The primary objective in headspace method development is to maximize CG, and therefore the detector response A, by minimizing the sum (K + β). This is achieved by optimizing factors such as temperature, which generally lowers K, and the sample volume, which lowers β [19].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key scientific principles involved in a static headspace extraction process.

System Components: A Stage-by-Stage Breakdown

A headspace gas chromatography system is an integrated instrument where each component plays a critical role in ensuring accurate and sensitive analysis. The journey of an analyte from the sample vial to its detection can be broken down into several key stages.

The analytical process begins with the proper preparation and containment of the sample.

- The Vial: Specially designed vials, typically with volumes of 10 mL, 20 mL, or 22 mL, are used to contain the sample [19]. These vials must be sealed airtight to prevent the loss of volatile analytes.

- Septa and Caps: High-quality septa and crimp or screw caps are essential to maintain the integrity of the closed system during heating and pressurization [4]. The septa must be chemically inert and resistant to the high temperatures used during incubation.

- Sample Preparation: A key advantage of HS-GC is minimal sample preparation. The sample, whether liquid or solid, is often placed directly into the vial. For liquid samples, techniques such as salt addition can be employed to decrease the solubility of analytes (reducing K) and enhance their presence in the headspace, a technique known as "salting-out" [19] [3].

The Headspace Sampler (Automatic)

Modern systems use automated headspace samplers to ensure high precision and reproducibility. Key components and steps include:

- Incubation Oven: The sealed vial is placed in a temperature-controlled oven where it is heated for a predetermined equilibration time. This heating accelerates the transfer of volatiles into the headspace and ensures the system reaches equilibrium [19].

- Pressurization Gas: An inert carrier gas (e.g., Helium or Nitrogen) is used to pressurize the vial after equilibrium is reached [19].

- Sampling Needle: A heated needle pierces the septum and, utilizing the vial's pressure, transfers an aliquot of the headspace vapor.

- Sample Loop & Transfer Line: The vapor is routed through a fixed-volume sample loop and then through a heated transfer line into the GC injector, preventing condensation of the analytes [19].

The following diagram details the typical workflow within an automated static headspace sampler.

Gas Chromatograph Components

Once introduced, the vapor sample undergoes separation within the gas chromatograph.

- Carrier Gas System: This consists of a high-purity gas source (Helium, Hydrogen, or Nitrogen), purification traps to remove contaminants, and precise flow controllers [18]. The choice of gas affects separation efficiency and analysis time; Hydrogen offers the fastest analysis, while Helium provides a good balance of safety and resolution [18].

- Injector/Inlet: The headspace vapor is introduced into the chromatographic system through a standard GC inlet, which is typically operated in split or splitless mode [4]. The entire pathway, from the sampler to the inlet, is kept hot to ensure the sample remains in the vapor phase.

- GC Column: This is the heart of the separation process. Capillary columns, made of fused silica and coated with a thin layer of stationary phase, are most common due to their high efficiency [18]. Analytes are separated based on their differing interactions with the stationary phase as they are carried through the column by the carrier gas.

Detection

After separation, analytes exit the column and enter the detector.

- Detector: The detector converts the physical presence of an analyte into an electronic signal, which is recorded as a peak in a chromatogram [18]. Various detectors are available, with the Mass Spectrometer (MS) being highly preferred for its ability to provide definitive identification and quantification of unknown compounds [18]. The Flame Ionization Detector (FID) is another widely used detector, particularly for the quantification of organic solvent residues [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful and reproducible HS-GC analysis relies on a suite of high-quality consumables and reagents. The following table details the essential components of a "Scientist's Toolkit" for headspace analysis.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HS-GC

