Machine Learning for Chemical Life Cycle Assessment: Predicting Toxicity and Environmental Impacts

This article explores the integration of machine learning (ML) with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to address critical data gaps in chemical toxicity and environmental impact evaluation.

Machine Learning for Chemical Life Cycle Assessment: Predicting Toxicity and Environmental Impacts

Abstract

This article explores the integration of machine learning (ML) with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to address critical data gaps in chemical toxicity and environmental impact evaluation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational principles to advanced applications. It covers how ML models like Extreme Gradient Boosting and Neural Networks are used to predict characterization factors and fill missing inventory data. The content also addresses crucial challenges including uncertainty quantification, model explainability, and data quality, while providing a framework for validating and comparing different algorithmic approaches. By synthesizing current methodologies and future directions, this review serves as a guide for employing ML to create more robust, predictive, and transparent chemical LCAs, ultimately supporting safer and more sustainable chemical design.

The Convergence of Machine Learning and Chemical LCA: Core Concepts and Urgent Data Needs

The Critical Data Gap in Chemical Life Cycle Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of products, processes, and services across their entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [1] [2]. For chemicals, toxicity assessment represents a particularly challenging dimension, with impacts categorized into human toxicity (adverse health effects on humans) and ecotoxicity (harmful effects on ecosystems) [2]. However, the comprehensive application of LCA to chemicals is severely hampered by a fundamental challenge: widespread missing data in life cycle inventory (LCI) and characterization factors for toxicity impacts [3] [4].

The scale of this problem is substantial. The chemical sector utilizes over 20,000 chemicals commercially in Europe alone, with more than 80 million described in scientific literature [4]. Existing LCA databases like GaBi and Ecoinvent contain thousands of datasets, yet critical gaps persist for many commercially relevant chemicals [4]. This data scarcity introduces significant uncertainty into toxicity assessments, limiting the reliability and applicability of LCA for sustainable chemical design and regulation [2]. When toxicity data is missing or incomplete, LCA practitioners must rely on assumptions and simplifications that may not accurately reflect real-world impacts, potentially leading to suboptimal environmental decisions [5].

Traditional Approaches and Their Limitations

Established Methods for Handling Data Gaps

To address missing inventory and impact assessment data, several traditional approaches have been developed:

Table 1: Traditional Approaches for Handling Missing LCA Data for Chemicals

| Method | Description | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Modeling [4] | Uses reaction equations and stoichiometric calculations to estimate resource consumption and emissions. | Often omits important reaction components like catalysts; limited to few impact categories. |

| Proxy Data [4] | Uses data from similar chemicals or processes as substitutes for missing data. | May not accurately represent the specific chemical's environmental profile. |

| Expert Elicitation [4] | Relies on expert judgment to estimate missing data points. | Subjective and can introduce individual bias; difficult to standardize. |

| Process Simulation [6] | Uses first-principle models to simulate chemical processes and estimate flows. | Can be infeasible for complex systems; computationally intensive. |

The USEtox model has emerged as a scientific consensus model for characterizing human toxicity and ecotoxicity impacts in LCA, providing characterization factors for thousands of chemicals [7] [2]. Similarly, the ReCiPe methodology offers characterization factors for toxicity at both midpoint and endpoint levels [2]. These models translate inventory data (e.g., kilograms of a chemical emitted) into impact scores by considering the environmental fate, exposure, and inherent hazard of chemicals [2]. However, they still depend on the availability of high-quality input data, which is often lacking.

Inherent Challenges in Toxicity Assessment

Beyond data availability, fundamental methodological challenges complicate toxicity assessment in LCA:

- Spatial and Temporal Variability: Toxicity impacts can vary significantly based on emission location and timing, yet most LCA models use generic averaging [5] [2].

- Mixture Toxicity: Humans and ecosystems are exposed to complex chemical mixtures, while LCA typically assesses substances individually, potentially missing synergistic effects [2].

- Linearity and Additivity Assumptions: Most models assume linear dose-response relationships and additive effects, which may not reflect non-linear toxicological realities [2].

- Near-Field vs. Far-Field Exposure: Traditional LCIA often focuses on "far-field" environmental emissions, potentially underestimating "near-field" exposures during product use or occupational settings [5].

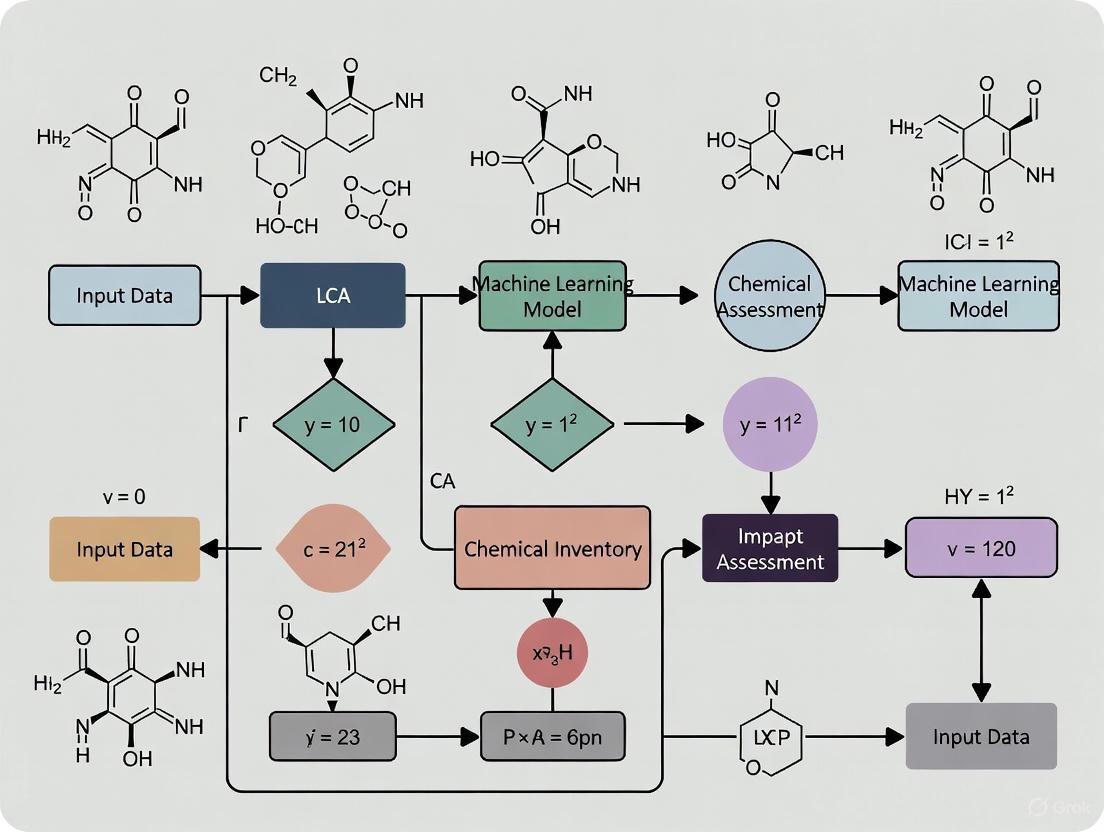

Figure 1: Traditional approaches for handling missing toxicity data in LCA and their key limitations

Machine Learning Solutions for Toxicity Prediction

Machine Learning Frameworks for LCA

Machine learning (ML) offers promising solutions to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches. ML techniques can handle complex, high-dimensional datasets and identify non-linear patterns that traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models might miss [7] [1]. The integration of ML into LCA follows several conceptual frameworks:

- Surrogate Modeling: ML models replace complex process simulations or impact assessment calculations, significantly improving computational efficiency [6].

- Data Imputation: ML algorithms predict missing life cycle inventory data based on patterns learned from existing databases [1].

