Langmuir vs. Freundlich Isotherm Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Adsorption System Analysis

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models, two fundamental tools for characterizing surface interactions.

Langmuir vs. Freundlich Isotherm Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Adsorption System Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models, two fundamental tools for characterizing surface interactions. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the theoretical foundations, key assumptions, and mathematical formulations of each model. The scope extends to practical methodologies for data fitting and parameter calculation, guidance for model selection and troubleshooting common pitfalls, and finally, frameworks for experimental validation and comparative analysis to inform the development of adsorption-based applications in pharmaceuticals and environmental remediation.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption Isotherms

Adsorption isotherms are fundamental mathematical models that describe the distribution of adsorbate molecules between a liquid or gas phase and a solid surface at equilibrium at a constant temperature. They are indispensable tools across scientific and industrial domains, from environmental remediation and gas storage to pharmaceutical development. These models quantitatively define the core relationship between the equilibrium concentration of a substance in solution (or partial pressure in gas phase) and the surface loading—the amount adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate isotherm model is critical for accurately characterizing material properties, predicting adsorption capacity, and optimizing processes. This guide provides an objective comparison of the two most prevalent models—Langmuir and Freundlich—by examining their theoretical foundations, practical applications in recent research, and performance against experimental data.

Theoretical Foundations of Isotherm Models

The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms are derived from distinct conceptual frameworks regarding the nature of the adsorbent surface and the adsorption process.

The Langmuir Isotherm Model

Proposed by Irving Langmuir in 1918, this model is based on a set of specific physicochemical assumptions [1]. It posits that adsorption occurs on a perfectly homogeneous surface with identical, energetically equivalent sites. The model describes monolayer adsorption, where each site can accommodate only one adsorbate molecule, and there are no interactions between adsorbed molecules on adjacent sites. The process is characterized by a saturation point where all sites are occupied, representing the maximum adsorption capacity [2] [3]. The model is expressed as:

[ qe = \frac{a b Ce}{1 + b C_e} ]

where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration in solution (mg/L)

- ( a ) is the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g)

- ( b ) is the Langmuir constant related to adsorption energy (L/mg)

The Freundlich Isotherm Model

Developed by Herbert Freundlich in 1906, this is an empirical model designed to describe adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces [4] [3]. It does not assume a monolayer capacity and is instead applicable to multilayer adsorption. A key feature is that the energy of adsorption decreases exponentially as surface coverage increases, reflecting the fact that initial molecules adsorb to the most favorable sites first [3]. The model is expressed as:

[ qe = Kf C_e^{1/n} ]

where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration in solution (mg/L)

- ( K_f ) is the Freundlich constant indicative of adsorption capacity

- ( 1/n ) is the heterogeneity factor indicating adsorption intensity or surface heterogeneity

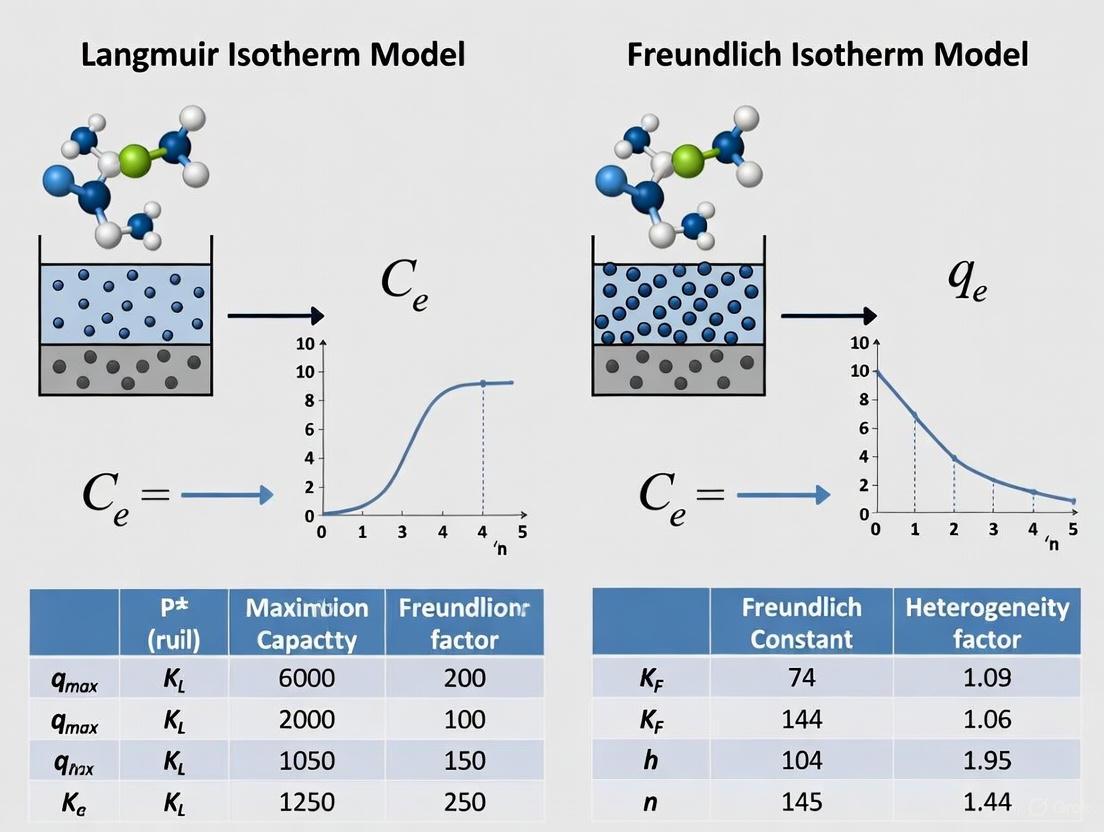

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core assumptions of each model and their mathematical forms:

Experimental Protocols for Isotherm Determination

Determining adsorption isotherms requires a systematic experimental approach to generate reliable equilibrium data. The following workflow outlines a standard batch adsorption procedure, commonly employed in both environmental and pharmaceutical sciences [1] [5].

Detailed Methodology

The standard batch adsorption experiment involves the following key steps [1] [5] [6]:

Adsorbent Preparation and Characterization: The adsorbent (e.g., limestone, mesoporous silica, activated carbon) is often prepared, cleaned, and sieved to a specific particle size range. For synthetic materials like mesoporous silica cocoons (MSNCs), this involves a synthesis process followed by calcination at high temperature (e.g., 550°C for 6 hours) to remove the template agent. Critical characterization includes measuring the specific surface area via the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, pore size distribution via Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) analysis, and morphology via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) or Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [5].

Stock Solution Preparation: A stock solution of the adsorbate (e.g., copper ions, indomethacin, loratadine) is prepared at a high concentration in an appropriate solvent (often water or methanol). Subsequent dilutions are made to create a series of initial concentrations ((C_0)) [6].

Batch Equilibrium Experiments: A fixed mass of adsorbent (e.g., 0.01 g to 10 g/L) is added to a series of flasks containing a fixed volume (e.g., 10 mL to 100 mL) of solutions with varying initial adsorbate concentrations. The flasks are sealed and agitated in a temperature-controlled shaker for a predetermined time (often 24 hours) to ensure equilibrium is reached [1] [6].

Phase Separation and Analysis: After reaching equilibrium, the solid adsorbent is separated from the liquid phase, typically by centrifugation (e.g., at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes) and filtration. The equilibrium concentration ((C_e)) in the supernatant is then quantified using analytical techniques such as UV-Vis spectrophotometry (for drugs like loratadine and indomethacin) or Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (for metal ions like copper) [1] [6].

Data Calculation and Modeling: The amount adsorbed at equilibrium ((qe)) is calculated for each initial concentration using the formula: ( qe = \frac{(C0 - Ce) V}{m} ), where (V) is the solution volume and (m) is the adsorbent mass [1]. The resulting ((Ce), (qe)) data pairs are then fitted to the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm equations using non-linear regression or linearized forms. The coefficient of determination ((R^2)) and error metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are used to evaluate the goodness of fit [1] [7].

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance in Recent Research

The following tables synthesize experimental data from recent studies, highlighting the performance and parameters of the Langmuir and Freundlich models across diverse adsorption systems.

