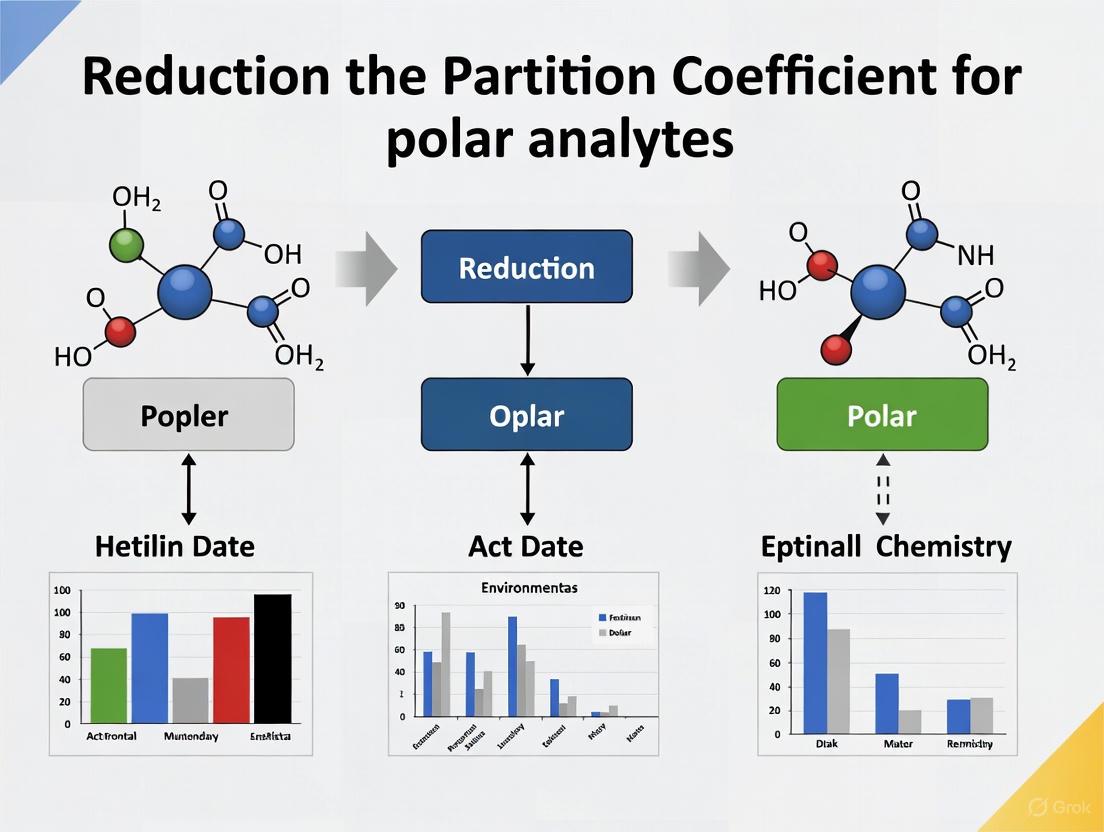

Strategic Approaches to Reduce Partition Coefficients for Enhanced Polar Analyte Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on strategically reducing partition coefficients (LogP/LogD) to improve the analysis and pharmacokinetic properties of polar analytes.

Strategic Approaches to Reduce Partition Coefficients for Enhanced Polar Analyte Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on strategically reducing partition coefficients (LogP/LogD) to improve the analysis and pharmacokinetic properties of polar analytes. It covers foundational principles exploring the critical role of lipophilicity in drug absorption, distribution, and analytical interference. The content details practical methodological approaches including pH manipulation, surfactant use, and chromatographic strategies, supported by recent case studies and computational prediction tools. The article further addresses troubleshooting common challenges in polar compound separation and validates various prediction methods, offering a synthesized framework for optimizing polar analyte behavior in both analytical and biological contexts.

Understanding Partition Coefficients: Why Lipophilicity Matters for Polar Analytes

Core Definitions and FAQs

What are LogP and LogD?

LogP, or the partition coefficient, is a measure of a compound's lipophilicity, quantifying how it distributes itself between two immiscible solvents—typically 1-octanol (representing lipid membranes) and water (representing aqueous bodily fluids like blood) [1] [2]. It is defined as the logarithm (base 10) of the ratio of the concentration of the unionized solute in the organic phase to its concentration in the aqueous phase at equilibrium [2].

LogD, or the distribution coefficient, is an extension of this concept that accounts for the ionization state of a compound at a specific pH [1] [3]. It represents the logarithm of the ratio of the sum of the concentrations of all forms of the compound (ionized plus unionized) in the organic phase to the sum of the concentrations of all forms in the aqueous phase [2].

Key Differences at a Glance

Table 1: Fundamental differences between LogP and LogD

| Feature | LogP (Partition Coefficient) | LogD (Distribution Coefficient) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Species Measured | Only the unionized, neutral form of the compound [1] [2] | All species present—both ionized and unionized [1] [2] |

| pH Dependence | pH-independent; assumes a non-ionizable compound [1] [3] | pH-dependent; value changes with the pH of the aqueous environment [1] [3] |

| Application Scope | Best suited for non-ionizable compounds [1] | Essential for ionizable compounds (e.g., acids, bases) [1] [4] |

| Reported Value | A single number for a given compound [2] | Always reported with a specified pH (e.g., LogD at pH 7.4) [2] |

Why are LogP and LogD Critical in Drug Discovery?

Lipophilicity, as measured by LogP and LogD, is a fundamental property that profoundly influences a drug candidate's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) [1] [4]. A compound must possess a balance of hydrophilicity and lipophilicity: it needs sufficient water solubility to be dissolved in blood and other aqueous fluids, yet enough lipophilicity to penetrate lipid-rich cell membranes [3]. This is why the ideal LogP for an orally available drug is typically between 1 and 5, as per Lipinski's Rule of Five [1] [3]. Over-reliance on LogP for ionizable compounds can be misleading, as it does not reflect the compound's true behavior under physiological pH conditions, making LogD a more accurate and valuable descriptor [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for partition and distribution coefficient studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| 1-Octanol | Standard non-polar solvent used to simulate lipid bilayers in the octanol-water partition system [5] [2]. |

| Aqueous pH Buffers | Used to control the ionization state of the analyte in LogD measurements. Common buffers include phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [3]. |

| Volatile Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Formate/Acetate) | Essential for HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography) methods coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) detection, as they do not clog the MS source [6]. |

| HILIC Columns | Chromatographic columns with polar stationary phases (e.g., bare silica, amide, cyano) used to separate and analyze highly polar compounds that are not retained in reversed-phase (C18) chromatography [7] [6]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used for sample clean-up and concentration. Elution in a high-organic solvent provides an ideal injection solvent for HILIC analysis [6]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Standard Workflow for Determining Lipophilicity

The following diagram outlines a general decision-making workflow for determining and applying lipophilicity metrics.

Quantitative Data and Interpretation

Table 3: Example LogP values for common chemicals, illustrating the range from hydrophilic to lipophilic [2]

| Compound | LogP Value | Temperature (°C) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetamide | -1.16 | 25 | Highly hydrophilic (water-loving) |

| Methanol | -0.81 | 19 | Hydrophilic |

| Formic Acid | -0.41 | 25 | Hydrophilic |

| Diethyl Ether | 0.83 | 20 | Moderately lipophilic |

| p-Dichlorobenzene | 3.37 | 25 | Lipophilic |

| Hexamethylbenzene | 4.61 | 25 | Highly lipophilic |

| 2,2',4,4',5-Pentachlorobiphenyl | 6.41 | Ambient | Extremely lipophilic (hydrophobic) |

The Mathematical Relationship Between LogP, LogD, and pH

For a monoprotic acid, the distribution coefficient (D) can be calculated from the partition coefficient (P) and the acid dissociation constant (Ka) using the following equation, which highlights the pH dependence of LogD [5]:

D = P / (1 + 10^(pH - pKa))

This relationship shows that for an acidic compound, as the pH increases above its pKa, the concentration of the ionized form in water rises, leading to a lower distribution coefficient (D) and a more negative LogD value [4]. A similar relationship exists for basic compounds.

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios in Polar Analyte Research

FAQ: How can I use LogD to reduce matrix interference for a non-polar compound?

Scenario: You are developing an immunochromatographic assay for ethoxyquin (EQ), a highly non-polar compound, in complex aquatic product matrices, and you are facing interference from co-extracted lipids [8].

Solution: A pH-dependent extraction strategy leveraging the compound's LogD range can effectively eliminate this interference.

