Random Forest vs. XGBoost: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Water Quality Prediction

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two powerful ensemble learning algorithms, Random Forest and XGBoost, for predicting water quality indices and parameters.

Random Forest vs. XGBoost: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Water Quality Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two powerful ensemble learning algorithms, Random Forest and XGBoost, for predicting water quality indices and parameters. Tailored for researchers, environmental scientists, and data professionals, it explores foundational principles, methodological applications for various water types (surface, ground, and wastewater), and advanced optimization techniques for handling real-world challenges like class imbalance and overfitting. Through rigorous validation metrics and case studies, including recent research achieving up to 99% accuracy, we delineate the specific scenarios where each algorithm excels. The analysis concludes with synthesized practical guidelines for model selection and future directions at the intersection of hydroinformatics and machine learning.

Understanding the Core Algorithms: Bagging vs. Boosting for Environmental Data

The degradation of water quality, driven by rapid urbanization, industrial discharge, and agricultural runoff, poses significant threats to public health, aquatic ecosystems, and water resource sustainability [1] [2]. Accurate forecasting of the Water Quality Index (WQI)—a singular value that simplifies complex water quality data—is therefore critical for proactive environmental management and policy formulation [3]. Traditional methods of water quality assessment, often reliant on manual laboratory analyses, are typically slow, resource-intensive, and ill-suited for real-time monitoring [1] [3].

In response to these challenges, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool for processing complex environmental datasets and generating precise, timely predictions [1] [4]. Among the most powerful ML approaches are ensemble methods, which combine multiple base models to achieve superior performance and robustness. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two dominant ensemble learning paradigms—Bagging, represented by Random Forest (RF), and Boosting, represented by eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—within the context of water quality prediction. We objectively evaluate their performance using recent experimental data, detail foundational methodologies, and provide a practical toolkit for researchers and water resource professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Mechanisms

Ensemble learning enhances predictive accuracy and stability by leveraging the "wisdom of crowds," combining multiple weak learners to form a single, strong learner. The core difference between Bagging and Boosting lies in how they build and combine these base models.

Random Forest: Parallelized Bootstrap Aggregating

Random Forest (RF) is a premier example of the Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) technique. Its operational mechanism is designed to reduce model variance and mitigate overfitting.

- Bootstrap Sampling: A RF model constructs multiple Decision Trees (DTs). Each tree is trained on a different random subset of the original training data, drawn with replacement (a bootstrap sample). This introduces variability between the trees.

- Feature Randomness: When splitting a node during the construction of a tree, the algorithm is restricted to a random subset of features. This further decorrelates the individual trees.

- Aggregation: For a regression task like predicting a continuous WQI value, the final output is the average of the predictions from all individual trees. For classification, it is the majority vote [1] [5].

This parallel, independent construction of trees makes RF inherently robust to noise and outliers in water quality datasets.

XGBoost: Sequential Gradient Boosting

XGBoost is an advanced implementation of the Boosting paradigm, renowned for its execution speed and predictive power. Unlike Bagging, Boosting builds models sequentially, with each new model focusing on the errors of its predecessors.

- Sequential Model Building: Trees are built one after another. Each new tree aims to correct the residual errors of the combined existing ensemble of trees.

- Gradient Descent: The model optimizes a specified loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error for WQI prediction) using gradient descent. It calculates the gradients (direction of the steepest ascent) of the loss function and then builds a new tree that predicts the negative gradients (steepest descent), thereby reducing the error.

- Regularization: A key feature distinguishing XGBoost from other boosting algorithms is its inclusion of regularization terms (L1 and L2) in the objective function it seeks to minimize. This penalty for model complexity helps control overfitting, leading to better generalization on unseen water quality data [6] [7].

- Weighted Summation: The final prediction is a weighted sum of the predictions from all the trees, where trees that contribute more to error reduction are typically assigned higher weights.

The following diagram illustrates the core sequential error-correction workflow of XGBoost.

Performance Comparison in Water Quality Prediction

Empirical studies directly comparing RF and XGBoost for water quality prediction reveal a nuanced picture of their respective strengths. The performance can vary based on the specific task (classification vs. regression), data characteristics, and model implementation.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RF and XGBoost in Water Quality Studies

| Study Context | Key Performance Metrics | Random Forest (RF) | XGBoost (XGB) | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WQI Regression [3] | R² (Coefficient of Determination) | -- | 0.9894 (as standalone) | CatBoost (0.9894 R²) & Gradient Boosting (0.9907 R²) were top standalone models; a stacked ensemble (incl. RF & XGB) achieved best performance (0.9952 R²). |

| WQI Regression [3] | RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | -- | 1.5905 (as standalone) | Lower RMSE is better. The stacked ensemble achieved the lowest RMSE (1.0704). |

| WQI Classification [7] | Accuracy (%) | -- | 97% for river sites | XGBoost demonstrated "superior performance" and "excellent scoring" with a logarithmic loss of 0.12. |

| Water Quality Classification [8] | Accuracy & F1-Score | -- | High performance, but slightly lower than CatBoost | In a comparison of XGBoost, CatBoost, and LGBoost, CatBoost showed the highest overall accuracy, though XGBoost was competitive. |

| General Application Review [6] | Versatility & Robustness | Effective for various tasks (e.g., hydrological modeling) | Effective for various tasks (e.g., hydrological modeling); did not outperform others in all cases. | Both are versatile, but neither is universally superior. Performance is case-specific. |

Synthesis of Comparative Findings:

- Predictive Accuracy: XGBoost frequently demonstrates a slight edge in predictive accuracy for both regression and classification tasks related to water quality, as evidenced by high R² scores and classification accuracy [3] [7]. Its sequential, error-correcting approach often allows it to capture complex, non-linear patterns in physicochemical data more effectively than the parallel approach of RF.

- Robustness and Stability: Random Forest is generally more robust to noisy data and outliers, a common issue in environmental datasets, due to its bootstrap sampling and feature randomness [1]. It is less prone to overfitting without the need for extensive hyperparameter tuning.

- Performance in Ensembles: Both algorithms are highly valued as base learners in more complex ensemble frameworks. A stacked ensemble that combined XGBoost, RF, and other models achieved state-of-the-art performance (R² = 0.9952, RMSE = 1.0704), underscoring that their strengths can be complementary rather than mutually exclusive [3].

Experimental Protocols and Model Implementation

Implementing RF and XGBoost for water quality prediction follows a structured workflow. The following diagram and subsequent sections detail this process from data preparation to model deployment.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundation of any robust model is high-quality data. Water quality datasets are typically sourced from public repositories (e.g., Kaggle), government monitoring agencies, or IoT sensor networks [3] [2].

Common Preprocessing Steps:

- Data Cleaning: Handling missing values using techniques like median imputation [3].

- Outlier Treatment: Identifying and mitigating outliers using methods like the Interquartile Range (IQR) to prevent model skew [3].

- Data Normalization/Standardization: Scaling features (e.g., pH, conductivity, nutrient levels) to a common range to ensure that models converge effectively and no single parameter dominates due to its scale.

Feature Analysis and Selection

Understanding the influence of different water quality parameters is crucial. SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations), an Explainable AI (XAI) technique, is widely used to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model's prediction [3].

Key Influential Parameters: Studies consistently identify Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), pH, and conductivity as among the most influential features for WQI prediction [3]. Techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with XGBoost can be employed to select the most critical indicators, thereby reducing dimensionality and model complexity [7].

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

Both RF and XGBoost have hyperparameters that require optimization for peak performance. This is typically done via cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold CV) and search strategies like random or Bayesian search [3] [9].