- Characterization Factor Prediction: ML models directly estimate characterization factors for toxicity impacts using chemical structure information [8].

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in Chemical LCA

| ML Application | Key Function | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Ecotoxicity (HC50) Prediction [7] | Predicts hazardous concentration values for chemicals using latent space representations. | Autoencoders, Random Forest, Fully Connected Neural Networks |

| Characterization Factor Prediction [8] | Estimates characterization factors for human toxicity and ecotoxicity. | XGBoost, Gaussian Process Regression, Deep Neural Networks |

| Life Cycle Inventory Completion [9] | Fills gaps in inventory data for chemical production processes. | Artificial Neural Networks, Linear Regression, Random Forests |

| Material Optimization [10] | Balances mechanical performance and environmental impacts in material design. | Principal Component Analysis, ANN with Multi-Objective Optimization |

Experimental Protocols and Model Architectures

Autoencoder Model for Ecotoxicity Prediction

A state-of-the-art approach for predicting chemical ecotoxicity (HC50) utilizes autoencoder models to learn latent space chemical representations [7]. The experimental protocol involves:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Source HC50 values from the USEtox database for 1,815 chemicals [7].

- Calculate 691 chemical features from multiple sources: 11 physiochemical properties, 797 theoretical molecular descriptors from EPA's Toxicity Estimation Software Tool, and 51 physically significant properties from QikProp [7].

- Remove highly uncertain and duplicate variables to obtain a final set of 691 input features [7].

Model Architecture and Training:

- Implement an autoencoder with encoder and decoder components parameterized by neural networks.

- The encoder reduces high-dimension input features (691) to lower-dimension embeddings (e.g., 50-100 dimensions).

- The decoder reconstructs input features from the lower-dimension embeddings.

- Train the model by minimizing reconstruction loss between original and reconstructed features.

- Use the learned latent space embeddings as input to a simple linear layer or other supervised learning model to predict HC50 values.

Performance Evaluation:

- This approach achieved R² = 0.668 ± 0.003 and mean absolute error (MAE) = 0.572 ± 0.001 for HC50 prediction, outperforming traditional methods like principal component analysis (PCA) and standard machine learning models using raw input features [7].

Characterization Factor Prediction Workflow

For predicting characterization factors (CFs) aligned with the EU Environmental Footprint methodology, the following workflow has been developed [8]:

Data Preparation:

- Extend chemicals from Environmental Footprint version 3 database.

- Generate molecular descriptors from SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) strings.

Model Development and Selection:

- Train and evaluate three ML models: extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), Gaussian process regression, and deep neural networks.

- Implement a clustering step to guide model selection for new compounds.

- XGBoost consistently performed best, achieving R² values up to 0.65 and 0.61 for ecotoxicity and human toxicity (seas water, continent), respectively [8].

Application Protocol:

- Assign new chemicals to clusters based on their molecular properties.

- Select the best-performing ML model tailored for each cluster.

- Predict characterization factors for chemicals with missing data.

- Integrate predicted CFs directly into LCA studies.

Figure 2: Machine learning workflow for predicting missing toxicity data in chemical LCA

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Enhanced LCA Toxicity Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Function in LCA Toxicity Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Databases | USEtox [7] [2], Environmental Footprint [8], Ecoinvent [4] | Provide foundational data on characterization factors and inventory data for chemicals. |

| Chemical Property Databases | EPA ECOTOX [2], ECHA REACH [2], QikProp [7] | Supply physicochemical properties, ecotoxicity, and human health toxicity data for chemicals. |

| Molecular Descriptors | SMILES Strings [8], EPA Toxicity Estimation Software [7] | Generate standardized chemical representations and theoretical molecular descriptors for ML models. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | XGBoost [8], Autoencoders [7], Artificial Neural Networks [9] [10] | Build predictive models for toxicity endpoints and characterization factors. |

| Chemical Categorization Tools | Verhaar Scheme/Toxtree [7], ClassyFire [8] | Classify chemicals by mode of action or chemical taxonomy to guide model selection. |

Case Studies and Validation

The practical implementation of ML approaches for addressing toxicity data gaps has demonstrated significant potential across multiple applications:

In the textile sector, an ML workflow was developed to predict characterization factors for both human toxicity and ecotoxicity. The study revealed that including predicted CFs for chemicals that were originally missing from databases increased the total human toxicity score by at least 4 orders of magnitude, dramatically altering the environmental profile and conclusions of the LCA [8]. This case highlights the critical importance of addressing data gaps rather than simply omissing chemicals with unknown toxicity impacts.

For impact-resistant fiber-reinforced cement-based composites, a three-stage integrated framework combining experimental test databases, LCA, and ML modeling successfully balanced mechanical performance with environmental impacts. The ML model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting global warming potential and energy dissipation, enabling multi-objective optimization that identified Pareto-optimal solutions representing the best trade-offs between performance and sustainability [10].

The RREM (Research, Reaction, Energy, and Modeling) approach represents a hybrid methodology that combines traditional process-based modeling with data-driven elements to fill LCI gaps for chemicals. Applied to 60 chemicals, this method provided environmental profiles including global warming potential, acidification potential, and eutrophication potential, demonstrating the feasibility of generating reasonable estimates when complete data are unavailable [4].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Despite promising advances, several challenges must be addressed to fully realize the potential of ML for toxicity assessment in chemical LCA:

Data Quality and Availability: ML models require large, high-quality training datasets. Current models are often trained on limited datasets, with over 70% of studies using fewer than 1,500 samples [9]. Establishing larger, open, and transparent LCA databases for chemicals is essential for future progress [3].

Model Interpretability and Uncertainty: The "black box" nature of some complex ML models raises concerns about interpretability and transparency in regulatory and decision-making contexts [1]. Enhancing model explainability and comprehensive uncertainty quantification should be research priorities.

Integration with Traditional Workflows: Effectively incorporating ML predictions into established LCA frameworks and software tools requires careful attention to methodological consistency and stakeholder acceptance [1].

Domain-Specific Model Development: Different chemical classes may require tailored modeling approaches. Future research should explore specialized models for particular substance groups (e.g., metals, polymers, nanomaterials) with distinct toxicological profiles and environmental fate characteristics [5].

The integration of emerging technologies, particularly large language models (LLMs), is expected to provide new impetus for database building and feature engineering in chemical LCA [3]. Similarly, physics-informed machine learning (PIML) approaches that incorporate domain knowledge and physical constraints offer promise for more robust and scientifically grounded predictions [1].

As these technologies mature, ML-enhanced LCA has the potential to transform chemical safety assessment and sustainable design practices, ultimately supporting the development of chemicals and materials that are safer and more sustainable throughout their life cycles.

Why Machine Learning? Addressing Data Gaps and Computational Hurdles in Traditional LCA

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology (ISO 14040/14044) for quantifying the environmental impacts of products, processes, and services across their entire life cycle [1]. Despite its foundational role in sustainability science, traditional LCA faces significant methodological challenges that limit its accuracy, efficiency, and applicability. Conventional LCA methodologies are heavily dependent on extensive life cycle inventory (LCI) datasets that are often incomplete, inconsistent, or static in nature [1] [11]. These limitations introduce substantial uncertainty into impact assessments and often require practitioners to make simplifying assumptions that reduce reliability.

The chemical and pharmaceutical sectors face particularly acute challenges, where traditional LCA studies are characterized by slow speeds and high costs, limiting their utility in rapid product development and assessment cycles [3]. Furthermore, the bottom-up LCA framework often struggles with system boundary truncation, data gap challenges, and an inability to incorporate temporal, geographical, and technological variations [11]. This static 'snapshot' analysis approach fails to capture the dynamic nature of real-world production systems and supply chains, potentially leading to decisions based on outdated or non-representative information.

