Natural vs. Anthropogenic Drivers of Surface Water Degradation: Analysis, Impacts, and Implications for Environmental and Human Health

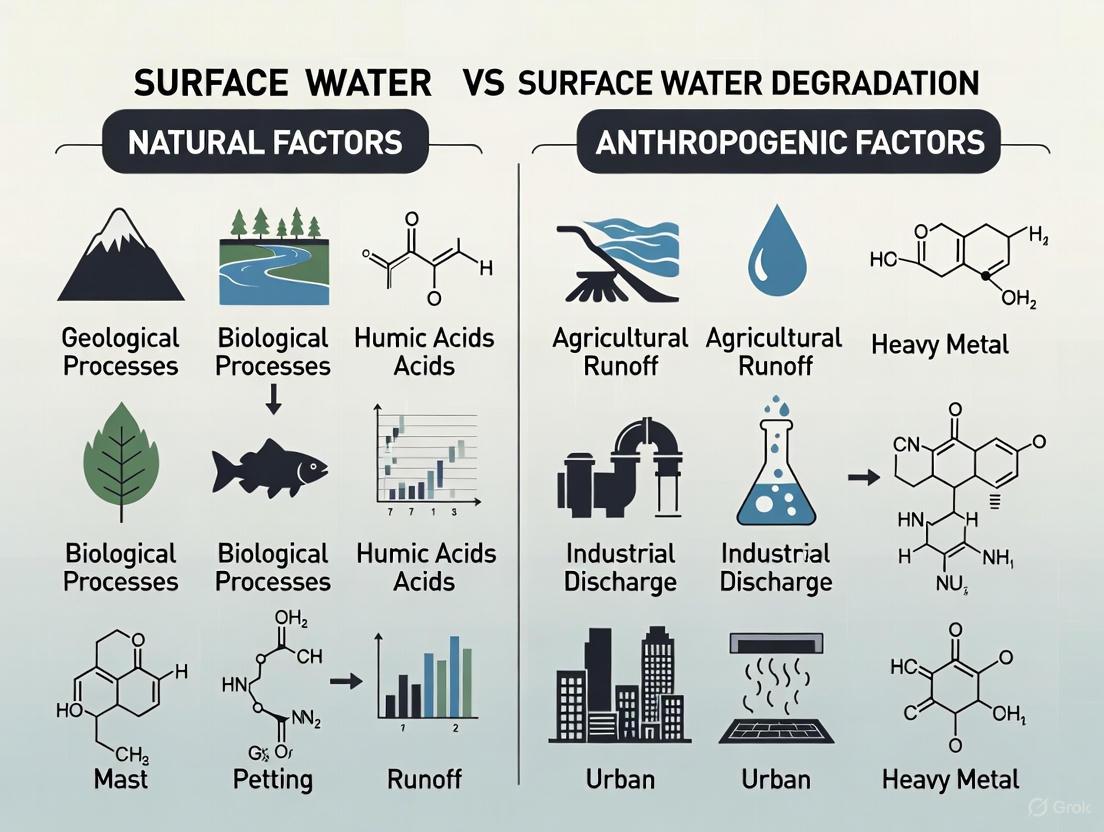

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct and synergistic roles of natural processes and human activities in surface water degradation.

Natural vs. Anthropogenic Drivers of Surface Water Degradation: Analysis, Impacts, and Implications for Environmental and Human Health

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct and synergistic roles of natural processes and human activities in surface water degradation. It explores foundational concepts by detailing key natural factors (climate, geology, seasonal hydrology) and major anthropogenic sources (agricultural, industrial, urban). The review covers advanced methodological frameworks for water quality assessment, including Water Quality Index (WQI) models, Pollution Index (PI) models, and machine learning techniques for large-scale spatial and seasonal analysis. It further examines troubleshooting and optimization through the efficacy of Best Management Practices (BMPs) and conservation strategies for mitigating anthropogenic impact. Finally, the article presents validation and comparative analyses using case studies and metric-based evaluations to disentangle human amplification from natural climatic trends. This synthesis offers critical insights for researchers and scientists engaged in environmental health, risk assessment, and drug development, where water quality is a foundational component of ecosystem and public health.

Unraveling the Sources: A Deep Dive into Natural and Anthropogenic Drivers of Water Quality

The composition of surface water is a product of a complex interplay between natural processes and anthropogenic influences. While human activities are major drivers of water quality degradation, understanding the fundamental natural factors—climate, geology, and hydrology—is essential for researchers and scientists to establish environmental baselines, identify anthropogenic contamination, and develop effective remediation strategies. This technical guide examines how these natural factors govern water composition, providing a foundational context for discerning natural versus anthropogenic signatures in surface water research. Within the broader thesis of surface water degradation studies, isolating these natural controls enables more accurate assessment of human impact and informs regulatory frameworks for water resource management.

Climate Controls on Water Composition

Climate fundamentally governs water composition through its influence on temperature, precipitation patterns, and evaporation processes. These factors collectively control the rates of chemical weathering, dilution of contaminants, and concentration of solutes in aquatic systems.

Table 1: Climate-Mediated Influences on Water Quality Parameters

| Climate Factor | Affected Water Parameter | Direction of Influence | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Positive correlation (r=0.40) [1] | Increased microbial metabolism and organic matter decomposition |

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) | Positive correlation (r=0.50) [1] | Enhanced chemical oxidation rates | |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | Positive correlation (r=0.38) [1] | Accelerated organic matter breakdown | |

| Precipitation Seasonality | Nitrate-Nitrogen (NO₃-N) | Higher in wet season [2] | Increased agricultural runoff transporting fertilizers |

| Escherichia coli | Higher in dry season [2] | Reduced dilution of wastewater inputs | |

| Total Suspended Solids (TSS) | Higher in dry season [2] | Lower flows reducing sediment transport capacity | |

| Drought Conditions | Electrical Conductivity | Increase [2] | Evaporative concentration of dissolved ions |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Cu) | Increase [2] | Reduced dilution of anthropogenic inputs |

Climate change introduces additional complexity to these relationships. Projected disruptions to the hydrological cycle include more severe wet-dry fluctuations, enhanced evapotranspiration, and reduced precipitation in many regions, leading to increased likelihood of hydrological drought and water scarcity [3]. These changes directly affect water composition by altering solute concentrations and biogeochemical processing rates.

Geological Controls on Water Composition

Bedrock geology and weathering processes fundamentally determine the natural chemical signature of surface waters through the release of elements and compounds from the lithosphere to the hydrosphere. Water-rock interactions control the baseline concentrations of major ions, trace elements, and natural contaminants in aquatic systems.

Table 2: Geogenic Factors Governing Surface Water Composition

| Geological Factor | Influence on Water Composition | Representative Parameters | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock Type & Mineralogy | Determines solute availability through weathering | Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, SiO₂ | Establishes regional geochemical baselines |

| Soil Composition & Redox Conditions | Controls metal mobilization and speciation | Fe, Mn, As, Cr | Explains natural heavy metal occurrences |

| Geological Structure & Fractures | Creates preferential flow paths and contaminant pathways | Connectivity indices, hydraulic conductivity | Influences non-point source pollution vulnerability |

| Hyporheic Exchange | Governs biogeochemical processing at sediment-water interface | DO, NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺, DOC | Affects natural attenuation capacity |

The geological framework establishes the natural background against which anthropogenic pollution must be assessed. In China's river basins, watershed slope accounted for 17.40% of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and dissolved oxygen (DO) variations in natural watersheds, reflecting how topography and geological setting influence water quality through erosion potential and drainage characteristics [4]. Similarly, in the Arno River Basin (Italy), natural geological contributions to water chemistry must be quantified before anthropogenic impacts can be accurately assessed [5].

Geological factors also interact with anthropogenic disturbances. In the Jishan River study, while anthropogenic inputs were the primary concern, the underlying geological environment shaped how these pollutants were transported and transformed [6]. The geological template thus provides the foundational canvas upon which anthropogenic influences are superimposed.

Hydrological Controls on Water Composition

Hydrological processes integrate climate and geological influences while adding unique transport and dilution dynamics that fundamentally control water composition. Flow regime, surface water-groundwater interactions, and hydrological connectivity determine the fate and distribution of dissolved and particulate constituents in aquatic systems.

