Machine Learning in PFAS Hazard Prediction: Cutting-Edge Models for Researchers and Drug Developers

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) models for predicting the hazards of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Machine Learning in PFAS Hazard Prediction: Cutting-Edge Models for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) models for predicting the hazards of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article delves into the foundational science of PFAS toxicity, details the methodologies and algorithms powering current prediction tools, addresses key challenges in model optimization and data scarcity, and critically evaluates model validation and performance. By synthesizing recent advances, this guide provides actionable insights for leveraging ML to accelerate the safety assessment and rational design of safer chemicals in biomedical research.

Understanding the PFAS Challenge: Why Machine Learning is Essential for Hazard Prediction

The study of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) presents a critical challenge for modern chemical hazard assessment. With thousands of structurally diverse compounds, traditional experimental toxicology is logistically and financially untenable for comprehensive risk characterization. This landscape provides the foundational data imperative for developing robust machine learning (ML) models. The core parameters—chemical diversity (features), environmental persistence (target property), and known health risks (target outcomes)—serve as the essential training and validation datasets for predictive computational toxicology.

Chemical Diversity: The Feature Space for ML

PFAS are defined by their fully fluorinated carbon chain (CnF2n+1–), which serves as a stable, non-polar lipophobic tail. The diversity arises from variations in the head group, chain length, branching, and the presence of ether linkages (as in GenX compounds). This structural variance directly influences physicochemical properties and biological interactions, forming the feature vectors for QSAR and ML models.

Table 1: Representative PFAS Classes and Structural Features

| PFAS Class | Example Compound | Core Structure (Rf) | Head Group | Key Structural Variant | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids (PFCAs) | PFOA (C8) | C7F15– | –COOH | Linear chain | Surfactant, industrial processing |

| Perfluoroalkyl Sulfonic Acids (PFSAs) | PFOS (C8) | C8F17– | –SO3H | Linear/branched | Fire-fighting foam, coatings |

| Perfluoroalkyl Ether Acids (PFEAs) | GenX (HFPO-DA) | C3F7–O–CF(CF3)– | –COOH | Ether oxygen (O) | Fluoropolymer manufacturing |

| Fluorotelomer Substances | 8:2 FTOH | C8F17–C2H4– | –OH | –C2H4– spacer | Precursor to PFCAs |

| Perfluorosulfonamides | FOSA | C8F17– | –SO2NH2 | Amide linkage | Photolithography, pesticides |

Environmental Persistence & Fate: Target Properties for ML

The defining characteristic of PFAS is the strength of the carbon-fluorine bond (~485 kJ/mol), conferring extreme thermal and chemical stability. This persistence, coupled with high water solubility for many ionic PFAS, leads to widespread environmental distribution and bioaccumulation potential, particularly for long-chain PFCAs/PFSAs.

Table 2: Quantitative Persistence and Exposure Metrics for Key PFAS

| Compound | Half-life in Human Serum (Years) | Half-life in Soil (Years) | Drinking Water MCL (U.S. EPA, ppt)* | Global Warming Potential (100-yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOS | 5.4 | 8.5 | 4 | 8,590 |

| PFOA | 3.8 | 6.5 | 4 | 7,550 |

| PFHxS | 8.5 | 4.2 | 10 (Proposed) | Data Limited |

| GenX | ~0.1 (Rapid renal clearance) | < 1 | Data Limited | Data Limited |

*MCL: Maximum Contaminant Level, parts per trillion.

Known Health Risks: Labeled Datasets for Model Training

Epidemiological and mechanistic studies have established robust adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) for legacy PFAS. These AOPs provide the "ground truth" labeled data for supervised ML models aiming to predict hazards for novel or data-poor PFAS.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: PPARα Activation Assay (Key In Vitro Screener)

- Objective: To quantify the agonist activity of a PFAS compound on the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha (PPARα), a primary molecular initiating event for metabolic disruption.

- Cell Line: Recombinant CV-1 monkey kidney fibroblast or HepG2 human hepatoma cells.

- Methodology:

- Transfection: Cells are co-transfected with (a) a plasmid expressing the GAL4-PPARα ligand-binding domain fusion protein, and (b) a reporter plasmid (pUAS(5x)-tk-luciferase) containing five GAL4 binding sites upstream of a minimal promoter and the firefly luciferase gene.

- Treatment: 24h post-transfection, cells are exposed to a dilution series of the test PFAS (e.g., 0.1 µM – 100 µM), a vehicle control (DMSO <0.1%), and a positive control (WY-14,643 at 50 µM). Incubate for 16-24h.

- Lysis & Measurement: Cells are lysed, and luciferase activity is measured using a luminometer following addition of D-luciferin substrate. Data is normalized to protein concentration (Bradford assay) or a co-transfected Renilla luciferase control for transfection efficiency.

- Analysis: Dose-response curves are generated. Efficacy is reported as a percentage of the maximal response induced by the positive control. Potency is reported as the EC50 (concentration causing 50% of maximal effect).

Primary Health Endpoints and Associated AOPs

Table 3: Established Human Health Risks and Mechanistic Links

| Health Endpoint | Strongest Epidemiological Association | Key Molecular Initiating Events (for ML Feature Linking) | Likely AOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyslipidemia | Elevated total & LDL cholesterol (PFOS, PFOA) | PPARα/γ activation, constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) activation | PPARα activation → Altered lipid metabolism → Increased serum cholesterol |

| Reduced Vaccine Response | Reduced antibody titers in children (PFOS, PFOA) | Inhibition of B-cell differentiation & proliferation, TLR signaling suppression | PPARα/γ activation in immune cells → Reduced plasmablast formation → Lower antibody production |

| Thyroid Disruption | Increased TSH, decreased T4 (PFOS, PFOA) | Competitive binding to transthyretin (TTR), upregulation of thyroid hormone catabolism | TTR displacement → Increased T4 clearance → Compensatory TSH rise |

| Kidney & Testicular Cancer | Occupational cohort evidence (PFOA) | Oxidative stress, epigenetic alterations, chronic inflammation | Sustained PPARα activation → Altered cell growth/apoptosis → Pre-neoplastic lesions |

Visualization of Key Pathways

Title: Core AOP for PFAS via PPAR Activation

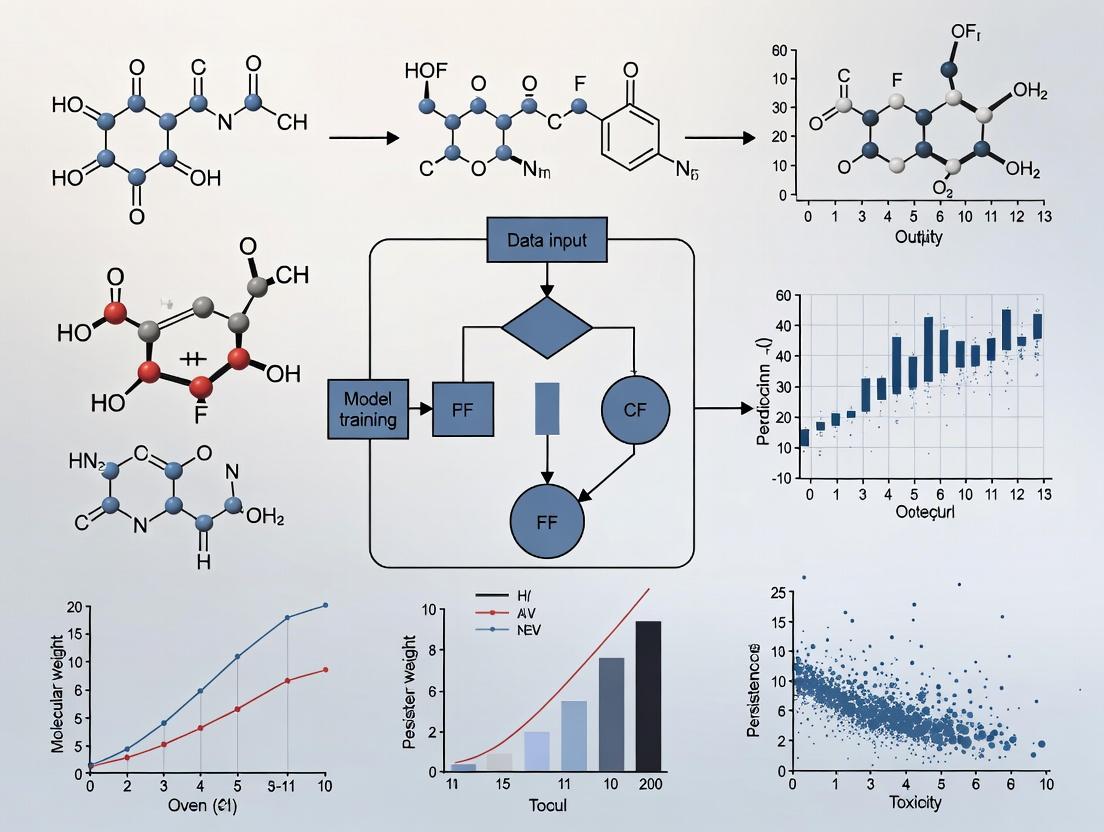

Title: ML Model Framework for PFAS Hazard Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for PFAS Toxicology Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Supplier/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Certified PFAS Analytical Standards | Quantification via LC-MS/MS; essential for generating accurate concentration-response data. | Wellington Laboratories (Native and Mass-Labeled Standards) |

