Optimizing Nanomaterial Adsorption for Efficient Cadmium and Lead Ion Removal: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the optimization of nanomaterial adsorption for the removal of toxic cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) ions, a critical challenge in environmental remediation and...

Optimizing Nanomaterial Adsorption for Efficient Cadmium and Lead Ion Removal: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the optimization of nanomaterial adsorption for the removal of toxic cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) ions, a critical challenge in environmental remediation and biomedical safety. It explores the foundational principles of nanomaterial-heavy metal interactions, synthesizes the latest methodologies for nanomaterial fabrication and application, details systematic approaches for troubleshooting and optimizing adsorption performance, and establishes rigorous protocols for validation and comparative analysis. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review integrates cutting-edge research—from amine-functionalized cellulose to green-synthesized metal oxides—to serve as a strategic guide for developing high-performance, sustainable nanomaterial-based solutions for decontaminating water systems and ensuring the safety of biomedical products.

Understanding the Urgency and Mechanism: Cadmium, Lead Toxicity and Nanomaterial Adsorption Fundamentals

The Critical Health and Environmental Burden of Cd and Pb Contamination

Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) are two non-essential, highly toxic heavy metals whose presence in the environment poses a significant and ongoing threat to ecosystem stability and human health globally. Their critical status stems from three intrinsic characteristics: high toxicity, environmental persistence, and tendency to bioaccumulate [1] [2]. Unlike organic pollutants, these metals cannot be degraded; they remain indefinitely in the environment, accumulating in soils, water bodies, and living organisms, including humans [1] [3]. The global scale of the problem is immense, with one review noting that lead exposure alone from historical and contemporary sources leads to an estimated annual global economic loss exceeding $3.4 trillion [4].

The primary sources of Cd and Pb contamination are anthropogenic, linked to industrial and technological development. Key sources include:

- Industrial Smelting and Mining: The Cu-Pb-Zn smelting process is a major source of Cd, generating significant quantities of Cd-containing dust, slag, and waste solutions [5].

- Lead-Acid Batteries: The manufacture, use, and recycling of lead-acid batteries account for approximately 85% of global lead consumption today, creating a high risk of environmental leakage, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [4].

- Legacy Pollution: Despite the global ban on leaded gasoline in 2021, an estimated nine million metric tons of lead were emitted during its use, and this legacy contamination remains a major reservoir in soils [4].

- Consumer Products and Waste: Discarded tires, electronic waste, and improperly disposed industrial products continue to leach Cd and Pb into the environment [6].

Health and Environmental Impacts: A Detailed Analysis

The mechanisms of Cd and Pb toxicity are multifaceted, impacting biological systems from the cellular to the organ level.

Mechanisms of Toxicity at the Cellular Level

Heavy metals exert toxic effects through several interconnected biochemical pathways [2]:

- Induction of Oxidative Stress: Metals like Cd and Pb can trigger the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). This overwhelms the body's antioxidant defenses, leading to oxidative damage of lipids, proteins, and DNA [2].

- Interaction with Biomacromolecules: Cd and Pb bind to functional groups in proteins and enzymes, particularly sulfhydryl groups (-SH), altering their structure and deactivating them. For example, Pb can replace zinc in the enzyme δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD), disrupting heme synthesis [2].

- Ionic Mimicry: Cd can mimic essential metal ions like calcium (Ca²⁺) and zinc (Zn²⁺), allowing it to hijack their transport pathways and disrupt critical cellular signaling and metabolic functions [2].

The diagram below illustrates the interconnected pathways of Cd and Pb toxicity leading to cellular dysfunction.

Organ-Specific and Systemic Health Effects

Sustained exposure to Cd and Pb, even at low levels, leads to severe and often irreversible health consequences.

Table 1: Health Hazards of Cadmium and Lead Exposure

| Heavy Metal | Primary Health Hazards & Target Organs | Carcinogenicity |

|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | Kidney damage (renal dysfunction), osteoporosis, severe gastrointestinal effects, lung cancer [1] [3] [2]. | Classified as a human carcinogen (Group 1), linked to lung, prostate, and kidney cancers [1] [5]. |

| Lead (Pb) | Neurodevelopmental effects (cognitive impairment in children), kidney damage, hypertension and cardiovascular issues, reproductive abnormalities, anemia [1] [3] [4]. | Classified as a probable human carcinogen. Its toxicity also stems from a very long biological half-life [1] [2]. |

The persistence of these metals in the human body is a major concern; cadmium, for instance, can persist for decades, leading to bioaccumulation and increased toxicity with chronic exposure [1].

Regulatory Limits and Environmental Persistence

Recognizing the severe toxicity of these metals, international bodies have established stringent regulatory limits for their concentration in drinking water, often in the parts-per-billion (ppb) range.

Table 2: Regulatory Limits for Cd and Pb in Drinking Water

| Regulatory Body | Cadmium (Cd) Limit | Lead (Pb) Limit | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| World Health Organization (WHO) | 3 μg L⁻¹ [1] | 10 μg L⁻¹ [1] | Preliminary guideline values; no level is deemed completely safe. |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | 5 μg L⁻¹ [1] [3] | Action level of 15 μg L⁻¹ [1] | The Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG) for lead is zero [1]. |

| European Union (EU) | 5 μg L⁻¹ [1] | 5 μg L⁻¹ [1] | Recently reduced from 10 μg L⁻¹ to 5 μg L⁻¹. |

The "zero" MCLG for lead and the low thresholds for both metals underscore the consensus that no level of exposure is risk-free [1]. Environmental persistence is a key challenge; lead from past gasoline use remains enriched in surface soils worldwide, acting as a long-term reservoir for re-release and exposure [4].

Nanomaterial-Based Remediation: A Technical Support Center

Within the context of a thesis focused on optimizing adsorption efficiency, this section provides a technical support framework for researchers developing nanomaterial solutions for Cd and Pb removal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

A wide array of natural and synthetic nanomaterials have been investigated as adsorbents. The following table details several key materials used in recent studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cd and Pb Adsorption

| Material Name | Material Type | Key Function/Mechanism in Adsorption | Reported Performance (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKUST-1/NiSe Nanocomposite [1] | Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) / Metal Selenide Composite | High surface area and porosity from MOF; additional active sites and enhanced stability from NiSe; coordination and binding at metal sites. | Used in a fixed-bed column for "zero-waste" removal; high efficiency for both Pb and Cd [1]. |

| Sugarcane Bagasse-derived Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄, ZnO, CaO, MgO) [6] | Green-synthesized Multicomponent Metal Oxides | Magnetic properties (Fe₃O₄) aid separation; mixed oxides provide diverse adsorption sites; sustainable synthesis. | ~95-99% Pb²⁺ removal in 15-30 min; ~90% Cd²⁺ removal in 10 min under optimal conditions [6]. |

| L. fermentum 6b Exopolysaccharide (EPS) [7] | Biopolymer | Surface functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl) act as binding sites for metal ions via complexation; safe (GRAS) and biodegradable. | Removal efficiencies of ~52.7% for Cd and ~46.5% for Pb under optimal pH and dose [7]. |

| Synthetic Na-X Zeolite [8] | Porous Aluminosilicate | Ion-exchange of Na⁺ for Cd²⁺/Pb²⁺; high cation exchange capacity (CEC) and tunable surface chemistry. | Maximum Cd(II) adsorption capacity of 185–268 mg/g, superior to natural clays [8]. |

| Dead Archaeal Cells (Natronolimnobius innermongolicus) [9] | Microbial Biomass (Biosorbent) | Physicochemical binding of metal ions to functional groups on the outer cell wall (surface adsorption mechanism). | Max Cd(II) uptake capacity of 128.21 mg/g; fast equilibrium (~5 min) [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol A: Standard Batch Adsorption Experiment for Isotherm and Kinetics

This is a foundational method for evaluating adsorbent efficacy and mechanism [9] [7] [8].

- Adsorbent Preparation: Prepare the nanomaterial (e.g., synthesize, dry, and sieve to specific particle size).

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare individual 1000-2000 mg L⁻¹ stock solutions of Cd(II) and Pb(II) from salts like Cd(NO₃)₂, Pb(NO₃)₂, CdCl₂, or CdSO₄ [9] [7].

- Parameter Variation: In a series of Erlenmeyer flasks, combine a fixed mass of adsorbent with a fixed volume of metal solution. Systematically vary one parameter at a time:

- pH: Adjust initial pH (e.g., 3.0-8.0) using dilute HCl/NaOH, noting its critical influence on metal speciation and adsorbent surface charge [9] [7] [8].

- Contact Time: Agitate from minutes to hours (e.g., 2.5 - 1440 min) to study kinetics [9] [8].

- Initial Concentration: Use a range (e.g., 10 - 950 mg L⁻¹) for isotherm studies [9] [8].

- Adsorbent Dose: Test different doses (e.g., 0.5 - 4 g L⁻¹) [9].

- Equilibrium and Separation: Shake the mixtures at constant temperature and speed. After the set time, centrifuge to separate the adsorbent from the solution.

- Analysis: Measure the residual metal concentration in the supernatant using Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [9] [7].