Flow velocity and discharge rates directly influence physicochemical parameters through multiple mechanisms. In the Radiowo landfill study, surface water flow showed a moderate negative correlation with pH (r = -0.44) and a moderate positive correlation with copper concentration (r = 0.47) downstream of the landfill site [1]. These relationships demonstrate how hydrological factors can either mitigate or exacerbate pollutant impacts depending on specific catchment conditions.

The hyporheic zone—where surface and groundwater mix beneath and alongside river channels—represents a critical hydrological interface governing water composition. In this zone, biogeochemical processes including nitrification, denitrification, and organic matter degradation naturally modify water chemistry through microbial activity and chemical transformations [7]. The efficiency of these natural attenuation processes is directly controlled by hydrological factors including residence time, flow paths, and exchange rates.

Climate-induced hydrological changes are altering fundamental water composition patterns globally. Multi-year hydrological droughts, characterized by prolonged reductions in river flow, are becoming more frequent and severe under anthropogenic climate change [3]. These extended low-flow conditions reduce contaminant dilution capacity and increase pollutant concentrations, potentially leading to water quality degradation even without additional pollutant loading.

Methodologies for Disentangling Natural and Anthropogenic Influences

Experimental Design and Monitoring Protocols

Comprehensive water quality assessment requires rigorous monitoring protocols capable of discriminating natural variability from anthropogenic signals. The methodology employed in the Radiowo landfill study exemplifies a robust approach, with surface water samples collected quarterly (March, June, September, November) over a twelve-year period at multiple monitoring points along a watercourse [1]. This long-term, spatially replicated design enables researchers to distinguish site-specific anthropogenic impacts from seasonal and interannual natural variability.

Essential monitoring parameters should include both conventional water quality indicators and specific tracers of human activity:

- Physicochemical parameters: pH, electrical conductivity (EC), temperature, dissolved oxygen

- Major ions: Cl⁻, NH₄⁺, SO₄²⁻, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, HCO₃⁻

- Organic matter indicators: BOD₅, CODCr, TOC

- Nutrients: NO₃-N, NH₄-N, PO₄³⁻

- Heavy metals: Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Hg

- Microbiological indicators: E. coli, coliform bacteria

- Flow metrics: discharge, water level, flow velocity

Analytical and Statistical Framework

Multivariate statistical analysis provides powerful tools for identifying patterns and sources of variation in complex water quality datasets. Principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis can discriminate between natural and anthropogenic influences by identifying covarying parameters and grouping sampling sites with similar characteristics [1] [8].

Water quality indices offer integrative approaches for assessing overall water quality status. The Water Quality Index (WQI) and Comprehensive Pollution Index (CPI) used in the Radiowo study transform complex multi-parameter data into simplified scores that facilitate spatial and temporal comparisons [1]. In this application, WQI values ranging from 63.06 to 96.84 and CPI values from 0.56 to 0.88 indicated generally good water quality with low pollution levels, providing quantitative support for environmental assessment.

Emerging methodologies include the T-NM index, which quantifies asymmetric human amplification and suppression effects on water quality trends [4]. This approach identified that anthropogenic drivers intensified or attenuated natural seasonal trends by 22-158% and 14-56% respectively across Chinese watersheds, with particularly strong effects during summer months.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Solutions for Water Composition Studies

| Reagent/Category | Application in Water Analysis | Technical Function | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Chromatography Standards | Quantification of major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻) and cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, NH₄⁺) | Calibration and quantification | Certified reference materials, multi-point calibration curves |

| Heavy Metal Standards | Analysis of trace metals (Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Hg) by ICP-MS/AAS | Instrument calibration and accuracy verification | Acid preservation to prevent adsorption, matrix-matched standards |

| Organic Carbon Analysis | Determination of TOC, BOD, COD | Oxidation of organic compounds, microbial respiration measurement | Blank correction, glucose-glutamic acid verification for BOD |

| Microbiological Media | Enumeration of E. coli, coliforms, heterotrophic bacteria | Microbial indicator culture and quantification | Sterilization validation, positive/negative controls |

| pH/EC Buffers & Standards | Calibration of field meters for pH, conductivity, salinity | Sensor calibration and measurement accuracy | Temperature compensation, regular calibration protocols |

| Preservation Reagents | Sample stabilization for various parameters | Prevention of biological/chemical changes between collection and analysis | Parameter-specific preservation (e.g., HNO₃ for metals, cold storage for nutrients) |

Natural factors comprising climate, geology, and hydrology establish the foundational template governing surface water composition through complex, interacting mechanisms. Climate controls temperature-dependent biogeochemical processes and precipitation-driven dilution-concentration dynamics. Geology determines the natural geochemical baseline through rock weathering and element mobilization. Hydrology integrates these influences through flow-mediated transport and transformation processes. Understanding these natural governing factors provides the essential scientific basis for discriminating anthropogenic water quality impacts—a critical requirement for effective water resource management, pollution remediation, and policy development in an era of increasing human pressure on global freshwater resources.

The degradation of surface water quality represents a critical challenge at the nexus of environmental science and public health. Within research on water quality dynamics, a fundamental dichotomy exists between natural processes and anthropogenic pressures. While climate, geology, and hydrological cycles establish baseline water conditions, human activities increasingly superimpose a distinct contamination signature upon aquatic ecosystems. This technical guide examines the anthropogenic footprint through the lens of three primary contributors: agricultural, industrial, and urban runoff. These pathways transport complex mixtures of nutrients, heavy metals, synthetic organic compounds, and particulate matter from terrestrial environments into surface waters, fundamentally altering their physicochemical and biological integrity. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for researchers developing monitoring protocols, remediation strategies, and predictive models for aquatic system management.

Quantitative Data on Anthropogenic Contaminants

The systematic monitoring of surface waters provides critical quantitative evidence of anthropogenic impact. The following tables summarize key findings from recent global studies, highlighting contamination levels, spatial and temporal trends, and associated environmental indices.

Table 1: Heavy Metal Pollution in River Sediments and Associated Health Risks (Pearl River Delta and Huaihe River Basin Studies)

| Parameter | Pearl River Delta Findings [9] | Huaihe River Basin Findings [10] | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Pollution | Most Heavy Metal (HM) contents greatly exceeded local background values; Cd had the highest pollution level. | Cr presented the highest carcinogenic risk, affecting >99.8% of adults and children at levels >1×10⁻⁶. | |

| Key Anthropogenic Sources | Electroplating industry was a common source for Cr, Cu, and Zn. | Cd, Cr, and Pb were mainly affected by industrial activities (e.g., local textile industries). As was influenced by agriculture and transportation. | Source apportionment is critical for targeted management. |

| Dominant Influencing Factor | Temperature was the dominant natural factor for HM distribution (influence degree: 0.68–0.97). | The interaction of Precipitation and Road Network Density on As was highly significant (explanatory power: 0.673). | Geodetector method reveals interaction strengths. |

| Health Risk Assessment | - | Adults had higher carcinogenic risk; children had higher non-carcinogenic risk. | Risk varies by demographic; essential for public health planning. |

Table 2: Seasonal Water Quality Trends and Organic Pollution in Managed Watersheds (China National Study) [4]

| Parameter | Long-term Trend (2006-2020) | Seasonal Anomaly (Summer) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) | 61.1% of watersheds showed decreasing trend (35.2% significant). National avg. change: -1.57 mg/L/decade. | Only 12.3% of watersheds showed significant decrease in summer (vs. 17.9-22.5% in other seasons). 7.6% showed significant increases. | Improvement overall, but summer resilience is weaker, indicating heightened seasonal anthropogenic pressure. |

| DO (Dissolved Oxygen) | 64.7% of watersheds showed increasing trend (26.4% significant). National avg. change: +0.93 mg/L/decade. | 9.2% of watersheds showed significant DO reductions in summer. | Despite overall improvement, seasonal oxygen deficits emerge, linked to temperature and organic pollution. |

| Primary Driver Identification | - | In managed watersheds, Shannon Diversity Index (11.58%) and Largest Patch Index (10.66%) dominated COD/DO changes. | Landscape patterns (anthropogenic factors) dominate over natural factors (e.g., rainfall, slope) in managed basins. |

Table 3: Water Quality and Pollution Index Analysis near a Municipal Landfill (Radiowo Landfill Study) [1]

| Index/Parameter | Findings at Monitoring Points | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Water Quality Index (WQI) | Average values ranged from 63.06 to 96.86. | Indicates "Good" to "Very Poor" water quality across the site [1]. |

| Comprehensive Pollution Index (CPI) | Average values ranged from 0.56 to 0.88. | Classified as "Low Pollution" level. |

| Key Correlated Parameters | Significant correlations observed between EC, Cl⁻, NH₄⁺, BOD₅, CODCr, and TOC. | Suggests a common origin, likely landfill leachate, influencing organic compound contamination. |

| Influence of Temperature | Temperature had greater influence on physicochemical parameters than precipitation (correlations with BOD₅, CODCr, TOC: 0.40, 0.50, 0.38). | Warming can enhance microbial activity and decomposition, exacerbating organic pollution. |

Experimental Protocols for Source Apportionment and Impact Assessment

Geodetector Statistical Method for Source Analysis

Application: This method quantitatively assesses the influence of natural and anthropogenic factors on the spatial distribution of pollutants, such as heavy metals in sediments or water [9] [10]. It is particularly valuable for identifying interactive effects between factors.