- Action: Systematically adjust the pH of the extraction solvent. The LogD of an ionizable compound changes with pH. By extracting at a pH where the target analyte is in its ionized form (and thus has low LogD and high water solubility), while the interfering lipids remain non-polar, you can selectively leave the analyte in the aqueous phase or partition it away from the lipids [8].

- Outcome: This method was successfully used to isolate EQ from lipid co-extracts, achieving a detection limit of 10 μg/kg, well below international thresholds, without complex cleanup procedures [8].

FAQ: Why do my polar analytes have poor retention on my C18 column?

Scenario: Your polar basic analytes show little to no retention under standard reversed-phase (C18) liquid chromatography conditions, leading to poor separation [7].

Solution: This occurs because C18 stationary phases are hydrophobic, while polar analytes are hydrophilic. They have no affinity for the column and elute with the solvent front.

- Action: Switch to a HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography) column [7] [6]. HILIC uses a polar stationary phase (e.g., bare silica, amide) and a mobile phase that is high in organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile). In HILIC, water is the strong eluting solvent, making it ideal for retaining polar compounds.

- Additional Tip: Ensure the injection solvent has a high organic content to match the initial mobile phase conditions. Injecting a sample in a high-aqueous solvent onto a HILIC column can cause severe peak broadening and loss of retention [6].

FAQ: How does pH affect my chromatographic method development?

Scenario: You notice inconsistent retention times and peak shapes for an ionizable analyte when developing a HILIC method.

Solution: The pH of the mobile phase significantly affects the charge state of both the analyte and the stationary phase.

- Action: For ionizable compounds, the mobile phase pH is a critical parameter to optimize during method development. The effective pH of the mobile phase in HILIC can be 1-1.5 units higher than the aqueous buffer alone due to the high organic solvent content [6].

- Example: A bare silica HILIC column has a pKa of ~3.8-4.5. At a pH below this, the silica is neutral; above it, the silica is negatively charged. An analyte with protonated amine groups will interact strongly with the charged silica, increasing retention. Use volatile buffers like 10-50 mM ammonium formate or acetate to control pH effectively, especially for LC-MS applications [6].

The Direct Impact of Lipophilicity on Absorption, Permeability, and Solubility

Core Concepts: Lipophilicity in Drug Development

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between lipophilicity and key biopharmaceutical properties? Lipophilicity, primarily measured as LogP (partition coefficient) and LogD (distribution coefficient at a specific pH), directly governs a drug candidate's solubility, permeability, and ultimate absorption. These properties exist in a delicate balance: increasing lipophilicity typically enhances membrane permeability but reduces aqueous solubility, creating an optimization challenge for researchers [9] [10].

Q2: What is the optimal lipophilicity range for oral bioavailability? For conventional oral drugs, a LogP between 1 and 3 is generally considered optimal [9]. This range balances sufficient membrane permeability with adequate aqueous solubility. For Central Nervous System (CNS) targets, a slightly higher LogP range of 2 to 4 may be necessary to cross the blood-brain barrier [9].

Q3: How does lipophilicity relate to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS)? The BCS categorizes drugs based on solubility and permeability, both heavily influenced by lipophilicity [9] [11]. LogP/LogD are key parameters for predicting BCS class:

- BCS Class I (High Solubility, High Permeability): Often associated with optimal LogP.

- BCS Class II (Low Solubility, High Permeability): Typically includes compounds with higher LogP.

- BCS Class III (High Solubility, Low Permeability) and BCS Class IV (Low Solubility, Low Permeability): Often feature lower or suboptimal LogP values [11].

Q4: Why is LogD sometimes more relevant than LogP for polar analytes? LogD accounts for the ionization state of a molecule at a specific physiological pH (e.g., pH 1.2 in the stomach, pH 6.5 in the intestine). For ionizable polar compounds, LogD provides a more accurate picture of the true lipophilicity under relevant biological conditions, guiding strategies for partition coefficient reduction [8].

Table 1: Impact of Lipophilicity on Key Drug Properties and Development Outcomes

| Lipophilicity (LogP) Range | Impact on Solubility | Impact on Permeability | Associated Risk in Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 0 | High | Very Low | Poor absorption, limited target access |

| 1 – 3 (Optimal) | Moderate | High | Favorable bioavailability, lower risk |

| 4 – 5 | Low | High | Potential solubility-limited absorption |

| > 5 | Very Low | Very High | High risk of failure, poor solubility, metabolic issues |

Troubleshooting Guide: Lipophilicity-Related Issues

Problem: Poor Aqueous Solubility Despite Good Permeability (BCS Class II profile)

- Potential Cause: Excessive lipophilicity (LogP > 4).

- Solutions:

- Structural Modification: Introduce ionizable groups or polar fragments to reduce LogP.

- Formulation Approach: Utilize amorphous solid dispersions, lipid-based formulations, or nanonization to enhance apparent solubility [9].

- Salt Formation: For ionizable compounds, form salts to significantly improve aqueous solubility [9].

Problem: Inadequate Membrane Permeability

- Potential Cause: Insufficient lipophilicity (LogP < 1), or high polarity limiting passive diffusion.

- Solutions:

- Structural Modification: Strategically incorporate lipophilic fragments or reduce hydrogen-bonding capacity to increase LogP within the optimal range.

- Prodrug Approach: Design prodrugs with higher lipophilicity to enhance permeability, which then convert to the active parent drug in vivo.

Problem: Inconsistent In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation (IVIVC) for Absorption

- Potential Cause: Over-reliance on LogP without considering pH-dependent ionization (LogD).

- Solutions:

- Measure LogD: Characterize LogD across the physiological pH range (1.2–7.4) to better predict absorption in different GI regions [8].

- Use Biorelevant Media: Perform solubility and permeability assays in media that mimic intestinal fluids.

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Standardized Experimental Methodologies

Protocol 1: Determining LogP/LogD Using the Shake-Flask Method

- Principle: The compound is partitioned between n-octanol (lipophilic phase) and aqueous buffer (hydrophilic phase). The concentration in each phase is measured at equilibrium [12].

- Procedure:

- Phase Saturation: Pre-saturate n-octanol and aqueous buffer (at desired pH for LogD) with each other.

- Partitioning: Add a small quantity of the drug compound to the system and mix vigorously (shaking) for a set period (e.g., 24 hours) at constant temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Separation & Analysis: Allow phases to separate completely. Withdraw samples from each phase and analyze drug concentration using a validated method (e.g., HPLC-UV).

- Calculation: LogP or LogD = Log10 (Concentration in octanol / Concentration in aqueous buffer).

- Key Considerations:

- Ensure the system reaches equilibrium.

- Verify compound stability under experimental conditions.

- Use a low compound concentration to avoid saturation [12].

Protocol 2: Assessing Permeability Using Caco-2 Cell Monolayers

- Principle: This in vitro model uses human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells that differentiate into enterocyte-like monolayers, mimicking the intestinal barrier [13].

- Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Grow Caco-2 cells on permeable filters until they form confluent, differentiated monolayers (typically 21 days). Verify monolayer integrity by measuring Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER).

- Dosing: Add the drug compound in buffer (donor compartment, e.g., apical side for absorption studies).

- Incubation & Sampling: Incubate at 37°C. Sample from the receiver compartment (e.g., basolateral side) at predetermined time points.

- Analysis & Calculation: Quantify drug appearance in the receiver compartment. Calculate the apparent permeability coefficient, Papp [13].

- Method Suitability: Include internal standards (e.g., high-permeability metoprolol, low-permeability atenolol) to validate assay performance and classify test compounds [13].

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Turbidimetric Solubility Measurement

- Principle: A rapid method for estimating solubility in discovery settings by detecting the onset of precipitation upon aqueous dilution of a DMSO stock solution [14].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the compound in DMSO.

- Dilution: Dilute the stock solution into aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4) in a microtiter plate.

- Measurement: Monitor the solution turbidity (light scattering) using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Identify the concentration at which turbidity increases significantly, indicating precipitation. This provides an estimate of the compound's solubility [14].

Data Interpretation and Decision-Making

Table 2: Benchmark Values for Key Experimental Assays in Drug Discovery

| Assay | Parameter | Low / Unfavorable | Moderate / Acceptable | High / Favorable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake-Flask | LogP (for oral drugs) | < 0 or > 5 | 0 - 3 | 1 - 3 (Optimal) |

| Caco-2 | Papp (10⁻⁶ cm/s) | < 0.5 | 0.5 - 5 | > 5 |

| PAMPA | Papp (10⁻⁶ cm/s) | < 0.5 | 0.5 - 5 | > 5 |

| Turbidimetric | Solubility (μM) | < 10 | 10 - 200 | > 200 |

Workflow for Addressing Lipophilicity in Polar Analytes

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving issues related to the absorption of polar analytes, focusing on lipophilicity.

Computational & Advanced Tools

Computational Prediction of Lipophilicity and Permeability

AI and Machine Learning Models

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs): Used for predicting drug solubility in complex solvent systems with high accuracy, leveraging molecular structure graphs [15].

- Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR): AI-based systems can predict Human Intestinal Absorption (HIA) by combining classification and regression models, showing high accuracy for specific drug classes like serotonergic compounds [11].

- MF-LOGP: A random forest model requiring only molecular formula (no structural information) to predict LogP, useful for high-throughput screening or when structure is unknown [12].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

- Application: MD provides atomistic detail on drug permeation through lipid bilayers. Advanced techniques can model the influence of membrane environment on a drug's protonation state and the associated entropy-polarity balance, which is critical for accurate permeability prediction [16] [10].

Decision Trees for Absorption Prediction

Modern approaches go beyond simple rules. A decision tree model using the CART algorithm has incorporated in vitro precipitation and permeability data, excluding solubility, to create a robust tool for ranking oral absorption potential [17].

Computational Workflow for Property Prediction

The following diagram illustrates a modern, computational approach to predicting key properties early in the drug discovery process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipophilicity and Absorption Studies

| Category | Reagent/Material | Typical Application | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partitioning Systems | n-Octanol | LogP/LogD (Shake-Flask) | Standard lipid phase surrogate for biomembranes [12]. |

| Biorelevant Buffers (pH 1.2 - 7.4) | LogD, Solubility | Simulates gastrointestinal pH conditions for relevant data [8]. | |

| Permeability Models | Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro Permeability | Gold-standard cell model for predicting human intestinal absorption [13]. |

| PAMPA Plates | High-throughput Permeability | Artificial membrane assay for rapid passive diffusion screening [13]. | |

| Transwell Plates | Cell-based Permeability | Permeable supports for growing cell monolayers for transport studies. | |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC-UV/MS | Concentration Analysis | Quantifies drug concentrations in partitioning/permeability samples. |

| 96/384-well Microplates | High-throughput Assays | Enables automation and miniaturization of solubility/permeability screens. | |

| Computational Software | Mordred/PaDEL Descriptors | QSPR Modeling | Calculates molecular descriptors from structure for AI/ML models [11]. |

| Graph Convolutional Network Tools | Solubility Prediction | Predicts solubility in binary solvent mixtures with high accuracy [15]. | |

| Reference Standards | High/Low Permeability Markers (e.g., Metoprolol, Atenolol) | Assay Suitability | Validates permeability model performance and classifies test compounds [13]. |

| Paracellular Markers (e.g., Lucifer Yellow) | Integrity Monitoring | Verifies monolayer integrity in cell-based permeability assays [13]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

What is a matrix effect and how does it impact my GICA results?

The sample "matrix" is everything in your sample except your target analyte (e.g., proteins, salts, metabolites). A matrix effect occurs when these components interfere with the assay, altering the signal from your analyte and leading to inaccurate quantitation. In the context of reducing partition coefficients for polar analytes, a high partition coefficient in an aqueous organic system can sometimes preconcentrate interferents alongside your analyte, exacerbating these effects [18].

How can I quickly check if my GICA experiment has matrix interference?

A common and effective strategy is to perform a spike-and-recovery experiment [19].

- Prepare a Calibrator: Spike a known concentration of your pure analyte into a simple, clean buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) and run it on your GICA strip.

- Prepare a Matrix Sample: Spike the same known concentration of analyte into your complex sample matrix (e.g., blood, urine, or soil extract) and run it.

- Compare Signals: Calculate the percentage recovery of the analyte in the matrix sample compared to the calibrator. A recovery significantly different from 100% (e.g., <80% or >120%) indicates a clear matrix effect is present.

The table below summarizes frequent culprits.

| Source of Interference | Description | Impact on GICA |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins) | Can bind non-specifically to antibodies or gold nanoparticles, causing false positives or negatives. | High |

| Sample pH & Ionic Strength | Affects the binding kinetics between the antibody and analyte, potentially weakening the test line signal. | High |

| Lipids & Hemoglobin | In blood-based samples, these can quench signals or physically block the flow on the nitrocellulose membrane. | Medium-High |

| Cross-reacting Analytes | Structurally similar molecules that are recognized by the capture antibody, leading to false positives. | High |

What solutions can I use to mitigate matrix interference?

Several methodologies are available, depending on your specific interference.

- Sample Dilution: A simple and effective first step. Diluting the sample with a suitable buffer can reduce the concentration of interferents below a problematic level. However, this also dilutes your analyte, which can be a problem for low-concentration targets.

- Sample Pre-treatment: Using techniques like filtration, solid-phase extraction (SPE), or protein precipitation to remove interferents from the sample before applying it to the GICA strip.

- The Internal Standard Method: A powerful approach where a known amount of a non-interfering standard is added to every sample. The signal from your analyte is then reported as a ratio to the internal standard's signal, correcting for variable matrix effects [19]. This is a gold standard in quantitative LC-MS for mitigating ionization suppression/enhancement [19].

- Antibody Selection: Using high-affinity, highly specific monoclonal antibodies can minimize cross-reactivity with non-target matrix components.

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Matrix Effects via Spike-and-Recovery

This protocol provides a detailed methodology to confirm and quantify matrix interference.

Objective: To determine the extent of matrix-induced signal suppression or enhancement in a GICA for a specific polar analyte.

Materials:

- GICA test strips

- Purified target analyte (standard)

- Negative matrix sample (e.g., analyte-free serum)

- Positive control sample

- Pipettes and appropriate buffers

Procedure:

- Prepare a stock solution of your analyte at a known concentration within the dynamic range of your GICA.

- Create two sets of samples in triplicate:

- Set A (Buffer Spike): Spike a known volume of the stock solution into a clean, compatible buffer.

- Set B (Matrix Spike): Spike the same volume of stock solution into the negative matrix sample.

- Run all samples (Set A and Set B) on the GICA strips according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Use a strip reader to quantitatively measure the intensity of the test line for each strip.

- Calculation:

- Calculate the average signal intensity for Set A (Buffer) and Set B (Matrix).

- % Recovery = (Average Signal of Matrix Spike / Average Signal of Buffer Spike) × 100

Interpretation: A recovery of 85-115% is typically acceptable. Recovery outside this range confirms a significant matrix effect that requires mitigation strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for developing and troubleshooting GICA assays focused on polar analytes.

| Item | Function in GICA / Polar Analyte Research |

|---|---|

| High-Affinity Monoclonal Antibodies | The core recognition element; crucial for minimizing cross-reactivity with matrix components. |

| Gold Nanoparticle Conjugates | Commonly used as the visual or optical label in the immunoassay. |

| Nitrocellulose Membrane | The platform for capillary flow and the site of antibody-antigen binding at test and control lines. |

| Blocking Buffers (e.g., with BSA, sucrose, trehalose) | Used to passivate the membrane and nanoparticle surfaces, reducing non-specific binding of matrix proteins. |

| Aqueous Organic Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Used in sample pre-treatment to precipitate proteins or to modify the partition coefficient of polar analytes in extraction steps [18]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For clean-up and pre-concentration of samples to remove interfering matrix ions and compounds [19]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for identifying and addressing matrix interference in GICA.

Matrix Interference Troubleshooting Workflow

FAQ: Troubleshooting Partitioning Experiments

FAQ 1: How can I adjust the partition coefficient (K) of a highly non-polar analyte to improve its analysis? A common issue with non-polar analytes is an excessively high partition coefficient (K), which can lead to poor resolution in techniques like Countercurrent Chromatography (CCC) and complete partitioning into the least polar phase, making separation from other compounds difficult [20].

- Solution: Consider using a combined conventional and co-current CCC (CCC + ccCCC) mode. This approach helps manage compounds with high K values by starting the separation in normal CCC mode and then rapidly eluting in co-current mode. This combination has proven effective for separating challenging compounds like oleic acid and palmitic acid methyl esters, which have K values greater than 10 in n-hexane/acetonitrile systems [20].

- Preventative Tip: The K value is roughly correlated with the logarithmic octanol-water coefficient (log KOW). For highly lipophilic compounds (log KOW 6–22), standard biphasic solvent systems are often insufficient, and advanced modes like CCC+ccCCC should be planned for during method development [20].

FAQ 2: My Gold Immunochromatographic Assay (GICA) for a small molecule in a complex sample shows high background. How can I reduce this matrix interference? Matrix interference, particularly from lipid co-extracts, is a frequent problem in immunoassays, leading to inaccurate results [8].

- Solution: Implement a pH-dependent extraction and purification strategy. This method leverages the analyte's ionization state (LogD) to precisely control its partitioning between phases.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Adjust the pH of your sample solution to a value where your target analyte is in its neutral form, while the interfering compounds (e.g., fatty acids) are ionized.

- Perform a liquid-liquid extraction with a suitable organic solvent. At this pH, your neutral analyte will partition into the organic phase, while the ionized interferents remain in the aqueous phase.

- Back-extract the analyte by adjusting the pH of the organic phase to a value where the analyte becomes ionized and partitions back into a clean aqueous phase.

- This strategy was successfully used to eliminate lipid matrix interference in the detection of ethoxyquin in aquatic products, achieving a detection limit of 10 μg/kg [8].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Optimization Tool: Use experimental designs like Plackett-Burman and Box-Behnken to rapidly establish the optimal pH and other pretreatment conditions [8].

FAQ 3: I am adding surfactants to my system, but my drug's partition coefficient (K) is decreasing unexpectedly. Is this normal? Yes, this is an expected phenomenon. Surfactants can significantly alter a compound's apparent partition coefficient by forming complexes or through various intermolecular interactions [21].

- Explanation: The presence of surfactants, even at concentrations below their Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC), can reduce the observed oil-water partition coefficient (Koil/w). This occurs because the surfactant monomers can interact with the drug molecule (via hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, or dispersion forces), increasing its effective solubility in the aqueous phase and thus reducing its tendency to partition into the oil phase [21].

- Considerations:

- The extent of reduction depends on the charge of the surfactant headgroup relative to your drug's charge. For example, the drug naproxen showed different Koil/w values in the presence of cationic (DTAB), anionic (SDS), and non-ionic (Brij 35) surfactants [21].

- If your goal is to enhance the solubility of a lipophilic drug, using surfactants above their CMC to form micelles is a standard approach. However, for partitioning experiments, be aware that surfactants will almost certainly alter the measured K value.

FAQ 4: How do I choose between an edible oil and n-octanol for partition coefficient studies relevant to human biology? For predicting the distribution of compounds into human tissues, edible oils (like olive oil) are often superior to n-octanol [22].

- Rationale: Edible oils, which are composed mainly of triglycerides, better represent the lipid composition of human adipose tissue. Consequently, partition constants determined in olive oil-water systems (PWOIL) have been shown to be more accurate for predicting adipose tissue:plasma partition coefficients than the traditional n-octanol-water system (PWOCT) [22].

- Decision Guide:

- Use n-octanol/water for initial screens of hydrophobicity and for QSAR models that rely on large historical datasets (log P).

- Use edible oil/water (e.g., olive, sesame, sunflower oil) when your research is focused on modeling biological distribution, fat storage, or bioavailability in humans or animals [21] [22].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Determining Edible Oil-Water Partition Coefficients in Surfactant Media

This protocol is adapted from studies on partitioning naproxen and is suitable for analyzing drug distribution in complex media [21].

Principle: The partition coefficient (Koil/w) is determined at equilibrium by measuring the drug concentration in both edible oil and aqueous surfactant phases using UV-Vis spectrometry and the shake-flask method.

Workflow Diagram:

Figure 1: Oil-Water Partition Coefficient Workflow Key Materials:

- Drug Compound: The analyte of interest (e.g., Naproxen).

- Edible Oils: Olive oil, sesame oil, sunflower oil.

- Surfactants: Ionic (SDS, DTAB) and non-ionic (Brij 35).

- Buffer: To maintain pH.

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer: For concentration measurement.

Key Steps:

- Prepare a known concentration of the drug in a buffer solution containing the surfactant at a concentration below its CMC.

- Combine the drug solution with an equal volume of edible oil in a sealed vial.

- Shake the mixture for 24 hours at a constant temperature (e.g., 25.0 °C) to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Centrifuge the mixture to achieve complete phase separation.

- Carefully sample the aqueous phase and measure the drug concentration using UV-Vis spectrometry.

- Determine the drug concentration in the oil phase by mass balance (initial amount minus amount in water).

- Calculate the partition coefficient as Koil/w = [C]oil / [C]water, often reported in logarithmic form (log Koil/w).

Protocol 2: pH-Dependent Extraction to Eliminate Matrix Interference

This protocol is ideal for cleaning up complex samples, such as aquatic products, prior to immunoassay analysis [8].

Principle: The partition coefficient (LogD) of an ionizable analyte is pH-dependent. By performing extractions at carefully selected pH values, the analyte can be separated from interfering compounds.

Workflow Diagram:

Figure 2: pH-Dependent Extraction Process Key Steps:

- Homogenize the sample and extract the target analyte using a suitable solvent.

- Adjust the pH of the extract to a predetermined value (pH A) where the target analyte is neutral, but major interferents (like fatty acids) are ionized.

- Perform a liquid-liquid extraction. The neutral analyte will partition into the organic phase, while ionic interferents remain in the aqueous phase. Discard the aqueous waste.

- Adjust the pH of the organic phase containing the analyte to a different value (pH B) where the analyte becomes ionized.

- Back-extract the now-ionized analyte into a clean aqueous phase. The organic phase can be discarded.

- The resulting aqueous phase contains a purified and concentrated form of the analyte, which can be directly analyzed by GICA or other methods with minimal matrix interference.

Optimization: Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM), such as a Box-Behnken design, to efficiently find the optimal pH values and other extraction parameters (e.g., solvent ratio, time) for your specific analyte [8].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Effect of Surfactants on Naproxen Partitioning in Edible Oil-Water Systems

This table summarizes how different surfactants below their CMC reduce the partition coefficient of the drug naproxen. Data is presented as log K_{oil/w} at 25.0 °C [21].

| Surfactant Type | Surfactant Name | Concentration (mM) | Olive Oil | Sesame Oil | Sunflower Oil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (Control) | --- | 0.00 | 2.11 | 1.97 | 1.91 |

| Cationic | DTAB | 2.00 | 1.69 | 1.61 | 1.56 |

| Anionic | SDS | 2.00 | 1.82 | 1.74 | 1.68 |

| Non-ionic | Brij 35 | 0.02 | 1.76 | 1.69 | 1.63 |

Key Takeaway: All surfactants reduce naproxen's lipophilicity, with cationic DTAB showing the strongest effect in the systems studied. The order of partitioning is consistent: olive oil > sesame oil > sunflower oil, regardless of surfactant presence [21].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Partitioning Experiments

A toolkit of common reagents and their roles in partitioning studies.

| Research Reagent | Function / Utility in Partitioning Studies | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Edible Oils (Olive, Sunflower) | More biologically relevant lipid phase for predicting distribution into human tissues compared to n-octanol [22]. | Predicting adipose tissue:plasma partition coefficients [22]. |

| Ionic Surfactants (SDS, DTAB) | Modifies the apparent partition coefficient by interacting with ionizable drugs via electrostatic forces [21]. | Studying how formulation excipients can alter drug distribution [21]. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactant (Brij 35) | Modifies partition coefficient via hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces; often has a lower CMC than ionic surfactants [21]. | Solubilizing poorly soluble drugs and studying their release. |

| n-Hexane / Acetonitrile | Forms a biphasic solvent system for CCC; useful for separating very non-polar compounds [20]. | Separating lipid compounds like fatty acid methyl esters [20]. |

Practical Strategies for Modifying Partition Behavior in Research and Development

Leveraging pH-Dependent Partitioning (LogD) for Precision Control

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between LogP and LogD, and why does it matter for polar analytes? LogP describes the partition coefficient of a compound in its neutral, unionized state between octanol and water. In contrast, LogD is the distribution coefficient that accounts for all forms of a compound (ionized, partially ionized, and unionized) at a specific pH [1]. For polar analytes, which often contain ionizable groups, LogD provides a more accurate picture of lipophilicity because it reflects the pH-dependent speciation that occurs in real biological and experimental systems. Relying solely on LogP can be misleading, as a compound's neutral form may be virtually non-existent at physiologically relevant pH, drastically altering its apparent lipophilicity, membrane permeability, and solubility [1].

Q2: How can pH adjustment be used to reduce matrix interference in analytical methods? Matrix interference, often from lipid co-extracts, can be effectively mitigated by designing an extraction and purification strategy based on pH-dependent LogD [8]. By adjusting the pH of the solution, you can shift the equilibrium of your target ionizable analyte, thereby altering its partition coefficient. This allows you to selectively extract the target compound into the desired phase (e.g., organic solvent) while leaving interfering matrix components behind in the aqueous phase. A study on ethoxyquin detection successfully used this principle to eliminate lipid interference and achieve a low detection limit [8].

Q3: My LogD measurement results are inconsistent. What are common sources of error? A primary source of error in shake-flask LogD determination is poor compound solubility [23]. If a compound has limited solubility, it cannot properly distribute between the octanol and buffer phases, leading to inaccurate measurements. Filtering out compounds with kinetic solubility below a certain threshold (e.g., < 25-100 µM) has been shown to reduce standard deviation and minimize outliers without significantly affecting the median ΔLogD value [23]. Other common laboratory errors that can affect results include instrument calibration errors, improper specimen handling, and the use of expired reagents [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inaccurate LogD Predictions for Novel Compounds

Symptoms:

- Significant discrepancies between in-silico LogD predictions and experimental results.

- Poor correlation between a compound's predicted and observed behavior in biological assays (e.g., permeability, toxicity).

Resolution:

- Action 1: For ionizable compounds, ensure you are using LogD at the relevant pH (e.g., LogD7.4 for physiological conditions) and not LogP for your assessments [1] [25].

- Action 2: Leverage advanced prediction models that incorporate multiple data sources. Modern QSPR models use techniques like transfer learning from chromatographic retention time data and multitask learning with LogP and microscopic pKa values to improve accuracy and generalizability [25].

- Action 3: Consult tables of experimentally determined LogD contributions for common substituents. These tables, derived from large datasets of pharmaceutically relevant compounds, provide median ΔLogD values that can serve as a valuable benchmark for manual calculation and intuition [23].

Problem 2: Poor Extraction Efficiency During Sample Preparation

Symptoms:

- Low recovery of the target analyte.

- High background noise or interference from matrix components in subsequent analysis (e.g., chromatography).

Resolution:

- Action 1: Map the LogD profile of your analyte. Determine how its LogD changes across a pH range to identify the "sweet spot" for extraction [8] [1].

- Action 2: For acidic or basic compounds, adjust the pH of your aqueous phase to suppress the ionization of your target analyte. A lower pH will shift acids towards their neutral, more lipophilic form (higher LogD), favoring partitioning into organic solvent. A higher pH will do the same for bases [26] [8].

- Action 3: Use an experimental design methodology, such as Response Surface Methodology (RSM), to rapidly optimize the extraction parameters (e.g., pH, solvent type, mixing time) for a streamlined and effective pretreatment protocol [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and computational tools used in LogD research.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1-Octanol/Water System | The standard shake-flask setup for experimentally determining LogP and LogD values [27] [25]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | A chromatographic technique used as an indirect method for LogD determination; can be automated for higher throughput [25]. |

| pH Buffers | Aqueous solutions with defined pH values (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate buffer) used to control the ionization state of analytes during LogD measurement [25]. |

| Physicochemical Prediction Software (e.g., ACD/Percepta) | Software platforms that provide in-silico predictions of LogD, LogP, pKa, and other vital properties to guide experimental design [1] [25]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A digital system for standardizing data entry, managing experimental protocols, and tracking results to reduce human error and improve reproducibility [28]. |

Experimental Workflow and Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a general workflow for leveraging LogD in experimental planning, from in-silico analysis to practical application.

LogD Contribution of Common Functional Groups

The table below summarizes the median lipophilicity contributions (ΔLogD7.4) of common substituents, providing a reference for rational design to reduce the partition coefficient of polar analytes. This data is derived from molecular matched pair analysis of pharmaceutically relevant compounds [23].

| Functional Group | Radius = 0Median ΔLogD7.4 (Count) | Radius = 3Median ΔLogD7.4 (Count) |

|---|---|---|

| Phenyl | +2.39 (3036) | +2.34 (731) |

| Methyl | +0.56 (18757) | +0.69 (3719) |

| Chloro | +0.71 (4046) | +0.77 (1144) |

| Fluoro | +0.23 (5097) | +0.15 (1715) |

| Methoxy | +0.10 (2637) | +0.22 (707) |

| Hydroxyl | -0.41 (4890) | -0.33 (1198) |

| Cyano | -0.27 (1314) | -0.27 (332) |

| Carboxylic Acid | -1.18 (2185) | -1.31 (337) |

| Primary Amine | -1.36 (3753) | -1.40 (720) |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput LogD Measurement in Mixtures

This protocol adapts the traditional shake-flask method for higher efficiency by measuring the distribution coefficients of compound mixtures using LC-MS/MS analysis [27].

1. Principle: Compounds are partitioned between 1-octanol and an aqueous buffer at a defined pH (e.g., 7.4). The concentration ratio in each phase is determined chromatographically to calculate the distribution coefficient.

2. Materials:

- Test compounds (pure, can be mixed in groups of up to 10)

- 1-Octanol (HPLC grade)

- Aqueous buffer (e.g., 0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- LC vials, microcentrifuge tubes, and a vortex mixer

- Centrifuge

- HPLC system coupled with a tandem mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Prepare stock solutions of each compound in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO).

- Step 2: In a microcentrifuge tube, add 0.5 mL of octanol pre-saturated with buffer and 0.5 mL of buffer pre-saturated with octanol.

- Step 3: Spike a mixture of compounds (up to 10) into the tube. The final concentration of each compound should be within its linear dynamic range on the LC-MS/MS and below its solubility limit.

- Step 4: Vortex the mixture vigorously for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to ensure equilibrium is reached.

- Step 5: Centrifuge the tubes at high speed (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 10-15 minutes) to achieve complete phase separation.

- Step 6: Carefully separate the two phases. Dilute samples from both the octanol and aqueous phases as needed with a compatible LC-MS solvent.

- Step 7: Analyze the diluted samples using the LC-MS/MS method. Quantify the concentration of each compound in both phases using pre-established calibration curves.

4. Calculations: For each compound, the LogD is calculated as: LogD = Log10 ( Concentration in Octanol Phase / Concentration in Aqueous Buffer Phase )

5. Critical Notes:

- Ion Pair Partitioning: Be aware that interactions between compounds within a mixture could potentially lead to ion pair partitioning, which might yield erroneous results. The likelihood of this should be assessed based on the compounds' chemistries [27].

- Solubility Check: As poor solubility is a major source of error, ensure compounds are fully soluble in the test system. Filtering out low-solubility compounds (< 100 µM) prior to measurement is recommended for reliable data [23].

Utilizing Surfactants and Micellar Systems to Alter Solubility and Partitioning

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Why is my surfactant treatment not effectively reducing the partition coefficient (K) of my target polar analyte?

Several factors could be responsible for this issue. Please consult the following troubleshooting guide:

- Check Surfactant Concentration: Ensure your surfactant concentration is above the Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC). Micelles only form above the CMC and are the primary structures for solubilizing compounds and altering partitioning. The CMC can be affected by temperature, pH, and ionic strength [29].

- Verify Solution pH Relative to Analyte pKa: The ionization state of your analyte, controlled by pH, is critical. For acidic analytes, lower pH (below pKa) promotes the neutral, more hydrophobic form, which partitions more effectively into micelles. For basic analytes, a higher pH (above pKa) is required. A shift in pH can lead to a several-fold change in solubilization efficiency [29] [30] [31].

- Evaluate Ionic Strength: High ionic strength can decrease the solubility of ionic species (salting-out effect) but can also screen electrostatic repulsions in ionic micelles, affecting their structure and solubilization capacity. The impact can be significant, with one study showing a more than 150% increase in a partition coefficient with increased ionic strength [29].

- Confirm Surfactant Type and Analyte Charge: Match the surfactant type to your analyte. Ionic surfactants can electrostatically repel analytes of the same charge, reducing partitioning. Non-ionic surfactants are often less inhibitory to biological processes and may provide a more neutral environment for solubilization [21] [29].

- Account for Surfactant Partitioning Loss: A significant fraction of the dosed surfactant (as much as 10% by weight) may partition into a non-aqueous phase liquid (NAPL) or other organic phases present in your system. This represents a "loss" of aqueous surfactant, reducing the amount available to form micelles for solubilization [29].

FAQ: How can I overcome matrix interference from lipid co-extracts in my analysis?

Matrix interference is a common challenge. A novel strategy involves designing a pH-dependent extraction to leverage the analyte's ionization state:

- Principle: Adjust the pH of the extraction medium to control the hydrophobicity (LogD) of your target analyte. This allows you to selectively partition the analyte into the desired phase while leaving interfering lipid components behind [8].

- Application: This method has been successfully used to eliminate matrix interference from lipid co-extracts in complex samples like aquatic products, achieving detection limits as low as 10 μg/kg [8].

FAQ: My mixed surfactant system is underperforming compared to theoretical predictions. What could be wrong?

The formation and structure of mixed micelles are complex and can sometimes lead to negative mixing effects.

- Investigate Micelle Structure: In some mixed systems (e.g., with a high molar ratio of ionic surfactant), separate micelles of different compositions may form instead of a single, homogeneous mixed micelle. This less stable or non-ideal structure can result in a lower-than-expected solubilization capacity [32].

- System Optimization: Use experimental designs like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to rapidly establish the optimal surfactant ratios and concentrations for your specific system, rather than relying solely on ideal mixing rules [8].

Quantitative Data on Partitioning Behavior

The following tables summarize experimental data on how surfactants influence partition coefficients under various conditions.

Table 1: Impact of Surfactant Type on Drug Partitioning in Edible Oil-Water Systems Data for the drug Naproxen in the presence of surfactants at concentrations below their CMC [21].

| Surfactant Type | Surfactant Name | Headgroup Charge | Impact on log Koil/w of Naproxen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic | DTAB | Positive | Reduces partition coefficient |

| Anionic | SDS | Negative | Reduces partition coefficient |

| Non-ionic | Brij 35 | Neutral | Reduces partition coefficient |

Table 2: Effect of pH and Surfactant on Pentachlorophenol (PCP) Partitioning Data showing the enhancement of PCP aqueous concentration by Tergitol NP-10 (TNP10) surfactant relative to its aqueous solubility. PCP pKa ≈ 4.7 [29].

| Aqueous TNP10 Concentration | pH | Fold Increase in Aqueous PCP Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| 1200 mg/L | 5 | 14-fold |

| 1200 mg/L | 7 | 2 to 3-fold |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Partition Coefficient in a Micellar System using the Shake-Flask Method

This is a fundamental technique for measuring the partition coefficient of a compound between a micellar solution and another phase [30].

- Preparation: Prepare a buffered surfactant solution at a concentration well above its CMC. The buffer should be chosen to maintain the desired pH, keeping the analyte in its desired ionization state.

- Equilibration: Add the target analyte to the solution. For a water-NAPL or water-oil system, add the immiscible organic phase in a known volume ratio (e.g., 1:1). Seal the container and shake it vigorously at a constant temperature to reach partitioning equilibrium.

- Separation: Allow the phases to separate completely. This may involve centrifugation.

- Analysis: Carefully sample each phase and use an appropriate analytical technique (e.g., UV-Vis spectrometry, HPLC) to determine the equilibrium concentration of the analyte in each phase [21].

- Calculation: Calculate the partition coefficient, K. For a micelle-water system, K is the ratio of the analyte concentration in the micellar phase to its concentration in the aqueous phase. For an oil-water system, Koil/w = [Analyte]oil / [Analyte]water [21].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Surfactant-Assisted Extraction of a Polar Analytic using pH Control

This protocol leverages pH to control analyte hydrophobicity for improved extraction [8] [31].

- Analyte Characterization: Determine the pKa of your target analyte using literature or predictive software.

- pH Adjustment: For an acidic analyte, acidify the aqueous sample to a pH at least 2 units below its pKa to ensure it is predominantly neutral. For a basic analyte, adjust the pH to at least 2 units above its pKa [31].

- Extraction: Add a suitable organic solvent (e.g., octanol, hexane) and the surfactant to the pH-adjusted sample. Shake to equilibrate.

- Back-Extraction (For Specificity): To improve specificity, perform a back-extraction. After the initial extraction, separate the organic phase and mix it with a fresh aqueous phase at a pH where the analyte is ionized (e.g., pH > pKa for acids). The analyte will transfer back into the fresh aqueous phase, leaving neutral interferents in the organic solvent [31].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing a surfactant-based system aimed at reducing the partition coefficient of a polar analyte.

Surfactant System Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Surfactant and Micellar Partitioning Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Tergitol NP-10 | A non-ionic alkylphenol ethoxylate surfactant used to enhance solubilization of hydrophobic compounds like pentachlorophenol from NAPLs [29]. |

| Brij 35 | A non-ionic polyethylene glycol dodecyl ether surfactant. Often used in mixed systems and studies of drug partitioning due to its well-defined structure [21] [32]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | A common anionic surfactant used in micelle formation studies and mixed systems. Can electrostatically repel anionic analytes [21] [32]. |

| DTAB (Dodecyltrimethylammonium Bromide) | A cationic surfactant used to study the effect of headgroup charge on the partitioning of ionic and non-ionic drugs [21]. |

| HTAB/CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide) | A cationic surfactant with a longer tail, commonly used in Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography (MEKC) for determining micelle-water partition coefficients [33]. |

| Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC) | A liquid-liquid chromatography technique that uses a liquid stationary phase, allowing for extreme pH manipulation without damaging the system, ideal for studying ionizable compounds [30]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

HILIC Method Troubleshooting FAQ

Q: What are the common causes of little or no retention on a HILIC column? [34]

A: Retention problems in HILIC often stem from:

- Improper column conditioning: New columns must be properly conditioned before first use to establish the essential water layer on the stationary phase [35] [34].

- Incorrect mobile phase gradient: Using a reversed-phase gradient (low organic to high organic) instead of a HILIC gradient (high organic to higher aqueous). HILIC always begins with ~95% acetonitrile (weak solvent) and ~5% aqueous buffered solution (strong solvent) [34].

- Inadequate column re-equilibration: Insufficient re-equilibration between gradient runs prevents the water layer from fully reestablishing, leading to retention time drift [35] [34].

Q: Why do I experience poor peak shape in HILIC separations? [35] [34]

A: Peak shape issues typically result from:

- Sample solvent mismatch: The injection solvent should closely match the initial mobile phase conditions (high in organic content). Samples prepared in 100% aqueous solvent cause peak distortion, early elution, and reduced sensitivity [35].

- Improper column conditioning: Similar to retention issues, failing to fully condition the column initially can also manifest as poor peak shape [34].

- System band-spreading: Poor connections in the flow path can cause band broadening, affecting any LC separation mode [34].

Q: How does mobile phase pH affect HILIC separations? [35]

A: pH effects are analyte-dependent in HILIC due to several factors:

- The high organic solvent content raises the effective pH of the mobile phase by 1-1.5 units compared to the aqueous portion alone [35].

- The charge state of both the analyte and stationary phase changes with pH. For bare silica columns (pKa 3.8-4.5), the surface is neutral at very acidic pH and becomes negatively charged as pH increases above 4.5 [35].

- Analytes with protonated amine or quaternary amine groups interact well with negatively charged silica surfaces, making them good candidates for HILIC analysis [35].

Method Development Guide: Choosing Between HILIC and Mixed-Mode Chromatography

Q: When should I choose HILIC over mixed-mode chromatography, and vice versa? [36] [37]

A: The choice depends on your analyte properties and separation goals:

Table: Comparison of HILIC and Mixed-Mode Chromatography Techniques

| Parameter | HILIC | Mixed-Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Best For | Polar, hydrophilic analytes [36] | Mixtures of polar, ionic, and nonpolar compounds [37] |

| Retention Mechanism | Liquid-liquid partitioning, hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole, ion exchange [35] | Combined reversed-phase and ion-exchange mechanisms [36] [37] |

| Mobile Phase | Acetonitrile-rich (>80%), water-miscible [36] | Adjustable organic solvent, pH, and ionic strength [37] |

| Strengths | Excellent for sugars, metabolites, amino acids; Enhanced MS sensitivity [36] | Single method for diverse analytes; No ion-pairing agents needed [37] |

| Limitations | Analyte solubility in organic solvents; Equilibration time [36] | Batch-to-batch reproducibility concerns [36] |

Experimental Protocols

Essential HILIC Method Establishment Protocol

Column Conditioning and Equilibration [35]:

Initial Conditioning:

- For isocratic methods: Flush with at least 50 column volumes of mobile phase

- For gradient methods: Perform at least 10 blank injections running the full-time program

- Calculation example: For a 100 mm × 2.1 mm ID column (volume = 0.2 mL) at 0.30 mL/min flow rate: 50 column volumes = 10 mL, requiring 33 minutes conditioning time

Between-Injection Equilibration:

- Equilibrate with minimum 10 column volumes when gradient returns to initial conditions

- For the same column above: 10 column volumes = 2 mL, requiring 7 minutes re-equilibration time at 0.30 mL/min

- Note: Required volumes are analyte-dependent and must be verified during method development

Injection Solvent Preparation [35] [36]:

- Prepare sample in solvent matching initial mobile phase conditions (typically ≥75% acetonitrile)

- For best results: Use 75/25 acetonitrile-methanol mix for most polar analytes [36]

- Avoid 100% aqueous injection solvents which cause poor peak shape and early elution

Mobile Phase and Buffer Preparation [35]:

- Use volatile buffers (ammonium formate, ammonium acetate) for MS compatibility

- Start with 10 mM buffer concentration

- Buffer both mobile phases equally to maintain constant ionic strength during gradients

- Avoid high buffer concentrations that can cause precipitation in high organic content or reduce analyte retention

Partition Coefficient Manipulation Protocol for Polar Analytes

The following experimental workflow demonstrates how to systematically reduce partition coefficients to improve polar analyte separation:

Partition Coefficient (LogD) Optimization Steps [38]:

pH-Dependent LogD Manipulation:

- For basic analytes with pKa ~5-9: Lower pH to protonate amines, increasing aqueous solubility and reducing LogD [38]

- For acidic analytes: Raise pH to deprotonate acids, increasing aqueous solubility

- Experiment with pH range 3-8 while monitoring retention and peak shape

Buffer Selection for LogD Control:

Temperature Optimization:

- HILIC columns can typically operate up to 80°C [39]

- Higher temperatures generally reduce retention times and may improve efficiency

- Study temperature effects from 25°C to 60°C as starting point

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for HILIC and Mixed-Mode Separations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bare Silica HILIC Columns | Polar stationary phase for diverse HILIC applications [35] | Provides ion-exchange and partitioning mechanisms; pKa 3.8-4.5 [35] |

| Amide-80 Stationary Phase | Carbamoyl-functionalized silica for HILIC [39] | Polar groups hydrogen bond with analytes; pH range 2.5-7.5 [39] |

| Zwitterionic HILIC Phases | Sulfobetaine ligands for unique selectivity [36] | Incorporated in Atlantis Premier BEH Z-HILIC columns; reduces NSA [36] |

| Mixed-Mode Columns | Combined RP/IEX mechanisms [37] | Embedded/tipped ligands for simultaneous polar/nonpolar separation [37] |

| Ammonium Formate | Volatile buffer for MS-compatible methods [35] | Suitable for positive and negative ion modes; start at 10 mM concentration [35] |

| Ammonium Acetate | Alternative volatile buffer [35] | Wider pH range; good for various applications |

| T3 Reversed-Phase Columns | Enhanced polar compound retention in RP [36] | Lower C18 density, larger pores reduce dewetting [36] |

| CORTECS T3 Columns | Solid-core technology for 100% aqueous compatibility [36] | Excellent peak shape across wide pH range [36] |

Advanced Technical Notes

Systematic Column Comparison Framework

For objective comparison of multiple stationary phases for polar basic analytes, implement this ranking system [40]:

- Test Solution Preparation: Combine 10 polar basic components covering a range of physicochemical properties

- Multi-Condition Testing: Evaluate each column at acidic, near-neutral, and basic pH conditions

- Ranking Parameters: Assess peak shapes and resolutions quantitatively

- Scoring System: Rank columns for each analyte and condition to identify optimal stationary phase

Decision Framework for Polar Analyte Separation Challenges

The following decision diagram outlines the systematic approach to addressing polar compound separation problems:

Critical Method Development Considerations

Mobile Phase Preparation for HILIC [35] [36]:

- Always use aqueous buffers to form stable water layer on stationary phase

- Buffer both mobile phases equally for consistent MS detector response

- Filter through 0.22 µm membrane to prevent column frit blockage

Column Equilibration Verification [35]:

- Monitor retention time reproducibility across 5-10 injections

- Retention times should vary by <1% when properly equilibrated

- Re-equilibration time is analyte-dependent - require longer for some compounds

Sample Preparation Guidelines [35]:

- For solid-phase extraction: Elute in highly organic solvent compatible with HILIC

- For liquid-liquid extraction: Use pH adjustment to manipulate partition coefficients [38]

- Evaporate and reconstitute in appropriate HILIC-compatible solvent if needed

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

How can I improve the bioavailability of a drug candidate that is too lipophilic?

A high LogP/LogD often leads to poor aqueous solubility, which limits absorption. The primary strategy is to reduce the molecule's lipophilicity.

- Diagnosis: The candidate likely has a LogP value significantly greater than 5 [41].

- Solution: Introduce polar or ionizable groups into the molecular structure. A notable case is the optimization of sertraline. Its initial LogP of 5.1 was reduced to a LogD of 2.8 at pH 7.4 by fine-tuning the position of chlorine substituents. This modification enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration while reducing overall lipophilicity [41].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesize Analogues: Prepare a series of analogues by introducing polar functional groups (e.g., tetrazole, amines, hydroxyls) or adjusting existing hydrophobic groups.

- Measure LogD: Determine the LogD at pH 7.4 using established methods like shake-flask or chromatographic techniques (e.g., reversed-phase HPLC).

- Assess Solubility: Evaluate aqueous solubility for each analogue.

- Evaluate Permeability: Use models like Caco-2 or PAMPA to confirm that permeability remains acceptable.

- Select Leads: Choose candidates with an optimal LogD (typically 1-3) that maintain good permeability and show improved solubility [41] [42].

What is the best approach to balance solubility and permeability for a new chemical entity?

The goal is to find a balance where the drug is soluble enough in gastrointestinal fluids and can also permeate through cell membranes.

- Diagnosis: The compound may have good solubility but poor permeability (or vice versa), often indicated by a suboptimal LogD value.

- Solution: Aim for a LogD in the range of 1 to 3, which generally offers a good compromise [41] [42]. The development of imatinib (Gleevec) involved precisely this kind of LogD optimization to ensure effective oral bioavailability by balancing these two properties [41].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Property Modeling: Use in-silico tools early in the design process to predict LogD and solubility [43].

- Design & Synthesize: Create a focused library of compounds designed to systematically vary lipophilicity.

- High-Throughput Screening: Measure LogD (at pH 7.4) and kinetic solubility in parallel for all library members.

- Data Analysis: Plot solubility and permeability against LogD to identify the "sweet spot" for your chemical series.

- Iterate: Use the data to guide further rounds of chemical synthesis and optimization.

How can I reduce matrix interference when detecting a polar analyte in a complex sample?

Matrix interference is a common issue in analytical methods for polar compounds. Leveraging pH-dependent partitioning can be a powerful solution.

- Diagnosis: The analyte of interest is polar (low LogD) and co-extracts with interfering matrix components, leading to inaccurate results.

- Solution: Use a pH-dependent extraction strategy. A study on detecting ethoxyquin in aquatic products used the analyte's LogD range to design an extraction at a specific pH that effectively removed lipid co-extracts, eliminating matrix interference [8].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Determine pKa: Identify the pKa of your analyte to understand its ionization state at different pH levels.

- Model LogD: Calculate or measure the LogD profile across a pH range (e.g., pH 2 to 10).

- Screen Extraction pH: Perform extractions at different pH values and measure the recovery of the analyte and key interferents.

- Optimize: Use experimental designs like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to rapidly establish the optimal pH and solvent conditions that maximize analyte recovery and minimize interference [8].

- Validate: Confirm the method's effectiveness by testing with real samples and comparing to a standard method.

Quantitative Data from Optimization Case Studies

The following table summarizes successful LogP/LogD optimizations for several marketed drugs, detailing the specific structural modifications that led to improved properties [41].

Table 1: Successful LogP and LogD Optimization in Drug Development

| Drug / Candidate | Initial LogP/LogD | Optimized LogP/LogD (pH 7.4) | Key Structural Modification | Improvement Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sertraline | LogP: 5.1 | LogD: 2.8 | Fine-tuned halogen (chlorine) positioning | Enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration; reduced excessive lipophilicity [41]. |

| Valsartan | LogP: 4.5 | LogD: -0.95 | Added a tetrazole group (ionizable at physiological pH) | Achieved better oral bioavailability through pH-dependent solubility [41]. |

| Amlodipine | LogP: 3.0 | LogD: 1.5 | Introduced an aminoethoxy group | Enhanced membrane permeability while maintaining aqueous solubility [41]. |

| Atorvastatin | N/A | Optimized LogP | Targeted optimization of lipophilicity | Enhanced liver-targeting properties and minimized systemic side effects [41]. |

| Imatinib | N/A | Optimized LogD | Balanced solubility and permeability | Ensured effective oral bioavailability [41]. |

Essential Experimental Workflows

Workflow for LogD-Driven Bioavailability Optimization

This diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of designing, making, and testing compounds to achieve the ideal balance of properties for oral drugs.

Workflow for Analytical Method Development to Reduce Matrix Interference

This workflow outlines a strategy for developing a clean analytical method for polar analytes by exploiting pH-controlled partitioning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for LogP/LogD Research

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| n-Octanol and Aqueous Buffers | The two-phase solvent system used in the gold-standard shake-flask method to determine the partition/distribution coefficient [41]. |

| pH Buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Citrate) | Used to adjust the pH of the aqueous phase in LogD determinations, allowing measurement of the pH-dependent distribution of ionizable compounds [41] [30]. |

| Reversed-Phase HPLC Columns (e.g., C18) | Chromatographic stationary phases used to measure retention time, which can be correlated with LogP/LogD values, offering a high-throughput alternative to shake-flask [30]. |

| Solvatochromic Dyes (e.g., Reichardt's dye) | Probe molecules used to characterize the polarity of solvent systems by measuring shifts in their UV-Vis absorption maxima, helping to understand partitioning environments [44]. |

| In-silico Prediction Software (e.g., Percepta Platform) | Computational tools that use QSPR and machine learning to predict key physicochemical properties like LogP, LogD, and pKa, guiding molecular design before synthesis [45] [43]. |

Overcoming Common Challenges in Polar Analyte Separation and Analysis

Addressing Poor Retention and Peak Tailing in Reversed-Phase Chromatography

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What are the primary causes of poor retention for polar analytes in RPLC?

Poor retention of polar analytes in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) occurs because the standard hydrophobic interactions with C18 stationary phases are minimal for these compounds [46]. The dominant hydrophobic retention mechanism of RPLC offers limited ability to retain highly polar and/or charged analytes [46]. While techniques like HILIC or mixed-mode chromatography are often better suited for polar molecules, RPLC can be optimized to improve retention [7].

Why does peak tailing occur, and how can it be minimized?

Peak tailing, where the peak has a stretched trailing edge, is a common distortion that reduces resolution and quantitative accuracy [47] [48]. It is often measured by the asymmetry factor (As); a value greater than 1.2 is generally considered tailed, while values above 1.5 can be problematic for quantification [47] [49].

The primary chemical cause, especially for basic compounds, is unwanted secondary interactions with residual active sites on the silica-based stationary phase, particularly ionized silanol groups (-Si-OH) [47] [48] [50]. These silanols can become negatively charged at mobile phase pH >3, creating strong ionic interactions with basic analytes that delay elution and cause tailing [47] [49].

Strategies to minimize peak tailing include:

- Operating at low pH: Using a mobile phase pH below 3 suppresses silanol ionization, reducing ionic interactions. Use columns designed for low-pH stability, such as Agilent ZORBAX Stable Bond (SB) columns [47].

- Using advanced column chemistry: Select highly deactivated, "end-capped" columns (e.g., Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus) or columns with polar-embedded groups that shield basic compounds from silanols [47] [49].

- Optimizing mobile phase composition: Adequate buffer concentration can mask silanol effects, and using amine modifiers (like triethylamine) can block active sites, though this is less common with modern columns and unsuitable for mass spectrometry [48].

- Ensuring system integrity: Eliminate extra-column volume from tubing and fittings, avoid sample solvent mismatch, and prevent column overloading or contamination [50] [49].

When should I consider switching from a C18 column to another type?

Consider alternative stationary phases when optimizing mobile phase conditions on a C18 column fails to provide sufficient retention or acceptable peak shape for your polar analytes [7].

- Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC): HILIC is a primary alternative, using a polar stationary phase and water-miscible organic solvents. It provides strong retention for polar compounds through a combination of partitioning, adsorption, and ion-exchange mechanisms [46] [7].

- Mixed-Mode Chromatography (MMLC): These columns combine multiple retention mechanisms within a single column, such as reversed-phase/weak cation exchange (RP/WCX). They are particularly powerful for analyzing complex mixtures containing ions, neutrals, and bases of diverse polarity in a single run [46].

- Other Specialized Phases: Columns with phenyl, pentafluorophenyl (F5), or amide functionalities can offer different selectivity and improved performance for challenging polar analytes [7].

Experimental Protocols for Method Development

Systematic Column and Mobile Phase Scouting Protocol

This protocol is designed to efficiently identify the best chromatographic conditions for retaining and separating polar analytes with symmetric peak shapes.

Objective: To find the optimal combination of stationary phase and mobile phase pH for the analysis of polar basic molecules.

Materials:

- Test Analytes: A mixture of representative polar basic compounds (e.g., creatinine, agmatine, risperidone, pramipexole) [7].

- Columns to Evaluate:

- Standard C18 (e.g., Agilent Zorbax SB-C18)

- Advanced end-capped C18 (e.g., Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus)

- HILIC columns (e.g., bare silica, amide, zwitterionic)

- Mixed-mode columns (e.g., RP/WCX like Acclaim Mixed-Mode WCX-1)

- Mobile Phases: Aqueous buffers at pH 2.5, 4.5, and 7.0 (or higher for specialty columns), combined with acetonitrile or methanol.

- Instrumentation: HPLC or LC-MS system.

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate each column with the starting mobile phase condition for a sufficient time (at least 10-15 column volumes for HILIC) [51].

- Gradient Elution: Run a linear gradient from high organic (e.g., 95% ACN) to high aqueous (e.g., 95% buffer) for HILIC, or the reverse for RPLC, using each of the three pH buffers.

- Data Collection: Record chromatograms and measure for each analyte: retention time, peak asymmetry (As or Tailing Factor), and resolution from nearest neighbor.

- Analysis and Ranking: Rank the column/pH combinations based on peak shape and resolution. A simple scoring system can be developed where each condition is evaluated and the best overall performer is selected [7].

Workflow for Troubleshooting Peak Tailing

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step workflow for diagnosing and correcting peak tailing.

Data Presentation

Quantitative Comparison of Peak Tailing Mitigation Strategies

The following table summarizes the effectiveness of different approaches to resolve peak tailing, based on documented evidence.

| Strategy | Typical Improvement in Peak Asymmetry (As) | Key Considerations | Source Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Mobile Phase pH (pH <3) | As reduced from 2.35 to 1.33 for methamphetamine [47] | Only for acid-stable columns; may reduce retention for basic analytes [47]. | |

| Use of Highly Deactivated (End-capped) Columns | Significant improvement, yielding As <1.5 even for problematic bases [47] | The gold standard for new methods; various brands available (e.g., ZORBAX Eclipse Plus) [47] [49]. | |

| Mixed-Mode QSRR Model for Optimization | Local QSRR models achieved R² of 0.996 for retention prediction [46] | Uses machine learning to model complex interactions; requires specialized expertise [46]. | |

| Eliminating Borosilicate Glass Bottles in HILIC | Retention time RSD improved from 8.4% to 0.14% [51] | Critical for HILIC retention repeatability; use PFA plastic bottles instead [51]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Acclaim Mixed-Mode WCX-1 Column | A mixed-mode stationary phase combining reversed-phase (C18) and weak cation-exchange ligands. Enables tunable retention via pH and solvent strength for diverse analytes [46]. |

| High-Purity, Low-Activity Silica Columns | Columns based on high-purity "Type B" silica with extensive end-capping (e.g., ZORBAX Eclipse Plus). Minimizes secondary interactions with residual silanols, reducing tailing for basic compounds [47] [48]. |

| Stable Low-pH Buffers | Buffers like phosphate or formate at pH 2.5-3.0. Suppresses ionization of silanol groups and many basic analytes, minimizing ionic interactions that cause tailing [47] [49]. |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents | Reagents such as heptafluorobutyric acid. Adds charge to the mobile phase to mask analyte interactions or impart retention for ionic polar compounds [7]. |

| PFA Solvent Bottles | Plastic bottles made of a copolymer of tetrafluoroethylene and perfluoroalkoxyethylene. Prevents leaching of ions from borosilicate glass, crucial for achieving repeatable retention times in HILIC [51]. |

Core Concepts: Partition Coefficients and Matrix Interference

Understanding LogP, LogD, and Hydrophobicity

For researchers working to reduce the partition coefficient of polar analytes, a clear grasp of hydrophobicity metrics is fundamental. The following table outlines the key parameters.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Measuring Hydrophobicity and Partitioning

| Parameter | Definition | Dependence | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| LogP (KOW) | The partition coefficient of a chemical's neutral form between n-octanol and water [5] [52]. | Molecular size and polarity [53]. | Predicting the baseline hydrophobicity and lipophilicity of neutral compounds. |