Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metal Removal: A Comparative Review of Efficiency, Mechanisms, and Applications

This article provides a systematic analysis of nanomagnetic chitosan composites, a leading adsorbent class for heavy metal remediation in wastewater.

Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metal Removal: A Comparative Review of Efficiency, Mechanisms, and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of nanomagnetic chitosan composites, a leading adsorbent class for heavy metal remediation in wastewater. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational principles, synthesis methodologies, and adsorption mechanisms underpinning their high performance. The content critically evaluates and compares the removal efficiencies of various composite formulations for priority metals like Pb(II), Cr(VI), Cu(II), and Cd(II). Furthermore, it addresses key optimization challenges, regeneration potential, and validation strategies, offering a comprehensive resource for developing advanced, application-ready water purification technologies.

The Science Behind the Sorbent: Unpacking Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

Heavy Metals: A Persistent Threat to Ecosystems and Health

Heavy metals are naturally occurring elements in the Earth's crust, but human activities have significantly increased their environmental concentrations, making them persistent and hazardous pollutants [1]. Unlike organic pollutants, heavy metals are non-biodegradable, enabling them to accumulate in the environment and biomagnify through the food chain, ultimately posing severe risks to human health and ecosystems [2] [3] [4].

The toxicity of heavy metals stems from their ability to interfere with essential biological functions. Primary mechanisms include the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress that can cause DNA damage, protein modification, and lipid peroxidation [2]. Furthermore, heavy metals can deplete antioxidants like glutathione and bind to sulfhydryl groups of proteins, disrupting enzyme activity [2] [1]. Some metals, such as lead and cadmium, exert toxicity by displacing essential metals like calcium and zinc from their native binding sites in proteins, causing cellular dysfunction [1]. Chronic exposure to heavy metals is linked to neurological disorders, organ damage, and an increased risk of cancer, highlighting the critical need for their effective removal from water and soil [3] [1].

Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites: A Synergistic Solution

A particularly advanced and promising approach for heavy metal removal involves the use of nanomagnetic chitosan composites. These materials synergistically combine the advantageous properties of two components:

- Chitosan: A natural, biodegradable, and non-toxic biopolymer derived from chitin. Its molecular structure features abundant amino (

-NH₂) and hydroxyl (-OH) functional groups, which act as effective coordination and adsorption sites for heavy metal ions [5] [6]. - Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., Magnetite/ Maghemite): These components provide the composite with magnetic susceptibility, allowing for the easy and rapid separation of the spent adsorbent from treated water using an external magnetic field, thereby overcoming challenges associated with filtration or centrifugation [5] [6] [7].

The composite's versatility allows for modifications that enhance its stability, surface area, and adsorption capacity for various heavy metal ions, making it a subject of intense research within the scientific community [4].

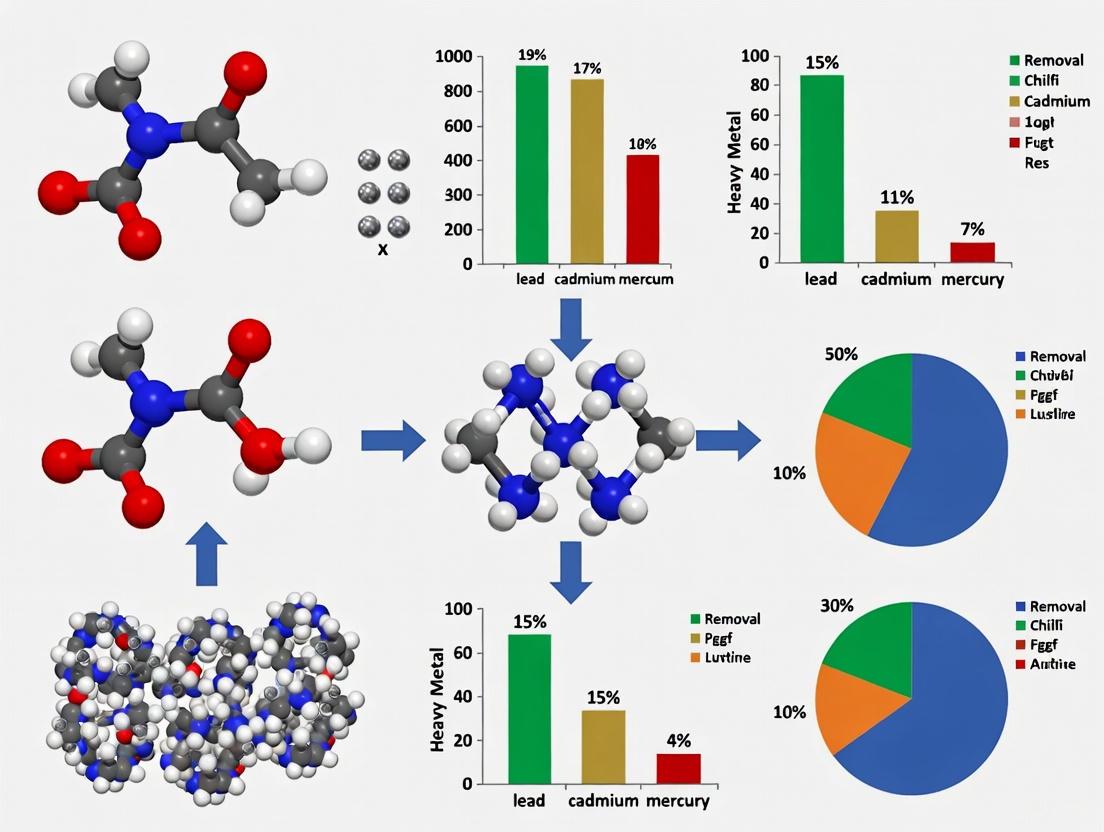

Comparative Removal Efficiency of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

The performance of adsorbents is typically evaluated based on their adsorption capacity, measured in milligrams of metal adsorbed per gram of adsorbent (mg/g). The table below summarizes the reported maximum uptake capacities of different magnetic chitosan-based composites for various heavy metals, providing a direct comparison of their efficiency.

Table 1: Adsorption Capacity of Magnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metals

| Composite Name | Target Heavy Metal | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Key Functional Groups | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) | Pb(II) | 220.9 mg/g | Amino, Hydroxyl | [5] [6] |

| Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) | Cu(II) | 216.8 mg/g | Amino, Hydroxyl | [5] [6] |

| Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) | Ni(II) | 108.9 mg/g | Amino, Hydroxyl | [5] [6] |

| Chitosan-coated MNPs (CMNP) | Pb(II) | ~100% removal efficacy | Amino, Hydroxyl | [7] |

The data demonstrates that magnetic chitosan composites exhibit high affinity for prevalent toxic metals like lead, copper, and nickel. The variation in capacity highlights the material's selectivity, with a particularly high efficiency for lead removal.

Experimental Protocols for Composite Synthesis and Evaluation

To ensure the reproducibility of research in this field, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail common methodologies for synthesizing magnetic chitosan composites and evaluating their adsorption performance.

Synthesis of Chitosan-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles

One efficient method for synthesis is one-step reverse microemulsion precipitation [7].

- Objective: To synthesize chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles (CMNP) in a single step with controlled size and high magnetization.

- Materials: Ferric chloride (FeCl₃), ferrous sulfate (FeSO₄), chitosan (low molecular weight), ammonia solution (precipitating agent), toluene, surfactant (e.g., sodium dodecyl sulfate), and deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a reverse microemulsion by mixing an aqueous phase (containing dissolved chitosan and Fe salts) with a surfactant-toluene mixture. The system is maintained at an elevated temperature (70-80°C) under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Add an ammonia solution to the microemulsion under vigorous stirring to co-precipitate the magnetic nanoparticles within the chitosan matrix.

- The black precipitate (CMNP) is collected using a magnet, washed repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol to remove impurities, and then dried.

- Characterization: The resulting nanoparticles are characterized using X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm crystal structure and crystallite size (often around 4.5 nm), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to verify chitosan coating, and Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM) to measure saturation magnetization (e.g., 49-53 emu/g) [7].

Batch Adsorption Experiment Protocol

Batch adsorption studies are the standard for evaluating metal removal efficiency [5] [6].

- Objective: To determine the adsorption capacity and kinetics of a composite for specific heavy metal ions under controlled conditions.

- Materials: Composite adsorbent, heavy metal salt solution (e.g., Pb(NO₃)₂, CuCl₂), buffer solutions for pH adjustment, orbital shaker, and Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) instrument for metal concentration analysis.

- Procedure:

- A known mass of the composite (e.g., 10-50 mg) is added to a series of flasks containing a fixed volume (e.g., 100 mL) of metal ion solution at a known initial concentration.