Detailed Workflow:

- Factor Selection: Define and collect spatial data for potential influencing factors (e.g., X).

- Spatial Stratification: Discretize the continuous data of each factor into appropriate layers or strata using professional knowledge or classification algorithms (e.g., natural breaks).

- q-Statistic Calculation: The Geodetector calculates a q-value to measure the explanatory power of a factor (X) for the spatial heterogeneity of the pollutant (Y).

- Formula: ( q = 1 - \frac{\sum{h=1}^{L} Nh \sigma_h^2}{N \sigma^2} )

- Where:

- ( h = 1, ..., L ) is the stratification of variable Y or factor X.

- ( Nh ) and ( N ) are the number of units in stratum h and the entire region.

- ( \sigmah^2 ) and ( \sigma^2 ) are the variances of Y in stratum h and the entire region.

- The q-value falls within [0, 1], where a larger value indicates that factor X explains more of the spatial distribution of Y [9].

- Interaction Detection: Evaluate whether two factors, X1 and X2, interact to enhance or weaken the explanation of Y. The types of interaction (e.g., nonlinear enhance, bi-enhance, independent) are determined by comparing q(X1∩X2) with q(X1) and q(X2).

- Interpretation: Identify the dominant factors and their interactions. For example, a study found that the individual explanatory powers of Precipitation and Road Network Density on Arsenic (As) were 0.362 and 0.189, respectively, but their interaction yielded a much higher explanatory power of 0.673, revealing a significant indirect anthropogenic pathway [10].

Integrated Modeling of Urban Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Pollution

Application: This protocol projects the spatiotemporal dynamics of anthropogenic water pollution, including conventional pollutants and pharmaceuticals, under future climate change and urbanization scenarios [11].

Detailed Workflow:

- Scenario Definition: Establish future scenarios by integrating:

- Climate Projections: From General Circulation Models (GCMs) for parameters like rainfall intensity and frequency.

- Socioeconomic Projections: Using Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) to model urbanization, land-cover change, and population growth [11].

- Hydraulic and Water Quality Modeling:

- Utilize the Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) or an equivalent platform.

- Hydraulic Module: Simulates precipitation, runoff generation, infiltration, and one-dimensional pipe flow within the combined sewer system.

- Water Quality Module: Builds upon the hydraulic results to simulate the buildup, washoff, and transport of pollutants (e.g., suspended solids, COD, pharmaceuticals). This often involves defining exponential buildup functions and washoff equations based on runoff rate [11].

- Model Calibration and Validation: Use historical monitoring data of flow and pollutant concentrations to calibrate model parameters (e.g., roughness, accumulation rates) and validate model performance.

- Spatiotemporal Analysis and GIS Mapping:

- Run the calibrated model with future scenario data.

- Use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map the outputs, identifying hotspots of high-frequency CSO events (often in highly-impervious areas) and high-load discharges (often in densely-populated areas) [11].

- Analyze temporal variability, including future seasonal anomalies of discharged loads.

- Uncertainty Analysis: Employ confidence intervals (e.g., 95% CI) to quantify uncertainties in the projections, particularly for complex pollutants like pharmaceuticals [11].

Analytical Framework and Conceptual Workflow

The investigation of anthropogenic footprints in surface waters requires a structured approach that connects emission sources, transport pathways, and analytical techniques. The diagram below visualizes this comprehensive research framework.

Diagram 1: Research framework for analyzing anthropogenic footprints in surface waters. The workflow traces the path from major anthropogenic sources and their signature pollutants through transport pathways to key analytical methods and final research outputs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for conducting field and laboratory research on anthropogenic water pollution.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Water Pollution Studies

| Category | Item | Technical Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Sampling | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Bottles | Chemically inert containers for collecting and storing water samples to prevent contamination and adsorption of pollutants [1] [10]. |

| 0.22-μm Aqueous Filter Membranes | Used for field-filtration of water samples intended for metal analysis to remove suspended particulates and bacteria [10]. | |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃), Trace Metal Grade | Added to filtered water samples to acidify them (pH < 2), preventing adsorption of heavy metals to container walls and preserving sample integrity [10]. | |

| Portable GPS Device | Precisely records the coordinates of sampling points for spatial analysis and monitoring network design [10]. | |

| Portable pH and DO Meters | Enables on-site measurement of critical parameters (pH, Dissolved Oxygen) that can change during sample transport and storage [10]. | |

| Laboratory Analysis | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Provides ultra-sensitive multi-element analysis for quantifying trace heavy metals (As, Cd, Cr, Pb, Hg) in water and sediment samples [9] [10]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Identifies and quantifies specific organic pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides, and pharmaceutical residues [1] [11]. | |

| Reagents for COD (Cr- based) | Potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) and other reagents are used in the closed reflux method to chemically oxidize and measure the amount of organic matter in water [10]. | |

| Reagents for BOD₅ | Used for diluting samples and measuring the oxygen consumed by microorganisms over 5 days to assess the concentration of biodegradable organic wastewater [10]. | |

| Data Analysis & Modeling | Geodetector Software | A statistical tool for assessing the stratified heterogeneity of environmental data and quantitatively detecting the drivers of pollutant spatial distribution [9] [10]. |

| Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) | An open-source dynamic hydrology-hydrology water quality simulation platform used for modeling urban runoff and combined sewer overflows (CSOs) [11]. | |

| R or Python with Statistical Packages | Programming environments used for multivariate statistical analysis, trend analysis, positive matrix factorization (PMF), and creating custom data visualizations [9] [4]. |

Water pollution occurs when harmful substances contaminate a water body, degrading water quality and rendering it toxic to humans or the environment. For regulatory and scientific purposes, these pollution sources are broadly categorized into two distinct types: point sources and non-point sources [12] [13].

A point source is any single, identifiable source of pollution from which contaminants are discharged, such as a pipe, ditch, factory, or wastewater treatment plant [14] [12]. The U.S. Clean Water Act defines a point source as "any discernible, confined, and discrete conveyance, including but not limited to any pipe, ditch, channel, tunnel, conduit, well, discrete fissure, container, rolling stock, concentrated animal feeding operation, or vessel or other floating craft, from which pollutants are or may be discharged" [14]. These sources are typically regulated through permit systems.

In contrast, non-point source (NPS) pollution does not originate from a single discrete source. It is caused by rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground, picking up natural and human-made pollutants along the way, and finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters, and groundwater [14]. Nonpoint pollution is inherently diffuse and tied to land use, making it more difficult to control than point source pollution.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Point and Non-Point Pollution Sources

| Characteristic | Point Source Pollution | Non-Point Source Pollution |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Single, identifiable source [12] | Multiple, diffuse sources across a landscape [14] |

| Discharge Pattern | Constant, continuous, or predictable | Intermittent, closely related to precipitation events [14] |

| Examples | Factories, sewage plants, wastewater pipes [14] [12] | Agricultural runoff, urban stormwater, forestry operations [14] |

| Primary Pollutants | Industrial chemicals, treated/untreated sewage | Excess fertilizers, pesticides, oil, grease, sediment [14] |

| Regulatory Control | Directly regulated through permit systems | Managed through land-use planning and best practices [14] |

Contaminant Pathways to Aquatic Systems

Understanding how contaminants travel from their source to aquatic receptors is critical for risk assessment and mitigation. An exposure pathway is the course a contaminant takes from a source to a receptor and must include five elements: a contaminant source, an environmental transport medium, an exposure point, an exposure route, and a receptor [15].

Site Conceptual Model for Exposure Pathways

Developing a site conceptual model is a recommended approach to visualize how contaminants move in the environment and how people or ecological receptors might come into contact with them [16]. The following diagram illustrates a generalized conceptual model for contaminant pathways from point and non-point sources to aquatic systems.

Contaminant Pathways Conceptual Model

Key Transport Mechanisms

Land Runoff and Hydrologic Modification: Precipitation moves over and through the ground, picking up and carrying away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into water bodies [14]. This is the primary mechanism for non-point source pollution.

Atmospheric Deposition: Air pollutants can be deposited into water bodies directly or through precipitation, making the atmosphere a significant transport medium for some contaminants [14].

Subsurface Flow and Hyporheic Exchange: Contaminants in groundwater can discharge into surface waters, while simultaneous exchange occurs between stream water and groundwater in the saturated sediment lateral to the stream, known as the hyporheic zone [7]. This process can facilitate the transfer of contaminants between surface and groundwater systems.

Quantitative Analysis of Key Contaminants

Advanced analytical techniques are essential for detecting and quantifying contaminants in aquatic systems. Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has become a cornerstone technology for this purpose, enabling the detection of contaminants at very low concentrations (nanograms to micrograms per liter) [17].

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Analysis of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs)

A comprehensive study screened for 165 Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) in water, sediment, and biota using the following methodology [17]:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for CEC Analysis in Aquatic Matrices

| Protocol Step | Detailed Methodology | Purpose/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Water, sediment, and fish samples collected from various sites, including areas near a Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP). | To obtain representative environmental matrices from potential contamination hotspots. |

| Sample Preparation | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) for water samples; pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) for sediment and biota. | To concentrate target analytes and remove matrix interferences that could affect analysis. |

| Instrumental Analysis - Screening | Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). | Initial targeted screening for the 165 pre-defined CECs. |

| Confirmation Analysis | High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) for compounds without available analytical standards. | To provide accurate mass confirmation for suspect screenings where standards are unavailable. |

| Quantitative Analysis | Use of analytical standards for detected compounds to generate concentration data. | To obtain precise quantitative data for risk assessment calculations. |

| Quality Assurance/Quality Control | Use of procedural blanks, matrix spikes, and internal standards. | To ensure analytical accuracy, precision, and account for matrix effects or recovery losses. |

Representative Quantitative Data from Environmental Monitoring

The application of such protocols yields critical quantitative data on contaminant presence and concentration, which forms the basis for risk assessment.

Table 3: Measured Concentrations of Selected CECs in Different Environmental Matrices [17]

| Contaminant | Class | Water (ng L⁻¹) | Sediment (μg kg⁻¹) | Biota (μg kg⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine | Stimulant | 4.02 – 15.03 | 55.89 | Not Detected |

| Ciprofloxacin | Antibiotic | 6.05 | Not Specified | 2.94 – 4.18 |

| Clindamycin | Antibiotic | 6.04 – 7.01 | Not Specified | Not Detected |

| Diclofenac | Anti-inflammatory | 1.36 – 2.20 | Not Specified | Not Detected |

Table 4: Global Distribution and Characteristics of Microplastics in Inland Waters [18]

| Parameter | Reported Value or Prevalence | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Abundance Range | 0.00 – 4,275,800.70 items m⁻³ | Extreme variation across global datasets. |

| Mean Abundance | 25,255.47 ± 132,808.40 items m⁻³ | High standard deviation indicates significant variability. |

| Most Common Colors | Transparent (29.27%), Black (9.21%), Blue (8.02%) | - |

| Most Common Shapes | Fibers (38.25%), Fragments (13.28%), Films (3.84%) | Fibers dominate microplastic pollution. |

| Size Distribution | ≤1 mm particles constitute 63.72% | Small particles pose greater ecological risk. |

| Primary Polymer Types | Polyester (15.90%), Polypropylene (13.90%), Polyethylene Terephthalate (5.10%) | Reflects common use in textiles and packaging. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The analysis of aquatic contaminants requires a suite of specialized reagents, standards, and materials to ensure accurate and reproducible results.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Aquatic Contaminant Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Used as mobile phases in chromatography to separate analytes without introducing interference. | Acetonitrile (ACN), Methanol (MeOH) from JT Baker Chemical Co. [17]. |

| Acid Modifiers | Added to mobile phases to improve chromatographic separation and ionization efficiency in MS. | Formic Acid (FA), Acetic Acid (AA) provided by Tedia Co. [17]. |

| Analytical Standards | Pure reference materials used to identify and quantify target contaminants via calibration curves. | Commercially available standards for pharmaceuticals, pesticides, etc. [17]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | To concentrate trace-level contaminants from water samples and clean up complex sample matrices. | Widely used for pre-concentration of CECs in water samples prior to LC-MS/MS [17]. |

| Internal Standards | Isotope-labeled analogs of target analytes added to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization. | Essential for achieving accurate quantification in complex environmental matrices [17]. |

The distinction between point and non-point sources is fundamental to understanding anthropogenic impacts on aquatic systems. While point sources were historically the primary regulatory focus, non-point sources like agricultural runoff and urban stormwater are now recognized as the leading causes of water quality impairments [14]. The pathways these contaminants follow—through runoff, atmospheric deposition, sediment transport, and food web accumulation—create complex exposure scenarios that challenge traditional management approaches.

Quantitative data reveals that contaminants of emerging concern, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and microplastics, are pervasive in global water bodies, often at levels posing ecological risks [17] [18]. The experimental methodologies outlined provide the necessary toolkit for researchers to monitor these pollutants, while conceptual models of exposure pathways offer a framework for assessing risk and targeting interventions. This scientific foundation is critical for informing the broader thesis that effective mitigation of surface water degradation requires an integrated approach addressing both natural hydrological processes and diverse anthropogenic factors, from industrial discharges to land-use practices.

Surface water quality serves as a critical indicator of environmental health, reflecting the complex interplay between natural processes and anthropogenic influences. While natural factors such as geological weathering, volcanic activity, and biological processes contribute to water composition, human activities have introduced a distinct chemical signature characterized by three prominent pollutant classes: herbicides, nutrients, and heavy metals. These contaminants represent a fundamental shift in aquatic systems, originating primarily from agricultural intensification, industrial expansion, and urbanization. This technical review examines the sources, transport mechanisms, ecological impacts, and analytical methodologies for these signature pollutants, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for discriminating anthropogenic from natural influences in water quality degradation research.

The imperative to distinguish human-caused pollution from natural background levels has never been more pressing. Global assessments indicate that over 2 billion people live in water-stressed countries, with water quality further compromised by contamination [19]. Industrial and agricultural wastewater management remains inadequate in many regions, resulting in the release of insufficiently treated effluents containing toxic metals, pesticide residues, and nutrient loads that disrupt aquatic ecosystem function [20] [21]. This review synthesizes current research on these pollutant classes, with particular emphasis on their synergistic effects, advanced detection methods, and mechanistic pathways of toxicity.

Herbicides: Agricultural Signature with Aquatic Consequences

Silvicultural and agricultural practices constitute primary sources of herbicide introduction to aquatic systems. Modern forestry operations typically apply herbicides at lower frequencies (1-2 application events per 30-80 year rotation) compared to agricultural uses, yet concerns persist regarding non-target impacts on aquatic ecosystems [22]. Commonly used compounds include glyphosate, clopyralid, triclopyr, 2,4-D, sulfometuron methyl (SMM), and metsulfuron methyl (MSM). These herbicides enter water bodies through spray drift during application, surface runoff following precipitation events, and through groundwater infiltration, with mobilization dynamics dependent on product solubility, soil sorption potential, climatic conditions, topography, and soil properties [22].