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Contain the sample and maintain a closed system for equilibrium. | Available in 10, 20, and 22 mL volumes. Must be chemically inert and capable of withstanding pressure [19]. |

| Septa & Caps | Provide an airtight seal to prevent volatile loss. | Septa must be thermostable and non-absorbent. Caps (crimp or screw) must provide a uniform, secure seal [4]. |

| Liquid Standards | Used for instrument calibration and quantitative method development. | High-purity reference materials for target analytes. Required for creating external, internal, or standard addition calibration curves [20] [21]. |

| Internal Standards | Improve quantitative precision by correcting for injection variability and matrix effects. | A compound with similar properties to the analyte but not present in the sample (e.g., deuterated analogs) [21]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | A solvent-free alternative for extraction and concentration of volatiles. | A fused silica fiber coated with a stationary phase is exposed to the headspace. Useful for trace analysis [18] [22]. |

| Carrier & Purge Gases | Carrier gas moves analytes through the system; purge gas is used in sampler. | High-purity (≥99.999%) Helium, Nitrogen, or Hydrogen. Must be free of oxygen, hydrocarbons, and moisture [18] [19]. |

| Chemical Modifiers | Alter the sample matrix to improve analyte volatility. | Inorganic salts (e.g., NaCl) for "salting-out" or water for hydrating solid samples [19] [3]. |

Experimental Protocol for Residual Solvent Analysis

The following detailed methodology outlines the application of HS-GC for the analysis of residual solvents in a pharmaceutical product, a common application governed by standards such as USP method <467> [19].

Objective

To qualitatively identify and quantitatively determine the concentration of Class 1 and Class 2 residual solvents in a solid drug substance using static headspace gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (HS-GC-FID).

Materials and Equipment

- Automatic Static Headspace Sampler

- Gas Chromatograph equipped with FID

- Capillary GC column (e.g., 6% Cyanopropyl Phenyl / 94% Dimethyl Polysiloxane, 30 m x 0.32 mm ID, 1.8 µm film thickness)

- Headspace vials (20 mL), crimp caps, and septa

- Micropipettes and volumetric flasks

- High-purity water (or suitable solvent)

- Reference standards of target solvents (e.g., methanol, acetone, toluene, hexane)

- Internal standard (e.g., acetonitrile or 1-propanol)

Procedure

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Standard Solutions: Accurately weigh and dilute reference standards in a suitable solvent (e.g., water or DMF) to prepare a series of calibration standards covering the required concentration range (e.g., from 0.1 to 10 µg/mL).

- Internal Standard Solution: Add a consistent, known amount of internal standard to all calibration standards, quality control samples, and the actual sample solutions.

- Test Sample Solution: Precisely weigh approximately 100 mg of the solid drug substance into a headspace vial. Add 1.0 mL of the internal standard solution, immediately cap the vial, and vortex to mix or dissolve.

Step 2: Headspace Instrument Conditions

- Vial Oven Temperature: 80-110 °C (Optimize to maximize volatility without degrading the sample) [19]

- Loop Temperature: 110 °C

- Transfer Line Temperature: 120 °C

- Equilibration Time: 15-30 minutes (Determine experimentally by testing repeatability over time)

- Vial Pressurization: 15-20 psi (Carrier Gas)

- Pressurization Time: 0.5 - 1.0 minute

- Loop Fill Time: 0.1 - 0.2 minute

- Loop Equilibration Time: 0.1 minute

- Injection Time: 0.5 - 1.0 minute

Step 3: GC-FID Conditions

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow of 1.5 mL/min

- Injector: Split mode (split ratio 10:1), temperature 150 °C

- Oven Temperature Program:

- Initial: 40 °C (hold 5 min)

- Ramp: 10 °C/min to 200 °C

- Final: 200 °C (hold 2 min)

- Detector: FID at 250 °C

- Hydrogen flow: 30 mL/min

- Air flow: 300 mL/min

- Make-up flow (Nitrogen): 30 mL/min

Data Analysis and Quantitation

- System Suitability: The internal standard peak area in repeated injections of a standard should have a relative standard deviation (RSD) of ≤5.0%.

- Calibration: Plot the peak area ratio (Analyte / Internal Standard) against the concentration of the calibration standards. A linear regression model with a correlation coefficient (r²) of ≥0.995 is typically required.

- Quantitation: Calculate the concentration of each residual solvent in the test sample using the linear calibration equation. For methods without an internal standard, the external standard method is used, where the peak area of the analyte is directly compared to that of the standard [21].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Methods in Headspace GC

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Standard (ESTD) | Direct comparison of analyte peak area to a calibration curve from separate standard solutions. | Simplicity; useful when sample matrix is simple and consistent. | Susceptible to injection volume variability and matrix effects [21]. |

| Internal Standard (ISTD) | Comparison of analyte/IS peak area ratio to a calibration curve of standards containing the same IS. | Corrects for injection variability and minor instrument fluctuations; high precision. | Requires a suitable compound not in the sample; IS must behave similarly to analytes [21]. |

| Standard Addition (ASTD) | Addition of known amounts of analyte standard directly to the sample. | Eliminates matrix effects by performing calibration in the sample itself. | More complex and time-consuming; requires sufficient sample [21]. |

A comprehensive understanding of the essential components in a headspace gas chromatography system—from the vial to the detector—is fundamental to leveraging this powerful analytical technique effectively. Each component, governed by the principles of equilibrium and mass transfer, plays an integral role in the sensitivity, reproducibility, and accuracy of the analysis. For the researcher in drug development or other precision-focused fields, mastering the interplay between these hardware elements and the chemical principles of extraction is not merely operational necessity but the foundation for generating reliable, defensible, and meaningful scientific data.

HS-GC in Practice: Techniques and Key Applications in Biomedicine

Comparing Static vs. Dynamic (Purge and Trap) Headspace Techniques

Headspace sampling is a cornerstone sample introduction technique for gas chromatography (GC), specifically designed for the analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) present in solid or liquid samples with complex matrices [4]. The fundamental principle involves analyzing the vapor phase that exists in equilibrium above the sample material within a sealed vial, thereby providing instant clean-up by ensuring that only volatile materials are introduced into the GC system [6]. This technique represents a practical application of Henry's Law, which states that the vapor pressure of a solute is proportional to its concentration in a solution at equilibrium [6]. By measuring the concentration of an analyte in the vapor phase, its concentration in the original sample can be accurately determined through appropriate calibration, making it exceptionally valuable for analyzing samples containing non-volatile matrix components that could contaminate or damage the GC system [23].

The technique is particularly advantageous when dealing with complicated matrices such as industrial wastewaters, pharmaceuticals, food products, and environmental samples where numerous non-volatile contaminants may be present [6]. By analyzing only the vapor phase, headspace sampling significantly reduces the introduction of contaminants into the GC system, resulting in cleaner chromatograms and enhanced column longevity [23] [6]. Within this analytical framework, two primary methodological approaches have been established: static headspace extraction (SHE) and dynamic headspace extraction (DHE), commonly referred to as purge and trap. These techniques, while sharing the common goal of volatile compound analysis, differ fundamentally in their operational principles, sensitivity, and application suitability [23] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Background

Thermodynamic Foundations of Headspace Analysis

The theoretical foundation of headspace gas chromatography is rooted in phase equilibrium thermodynamics, where volatile compounds distribute themselves between the sample matrix (liquid or solid) and the vapor phase in the sealed vial [4]. This distribution is governed by the partition coefficient (K), defined as the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase (CS) to its concentration in the vapor phase (CV) at equilibrium: K = CS/CV [4]. The equilibrium constant expression for this process is analogous to mobile phase-stationary phase equilibria observed in chromatographic separations, with the partition coefficient playing a pivotal role in determining the mass of analyte transferred to the GC system for detection.

A critical relationship in static headspace analysis, as derived by Kolb and Ettre, connects the experimental conditions within the vial to the resulting analytical signal [4]. This relationship demonstrates that the peak area (A) obtained is proportional to the initial concentration of the analyte in the sample phase (C0) divided by the sum of the partition coefficient (K) and the phase ratio (β): A ∝ C0/(K + β) [4]. The phase ratio, defined as the volume of the vapor phase (VV) divided by the volume of the sample phase (VS) (β = VV/VS), typically ranges between 1-20 in most SHE methods and significantly influences method sensitivity, particularly for analytes with low partition coefficients [4].