Fundamental Limitations of Conventional LCA Approaches

Data Scarcity and Quality Challenges

The life cycle inventory (LCI) phase constitutes the most data-intensive stage of LCA, requiring detailed accounting of all material and energy inputs and outputs associated with each process within defined system boundaries [1]. For chemicals and specialized materials, this often encounters critical data gaps:

- Missing Inventory Data: Many chemicals and functional materials lack comprehensive life cycle inventory data, forcing practitioners to rely on proxy values or approximations that limit relevance and accuracy [11].

- Outdated Database Information: Many LCA databases contain outdated, incomplete, or generic datasets that fail to represent technological advancements, specific sector contexts, or geographical locations [12].

- Foreground Data Gaps: Company-specific process data is frequently missing, particularly for emerging technologies or novel substances, making it impossible to replace aggregates/proxy data with accurate primary data [12].

Computational and Methodological Constraints

Beyond data quality issues, traditional LCA faces inherent methodological limitations that affect its computational efficiency and practical implementation:

- Static Analytical Framework: Conventional LCA provides static assessments that struggle to incorporate real-time changes in supply chains, energy mixes, or operational conditions [13].

- High Computational Burden: Bottom-up LCA calculation speeds are constrained due to the time-consuming and costly nature of data collection and processing [11].

- Limited Temporal Resolution: Most LCA tools struggle to incorporate uncertainty and the time dimension in model design, resulting in assessments that cannot adapt to dynamic market conditions or technological evolution [12].

Table 1: Core Limitations of Traditional LCA in the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sectors

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenges | Impact on Assessment Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Data Availability | Missing life cycle inventory data for novel chemicals; reliance on proxy values [11] | Reduced relevance and accuracy of environmental impact profiles |

| Data Quality | Outdated, incomplete, or generic datasets in LCA databases [12] | Limited representation of technological advancements and geographical context |

| Computational Efficiency | Time-consuming data collection and processing [11] | Extended assessment timelines incompatible with rapid development cycles |

| Temporal Dynamics | Static nature unable to capture real-time changes in supply chains or energy mixes [13] | Decisions based on outdated or non-representative information |

Machine Learning as a Transformative Solution for LCA

Machine Learning (ML), a subfield of artificial intelligence, encompasses computer algorithms that improve automatically through experience and can identify complex patterns in data without explicit programming [9]. The integration of ML techniques offers promising solutions to overcome traditional LCA challenges by leveraging their ability to handle complex, high-dimensional, and non-linear datasets [1].

How ML Addresses Core LCA Limitations

ML technologies excel in several key areas that directly correspond to LCA's methodological gaps:

- Automated Data Imputation: ML algorithms can automatically identify patterns in existing LCI databases and predict missing values, significantly reducing data gaps [1].

- Enhanced Computational Efficiency: Regression models, generative techniques, and optimization algorithms can reduce the number of indicators required while maintaining predictive accuracy, improving computational efficiency [1].

- Dynamic Modeling Capabilities: Unlike static LCA models, ML approaches can incorporate real-time environmental and operational parameters, enabling dynamic impact assessments that reflect changing conditions [1] [13].

- High-Dimensional Pattern Recognition: ML techniques can decipher complexity in datasets, enable prediction, and discover new knowledge and patterns hidden behind the datasets that might be imperceptible through conventional analytical methods [9].

Table 2: ML Solutions to Traditional LCA Challenges

| Traditional LCA Challenge | ML Solution Approach | Key ML Techniques Applied |

|---|---|---|

| Data Gaps in Life Cycle Inventory | Predictive imputation of missing inventory data [1] | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Gaussian Process Regression [9] |

| Slow Calculation Speed | Development of simplified LCA models using reduced proxy metrics [1] | Multilinear regression with mixed-integer linear programming [1] |

| Limited Temporal Resolution | Integration of real-time operational and environmental parameters [1] | Reinforcement learning, deep neural networks [12] |

| High-Dimensional Data Complexity | Pattern discovery in complex environmental impact relationships [9] | Unsupervised learning, clustering algorithms, dimension reduction [9] |

Technical Framework for ML-Enhanced LCA

Phase-Specific ML Integration Across the LCA Workflow

The integration of machine learning strengthens LCA across all four phases defined by ISO 14040/14044 standards, with specific technical approaches tailored to each phase's unique requirements [1].

ML Techniques for Chemical and Pharmaceutical Applications

For chemical and pharmaceutical LCA applications, molecular-structure-based machine learning represents the most promising technology for rapid prediction of life-cycle environmental impacts [3]. This approach leverages advances in training datasets, feature engineering, and model architectures specifically tailored to chemical compounds:

- Molecular Descriptor Engineering: Construction of efficient chemical-related descriptors and identification of features most pertinent to LCA results represent pivotal steps in next-generation modeling [3].

- Hybrid Modeling Frameworks: Integration of large language models (LLMs) is expected to provide new impetus for database building and feature engineering in chemical LCA [3].

- Transfer Learning Applications: Using LCA data from one chemical system or cultivation method to model another, addressing data scarcity through knowledge transfer [14].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Methodologies

Protocol 1: Molecular-Structure-Based Impact Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for predicting environmental impacts of chemicals directly from molecular structures, representing a cutting-edge approach that bypasses traditional data-intensive LCI phases [3].

Step 1: Database Curation and Preprocessing

- Establish a large, open, and transparent LCA database for chemicals encompassing diverse chemical types

- Apply rigorous data quality assessment and external validation procedures to ensure high-quality LCA data

- Standardize impact assessment results across consistent functional units and system boundaries

Step 2: Molecular Feature Engineering

- Compute molecular descriptors capturing structural, electronic, and topological properties

- Apply feature selection algorithms to identify descriptors most predictive of environmental impacts

- Utilize large language models (LLMs) for advanced feature engineering and molecular representation

Step 3: Model Training and Validation

- Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified sampling

- Train multiple ML architectures including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and Gradient Boosting methods

- Implement k-fold cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters and prevent overfitting

- Validate model performance against holdout test sets using metrics including RMSE, MAE, and R²

Step 4: Impact Prediction and Uncertainty Quantification

- Deploy trained models to predict environmental impacts for novel chemical structures

- Apply conformal prediction techniques to generate prediction intervals quantifying uncertainty

- Implement model interpretation methods (SHAP, LIME) to identify structural features driving environmental impacts

Protocol 2: Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference for Agricultural Chemical Assessment

This protocol details the methodology for predicting environmental impacts in agricultural systems, particularly relevant for assessing pharmaceutical compounds with environmental exposure pathways [14].

Step 1: Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Compile LCI data for agricultural production systems including energy, fertilizer, and pesticide inputs

- Generate output data for impact categories including global warming potential, eutrophication, and ecotoxicity

- Normalize data to consistent functional units (e.g., per kg of active pharmaceutical ingredient)

Step 2: Fuzzy Inference System Development

- Define input and output variables with associated membership functions

- Implement three fuzzy inference system generation approaches: Fuzzy C-Means (FCM), Subtractive Clustering (SC), and Grid Partitioning (GP)

- Expert elicitation to establish fuzzy rule bases mapping inputs to environmental impacts

Step 3: Neural Network Training

- Train Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) to optimize membership function parameters

- Implement hybrid learning algorithm combining least-squares and backpropagation methods

- Validate model predictions against empirical LCA results computed using established databases and software

Step 4: Model Deployment and Transfer Learning

- Deploy trained ANFIS models to predict impacts for similar agricultural chemical production systems

- Implement transfer learning to adapt models to new geographic regions or production practices

- Continuous model updating incorporating new LCA data as it becomes available

Performance Evaluation of ML Models in LCA

Comparative Analysis of ML Algorithm Performance

Recent research has conducted systematic evaluation of different ML models in LCA applications, providing empirical evidence for algorithm selection based on performance metrics [15]. The ranking of algorithms based on their effectiveness for LCA predictions using multi-criteria decision-making methods reveals significant performance differences:

