Optimizing Sample-to-Headspace Volume Ratio: Strategies for Enhanced Sensitivity in GC Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the sample-to-headspace volume ratio in static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC).

Optimizing Sample-to-Headspace Volume Ratio: Strategies for Enhanced Sensitivity in GC Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the sample-to-headspace volume ratio in static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC). Covering foundational theory, practical methodology, advanced troubleshooting, and validation techniques, it details how the phase ratio (β) critically impacts analytical sensitivity and reproducibility. Readers will learn to apply key principles and modern experimental design (DoE) approaches to overcome matrix effects and method variability, enabling robust quantification of volatile compounds in pharmaceuticals, biological, and complex aqueous samples for improved regulatory compliance and research outcomes.

Understanding Headspace Fundamentals: The Science of Phase Ratio and Partition Coefficient

Core Principles of Static Headspace Analysis and Equilibrium

Static Headspace Analysis is a foundational technique in gas chromatography (GC) for analyzing Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) present in a sample. The core principle involves heating a sealed sample vial to allow volatile analytes to partition from the sample matrix into the gas phase, or headspace, above it. Once equilibrium is established, a portion of this headspace is injected into the GC for analysis [1]. This technique is indispensable in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and food and beverage analysis due to its clean sample introduction and minimal preparation requirements [2].

This guide details the core principles, provides optimization strategies with a focus on sample-to-headspace volume ratios, and offers troubleshooting FAQs to support researchers in method development.

Core Principles and Mathematical Foundation

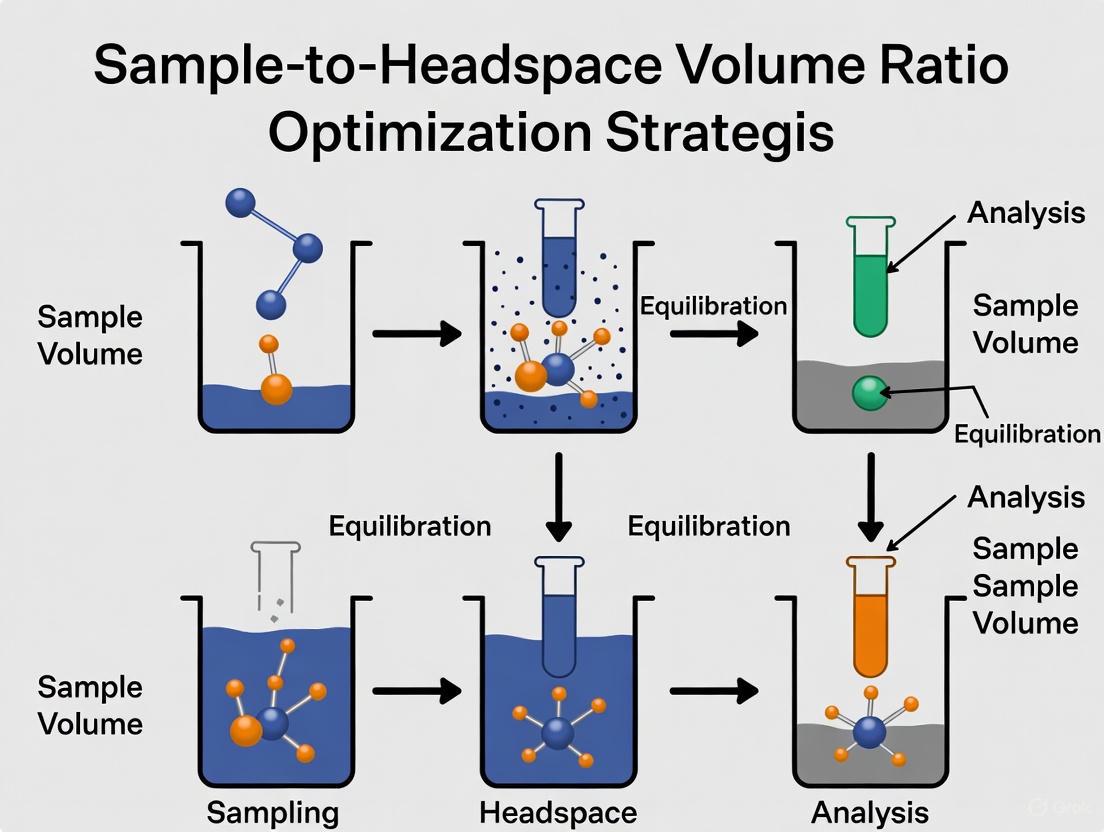

The entire process of static headspace analysis is governed by the goal of achieving a thermodynamic equilibrium between the analyte concentration in the sample phase and the gas phase [3]. The following diagram illustrates this process and the key parameters influencing the final result.

The fundamental relationship between the original sample concentration and the concentration detected by the GC is described by the following equation [2] [4] [5]:

CG = C0 / (K + β)

Where:

- C_G: Concentration of the analyte in the gas phase (headspace)

- C_0: Original concentration of the analyte in the sample

- K: Partition coefficient (CS / CG), representing the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase to its concentration in the gas phase at equilibrium [5]

- β: Phase ratio (VG / VL), the ratio of the headspace gas volume to the sample liquid volume [2]

The detector response (peak area, A) is directly proportional to C_G. Therefore, to maximize sensitivity, the sum (K + β) must be minimized [2]. The variables K and β are the primary levers for method optimization.

Key Optimization Parameters and Experimental Protocols

Optimizing a static headspace method involves systematically investigating several interdependent parameters. The following table summarizes the key parameters and their effects on the analysis.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimizing Static Headspace Analysis

| Parameter | Effect on Analysis | Optimization Guidelines | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume & Phase Ratio (β) [2] [4] | A lower β (more sample, less headspace) increases C_G for analytes with low K values. Has minimal effect for high K analytes. | Use a 10 mL sample in a 20 mL vial (β=1) as a starting point. Ensure at least 50% headspace remains [2] [6]. | Method: Prepare a series of vials with increasing sample volumes (e.g., 2, 5, 10 mL) in 20 mL vials, keeping C_0 constant. Analysis: Inject and compare peak areas. The volume yielding the highest response for the target analytes is optimal. |

| Equilibration Temperature [2] [4] [3] | Increasing temperature decreases K for most analytes, driving them into the headspace and improving sensitivity. | Set oven temperature to ~20°C below the solvent's boiling point [6]. Accuracy of ±0.1°C is critical for precise results with high K analytes [4]. | Method: Analyze identical samples at different equilibration temperatures (e.g., 40, 60, 80°C) for a fixed time. Analysis: Plot peak area vs. temperature. The point where the response plateaus is optimal. Monitor for analyte degradation. |

| Equilibration Time [4] [3] | Time required for analytes to reach equilibrium between the sample and gas phase. Insufficient time causes poor reproducibility. | Must be determined experimentally for each analyte/matrix combination. Agitation can significantly reduce the time required [3]. | Method: Analyze identical samples with increasing equilibration times (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 30, 45 min) at a fixed temperature. Analysis: Plot peak area vs. time. The minimum time after which the area becomes constant is the optimal equilibration time. |

| Salting-Out [4] [5] [6] | Adding salt to aqueous samples reduces the solubility of polar analytes (decreases K), pushing them into the headspace. | Saturate the aqueous sample with a salt like potassium chloride or sodium chloride [5]. Test for unwanted co-extraction of matrix compounds [6]. | Method: Prepare sample aliquots with different concentrations of salt (0%, 10%, 25%, saturation). Analysis: Compare peak areas. Salt concentration giving the highest response without increasing interference is optimal. |

The Role of the Partition Coefficient (K)

The partition coefficient is a critical factor. Its value dictates how an analyte will respond to changes in other parameters [5]:

- High K value (~500): Indicates the analyte favors the sample phase (e.g., ethanol in water). For such analytes, increasing the temperature is the most effective way to improve headspace concentration, while increasing sample volume has little effect [4].