- The pH of the solution is adjusted to the optimal value (often between pH 5-7) using dilute NaOH or HNO₃.

- The flasks are agitated in a shaker at a constant speed and temperature until adsorption equilibrium is reached (typically 120-180 minutes). Samples are taken at regular intervals.

- The composite is separated magnetically, and the residual metal concentration in the supernatant is measured using AAS/ICP.

- Data Analysis:

- Adsorption Capacity (qₑ): Calculated as ( qe = \frac{(C0 - Ce)V}{m} ), where ( C0 ) and ( C_e ) are initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), ( V ) is solution volume (L), and ( m ) is adsorbent mass (g).

- Kinetics: Data is fitted to models like the pseudo-first-order or pseudo-second-order model to understand the adsorption rate.

- Isotherms: Data is fitted to models like Langmuir or Freundlich to describe the adsorption equilibrium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Research into nanomagnetic chitosan composites requires a range of specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table lists key materials essential for experiments in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Composite Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (Low MW) | Primary biopolymer matrix providing adsorption sites; its low molecular weight improves processability. | Functional groups (-NH₂, -OH) for metal ion coordination [7]. |

| Ferric Chloride (FeCl₃) | Iron precursor for the synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles (Magnetite/Maghemite). | Fe³⁺ source in co-precipitation reactions [8] [7]. |

| Ferrous Sulfate (FeSO₄) | Iron precursor for the synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles (Magnetite/Maghemite). | Fe²⁺ source in co-precipitation reactions [8] [7]. |

| Ammonia Solution (NH₄OH) | Precipitating agent to form iron oxide nanoparticles from Fe salts. | Creates alkaline conditions for Fe₃O₄ co-precipitation [7]. |

| Lead Nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) | Model heavy metal salt for testing adsorption performance and efficiency. | Preparation of stock solutions for batch experiments [7]. |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) | Analytical instrument for quantifying heavy metal ion concentration in solution. | Measuring residual Pb²⁺ concentration after adsorption [6]. |

| Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) | Characterizes the magnetic properties of the synthesized composite. | Confirming superparamagnetism and saturation magnetization [6] [7]. |

Mechanisms of Metal Adsorption and Composite Regeneration

The high efficiency of nanomagnetic chitosan composites is attributed to their multifaceted adsorption mechanisms. The primary interactions between the composite and heavy metal ions are illustrated below.

A critical advantage of these advanced composites is their potential for regeneration and reuse. After adsorption, the metal-loaded composite can be treated with a mild acidic solution (e.g., 0.1M HNO₃ or EDTA), which desorbs the metal ions from the functional groups. The regenerated composite can then be washed, neutralized, and used in multiple treatment cycles, enhancing its cost-effectiveness and reducing chemical waste [3]. Studies have shown that chitosan microspheres can be regenerated for up to five cycles with consistent performance, underscoring their practical applicability [3].

The pervasive threat of heavy metal contamination in water resources demands the development of efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly remediation technologies. Among various treatment methods, biosorption has emerged as a promising alternative, with chitosan standing out due to its exceptional metal-binding capacities [9]. This natural biopolymer, derived from chitin, offers the dual advantage of sustainability and high performance [10]. The innate affinity of chitosan for metal ions is primarily governed by its unique chemical structure, rich in amino and hydroxyl functional groups [11]. Recent research has focused on enhancing chitosan's properties through the development of nanomagnetic chitosan composites, which combine high sorption efficiency with facile magnetic separation [9] [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of chitosan's role as a biosorbent, examining its sources, structural properties, and the performance of its advanced composites against other common adsorbents, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Source and Production of Chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide produced by the alkaline deacetylation of chitin [10] [13]. Chitin, the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose, is a primary component of the exoskeletons of crustaceans such as shrimp, crabs, and prawns, as well as the cell walls of fungi [10] [13].

The industrial production of chitosan from crustacean shells involves four key steps [10]:

- Demineralization (DM): Removal of inorganic materials (like calcium carbonate) using dilute acid.

- Deproteinization (DP): Removal of proteins using alkaline solutions.

- Decolorization (DC): Removal of pigments.

- Deacetylation (DA): Treatment with concentrated sodium hydroxide to remove acetyl groups from chitin, converting it into chitosan.

The resulting product is a copolymer of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine units [10]. The degree of deacetylation (DD), which typically ranges from 60% to 95%, significantly influences chitosan's properties, including its solubility and number of available free amino groups for metal binding [10].

Structural Characteristics and Innate Metal Affinity

The chemical structure of chitosan is the foundation of its remarkable biosorbent capabilities. Unlike most polysaccharides, chitosan possesses positively charged amino groups in acidic environments, making it a polycationic polymer [10]. This feature is crucial for its interactions with various metal ions.

The primary functional groups responsible for metal chelation are [11] [10]:

- Amino groups (-NH₂): These are the most reactive sites, capable of forming coordination bonds with metal ions.

- Hydroxyl groups (-OH): These can also participate in metal binding, though to a lesser extent than amino groups.

The proposed mechanisms for metal sorption include:

- Chemisorption: Formation of coordination complexes between metal ions and the amino groups, often following pseudo-second-order kinetics [14] [9].

- Electrostatic attraction: Between protonated amino groups (NH₃⁺) and anionic metal species [9].

The following diagram illustrates the chemical structure of chitosan and its metal-binding sites.

Comparative Performance of Chitosan and Alternative Biosorbents

A wide array of materials has been investigated for their metal sorption capabilities. The following table provides a comparative overview of the adsorption capacities of chitosan and other common biosorbents for various heavy metals, based on data from recent scientific literature.

Table 1: Comparative Adsorption Capacities of Chitosan and Alternative Biosorbents for Heavy Metals

| Adsorbent Material | Target Metal Ions | Reported Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (Base Polymer) | Cu²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ [15] | >90% removal efficiency [15] | High innate affinity, biodegradable, renewable [10] | Soluble in strong acids, poor mechanical strength [9] |

| Magnetic Chitosan/CNF-Fe(III) Composite [12] | Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) | Not specified (high removal efficiency) [12] | Magnetic separation, enhanced stability [12] | Multi-step synthesis required |

| TPP-Crosslinked Magnetic Chitosan (TPP-CMN) [13] | Cd(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Pb(II) | 87.25 - 99.96 mg/g [13] | Fast kinetics (15 min), high capacity, reusable [13] | Surface modification needed |

| Vanillin-Modified Magnetic Chitosan (V-CMN) [13] | Cd(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Pb(II) | 88.75 - 99.89 mg/g [13] | High capacity, reusable [13] | Slightly slower kinetics (30 min) than TPP-CMN [13] |

| Chemically Modified Chitosan Coated Sugarcane Bagasse Ash [16] | Pb(II), Cd(II) | ~12 mg/g [16] | Low-cost composite, uses agricultural waste [16] | Lower capacity than advanced composites |

| Bone Char [14] | Cr(VI), Cd(II), Pb(II) | High for Cr(VI) at low pH [14] | Effective for specific ions like Cr(VI) [14] | Performance varies with bone source and pyrolysis conditions [14] |

| Food Wastes (e.g., Rice Husks, Sugarcane Bagasse) [14] | Cr, Pb | Varies by waste type [14] | Very low cost, waste valorization [14] | Inconsistent composition and adsorption efficiency [14] |

Performance of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

The integration of magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) into chitosan matrices has led to a new class of biosorbents that address several limitations of pure chitosan. The table below details the synthesis and performance of different nanomagnetic chitosan composites, highlighting their comparative efficiency.

Table 2: Synthesis and Performance of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

| Composite Name | Synthesis Method & Modification | Key Characteristics | Optimal Adsorption Conditions | Adsorption Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-Ch/CNF-Fe(III) [12] | Blend of chitosan and cellulose nanofiber (1:1) coated with Fe₃O₄ via sol-gel and emulsification [12] | Porous structure, magnetic separation, improved mechanical strength [12] | pH-dependent removal for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) [12] | Effective elimination of multiple metals from aqueous solution [12] |

| TPP-CMN [13] | Chitosan-coated Fe₃O4 crosslinked with sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) [13] | Saturation magnetization: 7.211 emu/g, Surface area: 8.75 m²/g [13] | Fast equilibrium (15 minutes) [13] | Pb(II): 99.96, Co(II): 93.00, Cd(II): 91.75, Cu(II): 87.25 mg/g [13] |

| V-CMN [13] | Chitosan-coated Fe₃O4 modified with vanillin (V) [13] | Saturation magnetization: 7.772 emu/g, Surface area: 6.96 m²/g [13] | Equilibrium in 30 minutes [13] | Pb(II): 99.89, Co(II): 94.00, Cd(II): 92.5, Cu(II): 88.75 mg/g [13] |

The following workflow summarizes the typical journey from conceptualization to application for a magnetic chitosan composite in a research setting.