Table 1: Isotherm Model Performance in Environmental and Gas Adsorption Studies

| Adsorbent | Adsorbate | Best-Fit Model | Langmuir Parameters | Freundlich Parameters | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone | Copper (Cu²⁺) | Freundlich | a = 0.022 mg/gb = 1.46 L/mgR² = N/A |

Kf = 0.010 mg/gn = 1.58 L/mgR² = High |

Freundlich provided a better fit, especially at low initial metal concentrations, indicating surface heterogeneity. | [1] |

| Activated Carbon (from Olive Waste) | CO₂ | Multilayer Model* | Qm = 2.28 mol/kg |

Kf = 1.32 mol/kg |

A statistical physics multilayer model outperformed both classic models. n values >1 suggested multi-ion occupancy of sites. |

[7] |

| Tropical Soils (Various Orders) | Phosphate (P) | Freundlich | Underestimated adsorption by ~40% at low P concentrations. | Kf varied with clay content and pH. |

Freundlich best represented P sorption across soil orders; Langmuir failed at low concentrations. | [3] |

*Note: This study introduced a more complex model but reported parameters for comparison.

Table 2: Isotherm Model Performance in Pharmaceutical and Drug Delivery Studies

| Adsorbent | Adsorbate (Drug) | Best-Fit Model | Langmuir Parameters | Freundlich Parameters | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO-MSNCs | Indomethacin (IMC) | Freundlich | Qm = 0.93 μmol/m² (calculated) |

Model showed better fit. | The heterogeneous drug coverage on the carrier surface was best described by the Freundlich isotherm. | [5] |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube | Loratadine | Langmuir | R² = 0.9841/qm = 0.228 |

R² = 0.9681/n = 0.259 |

The Langmuir isotherm had the highest correlation coefficient, suggesting a homogeneous adsorption process. | [6] |

| Mesoporous Silica (SBA-3) | Disulfiram | Hybrid Langmuir* | N/A | N/A | A single Langmuir model was inadequate. A hybrid model with two Langmuir terms for different silanol groups was required for an accurate fit. | [2] |

*Note: This study developed a hybrid model to account for two distinct types of adsorption sites on the silica surface.

Discussion: Interpreting Model Selection and Parameters

The experimental data reveals that the choice between the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm is not arbitrary but provides critical insight into the nature of the adsorption system.

Surface Homogeneity vs. Heterogeneity: When the Langmuir model provides a superior fit (e.g., for Loratadine on carbon nanotubes [6]), it suggests a relatively uniform adsorbent surface with energetically equivalent sites. In contrast, the prevalence of the Freundlich model across most studies—from copper on limestone [1] and indomethacin on MgO-MSNCs [5] to phosphate on diverse soils [3]—highlights that surface heterogeneity is the rule rather than the exception in real-world systems. The

nparameter in the Freundlich model is particularly informative; a value between 1 and 10 indicates a favorable adsorption process [1].Limitations and Advanced Modeling: The failure of the simple Langmuir model for complex systems like disulfiram on silica [2] and CO₂ on activated carbon [7] underscores its limitations. Researchers are increasingly turning to more sophisticated models, such as hybrid Langmuir (to account for discrete sets of different sites) [2] or multilayer models derived from statistical physics (to describe multi-layer formation and pore filling) [7], to achieve a more accurate representation.

Implications for Drug Development: For pharmaceutical scientists, the isotherm model directly impacts carrier design and process optimization. A Freundlich-type adsorption, as seen with indomethacin [5], implies a non-uniform drug distribution on the carrier and the absence of a strict monolayer capacity. This knowledge is crucial for predicting drug loading efficiency and designing controlled release profiles, as the binding energy of drug molecules is not constant but decreases as loading increases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogs key materials and reagents commonly used in adsorption studies, as evidenced by the reviewed literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica (SBA-3, MSNCs) | High-surface-area carrier for drug delivery and catalysis. | Used as a nanocarrier for loading drugs like disulfiram and indomethacin [2] [5]. |

| Activated Carbon (AC) | Versatile, high-surface-area adsorbent for purification and gas capture. | Derived from olive waste for CO₂ adsorption studies [7]. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Structure-directing agent (template) for synthesizing mesoporous silica materials. | Used in the synthesis of SBA-3 silica [2]. |

| Pluronic P123 | Triblock copolymer used as a template for mesoporous material synthesis. | Used in the synthesis of mesoporous silica cocoons (MSNCs) [5]. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Common silica precursor in the sol-gel synthesis of silicate materials. | Used as a silica source for preparing SBA-3 and MSNCs [2] [5]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanostructured adsorbent with high surface area and unique chemical properties. | Used as an adsorbent for the drug Loratadine [6]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Essential analytical instrument for quantifying equilibrium concentrations of adsorbates, especially organic compounds and drugs. | Used to measure Loratadine and Indomethacin concentration before and after adsorption [5] [6]. |

| Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer | Instrument for characterizing key adsorbent properties like surface area (BET), pore volume, and pore size distribution (BJH). | Used to characterize the textural properties of SBA-3, MSNCs, and activated carbons [7] [5]. |

The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models serve as foundational tools for quantifying the relationship between equilibrium concentration and surface loading. The Langmuir model, with its clear concept of monolayer saturation, is powerful for idealized, homogeneous surfaces. However, empirical evidence from environmental science, gas adsorption, and pharmaceutical research consistently demonstrates that the Freundlich model often provides a more realistic fit for complex, heterogeneous adsorbents. The choice of model is not merely statistical; it conveys fundamental information about the surface properties of the adsorbent and the mechanism of the adsorption process. Researchers must therefore base their selection on a rigorous analysis of their own experimental data, considering the possibility that more advanced, multi-parameter models may be necessary to accurately describe systems with multiple adsorption sites or complex interactions.

Adsorption isotherms are fundamental tools in surface science, describing the equilibrium distribution of adsorbate molecules between a solid surface and the surrounding fluid phase at a constant temperature. The modeling of adsorption processes is critical for designing and optimizing systems in diverse fields, including environmental remediation, drug development, catalysis, and gas separation technologies. Among the various models developed, the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms represent two of the most widely applied frameworks for interpreting adsorption data. The Langmuir model, introduced by Irving Langmuir in 1918, is grounded in the theory of monolayer adsorption on homogeneous surfaces. In contrast, the Freundlich model is an empirical equation that describes multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two foundational models, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to aid researchers and scientists in selecting the appropriate model for their specific adsorption systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Model Equations

The Langmuir Isotherm Model

The Langmuir model is based on a precise set of theoretical assumptions. It posits that adsorption occurs at a finite number of identical, well-defined sites on a perfectly homogeneous surface. Each site can adsorb only one molecule, resulting in a monolayer coverage with no interaction between adsorbed molecules. The model further assumes that the adsorption energy is constant across all sites and that the surface is energetically uniform.

The Langmuir isotherm equation is expressed as: [ qe = \frac{{a b Ce}}{{1 + b C_e}} ] where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of solid (mg/g)

- ( a ) is the maximum adsorption capacity corresponding to complete monolayer coverage (mg/g)

- ( b ) is the Langmuir adsorption constant related to the energy of adsorption (L/mg)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium solution concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L) [1].

The Freundlich Isotherm Model

The Freundlich model is an empirical equation used to describe adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and is applicable to multilayer adsorption. It does not assume a maximum adsorption capacity but instead models a continuous increase in adsorption with concentration, though the rate of increase diminishes.

The Freundlich isotherm is defined as: [ qe = Kf C_e^{1/n} ] where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of solid (mg/g)

- ( K_f ) is the Freundlich adsorption constant indicative of the adsorption capacity

- ( 1/n ) is the heterogeneity factor, an empirical constant related to adsorption intensity

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium solution concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L) [1] [8].

A logarithmic linearization is often used: ( \ln qe = \ln Kf + \frac{1}{n} \ln Ce ), which allows for easy determination of the constants ( Kf ) and ( n ) from experimental data [4].

The Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) Isotherm Model

Recognizing the limitations of both models, a hybrid Langmuir-Freundlich isotherm was developed. This three-parameter model can describe adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and converges to the Langmuir model at high adsorbate concentrations and to the Freundlich model at low concentrations.

The model is given by: [ qe = \frac{{q{MLF} (K{LF}Ce)^{M{LF}}}}{{1 + (K{LF}Ce)^{M{LF}}}} ] where:

- ( q_{MLF} ) is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)

- ( K_{LF} ) is the equilibrium constant

- ( M_{LF} ) is a heterogeneity parameter between 0 and 1 [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Isotherm Model Equations and Parameters

| Feature | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model | Langmuir-Freundlich Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Theoretical, based on kinetic principles | Empirical | Semi-empirical, hybrid |

| Surface Assumption | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous |

| Adsorption Type | Monolayer | Multilayer | Monolayer on heterogeneous sites |

| Key Parameters | ( a ) (mg/g), ( b ) (L/mg) | ( K_f ), ( n ) | ( q{MLF} ) (mg/g), ( K{LF} ), ( M_{LF} ) |

| Saturation Capacity | Predicts a definite saturation (( a )) | No saturation limit; infinite surface coverage | Predicts a definite saturation (( q_{MLF} )) |

Experimental Comparison and Performance Data

Case Study: Copper Removal by Limestone Adsorbent

A 2019 study provides a direct experimental comparison of the Langmuir and Freundlich models for the removal of copper (Cu) from synthetic wastewater using limestone as a low-cost adsorbent. Batch adsorption studies were conducted by varying parameters such as initial metal ion concentration, particle size of limestone, and adsorbent dosage.

The experimental data were fitted to both isotherm models, and the goodness of fit was evaluated. The results are summarized below:

Table 2: Model Parameters for Copper Adsorption on Limestone [1]

| Isotherm Model | Parameter | Value | Coefficient of Determination (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | ( a ) (adsorption capacity) | 0.022 mg/g | |

| ( b ) (adsorption constant) | 1.46 L/mg | Not explicitly stated, but described as lower than Freundlich | |

| Freundlich | ( K_f ) (adsorption capacity) | 0.010 mg/g | |

| ( n ) (heterogeneity factor) | 1.58 L/mg | High R², described as a better fit |

The study concluded that for this specific system—particularly at low initial concentrations of copper—the Freundlich isotherm model provided a better description of the adsorption process, as indicated by a higher coefficient of determination (R²). This suggests that the surface of the limestone adsorbent is heterogeneous, and the adsorption of copper likely involves a more complex mechanism than simple monolayer formation [1].

Case Study: Hydroquinone Adsorption on Sandstone

A 2025 study on the adsorption behavior of hydroquinone (a gelation crosslinker) on quartz and sandstone surfaces presented a contrasting finding. The researchers applied the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models to their experimental data.

The Langmuir model demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting the adsorption capacity, with an exceptionally high R² value of 0.999 at 25°C. The model predicted a maximum adsorption capacity (( q_o )) of 47.1 mg/g. This excellent fit indicates that the adsorption of hydroquinone on the relatively homogeneous quartz surface occurs via a monolayer mechanism, validating the core assumptions of the Langmuir model [10].

Case Study: CO₂ Adsorption on Activated Carbon

Research on CO₂ adsorption on activated carbon (AC) derived from olive waste further illustrates the model selection process. While classical models like Langmuir and Freundlich are frequently applied, a 2025 study emphasized that they often lack detailed physicochemical parameters. The study employed advanced statistical physics models to gain deeper insight, finding that a multilayer model with two energy levels best fit the experimental data. This underscores that for complex, highly porous adsorbents like activated carbon, simple models may be insufficient for a thorough mechanistic understanding, even if they provide a good empirical fit [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Batch Adsorption Studies

The following workflow and protocol are synthesized from the methodologies described in the cited research, particularly the studies on copper and hydroquinone adsorption [1] [10].

Diagram 1: Batch Adsorption Experimental Workflow

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent | The solid material that accumulates adsorbate on its surface. | Limestone (3.75 mm, 5.0 mm, 9.5 mm grades) [1]; Quartz sand [10]; Activated Carbon [7]. |

| Adsorbate | The substance to be adsorbed from the solution or gas phase. | Copper (Cu) ions in synthetic wastewater [1]; Hydroquinone (HQ) in aqueous solution [10]; CO₂ gas [7]. |

| Shaking Incubator | Provides constant temperature and agitation for batch experiments to reach equilibrium. | Used to stir quartz-HQ mixture for 24 hours [10]. |

| Centrifuge | Separates the solid adsorbent from the liquid phase after equilibrium is reached. | Used at 6000 rpm to separate quartz particles from HQ solution [10]. |

| Analytical Instrument (e.g., Spectrophotometer) | Quantifies the equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in the solution. | UV-Vis spectrophotometer used to determine residual HQ concentration [10]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Adsorbate Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of aqueous solutions of the adsorbate with varying initial concentrations (e.g., from 100 mg/L to 100,000 mg/L for hydroquinone [10]). Use distilled water and ensure complete dissolution and homogeneity using a magnetic stirrer.

Batch Equilibrium Experiments: For each initial concentration, place a known mass of the adsorbent (e.g., 20 g of quartz [10]) into a vessel containing a known volume (e.g., 100 mL) of the adsorbate solution. Seal the vessels and place them in a shaking incubator. Maintain a constant temperature and agitation speed for a sufficient duration (e.g., 24 hours [10]) to ensure equilibrium is reached. Other parameters like adsorbent particle size and dosage can be varied systematically.

Phase Separation: After the equilibrium period, separate the solid adsorbent from the liquid phase. This is typically achieved by centrifugation (e.g., at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes [10]) followed by filtration of the supernatant to ensure no fine particles remain.

Equilibrium Concentration Analysis: Analyze the clear supernatant to determine the equilibrium concentration (( C_e )) of the adsorbate. For metal ions or organic compounds, techniques like UV-Vis spectrophotometry are commonly used [10]. For gases, specialized equipment like a magnetic suspension balance is employed [11] [7].

Data Calculation: Calculate the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (( qe )) using the following equation [1] [10]: [ qe = \frac{{(C0 - Ce) V_s}}{{m}} ] where:

- ( C_0 ) is the initial concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L)

- ( V_s ) is the volume of the solution (L)

- ( m ) is the mass of the adsorbent (g)

The following decision chart synthesizes the findings from the reviewed studies to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate isotherm model.

Diagram 2: Isotherm Model Selection Guide

The choice between the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models is not a matter of which is universally superior, but rather which is more appropriate for the specific adsorbent-adsorbate system under investigation.

Use the Langmuir Model when the adsorption process is characterized by monolayer coverage on a homogeneous surface. This is often the case for chemical adsorption (chemisorption) on well-defined crystalline materials or specific, uniform active sites. The excellent fit of the Langmuir model for hydroquinone on quartz is a prime example [10]. Its parameters provide a clear physical meaning: the maximum monolayer capacity (( a )) and the affinity constant (( b )).

Use the Freundlich Model to describe adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces where the energy of adsorption is not uniform, often leading to multilayer formation. It is particularly useful for physical adsorption (physisorption) on complex natural materials like soils, limestone, or activated carbon, especially in the low to moderate concentration range [1] [8]. The parameters ( K_f ) and ( n ) offer insights into the relative adsorption capacity and the degree of surface heterogeneity.

Consider Hybrid or Advanced Models like the Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) isotherm for systems exhibiting heterogeneity but also a clear saturation limit [9]. For more complex scenarios, such as the CO₂ adsorption on activated carbon, statistical physics models or models accounting for multiple energy levels can provide a more profound mechanistic understanding beyond the scope of classical models [7].

Ultimately, researchers should fit their experimental data to multiple models and use statistical metrics (like R² and RMSE) alongside a fundamental understanding of their system's physics and chemistry to select the most representative and useful adsorption isotherm.

In the field of adsorption science, researchers and industry professionals rely on mathematical models to describe how molecules interact with solid surfaces. Two of the most fundamental approaches are the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models, which form the theoretical basis for applications ranging from environmental remediation to pharmaceutical development. The Langmuir isotherm represents a theoretical model based on kinetic principles that describes monolayer adsorption onto a homogeneous surface, while the Freundlich isotherm serves as an empirical model for heterogeneous surfaces. Understanding their core assumptions, mathematical formulations, and experimental validity is crucial for selecting the appropriate model for specific research and development applications, particularly in drug development where purification processes depend on precise adsorption characterization.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

The Langmuir Isotherm Model

The Langmuir isotherm was originally developed to describe gas-solid interactions but is now extensively applied to liquid-solid systems in various scientific and industrial fields. The model operates on a fundamental kinetic principle where the rate of adsorption equals the rate of desorption at equilibrium conditions, with no accumulation at the surface [12].

The underlying assumptions of the Langmuir model are [12] [13]:

- Identical Active Sites: The solid surface possesses uniform, homogeneous adsorption sites with identical energy.

- Monolayer Coverage: Each active site can adsorb only one molecule, resulting in a single layer of adsorbed molecules.

- No Molecular Interactions: Adsorbed molecules do not interact with one another.

The nonlinear form of the Langmuir equation is expressed as [12]:

[ qe = \frac{qo KL Ce}{1 + KL Ce} ]

Where:

- ( q_e ) = amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g)

- ( q_o ) = maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g)

- ( K_L ) = Langmuir constant related to adsorption energy (L/mg)

- ( C_e ) = equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in solution (mg/L)

The linearized form is represented as [12]:

[ \frac{Ce}{qe} = \frac{1}{KL qo} + \frac{Ce}{qo} ]

Table 1: Parameters of the Langmuir Isotherm Model

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Adsorption Capacity | ( q_o ) | mg/g | Theoretical maximum monolayer coverage |

| Langmuir Constant | ( K_L ) | L/mg | Affinity between adsorbate and adsorbent |

| Equilibrium Concentration | ( C_e ) | mg/L | Unadsorbed concentration at equilibrium |

| Separation Factor | ( R_L ) | Dimensionless | Indicates favorability of adsorption |

A key diagnostic parameter derived from the Langmuir model is the separation factor (( R_L )), defined as [12]:

[ RL = \frac{1}{1 + KL C_o} ]

Where ( Co ) is the initial concentration. The value of ( RL ) indicates the nature of the adsorption process: irreversible (( RL = 0 )), favorable (( 0 < RL < 1 )), linear (( RL = 1 )), or unfavorable (( RL > 1 )).

The Freundlich Isotherm Model

In contrast to Langmuir's theoretical approach, the Freundlich isotherm is an empirical model derived to describe multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces with sites of varying energies [14]. This model does not assume a theoretical maximum adsorption capacity, making it particularly useful for systems where adsorption capacity continues to increase with concentration.

The Freundlich equation is expressed as [1] [14]:

[ qe = KF C_e^{1/n} ]

Where:

- ( q_e ) = amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g)

- ( K_F ) = Freundlich constant indicating adsorption capacity

- ( 1/n ) = heterogeneity factor indicating adsorption intensity

- ( C_e ) = equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in solution (mg/L)

The linearized form is obtained by taking logarithms:

[ \log qe = \log KF + \frac{1}{n} \log C_e ]

Table 2: Parameters of the Freundlich Isotherm Model

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Capacity | ( K_F ) | mg/g | Relative adsorption capacity |

| Heterogeneity Factor | ( 1/n ) | Dimensionless | Indicator of surface heterogeneity |

| Adsorption Intensity | ( n ) | Dimensionless | Favorability of adsorption |

The value of ( n ) indicates the favorability of adsorption, with values between 1 and 10 representing favorable adsorption conditions. As ( n ) increases, the adsorption intensity becomes more favorable.

Experimental Comparison: Copper Removal by Limestone Adsorbent

Methodology and Experimental Protocol

A comprehensive study comparing the applicability of Langmuir and Freundlich models was conducted using limestone as a low-cost adsorbent for copper removal from aqueous solutions [1]. The experimental protocol included the following key steps:

Materials Preparation:

- Limestone samples were obtained from two geographical sources: western red (3.75 mm diameter) and northern white (5.0 mm and 9.5 mm diameters)

- Chemical characterization showed the limestone contained primarily CaO (52.35%), with significant amounts of SiO₂ (3.15%) and LOI (43.20%)

- Samples were prepared using sieve analysis to ensure consistent particle size distribution

Batch Adsorption Studies:

- Synthetic copper solutions with varying initial concentrations (( C_o )) were prepared

- Experiments investigated parameters including initial metal ion concentration, particle size, adsorbent dosage, and equilibrium concentration

- The effects of these parameters on copper removal efficiency were systematically evaluated

Analytical Procedure:

- Known masses of limestone adsorbent were added to copper solutions

- The mixture was agitated until equilibrium was established

- Post-adsorption copper concentrations were measured to determine removal efficiency using:

[ \text{Sorption Efficiency} = \frac{C0 - Ce}{C_0} \times 100\% ]

[ qe = (C0 - C_e) \times \frac{v}{m} ]

Where ( v ) = volume of solution (L) and ( m ) = mass of adsorbent (g)

Isotherm Modeling:

- Experimental data were fitted to both Langmuir and Freundlich models

- Model parameters were determined through regression analysis

- Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using coefficient of determination (R²)

Comparative Results and Model Performance

The experimental results demonstrated that the Freundlich isotherm model provided a better fit for copper adsorption on limestone compared to the Langmuir model, particularly at lower initial copper concentrations [1].

Table 3: Experimental Parameters for Copper Adsorption on Limestone

| Parameter | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Constant | ( b = 1.46 ) L/mg | ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g |

| Capacity Constant | ( a = 0.022 ) mg/g | ( n = 1.58 ) L/mg |

| Empirical Constant | Not applicable | ( 1/n = 0.633 ) |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Lower than Freundlich | Higher than Langmuir |

The Freundlich model's superior performance, indicated by higher R² values, suggests that limestone surfaces exhibit heterogeneous adsorption sites with varying energies, contrary to the homogeneous site assumption of the Langmuir model. The observed value of ( n = 1.58 ) (( n > 1 )) indicates favorable adsorption conditions for copper on limestone.

The maximum adsorption capacity of limestone for copper removal was determined to be 3.58 mg/g, demonstrating its technical feasibility as a low-cost adsorbent for wastewater treatment applications [1].

Research Applications and Practical Implications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Adsorption Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Adsorption Studies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon | High-surface-area adsorbent for contaminant removal | Removal of arsenic and fluoride from water [15] |

| Limestone | Low-cost adsorbent for heavy metal removal | Copper removal from aqueous solutions [1] |

| Silica Gel | Desiccant for moisture control | Humidity control in medicines and packaging [14] |

| Animal Charcoal | Decolorizing agent | Removal of coloring agents from cane juice [14] |

| Chitosan | Biopolymer adsorbent | Removal of Fe(II) from aqueous media [1] |

| Bentonite Clay | Natural clay adsorbent | Removal of Zn²⁺ from wastewater [1] |

Decision Framework for Model Selection

The choice between Langmuir and Freundlich models depends on the specific characteristics of the adsorption system and the study objectives:

Langmuir Model is preferable when:

- The surface is known to be homogeneous with uniform adsorption sites

- Monolayer coverage is expected

- Determining maximum adsorption capacity is essential

- Studying gas-solid phase interactions [12]

Freundlich Model is preferable when:

- The surface is heterogeneous with sites of different energies

- Multilayer adsorption is suspected

- Empirical correlation is sufficient for practical applications

- Working with liquid-solid systems with complex interactions [1]

For complex systems involving multiple adsorbates, extended models such as the Extended Langmuir-Freundlich (ELF) model have shown excellent fit for binary adsorption systems, as demonstrated in studies of simultaneous arsenic and fluoride removal [15].

The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models represent fundamentally different approaches to characterizing adsorption systems. The Langmuir model provides a theoretical foundation based on specific assumptions of uniform sites, monolayer coverage, and no intermolecular interactions. In contrast, the Freundlich model offers empirical flexibility for heterogeneous surfaces. Experimental evidence from copper removal studies on limestone demonstrates that the Freundlich model often provides better fit for real-world adsorption systems, highlighting the inherent surface heterogeneity of natural adsorbents. Researchers and drug development professionals should consider these fundamental differences when selecting appropriate models for their specific applications, with Langmuir suitable for well-characterized homogeneous surfaces and Freundlich more applicable to complex, heterogeneous systems.

In the field of separation science and environmental engineering, adsorption isotherms are fundamental tools for quantifying how molecules distribute between a solid surface and a surrounding fluid phase. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate adsorption model is critical for predicting compound behavior in systems ranging from water purification to pharmaceutical formulation. Two of the most prevalent models—the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms—offer fundamentally different approaches to characterizing these interactions. The Langmuir model provides a theoretical framework based on homogeneous surface binding, while the Freundlich model offers an empirical approach specifically designed for heterogeneous surfaces with varied adsorption energies. This guide provides an objective comparison of these models' performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform research design and interpretation.

The Freundlich model, introduced by Herbert Freundlich in 1909, has established itself as a powerful empirical tool for modeling adsorption on complex, energetically diverse surfaces commonly encountered in real-world materials such as activated carbons, soils, and bio-sorbents [16]. Unlike theoretically derived models, its empirical nature allows it to flexibly describe adsorption behavior across many heterogeneous systems where multiple simultaneous adsorption processes occur [17]. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts for both Freundlich and Langmuir models enables scientists to make informed decisions in adsorptive process design and interpretation.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

The Freundlich Isotherm Model

The Freundlich isotherm expresses the relationship between the concentration of a solute adsorbed onto a solid surface and its concentration in the surrounding solution at equilibrium. Its mathematical form is:

[ qe = KF \cdot C_e^{1/n} ]

Where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in solution (mg/L)

- ( K_F ) is the Freundlich constant related to adsorption capacity ((mg/g)/(mg/L)(^n))

- ( 1/n ) is the heterogeneity factor indicating adsorption intensity (dimensionless) [16] [18]

The model is particularly valuable for characterizing non-ideal sorption on heterogeneous surfaces and multilayer adsorption [19]. The parameter ( 1/n ) provides quantitative insight into the energy distribution of adsorption sites. When ( 1/n = 1 ), the adsorption is linear and site energies are uniform; as ( 1/n ) decreases below 1, the surface becomes more heterogeneous, with high-energy sites being occupied first followed by progressively lower-energy sites [17]. Typically, ( 1/n ) values range from 0.7 to 1.0 for most systems, though values outside this range occur in specific applications [17].

The Langmuir Isotherm Model

In contrast to the empirical Freundlich approach, the Langmuir model derives from theoretical assumptions about the adsorption process:

[ qe = \frac{qm \cdot KL \cdot Ce}{1 + KL \cdot Ce} ]

Where:

- ( q_m ) is the maximum adsorption capacity corresponding to complete monolayer coverage (mg/g)

- ( K_L ) is the Langmuir constant related to the energy of adsorption (L/mg)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in solution (mg/L) [19] [18]

The Langmuir model assumes a homogeneous surface with identical adsorption sites, monolayer coverage where no further adsorption occurs once a site is occupied, and no interactions between adsorbed molecules [18] [20]. These constraints make it particularly suitable for modeling chemical adsorption (chemisorption) on uniform surfaces where binding occurs through specific chemical interactions [20].

Comparative Analysis: Model Performance and Applications

Direct Comparison of Model Parameters

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Freundlich and Langmuir Isotherm Models

| Feature | Freundlich Model | Langmuir Model |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Empirical | Theoretical |

| Surface Assumption | Heterogeneous | Homogeneous |

| Adsorption Layer | Multilayer possible | Monolayer only |

| Site Energy | Distributed | Uniform |

| Saturation Capacity | No maximum predicted | Distinct maximum (qm) |

| Linearity Form | log qe = log KF + (1/n) log Ce | Ce/qe = 1/(KLqm) + Ce/qm |

| Best Application Range | Moderate concentration range | Low to high concentration |

| Common Applications | Environmental systems, soils, complex sorbents | Gas adsorption, engineered surfaces, specific binding |

Interpretation of Model Parameters

The parameters derived from each model provide distinct insights into the adsorption process:

Freundlich Parameters:

- ( K_F ): Represents the adsorption capacity at a unit equilibrium concentration. Higher values indicate greater overall adsorption potential [20].

- ( 1/n ): Reflects the surface heterogeneity and adsorption intensity. Values between 0.7-1.0 indicate favorable adsorption, while values below 0.7 suggest highly heterogeneous surfaces with strong initial binding [17].

Langmuir Parameters:

- ( q_m ): The theoretical maximum adsorption capacity, representing complete monolayer coverage [19] [18].

- ( K_L ): Related to the affinity of binding sites and energy of adsorption. Higher values indicate stronger adsorbate-adsorbent interactions [19].

Performance in Experimental Systems

Experimental studies directly comparing both models reveal context-dependent performance:

In copper removal using limestone adsorbent, the Freundlich model demonstrated superior correlation with experimental data compared to the Langmuir model, particularly at lower contaminant concentrations [1]. The Freundlich constants reported were ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g and ( n = 1.58 ), with high coefficient of determination (R²) values [1].

For adsorption of orthophosphate onto oyster shell powder, the Freundlich equation provided a better mathematical description of the adsorption equilibrium than the Langmuir equation [19]. Conversely, methylene blue adsorption onto powdered activated carbon (PAC) was better described by the Langmuir model, reflecting the more homogeneous nature of the activated carbon surface for this specific adsorbate [19].

These results highlight how material properties and system conditions dictate model suitability, with Freundlich generally excelling for complex, natural adsorbents and Langmuir performing better with engineered, uniform surfaces.

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Batch Adsorption Methodology

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent | Varies by study (e.g., activated carbon, limestone, oyster shell powder) | Solid surface for adsorbate attachment |

| Adsorbate | Target compound (e.g., heavy metals, organic dyes, pharmaceuticals) | Substance whose adsorption is being quantified |

| Background Electrolyte | NaCl, KCl, or CaCl2 solutions | Maintains constant ionic strength |

| pH Buffer Solutions | Appropriate buffer systems for target pH range | Controls solution acidity/alkalinity |

| Analytical Instrumentation | UV-Vis spectrophotometer, AAS, HPLC | Quantifies adsorbate concentration |

A standardized batch adsorption protocol involves the following steps:

Adsorbent Preparation: Characterize and prepare the adsorbent material with defined particle size. For example, in limestone adsorption studies, particles are typically sieved to 3.75 mm for optimal performance [1].

Adsorbate Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of known concentrations using analytical grade reagents. For heavy metal studies, solutions are often prepared from metal salts like CuSO₄ or Na₂HPO₄ in deionized water [19].

Batch Equilibrium Experiments: Combine fixed masses of adsorbent (e.g., 0.1-10 g/L) with adsorbate solutions of varying initial concentrations in sealed containers. Agitate continuously in a temperature-controlled environment until equilibrium is reached (typically 24 hours) [19] [1].

Sampling and Analysis: After reaching equilibrium, separate the solid and liquid phases by centrifugation or filtration. Analyze the supernatant for equilibrium concentration (Ce) using appropriate analytical methods [1].

Data Calculation: Calculate adsorption capacity (qe) using the mass balance equation:

[ qe = \frac{(C0 - C_e) \cdot V}{m} ]

Where C₀ is the initial concentration (mg/L), V is the solution volume (L), and m is the adsorbent mass (g) [1].

Model Fitting and Validation

To fit experimental data to the Freundlich model, linearize the equation by taking logarithms:

[ \log qe = \log KF + \frac{1}{n} \log C_e ]

Plot log qe versus log Ce to obtain a straight line where the intercept gives log KF and the slope provides 1/n [16] [18]. The coefficient of determination (R²) indicates the goodness of fit, with values closer to 1.0 representing better correlation [17].

For the Langmuir model, linearize using the form:

[ \frac{Ce}{qe} = \frac{1}{KL \cdot qm} + \frac{Ce}{qm} ]

Plot Ce/qe versus Ce to determine 1/(KLqm) from the intercept and 1/qm from the slope [19] [18].

Diagram 1: Adsorption Isotherm Model Selection Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the decision process for selecting and validating adsorption models based on experimental data.

Limitations and Advanced Modeling Approaches

Model Constraints and Considerations

Both models have specific limitations that researchers must consider:

Freundlich Model Limitations:

- Purely empirical nature provides limited mechanistic insight [18]

- Does not predict an adsorption maximum, implying infinite capacity with increasing concentration [18] [20]

- Applicability is typically restricted to moderate concentration ranges [20]

- Parameters are system-specific and cannot be extrapolated beyond tested conditions [21]

Langmuir Model Limitations:

- Assumptions of homogeneity and monolayer coverage rarely hold for complex real-world adsorbents [18]

- Cannot describe multilayer adsorption (physisorption) commonly observed in environmental systems [20]

- Fails to account for interactions between adsorbed molecules [18]

- Often requires data resolution into multiple linear regions for heterogeneous surfaces, complicating interpretation [18]

Integrated and Advanced Modeling Approaches

To address the limitations of individual models, researchers have developed several advanced approaches:

The Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) isotherm combines features of both models:

[ qe = \frac{q{MLF} \cdot (K{LF} \cdot Ce)^{M{LF}}}{1 + (K{LF} \cdot Ce)^{M{LF}}} ]

This hybrid model behaves like the Freundlich isotherm at low concentrations and approaches Langmuir behavior at high concentrations, thus predicting monolayer capacity while accommodating surface heterogeneity [9]. The parameter MLF (between 0 and 1) quantifies system heterogeneity [9].

Statistical analysis packages such as Statistica, Matlab, and specialized applications like IZO provide sophisticated tools for nonlinear regression analysis of adsorption data, enabling more accurate parameter estimation than traditional linearization methods [20]. These tools help researchers select the most appropriate model based on statistical goodness-of-fit metrics rather than visual assessment alone.

The Freundlich isotherm remains an indispensable tool for characterizing adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces commonly encountered in environmental systems, soils, and complex biological materials. Its empirical parameters effectively describe non-ideal behavior across moderate concentration ranges, though researchers should acknowledge its limitation in predicting maximum adsorption capacity. The Langmuir model, while theoretically grounded, performs best with homogeneous surfaces exhibiting specific, monolayer binding behavior.

For drug development professionals and researchers, model selection should be guided by the specific adsorbent-adsorbate system and the intended application of the resulting parameters. In many practical scenarios, a sequential approach—testing both models and selecting based on statistical fit—provides the most scientifically defensible pathway. The emergence of hybrid models and sophisticated fitting algorithms continues to enhance our ability to extract meaningful parameters from adsorption data, ultimately supporting advances in pharmaceutical development, environmental remediation, and separation process optimization.

In both industrial applications and environmental science, the process of adsorption—where atoms, ions, or molecules (adsorbates) accumulate on a solid surface (adsorbent)—is a critical separation and purification technique. The accurate modeling of this process is essential for designing efficient systems, from water treatment plants to drug delivery platforms. Adsorption isotherm models are the mathematical frameworks that describe the distribution of adsorbate molecules between the liquid and solid phases at equilibrium. Within this field, the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms represent two foundational models, each with distinct theoretical bases and applications. The Langmuir model hypothesizes a homogeneous surface with identical adsorption sites and monolayer coverage, often associated with chemisorption [22] [9]. In contrast, the Freundlich isotherm is an empirical model that describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and does not assume a maximum adsorption capacity, making it highly applicable to multi-layer adsorption and physical sorption processes commonly encountered with porous materials [16] [23]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these models, with a focused examination of the significance of the Freundlich constants.

Theoretical Framework: Langmuir vs. Freundlich Models

The Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm

Developed by Irving Langmuir in 1916, this model is theoretically derived from kinetics, thermodynamics, and statistical mechanics, assuming an adsorbate behaves as an ideal gas at isothermal conditions [24]. Its core postulates are [24] [22]:

- Monolayer Coverage: Adsorption is limited to a single molecular layer on the adsorbent surface.

- Homogeneous Surface: All adsorption sites are energetically equivalent.

- No Intermolecular Interactions: Adsorbed molecules do not interact with one another.

The model is mathematically expressed as: [ qe = \frac{qm KL Ce}{1 + KL Ce} ] where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g)

- ( q_m ) is the maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g)

- ( K_L ) is the Langmuir constant related to the energy of adsorption (L/mg)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in solution (mg/L) [1] [22]

A dimensionless separation factor, ( RL ), can be derived to predict the favorability of adsorption: irreversible (( RL = 0 )), favorable (( 0 < RL < 1 )), linear (( RL = 1 )), or unfavorable (( R_L > 1 )) [9].

The Freundlich Adsorption Isotherm

Proposed by Herbert Freundlich in 1909, this model is empirical, derived from experimental data rather than theoretical assumptions [16]. It is designed to handle:

- Heterogeneous Surfaces: The surface of the adsorbent possesses sites with different adsorption energies.

- Multi-layer Adsorption: The model can describe adsorption beyond a single layer.

The Freundlich equation is expressed as: [ qe = KF C_e^{\,1/n} ] where:

- ( q_e ) is the amount adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g)

- ( C_e ) is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L)

- ( K_F ) and ( n ) are the Freundlich constants specific to the adsorbate-adsorbent pair at a given temperature [16] [1] [23]

The model can also be linearized for easier parameter determination: [ \log qe = \log KF + \frac{1}{n} \log C_e ]

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of the Langmuir and Freundlich Isotherm Models.

| Feature | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Theoretical derivation | Empirical observation |

| Surface Nature | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous |

| Adsorption Layer | Monolayer | Multi-layer |

| Adsorption Capacity | Fixed maximum (( q_m )) | No fixed maximum; increases with ( C_e ) |

| Constants | ( qm ) (capacity), ( KL ) (affinity) | ( K_F ) (capacity), ( n ) (intensity/heterogeneity) |

| Best Application | Chemisorption on uniform surfaces | Physisorption on porous, heterogeneous surfaces |

Deep Dive into the Freundlich Constants Kf and 1/n

The utility of the Freundlich isotherm lies in the physical meaning of its two constants, which provide qualitative and quantitative insights into the adsorption process.

Kf: The Adsorption Capacity Constant

- Physical Significance: ( KF ) is an empirical constant indicative of the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent [23]. A higher value of ( KF ) generally signifies a greater adsorption capacity for the specific adsorbate under the experimental conditions. It can be visualized as the value of ( qe ) when ( Ce ) equals 1, as derived from the linearized equation.

- Dimensionality: The units of ( K_F ) are (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n, which are dependent on the value of ( n ), making it crucial to report both constants together.

1/n: The Surface Heterogeneity and Intensity Constant

- Physical Significance: The parameter ( 1/n ) is a dimensionless measure of the deviation from linearity and the heterogeneity of the adsorption surface [16] [23].

- If ( n = 1 ) (( 1/n = 1 )), the adsorption is linear, and the partition between the two phases is independent of concentration. This implies a relatively homogeneous surface.

- If ( n > 1 ) (( 1/n < 1 )), it indicates that the adsorption energy decreases with increasing surface coverage. This is considered a favorable adsorption process and is characteristic of heterogeneous surfaces where the highest-energy sites are occupied first [23].

- If ( n < 1 ) (( 1/n > 1 )), it suggests an unfavorable adsorption process, which is less common [23].

- Relationship to Heterogeneity: A value of ( 1/n ) significantly less than 1 (i.e., ( n > 1 )) is a strong indicator of surface heterogeneity. As adsorption proceeds, the adsorbate molecules fill the most favorable, high-energy sites first, and subsequently occupy less favorable sites, leading to a nonlinear isotherm curve [16].

Table 2: Interpretation of the Freundlich Constant ( n ) and its Derivative ( 1/n ).

| Value of ( n ) | Value of ( 1/n ) | Adsorption Nature | Surface Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( n < 1 ) | ( 1/n > 1 ) | Unfavorable | -- |

| ( n = 1 ) | ( 1/n = 1 ) | Linear | Relatively homogeneous |

| ( n > 1 ) | ( 1/n < 1 ) | Favorable | Heterogeneous |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the Freundlich constants and the properties of an adsorbent material.

Diagram 1: Logic of Freundlich constants.

Experimental Data and Model Performance Comparison

The practical performance of the Langmuir and Freundlich models varies significantly depending on the adsorbent-adsorbate system. The following table summarizes findings from recent research, highlighting the role of the Freundlich constants.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Langmuir and Freundlich Models in Selected Studies.

| Adsorbent | Adsorbate | Best-Fit Model | Freundlich Constants | Langmuir Constants | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limestone [1] | Copper (Cu) | Freundlich | ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g( n = 1.58 ) | ( a = 0.022 ) mg/g( b = 1.46 ) L/mg | Freundlich model showed a higher coefficient of determination (R²) than Langmuir, especially at low concentrations. |

| Iron Oxide Impregnated Activated Carbon [25] | CO₂ | Freundlich | Not Specified | Not Specified | The Freundlich isotherm provided the best fit for the experimental data, confirming the heterogeneous nature of the modified adsorbent. |

| Various Soils [22] | Arsenic (As) | Langmuir (in most cases) | -- | ( q_m ) varied from 114.8 to 42,400 mg/kg across soil types | The Langmuir model, including a two-surface variant, often correlated better with soil properties like iron and clay content. |

Case Study: Copper Removal by Limestone

A 2019 study provides a clear example for comparing the two models. The research aimed to remove copper ions from synthetic wastewater using limestone as a low-cost adsorbent [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Materials: Limestone (3.75 mm, 5.0 mm, 9.5 mm particle sizes) was obtained and characterized. A synthetic copper solution was prepared.

- Batch Adsorption: Experiments were conducted by agitating a known mass of limestone adsorbent with a known volume and concentration of copper solution.

- Analysis: The effects of initial metal concentration, particle size, and adsorbent dosage were studied. After reaching equilibrium, the final concentration (( Ce )) was measured, and the amount adsorbed (( qe )) was calculated using ( qe = (C0 - C_e) \times V/m ) [1].

- Model Fitting: The (( Ce ), ( qe )) data pairs were fitted to the linear forms of both the Langmuir and Freundlich equations to determine the constants and the coefficient of determination (R²).

Result Interpretation: The Freundlich model described the process better, with ( n = 1.58 ) indicating a favorable adsorption process (( n > 1 )) on a heterogeneous surface [1]. The low value of ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g reflects the moderate capacity of raw limestone for copper under these specific conditions. The success of the Freundlich model suggests the limestone surface has sites with varying adsorption energies, which is expected for a natural, non-uniform material.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions relevant to conducting adsorption experiments and analyzing data using these isotherm models.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials for Adsorption Studies.

| Item | Function in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Adsorbent | The material providing surface area for adsorption; its properties dictate the mechanism. | Limestone [1], Activated Carbon [25], Iron Oxide [25], Peat Moss [1], Soils [22]. |

| Adsorbate Solution | The dissolved substance to be removed; its initial concentration is a key variable. | Copper ions [1], CO₂ gas [25], Arsenic species [22]. |

| Shaker Incubator | Provides controlled agitation and temperature to maintain isothermal conditions during batch studies. | Used in batch adsorption studies to reach equilibrium [1]. |

| Analytical Instrument (e.g., AAS, ICP) | Quantifies the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in solution after adsorption. | Essential for determining ( Ce ) and subsequently ( qe ) [1]. |

| Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) Model | A three-parameter hybrid isotherm used for heterogeneous surfaces that approaches Langmuir behavior at high concentrations. | Resolves limitations of pure Freundlich model; useful for systems showing saturation [9]. |

The workflow for a typical batch adsorption study, from preparation to data analysis, is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Batch adsorption experiment workflow.

The choice between the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the appropriate tool for the specific adsorbent-adsorbate system. The Langmuir model is powerful when the adsorption process is characterized by monolayer coverage on a homogeneous surface, often leading to a well-defined maximum capacity (( q_m )). In contrast, the Freundlich model excels in describing adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces, such as those of natural materials and porous carbons, where the energy of adsorption is not uniform.

For researchers, the Freundlich constants ( KF ) and ( 1/n ) provide critical, interpretable parameters. ( KF ) offers a measure of adsorption capacity, while ( 1/n ) serves as a robust indicator of surface heterogeneity and adsorption favorability. The experimental data clearly shows that for many systems, especially those involving complex, natural, or modified adsorbents, the Freundlich model provides a more accurate description of equilibrium data. Future research will continue to leverage these models, and their hybrid extensions like the Langmuir-Freundlich (Sips) isotherm, to design more efficient adsorbents for challenges ranging from environmental remediation to pharmaceutical development.

Adsorption isotherm models are fundamental tools in environmental science, chemical engineering, and pharmaceutical development for describing how solutes interact with solid surfaces. The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms are two of the most widely used models for characterizing equilibrium adsorption data. While often applied to experimental results, these models are built on distinct theoretical foundations and core hypotheses about the nature of the adsorption process. This guide provides an objective comparison of these foundational principles, supported by experimental data and protocols, to aid researchers in selecting and applying the appropriate model for their specific adsorption system.

Core Hypotheses and Theoretical Foundations

The following table summarizes the fundamental hypotheses and characteristics of the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption models.

Table 1: Core hypotheses and characteristics of the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models.

| Feature | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Theoretical, derived from kinetic principles [9] | Empirical, based on experimental data fitting [3] |

| Surface Hypothesis | Homogeneous surface with identical adsorption sites [19] [3] | Heterogeneous surface with sites of different energies [19] [3] |

| Adsorption Mechanism | Monolayer adsorption: Each adsorbate molecule occupies one site; no interaction between adsorbed molecules [19] [3] | Multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces; allows for interactions [19] [3] |

| Energy Distribution | Constant adsorption energy, independent of surface coverage [3] | Exponentially decreasing heat of adsorption with increasing surface coverage [3] |

| Saturation Capacity | Predicts a clear maximum saturation capacity ((q_{max})) [19] [1] | No defined saturation limit; adsorption capacity can increase gradually [3] |

| Mathematical Form | ( qe = \frac{q{max} KL Ce}{1 + KL Ce} ) [19] | ( qe = KF C_e^{1/n} ) [1] |

| Key Parameters | (q{max}): Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)(KL): Langmuir constant related to affinity (L/mg) [1] | (K_F): Freundlich constant indicating capacity (mg/g)(n): Heterogeneity factor [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Batch Equilibrium Adsorption Studies

The primary method for generating data to fit Langmuir and Freundlich models is the batch equilibrium experiment [26].

Workflow of a standard batch adsorption experiment to generate data for isotherm modeling.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions (e.g., 100 mL each) with known, varying initial concentrations ((C_0)) of the adsorbate (e.g., heavy metal, phenol, pharmaceutical compound).

- Adsorbent Addition: Add a pre-determined, fixed mass of the adsorbent (e.g., 0.1 to 1.0 g) to each solution. The adsorbent mass should be constant across all bottles to ensure the adsorbent dose is consistent [1].

- Equilibration: Seal the bottles and agitate them in a shaker incubator at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C ± 2°C) for a predetermined period (often 24 hours) to ensure equilibrium is reached [27] [26].

- Separation: After equilibration, separate the solid adsorbent from the liquid phase using centrifugation or filtration.

- Analysis: Analyze the supernatant or filtrate to determine the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate ((C_e)) using appropriate analytical techniques (e.g., UV-Vis spectroscopy, conductivity meter, ICP-MS) [26].

- Calculation: The amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium ((qe), mg/g) is calculated using the mass balance equation: ( qe = \frac{(C0 - Ce) V}{m} ) where (V) is the volume of the solution (L), and (m) is the mass of the adsorbent (g) [1] [27].

Data Fitting and Model Selection

Once (qe) and (Ce) data pairs are obtained, they are fitted to the linear or non-linear forms of the Langmuir and Freundlich models.

Table 2: Model fitting and statistical validation approaches.

| Step | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Transforming models to linear forms (e.g., (Ce/qe) vs. (Ce) for Langmuir; log (qe) vs. log (C_e) for Freundlich) and fitting via least squares [27]. | Initial parameter estimation. |

| Non-Linear Regression | Fitting the raw ((Ce), (qe)) data directly to the non-linear model equations using iterative algorithms [27]. | Avoids bias introduced by linearization; preferred method [27]. |

| Error Function Analysis | Calculating statistical metrics like Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Hybrid Fractional Error Function (HYBRID), and Marquardt’s Percent Standard Error (MPSED) [27]. | Quantifies the deviation between experimental data and model predictions. |

| Goodness-of-Fit | Evaluating the coefficient of determination (R²) and performing Chi-square (χ²) tests [15] [27]. | Determines which model provides the best fit to the experimental data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, materials, and equipment used in adsorption isotherm studies.

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Carbon (PAC/GAC) | High-surface-area adsorbent for removing organic and inorganic contaminants from water [19]. | Used for methylene blue adsorption [19]. |

| Low-Cost Alternative Adsorbents | Economical and sustainable materials for wastewater treatment. | Oyster shell powder (for orthophosphate) [19], limestone (for copper removal) [1], crushed mollusk shells, peat moss [1]. |

| Model Adsorbates | Representative compounds used to test adsorbent performance. | Methylene blue (dye), Copper/Cadmium/Nickel (heavy metals), Phenol (organic pollutant), Orthophosphate (nutrient) [19] [1] [27]. |

| Batch Reactors | Sealed vessels (e.g., conical flasks, serum bottles) for containing the adsorbent-adsorbate mixture during equilibration [26]. | Used in all batch equilibrium studies. |

| Analytical Instruments | Quantifies adsorbate concentration before and after adsorption. | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (for colored ions/dyes), Conductivity Meter (for ionic species) [26], ICP-MS (for metals). |

The choice between the Langmuir and Freundlich models is not merely a statistical exercise but a decision based on the physical and chemical nature of the adsorbent-adsorbate system. The Langmuir model is most appropriate for systems that likely involve monolayer, chemical adsorption onto a homogeneous surface with a finite capacity, such as the adsorption of methylene blue onto activated carbon [19]. In contrast, the Freundlich model is often a better fit for physical adsorption processes on heterogeneous surfaces, such as phosphate sorption in diverse tropical soils [3] or copper removal by limestone [1]. Researchers should prioritize non-linear regression coupled with robust statistical error analysis to objectively determine the model that most accurately describes their experimental data, ensuring more reliable predictions for process design and optimization.

Practical Application and Data Analysis Methodologies

The analysis of adsorption data is a fundamental process in environmental science, materials research, and pharmaceutical development, providing critical insights into the interaction between substances and surfaces. The Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models represent two cornerstone mathematical approaches for describing these adsorption equilibria. While the Langmuir model originates from theoretical assumptions of homogeneous monolayer adsorption, the Freundlich equation serves as an empirical powerhouse for characterizing heterogeneous systems. The transformation of these models into linear forms has historically dominated experimental practice, enabling researchers to extract parameters through simple linear regression. However, advances in computational power and statistical understanding have revealed significant limitations in these linearized forms, prompting a paradigm shift toward non-linear regression techniques. This guide objectively compares the performance, application, and data fitting capabilities of both linear and non-linear implementations of these classic models, providing researchers with evidence-based protocols for selecting optimal approaches based on their specific experimental systems and research objectives.

Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption Models

Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm

The Langmuir adsorption model, developed by Irving Langmuir in 1916, hypothesizes monolayer adsorption onto a surface containing a finite number of identical binding sites [24] [22]. The model operates under several key assumptions: (1) the adsorbent surface is homogeneous and flat, (2) all adsorption sites are energetically equivalent, (3) each site can accommodate only one adsorbate molecule, (4) no interactions occur between adsorbed molecules, and (5) adsorption is reversible [24] [18]. These assumptions create an idealized system where the energy of adsorption is constant across all sites and independent of surface coverage.

The fundamental Langmuir equation is expressed as:

[ qe = \frac{qm \cdot KL \cdot Ce}{1 + KL \cdot Ce} ]

Where:

- ( q_e ) = amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g)

- ( q_m ) = maximum adsorption capacity corresponding to complete monolayer coverage (mg/g)

- ( K_L ) = Langmuir constant related to adsorption energy (L/mg)

- ( C_e ) = equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in solution (mg/L) [1] [22]

The model finds particular relevance in systems where chemical adsorption dominates and surface homogeneity can be reasonably assumed. Its ability to predict a maximum adsorption capacity (( q_m )) makes it invaluable for estimating the theoretical limits of adsorption systems in water treatment and pharmaceutical applications.

Freundlich Adsorption Isotherm

In contrast to the theoretically-derived Langmuir model, the Freundlich isotherm emerged as an empirical relationship to describe adsorption behavior on heterogeneous surfaces [18] [16]. First proposed by Herbert Freundlich in 1909, this model does not assume a maximum adsorption capacity but rather describes multilayer adsorption with a distribution of binding site energies.

The fundamental Freundlich equation is expressed as:

[ qe = KF \cdot C_e^{1/n} ]

Where:

- ( q_e ) = amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g)

- ( K_F ) = Freundlich constant indicative of adsorption capacity (mg/g)

- ( 1/n ) = heterogeneity factor representing adsorption intensity (dimensionless)

- ( C_e ) = equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in solution (mg/L) [1] [18] [16]

The Freundlich model particularly excels in describing adsorption on complex, heterogeneous surfaces like soils, activated carbon, and biological materials. The parameter ( 1/n ) provides valuable information about adsorption favorability: values between 0.1 and 1.0 indicate favorable adsorption, while values closer to zero suggest greater surface heterogeneity [18] [17]. Unlike the Langmuir model, Freundlich does not predict saturation of the surface, making it more applicable across wider concentration ranges for many real-world systems.

Linear versus Non-Linear Data Fitting Approaches

Linear Transformation Methods

The transformation of non-linear isotherm equations into linear forms has been historically prevalent due to computational simplicity and accessibility. These linearizations allow researchers to extract parameters using basic linear regression techniques, but each transformation introduces specific statistical distortions.

Table 1: Linear Forms of Langmuir and Freundlich Isotherm Equations

| Isotherm Model | Linear Form | Plot Type | Parameters from Plot | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | ( \frac{Ce}{qe} = \frac{1}{KL \cdot qm} + \frac{Ce}{qm} ) | ( Ce/qe ) vs ( C_e ) | Slope = ( 1/qm ), Intercept = ( 1/(KL \cdot q_m) ) | Overemphasizes low-concentration data; distorts error structure |

| Langmuir | ( \frac{1}{qe} = \frac{1}{qm} + \frac{1}{KL \cdot qm} \cdot \frac{1}{C_e} ) | ( 1/qe ) vs ( 1/Ce ) | Slope = ( 1/(KL \cdot qm) ), Intercept = ( 1/q_m ) | Overemphasizes high-concentration data; poor at low concentrations |

| Freundlich | ( \log qe = \log KF + \frac{1}{n} \log C_e ) | ( \log qe ) vs ( \log Ce ) | Slope = ( 1/n ), Intercept = ( \log K_F ) | Alters error distribution; biases parameter estimates |

The linear Langmuir form (( Ce/qe ) vs ( Ce )) remains the most widely used linearization, providing ( qm ) from the slope and ( K_L ) from the intercept [22]. Similarly, the logarithmic Freundlich transformation enables straightforward parameter estimation through linear regression of log-transformed data [18] [16]. However, these linearizations fundamentally alter error distribution and weighting across the data range. The logarithmic transformation particularly compresses the error structure, giving unequal weight to data points and potentially biasing parameter estimates [17].

Non-Linear Regression Approach

Non-linear regression techniques fit model parameters directly to the untransformed data, maintaining the intrinsic error structure and providing statistically superior parameter estimates. This approach minimizes the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted ( q_e ) values using iterative computational algorithms.

The fundamental non-linear equations are:

Langmuir non-linear form: [ qe = \frac{qm \cdot KL \cdot Ce}{1 + KL \cdot Ce} ]

Freundlich non-linear form: [ qe = KF \cdot C_e^{1/n} ]

Non-linear fitting preserves the homoscedastic nature of experimental errors (assuming constant variance in ( q_e )) and provides unbiased parameter estimates with more realistic confidence intervals. Modern statistical software packages (R, Python SciPy, Origin, GraphPad Prism) have made non-linear regression accessible to researchers across disciplines. The direct fitting approach also allows for more sophisticated model comparison using information-theoretic approaches like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), enabling objective selection between competing models based on their ability to explain data with minimal parameters.

Comparative Performance in Experimental Systems

Direct comparisons of linear and non-linear fitting approaches reveal significant differences in parameter estimation and model accuracy. A study on copper removal by limestone adsorbent demonstrated that the Freundlich model provided better fit to experimental data compared to the Langmuir model, with the non-linear approach accurately capturing the adsorption behavior across varying initial concentrations [1]. The Freundlich parameters obtained were ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g and ( n = 1.58 ) l/mg, with high coefficient of determination [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Isotherm Model Performance in Experimental Systems

| Adsorption System | Best-Fitting Model | Model Parameters | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper on limestone | Freundlich (non-linear) | ( K_F = 0.010 ) mg/g, ( n = 1.58 ) | High R² | [1] |

| Hydroquinone on carbonate rocks | Langmuir (non-linear) | ( qm = 45.2 ) mg/g (25°C), ( KL = 0.243 ) L/mg | R² = 0.99 | [28] |

| Arsenic on activated carbon | Modified Langmuir-Freundlich | Combined parameters | R² = 0.99 | [15] |

For hydroquinone adsorption on carbonate rocks, the Langmuir model demonstrated excellent fit with non-linear regression, revealing temperature-dependent parameters with ( q_m ) decreasing from 45.2 mg/g at 25°C to 34.2 mg/g at 90°C [28]. The spontaneous and exothermic nature of the process was confirmed through thermodynamic analysis [28]. In complex multi-component systems, modified models like the Extended Langmuir-Freundlich have shown superior performance for simultaneous adsorption of arsenic and fluoride on activated carbon, with R² values of 0.99 and minimal error metrics [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Batch Adsorption Experiments