Recent monitoring studies demonstrate that aerial application of forestry herbicides results in only trace, episodic concentrations in surface waters, with detections consistently below human health safety benchmarks. For instance, maximum SMM and MSM detections (≤0.030 μg/L) occurred during the first storm event following application at sampling locations closest to treated areas [22]. Critical abiotic factors influencing herbicide presence and concentration include proximity to treatment sites, time from application, and rainfall patterns, highlighting the importance of hydrological connectivity in pollutant transport.

Toxicity Mechanisms and Methodological Approaches

Herbicides exert toxic effects on aquatic biota through multiple mechanistic pathways, with fish serving as sensitive indicator species. The primary modes of action include:

Oxidative Stress: Herbicides induce production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), causing oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA. This imbalance overwhelms antioxidant defenses, leading to lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and DNA fragmentation [23]. Marker compounds such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) provide quantitative measures of this damage.

Neurotoxicity: Many herbicides, particularly organophosphates and carbamates, inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme essential for neurotransmission. This inhibition results in acetylcholine accumulation, leading to neuromuscular dysfunction, convulsions, and potentially death [23] [24]. Standardized protocols for AChE activity assessment in brain and muscle tissues provide a robust biomarker for this effect.

Endocrine Disruption: Certain herbicide formulations interfere with hormonal systems, altering reproductive function and development. These effects may manifest as vitellogenin induction in male fish, altered steroid hormone levels, or impaired gonadal development [23].

Immunosuppression: Herbicide exposure can suppress both innate and adaptive immune responses in aquatic organisms, reducing resistance to pathogens through mechanisms including reduced phagocytic activity, lymphocyte proliferation, and antibody production [23].

Table 1: Experimental Biomarkers for Assessing Herbicide Toxicity in Aquatic Organisms

| Toxicity Mechanism | Biomarker | Analytical Method | Tissue Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress | Lipid peroxidation (MDA) | TBARS assay | Liver, gills |

| Protein carbonyl content | DNPH method | Liver, muscle | |

| DNA damage (8-OHdG) | ELISA, HPLC-ECD | Whole blood, liver | |

| Antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) | Spectrophotometric activity assays | Liver, gills, kidney | |

| Neurotoxicity | Acetylcholinesterase activity | Ellman method | Brain, muscle |

| Endocrine Disruption | Vitellogenin | ELISA | Blood plasma |

| Steroid hormones | Radioimmunoassay | Blood plasma, gonads | |

| Immunotoxicity | Phagocytic activity | Flow cytometry | Head kidney, blood |

| Lysozyme activity | Turbidimetric assay | Blood plasma | |

| Respiratory burst | NBT reduction test | Blood, kidney |

Research Protocols for Herbicide Monitoring

A paired watershed design provides an optimal methodological framework for monitoring silvicultural herbicide impacts. The following protocol, adapted from recent studies, enables comprehensive assessment of herbicide transport and fate [22]:

Site Selection: Identify treated and reference watersheds with similar hydrological, geological, and ecological characteristics. Treatment watersheds should drain recently harvested forest lands treated with herbicides, while reference watersheds should lack recent herbicide application.

Sampling Design: Establish sampling sites upstream (immediately downhill of treated units) and downstream (near property boundaries) in treatment streams. Include intrawatershed control streams draining untreated areas and out-of-watershed negative control streams to account for legacy herbicide residues and spatial drift extent.

Temporal Sampling Strategy: Target predicted episodic pulses with collection intervals including:

- Pre-application baseline

- During aerial application

- Immediately post-application

- First three storm events >0.5 inches rainfall within 24 hours

- Extended post-treatment period to assess persistence

Analytical Methods: Utilize liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for multi-residue analysis with detection limits ≤0.01 μg/L. Include both parent compounds and major transformation products.

Data Analysis: Compare detections against human health safety benchmarks (e.g., 25,000-fold below chronic exposure thresholds for SMM and MSM) and ecological effect concentrations.

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of Herbicide Toxicity in Aquatic Organisms. This pathway illustrates the primary biochemical routes through which herbicides impact fish health, from initial exposure to population-level consequences.

Nutrient Pollution: Eutrophication and Ecosystem Transformation

Anthropogenic Nutrient Enrichment Dynamics

Nutrient pollution, primarily from nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, represents one of the most widespread and challenging environmental problems affecting aquatic ecosystems globally. These nutrients enter water bodies through multiple anthropogenic pathways, including agricultural runoff from fertilized fields, animal feeding operations, discharge from municipal wastewater treatment plants, and urban stormwater runoff [25]. The dramatic increase in nitrogen flux through rivers—10 to 15-fold greater in many regions compared to several decades ago—is driven largely by agricultural intensification and population growth [26].

The ecological consequences of nutrient enrichment extend beyond simple productivity increases. Excessive nutrient loading drives eutrophication, characterized by accelerated algal and microbial growth, which directly and indirectly alters ecological community composition and food web structure [26]. These changes manifest as shifts from sensitive insect taxa (e.g., mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies) to pollution-tolerant organisms (e.g., worms, snails, and midges), fundamentally restructuring aquatic communities [26].

Experimental Assessment of Nutrient Impacts

Ecological Network Analysis (ENA) provides a sophisticated methodological framework for quantifying how nutrient enrichment alters food web emergent properties. The following research protocol enables comprehensive assessment of nutrient impacts on riverine ecosystems [26]:

Site Selection Along Gradient: Identify study sites across a pronounced nutrient enrichment gradient, measuring dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) concentrations through regular monitoring (e.g., monthly samples over 7 years to establish robust baselines).

Community Characterization: Conduct comprehensive biological surveys to quantify:

- Algal and microbial biomass and composition

- Macroinvertebrate community structure using standardized sampling methods

- Fish population assessments and condition indices

Food Web Construction: Develop quantitative food webs using gut content analysis, stable isotope analysis (δ¹⁵N, δ¹³C), and literature data to establish trophic relationships and energy flows between species or trophic guilds.

Network Analysis Metrics: Calculate ENA indices including:

- Total System Throughput (TST): Sum of all energy flows in the system

- Finn's Cycling Index (FCI): Proportion of total flow that is recycled

- Average Path Length: Mean number of transfers between any two compartments

- System Omnivory Index: Degree of feeding across multiple trophic levels

Keystone Sensitivity Analysis: Develop indices that weight species' keystone properties (their influence on food web stability) by their sensitivity to specific disturbances (e.g., nutrient enrichment, floods) to predict ecosystem stability under different stressor scenarios.

Table 2: Food Web Emergent Properties Across a Nutrient Enrichment Gradient

| Network Metric | Oligotrophic Conditions | Mesotrophic Conditions | Eutrophic Conditions | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total System Throughput (TST) | Low (e.g., ~8.7M flow units) | Moderate | High (e.g., ~20.8M flow units) | Greater total energy movement through system |

| Finn's Cycling Index | Higher (>5%) | Moderate | Lower (<3%) | Reduced nutrient recycling efficiency |

| Average Path Length | Longer | Intermediate | Shorter | Simplified trophic transfer pathways |

| Community Respiration | Low | Moderate | Several times greater | Increased metabolic activity driving hypoxia risk |

| Trophic Cascade Strength | Stronger | Intermediate | Weaker | Dampened top-down control mechanisms |

| Robustness to Energy Flow Loss | Lower | Moderate | Higher | Greater resistance to random species loss |

| Vulnerability to Floods | Lower | Moderate | Higher | Structural changes increase flood sensitivity |

Nutrient Mitigation Through Microbial Processes

Emerging research highlights the potential of host-associated microbes in mitigating nutrient pollution impacts. Filter-feeding aquatic organisms such as oysters, mussels, and other bivalves support microbial communities that perform critical nutrient transformation functions [27]. Specifically, microbes in oyster guts and tissues can convert dissolved inorganic nitrogen (e.g., nitrate) into nitrogen gases through denitrification processes, effectively removing nitrogen from aquatic systems. Quantitative assessments reveal that oyster reefs represent significant denitrification hotspots, with substantial potential for reducing coastal nitrogen pollution [27].

Similar processes occur in freshwater systems, where snails, mussels, and aquatic insects host microbial communities that contribute to nitrogen transformation and emissions. These symbiotic relationships represent promising bioremediation approaches that leverage naturally occurring biological partnerships to address anthropogenic nutrient enrichment.

Heavy Metals: Persistent Metallic Legacies

Heavy metal contamination of aquatic systems has emerged as a major global environmental concern due to metals' toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation potential. Sources include both natural processes (volcanic eruptions, rock weathering, forest fires) and extensive anthropogenic activities [20] [21]. Industrial processes such as mining, smelting, electroplating, electronic device manufacturing, and fertilizer production release significant quantities of toxic metals including mercury, cadmium, lead, chromium, copper, and nickel into aquatic environments [21].

The chemical behavior and bioavailability of heavy metals in aquatic systems depend on their specific form and speciation. Metals can exist as free ions, complexed with organic or inorganic ligands, adsorbed onto particulate matter, or incorporated into biological tissues. Chelating agents such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), used in industrial and household detergents, can significantly enhance metal mobility and persistence in water by forming stable, soluble complexes that resist precipitation and degradation [28]. In municipal wastewater, substantial proportions of copper (approximately 60%) and nickel (>75%) exist as EDTA chelates, which are poorly removed during conventional treatment [28].

Toxicity Pathways and Health Risk Assessment

Heavy metals exert toxic effects through multiple mechanistic pathways, with impacts occurring even at low exposure concentrations due to bioaccumulation and biomagnification through food webs [20]. The primary toxicity mechanisms include:

Oxidative Stress Induction: Metals such as cadmium, chromium, and mercury catalyze production of reactive oxygen species, leading to lipid peroxidation, protein dysfunction, and DNA damage.

Enzyme Inhibition: Metals bind to protein sulfhydryl groups, disrupting enzyme function and critical biochemical pathways. For example, lead and cadmium exposure affects heme synthesis enzymes and disrupts calcium metabolism.

DNA Damage and Carcinogenicity: Several heavy metals cause genetic mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, and epigenetic changes that may initiate carcinogenic processes.

Neurotoxicity: Metals including lead, mercury, and manganese cross the blood-brain barrier, disrupting neurotransmitter function and causing neurological damage.

Endocrine Disruption: Certain metals interfere with hormonal signaling systems, altering reproductive function and development.

Human health risk assessment for heavy metals in water resources involves calculating exposure through ingestion, dermal contact, and inhalation routes. Key assessment metrics include the Hazard Quotient (HQ) for non-carcinogenic effects and Excess Cancer Risk for carcinogenic metals [20]. The Metal Index (MI) and Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI) provide integrated measures of overall metal contamination, incorporating multiple metals into single values to evaluate water quality status [20].

Table 3: Heavy Metal Sources, Health Effects, and Regulatory Benchmarks

| Heavy Metal | Primary Anthropogenic Sources | Major Health Effects | WHO/EPA Aquatic Life Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury (Hg) | Chlorine production, coal combustion, mining | Neurological damage, developmental defects | Varies by form (e.g., MeHg: 0.3 mg/kg in fish tissue) |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Electroplating, batteries, pigments | Kidney damage, osteoporosis, carcinogen | EPA: 1.8 μg/L (freshwater chronic) |

| Lead (Pb) | Leaded gasoline, paints, batteries | Neurological, cardiovascular, renal effects | EPA: 3.1 μg/L (saltwater chronic) |

| Copper (Cu) | Mining, electronics, antifouling paints | Liver damage, gastrointestinal distress | EPA: 3.1 μg/L (saltwater chronic) |

| Nickel (Ni) | Metal plating, alloys, batteries | Lung fibrosis, renal edema, dermatitis | EPA: 8.2 μg/L (saltwater chronic) |

| Arsenic (As) | Pesticides, wood preservatives, mining | Skin lesions, cardiovascular disease, cancer | WHO: 10 μg/L (drinking water) |

| Zinc (Zn) | Galvanization, rubber production, ointments | Anemia, pancreatic damage, infertility | EPA: 81 μg/L (freshwater chronic) |

Analytical Methods and Treatment Technologies

Advanced analytical techniques enable precise detection and quantification of heavy metals in aquatic environments. These include inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS), anodic stripping voltammetry, and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy [20]. For metal speciation analysis, techniques such as ion chromatography coupled with ICP-MS and synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy provide insights into chemical form and bioavailability.

Treatment technologies for heavy metal removal from wastewater include:

Physical Methods: Adsorption using biochar, activated carbon, or natural zeolites; membrane filtration (reverse osmosis, nanofiltration); ion exchange resins [21].

Chemical Methods: Chemical precipitation (hydroxide, sulfide); coagulation/flocculation; advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for breaking metal complexes; electrochemical treatment [21] [28].

Biological Methods: Phytoremediation; bioremediation using metal-transforming bacteria and fungi; constructed wetlands [27].

Ozonation has demonstrated efficacy for treating reverse osmosis concentrates containing metal complexes and pesticides. Applied at doses of approximately 1.18 mg O₃/mg DOC, ozone achieves significant degradation of metal-EDTA complexes (e.g., Ni-EDTA, Cu-EDTA) and pesticides (e.g., fipronil, imidacloprid), while also providing 5-log inactivation of viral indicators like MS2 bacteriophage [28]. When combined with alkaline precipitation (e.g., 300 mg/L CaO at pH 11), ozone pretreatment enhances nickel removal, offering a combined approach for addressing multiple contaminants in complex wastewater matrices [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Pollutant Analysis and Assessment

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Application | Function in Research | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNPH Reagent | Protein carbonyl detection | Derivatization of oxidized amino acid residues | Quantifying herbicide-induced protein oxidation in fish tissues |

| TBARS Assay Kit | Lipid peroxidation measurement | Colorimetric detection of malondialdehyde (MDA) | Assessing oxidative stress from metal exposure in liver tissues |

| Acetylthiocholine iodide | AChE activity assay | Enzyme substrate for Ellman method | Determining neurotoxicity of pesticides in fish brain homogenates |

| GSH/GSSG Assay Kit | Oxidative stress status | Quantification of reduced and oxidized glutathione | Evaluating antioxidant capacity in gill tissues after herbicide exposure |

| Vitellogenin ELISA Kit | Endocrine disruption screening | Quantification of egg yolk precursor protein in males | Detecting estrogenic effects of pollutant mixtures in fish plasma |

| Lysozyme Assay Kit | Immunotoxicity assessment | Measurement of innate immune function | Determining immunosuppressive effects of heavy metals in aquatic organisms |

| Stable Isotopes (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Trophic position analysis | Food web structure determination using SIA | Tracing nutrient pathways and biomagnification in polluted ecosystems |

| ICP-MS Standard Solutions | Metal quantification | Calibration for precise metal concentration measurements | Accurate determination of heavy metal levels in water and tissue samples |

Herbicides, nutrients, and heavy metals collectively represent a definitive chemical signature of human activity in aquatic ecosystems. Each pollutant class exhibits distinct transport pathways, transformation mechanisms, and ecological impacts that differentiate them from natural background constituents. The analytical frameworks, experimental protocols, and assessment methodologies presented in this review provide researchers with robust tools for quantifying these anthropogenic signatures and discriminating them from natural variability in water quality research.

Future research directions should prioritize understanding synergistic effects of multiple pollutant classes, developing advanced in situ monitoring technologies, and refining molecular indicators of sublethal stress in aquatic organisms. Additionally, exploration of nature-based solutions—including host-associated microbial communities for bioremediation and constructed wetlands for pollutant retention—offers promising approaches for mitigating the impacts of these signature pollutants. As global pressures on water resources intensify, the ability to accurately attribute degradation sources to either anthropogenic or natural factors becomes increasingly critical for effective environmental management and protection of aquatic ecosystem health.

Seasonal and Spatial Variability in Natural Water Quality Influences

The quality of surface water is not a static property but a dynamic interplay of natural processes and human activities, varying significantly across both space and time. For researchers and scientists engaged in environmental and drug development fields, understanding these patterns is crucial for risk assessment, study design, and interpreting water quality data. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the core principles and methodologies for analyzing seasonal and spatial variations in water quality, framed within the broader research context of distinguishing natural influences from anthropogenic degradation. Intense anthropogenic pressures, such as agricultural runoff, industrial discharge, and urban development, significantly alter land use patterns and introduce diverse pollutants into aquatic systems [29]. Simultaneously, natural factors including climate, geology, and hydrological cycles create a baseline upon which human impacts are superimposed [7]. This technical overview synthesizes current research to equip professionals with the tools to decipher these complex interactions.

Quantitative Data on Seasonal and Spatial Variations

Quantitative data reveals clear and measurable patterns in how water quality parameters change across seasons and geographical locations. The following tables consolidate findings from recent studies to facilitate easy comparison.

Table 1: Seasonal Variability of Key Water Quality Parameters

| Parameter | Observed Seasonal Pattern | Study Context | Hypothesized Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Ions (Cl⁻, Na⁺, SO₄²⁻) | Higher concentrations during the Dry Season (DS) compared to the Wet Season (WS) [30]. | Loukkos Estuary, Morocco [30]. | Reduced dilution from precipitation and increased marine influence during dry periods [30]. |

| Nutrients (TN, NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) | Substantially high concentrations in the dry season [29]. | Daliao & Shuangtaizi Rivers, China [29]. | Concentrated wastewater discharge and reduced river flow [29]. |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Pb, Fe) | Dominance order shifts from Fe > Pb during WS to Pb > Fe during DS, with HPI values indicating higher pollution in DS [30]. | Loukkos Estuary, Morocco [30]. | Combined influence of seasonal hydrology and constant anthropogenic sources (e.g., wastewater) [30]. |

| Organic Pollution (BOD, COD, TOC) | Correlated with ambient temperature, with higher values at elevated temperatures [1]. | Radiowo Landfill, Poland [1]. | Enhanced microbial activity and decomposition rates in warmer conditions [1]. |

Table 2: Spatial Variability and Correlation with Land Use

| Spatial Pattern | Correlated Land Use / Feature | Study Context | Key Associated Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downstream degradation | Increasing urban, industrial, and agricultural areas downstream [5]. | Arno River Basin, Italy [5]. | Chloride, Sodium, Sulphate [5]. |

| Decreasing gradient from downstream to upstream | Strong marine influence downstream; marked continental influence upstream [30]. | Loukkos Estuary, Morocco [30]. | Major ions (Cl⁻, Na⁺, SO₄²⁻) [30]. |

| Correlation with built-up areas | Building areas (urban land) [29]. | Songliao River Basin, China [29]. | Nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus) and Chlorophyll-a [29]. |

| Correlation with agricultural areas | Paddy fields and dryland [29]. | Songliao River Basin, China [29]. | Nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus) and Chlorophyll-a [29]. |

| Correlation with natural vegetation | Woodlands and wetlands [29]. | Songliao River Basin, China [29]. | Dissolved Oxygen (DO); generally improved water quality [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Water Quality Assessment

A robust assessment of spatiotemporal variability requires standardized protocols for field sampling, laboratory analysis, and data processing.

Field Sampling and Spatial Design

- Site Selection: Strategically select sampling sites to represent different hydrological positions (upstream, midstream, downstream) and dominant land use types within the watershed (e.g., forested, agricultural, urban) [29]. Using GIS hydrological tools to delineate drainage areas for each site is recommended [29].

- Temporal Frequency: Conduct sampling campaigns to capture key seasonal hydrological conditions, typically including wet (high flow), dry (low flow), and if relevant, an agricultural season [30] [29]. Sampling over multiple years strengthens trend analysis [1].

- In-Situ Measurements: At each site, measure physicochemical parameters directly in the field using calibrated portable meters. Core parameters include pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Dissolved Oxygen (DO), and water temperature [1].

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Collect water samples in appropriate containers following standard protocols (e.g., PN-ISO 5667-6:2016-12) [1]. Preserve samples on ice or with chemical preservatives (e.g., acidification for metal analysis) as required for subsequent laboratory analysis to prevent alteration of constituents [1].

Laboratory Analysis of Key Parameters

- Major Ions and Nutrients: Analyze concentrations of major anions (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻) and cations (Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺) using ion chromatography or other standard methods. Key nutrients include Ammonium (NH₄⁺), Nitrate (NO₃⁻), Nitrite (NO₂⁻), and Phosphate (PO₄³⁻), typically analyzed via colorimetric methods [30] [29].

- Heavy Metals: Determine concentrations of metals like Lead (Pb), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), and Iron (Fe) using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) [30] [29].

- Organic Pollution Indicators: Quantify the organic load through Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD₅), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD Cr), and Total Organic Carbon (TOC) using standardized laboratory procedures [1].

Data Processing and Index Calculation

Systematic analysis of the collected data is critical for interpretation. The workflow below outlines the key steps from raw data to actionable insights.

Diagram 1: Data Analysis Workflow

- Descriptive Statistics: Calculate measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, range) for all parameters to understand data distribution and identify potential outliers [31] [32].

- Pollution Indices: Synthesize multiple parameters into simplified indices for holistic assessment.

- Water Quality Index (WQI): Aggregates various parameters into a single score by assigning relative weights and quality rating scales, often classified as Excellent, Good, Poor, etc [1].

- Heavy Metal Pollution Index (HPI): Evaluates the combined effect of individual heavy metals relative to their permissible limits [30].

- Comprehensive Pollution Index (CPI): Another integrated measure used to classify pollution levels (e.g., low, moderate, high) [1].

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Employ techniques to uncover hidden patterns and relationships.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces data dimensionality to identify the key factors (components) responsible for most of the variance in the dataset, often distinguishing seasonal or spatial patterns [29].

- Redundancy Analysis (RDA): A canonical ordination technique used to directly relate water quality parameters to environmental variables (e.g., land use percentages, temperature), revealing the driving factors behind spatial patterns [29].

Visualizing Influences and Pathways

Understanding the complex interplay of factors affecting water quality is essential. The following diagram synthesizes the core relationships and pathways leading to spatiotemporal variability.

Diagram 2: Water Quality Variability Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials, reagents, and tools required for conducting comprehensive water quality variability studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Pre-Sterilized Sample Bottles | Collection and transport of water samples for microbial (e.g., E. coli) and organic analysis. Prevents cross-contamination [1]. |

| Acid-Washed HDPE Bottles | Collection and storage of samples for trace metal analysis. Acid-washing minimizes adsorptive losses and contamination [29]. |

| Chemical Preservatives | Added immediately after collection to stabilize specific analytes (e.g., HNO₃ for metals, ZnSO₄ for nutrients) [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used during laboratory analysis to ensure accuracy, precision, and quality control of the generated data [1]. |

| Multi-Parameter Portable Meter | For in-situ measurement of core physicochemical parameters: pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Dissolved Oxygen (DO), temperature [1]. |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) with Multispectral Camera | Remote sensing of spatial patterns in water quality parameters like turbidity and photosynthetic pigments (e.g., MicaSense RedEdge camera) [33]. |

| Ion Chromatography (IC) System | Laboratory analysis of major anion and cation concentrations (Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, etc.) [30]. |

| ICP-MS or AAS | Highly sensitive laboratory analysis of heavy metal concentrations at trace levels (Pb, Cd, Cr, Cu, etc.) [30] [29]. |

| GIS Software (e.g., ArcGIS) | Used for spatial analysis, including mapping sampling sites, delineating watersheds, and correlating water quality with land use data [29]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python, SPSS) | For performing descriptive statistics, calculating pollution indices, and running multivariate analyses (PCA, RDA) [31] [34] [29]. |

Measuring the Impact: Advanced Frameworks for Water Quality Assessment and Profiling

Water Quality Indices (WQIs) and Pollution Indices (PIs) are essential mathematical tools that transform complex water quality data into simple numerical values for comprehensive water quality assessment and communication. These indices help in strengthening water resource management and ensuring safe drinking water by providing a scientifically robust assessment framework [35]. The degradation of water resources, influenced by both natural processes (climate change, water-rock interactions, geological factors) and anthropogenic activities (industrialization, urbanization, agricultural practices), necessitates such comprehensive assessment tools [7]. While WQI models provide a holistic measure of overall water quality status, PI methods specifically quantify the extent of pollution deviation from established standards, serving complementary roles in water quality evaluation.

The fundamental purpose of these indices is to address the critical need for standardized water quality assessment amid growing threats to water security. With over five billion inhabitants globally dependent on groundwater and surface water systems for potable water, crop production, and manufacturing applications, the degradation of these resources poses significant threats to ecosystem stability and human health [7]. The application of WQI has increased significantly worldwide, though these models face persistent challenges related to parameter weighting, aggregation functions, and transparency that require ongoing methodological refinements [35].

Core Components of Water Quality Indices

Fundamental Structural Elements

All Water Quality Index models comprise five essential components that work in sequence to transform raw water quality measurements into meaningful index values:

- Indicator Selection: Identification of key water quality parameters that accurately reflect water condition

- Sub-index Transformation: Conversion of each parameter concentration into a standardized quality value (typically 0-100 scale)

- Parameter Weighting: Assignment of relative importance values to each parameter based on health and environmental significance

- Aggregation Function: Mathematical integration of weighted sub-indices into a single composite score

- Classification Scheme: Categorization of final index values into qualitative water quality classes [35]

The structural integrity of each component significantly influences the reliability and accuracy of the final water quality assessment. Uncertainties in WQI models primarily arise from parameter selection validity, weighting distribution, and aggregation function choice [35].

Comparison of Index Types and Their Applications

Table 1: Water Quality Index Types and Their Characteristics

| Index Type | Primary Function | Output Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall WQI | Holistic water quality assessment | 0-100 (typically) | General water quality status evaluation [35] |

| Pollution Index (PI) | Quantify pollution level relative to standards | Variable by method | Identify pollution severity [36] |

| Said-WQI | Simplified water quality categorization | 0.67-2.34 (categorical) | Rapid water quality screening [36] |

| Overall Index of Pollution (OIP) | Comprehensive pollution assessment | 3.71-11.20 (classified) | Multi-parameter pollution evaluation [36] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Standard WQI Development Workflow

The development and application of Water Quality Indices follow systematic experimental protocols that ensure scientific rigor and reproducibility. The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for WQI development and application:

Parameter Selection and Weighting Methodologies

Parameter selection represents a critical first step in WQI development, with advanced statistical and machine learning approaches increasingly supplementing traditional expert judgment:

Feature Selection using Machine Learning: The XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) algorithm combined with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has demonstrated superior performance in identifying critical water quality indicators. This method involves (1) initial training of the XGBoost model on the complete dataset to rank features by importance, (2) iterative elimination of unimportant features through recursion, and (3) retraining the model with filtered features to finalize parameter selection [35]. This approach achieved 97% accuracy for river sites with a logarithmic loss of only 0.12 in Danjiangkou Reservoir case studies [35].

Weighting Techniques: The Relative Weighting Method and Rank Order Centroid (ROC) approach represent two prominent weighting strategies. Research indicates that coupling the Bhattacharyya mean WQI model (BMWQI) with the ROC weighting method significantly outperforms other WQI models in reducing uncertainty, showing eclipsing rates for rivers and reservoirs at 17.62% and 4.35%, respectively [35].

Index Aggregation and Calculation Methods

Standard WQI Calculation: Traditional WQI models employ linear aggregation functions to combine weighted sub-indices. The general formula follows:

[ WQI = \sum{i=1}^{n} (wi \times q_i) ]

Where ( wi ) represents the weight of parameter i, ( qi ) represents the quality rating of parameter i, and n represents the number of parameters [35] [37].

Pollution Index (PI) Method: The PI approach uses a different mathematical foundation, typically employing the worst-case assessment principle:

[ PI = \sqrt{\frac{(Ci/Li)^2{max} + (Ci/Li)^2{avg}}{2}} ]

Where ( Ci ) represents measured concentration of parameter i, and ( Li ) represents permissible limit for parameter i [36].

Comparative Performance of Aggregation Functions: Research has identified eight distinct aggregation functions with varying performance characteristics. A comparative optimization framework evaluating these functions demonstrated that the newly proposed Bhattacharyya mean WQI model (BMWQI) coupled with ROC weighting significantly reduced model uncertainty compared to conventional approaches [35].

Advanced Modeling Techniques and Machine Learning Applications

Machine Learning Optimization of WQI Models

Recent advances have integrated machine learning algorithms to enhance WQI accuracy and efficiency while reducing operational costs and complexity:

Algorithm Performance Comparison: Research comparing Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Ensemble Regression (ER), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Regression Tree (RT), and Kernel Approximation Regression (KAR) demonstrated that GPR, ER, SVM, and RT models achieved over 96% prediction accuracy for AQI (a parallel air quality index), while KAR showed lower accuracy at 82.36% [38]. The GPR model particularly excelled with minimum Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.87 and 1.219 during training and testing phases respectively [38].

Hybrid Optimization Approaches: The integration of Genetic Algorithm Particle Swarm Optimization (GAPSO) with WQI has emerged as an effective method for assessing contributions from potential pollution sources. This approach combines the global search capability of genetic algorithms with the local search efficiency of particle swarm optimization, demonstrating feasibility and reliability for pollution source attribution in river systems [37].

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in Environmental Index Modeling

| Algorithm | Application | Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost with RFE | Feature selection for WQI | 97% accuracy, log loss: 0.12 [35] | Superior prediction performance, lower error |

| Gaussian Process Regression | AQI prediction | RMSE: 1.219, R²: >0.96 [38] | Probabilistic outputs, robustness to noise |

| GAPSO-WQI | Pollution source attribution | WQI range: 15-256 [37] | Global and local search optimization |

| Random Forest | Feature importance evaluation | Identified PM2.5, PM10, CO as critical [38] | Captures nonlinear relationships |

Comparative Analysis of Index Performance

Case Study: Upper Citarum River Assessment: A comprehensive comparison of OIP, Said-WQI, and PI methods in Indonesia's Upper Citarum River revealed significant methodological differences in pollution classification. The OIP and Said-WQI methods categorized the river's status as ranging from 'good' to 'poor', while the PI method classified it from 'mildly polluted' to 'severely polluted' [36]. Seasonal analysis showed OIP values from 3.71 to 11.20 ("poor" to "moderate"), Said-WQI between 0.67 and 2.34 ("poor" to "good"), and PI values from 4.15 to 8.13 ("moderately polluted" to "heavily polluted") [36].

Urban Landfill Impact Assessment: Research around an urban landfill in Dhaka, Bangladesh, employing 19 physicochemical parameters demonstrated WQI's effectiveness in identifying pollution gradients. The study classified three samples as "very bad" (WQI < 31) and seven as "bad" (WQI between 31 and 51.9), with the lowest value of 1.85 recorded from a sewer [39]. Principal Component Analysis identified five principal components accounting for 92.16% of WQI variation, with PC1, PC2, and PC3 explaining 38.5%, 21.38%, and 16.35% of total variance respectively [39].

Natural Versus Anthropogenic Influence Discrimination

Analytical Framework for Source Attribution

Distinguishing between natural and anthropogenic influences represents a critical research frontier in water quality assessment. A novel trend-based metric, the T-NM index, has been developed to isolate asymmetric human amplification and suppression effects across watershed systems [4]. This approach analyzed 195 natural and 1540 managed watersheds in China (2006-2020), revealing that consistent trends in 52-89% of watersheds suggest climatic dominance, while anthropogenic drivers intensified or attenuated trends by 22-158% and 14-56% respectively, with particularly pronounced effects during summer months [4].

Attribution Analysis Findings: Multivariable modeling demonstrated that seasonal factors explained 47.08% of water quality variation, with rainfall (25.37%) and slope (17.40%) accounting for COD and DO changes in natural watersheds. Conversely, anthropogenic landscape metrics including Shannon Diversity Index (11.58%) and Largest Patch Index (10.66%) dominated in managed watersheds [4]. This establishes a generalizable framework for distinguishing natural and anthropogenic influences, offering key insights for adaptive water quality management under climatic and socio-economic transitions.

Watershed Trajectory Classification

Research classifying combined COD and DO concentration trajectories identified four distinct categories of watershed behavior:

- Q1: Synchronous increases in both COD and DO (288 watersheds, 62 significant)

- Q2: COD reduction coupled with DO increase (687 watersheds, 202 significant) - Dominant pattern

- Q3: Synchronous decreases in both COD and DO (319 watersheds, 26 significant)

- Q4: COD increase accompanied by DO decrease (167 watersheds, 10 significant) [4]

Spatial analysis revealed that quadrant Q2, characterized by improving water quality (COD reduction with DO increase), dominated all trajectories (69.1% ± 8.8%), peaking at 87.5% in the Yellow River Basin, indicating successful pollution control interventions [4].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Essential Analytical Framework Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Water Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|