Mastering Environmental Sampling: Foundational Methods, Applications, and Error Management for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the fundamental principles and practices of environmental sampling methodology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering Environmental Sampling: Foundational Methods, Applications, and Error Management for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the fundamental principles and practices of environmental sampling methodology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the entire process from defining research questions and selecting appropriate sampling designs to implementing specific techniques for air, water, soil, and biological matrices. A strong emphasis is placed on understanding and mitigating sampling errors, validating data quality, and applying robust quality assurance protocols. The content synthesizes current guidelines and scientific research to equip professionals with the knowledge to generate reliable, defensible data for environmental assessments and related biomedical applications.

The Blueprint of Science: Building Your Environmental Sampling Foundation

Defining Clear Research Questions and Testable Hypotheses

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for formulating precise research questions and testable hypotheses within environmental systems research. Framed within the broader context of sampling methodology fundamentals, this whitepaper establishes the critical linkage between hypothesis construction and subsequent methodological choices in environmental investigation. The guidance emphasizes statistical testability, quantitative data quality assurance, and methodological rigor necessary for generating reliable evidence in environmental monitoring, assessment, and remediation studies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with complex environmental systems, this document integrates current best practices for ensuring data integrity from initial question formulation through final analytical measurement.

Defining clear research questions and testable hypotheses represents the foundational first step in the scientific process for environmental systems research. The formulation process demands careful consideration of the system's complexity, variability, and scale, while ensuring the resulting hypotheses can direct appropriate sampling methodologies and analytical approaches. Within environmental contexts, this requires integrating prior knowledge of contaminant fate and transport, ecosystem dynamics, and human exposure pathways with testable predictions that can be evaluated through empirical observation and measurement.

The integrity of all subsequent research phases—from sampling design and data collection through statistical analysis and interpretation—depends fundamentally on the clarity and precision of the initial research questions. Ill-defined questions inevitably produce ambiguous results, while testable hypotheses provide the logical framework for drawing meaningful inferences from environmental data. The process must therefore be considered an integral component of sampling methodology rather than a preliminary exercise, particularly given the spatial and temporal heterogeneity characteristic of environmental systems and the practical constraints on sample collection and analysis.

Theoretical Framework: Connecting Questions, Hypotheses, and Methodology

The Hierarchical Relationship in Research Design

Scientific investigation in environmental research follows a logical hierarchy that originates with broad research questions and culminates in specific, measurable predictions. This hierarchy ensures methodological coherence throughout the research process, with each level informing the next in a cascade of increasing specificity:

- Broad Research Questions identify the general phenomena of interest and knowledge gaps within environmental systems (e.g., "What is the impact of urban runoff on stream ecosystem health?").

- Focused Research Questions narrow the scope to specific, measurable components (e.g., "How do tyre and road wear particle (TRWP) concentrations correlate with macroinvertebrate diversity indices in urban streams?").

- Testable Hypotheses translate focused questions into specific, falsifiable predictions using precise variables and expected relationships (e.g., "Streams with TRWP concentrations exceeding 100 mg/kg sediment will show a 25% reduction in Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera (EPT) richness compared to reference sites").

- Methodological Specifications derive directly from hypotheses, determining sampling designs, analytical methods, and statistical approaches needed to test the predictions (e.g., sampling locations, particle identification methods, and statistical tests).

Characteristics of Testable Hypotheses in Environmental Research

Effective hypotheses in environmental systems research must possess specific attributes to be scientifically valuable and methodologically actionable:

- Precision and Specificity: Hypotheses must specify the exact variables involved, their expected relationships, and the direction of effect. Vague predictions about "affecting" or "influencing" environmental parameters cannot direct appropriate sampling designs or yield meaningful tests.

- Falsifiability: A hypothesis must be structured in a way that observable evidence could potentially prove it wrong. This requires defining clear criteria for rejection or support based on statistical thresholds established during the design phase.

- Methodological Testability: The hypothesis must be structured around variables that can be practically measured with available sampling and analytical techniques within environmental constraints. For example, hypotheses about transient contamination events require sampling methods capable of capturing episodic exposures.

- Contextual Relevance: Hypotheses should be grounded in the theoretical understanding of environmental processes and prior research, while addressing questions of practical significance for regulation, remediation, or public health protection.

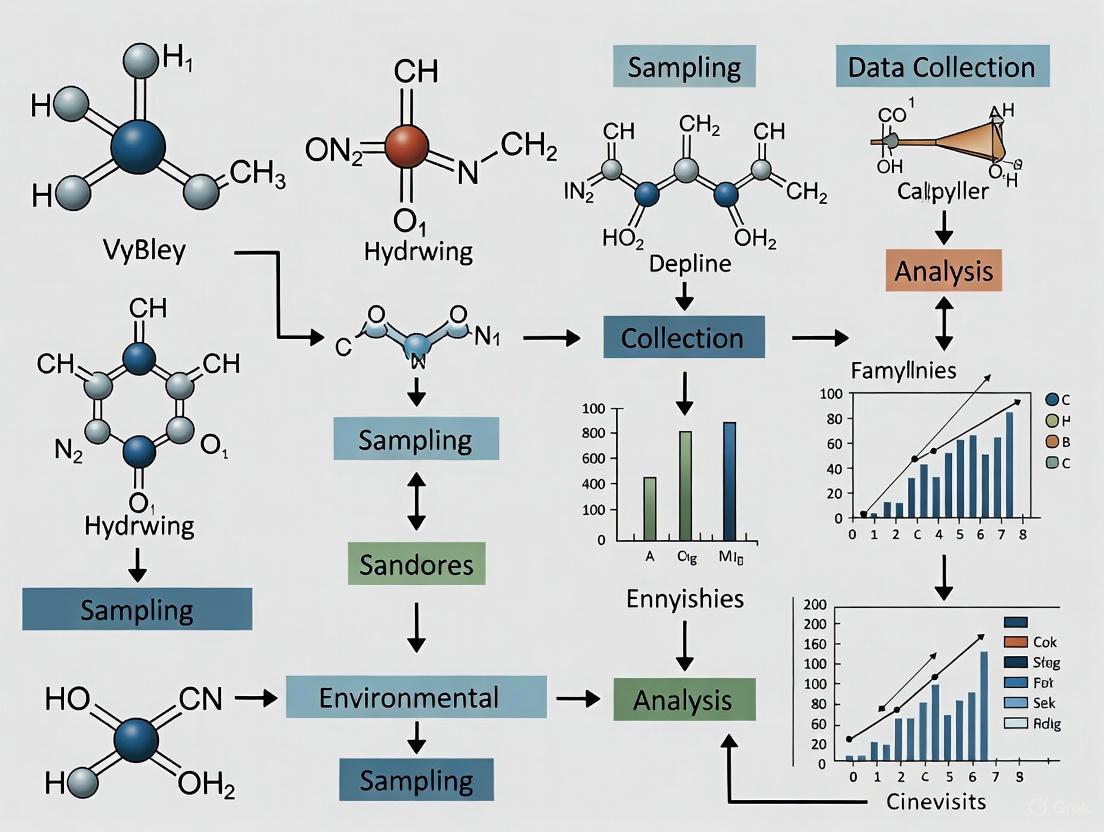

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow connecting research questions to methodological implementation and data interpretation within environmental systems research:

Diagram 1: Research design workflow for environmental studies

Quantitative Foundations for Hypothesis Testing

Data Quality Requirements for Valid Hypothesis Tests

The testing of environmental hypotheses relies fundamentally on quantitative data quality assurance, defined as the systematic processes and procedures used to ensure the accuracy, consistency, reliability, and integrity of data throughout the research process [1]. Effective quality assurance helps identify and correct errors, reduce biases, and ensure data meets the standards required for statistical analysis and reporting. Without rigorous quality assurance, even well-formulated hypotheses may yield unreliable conclusions due to data quality issues rather than true environmental effects.

Key considerations for data quality in environmental hypothesis testing include:

- Accuracy and Precision: Ensuring measurements correctly represent environmental parameters and do so consistently across sampling events and locations.

- Completeness: Maximizing the proportion of valid data obtained compared to the total amount planned for collection, with specific protocols for handling missing environmental data.

- Comparability: Establishing that data collected from different locations, times, or by different field teams can be meaningfully compared for hypothesis testing.

- Representativeness: Verifying that data accurately characterizes the environmental conditions at the sampling point and time relative to the hypothesis being tested.

Statistical Considerations in Hypothesis Formulation

Environmental hypotheses must be structured with explicit consideration of the statistical approaches that will ultimately test them. This requires advance planning for:

- Sample Size Requirements: Statistical power analyses should inform sampling designs to ensure adequate capability to detect environmentally significant effects. Underpowered studies may fail to identify important contamination gradients or biological impacts.

- Data Distribution Assumptions: Hypothesis tests often assume specific data distributions (e.g., normality), which must be verified through measures of normality of distribution including kurtosis (peakedness or flatness) and skewness (deviation around the mean) [1]. Values of ±2 for both measures typically indicate normality of distribution, though with larger environmental samples these values are more likely to be violated.

- Multiple Comparison Adjustments: Environmental studies frequently involve numerous simultaneous measurements, increasing the risk of spurious significant findings. Methods such as Bonferroni correction control the family-wise error rate when multiple hypotheses are tested against the same dataset [1].

Table 1: Statistical Tests for Different Environmental Data Types and Research Questions

| Research Question Type | Data Measurement Level | Normality Distribution | Appropriate Statistical Tests | Common Environmental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison between groups | Nominal | Not applicable | Chi-squared test, Logistic regression | Contaminant presence/absence across land use types; Species occurrence patterns |

| Comparison between groups | Ordinal | Not applicable | Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis | Pollution tolerance rankings; Ordinal habitat quality scores |

| Comparison between groups | Scale/Continuous | Meets normality assumptions | t-test, ANOVA | Concentration comparisons between reference and impacted sites; Treatment efficacy assessment |

| Relationship between variables | Scale/Continuous | Meets normality assumptions | Pearson correlation, Linear regression | Contaminant concentration correlations; Dose-response relationships |

| Relationship between variables | Ordinal or non-normal continuous | Non-normal distribution | Spearman's rank correlation, Nonlinear regression | Biological diversity vs. pollution gradients; Turbidity-flow rate relationships |

| Predictive modeling | Mixed types | Varies by variable | Multiple regression, Generalized linear models | Contaminant fate prediction; Exposure assessment models |

Methodological Protocols for Environmental Sampling and Analysis

Sampling Design and Implementation

The testing of environmental hypotheses requires sampling methodologies that accurately represent the system under study while controlling for variability and potential confounding factors. The Environmental Sampling and Analytical Methods (ESAM) program provides comprehensive frameworks for sample collection across various environmental media including water, air, road dust, and sediments [2]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Spatial and Temporal Design: Sampling must capture the appropriate spatial scales (e.g., point source gradients vs. regional patterns) and temporal frequencies (e.g., episodic events vs. chronic exposure) relevant to the research hypothesis.

- Sample Handling and Preservation: Proper containers, preservation techniques, and holding times must be established a priori to maintain sample integrity between collection and analysis. The Sample Collection Information Documents (SCID) provide specific guidance on these parameters for chemical, radiological, pathogen, and biotoxin analyses [2].

- Quality Control Samples: Field blanks, trip blanks, duplicate samples, and matrix spikes should be incorporated into the sampling design to quantify and control for potential contamination, variability, and analytical recovery issues.

Analytical Method Selection for Hypothesis Testing

The selection of analytical methods must align with the specificity and sensitivity requirements inherent in the research hypotheses. Different analytical techniques offer varying capabilities for detecting, identifying, and quantifying environmental contaminants:

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Environmental Contaminant Detection and Quantification

| Analytical Technique | Detection Principle | Target Analytes | Sample Matrix Applications | Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis (SEM-EDX) | Morphological and elemental characterization | Microparticles including tyre and road wear particles (TRWPs) | Road dust, sediments, air particulates | Provides particle number, size, and elemental composition; Limited molecular specificity |

| Two-dimensional Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (2D GC-MS) | Volatile and semi-volatile compound separation and identification | Organic contaminants, chemical biomarkers | Water, soil, biota, air samples | Enhanced separation power for complex environmental mixtures; Requires extensive method development |

| Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Liquid separation with selective mass detection | Polar compounds, pharmaceuticals, modern pesticides | Water, wastewater, biological tissues | High sensitivity and selectivity; Can be matrix-sensitive |

| Immunoassay | Antibody-antigen binding | Specific compound classes (e.g., PAHs, PCBs) | Water, soil extracts, biological fluids | Rapid screening capability; Potential cross-reactivity issues |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | DNA amplification and detection | Pathogens, fecal indicator bacteria, microbial source tracking | Water, sediments, biological samples | High specificity to target organisms; Does not distinguish viable vs. non-viable cells |

For complex environmental samples such as tyre and road wear particles (TRWPs), a combination of microscopy and thermal analysis techniques has been identified as optimal for determining both particle number and mass [3]. The analytical approach must provide sufficient specificity to distinguish target analytes from complex environmental matrices while delivering the quantitative rigor needed for statistical hypothesis testing.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated process from hypothesis formulation through analytical measurement for environmental contaminants:

Diagram 2: Environmental contaminant analysis workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Environmental Sampling and Analysis

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research Process | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection Containers | EPA-approved vials for volatile organic analysis; Sterile containers for microbiological sampling | Maintain sample integrity during transport and storage; Prevent contamination or adsorption | Material compatibility with analytes; Preservation requirements; Cleaning verification |

| Chemical Preservatives | Hydrochloric acid for metal stabilization; Sodium thiosulfate for dechlorination | Stabilize target analytes; Prevent biological degradation; Maintain original chemical speciation | ACS-grade or higher purity; Verification of preservative efficacy; Blank monitoring |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials; Isotope-labeled internal standards; Calibration solutions | Instrument calibration; Quantification accuracy assessment; Recovery determination | Traceability to certified references; Purity documentation; Stability monitoring |

| Sample Extraction Materials | Solid-phase extraction cartridges; Solvents (dichloromethane, hexane); Accelerated solvent extraction cells | Isolation and concentration of target analytes from environmental matrices | Lot-to-lot reproducibility; Extraction efficiency; Background contamination levels |

| Filtration Apparatus | Glass fiber filters; Membrane filters; Syringe filters | Particulate removal; Size fractionation; Sample clarification | Pore size consistency; Extractable contamination; Loading capacity |

| Quality Control Materials | Field blanks; Matrix spikes; Laboratory control samples; Certified reference materials | Quantification of method bias, precision, and potential contamination | Representativeness to sample matrix; Stability; Concentration relevance |

Data Integrity and Reporting Standards

Data Cleaning and Validation Protocols

Prior to statistical analysis intended to test research hypotheses, environmental data must undergo rigorous quality assurance procedures. Data cleaning reduces errors or inconsistencies and enhances overall data quality, though these processes are often underreported in research literature [1]. Essential data cleaning steps include:

- Checking for Duplications: Identification and removal of identical data records, particularly relevant when automated data logging systems or multiple field crews are employed.

- Management of Missing Data: Establishment of thresholds for inclusion/exclusion of incomplete data records using statistical approaches such as Little's Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test to determine patterns of missingness [1].

- Anomaly Detection: Identification of data that deviate from expected patterns through descriptive statistics and visualization techniques to ensure all measurements align with expected ranges and distributions.

- Data Transformation and Summation: Construction of composite variables or indices according to established protocols (e.g., clinical definitions for biomarker interpretation or summation of Likert-scale items to construct-level variables).

Transparent Reporting of Findings

The interpretation and presentation of statistical data must be conducted in a clear and transparent manner to enable proper evaluation of research hypotheses [1]. Key reporting principles include:

- Comprehensive Reporting: Avoid selective reporting of only statistically significant results, as both significant and non-significant findings provide valuable scientific evidence, particularly in environmental studies where negative findings about contaminant impacts can be equally informative.

- Multiplicity Adjustment: Correct for multiple comparisons when numerous statistical tests are conducted, using methods such as Bonferroni correction to maintain appropriate experiment-wise error rates [1].

- Contextualization with Limitations: Acknowledge methodological constraints, potential confounding factors, and data quality considerations that might affect hypothesis tests and their interpretation.

The formulation of clear research questions and testable hypotheses establishes the essential foundation for rigorous environmental systems research. When properly constructed, hypotheses directly inform sampling methodologies, analytical approaches, and statistical analyses, creating a coherent framework for scientific investigation. The process requires integration of conceptual understanding of environmental processes with practical methodological considerations to ensure that resulting data can provide meaningful tests of theoretical predictions. By adhering to structured approaches for hypothesis development, sampling design, and data quality assurance, environmental researchers can generate reliable evidence to address complex challenges in environmental assessment, remediation, and protection.

Identifying Knowledge Gaps and Setting Precise Study Objectives

In environmental systems research, the integrity of any study is fundamentally anchored in the rigor of its sampling methodology. A poorly designed sampling strategy can introduce biases that render data unreliable and conclusions invalid, regardless of the sophistication of subsequent analytical techniques. The primary challenge researchers face is ensuring that data collected from a subset of the environment—the sample—can yield unbiased, representative, and meaningful inferences about the larger system of interest—the population [4] [5]. This guide provides a systematic framework for identifying knowledge gaps in existing sampling protocols and for formulating precise, defensible study objectives that advance the fundamentals of environmental sampling methodology. The process begins with a critical evaluation of current practices against the foundational principle of representativeness—the extent to which a sample fairly mirrors the diverse characteristics of the population from which it is drawn [5].

Foundational Concepts in Sampling Methodology

Key Terminology and Definitions

A clear understanding of core concepts is essential for critiquing existing literature and designing robust studies. The following terms form the lexicon of sampling methodology.

- Population: The entire group of individuals, items, or environmental units (e.g., all the sediment in a lake, all the air in an urban basin) that is the target of the research inquiry [4] [5].

- Sample: A subset of the population selected for actual measurement or analysis [4] [5]. The sample is the primary source of empirical data.

- Sampling Frame: The actual list, map, or database from which the sample is drawn. An ideal sampling frame includes every unit in the target population and excludes all others [4] [5]. A flawed frame is a major source of bias.

- Representative Sample: A sample that accurately reflects the distribution of key characteristics and variability present in the overall population. Achieving this is the central goal of most probability sampling methods [5].

- Sampling Bias: A systematic error that occurs when the sample is not representative of the population, leading to skewed estimates and invalid conclusions [4]. The classic "Dewey Beats Truman" election forecast is a historical example of sampling bias caused by a frame (telephone owners) that was not representative of the voting population [5].

Classification of Sampling Methods

Sampling methods are broadly categorized into two paradigms, each with distinct philosophies, techniques, and implications for inference. The choice between them is a fundamental strategic decision in research design.

Table 1: Core Sampling Methods for Environmental Research

| Method | Core Principle | Key Procedure | Best Use Cases in Environmental Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability Sampling | Every unit in the population has a known, non-zero chance of selection [4] [5]. | Selection via random processes. | Quantitative studies requiring statistical inference about population parameters (e.g., mean contaminant concentration) [4]. |

| Simple Random | All possible samples of size n are equally likely [5]. |

Random selection from a complete sampling frame (e.g., using a random number generator). | Baseline studies where the population is relatively homogeneous and a complete frame exists [4] [5]. |

| Stratified | Population is divided into homogenous subgroups (strata) [4]. | Separate random samples are drawn from each stratum. | To ensure representation of key subgroups (e.g., different soil types, depth zones in a water column) and to improve precision [4] [5]. |

| Systematic | Selection at regular intervals from an ordered list [4]. | Select a random start, then sample every kth unit. | Field surveys for efficient spatial or temporal coverage (e.g., sampling every 10 meters along a transect) [4]. |

| Cluster | Population is divided into heterogeneous, often location-based, clusters [4]. | Random selection of entire clusters; all units within chosen clusters are measured. | Large, geographically dispersed populations (e.g., selecting specific wetlands or watersheds for intensive study) for cost efficiency [4] [5]. |

| Non-Probability Sampling | Selection is non-random, based on convenience or researcher judgement [4]. | Researcher-driven selection of units. | Exploratory, hypothesis-generating studies, or when the population is poorly defined or inaccessible [4]. |

| Convenience | Ease of access dictates selection [4]. | Sampling the most readily available units. | Preliminary, scoping studies to gain initial insights (e.g., roadside sampling for air quality). High risk of bias [4] [5]. |

| Judgmental (Purposive) | Researcher's expertise guides selection of information-rich cases [4]. | Deliberate choice of specific units based on study goals. | Identifying extreme cases or typical cases for in-depth analysis (e.g., selecting a known contaminated hotspot) [4]. |

| Snowball | Existing subjects recruit future subjects from their acquaintances [4]. | Initial subjects refer others. | Studying hard-to-reach or hidden populations (e.g., users of illegal waste disposal practices). Rarely used in environmental science [5]. |

Figure 1: A hierarchical classification of fundamental sampling methods, showing the primary division between probability and non-probability approaches.

A Systematic Framework for Identifying Knowledge Gaps

Identifying knowledge gaps is a methodical process that involves auditing existing research against established methodological standards and emergent environmental challenges.

Gap Analysis in Methodological Approaches

Step 1: Critical Review of Existing Protocols Begin with a comprehensive literature review focused specifically on the sampling, treatment, and analysis methods used in your domain. For instance, a 2025 critical review on Tyre and Road Wear Particles (TRWPs) highlighted that a lack of standardized methods across studies makes comparisons difficult and identified optimal techniques like scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis for particle number and mass determination [3].

Step 2: Evaluate Methodological Alignment with the Research Question Assess whether the sampling designs in published literature are truly fit for purpose. Scrutinize:

- Spatial and Temporal Representativeness: Were samples collected at scales relevant to the ecological process or exposure pathway?

- Technical Feasibility vs. Statistical Rigor: Have studies sacrificed statistical power (e.g., via convenience sampling) for practical ease, and what are the consequences for data quality? [4] [5]

Step 3: Audit for Technological Currency Environmental analytical technology evolves rapidly. A significant knowledge gap exists when older, less sensitive or less specific methods are still in use where newer techniques could provide more accurate or comprehensive data. The review of TRWPs, for example, notes the application of advanced techniques like 2-dimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry for complex samples [3].

The ISM Paradigm: Addressing Past Sampling Limitations

The Incremental Sampling Methodology (ISM) exemplifies how addressing methodological gaps can transform environmental characterization. ISM was developed to overcome the high variability and potential bias of discrete, "grab" sampling for heterogeneous materials like soils and sediments.

Core Principle: ISM involves collecting numerous increments of material from a decision unit (DU) in a systematic, randomized pattern, which are then composited and homogenized to form a single sample that represents the average condition of the DU [6].

Knowledge Gap Addressed: Traditional discrete sampling can miss "hot spots" of contamination or over-represent them, leading to an inaccurate understanding of average concentration and total mass. ISM directly addresses this by ensuring spatial averaging, thus providing a more representative and defensible data set for risk assessment and remediation decisions [6].

Formulating Precise and Actionable Study Objectives

A well-defined study objective is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). In sampling methodology, precision is paramount.

From Gaps to Objectives: A Translational Process

Transform identified gaps into targeted objectives using a structured approach:

Table 2: Translating Knowledge Gaps into Research Objectives

| Identified Knowledge Gap | Resulting Research Objective |

|---|---|

| Lack of standardized sampling protocols for a novel contaminant (e.g., TRWPs) in a specific medium (e.g., urban air). | To develop and validate a standardized protocol for the sampling and extraction of TRWPs from ambient urban air, ensuring reproducibility across different laboratories. |

| Inadequate spatial representativeness of common sampling designs for assessing ecosystem-wide contamination. | To evaluate the effectiveness of stratified random sampling against simple random sampling for estimating mean sediment concentration of [Contaminant X] within a defined estuary. |

| Unknown applicability of a laboratory-optimized analytical method to field-collected, complex environmental samples. | To determine the accuracy and precision of [Specific Analytical Method, e.g., LC-MS/MS] for quantifying [Contaminant Y] in composite soil samples with high organic matter content. |

| Uncertain performance of a new methodology (e.g., ISM) compared to traditional approaches for a specific regulatory outcome. | To compare the decision error rates (e.g., false positives/negatives) associated with ISM versus discrete sampling for determining compliance with soil cleanup standards for metals. |

Incorporating Methodological Specificity

Vague objectives like "study the contamination in the river" are inadequate. Precise objectives explicitly define the what, how, and why of the sampling strategy.

- Poor Objective: "To sample soil for lead in the city park."

- Precise Objective: "To estimate the mean surface soil (0-5 cm depth) lead concentration (in mg/kg, measured via ICP-MS after acid digestion) in the northeastern quadrant of [Park Name] using a systematic grid sampling design (30 samples on a 10m x 10m grid), with the objective of determining if the average concentration exceeds the state residential soil screening level of 400 mg/kg."

The precise objective defines the target population (surface soil in a specific area), the analyte and units (lead in mg/kg), the sampling design (systematic grid), the sample size (30), and the explicit purpose of the study.

Experimental Protocols for Sampling Studies

Workflow for a Stratified Random Sampling Study

The following protocol provides a template for a robust environmental sampling campaign.

Figure 2: A generalized experimental workflow for a stratified random sampling study, from objective definition to data reporting.

Phase 1: Pre-Sampling Planning (Steps 1-3)

- Step 1: Objective Definition: Clearly articulate the primary question the study aims to answer. This determines the target population, the parameters to be measured, and the required data quality [5].

- Step 2: Strata Definition: Divide the population into non-overlapping subgroups (strata) based on a characteristic expected to influence the measured variable (e.g., soil type, land use, water depth). This reduces variability within each stratum and improves estimate precision [4].

- Step 3: Sample Size & Allocation: Determine the total number of samples (

n) needed to achieve a required level of statistical power and confidence. Allocatenacross strata. Common approaches are:- Proportional Allocation: Sample size per stratum is proportional to the stratum's size relative to the total population.

- Optimal Allocation: Allocates more samples to strata that are larger or more variable, maximizing precision [4].

Phase 2: Field and Laboratory Execution (Steps 4-6)

- Step 4: Field Collection: Using a GPS and a randomized location scheme within each stratum, collect individual samples or increments. Document all metadata (date, time, location, weather, field observations) [7].

- Step 5: Sample Handling: Adhere to strict protocols for container type, preservation (e.g., cooling, chemical addition), holding times, and chain-of-custody to ensure sample integrity from field to lab [7] [3].

- Step 6: Laboratory Analysis: Employ analytical methods that have been validated for the specific sample matrix. The EPA's Environmental Sampling and Analytical Methods (ESAM) program provides vetted methods for homeland security-related contamination, which serve as a model for rigorous protocol selection [7].

Phase 3: Data Analysis and Synthesis (Step 7)

- Step 7: Data Analysis: Calculate results for each stratum. The overall population mean is calculated as a weighted average of the stratum means. Report estimates with appropriate confidence intervals to communicate uncertainty [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Environmental Sampling

| Item | Function in Sampling & Analysis |

|---|---|

| Sample Containers | To hold environmental samples without introducing contamination or absorbing analytes. Material (e.g., glass, HDPE, VOC vials) is selected based on analyte compatibility [7]. |

| Chemical Preservatives | Added to samples immediately after collection to stabilize analytes and prevent biological, chemical, or physical changes during transport and storage (e.g., HCl for metals, sodium thiosulfate for residual chlorine) [7]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Materials with a certified concentration of a specific analyte. Used to validate analytical methods and ensure laboratory accuracy by comparing measured values to known values [3]. |

| Internal Standards | Known substances added to samples at a known concentration before analysis. Used in techniques like mass spectrometry to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response [3]. |

| Sampling Equipment | Field-specific apparatus for collecting representative samples (e.g., stainless steel soil corers, Niskin bottles for water, high-volume air samplers). Critical for obtaining the correct sample type and volume [7] [3]. |

The path to robust environmental science is paved with meticulous sampling design. The process of identifying knowledge gaps and setting precise objectives is not a mere preliminary step but the very foundation upon which scientifically defensible and impactful research is built. By critically evaluating existing methodologies through the lens of representativeness and statistical rigor, and by formulating objectives with explicit methodological detail, researchers can ensure their work truly advances our understanding of complex environmental systems. The frameworks, protocols, and tools outlined in this guide provide a concrete pathway for researchers to strengthen this critical phase of the scientific process, thereby enhancing the quality, reliability, and applicability of their findings.

Developing a Conceptual Framework for Variables and Relationships

Within environmental systems research, the development of a robust conceptual framework is a critical prerequisite for effective study design, ensuring that complex, interconnected variables are systematically identified and their relationships clearly defined. This process transforms abstract research questions into structured, empirically testable models. The Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF), pioneered by Elinor Ostrom, provides a seminal example of such a tool, designed specifically for diagnosing systems where ecological and social elements are deeply intertwined [8]. In the context of environmental sampling, a well-constructed conceptual framework directly informs sampling methodology by pinpointing what to measure, where, and when, thereby ensuring that collected data is relevant for analyzing the system's behavior and outcomes [7] [8]. This guide synthesizes current methodological approaches to provide researchers with a structured process for building and applying their own conceptual frameworks.

Theoretical Foundation: The Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF)

The SESF was developed to conduct institutional analyses of natural resource systems and to diagnose collective action challenges. Its core utility lies in providing a common, decomposable vocabulary of variables situated around an "action situation"—where actors interact and make decisions—allowing researchers to structure diagnostic inquiry and compare findings across diverse cases [8]. The framework is organized into nested tiers of components. The first-tier components encompass broad social, ecological, and external factors, along with their interactions and outcomes. Each of these is further decomposed into more specific second-tier variables, creating a structured yet flexible system for analysis [8].

A key strength of the SESF is its dual purpose: it facilitates a deep understanding of fine-scale, contextual factors influencing outcomes in a specific case while also providing a general vocabulary to identify common patterns and build theory across different studies [8]. However, scholars note a significant challenge: the SESF itself is a conceptual organization of variables, not a methodology. It identifies potential factors of interest but does not prescribe how to measure them or analyze their relationships, leading to highly heterogeneous applications that can hinder cross-study comparability [8].

A Methodological Guide for Framework Application

Applying a conceptual framework like the SESF involves a sequence of critical methodological decisions. The following steps provide a guide for researchers to transparently navigate this process, from initial variable definition to final data analysis.

Step 1: Variable Selection and Definition

The first step involves selecting and conceptually defining the framework variables relevant to the specific research context and question. The SESF provides a comprehensive list of potential first and second-tier variables (e.g., Resource System, Governance System, Actors, Resource Units) as a starting point [8]. The researcher must then determine which of these variables are pertinent to their study and provide a clear, operational definition for each.

- Methodological Gap: This step addresses the variable definition gap, where abstract framework concepts must be translated into concrete, case-specific definitions [8].

- Consideration: Ambiguity in this step can lead to a lack of transparency and make it difficult to compare how the same variable is conceptualized across different studies.

Step 2: Variable-to-Indicator Linking

Once variables are defined, they must be linked to observable and measurable indicators. An indicator is a concrete measure that serves as a proxy for a more abstract variable.

- Methodological Gap: This step bridges the variable to indicator gap [8]. For example, the variable "History of Use" within a Resource System could be indicated by "number of years the resource has been harvested" or "historical harvest levels."

- Best Practice: Selecting multiple indicators for a single variable can provide a more robust and nuanced measurement.

Step 3: Measurement and Data Collection

This step involves determining how to collect empirical or secondary data for the identified indicators. The chosen methods must be documented in detail, as this is a common source of heterogeneity in framework applications [8].

- Application in Environmental Sampling: The U.S. EPA's Environmental Sampling and Analytical Methods (ESAM) program exemplifies this phase. It provides standardized sampling strategies and analytical methods for characterizing contaminated sites, which can be directly employed to gather data for specific indicators [7]. For instance, an indicator for "water quality" would require a specific sampling protocol (e.g., sample collection, preservation, handling) and an approved analytical method to detect contaminants.

Step 4: Data Transformation and Analysis

The collected data often requires transformation (e.g., normalization, indexing, aggregation) before it can be analyzed to test hypotheses about variable relationships [8].

- Methodological Gap: This is the data transformation gap [8]. Decisions made here, such as how to combine multiple indicators into a single index for a variable, must be clearly documented to ensure reproducibility.

- Analysis: The final stage involves using statistical or other analytical techniques to explore the relationships between variables, thereby testing the propositions of the conceptual framework. Reproducible criteria for measurement are crucial for quantitative studies aiming for generalizability [8].

Table 1: Methodological Gaps and Strategies in Framework Application

| Methodological Step | Description of the Gap | Recommended Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Variable Definition | Lack of clarity in how abstract framework variables are defined for a specific case [8]. | Provide explicit, operational definitions for each selected variable in the study context. |

| Variable to Indicator | The challenge of linking conceptual variables to observable and measurable indicators [8]. | Identify multiple concrete indicators for each variable to enhance measurement validity. |

| Measurement | Heterogeneity in data collection procedures for the same indicators [8]. | Use standardized protocols where available (e.g., EPA ESAM [7]) and document all procedures. |

| Data Transformation | Lack of transparency in how raw data is cleaned, normalized, or aggregated for analysis [8]. | Explicitly state all data processing rules and the rationale for aggregation methods. |

Visualizing the Framework and Workflow

Visualizing the structure of a conceptual framework and its associated research workflow is essential for communication and clarity. The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, adhere to a specified color palette and contrast rules to ensure accessibility. The fontcolor is explicitly set to #202124 (a near-black) for high contrast against all light-colored node backgrounds, while arrow colors are chosen from the palette for clear visibility.

Core Structure of a Social-Ecological System

This diagram outlines the core first-tier components of the SESF and their primary interrelationships, centering on the "Action Situation."

Methodological Workflow for Framework Application

This workflow diagram maps the step-by-step methodological process for applying a conceptual framework, from study design to synthesis, highlighting the key decisions at each stage.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The practical application of a conceptual framework in environmental research relies on a suite of methodological "reagents" and tools. These standardized protocols and resources ensure the quality, consistency, and interpretability of the data used to populate the framework's variables.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for Environmental Systems Research

| Tool or Resource | Function in Framework Application | Example/Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Sampling Protocols | Provides field methods for collecting environmental samples that yield consistent and comparable data for indicators [7]. | U.S. EPA ESAM Sample Collection Procedures [7]. |

| Validated Analytical Methods | Offers laboratory techniques for quantifying specific contaminants or properties in environmental samples, populating the data for framework variables [7]. | U.S. EPA Selected Analytical Methods (SAM) [7]. |

| Data Quality Assessment Tools | Resources for developing plans to ensure that the collected data is of sufficient quality to support robust analysis and conclusions [7]. | EPA Data Quality and Planning resources [7]. |

| Contrast Color Function | A computational tool for ensuring visual accessibility in data presentation and framework visualizations by automatically generating contrasting text colors [9]. | CSS contrast-color() function (returns white or black) [9]. |

| Contrast Ratio Calculator | A utility to quantitatively check the accessibility of color pairs used in diagrams and data visualizations against WCAG standards [10]. | Online checkers (e.g., Snook.ca) [10]. |

Developing and applying a conceptual framework is an iterative and transparent process of making key methodological decisions. By systematically navigating the steps of variable definition, indicator selection, measurement, and data transformation, researchers can construct a rigorous foundation for their inquiry into complex environmental systems. The use of standardized methodological tools, such as those provided by the EPA ESAM program, enhances the reliability and comparability of findings. Furthermore, the clear visualization of both the framework's structure and the research workflow is indispensable for communicating the study's design and logic. Adhering to a structured guide, as outlined in this document, empowers researchers to not only diagnose specific systems but also to contribute to the broader, synthetic goal of building cumulative knowledge in environmental research.

In environmental systems research, the population of interest—whether it be a body of water, a soil field, or a regional atmosphere—is often too vast, heterogeneous, or dynamic to be studied in its entirety. A population is defined as the entire group about which you want to draw conclusions, while a sample is the specific subset of individuals from which you will actually collect data [4]. Sampling is the structured process of selecting this representative subset to make inferences about the whole population, and it is warranted when direct measurement of the entire system is practically or economically impossible [11].

The decision to sample is foundational to the validity of research outcomes. Without a representative sample, findings are susceptible to various research biases, particularly sampling bias, which can compromise the validity of conclusions and their applicability to the target population [4]. This guide outlines the key indications for undertaking sampling in environmental research, providing a framework for researchers to make scientifically defensible decisions.

Key Scenarios Warranting a Sampling Approach

Sampling becomes a necessary and warranted activity in several core scenarios encountered in environmental and clinical research. The following table summarizes the primary indications.

Table 1: Key Indications Warranting a Sampling Approach

| Indication | Description | Common Contexts |

|---|---|---|

| Large Population Size | The target population is too large for a full census to be feasible or practical [4] [12]. | Regional soil contamination studies, watershed quality assessments, atmospheric monitoring. |

| Spatial or Temporal Heterogeneity | The system exhibits variability across different locations or over time, requiring characterization of this variance [11]. | Mapping pollutant plumes, monitoring seasonal changes in water quality, tracking air pollution diurnal patterns. |

| Inaccessible or Hard-to-Locate Populations | The population cannot be fully accessed or located, making a complete enumeration impossible [12]. | Studies on rare or endangered species, homeless populations for public health, clandestine environmental discharge points. |

| Destructive or Hazardous Analysis | The measurement process consumes, destroys, or alters the sample, or involves hazardous environments [11]. | Analysis of contaminated soil or biota, testing of explosive atmospheres, quality control of consumable products. |

| Cost and Resource Constraints | Budget, time, and personnel limitations prevent the study of the entire population [4] [11]. | Nearly all research projects, particularly large-scale environmental monitoring and resource-intensive clinical trials. |

| Focused Research Objective | The study aims to investigate a specific hypothesis within a larger system, not to create a complete population inventory [13]. | Research on the effect of a specific heavy metal on aquatic biota [11], or a clinical trial for a new drug on a specific patient group [12]. |

Foundational Sampling Methodologies

When sampling is warranted, the choice of methodology is critical. The two primary categories are probability and non-probability sampling, each with distinct strategies suited to different research goals.

Probability Sampling Methods

Probability sampling involves random selection, giving every member of the population a known, non-zero chance of being selected. This is the preferred choice for quantitative research aiming to produce statistically generalizable results [4] [12].

Table 2: Probability Sampling Methods for Environmental and Clinical Research

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Random Sampling | Every member of the population has an equal chance of selection, typically using random number generators [4] [12]. | Minimizes selection bias; simple to understand. | Homogeneous populations where a complete sampling frame is available. |

| Stratified Random Sampling | The population is divided into homogeneous subgroups (strata), and a random sample is drawn from each stratum [4] [12]. | Ensures representation of all key subgroups; improves precision of estimates. | Populations with known, important subdivisions (e.g., by soil type, income bracket, disease subtype). |

| Systematic Sampling | Selecting samples at a fixed interval (e.g., every kth unit) from a random starting point [4] [12]. | Easier to implement than simple random sampling; even coverage of population. | When a sampling frame is available and there is no hidden periodic pattern in the data. |

| Cluster Sampling | The population is divided into clusters (often by geography), a random sample of clusters is selected, and all or a subset of individuals within chosen clusters are sampled [4] [12]. | Cost-effective for large, geographically dispersed populations; practical when a full sampling frame is unavailable. | National health surveys, large-scale environmental studies like regional air or water quality monitoring. |

Non-Probability Sampling Methods

Non-probability sampling involves non-random selection based on convenience or the researcher's judgment. It is more susceptible to bias but is often used in qualitative or exploratory research where statistical generalizability is not the primary goal [4] [12].

Table 3: Non-Probability Sampling Methods for Exploratory Research

| Method | Procedure | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convenience Sampling | Selecting individuals who are most easily accessible to the researcher [4] [12]. | High risk of sampling and selection bias; results not generalizable. | Preliminary, exploratory research; pilot studies to test protocols. |

| Purposive (Judgmental) Sampling | Researcher uses expertise to select participants most useful to the study's goals [4] [12]. | Prone to observer bias; relies heavily on researcher's judgment. | Small, specific populations; qualitative research; expert elicitation studies. |

| Snowball Sampling | Existing study participants recruit future subjects from their acquaintances [4] [12]. | Not representative; relies on social networks. | Hard-to-access or hidden populations (e.g., specific community groups, illicit discharge actors). |

| Quota Sampling | The population is divided into strata and a non-random sample is collected until a preset quota for each stratum is filled [4]. | While it ensures diversity, it is still non-random and subject to selection bias. | When researchers need to ensure certain subgroups are included but cannot perform random sampling. |

Developing a Sampling Plan: A Structured Workflow

A successful environmental study requires a rigorous 'plan of action' known as a sampling plan [11]. The diagram below outlines the critical stages and decision points in this developmental workflow.

Critical Factors in Sampling Strategy

When answering the essential questions of where, when, and how many samples to collect, several factors must be considered [11]:

- Study Objectives: The strategy must align with the core research question. Monitoring total effluent load requires a 24-hour integrated sample, while detecting accidental releases demands near-continuous sampling.

- Environmental Variability: High spatial or temporal variability necessitates a larger number of samples. Pollutant levels in air, for instance, can vary significantly with meteorological conditions or traffic patterns.

- Resource Constraints: A cost-effective plan must be designed within the available budget, time, and personnel, balancing the need for statistical precision with practical limitations.

- Regulatory Requirements: Many monitoring programs must adhere to specific regulatory standards that dictate sampling frequency, location, and methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Environmental Sampling

The specific reagents and materials required depend on the analyte and environmental medium. The following table details key items commonly used in field sampling campaigns.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Environmental Sampling

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Containers (e.g., Vials, Bottles) | To hold and transport the collected sample without introducing contamination. | Water sampling (glass vials for VOCs), soil sampling (wide-mouth jars). |

| Chemical Preservatives | To stabilize the sample by halting biological or chemical degradation until analysis. | Adding acid to water samples to preserve metals; cooling samples to slow microbial activity [11]. |

| Sampling Equipment (e.g., Bailers, Pumps, Corers) | Device-specific tools for collecting the environmental medium from the source. | Groundwater well sampling (bailers); surface water sampling (Kemmerer bottles); soil sampling (corers). |

| Field Measurement Kits (e.g., for pH, Conductivity) | To measure unstable parameters that must be determined immediately in the field. | Measuring pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen in surface water on-site. |

| Chain-of-Custody Forms | Legal documents that track sample handling from collection to analysis, ensuring data integrity. | All sampling where data may be used for regulatory or legal purposes. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | To protect field personnel from physical, chemical, and biological hazards during sampling. | Handling contaminated soil or water (gloves, safety glasses, coveralls). |

The decision to employ sampling is a cornerstone of rigorous environmental and clinical research. It is warranted when confronting large populations, significant heterogeneity, inaccessible subjects, destructive analyses, and resource constraints. The choice between probability methods—which support statistical inference to the broader population—and non-probability methods—suited for exploratory studies—must be guided by the research objectives. Ultimately, the validity of any research finding hinges on a carefully considered sampling plan that ensures the collected data is both representative of the target population and fit for the intended purpose.

Establishing Protocols for Sample Collection and Culturing

In environmental systems research, the collection and culturing of samples are foundational activities that generate the critical data upon which scientific and regulatory decisions are based. The fundamental goal of any sampling protocol is to obtain information that is representative of the environment being studied while optimizing resources and manpower [14]. This process is governed by the need for rigorous, predefined strategies to ensure data quality, integrity, and actionability. Within a broader thesis on sampling methodology, this guide details the establishment of robust, defensible protocols for sample collection and culturing, with particular emphasis on scenarios relevant to contamination response, microbial ecology, and public health.

The necessity for precise protocols is underscored by the high costs and complexity of environmental sampling, a process influenced by numerous variables in protocol, analysis, and interpretation [15]. A well-defined protocol translates project objectives into concrete sampling and measurement performance specifications, ensuring that the information collected is fit for its intended purpose [16]. This guide synthesizes principles from authoritative sources, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to provide a comprehensive technical framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Foundational Principles and Sampling Design

Core Principles for Microbiologic Sampling

Before designing a sampling campaign, understanding core principles is essential. Historically, routine environmental culturing was common practice, but it has been largely discontinued because general microbial contamination levels have not been correlated with health outcomes, and no permissible standards for general contamination exist [15]. Modern practice therefore advocates for targeted sampling for defined purposes, which is distinct from random, undirected "routine" sampling.

A targeted microbiologic sampling program is characterized by three key components:

- A written, defined, multidisciplinary protocol for sample collection and culturing.

- Analysis and interpretation of results using scientifically determined or anticipatory baseline values for comparison.

- Expected actions based on the results obtained [15].

Selecting a Sampling Design

The choice of sampling design is dictated by the specific objectives of the study and the existing knowledge of the site. The EPA outlines several sampling designs, each with distinct advantages for particular scenarios [17]. Selecting the appropriate design is the first critical step in ensuring data representativeness.

Table 1: Environmental Sampling Design Selection Guide

| If your objective is... | Recommended Sampling Design(s) |

|---|---|

| Emergency situations or small-scale screening | Judgmental Sampling |

| Identifying areas of contamination or searching for rare "hot spots" | Adaptive Cluster Sampling, Systematic/Grid Sampling |

| Estimating the mean or proportion of a parameter | Simple Random Sampling, Systematic/Grid Sampling, Stratified Sampling |

| Comparing parameters between two areas | Simple Random Sampling, Ranked Set Sampling, Stratified Sampling |

| Maximizing coverage with minimal analytical costs | Composite Sampling (in conjunction with other designs) |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for selecting an appropriate sampling design based on project objectives and site conditions:

Sampling Design Selection Workflow guides users through a decision tree based on project goals and site knowledge to choose the most effective EPA-recommended sampling design.

Indications for Environmental Sampling

Given the resource-intensive nature of the process, environmental sampling is only indicated in specific situations [15]:

- Outbreak Investigations: To support an investigation when environmental reservoirs are implicated epidemiologically in disease transmission. Culturing must be supported by epidemiologic data, and there must be a plan for interpreting and acting on the results.

- Research: Well-designed and controlled studies can provide new information about the spread of healthcare-associated diseases.

- Monitoring Hazardous Conditions: To confirm the presence of a hazardous chemical or biological agent (e.g., bioterrorism agent, bioaerosols from equipment) and validate its successful abatement.

- Quality Assurance (QA): To evaluate the effects of a change in infection-control practice or to ensure equipment performs to specification. The CDC notes that extended QA sampling is generally unjustified without an adverse outcome.

Pre-Sampling Planning and Data Quality Objectives

Successful sampling campaigns are built upon meticulous pre-sampling planning. This phase translates the project's scientific questions into a concrete, actionable plan.

The Sampling and Analysis Plan (SAP)

A formal Sampling and Analysis Plan (SAP) is a critical document that ensures reliable decision-making. A well-constructed SAP addresses several key components [16]:

- Purpose and Objectives: A clear statement of the project's goals.

- Quality Objectives and Criteria: Definition of data quality objectives.

- Sampling Process Design: The specific sampling designs to be employed.

- Sampling Methods: Detailed, step-by-step procedures for sample collection.

- Sample Handling and Traceability: Protocols for preservation, custody, and transport.

- Analytical Method Requirements: Specification of the laboratory methods to be used.

- Quality Control Requirements: The QC samples and checks to be implemented.

Establishing Data Quality Objectives (DQOs)

The Data Quality Objectives process formalizes the criteria for data quality. These are often summarized by the PARCCS criteria [16]:

- Precision: The degree of mutual agreement among individual measurements.

- Accuracy: The degree of bias of a measurement compared to the true value.

- Representativeness: The degree to which data accurately depict the true environmental condition.

- Completeness: The proportion of valid data obtained from the total planned.

- Comparability: The confidence with which data from different studies can be compared.

- Sensitivity: The lowest level at which an analyte can be reliably detected.

Sample Collection Methodologies and Procedures

Generalized Sample Collection Workflow

The sample collection process, from planning to shipment, follows a logical sequence to maintain integrity and traceability. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow applicable to various environmental sampling contexts:

Sample Collection and Handling Workflow depicts the sequential stages of a sampling campaign, from initial planning through to laboratory transport, highlighting key actions at each step.

Sample Collection Information Documents (SCIDs)

The EPA promotes the use of Sample Collection Information Documents (SCIDs) as quick-reference guides for planning and collection [14]. SCIDs provide essential information to ensure the correct supplies are available at the contaminated site. Key information typically includes:

- Container Type: Specific bottles, vials, or bags required.

- Sample Volume/Weight: The minimum required amount for analysis.

- Preservation Chemicals: e.g., hydrochloric acid for metals, sodium thiosulfate for disinfectant neutralization.

- Holding Times: The maximum time a sample can be held before analysis.

- Packaging Requirements: Specific instructions for shipping to maintain sample integrity.

Analytical Methods, Culturing, and Data Management

Cultural and Molecular Analytical Approaches

The analytical phase involves the processing and interpretation of samples. In microbiological contexts, this typically involves either cultural methods or molecular approaches [18]. Cultural methods involve growing microorganisms on selective media to isolate and identify pathogens or indicator organisms. Molecular methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), detect genetic material and can provide faster results and linkage of environmental isolates to clinical strains during outbreak investigations [15].

The Three-Step Approach for Environmental Monitoring Programs (EMPs)

For structured application, a common three-step approach is recommended for building efficient Environmental Monitoring Programs (EMPs) in various industries [18]:

- Pre-analytical Step: Design the strategy for the EMP, considering the hazards and risks associated with the product and environment. This includes defining zones, sampling sites, frequencies, and target organisms.

- Analytical Step: Execute the sampling stages using cultural or molecular approaches, followed by laboratory analysis.

- Post-analytical Step: Manage the collected data, interpret results against pre-established baselines or limits, and implement corrective actions. EMPs are dynamic and must be updated regularly to remain fit-for-purpose [18].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for executing environmental sample collection and culturing protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Sampling and Culturing

| Item/Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Sample Containers | Pre-cleaned, sterile vials, bottles, or bags; specific container type (e.g., glass, plastic) is mandated by the analyte and method to prevent adsorption or contamination [14]. |

| Preservation Chemicals | Chemicals (e.g., acid, base, sodium thiosulfate) added to samples immediately after collection to stabilize the analyte and prevent biological, chemical, or physical changes before analysis [14]. |

| Culture Media | Selective and non-selective agars and broths used to grow and isolate specific microorganisms from environmental samples (e.g., for outbreak investigation or research) [15]. |

| Sterile Swabs & Wipes | Used for surface sampling to physically remove and collect microorganisms from defined areas for subsequent culture or molecular analysis. |

| Air Sampling Equipment | Impingers, impactors, and filtration units designed to collect airborne microorganisms (bioaerosols) for concentration determination and identification [15]. |

| Chain of Custody Forms | Legal documents that track the possession, handling, and transfer of samples from the moment of collection through analysis, ensuring data defensibility [16]. |

| Biological Spores | Used for biological monitoring of sterilization processes (e.g., autoclaves) as a routine quality-assurance measure in laboratory and clinical settings [15]. |

Establishing robust protocols for sample collection and culturing is a multidisciplinary endeavor that demands rigorous planning, execution, and adaptation. By adhering to structured frameworks—such as developing a detailed SAP, selecting a statistically sound sampling design, utilizing tools like SCIDs, and following a clear pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical workflow—researchers can ensure the data generated is of known and sufficient quality to support critical decisions in environmental systems research, public health protection, and drug development. As the CDC emphasizes, sampling should not be conducted without a plan for interpreting and acting on the results; the ultimate value of any protocol lies in its ability to produce actionable, scientifically defensible information.

From Theory to Field: A Practical Guide to Environmental Sampling Methods

In environmental systems research, the immense scale and heterogeneity of natural systems—from vast watersheds to complex atmospheric layers—make measuring every individual element impossible. Sampling methodology provides the foundational framework for selecting a representative subset of these environmental systems, enabling researchers to draw statistically valid inferences about the whole population or area of interest [11]. The core challenge lies in designing a sampling plan that accurately captures both spatial and temporal variability while working within practical constraints of cost, time, and resources [11].

Environmental domains are typically highly heterogeneous, exhibiting significant variations across both space and time. A sampling approach must therefore be scientifically designed to account for this inherent variability [11]. The fundamental purpose of employing structured sampling designs is to collect data that can support major decisions regarding environmental protection, resource management, and public health, with the understanding that all subsequent analyses depend entirely on the initial sample's representativeness [11]. Within this context, three core probability sampling designs—random, systematic, and stratified—form the essential toolkit for researchers seeking to generate statistically significant information about environmental systems.

Foundational Concepts and Terminology

Key Definitions in Sampling Theory

- Sampling Design: A set of rules for selecting units from a population and using the resulting data to generate statistically valid estimates for parameters of interest [19].

- Population: The entire collection of items, individuals, or areas about which researchers seek to draw conclusions. In environmental contexts, this could encompass an entire forest, watershed, or airshed [11].

- Sampling Unit: A discrete, selectable component of the population. This might be a specific volume of water, quantity of soil, or area of land [20].

- Sampling Frame: The list of all sampling units from which the sample is actually selected [19].

- Bias: The systematic introduction of error into a study through non-representative sample selection [11].

- Precision: The measure of how close repeated measurements are to each other, often related to sample size and design efficiency [20].

The Sampling Plan Development Process

Developing a robust sampling plan requires methodical preparation and clear objectives. The US Environmental Protection Agency emphasizes that the essential questions in any sampling strategy are where to collect samples, when to collect them, and how many samples to collect [11]. The major steps in developing a successful environmental study include:

- Clearly outline the goal: Define the hypothesis to be tested and what data should be generated to obtain statistically significant information [11].

- Identify the environmental population: Determine the spatial and temporal boundaries of the system under investigation [11].

- Research site history and physical environment: Gather background information about weather patterns, land use history, and potential contamination sources [11].

- Conduct literature search: Examine data from similar studies to understand trends and variability [11].

- Identify measurement procedures: Select analytical methods that influence how samples are collected and handled [11].

- Develop field sampling design: Determine the number of samples, frequency, and spatial/temporal coverage [11].

- Implement quality assurance: Develop documentation procedures for sampling, analysis, and contamination control [11].

Core Sampling Designs: Principles and Procedures

Simple Random Sampling

Principles and Applications

Simple random sampling (SRS) represents the purest form of probability sampling, where every possible sampling unit within the defined population has an equal chance of being selected [21]. This approach uses random number generators or equivalent processes to select all sampling locations without any systematic pattern or stratification [17]. The EPA identifies SRS as appropriate for estimating or testing means, comparing means, estimating proportions, and delineating boundaries, though it notes this design is "one of the least efficient (though easiest) designs since it doesn't use any prior information or professional knowledge" [17].

According to the EPA guidance, simple random sampling is particularly suitable when: (1) the area or process to sample is relatively homogeneous with no major patterns of contamination or "hot spots" expected; (2) there is little to no prior information or professional judgment available; (3) there is a need to protect against any type of selection bias; or (4) it is not possible to do more than the simplest computations on the resulting data [17]. For environmental systems, this makes SRS particularly valuable in preliminary studies of relatively uniform environments where prior knowledge is limited.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Simple Random Sampling

Materials Required:

- GPS device or detailed maps with coordinate systems

- Random number generator (hardware or software)

- Field equipment appropriate for the medium (soil corers, water samplers, etc.)

- Sample containers and preservation materials

- Data logging equipment

Procedure:

- Define the sampling universe: Precisely delineate the geographical boundaries of the study area using GIS tools or precise mapping [19].

- Establish coordinate system: Set up a two-dimensional coordinate system (x, y) that covers the entire study area, with units appropriate to the scale (meters, kilometers, etc.) [19].

- Generate random coordinates: Using a random number generator, create pairs of coordinates within the defined sampling universe. The number of coordinate pairs should equal the desired sample size determined through statistical power analysis [11].

- Field localization: Navigate to each coordinate point in the field using GPS technology with appropriate precision for the study scale [19].

- Sample collection: Collect samples using standardized procedures to maintain consistency across all sampling points [11].

- Documentation: Record precise location, time, environmental conditions, and any observations that might contextualize the sample [11].

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of Simple Random Sampling

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Minimal advance knowledge of population required | Can be inefficient for heterogeneous populations |

| Straightforward statistical analysis | Potentially high costs for widely distributed points |

| Unbiased if properly implemented | May miss rare features or small-scale variations |

| Easy to implement and explain | Requires complete sampling frame |

Systematic Sampling

Principles and Applications

Systematic sampling (SYS) involves selecting sampling locations according to a fixed pattern across the population, typically beginning from a randomly chosen starting point [19]. In this design, sampling locations are arranged in a regular pattern (such as a rectangular grid) across the study area, with the initial grid position randomly determined to introduce the necessary randomization element [19]. This approach is widely used in forest inventory and environmental mapping due to its practical implementation advantages [19].

The EPA identifies systematic (or grid) sampling as appropriate for virtually any objective—"estimating means/testing, proportions, etc.; delineating boundaries; finding hot spots; and estimating spatial or temporal patterns or correlations" [17]. Systematic designs are particularly valuable for pilot studies, scoping studies, and exploratory studies where comprehensive spatial coverage is desirable [17].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Systematic Grid Sampling

Materials Required:

- GIS software with spatial analysis capabilities

- GPS device with adequate precision

- Navigation tools for transect lines

- Standardized sampling equipment

- Data recording forms or digital collection tools

Procedure:

- Determine sample size: Calculate the required number of sampling points based on statistical power requirements or established protocols for the environmental medium [19].

- Calculate grid spacing: For a study area of total area A with sample size n, the spacing for a square grid is calculated as Dsq = √(cA/n), where c is a conversion factor to express area in square distance units [19].

- Establish random start: Select a random point within the study area to serve as the initial grid point or anchor [19].

- Orient the grid: Determine grid orientation based on logistical considerations (ease of navigation) or to capture known environmental gradients [19].

- Generate sampling grid: Create the full grid of sampling points extending from the random start point across the entire study area [19].

- Field implementation: Navigate to each grid point using GPS and standardized navigation procedures [19].

- Sample collection: Collect samples using consistent methods at each point, documenting any deviations from the planned locations [19].

Table 2: Systematic Sampling Design Considerations

| Consideration | Implementation Guidance |

|---|---|

| Grid pattern | Typically square or rectangular; rectangular grids define different spacing along (Dp) and between (Dl) lines |

| Grid orientation | Adjust to improve field logistics or to capture environmental gradients perpendicular to sampling lines |

| Sample size adjustment | If calculated sample size doesn't match grid points exactly, use all points generated or specify a denser grid and systematically thin points |

| Periodic populations | Rotate grid to avoid alignment with periodic features (e.g., plantation rows) that could introduce bias |

Figure 1: Systematic Sampling Implementation Workflow

Stratified Sampling

Principles and Applications

Stratified random sampling utilizes prior information about the study area to create homogeneous subgroups (strata) that are sampled independently using random processes within each stratum [17]. These strata are typically based on spatial or temporal proximity, preexisting information, or professional judgment about factors that influence the variables of interest [17]. The key principle is that dividing a heterogeneous population into more homogeneous subgroups can improve statistical efficiency and ensure adequate representation of important subpopulations.