Industrial and Urban Heavy Metal Pollution: Sources, Health Impacts, and Advanced Mitigation Strategies

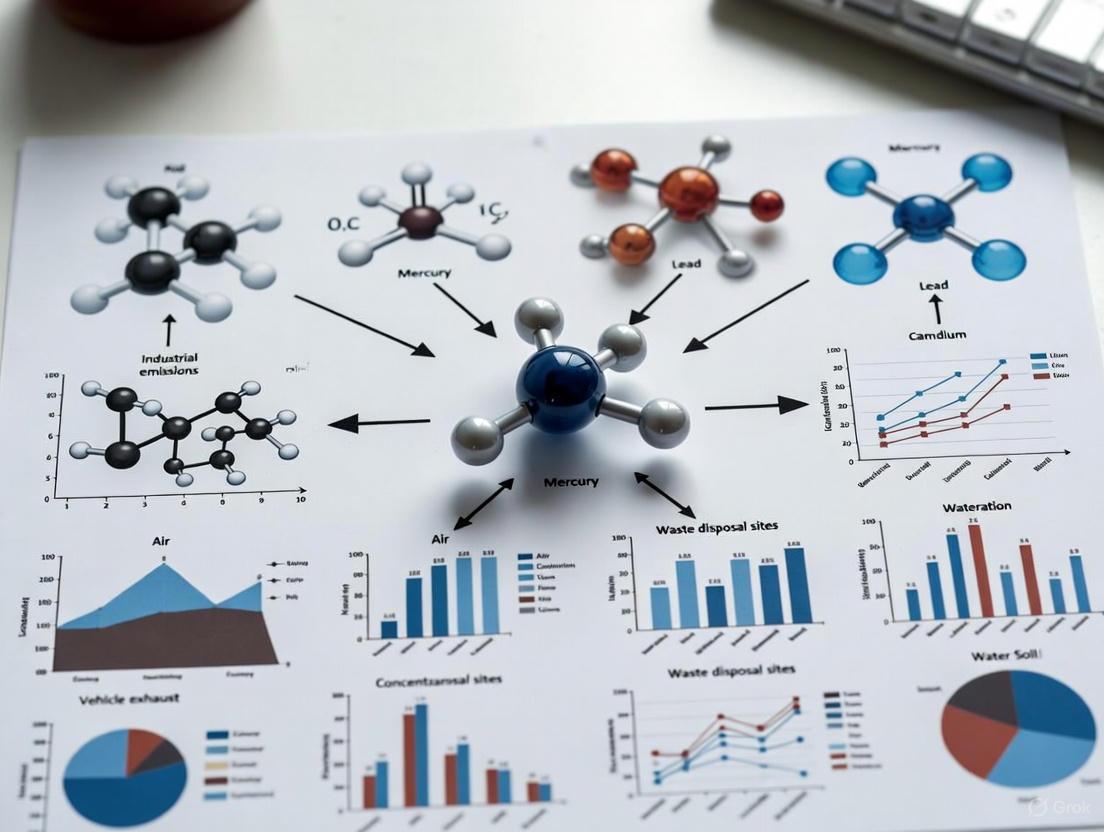

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of heavy metal pollution originating from industrial and urban activities, a critical environmental issue with direct implications for human health and ecosystem integrity.

Industrial and Urban Heavy Metal Pollution: Sources, Health Impacts, and Advanced Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of heavy metal pollution originating from industrial and urban activities, a critical environmental issue with direct implications for human health and ecosystem integrity. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it systematically explores the foundational sources and toxicological pathways of priority metals like Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), and Mercury (Hg). The scope extends to evaluating cutting-edge detection, monitoring, and bioremediation technologies, while addressing key challenges in field application and offering a comparative analysis of remediation efficacy. The synthesis aims to inform risk assessment models and illuminate the molecular mechanisms of metal-induced diseases, thereby supporting advancements in toxicological research and therapeutic development.

Uncovering the Sources and Toxic Pathways of Heavy Metals

Heavy metal contamination represents a critical environmental challenge intensified by global industrialization and urbanization. These toxic elements, known for their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity, pose significant threats to ecosystem integrity and public health. This technical guide synthesizes current research to define the priority pollutant profile of heavy metals from industrial and urban activities, providing a scientific foundation for targeted monitoring, risk assessment, and remediation strategies. The establishment of a clear pollutant profile is essential for researchers and environmental professionals developing effective interventions in contaminated systems.

Comprehensive analysis of contaminated sites worldwide has identified a consistent group of heavy metals as priority pollutants due to their prevalence, toxicity, and mobility. Research synthesizing data from 2014-2023 has established that cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and zinc (Zn) are the most frequently studied heavy metals at contaminated sites globally, indicating their prominent status as pollutants of concern [1].

Table 1: Priority Heavy Metals in Industrial and Urban Environments

| Heavy Metal | Primary Anthropogenic Sources | Pollution Ranking | Key Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | Battery manufacturing, industrial waste, phosphate fertilizers | 1 (Geo-accumulation Index: 5.91) | High ecological risk, carcinogenicity, bioaccumulation |

| Lead (Pb) | Lead-based paints, gasoline, mobile batteries, smelting | 2 (Geo-accumulation Index: 4.12) | Neurotoxicity, especially harmful to children |

| Zinc (Zn) | Industrial emissions, galvanized products, traffic emissions | 3 (Geo-accumulation Index: 3.73) | Indicator of industrial and traffic pollution |

| Copper (Cu) | Traffic emissions (brake wear), industrial processing, construction | 4 (Geo-accumulation Index: 2.37) | Mixed agricultural and transportation sources |

| Chromium (Cr) | Leather tanning, textile manufacturing, pulp processing | 5 (Geo-accumulation Index: 1.85) | Carcinogenicity (especially Cr-VI), industrial origin |

| Nickel (Ni) | Crude oil refining, metal alloys, industrial emissions | 6 (Geo-accumulation Index: 1.34) | Natural and industrial sources, respiratory risks |

| Mercury (Hg) | Coal combustion, electrical equipment, atmospheric deposition | Not ranked in above study | Atmospheric deposition, neurological toxicity |

| Arsenic (As) | Smelting activities, wood preservatives, pesticides | Not ranked in above study | Carcinogenicity, smelting and industrial sources |

Source: Adapted from global bibliometric analysis of contaminated sites [1] and integrated multi-model approaches [2].

The geo-accumulation indices presented in Table 1 provide a quantitative measure of heavy metal pollution in soils, with cadmium demonstrating the highest contamination level globally [1]. Source apportionment studies reveal distinct origin patterns, with approximately 30% of heavy metals deriving from natural sources (Ni, Cr), 29.5% from mixed agricultural and transportation sources (Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn), 19.4% from metal smelting activities (As), and 21.1% from atmospheric deposition sources (Hg) [2]. This distribution underscores the significant anthropogenic contribution to heavy metal pollution profiles.

Analytical Methodologies for Heavy Metal Characterization

Accurate characterization of heavy metal pollutants requires sophisticated analytical techniques capable of detecting trace concentrations in complex environmental matrices. The selection of methodology depends on required detection limits, sample matrix, analytical throughput needs, and available instrumentation.

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection and Quantification

| Analytical Technique | Detection Range | Sample Matrix | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) to parts-per-billion (ppb) | Water, soil, air, food, biological samples | Trace metal analysis, elemental speciation | High sensitivity, multi-element capability, requires specialized operation |

| Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (GFAAS) | Parts-per-billion (ppb) | Water, biological samples (blood, urine) | Lead and mercury in clinical samples | High sensitivity for specific elements, lower throughput than ICP-MS |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) | Parts-per-billion (ppb) | Industrial, environmental samples | Multi-element analysis, high-throughput screening | Cost-effective for routine monitoring, less sensitive than ICP-MS |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy | Parts-per-million (ppm) | Soils, sediments, construction materials | Rapid field screening, non-destructive analysis | Portable options available, minimal sample preparation |

| Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (CVAAS) | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) to parts-per-billion (ppb) | Water, air, biological tissues | Specific for mercury detection | Highly sensitive for mercury, specialized application |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Parts-per-billion (ppb) | Water, food samples | Lead and cadmium detection in field settings | Portable, cost-effective for specific metals |

Source: Adapted from analytical methodology reviews [3] and industrial monitoring guidelines [4].