- Data Calculation: Calculate adsorption capacity (qₑ in mg/g) and removal efficiency (%) using standard formulas [9].

The workflow for a standard batch adsorption experiment is summarized below.

Protocol B: Fixed-Bed Column Adsorption for Scalability

This protocol is used to simulate larger-scale, continuous flow treatment systems [1].

- Column Preparation: Pack a glass or acrylic column with a known mass of the adsorbent (e.g., a coating of HKUST-1/NiSe on the inner wall or a packed bed of granules) [1].

- Feed Solution: Prepare a solution with a known, constant concentration of Cd(II) and/or Pb(II).

- Continuous Flow: Pump the contaminated water through the column at a controlled, constant flow rate.

- Effluent Collection: Collect the effluent at regular time intervals.

- Analysis and Breakthrough: Analyze the effluent metal concentration to determine the "breakthrough curve," which shows how the adsorption capacity changes over time until the adsorbent is exhausted [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why is the removal efficiency for my nanomaterial low, even though it has a high theoretical surface area? A: This is a common issue. Investigate the following:

- Solution pH: This is the most critical parameter. At low pH (high H⁺ concentration), protons compete heavily with metal cations for adsorption sites, drastically reducing efficiency. Efficiency typically increases as pH rises. Determine the pHₚᶻᶜ (point of zero charge) of your material; metal cation adsorption is favored at a solution pH > pHₚᶻᶜ [9] [8].

- Agglomeration: Nanoparticles can aggregate, reducing the accessible surface area. Consider using supports or functionalization to improve dispersion.

- Pore Blockage: The metal ions or other species in the solution may be too large to access the micropores of your material.

Q2: The adsorption kinetics of my material are too slow for practical application. How can I improve them? A: Slow kinetics suggest limited mass transfer or diffusion.

- Reduce Particle Size: Smaller particles have shorter intraparticle diffusion paths and higher external surface area, leading to faster uptake.

- Increase Mixing/Agitation: This enhances the diffusion of metal ions from the bulk solution to the adsorbent surface (film diffusion).

- Introduce Macro/Mesopores: Creating a hierarchical pore structure can improve the transport of ions to the internal microporous active sites. Materials like exopolysaccharides or some composites often reach equilibrium faster than purely microporous materials [9] [7].

Q3: My adsorbent works well in single-metal solutions, but performance drops significantly in a multi-metal wastewater. How can I improve selectivity? A: Real wastewaters contain multiple competing ions.

- Functionalize the Surface: Graft specific functional groups (e.g., thiols (-SH) for soft metals like Cd and Pb, amines (-NH₂)) that have a higher affinity for your target metals over interfering ions like Ca²⁺ or Mg²⁺ [3].

- Optimize pH for Selectivity: Different metals precipitate or form hydroxy complexes at different pH values. Carefully tuning the pH can favor the adsorption of one metal over another.

- Use Ion-Imprinted Materials: Synthesize polymers or composites with cavities specifically tailored to the ionic radius and coordination geometry of Pb²⁺ or Cd²⁺.

Q4: How can I model my adsorption data to understand the mechanism? A: Fit your equilibrium and kinetic data to established models.

- Isotherm Models: Use Langmuir (assumes monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface) and Freundlich (assumes multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface) models. The best fit provides insight into the adsorption nature [6] [7] [8].

- Kinetic Models: Use Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) and Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) models. The PSO model often provides the best fit for chemisorption, which is common for Cd and Pb removal [6] [7].

Q5: How do I handle and dispose of spent adsorbents to avoid secondary pollution? A: This is crucial for a "zero-waste" goal [1].

- Desorption and Regeneration: Test eluents like dilute acids (HCl, HNO₃) or EDTA to desorb the bound metals, allowing for both adsorbent regeneration and concentrated metal recovery for potential recycling [8] [5].

- Safe Disposal: If regeneration is not feasible, the spent adsorbent must be stabilized (e.g., via cementitious solidification) before being disposed of as hazardous waste in a secure landfill. For some materials, thermal treatment may be an option.

This guide provides technical support for researchers working on the removal of cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) ions using nanomaterial-based adsorbents. The content focuses on the essential adsorption mechanisms—chemisorption, electrostatic interaction, and chelation—to help you troubleshoot common experimental challenges, optimize removal efficiency, and correctly interpret your results.

Fundamental Mechanisms FAQ

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between physisorption and chemisorption?

Physisorption and chemisorption are the two primary classes of adsorption mechanisms. Their key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Characteristics of Physisorption vs. Chemisorption

| Characteristic | Physisorption | Chemisorption |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Weak forces (van der Waals, dipole-dipole) [10] | Strong, ionic or covalent bonds [11] |

| Enthalpy (ΔH) | Low (similar to liquefaction) [10] | High (comparable to heat of reaction) [10] |

| Reversibility | Fully reversible [10] | Often irreversible and selective [11] |

| Adsorption Layer | Often forms multilayers [12] | Typically monolayer adsorption [11] |

| Isotherm Model | Often fits Freundlich model [6] | Often fits Langmuir model [6] |

Q2: How does electrostatic interaction function in heavy metal adsorption?

Electrostatic interaction is a physical adsorption force where ions are attracted to a surface with an opposite charge.

- Mechanism: It is governed by the surface charge of the adsorbent and the ionic charge of the metal in solution. The surface charge is highly dependent on the solution pH relative to the adsorbent's point of zero charge (pHPZC) [11].

- When it Dominates: This mechanism is primary when the solution pH is such that the adsorbent surface is oppositely charged to the target metal ion. For example, at a pH above the pHPZC, the surface is negatively charged and favorably attracts cationic metals like Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ [11].

Q3: What defines a chelation mechanism, and how is it used in remediation?

Chelation is a specific, powerful form of chemisorption.

- Mechanism: It involves the formation of multiple coordinate covalent bonds between a single metal ion and multiple functional groups (e.g., -NH₂, -OH, -COOH) on the adsorbent, creating a stable, ring-like structure [3].

- Application: Adsorbents are often functionalized with ligands containing donor atoms (like O, N, S) to create these chelating sites. This mechanism is highly selective for specific metal ions, even in complex wastewater streams [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: How can I determine which adsorption mechanism is dominant in my experiment?

You can infer the dominant mechanism by analyzing your equilibrium and kinetic data, as well as the chemical properties of your adsorbent.

Table 2: Identifying Dominant Adsorption Mechanisms

| Experimental Observation | Interpretation & Likely Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Isotherm Data fits the Langmuir model (R² ≈ 1) [6] | Homogeneous, monolayer chemisorption is occurring. |

| Isotherm Data fits the Freundlich model (R² ≈ 1) [6] | Heterogeneous, multilayer physisorption is occurring. |

| Kinetic Data fits the Pseudo-Second-Order model (R² ≈ 1) [6] | The adsorption rate is controlled by chemisorption. |

| Kinetic Data fits the Pseudo-First-Order model (R² ≈ 1) [6] | The adsorption rate is controlled by physisorption. |

| Adsorption capacity changes significantly with solution pH | Electrostatic interaction is a key contributing mechanism [11]. |

| Adsorbent has functional groups like -NH₂, -COOH, -SH | Chelation or surface complexation is highly probable [3]. |

Q5: Why is my adsorption capacity for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ lower than expected?

Several factors can lead to suboptimal performance. Consult the following flowchart to diagnose the issue.

Q6: My adsorbent performs well in batch tests but fails in a continuous flow column. Why?

This common issue often relates to kinetics and physical properties.

- Cause 1: Slow Kinetics. In a batch system, extended contact times allow for slow chemisorption processes. In a flow column, the contact time is much shorter. If the adsorption kinetics are not fast enough, the metals will not be fully removed.

- Solution: Test your adsorbent's kinetics. If it follows a pseudo-second-order model but has a slow rate constant, it may not be suitable for rapid flow systems without modification [6].

- Cause 2: Poor Hydraulics. Fine nanomaterials can cause high pressure drops or even clog the column.

- Solution: Consider immobilizing the nanomaterial on a larger, porous support like alginate beads or larger granules to maintain hydraulic conductivity [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Differentiating Physisorption and Chemisorption via Isotherm and Kinetic Analysis

This methodology is adapted from studies on nanoparticle adsorption [6].

Objective: To determine the dominant adsorption mechanism of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ on a novel nanomaterial by fitting experimental data to isotherm and kinetic models.

Materials:

- Stock solutions: 1000 mg/L Pb(NO₃)₂ and CdCl₂ in ultrapure water.

- Synthesized nanomaterial adsorbent (e.g., Fe₃O₄–ZnO nanoparticles [6]).

- pH meter, orbital shaker, centrifuge, and Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) or ICP-MS.

Procedure:

- Batch Experiments: Prepare a series of 50 mL centrifuge tubes with fixed adsorbent dosage (e.g., 50 mg) and varying initial metal concentrations (e.g., 10–500 mg/L). Adjust pH to the optimum value (e.g., 5.0–6.0).

- Equilibrium Isotherms: Shake tubes for 24 hours (or until equilibrium) at constant temperature. Filter and analyze the supernatant for residual metal concentration.