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Synthesis of Magnetic Chitosan Nanocomposites (CMN)

The synthesis of the core-shell magnetic adsorbent is a foundational protocol [13]:

- Synthesis of Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles: Dissolve anhydrous FeCl₃ and FeSO₄·6H₂O in a 1:1 molar ratio in distilled water. Mix the solutions and stir for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Add a 10% NaOH solution dropwise under constant stirring until pH reaches 12.25. Continue stirring at 1000 rpm for 1 hour at 50°C.

- Hydrothermal Treatment: Transfer the homogeneous black solution to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 120°C for 6 hours. Cool to room temperature, filter the black precipitate, and wash with distilled water and ethanol, then dry at 60°C.

- Chitosan Coating: Add the synthesized Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles to a 3% (w/v) chitosan solution (in acetic acid) in a 1:70 (w/v) ratio. Disperse using ultrasonic vibration for 20 minutes.

- Cross-linking: Add a few drops of formaldehyde as a cross-linker. A black gel forms after 4.5 hours. Dry the product at 60°C, then wash with 2% acetic acid and distilled water, and dry again [13].

Surface Modification with Tripolyphosphate (TPP-CMN)

For enhanced stability and performance, surface modification can be performed [13]:

- Suspend the prepared CMN in a 6% aqueous citric acid solution for 18 hours under magnetic stirring.

- Add a sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution dropwise into the yellowish opaque solution.

- Sonicate the mixture for 15 minutes and then stir for an additional 5 hours.

- Filter the resulting whitish solution to recover the TPP-CMN nano-sorbent [13].

Batch Adsorption Experiment Protocol

A standardized batch equilibrium technique is used to evaluate performance [16] [13]:

- Preparation: Prepare stock solutions (e.g., 1000 mg/L) of target metal ions (Pb(II), Cd(II), Cu(II), Cr(VI), etc.) from their salts.

- Parameter Testing: Agitate a fixed dose of the biosorbent (e.g., 0.05–1.0 g) with a known volume (e.g., 100 mL) of metal ion solution in a shaker incubator.

- Variable Parameters: Systematically vary parameters such as initial pH (3.0–8.0), contact time (15–90 min), initial metal concentration (10–250 mg/L), and temperature (28–80°C).

- Analysis: After agitation, separate the adsorbent (via filtration or magnetic separation for magnetic composites). Analyze the residual metal ion concentration in the supernatant using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES).

- Calculation: Calculate the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (qₑ in mg/g) using the formula:

qₑ = (C₀ - Cₑ) * V / m, where C₀ and Cₑ are the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), V is the volume of solution (L), and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g) [16] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Chitosan Biosorbent Research

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary biosorbent material; source of amino functional groups [10] | Base polymer for creating composites and beads [16] |

| FeCl₃·6H₂O / FeSO₄·7H₂O | Precursors for synthesis of magnetic Fe₃O₄ (magnetite) nanoparticles [13] | Creating the magnetic core for easy separation of composites [12] [13] |

| Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Cross-linking agent; enhances chemical stability in acidic solutions [13] | Producing TPP-CMN; forms ionic bonds with chitosan amino groups [13] |

| Acetic Acid | Solvent for dissolving chitosan [10] | Preparation of chitosan coating solutions [13] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent; improves mechanical strength and acid resistance [16] | Cross-linking chitosan in composite beads (ASB-CBs) [16] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Precipitating agent for Fe₃O₄; pH adjustment in adsorption studies [13] | Precipitation during nanoparticle synthesis; adjusting solution pH [16] [13] |

| Vanillin | Surface modifying agent; introduces additional functional groups [13] | Producing vanillin-modified magnetic chitosan (V-CMN) [13] |

Chitosan's natural abundance, biodegradability, and unique polycationic structure confer a innate and powerful affinity for heavy metal ions, solidifying its status as a premier biosorbent material. While raw chitosan has limitations, the development of nanomagnetic chitosan composites represents a significant advancement, successfully addressing challenges related to separation, stability, and sorption capacity. Comparative data clearly shows that these engineered composites, such as TPP-CMN and V-CMN, achieve superior removal efficiencies for a wide spectrum of toxic metals like Pb(II), Cd(II), and Cu(II), outperforming many alternative materials like raw food wastes or bone char. The integration of magnetic properties not only enhances performance but also aligns with sustainable water treatment goals by enabling easy recovery and reuse. Future research should focus on optimizing synthesis for lower costs, exploring selective modifications for complex wastewater, and scaling up production to facilitate the real-world application of these highly promising composite materials.

The removal of heavy metals from contaminated water sources represents a critical challenge in environmental remediation. Among the various technologies developed, adsorption has emerged as a preferred method due to its simplicity, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness [17]. However, conventional adsorbents often present limitations in recovery and reusability, necessitating complex separation processes that increase operational costs and potential for secondary pollution. The integration of magnetic iron oxides, primarily Fe₃O₄ (magnetite) and γ-Fe₂O₃ (maghemite), into composite materials has revolutionized this field by enabling efficient magnetic separation while enhancing adsorption performance [5] [17]. These magnetic components impart their unique properties to composites, allowing for rapid retrieval using external magnetic fields after the adsorption process is complete, thereby addressing key challenges in practical application of nanoparticle-based water treatment technologies.

The combination of magnetic iron oxides with biopolymers such as chitosan represents a particularly promising approach, merging the excellent adsorption properties of chitosan with the magnetic responsiveness of iron oxides [5] [18]. Chitosan, derived from chitin, offers abundant amino and hydroxyl functional groups that effectively coordinate with heavy metal ions, while the magnetic components facilitate separation and reuse [5] [19]. This comparative analysis examines the performance of various nanomagnetic chitosan composites for heavy metal removal, with focus on their adsorption capacities, separation efficiency, reusability, and implementation in complex wastewater environments.

Performance Comparison of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

The efficacy of nanomagnetic chitosan composites varies significantly based on their structural composition, functionalization methods, and target heavy metals. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of key composite types documented in recent research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metal Removal

| Composite Type | Target Heavy Metals | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Equilibrium Time (min) | Magnetic Separation | Reusability Cycles | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) [5] | Cu(II), Pb(II), Ni(II) | Pb(II): 220.9, Cu(II): 216.8, Ni(II): 108.9 | 120 | 12 emu/g saturation magnetization | Not specified | High versatility for multiple metals, good magnetization |

| Fe₃O₄/Chitosan/Polypyrrole [20] | Cr(VI) | 193.23 | Not specified | Efficient magnetic recovery | 5 cycles (84.32% efficiency) | Excellent acidic stability, good recyclability |

| CS/Fe₃O₄ Nanocomposite [18] | Mixed heavy metals | 100% removal efficiency | 30 | Effective magnetic response | Not specified | Broad-spectrum removal, rapid kinetics |

| Xanthate-Modified Magnetic Composite (XMPC) [19] | Cd(II) | 307 | 120 | Easy magnetic separation | Multiple reuses demonstrated | Exceptional Cd(II) capacity, chemically stable |

| NH₂-Fe₂O₃/CS [21] | Pb(II), Cu(II), Cd(II) | Selective adsorption: Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Cd(II) | 120 | Magnetic recovery feasible | Not specified | Excellent selectivity for Pb(II) |

| Carbonized Chitosan-Fe₃O₄-SiO₂ [22] | Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) mixture | 2908.92 (total capacity) | 90 | Magnetic separation enabled | Not specified | Extraordinary capacity for mixed metals |

The data reveals that functionalization strategies profoundly influence composite performance. Xanthate modification [19] yields exceptional cadmium uptake capacity (307 mg/g), while carbonization combined with silica incorporation [22] produces remarkably high total adsorption capacity (2908.92 mg/g) for mixed metal systems. Selectivity patterns also vary significantly, with NH₂-functionalized composites [21] exhibiting preferential adsorption for lead over copper and cadmium, following the trend Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Cd(II).

