Spectroscopic Reflectometer vs. Smartphone Analysis: A Performance Evaluation for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of traditional spectroscopic reflectometers against emerging smartphone-based analytical platforms, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science.

Spectroscopic Reflectometer vs. Smartphone Analysis: A Performance Evaluation for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of traditional spectroscopic reflectometers against emerging smartphone-based analytical platforms, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical science. It explores the foundational principles of both technologies, detailing key methodologies and applications in areas such as thin-film characterization and biosample analysis. The content systematically addresses common technical challenges and optimization strategies, including the use of machine learning and advanced components. A critical validation and comparative analysis assesses the performance, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of each platform, offering evidence-based insights to guide instrument selection for research and point-of-care applications.

Core Principles: Understanding Spectroscopic Reflectometry and Smartphone Analysis

Spectroscopic reflectometry is a powerful, non-destructive optical metrology technique primarily used for thin film characterization and wafer analysis. This method measures the intensity of light reflected from a sample across a broad wavelength range to determine critical parameters such as film thickness, refractive index (n), and extinction coefficient (k) [1]. Unlike single-wavelength methods, spectroscopic reflectometry analyzes full spectral data, enabling precise modeling of multilayer thin films and complex material stacks essential for semiconductor research, photonics, and materials science.

The fundamental operating principle relies on optical interference effects. When light strikes a thin film structure, some portion reflects from the top surface while the remainder transmits into the film and reflects from subsequent interfaces [2]. The light waves from these multiple reflections recombine, creating constructive and destructive interference patterns that vary with wavelength [2]. This generates a unique reflectance spectrum signature that serves as a fingerprint containing information about the physical and optical properties of the film structure. Advanced modeling algorithms then fit theoretical models to this measured spectrum to extract precise layer thicknesses and optical constants with high accuracy [2] [1].

Technology Comparison: Traditional Reflectometry vs. Smartphone-Based Analysis

The following table provides a systematic comparison of traditional spectroscopic reflectometry and emerging smartphone-based analysis methods across key performance and technical parameters.

Table 1: Performance and Technical Comparison between Spectroscopic Reflectometry and Smartphone-Based Analysis

| Parameter | Traditional Spectroscopic Reflectometry | Smartphone-Based Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | Semiconductor process control, thin film R&D, high-precision metrology [3] [1] | Point-of-care diagnostics, water quality monitoring, field-based chemical sensing [4] |

| Typical Thickness Range | 50 nm to 1.5 μm (transparent films); up to tens of μm with NIR extension [5] [3] | Not standardized; highly dependent on assay and phone capabilities |

| Measurement Spot Size | 3.5 μm to 40 μm (selectable) [5]; as small as 5 μm [3] | Varies significantly with attachment optics; generally larger |

| Acquisition Time | < 5 seconds [5]; milliseconds possible with high-intensity lamps [3] | Seconds to minutes, depending on processing |

| Wavelength Range | 190-1700 nm (standard); extendable from Deep UV (190 nm) to Mid-IR (25 μm) [2] [3] | ~400-700 nm (limited by camera filters and built-in optics) [4] |

| Key Strengths | High accuracy, model-based analysis, wide thickness range, small spot size, standardized protocols [5] [1] | Portability, low cost, user-friendly interfaces, data processing apps [4] |

| Key Limitations | High equipment cost, benchtop footprint, requires operator expertise | Limited spectral resolution, qualitative/semi-quantitative results, device-dependent variability [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

Standardized Protocol for Traditional Spectroscopic Reflectometry

The standard methodology for traditional spectroscopic reflectometry involves a precise sequence of steps to ensure reliable and reproducible data.

- Sample Preparation: Samples, typically silicon wafers, are spin-coated with a thin film material such as a photoresist. To enhance adhesion, the wafer may be pre-coated with an adhesion promoter like hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) [6].

- Instrument Calibration: The reflectometer is calibrated using a reference sample with known absolute reflectance to account for the efficiency of optical components like mirrors and diffraction gratings. This establishes a tool factor for accurate absolute reflectance measurement [6].

- Data Acquisition: The sample is placed on a stage, and a broadband light source (e.g., Xenon lamp) illuminates the sample. The reflected light intensity is measured across the operational wavelength spectrum (e.g., 190-1700 nm) at normal incidence [2] [3]. For mapping thickness variations, this is repeated at multiple locations using an automated stage.

- Model Fitting: The measured reflectance spectrum is compared to a theoretical model based on the Fresnel equations. The model simulates the reflectance for a proposed film stack. The layer thickness in the model is varied iteratively by a fitting algorithm until the simulated spectrum matches the measured data, minimizing the error [2] [6].

- Result Validation: The calculated thickness is often validated against a reference measurement from another technique, such as spectroscopic ellipsometry, to confirm accuracy [6].

Typical Protocol for Smartphone-Based Colorimetric Analysis

Smartphone-based methods follow a different protocol, prioritizing field deployment over laboratory precision.

- Assay Preparation: A paper-based test strip is impregnated with a colorimetric reagent specific to the target analyte (e.g., for peroxide, pH, or metal ions) [4]. For liquid samples, the solution is placed in a vial or cuvette.

- Hardware Setup: A custom 3D-printed cradle is often attached to the smartphone to hold the sample. This cradle is designed to control ambient light and maintain consistent distance and angle between the camera and the sample [4]. In some setups, the phone's built-in LED flash is used as a light source [4].

- Image Capture: A photograph of the test strip or liquid sample is taken under controlled conditions. Multiple images may be captured for averaging to reduce noise.

- Image Processing: The image is processed within a mobile application. The region of interest is selected, and its color data is extracted. The image is typically converted from the native RGB color space to other spaces like HSV or L*a*b* for better correlation with analyte concentration [4].

- Quantitative Analysis: The concentration is determined using a calibration curve that relates the extracted color parameters (e.g., Red, Green, Blue intensity, or Hue value) to known concentrations. This curve may be pre-loaded or established during validation. Advanced approaches may use machine learning models trained on a database of reference images [4].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reflectometry-Based Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Amplified Photoresist (CAR) | Light-sensitive polymer used to create patterned thin films for semiconductor lithography. | Spin-coated on silicon wafers to study latent image formation and thickness changes after EUV exposure and baking [6]. |

| Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) | Adhesion promoter applied to substrate surfaces before resist coating. | Ensures uniform adhesion of photoresist to silicon wafers, preventing delamination during processing [6]. |

| Colorimetric Test Strips | Paper-based sensors impregnated with reagents that change color upon interaction with a target analyte. | Used with smartphone analysis for rapid, qualitative detection of chemicals in water, saliva, or other fluids [4]. |

| Silicon Wafer | Standard semiconductor substrate providing a smooth, reflective surface for thin film deposition and analysis. | Serves as the base substrate for depositing various thin films (dielectrics, resists) for characterization via reflectometry [6]. |

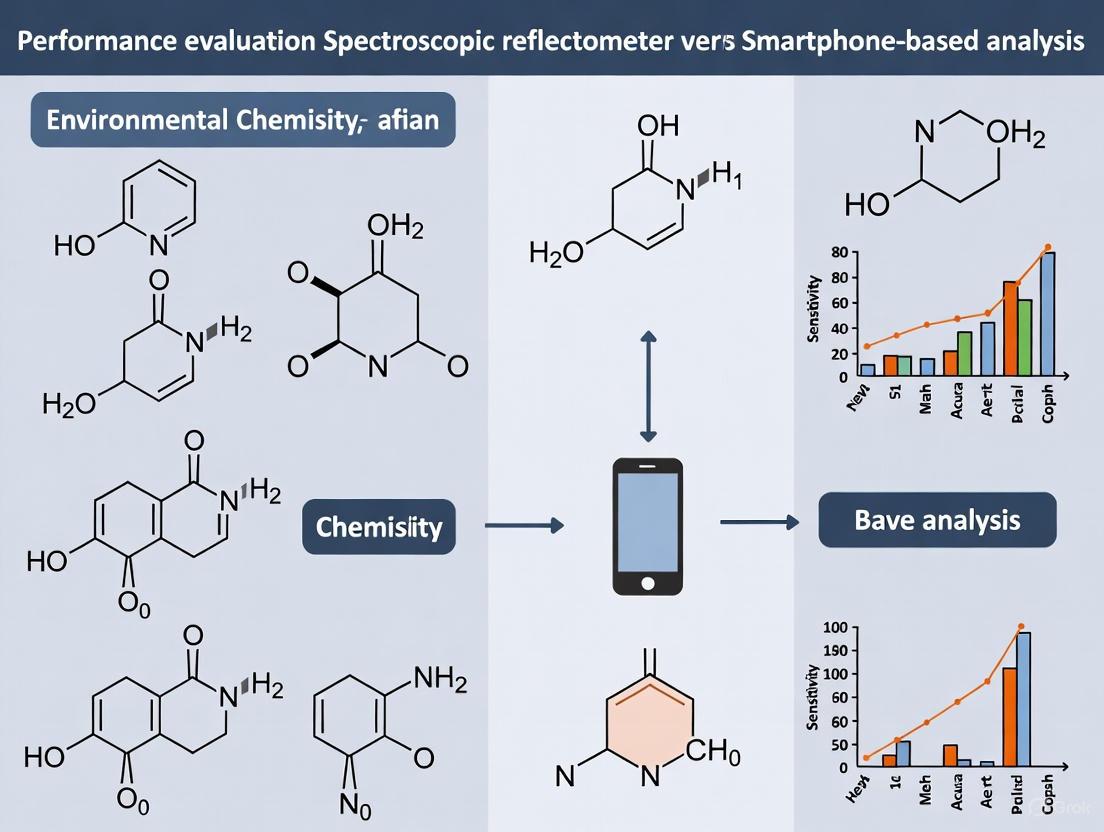

Visualization of Methodologies

The diagrams below illustrate the core principles and workflows of the two analytical methods.

Fundamental Operating Principle of a Spectroscopic Reflectometer

Diagram 1: Reflectometer operating principle.

The diagram shows the core principle of a traditional spectroscopic reflectometer. A broadband light source illuminates the thin film sample at normal incidence. The reflected beams from the air-film and film-substrate interfaces create an interference pattern, which is captured by the spectrometer. This pattern is analyzed to determine the film's properties [2].

Typical Setup for a Smartphone-Based Colorimetric Analysis System

Diagram 2: Smartphone analysis setup.

This diagram visualizes a typical configuration for smartphone-based analysis. A 3D-printed cradle ensures consistent positioning of the colorimetric assay (test strip or vial) relative to the smartphone's camera and light source. An image is captured and processed by a dedicated mobile application, which outputs a quantitative result based on color information [4].

The performance evaluation between traditional spectroscopic reflectometry and smartphone-based analysis reveals a clear dichotomy defined by precision versus accessibility. Traditional reflectometers are engineered for high-precision, quantitative metrology in controlled environments, offering unparalleled accuracy for film thickness and complex optical constants [5] [1]. Their ability to model multilayer film stacks with spot sizes as small as 3.5 μm makes them indispensable for semiconductor fabrication and advanced materials research [3] [5].

Conversely, smartphone-based systems excel in portability, cost-effectiveness, and field deployment. They leverage ubiquitous technology and user-friendly interfaces to provide rapid qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis for point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food quality control [4]. However, their quantitative capabilities are constrained by limited spectral resolution, inherent image processing algorithms within smartphone cameras that corrupt linear data, and significant device-to-device variability [4].

In conclusion, the choice between these technologies is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific requirements. For rigorous R&D and semiconductor process control where nanometer-scale accuracy is non-negotiable, traditional spectroscopic reflectometry remains the definitive tool. For rapid, portable analysis in resource-limited settings where approximate results can drive critical decisions, smartphone-based analysis offers a transformative approach. The ongoing development in smartphone sensors and analysis algorithms will continue to narrow the performance gap for specific applications, but these technologies will likely remain complementary pillars in the broader landscape of analytical instrumentation.

The modern smartphone has evolved beyond a communication device into a sophisticated analytical platform that integrates powerful processors, high-resolution cameras, and numerous sensors. This transformation has enabled the development of portable, cost-effective scientific instruments, particularly in the field of optical spectroscopy [7]. Smartphone-based spectroscopic platforms leverage embedded functional components including complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) cameras, light emitting diode (LED) flashlights, ambient light sensors (ALS), and graphical user interfaces to perform analytical measurements traditionally confined to laboratory settings [7]. These systems provide unprecedented opportunities for point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and resource-constrained applications, challenging conventional benchtop instruments in terms of accessibility while raising questions about performance parity [7] [4].

Within this context, this comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance capabilities of smartphone-based analytical platforms against conventional spectroscopic reflectometers. We present experimental data across multiple parameters, detailed methodologies for key experiments, and analytical frameworks to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in understanding the appropriate applications and limitations of each technology.

Technical Comparison: Smartphone Platforms vs. Conventional Spectroscopic Reflectometers

Performance Specifications and Capabilities

Table 1: Performance comparison between smartphone-based analytical platforms and conventional spectroscopic reflectometers

| Parameter | Smartphone-Based Platforms | Conventional Spectroscopic Reflectometers |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | Typically 400-700 nm (limited by camera IR filters) [7] | 400-1000 nm or broader [8] |

| Resolution | 5-15 nm [9] [8] | <1 nm to 5 nm [1] |

| Measurement Accuracy | 5-9.2% error in controlled studies [10] [8] | >99% with regular calibration [1] |

| Portability | Excellent (integrated platform) [9] | Limited (benchtop systems) [1] |

| Cost | Low (utilizes existing hardware) [9] [4] | High (specialized components) [9] [11] |

| Primary Applications | Point-of-care diagnostics, field testing, educational use [7] [4] | Semiconductor fabrication, thin-film characterization, R&D [1] [11] |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate (often single samples) [4] | High (automated multi-sample systems) [11] |

| User Expertise Required | Moderate to low [4] | High (technical operation and interpretation) [1] |

Market Position and Adoption Trends

Table 2: Market analysis and application focus for spectroscopic tools

| Aspect | Smartphone-Based Platforms | Conventional Spectroscopic Reflectometers |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2025) | Part of portable spectrometer market ($2.67B) [12] | $1.2B (reflectometry specific) [11] |

| Projected Growth (2025-2035) | 9.2% CAGR [12] | 8.2% CAGR [11] |

| Dominant Regional Market | North America (42.8% share) [12] | Asia Pacific [11] |

| Primary End Users | Healthcare, environmental monitoring, food safety [12] [4] | Semiconductor, electronics, solar energy [11] |

| Key Growth Driver | Point-of-care testing adoption [7] [12] | Semiconductor industry complexity [11] |

| Price Point | $250-500 (attachment cost) [9] | $Thousands to tens of thousands [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Smartphone-Based Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Hemoglobin Measurement

Objective: To quantify hemoglobin concentration using a smartphone-based G-Fresnel spectrometer [8].

Materials and Equipment:

- Smartphone with custom spectrometer attachment (G-Fresnel element)

- Broadband tungsten halogen lamp (HL-2000-HP, Ocean Optics)

- Fiber optic probe (6 illumination fibers around 1 collection fiber)

- Tissue phantoms with known hemoglobin concentrations

- Polystyrene microspheres (1-μm diameter) for scattering simulation

- Reflectance standard (Spectralon SRS-99)

Procedure:

- System Calibration:

- Wavelength calibration using emission lines from calibration lamp

- Establish pixel-to-wavelength correlation with linear fitting

- Measure background spectrum with ambient light for subtraction

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare tissue phantoms with hemoglobin concentration range of 5.39-36.16 μM

- Add polystyrene microspusters to simulate tissue scattering properties

- Use magnetic stirrer to maintain uniform suspension during measurements

Data Acquisition:

- Bring fiber probe tip in contact with phantom surface

- Set integration time to 3.6 seconds using smartphone application

- Capture diffuse reflectance spectra from 430-630 nm (covers hemoglobin absorption peaks)

- Subtract background spectrum from all measurements

- Measure reference standard immediately after phantom measurements

Data Analysis:

- Use Monte Carlo inverse model of reflectance to extract absorption (μa) and reduced scattering (μs') coefficients

- Calculate hemoglobin concentrations from absorption data

- Compare results with benchtop spectrometer (Ocean Optics USB4000) measurements

Validation: The smartphone spectrometer achieved a mean error of 9.2% in hemoglobin concentration measurement compared to reference values [8].

Oblique Incidence Reflectometry Using Smartphone Platform

Objective: To determine optical absorption (μa) and reduced scattering coefficients (μs') of biological samples using smartphone-based oblique incidence reflectometry (OIR) [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- Smartphone with CMOS camera

- Laser diode module (incidence angle: 15°-60°)

- Calibrated colorimetric dishes for sample holding

- Software for image processing and histogram equalization

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Position laser diode at known oblique angle to sample surface

- Ensure smartphone camera is perpendicular to sample plane

- Use diffuse reflectance standards for system validation

Image Acquisition:

- Capture diffuse reflectance distribution without ambient light

- Apply histogram equalization to pre-process images

- Use relative light intensity rather than absolute values

Data Processing:

- Determine diffuse reflectance center shift from incident point

- Calculate μa and μs' using inverse model fitting

- Compare results with laboratory OIR system using scientific CCD camera

Performance: The smartphone OIR system achieved measurement errors below 5% compared to laboratory systems for milk, apple, and human skin samples [10].

Figure 1: Methodological workflow comparison between smartphone-based and traditional spectroscopic analysis approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for smartphone-based spectroscopic experiments

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| G-Fresnel Optical Element | Combines grating dispersion and Fresnel lens focusing in single element | Miniaturized spectrometer design [8] |

| Tissue Phantoms | Simulate optical properties of biological tissues | Method validation for biomedical applications [8] |

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Provide controlled scattering properties in phantoms | Simulating tissue scattering [8] |

| Spectralon Reflectance Standards | Provide known reflectance reference for calibration | System calibration and validation [8] |

| Biomarker Assays (ELISA) | Provide specific molecular recognition | Medical diagnostics and immunoassays [4] |

| Paper-Based Microfluidic Chips | Enable controlled fluid transport without external power | Point-of-care chemical and biological sensing [4] |

| Optical Fiber Bundles | Transport light to/from sample to smartphone | Flexible sampling configurations [4] |

| 3D-Printed Enclosures | Provide customized mounting and alignment | System integration and portability [9] [4] |

Performance Analysis and Technical Considerations

Key Performance Metrics in Experimental Settings

Resolution and Accuracy: Smartphone spectrometers demonstrate resolution capabilities between 5-15 nm, sufficient for many biological and chemical applications but inferior to research-grade instruments [9] [8]. The G-Fresnel smartphone spectrometer achieved approximately 5 nm resolution across 400-1000 nm range, enabling identification of hemoglobin absorption peaks [8]. In quantitative measurements, errors typically range from 5-9.2%, representing a significant achievement for portable systems but falling short of laboratory-grade precision requirements in semiconductor or pharmaceutical quality control [10] [8].

Sensitivity and Dynamic Range: The built-in CMOS cameras in smartphones exhibit good sensitivity in the visible range (400-700 nm) but limited response in near-infrared regions due to inherent IR blocking filters [7]. This restriction impacts applications requiring NIR characterization. Dynamic range varies significantly across smartphone models, with higher-end devices incorporating computational photography techniques that can both enhance and complicate quantitative measurements [4].

Figure 2: Architecture of a smartphone-based spectroscopic platform showing integration of embedded and external components

Application-Specific Performance Evaluation

Biomedical Applications: In hemoglobin concentration measurement, smartphone spectrometers demonstrated sufficient accuracy for screening applications with 9.2% mean error compared to reference methods [8]. For oblique incidence reflectometry measurements of optical properties in biological tissues, smartphone systems achieved less than 5% error for determining absorption and scattering coefficients [10].

Food Quality and Environmental Monitoring: Smartphone spectrometers successfully monitored fruit ripeness through chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, showing strong correlation with destructive firmness tests [9]. The detection of chlorophyll fluorescence signals at 680 nm and 730 nm enabled non-destructive ripeness assessment across apple varieties, demonstrating practical field applicability [9].

Material Characterization: While smartphone systems show promise for educational and preliminary investigations, conventional spectroscopic reflectometers maintain dominance in industrial applications requiring precise thin-film measurements [1] [11]. The semiconductor industry relies on traditional systems for sub-nanometer thickness measurements and complex multilayer characterization [1].

Smartphone-based analytical platforms represent a transformative approach to spectroscopic analysis, offering unprecedented portability, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility. The experimental data demonstrates their capability to achieve measurement errors below 10% for multiple applications, making them suitable for screening, field testing, and educational purposes. However, conventional spectroscopic reflectometers maintain superior accuracy, precision, and spectral range for research and industrial applications requiring the highest measurement confidence.

The future development trajectory suggests increasing convergence between these platforms. Smartphone systems are benefiting from improved camera technologies, advanced computational methods, and accessory standardization. Conventional instruments are incorporating connectivity and usability features inspired by consumer technology. For researchers and drug development professionals, selection between these platforms involves careful consideration of accuracy requirements, operational environment, and resource constraints, with both technologies offering complementary capabilities for modern analytical challenges.

This guide provides an objective comparison of performance between traditional spectroscopic reflectometers and emerging smartphone-based analysis platforms, focusing on the core metrics critical for research and drug development.

Spectroscopic reflectometry is a key analytical technique for non-destructive characterization of materials. It operates by analyzing the intensity of light reflected from a sample across a range of wavelengths. The resulting spectrum provides rich information, enabling researchers to determine critical properties such as film thickness, refractive index (n), and extinction coefficient (k) with high precision [13]. In fields like drug development and semiconductor manufacturing, the accuracy and reliability of these measurements are paramount.

The emergence of smartphone-based spectroscopic platforms represents a significant trend toward portable, cost-effective point-of-care diagnostics [7]. These systems leverage the sophisticated cameras and processing power of modern smartphones to perform spectroscopic analysis. While they offer remarkable accessibility, their performance must be critically evaluated against established laboratory standards. This comparison focuses on the four fundamental metrics—resolution, sensitivity, dynamic range, and accuracy—that collectively define the capability and limitations of any spectroscopic system.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance indicators for traditional benchtop reflectometers and smartphone-based systems, based on data from commercial specifications and peer-reviewed research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Spectroscopic Reflectometers and Smartphone-Based Systems

| Performance Metric | Spectroscopic Reflectometers (Benchtop) | Smartphone-Based Spectroscopic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Coverage | 200 nm – 1000 nm (UV to NIR) [13] | 400 nm – 1000 nm (Vis to NIR) [8] [7] |

| Spectral Resolution | Not explicitly stated, but designed for high-precision n & k measurement [13] | ~5 nm (G-Fresnel smartphone spectrometer) [8] |

| Sensitivity | High sensitivity for measurements on rough or curved surfaces [13] | Capable of detecting single DNA molecules (with a 41-MP camera) [7] |

| Dynamic Range | Film thickness range: 2 nm – 100 µm [13] | Demonstrated for hemoglobin concentration measurement [8] |

| Measurement Accuracy | Precise height and tilt adjustment for reliable n and k [13] | 9.2% mean error in hemoglobin concentration vs. commercial spectrometer [8] |

| Key Applications | Microelectronics, optoelectronics, life science, thin-film analysis [13] | Point-of-care diagnostics, cancer screening, water monitoring, food quality control [8] [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The validity of any performance comparison rests on the robustness of the underlying experimental data. The following are detailed methodologies from key studies that have directly or indirectly compared these platforms.

Smartphone Spectrometer Performance Validation

A seminal study developed a smartphone-based G-Fresnel spectrometer and validated its performance for hemoglobin measurement, a common biomedical application [8].

1. System Configuration:

- Spectrometer: A custom-built G-Fresnel spectrometer was connected to a smartphone via a microUSB port for control and power. The device achieved a resolution of approximately 5 nm across a 400-1000 nm range [8].

- Optical Setup: A diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) system was assembled using a broadband tungsten halogen lamp and a specialized fiber optic probe. This probe consisted of six illumination fibers surrounding a single collection fiber, which delivered the diffusely reflected light to the smartphone spectrometer [8].

2. Sample Preparation (Tissue Phantoms):

- Liquid tissue phantoms were prepared to simulate human tissue.

- Hemoglobin (100% oxidized) served as the absorber, with concentrations titrated between 5.39 and 36.16 μM.

- Polystyrene microspheres (1-µm diameter) were suspended in the solution to simulate the scattering properties of biological tissue [8].

3. Measurement and Analysis Protocol:

- The fiber probe tip was placed in contact with the phantom surface.

- A magnetic stirrer ensured a uniform suspension during measurement.

- The diffuse reflectance spectrum of each phantom was measured using the smartphone spectrometer with a 3.6-second integration time.

- A background spectrum (ambient light) was subtracted from all measurements.

- A reflectance standard (Spectralon) with known flat reflectivity was measured for calibration.

- The same phantoms were measured using a commercial benchtop DRS system for comparison.

- A Monte Carlo (MC) inverse model was used to extract the absorption coefficient (µa) and reduced scattering coefficient (µs') from the measured spectra in the 430-630 nm range [8].

4. Outcome: The smartphone spectrometer system achieved a mean error of 9.2% in quantifying hemoglobin concentration, a performance deemed comparable to the commercial benchtop spectrometer [8].

Benchtop Reflectometer Measurement Protocol

Commercial benchtop systems, such as the SENTECH RM series, follow rigorous methodologies for high-precision measurement [13].

1. System Calibration:

- The instrument is calibrated using standards with known reflectance properties.

- The sample platform is adjusted for precise height and tilt to ensure normal incidence and optimal signal collection [13].

2. Measurement Process:

- The reflectance of the sample is measured across the entire spectral range (e.g., 200-1000 nm).

- For mapping applications, an automated x-y stage moves the sample to measure multiple points with spot sizes as small as 80 µm [13].

3. Data Analysis:

- The measured reflectance spectrum is analyzed using expert software (e.g., SENTECH FTPadv EXPERT).

- The software fits the data to physical models based on the Fresnel equations to determine thickness and optical constants (n and k).

- An extensive built-in material database and dispersion models are used to improve the accuracy of the fitting process [13].

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The fundamental workflow for spectroscopic reflectometry is similar across platforms, though the implementation details differ significantly. The diagram below illustrates the core process for a smartphone-based system.

Diagram 1: Smartphone-Based Analysis Workflow

In contrast, the workflow for a benchtop reflectometer is more integrated and automated, as shown below.

Diagram 2: Benchtop Reflectometer Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions based on the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Experiments

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Human Hemoglobin | Acts as a key absorber in tissue phantoms to simulate blood content and validate biomedical applications. | Used as the sole absorber in liquid tissue phantoms for smartphone spectrometer validation [8]. |

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Simulate the scattering properties of biological tissue in phantom studies. | 1-µm diameter spheres were used to simulate tissue scattering in hemoglobin measurements [8]. |

| Reflectance Standard | Provides a reference with known, stable reflectivity for system calibration, ensuring measurement accuracy. | Spectralon SRS-99 was used due to its flat reflectivity across wavelengths [8]. |

| Tungsten Halogen Lamp | A broadband light source essential for generating light across visible and near-infrared spectra. | Used in the DRS setup for smartphone-based measurements [8]. |

| Optical Fiber Probe | Delivers light to the sample and collects the reflected signal; configuration (e.g., source-detector separation) affects sampling depth. | A 6-around-1 fiber configuration was used for diffuse reflectance measurements [8]. |

| Software with Material Database | Enables modeling and fitting of reflectance data to extract physical parameters (n, k, thickness). | SENTECH FTPadv EXPERT software with a built-in material library is used for analyzing reflectometry data [13]. |

Spectroscopic reflectometry, a established workhorse in laboratory analysis, is facing an emerging challenger. Smartphone-based spectroscopy, once a novel concept, is rapidly evolving into a credible analytical tool. This transformation is driven by advancements in smartphone camera technology, processing power, and the development of sophisticated peripheral attachments and algorithms. Where traditional benchtop spectrometers offer precision and reliability, smartphone-based platforms promise unprecedented portability, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility for point-of-care diagnostics and field analysis [7]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two paradigms, framing their performance within the broader thesis of evaluating analytical tools for modern research and drug development. We will dissect their capabilities through experimental data, detailed methodologies, and a clear analysis of their respective strengths and limitations.

Market Context and Technological Evolution

The market dynamics underscore a significant shift towards portability. The global mobile and portable spectrometers market, valued at USD 2.47 Billion in 2025, is projected to cross USD 5.96 Billion by 2035, growing at a CAGR of over 9.2% [12]. This growth is fueled by factors such as the surge in mass spectrometry analysis by medical professionals, rising requirements for food contamination detection, and increasing demand for soil testing [12].

The core of this emerging technology leverages the smartphone's embedded components. Modern smartphones integrate sophisticated sensors that can be repurposed for spectroscopy:

- CMOS Cameras: Function as multi-pixel spectral detectors, with resolutions in modern phones reaching 108 megapixels. These sensors have a native sensitivity from about 400 nm to 700 nm, often limited by an built-in infrared filter [7].

- Ambient Light Sensor (ALS): A photodiode with a spectral detection range of 350 nm to 1000 nm, suitable for spectrophotometric applications like absorbance measurements [7].

- Flashlight LED: Serves as a convenient, bright white light source for measurements in the visible domain [7].

- Computational Platform: Provides the processing power for on-device data analysis, visualization, and transmission via custom-developed applications [7] [14].

Table 1: Global Market Outlook for Mobile and Portable Spectrometers

| Attribute | Data |

|---|---|

| Base Year Market Size (2025) | USD 2.47 Billion |

| Forecast Year Market Size (2035) | USD 5.96 Billion |

| Projected CAGR (2026-2035) | 9.2% |

| Largest Regional Market (2035) | North America (42.8% share) |

| Fastest Growing Region | Asia Pacific |

| Key Growth Driver | Surge in mass spectrometry analysis and food safety testing |

Performance Comparison: Bench-Top vs. Smartphone-Based Systems

Objective performance data is crucial for evaluation. The following table and experimental summaries compare key parameters of established laboratory systems and emerging smartphone-based platforms.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Established vs. Smartphone-Based Spectrometers

| Parameter | Established Laboratory Spectrometer | Emerging Smartphone Spectrometer |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | High (Often thousands of dollars) | Low (Under $250 for prototype; smartphone as platform) [14] |

| Portability | Bulky, benchtop | Ultra-portable (e.g., 48g, 88mm x 37mm x 22mm) [14] |

| Power Consumption | High, requires mains power | Minimal, can use smartphone battery [14] |

| Resolution | High (Varies by model) | ~15 nm (Adequate for many applications) [14] |

| Data Acquisition | Requires external computer | Standalone, wireless operation (e.g., Bluetooth) [14] |

| Measurement Error | Laboratory standard | <5% for optical property measurement vs. lab system [10] |

| Typical Applications | High-precision R&D, quantitative analysis | Rapid screening, point-of-care diagnosis, field analysis [7] [14] |

Experimental Validation: Optical Property Measurement

A direct comparative study demonstrated the viability of a smartphone-based oblique incidence reflectometer (OIR) for measuring the optical properties of tissues and materials. The system used a smartphone's camera to capture the spatial distribution of diffuse reflectance from a sample illuminated by a narrow laser beam [10].

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Setup: A laser source was directed at a sample (e.g., human skin, apple, milk) at an oblique angle.

- Imaging: The smartphone camera captured the diffuse reflectance pattern.

- Analysis: A custom algorithm analyzed the shift of the diffuse light center from the incident point to calculate the absorption coefficient (μa) and reduced scattering coefficient (μs') [10].

- Benchmarking: Results were compared against a Laboratory Obliquely Incident Reflectometer (LOIR) equipped with a scientific CCD camera and microscope.

Result: The smartphone-based OIR achieved a measurement error of less than 5% compared to the laboratory setup, confirming its adequacy for rapid, non-invasive assessments in biomedical applications and food quality testing [10].

Experimental Validation: Non-Destructive Ripeness Testing

Another study highlighted the application of a wireless, ultra-portable smartphone spectrometer for non-destructive fruit ripeness testing, a common need in agricultural and food science research [14].

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Device Assembly: A standalone spectrometer chip (256 pixels, 340-780 nm range), UV LED, optical filters, Bluetooth module, and microcontroller were integrated into a 3D-printed housing (48g).

- Measurement: The device measured Chlorophyll Fluorescence (ChlF) emitted from apple skins when excited by UV light. The peak fluorescence intensity at 680 nm (FR) was recorded.

- Correlation: The ChlF data was correlated with destructive firmness tests performed using a penetrometer, the established standard for ripeness [14].

Result: A satisfactory agreement was observed between the decreasing ChlF signal measured by the smartphone spectrometer and the loss of firmness measured by the penetrometer, validating the smartphone device as a rapid, non-destructive alternative for ripeness evaluation [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table details key components and reagents used in developing and deploying smartphone-based spectroscopic platforms, as evidenced in the cited research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Smartphone Spectroscopy

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Smartphone with CMOS Camera | Serves as the core detection unit for capturing spectral or image data. Models with accessible raw data output are preferred [7] [15]. |

| Diffraction Grating or Spectrometer Chip | Disperses light into its constituent wavelengths for spectral analysis. Integrated chips provide higher reliability [14]. |

| LED Light Source (White or UV) | Provides illumination for the sample. The smartphone's built-in flash or an external, powered LED can be used [7] [14]. |

| Optical Filters | Used to select specific excitation wavelengths or block scattered light, crucial for fluorescence measurements [14]. |

| Microcontroller (e.g., Arduino) | Manages analog-to-digital (A/D) conversion, timing, and control of the spectrometer chip and light sources [14]. |

| Color Calibration Card | Critical for colorimetric assays. Used with correction algorithms to standardize color input across different devices and lighting conditions, reducing interference [16]. |

| Custom Mobile Application (App) | Provides the user interface for controlling the device, acquiring data, performing analysis, and displaying results [14] [16]. |

| Standard pH/Biomarker Test Strips | Common biosamples for colorimetric detection in clinical or environmental testing, used to validate the system's analytical performance [16]. |

Implementation Workflows and Data Processing

To achieve reliable results with smartphone-based systems, robust experimental and computational workflows are essential. The following diagrams illustrate key processes.

Assembly and Operation of a Wireless Smartphone Spectrometer

Diagram 1: Wireless Spectrometer Workflow

For colorimetric detection, which relies on the analysis of images, a sophisticated color correction pipeline is often necessary to ensure accuracy across different devices and lighting conditions.

Colorimetric Detection with Correction Algorithm

Diagram 2: Color Correction Pipeline

Critical Analysis and Limitations

Despite their promise, smartphone-based spectrometers are not a panacea and present several challenges that researchers must consider.

- Hardware and Software Variability: A study of over 60 smartphone models revealed significant variation in their out-of-the-box spectral responses. Factors like built-in image post-processing, automatic white balance, and the presence of Bayer filters in camera sensors can introduce inconsistencies and make precise spectral measurements challenging without rigorous calibration [14] [15].

- Colorimetric Challenges: Without a controlled environment, lighting conditions, camera configuration, and camera parameters (ISO, white balance) can drastically affect image-based colorimetric results [16].

- Database and Calibration Dependency: The accuracy of these devices is heavily reliant on the quality of their calibration and reference databases. Maintaining and updating these databases is crucial, and ambiguity in them can lower the quality and accuracy of results [12].

- Inherent Performance Limits: While sufficient for many applications, the resolution (e.g., ~15 nm) and sensitivity of smartphone-based systems may not yet meet the requirements for highly specialized laboratory analyses that demand parts-per-billion detection limits or extreme spectral resolution [14].

The landscape of spectroscopic analysis is broadening. Established benchtop spectrometers remain the gold standard for high-precision, demanding laboratory work. However, emerging smartphone-based platforms have convincingly demonstrated their utility for a wide range of applications where portability, low cost, and rapid analysis are paramount. Experimental data shows that these systems can achieve errors of less than 5% against laboratory standards and successfully perform tasks like non-destructive ripeness testing and optical property measurement [10] [14].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice is no longer a binary one. The decision should be guided by the specific requirements of the task. For core laboratory work requiring the highest accuracy, established systems are indispensable. For field analysis, point-of-care diagnostics, rapid screening, and educational purposes, smartphone-based spectroscopy offers a powerful, accessible, and cost-effective alternative that is rapidly closing the performance gap.

Methods in Practice: From Thin-Film Analysis to Biosensing

Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry for Non-Uniform Thin-Film Characterization

Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry (ISR) has emerged as a critical metrology technique for characterizing non-uniform thin films, especially in semiconductor manufacturing, display technologies, and advanced materials research. This non-destructive optical method measures reflected light intensity across multiple wavelengths to determine film thickness and optical properties with high spatial resolution. The technique is particularly valuable for analyzing films with thickness variations across their surface area, where conventional spot-based measurements prove insufficient [17] [18].

The growing need for precise process control in industrial applications has spurred interest in comparing traditional ISR systems with emerging smartphone-based spectroscopic platforms. While commercial ISR instruments offer high precision and reliability for critical manufacturing environments, smartphone-based systems present opportunities for decentralized, cost-effective measurements in resource-constrained settings. This comparison guide objectively evaluates both approaches within the broader context of performance evaluation for spectroscopic analysis, providing researchers with comprehensive data to inform their technology selection [7] [19].

Fundamental Operating Principles

Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry operates by illuminating a sample with monochromatic light across a broad wavelength range and capturing the resulting interference pattern created by reflections from multiple interfaces within thin film structures. The reflectance spectrum obtained contains characteristic oscillations whose period and amplitude depend on film thickness and optical constants. For non-uniform films, ISR systems acquire this data across numerous points simultaneously, generating detailed thickness maps that reveal area distributions of local thickness variations [1] [17].

The underlying physics is described by the Airy equations for thin film interference, where reflectance (R) can be expressed as:

[R = \left| \frac{r{01} + r{12} \exp(-i2\phi)}{1 + r{01}r{12} \exp(-i2\phi)} \right|^2]

where (r{01}) and (r{12}) are the Fresnel reflection coefficients at the air-film and film-substrate interfaces, respectively, and (\phi) is the phase thickness given by (\phi = kdN1(k)), with (k) representing the wavenumber, (d) the film thickness, and (N1) the refractive index of the film [20].

Critical Technical Considerations for Non-Uniform Films

Characterizing non-uniform thin films presents unique challenges that ISR addresses through specialized approaches. Traditional model-based algorithms often struggle with local minima in error functions, particularly for thick films where multiple thickness values can produce similar reflectance spectra. Model-free methodologies have been developed to overcome these limitations by exploiting linear relationships between reflectance extrema and optical path length, enabling direct thickness determination without iterative fitting processes [20].

For reliable non-uniformity characterization, ISR systems must maintain high spatial resolution while preserving spectral accuracy. This requires precise optical designs that minimize stray light and ensure proper focusing across the measurement area. The technique can determine area distributions of local thickness independently from dispersion parameters when appropriate optical models are employed, as demonstrated with SiOx films where thickness non-uniformity was characterized without corresponding variations in optical constants [21].

Commercial ISR Systems vs. Smartphone-Based Platforms

Performance Comparison

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Commercial ISR Systems | Smartphone-Based Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 50×50 μm to 500×500 μm [17] | Limited by camera optics, typically >100 μm [7] |

| Thickness Accuracy | ±0.4 nm demonstrated for 1188.8 nm CNx/SiOy film [22] | ~9.2% error in hemoglobin concentration measurement [23] |

| Spectral Range | Adjustable, typically 210-780 nm [20] [1] | ~400-1000 nm (limited by IR filter) [23] [7] |

| Spectral Resolution | Adjustable down to several nm [17] | ~5 nm in 400-1000 nm range [23] |

| Measurement Speed | High throughput, suitable for in-line monitoring [1] | 3.6 seconds integration time demonstrated [23] |

| Computational Approach | Model-based and model-free algorithms [20] | Typically simplified models or calibration curves [19] |

| Computational Throughput | Model-free methods offer 92.6% improvement [20] | Varies with smartphone processing capability [7] |

Table 2: Application-Specific Performance Characteristics

| Application | Commercial ISR Performance | Smartphone Platform Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Semiconductor/Display Manufacturing | PR thickness measurement in 1-2 μm channels [17] | Not demonstrated in HVM environments |

| Biomedical Sensing | Limited direct application | 91.3% accuracy for vitamin B12 quantification [19] |

| Non-Uniformity Characterization | Complete mapping of SiOx films [21] | Primarily uniform samples or single-point measurements |

| Repeatability (GR&R) | 76.9% improvement in equipment variation [20] | Higher variance compared to benchtop systems [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard ISR Protocol for Non-Uniform Films

Commercial ISR systems follow a structured measurement approach optimized for non-uniform thin films:

System Configuration: A high-brightness Xe-lamp source with monochromator provides tunable monochromatic light. Wavelength range and resolution are adjusted according to film properties [17].

Data Acquisition: The monochromatic light illuminates the sample, and a 2D detector captures images at each wavelength. This process repeats across the selected spectral range, building a data cube of intensity values versus wavelength and position [17].

Focusing: A built-in focusing system with piezoelectric motor ensures optimal focus across the measurement area, critical for high spatial resolution [17].

Model Application: The same analysis engine as spectroscopic ellipsometry and reflectometry is used, allowing sophisticated optical models to be applied consistently across metrologies [17].

Thickness Mapping: For each pixel or region, film thickness is determined either through model-based fitting or model-free approaches, generating complete thickness maps [21].

Smartphone-Based Protocol

Smartphone spectroscopic platforms employ modified approaches suited to their hardware limitations:

Device Assembly: A G-Fresnel spectrometer containing a complete spectrograph system connects to the smartphone via microUSB port. The assembly includes an input slit, transmission G-Fresnel element (600 lines/mm grating with Fresnel lens pattern), and CMOS image sensor [23].

Spectral Acquisition: Light from the sample is delivered via fiber optic probe to the spectrometer. The Android application controls integration time (typically 3.6 seconds) and initiates measurements [23].

Data Processing: Raw Bayer pattern images are converted to greyscale spectral images through summation of red, green, and blue pixel values. Column summation produces final one-dimensional spectral data [23].

Reference Measurements: Background spectra accounting for ambient light are subtracted from both sample and reference measurements (e.g., Spectralon reflectance standard) [23].

Analysis: Simplified models or calibration curves convert spectral data to material properties, with some implementations using Monte Carlo inversion models for parameter extraction [23] [19].

Workflow Visualization

ISR Measurement Workflow: This diagram illustrates the standardized protocol for characterizing non-uniform thin films using Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry, from sample preparation through final thickness mapping.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Critical Components for Experimental Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Calibration and verification of measurement accuracy | Spectralon SRS-99 (LabSphere) for diffuse reflectance [23] |

| Thin Film Samples | Method validation and system characterization | SiOx films for non-uniformity studies [21], CNx/SiOy mixtures [22] |

| Optical Components | Light manipulation and spectral dispersion | G-Fresnel devices (600 lines/mm grating + Fresnel lens) [23] |

| Light Sources | Sample illumination across spectral range | High-brightness Xe-lamps (commercial ISR) [17], tungsten halogen lamps (smartphone systems) [23] |

| Detectors | Light detection and spectral image capture | CCD cameras with zoom objectives [22], CMOS sensors in smartphones [7] |

| Software Algorithms | Data processing and thickness extraction | Model-free algorithms exploiting reflectance extrema [20], Monte Carlo inverse models [23] |

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

Performance Trade-offs and Limitations

Commercial ISR systems demonstrate superior performance in precision manufacturing environments, with thickness accuracy reaching sub-nanometer levels and spatial resolution enabling characterization in micron-scale channels [22] [17]. These systems effectively address the challenge of local minima in error functions through model-free methodologies that provide 92.6% improvement in computational throughput while enhancing measurement repeatability [20]. However, their high cost and operational complexity present barriers for resource-constrained settings or field applications.

Smartphone-based platforms offer compelling advantages in accessibility and cost-efficiency, with demonstrated capability for quantitative analysis of biological and chemical samples [23] [19]. Their performance in controlled laboratory settings approaches that of benchtop systems for specific applications, with accuracy up to 91.3% reported for nutrient quantification. Nevertheless, limitations in spatial resolution, spectral range, and measurement precision restrict their utility for advanced thin film characterization, particularly for highly non-uniform or multilayer structures [7].

Future Research Directions

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with both commercial and smartphone-based platforms represents a promising avenue for enhancing measurement accuracy and simplifying operation. For commercial ISR, research focus should address remaining challenges in fleet matching and model optimization for emerging materials [20]. For smartphone platforms, development of specialized attachments and advanced computational methods could bridge current performance gaps while maintaining accessibility advantages [7] [19].

Technology Selection Guide: This decision tree illustrates the appropriate application contexts for commercial ISR versus smartphone-based platforms based on precision requirements and operational constraints.

Imaging Spectroscopic Reflectometry represents a mature, high-performance solution for non-uniform thin film characterization in precision manufacturing environments, while smartphone-based spectroscopic platforms offer accessible alternatives for field measurements and resource-constrained settings. Commercial ISR systems provide unmatched spatial resolution, measurement accuracy, and robustness for industrial process control, particularly in semiconductor and display manufacturing. Smartphone-based platforms, though limited in precision, demonstrate capability for quantitative analysis in biomedical and environmental applications.

The choice between these approaches depends fundamentally on the specific application requirements, with commercial systems addressing needs for sub-nanometer accuracy and high spatial resolution, while smartphone platforms provide cost-effective solutions where ultimate precision is not critical. Future research should focus on bridging the performance gap between these platforms while developing hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both technologies for comprehensive thin film characterization across diverse operational environments.

Smartphone-Based Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Hemoglobin Measurement

The quantification of hemoglobin concentration is a fundamental diagnostic procedure for identifying and managing conditions such as anemia and various blood-related disorders. Traditional methods rely on invasive blood draws, which are resource-intensive, require clinical settings, and can pose risks of infection. In recent years, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive alternative for measuring tissue chromophores like hemoglobin. Concurrently, the ubiquity and advanced hardware of smartphones have created new opportunities for developing portable, cost-effective point-of-care diagnostic tools. This guide performs a performance evaluation of smartphone-based DRS systems for hemoglobin measurement against traditional spectroscopic reflectometers, providing an objective comparison based on experimental data, methodologies, and key technical specifications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Smartphone-Based DRS vs. Traditional Spectroscopic Reflectometers

The following tables summarize the key performance metrics and characteristics of smartphone-based systems compared to other spectroscopic approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Hemoglobin Measurement Technologies

| Technology / System | Measurement Accuracy / Error | Correlation with Gold Standard (r/R²) | Key Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smartphone-based DRS (G-Fresnel Spectrometer) [23] [24] | Mean error: 9.2% (tissue phantoms) | N/A | Resolution: ~5 nm (400-1000 nm range); Comparable to benchtop spectrometer performance. |

| Smartphone Biosensor (Multi-wavelength LED) [25] | RMSE: 9.04 | Adjusted R²: 0.880 | Utilizes L*a*b* color space and multi-wavelength (660, 810, 900, 970, 1050 nm) analysis. |

| Handheld DRS System (Neonatal Application) [26] | N/A | r = 0.80 (Hemoglobin) | Designed for simultaneous bilirubin and hemoglobin quantification in neonates. |

| Wearable DRS System [27] | 95% LOA: -1.98 to 1.98 g/dL | r = 0.90 | Uses 6-wavelength LEDs and photodiodes; Neural network for optical property recovery. |

| Machine Learning (XGBoost-SMA on PPG) [28] | N/A | R²: 0.997 | Extreme accuracy on a 68-subject dataset using optimized machine learning models. |

Table 2: Technical and Operational Characteristics Comparison

| Feature | Smartphone-Based DRS Systems | Traditional Benchtop/Wearable DRS | Commercial Spectroscopic Reflectometers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portability | High (leveraging smartphone platform) [7] | Moderate (Handheld) [26] to High (Wearable) [27] | Low (Benchtop systems) [29] |

| Cost | Largely reduced, uses smartphone's CPU, memory, and camera [25] [7] | Moderate (custom hardware) [26] [27] | High (specialized equipment) [29] |

| Spectral Range | e.g., 400-1000 nm (G-Fresnel) [23] | 450-600 nm (Handheld DRS) [26] | Up to 190-2100 nm (e.g., HORIBA ellipsometers) [29] |

| Light Source | Integrated multi-wavelength LED module [25] or external broadband lamp with fiber probe [23] | Custom white light LEDs [26] or specific wavelength LEDs [27] | Integrated, calibrated broadband source [29] |

| Detection | Smartphone CMOS camera [25] [7] [23] | Mini-spectrometers [26] or photodiodes [27] | High-sensitivity, dedicated detector arrays [29] |

| Data Modeling | L*a*b* color space transformation [25], Monte Carlo inversion [23] | Modified-two-layered photon diffusion model [26], Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [27] | Sophisticated optical models (e.g., for thin films) [29] |

| Primary Advantage | Extreme portability and low cost; massive potential for POC use. | Balanced performance and design-specific advantages (e.g., wearability). | High precision, sensitivity to ultrathin films, wide spectral range. [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the performance data, below are the detailed methodologies from key studies.

Smartphone-Based Biosensor with Multi-Wavelength LEDs

This protocol outlines the method for a highly integrated smartphone-based sensor [25].

- Device Setup: A custom multi-wavelength LED module (660 nm, 810 nm, 900 nm, 970 nm, 1050 nm) and a 3D-printed fixture were developed to interface with a smartphone (Huawei Mate 20 Pro). The fixture minimizes motion artifacts, and the module is controlled by a custom PCBA.

- Data Collection: The participant's finger is placed on the module. Each LED is illuminated sequentially for 20 seconds, resulting in a 100-second video recording. The study involved 24 participants (12 healthy, 12 anemic).

- Signal Processing: A region of interest (ROI) of 1000x1000 pixels is selected from each video frame. The average RGB values are extracted. Due to high noise in the B and G channels, the signal is transformed from RGB to the CIE L*a*b* color space. The 'a*' parameter, which correlates with skin redness and blood volume, is used for final hemoglobin quantification via multiple linear regression.

Smartphone G-Fresnel Spectrometer for DRS

This protocol describes a system where a smartphone controls an external spectrometer [23] [24].

- System Configuration: A miniature G-Fresnel spectrometer (400-1000 nm, ~5 nm resolution) is connected to a smartphone via a microUSB port. A fiber-optic probe, with six illumination fibers around one collection fiber, is used. The light from a broadband tungsten halogen lamp is delivered via the illumination fibers.

- Phantom Measurement: Tissue-simulating phantoms were prepared with human hemoglobin (5.39 to 36.16 µM) and 1-µm polystyrene microspheres (scatterers). The probe tip was placed in contact with the phantom surface, and a magnetic stirrer ensured homogeneity.

- Data Analysis & Hemoglobin Retrieval: The diffuse reflectance spectrum is measured. A Monte Carlo (MC) inverse model of light transport in tissue is used to extract the absorption coefficient (µa) and reduced scattering coefficient (µs') from the measured spectrum. The hemoglobin concentration is derived from the recovered absorption spectrum.

Wearable DRS System with Neural Networks

This protocol is for a self-contained wearable device [27].

- Hardware: The wearable device features a sensor board with six custom LEDs (500 nm, 521 nm, 541 nm, 561 nm, 572 nm, 599 nm) and photodiodes at two source-detector separations (1 mm and 2 mm).

- Measurement: The device is placed on the skin (e.g., wrist). LEDs are sequentially activated, and the reflected light intensity at the two distances is recorded by the photodiodes.

- Analysis with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): An ANN, trained on a vast dataset generated using Monte Carlo simulations of light transport in tissue, is used. The ANN takes the measured diffuse reflectance at the two source-detector separations as input and directly outputs the absorption and reduced scattering coefficients of the skin. The absorption spectrum is then fitted with the known absorption spectra of hemoglobin and other chromophores to determine concentration.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and technological approaches of the three main systems discussed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for DRS Hemoglobin Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Microspheres | Scatterers that simulate the scattering properties of biological tissue in tissue-simulating phantoms. | Used at 1-µm size to mimic tissue scattering in phantom studies for system validation [23]. |

| Human Hemoglobin (from Sigma-Aldrich) | The primary absorber of interest, used to create phantoms with known concentrations for calibration and testing. | Titrated in water with microspheres to create phantoms with concentrations from 5.39 to 36.16 µM [23]. |

| Spectralon Reflectance Standard | A material with a flat, high, and known reflectance spectrum across wavelengths. Used for system calibration. | Placing the probe tip on the standard provides a reference spectrum to account for the system's response [23]. |

| Multi-wavelength LED Modules | Custom light sources containing specific wavelengths that target the absorption peaks of hemoglobin and other chromophores. | A module with 660, 810, 900, 970, and 1050 nm LEDs helps differentiate HbO2, Hb, and water absorption [25]. |

| G-Fresnel Optical Element | A miniaturized diffractive optical element that combines the functions of a grating and a Fresnel lens, enabling compact spectrometer design. | The core component of the smartphone-connected spectrometer, providing dispersion and focusing [23]. |

| Fiber-Optic Probe (e.g., 6-around-1) | Delivers light to the sample and collects the diffusely reflected light. A common geometry for DRS measurements. | The central fiber collects light, while the six surrounding fibers deliver illumination from the source [23]. |

The performance evaluation clearly indicates that smartphone-based DRS systems present a viable and highly promising alternative to traditional spectroscopic methods for hemoglobin measurement. While commercial spectroscopic reflectometers and dedicated benchtop DRS systems offer high precision and broad spectral capabilities, smartphone-based platforms excel in portability, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility, achieving medically relevant accuracy with correlation coefficients (R²) up to 0.88 and errors comparable to benchtop standards. The integration of advanced computational methods—such as Monte Carlo models, Artificial Neural Networks, and optimized machine learning algorithms—is crucial for compensating for the hardware limitations of smartphones and has enabled some systems to achieve exceptional predictive accuracy (R² > 0.99). For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of technology depends on the specific application requirements: traditional systems for maximum analytical performance in a lab setting, and smartphone-based systems for scalable, affordable point-of-care diagnostics and field deployment.

Colorimetric and Luminescence Sensing with Smartphone Detectors

The rapid evolution of smartphone technology has catalyzed a paradigm shift in optical sensing, enabling the development of sophisticated analytical tools that leverage the embedded components of these ubiquitous devices. Modern smartphones integrate high-resolution cameras, powerful processors, and various sensors that can be repurposed for scientific applications, particularly in colorimetric and luminescence sensing. These smartphone-based detection systems offer a compelling alternative to conventional laboratory equipment by providing portability, cost-effectiveness, and point-of-care capabilities without compromising analytical performance. Research demonstrates that carefully optimized smartphone-based colorimetry can achieve measurement ranges comparable to absorbance-based models while exhibiting inherent resilience to environmental variables when appropriate color spaces are utilized [30].

The fundamental components enabling smartphone-based optical sensing include complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) cameras, light-emitting diode (LED) flashlights, ambient light sensors (ALS), and universal serial bus (USB) ports for powering external components. The CMOS camera serves as the primary detector, with modern smartphones featuring sensors up to 108 megapixels that employ pixel-binning techniques to enhance light capture in low-light conditions essential for fluorescence-based assays [7]. The integration of these consumer-oriented components with custom-developed algorithms and applications has positioned smartphones as versatile platforms for spectroscopic analysis, including absorption, reflectance, and fluorescence measurements across various biomedical, environmental, and food safety applications [31].

Performance Comparison: Spectroscopic Reflectometers vs. Smartphone-Based Analysis

To objectively evaluate the capabilities of smartphone-based detection systems against established laboratory instruments, we compare their key performance characteristics across multiple parameters. The following tables summarize quantitative data from experimental studies, highlighting the respective advantages and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Overall Performance Characteristics of Spectroscopic Reflectometers and Smartphone-Based Detection Systems

| Performance Parameter | Benchtop Spectroscopic Reflectometer | Smartphone-Based Detection System |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | <0.1 nm (varies by model) | ~0.21-5 nm [31] [24] |

| Wavelength Range | 190-2500 nm (typical) | 350-1000 nm [7] [24] |

| Measurement Modes | Reflectance, transmittance | Transmission, reflection, fluorescence [31] |

| Portability | Limited (benchtop installation) | High (compact, 3D-printed housing) [31] |

| Cost | High (>$10,000) | Low (<$500 with accessories) |

| Analysis Time | Minutes (including sample preparation) | Minutes to seconds [31] |

| Required Expertise | Technical training needed | Minimal training required |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Specific Smartphone-Based Sensing Applications

| Application | Detection Mechanism | Analyte | Limit of Detection | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine Detection | Fluorescence quenching | Caffeine | 2.58 μM | 0-200 μM | [31] |

| Hemoglobin Measurement | Diffuse reflectance | Hemoglobin | 9.2% mean error (concentration) | 5.39-36.16 μM | [24] [8] |

| miRNA Detection | Luminescence quenching | miR-892b | 0.32 pM | Not specified | [32] |

| Bioluminescence Detection | Low-light detection | Pseudomonas fluorescens M3A | ~10⁶ CFU/mL | Not specified | [33] |

| General Colorimetry | CIELAB color space | Various | Comparable to absorbance-based | Broader than absorbance-based | [30] |

The data reveal that smartphone-based systems achieve performance metrics that are comparable to conventional instruments for specific applications. The G-Fresnel smartphone spectrometer demonstrates a resolution of approximately 5 nm across a wavelength range of 400-1000 nm, suitable for diffuse reflectance spectroscopic measurement of hemoglobin [24] [8]. More advanced smartphone spectrometer designs achieve even higher resolution of 0.21 nm/pixel in the visible range (350-750 nm) while maintaining multiplexing capabilities for transmission, reflection, and fluorescence measurements [31]. The primary limitations of smartphone-based detection remain in the restricted wavelength range compared to commercial spectrometers and potential sensitivity to ambient conditions, though the latter can be mitigated through color space optimization as demonstrated in studies utilizing the CIELAB color space [30].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Smartphone-Based Colorimetric Sensing with Optimal Color Space

Objective: To demonstrate housing-free, illumination-invariant colorimetric detection using smartphone cameras with optimized color space selection.

Methodology: Researchers evaluated quantification performance using monotonal shadings of colors with spectral compositions covering a wide range of visible spectra. Color coordinates were extracted from automatically selected regions of interest (ROI) using a custom algorithm. The performance of RGB color space was compared against CIELAB color space, specifically the a* and b* chromatic coordinates [30].

Key Findings: Models based on RGB space proved highly sensitive to illumination changes, limiting their reliability. In contrast, the CIELAB color space exhibited inherent resistance to illumination changes due to the concept of equichromatic surfaces, which provides a theoretical basis for designing illumination-invariant optical biosensors. This approach enabled smartphone-based colorimetry to offer a broader measurement range with limits of detection comparable to absorbance-based models [30].

Multiplexed Smartphone Spectrometer for Fluorescence-Based Caffeine Detection

Objective: To develop a low-cost, portable, and highly multiplexed smartphone-based spectrometer capable of collecting transmission, reflection, and fluorescence spectra for caffeine detection in commercial beverages.

Methodology: A compact 3D-printed housing (120 mm × 40 mm × 107.3 mm) was designed to incorporate optical components including plano-convex cylindrical lenses (f = 20 mm), biconvex lenses (f = 15 mm), diffraction grating (1200 grooves/mm), and multimode optical fiber. The HUAWEI P40 Pro smartphone was used with specific camera settings: exposure time 1/10 for transmission, 1/2 for reflectance, and 1 for fluorescence modes; ISO 50 for transmission, 1600 for reflectance, and 1000 for fluorescence modes [31].

caffeine detection workflow

For caffeine detection, researchers introduced a high signal-to-noise ratio scheme utilizing aspirin and salicylic acid as fluorescent probes. The fluorescence quenching of these probes was found to be linearly related to caffeine concentration. Image processing included pixel-wavelength calibration using 532 nm and 650 nm laser pointers, with intensity values calculated using weighted averages of RGB channels (0.299×R + 0.587×G + 0.114×B) to account for human color perception [31].

Key Findings: The smartphone spectrometer achieved a resolution of 0.21 nm/pixel and successfully detected caffeine concentrations with a limit of detection of 2.58 μM. Recovery rates for commercially available caffeine-containing samples ranged from 98.03% to 105.60%, demonstrating the reliability and stability of the on-site assay [31].

Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Hemoglobin Measurement

Objective: To demonstrate quantitative hemoglobin measurement using a smartphone G-Fresnel spectrometer-based diffuse reflectance spectroscopy system.

Methodology: A miniature visible to near-infrared G-Fresnel spectrometer was developed with complete spectrograph system, connecting to a smartphone via microUSB port for operational control. The system achieved ~5 nm resolution across 400-1000 nm wavelength range. Tissue phantoms were prepared using human hemoglobin as the absorber and 1-μm polystyrene microspheres as scatterers in water, with hemoglobin concentrations ranging from 5.39 to 36.16 μM [24] [8].

hemoglobin measurement system

The fiber probe consisted of 6 multimode fibers surrounding a single central collection fiber (400 μm core size). The tip of the fiber probe was brought into contact with phantom surfaces, with a magnetic stirrer ensuring uniform colloidal suspension. Measurements employed 3.6-second integration time, with background subtraction for ambient light contribution. A Monte Carlo inverse model of reflectance between 430-630 nm was used to extract absorption coefficients (μa(λ)) and reduced scattering coefficients (μs'(λ)) [8].

Key Findings: Proof-of-concept studies yielded a mean error of 9.2% on hemoglobin concentration measurement, comparable to results obtained with a commercial benchtop spectrometer. This performance demonstrates the potential of smartphone-based systems for point-of-care cancer screening applications [24] [8].

Low Light Detection for Bioluminescence Applications

Objective: To maximize the sensitivity of standard smartphone cameras for detecting low-intensity bioluminescence signals.

Methodology: Researchers developed the Bioluminescent-based Analyte Quantitation by Smartphone (BAQS) system, comprising a simple cradle housing the smartphone, sample tube, and collection lens. Noise reduction was achieved through ensemble averaging, which simultaneously lowered background and enhanced signals from emitted photons. Five different smartphone types (both Android and iOS) were evaluated, with the OnePlus One (Android) demonstrating the best performance [33].

Key Findings: The optimal configuration detected luminescence from approximately 10⁶ CFU/mL of Pseudomonas fluorescens M3A bioluminescent reporter, corresponding to ~10⁷ photons/second with 180 seconds of integration time. This sensitivity to single-digit pW radiant flux intensity enables onsite analysis and quantitation of luminescent signals from biological sensing elements [33].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of smartphone-based colorimetric and luminescence sensing requires specific reagents and materials tailored to each application. The following table summarizes key research reagent solutions and their functions in the described experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Smartphone-Based Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin & Salicylic Acid | Fluorescent probes for caffeine detection | Caffeine quantification in beverages [31] |

| Human Hemoglobin | Primary absorber in tissue phantoms | Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy [8] |

| Polystyrene Microspheres (1-μm) | Scattering agents simulating tissue properties | Tissue phantom preparation [8] |

| Rhodamine Dye (R6G) | Fluorescence standard for validation | Spectrometer performance verification [31] |

| Eu-MOF Hybrid | Luminescence quenching platform | miRNA detection (miR-892b) [32] |

| Carboxyfluorescein (FAM) | Fluorescent tag for probe DNA | Luminescent sensing of biomolecules [32] |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens M3A | Bioluminescent reporter | Low light detection validation [33] |

| Spectralon Reflectance Standard | Reference material with flat reflectivity | Diffuse reflectance calibration [8] |

Smartphone-based colorimetric and luminescence detection systems have evolved into sophisticated analytical tools that compete with conventional laboratory instruments across multiple performance parameters. While benchtop spectroscopic reflectometers maintain advantages in absolute resolution and wavelength range, smartphone-based systems offer compelling benefits in portability, cost, and accessibility without sacrificing analytical capability for many applications. The experimental data demonstrate that properly optimized smartphone detection systems can achieve limits of detection, measurement ranges, and accuracy comparable to traditional methods for applications including caffeine quantification, hemoglobin measurement, miRNA detection, and bioluminescence analysis.