Inorganic Pollutants in Water Resources: Sources, Pathways, and Health Implications for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of inorganic pollutants in water resources, detailing their primary sources, environmental pathways, and significant impacts on human health.

Inorganic Pollutants in Water Resources: Sources, Pathways, and Health Implications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of inorganic pollutants in water resources, detailing their primary sources, environmental pathways, and significant impacts on human health. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the mechanisms of pollutant toxicity relevant to disease etiology and reviews established regulatory frameworks alongside advanced detection and remediation technologies. The content further addresses current challenges in water treatment optimization and evaluates innovative assessment models for quantifying health risks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with methodological applications and comparative validations, this review aims to inform both environmental science and biomedical research, highlighting critical intersections for future investigation and therapeutic development.

Defining the Threat: Major Inorganic Pollutants and Their Environmental Pathways

Inorganic contaminants represent a pervasive and persistent challenge in the management of global water resources. These substances, which include toxic metals, metalloids, and other inorganic compounds, originate from both geogenic sources and anthropogenic activities, entering aquatic systems through complex pathways that threaten ecosystem integrity and human health. Within the broader context of sources and pathways of inorganic pollutants in water resources research, understanding the regulatory landscape governing these contaminants is paramount for developing effective mitigation strategies. The regulatory significance of these contaminants has prompted extensive scientific inquiry and the establishment of stringent monitoring and management frameworks worldwide. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the prevalence, health implications, and regulatory governance of inorganic contaminants, with particular emphasis on their behavior in aquatic environments and the methodological approaches for their detection and quantification.

Prevalence and Environmental Impact

Inorganic contaminants are widely distributed in global water systems, with their prevalence driven by both natural geological weathering and human activities such as industrial discharge, agricultural runoff, and improper waste disposal [1]. The environmental persistence and bioaccumulative potential of many inorganic contaminants create long-term management challenges, particularly in developing regions where industrial growth may outpace environmental protection measures.

A study conducted in northern Vietnam illustrates the severity of this issue, revealing that heavy metal concentrations in common food and water sources significantly exceeded national and international safety standards [2]. Mean concentrations of chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and arsenic (As) surpassed regulatory limits by at least two-fold in surface water and five-fold in well water, with seafood and vegetable samples showing substantial contamination [2]. The research demonstrated a clear inverse relationship between contaminant levels and distance from pollution sources, highlighting the role of industrial point sources in environmental contamination. This spatial gradient underscores the importance of understanding contaminant pathways from source to receptor in water resources management.

The environmental impact of inorganic contaminants extends through ecological systems, affecting aquatic organisms and accumulating in food chains. This bioaccumulation poses particular concern for human populations dependent on contaminated fisheries and agriculture. In developing countries, the challenges are exacerbated by limited wastewater treatment infrastructure, with inorganic contaminants often escaping conventional removal processes and persisting in water reuse systems [3].

Regulatory Framework for Inorganic Contaminants

United States Regulatory Standards

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) establishes legally enforceable standards for inorganic contaminants in public water systems under the National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) [4]. These standards are developed through a rigorous process that balances public health protection with technical and economic considerations, resulting in Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) based solely on health effects and enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) [5].

Table 1: US EPA National Primary Drinking Water Standards for Selected Inorganic Contaminants

| Contaminant | MCLG (mg/L) | MCL (mg/L) | Potential Health Effects from Long-Term Exposure | Major Sources in Drinking Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony | 0.006 | 0.006 | Increased blood cholesterol; decreased blood sugar | Petroleum refineries; fire retardants; ceramics |

| Arsenic | 0 | 0.010 | Skin damage, circulatory problems; increased cancer risk | Erosion of natural deposits; agricultural/industrial runoff |

| Asbestos | 7 MFL | 7 MFL | Increased intestinal polyp risk | Decay of asbestos cement pipes; natural deposits |

| Barium | 2 | 2 | Increased blood pressure | Drilling wastes; metal refineries; natural deposits |

| Beryllium | 0.004 | 0.004 | Intestinal lesions | Metal/coal-burning factories; electronic/aerospace industries |

| Cadmium | 0.005 | 0.005 | Kidney damage | Corrosion of galvanized pipes; metal refineries; batteries |

| Chromium (total) | 0.1 | 0.1 | Allergic dermatitis | Steel/pulp mills; natural deposits |

| Copper | 1.3 | TT¹ | Gastrointestinal distress; liver/kidney damage | Corrosion of household plumbing; natural deposits |

| Cyanide | 0.2 | 0.2 | Nerve damage; thyroid problems | Steel/metal factories; plastic/fertilizer factories |

| Fluoride | 4.0 | 4.0 | Bone disease; dental fluorosis in children | Water additive; natural deposits; fertilizer/aluminum factories |

| Lead | 0 | TT¹ | Developmental delays in children; kidney problems | Corrosion of household plumbing; natural deposits |

| Mercury | 0.002 | 0.002 | Kidney damage | Natural deposits; refineries; factories; landfill/agricultural runoff |

| Nitrate | 10 | 10 | Methemoglobinemia ("blue baby syndrome") in infants | Fertilizer runoff; septic tanks; sewage; natural deposits |

| Nitrite | 1 | 1 | Methemoglobinemia ("blue baby syndrome") in infants | Fertilizer runoff; septic tanks; sewage; natural deposits |

| Selenium | 0.05 | 0.05 | Hair/fingernail loss; numbness; circulatory problems | Petroleum refineries; natural deposits; mines |

¹TT = Treatment Technique (enforceable procedure rather than level)

The regulatory approach distinguishes between chronic health risks, which apply to most inorganic contaminants, and acute risks, which are particularly relevant for nitrate and nitrite due to their potential to cause methemoglobinemia or "blue baby syndrome" in infants [5]. The EPA's regulatory framework has evolved over time, with significant revisions such as the 2001 lowering of the arsenic standard from 50 ppb to 10 ppb to reflect improved understanding of its carcinogenic potential [5].

For industrial sources, the EPA establishes technology-based Effluent Guidelines that limit discharges of inorganic contaminants to surface waters and publicly owned treatment works [6]. These guidelines are categorized by industry type—such as metal finishing, organic chemicals manufacturing, and inorganic chemicals manufacturing—and are regularly updated to reflect advancements in treatment technologies [6].

Global Regulatory Perspectives

Globally, regulatory approaches to inorganic contaminants vary significantly, with developing countries often facing implementation challenges due to limited resources, infrastructure, and monitoring capacity [3]. The Vietnam study exemplifies these challenges, where regulatory standards existed but enforcement was insufficient to prevent widespread contamination of water and food sources [2].

Emerging contaminants, including newly recognized inorganic pollutants, present particular regulatory difficulties as they may not be included in routine monitoring programs, and their health and environmental impacts are not fully characterized [1] [3]. This regulatory gap is especially pronounced in developing nations, where rapid industrialization introduces novel contaminants without corresponding regulatory frameworks [3]. The research community has emphasized the need for strengthened global regulations, improved wastewater treatment strategies, and increased public awareness to mitigate the risks posed by both established and emerging inorganic contaminants [1].

Health Implications of Major Inorganic Contaminants

The health effects associated with exposure to inorganic contaminants vary considerably based on the specific contaminant, exposure level, duration, and route of exposure. The carcinogenic potential of many inorganic contaminants represents a significant public health concern, with arsenic, cadmium, and chromium (VI) classified as Group 1 Carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [2].

Arsenic exposure is associated with diverse health impacts, including skin lesions, peripheral neuropathy, and cancers of the bladder, lungs, skin, kidney, nasal passages, liver, and prostate [7]. Non-cancer effects can include thickening and discoloration of the skin, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, numbness in hands and feet, partial paralysis, and blindness [7]. The EPA has set the enforceable standard for arsenic in drinking water at 10 μg/L based on these well-established health risks [5].

Heavy metals including lead, cadmium, and chromium each present distinct toxicological profiles. Lead exposure is particularly detrimental to children, causing delays in physical and mental development, attention deficits, and learning disabilities [4]. In adults, lead exposure can cause kidney problems and high blood pressure [4]. Cadmium primarily targets the renal system, causing kidney damage even at relatively low exposure levels [7]. Chromium, particularly in its hexavalent form, can cause allergic dermatitis and damage to kidneys, nervous system, and circulatory system [7].

Nitrate and nitrite represent unique acute health risks, particularly for infants under six months of age, as they can interfere with the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood, causing methemoglobinemia or "blue baby syndrome" [8]. This condition can develop rapidly and be fatal if untreated, necessitating stringent limits on these contaminants in drinking water [5].

The cumulative and interactive effects of multiple inorganic contaminants remain an active area of research, with studies suggesting that combined exposures may produce synergistic health impacts that are not fully captured by individual contaminant regulations [2].

Analytical Methodologies for Inorganic Contaminant Detection

Standardized Detection Protocols

Accurate detection and quantification of inorganic contaminants is fundamental to regulatory compliance, environmental monitoring, and health risk assessment. Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS) represents a widely employed analytical technique for heavy metal analysis in environmental samples, offering sensitivity, specificity, and relatively low operational costs [2].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Inorganic Contaminant Analysis

| Research Reagent | Specification | Function in Analysis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | 65%, Puriss p.a. | Primary digesting agent for organic matrix decomposition | Microwave-assisted digestion of vegetable and seafood samples [2] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | 30%, Puriss p.a. | Oxidizing agent for complete organic matter digestion | Enhanced decomposition of complex biological matrices [2] |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | 40%, Puriss p.a. | Silicate dissolution for total metal recovery | Digestion of mineral-containing samples [2] |

| Calibration Standards | Multi-element AAS standards | Instrument calibration for quantitative analysis | Preparation of standard curves for concentration determination [2] |

| Reference Materials | Certified concentrations | Quality assurance and method validation | Verification of analytical accuracy and precision [2] |

The experimental workflow for inorganic contaminant analysis typically involves sample collection, preservation, preparation, digestion, and instrumental analysis, with strict quality control measures implemented at each stage to ensure data reliability.

Diagram 1: Analytical workflow for inorganic contaminant detection in environmental samples

Advanced Detection Approaches

While traditional methods like AAS remain widely utilized, emerging analytical techniques offer enhanced sensitivity, multi-element capability, and speciation analysis, which is particularly important for contaminants like arsenic and chromium whose toxicity depends on chemical form [1]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) provides lower detection limits and broader dynamic ranges, enabling measurement of contaminants at trace levels increasingly relevant for both regulated and emerging contaminants [1].

The development of innovative monitoring technologies represents an active research frontier, with scientists working to create more sensitive, cost-effective, and field-deployable detection systems that can improve spatial and temporal monitoring resolution [1]. These advancements are particularly crucial for addressing the analytical challenges posed by emerging contaminants, which often occur at very low concentrations (ng/L to μg/L) but may still present significant health risks due to their potency or persistence [3].

Inorganic contaminants remain a significant challenge in water resources management globally, with their prevalence, persistence, and potential health impacts necessitating robust regulatory frameworks and advanced analytical capabilities. The regulatory significance of these contaminants is evidenced by the detailed standards and monitoring requirements established by agencies like the U.S. EPA, though implementation challenges persist, particularly in developing regions. Future research directions should focus on advancing detection methodologies for emerging contaminants, elucidating the health impacts of complex contaminant mixtures, developing more efficient treatment technologies, and strengthening regulatory frameworks through science-based standard setting. As pressures on global water resources intensify due to population growth, industrialization, and climate change, sustained scientific and regulatory attention to inorganic contaminants will be essential for protecting both ecosystem and human health.

The degradation of global water resources by inorganic pollutants presents a critical challenge to ecosystem stability and public health. Understanding the origins of these contaminants is fundamental to developing effective mitigation strategies. This whitepaper examines the distinct sources and pathways of inorganic pollutants, framing the discussion within the broader context of water resources research. We specifically contrast geogenic deposits, originating from natural geological processes, with industrial discharges, resulting from anthropogenic activities. The persistence, toxicity, and slow decomposition of these pollutants, particularly heavy metals, necessitate a thorough investigation of their entry mechanisms into aquatic systems to inform robust monitoring and remediation protocols [9] [10].

This document provides a quantitative analysis of pollutant concentrations, details standardized methodological frameworks for source attribution, and illustrates complex pathways through dedicated visualizations. The intended audience includes researchers, environmental scientists, and public health professionals engaged in water quality management and pollution forensics.

Quantitative Analysis of Pollutant Concentrations

Global surveys of inland waters (rivers, lakes, reservoirs) provide critical baseline data for contextualizing local water quality assessments. Analyzing concentrations across different spatial scales and land-use types is essential for identifying pollution hotspots and attributing sources.

Table 1: Global Median Concentrations of Key Heavy Metals in Inland Waters

| Heavy Metal | Median Concentration (μg L⁻¹) | Key Natural/Geogenic Influences | Key Anthropogenic/Industrial Influences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (Cu) | 8.38 [9] | Geological weathering, soil erosion [9] [10] | Industrial wastewater, mining, smelting, material corrosion [9] [10] |

| Zinc (Zn) | 30.00 [9] | Atmospheric deposition, rock weathering [9] [10] | Industrial effluent (e.g., galvanizing), municipal wastewater, solid waste [9] [10] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 0.53 [9] | Volcanic activity, mineral dissolution [9] | Mining, fertilizer application, fossil fuel combustion [9] [10] |

| Chromium (Cr) | 7.00 [9] | Natural rock leaching [9] | Tanneries, metal plating, textile manufacturing, improper waste disposal [9] [10] |

Spatial analysis reveals significant global heterogeneity in pollution levels. Regions such as West and South Asia (e.g., India, Nepal, Iran) and Africa (e.g., Niger and Nile River basins) are identified as conspicuous hotspots, with heavy metal concentrations substantially elevated above global medians. These patterns are driven by intensive industrial and agricultural activities, often coupled with rapid urbanization [9]. Furthermore, seasonal variations significantly influence concentrations; for instance, copper and chromium levels are significantly higher during dry seasons compared to wet seasons, likely due to reduced dilution from precipitation [9]. Land use is another critical determinant, with industrial and residential areas discharging significantly higher loads of metals like copper and zinc into adjacent river systems compared to agricultural or natural lands [9].

Methodological Framework for Source Apportionment

Distinguishing between geogenic and anthropogenic sources requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining field sampling, advanced statistical modeling, and geospatial analysis.

Field Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

Protocol Objective: To collect and analyze water samples for inorganic pollutant concentrations.

- Sample Collection: Gather water samples from a representative network of sites (rivers, lakes, groundwater) reflecting gradients of land use (pristine, agricultural, urban, industrial). Samples should be collected in duplicate using pre-cleaned polypropylene bottles and preserved according to standard methods (e.g., acidification for metal analysis) [9].

- Filtration and Speciation: Process samples through 0.45μm membranes to differentiate between total and dissolved metal fractions. The dissolved fraction is critical for assessing bioavailable contaminants [9].

- Instrumental Analysis: Quantify metal concentrations using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). Maintain strict quality control with blanks, duplicates, and certified reference materials [9].

Statistical Modeling and Geospatial Analysis

Protocol Objective: To identify driving factors and predict spatial patterns of pollution.

- Driver Quantification: Employ a Random Forest (RF) model, a machine learning algorithm, to quantify the relative importance of various natural and anthropogenic factors. Critical predictors include:

- Spatial Prediction: Use the trained RF model to predict and map heavy metal concentrations across unsampled regions, identifying potential vulnerability zones and pollution hotspots [9].

- Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis: Utilize Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map the distribution of pollution sources and discharge points. This is particularly effective for visualizing complex urban systems, such as Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), where high-frequency overflows correlate with highly impervious areas and high-load discharges with densely populated zones [11].

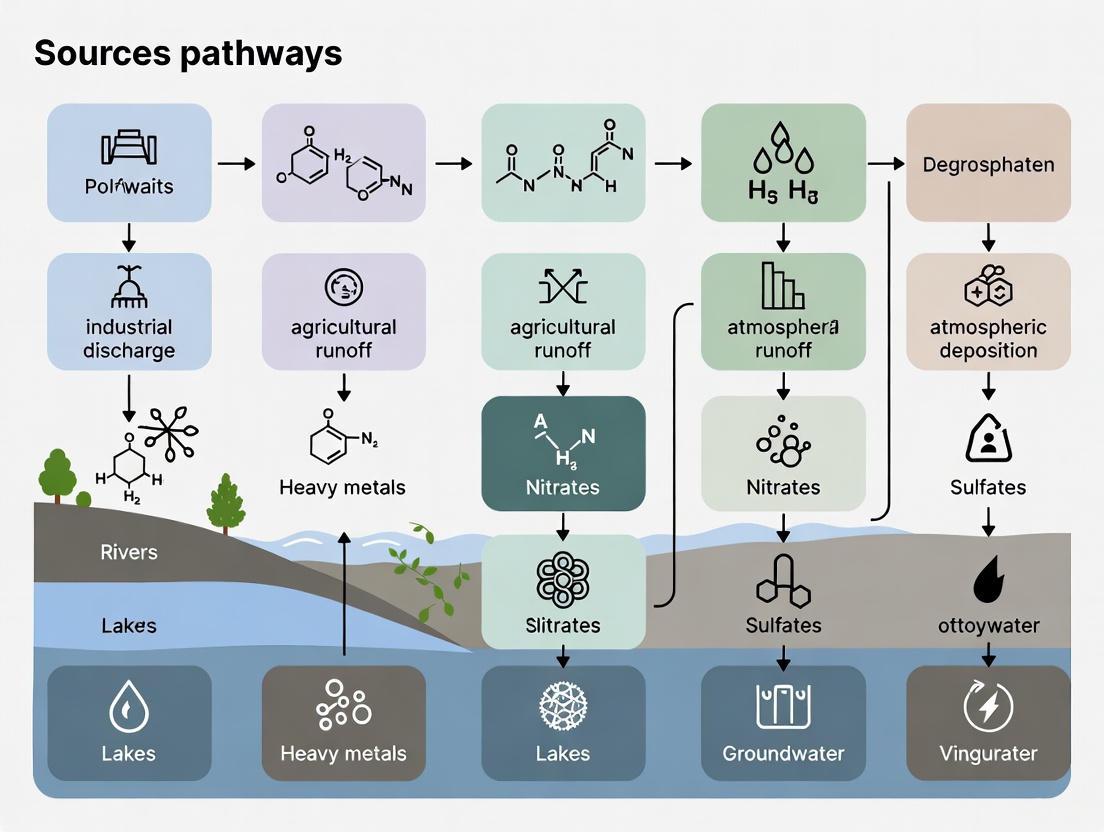

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated methodology for tracking inorganic pollutants from their sources to management actions.

Pathways of Inorganic Pollutants in Aquatic Systems

The transport of inorganic pollutants from geogenic and anthropogenic sources to water bodies involves distinct yet sometimes interconnected pathways. Understanding these routes is crucial for intercepting contaminant fluxes.

Geogenic Pathways are primarily governed by hydrological and weathering processes. Heavy metals naturally present in bedrock and soils are mobilized through chemical weathering and soil erosion [9] [10]. Rainfall and surface runoff then transport these mobilized contaminants into groundwater aquifers via infiltration or into rivers and lakes through surface runoff [10]. Additionally, atmospheric deposition from natural sources like volcanic activity and dust storms can contribute metals directly to water surfaces [9] [10].

Anthropogenic Pathways are more diverse and often result in higher localized concentrations. Industrial discharges from mining, smelting, and manufacturing facilities release effluents directly into water bodies (point sources) [10]. Urban wastewater systems, including untreated sewage and combined sewer overflows (CSOs), discharge nutrients, pharmaceuticals, and heavy metals [11] [10]. Agricultural runoff transports fertilizers and pesticides containing heavy metals from fields to streams, a classic non-point source [9] [10]. The interaction of stormwater and wastewater in sewer systems during extreme rainfall events leads to CSOs, which release untreated pollutants like pharmaceuticals (e.g., Carbamazepine, Ciprofloxacin) and organic compounds directly into rivers [11].

The following diagram synthesizes these primary pathways and their interactions within the aquatic environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key reagents, materials, and software solutions essential for conducting research on inorganic pollutants in water, as cited in the methodologies discussed.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Water Pollutant Research

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | Quantifying heavy metal (Cu, Zn, Cd, Cr) concentrations with high sensitivity. | Certified multi-element standard solutions traceable to NIST [9]. |

| Sample Preservation Reagents | Acidifying water samples to prevent adsorption of metals to container walls. | High-purity nitric acid (HNO₃), trace metal grade, to pH < 2 [9]. |

| Filtration Membranes | Separating dissolved and particulate metal fractions for speciation analysis. | 0.45 micrometer pore size, polyethersulfone or cellulose acetate [9]. |

| GIS Software | Spatial analysis, mapping pollution hotspots, and integrating land-use data. | Platforms like ArcGIS or QGIS for spatial heterogeneity analysis [11]. |

| Statistical Modeling Software | Running Random Forest models and other multivariate analyses. | R programming language with 'randomForest' package or Python with scikit-learn [9]. |

| Hydrological Simulation Software | Modeling urban runoff and combined sewer overflow (CSO) events. | EPA's Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) platform [11]. |

The intricate challenge of inorganic water pollution demands a clear and quantitative understanding of its dual origins in geogenic deposits and industrial discharges. While geogenic sources provide a regional background concentration, anthropogenic activities are the dominant drivers of severe pollution hotspots and elevated loads in global inland waters. Climate change and urbanization are exacerbating this issue, intensifying the temporal variability and severity of pollutant discharges [11] [9]. Tackling this problem effectively requires transdisciplinary research and cross-border communication, merging sound science with adaptable legislation and management systems [10]. The methodologies and data synthesized in this whitepaper provide a scientific foundation for targeting pollution control in vulnerable regions and developing sustainable water quality management strategies for the future.

The management and preservation of global water resources are critically dependent on understanding the primary pathways through which inorganic pollutants enter aquatic ecosystems. This technical guide examines three principal conduits—agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and corroded infrastructure—as integrated components of a larger hydrological pollution system. These pathways facilitate the transport of pervasive inorganic contaminants, including heavy metals, nutrients, and saline ions, which pose significant risks to environmental stability and public health [12] [13]. The persistence, ability to bioaccumulate, and complex interactions of these pollutants within water matrices make them particularly challenging to manage [12]. Furthermore, infrastructure corrosion is not merely a consequence of water quality but an active, self-reinforcing contributor that can exacerbate pollutant release [14]. This document synthesizes current research on the sources, characteristics, and transport mechanisms of these pollutants, providing a scientific foundation for targeted mitigation strategies and future research directions essential for protecting vital water resources.

Agricultural Runoff

Agricultural runoff represents a significant non-point source of water pollution, characterized by its diffuse origin and complex composition. The primary inorganic contaminants originate from the extensive application of fertilizers, pesticides, and soil amendments [13]. Key pollutants include:

- Nutrients: Total Nitrogen (TN) and Total Phosphorus (TP) from fertilizers, which drive eutrophication [13].

- Heavy Metals: Cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) are frequently present in agricultural soils, often introduced via impurities in phosphate fertilizers and certain pesticides [13] [15]. These metals can accumulate in sediments and bioaccumulate in the food chain.

- Salts and Ions: Potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), chloride (Cl⁻), and bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) can be mobilized from soils and contribute to the freshwater salinization syndrome [16] [13].

The concentration of these substances varies significantly based on land management practices, soil type, and hydrological conditions.

Transport Pathways and Environmental Fate

The transport of agricultural pollutants to water resources is governed by overland flow and subsurface drainage. During precipitation or irrigation events, water that cannot infiltrate the soil surface flows overland, picking up and carrying dissolved contaminants and sediment-bound particles into nearby streams, rivers, and groundwater systems [13]. The "Critical Pathway" diagram below illustrates this journey from source to receptor.

Figure 1: Critical Pathway of Agricultural Runoff. This diagram visualizes the sequence from pollutant application to environmental impact, highlighting the non-point source nature of agricultural contamination.

The environmental fate of these pollutants is complex. Nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus can stimulate excessive algal growth in receiving waters, leading to eutrophication, hypoxia, and fish kills [13]. Heavy metals tend to adsorb to sediment particles and can accumulate in riverbeds and estuaries, creating long-term contamination sinks [13] [15].

Experimental Protocol for Monitoring and Analysis

A standardized protocol for quantifying pollutant load in agricultural runoff is essential for research and regulatory compliance.

1. Watershed Delineation and Sampling Site Selection:

- Define the hydrological boundaries of the agricultural catchment area using topographic maps (e.g., USGS 7.5-minute series) or Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software [13].

- Establish sampling points at the catchment outlet and at key intermediate points representing different land uses or sub-catchments.

2. Automated Sampling and Flow Measurement:

- Install automated water samplers (e.g., ISCO 6712) programmed to collect samples based on flow-proportional or time-paced intervals, with increased frequency during and after storm events [16].

- Use flow meters (e.g., acoustic Doppler current profilers) to continuously measure discharge at the catchment outlet. This allows for the calculation of pollutant load (concentration × flow rate).

3. Field and Laboratory Analysis:

- In-Situ Measurements: Using multi-parameter sondes (e.g., YSI EXO2), measure pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Dissolved Oxygen (DO), and Temperature at each site.

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Nutrients: Analyze for TN and TP using standard methods such as persulfate digestion followed by colorimetric analysis on a flow injection analyzer (FIA) or discrete analyzer [13].

- Major Ions: Measure K, Ca, Mg, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻ using Ion Chromatography (IC) [16] [13].

- Heavy Metals: Filter water samples through a 0.45 µm membrane and analyze for Cd, Pb, and other metals using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [13].

4. Data Analysis and Load Calculation:

- Pollutant load is calculated by integrating concentration and flow data over time. Statistical analysis (e.g., regression) is used to correlate land use practices with pollutant export.

Table 1: Characteristic Pollutant Profiles in Agricultural Runoff

| Pollutant Category | Specific Parameters | Typical Concentration Ranges | Primary Environmental Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macro-Nutrients | Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP) | TN: 1-10 mg/L; TP: 0.1-1 mg/L [13] | Eutrophication, hypoxia, algal blooms [13] |

| Heavy Metals | Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb) | Low μg/L to mg/L (soil-dependent) [13] | Toxicity, bioaccumulation in food chains [13] [15] |

| Major Ions | Potassium (K), Chloride (Cl⁻) | K: 1-10 mg/L; Cl⁻: 5-50 mg/L [13] | Freshwater salinization, altered ecosystem function [16] |

Industrial Effluents

Pollutant Diversity and Point Source Characteristics

Industrial effluents are a major point source of inorganic pollution, with composition varying drastically by industry type. Unlike agricultural runoff, these discharges originate from discrete, identifiable locations such as discharge pipes [15]. The table below summarizes key industrial sectors and their characteristic inorganic pollutants.

Table 2: Industrial Sources and Associated Inorganic Pollutants

| Industry Sector | Characteristic Inorganic Pollutants | Typical Concentration Ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Processing & Finishing | Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Ni, Cr, Cd, Pb), Cyanides, Acids | Variable, can range from high μg/L to low mg/L [15] |

| Chemical Manufacturing | PFAS, Chlorobenzene, Acids, Alkalies, Residual Solvents | PFAS: ng/L to μg/L [12] [15] |

| Textile & Dye Production | Synthetic Dyes, Heavy Metals (Cu, Cr), Salt ions | High salinity; metals in μg/L range [13] [15] |

| General Process Waste | High Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD: 100-3000 mgO₂/L), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD: 10-2250 mgO₂/L), variable pH (5-12) [15] |

Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) from industrial sources, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and certain heavy metals, are particularly problematic due to their persistence, mobility, and resistance to conventional treatment processes [12] [13].

Advanced Treatment and Removal Technologies

Treating complex industrial wastewater requires advanced technologies beyond conventional methods. The following workflow illustrates the integration of these advanced processes for comprehensive pollutant removal.

Figure 2: Advanced Treatment Workflow for Industrial Effluents. This sequential process targets different pollutant classes, from resistant organics to dissolved ions and metals.

Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) utilize powerful hydroxyl radicals (•OH) to destroy persistent organic contaminants like PFAS. Techniques include UV-based systems, ozonation, and electrochemical oxidation that break complex molecules into benign end-products like CO₂ and fluoride ions [17].

Next-Generation Membrane Filtration technologies, such as reverse osmosis (RO) and nanofiltration (NF), have advanced with materials like graphene oxide and ceramic composites. These membranes feature uniform, engineered pores that reduce fouling and improve rejection rates for dissolved salts, metals, and micro-pollutants [12] [17].

Resource Recovery approaches are shifting the paradigm from mere treatment to valorization. Techniques like selective adsorption and chemical precipitation are used to recover valuable metals (e.g., cobalt, nickel, copper) from mining and electronic waste effluents, creating potential revenue streams while mitigating pollution [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research on treating industrial effluents relies on a specific suite of reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Industrial Wastewater Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Technical Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) Probes (e.g., Nitrobenzene) | Chemical probe to quantify the formation rate and exposure of •OH in AOPs. | Calibrating UV/H₂O₂ or ozone reactors for PFAS degradation [17]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Nanoparticles | High-surface-area adsorbent and membrane coating material. | Synthesizing novel composite membranes for enhanced heavy metal rejection [17]. |

| Magnesium-Based "Green" Reagents | Precipitating agent for metals and neutralizing agent for acidity. | Neutralizing acid mine drainage and co-precipitating dissolved metals for recovery [17]. |

| Ion-Selective Electrodes & Membranes | Potentiometric sensors for specific ions (e.g., Cl⁻, F⁻, NH₄⁺). | Real-time monitoring of specific contaminant ions in treatment process streams [16]. |

Corroded Infrastructure

Corrosion as a Source and Consequence of Pollution

Corroded water and wastewater infrastructure is a critical, often overlooked, pathway for inorganic pollutants. Corrosion itself can be both a primary source of metals (e.g., from lead pipes or iron fittings) and a secondary consequence of water chemistry, creating a damaging feedback loop [14]. The global cost of corrosion is estimated at US $2.5 trillion, accounting for roughly 3.5% of global GDP, with water systems representing a significant portion [14].

Key corrosion mechanisms in water systems include:

- Uniform Corrosion: General wastage of pipe material (e.g., iron, copper) leading to the release of metal ions into the water [14].

- Pitting Corrosion: Localized attack that can perforate pipes, releasing high concentrations of metals and providing niches for bacterial growth [14].

- Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC): Biofilms formed by bacteria, such as Desulfovibrio, produce corrosive metabolites (e.g., hydrogen sulfide) that accelerate metal decay [14].

The Role of Saltwater Intrusion

A growing threat to infrastructure integrity is saltwater intrusion in tidal rivers and coastal aquifers, driven by sea-level rise, drought, and over-extraction [16]. Elevated chloride (Cl⁻) concentrations from seawater are highly corrosive and degrade pipes, storage tanks, and treatment plant components. This compromises infrastructure and simultaneously introduces saline contaminants into freshwater supplies [16]. Nearly $100 million in agricultural activity in the Mid-Atlantic alone is at risk from this phenomenon, alongside immense costs to drinking water infrastructure [16].

Experimental Protocol for Corrosion Assessment

A comprehensive methodology for assessing corrosion in water distribution and wastewater collection systems is outlined below.

1. Specimen Preparation and Exposure:

- Prepare coupons (e.g., 2.5 cm x 5.0 cm) from materials of interest (e.g., carbon steel, ductile iron, copper).

- Polish coupons to a standard surface finish, degrease, and weigh to the nearest 0.1 mg.

- Mount coupons in pipe-flow test loops or secure them within racks placed in actual pipelines or treatment tanks for in-situ exposure over a defined period (e.g., 90-180 days) [14].

2. Corrosion Rate Monitoring:

- Electrochemical Techniques: Use a Potentiostat/Galvanostat to perform Linear Polarization Resistance (LPR) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) on electrodes made of the material under study. This provides real-time corrosion rate data.

- Weight Loss Measurement: After exposure, retrieve coupons and chemically clean them to remove corrosion products according to ASTM standard G1-03. Re-weigh the coupons to determine mass loss. The corrosion rate (CR) in millimeters per year (mm/y) is calculated as: CR = (K × W) / (A × T × D), where K is a constant, W is mass loss (g), A is area (cm²), T is time (hours), and D is density (g/cm³) [14].

3. Corrosion Product and Water Chemistry Analysis:

- Surface Analysis: Analyze the morphology and composition of corrosion products on the coupon surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) [14].

- Water Quality Correlations: Correlate corrosion rates with water quality parameters measured throughout the exposure period, including pH, dissolved oxygen, chloride (Cl⁻), sulfate (SO₄²⁻), and dissolved organic matter (DOM) [14].

Addressing the critical pathways of agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and corroded infrastructure requires an integrated, multi-faceted strategy. The following approaches are essential:

- Policy and Regulation: Strengthening regulatory frameworks to include emerging contaminants and enforce stricter discharge permits, while incentivizing the adoption of best management practices in agriculture and industry [12] [13].

- Advanced and Nature-Based Solutions: Promoting the implementation of advanced treatment technologies like AOPs and precision membranes for industrial point sources, alongside the wider use of cost-effective Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) like Constructed Wetlands (CWs) for non-point source treatment, which can achieve up to 88% removal efficiency for many contaminants [13].

- Infrastructure Modernization and Monitoring: Investing in corrosion-resistant materials and smart water systems that leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI) for real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance of infrastructure [17] [14]. Enhanced monitoring of major salt ions is crucial for protecting infrastructure in vulnerable coastal areas [16].

In conclusion, the pathways of agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and corroded infrastructure are interconnected components of the water pollution cycle. A holistic understanding of their distinct yet overlapping characteristics is the foundation for developing effective, sustainable management policies and technologies. Future efforts must focus on closing resource loops, enhancing system resilience, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration to safeguard water resources for future generations.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the health impacts of key inorganic pollutants, with a specific focus on their sources and pathways in water resources. For researchers and scientists in drug development and environmental health, understanding the mechanisms by which these pollutants exert carcinogenic, organ-damaging, and neurotoxic effects is critical for developing targeted interventions and therapeutic strategies. The complex interactions between pollutant exposure and disease pathogenesis involve multiple molecular pathways, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage, which will be explored in detail throughout this document. Framed within the broader context of inorganic pollutant pathways in aquatic systems, this review synthesizes current findings on several priority substances, including arsenic, heavy metals, and disinfection byproducts, highlighting their toxicological profiles and the experimental approaches used to characterize them.

Carcinogenicity of Pollutants

Key Mechanisms and Associated Pollutants

The carcinogenicity of environmental pollutants is mediated through diverse mechanisms, including direct DNA damage, cancer stem cell (CSC) induction, and receptor-mediated pathways. Table 1 summarizes the carcinogenic targets and primary mechanisms of several key inorganic pollutants.

Table 1: Carcinogenic Targets and Mechanisms of Key Pollutants

| Pollutant | Target Organs (Species) | Primary Carcinogenic Mechanisms | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Arsenic | Lung, Liver, Gallbladder, Ovary, Uterus (Mouse) [18] | Overproduction of Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs); Overexpression of COX-2 and ER-α in reproductive tissues [18] | "Whole-life" exposure model in CD1 mice (0-24 ppm in drinking water); Immunohistochemistry for CSC markers (ALDH1, CD133) [18] |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Multiple (Human/Animal) [19] | Mutagenic and carcinogenic properties via metabolic activation to DNA-binding intermediates [19] | Listed as priority pollutants by EU and US EPA; Epidemiological and toxicological studies [19] |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Cd, Cr, Ni) | Multiple (Human/Animal) [20] | Direct and indirect DNA damage; Inhibition of DNA repair; Oxidative stress via Fenton reaction (Cr, Ni, Co) [20] | In vitro and in vivo studies showing DNA base modification, crosslinking, and strand scission [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: "Whole-Life" Arsenic Carcinogenesis Bioassay

The following methodology details a comprehensive in vivo approach for assessing the carcinogenic potential of inorganic arsenic, replicating chronic human exposure scenarios [18].

- Animal Model and Husbandry: The study employs CD1 mice. The animal facility should be accredited (e.g., by AAALAC), with controlled temperature, humidity, and light cycles. Animals are provided with a basal diet and acidified water ad libitum [18].

- Test Article and Dosing: Sodium arsenite (NaAsO₂, ≥98% purity) is dissolved in drinking water at concentrations of 0 (control), 6, 12, and 24 ppm arsenic. These doses capture the upper range of human environmental exposure [18].

- Experimental Design and "Whole-Life" Exposure Protocol:

- Pre-breeding: Male and female breeder mice are exposed to arsenic-treated water two weeks prior to mating.

- Gestation and Lactation: Pregnant dams continue exposure throughout pregnancy and lactation.

- Offspring Exposure: At weaning (4 weeks of age), offspring are randomly selected (n=30/sex/dose) and continue to receive the same arsenic-treated water until the study termination at 104 weeks [18].

- Tissue Collection and Histopathological Analysis:

- A complete necropsy is performed on all moribund animals, animals found dead, and at terminal sacrifice.

- A comprehensive set of tissues (e.g., liver, lungs, kidneys, adrenals, reproductive organs, and all gross lesions) is collected.

- Tissues are fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for blinded pathological assessment [18].

- Immunohistochemical Analysis:

- Paraffin-embedded sections of tumors and target tissues are used.

- Key biomarkers include:

- CSC Markers: ALDH1 and CD133 to identify and quantify cancer stem cell populations.

- Receptor and Signaling Markers: Estrogen receptor-α (ER-α), cyclin D1, cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2), and NF-κB to investigate proliferative and inflammatory pathways [18].

Diagram 1: Arsenic Carcinogenicity Assessment Workflow

Pollutant-Induced Organ Damage

Liver Damage and NAFLD

Environmental contaminants in water resources are increasingly implicated in the development and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The global prevalence of NAFLD is over 25%, and environmental risk factors are now a key area of investigation [21]. Several pollutants have been identified as contributors to liver pathology through mechanisms involving lipid metabolism disruption and oxidative stress. Table 2 outlines the specific mechanisms by which different pollutant classes drive NAFLD.

Table 2: Mechanisms of Pollutant-Induced Liver Damage and NAFLD

| Pollutant Class | Specific Examples | Key Mechanisms in NAFLD/Liver Damage | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals | Arsenic, Cadmium, Lead [21] [20] | Oxidative stress; depletion of glutathione; inhibition of antioxidant enzymes; disruption of lipid metabolism pathways [20]. | Toxicological studies showing bioaccumulation in liver tissue; epidemiological associations [21] [20]. |

| Disinfection By-products (DBPs) | Trihalomethanes, Haloacetic acids [21] | Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation; metabolic disruption leading to steatosis [21]. | Positive associations in epidemiological studies; supported by toxicological data in animal models [21]. |

| Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | Dioxins, Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) [21] | Activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR); induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes; disruption of energy homeostasis [21]. | Analysis of great many epidemiological and toxicological studies [21]. |

| Microcystins (MCs) | MC-LR [21] | Potent inhibition of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A; leading to oxidative stress and cytoskeletal disruption [21]. | Strong evidence from toxicological studies [21]. |

Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Systemic Inflammation

The gut microbiome serves as a critical interface for ingested inorganic pollutants, playing a dual role in modulating their toxicity and being disrupted by them. This interaction represents a significant pathway for systemic organ damage [22].

- Heavy Metals (Arsenic, Cadmium, Lead): Exposure can directly alter bacterial community structure, reducing beneficial commensals and selecting for more harmful pathogens. This dysbiosis drives inflammation through metabolite production and activation of signaling pathways such as the LPS/TLR4 or proteoglycan/TLR2 pathways, contributing to a leaky gut and systemic inflammation [22].

- Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs): Pollutants like PCB-126 can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) within the intestine. This activation can, in turn, indirectly reshape the gut microbial composition, creating a pro-inflammatory milieu [22].

- Nitrates/Nitrites: The effect of these compounds on the host is heavily dependent on their transformation by gut bacteria into secondary and tertiary metabolites, including nitrosamines, which can have systemic toxic and carcinogenic effects [22].

Diagram 2: Gut-Liver Axis in Pollutant Toxicity

Neurotoxicity of Pollutants

Mechanisms and Neurological Outcomes

The nervous system is highly vulnerable to chemical insult, with over 850 chemicals known to produce neurobehavioral disorders [23]. Neurotoxicity can manifest as cognitive deficits, neurodevelopmental abnormalities, and neurodegenerative diseases. The developing nervous system is often uniquely susceptible to damage that can lead to permanent functional impairment [23]. Table 3 details the neurotoxic mechanisms of specific pollutant classes, with a focus on chlorinated disinfection byproducts (Cl-DBPs) and heavy metals.

Table 3: Neurotoxic Pollutants: Mechanisms and Functional Outcomes

| Pollutant Class/Example | Molecular/Cellular Mechanisms | Neurological Manifestations & Outcomes | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cl-DBPs (e.g., DCA, TCA, DCBQ) | Induction of oxidative stress & ER stress; DNA damage; inflammation (NF-κB); apoptosis & autophagy [24]. | Peripheral neuropathy; anxiety-like behavior; thermal hypoalgesia; reduced nerve conduction velocity; potential risk for neurodevelopmental & neurodegenerative diseases [24]. | In vitro studies on nerve cells; animal models showing behavioral and functional deficits [24]. |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Lead, Mercury) | Binding to sulfhydryl groups of proteins; generation of ROS; mitochondrial dysfunction [23] [20]. | Cognitive deficits; irreversible compromise of normal brain development in children; peripheral neuropathies [23]. | Extensive epidemiological data (e.g., lead); clinical experience; NIOSH identification as a leading work-related disorder [23]. |

| Organic Pesticides (e.g., Oxyfluorfen) | Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity; oxidative stress [25]. | Neurotoxic effects in non-target species; significant AChE inhibition reported in bivalves [25]. | Eco-toxicological bioassays using biomarkers in model organisms like C. edule [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Neurotoxicity in Marine Bivalves

This protocol utilizes the marine bivalve Cerastoderma edule as a bioindicator species to evaluate the neurotoxic effects of pollutants, incorporating the impact of abiotic factors like temperature [25].

- Organism Collection and Acclimation:

- Organisms (e.g., C. edule) are collected from a defined field site and transported to the laboratory in cold boxes with field water.

- In the laboratory, they are acclimated in glass aquariums with filtered seawater (salinity 20 PSU) for 48 hours with constant aeration. During acclimation, organisms are not fed. After acclimation, they are fed daily with a commercial microalgae mixture [25].

- Chemical Exposure and Bioassay:

- Test Chemicals: Stock solutions are prepared. For organic chemicals like oxyfluorfen, a solvent (e.g., acetone) may be used, ensuring the final concentration is below OECD guideline limits (e.g., <0.01%). For inorganic metals like copper, the stock is prepared directly in filtered seawater [25].

- Experimental Design: Organisms are exposed to a range of chemical concentrations (e.g., Cu from 81.25 to 605.58 µg L⁻¹; Oxyfluorfen from 1.88 to 21.36 mg L⁻¹) at different temperatures (e.g., 15°C, 20°C, 25°C) for 96 hours. Controls (negative and solvent control) are included [25].

- Vessel Material: Following OECD guidelines, plastic vessels are used for inorganic chemicals (e.g., Cu), and glass vessels for organic chemicals (e.g., Oxyfluorfen) [25].

- Biomarker Analysis as a Proxy for Neurotoxicity:

- Post-exposure, organisms are dissected, and tissues are homogenized for biochemical analysis.

- Primary Neurotoxicity Biomarker: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity is a key diagnostic biomarker. Significant inhibition of AChE indicates neurotoxic effects [25].

- Supplementary Biomarkers:

- Antioxidant Defense Enzymes: Catalase (CAT), Glutathione S-transferase (GST), Glutathione Reductase (GR), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) to assess oxidative stress response.

- Oxidative Damage: Thiobarbituric Reactive Substances (TBARS) levels are measured to indicate lipid peroxidation (LPO) [25].

- Data and Statistical Analysis: Dose-response and temperature-dependent effects are analyzed to determine LC50 values and sub-lethal biomarker responses.

Diagram 3: Neurotoxicity Pathways of Pollutants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential reagents, models, and methodologies used in the featured studies for investigating pollutant impacts.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Models for Pollutant Impact Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Example | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Model | CD1 Mouse | A robust, outbred strain for chronic carcinogenicity bioassays and "whole-life" exposure studies. | [18] |

| In Vivo/ Bioindicator Model | Cerastoderma edule (Marine Bivalve) | A bioindicator species for ecotoxicological studies; used to assess lethal and sub-lethal toxicity (e.g., neurotoxicity) under varying environmental conditions. | [25] |

| Test Chemical | Sodium Arsenite (NaAsO₂) | A common, well-characterized source of inorganic arsenic (AsIII) for preparing dosing solutions in toxicological studies. | [18] |

| Histology Stain | Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) | The standard staining protocol for histological analysis of tissue morphology and identification of pathological lesions, including tumors. | [18] |

| Immunohistochemistry Antibodies | Anti-ALDH1, Anti-CD133, Anti-ER-α, Anti-COX-2 | Used to detect and localize specific proteins in tissue sections (e.g., cancer stem cell markers, hormone receptors, inflammatory enzymes). | [18] |

| Biomarker Assays | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Activity | A key enzymatic biomarker for diagnosing neurotoxic effects, particularly for organophosphates and other contaminants. | [25] |

| Biomarker Assays | Catalase (CAT), GST, GPx, GR Activity | A suite of enzymatic assays to profile the antioxidant defense system and oxidative stress status in exposed organisms. | [25] |

| Oxidative Damage Assay | Thiobarbituric Reactive Substances (TBARS) | A common method to quantify lipid peroxidation, a key indicator of oxidative damage to cell membranes. | [25] |

| Analytical Tool | Mass Spectrometry | Advanced chemical analysis for detecting thousands of markers in biological samples (blood, urine) in exposomic studies. | [26] |

| Computational Framework | Exposomics | A data-driven approach to map all environmental exposures throughout life, using geospatial data, wearables, and AI. | [26] |

Arsenic, a naturally occurring metalloid, represents a significant global health concern due to its pervasive presence in the environment and potent toxicity. This case study examines the pathways through which arsenic moves from geological deposits into water resources, its systemic toxic effects on the human body, and its well-established role in carcinogenesis. Framed within the broader context of inorganic pollutants in water resources research, this analysis synthesizes current understanding of arsenic contamination dynamics, with particular attention to the interplay between natural biogeochemical processes and human activities that mobilize this toxic element. The World Health Organization estimates that over 200 million people worldwide are exposed to toxic levels of arsenic through contaminated drinking water, making arsenic a priority substance for environmental health research and regulatory action [27].

Arsenic occurs naturally in the Earth's crust and enters the environment through both natural processes and anthropogenic activities. Natural sources include volcanic activity, rock weathering, and mineral dissolution, while human activities such as mining, smelting, agricultural pesticide use, and industrial processes contribute to arsenic mobilization [28] [27]. The distribution of arsenic in groundwater exhibits significant geographical variation, with some of the highest concentrations reported in Bangladesh, India, Taiwan, and Chile [28] [27]. A recent study in Bangladesh's Gazipur industrial zone revealed that while arsenic concentrations (0.003 ± 0.004 mg/L) remained within acceptable limits, lead, iron, and manganese exceeded safe drinking water standards, illustrating the complex coexistence of multiple metallic contaminants in affected aquifers [29].

Hydrobiogeochemical Cycling

The mobility of arsenic in aquatic systems is governed by complex biogeochemical processes. A 2025 study revealed a previously underestimated pathway for arsenic pollution involving the shift of lake and river sediments from arsenic sinks to arsenic sources following the widespread loss of submerged aquatic plants [30]. These underwater macrophytes, such as Vallisneria natans, play a crucial protective role by releasing oxygen through their roots, creating conditions that promote the formation of iron plaques that trap and immobilize arsenic in sediments [30].

When these plants die due to water pollution or climate change, the system undergoes a dramatic transition from aerobic to anaerobic conditions. This shift dissolves the iron plaques and releases arsenic back into the water column. Research documented that after plant death, the abundance of iron-reducing bacteria surged by over 80%, contributing to a nearly 90% loss of arsenic once bound within the roots' protective iron plaque [30]. This pathway represents a significant feedback loop wherein environmental degradation begets further water quality deterioration.

Table 1: Key Hydrobiogeochemical Processes Affecting Arsenic Mobility

| Process | Conditions | Effect on Arsenic | Environmental Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reductive Dissolution | Anaerobic, high organic matter | Releases bound arsenic | Major mobilization mechanism in groundwater [29] |

| Oxidative Immobilization | Aerobic, presence of iron | Traps arsenic in iron plaques | Protective mechanism in vegetated sediments [30] |

| Plant-Mediated Rhizosphere Oxidation | Aerated root zones | Immobilizes arsenic | Submerged macrophytes as ecosystem protectors [30] |

| Microbial Iron Reduction | Anaerobic, bacterial activity | Releases arsenic | Contributes to arsenic mobilization after plant death [30] |

Systemic Toxicity and Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Arsenic Speciation and Toxicokinetics

The toxicity of arsenic depends critically on its chemical form and oxidation state. Arsenic exists in four common valence states: elemental arsenic (As0), arsenite (trivalent, AsIII), arsenate (pentavalent, AsV), and arsine gas [28]. In general, inorganic forms are more toxic than organic forms, and trivalent arsenic compounds are more toxic than pentavalent compounds [31]. The metabolism of arsenic involves reduction from pentavalent to trivalent state followed by oxidative methylation, with the trivalent methylated metabolites now recognized as highly toxic species [32].

Approximately 60-90% of ingested inorganic arsenic is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, with initial distribution to the liver, kidney, muscle, and skin [28]. Excretion occurs primarily through the renal system, with only about 30% of inorganic arsenic eliminated within the first week, contributing to its cumulative toxicity [28].

Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicity

Arsenic induces cellular injury and death through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

Interference with Cellular Respiration and Energy Production At a biochemical level, trivalent arsenic (arsenite) reacts with sulfhydryl groups of critical enzymes, including those in the pyruvate oxidation pathway and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [31]. This inhibition disrupts cellular respiration and impairs ATP production. Pentavalent arsenic (arsenate) can replace phosphate in biochemical reactions due to their similar structure and properties, leading to the formation of unstable compounds such as glucose-6-arsenate that disrupt glycolysis [32]. The replacement of stable phosphorus with arsenic in ATP formation results in rapid hydrolysis of high-energy bonds, effectively uncoupling mitochondrial respiration [31].

Oxidative Stress Arsenic metabolism generates reactive oxygen species, increasing oxidative stress and damaging DNA, lipids, and other macromolecules [27]. This oxidative damage contributes to both the toxic and carcinogenic effects of arsenic.

Protein Dysregulation Arsenite's affinity for thiol groups allows it to bind and inhibit numerous proteins and enzymes. It specifically binds to thiol group-containing hormone receptors, potentially explaining its diabetogenic effect through inhibition of insulin receptor function [31].

Table 2: Arsenic Species and Their Toxicological Properties

| Arsenic Species | Common Forms | Relative Toxicity | Major Mechanisms | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Trivalent | Arsenite (AsIII) | Highest | Binds to protein thiol groups; inhibits cellular respiration [31] | Groundwater, industrial processes |

| Inorganic Pentavalent | Arsenate (AsV) | High | Replaces phosphate in biochemical reactions [32] | Groundwater, industrial processes |

| Organic Trivalent | MMAIII, DMAIII | High to Moderate | Binds to protein thiol groups; genotoxic [32] | Biological metabolites |

| Organic Pentavalent | MMAV, DMAV | Lower | Limited reactivity; some oxidative stress [31] | Seafood, biological metabolites |

| Elemental Arsenic | As0 | Low | Poor solubility [31] | Environmental dust |

| Arsine Gas | AsH3 | Extreme | Hemolytic agent [28] [31] | Industrial accidents |

Clinical Manifestations of Toxicity

The clinical presentation of arsenic poisoning varies based on exposure duration and intensity:

Acute Toxicity Acute exposure typically presents with gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain) within minutes to hours, followed by hypotension and cardiovascular effects including EKG abnormalities such as QTc prolongation [28]. High-dose exposures can lead to multi-organ failure and death [32].

Chronic Toxicity Chronic exposure affects multiple organ systems, with characteristic dermatological manifestations including hyperpigmentation with "raindrop" appearance, hyperkeratosis of palms and soles, and Mees' lines (transverse white bands on nails) [28]. Neurological effects include sensorimotor polyneuropathy presenting as dysesthesias in a stocking-glove distribution [28]. Other effects include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and various cancers [28] [32].

Carcinogenic Mechanisms and Evidence

Epidemiological Evidence

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies arsenic as a Group I human carcinogen, with strong evidence linking exposure to cancers of the skin, lung, bladder, and kidney [27]. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated increased cancer incidence in populations with elevated arsenic exposure from drinking water, with evidence from Chilean cohorts showing increased lung cancer incidence during high-exposure periods [27]. Similarly, mitigation efforts in Taiwan that reduced arsenic in drinking water subsequently decreased lung cancer rates [27].

Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis

Arsenic carcinogenesis involves multiple complex mechanisms that remain incompletely understood. Current evidence suggests contributions from several interconnected pathways:

Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress Arsenic generates reactive oxygen species that cause DNA damage, including strand breaks and oxidative lesions [27]. Concurrently, arsenic inhibits DNA repair mechanisms, creating a permissive environment for mutations to accumulate [27].

Altered Epigenetic Regulation Arsenic modifies DNA methylation patterns and other epigenetic markers, potentially altering gene expression in ways that promote carcinogenesis [27]. Studies have shown altered methylation of the p53 tumor suppressor promoter in lung cells exposed to arsenic [32].

Altered Cell Signaling and Proliferation A 2025 network-based analysis constructed an adverse outcome pathway framework for arsenic-induced lung cancer, identifying activation of the EGFR and PI3K/AKT pathways as key events leading to dysregulated cell proliferation and lung carcinogenesis [33]. Arsenic can also replace zinc in zinc finger proteins, potentially disrupting transcription factor function and cellular signaling [27].

Cocarcinogenesis and Tumor Promotion Arsenic may act as a cocarcinogen by enhancing the effects of other carcinogens and promoting the growth of initiated cells through altered growth factor expression and chronic cellular proliferation [32].

Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Arsenic Speciation Analysis

The determination of individual arsenic species is critical for accurate toxicity assessment, as different species exhibit markedly different toxicities. Hyphenated techniques combining high-efficiency separation with highly sensitive detection have become the methods of choice [34]. These include:

- High-performance liquid chromatography with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HPLC-ICP-MS) for sensitive element-specific detection

- Hydride generation atomic spectrometry for specific arsenic forms

- Electrospray mass spectrometry for molecular identification

Reliable speciation analysis requires careful methods for extracting arsenic species from solid samples while preserving species integrity, and stabilizing species in solutions to prevent interconversion [34].

Microscale Sampling and Molecular Analysis

Advanced techniques for monitoring arsenic transformation in environmental and biological systems include:

Microscale Sampling of Sediment Profiles High-resolution sampling of sediment layers at millimeter scale near plant root zones allows detailed mapping of arsenic, iron, and microbial activity gradients [30]. This approach reveals the sharp transitions between oxidized and reduced zones that control arsenic mobility.

High-Throughput Genetic Sequencing Comprehensive analysis of microbial community structure and functional genes through 16S rRNA sequencing and metagenomics identifies arsenic-responsive taxa and metabolic pathways [30]. This technique documented an over 80% increase in iron-reducing bacteria following plant death and the subsequent release of arsenic.

Gene Expression Analysis Quantitative assessment of bacterial genes involved in arsenic transformation, including arsenate reductase genes and those responsible for converting toxic arsenic forms to less toxic ones, provides mechanistic insights into arsenic cycling [30].

Diagram 1: Arsenic Metabolism and Carcinogenesis Pathways. This diagram illustrates the metabolic activation of arsenic through sequential reduction and methylation steps, and the multiple interconnected pathways contributing to arsenic carcinogenesis, including oxidative stress, DNA damage, epigenetic alterations, and dysregulated cell proliferation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Arsenic Toxicology Studies

| Research Reagent | Function and Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Ultra-trace quantification of arsenic and other metals in environmental and biological samples [29] | Detection of arsenic in water samples from contaminated areas [29] |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Systems | Separation of arsenic species prior to detection [34] | Arsenic speciation analysis for toxicity assessment [34] |

| High-Throughput Genetic Sequencers | Comprehensive analysis of microbial community structure and functional genes [30] | Identification of arsenic-responsive taxa and metabolic pathways in sediments [30] |

| Microscale Sampling Probes | High-resolution sampling of sediment and water profiles at millimeter scale [30] | Mapping arsenic, iron, and microbial activity gradients in sediment profiles [30] |

| Cell Culture Models (e.g., HBE cells) | In vitro systems for studying arsenic toxicity and transformation mechanisms [33] | Investigation of arsenic-induced malignant transformation in human bronchial epithelial cells [33] |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrometry with Hydride Generation | Sensitive detection of specific arsenic forms [34] | Quantification of inorganic arsenic species in environmental samples [34] |

Diagram 2: Aquatic Plant Mediated Arsenic Cycling. This workflow illustrates the dual role of submerged aquatic vegetation in arsenic dynamics, showing how healthy plants immobilize arsenic through root oxygen release and iron plaque formation, while plant death triggers a cascade of events leading to arsenic mobilization through microbial activity and changing redox conditions.

This case study demonstrates the complex journey of arsenic from natural geological deposits to a systemic toxicant and human carcinogen, with water resources serving as the critical exposure pathway for human populations. The mechanisms underlying arsenic toxicity and carcinogenesis involve multiple interconnected pathways, including metabolic activation, interference with cellular energy production, oxidative stress, genotoxicity, and altered gene expression. Recent research has revealed previously underestimated environmental pathways, particularly the role of aquatic ecosystem health in determining whether sediments function as arsenic sinks or sources. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the dose-response relationships at low exposure levels, clarifying the relative contributions of different carcinogenic mechanisms, and developing integrated strategies for preventing arsenic mobilization in aquatic systems. Protecting and restoring submerged aquatic vegetation emerges as a critical component of comprehensive arsenic risk management in water resources, highlighting the intricate connections between ecosystem health and human toxicological outcomes.

Within the broader study of inorganic pollutant sources and pathways in water resources, nitrate (NO₃⁻) and nitrite (NO₂⁻) represent a pervasive class of contaminants with direct and acute human health implications. These nitrogen-oxygen ions are a natural part of the nitrogen cycle but have become concentrated in water systems globally due to intensive agricultural practices, industrial activities, and sewage discharge [35] [36] [37]. The most well-established and dangerous acute health effect from elevated nitrate/nitrite exposure is methemoglobinemia, a condition that impairs blood oxygen transport. This case study provides an in-depth technical examination of the mechanistic pathway of methemoglobinemia, supported by quantitative exposure data, experimental insights into clinical diagnosis, and an overview of relevant research methodologies.

Nitrate and nitrite enter water resources through multiple pathways, with agricultural activity being the dominant source. The overapplication of nitrogen-based fertilizers and animal manure leads to nitrate leaching into groundwater, particularly in shallow, rural domestic wells [35] [38]. Other significant sources include septic systems, wastewater discharge, and industrial waste [36] [15].

Table 1: Primary Sources of Nitrate and Nitrite in Water Resources

| Source Category | Specific Examples | Key Characteristics & Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural | Nitrogen-based fertilizers (e.g., potassium nitrate, ammonium nitrate), animal manure [35] [38] | Nitrates are highly water-soluble and readily migrate into groundwater; most prevalent in agricultural areas [35]. |

| Wastewater | Septic systems, sewage discharge, landfill leachate [35] [36] [15] | A major problem in areas with high population density, small lot sizes, or inadequate treatment infrastructure [38]. |

| Industrial | Manufacturing processes, boiler fluid additives, food processing (preservatives) [35] [15] | Can involve direct discharge of nitrites or organic nitrogen wastes that are broken down [35]. |

Human exposure occurs predominantly through the consumption of contaminated drinking water and food. For bottle-fed infants, the primary exposure source is contaminated drinking water used to prepare formula [35] [39]. The scale of the problem is significant; a global assessment revealed that during 1970–2010, populations potentially affected by chronic health risks from surface-water nitrate exposure increased from 169 to 1361 million persons per year [37].

Table 2: Typical Nitrate Content in Selected Vegetables (Fresh Weight)

| Vegetable | Nitrate Content (mg/100g) [35] |

|---|---|

| Spinach, Lettuce, Red Beetroot, Celery | Very High (> 2500) |

| Parsley, Leek, Chinese Cabbage | High (1000–2500) |

| Cabbage, Dill, Turnip | Medium (500–1000) |

| Broccoli, Carrot, Cauliflower | Low (200–500) |

| Asparagus, Tomato, Onion, Green Bean | Very Low (< 200) |

The Mechanism of Methemoglobinemia

Methemoglobinemia, commonly known as "blue baby syndrome," is an acute health condition that impairs the blood's oxygen-carrying capacity. The following diagram illustrates the key biochemical pathway and physiological consequences.

Figure 1: Biochemical pathway of nitrate-induced methemoglobinemia.

The mechanism involves a multi-step process triggered after nitrate is ingested and converted to nitrite [39] [37]:

- Ingestion and Conversion: Nitrate (NO₃⁻) is consumed via contaminated water or food. In the gastrointestinal tract, particularly under less acidic conditions or in the presence of certain bacteria, nitrate is reduced to nitrite (NO₂⁻) [37].

- Absorption and Oxidation: Nitrite is absorbed into the bloodstream where it reacts with hemoglobin in red blood cells. Nitrite oxidizes the iron atom in the heme group of hemoglobin from its ferrous state (Fe²⁺) to the ferric state (Fe³⁺), converting hemoglobin to methemoglobin [37].

- Physiological Consequence: Methemoglobin cannot bind oxygen, leading to a reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. This results in tissue hypoxia, the underlying cause of clinical symptoms such as cyanosis (a bluish discoloration of the skin), headache, fatigue, tachycardia, and in severe cases, asphyxia and death [37].

Infants under six months are particularly susceptible due to several factors: larger fluid intake relative to body weight, lower stomach acidity (favoring bacterial reduction of nitrate to nitrite), higher levels of fetal hemoglobin (which is more easily oxidized), and lower activity of the enzyme NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase, which is responsible for reducing methemoglobin back to functional hemoglobin [39] [37].

Quantitative Health Risks and Regulatory Standards

The health risk is directly correlated with the concentration of nitrate/nitrite in drinking water. Regulatory standards are established to prevent methemoglobinemia, though emerging research suggests chronic risks may occur at levels below these standards [37].

Table 3: Health Risk Thresholds and Regulatory Standards for Nitrate/Nitrite in Drinking Water

| Concentration (as Nitrate-Nitrogen, ppm) | Health Risk & Regulatory Status |

|---|---|

| > 3 ppm | Cautionary Level: Suggests potential contamination. Recommendation is to test water periodically to monitor for increasing levels [38]. |

| 10 ppm (45 ppm as nitrate) | EPA Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL): The enforceable regulatory limit for public water systems to prevent methemoglobinemia. Private well owners are strongly advised to take action (e.g., treatment, alternative source) at or above this level [39] [38]. |

| ≥ 47 ppm (as nitrate) | Significant Acute Risk: Populations drinking water at this concentration have a more than doubled daily nitrate intake and face a significantly increased risk of methemoglobinemia [37]. |

A retrospective hospital study identified the most common causes of acquired methemoglobinemia, highlighting that exposure can occur from sources other than drinking water [40]. The most frequent causes included pharmaceuticals like dapsone (an antibiotic) and inhaled nitric oxide (used as a medical therapy). Notably, intentional ingestion of nitrites, either in suicide attempts or recreational use of volatile nitrites ("poppers"), was associated with severe, life-threatening cases [40].

Experimental and Diagnostic Methodologies

Analytical Protocol: Spectrophotometric Measurement of Methemoglobin

The quantitative diagnosis of methemoglobinemia is typically performed on a venous whole blood sample.

Principle: Methemoglobin and hemoglobin have distinct absorption spectra. The concentration of methemoglobin is determined by measuring the absorbance of a hemolysed blood sample at specific wavelengths before and after the addition of cyanide, which converts methemoglobin to cyanmethemoglobin [40].

Reagents:

- Phosphate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.6-7.0)

- Potassium Ferricyanide Solution (K₃[Fe(CN)₆])

- Neutralized Sodium Cyanide (NaCN) Solution *[Warning: Handle with extreme caution; highly toxic.]

- Potassium Phosphate Monobasic (KH₂PO₄) and Sodium Phosphate Dibasic (Na₂HPO₄)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect venous whole blood in a heparinized or EDTA tube. Dilute a precise volume of blood (e.g., 50 µL) in a large volume of phosphate buffer (e.g., 10 mL) to lyse the red blood cells and create a dilute hemolysate.

- Initial Absorbance Scan: Scan the diluted hemolysate from 500-700 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Methemoglobin exhibits a characteristic peak at approximately 630-635 nm.

- Chemical Conversion: Add a small volume of potassium ferricyanide solution to the cuvette to oxidize all hemoglobin derivatives to methemoglobin. Record the absorbance at 635 nm (A₁).

- Cyanide Reaction: Add a small volume of neutralized sodium cyanide to the same cuvette. Cyanide will bind to methemoglobin, forming cyanmethemoglobin and causing the peak at 635 nm to disappear. Wait 2-5 minutes for the reaction to complete.

- Final Absorbance Measurement: Record the final absorbance at 635 nm (A₂).

- Calculation:

- ΔA = A₁ - A₂

- The percent methemoglobin is calculated using a predetermined extinction coefficient for the change in absorbance at 635 nm. Results are often reported as a percentage of total hemoglobin.

Clinical Interpretation: A methemoglobin concentration exceeding 1-2% is considered abnormal. Symptoms typically appear at levels above 10-15%, and concentrations exceeding 50-60% can be fatal [37] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Methemoglobinemia and Nitrate Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Sodium Nitrite (NaNO₂) | Used in in vitro and in vivo models to induce methemoglobinemia and study its biochemical pathway and toxicological effects. |