Table 2: Separation Efficiency and Practical Implementation Characteristics

| Composite Type | Saturation Magnetization | Separation Efficiency | Optimal pH Range | Real-Wastewater Performance | Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) [5] | 12 emu/g | Easy magnetic separation | Not specified | Not tested | Contains ~50 wt% chitosan |

| CS/Fe₃O₄ Nanocomposite [18] | Not specified | Effective magnetic response | Not specified | 100% removal from petroleum water | Green synthesis from plant extract |

| Xanthate-Modified Magnetic Composite (XMPC) [19] | Not specified | Easily magnetically separated | Not specified | Not tested | Improved mechanical stability vs. pure chitosan |

| Fe₃O₄/γ-Fe₂O₃-based Composites [23] | Not specified | Magnetically separable | Varied with MOF component | 89-95% dye degradation | MOF framework stability |

| Carbonized Chitosan-Fe₃O₄-SiO₂ [22] | Not specified | Easy magnetic separation | pH = 9 | Not tested | Green synthesis from biowaste |

Magnetic separation capability is consistently demonstrated across composite types, with saturation magnetization values around 12 emu/g sufficient for effective recovery [5]. Composites tested in real wastewater environments, such as petroleum water [18], show promising performance with complete heavy metal removal within 30 minutes, demonstrating practical potential beyond laboratory conditions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis Approaches

Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCC) Preparation [5]: The synthesis involves embedding pre-formed magnetite/maghemite nanoparticles within a chitosan matrix. Chitosan is typically dissolved in dilute acetic acid solution, followed by addition of iron oxide nanoparticles under mechanical stirring. The composite is then precipitated using alkaline solution, washed, and dried. Characterization through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) confirms approximately 50 wt% chitosan content, while zeta potential measurements determine an isoelectric point of pH 8-8.5, indicating favorable conditions for cation adsorption.

Green Synthesis of CS/Fe₃O₄ Nanocomposite [18]: This environmentally benign approach utilizes Laurus nobilis leaf extract for bioreduction and stabilization. Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles are first synthesized using the aqueous leaf extract, then coated with chitosan extracted from shrimp shells. The spherical nanoparticles exhibit average sizes of 21.3 nm for Fe₃O₄ and 28 nm for the composite, with optical bandgap energies of 2.62 eV and 1.81 eV, respectively, indicating enhanced photocatalytic potential in the composite form.

Xanthate-Modified Magnetic Composite (XMPC) Fabrication [19]: This multi-step synthesis begins with creation of magnetic Fe₃O₄@SiO₂ core-shell nanoparticles via co-precipitation and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) hydrolysis. The magnetic particles are then incorporated into a polyvinyl alcohol and chitosan matrix, followed by xanthate modification using carbon disulfide under alkaline conditions. This introduction of xanthate groups significantly enhances heavy metal binding capacity through formation of stable complexes.

Carbonized Chitosan-Fe₃O₄-SiO₂ Synthesis [22]: This novel green nanocomposite preparation involves carbonizing chitosan as a precursor material, then functionalizing with magnetite (Fe₃O₄) and silica (SiO₂) extracted from sugarcane bagasse. The carbonization enhances porosity and stability, while silica improves heavy metal adsorption capacity and magnetite enables magnetic separation. The composite demonstrates exceptional adsorption capacity for mixed metal systems.

Adsorption Experiment Methodologies

Batch adsorption experiments follow standardized protocols across studies [5] [20] [19]. Typically, a predetermined amount of composite is added to heavy metal solutions at controlled pH, temperature, and agitation speed. Samples are collected at time intervals, separated magnetically, and the supernatant analyzed for residual metal concentration using techniques such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or atomic absorption spectroscopy.

Kinetic and Isotherm Modeling [5] [20] [19]:

- Pseudo-second-order kinetics commonly best describe adsorption processes, indicating chemisorption as the rate-limiting step.

- Langmuir isotherm models frequently provide better fit than Freundlich models, suggesting monolayer adsorption on homogeneous surfaces.

- Thermodynamic studies consistently show spontaneous and endothermic processes for effective composites.

Competitive Adsorption Studies [21]: In ternary metal systems (Pb(II), Cu(II), Cd(II)), experiments reveal selective adsorption patterns. Composites like NH₂-Fe₂O₃/CS exhibit preferential adsorption following the order Pb(II) > Cu(II) > Cd(II), with significantly higher lead removal rates attributable to greater binding affinity and possibly coordination geometry preferences.

Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive materials characterization employs multiple analytical methods:

- Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): Reveals surface morphology, particle size, and dispersion [18] [21].

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and confirms successful modification [20] [21].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Determines crystallinity and phase composition of magnetic components [18] [21].

- Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM): Quantifies magnetic properties and separation potential [5].

- BET Surface Area Analysis: Measures specific surface area and pore characteristics [21].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Assesses thermal stability and composite composition [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the typical experimental process from synthesis to application:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for developing and evaluating nanomagnetic chitosan composites, covering synthesis, characterization, and application phases.

Mechanisms of Adsorption and Separation

Heavy Metal Capture Mechanisms

The exceptional adsorption capacity of nanomagnetic chitosan composites stems from multiple simultaneous mechanisms:

Coordination and Complexation [5] [21]: The amino (-NH₂) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups of chitosan serve as electron donors, forming coordinate covalent bonds with heavy metal ions. This chemisorption process is confirmed by pseudo-second-order kinetic models [19]. In NH₂-functionalized composites [21], the introduction of additional amino groups further enhances metal coordination capability.

Electrostatic Interactions [20]: Protonation of amino groups in acidic media creates positive surfaces that attract anionic metal species through Coulombic forces. For Cr(VI) removal, this mechanism predominates at low pH, with efficiency decreasing as pH increases due to reduced protonation.

Chemical Reduction [20]: Some composites, particularly those with polypyrrole components, facilitate reduction of toxic Cr(VI) to less hazardous Cr(III), enhancing removal through precipitation and coordination of the reduced species.

Ion Exchange [22]: Functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl can exchange protons or other ions for heavy metal cations in solution, contributing to overall uptake capacity.

The following diagram illustrates the primary adsorption mechanisms at the composite-water interface:

Diagram 2: Multifunctional adsorption mechanisms in nanomagnetic chitosan composites, culminating in magnetic separation after metal capture.

Magnetic Separation Mechanism

The separation process leverages the inherent magnetic properties of Fe₃O₄ and γ-Fe₂O₃ components [5] [17]. When an external magnetic field is applied, the magnetic moments within the nanoparticles align, generating a net attraction force that exceeds Brownian motion and fluid drag forces. This enables rapid segregation of particle-bound heavy metals from treated water. Composites with saturation magnetization values of approximately 12 emu/g demonstrate efficient separation capabilities [5], with higher values further improving recovery efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composite Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary biopolymer matrix providing adsorption sites | Source of amino and hydroxyl groups for metal coordination [5] [18] [19] |

| Fe₃O₄/γ-Fe₂O₃ Nanoparticles | Magnetic component enabling separation | Core magnetic material for composite recovery [5] [18] [23] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Polymer additive enhancing mechanical stability | Improves film formation and durability in composites [19] |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Silica source for core-shell structures | Creates protective SiO₂ layer on magnetic nanoparticles [19] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for chitosan | Enhances chemical stability and reusability [21] |

| Xanthating Agents (CS₂/NaOH) | Introduction of sulfur-containing functional groups | Enhances heavy metal chelation, particularly for soft metals [19] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Stabilizing agent for nanoparticles | Prevents aggregation and improves dispersion [24] |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) | Amino-functionalization agent | Introduces additional amine groups for enhanced metal binding [25] |

| Plant Extracts (e.g., Laurus nobilis) | Green synthesis reducing/ stabilizing agents | Eco-friendly alternative to chemical reducing agents [18] |

The integration of Fe₃O₄ and γ-Fe₂O₄ into chitosan composites represents a significant advancement in heavy metal removal technologies, successfully addressing the critical challenge of nanoparticle recovery while enhancing adsorption performance through synergistic effects. Comparative analysis reveals that while base magnetic chitosan composites offer good all-around performance [5], strategically functionalized composites demonstrate specialized superiority: xanthate-modified variants excel in cadmium removal [19], hyperbranched composites with PAMAM dendrimers show remarkable selectivity [25], and carbonized chitosan composites achieve extraordinary capacity for mixed metal systems [22].

The magnetic revolution in water treatment continues to evolve, with current research focusing on enhancing selectivity for specific heavy metals, improving stability in extreme pH conditions, and developing scalable green synthesis methods. The optimal composite selection depends heavily on the specific application requirements, including target metals, wastewater composition, and operational constraints. As these technologies transition from laboratory validation to real-world implementation, nanomagnetic chitosan composites stand poised to make substantial contributions to global efforts in water purification and heavy metal pollution mitigation.

In the pursuit of advanced water purification technologies, nanomagnetic chitosan composites have emerged as a leading class of materials for removing heavy metals from contaminated water. The performance of these materials hinges on a fundamental principle of nanoscience: the strategic optimization of surface area and active sites through precise engineering at the nanoscale. By integrating magnetic nanoparticles with the biopolymer chitosan and various functional modifiers, researchers create sophisticated architectures that maximize the availability of binding sites for heavy metal ions while incorporating practical features for material recovery and reuse.

