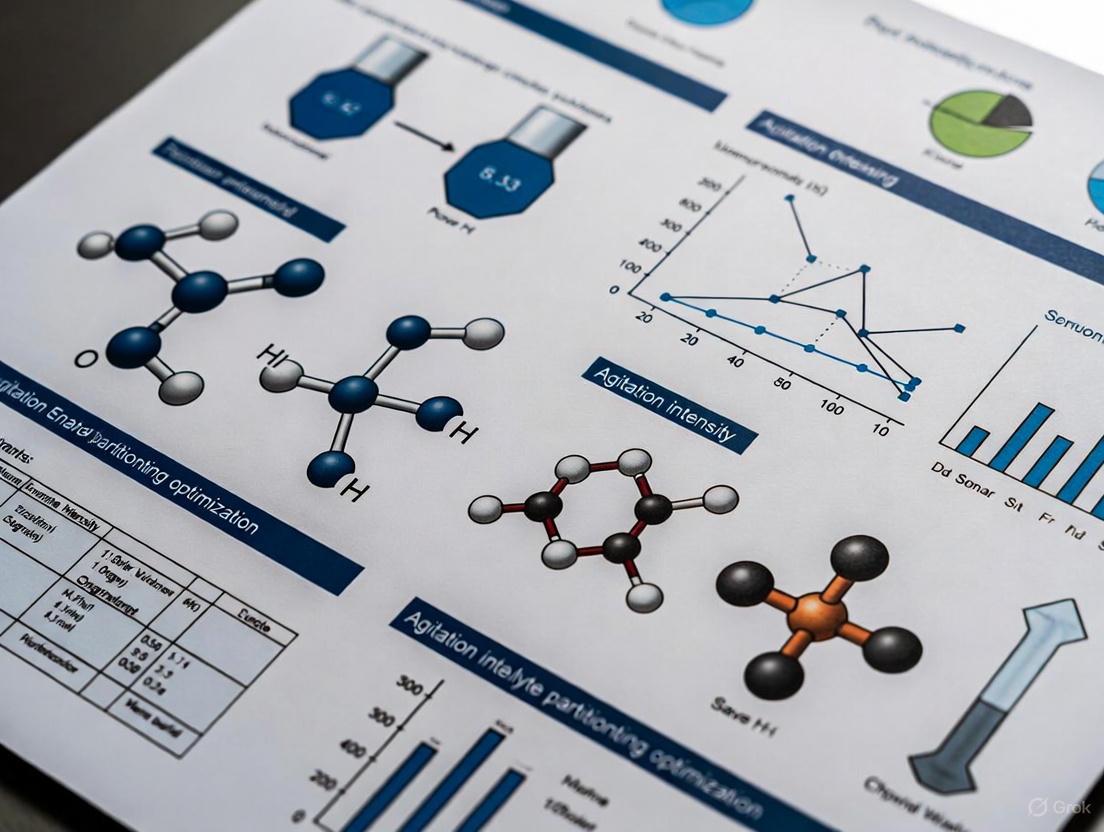

Optimizing Agitation Intensity for Enhanced Analyte Partitioning in Biomedical Separations and Bioanalysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical relationship between agitation intensity and analyte partitioning efficiency.

Optimizing Agitation Intensity for Enhanced Analyte Partitioning in Biomedical Separations and Bioanalysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical relationship between agitation intensity and analyte partitioning efficiency. It explores the foundational principles of interfacial stress and its impact on biomolecules, presents modern methodological approaches for agitation stress testing, and offers systematic troubleshooting strategies for common optimization challenges. By comparing conventional and novel validation techniques, the content delivers actionable insights for developing robust, scalable processes in pharmaceutical development and bioanalytical workflows, ultimately aiming to improve product stability, analytical sensitivity, and process predictability.

Fundamental Principles: How Agitation and Interfacial Stress Govern Analyte Partitioning

Troubleshooting Guides

Vapor-Liquid Interface Stress

Problem: Unexpected protein aggregation during transport or agitation of drug product vials.

- Potential Cause: Agitation creates a large, dynamic air-liquid interface. Proteins adsorb to this interface, unfold due to the imbalance of cohesive forces, and form aggregates when the interface is mechanically disturbed [1].

- Solution:

- Minimize Headspace: Reduce the air headspace in the vial to eliminate the air-liquid interface. Studies show that shaking vials without an air headspace substantially limits aggregation [1].

- Formulate with Surfactants: Add surfactants (e.g., polysorbates) to the formulation. They competitively adsorb at the air-liquid interface, preventing the therapeutic protein from doing so and thereby stabilizing it against interfacial stress [1] [2].

- Control Agitation Parameters: Avoid agitation that exceeds a critical threshold of acceleration and frequency, which can exacerbate interface-mediated aggregation [2].

Problem: Formation of droplets or rivulets on the inner surface of a glass container holding a solution (e.g., "tears of wine" effect).

- Potential Cause: This is a classic example of the Marangoni effect, driven by surface tension gradients caused by the differential evaporation of components (like water and ethanol) at the liquid-air interface [3].

- Solution: This is often a physical phenomenon rather than a product-stability issue. However, if it indicates undesirable composition changes, ensure container closure integrity and consider formulation modifications to minimize the surface tension gradient.

Solid-Liquid Interface Stress

Problem: Loss of protein concentration or increased sub-visible particles after a filtration step in drug substance manufacturing.

- Potential Cause: Protein adsorption to the solid filter membrane material, followed by potential conformational changes and aggregation [1]. This is prevalent in both normal flow and tangential flow filtration (TFF/UF-DF) operations.

- Solution:

- Membrane Screening: Pre-test different filter membrane materials (e.g., PVDF, PES, cellulose-based) for low protein binding with your specific molecule.

- Excipient Addition: Include excipients in the formulation that act as stabilizers or competitively adsorb to the solid surface.

- Process Optimization: For TFF processes, minimize the number of pump passes and recirculation time to reduce total exposure to shear and the membrane surface [1].

Problem: Poor wettability of a solid pharmaceutical powder, leading to handling and processing difficulties.

- Potential Cause: High solid-vapor interfacial free energy (surface energy) relative to the solid-liquid interfacial energy, resulting in a high contact angle and low spreading [4] [5].

- Solution: The solid/liquid interfacial energy (( \gamma_{sl} )) is key. It can be modified by:

- Surface Modification: Use surfactants or processing aids that adsorb onto the solid surface, lowering its surface energy and improving wettability [5].

- Particle Engineering: Alter particle morphology and roughness through different crystallization or milling processes, as roughness amplifies the intrinsic wettability of a surface [5].

Liquid-Liquid Interface Stress

Problem: Phase separation or instability in an emulsion-based drug product.

- Potential Cause: High interfacial tension between the two immiscible liquid phases, which the system seeks to minimize by reducing the interfacial area, leading to coalescence [6] [7].

- Solution:

- Emulsifiers: Incorporate effective emulsifiers that adsorb at the liquid-liquid interface, significantly reducing the interfacial tension and forming a stable barrier that prevents droplet coalescence [3].

- Homogenization: Use high-shear mixing or homogenization to create smaller droplets, but note that this increases the total interfacial area and the stress on the system, making the use of emulsifiers even more critical.

Problem: Aggregation of a biologic drug upon administration from a prefilled syringe or in an IV bag.

- Potential Cause: Exposure to silicone oil (a liquid-liquid interface) in prefilled syringes, or to the air-liquid interface in IV bags, especially when combined with agitation during administration [1].

- Solution:

- For Prefilled Syringes: The presence of silicone oil can exacerbate agitation-induced aggregation [1]. Formulation with surfactants is critical to mitigate this.

- For IV Bags: Follow the example of products like LUMIZYME, which explicitly instructs to remove the air from the IV bag "to minimize particle formation because of the sensitivity to air-liquid interfaces" [1]. Eliminating the interface is more effective than trying to stabilize the protein against it in this scenario.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between surface tension and interfacial tension?

- Answer: Surface tension is a specific term for the tension at the interface between a liquid and a gas (e.g., water and air). Interfacial tension is the broader term for the tension at the interface between any two immiscible or dissimilar phases, such as two liquids (e.g., oil and water) or a liquid and a solid [6] [7]. Both can be interpreted as a force per unit length (mN/m) or energy per unit area (mJ/m²) [7] [3].

FAQ 2: Why is transient exposure to interfaces often more damaging than static exposure?

- Answer: While proteins can adsorb to static interfaces, the aggregation is often minimal. Transient exposure, especially when combined with mechanical agitation, pumping, or compression, actively disturbs, deforms, and disrupts the protein layer adsorbed at the interface. This mechanical perturbation can cause the denatured proteins to be shed into the bulk solution as aggregates [1]. For example, static storage of a protein in an IV bag with an air headspace may not cause aggregation, but agitating the same bag will [1].

FAQ 3: Is it the interfacial stress or the shear stress during agitation that causes aggregation?

- Answer: Evidence strongly suggests that the interfacial stress is the primary driver, not the shear stress alone. Experiments have shown that applying shear stress in the absence of an interface causes little to no aggregation. However, when an interface is present, the combination of interfacial adsorption and mechanical perturbation (like shear) leads to significant aggregation [1].

FAQ 4: How do I measure the interfacial tension in my liquid-liquid system?

- Answer: Several established methods exist, broadly categorized into force tensiometry and optical tensiometry. The table below summarizes the key techniques.

Table 1: Common Methods for Measuring Interfacial Tension

| Method | Principle | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Du Noüy Ring [8] [7] | Measures the maximum force required to pull a platinum ring through an interface. | General liquid-air and liquid-liquid tension. | Requires accurate liquid density for correction factors. |

| Wilhelmy Plate [8] [7] | Measures the force on a thin platinum plate positioned at the interface. | Highly accurate surface tension measurements. | Assumes zero contact angle; does not require liquid density. |

| Pendant Drop [8] [7] | Analyzes the shape of a droplet suspended from a needle in another bulk phase. | Small sample volumes, low interfacial tensions. | Accuracy depends on drop shape; less accurate for very spherical drops. |

FAQ 5: What is the relationship between agitation parameters (frequency, acceleration) and aggregation?

- Answer: Research indicates a threshold effect. Aggregate formation increases markedly when agitation acceleration and frequency exceed a specific, critical range. This threshold appears to be common across different protein solutions. Agitation above this threshold primarily generates micron-sized aggregates via interface-mediated routes, which can be suppressed by surfactants. Notably, even agitation below this threshold can still accelerate spontaneous nano-aggregation in the bulk solution, a process not always prevented by surfactants [2].

Table 2: Key Agitation Parameters and Their Impact on Aggregation

| Parameter | Impact on Aggregation | Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Acceleration | Acts as a stress threshold. | Aggregation increases markedly above a critical acceleration value [2]. |

| Frequency | Influences the rate of interface renewal. | Higher frequencies above a threshold can exacerbate aggregation [2]. |

| Interface Presence | Primary site for aggregation initiation. | Removal of the air-liquid interface (e.g., in IV bags) prevents agitation-induced aggregation [1]. |

| Surfactant Presence | Mitigates interface-mediated aggregation. | Suppresses micron aggregate formation but may not prevent surfactant-independent nano-aggregation in the bulk [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Quantifying Agitation-Induced Aggregation

Objective: To simulate shipping stresses and determine the critical acceleration/frequency threshold for aggregate formation in a protein formulation [2].

- Sample Preparation: Fill protein solution into standard vials, ensuring consistent headspace. Include a set with and without a surfactant (e.g., 0.01% polysorbate 80).

- Agitation Stress: Use a transportation test system capable of applying tri-axial vibration. Subject samples to a matrix of various frequencies (e.g., 10-100 Hz) and accelerations (e.g., 0.1 - 2.0 g).

- Analysis:

- Micron Aggregates: Use flow imaging microscopy to count and characterize subvisible particles (2-100 µm).

- Soluble Oligomers: Use size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to quantify soluble high molecular weight species.

- Data Interpretation: Identify the combination of acceleration and frequency where a marked increase in micron aggregates occurs. This defines the process threshold. Note the change in nano-aggregates separately.

Protocol: Measuring Air-Liquid Surface Tension via the Pendant Drop Method

Objective: To determine the surface tension of a protein solution, indicating its propensity for interfacial adsorption [8] [7].

- Setup: Use an optical tensiometer equipped with a camera, a light source, and a dosing system with a needle (e.g., J-shaped needle).

- Calibration: Calibrate the instrument using a liquid of known density and surface tension (e.g., pure water) at the experimental temperature.

- Dispense Drop: Dispense a drop of the protein solution from the needle into the air (or another bulk phase for interfacial tension). The drop should be pendant (tear-shaped).

- Image Capture: Capture a high-contrast image of the static drop.

- Analysis: Software (using Axisymmetric Drop Shape Analysis, ADSA) fits the drop's shape to the Young-Laplace equation. The surface tension (( \gamma )) is calculated from the best-fit parameters, which balance gravitational force pulling the drop down and surface tension holding it up.

Diagram: Pendant Drop Measurement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Interfacial Stress Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Surfactants (Polysorbates, Pluronics) | Competitively adsorb to interfaces, protecting therapeutic proteins from unfolding and aggregation at vapor-liquid and solid-liquid interfaces [1]. |

| Force Tensiometer | Instrument used with Du Noüy ring or Wilhelmy plate probes to directly measure the force exerted by a liquid interface, providing surface/interfacial tension values [8] [7]. |

| Optical Tensiometer | Instrument that uses cameras and software for drop shape analysis (e.g., pendant drop) to indirectly determine surface/interfacial tension, ideal for small sample volumes [7]. |

| Platinum Probes (Ring, Plate) | High-energy, highly wettable probes that ensure a contact angle of ~0°, which is critical for obtaining accurate measurements with force tensiometry methods [8] [7]. |

| Flow Imaging Microscope | Characterizes and counts subvisible particles (2-100 µm) in a solution, crucial for quantifying agitation-induced micron aggregate formation [2]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Analytical technique to separate and quantify soluble protein aggregates (nanometer-sized oligomers) from monomers in a formulated solution [2]. |

Mechanisms of Agitation-Induced Protein Aggregation and Denaturation

Core Mechanisms Explained

What are the primary mechanisms behind agitation-induced protein aggregation?

Agitation-induced protein aggregation occurs through a complex interplay of interfacial adsorption and mechanical shear. The primary mechanism involves protein unfolding at air-liquid and solid-liquid interfaces, followed by aggregation of these denatured species.

When a protein solution is agitated, two key processes happen simultaneously. First, proteins adsorb to the air-liquid interface created by bubbling or foaming. At this interface, proteins undergo structural rearrangement and partial unfolding as they attempt to minimize their energy state. Second, the shear forces generated by agitation can directly perturb protein structure, though this effect is generally secondary to interfacial effects. Once unfolded, proteins expose hydrophobic regions normally buried in their native state, leading to irreversible aggregation through both non-covalent interactions and, in some cases, disulphide-mediated covalent bonds [9] [10].

The aggregation process often follows distinct kinetic phases: an initial "lag phase" where minimal aggregation occurs, followed by exponential growth as aggregates nucleate and grow, finally reaching a plateau phase where free monomers are depleted [11]. This mechanism is particularly problematic for therapeutic proteins during shipping, handling, and administration.

How do material surfaces contribute to protein aggregation?

Material surfaces play a crucial role in protein destabilization through synergistic effects with agitation. Recent proteome-scale studies demonstrate that plastic surfaces (including polypropylene), TEFLON, and even glass promote protein loss and aggregation when combined with agitation [12].

The process begins with weak interactions between proteins and container surfaces. Even when proteins briefly contact these surfaces, they can undergo partial destabilization. When released back into solution, these structurally compromised proteins have increased aggregation propensity. The material's surface properties—including hydrophobicity, charge, and chemical composition—determine the extent of protein destabilization [12].

Notably, protein loss continues even with surfaces specifically designed to minimize protein binding (such as LOBIND tubes), indicating the process involves more than simple adsorption. The combined stress of material contact and agitation creates a cycle of continuous protein destabilization that ultimately leads to significant aggregation, sometimes reaching protein losses of 45% under vigorous agitation conditions [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

How can I prevent agitation-induced aggregation in my protein formulations?

Multiple strategies can mitigate agitation-induced aggregation:

- Add non-ionic surfactants like polysorbates to compete with proteins at air-liquid interfaces [13] [10]

- Minimize air-liquid interface by using filled containers or specialized devices like the I2F that mechanically eliminate bubbles [14]

- Optimize formulation conditions including pH and ionic strength to enhance conformational stability [15] [16]

- Select appropriate container materials based on compatibility testing with your specific protein [12]

- Control temperature during handling and shipping, as aggregation propensity is temperature-dependent [13]

Why does my protein aggregate even when using low-binding tubes?

"Low-binding" tubes only reduce protein adsorption, not the fundamental destabilization mechanism. Proteins can still undergo conformational changes upon brief contact with surfaces, and agitation accelerates this process. Complete prevention requires removing all air from the system or adding stabilizing excipients, as material surface effects persist even with specialized tubes when agitation is present [12].

How does temperature affect agitation-induced aggregation?

Temperature significantly impacts both the rate and extent of agitation-induced aggregation. Research on Fc-fusion proteins demonstrates that aggregation levels and aggregate cluster sizes are temperature-dependent, though the threshold agitation speed required to initiate aggregation remains temperature-independent. Higher temperatures accelerate protein unfolding at interfaces, leading to more rapid aggregation. Interestingly, thermal stress that generates small oligomers doesn't necessarily increase subsequent agitation-induced monomer loss, indicating complex interactions between these stressors [13].

Can I use agitation testing to predict long-term storage stability?

For many antibodies, strong correlations exist between monomer recovery after agitation stress and monomer recovery after one month of quiescent storage at 40°C. This suggests agitation testing can effectively screen formulations without waiting for long-term stability data, significantly accelerating development timelines [15] [16].

Table 1: Protein Loss Across Different Material Surfaces Under Agitation

| Protein Type | Polypropylene | Glass | TEFLON | LOBIND |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | 3% | 17% | <1% | 1-2% |

| Hemoglobin | 7% | - | - | 0% |

| α-Synuclein | 9% | 16% | 9% | 9% |

| Yeast Extract | Up to 45% | High | 5% | 7% |

Table 2: Agregation Propensity Classification Based on Formulation Sensitivity

| Parameter | Group A (Insensitive) | Group B (Sensitive) |

|---|---|---|

| Response to formulation changes | Minimal impact on aggregation | Significant impact on aggregation |

| Formulation freedom | High degree of freedom | Limited formulation options |

| Primary stability factor | Conformational stability (Tm) | Compensation between conformational and colloidal stability |

| Development approach | Standard formulation screening | Requires extensive optimization |

Experimental Protocols

Standardized Agitation Stress Test

Purpose: To evaluate protein aggregation propensity under controlled agitation conditions.

Materials:

- Protein solution (1 mg/mL in appropriate buffer)

- 10 mL glass vials (Type I, USP)

- Orbital shaker or rotating wheel

- Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) system

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument

Methodology:

- Prepare protein samples at 1 mg/mL concentration in 20 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 [10]

- Fill 6 mL of sample into 10 mL glass vials

- Sparge vials with nitrogen to remove oxygen (optional)

- Agitate samples using orbital shaking at controlled speeds (e.g., 100-300 rpm)

- Maintain temperature control throughout experiment (5°C, 25°C, or 40°C) [13]

- At predetermined timepoints, analyze samples for:

- Compare results to non-agitated controls stored under identical temperature conditions

Material Compatibility Testing

Purpose: To assess the impact of different container materials on protein stability.

Materials:

- Protein solution (purified protein or cell extract)

- Containers of different materials (polypropylene, glass, TEFLON, LOBIND)

- Rotating wheel apparatus

- UV spectroscopy for concentration measurement

Methodology:

- Prepare identical protein solutions across material types

- Subject samples to rotation at 3-30 rpm for 24 hours at 6°C [12]

- Include non-agitated controls for each material

- Measure protein concentration pre- and post-agitation via UV spectroscopy

- Calculate percentage protein loss for each condition

- Analyze aggregates via Raman microscopy or SEC if significant losses detected

Mechanism Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Non-ionic surfactants (Polysorbates) | Competes with proteins at air-liquid interfaces [13] | Prevents surface-induced denaturation; typical use 0.01-0.1% |

| Size-exclusion chromatography | Quantifies monomer loss and soluble aggregates [15] | Primary analytical method for aggregation assessment |

| Dynamic light scattering | Detects subvisible particles and early aggregates [10] | Monitors aggregation kinetics and size distribution |

| LOBIND tubes | Reduces protein adsorption to surfaces [12] | Does not prevent interface-induced denaturation entirely |

| Flow imaging microscopy | Characterizes insoluble aggregates and particles [13] | Complementary technique to SEC for complete aggregation profile |

| Orbital shaker | Provides controlled, reproducible agitation stress | Enables standardized testing across formulations |

| Type I glass vials | Standard container for compatibility studies [10] | Reference material for comparing other surfaces |

Key Physicochemical Properties Affecting Analyte Partitioning Behavior

FAQs on Physicochemical Properties and Partitioning

FAQ 1: What is the difference between a partition coefficient (log P) and a distribution coefficient (log D)?

The partition coefficient (log P) describes the ratio of the concentrations of a solute in a mixture of two immiscible solvents at equilibrium, specifically referring to the un-ionized form of the compound. It is a constant for a given compound and solvent system. Conversely, the distribution coefficient (log D) describes the ratio of the sum of the concentrations of all forms of the compound (ionized plus un-ionized) in each of the two phases. Log D is therefore pH-dependent and provides a more accurate picture of a compound's lipophilicity at a specific physiological pH, such as 7.4, which is critical in drug discovery [17] [18].

FAQ 2: How does the octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow) inform solvent selection for liquid-liquid extraction (LLE)?

The octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow or log P) is a key measure of a compound's hydrophobicity. In LLE, you would generally prefer an extraction solvent where the solute has a log P value equal to or greater than its log Kow for the octanol-water system. A higher partition coefficient for your solvent system means a more favorable extraction, allowing for quantitative recovery with fewer extractions or less solvent volume [18]. For ionizable compounds, the pH of the aqueous phase can be adjusted to manipulate the distribution coefficient (log D) and "push" the neutral form into the organic phase for efficient extraction [18].

FAQ 3: Which physicochemical properties are most predictive for selecting an analyte's extraction solvent?

Research using artificial neural networks has identified a set of molecular descriptors that are highly correlated with finding a suitable extraction solvent. The most important descriptors are [19]:

- logP(o/w): The octanol/water partition coefficient, a direct measure of lipophilicity.

- Dipole moment: The molecular polarity, which influences interactions with solvents.

- Van der Waals volume (Vdw_vol): The spatial volume occupied by the molecule.

- Van der Waals energy (E_vdw): The energy associated with Van der Waals interactions. These descriptors can be used to predict the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSPs) of an ideal extraction solvent [19].

FAQ 4: How does agitation intensity and formulation affect the aggregation propensity of therapeutic proteins?

Agitation-induced aggregation is a critical challenge for therapeutic proteins. Hierarchical clustering studies have shown that proteins can be categorized into two groups based on their sensitivity to formulation changes under agitation [15]:

- Group A (Formulation-Insensitive): Their aggregation propensity is largely unaffected by changes in pH and salt concentration. For these proteins, conformational stability (Tm) is the main contributor to agitation-induced aggregation, allowing for a high degree of freedom in formulation selection [15].

- Group B (Formulation-Sensitive): Their aggregation propensity is highly sensitive to formulation changes. Changes in conformational stability in response to the formulation are the primary driver of aggregation behavior [15]. This finding suggests that agitation testing and clustering should be performed before long-term quiescent stability studies to accelerate development [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Poor Extraction Recovery in Liquid-Liquid Extraction

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Investigation & Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Low analyte recovery. | Incorrect solvent choice (unfavorable partition coefficient). | Investigate: Calculate the log P (or log D at relevant pH) of your analyte. Resolve: Choose an organic solvent where the analyte has a high partition coefficient. Use predictive models or databases to guide selection [19] [18]. |

| Inadequate phase contact or equilibrium time. | Investigate: Ensure the mixture is agitated for a sufficient time to reach partitioning equilibrium. Resolve: Increase agitation time or intensity. For microscale extractions like SPME, verify that extraction time exceeds the equilibrium time [18]. | |

| Low analyte recovery for ionizable compounds. | Incorrect pH of aqueous phase. | Investigate: Measure the pH of your aqueous buffer. Compare it to the pKa of your analyte. Resolve: Adjust the pH to suppress ionization. For weak acids, lower the pH; for weak bases, raise the pH to maximize the concentration of the neutral form and improve partitioning into the organic solvent [18]. |

| Inconsistent recovery between samples. | Improvised or unreproducible agitation method. | Investigate: Document the agitation method (e.g., vortex speed, shaking frequency). Resolve: Standardize the agitation intensity and duration across all samples. Within the context of agitation optimization research, this variable must be controlled to ensure consistent partitioning behavior [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Unexpected Aggregation in Protein Formulations Under Agitation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Investigation & Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Increased sub-visible particles or loss of monomer after agitation. | Protein is sensitive to interfacial stress. | Investigate: Classify your protein's aggregation propensity via hierarchical clustering based on its sensitivity to formulation changes [15]. Resolve: For formulation-sensitive proteins (Group B), optimize conformational stability by screening different pH and excipient conditions. Consider adding non-ionic surfactants to mitigate air-liquid interfacial stress [15]. |

| Aggregation occurs even in "optimized" formulations under mild agitation. | Inherent high sensitivity to mechanical stress. | Investigate: Characterize the protein's conformational, colloidal, and interfacial stabilities. Resolve: For proteins insensitive to formulation changes (Group A), focus on maximizing conformational stability (Tm) as the main lever to reduce aggregation. A positive correlation between agitation recovery and quiescent storage stability may allow you to bypass long-term quiescent testing [15]. |

| High variability in aggregation rates between identical experiments. | Uncontrolled agitation intensity. | Investigate: Calibrate and document agitation equipment (e.g., orbital shaker speed, fill volume of containers). Resolve: Standardize the agitation stress (e.g., rotation per minute, fill volume) as a critical process parameter. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) can model and define intensity thresholds to avoid excessive, damaging agitation [20]. |

Summarized Quantitative Data

| Compound | log POW | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetamide | -1.16 | 25 |

| Methanol | -0.81 | 19 |

| Formic Acid | -0.41 | 25 |

| Diethyl Ether | 0.83 | 20 |

| p-Dichlorobenzene | 3.37 | 25 |

| Hexamethylbenzene | 4.61 | 25 |

| 2,2',4,4',5-Pentachlorobiphenyl | 6.41 | Ambient |

This table shows the cumulative extraction yield (%) after multiple batch extractions under different conditions, assuming an initial aqueous volume of 100 mL.

| Partition Coefficient (K) | Organic Solvent Volume per Extraction | Number of Extractions | Cumulative % Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 100 mL | 1 | 66.7% |

| 2 | 100 mL | 2 | 88.9% |

| 2 | 100 mL | 3 | ~96.3% |

| 2 | 200 mL | 1 | 80.0% |

| 2 | 200 mL | 2 | 96.0% |

| 10 | 100 mL | 1 | ~90.9% |

| 10 | 100 mL | 2 | ~99.2% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Aggregation Propensity of Therapeutic Proteins via Agitation Stress and Hierarchical Clustering

Objective: To categorize therapeutic proteins based on their sensitivity to formulation changes under agitation stress, enabling efficient formulation development [15].

Materials:

- Therapeutic protein(s) of interest.

- Formulation buffers: Vary pH (e.g., 4 conditions) and salt concentration (e.g., 3 conditions).

- Agitation platform (e.g., orbital shaker).

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) system.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare 120 combinations of 10 therapeutic proteins and 12 different formulations (4 pH x 3 salt concentrations) [15].

- Agitation Stress: Subject each protein-formulation combination to a standardized agitation stress (e.g., defined shaking speed, duration, and fill volume).

- Analysis: After agitation, analyze each sample by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to quantify the percentage of monomer remaining (monomer recovery %).

- Data Clustering: Apply hierarchical clustering to the monomer recovery data. This analysis will sort the proteins into distinct groups (e.g., Group A: formulation-insensitive; Group B: formulation-sensitive) based on their aggregation propensity profiles across the different formulations [15].

- Regression Analysis: For proteins in the sensitive group (Group B), perform multiple regression analysis to determine which physicochemical parameters (e.g., conformational stability, colloidal stability) primarily contribute to the changes in monomer recovery [15].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Solvent Selection for Liquid-Liquid Extraction

Objective: To predict the optimal extraction solvent for an analyte from its molecular descriptors, reducing experimental time and solvent consumption [19].

Materials:

- Analytic of known structure.

- Molecular modeling software (e.g., Molecular Operating Environment - MOE).

- Machine learning platform (e.g., MATLAB, RapidMiner).

- Pre-trained Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model for Hansen Solubility Parameter (HSP) prediction.

- HPLC system for quantification.

Method:

- Descriptor Calculation: Draw the 3D structure of the analyte in MOE. After energy minimization, calculate the key molecular descriptors: logP(o/w), Dipole moment, Van der Waals volume (Vdwvol), and Van der Waals energy (Evdw) [19].

- HSP Prediction: Input these four descriptors into the pre-trained ANN model. The model will output the predicted Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSPs)—dD (dispersion forces), dP (dipolar forces), and dH (hydrogen bonding)—for the ideal extraction solvent [19].

- Solvent Identification: Compare the predicted HSPs to a database of known solvent HSPs. Select the solvent or solvent combination whose HSPs most closely match the predicted values [19].

- Experimental Validation: Perform the liquid-liquid extraction from the matrix (e.g., human plasma) using the predicted solvent. Quantify the analyte recovery using HPLC to validate the model's prediction [19].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Strategy for Partitioning and Aggregation Optimization. This workflow illustrates the systematic approach to optimizing analyte partitioning or protein stability, highlighting the key physicochemical properties and stress factors that must be characterized and controlled.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Partitioning and Aggregation Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol / Water System | The standard solvent system for experimentally determining the partition coefficient (log P), a foundational measure of a compound's lipophilicity [17] [18]. |

| Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSPs) | A set of three parameters (dD, dP, dH) that describe a molecule's solubility interactions. Used to rationally select or design optimal extraction solvents [19]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | An analytical technique used to monitor the aggregation state of proteins by separating and quantifying monomers from aggregates based on hydrodynamic size [15]. |

| Reversed-Phase SPE Cartridges | Solid-phase extraction products (e.g., C18, C8) used for the cleanup and concentration of nonpolar analytes from aqueous samples. Require conditioning with methanol and water before use [21]. |

| Phospholipid Removal SPE Cartridges | Specialized solid-phase extraction products designed to remove phospholipids from biological samples like plasma, reducing matrix effects in bioanalysis [21]. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | A machine learning algorithm used to model complex relationships, such as predicting the optimal extraction solvent based on an analyte's molecular descriptors [19]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my agitated reactor show decreased mass transfer efficiency despite high power input? This is often caused by an incorrect flow regime. If the impeller is flooded, it cannot effectively disperse the gas, leading to large, rapidly rising bubbles and poor gas-liquid contact [22]. This occurs when the gas flow rate is too high for the impeller's pumping capacity. To correct this, reduce the gas flow rate or increase the impeller speed to transition back to the proper gas recirculation regime [22].

Q2: How does agitation intensity affect the mass transfer coefficient (kLa) in my bioreactor?

Agitation intensity directly influences the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa). Increased agitation power reduces bubble size (increasing interfacial area, a) and enhances turbulence at the gas-liquid interface (increasing the liquid film mass transfer coefficient, kL) [22]. A widely used correlation for clean, coalescing systems is: kLa ∝ (Pg/V)^0.7 * (Vs)^0.3, where Pg/V is the gassed power input per unit volume and Vs is the superficial gas velocity [22].

Q3: What is the impact of system pressure on mass transfer in my agitated gas-liquid reactor? Elevated pressure significantly improves mass transfer performance. Key effects include [23]:

- Reduced initial bubble size at the sparger, creating a larger total interfacial area for transfer.

- Increased gas hold-up (εG), meaning a greater volume fraction of gas is retained in the liquid, prolonging contact time.

- The liquid-phase mass transfer coefficient (kL) remains largely unaffected by pressure.

- The gas-phase mass transfer coefficient (kG) is inversely proportional to pressure, but the overall effect of pressure often remains positive due to the large increase in interfacial area.

Q4: How can I optimize Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) through agitation and physicochemical properties? For LLE, successful partitioning depends on matching your agitation method with the physicochemical properties of your analytes [24].

- Analyte LogP(D): Use this essential parameter to guide solvent selection. Analytes with high positive LogP values will readily partition into organic solvents, while those with low or negative values require more polar solvents [24].

- pKa for Ionizable Compounds: Agitation brings phases into contact, but partitioning is maximized when the analyte is neutral. For acids, adjust the aqueous phase to pH < pKa - 2; for bases, adjust to pH > pKa + 2 [24].

- Salt Addition: Adding salts like sodium sulphate (3–5 M) to the aqueous phase can reduce analyte solubility and "salt out" hydrophilic compounds, improving their recovery into the organic phase during agitation [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Sudden Drop in Power Demand During Agitation

- Symptoms: A noticeable decrease in motor load or current draw in a gassed system.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Large Cavity Formation: The most common cause. At high gas flow numbers (

FlG), large cavities form behind impeller blades, changing the flow pattern and reducing power demand [22].- Solution: Reduce the gas flow rate or increase the impeller speed to shift back to the vortex cavity regime.

- Impeller Flooding: The impeller is overwhelmed by buoyancy forces and can no longer disperse the gas effectively [22].

- Solution: Significantly increase the agitator speed. The transition can be predicted using the correlation:

FlG < 30 * Fr * (D/T)^3.5, whereFris the Froude number andD/Tis the impeller-to-tank diameter ratio [22].

- Solution: Significantly increase the agitator speed. The transition can be predicted using the correlation:

- Large Cavity Formation: The most common cause. At high gas flow numbers (

Problem: Low Product Yield Due to Poor Mass Transfer

- Symptoms: Low reaction rates or biomass productivity, often traced to insufficient gas (e.g., O2, CO2) dissolution.

- Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

- Measure Hydrodynamic Parameters: Quantify key parameters to diagnose the issue [25].

- Bubble Diameter: Use high-speed photography. Smaller bubbles (e.g., 720 µm vs. several mm) indicate better dispersion and larger interfacial area [25].

- Gas Hold-up (εG): Measure the volume fraction of gas in the dispersion. Higher hold-up is typically better. It increases with system pressure [23].

- Superficial Gas Velocity: Calculate as volumetric gas flow rate / cross-sectional area of the tank.

- Calculate Non-Dimensional Numbers: These help characterize the flow regime [25].

- Reynolds Number (Re): Ratio of inertial to viscous forces.

- Eötvös Number (Eo): Ratio of buoyancy to surface tension forces.

- Morton Number (Mo): A property group.

- Evaluate Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa): This is the ultimate measure of performance. Use dynamic gassing-out methods or model predictions. If kLa is low, consider:

- Increasing agitator speed to break bubbles into smaller ones.

- Optimizing sparger design to produce finer bubbles initially.

- Increasing system pressure to enhance holdup and reduce bubble size [23].

- Measure Hydrodynamic Parameters: Quantify key parameters to diagnose the issue [25].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative data for system design and comparison.

Table 1: Key Hydrodynamic and Mass Transfer Parameters in an Airlift Photobioreactor [25]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bubble Velocity | 0.0064 m/s |

| Bubble Diameter | 720 μm |

| Superficial Gas Velocity | 0.0008 m/s |

| Bubble Rise Velocity | 0.117 m/s |

| Gas Holdup (εG) | 0.0072 |

| Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient for O2 (kLa O₂) | 0.114 s⁻¹ |

| Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient for CO2 (kLa CO₂) | 0.099 s⁻¹ |

Table 2: Non-Dimensional Numbers Characterizing Flow in an Airlift Photobioreactor [25]

| Non-Dimensional Number | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Reynolds Number (Re) | 4.51 | Ratio of inertial to viscous forces; indicates flow regime (laminar/turbulent). |

| Eötvös Number (Eo) | 0.0126 | Ratio of buoyancy to surface tension forces; indicates bubble shape. |

| Morton Number (Mo) | 8.87 × 10⁻¹² | A property group that is a function of the fluid properties. |

| Weber Number (We) | 6.85 × 10⁻⁵ | Ratio of inertial to surface tension forces; indicates the tendency for bubble deformation/breakup. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Volumetric Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) in a Stirred-Tank Reactor

- Objective: To experimentally determine the kLa for oxygen in a gassed, agitated vessel.

- Background: The kLa is a critical parameter for designing and scaling bioreactors and gas-liquid reactors. It can be determined by monitoring the increase in dissolved oxygen (DO) in the liquid after a step change in conditions.

- Materials:

- Agitated reactor vessel with air sparger and DO probe.

- Data acquisition system for DO and time.

- Nitrogen gas to deoxygenate the liquid.

- Methodology:

- Fill the reactor with the liquid medium of interest.

- Start agitation at a fixed speed. Sparge with N2 gas to strip oxygen from the liquid until the DO reading is zero.

- Stop the N2 flow and immediately begin sparging with air at the desired flow rate. Agitation must remain constant.

- Record the DO concentration as a function of time until it reaches a steady state.

- The data of DO vs. time is fitted to the equation:

ln(1 - (C/C*)) = -kLa * t, whereCis the DO at timet, andC*is the steady-state DO concentration. The slope of the linear plot is thekLa.

Protocol 2: Formulation and Coating of an Osmotic Pump Tablet for Controlled Release [26] [27]

- Objective: To develop a push-pull osmotic pump (PPOP) bilayer tablet for extended drug release.

- Background: Osmotic drug delivery uses osmotic pressure as a driving force to release drug in a controlled manner, largely independent of physiological factors [26]. This protocol outlines the core manufacturing steps.

- Materials:

- Drugs: e.g., Dicloxacillin sodium, Amoxicillin trihydrate, Trospium chloride [26] [27].

- Excipients: Osmotic agent (Sodium Chloride), pore former (Sodium Lauryl Sulphate), polymer (Polyethylene Oxide, Cellulose Acetate), binder (PVP K30), lubricant (Magnesium Stearate) [26] [27].

- Equipment: Rapid mixer granulator, fluidized bed dryer, tablet press, coating pan, laser drilling machine.

- Methodology:

- Preparation of Core Tablet:

- Pull Layer: Mix the drug, osmotic agent (e.g., Mannitol), and other intra-granular ingredients. Granulate using a binder solution (e.g., PVP K30 in Isopropyl Alcohol). Dry the granules and lubricate with Magnesium Stearate [27].

- Push Layer: Prepare granules with the drug and swelling polymer (e.g., Polyethylene Oxide) using a similar granulation process [27].

- Compress the two layers into a bilayer tablet using a rotary tablet press.

- Coating:

- Prepare a seal coat solution (e.g., Hydroxypropyl Cellulose, PEG 400 in Isopropyl Alcohol) and apply to the core tablets to prevent premature drug release [27].

- Prepare a semi-permeable membrane coating solution (e.g., Cellulose Acetate, PEG 3350 in Acetone/Water). Apply this functional coat to the sealed tablets in a coating pan [27].

- Laser Drilling: Use a laser drilling machine to create a delivery orifice (e.g., 0.6 mm diameter) on the pull layer side of the coated tablet [27].

- Preparation of Core Tablet:

Visualization of Agitation System Dynamics

Agitation System Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Agitation and Mass Transfer Experiments

| Category / Item | Function / Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Impeller Types | ||

| Radial Flow Turbine (e.g., Rushton) | Gas dispersion; creates high shear to break bubbles [22]. | Standard for kLa determination in gas-liquid reactors [22]. |

| Axial Flow Impeller (e.g., Pitched Blade, Hydrofoil) | Liquid pumping; provides good bulk mixing with lower shear [22]. | Suitable for liquid-liquid extraction where gentle mixing is needed to prevent emulsion stabilization [24]. |

| Excipients for Controlled Release | ||

| Osmotic Agent (e.g., Sodium Chloride, Mannitol) | Creates osmotic pressure gradient to drive drug release in osmotic pumps [26] [27]. | Core component in the pull layer of a PPOP tablet [27]. |

| Swelling Polymer (e.g., Polyethylene Oxide) | Expands when hydrated, pushing drug suspension out in a PPOP system [27]. | Core component in the push layer of a PPOP tablet [27]. |

| Semi-permeable Membrane (e.g., Cellulose Acetate) | Controls water influx into the tablet core; key to zero-order release kinetics [26] [27]. | Coating applied to the core tablet to create the osmotic device [27]. |

| Analytical & Optimization Aids | ||

| LogP & pKa Predictors (e.g., Chemspider, MarvinSketch) | Predicts hydrophobicity and ionization state of analytes to optimize solvent selection for LLE [24]. | Used in pre-experiment planning to determine optimal pH and solvent for extraction [24]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 20/80, Sodium Lauryl Sulphate) | Stabilizes interfaces; prevents protein aggregation at air-water interface; acts as a pore-former [28] [26]. | Added to protein formulations to prevent agitation-induced aggregation [28]. Used as a pore-former in osmotic tablet coatings [26]. |

Correlation Between Mechanical Stress and Product Quality Attributes

FAQs: Understanding Mechanical Stress in Bioprocessing

Q1: What is mechanical stress in the context of biopharmaceutical production, and why is it a concern? Mechanical stress refers to the physical forces a drug substance encounters during manufacturing unit operations such as stirring, pumping, filtration, and transportation [29] [30]. These forces, including shear stress, can disrupt the structure of sensitive biologics like monoclonal antibodies. Even mild forces can cause partial unfolding, exposing hydrophobic regions that lead to protein aggregation, which can impact product efficacy and safety [30].

Q2: How does agitation intensity directly affect my product's critical quality attributes (CQAs)? Agitation intensity is a key source of mechanical stress. High-speed agitation in low-viscosity fluids creates turbulent flow, which is effective for mixing. However, using this same strategy for high-viscosity solutions—which exhibit laminar flow—can be disastrous. The impeller may simply "drill a hole," creating a vortex and leaving product at the tank walls stagnant. This leads to poor homogeneity, localized overheating ("hotspots"), and potential product degradation [31]. The table below summarizes the core relationship between flow regime and agitation strategy.

| Flow Regime | Fluid Characteristic | Agitation Strategy | Key Risk to Product Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turbulent Flow | Low viscosity (e.g., water) | High-speed, axial flow impellers (e.g., pitched-blade turbines) | Inefficient mixing if strategy is misapplied; vortex formation. |

| Laminar Flow | High viscosity (e.g., resins, creams) | High-torque, low-speed impellers (e.g., anchor or helical ribbon agitators) | Poor homogeneity, stagnant zones, product burn-on, and batch failure [31]. |

Q3: My formulation is stable in static storage. Why does it show aggregation after pumping or filling? Stability under static conditions does not predict stability under dynamic mechanical stress [30]. Processes like pumping and filling expose the protein to rapid pressure changes, high shear at valve surfaces, and interaction with solid-liquid interfaces (e.g., tubing, filter membranes). These stresses can induce protein unfolding and aggregation that static storage tests never reveal. Proactive stress testing that simulates these real-world conditions is essential for robust formulation development [29] [30].

Q4: Can mechanical stress during sample preparation for analysis affect my results? Yes, significantly. Inefficient mixing during liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) can lead to poor analyte partitioning, reducing recovery and compromising data accuracy [24]. Furthermore, during solid-phase microextraction (SPME), the extraction device's geometry and coating can be saturated or overwhelmed by compounds in the sample, leading to displacement effects and non-linear calibration curves. Proper optimization of the extraction device and method is critical for reliable quantitative analysis [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Protein Aggregation During a Mixing Step

Possible Causes and Mitigation Strategies:

Incorrect Impeller Type for Viscosity

- Solution: For high-viscosity formulations, replace high-speed propellers with low-speed, high-torque agitators like anchor or helical ribbon impellers. These are designed to sweep the entire tank volume and ensure top-to-bottom turnover in laminar flow conditions [31].

Excessive Shear Forces

- Solution: Reduce the agitation speed. Implement a design of experiments (DoE) approach to identify the optimal range where mixing is sufficient but shear stress is minimized. Real-time monitoring tools, like ARGEN, can help track aggregation kinetics under different stirring stresses [30].

Interfacial Stress at the Air-Liquid Interface

- Solution: Avoid vortex formation, which can entrain air and create a large, damaging air-liquid interface. The use of baffles in the tank can prevent vortexing. In some cases, reducing the headspace in the container may also be beneficial [31].

Problem: Low or Variable Analytic Recovery in Liquid-Liquid Extraction

Possible Causes and Mitigation Strategies:

Suboptimal Solvent Selection

- Solution: Choose an extraction solvent whose polarity matches the analyte's hydrophobicity, indicated by its LogP(D) value. Use databases like Chemspider or Marvin Sketch to obtain this essential physicochemical property [24].

Incorrect pH for Ionizable Analytes

- Solution: For acidic analytes, adjust the aqueous phase to a pH at least two units below the pKa. For basic analytes, adjust the pH to at least two units above the pKa. This ensures the analyte is in its neutral form for optimal partitioning into the organic phase [24].

Inefficient Mixing and Phase Separation

- Solution: Optimize the extraction time and vigor of shaking empirically. To improve recovery of hydrophilic analytes (low LogP), "salt out" the analyte by adding a salt like sodium sulphate (3-5 M) to the aqueous phase, reducing the analyte's solubility and driving it into the organic phase [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Stirring-Induced Protein Instability

Objective: To evaluate the impact of controlled mechanical stirring stress on protein aggregation kinetics in different formulation buffers [30].

Materials:

- ARGEN system (or equivalent multi-cell stirring and monitoring platform)

- Protein drug substance

- Candidate formulation buffers (varying pH, excipients)

- HPLC vials and pipettes

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the protein drug substance in each of the candidate formulation buffers at the target concentration.

- Experimental Setup: Load each formulation into separate sample cells of the ARGEN instrument.

- Apply Stress: Program each cell to stir at a defined speed, creating a range of shear stress conditions. Include a static control.

- Real-Time Monitoring: Use integrated static light scattering (SLS) to monitor the change in molecular weight (aggregation) in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Plot aggregation kinetics for each formulation and stirring condition. Identify formulations that resist aggregation across the tested stress range.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Liquid-Liquid Extraction Using Physicochemical Properties

Objective: To systematically develop a robust LLE method for high recovery of target analytes, based on their LogP and pKa [24].

Materials:

- Aqueous sample containing analytes

- Organic extraction solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate, hexane, dichloromethane)

- pH adjustment solutions (e.g., HCl, NaOH)

- Sodium chloride (NaCl)

- Centrifuge tubes and vortex mixer

- HPLC system with appropriate detector

Methodology:

- Parameter Definition:

- Determine LogP(D) and pKa for all analytes using Chemspider or Marvin Sketch.

- Solvent Selection: Based on analyte LogP, select a solvent or solvent mixture with a matching polarity index.

- pH Strategy: For ionizable analytes, calculate the optimal pH for extraction. Adjust the sample pH accordingly.

- Extraction:

- Use a sample volume to organic solvent ratio of ~1:7.

- For hydrophilic analytes, add NaCl to the aqueous phase (e.g., 3% w/v).

- Vortex vigorously for a predetermined time (e.g., 60-120 seconds).

- Analysis:

- Centrifuge to separate phases clearly.

- Recover the organic phase and analyze via HPLC.

- Calculate recovery by comparing to a standard.

Visualized Workflows

Mechanical Stress Risk Assessment

Liquid-Liquid Extraction Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance to Research |

|---|---|

| LogP/D & pKa Databases (e.g., Chemspider, Marvin Sketch) | Essential for predicting analyte partitioning behavior and designing efficient extraction protocols; foundational for method development [24]. |

| High-Torque, Low-Speed Agitators (e.g., Anchor, Helical Ribbon) | Critical for mixing high-viscosity solutions in laminar flow regimes; prevents product degradation and ensures batch homogeneity [31]. |

| Mechanical Stress Screening Platform (e.g., ARGEN) | Enables real-time, parallelized monitoring of protein aggregation under controlled shear stress; vital for proactive formulation development [30]. |

| Salt Additives (e.g., Sodium Chloride, Sodium Sulphate) | Used in LLE to "salt out" hydrophilic analytes, reducing their aqueous solubility and improving recovery into the organic phase [24]. |

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balanced (HLB) Sorbent | Used in sequential microextraction to prevent saturation and displacement effects, enabling accurate quantification of polar compounds in complex matrices [32]. |

Practical Implementation: Agitation Techniques and Analytical Platform Integration

Scale-Down Agitation Models for Early-Stage Formulation Development

In the development of biologic drug products, particularly high-concentration formulations, understanding and mitigating the impact of agitation stress is critical. Scale-down agitation models are essential tools that simulate the mechanical stresses—such as shaking, mixing, and transportation—encountered during manufacturing, storage, and administration [33]. The primary role of these models is to provide crucial insights into how different levels of agitation impact drug product quality, enabling the development of stable formulations that maintain their effectiveness and safety [33].

Agitation induces mechanical stress on protein therapeutics, primarily leading to protein aggregation and subvisible particle formation. This occurs because constant shaking exposes hydrophobic patches on the protein, facilitating nucleation and unfolding [33]. The consequences are significant: aggregation compromises the protein's potency, while particulates increase immunogenicity risk and may violate regulatory guidelines [33]. Within the broader context of agitation intensity and analyte partitioning optimization research, controlling these interfacial stresses is fundamental to ensuring product quality.

Key Concepts and Mechanisms

Interfacial Stress and Protein Aggregation

Therapeutic proteins encounter various interfacial stresses throughout their lifecycle—during drug substance manufacture, drug product processing, and clinical administration [1]. These stresses occur at vapor-liquid, solid-liquid, and liquid-liquid interfaces [1].

- Vapor-Liquid Interfaces: When proteins are agitated in containers with air headspace (e.g., vials, IV bags), adsorption and unfolding at the air-water interface can occur. Subsequent mechanical perturbation of this interfacial protein layer leads to aggregation and particle shedding [1].

- Solid-Liquid Interfaces: Interactions with filters, chromatography columns, tubing, and container surfaces during processing can cause protein adsorption and conformational changes [1].

- Liquid-Liquid Interfaces: Exposure to interfaces such as silicone oil in prefilled syringes can similarly induce aggregation, especially when combined with agitation [1].

While shear stress alone rarely causes aggregation, its combination with interfacial exposure is particularly detrimental. The mechanical disruption of the interfacial protein film—through compression, expansion, or shedding—drives aggregate formation [1].

Analytical Methods for Assessing Impact

Demonstrating drug product quality attributes after agitation stress requires a comprehensive analytical approach. Key methods include [33]:

- Appearance and Turbidity: Visual inspection and optical density (OD) measurements.

- Subvisible Particles (SVP): Microflow imaging or light obscuration techniques.

- Protein Aggregation: Size-exclusion ultra-performance liquid chromatography (SE-UPLC) to quantify high molecular-weight species (HMWS).

- Charge Variants: Appropriate chromatographic or electrophoretic methods.

Experimental Protocols: Establishing a Scale-Down Model

Recommended Agitation Model Configuration

Based on current industry practice, an optimized, scientifically justified scale-down model for early-stage formulation development has been defined, especially valuable when material availability is limited [33].

Table 1: Standardized Scale-Down Agitation Model Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Vessel Type | 2R vial | Material constraints in early development; widely available [33] |

| Minimum Fill Volume | 1 mL | Ensures consistent and reliable stress application [33] |

| Vial Placement | Horizontal | Maximizes interfacial contact area for consistent stress [33] |

| Agitation Type | Orbital Shaker | Simulates a range of mechanical stresses encountered in processing [33] |

| Agitation Speed | 200 RPM | Provides robust stress level for discriminating formulation stability [33] |

| Agitation Duration | Up to 24 hours | Sufficient to induce measurable changes in critical quality attributes [33] |

| Temperature | Ambient | Standardized condition for stress testing [33] |

Comparative Analysis of Agitation Methods

Different agitation methods impart distinct stress profiles and can preferentially impact specific quality attributes. The table below summarizes three common physical agitation models.

Table 2: Comparison of Agitation Models for Biologic Formulations

| Agitation Model | Typical Operating Parameters | Primary Impact on Quality Attributes | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital Shaker | 200 RPM [33] | Predominantly promotes formation of High Molecular-Weight Species (HMWS) [33] | Robust model for formulation screening; simulates various transport stresses. |

| Multichannel Vortexer | 1200 RPM [33] | More likely to induce generation of Subvisible Particles (SVP) [33] | Provides high shear, useful for evaluating particle generation potential. |

| Bench-top Shipping Simulator (e.g., VR5500) | Manufacturer's settings | Generally subjects samples to less severe stress [33] | More closely mimics real-world shipping conditions. |

Diagram 1: Agitation stress testing workflow for formulation development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agitation Stress Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2R Vials | Primary container for small-volume agitation studies. | Standardized container; use 1 mL minimum fill volume in horizontal orientation [33]. |

| Size-Exclusion UPLC (SE-UPLC) | Quantifies soluble aggregates (High Molecular-Weight Species). | Critical for assessing protein aggregation post-agitation [33]. |

| Microflow Imaging (MFI) | Detects and characterizes subvisible particles. | Differentiates particle counts and morphology; vortexer stress particularly informative [33]. |

| Orbital Shaker | Applies controlled, reproducible agitation stress. | Set at 200 RPM for robust formulation screening [33]. |

| Vortexer | Applies high-shear agitation. | Set at 1200 RPM; useful for studying subvisible particle formation [33]. |

| Optical Density (OD) Measurement | Assesses turbidity and visible particle formation. | Initial, rapid assessment of physical stability [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Agitation Stress Issues

Problem 1: High Subvisible Particle (SVP) Counts After Agitation

- Potential Cause: The formulation may be susceptible to shear-induced aggregation at the air-liquid interface [1].

- Solution: Consider adding or optimizing surfactants (e.g., polysorbate 20/80) to compete with the protein for the interface. Evaluate if the vortexer model is overly harsh for early screening; the orbital shaker may be a more discriminating tool [33].

Problem 2: Significant Increase in Soluble Aggregates (HMWS)

- Potential Cause: Agitation is exposing hydrophobic patches, leading to protein-protein interactions and nucleation [33].

- Solution: Screen excipients known to stabilize the native protein conformation, such as sugars (sucrose, trehalose) or amino acids (arginine, histidine). Ensure the orbital shaker is used for primary assessment, as it specifically impacts this attribute [33].

Problem 3: Poor Reproducibility Between Agitation Studies

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent fill volumes or vial positioning during agitation.

- Solution: Strictly adhere to the standardized model: use 2R vials with a minimum of 1 mL fill volume and ensure they are secured horizontally on the orbital shaker platform [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a scale-down model necessary for early-stage development? A1: Scale-down models reliably predict product behavior under real-world stresses while using minimal quantities of often scarce and valuable early-stage drug substance. This allows for robust formulation screening and identification of stable candidates before large-scale manufacturing [33].

Q2: How do I choose between an orbital shaker and a vortexer? A2: The choice depends on your goal. The orbital shaker is a robust, all-around model that predominantly induces soluble aggregate (HMWS) formation. The vortexer, being more severe, is particularly useful for understanding a formulation's propensity to generate subvisible particles (SVP). Using both can provide a comprehensive stress profile [33].

Q3: What is the critical link between agitation intensity and analyte partitioning? A3: In the context of agitation stress, "analyte partitioning" refers to the distribution of the protein between the native state in the bulk solution and the denatured/aggregated state at interfaces. Increased agitation intensity increases the rate at which proteins partition to these interfaces (e.g., air-liquid), where they can unfold and nucleate aggregation. The goal of formulation optimization is to shift this partitioning equilibrium back towards the stable native state [1].

Q4: Our protein is adsorbing to the container walls. How can this be mitigated? A4: Adsorption to solid-liquid interfaces is a common form of stress. Strategies include:

- Using appropriate buffer systems and excipients.

- Employing surface-active agents to passivate the container surface.

- In extreme cases, considering a change in primary container material if viable [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Orbital Shaker Troubleshooting

Q: My orbital shaker is producing excessive noise and vibrations during operation. What could be the cause?

A: Unusual noises and vibrations often stem from improper loading or mechanical wear. Follow these steps to diagnose and resolve the issue [34] [35]:

- Balance the Load: Arrange flasks and vessels symmetrically on the platform. An uneven load can cause asymmetrical wear and irregular shaking [34].

- Inspect for Obstructions: Check for and remove any foreign objects or loose parts in or around the shaker mechanism. Use caution as broken glass may be present [35].

- Check Mechanical Components: Loose bolts, worn bearings, or a misaligned drive system can cause vibrations. Inspect these components and consult a service engineer if needed [35].

- Ensure Proper Support: Operate the shaker on a level, stable surface to prevent rocking and additional vibration [34].

Q: The shaker powers on but the platform does not move. What should I check?

A: If the unit has power but does not operate, potential causes include [35]:

- Drive Belt: A worn or broken drive belt is a common culprit. Inspect the belt for damage and schedule a replacement if necessary.

- Motor Issues: Listen for unusual motor noises, which may indicate a failure or obstruction. A faulty motor typically requires professional attention.

- Electrical Components: Check for blown fuses or loose electrical connections.

Q: My refrigerated incubator shaker fails to maintain the set temperature. How can I fix this?

A: Temperature control issues can arise from several factors [35]:

- Verify Settings and Stabilization: Confirm the temperature is set correctly and allow sufficient time for the unit to stabilize after a new temperature is set.

- Check Door Seal: A compromised door seal allows ambient air in, forcing the system to work harder. Limit unnecessary door openings during operation [34].

- Inspect Air Filter and Condenser: A dirty air filter or dust-covered condenser coil can insulate the condenser, reducing heat removal efficiency. Check and clean these components every few months with soap and water [34] [36].

- Calibrate Sensors: Aging or faulty temperature sensors may require professional calibration [35].

Vortex Mixer Troubleshooting

Q: The vortex mixer does not initiate mixing when a tube is pressed against the pad.

A: This is often a simple issue to resolve:

- Check Contact: Ensure the tube is making firm, direct contact with the rubber pad, positioned slightly off-center.

- Inspect for Debris: Clean the pad surface and the area around the drive shaft. Spilled liquids or solid debris can hinder movement.

- Internal Drive Mechanism: If the above steps don't work, the internal motor or drive mechanism may be faulty. Contact technical support for repair.

Q: The vibration pattern is irregular or the mixer is unusually loud.

A: This suggests a mechanical problem:

- Inspect the Pad and Coupling: The rubber pad may be worn or loose, or the coupling between the motor and the pad could be damaged.

- Motor Bearings: Worn motor bearings can cause noise and irregular operation. This requires service by a qualified technician.

Shipping Simulator Troubleshooting

Q: My shipping simulator test does not reproduce real-world damage, leading to under-testing or over-testing of packages.

A: This is often a calibration and setup issue:

- Review Test Standards: Confirm that the simulated truck/train profile (Grms level, duration, PSD curve) matches the expected actual distribution environment.

- Calibrate the System: Regularly calibrate the vibration table's sensors and actuators according to the manufacturer's schedule to ensure it delivers the specified motion.

- Verify Fixture and Sample Mounting: Ensure the test package is secured to the slip table correctly. A poorly mounted package or a fixture that is too flexible will not experience the proper vibration inputs.

Q: The vibration table is making a grinding noise or moves erratically.

A: This indicates a potential hardware failure:

- Check the Armature: The moving coil (armature) in the electromagnetic shaker may be damaged or scraping. Immediately stop the test to prevent further damage.

- Inspect Air Cooling: Many shakers require clean, pressurized air for cooling. Check that the air supply is active and free of obstructions.

- Contact Service: Internal damage to the shaker (e.g., to the flexures or field coil) requires immediate attention from a service engineer.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why is it critical to gradually increase the speed on an orbital shaker instead of starting at the final speed?

A: Building up speed slowly is crucial for both sample integrity and mechanical care. A sudden, high start speed can cause liquids to slosh violently instead of achieving the desired swirling motion, which is particularly detrimental to fragile cells (especially those without a cell wall). Gradually ramping up speed, a feature sometimes called "smooth acceleration," minimizes mechanical stress on the shaker's motor and drive system, prolonging the equipment's life [34] [36].

Q: How does agitation intensity affect the stability of therapeutic proteins?

A: Agitation induces shear and introduces air-liquid interfaces, which can cause protein aggregation. The propensity for agitation-induced aggregation is highly dependent on the protein itself and its formulation. Research shows that proteins can be categorized by their sensitivity to formulation changes (e.g., pH, salt concentration) under agitation. Some proteins ("Group A") are insensitive to these changes, allowing more formulation freedom, while others ("Group B") are highly sensitive, primarily due to changes in their conformational stability. This suggests that agitation testing and clustering can be an efficient first step in formulation development [15].

Q: What is the optimal fill volume for flasks on an orbital shaker to maximize aeration?

A: A low fill level, typically in the range of 10-25% of the flask's volume, is recommended for optimal mixing and aeration. This low volume creates a greater relative surface area between the liquid and the air, thereby maximizing oxygen transfer. Furthermore, it significantly reduces the risk of spillage, which can damage the shaker and contaminate the chamber [34].

Q: How can I prevent contamination in my incubator shaker?

A: Maintaining a sterile environment requires proactive cleaning [35] [36]:

- Immediate Cleanup: Clean up all spills promptly using a neutral detergent or 70% ethanol.

- Regular Decontamination: Schedule regular disinfection of the chamber using appropriate decontamination agents. Work with a qualified provider if necessary.

- Preventive Schedule: Implement a routine preventive cleaning schedule, even in the absence of visible spills, to limit microbial growth.

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Operational Characteristics of Agitation Methods

| Parameter | Orbital Shaker | Vortex Mixer | Shipping Simulator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agitation Mechanism | Orbital rotation of platform | High-frequency circular vibration | Programmable vertical/linear vibration |

| Typical Applications | Cell culture, dissolving, mixing | Rapid resuspension of pellets, small-scale mixing | Package integrity testing, product durability validation |

| Key Control Parameters | Speed (RPM), temperature, orbit diameter, runtime | Speed (RPM) | Frequency (Hz), amplitude (G), Power Spectral Density (PSD), duration |

| Optimal Fill Volume | 10-25% of flask volume [34] | 50-75% of tube volume (to prevent leakage) | N/A (Driven by package size and test standard) |

| Impact on Samples | Low-shear, promotes aeration; can cause aggregation in sensitive proteins [15] | High-shear, can damage delicate cells | Physical stress, potential for abrasion and impact |

Table 2: Common Issues and Resolutions Across Agitation Platforms

| Issue | Orbital Shaker | Vortex Mixer | Shipping Simulator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive Vibration/Noise | Unbalanced load, loose components, worn bearings [34] [35] | Worn or loose rubber pad, motor bearing failure | Loose armature, faulty amplifier, poor fixture mounting |

| Failure to Start/Operate | Broken drive belt, motor failure, electrical fault [35] | Failed motor, internal wiring disconnect | Power supply failure, amplifier fault, safety interlock triggered |

| Inconsistent Performance | Uncalibrated speed, uneven surface, overloaded platform [34] | Worn motor brushes, speed potentiometer failure | Sensor calibration drift, incorrect profile programming |

| Recommended Maintenance | Weekly cleaning, belt inspection, speed calibration, condenser coil cleaning (refrigerated) [34] [36] | Periodic pad replacement, cleaning | Regular calibration, armature inspection, air filter check |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Agitation-Induced Protein Aggregation

Objective: To determine the aggregation propensity of a therapeutic protein under orbital shaking stress across different formulation conditions [15].

Materials:

- Orbital shaker with temperature control

- Therapeutic protein solution

- Different formulation buffers (varying pH and salt concentrations)

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) system

- HPLC vials

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the protein solution in 12 different formulation conditions (e.g., 4 pH conditions x 3 salt concentrations).

- Agitation Stress: Aliquot the protein solutions into suitable containers (e.g., glass vials). Place them on the orbital shaker.

- Agitation Conditions: Agitate samples at a controlled speed (e.g., 200 RPM) and temperature (e.g., 25°C) for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours). Include stationary controls.

- Analysis: Post-agitation, analyze the samples using SEC to quantify the percentage of monomeric protein remaining versus aggregated forms.

- Data Analysis: Apply hierarchical clustering to categorize proteins based on their sensitivity to formulation changes under agitation stress.

Protocol: Optimizing Headspace Extraction Using an Orbital Shaker Incubator

Objective: To optimize headspace extraction parameters for volatile hydrocarbons using an orbital shaker incubator and a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach [37].

Materials:

- Refrigerated orbital shaker with precise temperature control

- Headspace vials and seals

- Aqueous samples spiked with volatile hydrocarbons (C5-C10)

- Gas Chromatograph with Flame Ionization Detection (GC-FID)

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Employ a Central Composite Face-centered (CCF) design to simultaneously evaluate sample volume, incubation temperature, and equilibration time.

- Sample Preparation: Transfer defined volumes of spiked water samples into headspace vials, adding salt (e.g., NaCl) to improve partitioning.

- Agitation/Incubation: Place vials in the orbital shaker incubator. Run experiments according to the DoE matrix, varying temperature, agitation speed, and time.

- Analysis: After equilibration, extract vapor from the headspace and inject into the GC-FID for analysis.

- Optimization: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to model the interaction of factors and identify optimal extraction conditions that maximize chromatographic peak area.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating protein aggregation under agitation stress.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Agitation and Partitioning Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | Swellable polymer; acts as an osmotic agent and pushing component in bilayer tablets [27]. | Formulating the push layer of a Push-Pull Osmotic Pump (PPOP) drug delivery system. |

| Cellulose Acetate | Semi-permeable membrane polymer; controls water ingress in osmotic systems [26] [27]. | Coating osmotic drug delivery tablets to achieve zero-order release kinetics. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Osmotic agent; generates osmotic pressure gradient. Also used to modify ionic strength in solutions. | Core component in osmotic tablets [26]. Salting-out agent in headspace extraction [37]. |

| Volatile Petroleum Hydrocarbons (C5-C10) | Model analytes for partitioning studies. | Studying the optimization of headspace extraction parameters (e.g., temperature, time) [37]. |

| Ethoxyquin (EQ) | A strongly non-polar model analyte for studying matrix interference and partitioning [38]. | Developing pH-dependent extraction strategies based on LogD adjustment. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)