- Adsorption Kinetics: In a separate batch with a fixed initial concentration, take 1 mL samples at different time intervals (e.g., 2, 5, 10, 30, 60, 120 min). Analyze residual metal concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Fit Isotherm Models:

- Langmuir: ( qe = (qm KL Ce) / (1 + KL Ce) ) ... suggests chemisorption.

- Freundlich: ( qe = KF C_e^{1/n} ) ... suggests physisorption.

- Fit Kinetic Models:

- Pseudo-First-Order: ( \log(qe - qt) = \log qe - (k1 / 2.303)t ) ... suggests physisorption.

- Pseudo-Second-Order: ( t / qt = 1 / (k2 qe^2) + (1 / qe) t ) ... suggests chemisorption.

Table 3: Exemplary Isotherm and Kinetic Model Parameters from Literature

| Parameter | Pb²⁺ on Fe₃O₄-ZnO Nanoparticles [6] | Cd²⁺ on Fe₃O₄-ZnO Nanoparticles [6] | Cd²⁺ on Synthetic Na-X Zeolite [8] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Fit Isotherm | Langmuir | Freundlich | Langmuir / Sips |

| Maximum Capacity | ~95-99% removal | ~60-90% removal | 185–268 mg/g |

| Best Fit Kinetic Model | Pseudo-Second-Order | Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order |

| Implied Mechanism | Monolayer Chemisorption | Heterogeneous Physisorption | Monolayer Chemisorption |

Protocol 2: Probing Chelation and Electrostatic Interactions via pH Edge Experiments

Objective: To evaluate the role of electrostatic attraction and chelation by measuring adsorption capacity across a pH range.

Materials: As in Protocol 1.

Procedure:

- Prepare a series of batch experiments with fixed adsorbent dose and metal concentration.

- Adjust the initial pH of each tube to cover a wide range (e.g., pH 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Use dilute HNO₃ or NaOH for adjustment.

- Shake until equilibrium, then measure final pH and residual metal concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Plot adsorption capacity (%) versus final pH.

- A sharp increase in adsorption as pH crosses the adsorbent's point of zero charge (pHPZC) strongly indicates electrostatic interaction as a controlling mechanism [11].

- A gradual increase in adsorption across a wide pH range, especially for adsorbents with known chelating functional groups, suggests surface complexation or chelation is significant [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Nanomaterial-Based Heavy Metal Removal Research

| Material / Reagent | Function & Rationale | Example in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane Bagasse | A renewable, silica-rich precursor for the green synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄, ZnO, MgO) [6]. | Used to synthesize multicomponent nanoparticles for Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ removal from seawater [6]. |

| Bimetallic MOFs (BMOFs) | Porous adsorbents with two metal ions offering synergistic effects, high surface area, and tunable functionality for enhanced capacity and selectivity [13]. | Emerging as high-performance adsorbents for removing Pb, Cd, Cr, and other metals from water [13]. |

| Natural Zeolites (e.g., Clinoptilolite) | Low-cost, natural aluminosilicate minerals with cation exchange capacity, suitable for initial screening and baseline studies [8]. | Used for Cd²⁺ removal; generally lower capacity than synthetic versions but cost-effective [8]. |

| Synthetic Zeolites (e.g., Na-X) | High-purity, synthetically produced zeolites with uniform pores and very high specific surface area and cation exchange capacity [8]. | Demonstrated superior Cd²⁺ adsorption capacity (268 mg/g) compared to natural clays and zeolites [8]. |

| Blackberry (Rubus glaucus) Extract | A natural stabilizing agent in green synthesis; its polyphenols can reduce metal salts and prevent nanoparticle aggregation [6]. | Used to stabilize sugarcane-bagasse-derived nanoparticles [6]. |

For researchers and scientists focused on removing toxic cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) ions from water and biological matrices, engineered nanomaterials offer a powerful solution. The efficiency of these nanosorbents is not a product of chance but is fundamentally governed by three key physicochemical properties: high specific surface area, tunable surface chemistry (functional groups), and tailored porosity [14] [3]. Optimizing these properties is crucial for enhancing adsorption capacity, selectivity, and kinetics in sample preparation and drug development workflows. This technical guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides proven protocols to maximize the performance of your nanosorbents for heavy metal remediation.

► FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my nanosorbent's adsorption capacity lower than literature values?

A low adsorption capacity often results from suboptimal interplay between the nanosorbent's physical structure and surface chemistry.

- Potential Cause #1: Inadequate specific surface area.

- Solution: Increase the surface area by optimizing synthesis parameters. For carbon-based nanomaterials, this can be achieved through chemical or physical activation methods. For instance, activated carbon prepared from avocado kernels demonstrated high removal efficiency for Cd and Pb, which is directly linked to its developed porous structure [15].

- Potential Cause #2: Lack of specific functional groups.

- Solution: Functionalize the nanosorbent surface with groups that have high affinity for your target metal ions. Lead (Pb²⁺) removal is often enhanced by N-C=O and other N-containing functional groups, while cadmium (Cd²⁺) shows strong interactions with oxygen-containing groups like carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) [16]. Grafting these groups via chemical modification, such as using chitosan and pyromellitic dianhydride on biochar, can significantly boost performance [16].

- Potential Cause #3: Pore size mismatch.

- Solution: Ensure the nanosorbent's pore size is suitable for the target ion. The pore size should be large enough to allow for easy diffusion and access to binding sites. Micropores (<2 nm) can provide high surface area but may be inaccessible for larger hydrated ions or complexes, so a hierarchy of micro-, meso-, and macropores is often ideal [14].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the selectivity of my nanosorbent for cadmium in the presence of lead, or vice versa?

Competitive adsorption is a major challenge in complex matrices. Selectivity is primarily engineered through surface functionalization.

- Strategy #1: Leverage coordination chemistry.

- Solution: Utilize functional groups with a higher affinity for one metal over another. For example, incorporating sulfur-containing groups (e.g., thiols) can enhance selectivity for Cd²⁺ or Hg²⁺ due to softer Lewis acid-base interactions.

- Strategy #2: Use ion-imprinted polymers (IIPs).

- Solution: IIPs are synthetic materials with cavities tailored to the size, coordination number, and geometry of a specific target ion (e.g., Pb²⁺ or Cd²⁺). This provides high selectivity, making them ideal for isolating specific metals from a mixture [17].

- Strategy #3: Optimize the solution pH.

- Solution: The pH affects the speciation of metal ions and the surface charge of the nanosorbent. In a mixed system, the uptake of Cd²⁺ can be increased in the presence of Pb²⁺, while the uptake of Pb²⁺ may decrease in the presence of other metals [18]. Fine-tuning the pH can help favor the adsorption of one ion over the other.

FAQ 3: My magnetic nanosorbent (e.g., Fe₃O₄) is oxidizing or aggregating. How can I improve its stability?

Stability is critical for reusability and consistent performance.

- Solution: Apply a protective coating. Core-shell structures are highly effective. Coating the magnetic core (e.g., Fe₃O₄) with an inert shell of silica, zinc oxide (ZnO), or a stable polymer can prevent oxidation and aggregation [19]. For instance, ZnO@Fe₃O4 core-shell nanoparticles combine the magnetic properties of iron oxide with the chemical stability and additional adsorption sites provided by zinc oxide [19].

► Optimizing Key Properties: Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Optimal Adsorption pH

The pH of the solution is one of the most critical parameters affecting adsorption efficiency.

Workflow:

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Create standard solutions of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ (e.g., 50 mg/L) in ultra-pure water.

- Set pH Range: Prepare a series of samples (e.g., 50 mL each) and adjust their pH to cover a range from 2 to 8 using dilute NaOH (0.01 M) or HCl (0.01 M). Use a pH meter for accuracy.

- Adsorption Experiment: Add a fixed, known amount of your nanosorbent (e.g., 0.1 g) to each sample.

- Equilibrate: Agitate the mixtures in a shaker or ultrasonic bath for a predetermined time (e.g., 60 minutes) to reach equilibrium [18].

- Separate and Analyze: Separate the nanosorbent (via filtration, centrifugation, or magnet) and measure the residual metal ion concentration in the supernatant using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) or ICP-MS.

- Calculate and Plot: Calculate the removal efficiency (%) or adsorption capacity (mg/g) for each pH value. The pH yielding the highest value is optimal. Studies often find the optimum around pH 5.5-6 for Cd and Pb [18] [19].

Protocol 2: Functionalizing Biochar with Chitosan for Enhanced Capacity

This protocol outlines a method to introduce amino and carboxyl groups onto biochar, improving its metal binding capabilities [16].

Materials:

- Biochar (e.g., derived from silkworm excrement, aspen sawdust, or avocado kernels)

- Chitosan

- Pyromellitic dianhydride (PD)

- Acetic acid (2% v/v)

- NaOH solution (1% w/v)

- Dimethylformamide (DMF)

Procedure:

- Chitosan Modification:

- Dissolve 1.0 g of chitosan in 50 mL of 2% acetic acid solution.

- Add 1.0 g of biochar to the chitosan solution.

- Stir the mixture in a water bath at 50°C for 30 minutes.

- Slowly add the mixture dropwise into 300 mL of 1% NaOH solution to precipitate the chitosan onto the biochar.

- Let it stand at room temperature for 24 hours, then filter and wash with ultrapure water until neutral pH. Dry at 60°C for 24 hours.

- Pyromellitic Dianhydride (PD) Modification:

- Dissolve 1.5 g of PD in 50 mL of DMF.

- Add 0.5 g of the chitosan-modified biochar to the PD solution.

- React the mixture in a 50°C water bath for 5 hours with stirring.

- Cool to room temperature, then rinse sequentially with DMF, ultrapure water, and 1% NaOH solution. Finally, wash with ultrapure water to neutral pH and dry at 60°C for 24 hours.

- The final product (GBC) will have enhanced amino and carboxyl functional groups for metal ion complexation [16].

Quantitative Performance of Selected Nanosorbents

The following table summarizes the adsorption performance of various advanced nanosorbents for cadmium and lead removal, demonstrating the impact of optimized properties.

Table 1: Performance Data of Nanosorbents for Cd and Pb Removal

| Nanosorbent Material | Target Metal | Optimal pH | Max Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Key Functional Groups / Properties | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO@Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Nanoparticles | Pb(II) | 6.0 | - | Metal-OH groups, magnetic separation | [19] |

| ZnO@Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Nanoparticles | Cd(II) | 6.0 | - | Metal-OH groups, magnetic separation | [19] |

| Multicomponent Nanoparticles (from sugarcane bagasse) | Pb(II) | 5.5 | 4.59 | Mixed oxides (Fe₃O₄, ZnO, CaO), green synthesis | [6] |

| Multicomponent Nanoparticles (from sugarcane bagasse) | Cd(II) | 5.5 | 4.53 | Mixed oxides (Fe₃O₄, ZnO, CaO), green synthesis | [6] |

| Chitosan-PD Modified Biochar (GBC) | Pb(II) | - | ~12% higher than unmodified | N-C=O, N-containing groups | [16] |

| Chitosan-PD Modified Biochar (GBC) | Cd(II) | - | ~12% higher than unmodified | N-containing groups, C=C | [16] |

| Activated Carbon (Avocado Kernel) | Pb(II) | 7 | 89.4% removal* | Amorphous, porous structure | [15] |

| Activated Carbon (Avocado Kernel) | Cd(II) | 7 | 99.5% removal* | Amorphous, porous structure | [15] |

Note: * indicates removal efficiency (%) under specified conditions rather than a maximum capacity (mg/g).

► Experimental Workflow Visualization

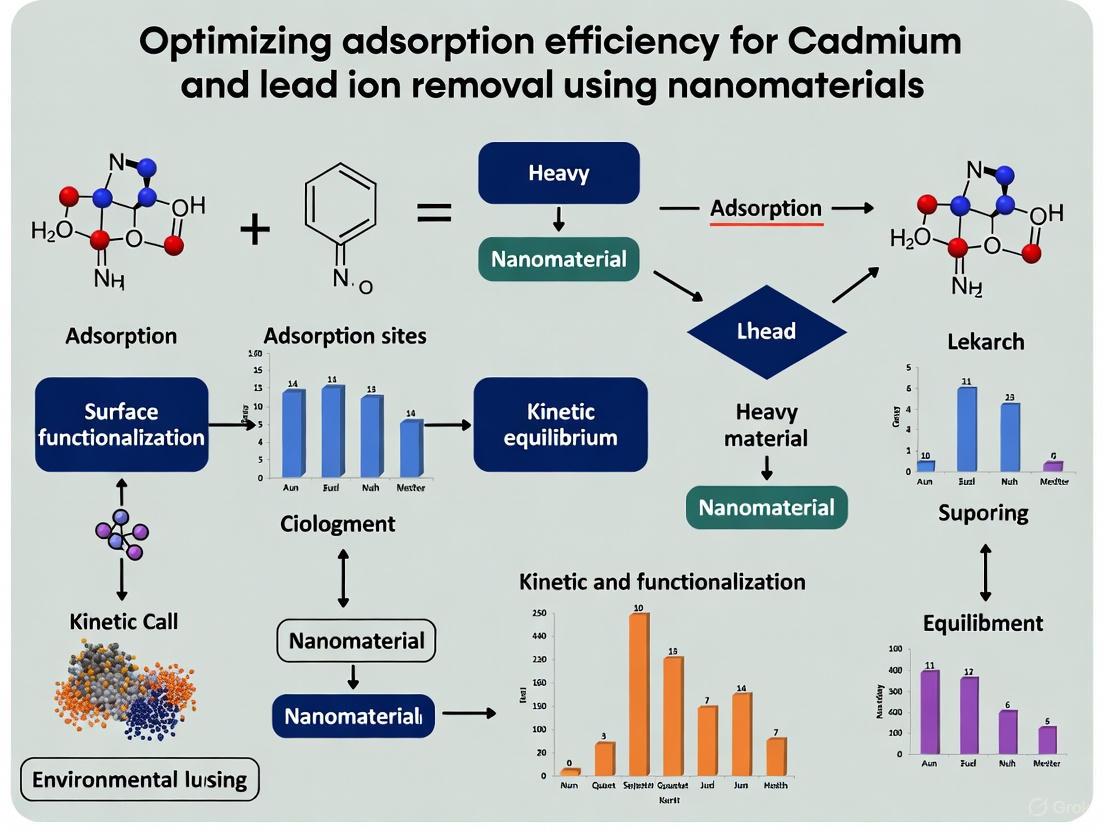

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing and applying nanosorbents for heavy metal removal, from material selection to performance evaluation.

Diagram 1: Nanosorbent development and optimization workflow.

► The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key materials and their functions for experiments involving nanosorbents for heavy metal removal.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Nanosorbent Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fe₃O₄ (Magnetite) Nanoparticles | Provide a magnetic core for easy separation in MSPE. | Core for ZnO@Fe₃O₄ composite sorbent [19]. |

| Chitosan | Natural biopolymer used to introduce amino (-NH₂) functional groups onto sorbents. | Modification of biochar to enhance metal binding [16]. |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles | Provide high thermal stability and surface -OH groups for metal coordination. | Shell material in ZnO@Fe₃O₄ composites [19]. |

| Pyromellitic Dianhydride (PD) | Cross-linking agent that introduces carboxyl (-COOH) groups. | Used with chitosan to further functionalize biochar [16]. |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | Agricultural waste used as a sustainable precursor for green nanomaterial synthesis. | Source of multicomponent metal-oxide nanoparticles [6]. |

| Silkworm Excrement / Aspen Sawdust | Low-cost biomass feedstock for the production of porous biochar. | Raw material for producing high-performance biochar [16] [20]. |

| Standard Metal Solutions (e.g., Cd(NO₃)₂, Pb(NO₃)₂) | Used to prepare synthetic contaminated solutions for controlled adsorption experiments. | For testing and calibrating adsorption performance [15]. |

Spectroscopic and Microscopic Techniques for Characterizing Nanomaterial Surfaces

FAQ: Addressing Common Challenges in Nanomaterial Surface Characterization

Why is surface characterization critical for nanomaterials used in heavy metal adsorption? The physicochemical parameters of nanomaterials, including size, shape, and surface ligands, govern their properties and utilities. For adsorption-based applications like cadmium and lead ion removal, the surface serves as the interface with the external environment, directly controlling solubility, charge density, stability, and binding affinity. Thorough surface characterization helps establish design guidelines to maximize adsorption efficiency and minimize undesirable effects [21].

My NMR signals for surface ligands are broad and weak. What could be the cause? Signal broadening in NMR is a common challenge when characterizing nanomaterial surfaces. This can occur due to two primary reasons:

- Slow Rotational Dynamics: Larger nanoparticles rotate more slowly in solution, leading to faster transversal (T2) relaxation and broader resonance peaks [21].

- Surface Heterogeneity: Ligands bound to the surface experience a different magnetic environment than free ligands. The collective signal from ligands in slightly different chemical environments can appear as a broadened peak [21]. This effect is more pronounced for protons closer to the nanoparticle core and for larger particles, often requiring a higher sample concentration to achieve adequate signal intensity [21].

How can I differentiate between bound ligands and free, unbound ligands in my sample? Diffusion Ordered Spectroscopy (DOSY) NMR is a powerful technique for this purpose. It can differentiate chemical species by their translational diffusion coefficients (DC). Ligands bound to a large nanoparticle will diffuse much more slowly than small, free-floating ligand molecules, allowing you to distinguish and characterize them separately [21].

My DLS results show a much larger size than my TEM measurements. Which one is correct? Both are likely correct, but they measure different properties. TEM provides a direct image of the nanoparticle's core, giving you its physical size and shape. DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter, which is the size of the nanoparticle core plus any surface ligands or coatings and the ion layer moving with it in solution. A significantly larger DLS size can indicate the presence of a thick ligand shell or nanoparticle aggregation [22]. For a complete picture, both techniques should be used together.

Why is it essential to characterize nanoparticles in biologically relevant conditions? Nanoparticles are dynamic, and their properties can change dramatically in different environments. For instance, a study found that a gold colloid exhibited its nominal size in PBS when measured by TEM, but when incubated with human plasma, its DLS-reported size nearly doubled due to protein adsorption forming a "corona." Characterizing nanoparticles in the medium they will be used in (e.g., water, simulated wastewater) is crucial for obtaining clinically or environmentally meaningful data [23].

Troubleshooting Guide for Surface Characterization

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Spectroscopic and Microscopic Characterization

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Broadened/Weak NMR Signals [21] | - Large nanoparticle size- High ligand rigidity- Proximity of ligands to core | - Increase sample concentration- Use smaller nanoparticles (< 5 nm)- Apply advanced NMR (e.g., DOSY, TOCSY) |

| High Endotoxin Contamination [23] | - Non-sterile synthesis/purification- Contaminated reagents/water- "Sticky" nanoparticle surfaces | - Work under sterile conditions (e.g., biosafety cabinet)- Use LAL-grade/pyrogen-free water- Screen commercial reagents for endotoxin |

| Unsharp TEM Images [24] | - Vibration- Specimen too thick- Objective lens contamination- Incorrect focus | - Ensure microscope stability- Prepare thinner specimen sections- Clean objective lens with appropriate solvent- Use fine focus adjustment |

| DLS/Zeta Potential Inconsistencies [23] | - Aggregation in solution- Incorrect dispersing medium pH- Presence of contaminants | - Filter samples to remove aggregates- Measure at physiologically/commercially relevant pH- Ensure solvent purity and use appropriate buffers |

| Artifacts in Electron Micrographs [24] | - Sample preparation errors (e.g., drying, sectioning)- Equipment malfunction | - Follow standardized prep protocols- Regularly maintain and calibrate equipment- Critically compare multiple images |

Standard Operating Protocols for Key Characterization Experiments

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Surface Analysis via NMR Spectroscopy

Objective: To confirm ligand attachment, determine binding mode, and quantify surface ligand density.

Materials & Reagents:

- Purified, ligand-functionalized nanomaterial (e.g., MTAB-functionalized AuNSs) [21]

- Deuterated solvent (e.g., D₂O, CDCl₃) compatible with the nanomaterial dispersion [21]

- NMR tube

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate the nanomaterial dispersion to the maximum possible concentration without causing aggregation. Transfer a sufficient volume to a standard NMR tube [21].

- Data Acquisition:

- Run a standard ¹H NMR spectrum to confirm ligand attachment by comparing functionalized nanomaterial spectra with free ligand spectra [21].

- For advanced structural analysis, acquire 2D-NMR spectra:

- Data Analysis:

Protocol 2: Determining Hydrodynamic Size and Surface Charge via DLS & Zeta Potential

Objective: To measure the nanoparticle size in solution and assess colloidal stability.

Materials & Reagents:

- Stable colloidal dispersion of nanoparticles

- Dispersant (e.g., water, buffer) with known viscosity and refractive index [22]

- Clear, disposable zeta cell/cuvette

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: If necessary, dilute the sample with the dispersant to achieve a concentration within the instrument's ideal detection range to avoid signal saturation from overly concentrated samples [22].

- DLS Measurement:

- Transfer the diluted dispersion to a clean DLS cuvette.

- Equilibrate the sample in the instrument at the desired temperature (typically 25°C).

- Set the instrument parameters (laser wavelength, detector angle, e.g., 173°).

- Run the measurement to obtain the hydrodynamic size (Z-average) and polydispersity index (PDI).

- Zeta Potential Measurement:

- Transfer the sample to a dedicated zeta potential cell equipped with electrodes.

- Apply an electric field across the sample.

- The instrument measures the electrophoretic mobility and calculates the zeta potential using the Henry equation [22].

- Data Analysis:

- A PDI < 0.7 indicates a sufficiently monodisperse sample for DLS analysis.

- Interpret zeta potential results: |ζ| > 30 mV indicates good electrostatic stability [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial Characterization

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Characterization |

|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, CDCl₃) | Provides a signal-free lock for NMR spectroscopy to analyze ligand structure and conformation [21]. |

| LAL-Grade/Pyrogen-Free Water | Used to prepare dispersions and buffers for endotoxin testing and in vitro assays to avoid false immunostimulatory responses [23]. |

| Standard NMR Reference Compounds | (e.g., TMS) Serves as an internal chemical shift reference for quantitative NMR analysis [21]. |

| Activated Carbon Adsorbents | Used in competitive adsorption studies to benchmark the performance of novel nanomaterials for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ removal [25]. |

| Sulfonated Magnetic Alginate Beads | Example of a functionalized nanomaterial used for heavy metal adsorption; characterized by FTIR to confirm surface functionalization [26]. |

Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate characterization technique based on the information you need about your nanomaterial's surface.

Synthesis and Deployment: Advanced Nanomaterials and Their Application in Heavy Metal Sequestration

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides for Cadmium and Lead Ion Removal

FAQ: General Concepts and Material Selection

Q1: What makes nanomaterials effective for adsorbing cadmium and lead ions? Nanomaterials possess exceptional properties for adsorption, including high specific surface area, abundant active sites, and tunable surface chemistry. Their small size and customizable functional groups enable strong interactions with metal ions, such as through complexation, ion exchange, and electrostatic attraction. For instance, bimetallic metal-organic frameworks (BMOFs) exhibit enhanced stability and adsorption capacity due to synergistic effects between two different metal ions in their structure [13].

Q2: How do I choose between carbon nanotubes, metal oxides, and biopolymers for my specific wastewater? The choice depends on your wastewater matrix and treatment goals. Carbon nanotubes are excellent for systems with mixed organic and inorganic pollutants due to their large conjugated π system [27]. Metal oxides like ZnFe₂O₄ are ideal when magnetic separation is desirable for operator-free systems [28]. Biopolymer-based nanomaterials offer the advantage of sustainability and are derived from abundant, low-cost agricultural waste, making them suitable for environmentally conscious applications [6].

Q3: Why is my nanomaterial exhibiting lower adsorption capacity than literature values? This common issue often stems from three main factors: (1) Incomplete activation: Ensure proper functionalization of your nanomaterial's surface groups. (2) pH mismatch: The optimal pH for Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ adsorption is typically between 5-7; verify your solution pH. (3) Material characterization gap: Consistently characterize your synthesized nanomaterials using XRD, SEM, and BET analysis to confirm successful synthesis and surface properties [29] [28].

FAQ: Synthesis and Characterization Issues

Q4: My green-synthesized nanoparticles are aggregating. How can I improve dispersion? Aggregation reduces effective surface area. To improve dispersion: (1) Use appropriate capping agents from plant extracts (e.g., blackberry extract) during synthesis to stabilize nanoparticles [6]. (2) Employ ultrasonication for at least 10-15 minutes before use to break up clusters [28]. (3) Consider functionalization with hydrophilic groups to enhance water compatibility and prevent agglomeration during application.

Q5: How can I confirm successful functionalization of my carbon nanotubes? Characterize using multiple complementary techniques: (1) FTIR to identify new functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine), (2) Raman spectroscopy to examine structural changes in the carbon lattice, (3) XPS for quantitative elemental analysis of surface composition, and (4) TGA to determine the extent of functionalization based on weight loss profiles [27].

FAQ: Experimental Optimization and Performance

Q6: What is the optimal contact time for achieving adsorption equilibrium? Equilibrium time varies by nanomaterial. Recent studies show: magnetic dolomite-quartz nanocomposites reach Pb²⁺ equilibrium in 15-30 minutes [29], while biogenic metal-oxide nanoparticles from sugarcane bagasse achieve Cd²⁺ removal within 10-60 minutes depending on dosage [6]. Conduct kinetic studies with regular sampling at early time points (1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60 min) to determine your system's specific equilibrium time.

Q7: My adsorption capacity decreases significantly after multiple cycles. How can I improve reusability? This indicates inadequate regeneration or material degradation. Implement these solutions: (1) Optimize your desorption protocol using appropriate eluents (e.g., dilute HCl or EDTA solutions) that effectively strip metals without damaging the nanomaterial structure. (2) For magnetic nanomaterials, ensure proper washing with buffer solutions after desorption to neutralize pH before reuse [28]. (3) Characterize spent materials to identify structural degradation that may necessitate material redesign.

Experimental Protocols for Key Nanomaterial Systems

Protocol 1: Green Synthesis of Multicomponent Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles from Sugarcane Bagasse

Application: Removal of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ from marine environments [6]

Materials and Reagents:

- Sugarcane bagasse (dried, ground)

- Blackberry (Rubus glaucus) extract

- NaOH pellets

- H₂O₂ (30% w/w)

- Ethanol (96%)

- Pb(NO₃)₂ and Cd(NO₃)₂·4H₂O for stock solutions

Synthesis Procedure:

- Bagasse Pretreatment: Digest 10g dried sugarcane bagasse in 100mL 2M NaOH at 85°C for 2 hours with stirring. Filter and wash until neutral pH.

- Extract Preparation: Macerate blackberry stems, leaves, and flowers in 40% ethanol (2:1 v/w ratio). Sonicate for 10 minutes (40% amplitude), filter through 0.45μm membrane, and concentrate using rotary evaporation.

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Combine pretreated bagasse with blackberry extract in 3:1 ratio. Maintain at 60°C with continuous stirring for 4 hours.

- Recovery: Centrifuge at 8000rpm for 15 minutes, wash with ethanol, and dry at 40°C for 24 hours.

Characterization:

- XRD: Confirm crystalline phases of Fe₃O₄, ZnO, CaO, and MgO

- SEM/TEM: Analyze morphology and particle size distribution

- EDS: Verify elemental composition

- FTIR: Identify functional groups from plant extract

Protocol 2: Fabrication of HKUST-1/NiSe Coated Fixed-Bed Adsorption Tubes

Application: Zero-waste removal of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ from water samples [1]

Materials and Reagents:

- Copper(II) nitrate trihydrate

- Trimesic acid (H₃BTC)

- Nickel selenide (NiSe) nanoparticles

- DMF and ethanol

- Glass tubes (10cm length, 0.5cm diameter)

Procedure:

- NiSe Synthesis: Prepare NiSe nanoparticles through eco-friendly method using plant-derived reagents as reducing and capping agents.

- HKUST-1 Synthesis: Combine Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O (1.2mmol) and H₃BTC (0.8mmol) in 15mL DMF/ethanol/water (1:1:1) mixture. Heat at 85°C for 20 hours.

- Composite Formation: Blend HKUST-1 with NiSe (3:1 mass ratio) in ethanol using ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- Tube Coating: Activate glass tubes with piranha solution, rinse thoroughly, then coat inner walls with HKUST-1/NiSe composite using vacuum-assisted deposition.

- Activation: Heat coated tubes at 150°C under vacuum for 6 hours to remove solvent molecules.

Characterization:

- BET: Analyze surface area and pore size distribution

- SEM: Examine coating uniformity and thickness

- XRD: Verify preservation of HKUST-1 crystallinity after composite formation

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparison of Nanomaterial Performance for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ Removal

| Nanomaterial | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Optimal pH | Equilibrium Time (min) | Removal Efficiency (%) | Reusability (Cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZF-NPs [28] | Cd²⁺: 152.48 | 6.0 | 15 | >91 | 5 |

| DQ@Fe₃O₄ [29] | Pb²⁺: 476.19, Cd²⁺: 357.14 | 5.0-6.0 | 15-30 | >95 | 4 |

| Sugarcane Bagasse NPs [6] | Pb²⁺: 95.2, Cd²⁺: ~70* | 6.0-7.0 | 10-60 | Pb²⁺: 95-99, Cd²⁺: ~90 | 5 |

| HKUST-1/NiSe [1] | Pb²⁺: ~98, Cd²⁺: ~95 | 5.5-6.5 | <30 | >98 | >5 |

*Values estimated from graphical data

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Enhanced Adsorption Efficiency

| Parameter | Carbon Nanotubes | Metal Oxides | Biopolymers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Dosage | 0.5-1.5 g/L | 0.5-2.0 g/L | 1.0-3.0 g/L |

| Temperature Range | 25-45°C | 25-60°C | 20-40°C |

| Initial Concentration Range | 50-500 mg/L | 20-400 mg/L | 50-300 mg/L |

| Best Fitting Isotherm | Langmuir/Freundlich | Langmuir | Freundlich/Langmuir |

| Best Fitting Kinetics | Pseudo-second-order | Pseudo-second-order | Varies (PFO/PSO) |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanomaterial-Based Heavy Metal Removal Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CH030 Weakly Acidic Resin [30] | Adsorption of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺, Zn²⁺ | Weakly acidic amino phosphonic groups; styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer |

| ZnFe₂O₄ Nanoparticles [28] | Magnetic adsorption of heavy metals and dyes | Spinel structure; magnetic separation; 15min equilibrium |

| Dolomite-Quartz@Fe₃O₄ [29] | Nanocomposite for Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ removal | Natural clay base; Fe₃O₄ incorporation; high adsorption capacity |

| HKUST-1/NiSe [1] | Fixed-bed adsorption system | MOF-semiconductor composite; zero-waste operation; reusable |

| Multicomponent Nanoparticles [6] | Green-synthesized adsorbents from agricultural waste | Contains Fe₃O₄, ZnO, CaO, MgO; eco-friendly; cost-effective |

Experimental Workflows and Conceptual Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Heavy Metal Removal

Adsorption Mechanisms for Heavy Metal Removal

Green Synthesis of Nanomaterials using Plant Extracts and Biowaste

FAQs: Core Concepts and Best Practices

What are the primary advantages of using plant extracts for nanomaterial synthesis over chemical methods? Green synthesis using plant extracts is favored for being eco-friendly, cost-effective, and safe. It eliminates the need for high temperatures, high pressures, and toxic chemical reducing agents. Plant extracts are rich in phytochemicals like flavonoids, polyphenols, and alkaloids, which act as both reducing and stabilizing agents, converting metal ions into stable nanoparticles without producing harmful byproducts [31] [32].

Which plant-based materials are most effective for synthesizing adsorbents for Cadmium (Cd) and Lead (Pb) removal? Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of several biowaste materials. Luffa peels and chamomile flowers, particularly when base-treated, show high adsorption capacities for Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ ions [33]. Other effective agricultural wastes include pistachio shells, peanut shells, and orange fruit waste, which can be used raw or converted into activated carbon to enhance their adsorption properties [34].

Why is the characterization of synthesized nanomaterials and plant extracts critical, and which techniques are essential? Incomplete characterization of plant extracts is a major challenge that hampers the reproducibility and control over nanoparticle morphology [35]. Essential techniques include:

- FTIR (Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy): Identifies functional groups (e.g., -OH, C=O, COO) on the nanomaterial surface that play a role in metal ion binding [33].

- LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) & NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance): Provides detailed phytochemical profiling of plant extracts, enabling a precise understanding of the metabolites involved in synthesis [35].

- ICP-AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy): Accurately measures heavy metal concentrations (e.g., Cd, Pb) in solutions before and after adsorption to quantify removal efficiency [33].

How can I improve the reproducibility and scalability of green synthesis protocols? Reproducibility is often limited by non-standardized extraction methods and variations in plant composition due to seasonality or geography [35] [32]. To address this:

- Protocol Harmonization: Standardize parameters such as plant part used, extraction temperature, solvent, and duration.

- Advanced Analytics: Integrate LC-MS and NMR to fully characterize plant extract composition [35].

- Process Optimization: Utilize computational methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to systematically model and optimize synthesis and adsorption parameters [30] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Adsorption Capacity for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low metal removal efficiency from aqueous solution. | Non-activated adsorbent surface with limited functional groups. | Chemically pre-treat the biowaste. Base treatment (e.g., 0.4 M NaOH) has been shown to enhance the adsorption capacity of materials like luffa peels by activating binding sites [33]. |

| Suboptimal pH of the metal solution. | Adjust the solution pH. Adsorption of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ is typically more effective at neutral to slightly basic pH, as functional groups like -COOH and -OH are deprotonated, facilitating binding. Use buffers (e.g., Tris buffer) for pH control [33]. | |

| Inadequate contact time between adsorbent and metal ions. | Ensure the process follows pseudo-second-order kinetics, which indicates chemosorption is the rate-limiting step. Conduct kinetic studies to determine the optimal contact time for your specific system [33]. |

Inconsistent Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Batch-to-batch variations in nanoparticle size, shape, or yield. | Uncharacterized or variable plant extract composition. | Fully characterize the plant extract using techniques like FTIR and LC-MS to identify the active reducing and capping agents. Standardize the source and preparation method of the plant material [35] [32]. |

| Uncontrolled synthesis parameters (temperature, pH, concentration). | Employ statistical optimization tools like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to identify and control key variables such as metal salt concentration, extract volume, temperature, and pH [30] [34]. | |

| Inadequate purification or calcination step. | Implement a consistent post-synthesis protocol. For example, zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized from broccoli extract require calcination at high temperatures (e.g., 500 °C) to obtain the final crystalline product [36]. |

Challenges in Column-Based Adsorption for Metal Recovery

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid saturation or poor removal efficiency in a packed bed column. | Excessive feed flow rate reducing contact time. | Optimize the flow rate. Simulation and RSM studies indicate that lower flow rates (e.g., around 9.28 L/s in one study) enhance contact time and adsorption efficiency [30]. |

| Insufficient bed height (column length). | Increase the bed height. A greater height (e.g., ~288 cm as found optimal) provides more active sites and increases the residence time of the solution in the column, improving metal removal [30] [33]. | |

| High initial metal concentration leading to rapid saturation. | For concentrated waste streams, consider a pre-dilution stage or use a multi-column setup. The initial metal concentration is often the most influential factor on column performance [30]. | |

| Difficulty in regenerating the adsorbent for reuse. | Inefficient eluent (desorbing agent). | Use an appropriate eluent to recover the metal and regenerate the column. Studies on biowaste adsorbents have shown that metals can be recovered with high efficiency (87-90%) over multiple adsorption-regeneration cycles, though the specific eluent should be determined experimentally [33] [34]. |

Quantitative Data for Adsorption of Cd and Pb

The following table summarizes experimental data for the adsorption of Cadmium and Lead ions using various green nanomaterials and biowastes, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Adsorption Performance of Select Green Adsorbents for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺

| Adsorbent Material | Target Metal | Max. Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Optimal pH | Isotherm Model | Kinetic Model | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamomile Flowers (Base-treated) | Pb²⁺ | 49.5 | ~5.6 | Langmuir/Freundlich | Pseudo-second-order | [33] |

| Luffa Peels (Base-treated) | Pb²⁺ | 34.0 | ~5.6 | Langmuir/Freundlich | Pseudo-second-order | [33] |

| Luffa Peels (Column) | Pb²⁺ | 32.9 (Thomas model) | - | - | - | [33] |

| Luffa Peels (Column) | Cd²⁺ | 25.8 (Thomas model) | - | - | - | [33] |

| CH030 Resin (Column, multi-metal) | Cu, Ni, Cd, Zn | High efficiency achieved* | - | - | Pseudo-second-order | [30] |

| General Biowaste Adsorbents | Cd²⁺ | Generally lower than Pb²⁺ | ~7.0 | Freundlich | Pseudo-second-order | [33] |

The study focused on optimizing operational parameters (bed height, flow rate, concentration) to reduce outlet concentrations to within permissible limits, demonstrating high model fitting (R² > 0.99) [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles using Broccoli Extract

This protocol is adapted from research on creating nanoparticles for energy applications, demonstrating a clear green synthesis pathway [36].