This guide provides an objective comparison of various nanomagnetic chitosan composites, evaluating their removal efficiency for different heavy metals based on experimental data from recent scientific studies. We examine how different modification strategies—including the incorporation of cyclodextrin, lignin, polyvinyl alcohol, silica, and other functional groups—synergistically enhance the inherent properties of chitosan to create composites with superior adsorption capabilities.

Comparative Performance of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

The efficacy of nanomagnetic chitosan composites varies significantly based on their specific composition, structure, and target pollutants. The table below summarizes the removal performance of various composites for different heavy metals, based on experimental data from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparison of heavy metal removal by different nanomagnetic chitosan composites

| Composite Type | Target Pollutant | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Optimal pH | Removal Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan-Magnetite Strip | Cr(VI) | - | - | 92.33% | [26] |

| S1@Chitosan (Na-Fe Silicate) | Cd(II) | 389.11 | 7.5 | - | [27] |

| PVA-Modified Chitosan | Cu(II) | 303.29 | - | - | [28] |

| PVA-Modified Chitosan | Ni(II) | 209.08 | - | - | [28] |

| PVA-Modified Chitosan | Zn(II) | 173.39 | - | - | [28] |

| Chitosan-Lignin Biocomposite | Cr(VI) | 72.61 | 2.0 | - | [29] |

| Fe₃O₄@Si-OH@CS | Cr(VI) | - | 2.5 | High | [30] |

| Fe₃O₄@Si-OH@CS | As, Hg, Se | - | - | High | [30] |

Table 2: Surface characteristics and experimental conditions of selected composites

| Composite Type | Surface Area (m²/g) | Contact Time (min) | Initial Concentration | Temperature (K) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1@Chitosan | 30.94 | 50 | Varying | 298 | [27] |

| Nanomagnetite/Chitosan (CSG) | 878.7 | 720 (adsorption) | Varying | Ambient | [31] |

| PVA-Modified Chitosan | 9.36 | - | Multi-metal system | Varied | [28] |

Fundamental Mechanisms of Synergistic Enhancement

Surface Area Expansion

The incorporation of magnetite nanoparticles and porous additives dramatically increases the available surface area of chitosan composites. For instance, while native chitosan has limited surface area, composites like nanomagnetite/chitosan (CSG) demonstrate remarkably high surface areas of up to 878.7 m²/g [31]. This expansion creates more opportunities for metal ions to encounter and bind to active sites. The porous structure of composites such as chitosan-lignin provides numerous accessible binding sites, facilitating higher adsorption capacities for both dyes and heavy metals [29].

Active Site Optimization

Nanoscale engineering enhances not only the quantity but also the quality and accessibility of active sites:

- Amino Group Utilization: Chitosan's primary amino groups serve as key coordination sites for metals [32]. Composite formation protects these groups while increasing their accessibility.

- Multi-functional Group Integration: Modifiers like cyclodextrin introduce additional functional groups that create diverse binding environments [33]. Silanol groups (Si-OH) in silica-modified composites provide additional adsorption sites through ion exchange and complexation [30].

- Synergistic Binding: In chitosan-lignin composites, the combination of amino, hydroxyl, and phenolic groups enables multiple simultaneous interactions with metal ions, leading to superior removal efficiency compared to either component alone [29].

Magnetic Separation Enhancement

The integration of Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles provides ferrimagnetism, enabling efficient recovery of spent adsorbents using external magnetic fields [31] [26] [30]. This practical advantage maintains the high surface area and active site availability while facilitating material reuse—a critical consideration for practical applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis Methods

Co-precipitation for Magnetic Composites

The most common synthesis approach for nanomagnetic chitosan composites involves co-precipitation, as exemplified by the Fe₃O₄@Si-OH@CS preparation [30]:

- Magnetic Core Formation: FeCl₃·6H₂O and FeSO₄·7H₂O dissolved in deionized water at 2:1 molar ratio, followed by addition of NH₃·H₂O at 80°C with continuous stirring for 40 minutes

- Silica Functionalization: Magnetic fluid dispersed in ethanol/water mixture, followed by addition of NH₃·H₂O and ethyl orthosilicate with agitation at 60°C for 4.5 hours

- Chitosan Coating: Fe₃O₄@Si-OH nanoparticles dispersed in chitosan solution (1%) with glutaraldehyde as crosslinker, stirred at 60°C for 30 minutes

- Product Recovery: Magnetic separation, washing with acetic acid (3%), and drying at 80°C

Similar co-precipitation methods are employed for other magnetic chitosan composites, with variations in precursor ratios and functionalization steps [33] [26].

Composite Formation without Magnetic Core

For non-magnetic composites like chitosan-lignin:

- Chitosan Solution Preparation: Chitosan dissolved in acetic acid (0.1 mol/L) with continuous stirring for 24 hours

- Lignin Integration: Predetermined amount of lignin dissolved separately, then gradually added to chitosan solution

- Film Formation: Solution cast onto glass supports, dried at room temperature, peeled, and converted to base form

- Powder Preparation: Dried composite ground, washed with distilled water, vacuum filtered, and dried at 100°C [29]

Adsorption Experiments

Standard batch adsorption experiments typically involve:

- Solution Preparation: Stock solutions of heavy metals (typically 500-1000 mg/L) prepared using salts like K₂Cr₂O₇ for Cr(VI) or Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O for Cd(II)

- pH Adjustment: Solution pH adjusted using NaOH or HCl (0.1 M) to optimal conditions

- Adsorption Process: Composite added to metal solution at specific dosage, with agitation at constant speed and temperature

- Sampling and Analysis: Samples collected at time intervals, centrifuged, and supernatant analyzed via AAS or UV-Vis spectrophotometry [27] [29] [28]

Analytical Methods

Comprehensive characterization employs multiple techniques:

- Surface Area and Porosity: BET analysis using N₂ adsorption-desorption at 77K [27] [31]

- Structural Confirmation: FT-IR spectroscopy to identify functional groups [33] [26]

- Crystallinity Assessment: XRD analysis to determine crystalline phases [31] [26]

- Morphological Examination: SEM and TEM for surface morphology and particle size [33] [31]

- Magnetic Properties: VSM to confirm magnetic behavior [31] [26]

- Elemental Composition: EDX for elemental mapping and confirmation [33] [27]

Visualization of Synthesis and Mechanism

Diagram 1: Synthesis pathway and adsorption mechanism of nanomagnetic chitosan composites

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents for synthesizing and testing nanomagnetic chitosan composites

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary biopolymer matrix providing amino groups for metal coordination | Medium molecular weight [33]; Low viscosity < 200 mPa·s [30]; High molecular weight, 90% deacetylation [28] |

| FeCl₃·6H₂O and FeSO₄·7H₂O | Precursors for magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticle synthesis via co-precipitation | Used in 2:1 molar ratio [26] [30] |

| NH₃·H₂O (Ammonium Hydroxide) | Precipitation agent for magnetite formation; catalyst for silica condensation | 25-28% solution [30] |

| Ethyl Orthosilicate | Silicon precursor for creating silanol-functionalized surfaces | [30] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for chitosan stabilization | 50% solution [30] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Polymer modifier enhancing mechanical strength and surface properties | [28] |

| Lignin | Biopolymer additive introducing phenolic groups for enhanced metal binding | 97% purity [29] |

| β-Cyclodextrin | Macrocyclic modifier creating host-guest complexes and additional binding sites | Grafted onto magnetic chitosan [33] |

| Heavy Metal Salts | Target pollutants for adsorption testing | K₂Cr₂O₇ for Cr(VI) [26] [29]; Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O for Cd(II) [27] |

The comparative analysis of nanomagnetic chitosan composites reveals a clear structure-property-performance relationship. Composites with higher surface areas and optimized active sites consistently demonstrate superior heavy metal removal capabilities. The integration of magnetic components enables practical recovery and reuse, while chemical modifiers like silanol groups, lignin, and cyclodextrin introduce complementary binding mechanisms that enhance both capacity and selectivity.

The experimental data indicate that composite performance depends significantly on the target metal ion and solution conditions. Cr(VI) removal is most efficient under acidic conditions, while Cd(II) removal occurs optimally near neutral pH. Multi-metal systems present competitive adsorption scenarios where composite affinity varies across different metal ions.

These findings underscore the importance of tailored composite design for specific application requirements. Future research directions should focus on developing selective composites for complex multi-pollutant systems, improving regeneration efficiency, and scaling up synthesis protocols for practical water treatment applications.

The escalating contamination of aquatic environments by heavy metals constitutes a critical threat to global ecosystems and human health, driving an urgent need for effective and sustainable remediation strategies [34]. Among the various technologies developed, adsorption is widely regarded as a superior method due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency [35]. Within this domain, nanomagnetic chitosan composites have emerged as a frontier adsorbent class, synergizing the exceptional metal-binding capacity of chitosan—a natural, biodegradable polymer—with the facile separation capabilities of magnetic nanoparticles [9]. The research field surrounding these composites is experiencing explosive growth, characterized by vigorous international collaboration and a high rate of scientific output. This review employs a bibliometric analysis to map this dynamic landscape, providing a systematic comparison of the removal efficiencies of various nanomagnetic chitosan composites for heavy metals, supported by experimental data and mechanistic insights.

Bibliometric Analysis of the Research Field

A quantitative examination of scientific literature reveals the vigorous evolution of research into chitosan-based materials for water treatment. A systematic review analyzing 1,855 publications from 2005 to 2025 documented an annual growth rate of 21.52% and an average of 32.7 citations per article, underscoring the field's strong scientific vitality and impact [34]. A separate bibliometric study focusing on 1,690 documents from 2014 to 2024 found a similarly robust annual growth rate of 16.86% and an average of 32.12 citations per document, confirming the sustained and rising interest in this area [36] [37].

Geographically, research production is heavily concentrated in Asia. China, India, and Iran collectively contribute nearly 60% of the global scientific output on chitosan composites for wastewater treatment [34] [36]. This high level of productivity is complemented by significant international cooperation, with about 26.78% of publications involving cross-border collaborations, highlighting the global recognition of the water pollution challenge and the concerted effort to address it [36].

The intellectual focus of the field, as revealed by keyword network analysis, is centered on several key themes. Predominant among these are "adsorption mechanisms" and "composite functionalization," with a strong and growing emphasis on "magnetic hybrids" and "nano-reinforced composites" designed for the targeted removal of specific pollutants [36] [9].

Comparative Removal Efficiency of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

The performance of nanomagnetic chitosan composites varies significantly based on their specific constituents and synthesis methods. The table below provides a comparative overview of the removal efficiencies of different composite types for various heavy metals, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Removal Efficiencies for Various Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

| Composite Name | Target Heavy Metal(s) | Reported Removal Efficiency | Optimal pH | Key Findings/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan/g-HNTs@ZnγFe₃O₄ [38] | Cr(III), Fe(III), Mn(II) | 95.2%, 99.06%, 87.1% | 9.0 | Superior performance attributed to multiple functional groups and coordination bonding. |

| M-Ch/CNF-Fe(III) [12] | Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) | High removal demonstrated | Varied (1-8) | Porous structure effective for multiple metals; adsorption fitted Langmuir isotherm. |

| Chitosan-Magnetic Nanocomposites [34] | Various dyes and toxic metals | Adsorption capacities > 400 mg g⁻¹ | Not Specified | Engineered nanostructure provides high surface area and enhanced porosity. |

| Magnetic Chitosan (General Review) [9] | Pb, Hg, Cr, Cd, Cu, As | Outstanding adsorption performance | Varied | Good adaptability in real industrial wastewater and multi-metal systems. |

The data indicates that composite materials often leverage synergistic effects between their components. For instance, the incorporation of halloysite nanotubes and zinc-doped magnetite (Chitosan/g-HNTs@ZnγFe₃O₄) creates a quaternary nanocomposite with a dense array of functional groups, leading to exceptional removal efficiencies exceeding 95% for certain ions like Fe(III) [38]. Similarly, composites that integrate biopolymers like cellulose (M-Ch/CNF-Fe(III)) benefit from the combined reactive sites of both polymers and the magnetic properties of Fe₃O₄, enabling effective removal of oxyanions like Cr(VI) and cations like Pb(II) and Cu(II) across a wide pH range [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure the reproducibility of the high-performance results cited, this section outlines the standard experimental protocols for synthesizing a representative composite and evaluating its adsorption efficacy.

Synthesis of a Magnetic Chitosan Nanocomposite

A common and effective method for preparing magnetic chitosan composites is the chemical co-precipitation technique [38] [12]. The following workflow details the synthesis of a magnetic chitosan/cellulose-Fe(III) composite [12]:

Key Reagents and Functions:

- FeCl₃·6H₂O: Iron precursor for generating magnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles.

- Sodium Acetate: Serves as an alkaline agent to facilitate precipitation.

- Ethylene Glycol: Acts as a solvent and reducing agent.

- Chitosan: Provides the primary matrix with amino and hydroxyl functional groups for metal binding.

- Cellulose Nanofiber (CNF): Enhances porosity and mechanical strength, and provides additional hydroxyl groups.

- 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Chloride (Ionic Liquid): Functions as a green solvent to disperse and homogenize the polymer blend.

- Tween 80: A surfactant used to stabilize the emulsion during synthesis.

Batch Adsorption Experiment Protocol

The evaluation of adsorption performance follows a standardized batch protocol to determine optimal conditions and capacities [38] [12]. The workflow below is generic and can be applied to test any composite for various heavy metals.

Critical Parameters & Isotherm/Kinetic Modeling:

- Parameters: The effects of pH (1.0-9.0), adsorbent dosage (0.05-1.0 g/L), contact time (15-90 min), initial metal concentration, and temperature (28-80°C) are systematically investigated [38] [12].

- Isotherm Models: Experimental data is fitted to models like Langmuir (assuming monolayer adsorption) and Freundlich (assuming heterogeneous surface) to understand the adsorption distribution at equilibrium [38] [12].

- Kinetic Models: Data from time-series experiments is fitted to pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models to elucidate the adsorption rate and mechanism [38] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of nanomagnetic chitosan composites rely on a core set of reagents and materials. The following table lists these essential components and their functions in synthesis and application.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Composite Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research & Development | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary biopolymer matrix; provides amino (-NH₂) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups for metal coordination/chelation. | Derived from shrimp, crab shells; backbone of all composites [34] [39]. |

| Magnetic Precursors (FeCl₃, FeSO₄) | Source of iron for in-situ precipitation of magnetic nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄, γ-Fe₂O₃) within the polymer matrix. | FeCl₃·6H₂O used in co-precipitation [38] [12]. |

| Cross-linkers (Glutaraldehyde, Epichlorohydrin) | Stabilize chitosan hydrogels, improve mechanical strength and chemical resistance in aqueous environments. | Glutaraldehyde used in AUCH-G hydrogels for alkaline conditions [40]. |

| Natural Reinforcements (Halloysite Nanotubes, Cellulose Nanofiber) | Enhance surface area, porosity, mechanical strength, and introduce additional sorption sites. | Halloysite Nanotubes (HNTs) [38]; Cellulose Nanofiber (CNF) [12]. |

| Metal Salts (K₂Cr₂O₇, Pb(NO₃)₂, CuSO₄) | Used to prepare standard solutions for simulating heavy metal contamination in adsorption experiments. | K₂Cr₂O₇, CuSO₄·5H₂O, Pb(NO₃)₂ used in batch tests [12]. |

The global research landscape for nanomagnetic chitosan composites is marked by rapid growth and intense international focus, primarily driven by the pressing need for advanced water purification technologies. Bibliometric evidence confirms the field's strong scientific vitality and its identification as a high-priority research area. Quantitative comparisons reveal that these composites can achieve remarkable removal efficiencies, often exceeding 90% or even 95% for critical heavy metals like Cr(III), Fe(III), and Pb(II). Their performance is heavily influenced by the specific design of the composite, which tailors properties such as surface area, porosity, and functional group density. The reproducibility of these high-performance results is ensured by well-established experimental protocols for synthesis and evaluation. As research progresses, future efforts are directed toward optimizing preparation and modification processes, deepening the understanding of interactions in complex multi-metal systems, and enhancing the regeneration ability of these promising materials for sustainable, real-world application [9].

Synthesis and Performance: Building and Testing Effective Composites

The removal of heavy metals from wastewater is a critical environmental challenge due to their non-biodegradable nature and toxic effects on living organisms [41] [42]. Among various treatment technologies, adsorption has gained significant attention for its efficiency, operational simplicity, and cost-effectiveness [41]. In recent years, nanomagnetic chitosan composites have emerged as promising adsorbents, combining the excellent metal-binding capacity of chitosan with the facile magnetic separation capability of iron oxides [5] [6].

Chitosan, a natural biopolymer derived from chitin, possesses amino and hydroxyl functional groups that effectively coordinate with heavy metal ions [41]. However, its practical application is limited by low mechanical strength, solubility in acidic media, and difficult separation after use [41]. These limitations can be overcome by combining chitosan with magnetic nanoparticles and employing appropriate synthesis methods to enhance stability and performance [5] [43].