Table 3: Performance Ranking of ML Algorithms for LCA Applications [15]

| ML Algorithm | Performance Score | Strengths for LCA Applications | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.6412 | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; memory efficient | Kernel selection critical; less effective with noisy data |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) | 0.5811 | Handles missing data well; high predictive accuracy | Computational intensity; parameter tuning required |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | 0.5650 | Pattern recognition in complex data; non-linear modeling | Large data requirements; black box interpretation challenges |

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.5353 | Robust to outliers; feature importance quantification | Potential overfitting; less interpretable than single trees |

| Decision Trees (DT) | 0.4776 | High interpretability; handles mixed data types | Instability with small data variations; overfitting tendency |

| Linear Regression (LR) | 0.4633 | Computational efficiency; model interpretability | Limited capacity for complex non-linear relationships |

| Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) | 0.4336 | Combines learning and explicit knowledge representation | Computational complexity; rule explosion with many inputs |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | 0.2791 | Native uncertainty quantification; flexible non-parametric | Computational limitations with large datasets |

Case Study: Predictive Accuracy in Agricultural LCA

A recent study applying Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) to predict CO₂ equivalent emissions for strawberry production demonstrated AI's potential to transform LCA, enabling more efficient, data-driven sustainability assessments [14]. The research successfully predicted environmental impacts for open-field strawberry production using greenhouse strawberry data, bridging data gaps through machine learning.

Among three fuzzy inference system generation approaches evaluated, Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) exhibited the highest accuracy when validated against emissions computed using the Ecoinvent database and SimaPro software [14]. This case study demonstrates the viability of transfer learning in LCA, where models trained on one system can be adapted to predict impacts for related systems with limited data.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for ML-Enhanced LCA

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ML-LCA Integration

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in ML-LCA Research |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Databases | Ecoinvent 3.10 [14], SimaPro databases [14] | Provide quality-checked life cycle inventory and assessment information for model training and validation |

| ML Frameworks | Python Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implement and train machine learning algorithms for predictive LCA modeling |

| Fuzzy Logic Tools | MATLAB Fuzzy Logic Toolbox [14] | Develop fuzzy inference systems for handling uncertainty and expert knowledge integration |

| Model Interpretation Libraries | SHAP, LIME, ELI5 | Enhance transparency and explainability of ML models through feature importance quantification |

| Chemical Descriptor Platforms | RDKit, Dragon, PaDEL | Compute molecular descriptors from chemical structures for molecular-structure-based prediction |

| Hybrid Modeling Environments | Python-MATLAB integration, R-Python bridges | Enable implementation of complex hybrid AI architectures combining multiple paradigms |

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Despite the promising potential of ML-enhanced LCA, several challenges must be addressed to realize its full benefits. Key implementation barriers include:

- Data Quality and Availability: The development of reliable ML models requires large, high-quality datasets, yet many LCA databases suffer from outdated, sparse, or irrelevant data [12].

- Model Interpretability: The "black box" nature of many complex ML algorithms raises concerns about transparency and stakeholder trust, necessitating advances in explainable AI (XAI) [1].

- Integration Complexity: Successful implementation requires interdisciplinary collaboration between LCA experts, ML specialists, and domain scientists, presenting organizational and communication challenges [9].

Future research directions should prioritize standardized approaches for database development, enhanced model transparency through explainable AI techniques, and the integration of large language models for improved natural language processing of LCA literature and reports [3] [12]. Furthermore, the development of dynamic ML-driven LCA frameworks that incorporate real-time data streams through IoT sensors and digital twins represents a promising frontier for next-generation sustainability assessment [13].

The integration of machine learning into life cycle assessment marks a paradigm shift from static, retrospective analyses toward dynamic, predictive sustainability intelligence. By systematically addressing data gaps and computational hurdles, ML-enhanced LCA enables more robust, transparent, and actionable environmental assessments essential for guiding sustainable development in the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a systematic, quantitative framework for evaluating the environmental footprint of products and processes across their entire lifespan. For researchers in chemical and pharmaceutical development, mastering LCA methodology is crucial for designing sustainable compounds and manufacturing processes. The comprehensive scope of LCA requires extensive data collection across complex supply chains and advanced data analytics, creating significant opportunities for machine learning (ML) integration [9]. This guide details three core LCA components—Life Cycle Inventory (LCI), Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA), and Characterization Factors (CFs)—and frames them within emerging research that applies ML for rapid environmental impact prediction.

The standard LCA framework, as defined by ISO 14040, consists of four iterative phases, with LCI and LCIA forming the central analytical core [16] [17]. Figure 1 illustrates this structured workflow and the critical role of CFs within it.

Figure 1. The LCA Framework and Workflow. The diagram shows the four phases of a Life Cycle Assessment, highlighting the position of the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) and Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA). The characterization step within LCIA, which relies on Characterization Factors (CFs), is a focal point for methodological development.

Core Terminology and Definitions

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) is the second phase of LCA and often the most time-consuming. It involves the detailed compilation and quantification of all input and output flows of a product system throughout its life cycle [16] [18]. Think of the LCI as a comprehensive "shopping list" of everything required for the product system, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [16].

- Inputs: Raw materials, different types of energy, water, and logistics.

- Outputs: Emissions to air, land, or water, and waste generation [16].

- Data Types:

- Foreground Data: Specific inputs and outputs directly related to the processes within the studied product's life cycle (e.g., specific chemical synthesis data from a lab or plant).

- Background Data: Generic data from environmental databases (e.g., ecoinvent) that provide impact information based on industry averages for common materials and energy sources [16].

The main challenge of the LCI phase is its iterative nature and the potential need for data assumptions when specific information is unavailable, which must be carefully documented for transparency [16].

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) is the third LCA phase. It translates the raw, physical data from the LCI into meaningful environmental impact scores [17] [19]. This is the "what does it mean" step, where the inventory of flows is analyzed for its potential environmental consequences [19].

The LCIA phase involves multiple steps, with characterization being the core scientific step. Figure 2 details the specific procedures within the LCIA phase that convert elementary flows into impact scores.

Figure 2. The LCIA Process: From Flows to Impact Scores. This diagram shows how elementary flows from the LCI are categorized and then converted into quantifiable impact scores using Characterization Factors (CFs). Optional steps like normalization and weighting can further process these scores.

Characterization Factors (CFs)

Characterization Factors (CFs) are the fundamental conversion factors used in the characterization step of the LCIA. They express how much a single unit of mass of an elementary flow (e.g., 1 kg of a chemical emission) contributes to a specific impact category relative to a reference substance [17] [20].

- Function: CFs provide a standardized measure to compare the relative impact of different substances. For example, in the "climate change" category, methane (CH₄) has a Global Warming Potential (GWP) 34 times greater than carbon dioxide (CO₂) over a 100-year horizon. Therefore, 1 kg of CH₄ is equated to 34 kg of CO₂ equivalents (CO₂-eq) [17].

- Calculation: For toxicity-related impacts, CFs are derived through a systematic modeling procedure that considers the chemical's fate (where it goes and how long it persists), exposure (how organisms encounter it), and effects (its inherent toxicity) [20].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Structured Data: Characterization Factors in Practice

Table 1 provides concrete examples of CFs for different impact categories, illustrating how disparate emissions can be compared on a common scale.

Table 1: Examples of Impact Categories, Flows, and Characterization Factors

| Impact Category | Example Elementary Flow | Characterization Factor (Reference) | Impact Score Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming [21] | CO₂ | 1 (CO₂) | kg CO₂-equivalents |

| CH₄ | 34 (CO₂) | kg CO₂-equivalents | |

| Ozone Depletion [21] | CFC-11 | 1 (CFC-11) | kg CFC-11-equivalents |

| Eutrophication [21] | PO₄³⁻ | 1 (PO₄³⁻) | kg PO₄³⁻-equivalents |

| Acidification [21] | SO₂ | 1 (SO₂) | kg SO₂-equivalents |

Recent research focuses on developing highly spatially differentiated CFs to assess specific practices. For instance, a study on wheat cultivation quantified CFs for ecosystem services, finding that conventional tillage with straw removal resulted in a nitrogen loss (affecting water purification) of 13.29 kg N·ha⁻¹·y⁻¹, whereas conservation practices led to a gain of -0.46 kg N·ha⁻¹·y⁻¹ [22].

Experimental Protocols for Deriving Characterization Factors

Deriving scientifically robust CFs, particularly for toxicity, requires rigorous protocols. The process for developing ecotoxicity CFs involves a multi-step modeling procedure [20]:

- Fate Modeling: The environmental fate of a chemical describes the proportion transferred through environmental media (air, water, soil) and its degradation rate. Models simulate the chemical's distribution and persistence.

- Exposure Modeling: Multimedia fate and exposure models estimate the concentration to which ecological species or humans are exposed through various uptake routes (e.g., inhalation, ingestion).

- Effect Assessment: The inherent toxicity of the chemical is determined, typically from experimental toxicity data (e.g., LC₅₀ values from tests on fish or Daphnia). This data defines the chemical's potency.

- Factor Integration: Environmental fate, exposure, and effects are combined into a single, substance-specific characterization factor.

A critical challenge is handling missing data. Experimental data for all chemicals is incomplete. The following extrapolation methods are used to predict missing values [20]:

- Extrapolation between Chemicals: Using Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSARs) to predict a chemical's properties based on its molecular structure and similarity to chemicals with known data.

- Extrapolation between Environmental Media: Applying the equilibrium partitioning method to extrapolate toxicity values from one medium (e.g., freshwater) to another (e.g., soil).

- Extrapolation between Species: Using interspecies correlation estimation (ICE) models to extrapolate toxicity from one tested species to another untested species.

A recent PhD thesis quantified uncertainties in these methods, finding that uncertain environmental degradation half-lives and small species sample sizes contribute most to overall uncertainty. The study concluded that supplementing experimental data with interspecies correlation estimates is often the most effective way to enhance limited datasets [20].

The Machine Learning Revolution in LCA

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) into LCA addresses key limitations of traditional methods: slow speed, high cost, and data scarcity. A review of 40 studies combining ML and LCA found that ML approaches have been applied to generate life cycle inventories, compute characterization factors, estimate life cycle impacts, and support interpretation [9].

ML Applications in LCA Workflow

Table 2 summarizes how ML is being applied to overcome specific challenges in the LCA workflow, particularly for chemicals.

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in LCA for Chemicals

| LCA Stage | Challenge | ML Solution | Example & Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCI/LCIA Data Generation | Data scarcity for many chemicals; expensive and slow to generate experimentally. | Molecular-structure-based ML: Models trained on existing LCA databases to predict impacts directly from a chemical's structure. | Supervised Learning (e.g., ANN) models predict LCIA results, filling data gaps for chemicals without full LCA [3] [9]. |

| Characterization Factor Development | Uncertainty in fate, exposure, and effect data for toxicity CFs. | QSARs and other predictive models: ML enhances QSAR models to more accurately predict missing physicochemical and toxic properties. | ML models predict missing data for CF calculation, such as toxicity values or degradation rates, improving coverage and reducing uncertainty [9] [20]. |

| Pattern Discovery & Hotspot Identification | Complexity of interpreting large LCI/LCIA datasets to find key levers for improvement. | Unsupervised Learning (e.g., clustering): Identifies hidden patterns and groups processes or products with similar environmental profiles. | Pattern discovery in inventory data helps prioritize areas for impact reduction [9]. |

Over 70% of the reviewed studies used training datasets with fewer than 1500 samples, indicating a significant opportunity for improvement through larger, open-access LCA databases for chemicals [9]. Future directions include integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) to assist in database building and feature engineering, and applying deep learning to further improve predictions [3] [9].

Workflow for ML-Augmented LCA

Figure 3 illustrates how ML models can be integrated into the traditional LCA framework to create a rapid prediction tool for chemical environmental impacts.

Figure 3. Machine Learning for Rapid Chemical Impact Prediction. This diagram shows a data-driven workflow where ML models are trained on existing LCA data and chemical structures. Once trained, these models can rapidly predict the LCI or LCIA results for new chemicals, bypassing the more resource-intensive traditional LCA process.

Table 3 lists key resources and computational tools essential for researchers conducting LCA or developing ML models for chemical impact prediction.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for LCA and ML-Based Prediction

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ecoinvent Database [18] | LCI Database | Provides comprehensive, background life cycle inventory data for common materials, energy, and processes. Essential for building product system models. |

| USEtox [21] | Scientific Model | A consensus model for characterizing human and ecotoxicological impacts in LCA. Provides CFs for thousands of chemicals. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) [20] | Methodological Tool | A computational approach to predict a chemical's physicochemical properties and toxicological effects from its molecular structure. Critical for filling data gaps. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [9] | Machine Learning Algorithm | The most frequently applied ML method in LCA studies, used for tasks like predicting missing inventory data or estimating characterization factors. |

| TRACI, ReCiPe, CML [21] | LCIA Methods | Predefined sets of impact categories and characterization factors. The choice of method depends on the LCA standard and geographical focus. |

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is transforming the field of environmental impact assessment, particularly for complex systems like chemical products and drug development. Traditional LCA, while a standardized and holistic methodology, often grapples with data scarcity, high computational costs, and static modeling approaches that struggle to keep pace with dynamic industrial processes [1] [12]. The application of ML offers a powerful paradigm shift, enabling rapid predictions, handling of large and incomplete datasets, and the discovery of complex, non-linear relationships that are difficult to model with conventional methods [3] [1].

This growth is especially pertinent for the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, where the sheer number of compounds and the complexity of their synthesis pathways make traditional LCA prohibitively slow and resource-intensive. Molecular-structure-based machine learning has emerged as the most promising technology for the rapid prediction of the life-cycle environmental impacts of chemicals [3]. This technical review employs a bibliometric lens to map the evolution of this interdisciplinary field, quantify its growth, and distill the essential methodologies and tools that are shaping its future. By synthesizing findings from recent systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses, this paper provides a structured overview for researchers and professionals seeking to navigate and contribute to the rapidly expanding landscape of ML-LCA integration.

Bibliometric analyses provide a data-driven perspective on the scale and focus of ML-LCA research. The field is experiencing rapid growth, with a significant increase in the number of published articles in recent years [23] [24]. This trend is indicative of the research community's growing recognition of the synergistic potential between these two domains.

A focused bibliometric analysis examining dynamic LC studies in the building sector from 2007 to 2024 identified a total of 549 core articles within its scope, with ML-LCA recognized as a newer area showing a particularly rapid growth rate [23]. Another broader analysis evaluated the performance of different ML models across 78 peer-reviewed articles, providing a quantitative ranking of algorithms based on their effectiveness for LCA predictions [15]. The analysis of keyword co-occurrence and collaboration patterns further reveals that research is clustered around key themes such as prediction models, environmental impact indicators, and specific application areas like sustainable buildings and chemical design [23] [1].

Table 1: Top Performing ML Algorithms in LCA Applications Based on AHP-TOPSIS Ranking [15]

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Acronym | AHP-TOPSIS Score | Primary Application in LCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine | SVM | 0.6412 | Impact prediction, classification tasks |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting | XGB | 0.5811 | Handling complex, non-linear datasets |

| Artificial Neural Networks | ANN | 0.5650 | Prediction of impacts, surrogate modeling |

| Random Forest | RF | 0.5353 | Feature importance, regression tasks |

| Decision Trees | DT | 0.4776 | Interpretable models for scenario analysis |

| Linear Regression | LR | 0.4633 | Baseline modeling, simple correlations |

| Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System | ANFIS | 0.4336 | Systems with high uncertainty |

| Gaussian Process Regression | GPR | 0.2791 | Uncertainty quantification |

Key Research Trends and Methodological Protocols

The integration of ML into LCA is not monolithic; it manifests through distinct trends and well-defined methodological protocols that address specific challenges in the LCA workflow.

Trend 1: Prediction of Environmental Impacts

The most prevalent application of ML in LCA is the rapid prediction of environmental impacts, effectively creating surrogate models that bypass computationally intensive traditional calculations.

Experimental Protocol for Molecular-Structure-Based Prediction of Chemical Impacts [3]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: The objective is to predict a specific life-cycle environmental impact (e.g., Global Warming Potential) for a chemical compound based on its molecular structure. The functional unit is typically per kg of the chemical.

- Data Collection and Curation:

- Source: Gather a large, open dataset of chemicals with known LCA results (e.g., from Ecoinvent or specialized chemical LCA databases).

- Challenge: Data shortage and variable quality are major bottlenecks. Establishing large, open, and transparent LCA databases for chemicals is a critical need [3].

- Feature Engineering:

- Descriptors: Transform the molecular structure of each chemical into a numerical descriptor. This can include simple molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, polarity) or more complex fingerprints and graph-based representations.

- Feature Selection: Identify and select the molecular features most pertinent to the LCA result to improve model efficiency and accuracy [3].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Commonly used algorithms include ANN, SVM, and RF (see Table 1). The choice depends on dataset size and complexity.

- Process: The dataset is split into training and testing sets. The model is trained to learn the mapping between the molecular descriptors and the LCA impact score.

- Validation: Model performance is evaluated on the unseen test set using metrics like R², Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

Trend 2: Dynamic and Whole-Building LCA

In sectors like construction, ML is being used to move beyond static assessments to dynamic LCA that incorporates temporal, geographical, and operational data.

Methodological Protocol for Whole-Building LCA Using ML [23] [24]:

- System Boundary Definition: Define the life cycle stages of the building (product, construction, use, end-of-life) and the corresponding environmental indicators to be modeled (e.g., energy consumption, Global Warming Potential).

- Data Integration:

- Data Sources: Fuse heterogeneous data from Building Information Modeling (BIM), Geographic Information Systems (GIS), sensor data (IoT), and LCA databases.

- Input Parameters: These may include building geometry, material types, operational energy use, local climate data, and transportation distances.

- Model Development:

- Objective: To predict the whole-lifecycle environmental impacts based on the input parameters.

- Prediction: Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are the most frequently used ML method in this domain, valued for their ability to model complex, non-linear relationships between building design choices and environmental outcomes [24].

- Optimization: The trained ML model can be coupled with optimization algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) to identify building design parameters that minimize life cycle environmental impacts and cost.

Trend 3: Enhanced Data Processing and Automation

ML is being applied to overcome foundational LCA challenges related to data quality and availability across all phases of the LCA framework.

Protocol for AI-Enhanced Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis [1] [12]:

- Problem Identification: The LCI phase involves massive data collection which is often incomplete, with missing or outdated data points.

- Algorithm Selection:

- Supervised Learning: The most preferred approach, used to predict missing inventory data based on known, correlated parameters [12].

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): Large Language Models (LLMs) can be used to automatically extract and classify LCI data from technical literature, reports, and patents, significantly speeding up data acquisition [3] [12].

- Implementation:

- A model is trained on a complete subset of the LCI database.

- The trained model then imputes or predicts missing values in the larger, incomplete dataset, providing probabilistic estimates and quantifying uncertainty [1].

- Validation: Expert judgment and cross-validation are critical to ensure the AI-predicted data aligns with physical and chemical realities.

For researchers embarking on ML-LCA projects, a specific set of computational tools, algorithms, and data resources forms the essential toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for ML-LCA Integration

| Tool or Resource | Type | Function in ML-LCA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Algorithm | A versatile, non-linear model used for predicting environmental impacts and creating surrogate models, especially in building and chemical LCA [15] [24]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Algorithm | A high-performing algorithm for classification and regression tasks in impact prediction, particularly effective with structured datasets [15]. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Data Feature | Quantitative representations of chemical structures that serve as input features for ML models predicting chemical impacts [3]. |

| VOSviewer | Software | A bibliometric mapping tool used to visualize networks of scientific literature, identifying key research clusters and trends [1] [25]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Algorithm/NLP Tool | Used to automate the extraction and processing of LCA data from textual sources like research articles and reports, addressing data scarcity [3] [12]. |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Algorithm | An optimization technique used in conjunction with ML surrogates to find design parameters that minimize life cycle environmental impacts [12]. |

| Digital Twins | Framework | A virtual replica of a physical system (e.g., a manufacturing process) that integrates real-time data with ML and LCA for dynamic sustainability assessment [26]. |

Future Research Directions and Challenges

Despite the promising trends, the field must overcome several challenges to mature. Data quality and availability remain the most significant hurdle, often requiring significant effort for curation and harmonization [3] [26] [12]. There is also a pressing need for standardized data workflows and benchmark datasets to ensure comparability and reproducibility across studies [23].

Future research is poised to focus on several key areas:

- Explainable AI (XAI): As models become more complex, developing methods to interpret and trust ML predictions is crucial for stakeholder acceptance and regulatory approval [1] [12].

- Prospective LCA: ML models will be increasingly used to forecast the environmental impacts of emerging technologies and novel chemicals before they are industrialized, guiding R&D toward more sustainable pathways [12].

- Hybrid Modeling: Integrating physics-informed machine learning (PIML), where ML models are constrained by known scientific principles, will enhance the physical realism and reliability of predictions [1].

- Social LCA Integration: Expanding beyond environmental impacts to incorporate social and ethical dimensions into AI-driven sustainability assessments represents a frontier for the field [26].

In conclusion, the bibliometric trends clearly illustrate a field in a phase of robust and dynamic growth. The integration of machine learning is steadily transforming life cycle assessment from a static, data-limited tool into a dynamic, predictive, and decision-critical technology. For researchers in chemical and drug development, this evolution opens new possibilities for rapidly designing greener molecules and more sustainable manufacturing processes, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable and circular economy.

A Practical Workflow: Implementing ML Models for Chemical Impact Prediction

In the realm of machine learning (ML) for chemical research, the representation of a molecule's structure is a foundational step. The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) string has emerged as one of the most widely used linear notations for representing molecular structures in two dimensions as text [27]. The process of converting these SMILES strings into numerical representations, known as molecular descriptors, is a critical form of feature engineering that enables the application of ML algorithms to predict chemical properties and behaviors. This technical guide details the methodologies for acquiring data from SMILES strings and engineering molecular descriptors, with specific application to life cycle assessment (LCA) for chemicals. LCA is a standardized methodology (ISO 14040/14044) for evaluating the environmental impacts of products and services throughout their life cycle, but it often faces challenges of data scarcity and high uncertainty, particularly regarding chemical toxicity and environmental fate [1]. ML techniques offer promising solutions to overcome these LCA challenges by automating data acquisition, harmonization, and predictive modeling [1].

From SMILES Strings to Molecular Descriptors

SMILES Strings as Molecular Representation

A SMILES string represents molecular graph information through a sequence of characters ('tokens') that denote atoms, bonds, rings, and branches [27]. A key characteristic of SMILES is its non-univocality; the same molecule can be represented by multiple valid SMILES strings depending on the starting atom and the graph traversal path chosen [27]. While this presents challenges for model training, it also enables valuable data augmentation strategies such as SMILES enumeration, wherein multiple representations of the same molecule are used during training to improve model robustness, particularly in low-data scenarios [27].

Molecular Descriptors: Definition and Types

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that capture specific chemical information about a molecule's structure and properties. They transform structural information encoded in SMILES strings into a quantitative format that ML algorithms can process. These descriptors can be broadly categorized into several types, each capturing different aspects of molecular structure and properties.

Table 1: Categories of Molecular Descriptors and Their Characteristics

| Descriptor Category | Description | Examples | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D/2D Descriptors | Derived from molecular connectivity, often called "fingerprints" or topological indices | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts, topological indices [28] | Low |

| 3D Descriptors | Based on molecular geometry and conformation | Dipole moment, principal moments of inertia, molecular surface area | Medium to High |

| Quantum Mechanical (QM) Descriptors | Derived from electronic structure calculations | HOMO/LUMO energies, ionization potential, electron affinity, HOMO-LUMO gap [28] | High |

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Workflows

SMILES Data Acquisition and Augmentation

The initial phase involves collecting and preprocessing SMILES strings to ensure data quality and diversity. For LCA applications, chemical databases such as ChEMBL are commonly used sources [27]. Data augmentation techniques can significantly enhance model performance, especially with limited training data. Beyond SMILES enumeration, novel augmentation strategies include:

- Token Deletion: Randomly removing tokens from SMILES strings (with options for enforcing validity or protecting specific tokens) [27]

- Atom Masking: Replacing specific atoms with placeholder tokens to improve learning of chemical semantics [27]

- Bioisosteric Substitution: Replacing functional groups with their bioisosteres to enhance model understanding of biologically relevant substitutions [27]

These augmentation strategies have demonstrated distinct advantages, with atom masking showing particular promise for learning physicochemical properties in low-data regimes, and deletion methods facilitating the creation of novel scaffolds [27].

Calculation of Molecular Descriptors

Once SMILES strings are acquired and preprocessed, molecular descriptors can be calculated using various software tools and libraries. The selection of appropriate descriptors depends on the specific LCA endpoint being modeled and the computational resources available.

Table 2: Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation

| Tool Name | Descriptor Types | Number of Descriptors | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL | 1D and 2D descriptors | 1,444 descriptors [28] | General cheminformatics |

| Mordred | 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors | 1,344 descriptors [28] | General cheminformatics |

| xTB | Quantum Mechanical (QM) descriptors | Limited set (HOMO/LUMO energies, ionization potential, electron affinity, etc.) [28] | Electronic properties for reactivity and toxicity |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from SMILES acquisition to model-ready features:

Application in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

Integration with LCA Phases

ML models built using molecular descriptors from SMILES strings can enhance all four phases of LCA [1]:

- Goal & Scope Definition: Natural language processing (NLP) techniques can assist in defining system boundaries and functional units based on chemical similarity.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): ML can predict missing inventory data for chemicals where experimental measurements are unavailable.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Surrogate and hybrid models can characterize environmental impacts, particularly for toxicity-related impact categories.

- Interpretation: ML models can identify significant molecular features driving environmental impacts, supporting decision-making.

Case Study: Toxicity Characterization for LCA

A recent study demonstrated the application of this approach for predicting characterization factors (CFs) for human toxicity and ecotoxicity aligned with the EU Environmental Footprint methodology [8]. The workflow involved:

- Data Collection: Gathering SMILES strings for chemicals with known characterization factors from the Environmental Footprint database.

- Descriptor Calculation: Computing molecular descriptors from SMILES strings.

- Model Training: Training multiple ML models (XGBoost, Gaussian Process regression, and Deep Neural Networks) to predict toxicity CFs.

- Cluster-Based Modeling: Implementing a clustering step to guide model selection for new compounds.

- Validation: Applying the model in a textile sector LCA case study, revealing that including predicted CFs increased total human toxicity scores by at least four orders of magnitude compared to using only existing CFs [8].

The XGBoost model achieved the best performance with R² values of 0.65 and 0.61 for ecotoxicity and human toxicity (seas water, continent), respectively [8].

Case Study: Predicting Sooting Propensity for Combustion LCA

Another application involves predicting Yield Sooting Index (YSI), a critical property for estimating combustion efficiency and pollution emissions of fuels [28]. Researchers compared ML models using different descriptor sets for 663 fuel molecules:

- Descriptor Computation: Calculating PaDEL, mordred, and QM descriptors from SMILES strings.

- Model Development: Training Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) regressor neural networks, Gradient Boosting (GB), and Random Forest (RF) models.

- Performance Comparison: The best-performing models varied by descriptor type: MLP for PaDEL, GB for mordred, and RF for QM descriptors [28].

- Result: All developed ML models achieved high accuracy (R² close to 1.0, mean absolute error <20) for YSI prediction [28].

Table 3: Performance of ML Models with Different Descriptors for YSI Prediction

| Descriptor Type | Best Model | Key Advantages | LCA Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL Descriptors | Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network | High accuracy with structural descriptors | Combustion emissions inventory |

| Mordred Descriptors | Gradient Boosting | Best overall performance with filtered descriptors [28] | General fuel property prediction |

| QM Descriptors | Random Forest | Provides insight into electronic properties [28] | Fundamental combustion behavior |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Descriptor Calculation

For reproducible calculation of molecular descriptors from SMILES strings:

- SMILES Validation: Ensure all SMILES strings are chemically valid using toolkits like RDKit.

- Standardization: Apply consistent normalization for tautomers, stereochemistry, and ionization states.

- Descriptor Calculation:

- For 1D/2D descriptors: Use PaDEL-Descriptor or Mordred with default parameters.

- For QM descriptors: Apply xTB with GFN2-xTB method for geometry optimization and property calculation.

- Descriptor Filtering: Remove constant or near-constant descriptors and highly correlated pairs (correlation >0.95).

- Data Splitting: Implement cluster-based or structure-based splitting to ensure representative training/validation/test sets.

Protocol for LCA-Specific Model Development

When developing ML models for LCA applications:

- Problem Formulation: Clearly define the LCA phase and impact category being addressed.

- Data Curation: Collect balanced datasets representing relevant chemical spaces for the LCA context.

- Model Selection: Evaluate multiple algorithm classes (tree-based, neural networks, kernel methods) with appropriate descriptor sets.

- Validation Strategy: Implement time-split or cluster-based validation to assess predictive performance on truly novel chemicals.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Employ methods like Gaussian Process regression or conformal prediction to estimate prediction uncertainty.

- Interpretation: Apply SHAP or similar methods to identify molecular features driving predictions, enhancing interpretability for LCA practitioners.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The computational tools and software libraries used in this field function as the essential "research reagents" for performing data acquisition and feature engineering from SMILES strings.

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for SMILES-Based Feature Engineering

| Tool Name | Function | Application in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | SMILES validation, normalization, and basic descriptor calculation | Open-source, comprehensive cheminformatics functionality |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Molecular descriptor calculator | Calculation of 1,444 1D/2D molecular descriptors [28] | Standalone software, high descriptor count |

| Mordred | Molecular descriptor calculator | Calculation of 1,344 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors [28] | Python API, integrates with RDKit |

| xTB | Semiempirical quantum chemistry | Calculation of QM descriptors (HOMO/LUMO energies, ionization potential, etc.) [28] | Fast computational speed, DFT-like accuracy |

| SHAP | Model interpretation | Explaining model predictions based on molecular descriptors | Model-agnostic, provides feature importance |

The acquisition of molecular descriptors from SMILES strings represents a powerful methodology for enabling machine learning in life cycle assessment of chemicals. By transforming structural information into numerical descriptors, researchers can develop predictive models for various chemical properties relevant to LCA, including toxicity characterization and environmental fate parameters. The integration of these ML approaches addresses critical data gaps in conventional LCA, particularly for chemicals without experimental measurements. As ML methodologies continue to advance alongside computational chemistry tools, the accuracy and applicability of descriptor-based approaches for LCA will further improve, supporting the development of more robust and comprehensive environmental assessments. Future research directions should focus on improving model interpretability, enhancing domain applicability across diverse chemical classes, and developing standardized protocols for ML-based chemical assessment in LCA frameworks.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is transforming how researchers quantify the environmental impacts of chemicals and materials. Faced with challenges of data scarcity, high uncertainty, and the static nature of conventional LCA, practitioners are increasingly turning to sophisticated algorithms to build more predictive, robust, and dynamic assessment models [1]. This paradigm shift enables the prediction of environmental impact factors for new chemicals early in the design phase, facilitating the development of inherently sustainable processes and supporting safer-by-design implementation [8] [29].

Within this context, selecting the appropriate machine learning algorithm becomes critical. No single algorithm universally outperforms others; the optimal choice depends on the specific problem, data characteristics, and desired outcomes. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparative analysis of three prominent ML algorithms—XGBoost, Neural Networks, and Gaussian Process Regression—specifically framed for LCA chemical prediction research. We examine their theoretical foundations, practical implementation, and performance across real-world case studies, equipping researchers and scientists with the knowledge needed to make informed algorithmic decisions.

Algorithm Fundamentals and Comparative Mechanics

Core Algorithmic Principles

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is an advanced implementation of gradient boosting machines that builds models sequentially. Each new tree corrects the errors of the previous ensemble, focusing on the most challenging observations. This additive model approach combines weak predictors (typically decision trees) into a single strong predictor through gradient descent optimization, with additional regularization terms to control model complexity and prevent overfitting [30].

Neural Networks (NNs), particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), are composed of interconnected layers of nodes (neurons) that process input data through weighted connections and nonlinear activation functions. These networks learn hierarchical representations of data, with deeper layers capturing more abstract features. The backpropagation algorithm adjusts connection weights to minimize the difference between predicted and actual outputs [30] [31].

Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a non-parametric, Bayesian approach to regression that defines a distribution over possible functions that fit the data. Rather than providing a single predictive function, GPR infrees a probability distribution of functions, characterized by a mean function and covariance kernel. This probabilistic framework naturally provides uncertainty estimates alongside predictions, a valuable feature for risk-aware applications [32] [33].

Technical Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of XGBoost, Neural Networks, and Gaussian Process Regression.

| Characteristic | XGBoost | Neural Networks | Gaussian Process Regression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Approach | Supervised, ensemble | Supervised, connectionist | Probabilistic, Bayesian |

| Model Type | Parametric | Parametric | Non-parametric |

| Primary Strength | Predictive accuracy, handling mixed data types | Modeling complex nonlinear relationships, feature learning | Uncertainty quantification, small data performance |

| Key Advantage in LCA | Handles missing data well, requires less preprocessing | Automatic feature engineering, excels with high-dimensional data | Natural confidence intervals, interpretable kernel structure |

| Computational Scaling | O(n×m) for n instances, m features | O(n×m×l) for l layers | O(n³) for training, O(n²) for prediction |

| Data Efficiency | Moderate | Requires large datasets | Excellent with small datasets |

| Output | Point prediction | Point prediction | Predictive distribution (mean & variance) |

Performance in Life Cycle Assessment and Chemical Research

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Multiple studies have quantitatively compared these algorithms across various domains relevant to LCA. In predicting the ultimate bearing capacity of shallow foundations—a complex geotechnical engineering problem—ensemble methods including GPR and XGBoost demonstrated superior performance with R² values above 0.988 and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) below 5.07%, significantly outperforming traditional methods (R²: 0.684-0.82, MAPE: >19.63%) [30].

In chemical toxicity characterization for LCA, researchers developed an ML workflow to predict characterization factors for human toxicity and ecotoxicity. When comparing XGBoost, GPR, and Neural Networks, XGBoost consistently performed best, achieving R² values of 0.65 and 0.61 for ecotoxicity and human toxicity in seas water and continent scenarios, respectively [8]. The study employed a clustering step to guide model selection for new compounds, highlighting the importance of context-specific algorithm selection.

A comprehensive civil engineering problem comparison that included these algorithms found that Neural Networks and Multi-Gene Genetic Programming yielded the most successful estimations across three different problem types. For managerial and experimental data, ANN showed particular strength, while different ML techniques demonstrated varying suitability depending on data characteristics and problem domain [34].

Table 2: Experimental performance comparison across application domains.

| Application Domain | Best Performing Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Toxicity CF Prediction [8] | XGBoost | R²: 0.65 (ecotoxicity), 0.61 (human toxicity) | Consistent outperformance; cluster-guided model selection recommended |

| Bearing Capacity Prediction [30] | Multiple (GPR, XGBoost, GBM, RF, CatBoost) | R² > 0.988, MAPE < 5.07% | Ensemble methods significantly outperformed traditional equations |

| Civil Engineering Problems [34] | ANN & MGGP | Varies by problem type | ANN superior for managerial and experimental data; problem type dictates optimal algorithm |

| Wastewater Treatment [33] | GPR | RPAE: 0.92689 (vs. 2.2947 for Polynomial Regression) | Superior modeling of complex factor interactions with uncertainty quantification |

| Eco-Friendly Mortar Prediction [35] | Stacking (Hybrid Ensemble) | High accuracy (specific metrics not provided) | Ensemble techniques, particularly stacking, showed superior predictive capability |

Experimental Protocols in LCA Chemical Prediction

The following experimental methodology represents a standardized approach for developing ML models for chemical prediction in LCA, synthesized from recent literature [8] [29] [1]:

1. Data Collection and Curation

- Compile chemical datasets from relevant databases (e.g., Environmental Footprint v3.0, USEtox)

- Extract molecular descriptors from SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) strings

- Include comprehensive life cycle inventory data where available

- Apply rigorous data quality assessment following ISO 14044 requirements [12]

2. Input Feature Selection

- Select input features based on scientific relevance and data availability

- Common features include physiochemical, molecular, and structural properties

- Apply feature importance analysis (e.g., SHAP, Relief Method) to identify most influential parameters [35]

- Address multicollinearity through correlation analysis

3. Model Training and Validation

- Split dataset into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 70/15/15)

- Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or k=10) to assess model robustness

- Apply hyperparameter tuning using grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization

- Evaluate performance using multiple metrics: R², RMSE, MAE, MAPE

4. Model Interpretation and Implementation

- Conduct SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to interpret feature influences [35]

- Validate model predictions against experimental data or established theoretical boundaries

- Deploy optimized models for predicting characterization factors of new chemicals

- Integrate uncertainty quantification, particularly critical for prospective LCAs

Workflow Integration and Decision Framework

End-to-End ML-LCA Integration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive integration of machine learning into the LCA workflow, highlighting the roles of different algorithms at various stages:

ML-LCA Integration Workflow Diagram

This workflow demonstrates how machine learning algorithms are integrated throughout the four phases of LCA, with particular importance in the impact assessment phase where predictive modeling occurs. The iterative nature of LCA is maintained through feedback loops informed by ML predictions.

Algorithm Selection Framework

Selecting the optimal algorithm depends on multiple factors specific to the LCA research context:

Choose XGBoost when:

- Working with tabular data with mixed data types

- Prioritizing predictive accuracy over uncertainty quantification

- Dealing with missing data in life cycle inventory datasets

- Requiring less computational resources for medium to large datasets

Choose Neural Networks when:

- Working with high-dimensional data (e.g., molecular descriptors, spectral data)

- Automatic feature engineering is beneficial

- Large, high-quality datasets are available (>10,000 samples)

- Modeling complex, non-linear relationships between chemical structure and environmental impact

Choose Gaussian Process Regression when:

- Uncertainty quantification is critical for decision-making

- Working with smaller datasets (<1,000 samples)

- Interpretability of covariance structure provides scientific insights

- Computational complexity is manageable for the dataset size

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Research Reagent Solutions for LCA-ML Research

Table 3: Essential materials and computational tools for LCA-ML research.

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Environmental Footprint Database | Provides standardized life cycle inventory data | EU Environmental Footprint v3.0 |