- Low K value (~0.01): Indicates the analyte strongly favors the gas phase (e.g., hexane in water). For these, increasing the sample volume provides a significant boost to C_G [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Static Headspace Analysis

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Container for sample and headspace gas [2]. | Common sizes are 10 mL and 20 mL. Choose size based on desired phase ratio (β). |

| Septra & Caps | Provides a gas-tight seal for the vial [2]. | Must be compatible with high incubation temperatures to prevent degradation and leakage [3] [6]. |

| Non-Volatile Salts (e.g., KCl, NaCl) | Used for "salting-out" to improve volatility of polar analytes in aqueous matrices [4] [6]. | Purity is critical to avoid introducing contaminants. Efficiency is salt and analyte-specific. |

| Headspace Syringe / Autosampler | To withdraw and inject a precise aliquot of the headspace gas [3]. | Automated systems provide superior precision and accuracy compared to manual injection. |

| Narrow Bore GC Inlet Liner | The interface where the sample is introduced into the GC [6]. | A narrow bore liner (e.g., 1.2 mm ID) prevents band broadening, resulting in sharper peaks and better signal [6]. |

Troubleshooting Common Static Headspace Issues: FAQs

Q1: My analysis is suffering from poor sensitivity. What are the primary parameters I should adjust? [7] [8]

- Increase Incubation Temperature: This is the most effective step for analytes with high partition coefficients (K), as it drives more analyte into the headspace [2] [4].

- Adjust Phase Ratio (β): For analytes with low K values, increasing the sample volume in a given vial will lower β and increase the signal [2] [4].

- Employ Salting-Out: For polar analytes in aqueous solutions, saturating the sample with salt can dramatically decrease K and improve sensitivity [4] [6].

- Check Instrument Settings: Ensure the sample transfer line and valve temperatures are at least 20°C hotter than the incubation oven to prevent sample condensation, which causes loss of analyte [4] [6].

Q2: I am seeing inconsistent (poor precision) results between replicate samples. What could be the cause? [3] [8]

- Insufficient Equilibration Time: Ensure the method allows enough time for the slowest analyte to reach equilibrium. This must be determined experimentally [4] [3].

- Poor Temperature Control: The equilibration oven must have excellent temperature stability (±0.1°C for high K analytes). Verify calibration regularly [4] [3].

- Variable Sample Volume/Vial Size: Inconsistent sample pipetting or using different vial sizes will change the phase ratio (β), leading to irreproducible results. Standardize volumes and vials [2].

- Leaky Vials: Ensure caps are crimped correctly and consistently, and that septa are not compromised by excessive temperature or needle punches [3] [6].

Q3: My chromatogram shows broad peaks or peak splitting. How can I resolve this? [3] [6]

- Use a Narrow Bore Inlet Liner: This is a common solution. A liner with a small internal diameter (e.g., 1.2 mm) reduces band broadening and sharpens peaks [6].

- Apply Inlet Splitting: If sensitivity allows, using a split injection (e.g., 10:1 split ratio) can improve peak shape and reproducibility [4] [6].

- Optimize Pressurization: In automated systems, a reverse flow of gas upon needle insertion can cause an early, partial injection, leading to peak splitting. Optimize pressurization delay and pressure to ensure a single, sharp injection [3].

Q4: When should I consider using Dynamic Headspace over Static Headspace? [1] [7]

Static headspace is simple and robust for many applications. However, consider dynamic headspace (DHS) when:

- Analyzing trace-level compounds requiring superior sensitivity, as DHS concentrates analytes on a trap [1] [7].

- Dealing with complex solid matrices or polar analytes in polar matrices that static headspace cannot efficiently extract [7].

- The target analytes have very low volatility and are not effectively transferred to the headspace under standard static conditions [7].

In static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC), the phase ratio (β) is a fundamental design parameter that critically influences the sensitivity, precision, and overall success of the analytical method. For researchers and scientists optimizing sample-to-headspace volume ratios, a precise understanding of β is indispensable. This guide provides a detailed definition of the phase ratio, explores its role within the headspace system, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols to enhance method development for drug development professionals.

What is the Phase Ratio (β) in Headspace Analysis?

The phase ratio (β) is defined as the ratio of the volume of the gas phase (VG) to the volume of the liquid sample phase (VL) in a sealed headspace vial [9].

β = VG / VL

This ratio is a key determinant of the concentration of an analyte in the headspace gas (CG) at equilibrium, and consequently, of the signal intensity measured by the gas chromatograph [9]. The relationship between the original sample concentration (C0), the gas-phase concentration (CG), the partition coefficient (K), and the phase ratio (β) is given by the fundamental headspace equation [9] [4]:

CG = C0 / (K + β)

- CG: Concentration of the analyte in the gas phase (headspace)

- C0: Original concentration of the analyte in the liquid sample

- K: Partition coefficient (K = CS/CG), which is the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase (CS) to its concentration in the gas phase at equilibrium [9]

- β: Phase ratio (VG/VL)

The following diagram illustrates the core relationships within a headspace vial that determine analyte concentration.

Troubleshooting Common Phase Ratio and Headspace Issues

FAQ: Addressing Frequent Challenges

1. My analysis shows poor repeatability (large variability in peak areas). Could the phase ratio be involved? While poor repeatability is often linked to temperature inconsistencies or vial leaks, an inconsistent sample volume directly changes the phase ratio (β) from vial to vial, leading to variable headspace concentrations [10] [9].

- Solution: Standardize your sample preparation procedure. Use precise, automated pipettes to ensure the same sample volume (VL) is introduced into every vial. This maintains a constant β and improves precision [10].

2. I am getting low peak areas for a soluble analyte. How can I improve sensitivity? For analytes with a high partition coefficient (K >> β), which are highly soluble in the sample matrix, simply increasing the sample volume (and thus decreasing β) has a negligible effect on the headspace concentration [4]. The system is dominated by the partition coefficient.

- Solution: Increase the incubation temperature to decrease the value of K, which will drive more analyte into the headspace [4]. Alternatively, use salting-out techniques (e.g., adding NaCl) to reduce the solubility of polar analytes in aqueous matrices [11] [4] [7].

3. For my insoluble analyte, the signal is weak. Will increasing the sample volume help? Yes. For analytes with a low partition coefficient (K << β), which have low solubility in the matrix, increasing the sample volume (decreasing β) will result in a significant, nearly proportional increase in the headspace concentration (CG) and a stronger signal [4].

4. What is the risk of using a very small sample volume in a large vial? A very small VL creates a large phase ratio (β). According to the equation CG = C0 / (K + β), a large β can lead to a very low headspace concentration (CG) for all analytes, potentially resulting in poor sensitivity and signals that are below the detection limit of your instrument.

Experimental Protocols for Phase Ratio Optimization

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Sample Volume and Phase Ratio

This protocol is designed to empirically determine the optimal sample volume for maximizing sensitivity for your specific analytes.

1. Objective: To determine the effect of sample volume (VL) and the resulting phase ratio (β) on the chromatographic peak area of target analytes.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| 20 mL Headspace Vials | Standard enclosure for maintaining equilibrium between liquid and gas phases. |

| PTFE/Silicone Septa & Crimp Caps | Ensure a gas-tight seal to prevent analyte loss. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Provides highly precise and reproducible sample volume transfers. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | "Salting-out" agent used to improve partitioning of polar analytes into the gas phase [11] [12]. |

| Internal Standard | A compound added in constant amount to all vials to correct for instrumental variability. |

3. Methodology: a. Prepare a standard solution of your target analytes at a concentration relevant to your application. b. Using an automated pipette or liquid handler, dispense this standard solution into a series of 20 mL headspace vials at different volumes (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, and 10.0 mL). For consistency, keep the concentration of any added salt or solvent constant. c. Seal all vials immediately. d. Analyze all samples using the same, controlled HS-GC method (constant temperature, equilibration time, etc.). e. Measure the peak areas for each analyte at each sample volume.

4. Data Analysis: Plot the peak area of each analyte against the sample volume (VL) or the calculated phase ratio (β = (20 - VL)/VL). The optimal volume is the one that provides the best sensitivity without negatively impacting the separation or the linearity of the method. The data can be summarized as follows:

Table 1: Sample Data for Phase Ratio Optimization (Theoretical Data)

| Sample Volume (VL in mL) | Phase Ratio (β) | Peak Area - Analyte A (High K) | Peak Area - Analyte B (Low K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 39.0 | 1,500 | 85,000 |

| 1.0 | 19.0 | 2,900 | 89,500 |

| 2.0 | 9.0 | 5,100 | 92,000 |

| 5.0 | 3.0 | 9,800 | 94,800 |

| 10.0 | 1.0 | 12,500 | 96,200 |

Protocol 2: Investigating the Interaction of Temperature and Phase Ratio

This protocol uses a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to efficiently understand interactive effects.

1. Objective: To model the interactive effects of equilibration temperature and sample volume/phase ratio on extraction efficiency.