The comparative removal efficiency of nanomagnetic chitosan composites is fundamentally governed by their synthesis route. This review comprehensively examines three core preparation techniques—co-precipitation, cross-linking, and hydrothermal synthesis—focusing on their methodological principles, resultant composite characteristics, and performance in heavy metal removal applications for researcher and scientist audiences.

Methodological Principles and Experimental Protocols

Co-precipitation

Principles: Co-precipitation is a straightforward and widely used method for synthesizing magnetic chitosan composites. This technique involves the simultaneous precipitation of magnetic iron oxides (typically magnetite, Fe₃O₄, or maghemite, γ-Fe₂O₃) and their incorporation into a chitosan matrix under alkaline conditions [43]. The process leverages the in-situ formation of magnetic nanoparticles within the chitosan solution, allowing for direct integration of both components.

Experimental Protocol (Chitosan-Nickel Ferrite Composite):

- Step 1: Dissolve ferric chloride (FeCl₃·6H₂O) and nickel chloride (NiCl₂·6H₂O) in deionized water at a molar ratio of 2:1 (Fe:Ni) [43].

- Step 2: Prepare a 1% (w/v) chitosan solution by dissolving chitosan powder in acetic acid solution (1% v/v) with continuous stirring until a clear solution is obtained [43].

- Step 3: Mix the chitosan solution with the metal salts solution under constant stirring at 60°C for 30 minutes to ensure homogeneous distribution [43].

- Step 4: Adjust the pH to approximately 11 using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution (0.2 M) to initiate precipitation. The addition of a small amount of oleic acid (0.01 mL) as a surfactant can help control particle growth and prevent aggregation [43].

- Step 5: Heat the mixture to 80°C and maintain with stirring for 6 hours to complete the reaction and aging process [43].

- Step 6: Separate the resulting dark brown precipitates by centrifugation, wash thoroughly with distilled water and ethanol to remove impurities, and dry at room temperature for 20 hours [43].

- Step 7: For enhanced crystallinity, calcine the product at 600°C for 3 hours in a tube furnace [43].

Cross-linking

Principles: Cross-linking method focuses on strengthening the chitosan matrix by creating covalent bonds between polymer chains using cross-linking agents. This approach enhances the chemical stability and mechanical robustness of chitosan composites, preventing their dissolution in acidic environments and improving reusability [41]. Magnetic components can be incorporated either during or after the cross-linking process.

Experimental Protocol (Magnetic Chitosan Microspheres):

- Step 1: Prepare a chitosan solution (2-4% w/v) in dilute acetic acid (2% v/v) and filter to remove any undissolved particles [44].

- Step 2: Synthesize or disperse pre-formed magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) in the chitosan solution under ultrasonication for 30 minutes to achieve homogeneous dispersion [44].

- Step 3: Add the cross-linking agent (commonly glutaraldehyde at 1-2% v/v concentration) dropwise to the mixture under continuous stirring. The amino groups of chitosan react with aldehyde groups to form Schiff base linkages [44].

- Step 4: For microsphere formation, drip the mixture into a coagulation bath containing sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution (0.1-0.5 M) or tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution (1-2% w/v) using a syringe pump [44].

- Step 5: Maintain the microspheres in the coagulation bath for 1-2 hours to complete the cross-linking and solidification process.

- Step 6: Collect the magnetic microspheres by filtration or magnetic separation, wash extensively with distilled water until neutral pH, and dry at 40-50°C [44].

Hydrothermal Synthesis

Principles: Hydrothermal synthesis utilizes elevated temperature and pressure in a sealed autoclave to facilitate the crystallization and assembly of magnetic chitosan composites. This method typically produces materials with enhanced crystallinity, controlled morphology, and high purity [45] [46]. The method allows for precise control over particle size and structure by adjusting reaction parameters.

Experimental Protocol (Magnetic Chitosan/Cellulose Hybrid Microspheres):

- Step 1: Dissolve chitosan and cellulose in NaOH/urea aqueous solution to form a homogeneous polymer solution [44].

- Step 2: Disperse pre-synthesized magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., γ-Fe₂O₃) in the polymer solution under vigorous stirring [44].

- Step 3: Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, filling 70-80% of its capacity to allow for pressure development [46].

- Step 4: Heat the autoclave to 120-180°C and maintain for 4-24 hours, depending on the desired crystallinity and particle size [46].

- Step 5: Allow the autoclave to cool naturally to room temperature.

- Step 6: Collect the resulting product by magnetic separation or centrifugation, wash with distilled water and ethanol, and dry at 60°C [44] [46].

Comparative Analysis of Composite Properties

The synthesis method significantly influences the structural characteristics, magnetic properties, and functional performance of nanomagnetic chitosan composites. The table below summarizes the key properties achievable through each method.

Table 1: Characteristics of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites Prepared by Different Methods

| Property | Co-precipitation | Cross-linking | Hydrothermal Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size (nm) | 40-100 [43] | 500-1000 [44] | 25-50 [44] |

| Surface Area (m²/g) | Moderate (50-150) | Variable (20-100) | High (200-400) [45] |

| Magnetization (emu/g) | 17-40 [43] | 10-25 | 12-20 [5] [6] |

| Crystallinity | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High [46] |

| Structural Control | Limited | Good for morphology | Excellent for morphology & size [46] |

| Processing Time | 6-12 hours [43] | 2-6 hours | 4-24 hours [46] |

| Scale-up Potential | Excellent | Good | Moderate |

| Equipment Cost | Low | Low | High (autoclave required) |

Structural and Morphological Characteristics

Co-precipitation typically yields composites with particle sizes ranging from 40-100 nm, as confirmed by TEM analysis of chitosan-nickel ferrite composites [43]. The process generally produces aggregates unless surfactants are employed to control particle growth.

Cross-linking method often results in larger particles or microspheres (500-1000 nm) with porous structures, suitable for column-based applications [44]. The cross-linking density significantly influences the swelling behavior and mechanical stability.

Hydrothermal synthesis enables the production of composites with controlled morphology and smaller particle sizes (25-50 nm) due to the accelerated reaction kinetics under high temperature and pressure conditions [44]. This method typically produces materials with higher crystallinity and more uniform particle size distribution compared to other methods [46].

Magnetic Properties

The saturation magnetization of composites determines their responsiveness to external magnetic fields for separation. Co-precipitation synthesized chitosan-nickel ferrite composites exhibit magnetization values of 40.67 emu/g for bare NiFe₂O₄ and 17.34 emu/g after chitosan coating [43]. Similarly, magnetic chitosan composites (MCC) prepared through related methods show saturation magnetization of approximately 12 emu/g, sufficient for efficient magnetic separation [5] [6].

Performance in Heavy Metal Removal

The efficacy of nanomagnetic chitosan composites in removing heavy metals from aqueous solutions varies significantly with the synthesis method, which influences the availability of active sites, diffusion pathways, and metal-binding kinetics.

Table 2: Heavy Metal Removal Performance of Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composites

| Heavy Metal | Synthesis Method | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Optimum pH | Equilibrium Time (min) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) | Cross-linking/MCC | 220.9 | 5-6 | 120 | [5] [6] |

| Cu(II) | Cross-linking/MCC | 216.8 | 5-6 | 120 | [5] [6] |

| Ni(II) | Cross-linking/MCC | 108.9 | 5-6 | 120 | [5] [6] |

| Cu(II) | Co-precipitation | 89-125 | 5-6 | 90-180 | [41] |

| Pb(II) | Co-precipitation | 110-180 | 5-6 | 90-180 | [41] |

| Various | Hydrothermal | 150-250 (estimated) | 5-7 | 60-120 | [44] |

Adsorption Capacity and Kinetics

Composites prepared by cross-linking demonstrate exceptional adsorption capacities for heavy metals, with reported values of 220.9 mg/g for Pb(II), 216.8 mg/g for Cu(II), and 108.9 mg/g for Ni(II) [5] [6]. The cross-linked structure provides mechanical stability while maintaining accessibility to functional groups.

Co-precipitation synthesized composites show moderately high adsorption capacities (89-250 mg/g for Cu(II) and Pb(II), depending on specific modifications) [41]. The adsorption process typically follows pseudo-second-order kinetics, indicating chemisorption as the rate-limiting step [5].