| PPARα Reporter Assay Kit | Standardized system for measuring receptor activation, as per the protocol in Section 4.1. | Indigo Biosciences (PPARα Cell-Based Assay) |

| Human Transthyretin (TTR) Protein | For competitive binding assays (fluorescence displacement, SPR) to assess thyroid disruption potential. | Sigma-Aldrich (Recombinant Human TTR) |

| PFAS-Free Labware | Critical to avoid background contamination in bioassays and chemical analysis. | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Nunc PFAS-Free Plates) |

| C18 Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For isolating and concentrating PFAS from complex matrices (serum, cell media) prior to analysis. | Waters (Oasis WAX Cartridges for acidic PFAS) |

| In Silico Descriptor Software | Calculates molecular features (e.g., topological, electronic) for QSAR/ML model input. | Simulations Plus (ADMET Predictor), ChemAxon (Calculator Plugins) |

Limitations of Traditional Toxicological Testing for PFAS

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on developing machine learning (ML) hazard prediction models for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), examines the critical limitations of traditional toxicological testing paradigms. As the chemical space of PFAS expands beyond the scope of feasible animal testing, understanding these limitations is paramount for training accurate ML models and directing high-throughput experimental validation.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Testing for PFAS

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Hazard Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Diversity & Lack of Standards | >12,000 unique PFAS structures; certified analytical standards for <1% | Inaccurate exposure quantification and metabolite identification. |

| Toxicokinetic Properties | Tissue half-lives in years (e.g., PFOA: 2.3-3.8 years in humans); enterohepatic recirculation. | Short-term tests underestimate chronic burden; species extrapolation is flawed. |

| Mechanistic Complexity | Multi-modal receptor interactions (PPARα, CAR/PXR), mitochondrial dysfunction, epigenetic modulation. | Single-endpoint assays (e.g., cytotoxicity) miss key initiating molecular events. |

| Mixture Effects | Ubiquitous co-exposure; ~40% of environmental samples contain ≥3 PFAS. | Additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects are not captured by single-chemical tests. |

| Temporal & Dose-Response Dynamics | Non-monotonic dose-response curves observed for endocrine effects; effects manifest transgenerationally. | Standard linear, high-dose paradigms fail to predict low-dose or delayed outcomes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols Highlighting Limitations

1. Protocol: Standard 28-Day Repeated Dose Oral Toxicity Study (OECD 407) Applied to PFAS

- Objective: To identify target organ toxicity and establish a No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL).

- Test System: Rodents (typically Sprague-Dawley rats), n=5-10/sex/group.

- Dosing: Daily oral gavage of PFAS (e.g., PFOS, GenX) in vehicle for 28 days. Dose levels based on acute toxicity range-finding.

- Endpoints: Daily clinical observations, weekly body weight/food consumption. Terminal blood collection for clinical chemistry (liver enzymes, lipids). Histopathology of ~15 organs with emphasis on liver and kidney.

- Limitations Demonstrated: This protocol fails to capture the persistent bioaccumulation phase, potentially missing the true steady-state toxicity. Histopathology may show mild hepatocellular hypertrophy but will not identify the underlying proliferation of peroxisomes (PPARα activation) or epigenetic markers predictive of later-life dysfunction. It is blind to immune and endocrine endpoints not in the guideline.

2. Protocol: In Vitro High-Throughput Screening (HTS) - ToxCast/Tox21 Assays

- Objective: To profile bioactivity across numerous biochemical and cellular pathways.

- Test System: Human cell lines (e.g., HepG2, MCF-7) or engineered cell lines with specific reporter genes (e.g., PPARγ ligand binding, steroidogenic gene activation).

- Exposure: PFAS tested in concentration-response (typically nM to µM range) across a battery of assays (e.g., ~150 assays in ToxCast).

- Endpoint: Luminescence, fluorescence, or absorbance measured to quantify receptor activation, cytotoxicity, etc. AC50 (activity concentration at 50% of max) values are derived.

- Limitations Demonstrated: While broader, these assays often use high concentrations in serum-free media, ignoring the profound impact of protein binding (e.g., to serum albumin) on PFAS bioavailability in vivo. They also lack metabolic competence (e.g., missing conversion of PFAS precursors to terminal acids) and tissue-level communication (e.g., gut-liver axis).

Visualizations of Key Concepts

Diagram 1: PFAS Toxicity Pathways vs. Traditional Test Coverage

Diagram 2: Data Gaps in Traditional Testing for ML Model Training

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Assays for Next-Generation PFAS Toxicology

| Item / Solution | Function in PFAS Research | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Certified PFAS Analytical Standards & Mass-Labeled Isotopes | Quantification and identification of parent PFAS and transformation products in complex matrices. | Essential for generating reliable exposure and toxicokinetic data to feed into ML models. |

| Recombinant Human Protein Kits (e.g., PPARα/γ/δ LBD, CAR/PXR) | In vitro assessment of receptor binding affinity and activation potency. | Provides clean, mechanistic data on Molecular Initiating Events for ML feature engineering. |

| Metabolically Competent Cell Systems (e.g., HepaRG, primary hepatocytes) | Screening of PFAS precursors and investigation of hepatic metabolism. | Captures biotransformation critical for understanding the active toxicant and species differences. |

| Multiplexed Assay Panels (e.g., Cytokine/Chemokine, Phospho-Kinase) | Profiling of complex cellular responses beyond cytotoxicity. | Generates high-dimensional outcome data to map dose-response relationships and identify novel biomarkers. |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits (e.g., Global DNA Methylation, HDAC Activity) | Quantification of epigenetic modifications induced by PFAS. | Targets a key, often missed, mechanism of long-term toxicity and transgenerational effects. |

| Protein Binding Assay Kits (e.g., Serum Albumin Binding HTRF) | Measurement of PFAS binding to serum proteins. | Critical for adjusting in vitro bioactivity concentrations to reflect in vivo free fractions. |

The development of robust machine learning (ML) models for predicting PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) hazard is fundamentally constrained by the quality, comprehensiveness, and interoperability of underlying chemical data. This whitepaper details the core public data sources essential for constructing such models, framing their curation within the thesis that integrative, high-quality data aggregation is the critical prerequisite for accurate predictive toxicology of PFAS. We focus on databases providing chemical identifiers, physico-chemical properties, environmental fate, and in vitro/in vivo toxicity endpoints.

The following table summarizes the primary databases, their scopes, and key quantitative metrics relevant for ML feature engineering and model training.

Table 1: Core PFAS Data Sources for ML Research

| Data Source | Provider | Primary Content | PFAS-Specific Records (Est.) | Key Data Types for ML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | Aggregated data for ~900k chemicals. | ~15,000+ (in "PFASSTRUCT" list) | DSSTox IDs, structures, properties, bioactivity (ToxCast), exposure, linked identifiers. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development | Tool for chemical grouping and read-across. | Curated PFAS categories (e.g., 47 categories in ver. 4.5) | Experimental and predicted properties, toxicity databases, metabolic pathways, profiling. |

| PubChem | National Center for Biotechnology Information | Massive repository of chemical information. | ~200,000+ (via name/substructure search) | CID, bioassays (incl. Tox21/ToxCast), literature, vendor data. |

| NORMAN Suspect List Exchange | NORMAN Network | Aggregated suspect and target lists. | ~10,000+ unique PFAS structures across lists | Suspect PFAS structures, molecular formulas, masses, use categories. |

| ACToR (Aggregated Computational Toxicology Resource) | U.S. EPA (Archive) | Historical aggregation of toxicity data. | Subset of CompTox data. | Curated in vivo toxicity data from legacy sources. |

Detailed Curation Methodology and Experimental Protocols

3.1. Protocol: Building a Harmonized PFAS Training Set from CompTox and OECD Objective: Create a ML-ready dataset linking chemical structures to in vitro bioactivity and in vivo toxicity endpoints.

PFAS Identifier Retrieval:

- Source the current "PFASSTRUCT" list (DSSTox Identifier, SMILES, InChIKey) from the EPA CompTox Dashboard.

- Retrieve corresponding PFAS category assignments from the OECD QSAR Toolbox's "PFASs per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances" grouping scheme.

Property Data Aggregation:

- For each DSSTox ID, programmatically query the CompTox Dashboard APIs to retrieve predicted and experimental properties (e.g., LogP, water solubility, molecular weight, persistence/bioaccumulation scores).

- Export data in standardized formats (CSV, JSON).

Toxicity Endpoint Integration:

- In Vitro Bioactivity: Link DSSTox IDs to high-throughput screening (HTS) data from the ToxCast/Tox21 programs. Extract AC50 (concentration at 50% activity) values and target assay information (e.g., nuclear receptor signaling, stress response).

- In Vivo Toxicity: Extract curated points of departure (PODs) such as chronic NOAEL/LOAEL values from the ACToR/CompTox database where available.

Data Curation and Cleaning:

- Deduplication: Resolve entries using InChIKey as the unique identifier.

- Missing Data Handling: Flag missing values; consider imputation strategies (e.g., QSAR prediction) only for training features, not for target toxicity endpoints.

- Standardization: Normalize toxicity values to consistent units (e.g., µM for in vitro, mg/kg/day for in vivo). Apply quality flags from source databases.

3.2. Protocol: Utilizing the OECD QSAR Toolbox for Read-Across and Profiling Objective: Use the Toolbox to fill data gaps and inform chemical grouping for ML.

- Chemical Input: Import the list of target PFAS structures (SMILES) into the Toolbox.

- Profiling: Execute the "Profiling" module using all relevant databases (e.g., EPA PFAS Hazard, ECOTOX, HPVIS). This identifies analogous chemicals with experimental data.

- Category Formation: Apply the "PFAS... chemical category" predefined or automated grouping to build read-across hypotheses.

- Data Gap Filling: For a target PFAS with missing property/toxicity data, the Toolbox retrieves data from source analogs within its category, applying adjustment rules (if any). This output can serve as supplementary training data, with clear provenance tagging.

Visualization of Data Curation and Model Integration Workflow

Diagram 1: PFAS ML Data Curation & Model Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for PFAS Database Curation and Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function in PFAS ML Research |

|---|---|

| CompTox Dashboard API | Programmatic access to chemical properties, bioactivity data, and identifier mapping for large-scale dataset construction. |

| RDKit (Python Cheminformatics) | Computes molecular descriptors and fingerprints from SMILES strings; standardizes structures for ML feature generation. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox Software | Performs critical read-across and chemical category formation to infer missing data and support mechanistic grouping. |

| CDK (Chemistry Development Kit) | Open-source alternative to RDKit for descriptor calculation and chemical informatics operations in Java environments. |

| KNIME or Pipeline Pilot | Visual workflow platforms for building reproducible data curation, preprocessing, and modeling pipelines. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor Software | Standalone tool for calculating a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors for QSAR/ML. |

| PubChem PyPUG | Python interface to retrieve bioassay results and compound information from PubChem. |

| MongoDB / PostgreSQL | Database systems for storing and querying complex, hierarchical chemical-toxicity data relationships. |

Foundational QSAR in Toxicity Prediction

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental paradigm in computational toxicology and drug discovery. It operates on the principle that a quantitative relationship exists between a molecule's physicochemical descriptors and its biological activity or property. For PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) research, traditional QSAR has been instrumental in initial hazard screening.

Core QSAR Methodology

The standard QSAR workflow involves:

- Data Curation: Compiling a consistent set of chemical structures and associated experimental toxicological endpoints (e.g., LC50, LogP, binding affinity).

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating numerical representations of molecular structure using software like PaDEL, RDKit, or Dragon. Descriptors include constitutional (molecular weight, atom count), topological (connectivity indices), electrostatic (partial charges), and quantum chemical.

- Feature Selection & Model Building: Applying statistical methods (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS)) to correlate descriptors with the activity.

- Validation: Assessing model performance using OECD principles—internal cross-validation and external test set validation.

Table 1: Classic QSAR Descriptors for PFAS Toxicity Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Specific Examples | Relevance to PFAS |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic | LogP (Octanol-water partition coefficient) | Predicts bioaccumulation potential of long-chain PFAS. |

| Electronic | Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) Energy | Indicates susceptibility to oxidation; relevant for PFAS degradation studies. |

| Steric | Molecular Volume, Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | Influences interaction with protein targets like PPARγ. |

| Constitutional | Number of Fluorine Atoms, CF2/CF3 Group Count | Directly captures PFAS-specific chemistry. |

Experimental Protocol: OECD-Compliant QSAR Model Development

- Objective: Develop a validated QSAR model to predict the binding affinity of PFAS analogues to the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ).

- Materials:

- Chemical Structures: SMILES notations for 150 diverse PFAS compounds.

- Experimental Data: Half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values from standardized in vitro PPARγ transactivation assays.

- Software: PaDEL-Descriptor for calculation, Python/scikit-learn or SIMCA for modeling.

- Procedure:

- Divide the dataset into a training set (80%) and an external test set (20%) using a rational splitting method (e.g., Kennard-Stone).

- Calculate 2D and 3D molecular descriptors for all compounds.

- Preprocess data: Remove constant/near-constant descriptors, handle missing values, and scale the remaining descriptors.

- Perform feature selection on the training set using Genetic Algorithm combined with Partial Least Squares (GA-PLS) to identify the 5-10 most relevant descriptors.

- Train a PLS regression model using the selected descriptors and training set activity data.

- Internal Validation: Perform 5-fold cross-validation on the training set; report Q² (cross-validated R²), RMSEcv.

- External Validation: Apply the final model to the held-out test set; report R²ext, RMSEext, and slope of the experimental vs. predicted plot.

- Define the Applicability Domain (AD) using leverage and residual methods.

The Shift to Advanced Machine Learning for PFAS

The complexity, high-dimensionality, and "big data" nature of modern chemical and toxicological datasets have driven the shift from classical QSAR to advanced Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL). For PFAS, this is critical due to the vast chemical space, limited experimental data for many congeners, and complex, multimodal mechanisms of toxicity.

Limitations of Classical QSAR Addressed by ML

- Non-Linear Relationships: ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Neural Networks) inherently capture non-linear descriptor-activity relationships.

- High-Dimensional Data: ML techniques are robust against multicollinearity and can handle thousands of descriptors or even raw molecular representations (e.g., graphs, fingerprints).

- Data Integration: ML frameworks can integrate diverse data types—chemical structures, in vitro assay results, omics data, and physical properties—into a single predictive model.

Table 2: Comparison of Modeling Approaches for PFAS Hazard Prediction

| Aspect | Classical QSAR (e.g., PLS) | Advanced Machine Learning (e.g., GNN, XGBoost) |

|---|---|---|

| Model Transparency | High (Interpretable coefficients) | Moderate to Low ("Black-box", requires SHAP/ LIME) |

| Handling Non-linearity | Poor | Excellent |

| Descriptor Dependency | High (Requires curated descriptors) | Low (Can learn from graphs or fingerprints) |

| Data Efficiency | Requires relatively less data | Requires larger datasets for robust training |

| Typical Performance | Good for congeneric series | Superior for diverse, complex datasets |

| PFAS Application Example | Predicting LogP for C4-C12 PFCAs | Predicting toxicity of novel PFAS structures from molecular graph. |

Advanced ML Protocol: Graph Neural Network for PFAS Toxicity

- Objective: Train a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to classify PFAS compounds as "high" or "low" hazard based on multiple toxicological endpoints.

- Materials:

- Data Source: EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard PFAS dataset, merged with in vivo toxicity data from ToxValDB.

- Hardware/Software: Python with PyTorch Geometric, DGL libraries; GPU acceleration recommended.

- Procedure:

- Graph Representation: Convert each PFAS SMILES string into a molecular graph. Nodes represent atoms (featurized with atomic number, degree, hybridization). Edges represent bonds (featurized with bond type, conjugation).

- Model Architecture: Implement a Message-Passing Neural Network (MPNN).

- Message Passing Layers (3-5): Aggregate information from neighboring atoms. Update node embeddings using a learned function (e.g., Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)).

- Global Pooling: Use a "Set2Set" or attention-based pooling layer to generate a fixed-size molecular embedding from the updated node embeddings.

- Readout/Classification Layer: Pass the pooled graph embedding through fully connected layers with dropout for final binary classification.

- Training: Use binary cross-entropy loss with an Adam optimizer. Employ a validation set for early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Interpretation: Apply graph-based explainability techniques like GNNExplainer to identify substructures (e.g., CF2 chain length, sulfonate head group) driving the toxicity prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Developing PFAS ML Hazard Models

| Item/Category | Function & Relevance | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Curated PFAS Datasets | Provides standardized, quality-controlled structural and toxicological data for model training and benchmarking. | EPA CompTox PFAS Dashboard: Structures, properties, and experimental data. OECD QSAR Toolbox: Contains PFAS datasets and profiling tools. |

| Molecular Descriptor & Fingerprint Software | Generates numerical features from chemical structures for traditional ML models. | RDKit (Open Source): Calculates descriptors, Morgan fingerprints. PaDEL-Descriptor: Computes 1D-2D descriptors. Dragon: Commercial software for >5000 descriptors. |

| Deep Learning for Chemistry Libraries | Enables building of advanced neural network models directly on molecular graphs or sequences. | PyTorch Geometric: Implements GNNs. DeepChem: End-to-end toolkit for cheminformatics ML. MoleculeNet: Benchmark datasets. |

| Model Explainability (XAI) Tools | Interprets "black-box" ML models to identify structural alerts and ensure regulatory acceptance. | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Assigns feature importance. GNNExplainer: Explains predictions of GNNs via relevant subgraphs. LIME: Creates local interpretable model approximations. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Accelerates the training of complex models and hyperparameter optimization on large chemical datasets. | Cloud GPUs (AWS, GCP): For deep learning. Slurm Clusters: For large-scale parallelized QSAR/ML runs. |

| Toxicity Pathway Assay Kits | Generates high-quality in vitro data for model training and validation on specific mechanisms (e.g., nuclear receptor binding). | PPARγ Reporter Assay Kits (e.g., Indigo Biosciences): Measures PFAS binding and activation. Cell Viability/Proliferation Assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo): For cytotoxicity endpoint data. |

Key Biological Endpoints and Molecular Initiating Events for PFAS

Within the broader research thesis on developing machine learning (ML) hazard prediction models for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), defining precise molecular initiating events (MIEs) and downstream key biological endpoints is paramount. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core components, serving as the foundational biological framework for feature engineering and model validation in computational toxicology.

Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs)

MIEs are the initial, measurable interactions between a PFAS molecule and a biological target that start a toxicological pathway. For PFAS, MIEs are dominated by high-affinity interactions with specific proteins.

Primary Protein Targets

PFAS, particularly long-chain varieties, exhibit strong binding affinities as a core MIE.

Table 1: Key Protein Targets and Binding Affinities for Select PFAS

| PFAS Compound | Primary Target Protein | Reported Kd / IC50 (nM) | Experimental System | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid) | Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Kd: 90 - 200 nM | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Zhang et al., 2022 |

| PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonate) | Liver Fatty Acid Binding Protein (L-FABP) | IC50: ~5 nM (displacement) | Fluorescent Displacement Assay | Sheng et al., 2021 |

| GenX (HFPO-DA) | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha (PPARα) | EC50: ~10,000 nM (transactivation) | In vitro Luciferase Reporter Assay | Evans et al., 2023 |

| PFNA (Perfluorononanoic acid) | Thyroid Hormone Transport Protein (Transthyretin) | Kd: 1.2 nM | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Li et al., 2023 |

Experimental Protocol: Fluorescent Displacement Assay for L-FABP Binding

Objective: Quantify the binding potency of PFAS by measuring displacement of a fluorescent fatty acid analog from L-FABP.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare assay buffer (10 mM phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Dilute recombinant human L-FABP to 1 µM in buffer. Prepare serial dilutions of PFAS test compounds (e.g., PFOS, PFOA) in DMSO (final DMSO <1%). Prepare 1,8-ANS (8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate) stock at 1 mM.

- Complex Formation: In a black 384-well plate, mix L-FABP (final 0.5 µM) with 1,8-ANS (final 10 µM) in assay buffer. Incubate 10 min at 25°C protected from light.

- Compound Addition: Add PFAS compounds across a concentration range (e.g., 1 nM – 100 µM). Include wells with buffer only (negative control) and a known high-affinity unlabeled fatty acid (e.g., oleic acid) as a positive control for maximal displacement.

- Measurement: Read fluorescence (excitation: 360 nm, emission: 460 nm) on a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate % displacement relative to vehicle (0%) and positive control (100%). Fit dose-response data to a four-parameter logistic model to determine IC50 values.

Key Biological Endpoints

MIEs trigger cascades of cellular events leading to adverse outcomes. These endpoints are critical labels for ML model training.

Hepatotoxicity & Metabolic Disruption

A primary endpoint driven by PPAR activation and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Table 2: Hepatotoxicity Endpoints and Quantitative Findings

| Endpoint Category | Specific Measurable Endpoint | Typical In Vivo Finding (Rodent) | Relevant In Vitro Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | Hepatocyte proliferation index | 3-5 fold increase in BrdU incorporation after 7d PFOS exposure | Ki-67 staining; BrdU ELISA |

| Lipid Metabolism | Serum triglycerides | Decrease of 40-60% vs. control | N/A (in vivo endpoint) |

| Lipid Accumulation | Hepatic steatosis score (histopathology) | Significant increase at ≥ 1 mg/kg/day PFOA | Oil Red O staining quantification |

| Oxidative Stress | Hepatic glutathione (GSH) depletion | GSH decreased by 30-50% | Cellular GSH-Glo Assay |

| Mitochondrial Function | Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) | Basal OCR reduced by 25% in HepG2 cells | Seahorse XF Analyzer assay |

Immunotoxicity

A high-priority endpoint for short-chain and emerging PFAS.

Table 3: Immunotoxicity Endpoints

| Immune Parameter | Assay Method | Example PFAS Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Suppression | T-cell Dependent Antibody Response (TDAR) | >50% reduction in IgM plaque-forming cells (PFOS) |

| Inflammatory Cytokine Release | Multiplex ELISA (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) | Dose-dependent increase in LPS-stimulated macrophages |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cell Activity | YAC-1 lymphoma cell cytotoxicity assay | Significant reduction in lytic units |

| Basal Immunoglobulin Levels | Serum IgM/IgG quantification | Decreased IgM in developmental exposures |

Signaling Pathways: From MIE to Endpoint

Canonical and non-canonical pathways activated by PFAS.

PPARα-Mediated Hepatotoxicity Pathway

Diagram Title: PPARα Activation Pathway Leading to Hepatotoxicity

Experimental Workflow for Integrated Testing

Diagram Title: Tiered Experimental Workflow for PFAS Hazard Data Generation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Assays for PFAS MIE/Endpoint Research

| Category | Item / Kit Name | Vendor Examples | Primary Function in PFAS Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding Assays | HTRF PPARα Coactivator Assay | Revvity (Cisbio) | Measures recruitment of coactivator peptides to PPARα-LBD upon PFAS binding. |

| Fatty Acid Binding Protein (FABP) Fluorescent Probe Kits | Cayman Chemical | Contains fluorescent fatty acid analogs for displacement assays to determine PFAS binding affinity. | |

| Cell-Based Reporter Assays | PPAR Response Element (PPRE) Luciferase Reporter Plasmids | Addgene, commercial kits | Stably or transiently transfected cell lines used to measure PPAR pathway activation. |

| Nuclear Receptor Panel Reporter Assay Services | Indigo Biosciences | High-throughput screening of PFAS against PPARs, ER, AR, etc., in a standardized format. | |

| Phenotypic Screening | HepG2 or Primary Hepatocyte Steatosis Assay Kits | Cell Biolabs, Abcam | Quantify lipid accumulation (e.g., via Oil Red O or Nile Red) as a key hepatotoxicity endpoint. |

| Seahorse XFp Analyzer Kits | Agilent Technologies | Profile mitochondrial stress and glycolytic function in cells exposed to PFAS. | |

| Immunotoxicity | LEGENDplex Multi-Analyte Flow Assay Kits | BioLegend | Quantify a panel of secreted cytokines from immune cells (e.g., macrophages) treated with PFAS. |

| TDAR Assay Kits (for in vivo) | Thermo Fisher, ELISA-based | Measure antigen-specific IgM/IgG responses in rodent PFAS exposure studies. | |

| Omics Analysis | TempO-Seq Targeted Transcriptomics | BioClio | Provides a high-content, HTS-compatible gene expression profile for pathway analysis. |

| Metabolon Discovery HD4 Platform | Metabolon | Global untargeted metabolomics to identify metabolic disruptions from PFAS exposure. |

Building the Models: Algorithms, Descriptors, and Practical Implementation

Within the broader thesis on developing robust machine learning (ML) hazard prediction models for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), the selection and application of core algorithms are paramount. PFAS, a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals, present a unique challenge due to their environmental persistence, complex structure-activity relationships, and data sparsity. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of four pivotal ML paradigms—Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Neural Networks, and Graph-Based Models—detailing their theoretical foundations, adaptation for PFAS research, experimental protocols, and comparative performance. The objective is to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement and advance predictive toxicology models for PFAS.

Algorithmic Foundations & PFAS-Specific Adaptations

Random Forest (RF)

An ensemble method constructing multiple decision trees during training. For PFAS, RF handles high-dimensional molecular descriptor data (e.g., from QSAR modeling) and identifies critical features like chain length or functional groups influencing persistence, bioaccumulation, or toxicity (PBT). Its inherent feature importance metrics (Mean Decrease in Impurity/Gini) are crucial for mechanistic interpretation.

Support Vector Machines (SVM)

SVM finds the optimal hyperplane to separate data classes in a high-dimensional space. In PFAS classification (e.g., toxic vs. non-toxic), the kernel trick (RBF, polynomial) allows separation of non-linearly related structural descriptors. It is effective in scenarios with a clear margin of separation in the feature space, even with moderate sample sizes.

Neural Networks (NN) & Deep Learning

Multi-layered architectures capable of learning complex, non-linear representations from raw or processed input data. For PFAS, deep NNs can directly process high-throughput screening data or intricate molecular fingerprints. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), a specialized subclass, are discussed separately in Section 2.4.

Graph-Based Models (Including GNNs)

PFAS molecules are inherently graph-structured (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges). Graph-Based Models, particularly GNNs, directly operate on this structure, learning embeddings that encode molecular topology and features. This is superior to traditional fixed-length fingerprints for capturing subtle structural nuances across diverse PFAS.

Recent benchmarking studies highlight the performance of these algorithms on key PFAS prediction tasks. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from current literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML Algorithms on PFAS Hazard Prediction Tasks

| Algorithm Category | Specific Model Tested | Prediction Task (e.g.,) | Dataset Size (# of PFAS) | Key Metric & Performance | Key Advantage for PFAS | Primary Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble (Tree-Based) | Random Forest | Bioconcentration Factor (BCF) Classification | ~300 | AUC-ROC: 0.89 | Robust to noise, provides feature importance | Zango et al., 2023 |

| Kernel Method | Support Vector Machine (RBF Kernel) | Thyroid Hormone Disruption Potential | ~150 | Accuracy: 82.5% | Effective in high-dimensional spaces with limited samples | Pan et al., 2024 |

| Neural Network | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | PFAS Toxicity Value (LC50) Regression | ~500 | RMSE: 0.38 log units | Models complex non-linear dose-response relationships | US EPA CompTox Dashboard Studies |

| Graph-Based Model | Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPARγ) Binding Affinity | ~400 | R²: 0.72 | Learns directly from molecular structure without predefined fingerprints | Stevens et al., 2024 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for a PFAS ML Study

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for developing a PFAS classification model using Random Forest, adaptable to other algorithms.

Protocol: Developing a Random Forest Classifier for PFAS Bioaccumulation Potential

4.1. Data Curation & Featurization

- Source: Gather PFAS structures and experimental BCF data from public databases (e.g., EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, PubChem).

- Inclusion Criteria: Select only perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) with carbon chain length C4-C12 to ensure homogeneity.

- Featurization: Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, geometrical) using RDKit or PaDEL-Descriptor software. Examples include molecular weight, octanol-water partition coefficient (logP), topological surface area (TPSA), and number of rotatable bonds.

- Labeling: Binarize BCF values (e.g., BCF > 1000 L/kg = "Bioaccumulative", BCF ≤ 1000 = "Non-bioaccumulative") based on regulatory thresholds.

4.2. Model Training & Validation

- Splitting: Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and hold-out test (15%) sets using stratified splitting to maintain class balance.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use the validation set and grid/random search to optimize RF parameters:

n_estimators(100-1000),max_depth(5-30),min_samples_split(2-10). - Training: Train the RF model on the training set using the optimized hyperparameters.

- Evaluation Metrics: Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC on the hold-out test set.

4.3. Interpretation & Analysis

- Feature Importance: Extract and rank the top 20 molecular descriptors by Gini importance.

- SHAP Analysis: Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations to interpret individual predictions and understand global descriptor contributions.

Diagram Title: PFAS ML Model Development and Interpretation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools & Resources for PFAS ML Research

| Item/Category | Function in PFAS ML Research | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | Source of PFAS structures, properties, and experimental hazard data. | EPA CompTox Dashboard, PubChem, NORMAN SusDat |

| Featurization Software | Computes numerical representations (descriptors/fingerprints) from molecular structures. | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, Mordred |

| ML Frameworks | Libraries for implementing, training, and evaluating machine learning models. | Scikit-learn (RF, SVM), TensorFlow/PyTorch (Neural Nets), DGL/PyG (GNNs) |

| Interpretation Libraries | Provides post-hoc model explainability and feature contribution analysis. | SHAP, Lime, eli5 |

| Curated PFAS Lists | Defines the chemical space of interest and ensures relevant model applicability. | OECD PFAS List, US EPA PFAS Master List |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides computational power for training complex models (e.g., deep NNs, GNNs) on large datasets. | Cloud platforms (AWS, GCP), institutional HPC clusters |

Diagram Title: Neural Network Architecture for PFAS Hazard Prediction

Signaling Pathway Integration & Mechanistic Modeling

A significant advancement in PFAS ML is integrating algorithm predictions with adverse outcome pathways (AOPs). For instance, a model predicting PPARγ binding can be linked to a downstream AOP for hepatosteatosis.

Diagram Title: Integrating ML Predictions with a PFAS Adverse Outcome Pathway

The development of predictive models for PFAS hazards is a critical component of the overarching thesis on computational toxicology. Random Forest offers a robust, interpretable baseline. SVM provides strong performance in complex feature spaces, while Neural Networks excel at capturing deep, non-linear relationships. Graph-Based Models represent the frontier, leveraging the inherent graph structure of molecules for potentially superior predictive power. The integration of these models with mechanistic biological pathways, as outlined, promises not only more accurate hazard classification but also enhanced scientific understanding, ultimately supporting faster and safer chemical and pharmaceutical development.

Within the broader thesis on developing robust machine learning (ML) models for PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) hazard prediction, feature engineering stands as the critical, foundational step. The predictive power of any model is constrained by the quality and relevance of the input features. For PFAS—a vast class of thousands of synthetic compounds characterized by strong carbon-fluorine bonds—the translation of molecular structure into numerical or bit-vector representations (descriptors and fingerprints) is non-trivial and decisive. This guide details the technical methodologies for generating, selecting, and interpreting these molecular features, providing the essential data layer for subsequent ML-driven hazard classification and regression tasks.

Molecular Descriptor Calculation for PFAS

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that quantify specific physicochemical, topological, or electronic properties of a molecule. For PFAS, careful selection is required to capture properties relevant to environmental persistence, bioaccumulation, and protein interaction.

Key Descriptor Categories & Protocols

Protocol 2.1.1: Geometry Optimization and Charge Calculation

- Objective: Generate a stable 3D conformation and calculate partial atomic charges as a prerequisite for 3D descriptor calculation.

- Software: RDKit (Open-Source), Open Babel, or Gaussian (commercial).

- Steps:

- Input SMILES string for the PFAS compound (e.g.,

FC(F)(C(F)(F)F)C(F)(F)OC(F)(F)Ffor HFPO-DA). - Generate an initial 3D conformation using distance geometry (RDKit's

EmbedMolecule). - Perform a molecular mechanics (MMFF94 or UFF) geometry optimization to minimize strain energy.

- Calculate partial atomic charges using the Gasteiger-Marsili method (RDKit) or more advanced DFT methods (Gaussian:

B3LYP/6-31G*) for higher accuracy. - Output: Optimized 3D molecular structure file (.mol or .sdf) and charge array.

- Input SMILES string for the PFAS compound (e.g.,

Protocol 2.1.2: Descriptor Computation via RDKit/Padel

- Objective: Compute a comprehensive set of 1D-3D molecular descriptors.

- Software: RDKit Python library or PaDEL-Descriptor software.

- Steps:

- Load the optimized molecular object.

- Use the

Descriptorsmodule in RDKit (CalcMolDescriptors) or run PaDEL-Descriptor in command line mode. - Specify descriptor types. The software automatically computes ~200-1800 descriptors.

- Output: A vector of descriptor names and their values for each PFAS molecule.

Quantitative Descriptor Data for Representative PFAS

Table 1: Calculated Molecular Descriptors for Select PFAS Compounds

| PFAS Common Name | SMILES | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Topological Polar Surface Area (Ų) | LogP (Predicted) | Number of Fluorine Atoms | Labile Bond Count (C-O, C-N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid) | FC(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(O)=O |

414.07 | 37.30 | 4.10 ± 0.50 | 15 | 2 |

| PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) | FC(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(F)(F)S(O)(=O)=O |

500.13 | 74.76 | 2.57 ± 1.00 | 17 | 3 |

| GenX (HFPO-DA) | FC(F)(C(F)(F)F)C(F)(F)OC(F)(F)C(F)(F)C(O)=O |

330.05 | 52.60 | 1.80 ± 0.70 | 11 | 4 |

Molecular Fingerprint Generation for PFAS

Fingerprints are binary bit vectors representing the presence or absence of specific structural substructures or patterns. They are highly effective for similarity searching and ML models.

Fingerprint Types & Generation Protocols

Protocol 3.1.1: Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs)

- Objective: Generate a circular, topology-based fingerprint that captures functional groups and molecular environments.

- Software: RDKit (

rdMolDescriptors.GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVect). - Steps:

- Load the molecular object from SMILES.

- Set parameters:

radius(typically 2 for ECFP4),nBits(typically 1024 or 2048). - For each atom, an initial identifier (based on atom type, degree, etc.) is assigned. In each iteration (

radius), identifiers are updated by hashing the identifiers of neighboring atoms. - The final set of atom identifiers is folded into a fixed-length bit vector via hashing.

- Output: A bit vector of length

nBits.

Protocol 3.1.2: RDKit Topological Fingerprint

- Objective: Generate a path-based fingerprint enumerating linear fragments of specified lengths.

- Software: RDKit (

rdMolDescriptors.GetHashedTopologicalTorsionFingerprint). - Steps:

- Load the molecular object.

- Enumerate all possible linear paths (e.g., topological torsions of 4 atoms) within the molecule.

- Hash each path to a set of bits in the fixed-length vector.

- Output: A bit vector, useful for capturing linear perfluoroalkyl chains.

Fingerprint Analysis for Structural Similarity

Table 2: Tanimoto Similarity Matrix Based on ECFP4 (1024 bits)

| Compound Pair | Tanimoto Similarity (ECFP4) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| PFOA vs. PFOS | 0.45 - 0.55 | Moderate similarity due to shared perfluoroalkyl chain but different headgroups (-COOH vs. -SO3H). |

| PFOA vs. GenX | 0.25 - 0.35 | Low similarity; GenX has an ether linkage and a branched chain, differing significantly from linear PFOA. |

| PFOS vs. PFHxS | 0.70 - 0.80 | High similarity; differ only in perfluoroalkyl chain length (C8 vs. C6). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for PFAS Feature Engineering

| Item Name | Provider/Software | Function in PFAS Feature Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Core Python library for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation (1D/2D), and fingerprint generation (ECFP, topological). |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Yap, C.W. (2011) | Standalone software for batch calculation of >1800 molecular descriptors and 12 fingerprint types from structure files. |

| Open Babel | Open-Source Project | Tool for file format conversion, basic 3D optimization, and descriptor calculation to supplement RDKit. |

| Gaussian 16 | Gaussian, Inc. | Commercial quantum chemistry software for high-accuracy DFT calculations to derive electronic descriptors (HOMO/LUMO, dipole moment) for key PFAS. |

| PubChemPFAS Collection | NIH/NLM | Curated database of PFAS structures (SMILES) used as a primary source for SMILES strings and related identifiers. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | OECD | Provides chemical category workflows and databases to help identify relevant structural alerts and descriptors for PFAS grouping. |

| Mordred Descriptor Calculator | Open-Source Project | Python-based descriptor calculator capable of generating ~1800 1D-3D descriptors, often used alongside RDKit. |

| CDK (Chemistry Development Kit) | Open-Source Project | Java-based library offering a wide array of cheminformatics algorithms, usable for descriptor calculation in pipeline workflows. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

PFAS Feature Engineering Pipeline

Feature to Hazard Logical Pathway

The development of robust machine learning (ML) models for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) hazard prediction is critical for environmental science, drug development, and regulatory toxicology. This pipeline is framed within a broader thesis aiming to replace costly, time-consuming in vivo assays with in silico models that can predict toxicity endpoints, bioaccumulation potential, and environmental persistence of novel PFAS compounds. The pipeline's reproducibility and rigor directly impact the reliability of predictions used for risk assessment and molecular design.

The Pipeline: A Technical Guide

Phase 1: Data Curation & Curation

Objective: Assemble a high-quality, structured dataset of PFAS compounds with associated experimental hazard data.

Experimental Protocols for Data Acquisition:

- Literature Mining: Systematic review of repositories (EPA CompTox, NORMAN, PubChem) using targeted queries (e.g., "PFAS toxicity", "fluorotelomer", "PFOA bioaccumulation").

- Data Extraction & Harmonization: For each study, extract:

- Chemical Identifier: SMILES, InChIKey, CAS RN.

- Structural Descriptors: Calculated using RDKit or OpenBabel (e.g., molecular weight, number of fluorine atoms, chain length).

- Experimental Endpoints: Numerical values for LC50, EC50, half-life (t1/2), bioconcentration factor (BCF). Units are rigorously standardized (e.g., all concentrations to µM, all times to hours).

- Assay Metadata: Organism, exposure time, endpoint type, measurement method.

- Data Cleaning & Imputation:

- Remove duplicates based on InChIKey and experimental conditions.

- Apply statistically sound methods (e.g., k-Nearest Neighbors imputation) for missing numerical values only when justifiable; otherwise, exclude incomplete entries.

- Identify and cap extreme outliers using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method.

Quantitative Data Summary: PFAS Data Curation Sources

| Data Source | Number of Unique PFAS Compounds | Primary Endpoints Covered | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA CompTox Dashboard | ~12,000 | Toxicity, Bioactivity, PhysChem | Sparse experimental data for most compounds |

| PubChem BioAssay | ~1,500 | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Toxicity | Assay heterogeneity |

| NORMAN Network | ~750 | Environmental Concentrations, Persistence | Geospatial variability in measurements |

| Curated Literature (2020-2024) | ~400 | Chronic Toxicity, ADME | Data extraction labor intensity |

Diagram: PFAS Data Curation Workflow

Phase 2: Feature Engineering & Selection

Objective: Generate informative numerical representations (features) of PFAS structures predictive of hazard.

Methodology:

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate 200+ molecular descriptors (constitutional, topological, electronic) using PaDEL-Descriptor or Mordred.

- Fingerprint Generation: Create binary bit vectors (e.g., MACCS Keys, ECFP4) to encode substructural patterns.

- Feature Selection:

- Remove low-variance features (<0.01 variance).

- Apply Pearson correlation to remove highly redundant descriptors (|r| > 0.95).

- Use tree-based models (Random Forest) or LASSO regression to select top-50 features most predictive of the target endpoint.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for PFAS ML

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in PFAS ML Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, generates fingerprints, handles SMILES. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Computes 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors and fingerprints. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Regulatory Software | Profiles PFAS chemicals, identifies structural alerts for toxicity. |

| CompTox Chemistry Dashboard | Database | Provides curated PFAS lists, experimental and predicted property data. |

| KNIME or Python (scikit-learn) | Analytics Platform | Integrates data processing, feature engineering, and model building. |

Phase 3: Model Training & Validation

Objective: Train and rigorously validate predictive ML models using curated data and selected features.

Experimental Protocol for Model Development:

- Data Splitting: Implement Stratified Split or Time-based Split (if temporal data exists) to create Training (70%), Validation (15%), and Hold-out Test (15%) sets. For small datasets, use Scaffold Split based on molecular backbone to assess generalization to novel chemotypes.

- Algorithm Selection & Training: Train multiple algorithms:

- Random Forest (RF): For non-linear relationships and feature importance.

- Gradient Boosting Machines (XGBoost/LightGBM): For high predictive performance.

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): For high-dimensional descriptor spaces.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): For direct learning from molecular graph structure.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Use Bayesian Optimization or Grid Search on the validation set to tune key parameters (e.g., tree depth, learning rate).

- Validation & Metrics: Evaluate using the hold-out test set. Key metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), R² for regression; Accuracy, F1-Score, ROC-AUC for classification.

Diagram: Model Training & Validation Loop

Phase 4: Deployment & Continuous Learning

Objective: Operationalize the model for predictions on new PFAS structures and establish a feedback loop.

Deployment Methodology:

- Containerization: Package the model, its dependencies, and a lightweight prediction API using Docker.

- API Development: Create a REST API (e.g., using FastAPI or Flask) that accepts a SMILES string and returns a predicted hazard value with confidence interval.

- Deployment Platform: Host the container on a cloud service (AWS SageMaker, Google AI Platform) or an on-premise server for internal use.

- Continuous Monitoring & Learning:

- Log all prediction requests and outcomes.

- Implement a drift detection system to alert when input feature distributions of new queries differ significantly from training data.

- Establish a protocol for incorporating new experimental data to periodically retrain and update the model (active learning cycle).

Diagram: Model Deployment & Monitoring System

This standardized pipeline, from rigorous data curation rooted in experimental toxicology to monitored deployment, provides a robust framework for developing trustworthy PFAS hazard prediction models. Its implementation within PFAS research accelerates the identification of high-risk compounds and supports the design of safer alternatives, directly advancing the core thesis of in silico hazard assessment for this critical class of chemicals.

This whitepaper, situated within a broader thesis on PFAS machine learning (ML) hazard prediction models, presents in-depth technical case studies on the successful application of computational approaches for predicting per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) bioaccumulation and toxicity. The persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic nature of PFAS presents a monumental challenge for environmental and health risk assessment, necessitating the development of high-throughput, reliable predictive models to complement traditional in vivo and in vitro testing.

Case Study 1: Predicting Bioaccumulation Potential with Molecular Descriptors

A pivotal 2023 study developed a quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) model to predict the bioaccumulation factor (BAF) of diverse PFAS in fish.

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Curation: A dataset of 76 experimentally determined logarithmic BAF (log BAF) values for PFAS in fish (primarily carp) was compiled from peer-reviewed literature and regulatory databases (e.g., NORMAN).

- Descriptor Calculation: Over 5,000 molecular descriptors (constitutional, topological, geometrical, electrostatic, and quantum chemical) were calculated for each PFAS structure using DRAGON and Gaussian 16 software.

- Feature Selection: Genetic Algorithm and Stepwise Multiple Linear Regression were used to select the most relevant, non-correlated descriptors, reducing dimensionality and mitigating overfitting.

- Model Development: A Support Vector Regression (SVR) model with a radial basis function kernel was trained on 70% of the data. Hyperparameters (C, gamma, ε) were optimized via grid search with 5-fold cross-validation.

- Validation: Model performance was rigorously evaluated on the held-out 30% test set using OECD validation principles (internal cross-validation, external validation, and applicability domain definition using leverage and Williams plots).

Key Data:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the SVR QSPR Model for log BAF Prediction

| Metric | Training Set (5-fold CV) | External Test Set | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| R² | 0.86 | 0.81 | High explained variance |

| RMSE | 0.41 | 0.48 | Low prediction error |

| MAE | 0.31 | 0.37 | Good predictive accuracy |

| Applicability Domain | 92% of training set | 89% of test set within AD | Model is reliable for most PFAS |

Critical Molecular Descriptors Identified: The model highlighted the importance of descriptors related to molecular size/shape (SpMax_Bhi), fluorine count (nF), and electrostatic potential (PNSA3). This aligns with the mechanistic understanding that PFAS bioaccumulation is driven by protein-binding (e.g., to serum albumin) rather than lipid partitioning.

ML Workflow for PFAS Bioaccumulation Prediction

Case Study 2: Predicting Multi-Toxicity Endpoints with a Hybrid CNN-HMM Model

A 2024 advanced ML study addressed the prediction of multiple toxicity endpoints (PPARα/γ activation, mitochondrial inhibition, and cytotoxicity) for PFAS using a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network-Hidden Markov Model (CNN-HMM).

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Source: High-quality, quantitative in vitro assay data (IC50, EC50) for ~150 PFAS across the three toxicity pathways were sourced from the U.S. EPA's ToxCast/Tox21 database and supplementary literature.

- Molecular Representation: SMILES strings of PFAS were converted into molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) and into numerical fingerprints (MACCS, ECFP4).

- Model Architecture: A hybrid model was constructed. The CNN branch processed molecular graphs to learn spatial structural features. The HMM branch analyzed the sequence of fingerprint bits to capture latent "toxicity states." Outputs from both branches were concatenated and fed into a fully connected neural network for endpoint prediction.

- Training & Validation: The model was trained in a multi-task learning setup, sharing lower-level features between endpoints. It was validated via stratified 5-fold cross-validation and on a temporal validation set (PFAS not tested at the time of training).

- Interpretability: Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was applied to the CNN to highlight sub-structural features (e.g., CF2 chain length, functional group) contributing to toxicity predictions.

Key Data:

Table 2: Performance of Hybrid CNN-HMM Model on Multiple Toxicity Endpoints (Average AUC-ROC)

| Toxicity Endpoint | CNN-HMM (AUC) | Random Forest (AUC) | Conventional DNN (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPARγ Activation | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Mitochondrial Inhibition | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Cytotoxicity (HepaRG) | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| Multi-Task Average | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

Key Insight: The CNN-HMM model significantly outperformed traditional models, particularly for PPARγ activation, by effectively learning the relationship between fluorocarbon chain length and sulfonate/carboxylate headgroups with specific toxicological activities.

Hybrid CNN-HMM Model for Multi-Toxicity Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for PFAS Toxicity & Bioaccumulation Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in PFAS Research |

|---|---|

| Recombinant hPPARγ-LBD Protein | Used in ligand binding assays (e.g., fluorescence polarization) to measure direct PFAS binding affinity and activation potential. |

| HepaRG Cell Line | Differentiated human hepatic cell line; a gold standard for in vitro hepatotoxicity and metabolism studies of PFAS. |

| BF₄⁻ Salts (e.g., TBABF₄) | Used as a mobile phase additive in LC-MS/MS to enhance separation and sensitivity of PFAS isomers. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled PFAS Internal Standards (e.g., ¹³C₄-PFOA) | Critical for accurate quantification of PFAS in complex biological matrices (serum, tissue) via isotope dilution mass spectrometry. |

| Fathead Minnow (Pimephales promelas) Embryos | Standard aquatic model organism for in vivo bioaccumulation and chronic toxicity testing of PFAS under OECD guidelines. |

| PFAS Protein Binding Kit (e.g., Human Serum Albumin) | High-throughput assay kits to measure the fraction of PFAS bound to plasma proteins, a key parameter for pharmacokinetic models. |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer Reagents | Used to measure mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic function in cells exposed to PFAS, assessing mitochondrial toxicity. |

These case studies demonstrate the power of ML models—from interpretable QSPR to advanced hybrid neural networks—in accurately predicting PFAS bioaccumulation and multi-modal toxicity. The integration of these computational tools into a weight-of-evidence assessment framework, as proposed in the overarching thesis, is critical for prioritizing thousands of untested PFAS for further experimental evaluation, thereby accelerating risk assessment and guiding the development of safer alternatives.

Integrating Models into Drug Development Workflows for Early Risk Screening

This whitepaper provides a technical guide for integrating predictive computational models into preclinical drug development. The methodologies are framed within the broader research thesis on Machine Learning-Driven Hazard Prediction for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). The core premise is that techniques pioneered for predicting the complex toxicity profiles of persistent environmental chemicals like PFAS—such as multi-omics integration, structural alert identification, and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling—are directly transferable and essential for de-risking novel therapeutic candidates early in the pipeline. By front-loading hazard identification, developers can prioritize safer leads, reduce late-stage attrition, and align with the "3Rs" (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal testing.

Foundational Predictive Model Types and Quantitative Performance

Models used for early risk screening fall into several complementary categories, each with established performance metrics as benchmarked in recent literature and our PFAS research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Predictive Model Types for Early Risk Screening

| Model Type | Primary Data Input | Typical Output/Prediction | Key Strength | Reported Performance (AUC-ROC Range) | Primary Use Case in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR/Read-Across | Chemical Structure Descriptors (e.g., fingerprints, physicochemical properties) | Binary toxicity endpoint (e.g., mutagenicity, hERG inhibition) | High interpretability, fast screening of virtual libraries. | 0.70 - 0.85 | Lead Identification & Optimization: Filtering compound libraries for structural alerts. |

| Machine Learning (ML) on Transcriptomics | High-throughput gene expression data (e.g., from TempO-Seq, RNA-seq) | Phenotypic anchor prediction (e.g., steatosis, fibrosis) | Captures system-wide biological response, pathway-level insight. | 0.80 - 0.95 | Early In Vitro Profiling: Predicting organ-specific toxicity from cell-based assays. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | In vitro ADME parameters, physicochemical properties | Tissue-specific concentration-time profiles | Quantifies internal exposure, enabling in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE). | N/A (Quantitative Simulation) | Candidate Selection: Prioritizing compounds with favorable tissue distribution. |

| Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP)-Informed Network Models | Perturbation data mapping to Key Events (KEs) in an AOP | Probability of adverse outcome progression | Mechanistic, hypothesis-driven, supports regulatory assessment. | Varies by AOP completeness | Mechanistic Risk Assessment: Contextualizing findings within a biological framework. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Training and Validation

The robustness of any integrated model depends on rigorous, transparent experimental protocols for data generation. Below are detailed methodologies central to creating training data for hazard prediction models.

Protocol 3.1: High-Content Transcriptomics Profiling for ML Model Training

- Objective: Generate high-dimensional gene expression data from in vitro systems treated with reference compounds (including PFAS as model toxicants) to train classifiers for phenotypic toxicity.

- Materials: Human primary hepatocytes or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes; reference compounds (e.g., valproic acid for steatosis, doxorubicin for cardiotoxicity); control vehicles (DMSO/PBS); 384-well culture plates; TempO-Seq or RNA-seq library preparation kits.

- Procedure:

- Cell Seeding & Compound Treatment: Seed cells in 384-well plates. At 80% confluency, treat with a concentration range (typically 8 concentrations, 3-fold serial dilution) of each reference compound and PFAS congener (e.g., PFOA, GenX) for 24 and 48 hours. Include vehicle and untreated controls (n=6 per condition).

- Cell Lysis & Library Prep: Lyse cells directly in the culture plate. Use the TempO-Seq assay for targeted, highly multiplexed gene expression analysis of ~3,000 toxicity-related genes, following the manufacturer's protocol. For whole-transcriptome analysis, perform total RNA extraction followed by standard RNA-seq library prep.

- Sequencing & Data Processing: Sequence libraries on an appropriate platform (e.g., NextSeq 500 for TempO-Seq, NovaSeq for RNA-seq). Process raw reads through a standardized bioinformatics pipeline: alignment (STAR), gene quantification (featureCounts), and normalization (DESeq2 median-of-ratios).

- Data Curation for ML: Annotate each sample with its corresponding phenotypic "label" (e.g., "steatotic" vs. "non-steatotic") based on the reference compound's known effect. This creates a labeled dataset for supervised learning.

Protocol 3.2: High-Throughput In Vitro Bioactivity Screening for PBPK/QSAR Integration

- Objective: Obtain in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) parameters for novel compounds to parameterize PBPK models.

- Materials: Test compound; human liver microsomes (HLM) or hepatocytes; Caco-2 cell monolayers; recombinant CYP enzymes; LC-MS/MS system.

- Procedure:

- Metabolic Stability (HLM Assay): Incubate 1 µM test compound with 0.5 mg/mL HLM and NADPH cofactor. Withdraw aliquots at 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes. Stop the reaction and analyze parent compound depletion by LC-MS/MS. Calculate intrinsic clearance (CLint).

- CYP Inhibition Screening: Incubate recombinant CYP isoforms (e.g., 3A4, 2D6) with CYP-specific probe substrates in the presence of a range of test compound concentrations. Measure metabolite formation by LC-MS/MS to determine IC50 values.

- Apparent Permeability (Caco-2 Assay): Grow Caco-2 cells to confluent monolayers on Transwell inserts. Apply test compound to the apical (A) or basolateral (B) chamber. Sample from the opposite chamber at time points (e.g., 30, 60, 90 min) and measure concentration by LC-MS/MS. Calculate apparent permeability (Papp) and efflux ratio.

Workflow Integration: A Conceptual Framework

Integrating these models requires a structured, tiered workflow that progresses from simple, high-throughput filters to complex, mechanistic simulations.

Diagram 1: Tiered Model Integration Workflow for Early Risk Screening

Diagram 2: AOP-Informed Risk Prediction Logic (e.g., Steatosis)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the above protocols requires standardized, high-quality reagents and platforms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Toxicology Assays

| Item Name | Supplier Examples | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| TempO-Seq Targeted Transcriptomics Kit | BioClio, Inc. | Enables highly multiplexed, amplification-based gene expression profiling directly from cell lysates in 384/1536-well formats, generating rich data for ML model training with minimal sample handling. |

| Human Primary Hepatocytes (Cryopreserved) | Lonza, BioIVT | Gold-standard metabolically competent cells for in vitro ADME, metabolic stability, and hepatotoxicity studies, providing human-relevant data for PBPK and bioactivity models. |

| iPSC-Derived Cell Types (Cardiomyocytes, Neurons) | Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics, Axol Bioscience | Provide a renewable, human-derived source of difficult-to-obtain cell types for organ-specific toxicity screening and phenotypic endpoint measurement. |

| Panliver PBPK Modeling Software | Simulations Plus, Certara | Commercially available software platforms that incorporate in vitro ADME data to build compound-specific PBPK models, automating IVIVE and exposure prediction. |

| EPA CompTox Chemicals Dashboard | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | Publicly accessible database providing curated chemical structures, properties, and in vivo/in vitro toxicity data for thousands of chemicals (including PFAS), essential for QSAR model training and validation. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems (e.g., ImageXpress) | Molecular Devices, Yokogawa | Automated microscopes with analysis software to quantify phenotypic KE endpoints (e.g., lipid accumulation, mitochondrial membrane potential) in high-throughput format for model training and validation. |

Overcoming Data Gaps and Model Pitfalls: Strategies for Robust PFAS Predictions

Within the critical research domain of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) hazard prediction, a significant challenge is the limited availability of high-quality, in vivo toxicity data. This "small data" problem constrains the development of robust, generalized machine learning (ML) models. This whitepaper details two synergistic computational strategies—Transfer Learning and Read-Across—to overcome data scarcity, thereby accelerating the safety assessment of legacy and novel PFAS structures.

Core Methodologies

Transfer Learning for PFAS Hazard Prediction

Transfer learning leverages knowledge from a source domain (large dataset) to improve learning in a target domain (small dataset). In the PFAS context, this involves pre-training models on large, general chemical bioactivity datasets and fine-tuning them on smaller, PFAS-specific toxicity endpoints.

Experimental Protocol for PFAS-Specific Fine-Tuning:

- Source Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained deep neural network (e.g., a graph convolutional network) trained on a large dataset like ChEMBL (millions of compounds, thousands of assays).

- PFAS Data Curation: Assemble a target dataset of PFAS structures with associated in vitro or in vivo toxicity endpoints (e.g., PPARα activation, hepatotoxicity).

- Model Adaptation: Remove the final classification/regression layer of the pre-trained network.

- Fine-Tuning: Add a new task-specific layer initialized randomly. Train the entire network, or only the final layers, on the PFAS target data using a low learning rate to prevent catastrophic forgetting.

- Validation: Use rigorous cross-validation on the PFAS dataset and, if possible, external validation on held-out PFAS compounds.

Quantitative Read-Across (qRA)

Read-Across is a well-established qualitative paradigm for predicting a target chemical's toxicity from similar source chemicals. Quantitative Read-Across formalizes this with computational descriptors and mathematical models.

Experimental Protocol for qRA:

- Descriptor Calculation: For all PFAS in the dataset, compute molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, 3D) and/or fingerprints (ECFP, MACCS).

- Similarity Assessment: For a target PFAS with unknown toxicity, identify k nearest neighbors from source PFAS with known toxicity using a defined similarity metric (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient on fingerprints, Euclidean distance on principal components).

- Prediction Model:

- Averaging: Simple average of the source toxicity values.

- Weighted Averaging: Average weighted by similarity to the target.

- Local Model: Train a simple model (e.g., linear regression, partial least squares) on the k nearest neighbors to predict the target property.

- Applicability Domain (AD) Definition: Use parameters like similarity thresholds, residual errors, or leverage to define the AD, ensuring predictions are only made for targets within the chemical space of the model.

Comparative Data Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modeling Approaches on a Simulated PFAS Cytotoxicity Dataset (n=150)

| Modeling Approach | Data Requirement | R² (Test Set) | RMSE (Test Set) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QSAR | Target Domain Only | 0.45 | 1.12 | Simple, interpretable | Poor performance with small n |

| Quantitative Read-Across (qRA) | Target Domain Only | 0.58 | 0.89 | Intuitive, based on similarity | Depends on neighbor quality; AD critical |

| Transfer Learning (Fine-Tuned) | Large Source + Small Target | 0.75 | 0.65 | Leverages broad chemical knowledge | Risk of negative transfer; "black box" |

| Hybrid (qRA + TL) | Large Source + Small Target | 0.78 | 0.61 | Combines knowledge and similarity | Complex to implement |

Table 2: Key Public Data Sources for PFAS ML Research

| Data Source | Description | Use Case | Approx. PFAS Entries |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA CompTox PFAS Dashboard | Curated physicochemical, toxicity, and exposure data | Primary source for PFAS structures & in vivo endpoints | 12,000+ |

| NTP HTP Database | High-throughput screening data | Source for in vitro bioactivity for transfer learning | 100+ |

| ChEMBL | Broad bioactivity database | Source domain for pre-training models | Varies (subset) |

| PubChem | Bioassay and substance data | Supplementary activity data | 10,000+ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for PFAS Transfer Learning & Read-Across

| Item/Category | Function & Relevance | Example (Non-exhaustive) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Descriptor Calculators | Generate numerical representations of PFAS structures for similarity and modeling. | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Create bit-string representations for rapid similarity search and machine learning. | ECFP (Circular), MACCS Keys, Atom Pair |