Table 2: Essential Hyperparameters for Random Forest and XGBoost

| Algorithm | Critical Hyperparameters | Function and Tuning Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | n_estimators |

Number of trees in the forest. Higher values generally improve performance but increase computational cost. |

max_depth |

The maximum depth of each tree. Controls model complexity; limiting depth helps prevent overfitting. | |

max_features |

The number of features to consider for the best split. A key lever for controlling tree decorrelation. | |

| XGBoost | n_estimators |

Number of boosting rounds (trees). |

learning_rate (eta) |

Shrinks the contribution of each tree. A lower rate often leads to better generalization but requires more trees. | |

max_depth |

The maximum depth of a tree. Increasing depth makes the model more complex and prone to overfitting. | |

subsample |

The fraction of samples used for training each tree. Prevents overfitting. | |

colsample_bytree |

The fraction of features used for training each tree. Similar to max_features in RF. |

|

reg_alpha, reg_lambda |

L1 and L2 regularization terms on weights. Core features that help control overfitting. |

This section outlines the key computational tools and data resources essential for conducting water quality prediction research with ensemble models.

Table 3: Key Resources for Water Quality Prediction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Languages & Libraries | Python (scikit-learn, XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM), R | Provide the core programming environment and implementations of ML algorithms like RF and XGBoost. |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [3] | Explains model output by quantifying the contribution of each input feature, moving beyond the "black box" nature of complex ensembles. |

| Data Acquisition Sources | Kaggle Datasets [3], Government Agency Data (e.g., Malaysia DOE [2]), IoT Sensor Networks [2] | Provide the foundational water quality data (parameters like pH, DO, BOD, etc.) for training and validating models. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Tools | Keras Tuner, Random Parameter Search [9] | Automate the process of finding the optimal hyperparameter configuration for a model, saving time and improving performance. |

| Hybrid Model Components | Attention Mechanisms [9], LSTM Networks [1] [9] | Can be integrated with RF/XGBoost to handle temporal dependencies or to weight important time steps in sequential water quality data. |

Both Random Forest and XGBoost are powerful ensemble methods that have proven highly effective for water quality prediction. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more suitable for a specific research context.

- Choose Random Forest when you prioritize a model that is robust, less prone to overfitting, and easier and faster to train with good default parameters. It is an excellent choice for initial prototyping and for datasets with significant noise.

- Choose XGBoost when the primary goal is maximizing predictive accuracy for a well-defined problem and computational resources are available for rigorous hyperparameter tuning. Its regularization capabilities and sequential learning often give it a slight performance advantage.

The future of water quality modeling lies not only in selecting a single algorithm but also in leveraging their strengths within hybrid and stacked ensemble frameworks [3] [9]. Integrating these models with Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP will be crucial for building transparent, trustworthy tools that can inform environmental policy and sustainable water management practices effectively.

In the domain of water quality prediction, the selection of a robust machine learning algorithm is paramount for generating reliable data that supports environmental policy and public health decisions. Among the most prominent ensemble methods employed, Random Forest and XGBoost have emerged as leading contenders. While both are powerful techniques, their underlying mechanisms differ substantially, leading to distinct performance characteristics in practical applications. Random Forest leverages bootstrap aggregating (bagging) to enhance model stability and reduce variance, while XGBoost utilizes gradient boosting to sequentially minimize errors. Understanding these fundamental differences enables researchers to select the most appropriate algorithm based on their specific dataset characteristics and prediction requirements. Recent comparative studies in hydrological sciences have demonstrated that the choice between these algorithms can significantly impact the accuracy and reliability of water quality assessments, making this comparison particularly relevant for researchers and environmental professionals [7] [10].

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these two algorithms within the context of water quality prediction, examining their theoretical foundations, implementation methodologies, and empirical performance. By deconstructing the Random Forest algorithm with a specific focus on how bootstrap aggregating contributes to its robustness, we aim to provide researchers with actionable insights for algorithm selection in environmental monitoring applications.

Theoretical Foundations: Bagging vs. Boosting

Random Forest: The Power of Bootstrap Aggregating

Random Forest operates on the principle of bootstrap aggregating (bagging), a technique designed to reduce variance in high-variance estimators like decision trees. The algorithm creates multiple decision trees, each trained on a different bootstrap sample of the original dataset—a random sample drawn with replacement. This approach ensures that each tree in the ensemble sees a slightly different version of the training data, introducing diversity among the trees [10] [11].

The robustness of Random Forest stems from two key mechanisms:

- Bootstrap Sampling: Each tree is trained on a dataset drawn with replacement from the original data, which repeats some instances and omits others by chance. The omitted instances form "out-of-bag" samples that provide an internal validation mechanism [10] [11].

- Random Feature Subsets: At each split in the tree growth process, the algorithm considers only a random subset of the available features rather than the complete feature set. This prevents strong predictive features from dominating the splitting process across all trees, thereby decorrelating the individual trees and enhancing the ensemble's predictive power [11].

The final prediction is determined through averaging (for regression) or majority voting (for classification) across all trees in the forest. This aggregation process smooths out extreme predictions from individual trees, resulting in a more stable and reliable model [10].

XGBoost: Sequential Error Correction

In contrast to Random Forest's parallel approach, XGBoost employs a sequential boosting methodology where trees are grown one after another, with each subsequent tree focusing on the errors made by previous trees. The algorithm works by iteratively fitting new trees to the residual errors of the current ensemble, effectively learning from its mistakes in a gradual, additive fashion [10].

Key characteristics of XGBoost include:

- Sequential Tree Building: Each new tree is trained to predict the residuals (errors) of the combined previous trees, slowly improving the model's performance in poorly predicted regions of the feature space [10].

- Gradient Optimization: XGBoost uses gradient information to minimize a loss function more efficiently, making it highly effective at capturing complex patterns in data [7].

- Regularization: The algorithm incorporates regularization terms in its objective function to control model complexity and prevent overfitting, often giving it an edge in performance on structured datasets [10].

This fundamental difference in approach—parallel bagging versus sequential boosting—leads to distinct performance characteristics that become particularly evident in water quality prediction tasks.

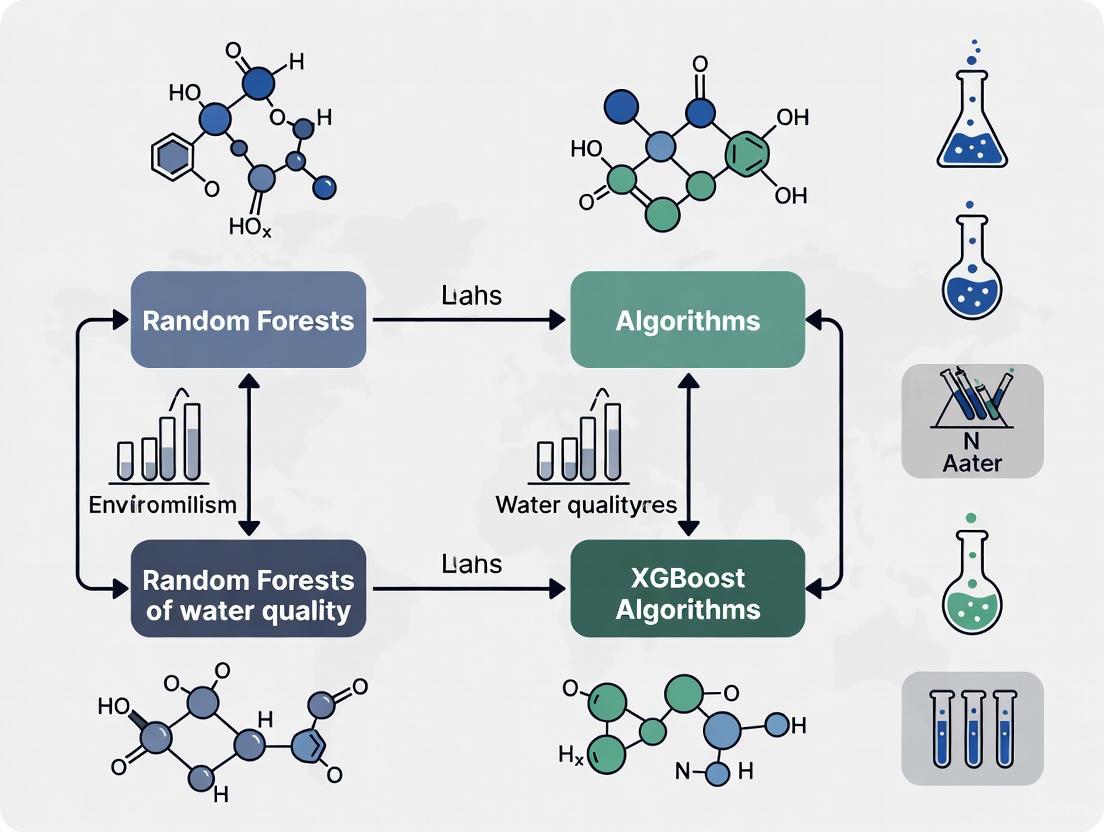

Diagram 1: Algorithmic workflows of Random Forest (bagging) and XGBoost (boosting) approaches.

Experimental Comparison in Water Quality Prediction

Performance Metrics and Experimental Setups

Recent research has provided empirical comparisons of Random Forest and XGBoost in various water quality prediction scenarios. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from several studies:

Table 1: Comparative performance of Random Forest and XGBoost in water quality prediction tasks

| Study Context | Prediction Task | Random Forest Performance | XGBoost Performance | Key Observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riverine Water Quality Classification | WQI scoring for rivers | 92% accuracy | 97% accuracy (Log Loss: 0.12) | XGBoost showed superior prediction error and classification accuracy | [7] |

| Water Potability Prediction | Binary classification of water safety | Accuracy: 62-68% range | Accuracy: 62-68% range | Comparable performance in baseline conditions | [12] |

| Model Stability Under Noise | Performance with noisy/missing data | More stable with minor performance degradation | Higher performance degradation | RF's bagging approach provides better noise tolerance | [11] |

| Feature Importance Interpretation | Identification of key water quality parameters | Consistent feature rankings | Slightly varied feature rankings | Both identified TP, permanganate index, ammonia nitrogen as key river indicators | [7] |

Methodological Protocols in Water Quality Studies

The experimental protocols employed in comparative studies typically follow rigorous methodology to ensure fair evaluation:

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Studies analyzing water quality typically employ datasets containing multiple physicochemical parameters such as pH, hardness, total dissolved solids (TDS), chloramines, sulfate, conductivity, organic carbon, trihalomethanes, and turbidity [12]. For instance, one comprehensive study utilized six years of monthly data (2017-2022) from 31 monitoring sites in the Danjiangkou Reservoir system, incorporating temporal and spatial variations in water quality measurements [7].

Feature Selection and Engineering: Researchers often employ recursive feature elimination (RFE) combined with machine learning algorithms to identify the most critical water quality indicators. In riverine systems, key parameters typically include total phosphorus (TP), permanganate index, and ammonia nitrogen, while reservoir systems may prioritize TP and water temperature [7]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) have been shown to significantly enhance model performance, with one study reporting accuracy improvements to nearly 100% after PCA application [12].

Model Training and Validation: Experimental protocols generally involve stratified data splitting, typically allocating 75% of samples for training and 25% for testing [12]. To ensure robust performance evaluation, researchers employ k-fold cross-validation and out-of-bag error estimation (particularly for Random Forest). Hyperparameter optimization is conducted for both algorithms, with Random Forest focusing on parameters like tree depth, minimum samples per leaf, and number of trees, while XGBoost requires tuning of learning rate, maximum depth, and regularization terms [7] [11].

Table 2: Hyperparameter optimization focus for each algorithm

| Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|

| n_estimators (number of trees) | n_estimators (number of boosting rounds) |

| max_depth (tree depth control) | max_depth (tree complexity) |

| minsamplessplit (split constraint) | learning_rate (shrinkage factor) |

| minsamplesleaf (leaf size constraint) | reg_lambda (L2 regularization) |

| max_features (feature subset size) | reg_alpha (L1 regularization) |

| bootstrap (bootstrap sampling) | subsample (instance sampling ratio) |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Implementations

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for water quality prediction studies

| Tool/Technique | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Identifies most critical water quality parameters | Combined with XGBoost to select key indicators like TP, permanganate index [7] |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Reduces dimensionality while preserving variance | Increased classifier accuracy to nearly 100% in potability prediction [12] |

| Bootstrap Sampling | Creates diverse training subsets for ensemble diversity | Fundamental to Random Forest's robustness; enables out-of-bag validation [10] [11] |

| Cross-Validation | Provides robust performance estimation | Stratified k-fold validation prevents optimistic performance estimates [11] |

| Permutation Importance | Evaluates feature significance without bias | More reliable than impurity-based importance in Random Forest [11] |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Captures temporal patterns in water quality data | Useful for time-series prediction of parameters like DO and CODMn [13] |

Analysis of Robustness Factors in Water Quality Prediction

Variance Reduction Through Bootstrap Aggregating

The bootstrap aggregating mechanism inherent to Random Forest provides distinct advantages in handling the variability often present in environmental datasets. By creating multiple diverse models through bagging and random feature selection, Random Forest effectively reduces variance without increasing bias—a crucial characteristic for water quality prediction where measurement noise and natural fluctuations are common [10].

This variance reduction capability makes Random Forest particularly suitable for scenarios with:

- High-frequency monitoring data with substantial measurement noise

- Missing or incomplete records common in long-term environmental datasets

- Heterogeneous water sources with different pollution profiles

- Seasonal variations that create non-stationary patterns in parameters

The decorrelation of trees achieved through random feature selection prevents the model from being dominated by strong seasonal predictors, allowing it to maintain performance across varying hydrological conditions [11].

Handling of Data Limitations and Noise

Water quality datasets often present challenges such as missing values, measurement errors, and imbalances—issues that differently impact Random Forest and XGBoost. Random Forest's bagging approach naturally handles these challenges through its inherent design:

Diagram 2: Comparative responses of Random Forest and XGBoost to common water quality data challenges.

Computational and Practical Considerations

From an implementation perspective, several factors influence the choice between Random Forest and XGBoost in research settings:

Training Parallelization: Random Forest's independent tree construction allows for straightforward parallelization, significantly reducing training time on multi-core systems. This advantage becomes particularly valuable when working with large-scale water quality datasets spanning multiple years and monitoring stations [11].

Hyperparameter Sensitivity: Random Forest typically delivers strong performance with minimal hyperparameter tuning, making it accessible for researchers without extensive machine learning expertise. In contrast, XGBoost often requires more careful parameter optimization to achieve peak performance, particularly regarding learning rate and regularization terms [11].

Interpretability and Feature Analysis: Both algorithms provide feature importance metrics, though through different mechanisms. Random Forest typically uses mean decrease in impurity or permutation importance, while XGBoost employs gain, cover, and frequency metrics. For environmental researchers seeking to identify key water quality parameters, both approaches have proven effective, with studies consistently identifying total phosphorus, ammonia nitrogen, and permanganate index as critical factors across different algorithmic approaches [7].

The comparative analysis reveals that neither algorithm universally dominates across all water quality prediction scenarios. Rather, the optimal choice depends on specific research objectives and dataset characteristics:

Select Random Forest when:

- Working with noisy or incomplete environmental datasets

- Model stability and reduced variance are prioritized

- Seeking straightforward implementation with minimal hyperparameter tuning

- Interpretation of feature importance is crucial for identifying pollution sources

- Computational efficiency through parallelization is desired

Prefer XGBoost when:

- Maximizing prediction accuracy is the primary objective

- Working with cleaner, well-curated datasets

- Computational resources allow for extensive hyperparameter optimization

- Capturing complex nonlinear relationships in water parameters is essential

- Sequential dependencies in time-series water quality data exist

The remarkable performance of XGBoost in achieving 97% accuracy in riverine water quality classification demonstrates its predictive power under optimal conditions [7]. However, Random Forest's robustness through bootstrap aggregating makes it particularly valuable for real-world environmental monitoring where data quality varies and reliability is paramount. As water quality prediction continues to evolve, understanding these fundamental algorithmic differences enables researchers to make informed decisions that align with their specific research constraints and objectives.

In the domain of machine learning, ensemble learning methods combine multiple models to produce a single, superior predictive model. Two prominent ensemble techniques are bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) and boosting. Bagging, exemplified by the Random Forest algorithm, involves training multiple decision trees in parallel on different subsets of the data and averaging their predictions to reduce variance. In contrast, boosting is a sequential technique where each new model is trained to correct the errors of its predecessors, resulting in a strong learner from multiple weak learners [14]. XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is an advanced implementation of the gradient boosting framework that has become the go-to algorithm for many machine learning tasks, including water quality prediction, due to its computational efficiency, high performance, and handling of complex data relationships [14] [15].

The fundamental principle behind XGBoost and all gradient boosting variants is sequential model correction. The algorithm builds an ensemble of trees one at a time, where each new tree helps to correct the residual errors made by the collection of existing trees [14] [16]. This sequential learning process, combined with sophisticated regularization techniques, enables XGBoost to achieve state-of-the-art results across diverse domains, from environmental science to healthcare.

The Mechanical Anatomy of XGBoost

Sequential Learning and Residual Correction

XGBoost operates through an iterative process of building an ensemble of decision trees. The algorithm begins with an initial prediction, which for regression tasks is often the mean of the target variable [15]. It then proceeds through the following steps:

- Residual Calculation: After the initial prediction, the algorithm computes the residuals (differences between observed and predicted values) for each data point [14] [16].

- Sequential Tree Building: A decision tree is trained to predict these residuals, learning patterns in the errors of the previous model [16].

- Model Update: Predictions from this new tree are added to the previous predictions, with their contribution scaled by a learning rate to prevent overfitting [16] [15].

- Iterative Refinement: This process repeats for a specified number of iterations or until residuals are minimized [14].

Mathematically, this process can be represented as:

Let $F_0(x)$ be the initial prediction. For $m = 1$ to $M$ (where $M$ is the total number of trees):

- Compute residuals: $r{im} = -\frac{\partial L(yi, F{m-1}(xi))}{\partial F{m-1}(xi)}$ for $i = 1, 2, ..., n$

- Fit a new tree $h_m(x)$ to the residuals

- Update the model: $Fm(x) = F{m-1}(x) + \eta \cdot h_m(x)$

Where $\eta$ is the learning rate that controls the contribution of each tree [14] [15].

The XGBoost Advantage: Enhancements Over Standard Gradient Boosting

XGBoost incorporates several key innovations that distinguish it from traditional gradient boosting:

Regularization: XGBoost includes L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization terms in its objective function to prevent overfitting. The regularization term penalizes complex trees, encouraging simpler models that generalize better [14] [15]. The objective function is: $obj(\theta) = \sum{i}^{n} l(y{i}, \hat{y}{i}) + \sum{k=1}^K \Omega(f{k})$ where $\Omega(f{k}) = \gamma T + \frac{1}{2}\lambda \sum{j=1}^T wj^2$ [15].

Handling Missing Data: XGBoost uses a sparsity-aware split finding algorithm that automatically handles missing values by learning default directions for instances with missing features [15].

Tree Structure: Unlike traditional gradient boosting that may use depth-first approaches, XGBoost builds trees level-wise (breadth-first), evaluating all possible splits for each feature at each level before proceeding to the next depth [15].

Computational Efficiency: Through features like block structure for parallel learning, cache-aware access, and approximate greedy algorithms, XGBoost achieves significant speed improvements over traditional gradient boosting [14] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential tree building process in XGBoost:

Comparative Analysis: XGBoost vs. Random Forest in Water Quality Prediction

Algorithmic Differences and Theoretical Strengths

While both XGBoost and Random Forest are ensemble methods based on decision trees, their fundamental approaches differ significantly. Random Forest employs bagging, which builds trees independently in parallel, while XGBoost uses boosting, constructing trees sequentially with each tree correcting its predecessor [14]. This distinction leads to several theoretical advantages for XGBoost in handling the complex, nonlinear relationships often found in water quality data:

Bias-Variance Tradeoff: Random Forest primarily reduces variance by averaging multiple deep trees trained on different data subsets. XGBoost sequentially reduces both bias and variance by focusing on difficult-to-predict instances [14].

Feature Relationships: XGBoost's sequential approach more effectively captures complex feature interactions and temporal dependencies in water quality parameters [17].

Data Efficiency: XGBoost typically requires fewer trees than Random Forest to achieve similar performance due to its targeted error correction approach [14].

Experimental Performance Comparison in Water Quality Research

Recent studies in hydrological sciences provide compelling empirical evidence comparing XGBoost and Random Forest for water quality prediction tasks. The table below summarizes key findings from multiple research initiatives:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of XGBoost vs. Random Forest in Water Quality Prediction

| Study & Context | Key Performance Metrics | Algorithm Performance | Interpretability Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Six-year riverine and reservoir study (Danjiangkou Reservoir) [7] | Accuracy, Logarithmic Loss | XGBoost: 97% accuracy, 0.12 log lossRandom Forest: 92% accuracy | Feature importance analysis identified TP, permanganate index, NH₃-N as key indicators |

| Indian river water quality prediction (1,987 samples) [3] | R², RMSE, MAE | Stacked ensemble with XGBoost: R²=0.9952, RMSE=1.0704Random Forest: Lower performance than ensemble | SHAP analysis identified DO, BOD, conductivity, pH as most influential |

| Pulp and paper wastewater treatment [17] | Prediction accuracy for BOD, COD, SS | XGBoost-based hybrid models (LSTMAE-XGBOOST) outperformed Random Forest | LSTM Autoencoder for temporal feature extraction combined with XGBoost |

| Tai Lake Basin water quality analysis [18] | Feature importance ranking | XGBoost with SHAP identified DO, TP, CODₘₙ, NH₃-N as primary determinants | Seasonal SHAP analysis revealed varying feature importance across seasons |

The experimental protocols across these studies followed rigorous methodologies. Data collection typically involved regular sampling of water quality parameters including total phosphorus (TP), dissolved oxygen (DO), biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia nitrogen (NH₃-N), and other physicochemical parameters [7] [18]. Studies employed k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold) to ensure robust performance estimation and prevent overfitting [3]. Data preprocessing included handling missing values, outlier detection using methods like Interquartile Range, and normalization [3]. Model evaluation utilized multiple metrics including R-squared, Root Mean Square Error, Mean Absolute Error, and accuracy for classification tasks [7] [3].

Advanced Applications and Interpretability in Water Research

Hybrid Modeling Approaches for Enhanced Performance

Recent research has explored hybrid models that combine XGBoost with other techniques to address specific challenges in water quality prediction:

Temporal Feature Extraction: The integration of Long Short-Term Memory Autoencoders with XGBoost creates models capable of capturing both temporal patterns and complex nonlinear relationships in wastewater treatment data [17].

Explainable AI Integration: Combining XGBoost with SHAP provides both high predictive accuracy and interpretability, essential for environmental decision-making [19] [18] [3].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a typical hybrid modeling approach for water quality prediction:

The Researcher's Toolkit for XGBoost in Water Quality Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for XGBoost Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Libraries | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core ML Libraries | XGBoost (Python/R), Scikit-learn, CatBoost | Implementation of gradient boosting algorithms, data preprocessing, model evaluation | Model development and training [16] [3] |

| Interpretability Frameworks | SHAP, Lime, ELI5 | Model interpretation, feature importance analysis, result visualization | Explaining model predictions and identifying key water quality parameters [19] [18] [3] |

| Deep Learning Integration | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Implementation of LSTM autoencoders and neural network components for hybrid models | Temporal pattern recognition in water quality data [17] |

| Data Processing & Analysis | Pandas, NumPy, SciPy | Data manipulation, statistical analysis, feature engineering | Data preprocessing and exploratory data analysis [3] |

| Visualization Tools | Matplotlib, Seaborn, Plotly | Result visualization, performance metric plotting, SHAP summary plots | Communicating findings and model performance [18] |

The comparative analysis between XGBoost and Random Forest demonstrates XGBoost's superior performance in water quality prediction tasks across diverse aquatic environments. The algorithm's sequential correction mechanism, combined with its regularization capabilities and computational efficiency, makes it particularly well-suited for capturing the complex, nonlinear relationships inherent in water quality parameters.

For researchers and environmental scientists, XGBoost offers not only enhanced predictive accuracy but also, when combined with interpretability frameworks like SHAP, valuable insights into the key factors driving water quality changes. The integration of XGBoost with temporal modeling approaches and the development of hybrid frameworks represent promising directions for advancing predictive capabilities in water resource management. As computational tools continue to evolve, XGBoost remains a cornerstone algorithm for tackling the complex challenges of water quality prediction and environmental monitoring.

Within the field of machine learning applied to environmental science, tree-based ensemble methods like Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) are cornerstone algorithms for critical prediction tasks such as water quality assessment. Their performance hinges on a fundamental architectural choice: how individual trees within the ensemble are constructed. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the parallel tree building approach of Random Forest versus the sequential tree building method of XGBoost, contextualized within water quality prediction research. We will summarize quantitative performance data, detail experimental protocols from recent studies, and visualize the underlying architectural workflows to inform researchers and scientists in their model selection process.

The core distinction between Random Forest and XGBoost lies in their ensemble strategy, which directly dictates whether trees are built independently or sequentially.

Random Forest (Parallel Building): This algorithm operates on the principle of bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating). It constructs a multitude of decision trees independently and in parallel. Each tree is trained on a random subset of the training data (obtained via bootstrapping) and considers a random subset of features at each split. This parallel independence is the source of the model's robustness against overfitting. Once all trees are built, their predictions are aggregated, typically through a majority vote for classification or an average for regression, to produce the final output [7].

XGBoost (Sequential Building): XGBoost employs a technique known as boosting. Unlike the parallel approach, it builds trees sequentially, where each new tree is trained to correct the errors made by the combination of all previous trees. It uses a gradient descent framework to minimize a defined loss function. After each iteration, the algorithm calculates the residuals (the gradients of the loss function), and the next tree in the sequence is fitted to predict these residuals. The predictions of all trees are then summed to make the final prediction. This sequential, error-correcting nature often leads to higher accuracy but requires more careful tuning to prevent overfitting [7].

Table 1: Core Architectural Differences Between Random Forest and XGBoost

| Feature | Random Forest (Parallel) | XGBoost (Sequential) |

|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Method | Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) | Boosting (Gradient Boosting) |

| Tree Relationship | Trees are built independently & in parallel | Trees are built sequentially, each correcting its predecessors |

| Training Speed | Faster training via parallelization | Slower training due to sequential dependencies |

| Overfitting | Robust due to feature & data randomness | Prone to overfitting without proper regularization |

| Key Mechanism | Majority vote or averaging of tree outputs | Additive modeling; weighted sum of tree outputs |

Performance Comparison in Water Quality Prediction

Recent studies on surface and coastal water quality assessment provide robust experimental data comparing these two architectures.

Key Experimental Findings

A six-year comparative study (2017-2022) of riverine and reservoir systems in the Danjiangkou Reservoir, China, evaluated multiple machine learning models. The study aimed to optimize the Water Quality Index (WQI) by identifying key water quality indicators and reducing model uncertainty [7].

- Performance Accuracy: The XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance, achieving 97% accuracy for river sites with a logarithmic loss of just 0.12. In contrast, the Random Forest model achieved a lower accuracy of 92% in the same experimental setup [7].

- Key Parameter Identification: The optimized framework effectively identified critical water quality parameters. For rivers, these included total phosphorus (TP), permanganate index, and ammonia nitrogen. In the reservoir area, TP and water temperature were the key indicators identified by the model [7].

Another independent study on coastal water quality classification in Cork Harbour confirmed these findings. The results showed that both XGBoost and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithms outperformed others in predicting water quality classes, with KNN achieving 100% correct classification and XGBoost achieving 99.9% correct classification for seven different WQI models [20].

A comprehensive analysis of fourteen machine learning models for predicting WQI in Dhaka's rivers placed Random Forest as a top performer alongside Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). The ANN model achieved the highest scores (R²=0.97, RMSE=2.34), but Random Forest was also identified as one of the most effective models among those evaluated [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics in Water Quality Studies

| Study & Focus | Algorithm | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Danjiangkou Reservoir (Rivers) [7] | XGBoost | Accuracy: 97%, Logarithmic Loss: 0.12 |

| Danjiangkou Reservoir (Rivers) [7] | Random Forest | Accuracy: 92% |

| Cork Harbour (Coastal) [20] | XGBoost | Correct Classification: 99.9% |

| Dhaka's Rivers [21] | Random Forest | Ranked among top 2 models (with ANN) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, this section outlines the methodologies from the key studies cited.

This protocol describes the core methodology used to compare XGBoost and Random Forest.

- Data Collection & Preprocessing: Collect six years (2017-2022) of monthly water quality monitoring data from 31 sites in a reservoir system. Data includes multiple physicochemical parameters (e.g., TP, ammonia nitrogen).

- Feature Selection: Use the XGBoost algorithm combined with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify the most critical water quality indicators for the WQI model. This reduces dimensionality and measurement costs.

- Model Training & Comparison: Train multiple machine learning models, including Random Forest and XGBoost, on the dataset. The models are tasked with classifying or predicting water quality.

- Weighting & Aggregation: Compare different weighting methods (e.g., Rank Order Centroid) and aggregation functions to reduce model uncertainty. A novel Bhattacharyya mean WQI model (BMWQI) was proposed and tested.

- Performance Validation: Evaluate model performance using metrics such as prediction accuracy, logarithmic loss, precision, sensitivity, and specificity. Use validation results to select the best-performing model and WQI configuration.

This protocol was used to validate the performance of classifiers for existing WQI models.

- Data Source: Utilize water quality data collected by an environmental protection agency (e.g., Ireland's EPA).

- Classifier Evaluation: Implement four machine-learning classifier algorithms: Support Vector Machines (SVM), Naïve Bayes (NB), Random Forest (RF), and k-nearest neighbour (KNN), alongside XGBoost.

- WQI Model Application: Apply these classifiers to seven different WQI models, including weighted quadratic mean (WQM) and unweighted root mean square (RMS) models.

- Model Validation: Compare the classifiers based on a suite of metrics: accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score, to determine the best predictor for correct water quality classification.

Architectural Workflow Visualization

The diagrams below illustrate the fundamental logical workflows of the parallel and sequential tree-building processes.

Parallel Tree Building in Random Forest

Sequential Tree Building in XGBoost

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and conceptual frameworks essential for conducting comparative experiments in water quality prediction using tree-based models.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ML-Based Water Quality Prediction

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| XGBoost Library | Provides an optimized implementation of the gradient boosting framework, supporting the sequential tree-building architecture for high-accuracy predictions [7]. |

| Scikit-Learn Random Forest | Offers a robust and user-friendly implementation of the Random Forest algorithm for parallel tree building and baseline model comparison [7]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A feature selection technique used to identify the most critical water quality parameters (e.g., Total Phosphorus, Ammonia Nitrogen), reducing model complexity and cost [7]. |

| Water Quality Index (WQI) Models | Analytical frameworks (e.g., weighted quadratic mean) that transform complex water quality data into a single score, serving as the target variable for model prediction [20]. |

| Rank Order Centroid (ROC) Weighting | A method used within WQI models to assign weights to different water quality parameters, helping to reduce model uncertainty and improve accuracy [7]. |

Environmental datasets present unique challenges for predictive modeling, characterized by complex non-linear relationships, significant noise from measurement errors and uncontrolled variables, and intricate interaction effects between parameters. Within this domain, random forests and XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) have emerged as two dominant ensemble learning algorithms with particular relevance for ecological and environmental applications. Both methods excel at capturing complex patterns without strong prior assumptions about data distributions, making them particularly suitable for environmental systems where relationships are rarely linear or additive. This comparative analysis examines the inherent strengths of these algorithms specifically for water quality prediction research, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for model selection based on empirical performance metrics and methodological considerations.

The fundamental distinction between these algorithms lies in their ensemble construction approach: random forests build multiple decision trees in parallel using bootstrap aggregation (bagging) and random feature selection, while XGBoost constructs trees sequentially through gradient boosting, where each new tree corrects errors made by previous trees. This architectural difference creates complementary strengths for handling different aspects of environmental data complexity, particularly regarding noise resistance, non-linear pattern recognition, and computational efficiency.

Experimental Comparisons in Water Quality Prediction

Performance Benchmarking Studies

Recent research provides direct comparative data on algorithm performance for water quality prediction tasks. A six-year study of riverine and reservoir systems demonstrated that XGBoost achieved superior performance with 97% accuracy for river sites (logarithmic loss: 0.12), significantly outperforming other machine learning algorithms in water quality classification [7]. Similarly, research optimizing tilapia aquaculture water quality management found that multiple ensemble methods, including both Random Forest and XGBoost, achieved perfect accuracy on held-out test sets, with neural networks achieving the highest mean cross-validation accuracy (98.99% ± 1.64%) [22].

Table 1: Comparative Algorithm Performance in Environmental Applications

| Study Focus | Random Forest Performance | XGBoost Performance | Other Algorithms Tested | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Quality Index Classification | 92% accuracy | 97% accuracy (logarithmic loss: 0.12) | Support Vector Machines, Naïve Bayes, k-Nearest Neighbors | [7] |

| Aquaculture Water Quality Management | Perfect accuracy on test set | Perfect accuracy on test set | Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks | [22] |

| Urban Vitality Prediction | High performance (specific metrics not provided) | High performance (specific metrics not provided) | LightGBM, GBDT | [23] |

Methodological Protocols for Model Evaluation

The experimental protocols employed in these studies followed rigorous methodology for environmental machine learning applications. The water quality index study utilized a comprehensive framework incorporating parameter selection, sub-index transformation, weighting methods, and aggregation functions [7]. Feature selection was performed using XGBoost with recursive feature elimination (RFE) to identify critical water quality indicators, followed by performance validation across multiple algorithms. Key water quality parameters identified through this process included total phosphorus (TP), permanganate index, and ammonia nitrogen for rivers, and TP and water temperature for reservoir systems [7].

In aquaculture management research, researchers addressed the absence of standardized datasets by developing a synthetic dataset representing 20 critical water quality scenarios based on extensive literature review and established aquaculture best practices [22]. The dataset was preprocessed using class balancing with SMOTETomek and feature scaling before model training. Performance was assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, with cross-validation conducted to ensure robustness across multiple model architectures [22].

Technical Strengths for Environmental Data Challenges

Handling Non-Linearity and Complex Interactions

XGBoost demonstrates particular strength in capturing complex non-linear relationships and interaction effects in environmental systems. Research on ecosystem services trade-offs utilized XGBoost-SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) to quantify nonlinear effects and threshold responses, revealing that land use type, precipitation, and temperature function as dominant drivers with specific threshold effects [24]. For instance, water yield-soil conservation trade-offs intensified when precipitation exceeded 17 mm, while temperature thresholds governed transitions between trade-off and synergy relationships in water yield-habitat quality interactions [24]. This capability to identify and quantify specific environmental thresholds represents a significant advantage for ecological forecasting and management.

The model's effectiveness with non-linear patterns stems from its sequential error-correction approach, which progressively focuses on the most difficult-to-predict cases. This enables XGBoost to capture complex, hierarchical relationships in environmental data that might elude other algorithms. Additionally, XGBoost's implementation includes regularization parameters that prevent overfitting while maintaining model flexibility for capturing genuine complex patterns in ecological systems.

Noise Resistance and Robustness

Random Forest demonstrates inherent robustness to noisy data and outliers, a particularly valuable characteristic for environmental datasets where measurement error and uncontrolled variability are common. The algorithm's bagging approach, combined with random feature selection during tree construction, creates diversity in the ensemble that prevents overfitting to noise in the training data. This noise resistance makes Random Forest particularly suitable for preliminary exploration of environmental datasets and applications where data quality may be inconsistent.

Urban vitality research employing multiple machine learning models found that tree-based ensembles effectively handled the heterogeneous, multi-source data characteristic of urban environmental analysis [23]. The study incorporated social, economic, cultural, and ecological dimensions, with built environment factors demonstrating significant interactions and non-linear thresholds in their relationship to urban vitality metrics [23].

Table 2: Relative Strengths for Environmental Data Challenges

| Data Challenge | Random Forest Strengths | XGBoost Strengths | Environmental Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-linearity | Captures non-linearity through multiple tree partitions | Excels at complex non-linear patterns via sequential error correction | Identifying precipitation thresholds in ecosystem service trade-offs [24] |

| Noise Resistance | High robustness via bagging and random feature selection | Moderate robustness; regularized objective prevents overfitting | Handling measurement variability in water quality sensor data [7] |

| Interaction Effects | Automatically detects interactions through tree structure | Effectively captures complex hierarchical interactions | Modeling built environment factor interactions on urban vitality [23] |

| Missing Data | Handles missing values well through surrogate splits | Built-in handling of missing values during tree construction | Dealing with incomplete environmental monitoring records |

Implementation Framework for Environmental Research

Experimental Workflow for Water Quality Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental workflow for developing and comparing random forest and XGBoost models in water quality prediction research:

Water Quality Prediction Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Environmental ML

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Environmental Machine Learning

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Libraries | Scikit-learn, XGBoost Python package | Provides optimized implementations of ensemble algorithms | XGBoost classifier for water quality index prediction [7] |

| Interpretation Frameworks | SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) | Quantifies feature importance and identifies interaction effects | Analyzing non-linear drivers of ecosystem service trade-offs [24] |

| Feature Selection | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Identifies most predictive environmental parameters | Selecting critical water quality indicators [7] |

| Data Balancing | SMOTETomek | Handles class imbalance in environmental datasets | Preprocessing aquaculture management scenarios [22] |

| Model Validation | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Assesses model robustness and generalizability | Evaluating aquaculture management classifiers [22] |

Decision Framework and Research Recommendations

The comparative analysis reveals that algorithm selection should be guided by specific research priorities and data characteristics. XGBoost demonstrates advantages in prediction accuracy, computational efficiency, and ability to capture complex non-linear relationships and threshold effects, making it particularly valuable for forecasting applications where accuracy is paramount. Random Forest offers strengths in robustness to noise, reduced overfitting risk, and simpler hyperparameter tuning, making it well-suited for exploratory analysis and applications with particularly noisy or incomplete environmental data.

For water quality prediction specifically, research indicates that both algorithms can achieve excellent performance, with XGBoost holding a slight edge in classification accuracy while providing additional capabilities for identifying specific environmental thresholds and interaction effects. The integration of model interpretation techniques like SHAP significantly enhances the utility of both algorithms for environmental research by transforming "black box" predictions into actionable ecological insights [24].

Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of both algorithms, as well as enhanced interpretation frameworks specifically designed for environmental decision-making. The development of standardized benchmarking datasets for water quality prediction would facilitate more direct comparison of algorithm performance across diverse aquatic systems and monitoring scenarios.

Implementing RF and XGBoost for Water Quality Index and Parameter Prediction

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing for Water Quality Modeling

In the realm of water quality prediction, the selection of an appropriate machine learning model is crucial for achieving accurate and reliable results. This guide presents a comparative analysis of two prominent ensemble learning algorithms—Random Forests (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—within the specific context of water quality modeling. As environmental researchers and data scientists increasingly turn to machine learning to address complex water quality challenges, understanding the nuanced performance characteristics of these algorithms becomes essential for selecting the right tool for specific prediction tasks. Both methods have demonstrated significant promise in environmental informatics, but their relative strengths and weaknesses in handling diverse water quality datasets merit careful examination.

The following analysis synthesizes findings from recent peer-reviewed studies to objectively evaluate these algorithms across multiple performance dimensions, including predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and handling of typical water quality data challenges such as missing values and parameter weighting. By providing structured comparisons and detailed experimental protocols, this guide aims to support researchers in making evidence-based decisions for their water quality modeling initiatives.

Performance Comparison: Random Forests vs. XGBoost

Based on comprehensive studies evaluating machine learning algorithms for water quality prediction, the following table summarizes the comparative performance of Random Forests and XGBoost across key metrics:

Table 1: Performance comparison of Random Forests and XGBoost for water quality prediction

| Performance Metric | Random Forests (RF) | XGBoost | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 92% (Water quality classification) [7] | 97% (River sites) [7] | XGBoost achieved superior performance with lower logarithmic loss (0.12) |

| Feature Importance | Effective for identifying key indicators (e.g., TP, permanganate index) [7] | Superior capability with recursive feature elimination (RFE) [7] | XGBoost combined with RFE more effectively identifies critical water quality parameters |

| Uncertainty Reduction | Good performance with appropriate weighting methods [7] | Excellent, particularly with Rank Order Centroid weighting [7] | XGBoost significantly reduces model uncertainty in riverine systems |

| Handling Missing Data | Can handle missing values but may require preprocessing [25] | Built-in handling of sparse data [25] | XGBoost's internal handling provides advantage with incomplete datasets |

| Computational Efficiency | Parallel training capability [26] | Optimized gradient boosting with parallel processing [26] | Both offer efficient implementations, with XGBoost often faster in practice |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Less sensitive to hyperparameters [27] | Requires careful tuning but responds well to optimization [27] | RF more robust with default parameters; XGBoost benefits more from optimization |

Multiple studies have confirmed that both algorithms consistently rank among top performers in water quality prediction tasks. In a comprehensive six-year comparative study analyzing riverine and reservoir systems, XGBoost demonstrated marginally superior performance for river sites, achieving 97% accuracy compared to Random Forests' 92% [7]. However, research on aquaculture water quality management revealed that both algorithms can achieve perfect accuracy on test sets when properly configured, suggesting that the performance gap may be context-dependent [26].

For feature selection—a critical step in water quality model development—XGBoost combined with recursive feature elimination has shown particular effectiveness in identifying key water quality indicators such as total phosphorus (TP), permanganate index, and ammonia nitrogen for rivers, and TP and water temperature for reservoir systems [7]. This capability directly enhances model interpretability and monitoring efficiency.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

The foundation of robust water quality modeling begins with meticulous data preparation. Recent studies emphasize several critical preprocessing steps:

Data Acquisition and Integration: Modern water quality monitoring increasingly combines traditional sampling with emerging technologies. Cross-sector initiatives like River Deep Mountain AI (RDMAI) are developing open-source models that integrate data from environmental sensors, satellite imagery, and citizen science programs [28]. This multi-source approach helps address spatial and temporal data gaps while enhancing dataset richness.

Handling Missing Data: Water quality datasets frequently contain missing values due to equipment malfunctions, monitoring interruptions, or resource constraints. Research indicates that deep learning models, particularly those incorporating spatial-temporal analysis and dynamic ensemble modeling, show promise for advanced data imputation [25]. For traditional machine learning applications, studies comparing imputation techniques have found that K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) imputation enhances performance by preserving local data relationships, while noise filtering further improves predictive accuracy [29].

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction: The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method combined with XGBoost has emerged as a particularly effective approach for identifying critical water quality parameters [7]. Additionally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) remains widely used; studies implementing PCA with multiple machine learning algorithms achieved total accuracy up to 94.52% for water quality classification [30].

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for water quality modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Water Quality Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring & Data Acquisition | HydrocamCollect [31], IoT sensors [32], Remote sensing [32] | Camera-based hydrological monitoring, continuous data collection, broad spatial coverage |

| Data Preprocessing | SMOTETomek [26], KNN Imputation [29], PCA [30] | Handling class imbalance, missing data imputation, feature dimensionality reduction |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | XGBoost [7], Random Forest [7], Scikit-learn [29] | Algorithm implementation for classification and regression tasks |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | OPTUNA (OPT) [27], Grid Search [29] | Automated tuning of model parameters for optimal performance |

| Deep Learning Architectures | LSTM [29], CNN [29], Bidirectional LSTMs [29] | Capturing temporal patterns, extracting local features from complex data |

| Model Evaluation Metrics | RMSE, MAE, R² [27], Accuracy, Precision, Recall [26] | Quantifying prediction error, model accuracy, and classification performance |

Model Implementation and Training

The implementation of both Random Forests and XGBoost follows a structured workflow encompassing data preparation, model configuration, training, and validation. The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for comparative analysis:

Experimental Workflow for Water Quality Model Comparison

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: The initial phase involves collecting water quality data from multiple sources, which may include in-situ sensors, laboratory analyses, remote sensing, and citizen science initiatives [28] [32]. Subsequent preprocessing addresses common data quality issues: missing values through imputation techniques, class imbalance using methods like SMOTETomek [26], and feature scaling to normalize parameter distributions.

Feature Selection and Engineering: Comparative studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of combining XGBoost with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify the most predictive water quality parameters [7]. This step is crucial for optimizing monitoring efficiency and reducing computational requirements while maintaining model accuracy.

Model Configuration and Training: For XGBoost, critical hyperparameters include learning rate, maximum tree depth, subsampling ratio, and regularization terms [7] [27]. Random Forests require optimization of tree count, maximum features per split, and minimum samples at leaf nodes [7]. Studies implementing gradient boosting regression with OPTUNA optimization demonstrated superior performance in predicting WQI scores, highlighting the importance of systematic hyperparameter tuning [27].

Validation and Interpretation: Performance evaluation should employ multiple metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score for classification tasks, and RMSE, MAE, and R² for regression tasks [27] [26]. Cross-validation is essential to ensure robustness, particularly given the spatial and temporal variability in water quality datasets.

Technical Implementation and Optimization Strategies

Advanced Preprocessing Techniques

The integration of sophisticated preprocessing methods has significantly enhanced water quality model performance in recent studies:

Spatial-Temporal Data Enhancement: Research has demonstrated that incorporating spatial-temporal analysis through deep learning architectures like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) can capture complex temporal patterns and local features in water quality data [30] [29]. For spatial data integration, studies have successfully combined remote sensing imagery with in-situ measurements to expand geographical coverage while maintaining accuracy [32].

Handling Class Imbalance: Water quality datasets often exhibit significant class imbalance, with rare events (e.g., pollution incidents) being particularly important to detect. The Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) has proven effective in addressing this challenge. One comprehensive study utilizing SMOTE oversampling combined with PCA dimensionality reduction achieved a total accuracy of 94.52% using a BP neural network architecture [30].

Model-Specific Optimization Approaches

XGBoost Optimization: The superior performance of XGBoost in water quality prediction tasks stems from its gradient boosting framework with regularization, which reduces overfitting while maintaining high predictive accuracy [7]. Implementation best practices include:

- Employing the Rank Order Centroid (ROC) weighting method to significantly reduce model uncertainty [7]

- Combining with OPTUNA optimization for hyperparameter tuning, which has demonstrated RMSE values as low as 0.45 during testing phases [27]

- Utilizing built-in capabilities for handling missing data without extensive preprocessing [25]

Random Forests Optimization: While potentially slightly less accurate than XGBoost in direct comparisons, Random Forests offer advantages in training stability and interpretability [7] [26]. Key optimization strategies include:

- Leveraging the Boruta algorithm for enhanced feature selection to identify all relevant water quality parameters [7]

- Implementing permutation importance for more robust feature significance assessment

- Utilizing out-of-bag error estimation as an internal validation mechanism, reducing the need for separate test sets with limited data

The comparative analysis of Random Forests and XGBoost for water quality modeling reveals a nuanced performance landscape where both algorithms demonstrate distinct strengths. XGBoost consistently achieves marginally higher accuracy in direct comparisons, particularly for riverine systems, and offers superior capabilities in feature selection and uncertainty reduction when combined with appropriate weighting methods. Random Forests provide competitive performance with potentially greater training stability and reduced sensitivity to hyperparameter choices.

The selection between these algorithms should be guided by specific project requirements, including dataset characteristics, computational resources, and interpretability needs. For applications demanding the highest predictive accuracy and where computational resources permit extensive hyperparameter optimization, XGBoost appears preferable. For rapid prototyping, applications with limited tuning resources, or when model interpretability is paramount, Random Forests offer a robust alternative.

Future research directions should explore hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both algorithms, enhanced integration of spatial-temporal data through deep learning architectures, and continued refinement of open-source frameworks to make these advanced modeling techniques more accessible to water quality researchers and practitioners.

Water Quality Index (WQI) serves as a critical tool for transforming complex water quality data into a single, comprehensible value, enabling policymakers and researchers to quickly assess water safety for drinking and agricultural purposes. The accurate prediction of WQI is fundamental to achieving Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 6, which focus on clean water and healthy communities [33]. In recent years, machine learning (ML) approaches have revolutionized groundwater quality assessment by providing powerful predictive capabilities that surpass traditional statistical methods.

Among the various ML algorithms, Random Forest (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) have emerged as particularly promising techniques for environmental modeling. This case study provides a comparative analysis of these two algorithms within the specific context of groundwater quality prediction across different hydrogeological conditions in India. We examine their implementation, performance metrics, and relative advantages through two detailed research scenarios to guide researchers and scientists in selecting appropriate methodologies for water quality assessment.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Study Area Characteristics and Data Collection

The comparative analysis draws upon two distinct research initiatives conducted in different hydrogeological settings:

2.1.1 South Indian Semi-Arid River Basin Study [33]: Researchers collected groundwater samples from 94 dug and bore wells in the Arjunanadi river basin, a semi-arid region in Tamil Nadu, South India. The analysis included physical parameters (electrical conductivity, pH, total dissolved solids) and chemical parameters (sodium, magnesium, calcium, potassium, bicarbonates, fluoride, sulphate, chloride, and nitrate). The WQI values calculated from these parameters showed that 53% of the area (599.75 km²) had good quality water, while 47% (536.75 km²) had poor water quality, establishing a baseline for prediction models.

2.1.2 Northern India Groundwater Assessment [34]: This study involved 115 groundwater samples collected from 23 locations in Kasganj, Uttar Pradesh, Northern India. Researchers analyzed twelve water quality parameters: pH, total dissolved solids, total alkalinity, total hardness, calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, sulphate, nitrate, and fluoride. The study revealed alarming contamination levels, with TDS ranging from 252 to 2054 ppm and fluoride exceeding WHO permissible limits (0.21-3.80 ppm, average 1.55 ppm). WQI results indicated that 60.87% of samples were unfit for drinking, and 26.08% were of poor quality.

Water Quality Index Calculation

Both studies employed standardized WQI calculation methodologies, aggregating multiple physicochemical parameters into a single numerical value for simplified water quality classification [33] [34]. The WQI served as the dependent variable for prediction models, with the measured physicochemical parameters as independent variables.

Machine Learning Implementation

2.3.1 Model Training and Validation: In both studies, datasets were divided into training and testing subsets. The South India study assessed model efficacy using statistical errors including Relative Squared Residual (RSR), Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and Coefficient of determination (R²) [33]. The Northern India study utilized RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), MSE (Mean Square Error), MAE (Mean Absolute Error), and R² values for performance evaluation [34].

2.3.2 Feature Engineering: While not explicitly detailed in the groundwater studies, feature selection plays a crucial role in ML model performance. Related research indicates that incorporating lagged features (historical measurements) can significantly enhance prediction accuracy for environmental parameters [35].

2.3.3 Geochemical Modeling: The Northern India study complemented ML approaches with PHREEQC geochemical modeling to compute mineral saturation indices, identifying dolomite, calcite, and aragonite oversaturation [34]. This integration of process-based modeling with data-driven ML represents an advanced methodological approach.

Performance Comparison: Random Forest vs. XGBoost

Quantitative Results Analysis

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RF and XGBoost in Groundwater WQI Prediction

| Performance Metric | Random Forest (Northern India) | XGBoost (Northern India) | Random Forest (South India) | XGBoost (South India) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² Score | 0.951 [34] | 0.831 [34] | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported |

| RMSE | 5.97 [34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| MSE | 35.69 [34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| MAE | 5.49 [34] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Accuracy | Not reported | Not reported | Part of model sequence | Part of model sequence |

| Overall Performance Ranking | 1st among compared models [34] | 3rd among compared models [34] | 4th in performance sequence [33] | 3rd in performance sequence [33] |

Table 2: Comparative Advantages and Implementation Considerations

| Aspect | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy | Superior in Northern India study (R²: 0.951) [34] | Lower performance in Northern India study (R²: 0.831) [34] |

| Error Handling | Minimal error values across metrics [34] | Higher error rates compared to RF [34] |

| Computational Efficiency | Not explicitly reported but implied efficient | 30% boost in computational efficiency in related studies [35] |

| Model Robustness | Demonstrated high robustness in groundwater application [34] | Potentially less robust for WQI prediction [34] |

| Performance Context | Excels with complex hydrochemical data [34] | Better for large-scale environmental datasets [35] |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate | Higher, requires careful parameter tuning |

Contextual Performance Assessment

The performance disparity between Random Forest and XGBoost appears consistent across both studies, with RF demonstrating superior predictive capability for groundwater WQI applications. In the South India study, the overall performance sequence was reported as SVM > Adaboost > XGBoost > RF, indicating XGBoost outperformed RF in that specific environment [33]. This suggests that geographical and hydrochemical variations may influence the relative performance of these algorithms.

The Northern India study provided more comprehensive metrics, clearly demonstrating RF's superiority with higher R² (0.951 vs. 0.831) and minimal error values [34]. This performance advantage is significant for practical applications where accurate WQI prediction directly impacts public health decisions and resource management.

Technical Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for WQI prediction using machine learning approaches, as implemented in the cited studies:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods