Quality Control in Environmental Chemistry Labs: A 2025 Guide to Data Integrity, Compliance, and Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern quality control (QC) protocols for environmental chemistry laboratories, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Quality Control in Environmental Chemistry Labs: A 2025 Guide to Data Integrity, Compliance, and Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern quality control (QC) protocols for environmental chemistry laboratories, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles from regulatory bodies like the EPA, explores the application of trending methodologies such as digitalization and intelligent automation, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common data integrity issues. A comparative analysis of emerging frameworks like White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) is included to help laboratories validate their methods and strategically balance analytical performance with environmental and economic sustainability.

Building a Solid Foundation: Core Principles and Regulatory Frameworks for Environmental QC

In environmental chemistry laboratories, Quality Control (QC) is a structured process designed to ensure that the analytical data produced is reliable, accurate, and precise. For researchers and scientists in drug development and environmental science, robust QC protocols are not merely a regulatory formality but the foundation for credible scientific findings and environmental safety decisions. This technical support center outlines the critical role of QC and provides practical troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address common experimental challenges.

FAQs: Core Quality Control Concepts

1. What is the critical difference between Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC) in environmental chemistry?

Quality Assurance is the comprehensive, strategic system for ensuring data quality. It encompasses all the planned and systematic activities implemented to provide confidence that quality requirements will be fulfilled. Quality Control is a tactical, operational subset of QA. It consists of the specific technical activities used to assess and control the quality of the analytical data itself, such as running control samples and calibrating instruments [1].

2. Why are both a Laboratory Control Sample and a Matrix Spike required for accurate data assessment?

These two QC samples serve distinct but complementary purposes:

- Laboratory Control Sample: The primary purpose of the LCS is to demonstrate that the laboratory can successfully perform the overall analytical procedure in a matrix free of interferences. Its results verify that the laboratory's analytical system is in control [1].

- Matrix Spike/MS: The primary purpose of the MS is to establish the performance of the method relative to the specific sample matrix of interest. It helps identify and quantify measurement system accuracy for the actual media being tested, revealing any "matrix effects" that might interfere with analysis [2] [1].

3. How frequently should key QC samples be analyzed?

A typical frequency for many QC operations, such as matrix spikes and blanks, is once for every 20 samples (a 5% frequency). However, this is a general guideline. The appropriate frequency should be based on the project's Data Quality Objectives and the stability of the sample matrix. For long-term monitoring of a consistent matrix, a lower frequency may be justified with proper documentation [1].

4. What are the minimum QC procedures required for chemical testing?

A robust QC program should include demonstrations of initial, ongoing, and sample-specific reliability [2]. Key procedures are summarized in the table below:

| QC Procedure | Purpose | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Demonstration | Show the measurement system is operating correctly before analyzing samples. | Initial Calibration; Method Blanks [2]. |

| Method Suitability | Verify the analytical method is fit for its intended purpose. | Establishing Detection Limits; Precision and Recovery studies [2]. |

| Ongoing Reliability | Monitor the continued reliability of analytical results during a batch. | Continuing Calibration Verification; Matrix Spike/Matrix Spike Duplicates (MS/MSD); Laboratory Control Samples (LCS) [2] [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent QC Results Between Shifts or Personnel

Problem: Undetected errors and diagnostic variability occur due to inconsistent application of test protocols.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Gather Information: Review Standard Operating Procedures and calibration records for all shifts. Interview personnel to identify procedural differences.

- Identify Root Cause: Common causes include outdated SOPs, insufficient training, or reliance on manual documentation prone to transcription errors [3].

- Implement Corrective Actions:

- Standardize Practices: Use centralized digital tools like dashboards and electronic checklists to ensure all personnel follow the same protocols [3].

- Review and Update SOPs: Ensure SOPs are compatible with current instrumentation and regulatory standards [3].

- Enhance Training: Provide regular, standardized training for all staff, emphasizing the importance of consistent documentation and procedure adherence [4].

Issue 2: Elevated Quantitation Limits Above Regulatory Thresholds

Problem: Matrix interference effects cause the Limit of Quantitation to rise above the regulatory limit, making it impossible to prove compliance.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Gather Information: Confirm the analytical method, sample matrix, and the specific interferent. Check all sample preparation and dilution steps.

- Identify Root Cause: High LLOQ can be caused by overly high sample dilutions or a lack of appropriate clean-up procedures to remove interferents [1].

- Implement Corrective Actions:

- Optimize Sample Preparation: Avoid unnecessary high dilutions and employ a validated clean-up method specific to the interferent [1].

- Consult Regulatory Footnotes: For specific contaminants, regulatory documents may state that the quantitation limit itself becomes the regulatory level when it is demonstrably higher than the calculated limit [1].

- Document Everything: Meticulously document all steps taken to lower the reporting limit, as this is critical for regulatory review [1].

Issue 3: Unexplained Shifts or Trends in QC Data

Problem: Control sample results show a systematic shift or trend, indicating a potential loss of analytical control.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Gather Information: Check the Levey-Jennings chart to characterize the shift. Note any recent changes in reagents, calibrators, or instrument maintenance [5].

- Identify Root Cause: Use a systematic, split-half approach. Test major system components first (e.g., reagent lot, calibration standard) before moving to smaller sub-systems to efficiently isolate the faulty component [6]. Common causes include:

- Reagent/Calibrator Variation: A change in reagent or calibrator lot [5].

- Instrument Performance: Gradual instrument drift or a faulty component.

- Control Material: Deterioration of the QC material itself.

- Implement Corrective Actions:

- Based on the root cause, actions may include re-calibrating the instrument, replacing a reagent lot, or performing instrument maintenance.

- Schedule lot changes for reagents and QC materials on different days to isolate their effects more easily [5].

- Never report patient or environmental sample results until the QC problem is resolved and control is re-established.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard QC Protocol: Analysis of an Environmental Sample Batch

The following workflow details the key steps for processing a batch of environmental samples, integrating essential QC measures to ensure data integrity.

Quantitative Data: Essential QC Samples and Acceptance

The table below summarizes the core QC samples, their frequency, and function, which are critical for the protocol above.

| QC Sample | Typical Frequency | Purpose & Function | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method Blank | Once per batch [1] | Detects contamination from reagents, apparatus, or the lab environment. | Analyte concentration should be below the method detection limit. |

| Laboratory Control Sample | Once per batch or every 20 samples [1] | Verifies laboratory performance and method accuracy in a clean matrix. | Recovery of the spiked analyte should be within established control limits. |

| Matrix Spike / Matrix Spike Duplicate | Once per 20 samples or batch [2] [1] | Assesses method accuracy and precision in the specific sample matrix. | MS recovery and MSD precision should be within project-specific control limits. |

| Continuing Calibration Verification | Every 15 samples or at end of batch [1] | Confirms the initial calibration remains valid throughout the analytical run. | Recovery of the verification standard must be within specified method limits. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in QC |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides a known concentration of an analyte in a specific matrix. Used to calibrate instruments and verify method accuracy [3]. |

| QC Control Materials | Stable, homogeneous materials with known expected values. Run routinely to monitor the precision and stability of the analytical system over time [3]. |

| Method Blanks | A sample free of the analytes of interest taken through the entire analytical process. Critical for identifying contamination from solvents, glassware, or the lab environment [2] [1]. |

| Matrix Spike Solutions | A solution containing a known concentration of target analytes, used to spike sample matrices. Essential for determining the effect of the sample matrix on method accuracy [2] [1]. |

| Surrogate Standards | Compounds not normally found in environmental samples that are added to all samples. Used to monitor the efficiency of the sample preparation and analytical process for each individual sample [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

How do I determine if our laboratory is subject to both EPA and OSHA regulations?

EPA and OSHA regulations apply to different aspects of laboratory operations, and a lab can be subject to both. A 2025 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the EPA and OSHA has reinforced their coordination on chemical safety.

- EPA (Environmental Protection Agency): Jurisdiction covers the broader environment and the public. Compliance is required for activities like hazardous waste management (under RCRA), water discharge (under the Clean Water Act), and specific programs like the Environmental Sampling and Analytical Methods (ESAM) program for contamination incidents [7] [8].

- OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration): Jurisdiction is specifically the safety and health of employees in the workplace. The OSHA Laboratory standard (29 CFR 1910.1450) governs occupational exposure to hazardous chemicals in laboratories [9] [10].

- Key Difference: TSCA (EPA) regulates chemical use broadly, while the OSH Act protects workers. TSCA also covers a wider range of individuals, such as volunteers, self-employed workers, and some state and local government workers, who may not be covered by OSHA [10].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your lab handles hazardous chemicals and has employees, you are very likely subject to regulations from both agencies. Begin by designating a responsible person to map all chemicals and processes to the specific regulations from each agency.

Our lab is pursuing ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation. What are the most common reasons for non-conformities during the assessment?

The ISO/IEC 17025 standard specifies general requirements for the competence, impartiality, and consistent operation of testing and calibration laboratories [11]. Common pitfalls often relate to the management system and technical records.

- Inadequate Document Control: Failure to maintain robust control over documents like standard operating procedures (SOPs), quality manuals, and forms, ensuring they are current and approved.

- Poor Management of Corrective Actions: A lack of a systematic process for addressing non-conformities, including root cause analysis, implementation of corrective actions, and effectiveness verification [12].

- Insufficient Record Trails: Incomplete or inconsistent records of equipment calibration, maintenance, environmental monitoring, and testing activities, which prevents traceability [12].

- Failure to Demonstrate Impartiality: Absence of a risk management process to identify and mitigate potential conflicts of interest that could affect laboratory activities [13] [11].

Troubleshooting Tip: Conduct a thorough internal audit against all clauses of the ISO/IEC 17025 standard before the formal assessment. Use a checklist to ensure every requirement, especially for document control, corrective action, and data integrity, is met.

What are the key elements of an effective Chemical Hygiene Plan required by OSHA?

The OSHA Laboratory standard (29 CFR 1910.1450) requires a Chemical Hygiene Plan (CHP) to protect workers from health hazards associated with chemicals [9].

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs): Develop and implement SOPs for specific laboratory tasks and processes that involve hazardous chemicals.

- Exposure Control Measures: Detail the criteria and methods for implementing and maintaining engineering controls (e.g., fume hoods), administrative controls, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Employee Training and Information: Ensure all laboratory personnel receive appropriate and ongoing training about the hazards of chemicals in their work area and the contents of the CHP [9].

- Medical Consultation and Examinations: Establish procedures for employees to receive medical attention, including follow-up exams, if exposure monitoring indicates a likely overexposure.

- Designation of Personnel: Clearly assign a Chemical Hygiene Officer and identify the responsibilities of the department heads.

Troubleshooting Tip: A CHP must be a living document, not a static one. Review and update it at least annually or whenever new chemicals, processes, or significant equipment are introduced to the laboratory. Actively involve laboratory personnel in this process for practical effectiveness.

What should our lab do to prepare for an unannounced OSHA inspection?

Being prepared for an unannounced OSHA inspection requires having systems in place that are always audit-ready. Key focus areas for OSHA in 2025 include heat stress, warehousing operations, and combustible dust [14].

- Have a Designated Point Person: Ensure management and staff know who is authorized to greet and accompany the OSHA compliance officer.

- Keep Key Documents Accessible: Maintain an organized and current location for your OSHA 300 logs, injury and illness records, written safety programs (like your Chemical Hygiene Plan), training records, and equipment maintenance logs [7] [14].

- Conduct Regular Self-Audits: Perform internal audits using checklists that mirror what an OSHA inspector would use. This helps you proactively identify and correct issues [7].

- Verify Emergency Preparedness: Ensure emergency action plans are up-to-date and that drills (e.g., for fire evacuation or chemical spills) are conducted regularly [7].

Troubleshooting Tip: The best preparation is a strong, daily safety culture. Foster an environment where employees feel comfortable reporting hazards without fear of retaliation, and where safety protocols are consistently followed.

The following tables summarize key quantitative data for regulatory penalties and exposure limits.

Table 1: 2025 OSHA Civil Penalty Amounts

| Violation Type | Maximum Penalty |

|---|---|

| Serious & Other-Than-Serious Violations | $16,550 per violation |

| Failure to Abate | $16,550 per day beyond the abatement date |

| Repeat & Willful Violations | $165,514 per violation [14] |

Table 2: 2025 EPA Civil Monetary Penalties (Selected Statutes)

| Statute | Maximum Daily Penalty |

|---|---|

| Clean Air Act | $124,426 |

| Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) | $93,058 |

| Clean Water Act | $68,445 |

| CERCLA & EPCRA | $71,545 [14] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing an Integrated EPA-OSHA-ISO Compliance Program

This methodology provides a framework for building a cohesive compliance program that satisfies regulatory and international standard requirements.

1. Conduct a Regulation-to-Process Gap Analysis

- Objective: Systematically identify where current laboratory practices deviate from regulatory and standard requirements.

- Procedure:

- Create a master list of all applicable regulations (EPA, OSHA) and standards (ISO/IEC 17025).

- Map each requirement to specific laboratory processes, procedures, and records.

- For each requirement, document the current state of compliance and any gaps. This becomes the foundation for your corrective action plan [7] [15].

2. Develop and Implement Written Programs

- Objective: Translate regulatory and standard requirements into clear, actionable, and accessible laboratory documents.

- Procedure:

- Draft or update essential documents, including the Chemical Hygiene Plan (OSHA), quality manual (ISO/IEC 17025), and waste management plan (EPA).

- Ensure these documents are written in practical terms, readily available to all personnel, and reviewed/approved by management [7].

3. Establish Rigorous Documentation and Record-Keeping Processes

- Objective: Create an auditable trail of evidence to demonstrate compliance.

- Procedure:

- Implement a centralized system (e.g., a LIMS - Laboratory Information Management System) for managing records.

- Define and enforce protocols for data integrity, ensuring records for training, equipment calibration, testing, and corrective actions are complete, accurate, and tamper-evident [7] [12] [15].

4. Implement a Continuous Training Program

- Objective: Ensure all personnel are competent and aware of their compliance responsibilities.

- Procedure:

- Deliver initial training during onboarding, covering general safety, quality policies, and specific role-based procedures.

- Schedule and conduct annual refresher training.

- Provide specialized training whenever new equipment, chemicals, or procedures are introduced. Maintain detailed records of all training activities [7].

5. Conduct Regular Internal Audits and Management Reviews

- Objective: Proactively verify the effectiveness of the compliance program and drive continuous improvement.

- Procedure:

- Perform internal audits on a defined schedule (e.g., annually) using checklists based on regulatory and standard requirements.

- Hold regular management reviews to assess audit findings, incident reports, and the suitability of the compliance system, and to allocate resources for improvements [7] [15].

Compliance Program Workflow

Audit Preparation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quality Compliance

| Item | Function in Quality Control |

|---|---|

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | A software-based system (especially AI-powered) that serves as a central framework for managing samples, data, workflows, and instrumentation, directly supporting ISO/IEC 17025 compliance and audit readiness [12]. |

| EPA's Environmental Sampling and Analytical Methods (ESAM) | A comprehensive program providing validated sampling strategies and analytical methods for responding to intentional or accidental contamination incidents, ensuring defensible environmental data [8]. |

| Documented Quality Management System (QMS) | The structured framework of policies, processes, and procedures required by ISO/IEC 17025. It ensures consistent operations, technical competence, and impartiality, and is the foundation for all accredited work [11]. |

| Chemical Hygiene Plan (CHP) | The foundational, written OSHA-required program that outlines procedures, equipment, and work practices designed to protect employees from health hazards associated with hazardous chemicals in the laboratory [9]. |

| Internal Audit Program | A required process for periodically self-assessing the effectiveness of the QMS and compliance programs. It identifies non-conformities for corrective action before external assessments occur [7] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of each major QC sample type?

QC samples are fundamental for verifying data quality, and each type serves a distinct function in the environmental laboratory.

Table: Essential Quality Control Samples and Their Functions

| QC Sample Type | Primary Function | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Method Blank | Detects contamination or interference from the analytical process itself [16]. | A contaminated blank suggests the sample may have been compromised during preparation or analysis [17]. |

| Laboratory Control Sample (LCS) | Verifies that the laboratory can perform the analytical procedure correctly in a clean matrix [1]. | The LCS confirms baseline laboratory performance, separate from matrix-specific issues [1]. |

| Matrix Spike (MS) / Matrix Spike Duplicate (MSD) | Assesses the effect of the sample matrix on method accuracy (MS) and precision (MSD) [2] [1]. | The MS/MSD results show how well the method works for your specific sample type (e.g., soil, water) [2]. |

| Calibration Verification Standard | Confirms that the instrument's calibration remains valid during an analytical run [17]. | It is typically analyzed at the beginning, end, and at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 samples) during a batch [17]. |

Q2: How often should QC samples be analyzed?

The frequency of QC analysis is not arbitrary; it is often governed by regulation, method specification, or project plans.

- Batch-Based Frequency: A common requirement is to analyze QC samples (like method blanks, LCS, and MS/MSD) for each preparation batch or analytical batch of environmental samples [17]. A typical batch size is up to 20 samples [1] [17]. This means one set of QC samples is required for every batch of 20 or fewer samples.

- Regulatory Flexibility: While the "once per 20 samples" frequency is a standard in many EPA programs, the frequency can be adjusted if documented and approved in a project's Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP) based on Data Quality Objectives (DQOs) [2] [1].

Q3: Can a Matrix Spike replace a Laboratory Control Sample?

While a Matrix Spike (MS) can sometimes be used to assess accuracy, it is not a routine replacement for a Laboratory Control Sample (LCS).

The LCS and MS serve different, complementary purposes. The LCS demonstrates that the laboratory can perform the method correctly in a clean matrix, isolating laboratory performance. The MS shows how the sample matrix itself affects the analysis [1]. Regulatory bodies indicate that using an MS in place of an LCS should be an occasional practice, not a routine one, and is only acceptable if the MS recovery meets the stringent acceptance criteria set for the LCS [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating High Pressure in Liquid Chromatography Systems

Unexpectedly high system pressure is a common problem that can have multiple causes.

Systematic Approach:

- Principle: Change only one component at a time and observe the effect. A "shotgun" approach of changing multiple parts simultaneously is inefficient and prevents identification of the root cause [18].

- Procedure: Start from the detector outlet and work upstream toward the pump, removing or replacing one capillary or inline filter at a time. After each change, check if the pressure returns to normal. This systematically localizes the obstructed component [18].

- Root Cause Analysis: Identifying the specific blocked part provides clues. For example, a blocked capillary at the pump outlet may indicate failing pump seals, while a blocked inline filter after the autosampler could point to particulates in the samples [18].

Guide 2: Addressing Failed Calibration Verification

A failed calibration verification standard indicates the instrument's calibration has drifted.

Corrective Actions:

- Immediate Action: Prepare a fresh calibration verification standard and re-analyze it. If it passes, analytical batch processing can continue [17].

- Recalibration: If the freshly prepared standard also fails, a complete initial recalibration of the instrument is required as specified by the analytical method [17].

- Sample Reanalysis: To the extent possible, all environmental samples analyzed since the last acceptable calibration verification should be reanalyzed after a successful recalibration [17].

- Data Flagging: If reanalysis is not possible, the results from the affected batch must be reported with appropriate data qualifiers to inform the data user of potential quality issues [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation and Analysis of a Matrix Spike (MS) and Matrix Spike Duplicate (MSD)

This protocol outlines the steps to assess method accuracy and precision in the specific sample matrix.

Principle: A known amount of analyte is added to two separate portions of a field sample. The recovery of the spike indicates matrix effects on accuracy, while the agreement between the MS and MSD indicates precision [2] [1].

Procedure:

- Sample Selection: Select a representative field sample for spiking.

- Sub-sampling: Obtain two representative sub-samples from the selected field sample [16].

- Spiking:

- Spike both sub-samples with a known concentration of the target analyte(s). The spiking solution should be from a different source or lot than the calibration standards [16].

- The spike level should be significant relative to the native concentration (if known) but must not exceed the calibration range [16].

- Processing: Process the MS and MSD samples through the entire analytical procedure alongside the associated batch of unspiked samples, method blanks, and LCS [17].

- Calculation:

- Calculate the percent recovery for the MS and MSD.

- Calculate the Relative Percent Difference (RPD) between the MS and MSD to assess precision.

Protocol 2: Establishing an Initial Calibration Curve

A valid calibration is the foundation for generating quantitative results.

Principle: The relationship between instrumental response and analyte concentration is established using multiple standard solutions across a defined concentration range [17].

Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of calibration standards at a minimum number of concentrations covering the expected sample concentration range. The number of standards may be method-defined or follow regulations (e.g., a minimum of 3 standards for a range up to 20 times the lowest level) [17].

- Analysis: Analyze the standards to obtain the instrumental response.

- Calibration Model: Establish the calibration curve using a specified model (e.g., linear or nonlinear).

- Acceptance Criteria: Verify that the calibration meets method-specified acceptance criteria. Common criteria include a coefficient of determination (r²) ≥ 0.99 for a linear curve or a relative standard deviation (RSD) of < 20% for response factors [17].

- Initial Calibration Verification: After a successful initial calibration, it must be verified using a standard prepared from a different manufacturer or an independently prepared source to confirm accuracy [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Environmental QC

| Material / Solution | Function in QC |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reagents and Solvents | Used for preparing standards, blanks, and sample processing to minimize background contamination [19]. |

| Primary Standards (NIST-Traceable) | Used to prepare calibration standards and verification standards. Traceability to a national standard ensures accuracy [16]. |

| Independent Source/Lot Standards | Used for Initial Calibration Verification and QC check samples to confirm the accuracy of the primary calibration [16] [17]. |

| Uncontaminated Sample Matrix | A clean matrix (e.g., reagent water, clean sand) free of target analytes, used for preparing Laboratory Control Samples (LCS) and method blanks [16] [17]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common technical and quality control issues encountered in environmental chemistry laboratories, providing clear, actionable solutions to support reliable data generation.

Category 1: Data Quality and QC Failure Investigation

Q1: Our laboratory control sample (LCS) recovery is outside acceptable limits. What are the immediate troubleshooting steps?

A: An out-of-control LCS indicates a potential issue with measurement accuracy. Follow this systematic workflow to identify the root cause [2]:

Experimental Protocol: Immediately initiate a corrective action procedure. First, repeat the analysis of the LCS to rule out a random error. If the problem persists, prepare a fresh calibration standard series and re-calibrate the instrument. Check the age and storage conditions of all reagents and critical consumables (e.g., purge gases, liners). Finally, review the raw data and instrument logs for any anomalies during the analysis sequence [2].

Q2: How do we determine the appropriate frequency for running Internal Quality Control (IQC) samples?

A: IQC frequency is not arbitrary; it should be based on a structured risk assessment. The 2025 IFCC recommendations, aligned with ISO 15189:2022, state that laboratories must consider the method's robustness (e.g., Sigma-metrics), the clinical significance of the analyte, and the feasibility of re-analyzing samples [5]. A risk model, such as Parvin's patient risk model, can be used to quantitatively determine the optimal run size (number of patient samples between IQC events) [5].

Category 2: Instrumentation and Connectivity

Q3: The data acquisition software is unresponsive or has crashed during a run.

A:

- Forced Shutdown: Use the Task Manager (Windows) or Activity Monitor (macOS) to forcibly end the unresponsive program [20].

- Data Integrity Check: Once restarted, check the instrument's data log or sequence file to identify the last successfully processed sample. All samples analyzed after that point must be re-run [21].

- Root Cause Analysis: Update the software to the latest version to fix known bugs. Check for and resolve any conflicts with recently installed software or security updates. Ensure the computer meets the system requirements for memory and processing power [21].

Q4: The instrument computer is running very slowly, delaying data processing.

A: Slow performance often stems from resource constraints or system clutter [20] [21].

- Solution: Close any unnecessary background applications. Use disk cleanup tools to remove temporary files. Ensure all data from completed projects is archived and removed from the local hard drive. Confirm that the computer is free of malware by running an antivirus scan. For instruments requiring high-performance computing, consider a hardware upgrade (e.g., SSD, more RAM) if approved and compatible [21].

Category 3: Access and Security

Q5: A user's account is locked due to multiple failed login attempts to the Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS).

A: Account lockouts are a common security measure [20] [21].

- Solution: Verify the user's identity through a secondary channel (e.g., phone call, email). Reset the password following your organization's security policy. Advise the user to create a strong, unique password. If unauthorized access is suspected, investigate the source of the attempts and ensure two-factor authentication is enabled if available [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are critical for ensuring data quality in environmental chemistry analyses [2].

| Item | Function & Importance in Quality Control |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a metrological traceable standard for calibration and to verify method accuracy. Essential for initial method validation and ongoing verification of measurement system capability [2]. |

| Internal Quality Control (IQC) Materials | A stable, homogeneous material used to monitor the ongoing precision and bias of an analytical method. It verifies that the measurement system remains in control during sample analysis [5]. |

| Calibrators | A series of solutions with known analyte concentrations used to establish the relationship between the instrument's response and the analyte concentration. Critical for generating quantitative results [2]. |

| Matrix Spike/Matrix Spike Duplicate (MS/MSD) Materials | Used to assess method accuracy and precision in the specific sample matrix. Helps identify and quantify matrix effects that can impact measurement accuracy at the levels of concern [2]. |

| Method Blanks | A sample prepared without the analyte of interest but carried through the entire analytical procedure. Used to identify and quantify contamination from reagents, glassware, or the laboratory environment [2]. |

| Surrogate Spikes | A known compound, not normally found in environmental samples, added to every sample prior to extraction. Used to monitor the efficiency of the sample preparation and analytical process for each individual sample [2]. |

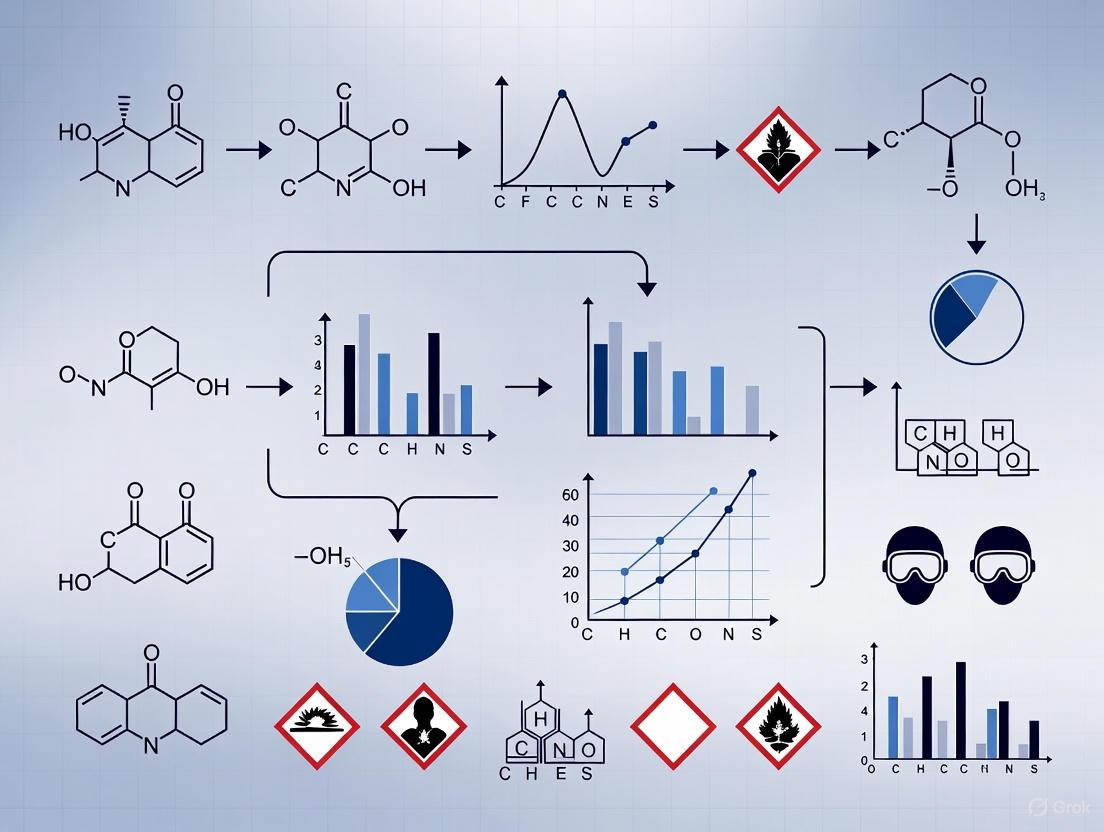

Quality Control Workflow for an Environmental Sample

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for generating reliable analytical data, integrating key QC elements [2] [5].

Implementing Modern QC Methods: From Digital Tools to Sustainable Practices

Troubleshooting Guides

Data Migration and Integrity Issues

Problem: Inconsistent, missing, or corrupted data after migration from legacy systems to a new Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS).

Explanation: Data migration is one of the most technically challenging aspects of LIMS implementation. Legacy laboratory systems store information in various formats, making consolidation complex and time-consuming. Years of historical information stored in spreadsheets, proprietary databases, and paper records must be consolidated and standardized before successful migration [22].

Solution:

- Conduct a Comprehensive Data Audit: Perform thorough analysis of existing data sources to identify quality issues, inconsistencies, and missing information before beginning migration [22].

- Implement Data Standardization Protocols: Establish consistent formats, naming conventions, and validation rules to ensure migrated data meets new LIMS requirements [22].

- Use Phased Migration Strategy: Transfer data in manageable segments rather than attempting bulk migration, allowing for testing and validation at each stage [22].

- Create Backup and Recovery Plan: Implement robust backup procedures to protect against data loss during migration processes and establish rollback capabilities [22].

User Adoption Resistance

Problem: Laboratory staff resist using the new LIMS and revert to familiar paper-based or legacy systems.

Explanation: Laboratory staff comfortable with established workflows naturally resist new processes and technologies. This resistance intensifies when training programs are inadequate or implementation timelines are rushed [22]. Resistance often stems from fear of the unknown, perception of increased workload, or lack of buy-in [23].

Solution:

- Involve Users Early: Include key laboratory personnel in planning processes to gather input, address concerns, and build ownership in the new system [22].

- Develop Role-Specific Training: Create comprehensive training materials and hands-on workshops that prepare users for daily LIMS operations specific to their roles [22] [23].

- Implement Phased Rollout: Introduce LIMS functionality gradually to allow users time to adapt while maintaining operational continuity [22].

- Establish Super-User Network: Identify enthusiastic users who can act as champions within their departments, providing peer support and encouraging adoption [23].

- Provide Ongoing Support: Establish help desk resources and continuous support systems to provide assistance during the transition period and beyond [22].

System Integration Failures

Problem: LIMS fails to properly connect with existing laboratory instruments and software applications, creating data silos and workflow disruptions.

Explanation: Connecting LIMS with existing laboratory instruments and software applications creates complex technical challenges. Compatibility issues between different manufacturers' equipment, communication protocol mismatches, and legacy instrument limitations may prevent seamless data flow and limit automation capabilities [22]. Modern laboratories rely on a diverse ecosystem of software and instruments that must work together [23].

Solution:

- Develop Detailed Integration Plan: Identify all systems requiring integration with LIMS and define data flow between them early in the planning process [23].

- Assess API Capabilities: Thoroughly evaluate the application programming interfaces (APIs) and integration capabilities of the LIMS and other relevant systems [23].

- Use Middleware Platforms: Consider vendor-neutral solutions that translate data formats and manage communication between applications, reducing custom programming requirements [22].

- Conduct Infrastructure Assessment: Evaluate network infrastructure early to identify potential bottlenecks, bandwidth limitations, and upgrade requirements [22].

- Implement Robust Testing: Design comprehensive testing plans that encompass unit tests, system integration checks, and user interface evaluations [23].

Quality Control Compliance Gaps

Problem: Digital workflows fail to maintain required quality control standards and regulatory compliance in environmental chemistry testing.

Explanation: For environmental chemistry laboratories, maintaining quality control (QC) protocols during digital transformation is essential. The EPA emphasizes that having analytical data of appropriate quality requires laboratories to conduct necessary QC to ensure measurement systems are in control and operating correctly, properly document results, and maintain measurement system evaluation records [2].

Solution:

- Implement Electronic QC Tracking: Use LIMS to automate tracking of calibration schedules, control sample analysis, and instrument maintenance [24].

- Maintain Comprehensive Electronic Records: Ensure all QC procedures, including method blanks, matrix spikes, continuing calibration verification, and surrogate spikes are digitally documented with complete metadata [2].

- Establish Automated Alert Systems: Configure LIMS to automatically flag QC results that fall outside acceptance criteria, ensuring immediate corrective action [25].

- Implement Electronic Signatures: Utilize digital signatures for review and approval processes to maintain compliance with ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate) [26].

- Maintain Audit Trails: Ensure system captures complete audit trails tracking all data interactions, modifications, and accesses [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical steps for maintaining quality control during the transition from paper to digital systems?

Environmental chemistry laboratories must maintain several critical QC procedures during digital transition:

- Continue analysis of laboratory control samples, matrix spikes, method blanks, and calibration verification standards as specified in EPA SAM protocols [2]

- Ensure all QC data is properly documented in the new system with appropriate metadata

- Conduct parallel testing where both paper and digital systems are used simultaneously for critical assays

- Validate that digital systems meet EPA data quality objectives (DQOs) before full implementation [2]

- Maintain demonstration of continued analytical method reliability through matrix spike/matrix spike duplicates (MS/MSDs) recovery and precision testing [2]

Q2: How can we ensure our LIMS implementation supports EPA quality control requirements for environmental chemistry?

To ensure LIMS supports EPA QC requirements:

- Configure LIMS to automatically track and alert on QC frequency requirements consistent with EPA's Good Laboratory Practice Standards [2]

- Implement electronic capture of all QC parameters including initial calibration, continuing calibration verification, method blanks, and system suitability tests

- Establish automated calculation of QC statistics and comparison against acceptance criteria

- Ensure system supports documentation of corrective actions when QC results exceed control limits

- Configure user permissions to prevent unauthorized modification of QC data

- Maintain ability to produce comprehensive QC reports for regulatory inspections [2]

Q3: What specific hardware and infrastructure requirements should we plan for when implementing paperless workflows?

Paperless laboratory implementation requires specific infrastructure considerations:

- Reliable high-speed network connectivity with sufficient bandwidth for data transmission [27]

- Adequate power sources and charging stations for mobile devices [27]

- Suitable hardware placements that protect devices from laboratory hazards while maintaining accessibility [27]

- Robust backup power systems to prevent data loss during outages

- Sufficient data storage capacity with automated backup systems

- Cloud-based systems accessibility with reliable internet connections [27]

- Portable devices with protective housings for use in wet laboratory environments [27]

Q4: How do we balance the need for customization with maintaining a supportable, upgradable LIMS?

Balancing customization needs with long-term maintainability requires:

- Conducting detailed requirements gathering and gap analysis before selection [23]

- Prioritizing configuration over customization whenever possible

- Implementing essential customizations first, with non-critical enhancements rolled out in subsequent phases [23]

- Choosing vendors with proven track records in environmental chemistry laboratories [23]

- Establishing a structured change control process to evaluate, approve, and track modifications [23]

- Documenting all customizations thoroughly for future maintenance and upgrades

- Considering middleware solutions for specific instrument integrations rather than core system modifications [22]

Q5: What strategies are most effective for managing scope creep and budget overruns during LIMS implementation?

Effective scope and budget management strategies include:

- Establishing a well-defined project scope at the outset with clear deliverables [23]

- Implementing a formal change control process to evaluate requested modifications [23]

- Prioritizing features and implementing non-critical enhancements in subsequent phases [23]

- Maintaining experienced project management to track progress and communicate with stakeholders [23]

- Budgeting for total cost of ownership, including ongoing maintenance, support, and upgrade costs [28]

- Conducting regular stakeholder reviews to ensure alignment on priorities and timelines

- Building contingency buffers (typically 15-20%) for unexpected challenges

Workflow Visualization

Digital Transformation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Chemistry

Table: Essential materials for environmental chemistry quality control

| Reagent/Material | Function in Quality Control | QC Application |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides known concentration analytes for accuracy verification | Calibration verification, method validation, analyst proficiency testing [2] |

| Matrix Spike Solutions | Evaluates method accuracy in specific sample matrices | Matrix effect determination, recovery rate calculation [2] |

| Laboratory Control Samples | Monitors analytical system performance | Ongoing precision and recovery assessment [2] |

| Method Blanks | Identifies contamination sources | Laboratory contamination monitoring, background subtraction [2] |

| Calibration Standards | Establishes quantitative relationship between response and concentration | Instrument calibration, continuing calibration verification [2] |

| Surrogate Standards | Monitors method performance for individual samples | Extraction efficiency assessment, sample-specific QC [2] |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for analytical variability | Quantification accuracy improvement, instrument performance monitoring [25] |

| Preservation Reagents | Maintains sample integrity between collection and analysis | Analyte stability assurance, holding time requirement compliance [2] |

Intelligent Automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are transforming environmental chemistry laboratories, moving beyond simple automation to create self-optimizing systems that enhance both testing accuracy and operational efficiency. These technologies introduce intelligent decision-making, predictive analytics, and autonomous optimization into research workflows [29]. For quality control protocols in environmental laboratories, this represents a paradigm shift from reactive monitoring to proactive, predictive quality assurance. AI systems continuously analyze data from instruments and processes to identify patterns, predict potential errors, and recommend corrective actions before they compromise data integrity [30]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals implementing these advanced technologies in their experimental work, with a specific focus on troubleshooting common AI-integration issues within the framework of robust quality control.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our AI model for predicting chemical reaction yields performs well on historical data but fails in real-time monitoring. What could be causing this discrepancy?

A1: This is typically a data drift or context mismatch issue. First, verify that the feature set used for real-time predictions exactly matches the training data in terms of units, scaling, and source instruments. Second, implement a data drift detection system to monitor for statistical differences between training and incoming data distributions. Retrain your model periodically with newly acquired data to adapt to process changes. Ensure your real-time data pipeline includes the same pre-processing steps (e.g., outlier removal, smoothing) used during model development [30].

Q2: How can we validate an AI-based anomaly detection system for our environmental sensor network to ensure it meets quality control standards?

A2: Validation requires a multi-faceted approach. Begin by establishing a ground-truth dataset of known anomalies and normal operation periods. Use k-fold cross-validation to assess performance metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) robustly. For quality control, it is critical to test the system's false-positive rate under controlled conditions to ensure it doesn't flag insignificant variations. Document the model's decision boundaries and the feature importance values that drive alerts. Finally, run the AI system in parallel with your existing QC protocols for a predefined period to compare performance against established methods [31] [30].

Q3: Our automated sample preparation system, integrated with an AI scheduler, is causing unexpected bottlenecks. How can we troubleshoot the workflow?

A3: Bottlenecks often arise from unrealistic AI assumptions about task durations or resource conflicts. First, profile the actual time each preparation step takes versus the AI's estimated time. Check for shared resources the scheduler may not account for, such as a centrifuge or balance used by multiple processes. Review the system's log to identify steps with high variability or frequent failures that require manual intervention. Adjust the AI's scheduling parameters to include buffer times for high-variance tasks and ensure it has real-time visibility into equipment availability [32].

Q4: What is the best way to handle missing or incomplete data from environmental sensors when an AI model requires complete input vectors?

A4: Develop a tiered strategy. For minimal missingness (<5%), use imputation methods like k-nearest neighbors or regression-based imputation, but document all imputed values. For significant data gaps, configure your AI system to operate in a "degraded mode" that uses a separate, robust model trained specifically on available variables. Implement data quality checks at the ingestion point to flag missing values for immediate review. For critical quality control parameters, establish rules to halt automated decisions and alert technicians when data completeness falls below a predefined threshold [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results from AI-Driven Analytical Instruments

Problem Identification: Automated analyzers (e.g., GC-MS, ICP-OES) with integrated AI for real-time analysis are producing inconsistent results between runs, despite stable control samples. Symptoms include fluctuating baseline corrections, drift in quantification results, and inconsistent peak identification in chromatographic data [29].

Impact: This inconsistency compromises data integrity for long-term environmental monitoring studies, leads to potential false positives/negatives in contaminant detection, and affects regulatory compliance for quality control protocols.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Quick Diagnostic Check (Time: 5 minutes)

- Verify that all consumables (e.g., lamps, columns, gases) are within their usage lifetime and are properly installed.

- Check for software and AI model version mismatches between the instrument control computer and the central data server.

Standard Resolution (Time: 30 minutes)

- Recalibrate with Certified Reference Materials: Run a full calibration curve using fresh standards to rule out fundamental instrument drift.

- Validate the AI Pre-processing Module: Input a standardized, known data file (e.g., a previous day's run) and check if the AI's output (e.g., baseline correction, peak pick) is identical to the previously validated output. This isolates the AI component from the hardware.

- Review Model Input Data: Check the quality of raw data being fed to the AI model. Look for increased noise, new spectral artifacts, or changes in signal-to-noise ratio that the model was not trained to handle.

- Retrain the Model: If a data drift is identified, retrain the AI model with recent data that reflects the new instrumental conditions, ensuring a representative set of labeled examples is used [30].

Root Cause Fix (Time: Several hours/ days)

- Implement a Continuous Validation Protocol: Set up an automated system that runs a quality control standard every 10 samples. Use the results to continuously monitor the AI's performance and trigger alerts when results deviate from expected ranges.

- Enhance the Training Dataset: Expand the AI model's training dataset to include a wider variety of instrumental conditions and sample matrices, improving its robustness.

- Update Feature Engineering: Re-engineer the input features for the AI model to make them more invariant to the specific types of noise or drift encountered.

Problem: AI-Powered Predictive Maintenance System Generating Excessive False Alarms

Problem Identification: The predictive maintenance AI for laboratory equipment (e.g., HPLC pumps, robotic arms) is generating frequent alerts for impending failures that do not materialize, leading to alert fatigue and unnecessary downtime [29] [30].

Impact: Researchers lose trust in the system, potentially causing them to ignore valid alerts. This results in unnecessary maintenance costs, disrupted experimental schedules, and increased risk of missing a genuine equipment failure.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Immediate Action (Time: 10 minutes)

- Acknowledge and Document: Log each false alarm, noting the equipment, alert type, time, and the actual equipment status. This data is crucial for retraining.

- Temporarily Adjust Thresholds: If the system allows, slightly increase the threshold for the triggering alert to reduce noise, while acknowledging this is a temporary fix.

Standard Resolution (Time: 1-2 hours)

- Conduct Root Cause Analysis: For each recent false alarm, investigate the sensor data that triggered it. Look for patterns, such as specific operational modes (startup/shutdown) or external events (power fluctuations) that correlate with false alerts.

- Review and Relabel Training Data: Examine the historical data used to train the model. It is possible that "normal" operational data was incorrectly labeled as "pre-failure" data.

- Feature Selection Review: Analyze the feature importance scores within your model. It may be relying too heavily on noisy or non-causal sensor readings.

Long-Term Solution (Time: 1 week)

- Retrain with Refined Data: Retrain the predictive maintenance model using a curated dataset that has been corrected based on the root cause analysis. Incorporate the logged false alarm data as negative examples.

- Implement a Hybrid Rule-Based + AI System: Create a pre-filtering layer that uses simple rules to discard impossible alerts (e.g., an alert for a pump failure when it is currently running a method and producing stable pressure).

- Introduce Alert Confidence Scoring: Modify the system to output a confidence score for each alert. Only high-confidence alerts would trigger immediate action, while medium-confidence alerts would generate log entries for later review [30].

Quantitative Data on AI Performance in Chemical and Environmental Applications

The integration of AI and intelligent automation delivers measurable improvements in accuracy and efficiency. The table below summarizes key performance data from industry applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Benefits of AI in Chemical and Environmental Operations

| Application Area | Performance Metric | Improvement with AI | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain Management | Logistics Costs | 15% reduction | [29] |

| Supply Chain Management | Inventory Levels | 35% reduction | [29] |

| Supply Chain Management | Service Levels | 65% improvement | [29] |

| Demand Planning | Forecast Accuracy | 20-30% improvement | [29] |

| Pollution Detection | Monitoring & Intervention | Enables real-time monitoring and prompt intervention | [31] |

| Operational Efficiency | Process Optimization | Significant improvements reported | [29] |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Enhanced Quality Control

Protocol: AI-Assisted Calibration and Drift Monitoring for Analytical Sensors

Objective: To implement an AI-based system for the continuous calibration and performance monitoring of environmental sensors (e.g., for pH, dissolved oxygen, specific contaminants) to ensure data accuracy within quality control limits.

Principle: The protocol uses a suite of software-based AI models to detect subtle changes in sensor behavior that indicate drift or fouling, supplementing traditional manual calibrations and enabling proactive maintenance [31].

Materials:

- Environmental sensors with data logging capabilities

- Centralized data acquisition system (e.g., SCADA, IoT platform)

- Computing environment (e.g., Python, R) with machine learning libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, TensorFlow)

- Certified calibration standards

- Reference analyzer for validation

Procedure:

- Data Collection & Feature Engineering: Stream time-series data from the sensors (e.g., raw mV output, temperature, operational hours). Engineer features such as signal stability, response time to minor fluctuations, and signal-to-noise ratio.

- Baseline Model Training: Under optimal sensor conditions (freshly calibrated, clean), collect a large dataset of normal operation. Train an anomaly detection model (e.g., Isolation Forest, Autoencoder) to learn this "healthy" baseline.

- Model Deployment & Real-Time Monitoring: Deploy the trained model to run inference on live sensor data. The model outputs an "anomaly score" indicating the degree of deviation from the healthy baseline.

- Alerting & Action: Set thresholds on the anomaly score. When a threshold is exceeded, the system automatically alerts personnel, suggesting potential causes (e.g., "drift detected," "possible biofilm formation") based on the feature pattern.

- Validation: When an alert is triggered, validate the sensor's accuracy against a certified standard and a reference analyzer. Record the outcome to refine the AI model.

- Continuous Learning: Periodically retrain the model with new baseline data, especially after any maintenance or changes in the water matrix, to prevent model decay.

Protocol: Automated Anomaly Detection in High-Throughput Screening Data

Objective: To automatically identify and flag anomalous results or potential errors in high-throughput environmental sample analysis (e.g., from GC-MS or HPLC) that may be missed by traditional control limits.

Principle: This protocol uses unsupervised machine learning to model the complex, multi-dimensional relationships between different analytical parameters in a typical run. It flags samples that deviate from the established correlated pattern, indicating potential errors like carryover, matrix interference, or instrument glitches [32].

Materials:

- Data from high-throughput analytical instruments

- Access to a high-performance computing (HPC) environment for rapid data processing

- Data analysis software (e.g., Python/Pandas, R, specialized instrument software)

Procedure:

- Data Compilation: For each analytical batch, compile a data matrix including features like compound retention times, peak areas and shapes, internal standard ratios, and baseline noise levels.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the multi-dimensional data to 2-3 principal components that capture the majority of the variance.

- Clustering: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., DBSCAN) to group samples with similar analytical profiles in the PCA space.

- Anomaly Identification: Identify samples that are outliers from their cluster or that form very small, isolated clusters. These are flagged as potential anomalies.

- Root Cause Investigation: Technicians review the flagged samples, examining raw chromatograms and system logs to determine the root cause (e.g., sample prep error, instrumental artifact).

- Feedback Loop: The findings from the root cause investigation are used to update and refine the anomaly detection model, improving its accuracy over time.

Workflow Visualization

AI for Real-Time Sensor QC

AI-Driven Sensor Quality Control

Automated Anomaly Detection

High-Throughput Screening Anomaly Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential AI Research Reagents

The following "reagents" are the essential software tools and data components required to build and maintain AI systems for an automated environmental lab.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" for AI in the Lab

| Tool/Component | Type | Function | Example in Environmental Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Historical Dataset | Data | Serves as the labeled training material for supervised learning models. | A database of past GC-MS runs, where each chromatogram is tagged with the final verified result and any noted issues. |

| Digital Twin | Software Model | A virtual replica of a physical process (e.g., a reactor, a sensor) used to simulate outcomes and test AI-driven changes safely before real-world implementation [30]. | A dynamic model of a wastewater treatment process that predicts effluent quality under different AI-proposed adjustments. |

| Anomaly Detection Algorithm | Software | An unsupervised learning model that identifies data points that deviate from a learned pattern of "normal" operation. | An Isolation Forest model that flags unusual patterns in real-time sensor data from a river monitoring station, indicating potential contamination events. |

| Predictive Maintenance Model | Software | Uses equipment sensor data to forecast failures before they occur, enabling scheduled maintenance and reducing downtime [29]. | A model that analyzes pressure, temperature, and motor current from an HPLC pump to predict seal failure. |

| Optimization Engine | Software | AI algorithms that continuously adjust process parameters to maximize a defined objective (e.g., yield, purity, energy efficiency) [30]. | A system that dynamically adjusts aeration rates in an activated sludge process to minimize energy use while maintaining treatment efficacy. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

IoT Data Ingestion & Connectivity

Q: The system is not receiving data from IoT sensors. What should I check?

- A: Follow this systematic approach to isolate the issue:

- Verify Sensor Power & Status: Confirm all sensors have power and their operational indicators are on.

- Check Network Connectivity: Use the

iotedge checkcommand to run a collection of configuration and connectivity tests. This will identify issues with the host device's network ports and its ability to connect to the cloud [34]. - Inspect Message Broker Health: If using a broker like Apache Kafka, check the status of the Kafka cluster, brokers, and topic partitions to ensure they are running and accepting messages [35].

- Review Firewall Rules: Ensure necessary outbound ports are open. For protocols like AMQP, port 5671 should be open; for HTTPS, port 443 is typically required [34].

Q: How can I gather logs for technical support?

- A: The most convenient method is to use the

support-bundlecommand. This tool collects module logs, the IoT Edge security manager logs, and the output of theiotedge checkcommand, compressing them into a single file for easy sharing [34].

Data Processing & Analytics

Q: My streaming analytics job is experiencing high latency. What are potential causes?

- A: High latency in stream processing can be investigated by:

- Check Data Freshness (AoI): Monitor the Age of Information (AoI) metric, which quantifies the time elapsed since data generation. A high AoI indicates stale data [35].

- Review Resource Utilization: Check the CPU and memory usage of your stream processing nodes (e.g., Apache Spark workers). Resource saturation can create bottlenecks [35].

- Analyze Backlogs: Investigate if there is a growing backlog of messages in the ingestion layer (e.g., Kafka), which suggests the processing layer cannot keep up with the ingestion rate [35].

Q: Predictive model accuracy has degraded over time. How can I address this?

- A: This is often a case of model drift, where the statistical properties of the real-world data have changed. The solution is to implement a continuous learning pipeline.

- Retrain with New Data: Use a tool like MLflow to manage the machine learning lifecycle. Create a pipeline that automatically retrains models on recently collected data [35].

- Validate Performance: Before deploying the new model, evaluate its performance against a hold-out validation set and compare it to the current model [35].

- Version and Deploy: Use the modular ML pipeline to version the new model and deploy it to replace the underperforming one [35].

Sensor & Equipment Integration

Q: What are common sensor types used for predictive maintenance on laboratory equipment?

- A: Different sensors monitor various failure precursors [36]:

- Vibration Sensors: Essential for rotating equipment like centrifuges to detect imbalances or bearing wear.

- Temperature Sensors: Monitor overheating in instruments such as gas chromatographs or freezers.

- Acoustic (Ultrasound) Sensors: Detect leaks in pressurized systems or changes in noise signatures.

- Voltage/Current Sensors: Track power supply stability and motor current to identify electrical faults.

Q: A centrifuge is vibrating excessively. What are the immediate steps?

- A: This is a potential safety hazard. Follow this protocol:

- Immediately Stop the Run: Safely halt the centrifuge.

- Visual Inspection: Check for an unbalanced load, damaged rotor, or loose components.

- Check Maintenance Logs: Review the equipment's maintenance log for recent servicing, past vibration issues, or calibration records [37] [38].

- Isolate and Report: If the cause is not immediately correctable (like a balanced load), tag the equipment "Out of Service" and report it for corrective maintenance. Data from vibration sensors can be used to diagnose the severity of the issue [37].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Predictive Maintenance Workflow for an Analytical Instrument

Objective: To establish an end-to-end workflow for predicting failures in a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system using IoT and data analytics.

Materials:

- IoT Sensors (Vibration, Temperature, Pressure)

- Industrial IoT Gateway or Edge Device

- Central Cloud Storage & Analytics Platform (e.g., InfluxDB, Spark)

- Machine Learning Platform (e.g., MLflow)

Methodology:

- Sensor Integration: Attach vibration sensors to the HPLC pump and temperature sensors to the column oven. Connect pressure sensors to the fluidic path.

- Data Acquisition & Ingestion: Configure sensors to stream data to an IoT gateway. Use a message broker (e.g., Apache Kafka) for high-throughput, fault-tolerant data ingestion into the cloud [35].

- Stream Processing: Use a stream processing framework (e.g., Apache Spark Structured Streaming) to clean, transform, and aggregate the incoming sensor data in near real-time. Calculate metrics like rolling averages and standard deviations for key parameters [35].

- Feature Engineering & Model Inference: Extract features from the processed data streams (e.g., vibration frequency spectra, pressure trends). Feed these features into a pre-trained machine learning model (e.g., LSTM network) deployed within the pipeline to generate a real-time health score or failure probability [35].

- Alerting & Action: Configure alerts to trigger when the failure probability exceeds a predefined threshold. This alert can automatically create a work order in a CMMS (Computerized Maintenance Management System) for scheduling maintenance [38].

Protocol 2: Real-Time Monitoring of Cold Chain Storage for Environmental Samples

Objective: To ensure the integrity of environmental samples stored in freezers through real-time monitoring and anomaly detection.

Materials:

- Temperature and Humidity Loggers with IoT Connectivity

- Cloud-based Dashboard (e.g., Power BI, Grafana)

- Central Data Storage (Time-series database like InfluxDB)

Methodology:

- Calibration: Calibrate all temperature and humidity sensors against a NIST-traceable standard before deployment.

- Deployment: Place sensors in strategic locations within the freezer (e.g., top, middle, bottom, door).

- Real-Time Data Flow: Sensors transmit data at set intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes) via cellular or wireless networks to a central cloud storage platform [39].

- Anomaly Detection Rule Setup: Configure rules in the analytics platform to detect anomalies, such as:

- Temperature exceeding a setpoint for more than 10 minutes.

- A rapid rate of temperature change indicating a door left ajar or compressor failure.

- Multi-Channel Alerting: Set up alerts to notify lab managers via SMS and email immediately upon anomaly detection, enabling a rapid response to prevent sample loss [40].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key IoT Sensors for Laboratory Predictive Maintenance

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameter | Common Laboratory Application | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibration | Acceleration, Velocity | Centrifuges, HPLC Pumps, Chillers | Time-series |

| Temperature | Degrees Celsius/ Fahrenheit | Incubators, Freezers, Reactors | Time-series |

| Acoustic | Ultrasound, Sound Pressure | Gas Leaks, Bearing Failure | Time-series / Spectral |

| Pressure | PSI, Bar | Liquid Chromatography, Gas Systems | Time-series |

| Humidity | Relative Humidity (%) | Stability Chambers, Sample Storage | Time-series |

Table 2: Recommended Preventive Maintenance Schedule for Key Lab Equipment

| Equipment | Daily/Per Use | Weekly | Quarterly | Annual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Calibration check, Clean pan | - | Professional calibration [37] | - |

| Centrifuge | Inspect for balance, Clean rotor chamber | - | Inspect seals & brushes [37] | Certified speed calibration |

| HPLC System | Purge lines, Performance check | Seal wash | Replace inlet seals, Degas filters | Pump calibration, Detector lamp check |

| -20°C / -80°C Freezer | Visual temperature check | Clean door gasket | Defrost & deep clean | Compressor maintenance |

| fume hood | - | - | - | Face velocity certification |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in IoT/Predictive Maintenance System |

|---|---|

| IoT Sensors | The "eyes and ears" of the system; collect real-time physical data (vibration, temperature) from laboratory equipment [36] [40]. |

| IoT Gateway | Acts as a local communication hub; aggregates data from multiple sensors and transmits it securely to the cloud platform [36]. |

| Message Broker (e.g., Apache Kafka) | Provides a high-throughput, fault-tolerant pipeline for ingesting and buffering massive streams of real-time sensor data [35]. |

| Stream Processing Framework (e.g., Apache Spark) | Performs real-time data transformation, cleansing, and feature extraction on the incoming data streams [35]. |

| Time-Series Database (e.g., InfluxDB) | Optimized for storing and rapidly retrieving the time-stamped data generated by sensors and monitoring systems [35]. |

| Machine Learning Platform (e.g., MLflow) | Manages the end-to-end machine learning lifecycle, from experiment tracking and model training to deployment and monitoring [35]. |

System Architecture & Workflow Diagrams

IoT PdM System Architecture

Predictive Maintenance Data Workflow

Integrating Green and White Analytical Chemistry (GAC/WAC) for Sustainable Method Development

The environmental chemistry laboratory faces a critical challenge: generating precise, reliable data for regulatory compliance and remediation projects while minimizing its own environmental footprint. Traditional analytical methods often involve significant consumption of hazardous solvents and energy-intensive processes. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) addresses this by focusing on reducing environmental impact through principles like waste prevention and safer chemicals. White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents an evolution beyond GAC, integrating environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical/economic feasibility through its RGB model [41]. For laboratories operating under strict quality control protocols like EPA's SAM framework [2], adopting GAC/WAC principles means developing methods that are not only environmentally responsible but also analytically superior and practically viable for routine monitoring and emergency response situations where rapid turnaround is essential [2].

Conceptual Foundations: From GAC to WAC

The RGB Model of White Analytical Chemistry

White Analytical Chemistry employs an RGB (Red, Green, Blue) model to evaluate methods across three dimensions [42] [41]:

- Green Component: Incorporates traditional GAC principles focusing on environmental impact, including solvent toxicity, waste generation, energy consumption, and operator safety [42] [41].

- Red Component: Assesses analytical performance parameters including sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision, linearity, and robustness [42] [41].

- Blue Component: Evaluates practical and economic aspects such as cost, time, ease of use, automation potential, and operational efficiency [42] [41].

A method achieves "whiteness" when it optimally balances all three dimensions, creating sustainable methods without compromising analytical standards or practical implementation [41].

Comparison of Assessment Metrics

Table: Key Metrics for Evaluating Green and White Analytical Methods

| Metric Name | Focus Area | Scoring System | Key Parameters Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [43] [41] | Greenness | 0-1 scale (higher is greener) | 12 principles of GAC |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [41] | Greenness | Penalty points (score >75 = green) | Reagents, toxicity, energy, waste |

| GAPI/ComplexGAPI [41] | Greenness | Pictorial (green to red) | Comprehensive workflow impacts |

| RGB Model [42] [41] | Whiteness | Combined R-G-B score | Environmental, performance, practical aspects |

| BAGI [41] | Applicability | Shades of blue | Practicality in routine application |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I maintain data quality while reducing solvent usage in HPLC methods for water analysis? Data quality can be maintained through method optimization strategies that actually enhance analytical performance while reducing environmental impact. Approaches include using shorter columns (e.g., 50-100 mm instead of 150-250 mm) with smaller particle sizes, which reduce solvent consumption while maintaining or improving resolution [41]. Additionally, replacing toxic solvents like acetonitrile with greener alternatives such as ethanol or methanol in reverse-phase HPLC can improve environmental metrics without compromising separation efficiency [43]. These modifications should be validated through precision, accuracy, and robustness testing per EPA QC requirements [2].

Q2: What are the most practical green sample preparation techniques for endocrine disruptor analysis in aqueous matrices? For endocrine disruptor analysis in water, practical green techniques include in-situ sampling approaches that eliminate the need for sample transport, and miniaturized solid-phase extraction (SPE) methods that significantly reduce solvent consumption compared to traditional off-line SPE [44]. Fabric phase sorptive extraction (FPSE) and capsule phase microextraction (CPME) have shown particular promise for concentrating analytes while using minimal organic solvents [41]. These techniques maintain the sensitivity required for detecting trace-level contaminants while aligning with GAC principles.

Q3: How does the WAC framework specifically benefit quality control laboratories? WAC benefits QC laboratories by providing a holistic assessment that balances sustainability with the practical demands of high-throughput environments. The framework ensures methods are not only environmentally responsible but also cost-effective, time-efficient, and robust enough for routine application [43]. This integrated approach helps laboratories meet both their sustainability goals and regulatory data quality requirements [2] [43], supporting the selection of methods that excel across all three RGB dimensions rather than just environmental metrics alone.

Q4: Can I apply GAC/WAC principles to existing EPA-approved methods without compromising data quality? Yes, existing methods can be optimized for greenness and whiteness while maintaining data quality through systematic modification and re-validation. Key strategies include scaling down sample volumes, replacing hazardous reagents with safer alternatives, implementing energy-efficient instrumentation, and incorporating automated or on-line sample preparation [44] [41]. Any modifications must be thoroughly validated through precision and recovery studies, with QC samples analyzed to verify measurement system accuracy at levels of concern, as specified in EPA guidelines [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Recovery in Green Sample Preparation

Table: Troubleshooting Poor Recovery in Miniaturized Sample Preparation

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | QC Verification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low recovery in micro-SPE | Insufficient sample volume or flow rate | Optimize sample loading conditions; use smaller sorbent amounts | Analyze matrix spikes at level of concern [2] |

| Incomplete extraction in FPSE | Inadequate extraction time or solvent volume | Increase extraction time; optimize elution solvent volume | Verify with laboratory control samples [41] |

| Matrix effects in direct injection | High dissolved organic content | Implement dilute-and-shoot with minimal dilution factor | Use matrix spike duplicates to assess precision [2] [41] |

| Inconsistent recovery across samples | Sorbent bed channeling in miniaturized devices | Ensure proper packing; use homogeneous sorbent materials | Document corrective actions per Good Laboratory Practice [2] |

High Solvent Consumption in HPLC Analysis

Problem: Method fails green metrics due to excessive mobile phase usage.