Standard Analytical Methods for PFAS in Environmental Waters: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive overview of standard analytical methods for detecting and quantifying per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in environmental waters.

Standard Analytical Methods for PFAS in Environmental Waters: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of standard analytical methods for detecting and quantifying per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in environmental waters. It covers foundational principles of PFAS chemistry and regulation, detailed methodologies including EPA-approved techniques and emerging approaches, troubleshooting for common analytical challenges, and validation protocols for data quality assurance. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals, this review synthesizes current standards and technological advancements to support accurate PFAS monitoring in compliance with stringent global regulations, which now require detection at parts-per-trillion levels and below.

Understanding PFAS: Chemistry, Regulations, and Environmental Significance

PFAS Structural Diversity and Analytical Challenges

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a large class of synthetic chemicals characterized by their exceptional persistence and bioaccumulative potential, earning them the colloquial name "forever chemicals" [1]. The structural diversity of PFAS, encompassing thousands of compounds with varying chain lengths, functional groups, and architectures, presents profound analytical challenges [2] [1]. This application note examines the core aspects of PFAS structural diversity, the subsequent methodological challenges for environmental analysis, and the advanced techniques developed to address them, all within the context of standard analytical methods for environmental waters.

PFAS Structural Diversity and Classification

The term "PFAS" encompasses a vast array of human-made chemicals, all featuring carbon-fluorine bonds, which are among the strongest in organic chemistry, conferring extreme environmental stability [1]. This chemical class can be broadly categorized based on chain length, functional groups, and architectural features.

Table 1: Classification of Select PFAS Compounds

| Category | Representative Compounds | Structural Characteristics | Example CASRN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legacy PFAS (Long-Chain) | Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) | Long perfluoroalkyl chain (C≥7 for PFCAs; C≥6 for PFSAs) [3] | - |

| Emerging PFAS (Short-Chain) | Short-chain PFCAs, Short-chain PFSAs | Shorter perfluoroalkyl chain (C2-C5 for PFCAs; C2-C5 for PFSAs) [3] | - |

| Polyfluoroether Replacements | HFPO-DA (GenX), Nafion Byproduct 2 (NBP2) | Introduction of ether linkages (e.g., -OCF(CF3)CF2-) into the backbone [2] [3] | 13252-13-6 [3] |

| Other Precursors | 6:2 FTS, PFOSA, EtFOSAA | Contain functional groups that can transform into terminal perfluoroalkyl acids [3] | 27619-97-2, 754-91-6, 2991-50-6 [3] |

This structural diversity is further complicated by the presence of linear and branched isomers for many PFAS, which can exhibit different environmental behaviors and toxicological profiles [4] [1]. The shift from legacy long-chain PFAS like PFOA and PFOS to shorter-chain and polyfluoroether-based alternatives has been driven by regulatory actions, but these emerging PFAS often present new and poorly understood analytical and environmental challenges [2] [3].

Analytical Challenges in PFAS Determination

The unique physicochemical properties of PFAS create several significant hurdles for accurate environmental monitoring, particularly at the low parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels required by regulations [1].

Ubiquity and Contamination Control

The widespread use of PFAS in consumer and industrial products means they are ubiquitous in laboratory environments and sampling equipment [5]. Common materials like PTFE (Teflon), found in tubing, vial caps, and instrument components, can be a significant source of background contamination. This necessitates a highly conservative approach to sampling, requiring rigorous空白 procedures and the use of documented PFAS-free materials and water for quality control [4] [5].

Limitations of Targeted Analysis

Targeted methods, such as EPA Methods 533 and 537.1, are designed to detect a specific, predefined list of analytes using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [4] [6]. While highly sensitive and precise for known compounds, these methods are fundamentally static. They cannot identify PFAS outside their target list, leading to an incomplete picture of the total PFAS burden [2]. This is a critical gap, as the vast majority of the thousands of PFAS on the global market are not covered by standard targeted methods [1].

Instrumental and Matrix Challenges

The lack of chromophores or electroactive groups in most PFAS renders traditional optical or electrochemical detection methods ineffective [1]. Furthermore, co-eluting matrix components in complex environmental water samples can cause ion suppression or enhancement during MS analysis, compromising quantitative accuracy [2]. The analysis is also complicated by the diverse chemical nature of PFAS, which includes anionic, neutral, volatile, and high-molecular-weight compounds, making it impossible for a single analytical technique to capture the entire spectrum [2] [1].

Standard Analytical Methods for Environmental Waters

For the analysis of PFAS in water, several methods have been validated and established by regulatory bodies. The following table summarizes the key EPA methods for drinking water and other aqueous media.

Table 2: Standard EPA Analytical Methods for PFAS in Water

| Method | Applicable Matrices | Target Analytes | Key Analytical Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | 25 PFAS [4] | Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) and LC/MS/MS [4] |

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | 18 PFAS [4] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) and LC/MS/MS [4] |

| EPA Method 1633 | Wastewater, Surface Water, Groundwater, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Tissue | 40 PFAS [4] | Isotope Dilution SPE and LC/MS/MS [4] [5] |

| EPA Method 8327 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater | 24 PFAS [4] | Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) using External Standard Calibration [4] |

These methods are prescriptive and must be followed precisely for compliance monitoring under regulations like the UCMR 5 and the PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation [6]. They have been developed with particular attention to accuracy, precision, and robustness through multi-lab validation [6].

Detailed Protocol: Sample Collection and Preparation for PFAS in Water (Based on EPA Method 1633)

Scope: This protocol describes the procedure for collecting, preserving, and shipping aqueous samples for the analysis of PFAS by EPA Method 1633 or equivalent.

1. Pre-Sampling Planning:

- Communication with Laboratory: Consult with the analytical laboratory prior to sampling. Inform them if samples are suspected to be highly contaminated to prevent cross-contamination of laboratory equipment [5].

- Blank Water: Arrange for the laboratory to supply PFAS-free water for the preparation of field blanks. Documentation verifying the water is PFAS-free must be reviewed [5].

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Sample Bottles: Use high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or polypropylene containers that have been verified to be free of PFAS interference. Do not use containers or caps containing fluoropolymers [5].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear powder-free nitrile gloves. Avoid clothing treated with fabric protectors (e.g., Gore-Tex) [5].

- Sampling Equipment: Use materials that have been screened for PFAS (e.g., polyethylene tubing, stainless-steel well pumps). Review Safety Data Sheets (SDSs) for all materials; if PFAS or terms like "fluoro" are listed, do not use them [5].

3. Sample Collection:

- Rinse Procedure: Rinse sample bottles and caps three times with the sample water before collection.

- Preservation: Aqueous samples must be preserved with methanol or ammonium acetate (as specified by the method) and chilled to 2-6°C immediately after collection [5].

- Avoid Contamination: During collection, keep samples covered and away from potential contamination sources such as sunscreen, insect repellent, food, or dust.

4. Quality Control (QC) Samples:

- Field Blanks: Prepare a field blank at a frequency of one per sampling event or per 20 samples, using the PFAS-free water supplied by the laboratory. This blank is used to identify any contamination introduced during sampling or handling [5].

- Trip Blanks: Include a trip blank that remains sealed for the duration of the trip to assess potential contamination during transport.

5. Sample Storage and Shipping:

- Holding Time: Extract samples within 28 days of collection and analyze within 90 days of extraction, as specified in Method 1633 [5].

- Temperature Control: Ship samples on ice or frozen ice packs to maintain a temperature of 2-6°C [5].

Advanced and Emerging Analytical Techniques

To overcome the limitations of targeted analysis, advanced techniques are being developed and implemented.

Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS)

NTA employs HRMS instruments, such as Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (QTOF) or Orbitrap mass spectrometers, to detect both known and unknown analytes in a sample [4] [2]. The high mass accuracy and resolving power of these instruments allow for the tentative identification of previously uncharacterized PFAS. Data can be archived and re-interrogated as new PFAS are identified [4] [2].

Complementary Techniques: GC-MS and Computational Tools

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) plays a crucial role by covering a complementary chemical space to LC-MS, particularly for volatile and semivolatile PFAS, such as fluorotelomer alcohols [1]. It is estimated that less than 10% of known PFAS are amenable to typical LC-MS analysis, highlighting the need for multiple analytical platforms [1].

Advanced computational approaches, such as molecular networking, create visual maps of mass spectral data, clustering structurally related compounds and facilitating the discovery of unknown PFAS within the same chemical family [1]. Software tools like FluoroMatch use algorithms and databases to automatically annotate unknown PFAS features in complex samples by leveraging characteristics like homologous series and characteristic fragmentation [1].

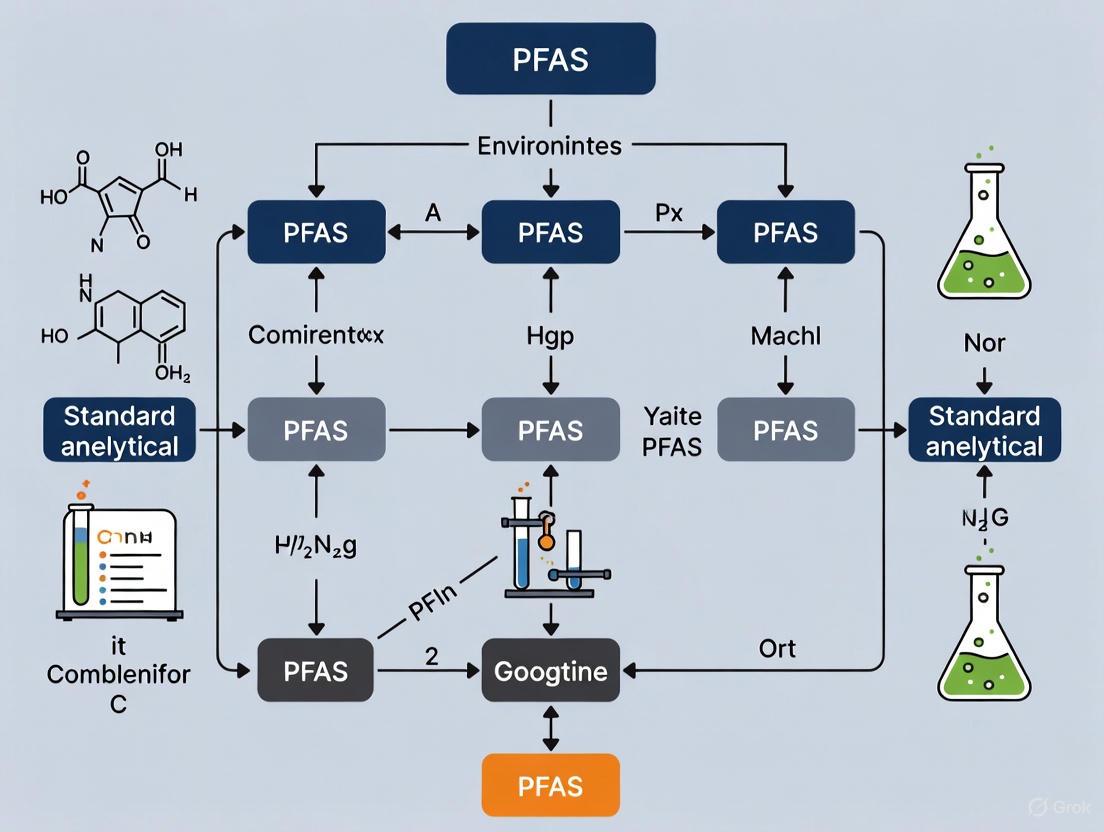

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for a comprehensive PFAS analysis strategy, combining both targeted and non-targeted approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for PFAS Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Chemical standards (e.g., ¹³C- or ¹⁸O-labeled PFAS) added to the sample for quantification via isotope dilution. | Corrects for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation; essential for accurate quantitation in EPA Methods 533 and 1633 [4] [2]. |

| PFAS-Free Water | Ultra-pure water verified to be free of PFAS interference. | Used for preparing calibration standards, blanks, and mobile phases. Must be supplied and documented by the laboratory to ensure data integrity [5]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Sorbent materials (e.g., WAX, C18) used to isolate and concentrate PFAS from water samples. | Selection is method-prescribed (e.g., anion exchange for EPA 533). Must be screened for PFAS background [4] [5]. |

| PFAS Calibration Mix | A solution containing a known concentration of native PFAS analytes. | Used to establish the instrument calibration curve. The mix should be tailored to the target list of the analytical method used [4]. |

| Quality Control Materials | Includes laboratory control samples (LCS), continuing calibration verification (CCV), and blank materials. | Monitors the ongoing performance and accuracy of the analytical method throughout a batch of samples [5]. |

Global Regulatory Landscape and Evolving Compliance Limits

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a large class of synthetic chemicals containing carbon-fluorine bonds, one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry, which confers environmental persistence and leads to their characterization as "forever chemicals" [7]. These compounds have been frequently observed to contaminate groundwater, surface water, and soil, with certain PFAS known to accumulate in people, animals, and plants and cause toxic effects, including reproductive toxicity, cancer, and potential endocrine disruption [7]. The global regulatory landscape for PFAS is rapidly evolving, with significant developments in 2025 establishing stricter compliance limits and more comprehensive monitoring requirements for environmental waters.

This application note provides researchers and scientists with current analytical methodologies, updated regulatory frameworks, and standardized protocols for PFAS detection and quantification in environmental waters. The technical content is framed within the broader context of advancing PFAS research and supporting regulatory compliance through precise, reliable analytical data.

Global Regulatory Framework

United States Regulations

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established a multi-pronged regulatory approach to address PFAS contamination through drinking water standards, comprehensive reporting requirements, and chemical substance reviews.

Drinking Water Standards: The PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) establishes monitoring requirements using EPA Methods 533 and 537.1, which collectively measure 29 PFAS compounds in drinking water [6]. These methods have undergone rigorous multi-lab validation and peer review to ensure accuracy, precision, and robustness for compliance monitoring.

TSCA Reporting Requirements: Under TSCA section 8(a)(7), the EPA requires manufacturers (including importers) of PFAS in any year between 2011-2022 to report data related to chemical identity, production volume, use, exposure, and health effects [8]. The reporting period begins on April 13, 2026, with a final deadline of October 13, 2026, for most manufacturers and importers [9]. Recent amendments have proposed exemptions for de minimis concentrations (≤0.1%), imported articles, byproducts, impurities, and research and development chemicals to reduce regulatory burden while maintaining data quality [10] [8].

Significant New Use Rules: In 2024, the EPA finalized a SNUR preventing the manufacture or processing of 329 inactive PFAS without prior EPA review and risk determination [9]. This rule ensures that any new uses of historically discontinued PFAS undergo rigorous safety evaluation before resumption.

State-Level Regulations: Multiple U.S. states have implemented PFAS restrictions, with significant regulations taking effect in 2025:

- Minnesota (Amara's Law): Restricts sales of products with intentionally added PFAS in carpets, cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics, and other consumer categories [9].

- Colorado: Extends PFAS bans to cosmetics, indoor textile furnishings, and indoor upholstered furniture [9].

- California (AB-1817): Prohibits manufacture and sale of new textile articles containing regulated PFAS, requiring certificates of compliance [9].

European Union Regulations

The European Union has established comprehensive PFAS regulations through multiple legislative frameworks with particularly stringent drinking water standards.

Drinking Water Directive: Effective January 2021, the recast Drinking Water Directive includes a limit of 0.5 µg/L for all PFAS [7]. This grouping approach represents one of the most comprehensive regulatory thresholds globally.

REACH Restrictions: The EU continues to expand PFAS restrictions under REACH, with:

POPs Regulation: Implements Stockholm Convention commitments, having banned PFOA in 2020 and adding PFHxS in August 2023 [7].

Table 1: Global PFAS Regulatory Limits for Water (2025)

| Region/Country | Regulatory Body | PFAS Compounds | Limit (Concentration) | Effective Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | European Commission | All PFAS | 0.5 µg/L | January 12, 2021 [7] |

| United States | U.S. EPA | 29 PFAS (via Methods 533 & 537.1) | Varies by compound | Promulgated with NPDWR [6] |

| United States | Multiple States | PFOA, PFOS, other specific PFAS | Varies by state (ppt levels) | 2024-2025 [9] |

Analytical Methods for PFAS in Environmental Waters

Standardized EPA Methods

EPA has developed and validated specific analytical methods for PFAS detection in various environmental matrices, with particular methods approved for regulatory compliance monitoring.

Table 2: EPA-Approved Analytical Methods for PFAS in Water (2025)

| Method Name | Target Matrices | Number of PFAS | Key Analytical Technique | Prescriptive Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | 18 | Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) + LC/MS/MS | Yes - prohibits changes to preservation, extraction [6] [5] |

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | 25 | Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange SPE + LC/MS/MS | Yes - mandated for NPDWR compliance [6] |

| EPA Method 1633A | Wastewater, Surface Water, Groundwater, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Tissue | 40 | SPE + LC/MS/MS | Multi-media applicability [4] |

| EPA Method 8327 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater | 24 | Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) | External Standard Calibration [4] |

Method Selection Considerations

Researchers must consider several critical factors when selecting analytical methods for PFAS research:

Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Analysis: Most regulatory methods employ targeted analysis using specific analytical standards for known PFAS compounds [4]. Non-targeted analysis using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) can identify unknown PFAS but requires specialized instrumentation and data analysis capabilities [4].

Method Modifications: The EPA notes that "modified EPA PFAS methods" (e.g., "Modified Method 537") have not undergone multi-laboratory validation and are not approved for compliance monitoring under UCMR 5 or the PFAS NPDWR [6]. Researchers should carefully validate any method modifications against project-specific data quality objectives.

Sample Preservation and Holding Times: Approved methods specify strict requirements for sample preservation (typically with ammonium acetate) and holding times to maintain sample integrity [5]. Method 537.1 explicitly prohibits changes to preservation techniques, requiring strict adherence to published protocols [6].

Experimental Protocol: PFAS Analysis in Environmental Waters

The following protocol outlines the standardized methodology for sampling and analysis of PFAS in environmental waters based on EPA-approved methods and technical guidance from ITRC [5].

Sampling Procedures

Diagram 1: PFAS Sampling Workflow

Pre-Sampling Preparation

- Laboratory Coordination: Contact analytical laboratory before sampling to confirm project-specific requirements, obtain PFAS-free water for field blanks, and discuss potential high-concentration samples [5].

- Container Selection: Use only polypropylene or polyethylene containers; avoid fluoropolymer materials [5]. Review Safety Data Sheets for all sampling materials to exclude items containing fluorinated compounds [5].

- Blank Water Verification: Obtain laboratory-certified PFAS-free water for field blanks with documentation verifying PFAS content below detection limits [5].

Field Sampling Collection

- Personal Protective Equipment: Use nitrile gloves and avoid clothing with fabric protectors that may contain PFAS [5].

- Sample Collection: Collect samples without introducing air bubbles, filling containers completely to minimize headspace [5].

- Preservation: Immediately preserve samples with ammonium acetate according to method specifications (e.g., Method 537.1) [5].

- Quality Control: Collect field blanks, trip blanks, and equipment blanks at a frequency of at least 5% of total samples to monitor potential cross-contamination [5].

Sample Handling and Shipping

- Temperature Control: Maintain samples at 2-6°C during transport and storage [5].

- Holding Times: Adhere to method-specified holding times (typically 14 days from collection to extraction for Method 537.1) [5].

- Documentation: Complete chain-of-custody forms noting any potential high-concentration samples or unusual field conditions [5].

Laboratory Analysis Procedures

Diagram 2: PFAS Laboratory Analysis

Sample Preparation

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Process 250 mL water samples through SPE cartridges (typically polystyrene-divinylbenzene) following method-specific protocols [6] [4].

- Extraction: Elute PFAS compounds from cartridges using methanol or ammonium hydroxide in methanol [6].

- Concentration: Concentrate extracts under gentle nitrogen evaporation to near dryness [6].

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute samples in appropriate injection solvent (typically methanol/water mixtures) for LC/MS/MS analysis [6].

Instrumental Analysis

- Chromatographic Separation: Employ reverse-phase liquid chromatography with C18 or similar columns to separate PFAS compounds [6] [4].

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Utilize tandem mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization in negative mode (ESI-) for detection and quantification [6] [4].

- Isotope Dilution Quantification: Use mass-labeled internal standards for precise quantification, correcting for matrix effects and recovery variations [6].

Quality Assurance/Quality Control

- Laboratory Controls: Include method blanks, laboratory control samples, matrix spikes, and duplicate analyses with each batch (typically 20 samples or fewer) [6] [5].

- Continuing Calibration: Verify calibration standards every 12 hours during analysis [6].

- Extraction Efficiency: Monitor surrogate standard recovery for each sample to assess method performance [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PFAS Research in Environmental Waters

| Research Reagent | Function in PFAS Analysis | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Extract and concentrate PFAS from water matrices | Polystyrene-divinylbenzene polymer; 500 mg bed weight [6] |

| Mass-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification via isotope dilution; correct for matrix effects | Carbon-13 or nitrogen-15 labeled PFAS (e.g., ¹³C₄-PFOS, ¹³C₅-PFOA) [6] |

| PFAS-Free Water | Preparation of calibration standards, blanks, and QC samples | Documented PFAS content below method detection limits [5] |

| LC/MS/MS Mobile Phase Additives | Chromatographic separation and ionization efficiency | Ammonium acetate, ammonium hydroxide, methanol, acetonitrile [6] |

| Reference Standards | Target compound identification and quantification | Certified reference materials for 29+ PFAS compounds [6] |

The global regulatory landscape for PFAS continues to evolve rapidly, with 2025 marking significant advancements in both compliance limits and analytical methodologies. Researchers must remain current with updated EPA methods, expanded reporting requirements, and increasingly stringent state and international regulations. The protocols and technical guidance presented in this application note provide a foundation for robust PFAS analysis in environmental waters, supporting both research objectives and regulatory compliance. As PFAS science advances, researchers should anticipate continued method refinements, expanded compound lists, and lower detection limits to address these persistent environmental contaminants.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) constitute a large group of synthetic chemicals characterized by strong carbon-fluorine bonds, which contribute to their exceptional environmental persistence and resistance to degradation [11]. These compounds have seen widespread use in industrial and consumer products since the mid-20th century due to their unique water- and grease-resistant properties [12] [13]. Their structural diversity encompasses both polymeric and non-polymeric classifications, with non-polymeric PFAS further subdivided into perfluoroalkyl (fully fluorinated) and polyfluoroalkyl (partially fluorinated) substances containing various functional groups [13]. The environmental presence of PFAS was first documented in the early 2000s, and since then, numerous studies have detected these persistent compounds in aquatic systems globally, including remote polar regions [12] [13]. This application note examines the sources, transport pathways, and analytical methodologies for PFAS contamination in aquatic environments within the context of standard analytical methods research.

PFAS Chemistry and Classification

PFAS are defined by the presence of at least one fully fluorinated methyl (-CF3) or methylene (-CF2-) group, with no hydrogen, chlorine, bromine, or iodine atoms attached to these carbon atoms [12]. Their amphipathic nature, featuring a hydrophilic functional "head" group and a hydrophobic fluorinated carbon chain "tail," provides emulsifying properties that make them excellent surface-active compounds [12]. The carbon chain length significantly influences their physicochemical behavior, with shorter-chain PFAS (fewer than six carbons for perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids [PFSAs] and fewer than eight for perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids [PFCAs]) exhibiting higher hydrophilicity and water solubility compared to their longer-chain counterparts [13].

Table 1: Major Classes of PFAS and Their Characteristics

| PFAS Class | Representative Compounds | Chain Length Classification | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids (PFCAs) | PFOA, PFNA, PFHxA | Long-chain (≥C8), Short-chain ( | High water solubility, particularly for short-chain |

| Perfluoroalkyl Sulfonic Acids (PFSAs) | PFOS, PFHxS | Long-chain (≥C6), Short-chain ( | Strong surfactant properties, bioaccumulative |

| Fluorotelomer-based Compounds | FTOHs, FTSAs | Variable | Precursors that degrade to PFCAs and PFSAs |

| Perfluoroalkyl Ether Acids | GenX, HFPO-DA | Variable | Emerging replacements for legacy PFAS |

PFAS enter aquatic environments through multiple pathways, with contamination originating from both point and non-point sources. Industrial discharges have historically been significant contributors, particularly from chemical manufacturing facilities producing fluoropolymers and from sites utilizing PFAS in processing [12] [13]. Firefighting activities using aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs) represent another major source, especially at military bases, airports, and fire training facilities [14] [5]. Landfill leachate, wastewater treatment plant effluents, and urban runoff further contribute to the pervasive presence of PFAS in surface water, groundwater, and drinking water sources worldwide [11] [13].

The environmental distribution of PFAS reflects a complex interplay between source strength and transport mechanisms. A recent global compilation of PFAS concentrations in water samples indicates elevated levels in North America, Europe, and Australia, with known AFFF and non-AFFF sources circled as hotspots on spatial distribution maps [13]. Even remote regions like the Arctic and Antarctica show detectable PFAS concentrations, demonstrating the efficiency of long-range transport mechanisms [12].

Transport Pathways and Environmental Fate

The transport of PFAS to aquatic systems occurs through multiple interconnected pathways:

Atmospheric Transport and Deposition

Volatile PFAS precursors undergo long-range atmospheric transport, during which they can be oxidized to form more stable PFAS compounds that deposit onto land and water surfaces via precipitation or dry deposition [12] [15]. This mechanism explains PFAS detection in remote cryosphere environments, where subsequent incorporation into snow and ice creates temporary reservoirs that release PFAS during melting events [12]. Atmospheric modeling approaches, such as EPA's Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model, have been adapted to simulate the transport and fate of PFAS suites, incorporating species-specific physicochemical properties to predict partitioning behavior [15].

Hydrological Transport

Surface runoff and groundwater flow transport PFAS from contaminated sites to receiving water bodies. A study of Lake Ekoln in Sweden demonstrated that river systems (particularly the Fyrisån River) served as the primary PFAS source to the lake, which supplies drinking water to the Stockholm region [16]. Similarly, site-specific differences in PFAS contamination profiles in Massachusetts waterbodies reflected localized source contributions, with Ashumet Pond showing distinct contamination patterns compared to reference sites [17]. Ocean currents and sea spray aerosol formation represent additional transport vectors that contribute to PFAS distribution across marine environments [12].

In-System Transport and Partitioning

Within aquatic systems, PFAS behavior depends on their physicochemical properties, including solubility, vapor pressure, and partitioning coefficients. Longer-chain PFAS tend to associate with particulate matter and sediments, while shorter-chain compounds remain predominantly in the water column [13]. This differential partitioning influences bioavailability, ecosystem exposure, and ultimate environmental fate. Three-dimensional hydrodynamic modeling has proven valuable for simulating PFAS fate and transport in lake systems, capturing seasonal variations that inform drinking water management strategies [16].

Analytical Methodologies for PFAS Detection

Standardized Analytical Methods

EPA has developed validated analytical methods for PFAS detection in various environmental matrices. For drinking water analysis, Methods 533 and 537.1 are approved for compliance monitoring under the PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR), collectively targeting 29 PFAS compounds [6]. These methods employ solid-phase extraction (SPE) followed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), achieving detection limits in the ng/L range [4] [6].

For non-potable water and other environmental media, EPA Method 1633 measures 40 PFAS in wastewater, surface water, groundwater, soil, biosolids, sediment, landfill leachate, and fish tissue [4]. Similarly, Method 8327 determines 24 PFAS in non-drinking water aqueous samples, including groundwater, surface water, and wastewater [4]. These methods underwent rigorous multi-laboratory validation to ensure accuracy, precision, and robustness at low concentration levels.

Table 2: Standardized Analytical Methods for PFAS in Water Matrices

| Method | Applicable Matrices | Target PFAS | Key Technique | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | 25 PFAS | Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange SPE and LC/MS/MS | Validated for UCMR 5 and NPDWR compliance |

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | 18 PFAS | SPE and LC/MS/MS | Includes HFPO-DA (GenX); approved for compliance monitoring |

| EPA Method 1633 | Wastewater, Surface Water, Groundwater, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Tissue | 40 PFAS | SPE and LC/MS/MS | Multi-matrix method developed in collaboration with DOD |

| EPA Method 8327 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater | 24 PFAS | External Standard Calibration and MRM LC/MS/MS | Developed under RCRA for non-potable water |

| ISO 21675 | Water | >30 PFAS classes | SPE and LC/MS/MS | LOQ of 0.0002 mg/L or lower for most listed PFAS |

Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Analysis

Targeted analysis methods are applicable to specific defined sets of known analytes, using analytical standards for quantification. These methods only measure analytes on the predetermined list and cannot retrospectively identify additional compounds [4]. In contrast, non-targeted analysis employs high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify both known and unknown analytes in a sample. This approach allows for suspect screening against compound libraries and can discover novel PFAS, with data storage enabling retrospective analysis as new compounds are identified [4].

Sampling Considerations and Quality Assurance

PFAS sampling requires heightened rigor to avoid cross-contamination and achieve the necessary accuracy and precision for defensible project decisions [5]. Critical considerations include:

- Equipment and Supplies: Many sampling materials can potentially contain PFAS. A conservative approach excludes materials known to contain target PFAS, with review of Safety Data Sheets to identify fluorinated compounds [5].

- Blank Samples: Field and equipment blanks are needed in greater frequency and volume than for other analyses due to the potential for ambient PFAS contamination and low action levels [5].

- Sample Preservation and Holding Times: Methods specify requirements for sample containers, preservation (typically refrigeration), and holding times (generally 14 days for water samples) to maintain sample integrity [5].

- PFAS-Free Water: Water used for field quality control blanks must be supplied by the analytical laboratory with documentation verifying it is PFAS-free, defined as below project-specific thresholds [5].

Experimental Protocols

Water Sampling Protocol for PFAS Analysis

This protocol outlines procedures for collecting surface water samples for PFAS analysis using EPA Method 1633 or equivalent approaches:

Pre-sampling Preparation:

- Obtain PFAS-free water from the analytical laboratory for field blanks

- Document all sampling materials and equipment, reviewing SDS sheets to exclude fluorinated materials

- Prepare decontamination station using PFAS-free water and isopropanol

- Pre-label sample containers with unique identifiers

Sample Collection:

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (nitrile gloves, polyethylene aprons)

- Collect samples in polyethylene or polypropylene containers per method specifications

- Avoid sampling equipment containing fluoropolymers (e.g., PTFE)

- Collect field replicates (at least 10% of samples) and trip blanks (at least one per sampling event)

Sample Preservation and Shipment:

- Refrigerate samples at 4°C immediately after collection

- Maintain chain-of-custody documentation

- Ship samples to laboratory within 24 hours of collection

- Ensure laboratory analysis begins within 14-day holding time

Analytical Quality Control Protocol

Laboratory analysis should incorporate these quality control elements:

Initial Demonstration of Capability:

- Establish method detection limits (MDLs) for each target analyte

- Demonstrate precision and accuracy through replicate analyses

- Verify calibration linearity over the working range

Ongoing Quality Control:

- Analyze laboratory control samples with each batch

- Include continuing calibration verification standards

- Monitor internal standard responses for each analysis

- Perform matrix spike and matrix spike duplicate analyses

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PFAS Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPE Cartridges | WAX (Weak Anion Exchange) or Carbon-based | Extraction and concentration of PFAS from water matrices | Compatible with EPA Methods 533, 537.1, and 1633; provides clean-up and pre-concentration |

| LC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity triple quadrupole mass spectrometer | Separation, detection, and quantification of target PFAS | MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) mode provides selectivity and sensitivity at ng/L levels |

| Analytical Standards | Isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., ^13C- or ^18O-labeled PFAS) | Quantification via isotope dilution mass spectrometry | Corrects for matrix effects and recovery variations; essential for accurate quantification |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium acetate/ammonium hydroxide in methanol and water | LC-MS/MS mobile phase for chromatographic separation | Maintains pH and promotes ionization; specific compositions vary by method |

| PFAS-Free Water | Laboratory-certified blank water | Preparation of standards, blanks, and method blanks | Must be documented as PFAS-free; typically supplied by analytical laboratory |

| Sample Containers | Polyethylene or polypropylene | Sample collection and storage | Avoid fluoropolymer-containing materials; pre-cleaned to minimize contamination |

Understanding the complex sources and pathways of aquatic PFAS contamination requires integrated approaches combining rigorous sampling protocols, sensitive analytical methods, and sophisticated modeling tools. The transport mechanisms—spanning atmospheric, hydrological, and in-system processes—distribute PFAS far from original sources, necessitating comprehensive assessment strategies. Standardized EPA methods (533, 537.1, and 1633) provide validated approaches for generating comparable data across studies and monitoring programs. Continued method development remains essential, particularly for addressing analytical challenges posed by short-chain PFAS and transformation products. This foundation supports informed risk assessment and management strategies targeting PFAS contamination in global water resources.

Health and Ecological Risks Driving Analytical Needs

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a large class of synthetic chemicals containing thousands of compounds, characterized by extremely persistent environmental contamination and documented risks to human and ecological health [18]. Often called "forever chemicals," PFAS are linked to numerous adverse health outcomes including kidney and testicular cancer, liver and kidney damage, changes in hormone and lipid levels, and harm to the nervous and reproductive systems [19]. Their extensive use in consumer, commercial, and industrial products for stain, water, and fire resistance has led to global contamination of water resources [20].

The environmental persistence and low (parts-per-trillion) health-based advisory levels for PFAS like PFOA and PFOS create critical analytical challenges. This necessitates highly sensitive, selective, and robust methods capable of detecting these contaminants at trace levels across diverse water matrices—from finished drinking water to complex industrial wastewater [5]. This application note details the standardized analytical methodologies and emerging techniques developed to meet these demanding analytical needs for PFAS in environmental waters.

Regulatory Framework and Standardized Methods

In response to the significant health risks posed by PFAS, regulatory agencies have established stringent drinking water standards. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set legally enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels for six PFAS, acknowledging there is no safe level of exposure to PFOA and PFOS [20] [19].

Table 1: EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulation for PFAS (2024)

| Compound | MCLG (Health-Based Goal) | MCL (Enforceable Level) |

|---|---|---|

| PFOA | Zero | 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt) |

| PFOS | Zero | 4.0 ppt |

| PFHxS | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| PFNA | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| HFPO-DA (GenX) | 10 ppt | 10 ppt |

| Mixtures of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, PFBS | 1 (unitless Hazard Index) | 1 (unitless Hazard Index) |

Compliance monitoring for these regulations requires the use of specific, validated analytical methods. The EPA has developed and approved two primary methods for analyzing PFAS in drinking water, which are mandatory for compliance monitoring under the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) and the PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) [6].

Table 2: Standardized EPA Analytical Methods for PFAS in Water

| Method | Target Matrices | Scope | Key Analytes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | 18 PFAS | Includes HFPO-DA (GenX) |

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | 25 PFAS | Includes short-chain PFAS |

| EPA Method 1633A | Wastewater, Surface Water, Groundwater, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Landfill Leachate, Fish Tissue | 40 PFAS | Most comprehensive method for non-potable water |

| EPA Method 8327 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater | 24 PFAS | For non-drinking water applications |

| EPA Method 1621 | Aqueous Matrices | Adsorbable Organic Fluorine (AOF) | Non-targeted screening for organofluorines |

For non-potable water matrices under the Clean Water Act, EPA Method 1633A has emerged as the most comprehensive standardized procedure. It can test for 40 PFAS compounds in wastewater, surface water, groundwater, soil, biosolids, sediment, landfill leachate, and fish tissue [21]. While not yet nationally mandated for CWA compliance until formal rulemaking is complete, the EPA recommends its use for individual National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits to ensure consistent data quality [21].

Detailed Analytical Protocols

Protocol for Drinking Water Analysis: EPA Method 533

Principle: This method determines trace concentrations of PFAS in drinking water using isotope dilution anion exchange solid phase extraction (SPE) and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The isotope dilution technique ensures high accuracy by accounting for analyte losses during sample preparation [6] [4].

Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Container: 250 mL high-density polyethylene (HDPE) or polypropylene (PP) bottle.

- Preservative: Add 1 mL of 10% (w/v) sodium azide solution to the sample bottle prior to shipment to inhibit microbial activity. Adjust to pH ≥ 9 using ammonium hydroxide (e.g., 250 µL of 28–30% NH₄OH per 250 mL sample).

- Holding Time: 28 days from collection to extraction. Extracted samples must be analyzed within 28 days of extraction [5].

Sample Preparation (Solid Phase Extraction):

- Sample Loading: Load 250 mL of preserved water sample onto a conditioned weak-anion exchange SPE cartridge (e.g., Waters Oasis WAX).

- Cartridge Conditioning: Condition cartridge with 5 mL of 0.1% NH₄OH in methanol followed by 5 mL of methanol and 5 mL of reagent water. Maintain wetness.

- Interference Removal: After loading, wash with 5 mL of 25 mM acetate buffer (pH 4) to remove interferences.

- Analyte Elution: Elute PFAS analytes with 5 mL of 0.1% NH₄OH in methanol into a polypropylene tube.

- Concentration: Evaporate the eluate to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen at 40°C. Reconstitute the residue in 500 µL of 1:9 (v/v) methanol/water mixture, vortex mix, and transfer to an LC autosampler vial for analysis.

Instrumental Analysis (LC-MS/MS):

- Chromatography: Reverse-phase LC column (e.g., C18). Mobile phase A: 10 mM ammonium acetate in water. Mobile phase B: Methanol. Use a gradient elution from 10% B to 100% B over 20 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Tandem mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ESI) in negative mode. Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) is used for detection and quantification, monitoring two specific transitions per analyte.

Quality Control: The method requires laboratory-fortified blanks, laboratory-fortified matrix samples, internal standards, and initial and ongoing demonstration of capability to ensure precision and accuracy [6].

Protocol for Non-Potable Water Analysis: EPA Method 1633A

Principle: This method is applicable to a wide range of aqueous and solid environmental samples. It uses solid phase extraction (for aqueous samples) or liquid extraction (for solid samples) followed by LC-MS/MS analysis [21].

Sample Collection for Aqueous Matrices:

- Container: 250 mL or 1 L HDPE or PP bottle.

- Preservation: Refrigerate at ≤ 6°C. For non-drinking water matrices, preserve with 1 mL of 10% sodium azide and adjust to pH ≥ 9 with ammonium hydroxide.

- Holding Time: 28 days to extraction for aqueous samples; 14 days to extraction for soil, sediment, and biosolids.

Sample Preparation for Aqueous Samples:

- Filtration: Filter the sample if necessary using a glass fiber filter.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add isotope-labeled internal standards to the sample.

- Solid Phase Extraction: Use a weak-anion exchange SPE cartridge. Condition with methanol and reagent water. Load sample, wash, and elute with methanol containing 0.1% NH₄OH.

- Concentration and Reconstitution: Concentrate the eluate under nitrogen, and reconstitute in a methanol/water mixture for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Instrumental Analysis (LC-MS/MS):

- Similar to Method 533 but optimized for a broader range of 40 PFAS analytes and more complex matrices. Requires careful calibration and quality control checks specific to the sample matrix (e.g., wastewater vs. groundwater).

Workflow Diagram: Targeted PFAS Analysis in Environmental Waters

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for the targeted analysis of PFAS in water samples, from collection to final reporting.

Advanced and Emerging Methodologies

Non-Targeted Analysis and Suspect Screening

While standardized methods like 533 and 1633A are essential for regulatory compliance, they are limited to a specific set of known PFAS (targeted analysis). To address the vast number of unknown PFAS, non-targeted analysis (NTA) using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is employed [4].

- Liquid Chromatography-HRMS (LC-HRMS): The most common NTA approach, capable of identifying known suspects and discovering unknown PFAS not included in targeted lists. HRMS data can be archived and re-analyzed as new PFAS are identified [4] [22].

- Gas Chromatography-HRMS (GC-HRMS): An underutilized but complementary technique to LC-HRMS, particularly useful for volatile and semi-volatile PFAS (e.g., fluorotelomer alcohols, acrylates) and for identifying transformation products from processes like incineration [22]. A 2023 study developed a custom GC-HRMS database and workflow for 141 diverse PFAS, significantly advancing NTA capabilities for these compounds [22].

Addressing Analytical Gaps: Short-Chain and Ultrashort-Chain PFAS

A significant limitation of conventional LC-MS/MS methods is the poor separation and detection of short-chain (C4-C7) and ultrashort-chain (≤C3) PFAS. These highly polar compounds often co-elute or show minimal retention on standard reverse-phase LC columns, leading to potential underestimation of total PFAS burden [23].

Emerging Solution: Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC)-MS/MS

- Principle: SFC uses supercritical carbon dioxide as the primary mobile phase, which behaves as a hybrid between a gas and a liquid. This provides different separation mechanics compared to LC.

- Advantages: Offers improved separation for short and ultrashort-chain PFAS that are missed by LC-MS. The technique is faster, uses less organic solvent, and is more environmentally friendly [23].

- Application: When used alongside LC-MS/MS, SFC-MS/MS provides a more comprehensive picture of the diverse PFAS present in environmental water samples, ensuring critical contaminants are not overlooked [23].

Aggregate Parameter Methods: Adsorbable Organic Fluorine (AOF)

For a broad screening of organofluorine pollution, EPA Method 1621 measures Adsorbable Organic Fluorine (AOF). This method does not identify specific PFAS but quantifies the total concentration of adsorbable organofluorines, providing an indicator of total PFAS contamination that can include thousands of known and unknown PFAS compounds [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PFAS Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., ¹³C-PFOA, ¹⁸O-PFOS) | Corrects for analyte loss during sample preparation and matrix effects during ionization in MS; essential for accurate quantification. | Required for isotope dilution techniques in Methods 533 and 1633A. |

| Weak-Anion Exchange (WAX) SPE Cartridges | Extracts and concentrates anionic PFAS from water samples; removes matrix interferences. | Standardized for EPA Methods 533, 537.1, and 1633A. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Methanol and Acetonitrile | Mobile phase and extraction solvents; high purity is critical to minimize background contamination. | Must be PFAS-free. Vendor certification is recommended. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide and Acetate Buffers | pH adjustment for sample preservation and SPE; used in elution solvents to efficiently recover PFAS from SPE cartridges. | Ensures optimal extraction efficiency and analyte stability. |

| PFAS-Free Water | Used for preparing blanks, standards, and mobile phases; essential for quality control. | Must be verified to be free of target PFAS analytes. |

| PFAS-Free Polypropylene Labware | Sample bottles, tubes, and vials to prevent leaching of PFAS from containers and introduction of background contamination. | HDPE and PP are preferred. Avoid Teflon or other fluoropolymers. |

The significant health and ecological risks posed by PFAS contamination in water resources have been the primary driver for advancing analytical science. This has resulted in a multi-tiered analytical strategy: highly sensitive and standardized methods like EPA 533, 537.1, and 1633A for targeted regulatory compliance; non-targeted HRMS methods for discovery and suspect screening; and innovative approaches like SFC-MS/MS and AOF analysis to close critical gaps for short-chain and unknown PFAS. As regulatory standards tighten and the understanding of PFAS toxicity evolves, the continued development and refinement of these analytical protocols remain paramount for protecting public health and the environment.

The Persistence of 'Forever Chemicals' in Water Systems

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a class of more than 15,000 synthetic chemicals characterized by their extreme persistence in the environment and exceptional resistance to degradation, earning them the colloquial name "forever chemicals" [24]. Their unique amphiphilic structure, featuring a hydrophobic fluorinated alkyl chain and a hydrophilic functional group, imparts the surface-tension lowering properties and chemical stability that make them valuable for industrial and consumer applications [25]. This same stability creates significant analytical challenges, as PFAS occur in environmental waters at trace concentrations (ng/L to μg/L) amid complex matrices that can interfere with detection and quantification [26] [25].

The analysis of PFAS in water systems requires sophisticated instrumentation and meticulous sampling protocols to achieve the low parts-per-trillion (ppt) detection levels necessary for meaningful environmental monitoring and risk assessment. A substantial complication arises from the fact that targeted analytical methods typically identify less than 1% of known PFAS, leaving a significant fraction of total PFAS burden uncharacterized in most studies [27]. This application note details standardized methodologies for the comprehensive analysis of PFAS in environmental waters, supporting robust environmental monitoring and defensible regulatory decision-making.

Analytical Frameworks for PFAS

Two complementary analytical philosophies govern PFAS assessment: targeted analysis for specific known compounds and total parameter analysis for comprehensive PFAS burden.

Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Analysis

Targeted Analysis methods are applicable to a specific defined set of known analytes. Using analytical standards for quantitation, these methods exclusively measure compounds on a predefined list; once analysis is complete, investigators cannot retrospectively look for other analytes [4]. Common targeted methods include EPA 533, 537.1, and 1633, which utilize liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [4].

Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) employs high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify known, unknown, and suspect PFAS in a sample. This approach enables retrospective data analysis as new PFAS are identified and can discover novel contaminants without predefined standards, though quantification may require structurally similar analytes for semi-quantitation [4].

Total PFAS and Fluorine Mass Balance

The fluorine mass balance approach is critical for understanding the comprehensive PFAS profile in a sample by reconciling measurements of total fluorine with identified individual PFAS [28]. This methodology reveals the substantial fraction of unknown organofluorine that often remains unaccounted for in targeted analyses alone [26].

Table 1: Total PFAS Analytical Parameters and Their Applications

| Parameter | Acronym | Analytical Method | Typical Reporting Units | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fluorine | TF | Combustion Ion Chromatography (CIC), Particle-Induced Gamma-Ray Emission (PIGE) | μg F/g, μg F/L, % | Comprehensive measurement of all fluorine in sample | Includes inorganic and organic fluorine |

| Total Organic Fluorine | TOF | CIC after removal of inorganic F | μg F/g, μg F/L | Estimates organofluorine content | May overestimate PFAS if other organofluorine present |

| Extractable Organic Fluorine | EOF | CIC of solvent extracts | μg F/g, μg F/L | Measures organofluorine extractable by specific solvents | Dependent on extraction efficiency |

| Absorbable Organic Fluorine | AOF | CIC after concentration on activated carbon | μg F/L | Designed for water samples | Potential for incomplete adsorption |

| Total Oxidizable Precursors | TOP | Oxidation followed by targeted analysis | μg/L, ng/L | Estimates precursor compounds that transform to perfluoroalkyl acids | May over/underestimate depending on precursors |

Fluorine Mass Balance Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated analytical approach for comprehensive PFAS characterization in water samples, highlighting the relationship between total fluorine measurements and specific compound identification.

Standardized Analytical Methods for Water

Regulatory agencies have established validated methods for PFAS analysis in various water matrices, with specific preservation, holding time, and quality control requirements.

Table 2: EPA Validated Methods for PFAS Analysis in Water Matrices

| Method | Target Matrices | Analytical Technique | Number of PFAS | Reporting Limits | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA Method 533 | Drinking Water | Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange SPE & LC-MS/MS | 25 | ng/L (ppt) | Includes short-chain PFAS and HFPO-DA (GenX) |

| EPA Method 537.1 | Drinking Water | SPE & LC-MS/MS | 18 | ng/L (ppt) | Includes HFPO-DA (GenX); Updated 2020 |

| EPA Method 1633 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, Tissue | LC-MS/MS | 40 | ng/L (ppt) | Multi-media method; DOD collaboration |

| EPA Method 8327 | Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater | External Standard Calibration & MRM LC-MS/MS | 24 | ng/L (ppt) | Non-potable water applications |

| OTM-45 | Air Emissions | LC-MS/MS | 50 | μg/m³ | Stationary source semivolatile and particulate-bound PFAS |

Protocol: Sampling PFAS in Environmental Waters

Scope: This protocol details the procedure for collecting water samples from groundwater, surface water, and wastewater for PFAS analysis using EPA Methods 1633, 533, or 537.1.

Materials and Equipment:

- PFAS-free water (supplied by analytical laboratory for blanks)

- High-density polyethylene (HDPE) or polypropylene sample containers (as specified by method)

- Nitrile or polyethylene gloves (powder-free)

- Polypropylene or stainless steel field gear

- Clean ice or refrigerated cooler

- Chain-of-custody forms

- Field notebook for documentation

Procedure:

Pre-Sampling Preparation:

- Obtain all sampling materials well in advance and screen Safety Data Sheets (SDSs) to exclude items containing fluoropolymers or "fluoro" compounds [5].

- Complete a pre-sampling equipment blank by filling a sample container with PFAS-free water at the office to verify decontamination procedures.

- Communicate with the laboratory regarding any known or suspected highly contaminated samples to prevent cross-contamination of laboratory equipment [5].

Sample Collection:

- Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (nitrile or polyethylene gloves, avoiding any products containing PFAS such as certain bug sprays or sunscreens) [5].

- Collect samples without headspace in the specified containers, using appropriate sampling apparatus (e.g., non-fluoropolymer tubing for groundwater).

- For running water, collect in the main flow; for still water, collect below surface avoiding surface microlayer where PFAS may concentrate.

- Preserve samples as required by the specific analytical method (typically refrigeration at 4°C).

Quality Control Samples:

- Collect field blanks (10% of samples or minimum of one per sampling event) using PFAS-free water exposed to sampling environment and equipment [5].

- Collect trip blanks that remain sealed until analysis to identify potential contamination during transport.

- For equipment decontamination, use PFAS-free water and avoid fluorinated surfactants or solvents.

Sample Handling and Shipment:

- Place samples immediately on ice or refrigerate at 4°C.

- Complete chain-of-custody documentation, noting any potentially high-concentration samples.

- Ship samples to laboratory within the method-specified holding time (typically 14 days for PFAS analysis).

Technical Notes:

- The potential for cross-contamination from commonly used sampling materials is extremely low but difficult to document; a conservative approach excluding known PFAS-containing materials is recommended [5].

- Documentation should include details of sampling equipment, preservation methods, and any deviations from the protocol.

Protocol: Targeted Analysis by LC-MS/MS

Scope: This protocol describes the procedure for targeted analysis of specific PFAS compounds in water samples using LC-MS/MS, consistent with EPA Methods 533, 537.1, and 1633.

Principles: Targeted LC-MS/MS analysis utilizes isotope-dilution or internal standard calibration for precise quantification of specific PFAS compounds. The method relies on solid-phase extraction (SPE) for concentration and matrix cleanup, followed by reversed-phase liquid chromatography separation and detection with tandem mass spectrometry using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with binary or quaternary pump and autosampler

- Tandem mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ESI) source

- C18 or equivalent reversed-phase analytical column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm)

- Solid-phase extraction apparatus and cartridges (specified by method)

- Certified PFAS analytical standards and corresponding isotopically labeled internal standards

- HPLC-grade solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, ammonium acetate/acetate buffer)

- PFAS-free vials and consumables

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Thaw samples if frozen and allow to reach room temperature.

- Precisely add isotopically labeled internal standards to each sample and quality control materials.

- For EPA Method 533, condition weak anion-exchange (WAX) SPE cartridges with sequential methanol, pH 4 buffer, and reagent water.

- Load samples at 5-10 mL/min flow rate.

- Dry cartridges under vacuum for 10-15 minutes.

- Elute with sequential basic methanol (0.1% NH4OH) and methanol into polypropylene tubes.

- Concentrate extracts under gentle nitrogen stream to near dryness.

- Reconstitute in initial mobile phase for LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Mobile Phase A: 2mM ammonium acetate in water

- Mobile Phase B: Methanol or 95% methanol/5% water with 2mM ammonium acetate

- Column Temperature: 30-40°C

- Flow Rate: 0.3-0.6 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 1-10 μL

- Gradient Program: Begin at 10-20% B, increase to 98-100% B over 10-20 minutes

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Negative

- Source Temperature: 300-500°C

- Ion Spray Voltage: -2500 to -4500 V

- MRM Transitions: Monitor at least two transitions per analyte (quantifier and qualifier)

- Dwell Time: 10-100 msec per transition

- Chromatographic Separation:

Quantification:

- Prepare 5-8 point calibration curve using authentic standards (e.g., 0.5-500 ng/L)

- Include continuing calibration verification standards every 10-20 samples

- Calculate concentrations using internal standard method with isotopically labeled analogs

Technical Notes:

- Maintain strict contamination control: dedicate glassware, use PFAS-free solvents, and avoid Teflon-containing materials throughout the procedure.

- Monitor for instrumental carryover by injecting solvent blanks between samples.

- Confirm compound identities using retention time matching (±0.1 min) and qualifier/quantifier ion ratio criteria (±20-30% of standard).

Advanced Methods for Total PFAS Assessment

While targeted methods are essential for regulatory compliance, comprehensive PFAS assessment requires complementary techniques to capture the extensive fraction of unidentified PFAS.

Protocol: Combustion Ion Chromatography for Total Fluorine

Scope: This protocol describes the determination of total fluorine (TF) and extractable organic fluorine (EOF) in water samples using combustion ion chromatography (CIC), the most utilized method (>50% of studies) for total PFAS analysis [26].

Principles: Sample combustion at 900-1100°C converts organofluorine to hydrogen fluoride, which is absorbed in solution and quantified by ion chromatography. For EOF analysis, samples undergo solvent extraction prior to combustion to isolate organic fluorine.

Materials and Equipment:

- Combustion ion chromatograph system (combustion module + ion chromatograph)

- Quartz combustion boat or sample cups

- Oxygen purification system

- Absorbing solution (typically deionized water or alkaline solution)

- Ion chromatography system with conductivity detector

- AS14, AS15, or equivalent anion-exchange column

- Sodium carbonate/bicarbonate eluent

- Methanol (HPLC grade) for EOF extraction

Procedure:

Total Fluorine Analysis:

- Piper 1-100 μL of water sample (volume depends on expected F concentration) into pre-combusted quartz sample boat.

- For solid samples, accurately weigh 2-10 mg into sample boat.

- Introduce sample into combustion tube maintained at 1000-1100°C under oxygen flow (150-200 mL/min).

- Combust for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete decomposition.

- Transport combustion gases through absorption solution (deionized water).

- Analyze absorbed solution by ion chromatography with conductivity detection.

- Quantify fluoride concentration against external calibration standards (typically 0.01-10 mg F/L).

Extractable Organic Fluorine Analysis:

- Extract 100-500 mL water sample with equal volume of methanol or specified solvent.

- For solid samples, perform accelerated solvent extraction or sonication with methanol/water.

- Evaporate extract to near dryness under gentle nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitute in small volume of methanol for CIC analysis.

- Analyze via CIC as described above.

- Calculate EOF by subtracting inorganic fluoride (determined by direct IC analysis of uncombusted extract) from total fluorine in extract.

Technical Notes:

- Method detection limits for TF in water are typically 1-10 μg F/L, requiring preconcentration for low-level environmental samples.

- Include certified reference materials where available (e.g., NIST SRM 1957, 1958) for quality control.

- Potential interferences include aluminum and other cations that can complex fluoride; these are typically minimized by the combustion process.

- Between analyses, run blank samples to monitor for memory effects and carryover.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Total PFAS Analytical Methods

| Method | Detection Principle | Approximate MDL | Sample Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion Ion Chromatography (CIC) | Sample combustion + IC detection | 1-10 μg F/L (water), 1-10 μg F/g (solid) | 10-20 samples/day | Comprehensive TF measurement; No compound-specific standards needed | Does not differentiate PFAS from other organofluorine |

| Particle-Induced Gamma-Ray Emission (PIGE) | Nuclear reaction analysis | 100 μg F/g (solid) | Minutes per sample | Non-destructive; Direct analysis of solids | Higher detection limits; Limited to solid samples |

| High-Resolution-Continuum Source GF-MAS | Molecular absorption spectrometry | 0.1-1 μg F/L | 15-30 minutes/sample | High sensitivity for liquids; Minimal sample prep | Limited to liquid samples; Matrix interferences possible |

| Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis (INAA) | Neutron activation + gamma spectroscopy | 10-100 μg F/g | Requires neutron source | Non-destructive; Multi-element capability | Limited accessibility; Requires nuclear reactor |

| 19F Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Nuclear magnetic resonance | 10-100 μg F/g | Hours per sample | Structural information; Non-destructive | Low sensitivity; Requires high concentrations |

PFAS Analytical Decision Framework: This diagram outlines the strategic selection of complementary analytical techniques based on research objectives, emphasizing how targeted and total parameter methods converge in a comprehensive fluorine mass balance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PFAS Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified PFAS Analytical Standards | Quantification and identification of target analytes | Purity >95%, concentration-certified solutions in methanol | Verify purity and concentration; monitor for degradation |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards (13C, 18O) | Correction for extraction efficiency and matrix effects | Isotopic purity >98%, representative of target analytes | Use at beginning of extraction; monitor for cross-talk |

| PFAS-Free Water | Blanks, dilution, mobile phase preparation | Documented <1 ng/L total PFAS, resistivity >18 MΩ·cm | Analyze certificate of analysis; run method blanks regularly |

| SPE Cartridges (WAX, C18, GCB) | Sample extraction and cleanup | 60-150 mg sorbent mass, polypropylene housings | Pre-lot test recovery; avoid fluoropolymer components |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Extraction, mobile phases | LC-MS grade, low PFAS background, in glass containers | Lot-test for PFAS contamination; monitor system blanks |

| Nitrogen Gas (High Purity) | Solvent evaporation, instrument operation | >99.995% purity, PFAS-free, with proper filtration | Verify purity certification; monitor for contamination |

| Sample Vials and Containers | Sample storage, analysis | HDPE or polypropylene, certified PFAS-free, pre-cleaned | Conduct pre-use testing; avoid fluoropolymer caps/septa |

| Quality Control Materials | Method validation, ongoing QC | Certified reference materials, laboratory control samples | Include with each batch; verify within acceptance criteria |

Data Interpretation and Reporting

Effective PFAS data interpretation requires understanding the complementary nature of different analytical approaches and their respective limitations. The fluorine mass balance concept is fundamental, wherein the measured total fluorine (TF) is reconciled with the sum of identified individual PFAS and other fluorine sources [28]. Recent studies demonstrate that targeted PFAS typically account for only a minute fraction (0.01-1.0%) of extractable organic fluorine (EOF), which itself may represent just 3-8.8% of total fluorine in commercial products [28]. This substantial gap highlights the vast unknown fraction of organofluorine in environmental samples and the critical need for complementary analytical approaches.

Reported PFAS concentrations in global surface waters range from 0.01 ng/L to 311.25 ng/L, with perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) being the most commonly occurring class [25]. Meta-analysis reveals that perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) has the highest meta-synthesized median concentration of 3.6 ng/L in surface waters [25]. Environmental risk assessment using hazard quotient values indicates high risk for certain pharmaceuticals and moderate risk for longer-chain PFAS like perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoA) [25].

Inter-laboratory comparisons face challenges due to inconsistent reporting units (e.g., mg/L, μg/m3, %) across studies [26]. Standardization of reporting in consistent units (preferably μg F/L or ng F/L for total parameters) would significantly improve data comparability and meta-analysis capabilities. Furthermore, substantial geographic biases exist in the current literature, with 69% of studies originating from just four countries: United States (33%), Sweden (12%), China (12%), and Germany (11%) [26] [29], highlighting significant data gaps for South America, Africa, and atmospheric PFAS.

Standardized PFAS Analytical Methods: From Sampling to Quantification

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) represent a large class of synthetic chemicals that present significant analytical challenges due to their widespread presence in environmental samples and their persistence in the environment [4]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed and validated several analytical methods to support the accurate measurement of PFAS in different water matrices. Among these, EPA Methods 533, 537.1, and 8327 have emerged as critical tools for researchers and environmental scientists conducting targeted analysis of specific PFAS compounds [6] [4]. These methods were developed with particular attention to accuracy, precision, and robustness through multi-lab validation and peer review processes [6].

The evolution of PFAS analytical methods reflects the growing understanding of these complex compounds and the need for reliable data to support regulatory decisions and environmental monitoring. While Method 537 was the first EPA method for PFAS in drinking water (measuring 14 compounds), it has been superseded by Methods 537.1 and 533, which together can measure 29 PFAS in drinking water [6]. Method 8327, meanwhile, addresses the need for PFAS analysis in non-potable water matrices, filling a critical gap in environmental monitoring capabilities [4].

Scope and Application

The three EPA methods discussed herein are designed for specific applications and water matrices, making proper method selection crucial for research quality and data defensibility.

EPA Method 533: Determination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Drinking Water by Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange Solid Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry is a solid phase extraction (SPE) liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for determining select PFAS in drinking water [30]. Published in 2019, it measures 25 PFAS compounds and incorporates isotope dilution standards to minimize matrix effects and improve data quality [31] [32].

EPA Method 537.1: Determination of Selected PFAS in Drinking Water by Solid Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry is the updated version of the original Method 537. This method can quantitate 18 PFAS in drinking water, including HFPO-DA (a component of GenX processing aid technology) and three additional PFAS not included in the original Method 537 [32]. The 2020 update to Version 2.0 contained only editorial revisions without technical changes [4].

EPA Method 8327: PFAS Using External Standard Calibration and MRM LC/MS/MS is designed for analyzing 24 PFAS in non-potable water matrices, including groundwater, surface water, and wastewater [4]. Unlike Methods 533 and 537.1, it is not approved for drinking water compliance monitoring but serves important roles in environmental characterization and remediation studies.

Comparative Method Specifications

Table 1: Comparative Specifications of EPA PFAS Analytical Methods

| Parameter | EPA Method 533 | EPA Method 537.1 | EPA Method 8327 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Matrix | Drinking Water | Drinking Water | Non-Potable Water (Groundwater, Surface Water, Wastewater) |

| Total Analytes | 25 PFAS | 18 PFAS | 24 PFAS |

| Key Analytical Approach | Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange SPE and LC/MS/MS | Solid Phase Extraction and LC/MS/MS | External Standard Calibration and MRM LC/MS/MS |

| Chain Length Coverage | Includes shorter-chain PFAS | Broader range of long-chain PFAS | Varied chain lengths |

| Regulatory Status | Approved for UCMR 5 and NPDWR compliance [6] | Approved for UCMR 5 and NPDWR compliance [6] | Not approved for drinking water compliance |

| Unique Capabilities | Can detect some shorter-chain PFAS not covered by 537.1; Uses stable isotope dilution standards [33] [31] | Includes HFPO-DA (GenX) and other replacement PFAS [32] | Applicable to challenging water matrices; Faster turnaround possible [34] |

Analyte Coverage Comparison

Table 2: Select PFAS Analytes Detected by Each Method

| PFAS Analyte | Abbreviation | Method 533 | Method 537.1 | Method 8327 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluorobutanoic acid | PFBA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluoropentanoic acid | PFPeA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorohexanoic acid | PFHxA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluoroheptanoic acid | PFHpA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorooctanoic acid | PFOA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorononanoic acid | PFNA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorodecanoic acid | PFDA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluoroundecanoic acid | PFUnA | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Perfluorododecanoic acid | PFDoA | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Perfluorotetradecanoic acid | PFTeDA | ✓ | ||

| Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | PFBS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid | PFHxS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid | PFHpS | ✓ | ||

| Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | PFOS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid | PFDS | ✓ | ||

| HFPO-DA (GenX) | HFPO-DA | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9Cl-PF3ONS | 9Cl-PF3ONS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 11Cl-PF3OUdS | 11Cl-PF3OUdS | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ADONA | ADONA | ✓ |

Detailed Methodologies

EPA Method 533: Experimental Protocol

3.1.1 Principle and Scope EPA Method 533 employs isotope dilution anion exchange solid phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [30]. The method builds upon previous EPA Methods 537 and 537.1 but with several notable differences, including the addition of several odd-chain perfluorinated sulfonic acids (PFSAs), short-chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs), fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS compounds), and novel perfluoroether carboxylates and sulfonates [31].

3.1.2 Sample Preparation Workflow

- Preservation and Fortification: Add ammonium chloride buffer to drinking water samples immediately upon collection or within 48 hours of collection. Spike with isotope dilution standards (EPA-533ES) to correct for matrix effects and extraction efficiency [31].

- Solid Phase Extraction: Pass 100-250 mL of sample through 500 mg Phenomenex Strata-X-AW or equivalent SPE cartridges. The method provides flexibility in cartridge selection compared to previous methods [31].

- Elution and Concentration: Elute analytes with methanol followed by a mixture of ammonium hydroxide in methanol. Evaporate the eluent to near dryness using a gentle nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the extract in 1 mL of 80:20 methanol:water and spike with instrument performance standard (EPA-533IS) [31].

3.1.3 Instrumental Analysis

- Chromatography: Utilize a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (50 × 2 mm, 3 μm particle size) or equivalent with gradient separation using water (with 20 mM ammonium acetate) and methanol as mobile phases at 0.6 mL/min flow rate [31].

- Mass Spectrometry: Employ LC-MS/MS with electrospray ionization in negative ion mode using scheduled MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) for optimal sensitivity and specificity [31].

- Quality Control: Include calibration standards, laboratory control samples, method blanks, and quality control checks to ensure isotope dilution standard recovery between 50-200% and instrument performance standard recovery between 50-150% of the average area measured during initial calibration [31].

EPA Method 537.1: Experimental Protocol

3.2.1 Principle and Scope Method 537.1 employs solid phase extraction followed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for the determination of 18 selected PFAS compounds in drinking water [32]. This method was developed as an update to the original Method 537 to address additional PFAS that have the potential to contaminate drinking water, particularly PFOA/PFOS alternatives used in manufacturing [32].

3.2.2 Sample Collection and Preservation

- Collect samples in high-density polyethylene or polypropylene containers.