Factors Influencing Headspace Sensitivity

Several critical parameters influence the equilibrium position and consequently the sensitivity of headspace analysis:

Temperature Effects: Elevated temperature increases the vapor pressure of analytes, shifting the equilibrium toward the vapor phase and enhancing the concentration in the headspace [4] [6]. However, temperature must be carefully controlled as excessive heat can vaporize the solvent matrix or degrade sensitive analytes, and typically operates at temperatures up to 80°C to avoid interference from water vapor [4] [6].

Matrix Effects: The chemical interactions between analytes and the sample matrix significantly influence volatilization [4]. Strong solute-solvent interactions can reduce the effect of temperature on the partition coefficient, while in cases where non-polar solutes are dissolved in polar solvents, matrix effects can actually enhance vaporization through a "salting-out" effect [4].

Phase Ratio Optimization: The relationship between the partition coefficient and phase ratio determines how significantly sample volume affects sensitivity [4]. When the partition coefficient and phase ratio have similar magnitudes, the phase ratio substantially impacts peak area, necessitating careful sample volume control [4].

Static Headspace Extraction (SHE)

Operational Principles of Static Headspace

Static headspace extraction operates as an equilibrium-based technique where the sample is placed in a sealed vial and allowed to reach equilibrium between the sample matrix and the vapor phase [23]. The vial is typically heated to a predetermined temperature to promote the release of volatile compounds from the sample matrix into the headspace [23] [4]. After a sufficient equilibration time, during which the volatile compounds partition between the sample and the headspace, an aliquot of the vapor phase is extracted from the vial and introduced into the GC system for analysis [23]. This sampling can be performed using a gas-tight syringe in manual systems or through an automated set of valves and transfer lines in instrumental configurations [4].

Modern automated static headspace systems function by heating and pressurizing the sealed vial with carrier gas in a thermostatically controlled oven [4]. Once equilibrium is established and the vial reaches the target pressure, a series of timed valves open to connect the pressurized vial to the GC inlet through a transfer line [4]. The pressurized headspace vapor expands into the transfer line and is carried into the chromatographic system for analysis [4]. The volume transferred is precisely controlled either by timing the flow reversal or through the use of a fixed-volume sample loop, ensuring analytical reproducibility [6].

Methodological Protocol for Static Headspace Analysis

A standardized protocol for static headspace analysis involves the following critical steps:

Sample Preparation: Accurately measure 5-10 mL of sample and seal it in a 20-25 mL headspace vial [6]. For quantitative analysis, internal standards may be added at this stage to correct for analytical variability [6].

Equilibration: Place the sealed vial in a thermostatted heater set at an appropriate temperature (typically 60-80°C) for a predetermined equilibration time (usually 5-20 minutes) [6]. Some systems may incorporate agitation to accelerate the equilibration process [6].

Pressurization: Pressurize the vial with carrier gas (helium or nitrogen) through a sampling needle that penetrates the septum [6].

Sample Transfer: After reaching the required pressure, reverse the gas flow for a fixed time or activate a sample loop to transfer the headspace vapor to the GC inlet [6].

Chromatographic Analysis: Initiate the GC program to separate and detect the volatile compounds transferred from the headspace sampler [23].

For method calibration, standard solutions of target analytes are prepared in a matrix resembling the sample and subjected to the exact same analytical procedure [6]. Consistency in treatment across all samples and standards is paramount, and reproducible results can be achieved even without reaching full equilibrium, provided that each sample is treated identically with respect to equilibration temperature and time [6].

Static Headspace Extraction Workflow

Dynamic Headspace Extraction (DHE) / Purge and Trap

Operational Principles of Dynamic Headspace