Hydrothermal synthesis produces composites with estimated capacities of 150-250 mg/g, attributed to their high surface area and enhanced crystallinity [44] [45]. The efficient incorporation of magnetic components and chitosan matrix under hydrothermal conditions creates hierarchically porous structures conducive to metal uptake.

pH Dependence and Regeneration

The adsorption of heavy metals onto nanomagnetic chitosan composites is highly pH-dependent, with optimal performance observed in slightly acidic to neutral conditions (pH 5-7). Under acidic conditions (pH < 4), competition between metal ions and protons for amino groups reduces uptake, while at higher pH values, metal hydrolysis and precipitation may occur [41].

Regeneration studies indicate that cross-linked composites maintain their adsorption capacity over multiple cycles (4-7 cycles) due to enhanced mechanical and chemical stability [41]. Dilute acid solutions (HCl or HNO₃, 0.1-0.5 M) effectively desorb bound metals without significantly degrading the chitosan matrix.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nanomagnetic Chitosan Composite Synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration/Purity | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Polymer matrix providing adsorption sites | Low to medium molecular weight; >75% deacetylation | Soluble in dilute acetic acid; avoid bacterial contamination |

| FeCl₃·6H₂O / Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O | Iron precursor for magnetic nanoparticles | ≥98% purity; analytical grade | Moisture-sensitive; store in desiccator |

| NiCl₂·6H₂O / Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Transition metal precursors for ferrites | ≥98% purity; analytical grade | Handle with appropriate PPE due to toxicity |

| NaOH | Precipitation agent and pH adjustment | 0.1-5 M solutions; pellet form | Highly exothermic when dissolved; use caution |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent | 1-2% v/v aqueous solution | Toxic; use in fume hood with proper ventilation |

| Acetic Acid | Solvent for chitosan | 1-2% v/v aqueous solution | Corrosive; use in well-ventilated area |

| Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic cross-linker for microsphere formation | 1-2% w/v aqueous solution | Hygroscopic; store in airtight container |

| Oleic Acid | Surfactant for particle size control | 0.01-0.1% v/v | Can form stable foams during mixing |

| Ethylene Glycol | Solvent medium for hydrothermal synthesis | 0-100% v/v with water | Reflux conditions required for some syntheses |

The selection of an appropriate synthesis method for nanomagnetic chitosan composites represents a critical decision point that fundamentally determines their efficacy in heavy metal removal applications. Co-precipitation offers simplicity and scalability, making it suitable for large-scale wastewater treatment operations. Cross-linking provides enhanced chemical stability and excellent adsorption capacities, particularly beneficial for treating complex wastewater streams with variable pH conditions. Hydrothermal synthesis enables precise morphological control and high crystallinity, advantageous for fundamental studies and applications requiring specific structural features.

Future research should focus on optimizing synthesis parameters to enhance adsorption selectivity for specific heavy metals, improving regeneration efficiency for long-term use, and developing hybrid approaches that combine the advantages of multiple methods. The integration of characterization techniques with computational modeling will further advance our understanding of structure-property relationships, facilitating the rational design of next-generation nanocomposite adsorbents for environmental remediation.

In the pursuit of effective heavy metal remediation, chitosan has emerged as a promising biodegradable adsorbent. However, its inherent limitations, including poor mechanical strength, pH sensitivity, and difficult post-adsorption separation, restrict its practical application [47] [48]. To overcome these challenges, strategic modifications are employed. The integration of a magnetic core facilitates easy separation using an external magnet, significantly improving practicality [47] [49]. Further functionalization through crosslinking or composite formation enhances stability and adsorption capacity.

This guide focuses on three strategic modifications: crosslinking with Tripolyphosphate (TPP), crosslinking with Vanillin, and compositing with Cellulose. It objectively compares their performance in removing heavy metals, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, providing a clear framework for selecting and implementing these modifications in water treatment research.

Comparative Analysis of Modification Strategies

The performance of modified magnetic chitosan composites varies significantly based on the functionalization strategy and target heavy metal. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent research.

Table 1: Comparative Adsorption Performance of Functionalized Magnetic Chitosan Composites

| Functionalization Strategy | Target Heavy Metal | Reported Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Key Experimental Conditions | Primary Adsorption Mechanism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPP Crosslinking | Various (Cu, Pb, Cr) | Varies by specific composite design [47] | pH, temperature, and initial concentration dependent [47] | Ionic interaction, Electrostatic attraction [47] |

| Vanillin Crosslinking | (Mainly improves mechanical properties) [50] | (Not the primary focus of study) [50] | --- | Covalent crosslinking (improves matrix stability) [50] [51] |

| Cellulose Composite (Aerogel) | Cu(II) | 200.6 | Not specified | Coordination, Chelation [52] |

| Cellulose Composite (Aerogel) | Cr(VI) | 152.1 | Not specified | Coordination, Chelation [52] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Magnetic Chitosan (Base Material)

The coprecipitation method is a common and efficient technique for synthesizing the magnetic chitosan base material. The following workflow outlines the key steps for preparing crosslinked magnetic chitosan composites, starting with this base synthesis.

Diagram Title: Composite Preparation Workflow

In Situ Coprecipitation Method

This one-pot method is widely used for its simplicity [47].

- Step 1: Chitosan Dissolution. Chitosan is dissolved in a dilute acetic acid solution (e.g., 1-2% v/v) to obtain a homogeneous polymer solution [47].

- Step 2: Iron Ion Incorporation. Ferric (Fe³⁺) and ferrous (Fe²⁺) chloride solutions are added to the chitosan solution under an inert nitrogen atmosphere to prevent oxidation. The mixture is vigorously stirred to ensure uniform dispersion of ions within the polymer matrix [47].

- Step 3: Precipitation & Magnetic Formation. The solution is heated to 50-60°C, and an ammonium hydroxide solution is added dropwise under continuous stirring to raise the pH to 9-10. This alkaline environment causes the simultaneous precipitation of magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles and their integration with the chitosan chains [47].

- Step 4: Separation and Washing. The resulting magnetic chitosan (MCS) particles are separated from the suspension using an external magnet, washed repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol until neutral pH is achieved, and then dried [47].

Functionalization with Tripolyphosphate (TPP)

TPP is an anionic crosslinker that forms bridges with the protonated amino groups of chitosan through strong ionic interactions [47] [51].

- Crosslinking Procedure: The synthesized magnetic chitosan particles are dispersed in a deionized water and agitated. Aqueous Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution is added dropwise into this dispersion. The crosslinking reaction proceeds for a specified duration (e.g., 2-24 hours) with constant stirring [51]. The TPP-crosslinked magnetic chitosan (MCS-TPP) is then separated magnetically, washed, and dried.

Functionalization with Vanillin

Vanillin acts as a covalent crosslinker for chitosan, forming Schiff base linkages between its aldehyde groups and the primary amine groups of chitosan. This reaction significantly improves the mechanical properties of the chitosan matrix [50] [51].

- Crosslinking Procedure: The magnetic chitosan base is immersed in a 5% (w/v) vanillin solution prepared in ethanol. The mixture is agitated for a set period, such as 24 hours, to allow the crosslinking reaction to complete [51]. The resulting vanillin-crosslinked magnetic chitosan (MCS-Vanillin) is separated using a magnet, thoroughly washed with ethanol and water to remove unreacted vanillin, and dried.

Compositing with Cellulose

Incorporating cellulose, particularly in the form of bacterial cellulose nanofibers or as carboxymethyl cellulose, can enhance the porosity, water stability, and specific surface area of the composite adsorbent [52] [53] [54].

- Aerogel Composite Procedure: Chitosan and cellulose (or its derivatives) are co-dissolved in a suitable mutual solvent or blended in solution. Magnetic particles can be incorporated during this mixing step. The homogeneous mixture is then poured into a mold and subjected to a freeze-drying (lyophilization) process to create a porous three-dimensional aerogel structure [52] [53]. In some protocols, the composite is further crosslinked with agents like genipin or TPP after formation to improve its stability in aqueous environments [53].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key materials required for the synthesis and evaluation of functionalized magnetic chitosan composites.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Composite Synthesis and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary adsorbent matrix; provides amino and hydroxyl groups for metal binding and crosslinking. | Degree of deacetylation (affects amine group density) and molecular weight are critical parameters [48]. |

| FeCl₂·4H₂O & FeCl₃·6H₂O | Iron precursors for the in-situ synthesis of magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles. | Molar ratio of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ is typically maintained at 1:2 for stoichiometric magnetite formation [47]. |

| Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic crosslinker; enhances chemical stability and mechanical strength. | Concentration and reaction time influence crosslinking density and porosity [47] [51]. |

| Vanillin | Covalent crosslinker; significantly improves mechanical properties of the chitosan film/composite. | The aldehyde group forms Schiff bases with chitosan amines; often requires ethanol as a solvent [50] [51]. |