2. Methodology: a. As demonstrated in a 2025 study on volatile petroleum hydrocarbons, a Central Composite Face-centered (CCF) design can be employed [11]. b. Select two factors: Equilibration Temperature (e.g., low: 40°C, center: 60°C, high: 80°C) and Sample Volume (e.g., low: 2 mL, center: 5 mL, high: 8 mL). c. The experimental software (e.g., Minitab) will generate a series of runs with different combinations of these two factors. d. The response variable is the chromatographic peak area, normalized per microgram of analyte [11]. e. Execute the experiments and use analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant main and interaction effects.

3. Expected Outcome: The model will reveal whether temperature and phase ratio act independently or synergistically. For example, it may show that for a soluble analyte (high K), increasing temperature is the most critical factor, while for an insoluble analyte (low K), optimizing the sample volume is more impactful.

Key Optimization Parameters and Their Effects

Table 2: Guide to Parameter Optimization Based on Analyte Type

| Parameter | Effect on System | Recommendation for High K (Soluble) Analytes | Recommendation for Low K (Insoluble) Analytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume (VL) | Directly sets the phase ratio (β). | Minimal impact on sensitivity. Use a consistent, moderate volume (e.g., 5-10 mL in a 20 mL vial) [4]. | Critical. Increase sample volume (decrease β) for a significant sensitivity gain [4]. |

| Equilibration Temperature | Decreases the partition coefficient (K). | Critical. Increase temperature to drive more analyte into the headspace. Requires very precise control (±0.1°C) for good precision [9] [4]. | Lesser effect. Increasing temperature may have a minor or even slightly negative impact. |

| Salting-Out | Reduces K for polar analytes in aqueous matrices. | Highly recommended. Adding salts like KCl or NaCl improves volatility and sensitivity [4] [12] [7]. | Not typically required, as analyte is already volatile. |

| Agitation | Increases mass transfer, reducing equilibration time. | Use to speed up analysis, especially for viscous samples [7]. | Use to speed up analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the partition coefficient (K) in headspace analysis? The partition coefficient (K) is a fundamental equilibrium constant in static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC). It is defined as the ratio of an analyte's concentration in the sample (liquid or solid) phase to its concentration in the gas (headspace) phase at equilibrium: K = C~S~/C~G~, where C~S~ is the concentration in the sample phase and C~G~ is the concentration in the gas phase [13] [4]. A high K value indicates that the analyte is more soluble in the sample matrix and has a lower tendency to partition into the headspace, whereas a low K value suggests high volatility and a greater presence in the gas phase.

How does the partition coefficient (K) differ from the distribution coefficient (D)? The partition coefficient, often denoted as log P, refers specifically to the concentration ratio of the un-ionized form of a compound between two phases. In contrast, the distribution coefficient (D, or log D) represents the ratio of the sum of the concentrations of all forms of the compound (ionized plus un-ionized) in each of the two phases. Therefore, log D is pH-dependent and provides a more comprehensive picture for ionizable compounds, whereas log P is constant for a given system [14] [15].

Why is understanding the partition coefficient critical for optimizing my headspace methods? The partition coefficient directly determines the analytical sensitivity of your headspace method. It governs the equilibrium concentration of an analyte in the headspace, which is what the GC instrument measures. A clear understanding of K allows you to predict how changes in method parameters (like temperature or sample volume) will affect the signal. Optimizing these parameters to minimize K for your analytes or to adjust the phase ratio (β) is the key to achieving high sensitivity and robust performance [13] [4].

How do temperature and sample volume affect the headspace equilibrium? The effects of temperature and sample volume are highly dependent on the value of the partition coefficient (K) [13] [4]. The relationship is summarized in the table below.

Table: Effect of Method Parameters Based on Analyte Partition Coefficient (K)

| Method Parameter | Effect on Analytes with High K (e.g., Ethanol in water) | Effect on Analytes with Low K (e.g., Hexane in water) |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Increase | Significantly increases headspace concentration. Requires very precise temperature control (±0.1°C) for good precision [4]. | Minor effect; can sometimes even reduce headspace concentration. |

| Sample Volume Increase | Negligible effect on headspace concentration [4]. | Significantly increases headspace concentration [4]. |

Troubleshooting Common Headspace Issues

Problem: Poor Repeatability (Large variability in peak areas)

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete Equilibrium: Ensure sufficient incubation time (typically 15-30 minutes) to reach a stable gas-liquid equilibrium [10].

- Temperature Instability: The vial thermostat temperature must be consistent and accurate. For analytes with high K, even a 1-2°C shift can cause a 10% change in peak area [13] [4]. Calibrate the heater and ensure vials are equilibrated fully.

- Vial Leakage: Check for worn septa or overused caps. Always use certified vials and replace septa regularly [10].

- Inconsistent Sample Prep: Standardize sample volume, salt addition, and agitation procedures to ensure identical matrix conditions across vials [10].

Problem: Low Peak Area or Reduced Sensitivity

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- High K Value / Low Volatility: The analyte may be too soluble in the sample matrix.

- Solution: Increase the incubation temperature to drive more analyte into the gas phase [4] [10].

- Solution: Use the "salting-out" effect by adding a high concentration of salt (e.g., KCl or NaCl) to the aqueous sample. This reduces the solubility of polar analytes, lowering K and increasing headspace concentration [4] [11].

- Solution: For analytes with intermediate K values (~10), increasing the sample volume can improve headspace concentration [4].

- System Leaks: Check for leaks in the vial septa, headspace sampling needle, transfer line, or inlet [10].

- High K Value / Low Volatility: The analyte may be too soluble in the sample matrix.

Problem: High Background or Ghost Peaks

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Contamination: Contamination can originate from the injection needle, carrier gas, inlet liner, or even the vials themselves.

- Solution: Run blank samples to identify the source. Clean the injection system regularly and use high-purity, pre-cleaned vials. Replace inlet liners and condition the column as needed [10].

- Carryover: Ensure the autosampler needle is properly purged between samples. Increase the cleaning cycle or needle purge time if necessary [10].

- Contamination: Contamination can originate from the injection needle, carrier gas, inlet liner, or even the vials themselves.

Problem: Target Volatile Compounds Not Detected

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Strong Matrix Binding: The analyte may be tightly bound to a solid or complex sample matrix.

- Solution: Increase the incubation temperature and time to enhance release [10].

- Solution: For solid samples, consider a phase transfer catalyst or switch to a dynamic headspace or SPME technique which can be more efficient for exhaustive extraction [13] [10].

- Solution: Adjust the sample pH to convert ionic species into their neutral, more volatile form (e.g., for organic acids, lower the pH) [15].

- Strong Matrix Binding: The analyte may be tightly bound to a solid or complex sample matrix.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Optimal Equilibration Time

A critical step in any headspace method is ensuring the system has reached equilibrium.

- Preparation: Prepare multiple identical samples in headspace vials.

- Incubation: Place all vials in the autosampler and set a starting equilibration time (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Analysis: Analyze one vial and note the peak area of the target analyte.

- Iteration: Repeat the analysis on a new vial at progressively longer time intervals (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 minutes).

- Determination: Plot the measured peak area versus equilibration time. The equilibration time is sufficient when the peak area reaches a stable plateau. Use this time, plus a small safety margin, for your final method [10].

Protocol: Optimizing Parameters via Experimental Design (DoE)

Traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) optimization is inefficient. A Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, as demonstrated in recent research, allows for the simultaneous optimization of multiple interacting parameters [11].

- Select Critical Factors: Identify key variables such as Incubation Temperature (°C), Equilibration Time (min), and Sample Volume (mL).

- Define Ranges: Set realistic low, medium, and high levels for each factor based on preliminary experiments.

- Create a Design Matrix: Use a statistical software package to generate an experimental design (e.g., a Central Composite Face-centered design). This dictates the specific combination of settings for each experimental run.

- Execute and Analyze: Run the experiments in the randomized order specified by the design. Use the chromatographic peak area as the response variable.

- Build a Model: Statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA) will identify which factors and their interactions have a significant impact on the response.

- Find the Optimum: The model can predict the combination of temperature, time, and sample volume that will yield the maximum peak area and sensitivity for your target analytes [11].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this systematic optimization process.