Standardized Experimental Protocol for Soil and Dust Analysis

The following detailed methodology represents the current standard approach for comprehensive heavy metal analysis in urban and industrial soil and dust samples, as implemented in multiple recent studies [5] [6]:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Site Selection: Strategically select sampling points across target areas (industrial, residential, peri-urban) based on land use patterns and potential pollution sources.

- Composite Sampling: Collect approximately 500g of surface soil or street dust from 1m² areas using nylon brushes and dustpans, avoiding contamination from sampling equipment.

- Sample Drying: Air-dry samples for one week at ambient temperature or use oven drying at low temperature (≤40°C) to prevent volatile metal loss.

- Sieving and Homogenization: Pass samples through a 2.0mm nylon mesh sieve to remove debris and stones. Further separate into particle size fractions (e.g., ≤20μm and 20-32μm) using a vibratory sieve shaker (e.g., Retsch AS 200) set to amplitude of 60 for 20 minutes to isolate respirable fractions.

Sample Digestion and Extraction:

- Digestion Protocol: Transfer 50mg of homogenized sample into 100mL conical flasks. Add 20mL aqua regia (5mL 63% HNO₃ + 15mL 36% HCl) to each flask.

- Heating Process: Heat samples on a hot plate for 90 minutes at 150°C until reddish-brown fumes cease evolving.

- Concentration and Dilution: Reduce digest volume to approximately 1mL by evaporation. Cool to room temperature and dilute to final volume of 20mL with 2% nitric acid.

- Filtration: Filter samples using Whatman filter paper (or equivalent) to remove particulate matter.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Analysis by ICP-MS: Introduce digested samples to ICP-MS system following manufacturer calibration protocols. Use internal standards (e.g., Indium, Rhodium) to correct for matrix effects and instrument drift.

- Quality Control: Include method blanks, certified reference materials (CRMs), and duplicate samples in each analytical batch to ensure accuracy and precision. Maintain calibration curves with R² ≥ 0.999.

- Data Validation: Verify recovery rates for CRMs (85-115% acceptable range) and monitor duplicate sample precision (<15% relative percent difference).

This comprehensive protocol ensures reliable quantification of heavy metal concentrations across various environmental matrices, enabling accurate pollution assessment and source apportionment.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of heavy metal pollutants requires specific research reagents and analytical materials designed for precise quantification and characterization. The following toolkit outlines essential solutions and their applications in heavy metal research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Heavy Metal Analysis

| Research Reagent | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua Regia | 1:3 ratio of HNO₃ (63%) to HCl (36%) | Complete digestion of soil/dust samples for total metal extraction | Sample preparation for ICP-MS, ICP-OES analysis |

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | Multi-element certified reference solutions | Instrument calibration and quantification | Establishment of calibration curves for accurate measurement |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Matrix-matched certified materials (soil, sediment) | Quality control and method validation | Verification of analytical accuracy and precision |

| Microwave Digestion Vessels | Teflon/PFA digestion vessels | Closed-vessel sample digestion | High-temperature, high-pressure sample digestion |

| Isotopic Dilution Tracers | Enriched stable isotopes (e.g., ⁶⁵Cu, ¹¹¹Cd, ²⁰⁸Pb) | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Improved accuracy by correcting for matrix effects and instrument drift |

| Matrix Modification Reagents | NH₄H₂PO₄, Mg(NO₃)₂, Pd compounds | Modification of sample matrix in GFAAS | Reduction of interferences, improved volatility control in GFAAS |

| Chelating Agents for Speciation | EDTA, DTPA, sodium diethyldithiocarbamate | Selective complexation of specific metal species | Metal speciation studies, fractionation analysis |

| pH Adjustment Buffers | Ammonium acetate, nitric acid, sodium hydroxide | Control of solution pH for extraction | Bioavailable metal fraction extraction, sequential extraction procedures |

Source: Compiled from analytical methodologies [3] [4] and experimental protocols [5] [6].

Health and Ecological Risk Implications

Comprehensive risk assessment of priority heavy metals reveals significant concerns for both ecosystem integrity and public health. Ecological risk evaluations demonstrate that cadmium and mercury pose the highest ecological threats, with source-specific analysis indicating that mixed agriculture/transportation sources (37.6%) and atmospheric deposition (37.9%) contribute most significantly to ecological risk [2].

Human health risk assessments indicate particularly concerning patterns for vulnerable populations. Studies of urban and peri-urban agricultural soils show unacceptable health risks for children, with non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risk probabilities reaching 4% and 10%, respectively [2]. Source-apportioned health risks reveal that metal smelting activities contribute most significantly to non-carcinogenic risk (30.4%), while mixed agriculture and transportation sources are the leading contributors to carcinogenic risk (42.7%) [2].

Chromium, particularly in its hexavalent form [Cr(VI)], presents significant carcinogenic risks through inhalation exposure. Risk assessments in industrial areas of Bangladesh indicate that Cr poses the highest cancer risk via inhalation, with values reaching 1.13×10⁻⁴ to 5.96×10⁻⁴, falling within the threshold level of concern (10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶) [6]. Children are particularly vulnerable to heavy metal exposure, with studies of dust ingestion hazards indicating that children between birth and 6 years are at highest risk, with thallium, arsenic, lead, cobalt and chromium contributing most significantly to estimated hazards [7].

Remediation Approaches for Priority Heavy Metals

Addressing contamination from priority heavy metals requires targeted remediation strategies based on metal speciation, concentration, and site characteristics. Research indicates that the most frequently utilized remediation technologies globally include phytoremediation, soil washing, and microbial remediation [1].

For specific priority metals, remediation effectiveness varies significantly:

- Cadmium, Lead, Zinc: Phytoremediation and soil washing are the most effective technologies for removal [1].

- Lead: Solidification/stabilization techniques are commonly employed due to lead's tendency to form insoluble compounds that reduce mobility and bioavailability [1].

- Multiple Metals: Enhanced phytoextraction and chemical stabilization using soil conditioners like biochar have demonstrated effectiveness for multi-metal contamination [8]. Biochar influences soil pH and increases soil organic matter, which expands surface area for metal adsorption and promotes microbial activities that facilitate remediation [8].

Emerging approaches include nanotechnology-enhanced detection systems and artificial intelligence applications for predicting contamination patterns and optimizing remediation strategies [8]. The integration of AI with advanced sensor technologies shows particular promise for revolutionizing detection and management approaches for heavy metal contamination.

The pollutant profile of heavy metals from industrial and urban settings reveals a consistent pattern of priority metals—Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu, Hg, and As—with distinct source allocations and risk implications. Cadmium emerges as the highest priority pollutant globally, demonstrating both the highest geo-accumulation index and significant contribution to ecological and human health risks. The integration of advanced analytical methodologies with comprehensive risk assessment frameworks provides researchers with robust tools for characterizing and mitigating heavy metal contamination. Future research directions should focus on enhanced remediation technologies, particularly for mixed contamination scenarios, and the development of integrated monitoring systems leveraging AI and sensor technologies to better predict and manage the evolving profile of heavy metal pollutants in increasingly urbanized environments.

Anthropogenic activities are a primary driver of heavy metal contamination, releasing persistent and toxic pollutants that threaten ecosystem stability and public health. These metals, including lead (Pb), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg), are characterized by their environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and high toxicity even at trace concentrations [8]. Mining, smelting, industrial manufacturing, and urban runoff represent significant hotspots for the emission and mobilization of these contaminants. Understanding the specific profiles, transport mechanisms, and transformative pathways of heavy metals from these sources is crucial for developing targeted remediation strategies and informing regulatory frameworks. This technical guide synthesizes current research to provide a comprehensive overview of heavy metal pollution from these key anthropogenic sectors, offering structured data, standardized methodologies, and visual tools for researchers and environmental professionals.

The environmental impact of heavy metals is intrinsically linked to their emission concentrations and spatial characteristics. The quantitative data presented in this section provides a foundation for comparative risk assessment and prioritization of remediation efforts.

Table 1: Heavy Metal Concentration Ranges in Soils from Mining and Smelting Areas

| Metal | Typical Concentration Range (mg·kg⁻¹) | Primary Anthropogenic Source | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sb | Mean: 125.61 (~50x background) | Sb mining | Pronounced spatial variability (CV = 246.97%); co-contamination with As, Cd, Pb. | [9] |

| As | Up to 35,000 | Pb-Zn mining | Predominant pollutant in northern China Pb-Zn mine; spatial dispersion up to 2.0 km. | [10] |

| Pb | Up to 12,000; Mean: 49.9 | Pb-Zn mining & smelting | Similar dispersion pattern to As and Zn, influenced by wind-driven transport. | [10] |

| Zn | Up to 10,000; Mean: 109.5 | Zn smelting | Historical smelting emitted >1700 t Zn, creating heavily contaminated area. | [10] [8] |

| Cd | Up to 59; Mean: 0.27 | Zn/Pb/Cu mining by-product | High ecological risk probability (94.43%); toxic to plants, animals, and humans. | [9] [10] |

Table 2: Heavy Metal Emissions from Industrial and Urban Sources

| Metal | Source Type | Concentration / Emission Data | Particle Size Characteristics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe & HMs (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn) | Industrial Activities (13 categories) | Annual atmospheric release: Fe: 51,161 t; Heavy Metals: 69,591 t | PM₂.₅: 97.9% (average); PM₁: 79.0% (average) | [11] |

| Pb | Urban Stormwater Runoff | Range: 3.53-514.0 ppb (avg); Max: 686.5 ppb | Primarily associated with particulate matter; highest in flooded alleys. | [12] |

| Hg | Urban Stormwater Runoff | Range: 6.12-8.27 ppb (avg) | Exceeded EPA safe drinking levels at all sampled locations. | [12] |

| Cu, Zn | Traffic Area Runoff | Highest concentrations in runoff | Abundant in particulate form; finer RDS fractions have higher metal loads. | [13] |

Source-Specific Mechanisms and Environmental Pathways

Mining and Smelting

Mining and smelting operations represent some of the most severe and long-lasting point sources for heavy metal pollution. The environmental impact is driven by both the scale of emissions and the diversity of metals released.

- Geochemical Context and Co-contamination: In a typical Sb mining area in southwestern China, the mean soil Sb concentration was found to be 125.61 mg·kg⁻¹, nearly 50 times the regional background value. This contamination exhibited pronounced spatial variability (CV = 246.97%), indicative of complex dispersion patterns [9]. Sb mining rarely occurs in isolation, leading to frequent co-contamination with As, Cd, Pb, and Cr, which complicates remediation efforts [9] [14].

- Quantitative Source Apportionment: Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) analysis in the aforementioned Sb mining area revealed three major sources: industrial point sources (33.1%), regional mixed sources (36.8%), and natural geological sources (30.1%). This quantitative apportionment is critical for targeting remediation [9].

- Wind-Driven Transport: In arid and semi-arid regions, wind-mediated transport is a primary mechanism for metal dispersion from mining sites. Studies of a Pb-Zn mining area in northern China demonstrated similar dispersion patterns for As, Cd, Pb, and Zn, with contamination extending up to 2.0 km from source areas [10].

- Smelting Emissions and Crystalline Compounds: Industrial smelting releases fine particulate matter (PM) laden with heavy metals. Analysis of 118 industrial plants showed that 97.9% of emitted PM had diameters <2.5 μm (PM₂.₅), with 79.0% below 1 μm (PM₁), enhancing their atmospheric longevity and inhalation risks [11]. Specific crystalline compounds such as ZnO, PbSO₄, Mn₃O₄, Fe₃O₄, and Fe₂O₃ have been identified as markers for specific industrial sources [11].

Industrial Manufacturing

Industrial activities contribute significantly to atmospheric heavy metal loads, with distinct profiles based on the specific industrial process.

- Sector-Specific Emissions: Key industrial subcategories include primary copper smelting (PCu), secondary metal smelting (SCu, SAl, SZn, SPb), iron-ore sintering (IOS), electric-arc furnace steelmaking (EAF), waste incineration (WI, HWI), and coal-fired power plants (CFPP) [11]. Each sector has a unique elemental fingerprint, which can aid in source identification during atmospheric monitoring.

- Global Disparities: The Global South was found to have higher emissions of Fe (28,212 t) compared to the Global North (22,801 t), a disparity linked to less stringent pollution control technologies and rapid infrastructure development [11].

- Health Risk Implications: The dominance of fine and sub-nanometer particles in industrial emissions is of particular concern for human health, as these sizes are associated with increased toxicity and potential to translocate into the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid [11].

Urban Runoff

Urban stormwater runoff is a major diffuse pollution pathway, mobilizing heavy metals deposited on impervious surfaces.

- Source and Land Use Influence: Heavy metals in runoff originate from diverse sources, including vehicle wear (tires, brakes), atmospheric deposition, building materials, and industrial activities [15] [13]. Areas with heavy development and high traffic density pose a significantly greater public health risk [15].

- Pollutant Speciation and Mobility: Heavy metals in stormwater are classified into particulate, organically bound, and ionic forms [16]. The partitioning determines their mobility and treatment; ionic forms are more easily absorbed by organisms, while particulate forms are often removed via filtration [16] [13].

- Leaching and Remobilization Risks: Stormwater Control Measures (SCMs), designed to be a sink for pollutants, can become a source under unfavorable conditions. Leaching of heavy metals like Zn and Cu from sorptive filter media can occur during prolonged dry periods or under the influence of de-icing salts, which promote cation exchange and chloride complex formation [13].

Experimental and Analytical Methodologies

Standardized protocols are essential for consistent data collection, analysis, and interpretation in heavy metal research.

Soil Sample Collection and Analysis for Source Apportionment

Objective: To determine the concentration, spatial distribution, and sources of heavy metals in soils from contaminated sites [9].

Procedure:

- Site Selection and Sampling: Establish a sampling grid considering topography, soil distribution, and proximity to suspected pollution sources. Collect soil samples (e.g., from the top 0-20 cm layer) using a stainless-steel soil corer or spatula [9].

- Sample Preparation: Air-dry collected samples at ambient temperature or in an oven at low temperature (e.g., 38 ± 2°C). Homogenize and sieve (e.g., through a 2-mm nylon mesh) to remove debris [9] [10].

- Digestion and Analysis: Digest a representative sub-sample (e.g., 0.5 g) with a strong acid mixture (e.g., HNO₃-HCl-HF) in a microwave-assisted digestion system. Analyze the digested solution for heavy metal concentrations using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [9] [12].

- Data Processing and Source Apportionment:

- Conduct spatial distribution analysis using GIS software.

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA) to identify correlated metal groups and potential sources [10].

- Apply Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF), a receptor model, for quantitative source apportionment. Input data for PMF is a matrix of sample concentrations with corresponding uncertainty estimates. The model resolves the number of sources, their chemical profiles, and their contributions to each sample [9].

Stormwater Runoff Collection and Heavy Metal Analysis

Objective: To quantify the concentration and speciation of heavy metals in urban stormwater runoff [12].

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect stormwater from targeted locations (e.g., streets, ditches, outfalls) after rain events using pre-cleaned containers. Note land use type (e.g., commercial, residential, industrial) and antecedent dry days [12].

- Sample Preservation and Preparation: Acidify a portion of the sample to pH <2 with ultrapure nitric acid (HNO₃) for "total" metal analysis. Filter another portion through a 0.45 μm membrane filter for "dissolved" metal analysis [12].

- Metal Dissolution and Analysis: For total metal analysis, digest the unfiltered, acidified sample by heating to 65°C with concentrated HNO₃ to dissolve suspended particles. After digestion, filter the sample (0.45 μm) to remove residual particulates. Analyze both total and dissolved fractions using ICP-MS [12].

Sequential Extraction Procedure (SEP) for Metal Mobility

Objective: To evaluate the mobility and potential bioavailability of heavy metals in solid matrices (soils, sediments, filter media) by sequentially extracting them with chemicals of increasing strength [13].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Oven-dry and homogenize the solid sample.

- Sequential Extraction Steps: The following is a common sequence, though protocols may vary:

- Step 1 (Acid-soluble/exchangeable): Extract with weak acid (e.g., acetic acid) or salt solution (e.g., MgCl₂). This fraction is considered the most mobile and bioavailable.

- Step 2 (Reducible): Extract with a reducing agent (e.g., hydroxylamine hydrochloride) targeting metals bound to Fe/Mn oxides.

- Step 3 (Oxidizable): Extract with an oxidizing agent (e.g., hydrogen peroxide) to release metals associated with organic matter and sulfides.

- Step 4 (Residual): Digest the remaining solid with strong acids (HNO₃, HF, HClO₄). This fraction is tied to the crystal lattice of minerals [13].

- Analysis: Analyze the extract from each step via ICP-MS or AAS. The sum of the first three fractions (acid-soluble, reducible, oxidizable) is often considered the potential mobile fraction [13].

Health Risk Assessment Models

Objective: To quantify the potential non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks posed by exposure to heavy metals in environmental media [9].

Procedure:

- Exposure Assessment: Calculate the Average Daily Dose (ADD) for different exposure pathways:

- Ingestion: ADDing = (C × IngR × EF × ED) / (BW × AT)

- Inhalation: ADDinh = (C × InhR × EF × ED) / (BW × AT × PEF)

- Dermal Contact: ADD_derm = (C × SA × AF × ABS × EF × ED) / (BW × AT) Where C=metal concentration; IngR/InhR=ingestion/inhalation rate; EF=exposure frequency; ED=exposure duration; BW=body weight; AT=averaging time; SA=skin surface area; AF=skin adherence factor; ABS=dermal absorption fraction; PEF=particle emission factor [9].

- Risk Characterization:

- Non-Carcinogenic Risk: Calculate the Hazard Quotient (HQ) for each metal and pathway (HQ = ADD / Reference Dose RfD). The sum of HQs for all metals is the Hazard Index (HI). HI > 1 indicates potential non-carcinogenic risk [9] [10].

- Carcinogenic Risk: Calculate the Cancer Risk (CR) for carcinogenic metals (e.g., As, Cd, Cr, Pb) (CR = ADD × Slope Factor). Total CR is the sum of individual metal risks. CR > 1×10⁻⁴ is generally considered unacceptable [9] [10].

- Probabilistic Analysis: Incorporate variability and uncertainty in exposure parameters using Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS), which performs thousands of iterations using random values from probability distributions for each input parameter (e.g., body weight, ingestion rate) to generate a probability distribution of the output risk [9].

Visualization of Research Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental and analytical pathways described in this guide.

Soil Source Apportionment and Risk Workflow

Stormwater Metal Fate and Treatment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Heavy Metal Analysis

| Category | Item / Reagent | Technical Function in Research & Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Ultrapure Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digesting agent for dissolution of metal cations from solid matrices (soils, sediments, filters). |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Oxidizing agent used in digestion and sequential extraction to break down organic matter and sulfides. | |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Powerful digesting agent for dissolution of siliceous and aluminosilicate matrices in soil/rock samples. | |

| Sequential Extraction | Acetic Acid (CH₃COOH) | Weak acid for extracting the mobile, bioavailable (acid-soluble/exchangeable) metal fraction [13]. |

| Hydroxylamine Hydrochloride (NH₂OH·HCl) | Reducing agent for extracting metals bound to amorphous Fe and Mn oxyhydroxides (reducible fraction) [13]. | |

| Field Sampling & Analysis | 0.45 µm Membrane Filters | Standard for operational separation of "dissolved" (filtrate) and "particulate" (retentate) metal fractions in water [12]. |

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | Certified reference materials for instrument calibration to ensure accurate and traceable quantitative analysis [12]. | |

| Remediation & Treatment Studies | Biochar | Porous carbonaceous soil amendment; increases sorption capacity, reduces metal mobility and bioavailability [16] [8]. |

| Zeolite / Clinoptilolite | Sorptive filter media in SCMs; removes dissolved metals via ion exchange and adsorption [16] [13]. | |

| Hyperaccumulator Plants | Plant species (e.g., certain Brassicas) used in phytoextraction to uptake and concentrate metals from soil/water [16]. |

Heavy metal contamination represents a pervasive and persistent threat to global ecosystems and human health. The fate and transport of these pollutants from industrial and urban sources through environmental compartments—soil, water, and ultimately the food chain—constitute a critical pathway for human exposure. This technical guide examines the mechanistic pathways governing heavy metal behavior in the environment, drawing upon current research to elucidate the complex journey of these contaminants from emission sources to biological systems. Understanding these processes is fundamental to developing effective risk assessment protocols and remediation strategies for mitigating the impacts of heavy metal pollution on both ecosystem integrity and public health.

Heavy metals enter the environment through both natural geogenic processes and anthropogenic activities, with the latter dominating metal fluxes in many regions. Natural sources include volcanic eruptions, rock weathering, and erosion, while anthropogenic emissions have dramatically increased with industrialization, urbanization, and intensive agricultural practices [17].

Industrial point sources represent significant emission pathways. Research in Handan, a typical steel-producing city, demonstrated that industrial chimneys, workshops, and factory areas release substantial quantities of PM2.5-borne heavy metals, with total average mass concentrations measuring 9598.64 ng·m−3, 7332.94 ng·m−3, and 3104.31 ng·m−3 respectively at these sources [18]. These emissions significantly exceed background concentrations measured at control points (1004.74 ng·m−3), highlighting the substantial impact of industrial activities on ambient metal concentrations [18].

Table 1: Heavy Metal Concentrations at Industrial Sampling Sites

| Sampling Location | Total Average Metal Concentration (ng·m⁻³) | Primary Contributing Elements | Notable Health Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Chimney | 9598.64 | Fe, Ti, Zn, Ni | Co, Cr(VI), Mn, Pb, As |

| Production Workshop | 7332.94 | Fe, Ti, Zn, Ni | Co, Cr(VI), Mn, Pb, As |

| Factory Area | 3104.31 | Fe, Ti, Zn, Ni | Co, Cr(VI), Mn, Pb, As |

| Control Point B | 2073.21 | - | - |

| Control Point A | 1004.74 | - | - |

Non-point sources also contribute significantly to metal contamination. Agricultural practices, including the application of phosphate fertilizers, represent a major diffusion source. These fertilizers, particularly those produced from acidulated phosphate rock, retain heavy metals present in the original rock matrix, leading to progressive soil accumulation with repeated application [19]. Additional diffuse sources include atmospheric deposition of particulate matter, wastewater discharge for irrigation, and stormwater runoff from urban areas.

Transport Mechanisms and Environmental Fate

Atmospheric Transport and Deposition

Atmospheric transport represents a crucial mechanism for regional heavy metal dispersion. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) serves as a primary vector for metal transport over considerable distances. AERMOD dispersion modeling of PM2.5 emissions from industrial chimneys in Handan demonstrated significant regional dispersion within a 10-kilometer radius, corroborated by sample analysis at control points [18]. Particulate analysis revealed that mineral particles (31.58%), iron-containing metal oxides (26.32%), and soot aggregates (23.68%) dominated the single particles emitted from chimneys, with mixed particles primarily present as external mixtures [18].

Once airborne, metals undergo deposition processes including wet deposition (precipitation scavenging) and dry deposition (gravitational settling and impaction), transferring contaminants from the atmosphere to terrestrial and aquatic systems. This atmospheric pathway explains metal contamination in areas distant from primary emission sources.

Soil Mobility and Bioavailability

The mobility, bioavailability, and ultimate fate of heavy metals in soil systems are governed by complex interactions with soil constituents. Multiple pedovariables significantly influence metal speciation and mobility:

- Soil pH: Heavily influences metal speciation and solubility. A pH increase from 4 to 7 can decrease the most bioavailable Cd²⁺ fraction by >60%, favoring less bioavailable organo-complexed forms [17]. In acidic conditions (pH < 5), free cationic forms dominate, while alkaline conditions (pH > 8) favor poorly mobile forms such as carbonates, phosphates, or crystalline forms [17].

- Soil Organic Matter (SOM): Organic complexation can reduce metal mobility through chelation and adsorption processes. Amendments that increase SOM, such as biochar, influence soil pH, expand surface area for metal adsorption, and enhance microbial activities, ultimately facilitating remediation of contaminated soils [17].

- Clay Content and Mineralogy: Fine soil particles (clay, silty clay) typically exhibit stronger accumulation of metal(loid)s due to their high surface area and charge characteristics [17].

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC): Soils with higher CEC generally exhibit greater retention of cationic metal species.

- Oxidation-Reduction Potential: Influences valence state changes that critically affect metal mobility and toxicity, particularly for elements such as chromium and arsenic.

These interactions determine the chemical speciation of metals, which controls their environmental behavior and potential for entry into the food chain.

Aquatic System Transport

In aquatic environments, metals distribute between dissolved and particulate phases based on water chemistry, flow dynamics, and sediment interactions. Long-term monitoring of European streams and rivers (2000-2020) has revealed declining trends for mercury, lead, and cadmium in many watercourses, though these trends have not been monotonic [20]. Since 2015, increasing trends have outnumbered decreasing ones, potentially indicating legacy effects of metals retained in catchment soils [20].

Organic carbon content significantly explains seasonal variation in mercury and lead concentrations in watercourses, though it appears less influential for long-term interannual trends [20]. Other factors affecting aquatic metal transport include water hardness, dissolved oxygen, suspended sediment load, and biological activity.

Uptake and Translocation in Biological Systems

Plant Mechanisms

Plants interact with heavy metals through complex uptake and translocation mechanisms mediated by specialized transporter proteins. At least 313 heavy metal-associated transporters (HMATs) distributed across 17 transporter families have been identified as responsible for metal uptake, transport, and translocation in plants [21]. These transport systems enable two primary accumulation strategies:

- Root Uptake: Hyperaccumulators enhance metal solubility through rhizosphere acidification via proton secretion and release of organic acids that form metal complexes [19]. This is complemented by greater root proliferation that promotes improved metal uptake [19].

- Root-to-Shoot Translocation: Unlike non-hyperaccumulator plants that typically retain metals in root tissues, hyperaccumulators efficiently transport metals to aerial parts through the xylem, facilitated by specific transporter proteins that complex and shuttle metals upward [21].

Table 2: Heavy Metal Transporter Families in Plants

| Transporter Family | Primary Metals Transported | Cellular Localization | Function in Metal Homeostasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMA (Heavy Metal ATPase) | Cd, Pb, Zn, Co | Plasma membrane, tonoplast | Efflux, vacuolar sequestration |

| NRAMP (Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein) | Fe, Cd, Mn, Co | Endomembranes | Metal ion uptake and translocation |

| ZIP (ZRT/IRT-like Protein) | Zn, Fe, Cd, Mn | Plasma membrane | Metal uptake into cytoplasm |

| YSL (Yellow Stripe-Like) | Cu, Ni, Fe, Zn | Plasma membrane | Metal-nicotianamine complex transport |

| MTP (Metal Tolerance Protein) | Zn, Cd, Co, Fe | Tonoplast | Vacuolar sequestration |

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in heavy metal uptake, translocation, and detoxification in plants:

Food Chain Contamination

Heavy metals enter the food chain primarily through plant uptake from contaminated soils and irrigation water, with subsequent transfer to consumers. A study in Neyshabur, Iran, investigated heavy metal concentrations in frequently consumed leafy vegetables (mint, basil, parsley, chives, and coriander) grown near the Tehran-Mashhad highway [22]. Lead concentrations in all vegetable samples exceeded permissible levels endorsed by the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization, though other heavy metals (copper, iron, nickel, and zinc) remained below maximum permissible levels [22].

The transfer factor of metals from soil to plants depends on multiple factors, including plant species and genotype, metal speciation in soil, root system architecture, and agricultural practices. Some plant species exhibit particularly efficient metal uptake, leading to potentially hazardous concentrations in edible tissues even when soil concentrations appear moderately elevated.

Health Risk Assessment Methodologies

Risk Characterization Framework

Human health risk assessment for heavy metals follows a structured framework that addresses the special attributes and behaviors of metals and metal compounds [23] [24]. The process involves:

- Hazard Identification: Determining the adverse health effects associated with specific metals based on toxicological data.

- Dose-Response Assessment: Characterizing the relationship between exposure level and probability of health effects.

- Exposure Assessment: Quantifying the magnitude, frequency, duration, and route of exposure for target populations.

- Risk Characterization: Integrating the above components to estimate the probability of adverse health effects under specific exposure conditions [24].

The fundamental principle governing risk characterization is that a hazard only becomes a risk if exposure exceeds a safe threshold value [24]. For metals, this assessment must consider factors including ambient concentrations, essentiality (for nutrients like zinc and copper), chemical speciation, and human variability in sensitivity [24].

Analytical Methods for Exposure Assessment

Accurate quantification of heavy metal concentrations in environmental and biological samples is essential for exposure assessment. Multiple analytical techniques are employed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection

| Technique | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | Ionization in plasma, mass separation | Very high (ppt-ppb) | Soil, water, biological tissues | High sensitivity, multi-element capability; expensive instrumentation |

| AAS (Atomic Absorption Spectrometry) | Ground state atom light absorption | Moderate (ppb) | Water, soil extracts, plant tissues | Cost-effective, simple operation; lower sensitivity for some metals |

| ICP-AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy) | Plasma excitation, emitted light measurement | High (ppb) | Water, soil, biological samples | Wide dynamic linear range, multi-element capability |

| AFS (Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry) | Photon excitation, fluorescence measurement | High (ppb) | Mercury, arsenic, selenium speciation | High sensitivity for hydride-forming elements |

Biomarkers and Health Effects

Heavy metals induce diverse toxic effects through multiple mechanistic pathways. The primary mechanisms include:

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation: Most heavy metals (Hg, Pb, Cr, Cd, As) induce oxidative stress by generating ROS, which damage cellular components including lipids, proteins, and DNA [25].

- Enzyme Inactivation: Metals bind to functional groups of enzymes, particularly thiol groups, disrupting catalytic activity. Lead specifically inactivates δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (δ-ALAD) and ferrochelatase, inhibiting heme biosynthesis [25].

- DNA Damage and Genomic Instability: Carcinogenic metals including arsenic, cadmium, and chromium disrupt DNA synthesis and repair mechanisms, contributing to their carcinogenic potential [25].

- Altered Cell Signaling: Metals disrupt calcium homeostasis, phosphorylation cascades, and neurotransmitter signaling, leading to dysfunction across multiple organ systems [25].

These mechanisms manifest in specific health effects depending on the metal, exposure level, and duration. For example, the health risk assessment in Handan identified substantial non-carcinogenic risk (hazard index >1) with Co, Cr(VI), Mn, and Pb as significant concerns, and moderate carcinogenic risk (10−4 ≤ CR < 10−3) with Cr(VI) and As as key contributors [18].

Experimental Protocols for Fate and Transport Studies

Field Sampling Methodologies

Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal fate and transport requires rigorous sampling protocols across environmental compartments:

Atmospheric Particulate Sampling:

- Utilize PM2.5 samplers with appropriate flow rates and collection media (e.g., quartz or Teflon filters)

- Deploy samplers at multiple locations including emission sources (chimneys, workshops), factory areas, and background control points [18]

- Maintain sampling height at approximately 1.2m above ground for ambient air and 15m for chimney emissions to represent human exposure and source characteristics [18]

- Collect parallel samples across seasons to account for temporal variations

Soil Sampling Protocol:

- Collect soil samples from 0-20cm depth, representing the root propagation zone [22]

- Air-dry samples at room temperature, crush using a mortar, and sieve through 2mm mesh to remove debris [22]

- Store processed samples in pre-cleaned plastic bags to prevent contamination

- Analyze key soil parameters including pH, electrical conductivity, organic carbon content, and particle size distribution

Vegetation Sampling:

- Collect edible portions of vegetation using ceramic tools to prevent metal contamination

- Wash samples with deionized water to remove soil particles and atmospheric deposition

- Dry at room temperature or in a food dehydrator to constant weight

- Grind samples to homogeneous particle size using appropriate milling equipment

Laboratory Analysis Procedures

Sample Digestion for Total Metal Analysis:

- Soil Digestion: Digest approximately 100mg of soil with 3mL of 37% HCl, 1mL of 65% HNO3, 6mL of 65% HF, and 0.5mL of 65% HClO4 using a two-stage temperature program: (1) 10 minutes to reach 200°C, and (2) 15 minutes at 200°C [22]. Evaporate to near dryness, then dissolve in 1mL of 65% HNO3 and 20mL deionized water.

- Vegetation Digestion: Use acid mixture appropriate for organic matrices (typically HNO3-H2O2) in closed-vessel microwave systems to ensure complete digestion of organic matter and release of metal constituents.

Sequential Extraction Procedures for Speciation Analysis: Employ standardized sequential extraction protocols (e.g., BCR, Tessier) to fractionate metals into:

- Exchangeable/water-soluble phase

- Carbonate-associated phase

- Fe-Mn oxide-bound phase

- Organic matter-associated phase

- Residual crystalline lattice phase

This fractionation provides crucial information on metal bioavailability and potential mobility under changing environmental conditions.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental protocol for assessing heavy metal fate and transport:

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Heavy Metal Studies

| Category/Item | Specification | Primary Application | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | |||

| PM2.5 Samplers | Flow-calibrated, quartz/Teflon filters | Atmospheric particulate sampling | Size-selective collection of airborne metals |

| Soil Corers | Stainless steel, ceramic-lined | Soil profile sampling | Minimize cross-contamination between samples |

| Polyethylene Containers | Acid-washed, trace metal grade | Sample storage and transport | Prevent adsorption and contamination |

| Laboratory Analysis | |||

| Nitric Acid | Ultra-pure grade, metal-free | Sample digestion | Complete oxidation of organic matter |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Trace metal grade | Organic matrix digestion | Oxidizing agent for plant/biological tissues |

| Certified Reference Materials | NIST, BCR standards | Quality assurance | Method validation and accuracy verification |

| Speciation Analysis | |||

| Sequential Extraction Reagents | NH4Cl, NaOAc, NH2OH·HCl, H2O2 | Chemical fractionation | Metal speciation and bioavailability assessment |

| Chelating Resins | Chelex-100, iminodiacetate | Pre-concentration and separation | Isolation of labile metal fractions |

| Molecular Studies | |||

| PCR Reagents | Metal-responsive gene primers | Gene expression analysis | Quantification of metal stress responses |

| Protein Extraction Kits | Compatible with metalloenzymes | Proteomic studies | Analysis of metal-binding proteins |

| Field Deployment | |||

| Passive Samplers | DGT (Diffusive Gradients in Thin Films) | In-situ bioavailability assessment | Measurement of labile metal fractions |

| Pore Water Samplers | Rhizon samplers | Soil solution collection | Non-destructive monitoring of soil solution |

The environmental fate and transport of heavy metals from industrial and urban sources through soil and water systems to the food chain represents a complex interplay of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Understanding these pathways is essential for accurate risk assessment and the development of effective remediation strategies. Current research demonstrates that despite regulatory efforts and declining emissions in some regions, legacy contamination and ongoing anthropogenic activities continue to pose significant challenges. The integration of advanced analytical techniques, molecular-level understanding of transport mechanisms, and comprehensive risk assessment frameworks provides powerful tools for addressing the persistent problem of heavy metal pollution. Future research directions should focus on elucidating metal-specific speciation dynamics in complex environmental matrices, improving in situ bioavailability assessment methods, and developing integrated remediation approaches that account for the multifaceted nature of metal contamination in anthropogenically impacted ecosystems.

Heavy metals, released into the environment through industrial and urban activities, induce toxicity via shared molecular pathways centered on oxidative stress and DNA damage, leading to carcinogenesis. This technical review details the mechanisms by which arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and nickel—classified as Group 1 carcinogens—generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), cause direct and indirect genotoxicity, and instigate epigenetic alterations. Supported by experimental data and pathway visualizations, this whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with a mechanistic framework for understanding metal-induced carcinogenesis and identifies potential molecular targets for therapeutic intervention.

Heavy metal pollution, originating from industrial discharges, urban traffic, and fossil fuel combustion, represents a significant global environmental health threat [5] [26]. Metals such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), and nickel (Ni) are classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) due to substantial evidence linking exposure to human cancers [27] [28]. The molecular pathogenesis of metal-induced toxicity follows convergent mechanisms, primarily involving oxidative stress, DNA damage, and epigenetic dysregulation [25] [27]. Understanding these precise mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted strategies to prevent and treat metal-associated diseases. This review dissects the molecular pathways activated by carcinogenic metals, provides quantitative data on exposure sources and health impacts, outlines key experimental methodologies, and visualizes critical signaling pathways to equip researchers with comprehensive mechanistic insights.

Heavy metals enter the environment through diverse anthropogenic activities, creating multiple exposure pathways for human populations. The table below summarizes major industrial sources and primary exposure routes for key carcinogenic metals.

Table 1: Industrial Sources and Human Exposure Pathways of Carcinogenic Heavy Metals

| Metal | Major Industrial Sources | Primary Human Exposure Routes | Key Health Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Mining, smelting, coal combustion, wood preservatives [28] [26] | Contaminated drinking water, food (e.g., rice) [28] | Skin, lung, bladder, and liver cancer [27] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Battery manufacturing, pigments, phosphate fertilizers, electroplating [29] [28] | Food chain (biomagnification), tobacco smoke, occupational inhalation [28] | Lung and prostate cancer, kidney damage, osteomalacia [25] [28] |

| Chromium (Cr) | Leather tanning, textile manufacturing, electroplating, petroleum refining [29] [26] | Occupational inhalation (CrVI), contaminated water [28] | Lung cancer, nasal and sinus cancers [27] |

| Nickel (Ni) | Alloy production, smelting, electroplating, fossil fuel combustion [5] | Occupational inhalation, contaminated food and water [5] | Lung and nasal cancers [27] |

Urban environments concentrate these pollutants; for example, recent studies on urban green space workers—a population with high exposure to traffic emissions—showed significantly elevated levels of cadmium, cobalt, and zinc in their urine and breathing air, accompanied by increased biomarkers of oxidative DNA damage [30]. This highlights how occupational exposure in urban settings contributes to internal metal burden and biological effects.

Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicity and Carcinogenesis

Oxidative Stress: The Central Pathway

A primary mechanism unifying metal toxicity is the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Both essential and non-essential metals disrupt the intracellular redox balance through direct and indirect processes.

- Direct ROS Generation: Metals like chromium (CrVI) and nickel (NiII) can undergo Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions, catalyzing the conversion of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide into highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [25] [27]. Copper and iron also participate vigorously in these cycles [31].

- Indirect ROS Generation: Arsenic and cadmium deplete cellular antioxidant defenses by binding to and inactivating critical sulfhydryl groups in enzymes like glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin. Cadmium further induces oxidative stress by displacing essential metals like zinc and iron from proteins, disrupting their homeostasis [25] [27]. Arsenic can activate ROS-producing enzyme complexes such as NADPH oxidase, further amplifying oxidative stress [27].

The resulting oxidative stress leads to lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage, creating a cellular environment conducive to mutagenesis and carcinogenesis [25] [31]. The interaction between metals and endogenous catecholamines can also exacerbate ROS production, particularly relevant in neuronal tissues [31].

DNA Damage and Genomic Instability

Sustained oxidative stress inflicts macromolecular damage, with DNA being a critical target. The table below categorizes and describes the major types of DNA damage induced by heavy metals.

Table 2: Types of Heavy Metal-Induced DNA Damage and Consequences

| Type of DNA Damage | Description | Primary Carcinogenic Metals | Resulting Genomic Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative DNA Adducts | ROS attack DNA bases, forming lesions like 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) [27] [30] | Cr, Ni, Cd, As | G→T transversions, point mutations [27] |

| DNA Strand Breaks | Single and double-strand breaks resulting from direct ROS attack or during faulty repair of base lesions [27] | Cr, As, Cd | Chromosomal aberrations, micronucleus formation [27] |

| DNA-Protein Crosslinks | Covalent bonds formed between DNA bases and nuclear proteins, blocking replication and transcription [27] | Cr | Replication fork collapse, mutations [27] |

| Inhibition of DNA Repair | Direct binding to and inactivation of DNA repair proteins (e.g., zinc finger proteins) [27] | As, Cd, Ni | Genomic instability, accumulation of mutations [27] [28] |

Arsenic exhibits a unique, primarily indirect genotoxicity. It does not directly form DNA adducts but potently inhibits multiple DNA repair pathways, including base excision repair (BER) and nucleotide excision repair (NER), by displacing zinc from the zinc-finger structures of repair proteins like poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) and XPA [27]. This leads to chromosomal instability, aneuploidy, and micronucleus formation. Cadmium and nickel also share this ability to inhibit DNA repair processes [27] [28].

Epigenetic Alterations

Beyond genotoxicity, metals drive carcinogenesis through epigenetic modifications that alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence.

- DNA Methylation: Arsenic exposure is associated with both global DNA hypomethylation and gene-specific promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes like p53 and p16 [27] [28]. This can lead to genomic instability and silencing of critical defense genes.

- Histone Modifications: Metals alter post-translational marks on histones. For instance, arsenic can reduce acetylation of H3K9 and H4K16, generally associated with gene silencing, and induce phosphorylation of H3, linked to oncogene activation [27].

- microRNA Dysregulation: Exposure to arsenic and cadmium alters the expression of numerous miRNAs, including oncogenic miRNAs (oncomiRs) like miR-21 and tumor-suppressor miRNAs like the let-7 family, thereby influencing cancer-related signaling pathways [27].

A novel epigenetic mechanism involves arsenic, cadmium, and nickel promoting the degradation of the stem-loop-binding protein (SLBP). This leads to aberrant polyadenylation and overproduction of canonical histone proteins (e.g., H3.1), disrupting the delicate balance of histone variants on chromosomes and causing transcriptional deregulation and chromosome instability [27].

The following diagram synthesizes the core mechanistic pathway of metal-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage, and carcinogenesis.

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Studies

Quantifying Oxidative DNA Damage via 8-OHdG

8-Hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is a widely used, reliable biomarker for oxidative DNA damage in occupational and environmental health studies [30]. Its stability and measurability in urine make it suitable for non-invasive biomonitoring.

Protocol Summary:

- Sample Collection: Collect spot urine samples from study participants (e.g., exposed workers and control groups). Centrifuge to remove solids and store aliquots at -80°C [30].

- Sample Analysis: Use commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (e.g., ZellBio GmbH kits) specific for 8-OHdG. The assay relies on the competitive binding between 8-OHdG in the sample and an 8-OHdG-enzyme conjugate to a specific monoclonal antibody coated on the plate [30].

- Data Interpretation: The intensity of the colorimetric signal is inversely proportional to the concentration of 8-OHdG in the sample. Concentrations are determined by comparison to a standard curve and are often normalized to urine creatinine to account for dilution [30].

Assessing Heavy Metal Exposure in Biological and Environmental Samples

Monitoring internal metal dose is critical for establishing exposure-response relationships.

Protocol for Air Sampling (NIOSH-7300 Method):

- Sample Collection: Use personal air sampling pumps (e.g., SKC Universal 44XR pump) with mixed cellulose esters (MCE) membrane filters. Sample at a flow rate of 2 L/min for a defined period (e.g., 3 hours) in the breathing zone of workers [30].

- Sample Preparation: Digest each MCE filter with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide using a defined heating program to dissolve metals and oxidize organic material [30].

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze the digested samples using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). Quantify metal concentrations by comparing the emission signals of the samples to those of calibrated standard solutions [30].

Protocol for Biological Monitoring (Urine):

- Sample Collection: Collect urine from subjects, acidify if necessary for preservation, and store frozen [30].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute urine samples appropriately with a dilute acid matrix. For lower detection limits, samples may require digestion or preconcentration [30].

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze prepared urine samples using ICP-OES to determine concentrations of metals like Cd, Co, and Zn. Results confirm systemic absorption and internal dose [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Assays

This section details essential reagents, kits, and instruments used in research on metal-induced toxicity.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Metal Toxicity Mechanisms

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ICP-OES/MS | Precise quantification of metal concentrations in diverse samples (air, water, urine, tissue) [30] | Measuring Cd, Co, Zn in urine of exposed workers [30] |

| 8-OHdG ELISA Kit | Quantifies 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine, a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage, in urine or cell/tissue extracts [30] | Assessing oxidative DNA damage in green space workers vs. office controls [30] |

| DCFH-DA Assay | Cell-permeable fluorogenic dye that measures intracellular ROS levels; oxidized to fluorescent DCF by ROS. | Detecting ROS generation in cultured cells treated with Cadmium or Arsenic. |

| Comet Assay (SCGE) | Detects DNA strand breaks at the single-cell level; visualizes genotoxicity of metals. | Demonstrating increased DNA damage in lymphocytes from Cr-exposed individuals. |

| Pathway Analysis Software | Bioinformatics tool for constructing and visualizing molecular interaction networks from literature data. | Modeling connectivity between As exposure and p53, oxidative stress [28] |

Visualizing Key Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the specific molecular interactions and cellular processes disrupted by carcinogenic metals, leading to cancer development.

The molecular mechanisms underlying heavy metal toxicity and carcinogenesis converge on the induction of oxidative stress, DNA damage, and epigenetic dysregulation. While shared pathways exist, each metal also exhibits unique interactions with cellular components, such as arsenic's degradation of SLBP and cadmium's disruption of calcium and zinc homeostasis. A profound understanding of these mechanisms, from initial ROS generation to the resulting genomic instability and aberrant gene expression, is paramount for public health protection and therapeutic development. Future research should prioritize the identification of precise molecular targets within these pathways for the development of chelation therapies, chemopreventive agents, and targeted treatments for individuals and populations burdened by heavy metal exposure from industrial and urban pollution.

Heavy metal (HM) pollution from industrial and urban activities represents a significant threat to global ecosystems, agricultural safety, and human health. These elements, including chromium (Cr), arsenic (As), nickel (Ni), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), persist indefinitely in the environment and bioaccumulate through the food chain [32]. At Superfund sites and other contaminated areas, HMs originate from diverse anthropogenic sources such as smelting operations, industrial discharges, atmospheric deposition, and improper waste disposal [33]. The persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulative potential of these contaminants necessitate sophisticated documentation and analysis methodologies to assess risks accurately and develop effective remediation strategies [32] [34].

This technical guide examines global case studies with a specific focus on documenting contamination patterns, assessing ecological and health risks, and implementing advanced analytical approaches. The content is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals with comprehensive protocols for characterizing heavy metal contamination at industrial sites, with emphasis on methodological standardization, data interpretation, and translational applications for risk assessment and remediation planning.

Global Case Studies in Heavy Metal Contamination

Case Study 1: Palmerton Zinc Superfund Site, Pennsylvania, USA

The Palmerton Zinc Superfund Site exemplifies the complex challenges associated with historic industrial contamination and the potential unintended consequences of remediation efforts. For nearly a century, zinc smelting operations deposited cadmium, lead, zinc, arsenic, and manganese across 3,000 acres of mountainous terrain, completely denuding vegetation and creating significant exposure pathways to nearby communities and water sources [35].

Remediation Strategy and Unintended Consequences: In the 1990s, the EPA authorized a novel remediation approach involving the application of 112,515 wet tons of municipal sewage sludge (biosolids) as fertilizer to promote revegetation and stabilize contaminated soils [35]. While this approach successfully restored plant growth and contained original metal contaminants, recent investigations revealed that the sewage sludge introduced per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) into the environment, subsequently contaminating groundwater and soil with these persistent "forever chemicals" [35]. This case highlights the critical importance of comprehensive contaminant screening before implementing remediation strategies, particularly when using waste-derived materials.

Case Study 2: Agricultural Region, Pearl River Estuary, China

Recent research from the Pearl River Delta (PRD) demonstrates the vertical migration of heavy metals in agricultural soils, challenging conventional surface-focused monitoring approaches. A 2025 study analyzing 72 paired surface (0-20 cm) and deep (150-200 cm) soil samples revealed that anthropogenic heavy metals significantly impact deep soil layers through processes including irrigation, atmospheric deposition, and subsurface migration [34].

Key Findings from the PRD Study:

- Cadmium (Cd) was identified as the primary pollutant, exhibiting extremely high values in both geo-accumulation index (Igeo) and potential ecological risk index (Er) assessments [34].

- Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), and Nickel (Ni) presented unacceptable non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks through food ingestion and dermal absorption pathways [34].

- Source apportionment using Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) revealed anthropogenic contributions of 90.2% for Cd, 65.4% for Cu, and 67.3% for Hg in surface soils, with significant anthropogenic influence persisting in deep layers (53.8% for Cd, 54.6% for Cu, 56.2% for Hg) [34].

Table 1: Heavy Metal Pollution Assessment in Pearl River Estuary Agricultural Soils

| Heavy Metal | Average Concentration (Surface) | Background Value | Main Pollution Source | Potential Ecological Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | Significantly elevated | Exceeded | Anthropogenic (90.2%) | High |

| Arsenic (As) | Elevated | Exceeded | Mixed (19.7% anthropogenic) | Moderate-High |

| Copper (Cu) | Elevated | Exceeded | Anthropogenic (65.4%) | Moderate |

| Mercury (Hg) | Elevated | Exceeded | Anthropogenic (67.3%) | Moderate-High |

| Lead (Pb) | Elevated | Exceeded | Mixed | Moderate |

| Zinc (Zn) | Elevated | Exceeded | Mixed | Moderate |

Table 2: Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Pearl River Estuary Soils

| Heavy Metal | Non-Carcinogenic Risk (HI) | Carcinogenic Risk (TCR) | Primary Exposure Pathway | At-Risk Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Unacceptable | Unacceptable | Food ingestion, Dermal absorption | General population |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Unacceptable | Unacceptable | Food ingestion | Agricultural communities |

| Chromium (Cr) | Unacceptable | Unacceptable | Dermal absorption | Farmers, Residents |

| Nickel (Ni) | Unacceptable | Unacceptable | Food ingestion, Dermal absorption | Agricultural communities |

Methodological Framework for Contamination Assessment

Standardized Sampling Protocols

Comprehensive soil sampling must account for both horizontal heterogeneity and vertical migration potential. The paired sampling approach demonstrated in the PRD study provides a robust framework for understanding contaminant mobility [34].

Surface Soil Collection (0-20 cm):

- Collect samples from the center and four vertices surrounding each sampling point using clean stainless-steel tools

- Combine and homogenize subsamples to create a composite representative sample

- Document GPS coordinates, soil type, land use history, and visible contamination

- Store in sterile polyethylene bags or containers at 4°C during transport [34]

Deep Soil Collection (150-200 cm):

- Utilize compact drill rigs with thin-wall soil samplers to minimize cross-contamination

- Collect samples from the parent material layer to establish background concentrations

- Replace drilling equipment between sites to prevent sample cross-contamination

- Document stratigraphic features and groundwater interfaces during collection [34]

Quality Assurance/Quality Control (QA/QC):

- Implement field blanks, duplicate samples, and certified reference materials

- Preserve samples at 4°C during transport and store frozen (-20°C) before analysis

- Process samples by air-drying at room temperature, removing visible gravel and plant roots, and homogenizing using ceramic grinders [34]

Analytical Techniques for Heavy Metal Quantification

Advanced analytical techniques are required to detect heavy metals at environmentally relevant concentrations across diverse sample matrices.

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection in Environmental Samples

| Analytical Technique | Detection Limits | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | sub-ppb to ppt | Multi-element analysis in soil, water, biological samples | High sensitivity, wide linear dynamic range | Matrix effects, spectral interferences |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) | ppb range | Targeted element analysis | Cost-effective, established methodology | Single-element analysis, lower throughput |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) | low-ppb range | Major and trace element analysis | Good precision, multi-element capability | Less sensitive than ICP-MS for trace elements |

Sample Digestion Protocol:

- Accurately weigh 0.5g of homogenized soil sample into Teflon digestion vessels

- Add 9mL concentrated HNO₃ and 3mL concentrated HCl (3:1 v/v ratio)

- Perform microwave-assisted digestion using a stepped temperature program (ramp to 180°C over 20 minutes, hold for 15 minutes)

- Cool, transfer digested solutions to volumetric flasks, and dilute to volume with deionized water

- Analyze digested solutions alongside method blanks, certified reference materials, and continuing calibration verification standards [34]

Contamination Assessment Indices

Geo-accumulation Index (Igeo):

Where Cn is the measured concentration of element n in soil, and Bn is the geochemical background value for element n. Igeo values are classified as: unpolluted (≤0), unpolluted to moderately polluted (0-1), moderately polluted (1-2), moderately to strongly polluted (2-3), strongly polluted (3-4), strongly to extremely polluted (4-5), and extremely polluted (>5) [34].

Potential Ecological Risk Index (RI):

Where Erᵢ is the potential ecological risk factor for an individual element, Trᵢ is the toxic response factor for the element (e.g., Cd=30, As=10, Cr=2, Cu=Pb=Ni=5), Cᵢ is the measured concentration, and Bᵢ is the background concentration [34].

Health Risk Assessment Models

Non-carcinogenic Risk Assessment:

- Hazard Quotient (HQ) = (ADD / RfD)

- Hazard Index (HI) = Σ HQᵢ Where ADD is the average daily dose and RfD is the reference dose for specific exposure pathways (ingestion, dermal, inhalation) [34].

Carcinogenic Risk Assessment:

- Total Carcinogenic Risk (TCR) = Σ ADD × SF Where SF is the slope factor for carcinogenic elements (As, Cd, Cr, Ni) [34].

Probabilistic Risk Assessment:

- Implement Monte Carlo simulation to address uncertainty in exposure parameters

- Generate probability distributions of risk outcomes based on parameter variability

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify dominant exposure factors [34]

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Source Apportionment Using Receptor Modeling

Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) has emerged as the predominant approach for quantitatively analyzing heavy metal sources in environmental samples [34].

PMF Methodology:

- Input data requirements: concentration matrix and uncertainty matrix

- PMF equation: X = GF + E, where X is the measured concentration matrix, G is the factor contribution matrix, F is the factor profile matrix, and E is the residual matrix

- Non-negative constraints and optimal factor number determination through residual analysis and interpretability assessment [34]

Application in the PRD Study: The PRD investigation identified four primary sources through PMF analysis:

- Industrial activities (electroplating, metallurgy)

- Agricultural practices (fertilizer and pesticide application)

- Traffic emissions

- Natural pedogenic processes [34]

The study demonstrated that conventional surface-only source analysis may significantly underestimate anthropogenic contributions due to downward metal migration, highlighting the necessity of multi-depth sampling strategies [34].

Artificial Intelligence in Heavy Metal Research

Advanced computational methods are transforming heavy metal detection, prediction, and remediation planning:

AI Applications:

- Predictive modeling of heavy metal mobility and bioavailability using machine learning algorithms

- Pattern recognition in large-scale contamination datasets to identify pollution hotspots

- Optimization of remediation strategies through simulation and decision-support systems

- Integration of remote sensing data with ground measurements for spatial risk assessment [36]

These AI-based approaches complement traditional analytical methods by enabling more sophisticated data integration, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling across complex environmental systems [36].

Research Toolkit for Heavy Metal Contamination Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Heavy Metal Analysis

| Research Reagent/Material | Technical Specification | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrapure Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Trace metal grade, ≥69% | Sample digestion and extraction | Primary digestant for most metal analyses |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Trace metal grade, ≥37% | Sample digestion assistant | Enhanes dissolution of certain metal compounds |

| Certified Reference Materials | NIST, NRCC certified | Quality assurance/quality control | Verification of analytical accuracy and precision |

| Multi-element Calibration Standards | NIST-traceable | Instrument calibration | Establishment of analytical calibration curves |

| Chelating Agents (DTPA, EDTA) | Analytical grade, ≥99% | Bioavailability assessment | Extraction of plant-available metal fractions |

| Preservation Reagents | Ultrapure, <5ppb metal content | Sample stabilization | Prevention of precipitation/adsorption losses |

Data Visualization and Interpretation

Effective data visualization is critical for interpreting complex contamination patterns and communicating findings to diverse audiences.

Visualizing Heavy Metal Pathways and Relationships

Experimental Workflow for Site Characterization

The documentation of heavy metal contamination at Superfund and industrial sites requires integrated approaches that combine traditional analytical methods with advanced modeling techniques. The case studies presented demonstrate that contamination extends beyond surface layers, with significant anthropogenic influence detected at depths of 150-200 cm, challenging conventional monitoring paradigms [34]. Furthermore, the Palmerton case illustrates how remediation strategies may inadvertently introduce emerging contaminants, emphasizing the need for comprehensive contaminant screening before implementing intervention measures [35].

Future research should prioritize the development of standardized protocols for multi-media, multi-depth contamination assessment, incorporating advanced source apportionment techniques and probabilistic risk assessment methodologies. Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches shows particular promise for predicting contaminant mobility, optimizing monitoring networks, and designing targeted remediation strategies [36]. As analytical capabilities continue to advance, researchers must maintain focus on translating scientific findings into practical interventions that protect ecosystem integrity and public health while supporting sustainable development in contaminated regions.

Advanced Techniques for Detection, Analysis, and Remediation

The precise quantification of heavy metals is a cornerstone of environmental science, forming the basis for monitoring, risk assessment, and remediation strategies in industrial and urban settings. Heavy metals such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) are persistent environmental pollutants that accumulate in ecosystems, posing significant health risks to humans and wildlife through food chain contamination [37]. Industrial activities—including foundry operations, fuel oil combustion, and historical legacy pollution—are primary sources of these contaminants, leading to their mobilization in air, water, and soil [38] [18] [12]. In this context, the selection of an appropriate analytical technique is not merely a procedural choice but a fundamental determinant of data quality and, consequently, the validity of environmental and public health decisions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three cornerstone analytical techniques—Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS), and Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption (GFAA)—framed within the pressing need to understand and mitigate heavy metal pollution from industrial and urban activities.

The accurate determination of elemental composition in complex environmental matrices requires sophisticated instrumentation. Each technique operates on distinct physical principles, offering a unique balance of sensitivity, throughput, and operational complexity.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)