Broccoli Extract Production:

- Thoroughly wash fresh broccoli and dry it in an air fryer or oven at 250 °C for 6 hours.

- Grind 5 grams of the dried broccoli into a powder.

- Mix the powder with 50 mL of distilled water and heat at 60 °C for 1 hour under constant stirring.

- Filter the mixture using Whatman filter paper (110 mm diameter). The resulting clear filtrate is the broccoli extract (BE). Store at 4 °C until use.

Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles:

- Add 10 mL of BE dropwise to 90 mL of distilled water in a beaker.

- Under constant magnetic stirring at room temperature, add 0.1 M zinc acetate dihydrate ((CH₃COO)₂Zn·2H₂O) to the beaker.

- Heat the reaction mixture to 70 °C and maintain with stirring for 3 hours to facilitate the bioreduction. A precipitate will form.

- Dry the precipitate in an oven at 100 °C for 24 hours.

- Grind the dried product into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle.

- Calcinate the powder at 500 °C for 1 hour in a muffle furnace to obtain crystalline ZnO nanoparticles.

Protocol 2: Batch Adsorption Experiment for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ using Biowaste

This protocol is based on studies using biowaste like luffa peels and chamomile flowers for metal removal [33].

Adsorbent Preparation:

- Clean and air-dry the biowaste (e.g., luffa peels, chamomile flowers) for 3-5 days at room temperature.

- Mill the dried material with a mortar and pestle and sieve to a consistent particle size.

- For chemical activation, treat the adsorbent with 0.4 M NaOH or 0.4 M HNO₃, followed by thorough washing and drying.

Adsorption Isotherm Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions (1000 mg/L) of Pb²⁺ from lead nitrate [Pb(NO₃)₂] and Cd²⁺ from cadmium sulfate octahydrate [CdSO₄·8H₂O].

- Create a series of diluted metal solutions (e.g., 10, 20, 50, 100, 250, 500 mg/L) in separate containers.

- Adjust the pH of each solution to the optimal value (e.g., pH 5.6 for Pb²⁺ using acetate buffer; pH ~7.0 for Cd²⁺ using Trizma buffer) [33].

- To each solution, add a known, constant mass of the biosorbent.

- Agitate the mixtures on a shaker for a predetermined time (based on kinetic studies) to reach equilibrium.

- Filter the mixtures and analyze the supernatant for remaining metal ion concentration using Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES).

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Green Nanoparticle Synthesis and Application Workflow

Diagram Title: Green Synthesis to Application Workflow

Heavy Metal Adsorption Mechanisms on Biowaste

Diagram Title: Heavy Metal Adsorption Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Nanomaterial Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Plant/Biowaste Material | Source of phytochemicals for reduction/capping in synthesis, or as adsorbent matrix. | Broccoli for ZnO NP synthesis [36]; Luffa peels and chamomile flowers for Cd/Pb adsorption [33]. |

| Metal Salts | Precursors for nanoparticle synthesis. | Zinc acetate dihydrate for ZnO NPs [36]. Lead nitrate and Cadmium sulfate for adsorption studies [33]. |

| Chemical Treatments (NaOH/HNO₃) | To activate or modify the surface of biowaste adsorbents, enhancing adsorption capacity. | 0.4 M NaOH treatment of luffa peels increased adsorption capacity for Pb²⁺ [33]. |

| Buffer Solutions (Acetate, Trizma) | To control and maintain the pH of the metal solution during adsorption experiments. | Acetate buffer (pH 5.6) for Pb²⁺ solutions; Trizma buffer for Cd²⁺ solutions at various pH [33]. |

| Analytical Instruments (FTIR, ICP-AES) | Characterization of functional groups (FTIR) and quantitative measurement of metal concentrations (ICP-AES). | FTIR identified -OH and C=O groups on luffa peels [33]. ICP-AES measured residual Cd/Pb concentrations [33]. |

| Chelating Resins | Synthetic alternative for high-performance ion exchange and adsorption in column studies. | CH030 resin (weakly acidic, amino phosphonic groups) for removal of Cu, Ni, Cd, Zn [30]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when grafting functional groups onto nanomaterials for enhanced adsorption of cadmium (Cd²⁺) and lead (Pb²⁺) ions.

FAQ 1: Why is my amine-functionalized adsorbent showing lower-than-expected heavy metal adsorption?

- Potential Cause: Incomplete amine functionalization or low grafting density on the nanomaterial surface.

- Solution:

- Verify Functionalization: Confirm the presence and quantity of surface amines using characterization techniques like Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to detect N-H stretches, or X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) for nitrogen elemental analysis [29] [37].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: For NHS-ester chemistry, ensure the reaction is performed in a non-amine buffer (e.g., phosphate, HEPES, or borate buffer) at a pH between 7.2 and 8.5. Avoid Tris or glycine buffers during the reaction, as they will compete for the coupling reagent [38]. Incubate for 0.5 to 4 hours at room temperature or 4°C [38].

FAQ 2: My carboxyl-containing nanoparticles are aggregating during the functionalization process. How can I improve stability?

- Potential Cause: The high surface energy of nanoparticles and the reaction conditions can compromise colloidal stability.

- Solution:

- Use Charged Ligands: Employ coupling agents that introduce electrostatic stabilization. For example, Sulfo-NHS esters contain a sulfonate group that increases the water solubility of the reagents and helps prevent aggregation [38].

- Control Solvent Addition: For water-insoluble NHS-ester reagents, first dissolve them in a water-miscible organic solvent like DMSO or DMF before adding them to the aqueous nanoparticle solution. Keep the final organic solvent concentration low (0.5-10%) to minimize disruption of the aqueous environment [38].

FAQ 3: The coupling efficiency to sulfhydryl (-SH) groups is low. What could be the issue?

- Potential Cause: Oxidation of thiol groups to disulfides or non-optimal reaction pH.

- Solution:

- Use Reducing Agents: Include mild reducing agents like TCEP (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) in the reaction buffer to reduce pre-existing disulfide bonds and maintain thiols in their reactive state.

- pH Control: Maleimide chemistry, a common method for targeting sulfhydryls, is most efficient at a pH between 6.5 and 7.5. Avoid higher pH values ( > 8.0), as this can lead to hydrolysis of the maleimide group and competition from amine reactions [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Two-Step Derivatization of Amine and Carboxyl Groups

This protocol is adapted from a metabolomics study and exemplifies a sequential functionalization approach to modify amine and carboxyl groups on the same molecule, which can be applied to nanomaterial surface engineering [39].

Objective: To sequentially tag primary amine/hydroxyl and carboxylate groups on a surface to enhance hydrophobicity and proton affinity, which can improve performance in analytical separations or adsorption processes [39].

Materials:

- Dimethylaminoacetyl chloride hydrochloride

- N, N-Diethylethylenediamine

- HATU (Hexafluorophosphate Azabenzotriazole Tetramethyl Uronium)

- HOAt (1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole)

- Triethylamine

- Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

- Target analyte or nanomaterial with amine/carboxyl groups

Methodology:

- Chlorination of Reagent: Generate dimethylaminoacetyl chloride by reacting 100 mM dimethylaminoacetyl chloride hydrochloride with thionyl chloride (1:3 mole ratio) in DMF. Add triethylamine to neutralize the solution. Heat to 90-100°C for 45 minutes to remove excess thionyl chloride [39].

- First Derivatization (Amine/Hydroxyl Tagging):

- Add 40 µL of dimethylaminoacetyl chloride to 100 µL of your analytes or nanomaterial suspension in DMSO.

- React at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Quench the reaction with 1.0 µL of H₂O to restore any carboxylates that may have formed unstable anhydrides [39].

- Second Derivatization (Carboxylate Tagging):

- To the same mixture, add 42.0 µL of N, N-Diethylethylenediamine, 60 µL of 500 mM HATU, and 60 µL of 500 mM HOAt.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Place the tube in a vacuum centrifuge until dry and reconstitute in the desired buffer [39].

Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the two-step derivatization process for a molecule containing both amine and carboxyl groups, such as glycine [39].

Quantitative Data on Adsorption Performance

The following table summarizes the adsorption capacities of various functionalized nanomaterials for cadmium and lead ions, as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Adsorption Capacity of Functionalized Nanomaterials for Heavy Metals

| Nanomaterial / Adsorbent | Target Heavy Metal | Reported Adsorption Capacity | Key Functional Groups / Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co0.89Mg0.79Mn1.46O3.98@C (calcined at 600°C) | Cd²⁺ | 280.11 mg/g | Metal oxide framework with carbon composite; high surface area [40]. | |

| Dolomite-Quartz@Fe3O4 Nanocomposite | Cd²⁺ | 21.41 mg/g | Carbonate (CO₃²⁻) and silica (Si–O) groups from natural clay; magnetic separation [29]. | |

| Dolomite-Quartz@Fe3O4 Nanocomposite | Pb²⁺ | 30.12 mg/g | Carbonate (CO₃²⁻) and silica (Si–O) groups from natural clay; magnetic separation [29]. | |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane/Zeolite W Composite | Cd²⁺ | 253.50 mg/g | Amine groups (-NH₂) from silane functionalization [40]. | |

| Alginate/Chitosan Beads | Cd²⁺ | 207.00 mg/g | Amine (-NH₂) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups from chitosan and alginate [40]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Surface Functionalization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Reactive Group | Target on Nanomaterial / Application |

|---|---|---|

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) Esters | Amine-reactive group; forms stable amide bonds. Reacts with primary amines (-NH₂) under physiologic to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7.2-9) [38]. | Lysine residues or surface amines for conjugation; widely used for labeling and crosslinking [38]. |

| Sulfo-NHS Esters | Water-soluble version of NHS esters due to a sulfonate group; cannot cross cell membranes [38]. | Ideal for functionalizing the external surface of nanoparticles or cells in aqueous environments without internalization [38]. |

| HATU | Peptide coupling reagent; activates carboxyl groups for efficient amide bond formation with amines [39]. | Coupling carboxylated surfaces to amine-containing ligands; used in the second step of the dual derivatization protocol [39]. |

| Imidoesters | Amine-reactive group; forms amidine bonds upon reaction with primary amines. Charge-neutral after reaction [38]. | Protein crosslinking and immobilization while maintaining the original charge of the amine. |

| Maleimides | Sulfhydryl-reactive group; forms stable thioether bonds. Highly specific for thiols (-SH) at pH 6.5-7.5 [38]. | Conjugation to cysteine residues or thiolated surfaces for controlled, site-specific bioconjugation. |

| Dolomite-Quartz Clay | Natural, eco-friendly adsorbent matrix containing carbonate (CO₃²⁻) and silica (Si–O) functional groups [29]. | Serves as a low-cost, sustainable base material for creating nanocomposite adsorbents for heavy metal removal [29]. |

| Tartaric Acid & PEG 400 | Chelating agent and crosslinker, respectively, in the Pechini sol-gel synthesis method [40]. | Used for the controlled synthesis of homogeneous metal oxide nanocomposites with high purity [40]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Adsorption Research

FAQ 1: Why is my nanomaterial's adsorption capacity lower than expected in real wastewater compared to synthetic solutions?

This is a common issue often caused by the complex matrix of industrial effluents. Several factors can contribute to reduced performance:

- Competing Ions: Real wastewater contains various other metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Ni²⁺) and dissolved salts that compete with Cd(II) and Pb(II) for binding sites on the nanomaterial. The ionic strength can shield the electrostatic interactions, reducing uptake.

- pH Variability: The adsorption of heavy metal ions is highly pH-dependent. Industrial effluent pH can fluctuate and often be acidic, which can protonate the active sites on the adsorbent (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl groups), reducing their affinity for metal cations. For instance, Cd(II) removal by Na-X zeolite was significantly higher at pH 5.0 than at pH 3.0 [8].

- Organic Matter: Natural organic matter (NOM) can foul the nanomaterial's surface, blocking pores and active sites. It can also form complexes with the target metals, altering their speciation and bioavailability for adsorption.

- Incorrect Performance Measurement: A frequent mistake in adsorption studies is expressing performance solely as percentage removal (% removal). This metric is highly dependent on the initial concentration. The adsorption performance should be primarily expressed as the equilibrium adsorption capacity (qₑ in mg/g), calculated as qₑ = (C₀ - Cₑ) * V / m, where C₀ and Cₑ are the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), V is the solution volume (L), and m is the adsorbent mass (g) [41].

Solution: Conduct a comprehensive characterization of the real wastewater (pH, ionic strength, competing ions, organic content). Pre-treatment steps such as pH adjustment or filtration may be necessary. Always use qₑ (mg/g) for capacity comparison and report % removal alongside it for context.

FAQ 2: My adsorption kinetics are too slow for practical application. How can I improve them?

Slow kinetics can stem from mass transfer limitations or suboptimal experimental conditions.

- Mass Transfer Resistance: If the adsorption sites are primarily within the particle's pores, diffusion can be the rate-limiting step. This is particularly relevant for microporous materials.

- Incorrect Kinetic Modeling: A common error is to force-fit all data to a Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) model. The PSO model is often applicable, but the Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) model may be better for systems with low initial concentrations and short contact times [8]. The initial contact time data is critical for identifying the correct model; a breakpoint in the t/qₜ vs. t plot can indicate multiple adsorption sites or diffusion control [41].

- Agitation Speed: In batch systems, insufficient agitation can create a stagnant liquid film around the adsorbent particles, limiting the transport of metal ions to the surface.

Solution:

- Nanomaterial Design: Use materials with hierarchical pore structures (mix of micro- and mesopores) to facilitate faster intraparticle diffusion. Composite materials, like HKUST-1/NiSe, can enhance kinetics by providing more accessible active sites [1].

- Optimize Conditions: Increase agitation speed to minimize the liquid film boundary layer. Ensure the solution pH is optimized for rapid adsorption.

- Correct Modeling: Fit kinetic data using non-linear optimization techniques rather than linearized forms of models to obtain more accurate parameters. Use statistical metrics to identify the best-fit model [41].

FAQ 3: How do I prevent secondary waste and manage spent adsorbent?

A key challenge in adsorption technology is the disposal or regeneration of nanomaterial-laden heavy metals.

- Problem of Sludge: Conventional chemical precipitation, while effective, generates large amounts of hazardous sludge that requires costly disposal [42] [1].

- Nanoparticle Release: Using nanomaterial powders in batch systems requires subsequent separation steps (filtration, centrifugation), which can be challenging and risk nanoparticle leakage into the environment.

Solution:

- Fixed-Bed Columns: Immobilize the nanomaterial in a fixed-bed column. This prevents the need for post-separation and allows for continuous operation. A study coated a HKUST-1/NiSe nanocomposite onto the inner wall of a glass tube, creating an integrated system that avoids secondary waste [1].

- Magnetic Recovery: Use magnetic nanomaterials (e.g., Fe₃O₄). After adsorption, an external magnetic field can easily separate the spent adsorbent from the treated water [6].

- Regeneration and Reuse: Develop regeneration protocols. Spent adsorbents can often be regenerated by washing with a mild acid (e.g., 0.1M HNO₃) or a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) to desorb the metals, allowing both adsorbent reuse and metal recovery. The stability of the material over multiple adsorption-desorption cycles must be evaluated.

FAQ 4: My chromatographic separation for analysis shows poor resolution of metal ions. What could be wrong?

Poor resolution in column-based separations affects both analytical accuracy and preparative recovery.

- Stationary Phase: The choice of stationary phase (the adsorbent packed in the column) may not be selective enough for the target metals under your operating conditions.

- Mobile Phase: The pH, ionic strength, and composition of the eluent (mobile phase) are critical. An inappropriate eluent strength can cause peak tailing, broadening, or overlapping [43].

- Column Packing: Poorly packed columns with channels or air bubbles lead to uneven flow and band broadening, severely reducing resolution.

- Flow Rate: A flow rate that is too high does not allow sufficient time for equilibrium between the mobile and stationary phases, reducing separation efficiency.

Solution:

- Evaluate the chromatogram to calculate parameters like retention time, peak width, and resolution factor [43].

- Optimize the mobile phase composition (e.g., use a gradient elution with a complexing agent) and pH to improve selectivity.

- Ensure the column is properly packed and conditioned. Adjust the flow rate to find the optimum for your specific system.

Detailed Protocol: Batch Adsorption Experiment for Cd(II) and Pb(II)

Objective: To determine the adsorption capacity and kinetics of a nanomaterial for Cd(II) and Pb(II) removal from aqueous solution.

Materials:

- Adsorbent: Nanomaterial (e.g., HKUST-1/NiSe nanocomposite, sugarcane-bagasse-derived Fe₃O₄–ZnO–CaO–MgO, or Na-X zeolite).

- Stock Solutions: 1000 mg/L Cd(II) and Pb(II) prepared from CdCl₂/Cd(SO₄) and PbCl₂/Pb(NO₃)₂ in ultrapure water.

- Equipment: Orbital shaker, centrifuge, pH meter, ICP-MS or AAS for metal analysis.

Methodology: