Residual Solvents in Liposomes and Nanomedicine: Analysis, Challenges, and Regulatory Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive overview of residual solvent analysis in liposome and nanomedicine formulations, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals.

Residual Solvents in Liposomes and Nanomedicine: Analysis, Challenges, and Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of residual solvent analysis in liposome and nanomedicine formulations, addressing critical needs for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational importance of solvent management for product safety and regulatory adherence, details advanced analytical methodologies like headspace gas chromatography, and discusses common challenges in purification and scale-up. The content also covers method validation strategies and comparative evaluations of production techniques, serving as a practical guide for ensuring final product quality, meeting ICH guidelines, and facilitating the successful translation of nanomedicines from lab to clinic.

Why Residual Solvent Analysis is Critical for Nanomedicine Safety and Efficacy

In the field of nanomedicine, lipid-based nanocarriers such as liposomes and lipid nanoparticles (LNP) represent a cornerstone for advanced drug delivery systems. The complexities surrounding their manufacture and quality control are increasingly apparent, particularly regarding the presence of residual solvents [1] [2]. These organic volatile chemicals are used or produced during the synthesis of drug substances, excipients, or in the preparation of drug products but offer no therapeutic benefit [3]. Their inadequate removal poses significant toxic risks to patients and can adversely affect the critical quality attributes of the final pharmaceutical product, including particle size, crystalline structure, wettability, stability, and dissolution properties [3]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on residual solvents analysis, delineates the origins and risks of these solvents in lipid-based nanocarriers and provides detailed protocols for their determination, supporting the development of safe and efficacious nanomedicines.

Residual Solvents: Classification and Regulatory Framework

Definition and Origin in Nanocarrier Production

Residual solvents are defined as organic volatile chemicals that are used or produced in the manufacture of drug substances or excipients, or in the preparation of drug products [3]. In the context of lipid-based nanocarriers, they originate from specific manufacturing techniques:

- Solvent Injection: A potent and versatile method for preparing Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) where a lipid solution in water-miscible solvents like acetone, ethanol, isopropanol, or methanol is rapidly injected into an aqueous phase [4]. The diffusion of the solvent from the lipid-solvent phase into the aqueous phase is a crucial parameter for nanoparticle formation.

- Nanoprecipitation: Used for preparing polymer nanoparticles, often requiring organic solvents.

- Purification Processes: Inadequate purification following synthesis, such as size exclusion chromatography, dialysis, or ultrafiltration, can lead to solvent retention. Research indicates that complete removal requires processes that go beyond usual preparation methods [1] [2].

Toxicity and Regulatory Classification

Approximately 60-70 residual solvents are classified by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <467> and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3C(R8) guideline into three classes based on their toxicity [5] [6]. The following table summarizes this classification with examples relevant to nanocarrier production.

Table 1: Classification of Residual Solvents with Examples and Limits

| Class | Toxicological Rationale | Example Solvents | Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1(Solvents to be Avoided) | Known or suspected human carcinogens, strong environmental hazards [5] [6]. | - | Avoided in pharmaceutical products [6]. |

| Class 2(Solvents to be Limited) | Non-genotoxic animal carcinogens, causative agents of other irreversible toxicity (e.g., neurotoxicity, teratogenicity) [5] [6]. | Methanol, Chloroform, Triethylamine, Toluene [3] | Strict limits, typically in the range of a few hundred to a few thousand parts per million (ppm), depending on the specific solvent's toxicity [5]. |

| Class 3(Solvents with Low Toxic Potential) | Solvents with low toxic potential to man [5]. No health-based exposure limit is needed, but levels should be controlled. | Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), Ethyl Acetate [3] | PDE limits of 50 mg or more per day [5]. |

Analytical Methods for Determination

Gas chromatography (GC) is the preferred technique for residual solvent analysis due to its high sensitivity and ability to separate volatile compounds [5] [3]. Headspace sampling (HS) is particularly advantageous as it prevents contamination of the GC instrument by not directly injecting the API solution and provides an enhanced response for volatile solvents [5].

Detailed Protocol: Headspace Gas Chromatography

This protocol is adapted from a case study on liposomes and nanoparticles and a validated method for losartan potassium [1] [3].

Table 2: Key Parameters for HS-GC Method for Residual Solvent Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GC System | Agilent 7890A GC with Flame Ionization Detector (FID) and Headspace Sampler (model 7697A) [3]. | FID provides a universal and sensitive response for organic compounds. |

| Column | DB-624 capillary column (e.g., 30 m × 0.53 mm, 3.0 µm film thickness) [3]. A 60 m column can also be used for more complex mixtures [5]. | A mid-polarity column (6% cyanopropylphenyl/94% dimethyl polysiloxane) with a broad range of applicability for solvent polarities and volatilities [5]. |

| Carrier Gas | Helium, constant flow (e.g., 4.7 mL/min) [3]. Hydrogen can also be used [5]. | Provides inert transport of volatilized analytes through the column. |

| Oven Program | Initial Temp.: 40°C for 5 minRamp 1: 10°C/min to 160°CRamp 2: 30°C/min to 240°C for 8 min [3]. | Gradual temperature ramp ensures optimal resolution of solvents with a wide range of boiling points (e.g., from ~40°C to 189°C). |

| Headspace Conditions | Incubation Temp.: 100°CIncubation Time: 30 minSyringe/Loop Temp.: 105°CTransfer Line Temp.: 110°C [3]. | High temperature facilitates the partition of volatile solvents into the headspace. Conditions are optimized to be low enough to minimize API degradation [5]. |

| Sample Preparation | Diluent: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [3] or 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI) [5].Sample Concentration: Dissolve 200 mg of nanocarrier/API in 5.0 mL of diluent in a 20 mL HS vial [3]. | High-boiling solvents (DMSO b.p. 189°C, DMI b.p. 225°C) minimize interference and do not co-elute with common residual solvents, providing a sharp solvent peak [5] [3]. |

| Standard Preparation | Prepare mixed stock standard in DMSO/DMI at concentrations based on ICH Q3C(R8) specification limits. Use positive displacement pipettes for accurate and precise transfer of volatile liquids [5]. | Ensures accurate quantification. Positive displacement pipettes are more amenable for non-aqueous and volatile liquids than air-displacement pipettes [5]. |

Method Validation

The developed HS-GC method must be validated per ICH Q2(R1) or regional guidelines (e.g., ANVISA RDC 166/2017). Key validation parameters include [3]:

- Selectivity/Specificity: The method should be able to identify all target residual solvents in the sample without interference from the diluent or the nanocarrier matrix.

- Linearity: Demonstrated over a range from the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) to 120% of the specification limit, with a correlation coefficient (r) of ≥ 0.999 [3].

- Sensitivity: The LOQ for each solvent should be below 10% of its specification limit [3].

- Precision: Repeatability and intermediate precision should have Relative Standard Deviations (RSD) of ≤ 10.0% [3].

- Accuracy: Determined via recovery tests, with average recoveries typically between 85-115% [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Residual Solvent Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| DB-624 Capillary Column (Agilent Technologies) | A mid-polarity GC column for the separation of a wide range of residual solvent polarities and volatilities [5] [3]. |

| High-Purity DMSO or DMI Diluent | High-boiling solvent for dissolving samples; minimizes interference and provides a sharp, non-tailing solvent peak [5] [3]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Individual or mixed solvent standards in GC-grade purity for accurate calibration and quantification [3]. |

| Positive Displacement Pipettes | Essential for the accurate and precise transfer of non-aqueous and volatile liquid standards, ensuring data integrity [5]. |

| Sealed Headspace Vials | Airtight containers to prevent evaporation of volatile solvents before and during analysis, ensuring reliable results [6] [3]. |

Experimental Workflow and Data Analysis

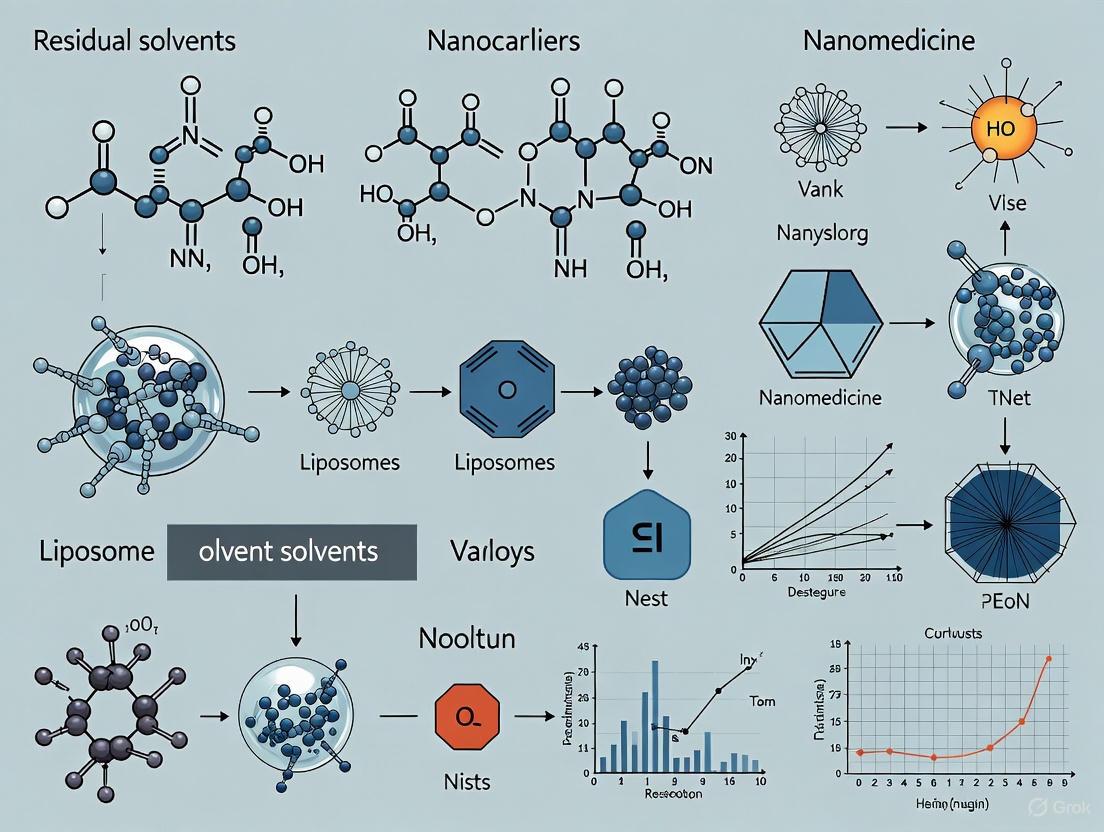

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the synthesis of lipid-based nanocarriers and the subsequent analysis of residual solvents.

Figure 1: Workflow for residual solvent analysis in nanocarrier development.

Case Study: Analysis of a Losartan Potassium Batch

A 2025 study developed and validated an HS-GC method for six residual solvents in losartan potassium. The analysis of a production batch detected only isopropyl alcohol and triethylamine, indicating that the purification processes were largely effective at removing other solvents used in synthesis (methanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, toluene) [3]. This case highlights the critical role of analytical verification in confirming the efficacy of purification steps.

Residual solvents represent a critical quality attribute in lipid-based nanocarriers, with origins in their synthesis and purification processes. Their control is mandated by strict regulatory guidelines driven by patient safety. The application of robust, validated headspace gas chromatography methods is fundamental to ensuring that nanomedicine products are both safe and efficacious. As shown, complete solvent removal is challenging and requires processes that may go beyond standard preparation methods [1] [2]. Therefore, integrating rigorous residual solvent testing early in the development process is indispensable for identifying bottlenecks and streamlining the translation of nanomedicines into clinical applications.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3C guideline provides a globally harmonized framework for controlling residual solvents in pharmaceutical products to ensure patient safety. These solvents are organic volatile chemicals used or formed during the manufacture of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), excipients, or drug products. As these substances may pose significant toxicological risks, the guideline establishes permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits based on comprehensive toxicological evaluations [7].

The classification system under ICH Q3C categorizes residual solvents into three classes based on their toxicity profiles:

- Class 1: Solvents to be avoided (known human carcinogens, strongly suspected human carcinogens, and environmental hazards)

- Class 2: Solvents to be limited (non-genotoxic animal carcinogens or possible causative agents of other irreversible toxicity)

- Class 3: Solvents with low toxic potential (solvents with low toxic potential to humans) [5] [7]

For researchers developing liposomal formulations and nanomedicines, compliance with ICH Q3C is particularly crucial. The manufacturing processes for these complex delivery systems often utilize organic solvents that must be carefully controlled to remain within established safety thresholds while maintaining product efficacy and stability [2].

ICH Q3C Classifications and Safety Thresholds

Classification System and PDE Limits

The ICH Q3C classification system establishes safety-based limits for residual solvents, expressed as Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) in milligrams per day, which are converted to concentration limits in parts per million (ppm) based on maximum daily drug dose [7]. The guideline undergoes periodic revisions, with the latest version being Q3C(R9) effective since April 2024 [8].

Table 1: ICH Q3C Residual Solvent Classifications and Representative PDEs

| Solvent Class | Toxicological Basis | Representative Solvents | PDE Limits | Examples in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Known human carcinogens, strongly suspected human carcinogens, environmental hazards | Benzene, carbon tetrachloride | PDE as low as 2 ppm (benzene) | Rarely used in manufacturing; strict controls required |

| Class 2 | Non-genotoxic animal carcinogens or possible causative agents of other irreversible toxicity | Methanol, acetonitrile, toluene | Methanol: 3000 ppmAcetonitrile: 410 ppmToluene: 890 ppm | Commonly used in synthesis, crystallization, and purification |

| Class 3 | Solvents with low toxic potential | Ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate | Ethanol: 5000 ppmGenerally higher limits | Extraction solvents, formulation aids, commonly used in liposome preparation |

Evolution of PDE Values: Ethylene Glycol Case Study

PDE values are periodically reassessed based on new toxicological evidence. A significant example is ethylene glycol (EG), where a discrepancy was identified between Summary Table 2 and the monograph in Appendix 5 of the guideline. Prior to 2017, EG was listed in Summary Table 2 as a Class 2 solvent with a PDE of 6.2 mg/day, while the monograph indicated 3.1 mg/day. After investigation, archival documents revealed that the 6.2 mg/day value had been accepted following reassessment of toxicity data in 1997, but the Appendix had not been updated accordingly. The original PDE of 6.2 mg/day (620 ppm) was reaffirmed as appropriate in the currently valid version of the guideline [9].

This case highlights the dynamic nature of solvent safety assessment and emphasizes the importance of consulting the most current version of ICH Q3C, as PDE values may be revised based on new scientific evidence.

Analytical Procedures for Residual Solvent Determination

Gas Chromatography with Headspace Sampling

The primary analytical technique for residual solvents determination is gas chromatography with headspace sampling (GC-HS), which provides the sensitivity, specificity, and precision required for quantifying volatile organic compounds at low ppm levels [5] [7]. This technique involves dissolving the sample in a suitable high-boiling solvent matrix within a sealed vial, heating to establish equilibrium partitioning of volatile analytes between the solution and headspace gas, and then sampling the headspace vapor for injection into the GC system [5].

Headspace sampling offers significant advantages for pharmaceutical analysis:

- Prevents injection port contamination by avoiding direct introduction of API solutions

- Enhances response for volatile solvents through favorable gas-phase partitioning

- Simplifies sample preparation for solid dosage forms and complex matrices

- Improves method robustness and instrument maintenance intervals

Generic Method Conditions for Broad Solvent Screening

A generic GC-HS method has been developed to efficiently quantify a wide range of residual solvents across multiple API projects, significantly reducing method development time while maintaining regulatory compliance [5].

Table 2: Generic GC-HS Method Conditions for Residual Solvent Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Column | DB-624 (60 m × 0.32 mm, 1.80 µm) | Mid-polarity with broad applicability for solvent polarities and volatilities |

| Carrier Gas | Hydrogen | Optimal chromatographic efficiency with appropriate safety precautions |

| Diluent | 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI) | High boiling point (225°C), minimal interference, sharp solvent peak |

| Sample Concentration | 50 mg/mL | Balances sensitivity with solubility considerations |

| Headspace Temperature | Optimized based on solvent boiling points (39.6-189°C range) | Ensures sensitivity for high-boiling solvents while minimizing API degradation |

This generic approach demonstrates strong linearity (r² > 0.998) across the range of 10% to 120% of ICH limits, with sensitivity suitable for quantifying Class 1 and 2 solvents at levels below 10 ppm [5]. The method can be adapted for different daily dosage levels by adjusting sample preparation parameters according to the established calculation formulae in ICH Q3C.

GC-HS Analysis Workflow

Application to Liposomes and Nanomedicine

Unique Challenges in Liposomal Formulations

Liposomal formulations present distinctive challenges for residual solvent control due to their complex structure and sensitivity to manufacturing conditions. The phospholipid bilayers of liposomes can encapsulate both hydrophilic drugs in the aqueous core and hydrophobic drugs within the lipid bilayer, creating multiple domains where solvent residues may partition differently [10]. Additionally, liposomes are susceptible to physical instability including drug leakage, fusion, or agglomeration when exposed to residual solvents, potentially compromising therapeutic efficacy [10].

The manufacturing processes for advanced liposomal systems often involve:

- Organic solvents for lipid dissolution and hydration

- Complex purification steps to remove solvents while maintaining liposome integrity

- Specialized techniques such as ethanolic injection, extrusion, and remote loading

- Surface modification procedures including PEGylation and ligand conjugation [10]

These processes necessitate careful solvent selection and rigorous control strategies to ensure final product quality and safety.

Case Study: Residual Solvent Removal Challenges

Research demonstrates that complete removal of residual solvents from nanomedicines requires processes that extend beyond usual preparation methods [2]. A comprehensive case study investigating various stages of liposome and nanoparticle synthesis revealed that multiple purification steps are often necessary to reduce solvent levels to within ICH Q3C limits.

Key findings from this research include:

- Standard preparation methods alone are frequently insufficient for complete solvent removal

- Purification techniques such as size exclusion chromatography, dialysis, and ultrafiltration show variable effectiveness depending on the solvent and formulation characteristics

- Process optimization is essential early in development to identify potential bottlenecks in solvent removal

- Analytical verification at each manufacturing stage provides critical data for process control

This case study provides valuable reference points for scientists to compare their own practices and streamline the translation of nanomedicines into safe, efficacious drug products [2].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: Residual Solvent Analysis by GC-HS

Protocol Title: Determination of Residual Solvents in Liposomal Formulations Using Headspace Gas Chromatography

Principle: The test specimen is dissolved in a suitable diluent in a vial, sealed, and maintained at constant temperature to achieve partitioning equilibrium of volatile compounds between the sample solution and vapor phase. An aliquot of the headspace is injected into a gas chromatograph equipped with a capillary column, and compounds are detected by flame ionization detector (FID).

Materials and Equipment:

- Gas chromatograph with headspace autosampler (Agilent 7890B GC with 7697A Headspace Sampler or equivalent)

- Capillary column: DB-624, 60 m × 0.32 mm ID, 1.8 µm film thickness (or equivalent)

- Hydrogen carrier gas, 99.999% purity

- Analytical balance (capability to 0.01 mg)

- Positive displacement pipettes for volatile solvents

- 10-mL headspace vials with crimp caps and PTFE/silicone septa

Reagent Preparation:

- Diluent: 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI), chromatographic grade

- Standard Stock Solution: Prepare mixed standard containing target solvents at concentrations calculated based on ICH Q3C limits using the formula:

Weight (mg) = (PDE in μg/day × 400) / (Density in g/mL × 1000)

- Working Standard Solution: Transfer 4.0 mL of stock standard to 100 mL volumetric flask, dilute to volume with DMI, mix thoroughly

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh approximately 50 mg of liposomal formulation into a headspace vial

- Add 1.0 mL of DMI diluent using positive displacement pipette

- Immediately seal vial with crimp cap and mix gently to dissolve/disperse sample

Instrumental Parameters:

- Headspace Conditions:

- Oven temperature: 80-120°C (optimized based on solvent volatility)

- Loop temperature: 140°C

- Transfer line temperature: 150°C

- Thermostating time: 45 minutes

- Carrier gas pressure: 15-20 psi

- GC Conditions:

- Injector temperature: 200°C

- Detector temperature: 250°C

- Oven program: 40°C for 20 minutes, ramp at 10°C/min to 180°C, hold 5 minutes

- Carrier gas flow: 2.0 mL/min constant flow

- Split ratio: 5:1

System Suitability:

- Resolution between closest eluting peaks: ≥1.5

- Relative standard deviation (RSD) of replicate injections: ≤5.0%

- Signal-to-noise ratio at LOQ: ≥10:1

Calculation:

Residual Solvent (ppm) = (A{sample} × C{std} × V × D) / (A_{std} × W)

Where: A{sample} = Peak area of solvent in sample A{std} = Peak area of solvent in standard C_{std} = Concentration of standard (mg/mL) V = Volume of diluent (mL) W = Weight of sample (mg) D = Dilution factor, if applicable

Method Validation Parameters

For regulatory compliance, the GC-HS method must be validated according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, including the following parameters:

- Specificity: No interference from sample matrix at retention times of target solvents

- Linearity: Minimum r² value of 0.995 over range of 10-120% of specification limit

- Accuracy: 90-110% recovery for spiked samples

- Precision: RSD ≤5.0% for repeatability and intermediate precision

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantitation (LOQ): Established for each solvent, typically LOQ at 10% of specification limit

- Robustness: Evaluation of small, deliberate variations in method parameters

Method Validation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Residual Solvent Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-HS System | Capillary column: DB-624 (6% cyanopropyl-phenyl), FID detector | Separation and detection of volatile solvents | Mid-polarity column provides broad applicability for solvent polarities |

| Headspace Vials | 10-20 mL, borosilicate glass with PTFE/silicone septa | Containment of sample during equilibration | Proper sealing essential to prevent solvent loss and maintain headspace integrity |

| Diluent: DMI | 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone, chromatographic grade, high purity | Sample dissolution medium | High boiling point (225°C) minimizes interference; low volatile impurities critical |

| Positive Displacement Pipettes | Calibrated for non-aqueous, volatile liquids | Accurate transfer of standard and sample solutions | Essential for reproducibility with volatile organic solvents |

| Reference Standards | USP/EP certified residual solvent standards | Method calibration and quantification | Purity certified for accurate quantification; prepare fresh working standards regularly |

| Carrier Gas | Hydrogen or helium, 99.999% purity | GC mobile phase | Hydrogen provides optimal efficiency with appropriate safety measures |

| Cryoprotectants | Sucrose, trehalose, other sugars | Liposome stabilization during processing | May impact solvent removal kinetics; consider in method development |

Regulatory Compliance Strategy for Nanomedicine Development

Implementation Framework

Successful regulatory compliance for liposomal formulations and nanomedicines requires a systematic approach integrating ICH Q3C principles throughout the development lifecycle. Key strategic elements include:

- Early Risk Assessment: Identify potential solvent residues during process development, considering both intended solvents and potential byproducts

- Process Design for Solvent Removal: Incorporate effective purification steps such as tangential flow filtration, dialysis, or chromatography based on solvent properties

- Analytical Control Strategy: Implement validated methods for monitoring solvent levels at critical process steps and in final product

- Documentation Practices: Maintain comprehensive records of solvent usage, removal processes, and analytical verification for regulatory submissions

Case Example: Generic Drug Development

A case study involving a Canada-based generic pharmaceutical manufacturer developing an antihypertensive drug demonstrates the practical application of ICH Q3C compliance strategies. The synthesis process utilized acetonitrile (Class 2, limit: 410 ppm) and methanol (Class 2, limit: 3000 ppm) as reaction and purification solvents. Through validated HS-GC methodology, the manufacturer demonstrated compliance with ICH Q3C limits, with results showing acetonitrile at 215 ppm and methanol at 1100 ppm, well within the prescribed limits. This comprehensive approach supported successful ANDA submission without regulatory queries related to solvent analysis [7].

The successful outcome was achieved through:

- Robust Method Development: HS-GC with FID detection providing specificity, linearity (r² > 0.998), and sensitivity (LOD/LOQ below 10 ppm)

- Comprehensive Validation: Including specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, LOD/LOQ, and robustness

- Complete Documentation: Validation protocols, Certificates of Analysis, and system suitability reports aligned with both ICH Q3C and USP <467> requirements

This case highlights the importance of a science-based, thoroughly documented approach to residual solvent control in meeting global regulatory expectations for nanomedicine products [7].

Impact of Solvents on Physicochemical Properties and Biological Activity

In the field of liposomes and nanomedicine research, solvents play a critically important dual role. They are essential in the manufacturing processes of both the nanocarriers themselves and the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) they encapsulate. Consequently, understanding their impact on the final product's physicochemical properties and biological activity is crucial for developing safe and effective therapeutics. Residual solvents, defined as organic volatile chemicals that remain in pharmaceutical products after manufacturing, can significantly influence critical quality attributes including liposome stability, drug encapsulation efficiency, and ultimately, therapeutic performance and safety profiles. This application note provides a structured framework for evaluating these effects within the context of a comprehensive residual solvents control strategy.

The Role of Solvents in Liposome Technology and Nanomedicine

Liposome Composition and Solvent Interactions

Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of one or more concentric lipid bilayers separated by aqueous compartments, structurally mimicking biological membranes [11] [12]. Their amphiphilic nature enables the encapsulation of both hydrophilic drugs (within the aqueous core) and hydrophobic drugs (within the lipid bilayer) [13]. This unique structure makes them particularly susceptible to solvent interactions at multiple levels:

- Membrane Integrity: Residual solvents can integrate into the lipid bilayer, altering membrane fluidity and permeability [12].

- Phase Transition Temperature: Solvents can modulate the phase transition temperature (Tₘ) of phospholipids, a critical parameter affecting stability, drug release kinetics, and encapsulation efficiency [12].

- Surface Charge: The surface characteristics of liposomes (anionic, cationic, or neutral) govern their interactions with biological systems, including cellular uptake and circulation time, which can be modified by solvent residues [12].

Impact of Solvents on Biological Performance

The presence of solvents, even in trace amounts, can profoundly influence the biological behavior of liposomal formulations:

- Biodistribution and Targeting: Solvents affecting liposome surface properties can alter their opsonization and recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system, thereby impacting circulation half-life and passive targeting via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in tumor tissues [13].

- Cellular Interactions: The four primary interaction pathways between liposomes and cells—endocytosis, fusion, adsorption, and lipid exchange—can all be modulated by solvent residues [12].

- Stability and Shelf-Life: Chemical interactions between residual solvents and lipid components or encapsulated APIs can lead to degradation products, reduced potency, and formulation instability during storage [3].

Analytical Framework for Residual Solvents

Regulatory Classification and Safety Thresholds

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3C guideline establishes a standardized classification system for residual solvents based on their toxicity profiles [5]:

Table 1: ICH Q3C Residual Solvents Classification

| Class | Description | Examples | Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Solvents to be avoided | Known or suspected human carcinogens, environmental hazards | Not specified (must be controlled to lowest practical levels) |

| Class 2 | Solvents to be limited | Non-genotoxic animal carcinogens, neurotoxicants, teratogens | Specific limits based on toxicity (e.g., Chloroform: 60 ppm, Toluene: 890 ppm) [3] |

| Class 3 | Solvents with low toxic potential | Solvents with low toxic potential | 50 mg or more per day [5] |

Platform Analytical Procedure for Residual Solvents Analysis

A robust headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC) platform method has been developed for the determination of residual solvents in pharmaceutical materials, incorporating elements of the enhanced approach outlined in ICH Q14 [14].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| GC System | Agilent 7890A or equivalent | Separation and detection of volatile compounds |

| Headspace Sampler | Agilent 7697A or equivalent | Volatile compound extraction and introduction |

| Analytical Column | DB-624 (30 m × 0.53 mm × 3 µm) or equivalent | Chromatographic separation |

| Diluent | Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI) | Sample solubilization with minimal interference |

| Carrier Gas | Helium or Hydrogen (>99.999% purity) | Mobile phase for chromatographic separation |

| Reference Standards | Individual or mixed solvent standards in GC grade | System suitability, identification, and quantification |

Detailed HS-GC Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Weigh approximately 200 mg of liposome or API sample into a 20 mL headspace vial [3].

- Add 5.0 mL of appropriate diluent (DMSO or DMI). DMSO is preferred for its high boiling point (189°C) and minimal interference with early eluting solvents [3].

- Seal the vial immediately with a crimp cap equipped with a PTFE/silicone septum.

Headspace Conditions:

- Incubation temperature: 100°C [3]

- Incubation time: 30 minutes [3]

- Syringe temperature: 105°C [3]

- Transfer line temperature: 110°C [3]

- Pressurization time: 1 minute [3]

GC Analytical Conditions:

- Column: DB-624 capillary column (30 m × 0.53 mm × 3 µm film thickness) [3]

- Carrier gas: Helium at constant flow rate of 4.718 mL/min [3]

- Oven temperature program: 40°C (hold 5 min), ramp to 160°C at 10°C/min, then to 240°C at 30°C/min (hold 8 min) [3]

- Inlet temperature: 190°C [3]

- Detector temperature: 260°C (FID) [3]

- Split ratio: 1:5 [3]

- Total run time: 28 minutes [3]

Method Validation

The analytical procedure should be validated according to regulatory requirements to ensure reliability, with key parameters including [3] [14]:

- Selectivity: No interference from diluent or sample matrix at the retention times of target solvents.

- Linearity: Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.999 for all solvents across the validated range (typically from LOQ to 120% of specification limit).

- Precision: Relative standard deviation (RSD) ≤ 10.0% for repeatability and intermediate precision.

- Accuracy: Average recoveries between 80-115% for spiked samples.

- Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): Signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 10:1, typically established at 10% of the specification limit.

- Robustness: Method performance remains unaffected by small, deliberate variations in parameters (e.g., oven temperature ±5°C, gas velocity changes).

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Solvent Effects

Protocol 1: Assessing Solvent Impact on Liposome Physicochemical Properties

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effects of solvent residues on critical quality attributes of liposomal formulations.

Materials:

- Liposome formulation (e.g., DPPC:Cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000, 55:40:5 molar ratio)

- Organic solvents (Class 1, 2, and 3 as per ICH Q3C)

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument

- Zeta potential analyzer

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Procedure:

- Prepare liposomes using the thin-film hydration method [12] or reverse-phase evaporation [12], incorporating controlled amounts of target solvents (0.1-1% w/w).

- Characterize the liposomes for:

- Size and Polydispersity: Using DLS to measure mean particle diameter and PdI [13].

- Zeta Potential: Using electrophoretic light scattering to determine surface charge [13].

- Phase Transition Temperature (Tₘ): Using DSC to assess lipid bilayer organization and stability [12].

- Encapsulation Efficiency: For both hydrophilic (e.g., calcein) and hydrophobic (e.g., curcumin) model compounds using dialysis and HPLC analysis [11].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Biological Impact of Solvent-Modified Liposomes

Objective: To determine the influence of solvent residues on liposome biological performance.

Materials:

- Cell culture models (e.g., Caco-2, HepG2, macrophage cells)

- Animal models (as appropriate for therapeutic application)

- Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry equipment

Procedure:

- In Vitro Cellular Uptake:

- Incubate solvent-containing and control liposomes (loaded with fluorescent markers like DiI or FITC) with relevant cell lines.

- Quantify uptake using flow cytometry and visualize using confocal microscopy [12].

- Cytotoxicity Assessment:

- Evaluate cell viability using MTT or Alamar Blue assays after 24-48 hours of exposure to solvent-modified liposomes [12].

- In Vivo Biodistribution:

- Administer near-infrared (NIR) dye-loaded liposomes to animal models.

- Track real-time distribution using IVIS imaging and quantify accumulation in target tissues (e.g., tumors via EPR effect) [13].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Case Study: Losartan Potassium Residual Solvents Analysis

A recent study developed and validated an HS-GC method for determining six residual solvents in losartan potassium API, detecting only isopropyl alcohol and triethylamine in the production batch, demonstrating the purification process's effectiveness [3]. This case highlights the importance of method development tailored to specific API synthesis pathways.

Structured Data Presentation

Table 3: Impact of Solvent Residues on Liposome Properties and Performance

| Solvent Class | Effect on Particle Size | Effect on Zeta Potential | Impact on Encapsulation Efficiency | Influence on Cellular Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Significant increase (>50%) | Variable, often neutral | Substantial decrease (20-40%) | Altered uptake kinetics, potential toxicity |

| Class 2 | Moderate increase (10-30%) | Moderate changes | Reduction (10-25%) | Modified biodistribution profile |

| Class 3 | Minimal change (<10%) | Minimal alteration | Slight effect (<10%) | Negligible impact at permitted levels |

Visualizing Analytical and Experimental Workflows

Residual Solvents Analysis Pathway

Solvent Impact Assessment Framework

The comprehensive assessment of solvent impacts on liposome physicochemical properties and biological activity is an essential component of pharmaceutical development. Through the implementation of robust analytical methods like the HS-GC platform procedure described herein, and systematic evaluation of solvent effects on critical quality attributes, researchers can ensure the development of safe, stable, and effective liposomal nanomedicines. The integrated approach outlined in this application note provides a framework for maintaining regulatory compliance while advancing the translational potential of novel nanocarrier systems.

In nanomedicine research, particularly in the development of liposomal drug delivery systems, the challenge of complete solvent removal after lab-scale production is a critical yet often underestimated factor impacting product safety and efficacy. Residual solvents from the manufacturing process can compromise the stability of the lipid bilayer, alter drug release profiles, and introduce cytotoxicity risks that jeopardize therapeutic applications [11]. Liposomes, spherical nanocarriers consisting of one or more concentric lipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous core, serve as versatile vehicles for improving drug solubility, stability, and site-specific delivery [13]. Their amphiphilic nature allows encapsulation of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic therapeutic agents, positioning them as ideal vehicles for advanced drug delivery [13].

The persistence of these residual solvents presents a significant barrier to the clinical translation of novel liposomal formulations, necessitating robust analytical methods and purification protocols. This case study examines the complexities of solvent removal within the broader context of residual solvents analysis, offering detailed methodologies for identifying, quantifying, and mitigating these process-related impurities to ensure final product quality and patient safety.

The Impact of Residual Solvents on Liposome Performance and Safety

Effects on Physicochemical Properties

Residual solvents retained in liposomal formulations can significantly alter critical quality attributes essential for consistent in vivo performance. Even trace solvent amounts can affect particle size distribution, zeta potential, and bilayer integrity, potentially modifying drug release kinetics and storage stability [11]. These alterations are particularly problematic for liposomes designed for targeted delivery, as they depend on precise control over size and surface characteristics to leverage mechanisms like the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect for passive accumulation in pathological tissues [13].

The structural integrity of the lipid bilayer is vulnerable to solvent residues, which can disrupt membrane packing and increase permeability. This disruption potentially leads to premature drug leakage before the liposome reaches its target site, diminishing therapeutic efficacy and potentially increasing systemic toxicity [11]. Furthermore, solvent residues may accelerate chemical degradation of both phospholipid components and encapsulated active ingredients, shortening the shelf-life of liposomal products.

Biological Safety Concerns

From a safety perspective, residual solvents present substantial risks in pharmaceutical products. Class 1 solvents with known carcinogenicity or toxicity must be strictly avoided in liposome manufacturing processes, while Class 2 solvents should be limited to established concentration limits [15]. These concerns are magnified in nanomedicine applications where liposomes are administered systemically, potentially distributing solvent residues throughout the body.

The cytotoxicity of residual solvents can manifest through membrane disruption, protein denaturation, or induction of apoptotic pathways in non-target cells [16]. For instance, chlorinated solvents and aromatic hydrocarbons can accumulate in lipid-rich tissues including the brain, while more hydrophilic solvents might cause immediate cytotoxic effects [15]. These safety concerns underscore the critical importance of effective solvent removal and rigorous residual analysis in liposomal drug development.

Analytical Methods for Residual Solvent Detection

Quantitative Determination Techniques

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Residual Solvent Detection in Liposomes

| Technique | Detection Principle | Limit of Detection | Applications in Liposome Analysis | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Chromatography with Headspace Sampling (HS-GC) | Separation of volatile compounds followed by MS or FID detection | Low ppm to ppb range | Quantification of Class 1, 2, and 3 solvents | High sensitivity, specificity for volatile residues |

| Automated Solvent Extraction | Quantitative hot solvent extraction | Matrix-dependent | Extraction of non-volatile residues, lipid content analysis | High throughput, reduced operator exposure |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | Fluorescence imaging of labeled components | N/A (qualitative) | Visualization of structural integrity, component distribution | Spatial resolution, non-destructive |

| Spectrophotometric Analysis | Absorption measurements of specific chromophores | Concentration-dependent | Total lipid quantification, compound-specific assays | High throughput, minimal sample preparation |

Headspace Gas Chromatography (HS-GC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Flame Ionization Detection (FID) represents the gold standard for volatile residual solvent analysis in pharmaceutical products [17]. This technique effectively separates and quantifies multiple solvent residues simultaneously, providing the sensitivity required to meet regulatory thresholds. For non-volatile solvent residues, automated solvent extraction systems like the VELP SER 158 enable quantitative determination of extractable compounds through controlled heating and solvent cycling, improving reproducibility while reducing analyst exposure to hazardous chemicals [17].

Complementary techniques like Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) offer qualitative assessment of liposomal integrity and component distribution, particularly when solvents or sealers are fluorescently labeled [16]. This approach provides visual evidence of solvent-induced structural alterations that might not be detected through chromatographic methods alone.

Green Analytical Chemistry Approaches

Recent advances emphasize greener alternatives in analytical chemistry, replacing hazardous solvents with more environmentally friendly options without compromising accuracy. Ethyl acetate and ethanol have demonstrated comparable extraction efficiency to conventional solvents like methyl-tert-butylether (MTBE) in lipidomics analyses, achieving recovery rates of 80-90% for most lipid classes [18]. Automated liquid-liquid extraction systems further enhance method greenness by minimizing solvent consumption, reducing variability, and limiting operator exposure to organic vapors [18].

The AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric system provides a comprehensive assessment of method environmental impact, evaluating factors including energy consumption, waste generation, and reagent toxicity [18]. Adopting these green principles in residual solvent testing aligns with broader sustainability initiatives while maintaining analytical rigor.

Experimental Protocols for Solvent Removal and Analysis

Protocol 1: Residual Solvent Quantification via Headspace GC-MS

Principle: This protocol describes the quantitative analysis of volatile residual solvents in liposomal formulations using static headspace sampling coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Materials:

- HS-GC-MS system with autosampler

- DB-624 or equivalent GC column (6% cyanopropylphenyl, 94% dimethylpolysiloxane)

- Certified solvent standards (Class 1, 2, and 3)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.9% purity) as dilution solvent

- 20 mL headspace vials with PTFE/silicone septa

Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare individual stock solutions of target solvents in DMSO at approximately 1 mg/mL. Combine appropriate aliquots to create a mixed working standard solution containing all analytes of interest.

- Calibration Standards: Dilute the working standard solution with DMSO to prepare at least five calibration levels covering the expected concentration range (typically 0.1-100 μg/mL).

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh approximately 500 mg of liposomal formulation into a 20 mL headspace vial. Add 1.0 mL of DMSO, cap immediately, and vortex for 30 seconds to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

- HS-GC-MS Conditions:

- Headspace: Incubate at 120°C for 30 minutes with agitation; injection volume: 1 mL

- GC: Injector temperature: 200°C; Split ratio: 10:1; Oven program: 40°C (hold 5 min), ramp 10°C/min to 200°C (hold 5 min); Carrier gas: Helium, 1.0 mL/min

- MS: Transfer line temperature: 230°C; Ion source temperature: 230°C; Acquisition mode: Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM)

- Analysis: Inject calibration standards and samples in triplicate. Construct calibration curves by plotting peak area against concentration for each analyte. Quantify solvent residues in samples using the established calibration curves.

Validation Parameters: Determine method specificity, accuracy (85-115%), precision (RSD <15%), limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) for each target solvent according to ICH guidelines.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Solvent Removal Efficiency Using Green Metrics

Principle: This protocol assesses the effectiveness of solvent removal techniques while incorporating green chemistry principles to evaluate environmental impact.

Materials:

- Rotary evaporator with vacuum controller

- Nitrogen evaporator

- Freeze dryer

- AGREEprep software or equivalent green assessment tool

- Ethyl acetate, ethanol, acetone (green solvent alternatives)

- Conventional solvents (chloroform, methanol, hexane) for comparison

Procedure:

- Liposome Preparation: Prepare liposomes using thin-film hydration method with varied solvent systems (conventional vs. green alternatives).

- Solvent Removal: Apply different removal techniques to identical liposome batches:

- Method A: Rotary evaporation at reduced pressure (40°C, 200 mbar, 60 min)

- Method B: Nitrogen purge at ambient temperature (4 hours)

- Method C: Freeze drying (-50°C, 0.05 mbar, 48 hours)

- Residual Analysis: Quantify remaining solvent levels using HS-GC-MS as described in Protocol 1.

- Greenness Assessment: Input method parameters (solvent type, energy consumption, waste generation) into AGREEprep software to calculate greenness scores (0-1 scale) for each removal technique.

- Liposome Characterization: Evaluate critical quality attributes of the final liposomes:

- Particle size and PDI by dynamic light scattering

- Zeta potential by electrophoretic light scattering

- Encapsulation efficiency by HPLC after separation of free drug

Calculation:

- Solvent removal efficiency (%) = [(Initial solvent amount - Final solvent amount) / Initial solvent amount] × 100

- Overall greenness score = AGREEprep output (incorporating safety, health, and environmental factors)

Protocol 3: Structural Integrity Assessment Post-Solvent Removal

Principle: This protocol evaluates the impact of solvent removal techniques on liposomal structure and membrane integrity using complementary microscopy techniques.

Materials:

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

- Rhodamine B-labeled phospholipids

- Glutaraldehyde (2.5% in buffer) for fixation

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare liposomes incorporating 0.5 mol% rhodamine B-labeled phospholipid during formulation. Subject identical liposome batches to different solvent removal techniques (as in Protocol 2).

- CLSM Analysis:

- Place 20 μL of liposome suspension on a glass slide and cover with a coverslip

- Image using 543 nm excitation and 565-615 nm emission settings

- Acquire Z-stack images (1 μm slices) to assess three-dimensional distribution

- Quantify fluorescence intensity and distribution uniformity using image analysis software

- SEM Sample Preparation:

- Fix liposomes with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 2 hours at 4°C

- Dehydrate through graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%)

- Critical point dry using liquid CO₂

- Sputter coat with gold/palladium (10 nm thickness)

- SEM Analysis: Image samples at accelerating voltages of 5-15 kV, examining membrane surface morphology, vesicle integrity, and potential structural defects.

- Image Analysis: Compare samples from different solvent removal methods for:

- Structural defects in lipid bilayers

- Vesicle size distribution and shape uniformity

- Presence of aggregates or collapsed structures

Interpretation: Correlate structural findings with residual solvent data and functional performance metrics (e.g., drug release profiles) to identify optimal solvent removal conditions that preserve liposomal integrity.

Process Optimization Strategies

Advanced Removal Techniques

Effective solvent removal in lab-scale liposome production requires implementing optimized techniques that balance efficiency with product quality. Multi-step approaches often yield superior results compared to single-method strategies [15]. An initial bulk solvent removal via rotary evaporation at controlled temperatures followed by secondary removal using nitrogen purge or vacuum drying can effectively reduce residues to acceptable levels while preserving liposome integrity.

The selection of solvent systems significantly impacts removal efficiency. Green solvent alternatives like ethyl acetate and ethanol demonstrate favorable environmental and safety profiles while maintaining high extraction efficiency for lipid-based systems [18]. These solvents typically have lower boiling points and reduced toxicity compared to conventional options, facilitating more complete removal and reducing residual levels in final products.

Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Implementation

Integrating real-time monitoring through Process Analytical Technology (PAT) enables better control over solvent removal processes. Techniques like in-line Raman spectroscopy or near-infrared (NIR) probes can track solvent concentrations throughout the removal process, allowing for dynamic endpoint determination rather than fixed-duration processing [15].

Statistical design of experiments (DoE) approaches can optimize multiple process parameters simultaneously, identifying critical interactions between temperature, pressure, duration, and flow rates that maximize solvent removal while minimizing product degradation [11]. This data-driven methodology establishes a design space for consistent, robust manufacturing of liposomal formulations with controlled residual solvent levels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Solvent Removal Studies

| Item | Function in Solvent Removal Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Acetate | Green solvent alternative for lipid extraction | Shows comparable recovery (80-90%) to conventional solvents for most lipid classes [18] |

| Ethanol | Extraction solvent and rinsing agent | GRAS status; effective in automated liquid-liquid extraction systems [18] |

| Automated Solvent Extractor | Quantitative extraction of contaminants | Enables hot solvent extraction while minimizing operator exposure; useful for method development [17] |

| Rotary Evaporator | Primary bulk solvent removal | Standard equipment; requires optimization of bath temperature, rotation speed, and vacuum level |

| Nitrogen Evaporation System | Gentle concentration and final solvent removal | Prevents oxidation; suitable for heat-sensitive compounds |

| Freeze Dryer | Removal of water-miscible solvents | Effective for aqueous-based liposome dispersions; preserves structural integrity |

| Headspace GC-MS | Quantitative residual solvent analysis | Gold standard for volatile residue detection; provides regulatory compliance data |

| Centrifugal Separators | Separation of solvents from lipid phases | Purpose-built systems like WSB series handle viscous mixtures efficiently [19] |

Complete solvent removal in lab-scale liposome production remains a multifaceted challenge requiring integrated analytical and process strategies. As detailed in this case study, successful approaches combine rigorous residual analysis using chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques with optimized removal protocols that prioritize both efficiency and final product quality. The adoption of green solvent alternatives and automated systems presents promising avenues for improving both environmental sustainability and analytical performance.

Ongoing research into novel removal techniques, including supercritical fluid extraction and membrane-based separation, may offer future solutions to the persistent challenge of residual solvents. By implementing comprehensive solvent management strategies throughout the development lifecycle, researchers can accelerate the translation of innovative liposomal formulations from laboratory research to clinical applications, ensuring both therapeutic efficacy and patient safety.

Visual Workflows

Solvent Removal and Analysis Workflow

Residual Solvent Impact Assessment

Analytical Techniques for Detecting and Quantifying Residual Solvents

In the development of liposomes and other nanomedicines, controlling the quality and safety of the final product is paramount. Residual solvents—volatile organic chemicals used or produced during the manufacture of drug substances—represent a significant toxicological risk and can adversely affect product stability, particle characteristics, and efficacy. Headspace Gas Chromatography (HS-GC) has emerged as the gold-standard technique for monitoring these residual solvents, providing the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability required to meet stringent regulatory standards. This is particularly crucial for nanomedicines like liposomes, where complexities in manufacture and purification create significant challenges for complete solvent removal. Research has demonstrated that conventional preparation methods alone are often insufficient for complete residual solvent removal, necessitating robust analytical techniques like HS-GC for quality control [2] [20].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3C guideline categorizes residual solvents based on their toxicity and sets permissible exposure limits. Class 1 solvents (e.g., benzene) are known human carcinogens and should be avoided. Class 2 solvents (e.g., chloroform, dichloromethane) possess inherent but reversible toxicity, and their levels must be restricted. Class 3 solvents (e.g., ethanol, ethyl acetate) are considered less toxic but must still be controlled [3] [5]. For nanomedicine researchers, implementing a robust, generic HS-GC method ensures patient safety, streamlines regulatory compliance, and provides critical data to optimize manufacturing and purification processes [2] [21].

Technical Foundation: Principles and Advantages of HS-GC

Core Principles of Static Headspace Sampling

Static HS-GC is a two-step technique designed to analyze volatile compounds in complex matrices without introducing non-volatile sample components into the chromatographic system. The process begins when a sample dissolved in a suitable high-boiling-point diluent is sealed in a vial and heated. Volatile residual solvents partition between the liquid phase and the gas phase (headspace) above it. After equilibrium is reached, an aliquot of the headspace vapor is automatically injected into the GC system for separation and quantification [21] [22].

The fundamental relationship in static headspace analysis, as defined by Kolb, is expressed as: C~G~ = C~0~ / (K + β), where C~G~ is the concentration in the gas phase, C~0~ is the original concentration in the solution, K is the partition coefficient, and β is the phase ratio (V~G~/V~S~) [22]. For accurate quantification, the partition coefficient (K) and phase ratio (β) must be identical for both standard and sample solutions, underscoring the need for consistent matrix conditions.

Key Advantages for Liposome and Nanomedicine Analysis

- Enhanced System Protection: Since only volatile components are introduced into the GC inlet, non-volatile lipids, polymers, and other matrix components are excluded. This drastically reduces instrument maintenance, prevents liner degradation, and extends column lifetime [21] [22].

- Superior Sensitivity for Volatiles: The headspace technique provides an enhanced response for volatile solvents due to favorable gas-phase partitioning, making it ideal for detecting low concentrations of common Class 1 and Class 2 solvents [5].

- Handling of Challenging Matrices: Many pharmaceutical materials, including certain lipid-based excipients, are not readily soluble at room temperature. The HS-GC oven heats the vials with vigorous shaking, facilitating sample dissolution and the release of solvents into the headspace, thereby enabling the analysis of difficult matrices [21].

Method Implementation: A Generic HS-GC Protocol

The following protocol provides a validated, generic method for determining residual solvents, which can be adapted for various nanomedicine matrices, including liposomes [21] [5] [22].

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Importance | Common Choices & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GC System with HS Autosampler | Automated, precise injection of headspace vapor; critical for reproducibility. | Agilent, PerkinElmer, or equivalent systems. Must be equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) [23] [21]. |

| Capillary GC Column | Separates the complex mixture of volatile solvents. | DB-624, Rtx-624, or equivalent (6% cyanopropylphenyl / 94% dimethyl polysiloxane). Dimensions: 30 m x 0.32/0.53 mm, 1.8 µm film thickness [3] [21] [24]. |

| High-Purity Diluent | Dissolves the sample; high boiling point prevents interference. | ( N,N )-Dimethylacetamide (DMA), ( N,N )-Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or 1,3-Dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI). Must be headspace-grade to minimize background noise [21] [5] [22]. |

| Residual Solvent Standards | Enables identification and quantification of target analytes. | Certified reference materials for each solvent of interest (e.g., methanol, chloroform, triethylamine, n-heptane) in GC-grade purity [3] [25]. |

| Carrier Gas | Mobile phase for chromatographic separation. | High-purity Helium or Hydrogen. Hydrogen offers faster optimal linear velocity [3] [24]. |

Preparation of Standard and Sample Solutions

- Mixed Stock Standard Preparation: Prepare a custom stock standard by accurately weighing or pipetting all target solvents into a volumetric flask containing the chosen diluent (e.g., DMI). The concentration of each solvent should be calculated based on its ICH limit and the intended sample concentration. Use positive displacement pipettes for accurate and reproducible transfer of volatile organic liquids [5] [22].

- Working Standard Solution: Dilute an aliquot of the stock standard with the same diluent to create a working standard solution. This solution should contain all residual solvents at their respective specification limits [22].

- Sample Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh approximately 100 mg of the liposome or nanomedicine sample into a headspace vial. For materials of limited availability, sample amounts as low as 10 mg can be used [21] [22]. Add 1.0 mL of diluent, seal the vial immediately with a crimp cap equipped with a PTFE-lined septum, and vortex vigorously to ensure complete dissolution or a homogeneous suspension.

Instrumental Conditions and Chromatographic Separation

Table 2: Generic HS-GC-FID Conditions for Residual Solvent Analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Alternative/Optimized Setting |

|---|---|---|

| GC Column | DB-624, 30 m × 0.53 mm, 3.0 µm [3] | Rtx-624, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 1.4 µm [24] |

| Carrier Gas & Flow | Helium, 4.7 mL/min [3] | Hydrogen, 2.0 mL/min [24] |

| Inlet Temperature | 190°C [3] | 280°C [24] |

| Split Ratio | 1:5 [3] | 10:1 [24] |

| Oven Program | 40°C (hold 5 min) → 10°C/min → 160°C → 30°C/min → 240°C (hold 8 min) [3] | 30°C (hold 6 min) → 15°C/min → 85°C (hold 2 min) → 35°C/min → 250°C [24] |

| FID Temperature | 260°C [3] | 320°C [24] |

| Headspace Conditions | Incubation: 100°C; Time: 30 min; Syringe/TL Temp: 105/110°C [3] | Incubation: 80°C; Time: 45 min; Syringe Temp: 150°C [24] |

| Run Time | ~28 minutes [3] | ~16.5 minutes [24] |

The following workflow diagrams the complete analytical procedure from sample preparation to data analysis:

Method Validation and Performance

For any analytical method to be used in a regulated environment, it must be rigorously validated to ensure it is fit for purpose. The following key validation parameters, as demonstrated in multiple studies, should be assessed [3] [23].

Table 3: Typical Method Validation Parameters and Results

| Validation Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Exemplary Results from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | No interference from sample matrix at the retention times of target solvents. | Demonstrated for 6 solvents in Losartan API; resolution (R~s~) > 1.5 for all peaks [3] [5]. |

| Linearity & Range | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.990 over the range from LOQ to 120-200% of the specification limit. | r ≥ 0.999 for methanol, IPA, ethyl acetate, etc. [3]. r > 0.990 for 8 solvents in suvorexant [25]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of ≤ 15.0% for multiple injections. | RSD ≤ 10.0% for 6 solvents [3]. RSD < 5.0% for 8 solvents in suvorexant analysis [25]. |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | Average recovery between 80-115% for spiked samples. | Recoveries from 95.98% to 109.40% reported [3]. 85-115% recovery for a 27-solvent method [21]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) ≥ 10. | LOQs established below 10% of the ICH specification limit for all solvents [3]. |

| Robustness | Method performance remains acceptable despite small, deliberate changes to parameters. | Method robust under small modifications to oven temperature, gas velocity, and column batch [3] [21]. |

Application in Nanomedicine: A Liposome Case Study

A 2020 case study highlighted the critical importance of HS-GC in understanding and optimizing purification processes for nanomedicines. The research investigated residual solvent levels at various stages of liposome preparation and purification. Using HS-GC, the scientists quantified solvents like chloroform throughout the process, comparing purification techniques such as size exclusion chromatography and dialysis [2] [20].

A key finding was that conventional preparation methods were insufficient for complete solvent removal, and the effectiveness of purification depended heavily on the specific process employed. This work serves as a valuable reference for comparing practices and streamlining the translation of nanomedicines into safe drug products. It underscores that HS-GC is not merely a quality control check but an essential tool for providing feedback to the manufacturing process, enabling scientists to design purification strategies that reliably reduce residual solvents to safe levels [2].

Headspace Gas Chromatography stands as an indispensable, gold-standard technique in the modern development of liposomes and other nanomedicines. Its specificity, sensitivity, and robustness make it the preferred method for complying with global regulatory standards for residual solvents. The generic protocols and validation data outlined in this application note provide a solid foundation that research scientists can adapt and validate for their specific lipid-based formulations. By implementing this reliable analytical technique, developers can ensure the safety, quality, and efficacy of their innovative nanomedicine products, ultimately accelerating their path from the laboratory to the clinic.

In the field of nanomedicine research, the accurate quantification of residual solvents in advanced drug delivery systems like liposomes is critical for ensuring product safety and efficacy. Residual solvents, classified as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), can compromise nanoparticle stability, alter biodistribution, and pose significant toxicological risks. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) has emerged as a powerful, green sample preparation technique that integrates seamlessly with gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS), enabling highly sensitive and selective analysis of these problematic analytes. This combination is particularly suited for complex pharmaceutical matrices, offering superior performance over traditional methods like static headspace techniques [26]. As a solvent-free technique that combines sampling, extraction, and concentration into a single step, SPME represents a paradigm shift in sample preparation for quality control in nanomedicine development [27] [28]. This application note provides detailed protocols and experimental data frameworks for implementing SPME-GC-MS/MS in the context of residual solvents analysis in liposomal formulations and other nanomedicines, specifically designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Background and Principles

SPME operates on the principle of equilibrium extraction, where a fused-silica fiber coated with a thin layer of extracting phase is exposed to either the sample directly (direct immersion) or the headspace above the sample (headspace-SPME). For residual solvents analysis in thermosensitive nanomedicines like liposomes, headspace-SPME (HS-SPME) is generally preferred as it protects the fiber from non-volatile matrix components that could foul the coating while still efficiently extracting volatile target analytes [29].

The quantification process relies on the establishment of equilibrium between the sample matrix, the headspace, and the fiber coating. The amount of analyte extracted by the fiber at equilibrium is linearly proportional to its initial concentration in the sample, making it ideal for quantitative analysis [30]. When coupled with GC-MS/MS, the technique provides an additional dimension of selectivity and sensitivity through multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), which is crucial for distinguishing target solvents from complex sample matrices and achieving the low detection limits required by regulatory standards such as ICH Q3C.

The development of advanced coating materials has significantly enhanced SPME performance. Materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), and carbon-based nanomaterials like graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) offer superior extraction efficiency and selectivity due to their high surface-to-volume ratios and tunable surface properties [27] [28]. These materials facilitate interactions with analytes through hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, and electrostatic forces, leading to enhanced enrichment capabilities particularly beneficial for trace-level residual solvent analysis.

SPME-GC-MS/MS Protocol for Residual Solvents in Liposomes

Materials and Reagents

- Liposome Samples: Liposomal formulations suspended in aqueous media. Store at 4°C if not analyzed immediately.

- Internal Standards: Deuterated solvents (e.g., acetone-d6, chloroform-d) are recommended for optimal quantification accuracy [30].

- SPME Fibers: Select fiber coatings based on target solvent polarity and volatility. For a broad range of residual solvents, mixed-phase coatings such as Carboxen/Polydimethylsiloxane/Divinylbenzene (CAR/PDMS/DVB) or Divinylbenzene/Polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/PDMS) are highly effective [26] [29]. Polydimethylsiloxane/Divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB) has also been identified as highly sensitive for pharmaceutical solvents [26].

- Vials: 20 mL amber headspace vials with septum-type caps (e.g., Agilent Product Number 5188-6537) [29].

- Gas Chromatography System: GC system (e.g., Agilent 7890A) coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., Agilent 7010B GC/MS Triple Quad) [29].

- GC Column: Mid-polarity stationary phase columns such as Agilent VF-5ms (30 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness) are suitable for separating a wide range of volatile solvents [29].

- Software: Quantitative analysis software (e.g., Agilent MassHunter Quantitative Analysis version 10.0) [29].

Detailed Experimental Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Transfer 2.0 mL of the liposomal suspension into a 20 mL headspace vial.

- Add 10 µL of internal standard working solution.

- Immediately seal the vial with a magnetic screw cap with a PTFE/silicone septum. Ensure crimping is secure to prevent volatile loss.

- Gently vortex the vial for 30 seconds to homogenize. Note: Avoid vigorous shaking to prevent foaming of the liposomal suspension.

HS-SPME Extraction:

- Place the prepared vial into the headspace autosampler tray or a heated agitator block.

- Condition the sample at 80°C for 20 minutes with agitation (250 rpm) to allow volatiles to partition into the headspace [29].

- Following equilibration, expose the conditioned SPME fiber (e.g., CAR/PDMS/DVB) to the vial headspace for 20-30 minutes at 80°C, with continuous agitation [29].

GC-MS/MS Analysis:

- After extraction, immediately retract the fiber and introduce it into the GC injector.

- Use a split injection mode with a high split ratio (e.g., 200:1) to ensure narrow analyte bands and prevent overloading, especially when using high-capacity fibers like CAR/PDMS/DVB [29].

- Desorb the analytes in the hot injector port for 2-5 minutes (e.g., 250°C).

- GC Parameters: Use Helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.0 mL/min [29]. Employ a temperature ramp program: 40°C (hold 10 min), then increase at 15°C/min to 200°C, followed by a rapid ramp at 50°C/min to 325°C (hold 3 min). Total GC run time is approximately 26 minutes [29].

- MS/MS Parameters: Operate the ion source in Electron Ionization (EI) mode at 230°C. Use Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for each target solvent and internal standard. Optimize collision energies for each specific transition to maximize sensitivity and selectivity.

Fiber Maintenance:

- After each desorption, condition the fiber in a dedicated conditioning station or the GC injector port for 5-10 minutes to prevent carryover. With advanced coatings like MWCNT–IL/PANI, fibers can be reused over 150 times without significant performance loss [28].

Data Analysis and Quantification

- Process the acquired data using quantitative analysis software. Identify compounds by comparing the retention times and MRM transitions with those of authentic standards.

- For each target solvent, establish a calibration curve using the internal standard method. A 5-7 point calibration curve is recommended, with concentrations spanning the expected range in samples.

- Set a retention time window of approximately ±0.1 minutes for each analyte to minimize false positives [29].

- The quantifier ion (most abundant) is used for concentration calculation, while qualifier ions (typically 2-3 additional ions) are used for confirmatory identification. The ratio of qualifier to quantifier ions should match that of the standard within a defined tolerance (e.g., ±20-25%) [29].

The workflow below summarizes the key steps of this protocol:

Expected Results and Data Presentation

Quantitative Performance Data

When validated, the HS-SPME-GC-MS/MS method is expected to yield excellent quantitative performance for residual solvents in liposomal matrices. The table below summarizes typical validation parameters achievable with this approach, based on reported data for pharmaceutical and environmental analyses [26] [29].

Table 1: Typical Method Validation Parameters for Residual Solvents Analysis using HS-SPME-GC-MS/MS

| Analyte | Linear Range (ng/mL) | R² | LOD (ng/mL) | LOQ (ng/mL) | Precision (RSD%) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | 10 - 5000 | >0.995 | 3 | 10 | 2.5 | 98.5 |

| Chloroform | 5 - 2000 | >0.998 | 0.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 102.3 |

| Hexane | 20 - 5000 | >0.993 | 5 | 15 | 4.2 | 95.8 |

| Ethyl Acetate | 10 - 4000 | >0.996 | 2 | 7 | 2.8 | 99.1 |

| Methanol | 50 - 8000 | >0.990 | 15 | 50 | 5.5 | 97.2 |

Comparison of SPME Fiber Coatings

The choice of fiber coating is critical for method sensitivity. The following table compares the performance of different commercially available and advanced SPME fiber coatings for extracting common residual solvents, based on recent research [26] [28].

Table 2: Comparison of SPME Fiber Coatings for Residual Solvents Analysis

| Fiber Coating | Target Solvents | Relative Extraction Efficiency | Thermal Stability (°C) | Reusability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR/PDMS/DVB | Broad range, VOCs | High | 270 | ~100 cycles |

| PDMS/DVB | Polar solvents | High | 260 | ~100 cycles |

| PDMS (100 µm) | Non-polar solvents | Medium | 280 | ~100 cycles |

| MWCNT–IL/PANI | Broad range | Very High | >300 | >150 cycles [28] |

| MOF-based Coatings | Tunable selectivity | High to Very High | Varies (200-350) | Under evaluation |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of SPME-GC-MS/MS for residual solvents analysis requires specific reagents and materials. The table below details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SPME Fibers | Extraction and concentration of target solvents from sample headspace. | CAR/PDMS/DVB, 50/30 µm; DVB/PDMS, 65 µm [26] [29]. |

| Internal Standards | Correction for variability in extraction and ionization; essential for accurate quantification. | Deuterated solvents (e.g., Acetone-d6, Chloroform-d). |

| Calibration Standards | Construction of quantitative calibration curves for each target analyte. | Certified reference materials (CRMs) of target solvents in appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol). |

| GC-MS/MS System | Separation (GC) and highly selective and sensitive detection (MS/MS) of extracted solvents. | GC system (e.g., Agilent 7890A) coupled to a triple quadrupole MS (e.g., Agilent 7010B) [29]. |

| Headspace Vials | Containment of sample during equilibration and extraction, preventing loss of volatiles. | 20 mL amber glass vials with PTFE/silicone septa caps [29]. |

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Carryover: If carryover is observed between runs, increase the injector desorption time and/or temperature. Ensure the fiber is properly conditioned after each analysis. Using a fiber with higher thermal stability can mitigate this issue.

- Poor Precision (High RSD): Ensure consistent sample volume, vial size, equilibration time, and temperature. Check the integrity of the vial septum and make sure the vial is properly sealed. Automated systems greatly improve precision over manual injection.

- Low Recovery: Verify the fiber coating is appropriate for the target solvents. Increase equilibration and/or extraction time. For very volatile solvents, gastight-SPME has shown superior sensitivity [26].

- Matrix Effects: The complex lipid matrix of liposomes can influence headspace partitioning. The use of internal standards is the most effective way to compensate for these effects. For severe suppression or enhancement, the standard addition method may be necessary.

- Fiber Lifespan: Exposure to high temperatures and aggressive matrices can degrade the fiber coating over time. Monitor performance with quality control standards. Advanced materials like MWCNT–IL/PANI offer extended lifespan [28].