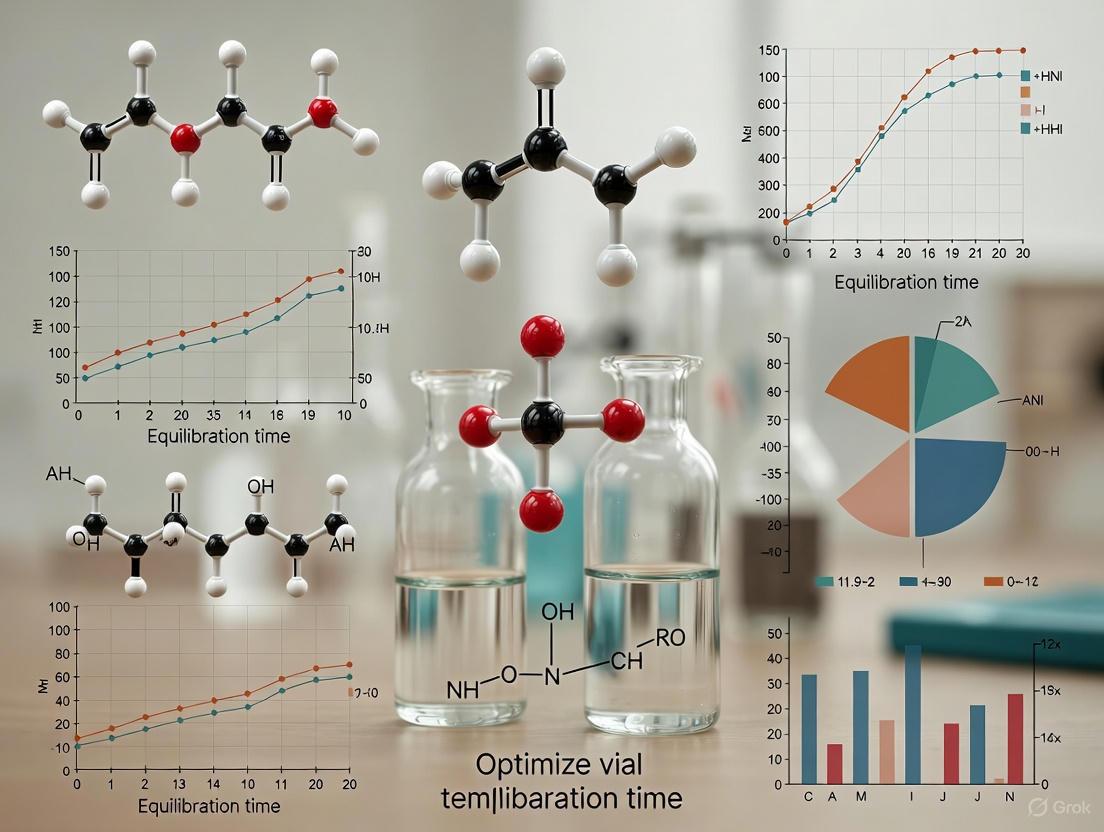

Optimizing Vial Temperature and Equilibration Time: A Scientist's Guide for Robust Results in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the critical parameters of vial temperature and equilibration time.

Optimizing Vial Temperature and Equilibration Time: A Scientist's Guide for Robust Results in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the critical parameters of vial temperature and equilibration time. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it explores the scientific impact of these parameters on analytical precision and process efficiency in applications ranging from chromatography to freeze-drying. The content delivers actionable methodologies for method development, systematic troubleshooting for common issues like ghost peaks and retention time shifts, and strategies for leveraging modern Process Analytical Technology (PAT) and data-driven modeling to ensure robust, transferable, and scalable processes.

The Science of Stability: Why Vial Temperature and Equilibration Time Are Fundamental to Data Integrity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I determine the correct incubation temperature and time for my headspace method? The optimal incubation temperature is a balance between maximizing the release of volatiles and avoiding sample degradation. A good starting point is to set the oven temperature to 20 °C below the boiling point of your sample matrix solvent [1]. The precise combination of temperature and equilibration time should be determined experimentally, as these parameters are application-dependent and can interact [2] [1]. Using an experimental design (DoE) approach is efficient for finding this optimum, as it can model these interaction effects [2].

Q2: My analysis shows poor reproducibility. Could the vial seal be the cause? Yes, an inconsistent seal is a common cause of poor reproducibility. Ensure the vial caps are crimped tightly with no leaks, but avoid deforming them [1]. Use a calibrated crimper and be consistent with the crimping force. For methods requiring storage at ultra-low temperatures, confirm that your chosen vial-stopper combination is validated for such conditions, as material contraction can cause transient leaks [3].

Q3: What is the "salting-out" effect and when should I use it? The "salting-out" effect involves saturating an aqueous sample with salt (e.g., sodium chloride) to reduce the solubility of volatile organic compounds in the water, thereby increasing their concentration in the headspace [1]. This is particularly useful for enhancing the sensitivity of analytes that are highly soluble in water [2]. Be aware that this can also drive unwanted compounds into the headspace, so its use is application-dependent [1].

Q4: How does vial headspace volume affect my analysis? For optimal equilibration, the headspace volume should be at least 50% of the total vial volume [1]. Furthermore, the overall sample volume has been identified as a critical parameter, with a strong negative impact on chromatographic response in some systems; larger sample volumes can reduce the peak area signal, and this factor can be more significant than temperature or time [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Signal for Volatile Analytes in Headspace-GC

Problem: Chromatographic peaks are smaller than expected, leading to poor detection sensitivity.

Investigation and Resolution:

- Check Incubation Temperature: The temperature may be too low. Increase the incubation temperature to shift the partition coefficient (K) of your analytes further into the headspace. Be mindful of the boiling points of your analytes and solvent to avoid degradation [1].

- Review Equilibration Time: The incubation time may be insufficient for the system to reach equilibrium. Methodically test longer equilibration times [2] [1].

- Evaluate Sample Volume: A sample volume that is too large can dilute the headspace concentration of the analyte. Experiment with reducing the sample volume, as this parameter can have a strong negative impact on the signal [2].

- Apply Salting-Out: For aqueous samples, add salt (e.g., sodium chloride) to induce the salting-out effect. In one study, the consistent addition of 1.8 g of NaCl improved partitioning and method reproducibility [2] [1].

- Verify Vial Seals: Ensure crimp caps are applied correctly and consistently to prevent volatile loss [1].

Issue: Container Closure Integrity Failure at Ultra-Low Temperatures

Problem: Drug products stored frozen at -80°C lose sterility due to loss of container closure integrity (CCI).

Investigation and Resolution:

- Confirm Capping Force: The residual seal force (RSF) is critical. One study demonstrated that a capping force of ≥ 27 N (6 lb) was required to maintain CCI at -80°C. Forces below this threshold resulted in leaks [3].

- Inspect Component Compatibility: Use a stack-up tolerance analysis to ensure the vial, stopper, and seal dimensions are compatible. Research shows that with the correct capping force, CCI can be maintained even with dimensional variations at the upper end of the ISO tolerance spec [3].

- Validate the Freezing Process: The cooling rate (e.g., during shipping on dry ice) can stress the seal. Testing under controlled and uncontrolled freezing conditions has shown that with a suitable vial-stopper-seal combination, CCI can be maintained despite thermal contraction [3].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Optimizing Headspace Parameters using a Central Composite Design

This methodology is adapted from a study optimizing the extraction of volatile petroleum hydrocarbons from water [2].

1. Objective To systematically optimize critical headspace parameters—sample volume (V), incubation temperature (T), and equilibration time (t)—for maximum chromatographic response.

2. Experimental Design

- Design Type: Central Composite Face-centered (CCF) Design.

- Factors: Three numeric factors (V, T, t).

- Response Variable: Chromatographic peak area per microgram of analyte (Area per μg).

3. Workflow The following diagram illustrates the iterative optimization process.

4. Key Materials

- GC System: Agilent 6890 GC with FID [2].

- Headspace Sampler: Static headspace sampler (e.g., Agilent G1888) [2].

- Column: DB-1 fused-silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 1.0 μm film thickness) [2].

- Vials: 20 mL headspace vials with PTFE/silicone septa and aluminum crimp caps [2].

5. Results and Interpretation Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to assess the global significance of the model. A successful model will have a high R² value and a statistically significant p-value (e.g., p < 0.0001). The analysis will reveal the significance of main effects, quadratic effects, and interaction effects between parameters [2].

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from the research.

| Parameter | Effect on Peak Area/µg | Significance & Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume (V) | Strong Negative Impact | The most significant factor in the cited study; larger volumes reduced response [2]. |

| Temperature (T) | Positive Impact | Increases volatility; exhibits positive interaction with time [2]. |

| Equilibration Time (t) | Positive Impact | Allows system to reach equilibrium; effect is synergistic with temperature [2]. |

| Statistical Model | R² = 88.86%, RMSE = 4.997, p < 0.0001 | Confirms model is highly significant and can reliably predict outcomes [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Induces "salting-out" effect in aqueous matrices to improve volatile partitioning into headspace [2] [1]. |

| DB-1 GC Column | A non-polar capillary column suitable for separating volatile hydrocarbon mixtures [2]. |

| PTFE/Silicone Septa | Provides a high-temperature, inert seal for headspace vials to prevent analyte loss and contamination [2]. |

| Helium Leak Detector | Gold-standard equipment for quantitatively assessing container closure integrity, especially under stress conditions [3]. |

| Narrow Bore Liner | GC inlet liner that minimizes band broadening for sharper peaks and improved signal in headspace analysis [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do I get inconsistent gas-liquid partitioning results for my semi-volatile organic compound (SVOC) between different experiment days?

Inconsistent partitioning results are often due to uncontrolled temperature fluctuations. Temperature directly influences a compound's vapor pressure, a key thermodynamic property governing its phase distribution. For instance, a study on atmospheric aerosols found that the partitioning of oxidation products from compounds like m-xylene and naphthalene is significantly enhanced at lower temperatures, which shift the equilibrium towards the condensed (liquid) phase [4]. Even small, unaccounted-for temperature variations in your lab or environmental chamber can alter the measured partitioning coefficient ((K_p)).

FAQ 2: How do I determine the optimal vial equilibration time for a temperature-dependent partitioning experiment?

The optimal equilibration time is not universal; it must be determined empirically for your specific system. It depends on the vial volume, the physicochemical properties of the compound (e.g., molecular weight, diffusivity), and the viscosity of the liquid phase. A general protocol is to conduct a time-series experiment: measure the concentration in one phase over time while holding temperature constant. The point at which the concentration stabilizes is the minimum equilibration time. Remember that at lower temperatures, equilibration may take longer due to reduced molecular motion, especially if the condensed phase becomes more viscous [4].

FAQ 3: My drug formulation requires ultra-low temperature storage (-80°C). How can I ensure the primary container remains intact and stable?

This is a critical consideration for advanced therapies. The integrity of the container at ultra-low temperatures must be verified. Recent studies on prefillable polymer syringes have confirmed their functionality and ability to maintain a sterile barrier at temperatures as low as -180°C [5]. When selecting a vial or syringe, you should review manufacturer data on low-temperature performance, including container closure integrity, leachables, and gliding force of the plunger at your intended storage temperature.

FAQ 4: Why does the pH sensitivity of my ionizable compound's partitioning change with temperature?

Temperature affects both the acid dissociation constant ((pK_a)) and the phase-specific activity coefficients of the ionized and neutral forms of a compound. Research on organic acids and bases in atmospheric aerosols shows that temperature dependence can vary widely between compounds [6] [7]. A change in temperature can alter the pH of the aqueous phase and the solubility of the neutral species. Therefore, the combined effect on the overall partition coefficient can be complex and non-linear, necessitating experimental investigation across your relevant temperature and pH ranges.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpectedly Low Partitioning into the Liquid Phase

- Potential Cause #1: Temperature is too high.

- Solution: Verify and recalibrate your temperature control system (e.g., water bath, incubator). For volatile and semi-volatile compounds, even a 5°C increase can significantly favor the gas phase. Consult literature or models like SIMPOL.1 to estimate the saturation concentration ((C^*)) at your experimental temperature [4].

- Potential Cause #2: The aqueous phase pH is suboptimal for an ionizable compound.

- Solution: For weak acids, lowering the pH will suppress dissociation and increase the fraction of the neutral, more volatile species, driving the compound toward the gas phase. For weak bases, the opposite is true. A study showed that as pH increases from 2 to 6, amines exhibit a significantly increased affinity for the gas phase [6]. Systematically profile partitioning across a pH range to find the optimum.

Problem: Poor Reproducibility of Partitioning Coefficients

- Potential Cause #1: Inadequate vial equilibration time.

- Solution: Perform the time-series experiment described in FAQ #2 to establish a validated, fixed equilibration time for your protocol. Ensure this time is strictly adhered to for all replicates.

- Potential Cause #2: Unaccounted for temperature gradients or drift.

- Solution: Use a calibrated, high-precision thermometer to map the temperature inside your incubator or heating block. Ensure vials are placed in a uniform temperature zone. For critical experiments, use a system with active mixing or agitation to ensure a homogeneous temperature throughout the vial.

Problem: Compound Degradation During Long Equilibration Times

- Potential Cause: Exposure to elevated temperatures or incompatible container surfaces.

- Solution: If a long equilibration time is unavoidable, you must confirm the chemical stability of your compound under those exact conditions. Run a stability study by storing the compound in the liquid phase at the experimental temperature and sampling over time to measure concentration and purity. Consider using inert container materials (e.g., glass with silanized coating) to minimize surface adsorption or catalytic degradation.

Quantitative Data on Temperature-Dependent Partitioning

The following table summarizes experimental data on how temperature influences the partitioning behavior of various compounds, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Experimentally Observed Temperature Effects on Gas-Liquid Partitioning

| Compound / System | Temperature Range Studied | Key Observation on Partitioning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| m-Xylene & Naphthalene Oxidation Products | Not specified (lower temps tested) | Lower temperatures significantly enhanced SOA (liquid phase) formation. The effective saturation concentration ((C_i^*)) values shifted towards lower values, indicating stronger partitioning to the particle phase [4]. | [4] |

| Organic Acids and Bases (24 compounds) | Varied | Temperature had a strong but compound-specific influence on partitioning. The analysis was limited by a lack of reliable enthalpy of phase change data for many species [6]. | [6] [7] |

| Lithium in Plagioclase-Rhyolitic Melt | 800°C - 875°C | The plagioclase-melt partition coefficient for Lithium ((K_{Li}^{plag/rhy})) increased with temperature at lower pressures (50-100 MPa), showing temperature dependence is also pressure-sensitive in geologic systems [8]. | [8] |

| Semi-volatile Inorganic Aerosols | Field observations | Warm, dry conditions suppressed aerosol liquid water and elevated H+, lowering pH and influencing the gas-particle partitioning of semi-volatile species like NH₃/NH₄⁺ [9]. | [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Enthalpy of Phase Transfer ((\Delta H_{partition}))

This protocol allows you to quantify the thermodynamic driving force behind temperature-dependent partitioning.

- Preparation: Prepare a standard solution of your analyte in a suitable solvent. Prepare the liquid phase (e.g., buffer at a defined pH) that will be placed in the vial.

- Experimental Setup: Use multiple vials with the same headspace-to-liquid volume ratio. Introduce the same amount of your analyte and liquid phase into each vial.

- Temperature Equilibration: Seal the vials and place them in different, precisely controlled temperature environments (e.g., 4°C, 15°C, 25°C, 37°C). Allow the vials to equilibrate for a pre-determined, sufficient time (see FAQ #2).

- Sampling and Analysis: After equilibration, carefully sample from either the gas phase (e.g., using a gas-tight syringe) or the liquid phase from each vial. Analyze the samples using a calibrated analytical method (e.g., GC-MS, HPLC).

- Data Calculation and Modeling:

- Calculate the partition coefficient, (Kp = C{liquid}/C{gas}), for each temperature.

- Use the van't Hoff equation to relate (Kp) to enthalpy: (\ln(Kp) = -\frac{\Delta H{partition}}{R} \cdot \frac{1}{T} + \text{constant})

- Plot (\ln(Kp)) against (1/T) (in Kelvin). The slope of the linear fit is (-\Delta H{partition}/R), from which you can calculate the enthalpy.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Vial Equilibration Time for a Given Temperature

This is a critical step to ensure your partitioning measurements are made at equilibrium.

- Setup: Prepare a large batch of identical vials containing your compound and liquid phase to ensure uniformity.

- Incubation: Place all vials in a temperature-controlled environment set to your desired experimental temperature.

- Time-Point Sampling: Remove vials from the incubator at a series of time points (e.g., 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 24h). Immediately after removal, sample the content and analyze the concentration in one phase.

- Analysis: Plot the measured concentration versus time. The equilibration time is the point after which no significant trend in concentration is observed. Use this time plus a safety margin for all future experiments at that temperature.

Experimental Workflow for Partitioning Studies

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for designing and troubleshooting a gas-liquid partitioning experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Partitioning Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prefillable Polymer Syringes | Primary container for sensitive formulations, especially for ultra-low temperature storage. | Select products verified for performance at your target temperature (e.g., -80°C to -180°C). Key parameters include container closure integrity, gliding force, and leachables [5]. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., Trehalose, Sucrose) | Stabilizers for lyophilized (freeze-dried) formulations. Protect biomolecules and viral vectors (e.g., AAV) during freezing and drying. | Used in lyophilization formulations for gene therapies to enable storage at 2-8°C by preventing aggregation and maintaining potency [10]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (Tristearin, Tripalmitin) | Can be used as tracer systems to monitor the maximum temperature exposure of nanoparticles during processing like spray drying [11]. | Exploits the monotropic polymorphism of triglycerides to indicate if a critical melting temperature was exceeded. |

| Classical Density Functional Theory (cDFT) | A computational modeling approach for predicting phase coexistence and partitioning in complex, multi-component systems [12]. | Useful for exploring the effect of size ratios and affinities between different materials (polymers, colloids) on their distribution between coexisting phases before wet-lab experiments. |

FAQs: Equilibration and Its Impact on Analytical Results

Q1: What is the direct link between improper equilibration and poor repeatability in analytical methods? Improper equilibration directly causes poor repeatability by creating inconsistent starting conditions for each analysis. In techniques like chromatography, failure to re-establish the initial mobile phase composition and stationary phase environment between runs leads to significant retention time shifts. For example, a reader reported a peptide's retention time shifting from 15 minutes in the first run to 5 minutes in subsequent runs due to inadequate re-equilibration, demonstrating severe run-to-run variability [13]. Similarly, in headspace gas chromatography (GC), inconsistent thermostat temperature or insufficient incubation time prevents reproducible gas-liquid phase equilibrium, causing large variability in peak areas for replicate injections [14].

Q2: How can improper equilibration reduce analytical sensitivity? Insufficient equilibration can lower sensitivity by causing system instability that manifests as high background noise or baseline drift, effectively masking the detection of low-concentration analytes. Furthermore, in headspace GC, vial leakage or suboptimal incubation temperature—both equilibration-related issues—can lead to a weak chromatographic signal intensity for volatile compounds [14]. Temperature mismatch during analysis, often stemming from improper eluent pre-heating, can also degrade sensitivity and peak shape [15].

Q3: What are the signs of poor column equilibration in Liquid Chromatography (LC)? The most common symptom is inconsistent retention times between the first injection and subsequent runs, especially after a gradient elution or a change in mobile phase [13]. Other signs include drifting baselines, changes in peak shape (such as peak splitting or fronting), and variations in peak area [15]. These issues occur because the stationary phase has not fully returned to its initial state, altering its interaction with analytes.

Q4: How much equilibration time is typically sufficient for a reversed-phase LC column? A good rule of thumb is to flush the column with 10-15 column volumes of the initial mobile phase composition. The column volume (VM) can be estimated using the formula: VM ≈ (0.5 x 10⁻³) * L * dc², where L is the column length (mm) and dc is the column diameter (mm) [13]. For instance, a 150 x 2.1 mm column has a volume of approximately 0.33 mL, requiring about 3.3 mL of mobile phase for equilibration. The required volume must also account for the system's dwell volume [13].

Q5: In techniques other than LC, what constitutes "equilibration" and how does its failure impact results? Equilibration is a fundamental concept in many analytical techniques:

- Headspace GC: Equilibration involves achieving a stable gas-liquid phase partition of volatiles at a controlled temperature. Failure causes poor repeatability and low sensitivity [14].

- Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying): Equilibration refers to achieving a uniform and stable product temperature below the critical collapse temperature. An uncontrolled freezing step leads to vial-to-vial variability in ice crystal size, which causes uneven drying rates and ultimately results in batch inconsistency with varying residual moisture and stability [16].

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Sedimentation Equilibrium (SE) requires achieving a thermodynamic balance between sedimentation and diffusion. This process is inherently slow, and improper handling of the approach to equilibrium can lead to inaccurate molar mass determinations [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Repeatability and Sensitivity

Common Symptoms, Causes, and Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large variability in peak area or retention time (Poor Repeatability) [14] [13] | Inconsistent thermal equilibration in headspace vials; Insufficient column re-equilibration time in LC. | Extend incubation/equilibration time; Standardize sample prep volume and temperature; Use 10-15 column volumes for LC re-equilibration [14] [13]. |

| Low peak area or reduced sensitivity [14] | Leakage from vials (loss of analyte); Suboptimal incubation temperature; Inconsistent injection volume. | Check system for leaks, especially around seals and needles; Optimize incubation temperature; Verify injection system consistency [14]. |

| High background noise or ghost peaks [14] [15] | Contamination of the injection system or column from previous runs; Carryover from poorly cleaned vials. | Run blank samples to identify contamination source; Perform regular cleaning of injection system and use pre-cleaned vials [14]. |

| Progressive retention time drift [14] [18] | Unstable incubation or oven temperature; Mobile phase issues (evaporation, poor preparation); Leaching from system components. | Calibrate temperature controllers; Ensure mobile phase is fresh and properly prepared; For HILIC, use polymer (e.g., PFA) instead of borosilicate glass solvent bottles to prevent ion leaching [18]. |

| Poor peak shape (tailing or fronting) [15] | Column degradation (voids, channels); Inappropriate buffer capacity; Strong sample solvent. | Replace column if degraded; Increase buffer concentration; Dissolve sample in the starting mobile phase composition [15]. |

Diagnostic Workflow

This flowchart outlines a logical process for diagnosing issues related to poor repeatability and sensitivity.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Minimum LC Column Equilibration Volume

This protocol provides a systematic method to determine the sufficient re-equilibration volume for a liquid chromatography method, crucial for achieving stable retention times [13].

1. Principle: After a gradient run, the column must be flushed with the initial mobile phase composition to re-establish the original interaction environment. The required volume is determined by monitoring the stability of a critical peak's retention time.

2. Materials:

- HPLC or UHPLC system

- Column under investigation

- Standard test mixture

- Mobile phases A and B, as per method

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Set the method with a shallow gradient (e.g., 5-95% B over 30 min) followed by a re-equilibration segment at initial conditions (e.g., 5% B).

- Step 2: Inject the standard mixture repeatedly without changing the method. Start with a re-equilibration volume estimated at 5 column volumes (V_M).

- Step 3: Record the retention time of the first eluting significant peak in each run.

- Step 4: Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the retention times for a sequence of 5-10 injections.

- Step 5: Incrementally increase the re-equilibration volume (e.g., to 7, 10, 15 V_M) and repeat the sequence until the RSD of the retention time is ≤ 1%.

4. Data Analysis: The minimal equilibration volume is the lowest volume that produces retention time RSD ≤ 1%. Using this volume ensures repeatability without unnecessarily extending the cycle time.

Protocol 2: Investigating the Salting-Out Effect in Headspace GC

This protocol outlines how to optimize the "salting-out" technique to improve the sensitivity and repeatability of volatile compound analysis in headspace GC by promoting their transfer from the liquid to the gas phase [14].

1. Principle: Adding a neutral salt (e.g., NaCl, Na₂SO₄) to an aqueous sample decreases the solubility of organic analytes, increasing their concentration in the headspace gas and improving detector response.

2. Materials:

- Headspace GC system

- Standard solution of target volatile analytes

- Saturated salt solution (e.g., NaCl) or anhydrous salt

- Headspace vials and seals

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Prepare a series of identical standard solutions in headspace vials.

- Step 2: To each vial, add different, precisely weighed amounts of the salt (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 g). Keep the total liquid volume constant.

- Step 3: Seal the vials and analyze them using consistent headspace conditions (incubation time, temperature, injection volume).

- Step 4: Measure the peak area for the target analytes in each vial.

4. Data Analysis: Plot the peak area of each analyte against the amount of salt added. The optimal salt concentration is identified as the point where the peak area response plateaus. Further increasing the salt provides no significant benefit and may damage the instrument.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| PFA Solvent Bottles | Prevents leaching of ions (e.g., sodium, borate) from borosilicate glass into HILIC mobile phases, a key cause of poor retention time repeatability [18]. |

| High-Purity Neutral Salts (NaCl, Na₂SO₄) | Used to induce the "salting-out" effect in headspace GC, improving the partitioning of volatile analytes into the gas phase and boosting sensitivity [14]. |

| Automated Headspace Sampler | Provides uniform vial heating and consistent injection, minimizing variability caused by manual handling and improving the repeatability of headspace analysis [14]. |

| Polar-Embedded or High-Purity Silica Columns | Reduces undesirable interactions (e.g., with silanol groups) for analyzing basic compounds, leading to better peak shape and more reproducible results [15]. |

| Electronic Pressure Control (EPC) Systems | Maintains stable carrier gas pressure/flow in GC, a critical factor for preventing retention time drift and ensuring repeatable analyses [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is stochastic ice nucleation and why is it a problem in pharmaceutical freeze-drying?

Stochastic ice nucleation refers to the random and unpredictable nature of ice crystal formation during the freezing step of lyophilization. Due to a lack of nucleation sites in pure systems, the solution must be supercooled, often significantly below its equilibrium freezing point, for ice crystals to form [19]. This results in vials within the same batch nucleating at different times and temperatures, leading to widespread heterogeneity [20] [19]. One vial might nucleate at -7°C while another, identical vial nucleates an hour later at -18°C, making the vials fundamentally different from the start [19].

Q2: How does the nucleation temperature impact the efficiency of the primary drying phase?

The ice nucleation temperature is a primary determinant of ice crystal size, which directly influences the resistance to vapor flow during sublimation. A lower nucleation temperature (higher supercooling) produces smaller ice crystals, resulting in smaller pores in the dried cake and higher resistance to mass transfer. This significantly slows down primary drying. Studies indicate that primary drying time can be extended by 1–3% for every 1°C decrease in ice-nucleation temperature [19]. By controlling nucleation to reduce supercooling, primary drying times can potentially be decreased by 10–30%, offering substantial time and cost savings [19].

Q3: What are the critical product quality attributes affected by uncontrolled nucleation?

Uncontrolled nucleation can adversely affect several critical quality attributes:

- Protein Stability: Colder nucleation creates smaller ice crystals with a larger cumulative surface area. Since proteins can aggregate at the ice-water interface, this larger surface area increases the aggregation stress on sensitive proteins, potentially compromising biological activity [19].

- Batch Uniformity: Vial-to-vial variations in pore structure lead to differences in residual moisture, reconstitution time, and cake appearance [19]. This makes true batch uniformity impossible to achieve without nucleation control.

- Cake Morphology: The nucleation behavior influences cosmetic properties like cake cracking, glazing, and stratification [19].

Q4: How do thermal interactions between vials contribute to batch heterogeneity?

In a densely packed batch, vials are not thermally isolated. The heat released from a vial as its contents freeze can be transferred to its neighboring vials. This thermal coupling can delay ice nucleation in adjacent vials and alter their freezing rate in a complex way [21] [22]. This interaction exacerbates the inherent stochasticity of nucleation, leading to a broader distribution of pore sizes and, consequently, drying times across the batch [21].

Q5: What practical loading configurations can help minimize thermal interactions between vials?

Research has shown that specific loading configurations can mitigate these effects:

- Using Empty Vials as Spacers: Placing empty vials between filled ones can significantly reduce thermal interactions [22].

- Employing Non-Contact Holders: Using customized holed spacers or supports that suspend vials above the shelf and separate them from each other minimizes vial-to-vial contact and heat transfer [22].

- Utilizing Vial Holders: Aluminum vial holders can help reduce temperature deviation between samples, though their effect on the radiative heat transfer component may be limited [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Freezing-Related Inefficiencies

| Problem | Root Cause | Experimental Evidence & Data | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prolonged & Variable Primary Drying Times | High degree of supercooling during freezing, leading to small ice crystals and high dry layer resistance. | Primary drying time increases 1-3% per 1°C drop in nucleation temp; Potential for 40% reduction in drying time with controlled nucleation [19]. | Implement controlled ice nucleation (e.g., ice fog, depressurization). |

| Vial-to-Vial Heterogeneity in Cake Appearance & Moisture | Stochastic nucleation causes a wide distribution of ice crystal sizes and pore structures within a batch. | In a lab freeze-dryer, nucleation temperature can span a 10–15°C range, and over 20°C in a production dryer [19]. | Use an annealing step or adopt controlled nucleation. Ensure temperature equilibration before freezing [24]. |

| Low Recovery of Protein Activity | Increased surface-induced denaturation/aggregation due to high ice-water interfacial area from small crystals. | Smaller ice crystals from colder nucleation have a larger surface area, increasing exposure of proteins to the destabilizing interface [19]. | Optimize formulation with protective excipients. Employ controlled nucleation to maximize ice crystal size. |

| Vial Breakage During Drying | Metastable states of formulation components formed during uncontrolled freezing can rearrange upon heating, generating internal stress. | The nucleation temperature affects the freezing kinetics and the formation of these metastable states [19]. | Control the nucleation temperature and freezing protocol. Modify formulation composition. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Nucleation Effects

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Impact of Thermal Interactions

Objective: To characterize how vial spacing and loading configuration affect the distribution of nucleation times and temperatures within a batch [22].

Materials:

- Vials (e.g., 2R or 20R)

- 5 wt% Sucrose solution as a model formulation

- Lab-scale freeze-dryer

- Temperature probes and video camera for nucleation detection

Methodology:

- Prepare Configurations: Load vials in different configurations (see diagram below) on the freeze-dryer shelf:

- Configuration A (Standard): Vials in direct contact with each other and the shelf.

- Configuration D (Spaced): Each filled vial surrounded by six empty vials.

- Configuration E (Isolated): Vials separated by a customized holed spacer (~6mm gap).

- Freezing Cycle: Cool the shelf to -45°C at a rate of 0.5°C/min [22].

- Data Collection: Use video recording to visually detect the exact moment of ice nucleation (seen as a sudden whitening) in each vial. Record the time and shelf temperature for each nucleation event.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the nucleation temperature for each vial. Compare the mean, standard deviation, and distribution range of nucleation temperatures across the different loading configurations.

Protocol 2: Correlating Nucleation Temperature with Primary Drying Time

Objective: To empirically establish the relationship between the degree of supercooling and the duration of the primary drying segment.

Materials:

- Array of vials filled with the product formulation.

- Tunable freeze-dryer equipped with a controlled nucleation device (e.g., ice fog or depressurization).

- Temperature probes and a pressure gauge.

Methodology:

- Split Batch: Divide a single batch of vials into two groups.

- Differential Freezing:

- Group 1 (Uncontrolled): Run a standard freezing cycle where nucleation occurs stochastically.

- Group 2 (Controlled): Use the controlled nucleation device to initiate ice formation at a specified, higher temperature (e.g., -2°C to -5°C).

- Primary Drying: Subject both groups to identical primary drying conditions (shelf temperature and chamber pressure).

- Measurement: Use pressure rise tests or continuous product temperature monitoring to determine the endpoint of primary drying for each group.

- Analysis: Compare the average primary drying time and the vial-to-vial variance between the controlled and uncontrolled groups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Solution (5 wt%) | A common, well-characterized model formulation for amorphous freeze-dried cakes [22]. | Represents the behavior of many sugar-based biologic stabilizers. |

| 2R & 20R Glass Vials | Standard container formats for small-scale and production-scale lyophilization studies [22]. | Vial type and bottom geometry significantly impact heat transfer. |

| Ethylene Glycol Solution | Used in thermal interaction studies as a non-freezing fluid to isolate thermal effects [22]. | Has a much lower freezing point (-36°C) than aqueous solutions. |

| Lab-Scale Freeze-Dryer | Provides controlled shelf temperature and chamber pressure for experimentation [22]. | Should be capable of running customized temperature/pressure ramps. |

| Controlled Nucleation Device | Technology (e.g., ice fog, depressurization) to initiate ice formation at a defined temperature [19]. | Critical for moving from observational studies to process control. |

| High-Speed Video Camera | For visually detecting and pinpointing the exact time and location of ice nucleation [22] [25]. | Essential for collecting statistical nucleation data. |

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Establishing Robust Temperature and Equilibration Protocols

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Chromatographic Peak Areas

- Q: My peak areas are highly variable between runs, even when using the same nominal concentration. What could be wrong?

- A: This is a classic symptom of non-standardized sample preparation. Inconsistent solvent composition or volume can lead to varying degrees of solvent evaporation, analyte re-dissolution, and injection volume inaccuracies. Ensure the sample solvent matches the mobile phase composition as closely as possible and that all samples are prepared to the same final volume in vials with consistent internal dimensions.

Issue: Poor Mass Spectrometry Ionization Efficiency

- Q: Why is my analyte signal suppressed in LC-MS, and how is sample preparation related?

- A: Ion suppression is frequently caused by matrix effects from non-volatile salts or incompatible solvents. Salts can precipitate and deposit in the ion source, while a high-water content sample injected into a strong organic mobile phase can cause poor analyte focusing at the head of the column. Use volatile additives (e.g., ammonium formate/acetate) and ensure the sample solvent strength is equal to or less than the initial mobile phase conditions.

Issue: Variable Analyte Recovery During Extraction

- Q: My extraction recovery is unpredictable. How can I stabilize it?

- A: Inconsistent pH, ionic strength, and solvent volume are primary culprits. The addition of a consistent amount of salt (e.g., for salting-out effects) and buffer is critical for reproducible liquid-liquid extraction. For solid-phase extraction, the conditioning and equilibration steps are highly dependent on solvent volume and composition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Q: How does vial temperature and equilibration time interact with my sample solvent?

A: An improperly set vial temperature can cause your sample solvent to be out of equilibrium with the column temperature. If the sample solvent is stronger than the mobile phase, a cold vial can lead to peak splitting and broadening as the analyte focuses poorly. A hot vial can cause pre-injection degradation or solvent evaporation. Consistent equilibration time ensures the entire sample is at the set temperature, which is critical for reproducible injection volumes, especially with autosamplers that draw a precise volume of a potentially variable-temperature liquid.

Q: What is the maximum allowable injection volume for my method?

A: The maximum volume depends on the column dimensions, the strength of your sample solvent relative to the mobile phase, and the analyte's retention. A sample solvent significantly weaker than the mobile phase allows for larger injection volumes. The table below provides general guidance for a 4.6mm ID column.

Q: Can I use a different salt than what is specified in the protocol?

- A: It is not recommended. Switching from a volatile salt (e.g., ammonium acetate) to a non-volatile salt (e.g., sodium phosphate) will cause long-term source contamination and signal suppression in MS. Even between volatile salts, the different ions can affect chromatographic selectivity and ionization efficiency.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Sample Solvent Strength on Peak Shape and Area

| Sample Solvent Composition | Injection Volume (µL) | Observed Peak Area (mAU*s) | %RSD (n=6) | Peak Shape (Asymmetry Factor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% Acetonitrile / 90% Water | 10 | 550 | 1.5% | 1.1 |

| 50% Acetonitrile / 50% Water | 10 | 510 | 4.8% | 1.9 |

| 10% Acetonitrile / 90% Water | 20 | 1105 | 1.7% | 1.1 |

| 50% Acetonitrile / 50% Water | 20 | 980 | 12.5% | 2.5 |

Conditions: Analyte: Caffeine; Column: C18, 4.6 x 150mm, 5µm; Mobile Phase: 20% Acetonitrile/80% Water, isocratic; Flow: 1.0 mL/min.

Table 2: Effect of Salt Additive on Liquid-Liquid Extraction Recovery

| Salt Additive | Concentration | Extraction Recovery (%) | %RSD (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | - | 65 | 8.2 |

| Sodium Chloride | 0.1 M | 78 | 5.1 |

| Sodium Chloride | 0.5 M | 95 | 1.8 |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Saturated | 92 | 2.1 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal Injection Volume and Solvent

- Prepare a stock solution of your analyte in a suitable solvent.

- Dilute the stock solution to the same final concentration using solvents of varying strength (e.g., 10%, 30%, 50% organic).

- Inject increasing volumes (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 20 µL) of each sample solvent onto your LC system.

- Monitor peak area, shape (asymmetry), and retention time consistency.

- Vial Temperature Context: Perform this experiment at your standard autosampler vial temperature (e.g., 10°C). Repeat at a higher temperature (e.g., 25°C) to observe if thermal mismatches exacerbate the issues.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Salt Additive for Extraction Recovery

- Spike your analyte into a blank biological matrix (e.g., plasma, urine).

- Aliquot the spiked matrix into three tubes.

- To Tube 1: Add extraction solvent only. To Tube 2: Add extraction solvent + 0.1 M NaCl. To Tube 3: Add extraction solvent + 0.5 M NaCl.

- Vortex mix all tubes for the same duration (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Centrifuge and transfer the organic layer.

- Evaporate and reconstitute all samples in the same volume of mobile phase-compatible solvent.

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS and compare peak areas against a neat standard to calculate % recovery.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Sample Prep Impact on LC-MS Data Quality

Diagram 2: Vial Temp & Equilibration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Volatile Salts (e.g., Ammonium Acetate/Formate) | Provides controlled ionic strength for extraction and pH stability without causing ion source contamination in LC-MS. |

| LC-MS Grade Water & Organic Solvents | Minimizes background noise and ion suppression caused by impurities in lower-grade solvents. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | Corrects for analyte loss during preparation and injection volume variability. A stable isotope-labeled IS is ideal. |

| Buffers (e.g., Formic Acid, Ammonium Bicarbonate) | Maintains a consistent pH, which is critical for the stability and chromatographic behavior of ionizable analytes. |

| Anti-adsorptive Additives (e.g., TFA, HFBA) | Reduces analyte loss due to adsorption to vial and tubing surfaces, particularly for peptides and basic compounds. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is vial geometry important for determining incubation temperature in freeze-drying? Vial geometry directly influences how heat is transferred from the shelf to the product. The vial's bottom curvature and the contact area between the vial and the shelf are critical factors. Variability in these geometrical dimensions can lead to a distribution of vial heat transfer coefficients (Kv), causing uneven product temperatures and potentially compromising quality [26]. Recent manufacturing techniques like the "press-blow" method can create vials with more uniform wall thickness, leading to superior heat transfer characteristics compared to traditional "blow-blow" vials [27].

2. What is the difference between a sequential and a dual-incubation temperature strategy? A sequential incubation strategy uses a single temperature for the entire incubation period. A dual-incubation strategy uses two different temperature ranges during the incubation process, typically transferring samples from one temperature to another. This is often done to recover a broader range of microorganisms; for example, lower temperatures (e.g., 20-25°C) favor fungal growth, while higher temperatures (e.g., 30-35°C) favor bacteria [28]. The order of incubation (low-to-high or high-to-low) can also impact the recovery of different microbial types.

3. How can I troubleshoot low recovery rates in my environmental monitoring incubation? Low recovery can stem from several factors related to incubation. First, review whether your incubation times are sufficient; some stressed microorganisms from the environment may exhibit a longer lag phase and require more time to grow [28]. Second, evaluate if your temperature range is appropriate for the expected microbiota. Finally, ensure you are using a culture medium that can support the growth of the organisms you wish to recover. Conducting in-situ studies can help determine the optimal incubation parameters for your specific cleanroom environment [28].

4. What are some common sources of error when running incubation experiments? Errors can be systematic or random. Systematic errors include flaws in experimental design or procedure, such as using uncalibrated temperature monitoring equipment or incorrect culture media. Random errors are unpredictable and can arise from intrinsic variability in biological systems or minor, unmeasured changes in the experiment's environment. A key practice to mitigate these errors is to use a large sample size and take multiple measurements [29].

5. How does the "QbD" (Quality by Design) initiative relate to incubation parameter development? The QbD approach, advocated by regulatory bodies, requires a deep understanding of how process parameters, like incubation time and temperature, influence the critical quality attributes of the final product. For freeze-drying, this means understanding how vial heat transfer (Kv) impacts product temperature. Defining the acceptable range for vial geometry and understanding its effect on heat transfer is a direct application of QbD to ensure uniform product quality [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Incubation Parameter Optimization

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common issues encountered when developing incubation parameters.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low recovery of target organisms | Incubation time too short; incorrect temperature range | Extend incubation duration based on growth curve studies; adjust temperature to match target organism's optimal growth range [28]. |

| Uneven product quality in freeze-dried batch | High variability in vial heat transfer coefficients (Kv) | Source vials with more consistent geometry (e.g., PB molded vials); characterize Kv distribution for your vial lot and freeze-dryer [27] [26]. |

| High rate of non-reproducible results | Unidentified random errors in procedure | Increase sample size and replicate measurements; implement lab automation for manual tasks like specimen handling to reduce human error [29]. |

| Inability to scale up process | Edge vial effects and differences in equipment | During scale-up, account for different heat transfer characteristics, such as chamber wall emissivity and shelf separation distance; perform Kv mapping [27]. |

| Crystallization or collapse during freeze-drying | Product temperature exceeding critical threshold | Optimize shelf temperature and chamber pressure based on known Kv values to ensure product temperature remains below the critical point throughout primary drying [26]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Gravimetric Determination of Vial Heat Transfer Coefficient (Kv)

Objective: To accurately determine the vial heat transfer coefficient for a specific vial and freeze-dryer combination, a critical parameter for designing an optimal freeze-drying cycle.

Methodology:

- Materials: Vials (to be tested), distilled water, calibrated thin-wire thermocouples, analytical balance, freeze-dryer.

- Procedure:

- Fill vials with a known mass of distilled water.

- Place the vials on the freeze-dryer shelf. For mapping, include vials in both center and edge positions.

- Load the product and initiate the freezing phase to solidify the water.

- Begin the primary drying phase by setting the shelf temperature (Ts) and chamber pressure (Pc). The sublimation rate (dm/dt) is determined by measuring the mass loss over time.

- The vial heat transfer coefficient, Kv, is calculated using the following equation, where ΔH is the latent heat of sublimation and Ab is the outer vial bottom area [26]:

Kv = (ΔH * dm/dt) / (Ab * (Ts - Tb))

- Key Considerations: This gravimetric method is considered the gold standard for determining Kv as it provides data for individual vials, but it is time-consuming. Other methods like TDLAS can also be used [27].

Protocol 2: Establishing Optimal Incubation Time for Environmental Monitoring

Objective: To determine the shortest sufficient incubation time that yields maximum microbial recovery for environmental monitoring samples.

Methodology:

- Materials: Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA) contact plates, typed microbial cultures, incubators at different temperatures.

- Procedure:

- In-Vitro Testing: Inoculate TSA plates with low levels (10-100 CFU) of relevant microorganisms. Incubate replicates at different temperature regimes (e.g., 20-25°C and 30-35°C). Perform daily plate counts for up to 15 days [28].

- In-Situ Testing: Collect surface samples from various cleanroom locations in triplicate. Incubate using the same regimes as in-vitro testing and perform daily counts [28].

- Data Analysis: Use statistical tests (e.g., unpaired Student's t-test) to compare daily colony counts. The optimum incubation time is identified as the period after which no statistically significant increase in colony count is observed [28].

Table 1: Example Incubation Parameters from Regulatory Guidelines

| Application | Recommended Temperature | Recommended Time | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Testing | 30-35°C | 48-72 hours (USP) ≤5 days (EP) | [30] |

| Environmental Monitoring (EM) | 20-35°C | Not less than 72 hours | [30] |

| EM for Vaccine Manufacturing | 20-25°C followed by 30-35°C | 3-5 days + additional 2-3 days | [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Vial Heat Transfer and Incubation Studies

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Tubing or Molded Glass Vials | The primary container for freeze-drying; their geometry (e.g., bottom curvature, contact area) is a critical variable under investigation [27] [26]. |

| Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA) | A general-purpose culture medium used widely in environmental monitoring for the recovery of bacteria and fungi [28]. |

| Calibrated Thermocouples | For accurate temperature measurement of the shelf and product during freeze-drying studies [26]. |

| Analytical Balance | Used in the gravimetric method to determine mass loss (sublimation rate) for calculating the vial heat transfer coefficient (Kv) [26]. |

| Calibrated Hygrometer | Measures relative humidity inside an incubator, a critical parameter for many biological incubations [31] [32]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Method Optimization Workflow

Heat Transfer in Vials

Leveraging Automated Systems for Uniform Heating and Injection to Minimize Human Error

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Temperature Uniformity Across Sample Vials

Problem Description Researchers observe varying results between edge and center wells in a 96-well plate during heated incubation, indicating poor temperature uniformity.

Diagnostic Steps

- Thermal Mapping: Perform a thermal profile of the heating system. Strategically place calibrated K-type thermocouples in various locations, including center wells, edge wells, and different levels of the sample block or bath [33] [34]. Record temperatures at defined intervals over a full operational cycle.

- Identify Heat Sources: Diagnose the instrument for local heat-generating components (e.g., motors, electronic drivers) that may be causing thermal skewing [34].

- Verify Calibration: Check the calibration of the heating system's internal sensors and controller against a traceable reference standard [35].

Solutions

- Hardware Optimization: If profiling identifies a specific component as a heat source, work with the manufacturer to explore hardware design changes. For example, optimizing a motor design to provide required torque at a lower current can reduce unwanted heat [34].

- Implement Closed-Loop Control: Ensure the system uses a closed-loop, active heating system with real-time data logging to maintain consistent temperatures [34].

- Use Validated Heating Methods: For water baths, submerging a sealed microplate provides faster and more uniform heat transfer compared to simply floating it on the surface [33]. The table below summarizes experimental data for heating a 96-well plate.

Table 1: Comparison of Heating Methods for a 96-Well Plate (Data adapted from [33])

| Heating Method | Description | Time to Reach ~55°C (from ~20°C) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floating in Water Bath | Sealed plate floated on surface of a 55°C water bath. | ~12 minutes | Slower heat transfer, significant well-to-well gradient. |

| Submerged in Water Bath | Sealed plate fully submerged in a 55°C water bath. | ~4 minutes | Faster, more uniform heating. |

| Domestic Microwave | Low power, unsealed plate. | Highly variable (seconds) | Extreme gradients between edge and center wells; not recommended. |

Issue 2: Inaccurate or Irreproducible Equilibration Times

Problem Description The time required for samples to reach thermal equilibrium in a headspace autosampler is unpredictable, leading to inconsistent analyte concentrations in the headspace gas [36].

Diagnostic Steps

- Review Method Parameters: Verify the set equilibration temperature and time in the autosampler method.

- Check Septa Integrity: Inspect vial septa for signs of degradation or leaks, which can be caused by exposure to high temperatures [36].

- Confirm Vial Pressurization: Ensure the autosampler's pressurization step is functioning correctly. Inadequate pressurization can lead to an early, reverse pulse of sample gas, causing poor repeatability [36].

Solutions

- Optimize Equilibration Temperature: Choose a temperature at least 15°C above room temperature for good thermal control, but stay within the limits of analyte and septum stability [36].

- Utilize Agitation: If available, enable mechanical mixing of the vials during equilibration to accelerate the partitioning of analytes into the headspace [36].

- Standardize Sample Handling: Use consistent pre-vial sample handling procedures at reduced temperatures to minimize the loss of very volatile components before sealing [36].

Issue 3: Variable Automated Injection Volumes

Problem Description Peak areas in chromatography are inconsistent, pointing to irregularities in the volume of sample injected by an automated system.

Diagnostic Steps

- Inspect Liquid Handling Technology: Determine if the system uses air displacement, positive displacement, or non-contact technology. Air displacement can be inaccurate with viscous or volatile liquids [37].

- Check for Carryover: Run a blank sample after a high-concentration sample to check if the system is adequately washing or using fresh tips to prevent contamination.

- Verify Pneumatics (for Headspace): In balanced-pressure headspace systems, ensure sampling timings are precise and that vial pressure does not decay excessively during the sample transfer interval [36].

Solutions

- Match Technology to Liquid: Use positive displacement pipetting for viscous or volatile liquids to eliminate the compressible air cushion [37].

- Implement Automated Calibration: For systems requiring extreme precision, use instruments that support a fully automated calibration procedure to baseline each thermal cell or pipetting channel, applying offset values for precise control [34].

- Maintain System Components: Follow the manufacturer's schedule for maintenance and replacement of critical parts like syringe seals, valves, and tubing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key benefits of automating heating and injection processes in the lab? Automation significantly enhances experimental outcomes by:

- Improving Precision and Consistency: Automated systems maintain tighter tolerances for temperature and time, drastically reducing human error and variability [38] [37].

- Increasing Throughput: Robots can operate 24/7, handling large sample batches much faster than manual processing [38] [37].

- Enhancing Data Integrity: Automated data logging provides a complete, time-stamped record of process parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure) for full traceability and compliance [38] [35].

- Improving Researcher Safety: Automated systems handle hot surfaces, hazardous chemicals, and repetitive tasks, reducing risk of injury [38].

Q2: My temperature-sensitive biologics require strict control. How can I validate my automated storage unit? Thermal validation is a systematic process [35]:

- Planning: Define the temperature range and identify critical monitoring points.

- Calibration: Calibrate all external data loggers and sensors against a known standard.

- Mapping: Place sensors throughout the unit (top, bottom, center, edges, near door) to record temperature variations over a sufficient period (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- Stability Testing: Verify the unit maintains the required temperature over time under normal operation.

- Documentation: Compile all data, calibration certificates, and a deviation analysis into a formal report.

- Ongoing Monitoring & Revalidation: Implement continuous monitoring with alerts and revalidate periodically or after any equipment changes [35].

Q3: What is the most common mistake when setting up a headspace autosampler method? A common mistake is neglecting the pressurization phase. If the vial pressurization is not correctly set, sample gases can prematurely escape or be diluted, leading to double peaks, poor repeatability, and inaccurate quantitation [36].

Q4: We are implementing an automated liquid handler. What are the main cost considerations? Consider both upfront and long-term costs [37]:

- Upfront Investment: Purchase price of the system, which varies by functionality and complexity.

- Consumables: Ongoing cost of pipette tips, tubes, and plates.

- Service and Maintenance: Costs for regular maintenance and technical support.

- Training: Ensuring staff is proficient in operating and troubleshooting the system. While the initial investment can be significant, the long-term savings from increased efficiency, reduced labor, and minimized reagent waste often provide a strong return on investment [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Automated Vial Heating and Injection Experiments

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Inert HPLC Vials/Columns | Sample containers and separation media with passivated, metal-free surfaces. | Prevents adsorption and degradation of metal-sensitive analytes like phosphorylated compounds, improving recovery and peak shape [39]. |

| Validated Thermal Packaging | Insulated shippers with phase-change materials (e.g., gel packs). | Critical for cold chain logistics; validated packaging maintains precise temperature ranges during transport of temperature-sensitive pharmaceuticals [40]. |

| K-Type Thermocouples | High-accuracy temperature sensors for data acquisition and validation. | Used for thermal mapping and profiling of equipment to identify gradients and validate system performance [33] [34]. |

| Automated Pipetting System | Robotic system for precise liquid transfer. | Increases throughput and reproducibility. Choice of air displacement, positive displacement, or non-contact technology depends on volume and liquid properties [37]. |

| IoT Wireless Sensors | Real-time monitoring devices for temperature and humidity. | Provide continuous data streams and immediate alerts for temperature excursions during storage or transit, enabling proactive intervention [40]. |

Experimental Workflow and Diagnostics

The following diagrams outline the core workflow for optimizing vial temperature and the logical process for diagnosing common heating issues.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Vial Temperature Optimization

Diagram 2: Diagnosing Heating Inconsistency

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Headspace-Gas Chromatography (HS-GC)

Q1: We observe poor peak area reproducibility in our HS-GC analysis of residual solvents. What are the primary factors to investigate?

A: Poor reproducibility is frequently linked to inadequate control of vial temperature and equilibration time.

- Cause 1: Incorrect Equilibration Time. The system has not reached a state of equilibrium between the sample matrix, the headspace, and the vial temperature.

- Solution: Perform a time-profile experiment. Analyze the same sample at different equilibration times (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 min) and plot the peak area against time. The optimal time is when the peak area plateaus.

- Cause 2: Inconsistent Vial Temperature. A poorly calibrated or malfunctioning oven/heating block creates temperature gradients between vials.

- Solution: Regularly calibrate the HS sampler temperature using a calibrated thermometer. Ensure the vial septum is properly pierced to prevent pressure loss.

Q2: Our chromatograms show split peaks or "ghost" peaks. What is the likely cause?

A: This is typically a symptom of a leak in the system, either at the vial septum or within the transfer line.

- Cause: A compromised septum or a loose fitting in the transfer line allows for air ingress or sample loss.

- Solution: Replace the septum and ensure the vial cap is crimped correctly. Check all fittings in the transfer line from the HS sampler to the GC inlet for tightness. Perform a system leak check.

Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying)

Q3: Our product collapses during primary drying, resulting in a poor cake structure and high residual moisture. How can we prevent this?

A: Collapse occurs when the product temperature exceeds the collapse temperature (T꜀) during primary drying.

- Cause: The vial temperature at the bottom (shelf temperature) is too high, or the chamber pressure is too low, causing excessive sublimation heat.

- Solution: Optimize the freeze-drying cycle. Determine the product's T꜀ using Freeze-Dry Microscopy. Set the shelf temperature during primary drying significantly below the T꜀. Implement a controlled, ramping protocol for shelf temperature and chamber pressure.

Q4: How does equilibration time during freezing impact the final lyophilized product?

A: The equilibration or "annealing" time after freezing is critical for ice crystal growth and primary drying efficiency.

- Cause: Rapid freezing creates small, amorphous ice crystals, leading to a dense cake with high resistance to vapor flow.

- Solution: Introduce an annealing step. After the initial freeze, raise the temperature to just below the product's eutectic point, hold for several hours, then re-cool. This allows for the growth of larger ice crystals, creating larger pores for more efficient sublimation.

Crystallization Studies

Q5: We struggle with obtaining a consistent crystal form (polymorph) between experiments. What parameters are most critical to control?

A: Polymorphic control is highly dependent on the thermal and kinetic history of the solution.

- Cause: Inconsistent cooling rates, nucleation temperatures, and equilibration times at various temperature stages.

- Solution: Precisely control the vial temperature profile. Use a programmable thermal stage. The rate of cooling from dissolution to the nucleation point is a key parameter. Seeding with the desired polymorph at a controlled supersaturation can also ensure consistency.

Q6: How do we optimize the equilibration time for a cooling crystallization to prevent oiling out (liquid-liquid phase separation)?

A: Oiling out occurs when the solution becomes supersaturated too rapidly, preventing orderly molecular assembly into a crystal lattice.

- Cause: The cooling rate is too fast, not allowing sufficient time for molecules to find their lowest energy configuration.

- Solution: Perform a slow, controlled cooling ramp. Determine the metastable zone width (MSZW) for your system. Operate within the MSZW by using a slower cooling rate or introducing an isothermal hold (equilibration) period within the metastable zone to allow for controlled nucleation and growth.

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal HS-GC Equilibration Time

- Preparation: Prepare a standard solution of your target analyte at a known concentration.

- Loading: Aliquot identical volumes into multiple HS vials and crimp seal.

- HS-GC Program: Place all vials in the HS sampler. Program the method to use identical temperature, pressure, and agitation settings for all vials.

- Variable: Set a different equilibration time for each vial (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes).

- Analysis: Inject the headspace from each vial and record the peak area of the analyte.

- Optimization: Plot peak area vs. equilibration time. The optimal time is the point where the curve reaches a plateau, indicating equilibrium has been achieved.

Protocol 2: Determining Collapse Temperature (T꜀) via Freeze-Dry Microscopy

- Setup: Place a small droplet (1-5 µL) of the drug solution on a temperature-controlled FDM stage.

- Freezing: Cool the stage rapidly to a temperature well below the expected freezing point (e.g., -50°C).

- Primary Drying Simulation: Evacuate the chamber to a pressure typical for primary drying (e.g., 100 mTorr). Slowly ramp the stage temperature upward.

- Observation: Continuously observe the sample under polarized light. The T꜀ is identified as the temperature at which the porous, frozen structure begins to lose structural integrity and visibly viscous flow or collapse occurs.

Protocol 3: Mapping the Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) for Cooling Crystallization

- Saturation: Prepare a saturated solution of your compound in a jacketed vessel at a known elevated temperature (T₁), ensuring all solid is dissolved.

- Cooling: Initiate a constant, slow cooling rate (e.g., 0.1°C/min to 1.0°C/min) while stirring.

- Detection: Use an in-situ probe (e.g., FBRM, PVM, or turbidity probe) to monitor the solution.

- Data Collection: Record the temperature at which a sudden change in signal (e.g., particle count or turbidity) is detected, indicating nucleation (T₂).

- Calculation: The MSZW is the temperature difference between the saturation temperature (T₁) and the nucleation temperature (T₂), i.e., ΔT = T₁ - T₂. This experiment should be repeated to establish reproducibility.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Equilibration Time on HS-GC Peak Area for Acetone

| Equilibration Time (min) | Mean Peak Area (pA*s) | % Relative Standard Deviation (n=5) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 145,250 | 8.7% |

| 20 | 198,550 | 4.5% |

| 30 | 215,900 | 1.9% |

| 40 | 216,100 | 1.8% |

| 50 | 215,800 | 1.7% |

Table 2: Lyophilization Cycle Parameters for a Model Protein

| Process Step | Shelf Temperature (°C) | Chamber Pressure (mTorr) | Time (Hours) | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freezing | -50 | Ambient | 2 | Solidify product |

| Thermal Treatment | -25 | Ambient | 4 | Anneal for crystal growth |

| Primary Drying | -30 | 100 | 40 | Sublimate ice (T꜀ = -28°C) |

| Secondary Drying | +25 | 50 | 8 | Desorb bound water |

Visualizations

HS-GC Equilibration Optimization

Lyophilization Cycle Workflow

Crystallization MSZW Determination

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Vial-Based Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Certified HS Vials | Guaranteed seal integrity and low analyte adsorption for reliable headspace sampling. |

| Magnetic Crimp Caps & Septa | Provide a vacuum-tight seal for HS-GC vials and lyophilization containers. |

| Thermocouple Calibrator | Essential for verifying and calibrating the temperature of HS ovens and lyophilizer shelves. |

| In-Situ Process Analyzers | Tools like FBRM (Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement) and PVM (Particle Video Microscope) for real-time monitoring of crystallization. |

| Freeze-Dry Microscopy (FDM) | A specialized stage to visually determine the critical collapse temperature (T꜀) of a formulation. |

| Programmable Thermal Cycler | Provides precise control over vial temperature ramps and holds for crystallization and annealing studies. |

Diagnosing and Solving Common Problems: A Troubleshooting Guide for Temperature and Equilibration Issues

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Resolving Poor Repeatability in Diagnostic Models

Problem: Your machine learning model for symptom-based diagnosis shows high performance variance across different validation runs, making results unreliable.

Explanation: Poor repeatability often stems from overfitting and failure to generalize to new data, which is critical in clinical applications [41].

Solutions:

- Implement Rigorous Cross-Validation: Use 10-fold cross-validation, which splits data into 10 parts, training the model 10 times with a different part as the test set each time [41].

- Apply Hyperparameter Tuning: Utilize grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization to find optimal model parameters [41].

- Leverage Ensemble Methods: Combine multiple models (e.g., Random Forest, which aggregates many Decision Trees) to improve stability and predictive performance [41].

- Utilize Comprehensive Evaluation Metrics: Go beyond simple accuracy; use F1 scores, ROC-AUC curves, and precision-recall curves, with the latter being particularly useful for imbalanced datasets common in medical diagnostics [41].

Guide: Addressing Low Sensitivity in Symptom Checkers

Problem: Your diagnostic tool is missing true positive cases, failing to identify patients who actually have the condition.

Explanation: Low sensitivity (high false negative rate) poses significant clinical risks by delaying necessary treatment [41] [42].

Solutions:

- Optimize for Sensitivity-Specificity Balance: Analyze ROC curves to select a classification threshold that balances sensitivity and specificity appropriately [41].

- Address Dataset Imbalance: Employ precision-recall curve analysis, which provides a more informative view of model performance when dealing with imbalanced datasets where the condition of interest is rare [41].

- Incorporate Clinical Vignettes: Test your models against realistic patient scenarios curated by medical professionals to ensure they perform well in real-world situations [41].

- Feature Engineering: Enhance symptom representation using natural language processing (NLP) for free-text inputs and incorporate comprehensive patient histories from Electronic Health Records (EHRs) where available [41].

Guide: Eliminating Ghost Peaks in Analytical Chromatography

Problem: Unexpected "ghost peaks" appear in chromatograms during analysis, interfering with accurate quantitation.

Explanation: Ghost peaks are extraneous signals that can masquerade as analytes, potentially leading to incorrect diagnostic or quality control conclusions [43].

Solutions:

- Systematic Source Identification:

- Mobile Phase Management: Use fresh, high-purity solvents for mobile phase preparation and ensure proper degassing through helium sparging, vacuum degassing, or sonication [43].

- Preventive System Maintenance: Maintain autosampler components (needles, seats), replace worn pump seals, and use in-line filters to trap particulates [43].

- Column Care: Implement proper column storage and regeneration procedures, and use guard columns to protect analytical columns from contamination [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What evaluation framework ensures my symptom-based diagnostic model is clinically relevant? A comprehensive evaluation should include multiple techniques: 10-fold cross-validation to ensure generalizability, ROC-AUC analysis to assess classification performance, precision-recall curves specifically for imbalanced datasets, and validation against clinical vignettes to test real-world applicability [41].

FAQ 2: How can I improve vial-to-vial homogeneity in freezing processes for pharmaceutical development? Implement controlled nucleation techniques like ice fog nucleation, which introduces ice crystals into the chamber to provide uniform nucleation sites for all vials. This method has been shown to reduce the nucleation temperature range from 9°C to 0.8°C, significantly improving homogeneity [44].

FAQ 3: What are the most common sources of ghost peaks in HPLC analysis, and how do I identify them? Common sources include mobile phase contamination, system contamination (carryover from previous injections, contaminated autosampler components), column issues (aging columns, contaminated guard columns), and sample preparation errors. Systematic elimination through blank runs and component isolation is the most effective identification strategy [43].

FAQ 4: Why is controlling the freezing step so critical in lyophilization processes? The ice nucleation temperature is the primary determinant of ice crystal size and morphology, which directly impacts product stability, primary drying time, and final product quality. Uncontrolled nucleation leads to vial-to-vial variability within batches, affecting product consistency and critical quality attributes [44] [45].

Table 1: Machine Learning Model Performance Metrics for Symptom-Based Diagnosis

| Model | Accuracy | F1 Score | ROC-AUC | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | Not specified | Not specified | Varies by complexity | Interpretable models |

| Random Forest | Not specified | Not specified | High | Robust performance |

| Naive Bayes | Not specified | Not specified | Varies by complexity | Baseline modeling |

| Logistic Regression | Not specified | Not specified | Varies by complexity | Linear relationships |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | Not specified | Not specified | Varies by complexity | Similar symptom patterns |

Note: Specific accuracy and F1 scores were not provided in the search results, but the study indicated that performance generally improves with model complexity and proper validation [41].

Table 2: Impact of Induced Nucleation on Freezing Process Parameters

| Parameter | Without Induced Nucleation | With Induced Nucleation | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Time Range | 152 minutes | <2 minutes | ~98% reduction |

| Nucleation Temperature Range | 9°C | 0.8°C | 91% reduction |

| Primary Drying Time | Longer cycle | 12.4 hours earlier completion | Significant reduction |

| End of Primary Drying | Later completion | 5.4 hours earlier completion | Significant reduction |

Data compiled from production-scale freeze-dryer tests [44].

Table 3: Key Thermal Configuration Impacts on Nucleation Success

| Loading Configuration | Shelf Contact | Vial-Vial Contact | Impact on Nucleation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct shelf contact | Yes | Yes | Substantial thermal interactions, delayed nucleation |

| Shelf with tray | Indirect | Yes | Modified thermal transfer |

| Suspended above shelf | No | Limited | Reduced thermal interactions |

| Empty vials between filled | Yes | Yes | Significantly reduced thermal interactions |

| Spacer-separated | Yes | No | Minimal vial-vial thermal transfer |

| Glycol-filled buffers | Yes | Yes | Minimal inhibitory effect |

Data synthesized from experimental configurations testing thermal interactions [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: 10-Fold Cross-Validation for Diagnostic Models

Purpose: To ensure machine learning models for symptom-based diagnosis generalize well to unseen data and avoid overfitting.