Diagram: Experimental Design for Headspace Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Headspace-GC Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol & Water | Used to determine the octanol-water partition coefficient (K~ow~), a key predictor of a solute's lipophilicity/hydrophobicity and its partitioning behavior [14] [15]. |

| Headspace Vials (20 mL) | Gas-tight vials with precise volumes to contain the sample and maintain equilibrium. Consistent vial volume is critical for controlling the phase ratio (β) [13]. |

| PTFE/Silicone Septa & Crimp Caps | Provide a hermetic seal to prevent loss of volatile analytes and maintain pressure integrity during incubation and sampling [10] [11]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) / Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Inorganic salts used for "salting-out." Their high concentration in aqueous samples reduces the solubility of organic analytes, lowering K and enhancing their concentration in the headspace [4] [11]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., deuterated analogs) | Compounds added in a constant amount to every sample and standard. Used to correct for analytical variability (injection volume, matrix effects) and improve quantitative accuracy. |

The Fundamental Headspace Equation

In static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC), the detector response is fundamentally governed by the equilibrium established between the sample and the vapor phase above it in a sealed vial. This relationship is described by the equation:

A ∝ CG = C0 / (K + β) [16] [13] [17]

Where:

- A is the peak area obtained from the GC detector, which is proportional to the analyte concentration in the gas phase (CG) [16].

- C0 is the original concentration of the analyte in the sample solution [16] [4].

- K is the partition coefficient (also called distribution coefficient), defined as K = CS / CG, representing the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the sample phase (CS) to its concentration in the gas phase (CG) at equilibrium [16] [13].

- β is the phase ratio, defined as β = VG / VS, which is the ratio of the volume of the headspace gas (VG) to the volume of the sample (VS) [16] [13].

To maximize the detector signal (A), the goal is to maximize CG. This is achieved by minimizing the sum (K + β) in the equation's denominator [16] [17]. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the headspace equation and the key parameters that influence it.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Problems and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Sensitivity (Small peak areas) [6] | Analyte too soluble in matrix (High K) [13]. | Check analyte polarity vs. matrix. Review K values if known. | Increase equilibration temperature [16] [13]. Use salting-out effect (add salt) [6] [4]. |

| Unfavorable phase ratio (High β) [16]. | Calculate β (VG/VS). Is sample volume too small? | Increase sample volume to decrease β [16] [4]. | |

| Poor Precision (High %RSD) [4] | Inconsistent temperature control [13]. | Monitor oven temperature stability. | Ensure precise and stable vial thermostatting [4]. |

| Leaky vials or inconsistent sealing [6]. | Check crimp cap consistency; inspect septa. | Use quality vials/septa; ensure crimper is correctly adjusted [16] [6]. | |

| Variable sample volume [17]. | Review sample preparation pipetting technique. | Use precise liquid handling equipment; maintain consistent volume [17]. | |

| Long Equilibration Times | Low temperature or no agitation [16]. | Check if peak areas plateau over time. | Optimize equilibration time experimentally; use vial shaking if available [16]. |

| Peak Tailing | Sample condensation in transfer line [4]. | Verify transfer line temperature. | Set transfer line temperature 20°C above oven temperature [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does temperature precisely affect the headspace analysis for different types of analytes? The effect is highly dependent on the analyte's solubility in the sample matrix (its K value) [13]. For analytes with high solubility (high K, like ethanol in water), even a small temperature increase significantly reduces K and dramatically increases the peak area. For these, temperature control must be very precise (±0.1 °C) [13] [4]. For analytes with low solubility (low K, like n-hexane in water), temperature has a much smaller effect on the peak area [13].

Q2: My sample volume is limited. How can I maintain good sensitivity? Using a smaller vial size is the most effective strategy. For example, transferring a 1 mL sample from a 20 mL vial (β=19) to a 10 mL vial (β=9) significantly reduces the phase ratio, thereby increasing CG and sensitivity [16]. Ensure at least 50% of the vial volume is headspace for proper equilibration [16] [6].

Q3: What is the "salting-out" effect and when should I use it? Salting-out involves saturating an aqueous sample with a salt like sodium chloride. This reduces the solubility of polar organic analytes in the water, decreasing their K value and forcing more analyte into the headspace vapor, which increases sensitivity [6] [4]. It is most effective for polar analytes in aqueous matrices and may have little effect on analytes that already have a very low K [6].

Q4: Why is the solvent peak so small in headspace-GC compared to direct liquid injection? In headspace-GC, only the volatile components that have partitioned into the gas phase are introduced into the instrument. The bulk of the non-volatile or less-volatile solvent remains in the sample vial. This results in a much smaller solvent peak, minimizing its potential to interfere with the analysis of early-eluting target analytes [16] [18].

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Headspace Parameters Using a DoE Approach

The following workflow outlines a robust methodology for optimizing headspace parameters, moving beyond the traditional one-variable-at-a-time approach to capture interaction effects [11].

Detailed Methodologies:

Factor Definition: Identify and set realistic ranges for critical parameters. A typical screening experiment might include:

- Sample Volume (V): For a 20 mL vial, test 2 mL, 5 mL, and 10 mL [16] [4].

- Equilibration Temperature (T): Test a range, ensuring it stays ~20°C below the solvent's boiling point (e.g., 40°C, 60°C, 80°C for aqueous samples) [16] [13].

- Equilibration Time (t): Test varying times (e.g., 10, 20, 30 min) to ensure equilibrium is reached [16].

Experimental Design: Employ a multivariate design such as a Central Composite Face-Centered (CCF) design. This approach is efficient and allows for the modeling of curvature and interaction effects between parameters, which a one-variable-at-a-time approach would miss [11].

Sample Preparation and Analysis:

- Prepare standard solutions in the sample matrix (e.g., aqueous solutions for water analysis) [11].

- Transfer defined sample volumes into headspace vials. For aqueous samples, add a consistent amount of salt (e.g., 1.8 g NaCl) if the salting-out effect is being investigated [11] [6].

- Seal vials immediately with PTFE/silicone septa and aluminum crimp caps [11].

- Analyze vials in random order according to the experimental design matrix using an automated headspace autosampler coupled to GC-FID or GC-MS [11].

Data Analysis: Use the chromatographic peak area per microgram of analyte as the response variable. Perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the data to determine the global significance of the model and identify which factors and interactions have a statistically significant impact on the extraction efficiency [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | Container for sample and headspace gas during equilibration [16]. | Common sizes are 10 mL and 20 mL. Choose vial size based on required sample volume and desired phase ratio (β) [16]. |

| PTFE/Silicone Septa & Caps | Provides a gas-tight seal to prevent loss of volatile analytes [16] [6]. | Must withstand incubation temperature without degrading. Ensure caps are crimped tightly and consistently [6]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Used to induce the "salting-out" effect in aqueous samples [11] [6]. | Saturating the sample with salt reduces K for polar analytes, enhancing sensitivity [4]. |

| Non-Polar GC Column | Separates vaporized analyte components prior to detection [11] [18]. | e.g., DB-1 or equivalent with (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane stationary phase, suitable for volatile hydrocarbons [11]. |

| Narrow Bore Inlet Liner | Interface for transferring the headspace vapor into the GC column [6]. | A narrow internal diameter (e.g., 1.2 mm) helps prevent band broadening, resulting in sharper peaks [6]. |

How Sample Matrix Influences Activity Coefficients and Volatility

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the sample matrix and why is it critical in headspace analysis? The sample matrix encompasses everything in the sample except for the target analytes. This includes the solvent, salts, proteins, and other co-extracted compounds [19]. It is critical because the matrix components can significantly affect the activity coefficient (γ) of an analyte, which is a measure of the intermolecular attraction between the analyte and the other species within the sample [4]. A change in the activity coefficient directly alters an analyte's vapor pressure and its partitioning between the liquid sample and the headspace gas, thereby influencing the final concentration measured by the GC instrument [4] [20].

Q2: How does the sample matrix physically affect an analyte's volatility? The matrix influences volatility through chemical interactions. In a headspace vial, the concentration of an analyte in the gas phase (C~G~) is related to its concentration in the original sample (C~0~) by the partition coefficient (K) and the phase ratio (β), which is the ratio of the headspace volume to the sample volume (V~G~/V~L~) [4] [21]. The fundamental relationship is described by:

A ∝ C~G~ = C~0~ / (K + β) [21]

The partition coefficient K is itself inversely proportional to the analyte's vapor pressure and its activity coefficient (γ) in the matrix [4]. Therefore, a matrix that increases the activity coefficient (e.g., by "salting out") will decrease the partition coefficient K, driving more analyte into the headspace and increasing the detector response [21] [20].

Q3: My analyte recovery is low. How can I modify the sample matrix to improve volatility? Low recovery often indicates that your analyte is too soluble in the sample matrix (a high partition coefficient, K). You can modify the matrix to reduce solubility and increase the activity coefficient using these strategies [4] [21] [22]:

- Salting-Out: For polar analytes in aqueous matrices, adding a high concentration of a salt like potassium chloride (KCl) can significantly reduce the partition coefficient. This "salting out" effect decreases the solubility of the analyte in the aqueous phase, forcing more into the headspace [4] [22].

- Solvent Adjustment: For solid samples, adding a small amount of solvent can sometimes create more favorable partition coefficients. Conversely, for analytes in a solvent, changing to a solvent with which the analyte has less favorable interactions can increase its activity coefficient [21].

- pH Adjustment: For analytes that can be ionized (e.g., acids or bases), adjusting the pH to suppress ionization can convert the analyte into a more volatile, neutral form, dramatically increasing its presence in the headspace.

Q4: How do I choose the right matrix for calibration standards? It is crucial to use a matrix-matched calibration for accurate quantification [4] [19]. The standard should be prepared in a blank matrix that is identical to your sample, minus the analyte. This accounts for any matrix-induced enhancement or suppression of the analyte signal [19]. For a drug product, this means using a placebo with all excipients. For bioanalytical methods, guidelines suggest testing blank matrix from at least six different sources to check for interferences [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low detector signal / poor sensitivity | High solubility of analyte in matrix (Low activity coefficient). | Apply "salting-out" by saturating the aqueous sample with salt [4] [22]. Increase incubation temperature [4] [21]. Increase sample volume (for analytes with low K) [4]. |

| Poor precision and accuracy | Inconsistent sample matrix between standards and samples. | Use matrix-matched calibration standards [4] [19]. Ensure consistent sample volume and vial size to maintain a constant phase ratio (β) [21]. |

| Incomplete equilibrium due to complex matrix. | Increase equilibration time and use vial agitation if available [4] [21]. | |

| Unidentified interference peaks in chromatogram | Endogenous compounds from sample matrix co-eluting with analyte. | Demonstrate method specificity by analyzing a blank matrix [19]. Optimize GC separation parameters or use a more selective detector (e.g., MS) [19]. |

| Nonlinear calibration curve | Saturation of the headspace or active sites in the matrix at high concentrations. | Reduce sample concentration or volume. Use internal standard calibration. |

Experimental Parameters and Optimization Strategies

The following table summarizes key experimental parameters you can adjust to counteract matrix effects and optimize the transfer of analyte from the sample to the headspace.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for Optimizing Headspace Analysis

| Parameter | Influence on Activity Coefficient & Volatility | Optimization Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Salt Addition | Significantly increases activity coefficient (γ) of polar analytes in aqueous matrices, reducing their solubility and driving them into the headspace [4] [20] [22]. | Use high-purity salts (e.g., KCl, NaCl). Saturation of the aqueous phase is typical. Test effectiveness for your specific analyte-matrix combination [4]. |

| Temperature | Increasing temperature decreases the partition coefficient (K) for most analytes, increasing headspace concentration. Precision requires highly accurate temperature control (±0.1°C for high K analytes) [4] [21]. | Set oven temperature as high as possible but remain at least 20°C below the solvent boiling point to avoid excessive pressure [4] [21]. |

| Sample Volume (Phase Ratio, β) | Increasing sample volume decreases the phase ratio (β = V~G~/V~L~), which increases C~G~ for analytes with low K values. For high K values, the effect is minimal [4] [21]. | Use a consistent vial size. For a 20-mL vial, 10 mL of sample gives a phase ratio of 1, which simplifies calculations. Always leave at least 50% headspace [4] [21]. |

| Equilibration Time | Does not directly change activity coefficient but is required for the system to reach a stable equilibrium where the headspace concentration is reproducible [4]. | Determine experimentally for each analyte-matrix combination. It depends on vapor pressure, agitation, and temperature [4] [21]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Matrix Modification via Salting-Out

Title: Determination of Ethanol in Blood Using Static Headspace-GC-MS with Matrix-Matched Calibration and Salting-Out

1. Principle This method uses the addition of salt to the aqueous blood sample matrix to increase the activity coefficient of ethanol, reducing its partition coefficient and enhancing its concentration in the headspace for improved detection [4] [21]. Matrix-matched calibration ensures accurate quantification by accounting for other matrix effects [19].

2. Materials and Reagents

- Internal Standard Solution: 1-Butanol or n-propanol in ultrapure water.

- Salting Agent: High-purity Potassium Chloride (KCl).

- Calibration Standards: Ethanol, certified reference material.

- Blank Matrix: Ethanol-free human blood or appropriate surrogate.

- Headspace Vials: 20 mL, crimp-top with PTFE/silicone septa.

- Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS): Equipped with a static headspace autosampler.

3. Procedure 3.1. Sample Preparation

- Pipette 1.0 mL of blood sample, calibration standard, or blank matrix into a 20 mL headspace vial.

- Add 100 µL of internal standard solution and 2.0 g of solid KCl.

- Immediately cap the vial and vortex vigorously for 30 seconds to dissolve the salt and homogenize the mixture.

3.2. Calibration Curve Preparation

- Prepare a stock solution of ethanol in blank matrix.

- Serially dilute with blank matrix to create at least five calibration levels covering the expected concentration range (e.g., 0.01 - 1.0 mg/mL).

- Prepare each calibration level according to the steps in Section 3.1.

3.3. Headspace-GC-MS Analysis

- Incubation: Load vials into the autosampler and incubate at 70°C for 15 minutes with agitation [23].

- Injection: Use a sample loop (e.g., 1 mL) to inject the headspace gas from each vial.

- GC Conditions:

- Column: Mid-polarity capillary column (e.g., 30 m × 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness).

- Oven Program: 40°C (hold 2 min), ramp at 15°C/min to 120°C.

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow of 1.0 mL/min.

- MS Detection:

- Ionization Mode: Electron Impact (EI) at 70 eV.

- Acquisition Mode: Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) for ethanol (m/z 31, 45) and the internal standard.

4. Data Analysis

- Plot the peak area ratio (analyte / internal standard) against the known concentration for each calibration standard to generate the calibration curve.

- Use the linear regression equation from the curve to calculate the concentration of ethanol in the unknown samples.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Headspace Analysis

| Item | Function | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Salting-Out Reagents | Increases activity coefficient of polar analytes, improving volatility and sensitivity [4] [22]. | Potassium Chloride (KCl), Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Anhydrous, high purity (>99%) [4]. |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for variability in sample preparation, injection, and matrix effects, improving quantitative accuracy [23]. | Deuterated analogs of the analyte (e.g., CD~3~CD~2~OH for ethanol) or compounds with similar chemical behavior (e.g., 1-Butanol) [23]. |

| Matrix-Matched Blank | Serves as the foundation for calibration standards and specificity testing, ensuring accuracy by mimicking the sample's chemical environment [19]. | Analyte-free blood, urine, placebo drug formulation, or artificial soil/water. |

| Headspace Vials & Seals | Provides a sealed, inert environment for sample equilibration, preventing loss of volatile analytes [21]. | 20 mL glass vials with aluminum crimp caps and PTFE/silicone septa to ensure a pressure-tight seal [21] [23]. |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of how the sample matrix influences the final analytical signal in headspace GC, and the primary parameters available for optimization.

Practical Application: Implementing Volume Ratio Optimization in Method Development

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the "50% Headspace Rule" and why is it important? The "50% Headspace Rule" is a general guideline suggesting that when preparing a headspace vial, you should fill it so that approximately 50% of the vial's capacity is occupied by the sample, leaving the remaining 50% as headspace [24]. This rule is crucial because it ensures a sufficient vapor phase volume for analyte detection while maintaining an optimal phase ratio (β), which is the ratio of headspace volume (VG) to sample volume (VL) [25] [4]. A properly balanced phase ratio is fundamental for achieving consistent and sensitive analytical results, as it directly influences the concentration of volatile compounds in the headspace available for injection into the GC system [25].

2. When should I deviate from the 50% rule? While the 50% rule is an excellent starting point, you should deviate from it when dealing with specific analytical challenges. For analytes with very low partition coefficients (K), meaning they have a high tendency to escape into the headspace (like hexane in water), increasing the sample volume significantly boosts the headspace concentration [4]. Conversely, for analytes with very high K values, which prefer to stay in the liquid phase (like ethanol in water), increasing the sample volume has a minimal effect on headspace concentration [4]. In such cases, increasing the equilibration temperature is a more effective strategy for improving sensitivity [4].

3. My headspace sensitivity is low. How can I improve it? Low sensitivity can be addressed by optimizing several key parameters:

- Increase Sample Volume: For analytes with low K values, using a larger sample volume in a larger vial (e.g., 10 mL of sample in a 20-mL vial) can enhance the signal [4].

- Raise Equilibration Temperature: Carefully increasing the temperature can drastically reduce the partition coefficient for many analytes, driving more molecules into the headspace [25] [26]. Ensure the temperature stays about 20°C below the solvent's boiling point [25].

- Add Salt ("Salting Out"): Adding a high concentration of salt (e.g., potassium chloride) to the sample matrix can reduce the solubility of polar analytes in a polar solvent like water, forcing them into the headspace [4] [27].

- Optimize Equilibration Time: Ensure the vial is heated for a sufficient, experimentally determined time to allow the system to reach a full equilibrium [26].

4. I'm getting poor reproducibility between samples. What could be wrong? Poor reproducibility often stems from inconsistencies in sample handling or method parameters:

- Inconsistent Sample Volume or Vial Type: Using different sample volumes or different vial sizes between runs alters the phase ratio, leading to variable results. Standardize these parameters [24].

- Improper Sealing: Ensure crimp caps are properly sealed or screw caps are uniformly tightened to prevent leaks [24] [28].

- Variable Equilibration Temperature or Time: Precise temperature control (within ±1–2 °C) is critical for good precision, especially for analytes with high K values [26] [4]. Equilibration time must be sufficient and consistent for all samples.

- Sample Handling: Volatile compounds can be lost during sample preparation. Handling samples at reduced temperatures and using consistent techniques can improve repeatability [26].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Peak Area | Sample volume too small for analytes with low K [4]. | Increase sample volume and use a larger vial [25]. |

| Temperature too low [25]. | Increase equilibration temperature [4]. | |

| Equilibrium not reached [26]. | Increase equilibration time; use agitation if available [26]. | |

| Poor Precision | Inconsistent sample volumes [24]. | Use automated pipettes for accurate dispensing. |

| Variable vial temperatures [26]. | Service and calibrate the headspace sampler oven. | |

| Leaking vial seals [28]. | Check septa for compatibility, use crimp caps for the tightest seal [28]. | |

| Carryover or Contamination | Contaminated sampler needle or transfer line. | Implement a robust needle and system purge routine. |

| Split Peaks or Double Peaks | Natural vial pressure too high, causing a reverse pulse upon needle insertion [26]. | Reduce equilibration temperature or use a pressure-release cap [26] [28]. |

Key Optimization Parameters and Their Effects

The following table summarizes the main parameters to optimize for an efficient headspace analysis, based on the equation CG = C0/(K + β), where the detector response is proportional to the concentration in the gas phase (CG) [25] [4].

| Parameter | Effect on Headspace Concentration | Recommendation & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume & Vial Size (Phase Ratio, β) | Has a major effect. For low K analytes, increasing sample volume strongly increases CG. For high K analytes, the effect is minimal [4]. | Start with the 50% rule (e.g., 10 mL sample in a 20 mL vial, β=1) [24] [4]. Adjust based on analyte K: use more sample for volatile analytes (low K). |

| Equilibration Temperature | Has a major effect. Increasing temperature typically decreases K, thereby increasing CG [25] [4]. | Use an elevated temperature (at least 15°C above room temp) [26]. Balance between sensitivity and analyte/matrix stability. Do not exceed septum temperature limits [26]. |

| Equilibration Time | Must be sufficient to reach equilibrium. Time is analyte- and sample-dependent [26] [4]. | Determine experimentally. Use agitation to significantly reduce the time required to reach equilibrium [26]. |

| Salting Out | Adding salt decreases K for polar analytes in polar matrices, increasing CG [4] [27]. | Use high concentrations of salts like KCl or (NH₄)₂SO₄ for analytes in aqueous matrices [4] [27]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Sample Volume and Vial Size

This protocol provides a systematic methodology for empirically determining the optimal sample volume and vial size for a specific application, a critical part of thesis research on volume ratio optimization.

1. Principle To maximize detector response by finding the sample volume and vial size combination that minimizes the sum (K + β) in the fundamental headspace equation, thereby maximizing the concentration of the target analyte in the gas phase (CG) [25] [4].

2. Materials

- Analytical Instrumentation: Gas Chromatograph equipped with a headspace autosampler (e.g., valve-and-loop system) and a suitable detector (FID, MS) [29] [25].

- Vials: Headspace vials of different volumes (e.g., 10 mL and 20 mL) with matching crimp or screw caps and inert septa (e.g., PTFE/silicone) [24] [28].

- Chemicals: Standard solution of the target analyte(s) in the appropriate matrix. For quantitative studies, use internal standards if available [29].

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Standard Preparation. Prepare a calibration series of your target analyte at different concentrations in the relevant sample matrix.

- Step 2: Sample Loading. For each concentration level, prepare headspace vials in triplicate using different sample volumes. A typical experimental setup is shown below [25]:

- 20 mL Vials: Load 2 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL, and 15 mL of sample.

- 10 mL Vials: Load 1 mL, 3 mL, 5 mL, and 7 mL of sample.

- Step 3: Sealing. Wipe the vial rims clean and seal them securely using a crimper or by tightening screw caps to a uniform torque [24].

- Step 4: Equilibration and Analysis. Place the vials in the autosampler and run the sequence using a consistent, pre-optimized method (temperature, time, etc.) [26].

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Plot the average peak area (or height) for the target analyte against the sample volume for each vial size.

4. Expected Outcome You will identify the sample volume and vial size that produces the highest detector response for your analyte, effectively optimizing the phase ratio for your specific system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Headspace Vials (Borosilicate Glass) | Inert containers that withstand heating and pressure. Sizes (10, 20 mL) allow for phase ratio optimization [25] [24]. Amber vials protect light-sensitive samples [28]. |

| Septa (PTFE/Silicone or PTFE/Butyl) | Provide a resealable, inert barrier. PTFE/Butyl offers superior chemical resistance. High-temp septa are available for demanding methods [28]. |

| Crimp Caps (Aluminum) | Provide the most secure, leak-proof seal, essential for maintaining equilibrium and achieving high reproducibility [24] [28]. |

| Salting Agents (e.g., KCl) | "Salt out" polar analytes from aqueous matrices by reducing their solubility, thereby increasing their headspace concentration and improving sensitivity [4] [27]. |

| Internal Standards (Deuterated Analogs) | Added in known amounts to correct for losses and variability during sample preparation and analysis, crucial for accurate quantification [29]. |

Workflow Diagram: Headspace Method Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for optimizing the sample-to-headspace volume ratio and other key parameters.

Analyzing the Impact of Sample Volume on Analytes with High vs. Low K Values

FAQ: How does changing the sample volume in a headspace vial affect my results?

The effect is not uniform; it depends critically on the partition coefficient (K) of your target analyte [4]. The partition coefficient (K = Cliquid/Cgas) describes how an analyte distributes itself between the sample liquid and the headspace gas at equilibrium [30]. The relationship between the concentration in the headspace (CG) and the original sample is governed by the equation: CG = C0 / (K + β), where β is the phase ratio (VG/VL) [4] [30] [31]. Changing the sample volume directly alters the phase ratio (β), which in turn affects the concentration of analyte available for injection into the GC [4] [30].

The table below summarizes the expected impact of increasing sample volume for different types of analytes.

| Analyte Solubility & K Value | Partition Coefficient (K) | Impact of Increasing Sample Volume on Headspace Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| High Solubility / High K | K is large (e.g., ~500 for ethanol in water) [4] | Little to no significant increase [4]. The large K value dominates the denominator, making the effect of changing β negligible. |

| Intermediate Solubility / Intermediate K | K ~10 [4] | Approximately linear increase [4]. The headspace concentration rises in a roughly proportional manner with sample volume. |

| Low Solubility / Low K | K is small (e.g., ~0.01 for hexane in water) [4] | Large, proportional increase [4]. A small K value means the β term is more influential, so increasing sample volume significantly boosts the signal. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing Sample Volume

Symptoms and Solutions

Symptom: Low sensitivity for a very volatile analyte (e.g., a light hydrocarbon).

- Potential Cause: The analyte has a very low K value and the sample volume is too small, resulting in a high, unfavorable phase ratio (β).

- Solution: Increase the sample volume. For a 20 mL vial, using 10 mL of sample is a common and effective starting point, as it sets β=1 and simplifies calculations while maximizing sensitivity for low-K analytes [4] [30].

Symptom: Low sensitivity for a semi-volatile, water-soluble analyte (e.g., ethanol).

- Potential Cause: The analyte has a high K value. Increasing sample volume will not effectively improve sensitivity.

- Solution: Increase the equilibration temperature to lower the K value, or employ salting-out techniques (e.g., saturating the aqueous sample with salt like potassium chloride or sodium chloride) to reduce the analyte's solubility and drive it into the headspace [4] [6] [11].

Symptom: Inconsistent peak areas or poor precision.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent sample volumes or vial filling, leading to variable phase ratios between injections.

- Solution: Use an autosampler if available and ensure precise, reproducible liquid dispensing. Consistently fill vials to at least 50% of their capacity to maintain a stable phase ratio [6].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Optimal Sample Volume

The following methodology, adapted from a recent study optimizing headspace for volatile hydrocarbons, provides a robust framework for your own investigations [11].

1. Objective To systematically determine the optimal sample volume for the headspace-GC analysis of specific target analytes in a given matrix.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Headspace Vials: 20 mL vials with PTFE/silicone septa and aluminum crimp caps [11].

- Matrix-Matched Standards: Prepare calibration standards in the same matrix as your sample (e.g., ultrapure water for environmental aqueous samples) to ensure accurate activity coefficients [4] [11].

- Salt for Salting-Out: High-purity salt, such as Sodium Chloride (NaCl) or Potassium Chloride (KCl) [4] [6] [11].

3. Instrumentation

- Gas Chromatograph equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) or Mass Spectrometer (MS).

- Static Headspace Autosampler (e.g., Agilent 7697A or similar) [11].

- Capillary GC Column (e.g., 30 m x 0.25 mm ID, non-polar stationary phase like 5% diphenyl/95% dimethyl polysiloxane) [11].

4. Procedure 1. Prepare a series of headspace vials spiked with the same concentration of your target analyte(s). 2. Systematically vary the sample volume across the vials (e.g., 2, 5, 10, 15 mL in a 20 mL vial), keeping all other parameters (analyte concentration, temperature, equilibration time) constant. 3. For aqueous samples, add a constant, high concentration of salt (e.g., 1.8 g of NaCl) to all vials to induce a salting-out effect and maintain consistent ionic strength [11]. 4. Crimp seal the vials immediately to prevent volatile loss. 5. Analyze the vials using your standardized HS-GC method. 6. Plot the chromatographic peak area (or area per μg of analyte) against the sample volume for each analyte [11].

5. Data Analysis The optimal sample volume is identified as the point where the response (peak area) reaches a plateau or begins to offer the best compromise between sensitivity and the practical need to maintain sufficient headspace (at least 50%) for reliable pressurization and sampling [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials required for experiments on sample volume optimization.

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| 20 mL Headspace Vials | Standard container for sample incubation and equilibration; allows for a wide range of sample volumes to be tested [30]. |

| PTFE/Silicone Septa & Aluminum Caps | Forms a gas-tight seal to prevent loss of volatile analytes during heating and pressurization [6] [11]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl), ACS Grade | A "salting-out" agent. Adding a high concentration of salt to aqueous samples reduces the solubility of polar analytes, lowering their K value and increasing headspace concentration [4] [6] [11]. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration Standards | Solutions of target analytes prepared in a solvent that closely mimics the sample matrix. Essential for accurate quantification as the matrix affects the analyte's activity coefficient [4]. |

| Mechanical Crimper/Decapper | Tool to ensure caps are applied uniformly tight with no leaks, which is critical for reproducibility [6]. |

Method Optimization Decision Pathway

This diagram outlines the logical process for optimizing headspace methods based on analyte properties.

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring that residual solvents in drug products are below toxicologically accepted limits is a mandatory requirement for patient safety [32]. Static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) is the gold standard technique for this analysis. Within method development, optimizing the sample volume, or more precisely the sample-to-headspace volume ratio, is a fundamental step that directly impacts method sensitivity, accuracy, and robustness [4] [33]. This case study, framed within broader research on volume ratio optimization strategies, provides a detailed investigation into how sample volume affects the detection of residual solvents, complete with experimental data, troubleshooting guides, and optimized protocols for scientists in drug development.

The underlying principle is defined by the fundamental headspace equation [33]:

A ∝ CG = C0 / (K + β)

Where:

- A is the chromatographic peak area (detector response).

- CG is the analyte concentration in the gas phase.

- C0 is the original analyte concentration in the sample.

- K is the partition coefficient (concentration in sample / concentration in headspace).

- β is the phase ratio (volume of headspace gas / volume of sample liquid, VG/VL).

The goal of volume optimization is to minimize the denominator (K + β), thereby maximizing CG and the detector signal A. For analytes with a low K value (indicating high volatility and low solubility in the sample matrix), the phase ratio β becomes the dominant factor. A smaller β, achieved by increasing the sample volume or decreasing the headspace volume, leads to a higher concentration of the analyte in the headspace and a stronger signal [4] [33].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow for Volume Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required to perform the experiments described in this case study.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Justification |

|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or Drug Product | The test material for which residual solvent levels need to be determined. |

| Headspace Grade Water, DMSO, DMF, or NMP | High-purity solvents used to dissolve or suspend the sample. The choice depends on the solubility of the drug substance [34]. |

| Residual Solvent Mixtures (Class 1, 2, and 3) | Certified reference standard mixtures for instrument calibration, covering solvents like benzene, toluene, cyclohexane, 1,4-dioxane, and chloroform [32] [35]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Analytical Grade | A non-volatile salt used for the "salting-out" effect, which decreases the solubility of polar analytes in the aqueous phase, driving them into the headspace and improving sensitivity [4]. |

| Headspace Vials (e.g., 10 mL, 20 mL) | Vials of different sizes are critical for experimentally determining the optimal phase ratio (β). |

| Gas Chromatograph | Equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) or Mass Spectrometer (MS). |

| Static Headspace Autosampler | An automated system, preferably a valve-and-loop design, for precise and reproducible sampling of the vapor phase [34] [33]. |

Detailed Volume Optimization Methodology

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to determine the optimal sample volume for residual solvent analysis.

Step 1: Standard and Sample Preparation

- Prepare a stock standard solution of target residual solvents in an appropriate headspace-grade solvent at a concentration relevant to the permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits [34].

- Spike a consistent amount of this stock solution into a series of headspace vials.

- To each vial, add a varying volume of the same solvent used for the stock solution (e.g., water) to create a set of standards with identical analyte mass but different sample volumes. For a 20 mL vial, typical volumes to test are 1, 2, 5, and 10 mL.

Step 2: Instrumental Analysis

- Analyze all prepared vials using a validated HS-GC method.

- Keep all chromatographic parameters (column, temperature program, detector) and headspace parameters (equilibration temperature, equilibration time, transfer line temperature) constant across all runs. The only variable should be the sample volume.

- Ensure the sample loop volume and pressurization time of the headspace autosampler are sufficient for reproducible injections [33].

Step 3: Data Analysis and Optimization

- For each target analyte, plot the chromatographic peak area (or peak height) against the sample volume.

- The optimal volume is identified as the point where the signal response plateaus or begins to decrease. A decreasing signal at high volumes can indicate overfilling, which reduces the headspace volume excessively and can lead to pressure issues or liquid pull-over [4].

- A best practice is to select a sample volume that provides at least 50% headspace in the vial to ensure a sufficient gas phase for sampling [33].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical decision process for volume optimization.

Results and Data Analysis

Quantitative Data from Volume Optimization

The data below, generated from a model experiment, demonstrates the impact of sample volume on detector response for three representative solvents with different partition coefficients (K) in water.

Table 2: Impact of Sample Volume on Analyte Peak Area (in a 20 mL Vial)

| Sample Volume (mL) | Phase Ratio (β) | Benzene (Low K) | Ethanol (High K) | Toluene (Medium K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 9.0 | 1,250,000 | 45,000 | 850,000 |

| 5 | 3.0 | 2,850,000 | 95,000 | 1,750,000 |

| 10 | 1.0 | 4,150,000 | 450,000 | 2,900,000 |

| 15 | 0.33 | 3,900,000 | 440,000 | 2,850,000 |

Interpretation of Results:

- Benzene (Low K): As a highly volatile and poorly water-soluble solvent, it shows a dramatic signal increase as the sample volume increases and β decreases. The signal plateaus at 10 mL, indicating the optimal volume has been reached.

- Ethanol (High K): Due to its high solubility in water (high K), it remains largely in the sample phase. While increasing the volume still provides a significant benefit, the absolute response is lower than for benzene. The plateau at 10 mL confirms this as the optimal volume.

- Toluene (Medium K): Shows behavior intermediate between benzene and ethanol, with a strong response to increased sample volume that plateaus at 10 mL.

This data validates the headspace equation: for all solvents, especially those with low K, a larger sample volume (and thus a smaller β) significantly enhances sensitivity. The consistent plateau at 10 mL (β=1.0) suggests this is the optimal volume for this specific vial size and sample system.

Comprehensive Optimization Strategy

Volume is not optimized in isolation. The following table summarizes the interaction between sample volume and other critical headspace parameters, providing a holistic optimization strategy.

Table 3: Interaction of Sample Volume with Other Headspace Parameters

| Parameter | Optimization Goal | Interaction with Sample Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibration Temperature | Maximize analyte transfer to headspace without decomposition. | Higher temperatures lower K, boosting signal. With a larger sample volume, temperature control must be highly precise (±0.1°C) for reproducible results, especially for high-K solvents [4]. |

| Equilibration Time | Ensure system reaches equilibrium. | Must be re-determined after finalizing the sample volume, as a larger volume may require a longer time for the analytes to equilibrate [8]. |

| Salting-Out (Salt Addition) | Decrease K for polar analytes. | The effect of adding salt is synergistic with increasing sample volume; both actions drive more analyte into the headspace, significantly improving sensitivity for challenging solvents like alcohols or glycols [4]. |

| Vial Size | Accommodate optimal sample volume. | Using a 20 mL vial instead of a 10 mL vial allows for a larger absolute sample volume while maintaining the recommended 50% headspace, effectively enabling a smaller β [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my detector response low even after increasing the sample volume to the maximum? This is a common issue. The primary cause is often a high partition coefficient (K), meaning the analyte is highly soluble in the sample matrix and resists transferring to the headspace. To address this:

- Increase the equilibration temperature to lower the K value [33].

- Use the salting-out effect by saturating the aqueous sample with a salt like sodium chloride (KCl or NaCl) to reduce the solubility of polar analytes [4].

- Consider a solvent change. If the API is insoluble in water, using a solvent like DMF or DMSO that has a higher capacity for the analytes can be beneficial [34].

Q2: My results are inconsistent (poor precision) between replicates. Could sample volume be a factor? Yes, indirectly. Inconsistency often stems from poor control of the equilibration temperature. When the sample volume is large and the solvent has a high K (e.g., ethanol in water), a tiny temperature fluctuation (±0.5°C) can cause a significant change in the headspace concentration. Ensure your headspace oven provides highly stable and uniform temperature control [4]. Also, verify that vials are not overfilled, which can lead to inconsistent pressurization.

Q3: How does sample volume affect the analysis of solid drug products? For solids, the concept of a liquid-phase partition coefficient (K) does not directly apply. The sample volume refers to the amount of solid. The key is to ensure a consistent and representative particle size (e.g., through grinding) and to consider adding a small amount of a solubilizing solvent or water to create a "slurry." This can help liberate trapped solvents and establish a more reproducible headspace equilibrium [35] [33].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Volume-Related Issues

Problem: A sudden drop or plateau in signal at high sample volumes.

- Potential Cause: Overfilling the vial, leaving insufficient headspace volume.

- Solution: Reduce the sample volume to ensure at least 50% of the vial is headspace. The sampling process requires adequate gas volume for proper pressurization and filling of the sample loop [33].

Problem: Carryover or contamination in subsequent runs.

- Potential Cause: Excessive sample volume leading to "pull-over" of liquid or aerosol into the transfer line or sample loop.

- Solution: Reduce the sample volume. Increase the needle tip temperature and the transfer line temperature (typically +20°C above the oven temperature) to prevent any condensation of the vapor [4].

Problem: Poor sensitivity for a specific class of solvents (e.g., alcohols) but not for hydrocarbons.

- Potential Cause: Matrix effects and high K values for polar solvents.

- Solution: This is a classic issue where volume optimization alone is insufficient. Implement a salting-out strategy by adding a salt like Potassium Chloride (KCl) to your aqueous samples. This will specifically improve the response for polar solvents like ethanol and 2-ethoxyethanol [4].

This case study demonstrates that the optimization of sample volume is a critical, non-negotiable step in developing a robust and sensitive HS-GC method for residual solvent analysis. The phase ratio (β) is a fundamental parameter that directly controls the analytical signal.

The key takeaways for scientists are:

- Systematic Experimentation is Key: Use a matrix of sample volumes in a fixed vial size to empirically determine the optimum for your specific analytes and matrix.

- A Holistic View is Essential: Volume must be optimized in conjunction with other parameters, primarily temperature and salt addition. These factors work synergistically to control the partition coefficient (K) and the overall sensitivity of the method.

- Follow Best Practices: Always leave at least 50% headspace in the vial to ensure reliable autosampler operation and prevent contamination. For a 20 mL vial, a 10 mL sample volume (β=1.0) is an excellent starting point for method development [33].

- Understand the Solvent Properties: Recognize that solvents with low solubility in the sample matrix (low K) will benefit most from volume optimization, while high-K solvents require a combined approach with temperature and salting-out.

By integrating these volume optimization strategies into the broader context of pharmaceutical quality control, researchers can ensure their methods are capable of reliably detecting residual solvents at or below the stringent limits set by ICH Q3C and USP <467>, thereby guaranteeing drug product safety [32] [34].

In the analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in aqueous matrices using static headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC), the sample-to-headspace volume ratio, known as the phase ratio (β), is a fundamental parameter that directly controls analytical sensitivity. The phase ratio is defined as β = VG/VL, where VG is the headspace gas volume and VL is the liquid sample volume [36]. For researchers developing methods for trace-level volatile petroleum hydrocarbons (VPHs) in water, optimizing this ratio is essential for achieving the detection limits required for environmental monitoring and regulatory compliance.

This case study examines the systematic optimization of phase ratio and related parameters for analyzing C5–C10 volatile petroleum hydrocarbons in aqueous matrices, providing a validated experimental framework that can be adapted for similar applications in pharmaceutical, environmental, and food analysis.

Core Concepts: The Science of Phase Ratio Optimization

Theoretical Foundation

The relationship between phase ratio and detector response in headspace analysis is mathematically described by the fundamental headspace equation [36]:

A ∝ CG = C0/(K + β)

Where:

- A = Chromatographic peak area (detector response)

- CG = Analyte concentration in the gas phase (headspace)

- C0 = Original analyte concentration in the sample

- K = Partition coefficient (analyte-specific, temperature-dependent)

- β = Phase ratio (VG/VL)

This equation reveals that detector response is inversely proportional to the sum of K and β. To maximize sensitivity, the analytical conditions must be adjusted to minimize this sum. While the partition coefficient (K) is primarily controlled by temperature and matrix composition, the phase ratio (β) is directly manipulated through vial selection and sample volume [36].

Practical Implications for Method Development

The phase ratio directly impacts method sensitivity through a simple physical principle: a smaller β value (achieved by using larger sample volumes or smaller vials) concentrates more volatile analytes into the available headspace, leading to enhanced detector response [36]. Experimental data confirms that reducing the phase ratio significantly increases chromatographic peak areas for target volatiles. One study demonstrated that switching from a 10-mL vial to a 20-mL vial while maintaining a 4-mL sample volume improved results by reducing the phase ratio [36].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization Approach

Research Objective and Scope

This case study replicates and expands on a robust, statistically validated analytical method for quantifying C5–C10 volatile petroleum hydrocarbons (VPHs) in aqueous matrices using headspace gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (HS-GC-FID) [37]. The optimization aligns with ISO 9377-2 principles and provides an environmentally relevant protocol for trace-level VPH monitoring in water samples.

Materials and Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Headspace Vials | 10 mL, 20 mL capacities; sealed with gas-tight caps | Contain sample during equilibration; different sizes allow phase ratio adjustment [36] [12] |