Land Use Change and Water Quality: Integrating Hydrological Modeling and Remote Sensing for Environmental Impact Assessment

This article synthesizes current research on how land use and land cover (LULC) changes impact hydrological cycles and water quality, with implications for environmental and public health.

Land Use Change and Water Quality: Integrating Hydrological Modeling and Remote Sensing for Environmental Impact Assessment

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on how land use and land cover (LULC) changes impact hydrological cycles and water quality, with implications for environmental and public health. It explores foundational relationships between urbanization, deforestation, and agricultural expansion on hydrological processes and pollutant transport. The review examines advanced methodological approaches including hydrological models (SWAT, HSPF, HEC-HMS), statistical analyses, and remote sensing technologies for detecting and predicting water quality changes. Significant challenges in data integration, model calibration, and scale considerations are addressed, alongside validation frameworks and comparative model performance assessments. This synthesis provides researchers and environmental professionals with evidence-based insights for sustainable land-water management and pollution mitigation strategies.

Understanding the Land-Water Nexus: How LULC Changes Drive Hydrological and Water Quality Impacts

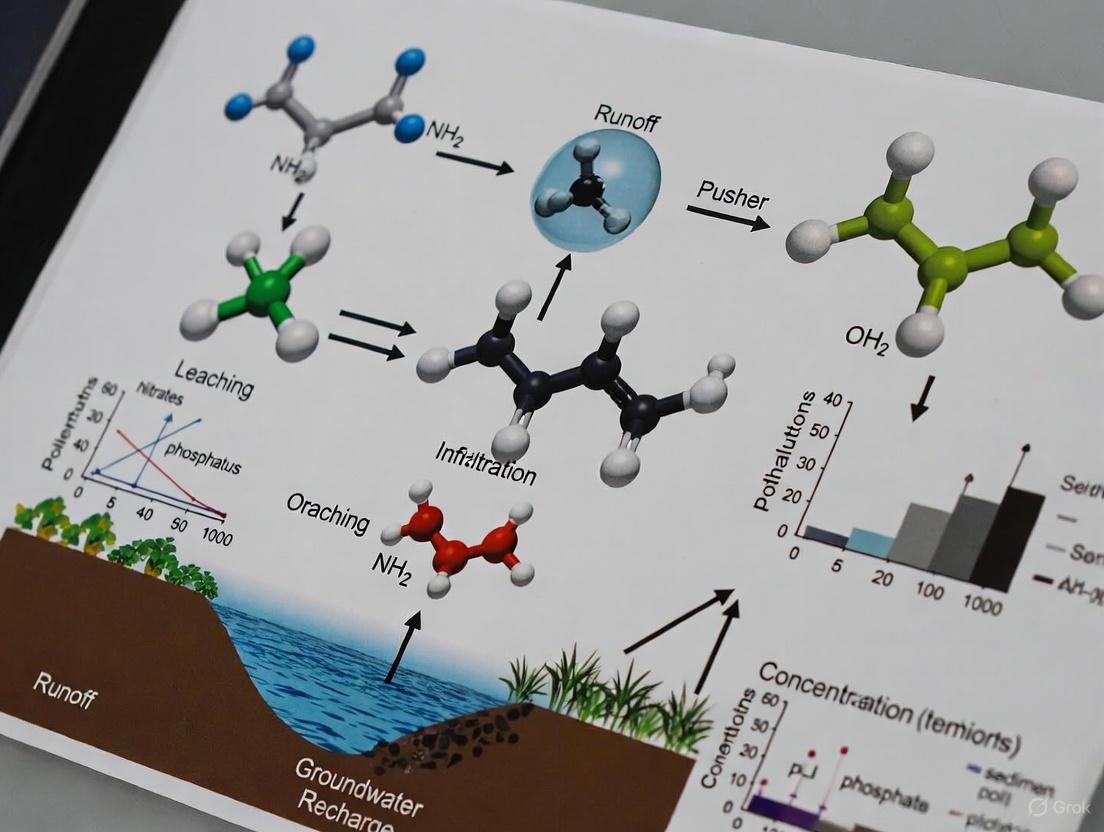

Land use and land cover (LULC) change is a primary driver of alterations in hydrological processes and water quality, representing a critical interface between human activities and the natural environment. Within the context of water quality research, understanding these changes is paramount for predicting contaminant transport, managing water resources, and protecting aquatic ecosystems. The conversion of natural landscapes to urban, agricultural, and other human-modified uses disrupts fundamental hydrological cycles by altering infiltration, evaporation, runoff generation, and groundwater recharge patterns [1]. These hydrological changes subsequently govern the mobilization, transport, and transformation of pollutants in watersheds, directly impacting the quality of water upon which human health and ecosystem functioning depend. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of how three dominant LULC changes—urbanization, deforestation, and agricultural expansion—impact hydrological processes, with specific implications for water quality dynamics essential for researchers and scientists working in water security and environmental management.

Key LULC Changes and Quantitative Hydrological Impacts

Urbanization

Urban expansion replaces natural pervious surfaces with impervious covers such as roads, buildings, and parking lots, fundamentally altering watershed hydrology. These changes directly impact the pathways and efficiency with which pollutants are delivered to water bodies.

- Hydrological Consequences: Increased impervious surface area reduces infiltration and groundwater recharge while significantly enhancing surface runoff generation. This leads to increased peak discharge rates, higher runoff volumes, and reduced baseflow during dry periods [2]. The efficient conveyance of stormwater through drainage networks rapidly delivers stormwater and its pollutant load to receiving waters, often bypassing natural filtration processes.

- Water Quality Implications: Urban runoff carries pollutants including sediments, nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and pathogens [1]. The increased flow velocity and volume also contribute to stream erosion and sediment resuspension. A global meta-analysis found that urban expansion was "most responsible for the deterioration of water quality, more so than agricultural land even in nutrient pollution," with total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and chemical oxygen demand (COD) being highly responsive indicators [3].

Deforestation

The removal of forested areas for timber, agriculture, or settlement disrupts the natural water-regulating functions of vegetative cover, with significant consequences for both water quantity and quality.

- Hydrological Consequences: Deforestation reduces interception, evaporation, and transpiration, leading to increased surface runoff and water yield. It also diminishes soil infiltration capacity and can decrease baseflow and groundwater recharge over time [4]. The loss of root structure reduces soil stability, increasing erosion potential.

- Water Quality Implications: Increased erosion leads to elevated sediment loads in water bodies, degrading aquatic habitats and carrying attached nutrients and pollutants. The reduction in nutrient uptake by vegetation can increase the leaching of nitrogen and phosphorus into groundwater and surface waters [3]. Conversely, reforestation or increased forest cover can significantly improve water quality; one global analysis noted that "increasing forest cover, particularly low-latitude forests, significantly decreased the risk of water pollution, especially biological and heavy metal contamination" [3].

Agricultural Expansion

The conversion of natural landscapes to cropland modifies the physical and chemical properties of the land surface, influencing hydrological pathways and introducing new pollutant sources.

- Hydrological Consequences: The replacement of deep-rooted native vegetation with seasonal crops typically reduces evapotranspiration and can increase water yield and surface runoff, depending on farming practices. Agricultural activities often involve soil compaction and alteration of natural drainage, which can reduce infiltration and increase rapid runoff components [5].

- Water Quality Implications: Agricultural lands are primary non-point sources of nutrient pollution due to fertilizer application. This leads to the eutrophication of freshwater and coastal ecosystems. Pesticides, herbicides, and increased sediment loads are also major water quality concerns [1]. The effect of agricultural land on water quality is spatially scale-dependent, and its impact on nutrient concentrations can sometimes be less pronounced than that of urban areas, as urban sprawl showed the strongest correlation with TP concentration in some studies [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Hydrological Impacts of Documented LULC Changes

| LULC Change | Location | Time Period | Documented Change | Impact on Hydrological Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urbanization | Watershed north of Charlotte, USA [2] | 2021–2080 (Projected) | Urban area: 11.6% → 44.2% | Peak discharge: +6.8% for 100-year storm; Runoff volume: +13.3% |

| Deforestation & Agricultural Transition | Lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia [5] | 2004–2021 | Forest cover: -33.1%; Agricultural land: -10.2% | Surface runoff: +5.8%; Lateral flow: -5.3%; Groundwater recharge: -10.2% |

| Agricultural Expansion & Urbanization | Tropical Regions (Meta-Analysis) [4] | Past decades (60 studies) | Forest loss to agriculture/urban | Streamflow & surface runoff: Increased; Evapotranspiration & groundwater recharge: Decreased |

Table 2: Impact of LULC Changes on Key Water Quality Parameters

| LULC Change | Impact on Total Nitrogen (TN) | Impact on Total Phosphorus (TP) | Impact on Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | Other Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Expansion | Strong Increase [3] | Strong Increase [3] | Strong Increase [3] | Heavy metals, hydrocarbons, pathogens [1] |

| Deforestation | Increase (due to reduced uptake) [3] | Increase (due to reduced uptake & erosion) [3] | Variable | High sediment load, habitat degradation [4] |

| Agricultural Expansion | Increase [3] [1] | Increase [3] [1] | Variable | Pesticides, herbicides, sediment [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing LULC Impacts

A robust assessment of LULC impacts on hydrology and water quality requires an integrated methodological approach combining geospatial analysis, hydrological modeling, and data collection.

Land Use Classification and Change Detection

Objective: To accurately map and quantify spatiotemporal LULC changes. Protocol:

- Image Acquisition: Acquire cloud-minimized satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) for different epochs from platforms like USGS Earth Explorer [5].

- Pre-processing: Perform layer stacking of relevant spectral bands and mosaicking to cover the study area [5].

- Hybrid Classification: Employ a combined unsupervised and supervised classification approach.

- First, perform unsupervised classification (e.g., ISODATA) to generate spectral clusters.

- Then, visually interpret clusters using high-resolution imagery from Google Earth for accurate labeling into LULC classes (e.g., water, agriculture, forest, urban) [5].

- Accuracy Assessment: Generate stratified random points and compare the classified map with reference data. Calculate overall accuracy, Cohen’s kappa, and user's/producer's accuracies. An overall accuracy >85% is typically targeted [5].

- Change Detection: Perform post-classification comparison to produce a change matrix and maps highlighting transitions between classes over time.

Hydrological and Water Quality Modeling

Objective: To simulate the hydrological response and water quality dynamics under different LULC scenarios. Protocol (using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool - SWAT):

- Watershed Delineation: Input a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to automatically delineate watershed boundaries, sub-basins, and river networks [5].

- HRU Definition: Overlay LULC maps, soil data, and slope information to define Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs)—the unique, spatially distributed land units used for simulating hydrological processes [5].

- Weather Data Integration: Input time-series data for precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, wind, and humidity [5].

- Model Calibration and Validation:

- Use an algorithm such as SUFI-2 for sensitivity analysis, calibration, and uncertainty analysis.

- Calibrate the model using observed streamflow and water quality data (e.g., sediment, nutrients) for a specific period.

- Validate the model using an independent period of observed data without changing the calibrated parameters.

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate using Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE > 0.7 is generally satisfactory), Coefficient of Determination (R² > 0.7), and Percent Bias (PBIAS ±15% for streamflow) [5] [1].

- Scenario Simulation: Run the calibrated model with different LULC maps (e.g., historical vs. current, or current vs. future) while keeping climate data constant to isolate the effect of LULC change on water balance components and pollutant loads [5].

Future LULC Projection

Objective: To forecast future LULC scenarios for predictive impact assessment. Protocol (using the CA-Markov Model):

- Transition Matrix Calculation: Use historical LULC maps (e.g., from 2001 and 2013) to compute a transition probability matrix, which defines the likelihood of a land use cell changing from one class to another [2].

- Suitability Map Generation: Identify driving factors of change (e.g., distance to roads, slope, elevation) and use a model like Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) within a FLUS model, or a regression in CA-Markov, to create suitability maps for each LULC class [1] [2].

- Future Simulation: Integrate the transition probabilities and suitability maps within a Cellular Automata (CA) framework to simulate spatial changes over iterative time steps, projecting future LULC maps (e.g., for 2050, 2080) [2].

- Model Validation: Validate the projected model by simulating a known year (e.g., 2021) and comparing it with the actual LULC map [2].

This section details key datasets, models, and tools essential for conducting research on LULC change and its hydrological impacts.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Application in LULC-Hydrology Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite Data | Landsat (USGS Earth Explorer) [5] | Medium-resolution multispectral imagery | Primary data source for historical and contemporary LULC classification and change detection. |

| Hydrological Models | SWAT (Soil & Water Assessment Tool) [5] | Semi-distributed, continuous-time watershed model | Simulating long-term impacts of LULC change on water balance, sediment, and nutrient loads. |

| HSPF (Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN) [1] | Integrated hydrological and water quality model | Simulating watershed hydrology and water quality for various LULC and climate scenarios. | |

| Land Use Projection Models | CA-Markov Model [2] | Hybrid cellular automata and Markov chain model | Predicting future land use patterns based on transition probabilities and suitability maps. |

| FLUS (Future Land Use Simulation) [1] | Land use simulation model using ANN and CA | Simulating future land use change under human and natural influences. | |

| Geospatial Data | HydroSHEDS [6] | Global hydrographic data layers (catchments, rivers) | Providing the foundational geospatial framework for hydrological assessments and modeling. |

| WorldClim Bioclimatic Variables [7] | Derived temperature and precipitation variables | Providing historical and contemporary climate data for hydrological modeling inputs. | |

| Ancillary Data | LandScan Global Population Data [8] | High-resolution global population distribution | Used as a proxy for anthropogenic pressure and as a driver in urban growth models. |

The expansion of impervious surfaces—such as roofs, roads, and parking lots—is a fundamental characteristic of urbanization that directly disrupts the natural water cycle. These surfaces alter the partitioning of precipitation, leading to profound changes in the key hydrological processes of runoff, infiltration, and evapotranspiration (ET). Understanding these mechanisms is critical for water resources management, flood mitigation, and water quality protection. This technical guide examines the physical processes through which impervious surfaces transform watershed hydrology, framed within the broader context of land use and water quality research. As global urban populations are projected to exceed 70% by 2050, these interactions become increasingly central to sustainable environmental planning [9].

Theoretical Framework: From Precipitation to Partitioning

In natural landscapes, precipitation is partitioned primarily into infiltration, evapotranspiration, and shallow subsurface flow, with minimal surface runoff. Impervious surfaces fundamentally alter this balance by creating a barrier between precipitation and the soil matrix. This disruption converts previously infiltrative surfaces into conductive channels, accelerating the movement of water through watersheds while simultaneously reducing vital groundwater recharge and evapotranspiration processes [9] [10] [11].

The hydrological impact of an impervious surface is governed not merely by its presence but by its hydraulic connectivity to drainage systems. This has led to the critical distinction between:

- Total Impervious Area (TIA): The total area covered by impervious surfaces.

- Effective Impervious Area (EIA): The subset of TIA that is directly connected to drainage systems via pipes, channels, or gutters.

- Non-Effective Impervious Area (NEIA): Impervious areas where runoff drains onto pervious areas before reaching streams or drainage systems [9].

Research confirms that EIA is a more accurate predictor of hydrological alteration than TIA, as it represents the portion of impervious cover that most directly generates rapid runoff [9].

Table 1: Key Terminology in Urban Hydrology

| Term | Definition | Hydrological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Impervious Area (EIA) | Impervious surfaces directly connected to drainage systems | Directly generates runoff to streams; primary driver of hydrologic change |

| Non-Effective Impervious Area (NEIA) | Impervious surfaces that drain to pervious areas | Runoff is subject to infiltration and retention on pervious areas |

| Receiving Pervious Area (RPA) | Pervious area that receives runoff from disconnected impervious areas | Provides natural buffer through infiltration and temporary storage |

| Infiltration | Process of water entering the soil matrix | Recharges groundwater; reduces surface runoff volume |

| Evapotranspiration (ET) | Combined process of evaporation and plant transpiration | Returns water to atmosphere; reduces total runoff |

Quantifying the Hydrological Impacts

Runoff Dynamics and Peak Flow

Impervious surfaces dramatically increase both the volume and velocity of surface runoff. Where forested or rural landscapes might generate only 10% of precipitation as runoff, urban areas with extensive impervious cover can convert 30-55% of precipitation into immediate runoff [10]. This occurs because impervious surfaces have negligible storage capacity and prevent water from infiltrating into soils.

The impact on peak flow rates is particularly significant. One catchment-scale modeling study found that disconnecting effective impervious areas (thereby converting EIA to NEIA) could reduce peak flow by up to 28.1% and runoff depth by 43.9% for frequent storms (less than 5-year return period). However, this effectiveness diminished for extreme events, with maximum reductions of only 13.6% for peak flow and 24.7% for runoff depth in storms exceeding 5-year return periods [9].

Table 2: Impact of Effective Impervious Area Disconnection on Runoff

| Return Period | Maximum Peak Flow Reduction | Maximum Runoff Depth Reduction | Key Conditioning Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 5-year | 28.1% | 43.9% | High infiltration capacity of RPA |

| > 5-year | 13.6% | 24.7% | Limited by storage capacity of RPA |

| 50-100 year | Increase observed | 1.9% | Low infiltration scenarios show negative impacts |

Infiltration and Groundwater Recharge

By creating a physical barrier to water entry, impervious surfaces can reduce infiltration by 90-100% in directly covered areas [10]. This reduction has cascading effects on groundwater recharge and baseflow in streams. In the Wei River Basin in China, land use changes including urbanization led to a 5.3% decrease in water yield and 6.2% increase in soil water content due to vegetation changes, but with complex spatial patterns based on specific land conversions [12].

The infiltration process is controlled by multiple factors including soil characteristics (texture, structure, compaction), antecedent soil moisture conditions, storm intensity and duration, and temperature. Soils with higher bulk density typically exhibit lower infiltration rates, while layered soils with restrictive layers can dramatically limit infiltration capacities [10].

Evapotranspiration Patterns

Urbanization typically reduces evapotranspiration due to the loss of vegetation and the rapid export of water via drainage systems. However, the relationship is complex, as irrigation of urban vegetation can sometimes increase ET in certain settings. In the Yanhe watershed on China's Loess Plateau, land-use changes featuring conversion of cropland to grassland and forestland resulted in increased evapotranspiration—by 209% in some sub-basins—demonstrating the significant influence of vegetative cover on this process [13].

The reduction in ET from impervious surfaces creates a positive feedback loop for thermal pollution, as available water is not used for cooling through evaporation. One study found asphalt surfaces averaged 18°C warmer than grasslands or vegetated ponds in mid-summer months, leading to elevated runoff temperatures that can impact receiving waters [14].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Watershed-Scale Hydrological Modeling

Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) Protocol SWAT is a semi-distributed, physically-based river basin model that can simulate hydrological processes under varying land use conditions [12] [13].

Watershed Delineation: Divide the watershed into multiple sub-basins based on digital elevation model (DEM) data, incorporating stream networks and outlet points.

Hydrological Response Units (HRUs) Definition: Overlay land use, soil type, and slope datasets to create HRUs—areas with homogeneous land use, soil, and slope characteristics.

Weather Data Input: Input historical climate data including precipitation, temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, and relative humidity at daily or sub-daily time steps.

Model Calibration and Validation: Use streamflow data to calibrate model parameters through an iterative process, followed by validation using an independent data period. Statistical measures like coefficient of determination (R²), percent bias (PBIAS), and Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency are used to evaluate performance [1].

Scenario Simulation: Develop alternative land use scenarios to quantify hydrological impacts. For example, compare current impervious conditions with pre-urbanization scenarios or test the effects of various impervious surface disconnection strategies [12].

Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) Protocol SWMM is widely used for urban hydrology studies, particularly for analyzing the effects of impervious surface disconnection [9].

Catchment Discretization: Divide the study area into sub-catchments representing homogeneous land units.

Land Surface Representation: Model the land surface as a combination of pervious and impervious sub-areas, with and without depression storage.

Flow Routing Configuration: Set up flow pathways between connected impervious areas, pervious areas, and drainage infrastructure.

Parameterization: Define key parameters including imperviousness percentage, width, slope, depression storage, Manning's n, and infiltration characteristics (e.g., Horton or Green-Ampt parameters).

Scenario Analysis: Model multiple scenarios including different disconnection rates, infiltration conditions, and rainfall return periods to assess their impacts on hydrographs.

Field Measurement Techniques

Infiltration Rate Measurement

- Double-Ring Infiltrometer Method: Use concentric rings driven into the soil; water is maintained at a constant level in both rings, with the inner ring providing the measurement of vertical infiltration while the outer ring minimizes lateral divergence.

- Modified Philip-Dunne Permeameter: A single-ring falling-head permeameter that measures saturated hydraulic conductivity through analysis of the falling head data.

- Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity (Ksat): Measurements should be taken at fully saturated conditions for conservative design estimates [10].

Evapotranspiration Quantification

- Eddy Covariance Method: Directly measure vertical fluxes of water vapor using high-frequency sensors mounted above the canopy.

- Lysimeters: Precise weighing containers that measure ET through changes in mass of a soil-vegetation system.

- Remote Sensing Approaches: Utilize satellite-derived indices (e.g., NDVI) with energy balance models to estimate ET at watershed scales.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Urban Hydrology Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool) | Watershed-scale model for simulating hydrology under changing land use | Semi-distributed, continuous time model; uses HRUs; public domain software |

| SWMM (Storm Water Management Model) | Urban drainage simulation; ideal for impervious surface disconnection studies | EPA-developed; dynamic rainfall-runoff simulation; green infrastructure module |

| HSPF (Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN) | Integrated watershed model for hydrology and water quality | Continuous, lumped parameter model; modules for pervious/impervious land segments |

| Double-Ring Infiltrometer | Field measurement of saturated hydraulic conductivity | Two concentric metal rings (30cm & 60cm diameter); constant head maintenance |

| FLUS (Future Land Use Simulation) Model | Land use change prediction under human and natural influences | Integrates system dynamics and cellular automata; uses artificial neural network |

| Landsat Imagery | Land use/cover classification and change detection | 30m resolution multispectral; historical archive since 1972 for change analysis |

| Eddy Covariance System | Direct measurement of evapotranspiration fluxes | High-frequency 3D sonic anemometer and infrared gas analyzer; tower-mounted |

Mitigation Strategies and Management Implications

Impervious Surface Disconnection

The disconnection of effective impervious areas represents a primary strategy for restoring natural hydrologic functions. This approach redirects runoff from paved surfaces to receiving pervious areas (RPA), where it can infiltrate rather than immediately entering drainage systems [9]. The effectiveness of this strategy depends critically on:

- Infiltration capacity of RPA: High-infiltration scenarios can reduce peak flows by up to 28.1%, while low-infiltration scenarios show minimal impact (1.9-2.5% reduction) [9].

- Depression storage capacity: Increasing depression storage of RPAs can reduce peak flow and runoff depth by 39.0% and 49.2% respectively, even under 100-year return period storms [9].

- Spatial scale and distribution: Distributed, small-scale disconnection practices throughout a watershed provide more effective runoff reduction than centralized approaches [10].

Low Impact Development (LID) Practices

LID emphasizes site-design strategies that protect natural hydrologic functions through distributed, small-scale practices [15]. Key approaches include:

- Permeable pavements: Alternative paving systems that allow infiltration through the surface.

- Rain gardens/bioretention systems: Shallow depressions with engineered soils and vegetation that treat and infiltrate runoff.

- Green roofs: Vegetated roof systems that retain precipitation and promote ET.

- Vegetated swales: Open channels that reduce runoff velocity and promote infiltration compared to traditional storm drains.

Impervious surfaces fundamentally alter hydrological processes by increasing runoff volume and velocity, decreasing infiltration and groundwater recharge, and modifying evapotranspiration patterns. The magnitude of these impacts depends not merely on the total impervious area but on its hydraulic connectivity to drainage systems. Effective impervious area disconnection and Low Impact Development strategies can significantly mitigate these impacts by restoring natural hydrologic pathways, though their effectiveness is highly dependent on soil conditions, climate, and spatial implementation.

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for future water quality research, particularly as urban expansion continues globally. The interaction between land use changes and hydrological cycles represents a critical frontier in developing sustainable approaches to water resources management that balance human needs with ecosystem protection.

The interaction between land use activities and hydrological cycles is a fundamental determinant of water quality in aquatic ecosystems. Within the context of water quality research, understanding the specific pathways through which pollutants travel from terrestrial environments to water bodies is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies. Land use and land cover (LULC) significantly alter natural hydrologic processes, thereby modifying the transport mechanisms of sediments, nutrients, and contaminants through watershed systems [16]. The hydrologic cycle describes the continuous movement of water above, on, and below the Earth's surface, serving as the primary medium for pollutant transport from terrestrial to aquatic systems [17] [18]. This complex interplay means that human modifications to the landscape—whether through urbanization, agriculture, or forest conservation—directly influence the quality of water resources through well-defined physical, chemical, and biological pathways.

The pathways connecting land activities to water quality are not merely theoretical constructs but represent tangible processes that can be quantified, modeled, and managed. As human pressures on water resources intensify due to population growth and climate change, elucidating these mechanisms becomes increasingly vital for protecting drinking water supplies, maintaining ecosystem health, and informing sustainable land use policies [19] [20]. This technical guide examines the key mechanisms, pollutant-specific pathways, and methodological approaches for investigating connections between land use and water quality parameters, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for assessing these critical relationships.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Pollutant Transport

Hydrologic Pathways and Processes

The transport of pollutants from land to water occurs through several interconnected hydrologic pathways, each with distinct characteristics and implications for water quality. These pathways are governed by the basic principles of watershed hydrology, where water moves from areas of higher elevation to lower elevation, collecting and transporting contaminants along its flow path.

Surface Runoff and Subsurface Flow: Precipitation that does not infiltrate into the soil becomes surface runoff, which represents the most direct and rapid pathway for pollutant transport to water bodies [21]. The proportion of rainfall that becomes runoff versus infiltration is heavily influenced by land surface characteristics, particularly impervious surfaces in urban areas and soil compaction in agricultural regions. In a natural landscape with forest or grassland cover, typically less than 0.5 inches of runoff is generated from a 4-inch rainfall event, whereas paved surfaces can produce nearly 3.9 inches of runoff from the same event [21]. This amplified surface runoff from developed areas carries pollutants directly to streams via storm drainage systems, largely bypassing the natural filtration capacity of soils.

Subsurface flow pathways include shallow interflow through the soil layer and deeper groundwater movement. While these pathways generally move more slowly than surface runoff, they can transport dissolved contaminants over considerable distances and time scales [17]. Groundwater flow paths may vary from tens of feet with travel times of days to tens of miles with travel times of millennia [17]. This delayed connectivity means that land use impacts on groundwater quality may manifest years or even decades after contaminant introduction, creating significant challenges for management and remediation.

Land Use Controls on Hydrologic Processes

Land use alterations fundamentally change the watershed hydrology that drives pollutant transport. The conversion of natural vegetation to urban or agricultural land modifies key hydrologic processes including interception, infiltration, evaporation, and runoff generation. These changes subsequently affect the timing, magnitude, and chemical characteristics of pollutant delivery to aquatic systems.

Impervious Surfaces and Hydrologic Modification: Urbanization creates impervious surfaces (roads, parking lots, rooftops) that prevent infiltration and dramatically increase surface runoff volume and velocity [21]. Commercial developments can generate more than 20 times the annual runoff volume compared to forested land [21]. This increased runoff volume is coupled with faster concentration times, as storm sewer systems efficiently channel runoff directly to streams rather than allowing gradual movement through soil and groundwater pathways. The resulting "flashier" hydrology leads to more frequent bankfull flows, channel erosion, and reduced baseflow during dry periods—all of which negatively impact water quality and aquatic habitat.

Soil Infiltration and Groundwater Recharge: Natural landscapes promote infiltration, which serves as a critical filtration mechanism for improving water quality. As water percolates through soil layers, pollutants are physically filtered, chemically transformed, and biologically degraded through microbial activity [21]. Land uses that compact soils or remove vegetation reduce this natural water treatment capacity. Reduced infiltration also diminishes groundwater recharge, which in turn decreases the baseflow that sustains streamflow during dry periods and dilutes pollutants during low-flow conditions [21].

Table 1: Runoff Characteristics Across Land Use Types

| Land Use Type | Runoff from 4-inch Rainfall (inches) | Runoff Volume from 1 Acre (gallons) | Average Annual Runoff (inches) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | 0.5 | 13,600 | 0.3 |

| Grass/Meadow | 0.8 | 21,700 | 0.4 |

| Agricultural Cropland | 2.0 | 54,300 | 1.1 |

| Residential (1/4-acre lots) | 1.7 | 46,200 | 1.1 |

| Industrial | 2.7 | 73,350 | 4.1 |

| Commercial | 3.7 | 105,900 | 19.0 |

| Roofs/Pavement | 3.9 | 105,900 | 19.0 |

Land Use Specific Pollutant Pathways

Agricultural Land Uses

Agricultural activities represent significant sources of water quality impairment through distinct pollutant pathways. The primary contaminants of concern from agricultural lands include nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), sediments, pesticides, and organic matter.

Nutrient Pathways: Agricultural operations contribute to nutrient pollution through the application of synthetic fertilizers, manure, and leguminous crops. These nutrients follow hydrologic pathways to water bodies, with nitrogen primarily moving in dissolved forms through subsurface drainage and groundwater flow, while phosphorus tends to bind to soil particles and transport via surface erosion [19] [20]. In the Naoli River Basin, dominated by agricultural land use, monitoring revealed high concentrations of total nitrogen (TN), nitrate (NO₃⁻), and ammonium (NH₄⁺), particularly during the dry season [20]. The study found that paddy fields and building areas showed strong correlations with nutrient concentrations and chlorophyll-a, indicating their role in nutrient-driven eutrophication processes.

Sediment Pathways: Soil erosion from cultivated fields represents a major sediment pathway, particularly in row crop production systems with seasonal bare soils. Sediment delivery to water bodies occurs through sheet, rill, and gully erosion processes during precipitation events, with transport efficiency influenced by slope, soil characteristics, and distance to waterways. Beyond the direct impacts of turbidity and sedimentation, sediment particles serve as carriers for adsorbed phosphorus, pesticides, and other hydrophobic contaminants [19].

Urban and Residential Land Uses

Urban and developed areas generate distinct pollutant profiles and transport pathways characterized by efficient delivery systems through stormwater infrastructure.

Stormwater Runoff Pathways: Urban pollutants accumulate on impervious surfaces between rainfall events and are rapidly mobilized during storm events. Key contaminants include heavy metals from vehicle wear (zinc, copper, lead), hydrocarbons from petroleum products, nutrients from lawn fertilizers, pathogens from animal waste, and sediment from construction activities [21] [20]. Unlike agricultural systems where pollutants often originate from diffuse sources, urban pollutants frequently concentrate at "hot spots" such as industrial facilities, high-traffic areas, and construction sites.

Specific Residential Development Pathways: A study of residential areas in Hangzhou City revealed that building density and green space ratio were core factors affecting pollutant concentrations in surface waters [22]. Ammonia nitrogen (NH₃-N) and total phosphorus (TP) were identified as the most significantly impacted water quality parameters across different residential types. The research established specific threshold relationships, finding that the maximum unit density should be limited to 135 units/hectare for multi-story residential areas, 196 units/hectare for small high-rise, and 190 units/hectare for high-rise residential areas to effectively control pollution [22].

Atmospheric Deposition and Cross-Boundary Pathways

While often overlooked, atmospheric deposition represents a significant pathway for certain pollutants to enter water bodies, particularly in sensitive ecosystems. Atmospheric nitrogen compounds from agricultural ammonia volatilization and fossil fuel combustion can be transported long distances before deposition onto land and water surfaces. Similarly, mercury and other volatile contaminants can circulate globally before deposition in watersheds. In island systems like Mo'orea, French Polynesia, research has demonstrated that nutrient concentrations in lagoons were consistently highest close to shore and diminished with distance offshore, linked directly to terrestrial runoff from human-impacted watersheds [23].

Quantitative Relationships and Modeling Approaches

Statistical Relationships Between Land Use and Water Quality

Quantifying the relationships between land use patterns and water quality parameters enables predictive modeling and threshold identification for management interventions. Statistical analyses across multiple studies have revealed consistent patterns in these relationships.

Spatial and Temporal Scaling Effects: The influence of land use on water quality varies significantly with spatial scale, with generally stronger correlations at smaller watershed scales where connectivity between land and water is more direct [16]. Temporal variability also affects these relationships, with studies in the Songliao River Basin demonstrating notable seasonal variation in water quality parameters, including substantially higher concentrations of TN, NO₃⁻, and NH₄⁺ in the dry season [20].

Nonlinear Responses and Threshold Effects: Research increasingly indicates that land use-water quality relationships are often nonlinear, with potential threshold effects beyond which water quality degradation accelerates dramatically. A comprehensive review highlighted that water quality significantly deteriorates when the proportion of arid farmland exceeds 54% [20]. Similarly, studies of residential areas have identified specific thresholds for development intensity indicators beyond which water quality standards cannot be maintained [22].

Table 2: Key Water Quality Parameters and Their Primary Land Use Associations

| Water Quality Parameter | Primary Associated Land Uses | Transport Pathway | Ecological and Human Health Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | Agricultural, Residential | Subsurface flow, Surface runoff | Eutrophication, hypoxia, methemoglobinemia |

| Total Phosphorus (TP) | Agricultural, Urban | Surface runoff with sediment | Eutrophication, algal blooms |

| Total Suspended Solids (TSS) | Construction, Agricultural, Urban | Surface erosion | Habitat destruction, gill damage, contaminant carrier |

| Ammonia Nitrogen (NH₃-N) | Residential, Agricultural | Direct discharge, Surface runoff | Fish toxicity, oxygen demand |

| Heavy Metals (As, Pb, Hg) | Industrial, Urban, Mining | Surface runoff, Atmospheric deposition | Neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, bioaccumulation |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | Urban, Agricultural | Surface runoff, Point sources | Oxygen depletion, fish kills |

Predictive Modeling Using the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)

The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) is a widely employed semi-distributed hydrologic model that simulates the impact of land management practices on water, sediment, and agricultural chemical yields in complex watersheds [19]. SWAT integrates spatial data including digital elevation models (DEMs), soil types, land use classifications, and weather data to predict water quality responses to changing land use patterns.

Model Application and Findings: A SWAT analysis of the Middle Chattahoochee watershed projected that forest conversion to development would result in higher average annual concentrations of total suspended sediment (TSS) and total nitrogen (TN) at 13 out of 15 drinking water intake facilities, with potential increases of up to 318% for sediment and 220% for nitrogen [19]. Conversely, concentrations decreased relative to baseline when upstream agricultural land was converted to forest cover or new, low-intensity development. The model also predicted that extreme nitrogen and sediment concentration events could become 3.6 to 6.6 times more frequent under future development scenarios [19].

Methodological Framework: The SWAT modeling approach involves watershed delineation into subbasins, further division into Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs) with homogeneous land use, soil, and slope characteristics, simulation of hydrologic processes including pollutant transport for each HRU, and routing of water and contaminants through the stream network to the watershed outlet [19]. This methodology enables researchers to test multiple land use scenarios and predict their effects on specific water quality parameters at critical locations such as drinking water intakes.

Experimental Methodologies and Research Protocols

Watershed-Scale Monitoring Designs

Comprehensive watershed monitoring programs employ spatially and temporally distributed sampling strategies to capture variability in water quality parameters across different land use types and hydrological conditions.

Spatial Sampling Design: Effective monitoring requires strategic site selection across gradients of human impact. The Songliao River Basin study implemented a balanced design with 39 sampling sites across three river systems with varying land use patterns, including sites along upstream, middle, and downstream reaches to capture spatial variability [20]. Similarly, the Mo'orea study included nearly 200 sites circling the island to establish land-sea connections [23]. Sampling points should be selected to represent specific sub-watersheds with relatively homogeneous land use characteristics to establish clear land-water relationships.

Temporal Sampling Frequency: Seasonal variability necessitates sampling across different hydrological conditions. The Songliao River Basin study conducted field observations in September (wet season), December (dry season), and June (agricultural season) to capture temporal variations in water quality parameters [20]. This approach revealed significantly different pollutant concentrations and relationships with land use across seasons, highlighting the importance of temporal replication in study designs.

Multiparameter Water Quality Assessment: Comprehensive assessment requires measurement of diverse water quality parameters, including physical (temperature, turbidity, suspended solids), chemical (nutrients, heavy metals, oxygen demand), and biological (chlorophyll-a, microbial communities) indicators [20] [23]. Advanced statistical techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Redundancy Analysis (RDA) help identify patterns and relationships within complex multivariate datasets [20].

Landscape Pattern Analysis

Beyond simple land use percentages, the spatial configuration of land cover features significantly influences their impact on water quality through effects on hydrological connectivity and pollutant retention.

Landscape Metrics Quantification: Studies employ geographic information systems (GIS) and landscape ecology metrics to quantify spatial patterns of land use. Research in Hangzhou City calculated eleven land use metrics to indicate land use function, utilization intensity, and spatial structure characteristics across different residential types [22]. Key metrics included set density, green space ratio, fragmentation of green space, and degree of green space dominance and aggregation.

Threshold Determination: Nonlinear regression models (power, exponential, cubic) can establish relationships between landscape metrics and water quality parameters, enabling identification of management thresholds [22]. This approach allows researchers to determine specific development limits—such as maximum impervious surface percentages or minimum green space ratios—necessary to maintain desired water quality standards.

Research Toolkit: Analytical Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Methods for Water Quality Analysis

| Analysis Type | Key Reagents/Solutions | Instrumentation | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Analysis (TN, TP, NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) | Persulfate digestion reagents, Cadmium reduction columns, Nessler reagent, Ascorbic acid method reagents | Spectrophotometer, Flow injection analyzer, Continuous flow analyzer | Quantify nutrient concentrations from agricultural and urban runoff |

| Heavy Metal Analysis | Nitric acid for digestion, APDC chelating reagent, Certified reference materials | ICP-MS, ICP-OES, Graphite furnace AAS | Detect trace metal contamination from industrial and urban sources |

| Sediment Analysis | Hydrogen peroxide (organic matter removal), Sodium hexametaphosphate (particle dispersion) | Laser particle size analyzer, Gravimetric filtration system | Characterize sediment loads and particle size distribution |

| Chlorophyll-a Analysis | Acetone or methanol extraction solvents, Magnesium carbonate suspension | Fluorometer, Spectrophotometer | Assess algal biomass and eutrophication status |

| Microbial Community Analysis | DNA extraction kits, PCR reagents, Sequencing primers | Next-generation sequencer, Thermal cycler | Characterize microbial responses to land-based nutrient inputs |

| Oxygen Demand Parameters | Potassium dichromate (COD), Manganese sulfate (DO), Alkali-iodide-azide (DO) | Titration system, COD reactor, DO meter | Assess organic pollution loading from watersheds |

Understanding pollutant pathways from land use activities to water quality parameters provides a scientific foundation for integrated watershed management strategies. Research consistently demonstrates that land use decisions directly influence water quality through measurable hydrologic and biogeochemical pathways, with implications for drinking water treatment costs, ecosystem health, and compliance with regulatory standards [19] [20].

The spatial and temporal complexity of these relationships necessitates watershed-specific assessments coupled with targeted management interventions. Forest conservation emerges as a particularly effective strategy for protecting water quality, with studies demonstrating that forest cover maintains lower sediment and nutrient concentrations compared to other land uses [19]. Conversely, the conversion of forests to development or intensive agriculture consistently degrades water quality, with impacts persisting decades after land use change.

Future research should address persistent knowledge gaps regarding scale-dependent relationships, the significance of landscape configuration, land use thresholds, and confounding influences of climate variability [16]. Additionally, geographical biases in existing literature highlight the need for expanded research in ecologically and climatically disparate regions, particularly in developing countries of the Global South [16]. As climate change alters precipitation patterns and intensifies extreme weather events, the pathways connecting land use to water quality will likely amplify, making this research domain increasingly critical for ensuring water security and ecosystem sustainability.

Spatiotemporal dynamics form the cornerstone of understanding complex land-water interactions, particularly within the broader thesis investigating the interplay between land use and hydrological cycles in water quality research. The effects of human activities and natural processes on water resources are not uniform across time and space; they manifest differently depending on the scale of observation and analysis. Recognizing these scale dependencies is crucial for developing accurate predictive models and effective watershed management strategies. This technical guide examines the multifaceted nature of spatiotemporal scaling in land-water systems, providing researchers with methodologies and analytical frameworks to address scale-related challenges in water quality research. The intricate relationships between land use patterns and hydrological responses necessitate a sophisticated approach to quantifying and modeling these interactions across multiple temporal and spatial dimensions—an approach fundamental to advancing sustainable water resource management in an era of global environmental change.

Conceptual Foundations of Scale Dependence

Scale dependence in land-water interactions arises from the inherent heterogeneity of environmental systems and the non-linear nature of hydrological processes. The spatial and temporal scales at which measurements are taken and analyses performed significantly influence research outcomes and management recommendations.

Spatial Scaling Considerations

Spatial scale effects profoundly influence the observed relationships between land use and water quality parameters. Research conducted across urban rivers in northern China demonstrates that the statistical explanatory power of land use types on water quality variation changes dramatically with spatial scale [24]. Buffer zones immediately adjacent to river networks often show the strongest correlations with water quality parameters, while catchment-scale analyses may reveal different driving factors. This scale-dependent relationship necessitates careful consideration when designing studies and interpreting results.

The spatial heterogeneity of land surface characteristics generates significant variability in water and energy partitioning [25]. Atmospheric forcing (particularly precipitation and temperature) and land use/land cover constitute the most dominant sources of spatial heterogeneity affecting water and energy fluxes [25]. These heterogeneity sources exhibit complementary effects both spatially and temporally, with their relative importance shifting across different biogeographic regions and climate zones.

Temporal Scaling Considerations

Temporal scaling considerations encompass both short-term event-based dynamics and long-term trend analyses. The temporal resolution of monitoring (e.g., hourly, daily, seasonal, or annual) significantly influences the detection of cause-effect relationships in land-water systems. For instance, the impact of land use on river water quality differs by season, with nitrogen levels in river waters during dry seasons indicating potential purification within small buffer zones along partial river sections [24].

Climate change introduces additional temporal complexity through alterations to precipitation patterns, extreme event frequency, and seasonal hydrological cycles [26]. These changes interact with land use modifications, creating evolving baselines that complicate trend detection and attribution. Understanding the joint impacts of climate change and human activities on hydrological processes across temporal scales represents a critical research frontier [26].

Methodological Approaches for Multi-Scale Analysis

Experimental Designs for Scale-Dependent Relationships

Elucidating scale-dependent relationships requires carefully constructed experimental designs that incorporate hierarchical sampling strategies and multi-model inference approaches.

Table 1: Spatial Scales for Assessing Land-Water Interactions

| Spatial Scale | Typical Applications | Key Measured Parameters | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer Zone (10-100m riparian) | Water chemistry immediate land effects | Nitrogen, phosphorus, major ions | Misses catchment-scale processes |

| Sub-catchment (1-10 km²) | Source identification, targeted management | Sediment loads, nutrient speciation | Boundary effects, cross-boundary transfers |

| Catchment/Basin (>100 km²) | Cumulative impact assessment, policy planning | Water yield, total nutrient loads | Oversimplification of internal heterogeneity |

| Regional (>10,000 km²) | Climate change impact, broad trends | Water availability, land-atmosphere feedbacks | Generalization of local processes |

Research in the Great Barrier Reef catchments demonstrates the utility of multi-model inference approaches that consider evidence from multiple plausible models with comparable predictive power, rather than relying on a single "best" model [27]. This approach provides more robust predictions and a more comprehensive understanding of the key drivers affecting spatial variability in water quality.

Modeling Techniques and Framework Integration

Advanced modeling techniques enable researchers to address scale challenges through mathematical representation of processes across spatial and temporal dimensions.

Table 2: Modeling Approaches for Different Spatiotemporal Scales

| Model Type | Spatial Scale Applicability | Temporal Resolution | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Models (Multi-model inference) | Multiple scales (32 GBR catchments) | Event-mean concentrations | Identifies influential catchment characteristics [27] |

| Land Surface Models (ELMv1) | Continental (CONUS) | Daily to seasonal | Quantifies relative importance of heterogeneity sources [25] |

| Hydrological Models (HSPF) | Watershed (636 km² Gap-Cheon) | Continuous time-step | Integrates land and soil contaminant runoff processes [1] |

| Land Use Change Models (FLUS) | Watershed to regional | Decadal predictions | Handles non-linear relationships in land use transitions [1] |

The FLUS (Future Land Use Simulation) model exemplifies advances in handling scale transitions through its integration of top-down System Dynamics and bottom-up Cellular Automata methods [1]. This hybrid approach enables the simulation of land use changes across multiple scales under the influence of both human activities and natural drivers.

Technical Protocols for Scale-Explicit Research

Protocol 1: Multi-Scale Watershed Analysis

Objective: To quantify the effects of land use characteristics on water quality across multiple spatial scales.

Experimental Workflow:

- Watershed Delineation: Divide the target watershed into nested sub-basins using digital elevation models (DEM) and automated delineation tools (e.g., BASINS) [1].

- Land Use Classification: Categorize land use into minimum seven classes (urban, agricultural, forest, grassland, wetland, barren, water) using satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat 8) [1].

- Buffer Zone Creation: Establish riparian buffers of varying widths (50m, 100m, 200m) along all river networks within the watershed.

- Water Quality Sampling: Collect samples at strategic locations representing different spatial scales (basin outlet, sub-basin outlets, etc.) during both dry and wet seasons [24].

- Statistical Analysis: Employ redundancy analysis (RDA) and multiple linear regression to identify optimal scales of land use influence on water quality parameters [24].

Multi-Scale Watershed Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Land-Atmosphere Interaction Assessment

Objective: To quantify the relative importance of different heterogeneity sources on surface water and energy fluxes.

Experimental Workflow:

- Heterogeneity Source Identification: Categorize four primary heterogeneity sources: atmospheric forcing (ATM), soil properties (SOIL), land use/land cover (LULC), and topography (TOPO) [25].

- Experimental Design: Create 16 model experiments with different combinations of heterogeneous and homogeneous datasets for each source [25].

- Model Simulation: Execute land surface model (e.g., ELMv1) across the study domain (e.g., CONUS) with each heterogeneity combination.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate Sobol' total and first-order sensitivity indices to quantify the relative importance of each heterogeneity source [25].

- Component Analysis: Conduct additional experiments to identify critical components within each heterogeneity source (e.g., precipitation, temperature for ATM).

Applications and Research Implications

Water Resource Management in Changing Environments

Understanding spatiotemporal dynamics enables more effective water resource management under changing environmental conditions. In the Yellow River Basin, research has revealed intricate land-atmosphere couplings where decreased soil moisture in arid areas drives increased water availability (precipitation minus evapotranspiration), particularly during summer months [28]. This feedback loop, characterized by a sensitivity coefficient of -0.27 in summer arid areas, has significant implications for water resource planning and climate adaptation strategies [28].

The integration of multi-scale assessments facilitates optimized land use planning for water quality protection. For instance, the identification of urban green spaces, forests, and wetlands as integral components for sustainable watershed management highlights the importance of nature-based solutions in mitigating the impacts of land use changes on water resources [1].

Predictive Modeling and Forecasting

Scale-explicit approaches enhance the accuracy of predictive models for environmental forecasting. In agricultural systems, accounting for the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of environmental conditions significantly improves wheat yield forecasting using remote sensing data and machine learning [29]. Random Forest models consistently outperformed other approaches when incorporating both spectral indices and weather data, with prediction accuracy showing strong monthly fluctuations dependent on environmental conditions [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Studying Land-Water Interactions

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN (HSPF) | Simulates watershed hydrology and water quality under land use and climate changes | Semi-distributed, physically-based continuous time-step model; includes PERLND, IMPLND, RCHRES modules | [1] [30] |

| Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) Model | Predicts land use changes under human activities and natural influences | Integrates System Dynamics and Cellular Automata; uses Artificial Neural Network for probability-of-occurrence surfaces | [1] |

| E3SM Land Model (ELMv1) | Quantifies relative importance of heterogeneity sources on water/energy partitioning | Nested subgrid hierarchy; accounts for atmospheric forcing, soil properties, LULC, and topography | [25] |

| Multi-Model Inference Approach | Identifies influential catchment characteristics affecting spatial water quality variability | Combines multiple plausible models; outperforms single "best model" approach | [27] |

| Sobol' Sensitivity Analysis | Quantifies relative importance of different heterogeneity sources | Variance-based sensitivity analysis; computes total and first-order sensitivity indices | [25] |

Heterogeneity Sources Impact on Fluxes

Spatiotemporal dynamics fundamentally shape the relationships between land use and hydrological cycles, with scale considerations permeating every aspect of water quality research. The frameworks and methodologies presented in this technical guide provide researchers with robust approaches for addressing scale-related challenges in land-water interaction studies. By adopting multi-scale experimental designs, implementing advanced modeling techniques, and applying appropriate analytical frameworks, scientists can generate more accurate representations of complex environmental systems. This scale-explicit understanding is indispensable for developing effective watershed management strategies, predicting system responses to global change, and advancing toward sustainable water resource management in the Anthropocene.

The interaction between land use and the hydrological cycle is a critical determinant of water quality, a relationship that has garnered significant scientific attention over the past two decades. From 2005 to 2025, research in this domain has evolved from documenting isolated impacts to developing integrated, predictive frameworks that account for the complex interplay of anthropogenic activities and natural processes. This in-depth technical guide synthesizes the bibliometric trends and methodological advancements that have characterized this period, offering researchers a comprehensive overview of the field's trajectory.

The central thesis framing this evolution posits that land use changes, particularly urbanization, agricultural expansion, and deforestation, function as primary drivers altering hydrological processes, which subsequently manifest in measurable impacts on water quality parameters. Understanding this chain of causality has required increasingly sophisticated modeling approaches and analytical frameworks capable of bridging disciplinary divides between hydrology, geography, environmental science, and spatial planning.

Publication Trends and Analytical Focus

A systematic review of 78 peer-reviewed studies published between 2005 and 2025, conducted using PRISMA guidelines and bibliometric mapping, reveals distinct trends in research focus and methodology [31]. The field has experienced substantial growth, particularly in the latter half of this period, driven by increasing recognition of water security challenges and the availability of advanced analytical tools.

Research evolution has progressed from early studies establishing correlative relationships between land use classes and water quality parameters to contemporary research that disentangles complex causal pathways across spatial and temporal scales. This progression reflects the field's maturation toward predictive modeling and scenario-based forecasting essential for sustainable water resource management under changing climatic and demographic conditions.

Table 1: Bibliometric Analysis of Research Focus (2005-2025)

| Time Period | Primary Research Focus | Dominant Methodologies | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2010 | Establishing baseline correlations | Statistical analysis; Simple modeling | Urbanization linked to increased runoff; Agriculture affects nutrient loads |

| 2011-2015 | Scale-dependent effects | Multi-scale buffer analysis; GIS integration | Riparian zones critical; Spatial extent influences relationship strength |

| 2016-2020 | Temporal dynamics and seasonal variations | Seasonal sampling; Time-series analysis | Wet season typically shows stronger land-use/water-quality relationships |

| 2021-2025 | Integrated modeling and future scenarios | Machine learning; Combined models (e.g., CA-Markov with HSPF) | Predictive capability improves with integrated approaches [31] [1] [32] |

Key Research Themes and Conceptual Evolution

The conceptual framework governing research on land use-hydrology-water quality interactions has evolved significantly throughout the review period. Early studies typically employed linear cause-effect models, while contemporary research embraces complex systems thinking that accounts for feedback loops, non-stationarity, and cross-scale interactions.

Three primary research themes have dominated the literature:

- Pattern-Process Relationships: Investigating how spatial configurations of land use classes affect hydrological processes and water quality outcomes.

- Scale Dependencies: Examining how land-use/water-quality relationships vary across spatial (reach, catchment, basin) and temporal (seasonal, decadal) scales.

- Predictive Modeling: Developing integrated models to forecast water quality impacts under future land use and climate change scenarios.

This conceptual evolution is visualized in the following research framework:

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols and Analytical Techniques

Land Use Change Detection and Projection

A critical methodological advancement has been the refinement of protocols for detecting and projecting land use changes. The Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model has emerged as a particularly effective tool, combining top-down System Dynamics (SD) and bottom-up Cellular Automata (CA) approaches to simulate future land use patterns under various scenarios [1].

The standard experimental protocol for land use change analysis involves:

- Data Collection: Acquisition of multi-temporal land use data (typically at 5-10 year intervals) from satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel) with ground-truthing.

- Driver Identification: Selection of socioeconomic and environmental variables (population density, distance to roads, elevation, slope) that influence land use transitions.

- Model Training: Using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to establish relationships between historical land use and driving factors, creating probability-of-occurrence surfaces for different land use types.

- Validation: Comparing simulated land use maps with actual historical data to validate model accuracy using metrics like kappa coefficient and figure of merit.

- Scenario Projection: Running the model to project future land use patterns under different development scenarios (e.g., business-as-usual, environmental protection).

Complementary approaches include the Cellular Automata-Markov (CA-Markov) model, which combines Markov chain analysis with spatial contiguity filters to project land use changes, particularly effective in rapidly urbanizing regions [32].

Hydrological and Water Quality Modeling

The Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN (HSPF) has been widely applied to simulate hydrologic and water quality processes in watersheds of various sizes and complexity levels [1]. As a semi-distributed, physically-based continuous time-step model, HSPF facilitates integrated simulation of land and soil contaminant runoff processes with in-stream hydraulic and sediment-chemical interactions.

The standard calibration protocol for hydrological models involves:

- Watershed Discretization: Dividing the watershed into pervious land segments (PERLND), impervious land segments (IMPLND), and reach/reservoirs (RCHRES) based on topography, soil characteristics, and land use.

- Meteorological Input: Incorporating sub-daily weather data (precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration, solar radiation) from monitoring stations, often using Thiessen polygon networks to assign spatial weights.

- Parameter Estimation: Initializing model parameters based on literature values and watershed characteristics.

- Iterative Calibration: Adjusting parameters within physically plausible ranges to minimize differences between observed and simulated streamflow and water quality parameters.

- Validation: Testing the calibrated model against an independent dataset not used during calibration.

Model performance is typically evaluated using statistical metrics including:

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): Measures the proportion of variance explained by the model.

- Percent Bias (PBIAS): Indicates the average tendency of simulated values to be larger or smaller than observed values.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Quantifies the average magnitude of errors without considering direction.

Table 2: Key Hydrological and Water Quality Models in Research (2005-2025)

| Model Name | Spatial Representation | Process Capabilities | Application Context | Sensitivity to LULC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPF | Semi-distributed | Hydrologic processes, water quality, contaminant fate | Watersheds of various sizes [1] | High |

| SWAT | Semi-distributed | Hydrologic processes, agricultural management | Large river basins | High |

| CA-Markov | Grid-based | Land use change projection | Scenario development [32] | N/A |

| FLUS | Grid-based | Land use change simulation under scenarios | Future projections [1] | N/A |

Statistical Analysis of Land Use-Water Quality Relationships

Redundancy Analysis (RDA) has emerged as a powerful statistical technique for quantifying the relationship between land use patterns and water quality parameters [33] [34]. This method excels at independently maintaining the contribution of each variable to the variation of dependent variables without integrating them into complex virtual variables.

The standard analytical protocol includes:

- Buffer Delineation: Creating multiple buffer zones (e.g., 50m, 200m, 500m, 1000m, 1500m) around water quality monitoring points or along river networks.

- Land Use Quantification: Calculating the proportional area of each land use class within each buffer zone using GIS.

- Seasonal Stratification: Grouping water quality data by hydrological seasons (dry, average, wet) based on precipitation patterns.

- RDA Implementation: Performing redundancy analysis to determine the variance in water quality parameters explained by land use composition.

- Interpretation: Assessing the angle between land use and water quality arrows in the RDA ranking diagram (angles <90° indicate positive correlation, >90° indicate negative correlation).

This methodology has revealed critical insights about scale dependence in land-use/water-quality relationships, with different buffers often showing varying explanatory power for different water quality parameters [33].

Key Research Findings: Synthesis of Two Decades of Evidence

Consistent Patterns Across Systems and Scales

Research over the past two decades has established several consistent patterns regarding the impacts of land use on hydrological processes and water quality:

- Urbanization intensifies flood risk: A synthesis of 78 studies confirms that urban expansion, deforestation, and vegetation loss consistently intensify surface runoff, peak flow, and flood frequency [31]. The conversion of pervious surfaces to impervious areas reduces infiltration capacity and accelerates runoff generation.

- Seasonal dynamics modulate impacts: Multiple studies have demonstrated that land use changes exert stronger influences on water quality during wet seasons compared to dry seasons, driven by increased runoff that transports pollutants from land to water bodies [33] [34]. For instance, in the Chi and Mun River Basins in Thailand, pH, BOD, Total Coliform Bacteria, Total Phosphorus, Nitrate Nitrogen, and Suspended Solids all increased during the wet season [34].

- Spatial scale affects relationships: The explanatory power of land use on water quality varies with spatial scale. In the Pudong New Area of Shanghai, land use explained approximately 30% of water quality variation, with the strongest explanatory power in the average season [33]. Different land uses showed distinctive scale effects, with urban areas most influential at smaller scales (<500m) while agricultural impacts increased at larger buffers (>500m).

Water Quality Parameters with Strongest Land Use Relationships

Certain water quality parameters have consistently demonstrated stronger relationships with land use patterns:

- Nutrients: Total Nitrogen (TN) and Total Phosphorus (TP) consistently show strong positive correlations with agricultural and urban land uses [1] [32]. In rapidly urbanizing areas, TN exhibited particularly strong associations with construction land (R²=0.691 in prediction models) [32].

- Organic Matter Indicators: Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) frequently increase with urban and agricultural expansion, reflecting elevated organic loading from human activities [34].

- Sediment-Related Parameters: Suspended Solids consistently increase with agricultural expansion and deforestation due to enhanced erosion and transport processes [34].

Table 3: Key Water Quality Parameters and Their Land Use Drivers

| Water Quality Parameter | Most Influential Land Use Types | Direction of Relationship | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | Agricultural land, Urban areas | Positive [32] [34] | Fertilizer application, wastewater discharge |

| Total Phosphorus (TP) | Agricultural land, Urban areas | Positive [32] [34] | Fertilizer application, detergents, soil erosion |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | Forest, Wetlands | Positive [1] | Organic matter loading, temperature |

| Suspended Solids | Agricultural land, Construction sites | Positive [34] | Soil erosion, runoff intensity |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Urban areas, Agricultural land | Positive [34] | Organic waste loading |

Protective Land Uses and Mitigation Strategies

Research has consistently identified natural and semi-natural land covers as protective factors for water quality:

- Forests and vegetation play a crucial role in maintaining water balance through interception, evapotranspiration, and enhanced infiltration [1]. Studies in multiple river basins have confirmed the water purification capabilities of forested areas [34].

- Wetlands function as natural filters, providing flood mitigation and water quality improvement through sediment retention, nutrient transformation, and pollutant removal [1].

- Urban green spaces regulate runoff and enhance water absorption, emerging as key mitigators of urbanization impacts on hydrological systems [1].

Emerging Tools and Technologies

The research landscape has been transformed by technological advancements that enable more precise and comprehensive analyses:

- Remote Sensing and GIS: Satellite imagery and geographic information systems have revolutionized land use classification and change detection, with platforms like Google Earth Engine (GEE) enhancing LULC detection accuracy and flood prediction capability [31].

- Machine Learning Integration: Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) within models like FLUS, and other machine learning approaches have improved handling of non-linear relationships in land use change projections [1].

- Multi-Model Frameworks: Combining models (e.g., CA-Markov with multiple linear regression) has enhanced predictive capability for water quality under future land use scenarios [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrological Models | HSPF, SWAT | Simulate watershed hydrology and water quality | Quantifying LULC impacts on water quantity/quality [1] |

| Land Use Projection Models | FLUS, CA-Markov | Simulate future land use patterns | Scenario development for impact assessment [1] [32] |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | RDA, Multiple Linear Regression | Quantify land-use/water-quality relationships | Establishing predictive relationships [33] [34] |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Google Earth Engine, Landsat | Land use classification and change detection | Historical trend analysis [31] |

| Spectral Indices | NDVI, NDBI, NDWI | Quantify vegetation, built-up areas, water content | Land use characterization [1] |

| Geographic Information Systems | ArcGIS, QGIS | Spatial analysis and buffer creation | Multi-scale analysis [33] |

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements, critical knowledge gaps remain in understanding the mechanisms of land use changes, particularly in de-urbanizing areas, and the long-term effects on watershed hydrology and water quality [1]. Future research priorities include:

- Improved Integration of Socio-Economic Variables: Most current models have limited incorporation of socio-economic drivers of land use change [31].

- Advanced Temporal Dynamics: Better understanding of lag effects and legacy impacts of land use changes on water quality.

- Multi-Scale Modeling Frameworks: Developing approaches that seamlessly integrate processes across spatial and temporal scales [26].

- Enhanced Climate Change Integration: More sophisticated treatment of how climate change interacts with land use to affect hydrological cycles and water quality.

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the integrated approach needed for future research:

This synthesis of two decades of research evolution provides a comprehensive technical foundation for researchers continuing to investigate the critical interactions between land use, hydrology, and water quality. The field has progressed from descriptive studies to predictive modeling capabilities, with future advances likely coming from even greater integration of disciplinary perspectives and methodological approaches.

Advanced Tools and Techniques: Hydrological Models, Remote Sensing, and Statistical Approaches for Water Quality Assessment

The interaction between land use and the hydrological cycle is a critical determinant of water quality, influencing the transport of nutrients, sediments, and pollutants from the landscape to aquatic systems. Understanding these complex interactions requires sophisticated tools capable of simulating integrated watershed processes. Hydrological models serve as virtual laboratories, allowing researchers and water resource professionals to test hypotheses, evaluate scenarios, and predict the impacts of land management decisions on water resources. Within the context of a broader thesis on land use and hydrological interactions, this technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of four prominent hydrological models: SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool), HSPF (Hydrological Simulation Program-FORTRAN), HEC-HMS (Hydrologic Engineering Center-Hydrologic Modeling System), and MIKE SHE. These models represent different approaches to simulating the water cycle, each with distinct strengths, theoretical foundations, and applicability to water quality research. By examining their core architectures, methodological approaches, and practical applications, this review aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to select appropriate modeling tools for investigating the complex relationships between terrestrial systems and hydrological responses.