Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning for Contaminant Source Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches for identifying and tracking contamination sources in environmental systems.

Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning for Contaminant Source Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide for Environmental Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches for identifying and tracking contamination sources in environmental systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and environmental professionals, it explores the foundational principles, practical methodologies, and validation frameworks essential for applying these techniques to complex contaminant data. By synthesizing current research and real-world applications—from water quality analysis to groundwater contamination—the review offers a systematic guide for selecting, optimizing, and validating machine learning models to translate complex chemical and microbial data into actionable environmental insights for improved decision-making and remediation strategies.

Understanding the Core Paradigms: From Labeled Data to Hidden Patterns

Defining the Machine Learning Landscape in Environmental Monitoring

Environmental monitoring is critical for understanding and addressing global challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution management. The advent of big data, collected from satellites, drones, and IoT-enabled sensor networks, has revolutionized this domain [1]. However, the sheer volume, complexity, and high-dimensionality of this environmental data pose significant challenges for traditional analytical methods. Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to extract meaningful patterns and insights from these complex datasets, enabling more accurate predictions, automated classifications, and data-driven decision-making for environmental protection [2] [1].

A central paradigm in applying ML to environmental science is the choice between supervised and unsupervised learning. Each approach offers distinct methodologies and advantages for tackling different types of problems, from predicting pollutant concentrations to identifying hidden patterns in contamination sources. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two ML approaches within the context of environmental monitoring, offering researchers a structured overview of their performance, applications, and implementation protocols to inform methodological selection for contaminant source tracking and related research.

Theoretical Foundations: Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning

Core Definitions and Workflows

In supervised learning, models are trained on labeled datasets where the target outcome (the "answer") is already known. The algorithm learns to map input features to these known outputs, and the resulting model is used to predict outcomes on new, unseen data. Common applications include classification (categorizing data) and regression (predicting continuous values) [3].

In unsupervised learning, models are applied to datasets without predefined labels. The algorithm explores the data to identify inherent structures, patterns, or groupings on its own. Key techniques include clustering (grouping similar data points) and dimensionality reduction (simplifying data while preserving its structure) [4] [5].

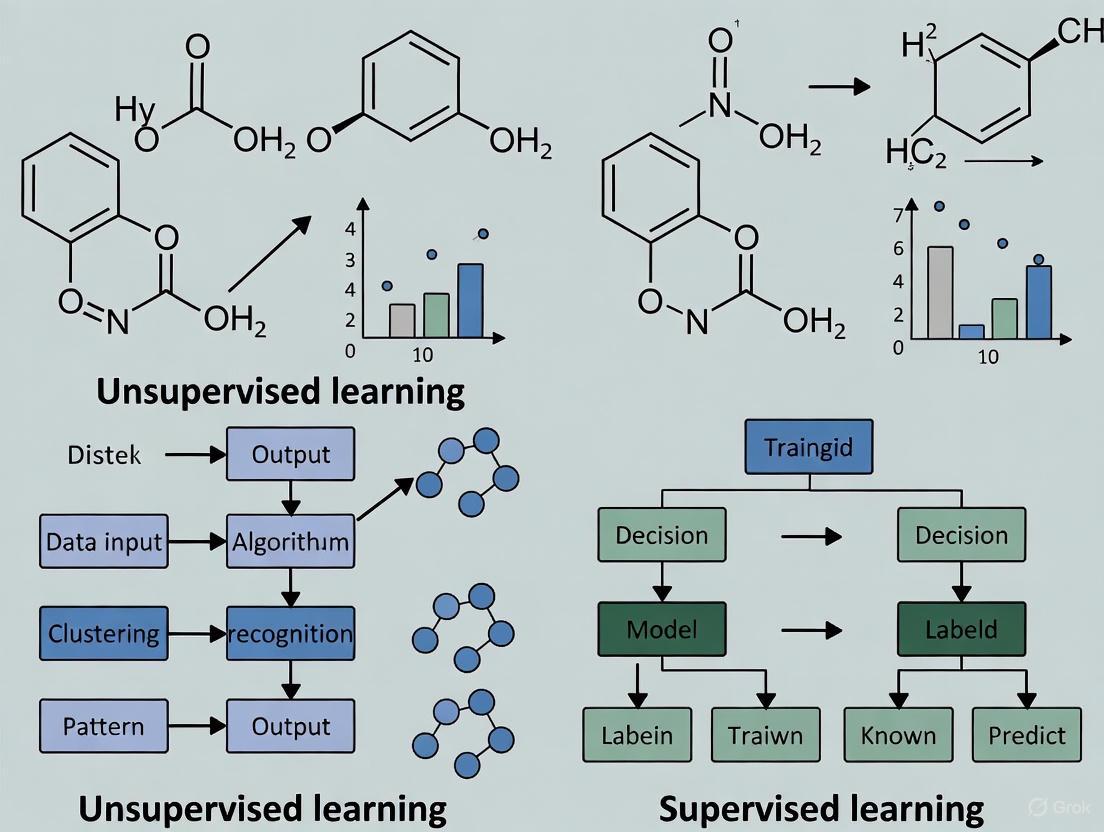

The logical relationship between these approaches and their typical workflows in an environmental monitoring context can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Strengths and Applicability

The choice between supervised and unsupervised learning is primarily determined by the research objective and data availability. Supervised learning is the preferred method when the goal is prediction or classification, and a reliable labeled dataset exists or can be created. For instance, predicting the Effluent Quality Index (EQI) of a wastewater treatment plant requires historical data where both input parameters and the resulting EQI are known [6] [7].

Conversely, unsupervised learning is ideal for exploratory data analysis, pattern discovery, and cases where labeled data is unavailable or costly to obtain. It is particularly valuable for identifying previously unknown contamination profiles or segmenting monitoring sites into meaningful groups based on multivariate environmental data [4] [5]. The two approaches can also be complementary; for example, clusters identified through unsupervised learning can be used to create labels for a subsequent supervised learning model.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Applications

The performance of supervised and unsupervised learning models varies significantly across different environmental monitoring tasks. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies, providing a basis for comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning Models in Environmental Monitoring

| Application Area | ML Approach | Specific Model(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effluent Quality Prediction | Supervised | XGBoost | R² = 0.813, MAPE = 6.11% | [6] [7] |

| Supervised | Support Vector Machine (SVR) | R² = 0.826 | [6] [7] | |

| Supervised | AdaBoost, BP-NN, Gradient Boosting | R²: 0.713 - 0.802 | [7] | |

| Microbial Source Tracking | Supervised | XGBoost | Average Accuracy = 88%, AUC = 0.88 | [3] |

| Supervised | Random Forest | Average Accuracy = 84%, AUC = 0.84 | [3] | |

| Indoor Air Pollution Analysis | Unsupervised | K-means, DBScan, Hierarchical | Evaluated with Davies–Bouldin Index, Silhouette Score | [5] |

| HV Insulator Contamination | Supervised | Decision Trees, Neural Networks | Accuracy > 98% | [8] |

| Environmental Factor Correlation | Unsupervised | K-means, PCA, DBSCAN | Effective for identifying pollution sources and assessing environmental quality. | [4] |

Analysis of Comparative Findings

The data illustrates a clear performance distinction. Supervised learning models excel in predictive accuracy when tasked with well-defined regression or classification problems. For instance, in effluent quality prediction, tree-based ensemble methods like XGBoost demonstrate an excellent balance of high explanatory power (R²) and low prediction error (MAPE) [6] [7]. Similarly, for classifying contamination levels on high-voltage insulators, supervised models can achieve exceptional accuracy exceeding 98% [8].

Unsupervised learning models, by contrast, are not evaluated by predictive accuracy but by metrics that quantify the quality of the discovered data structure. Studies in indoor air pollution and broader environmental factor analysis use metrics like the Silhouette Score and Davies–Bouldin Index to validate the coherence and separation of identified clusters [4] [5]. Their "success" is measured by the ability to reveal meaningful, interpretable patterns—such as distinguishing between air pollution profiles in different building microenvironments—without any prior labeling [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Supervised Learning: Effluent Quality Prediction

A typical supervised learning workflow for predicting a comprehensive water quality index, as demonstrated in studies on wastewater treatment plants, involves several key stages [7].

- 1. Data Collection and Target Variable Definition: Researchers collect historical data from monitoring sites. A critical step is defining a robust target variable. For instance, the Effluent Quality Index (EQI) integrates multiple pollutant concentrations (e.g., BOD, COD, TN, TP) and their environmental impacts into a single, comprehensive metric [7].

- 2. Data Preprocessing: This involves handling missing values, normalizing or standardizing features to ensure comparable scales, and potentially using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction [7] [3].

- 3. Model Training with Hyperparameter Tuning: Multiple algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, SVR, AdaBoost) are trained on a subset of the data. To ensure fair comparison and optimal performance, researchers employ techniques like

GridSearchCVwith k-fold cross-validation to systematically tune model hyperparameters [6] [7]. - 4. Model Validation and Performance Assessment: The trained models are evaluated on a held-out test dataset using a suite of metrics. Common metrics include R-squared (R²) to measure variance explained, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for prediction error, and Mean Bias Error (MBE) for systematic bias [7]. For classification tasks, Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) is a standard metric [3].

The following diagram illustrates this structured workflow.

Protocol for Unsupervised Learning: Contaminant Pattern Discovery

The application of unsupervised learning for discovering patterns in environmental data, such as indoor air pollution, follows a different pathway focused on exploration and discovery [5].

- 1. Multi-Variable Data Acquisition: Data is collected from multiple sensors measuring various parameters simultaneously. For air quality, this could include PM1, PM2.5, PM10, CO, CO₂, O₃, temperature, and relative humidity [5].

- 2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Scaling: Similar to supervised learning, data is cleaned and normalized. This step is crucial for clustering algorithms that are sensitive to the scale of features.

- 3. Pattern Discovery via Clustering/Dimensionality Reduction: Algorithms like K-means, DBScan, or hierarchical clustering are applied to group monitoring events or locations (microenvironments) with similar multivariate profiles. PCA may be used to reduce dimensionality and visualize the primary components of variation in the data [4] [5].

- 4. Cluster Validation and Interpretation: The quality and stability of the resulting clusters are assessed using internal validation metrics such as the Silhouette Score (measuring cohesion and separation) and the Davies–Bouldin Index (lower values indicate better separation). The adjusted Rand Index can be used to assess stability across time intervals. The final, crucial step is for domain experts to interpret the clusters to assign meaning, such as identifying "high-pollution, high-humidity" microenvironments [5].

Implementing machine learning for environmental monitoring requires a combination of computational tools, analytical algorithms, and domain-specific data. The following table catalogs key resources referenced in recent studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Environmental Monitoring

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Supervised ML Algorithm | High-performance gradient boosting for regression and classification tasks. | Predicting effluent quality index (EQI) in wastewater treatment plants [6] [7]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVR) | Supervised ML Algorithm | Regression for non-linear, high-dimensional data using kernel functions. | Fitting complex relationships in water quality parameters [7]. |

| Random Forest | Supervised ML Algorithm | Ensemble learning for classification and regression; provides feature importance. | Predicting dominant microbial contamination sources in a watershed [3]. |

| K-means Clustering | Unsupervised ML Algorithm | Partitioning unlabeled data into 'k' distinct clusters based on similarity. | Identifying homogeneous indoor air pollution microenvironments [4] [5]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Unsupervised ML Technique | Dimensionality reduction to simplify data and reveal key patterns. | Preprocessing for model training; analyzing multivariate environmental factor correlations [4] [5]. |

| DBScan | Unsupervised ML Algorithm | Density-based clustering to discover clusters of arbitrary shape and handle noise. | Robust clustering of environmental data without pre-specifying the number of groups [4] [5]. |

| Libelium Smart Environment Pro | Sensor Hardware | Integrated sensor platform for measuring multiple air pollutants (CO, O₃) and comfort parameters. | Generating datasets for indoor air quality (IAQ) analysis and clustering studies [5]. |

| Plantower PMS7003 Sensor | Sensor Hardware | Laser scattering sensor to measure particulate matter (PM1, PM2.5, PM10) concentrations. | Quantifying particulate pollution levels for ML model input [5]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Computational Method | Efficiently navigates the hyperparameter space to optimize model performance. | Tuning parameters for ML models classifying high-voltage insulator contamination [8]. |

| GridSearchCV | Computational Method | Exhaustive search over a specified parameter grid with cross-validation. | Hyperparameter tuning for supervised learning models like SVR and XGBoost [7]. |

The machine learning landscape in environmental monitoring is diverse, with no single approach being universally superior. The choice between supervised and unsupervised learning is fundamentally guided by the research question and data context.

Supervised learning is the methodology of choice for predictive tasks where historical data with known outcomes is available. Its strength lies in delivering high-accuracy, quantitative predictions for well-defined variables, making it ideal for operational forecasting and classification, such as predicting effluent quality or identifying known contamination types.

Unsupervised learning serves as a powerful tool for exploratory analysis, hypothesis generation, and pattern discovery in complex, unlabeled datasets. It is indispensable for uncovering hidden structures, segmenting environments based on multivariate profiles, and identifying novel correlations between environmental factors.

For researchers and scientists, the most effective strategies often involve a synergistic use of both paradigms. Unsupervised methods can first reveal natural groupings in data, which can then be used to inform and label datasets for subsequent supervised modeling. As the field evolves, this flexible, tool-based understanding of machine learning will be crucial for leveraging data to address pressing environmental challenges.

In environmental forensics, accurately attributing pollutants to their sources is critical for effective remediation and policy-making. Supervised learning (SL) provides a powerful framework for this task by leveraging labeled datasets where the contamination sources are pre-identified, enabling models to learn complex patterns for predictive accuracy [9] [10]. This approach stands in contrast to unsupervised methods that identify patterns without pre-existing labels. The fundamental strength of supervised learning lies in its ability to learn from known outcomes—where sources are definitively identified—to build predictive models that can classify unknown samples with high accuracy [11]. This capability makes it particularly valuable for contaminant source tracking, where identifying the origin of pollutants directly informs containment and cleanup strategies.

The integration of machine learning with analytical techniques like non-target analysis (NTA) has revolutionized source identification capabilities [11]. While unsupervised learning can reveal hidden patterns in complex environmental data, supervised learning adds a critical layer of predictive precision by training on verified source-receptor relationships. This article provides a comprehensive comparison between supervised and unsupervised learning approaches for contaminant source tracking, presenting experimental data, methodological frameworks, and practical resources to guide researchers in selecting appropriate techniques for their specific applications.

Theoretical Foundations: Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning in Environmental Science

Core Paradigms and Differences

Supervised learning operates on labeled datasets where each input sample is associated with a known output or class label [10]. In contaminant tracking, this translates to training models on chemical fingerprints where the pollution sources are definitively identified. The model learns the relationship between chemical features and their sources, enabling it to predict sources for new, unlabeled samples. Common supervised algorithms include Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and Logistic Regression, which have demonstrated balanced accuracy ranging from 85.5% to 99.5% in classifying per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) to their sources [11].

In contrast, unsupervised learning identifies inherent patterns and structures in data without pre-existing labels [12] [13]. Techniques like K-means clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) group samples based on similarity metrics, allowing researchers to discover previously unknown source categories or spatial patterns without prior knowledge of source identities. While this approach is valuable for exploratory analysis, it lacks the predictive validation inherent in supervised methods.

Comparative Strengths and Limitations

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each approach:

Table 1: Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning for Contaminant Source Tracking

| Aspect | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Requires labeled training data with known sources [9] | Works with unlabeled data; discovers patterns without prior knowledge [13] |

| Primary Applications | Source classification, prediction, and attribution [11] | Pattern discovery, cluster identification, and exploratory analysis [13] |

| Key Advantages | High predictive accuracy for known source types; validated performance metrics [11] | No need for costly labeling; identifies novel sources or unexpected patterns [13] |

| Major Limitations | Dependent on quality and completeness of labels; cannot identify unknown sources [9] | Lack of ground truth validation; results may be difficult to interpret causally [11] |

| Interpretability | Feature importance metrics provide insight into diagnostic chemicals [11] | Cluster interpretation requires domain expertise and additional validation [11] |

| Model Validation | Standard metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score [14] [15] | Internal metrics: silhouette score, inertia; requires external validation [11] |

Experimental Comparison: Performance Evaluation in Source Tracking

Case Study: Heavy Metal Source Attribution in Urban Rivers

A 2025 study on heavy metal pollution in the Jinghe River provides compelling experimental data comparing supervised and unsupervised performance [16]. Researchers integrated self-organizing maps (SOM - unsupervised) with positive matrix factorization (PMF) and correlation analysis to identify five contamination sources: industrial and traffic activities (33.33%), agriculture (27.21%), metal manufacturing (15.49%), natural sources (12.95%), and smelting/electroplating (11.02%) [16]. When supervised classifiers were applied to the same dataset, they demonstrated superior performance in quantifying source contributions with lower uncertainty ranges.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes performance metrics from multiple contaminant source tracking studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Algorithms in Source Tracking Studies

| Algorithm Type | Specific Method | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised | Random Forest (RF) | PFAS source attribution | Balanced accuracy: 85.5-99.5% | [11] |

| Supervised | Support Vector Classifier (SVC) | PFAS source attribution | Balanced accuracy: 85.5-99.5% | [11] |

| Supervised | Logistic Regression (LR) | PFAS source attribution | Balanced accuracy: 85.5-99.5% | [11] |

| Unsupervised | K-means Clustering | Climate discourse analysis | Identified 10 thematic clusters in 1.7M posts | [13] |

| Unsupervised | Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) | Heavy metal source identification | Identified 5 source categories with contribution percentages | [16] |

| Supervised | Random Forest Classifier | Social media theme classification | High accuracy in identifying climate discussion themes | [13] |

Evaluation Metrics for Supervised Models

The performance of supervised learning models is quantified using specific evaluation metrics, each providing distinct insights:

- Accuracy: Measures overall correctness, but can be misleading with imbalanced datasets [14] [15]

- Precision: Indicates how often positive predictions are correct; crucial when false positives are costly [15]

- Recall: Measures the ability to identify all relevant cases; important when false negatives pose significant risks [14]

- F1-score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall; provides balanced metric for imbalanced datasets [14]

In environmental applications where target sources may be rare but high-impact (e.g., toxic spill identification), recall often takes priority over accuracy to ensure minimal missed detections [15].

Methodological Framework: Implementing Supervised Learning for Source Attribution

Integrated Workflow for ML-Assisted Source Tracking

The following workflow illustrates the comprehensive process for implementing machine learning in contaminant source tracking, highlighting where supervised and unsupervised techniques integrate:

Diagram 1: Integrated ML Workflow for Source Tracking

Data Processing and Model Selection Protocol

Successful implementation requires meticulous data processing and appropriate algorithm selection:

Data Preprocessing Protocol:

- Data Alignment: Retention time correction and mass-to-charge ratio recalibration across analytical batches [11]

- Noise Filtering: Remove low-quality signals and artifacts using statistical thresholds [11]

- Missing Value Imputation: Apply k-nearest neighbors or similar methods to handle missing observations [11]

- Normalization: Use total ion current (TIC) or quantile normalization to mitigate batch effects [11]

Supervised Model Selection Strategy:

- For small datasets (<1,000 samples): Start with Logistic Regression or Linear SVM as baseline models [17]

- For moderate datasets (1,000-10,000 samples): Implement Random Forest or Gradient Boosting for robust performance [11]

- For large datasets (>10,000 samples): Explore deep learning architectures or ensemble methods [12]

- For highly imbalanced data: Apply Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) or cost-sensitive learning [17]

Validation Framework for Supervised Models

Robust validation is essential for reliable source attribution:

- Analytical Validation: Verify compound identities using certified reference materials or spectral library matches [11]

- Model Performance Validation: Assess generalizability using independent external datasets with k-fold cross-validation [11]

- Environmental Plausibility Checks: Correlate model predictions with geospatial data and known source-specific chemical markers [11]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit for ML-Based Source Tracking

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Based Source Attribution Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRMS Platforms | Q-TOF, Orbitrap Systems | Generate high-resolution spectral data for compound identification [11] | Non-target analysis for unknown contaminant discovery |

| Chromatography Systems | LC-HRMS, GC-HRMS | Separate complex mixtures before mass spectrometric analysis [11] | Environmental sample analysis with complex matrices |

| Data Processing Platforms | XCMS, Progenesis QI | Peak detection, alignment, and componentization of raw HRMS data [11] | Preprocessing of spectral data before ML analysis |

| ML Libraries | Scikit-learn, XGBoost | Provide implementations of classification and regression algorithms [10] | Building supervised models for source attribution |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Enable complex neural network architectures for large datasets [17] | Handling high-dimensional spectral data |

| Data Labeling Platforms | Scale AI, Labelbox | Facilitate annotation of training data with source identifiers [9] [18] | Creating labeled datasets for supervised learning |

| Visualization Tools | Matplotlib, Plotly | Generate plots for model interpretation and result communication [10] | Exploratory data analysis and model output presentation |

Supervised learning offers distinct advantages for contaminant source tracking through its predictive accuracy and validated performance when applied to well-characterized contamination scenarios with adequate labeled data [11]. The experimental data presented demonstrates that supervised algorithms can achieve balanced accuracy exceeding 85% in complex source attribution tasks, providing actionable intelligence for environmental management [11] [16].

However, the effectiveness of supervised learning is contingent on data quality, label accuracy, and domain-informed feature selection [9]. In practice, a hybrid approach that leverages unsupervised methods for exploratory analysis and pattern discovery, followed by supervised learning for targeted prediction and validation, often yields the most comprehensive insights [11]. This sequential methodology allows researchers to discover novel patterns while maintaining predictive accuracy for known sources.

For researchers implementing these techniques, investment in robust validation frameworks and high-quality labeled data remains paramount [9] [11]. As analytical techniques advance and reference databases expand, supervised learning will continue to enhance our capability to precisely attribute contaminants to their sources, ultimately supporting more effective environmental protection and regulatory decision-making.

In the field of environmental science, identifying the sources and profiles of contaminants is a fundamental challenge. While supervised learning models are powerful for predicting known classes of contaminants, they require pre-existing, labeled data for training. Unsupervised learning addresses a critical gap by analyzing unlabeled data to discover hidden structures, identify novel contaminant profiles, and characterize unknown sources without prior knowledge of their existence or nature [19]. This capability is particularly vital for detecting emerging pollutants or complex mixtures whose signatures are not yet defined in existing databases. This guide objectively compares the performance, protocols, and applications of unsupervised learning against supervised and semi-supervised approaches in contaminant source tracking research, providing researchers with a clear framework for method selection.

Core Concepts and Comparative Frameworks

Defining the Machine Learning Approaches

- Unsupervised Learning: This approach uses machine learning algorithms to analyze and cluster unlabeled datasets. The algorithms discover hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in the input data without human intervention, making them ideal for exploratory data analysis [19]. Key techniques include clustering (e.g., K-means), dimensionality reduction (e.g., Principal Component Analysis), and association [3].

- Supervised Learning: In contrast, supervised learning is defined by its use of labeled datasets to train algorithms to classify data or predict outcomes accurately. Using labeled inputs and outputs, the model can measure its accuracy and learn over time [19]. It encompasses classification (e.g., Random Forest) and regression algorithms.

- Semi-Supervised Learning: This is a hybrid approach that uses a training dataset containing both labeled and unlabeled data. It is particularly useful when extracting relevant features from data is difficult, and when dealing with high volumes of data, such as in medical image analysis [19].

Comparative Performance in Source Tracking

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different machine learning approaches as applied in environmental contaminant studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches in Contaminant Studies

| Feature | Unsupervised Learning | Supervised Learning | Semi-Supervised Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Discover hidden patterns, cluster data by similarity [19] | Predict outcomes for new data based on known labels [19] | Leverage few labels to improve pattern discovery [20] |

| Data Requirements | Unlabeled data [19] | Accurately labeled datasets [21] | Mix of labeled and unlabeled data [19] |

| Typical Applications in Contaminant Research | Blind source separation, identifying unknown pollutant sources [22], clustering novel chemical profiles [11] | Classifying known contaminant types, predicting concentration levels [3] | Pharmaceutical drug rating using reviews [20], medical imaging [19] |

| Key Strengths | No need for pre-defined labels, identifies novel patterns | High accuracy for well-defined problems, trustworthy results [19] | Improves accuracy with limited labeled data [19] |

| Limitations & Complexities | Outputs require validation; can be computationally complex with high-dimensional data [19] | Time-consuming data labeling; requires expert input [19] | Still requires some labeled data; model tuning can be complex |

Quantitative benchmarks illustrate these differences. In a study predicting microbial water contamination sources, supervised models like XGBoost achieved 88% accuracy in classifying human vs. non-human sources, while Random Forest followed closely at 84% accuracy [3]. Conversely, an extensive benchmark of unsupervised classification approaches for univariate data highlighted that performance is highly dependent on the chosen algorithm and feature space construction, with significant accuracy variations observed across methods [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Workflow for Unsupervised Contaminant Profiling

The application of unsupervised learning, particularly in non-target analysis (NTA) for contaminant identification, follows a systematic workflow [11].

Diagram 1: ML-Assisted Non-Target Analysis Workflow

- Stage 1: Sample Treatment and Extraction: Environmental samples (water, soil) are collected and prepared. Techniques like solid phase extraction (SPE) are commonly employed to balance selectivity and sensitivity, removing interfering components while preserving a wide range of compounds [11].

- Stage 2: Data Generation and Acquisition: Samples are analyzed using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS), often coupled with liquid or gas chromatography (LC/GC). This generates complex datasets containing information on thousands of chemical features [11].

- Stage 3: ML-Oriented Data Processing: The raw HRMS data is preprocessed. This includes peak detection, alignment, and componentization to group related spectral features into molecular entities. The output is a structured feature-intensity matrix, which serves as the foundation for machine learning analysis [11].

- Stage 4: Unsupervised Clustering & Dimensionality Reduction: This is the core unsupervised learning phase. Clustering methods like k-means or Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) group samples by chemical similarity without predefined labels [11]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-SNE simplify the high-dimensional data, making it easier to visualize and interpret underlying patterns and groupings [11] [23].

- Stage 5: Result Validation & Interpretation: A multi-tiered validation strategy is crucial. This involves using reference materials to confirm compound identities, assessing model generalizability on external datasets, and checking environmental plausibility by correlating model predictions with contextual data like known pollution sources [11].

Protocol: Blind Source Separation with NMFk

A specific unsupervised protocol for contaminant source identification is NMFk, which combines Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) with a custom semi-supervised clustering algorithm [22].

- Objective: To identify (a) the unknown number of groundwater types (contaminant sources) and (b) their original geochemical concentrations from measured mixture samples without prior information [22].

- Methodology:

- Data Matrix Formulation: The geochemical observation data is organized into a matrix V, where rows represent different sampling points and columns represent different geochemical constituents.

- Blind Source Separation (BSS): The core assumption is that the observation matrix V is a linear mixture of k unknown original source signals (H), blended by an unknown mixing matrix (W), such that V ≈ W x H [22].

- NMFk Algorithm: The method performs multiple NMF modellings for a range of potential source numbers (k). For each k, it runs numerous NMF simulations to factorize V into W and H. A custom clustering analysis is then applied to the ensemble of solutions to identify the optimal number of sources k that yields the most robust and physically meaningful separation [22].

- Application: This protocol has been successfully tested on both synthetic and real-world site data, demonstrating its capability to unmix geochemical signatures and identify contaminant sources, including their concentrations, from observation samples alone [22].

Performance Data and Benchmarking

Quantitative Benchmarking of Unsupervised Algorithms

The performance of unsupervised learning is not universal; it depends heavily on the chosen algorithms and feature space construction. A comprehensive benchmark of 28 feature space methods and 16 clustering algorithms on 900 simulated datasets revealed significant performance differences [23].

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Select Unsupervised Learning Combinations on Simulated Data

| Feature Space Construction Method | Clustering Algorithm | Performance (Fowlkes-Mallows Index) | Key Application Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE (cosine) | Fuzzy C-Means | High (>0.8) [23] | Effective for capturing complex, non-linear data structures. |

| 28x28 Image + t-SNE (cosine) | k-Means | High (>0.8) [23] | Useful for data that can be intuitively represented as images. |

| UMAP (Euclidean) | k-Means | High (>0.8) [23] | A robust modern method for general-purpose dimensionality reduction. |

| Raw Data | k-Means | Lower performance [23] | Highlights the curse of dimensionality; preprocessing is critical. |

This benchmark underscores that careful selection of the feature space construction method and clustering algorithm for a specific measurement type can greatly improve classification accuracies in unsupervised learning tasks [23].

Supervised vs. Unsupervised Model Performance

Direct comparisons in environmental studies show how problem definition influences model choice.

Table 3: Model Performance in Environmental Source Tracking Case Studies

| Study Focus | Machine Learning Type | Algorithm(s) Used | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting Microbial Water Contamination Sources [3] | Supervised | XGBoost, Random Forest, SVM, KNN, Naïve Bayes, Simple NN | XGBoost accuracy: 88% (AUC=0.88); Random Forest accuracy: 84% (AUC=0.84) [3] |

| Identifying Characteristic Shapes in Nanoelectronic Data [23] | Unsupervised | k-Means, Fuzzy C-Means, etc. with various feature spaces | Performance highly variable (FM Index from <0.2 to >0.8), dependent on algorithm/feature space pairing [23] |

| Decomposing Geochemical Mixtures in Groundwater [22] | Unsupervised (Blind Source Separation) | NMFk | Successfully identified the number of contaminant sources and their concentrations from synthetic and field mixtures [22] |

The high accuracy of supervised models like XGBoost is achievable when the target classes (e.g., human vs. non-human source) are well-defined [3]. Unsupervised methods like NMFk are indispensable when the number and nature of the sources themselves are unknown, even if their output is a qualitative source profile rather than a quantitative accuracy score [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental protocols described rely on a suite of essential reagents, software, and analytical tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Contaminant Discovery

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Relevance to Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (e.g., Oasis HLB, Strata WAX/WCX) | Sample preparation; enrichment and purification of a wide range of organic contaminants from water samples. | Critical in Stage 1 for removing matrix interference and concentrating analytes for HRMS analysis [11]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap) | Data generation; enables detection and measurement of thousands of unknown chemical features with high mass accuracy. | The core instrument in Stage 2 for non-target analysis and generating the feature-intensity matrix [11]. |

| Chromatography Systems (e.g., LC, GC) | Compound separation; resolves complex mixtures in time, reducing spectral overlap and improving compound identification. | Coupled with HRMS in Stage 2 to separate compounds before mass spectrometric detection [11]. |

| Programming Frameworks (e.g., Python, R, Julia) | Data processing and analysis; provides environments for implementing ML algorithms, statistical tests, and data visualization. | Essential for Stages 3 and 4, encompassing data preprocessing, clustering, and dimensionality reduction [22] [23]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validation; provides known chemical standards to confirm compound identities and validate model predictions. | A key component of Stage 5 (validation) to ensure analytical confidence and chemical accuracy [11]. |

Unsupervised learning is a powerful approach for discovering hidden structures and novel contaminant profiles, filling a critical niche where labeled data is absent or the problem is not fully defined. While supervised learning excels in predictive accuracy for well-characterized contaminants, unsupervised methods like clustering and blind source separation are indispensable for initial exploration, hypothesis generation, and identifying entirely unknown pollution sources. The choice between these paradigms should be guided by the research objective: use supervised learning for predicting known categories with high accuracy, and unsupervised learning for exploring unlabeled data to discover new patterns and sources. As benchmarks show, the effectiveness of unsupervised learning depends significantly on selecting appropriate algorithms and feature construction methods tailored to the specific data type, a decision that requires both computational knowledge and environmental science expertise.

In contaminant source tracking, identifying the origin of pollutants is fundamental for effective environmental management and remediation. Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to decipher complex environmental datasets, with supervised and unsupervised learning representing two foundational paradigms. The core distinction lies in the use of labeled data; supervised learning requires a known outcome to train models, whereas unsupervised learning identifies inherent structures without predefined labels [19] [24]. This distinction critically influences their application, performance, and interpretation in research settings. For environmental scientists and drug development professionals, the choice between these approaches is not merely technical but strategic, impacting the reliability and actionability of the results for decision-making.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental decision-making workflow for selecting between these approaches in a contaminant source tracking study:

Supervised Learning: Defined Objectives and Predictive Accuracy

Core Methodology and Workflow

Supervised learning is a machine learning approach defined by its use of labeled datasets to train algorithms for classifying data or predicting outcomes [19]. In the context of contaminant source tracking, this means that the model is trained on environmental samples where the contamination source is already known. The algorithm learns the relationship between input features (e.g., chemical signatures, land use data, weather patterns) and the known output labels (specific contaminant sources) [3]. This learning process enables the model to make accurate predictions on new, unlabeled data. The methodology is particularly valuable when researchers have a well-defined problem and require high-confidence predictions for known contaminant sources.

The strength of supervised learning lies in its iterative training process, where the model makes predictions on the training data and is adjusted to minimize the difference between its predictions and the known correct answers [19]. Common algorithms used in environmental research include Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and XGBoost, all of which have demonstrated success in classifying contamination sources [3] [11]. For example, in pharmaceutical research, supervised learning algorithms like Naive Bayesian (NB) classifiers have been employed to predict ligand-target interactions and classify compounds as active or inactive against specific biological targets [25].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Implementing supervised learning for contaminant source tracking follows a structured protocol centered on model training and validation. A typical experimental workflow, as applied in microbial source tracking, involves these critical stages:

Training Data Collection: Assemble a comprehensive dataset of environmental samples with known contaminant sources. For example, in a study predicting microbial sources, 102 water samples were collected from 46 sites, with sources classified into six major categories (human, bird, dog, horse, pig, ruminant) using SourceTracker [3].

Feature Selection: Identify and select relevant predictive variables. Research has shown that factors such as land cover, weather patterns (precipitation, temperature), and hydrologic variables significantly impact contaminant sources and should be included as features [3]. In pharmaceutical applications, features might include molecular descriptors or structural features.

Model Training and Validation: Split the labeled data into training and testing sets. Train multiple algorithms (e.g., RF, SVM, XGBoost) on the training set and evaluate their performance on the held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC), and balanced accuracy [3]. For instance, one study achieved classification balanced accuracy ranging from 85.5% to 99.5% for different contaminant sources using classifiers like SVC, LR, and RF [11].

External Validation: Test the final model on independent external datasets to ensure generalizability and robustness, a critical step for real-world application [26] [11].

Unsupervised Learning: Exploratory Analysis and Pattern Discovery

Core Methodology and Workflow

Unsupervised learning employs machine learning algorithms to analyze and cluster unlabeled data sets, discovering hidden patterns without human intervention [19] [27]. In contaminant source tracking, this approach is invaluable when the sources are unknown or not well-defined, allowing researchers to explore complex environmental data without preconceived categories. The algorithm's objective is to identify inherent structures, similarities, or groupings within the data that might represent distinct contamination signatures or sources. This capability makes unsupervised learning particularly suited for initial exploratory studies where the goal is hypothesis generation rather than hypothesis testing.

The primary techniques in unsupervised learning include clustering (grouping similar data points), association (finding relationships between variables), and dimensionality reduction (simplifying data while preserving its essential structure) [19]. Common algorithms used in environmental research include K-means clustering, Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [27] [11]. These methods help researchers identify previously unknown patterns, anomalies, or subgroups in unlabeled contaminant data, providing foundational insights that might inform subsequent supervised learning approaches or direct field validation efforts.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Implementing unsupervised learning for contaminant source tracking follows a more exploratory protocol focused on data structure discovery:

Data Preprocessing: Process raw environmental data to ensure quality and compatibility. This includes noise filtering, missing value imputation (e.g., using k-nearest neighbors), and normalization (e.g., Total Ion Current (TIC) normalization for mass spectrometry data) to mitigate batch effects and technical variations [11].

Exploratory Data Analysis: Apply unsupervised techniques to identify significant patterns and groupings. This often begins with dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to visualize high-dimensional data in two or three dimensions, revealing potential clusters or outliers [11].

Clustering Analysis: Implement clustering algorithms to group samples with similar chemical profiles. For example, HCA and K-means clustering can group environmental samples based on chemical similarity, potentially corresponding to different contamination sources or pathways [11].

Pattern Interpretation: Analyze the resulting clusters and patterns to extract environmentally meaningful insights. This requires domain expertise to correlate statistical groupings with potential contaminant sources, often supplemented with chemical fingerprinting or marker compound identification [11].

Validation: Unlike supervised learning, validation of unsupervised results is more challenging and often relies on environmental plausibility checks, correlating model outputs with contextual data such as geospatial proximity to emission sources or known source-specific chemical markers [11].

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Performance Metrics

Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

The table below summarizes the core differences between supervised and unsupervised learning in the context of contaminant source tracking research:

| Parameter | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Labeled data (known sources) [19] [24] | Unlabeled data (unknown sources) [19] [24] |

| Primary Goal | Predict/classify known contaminant sources [3] | Discover hidden patterns, groupings, or new source types [27] [11] |

| Common Algorithms | Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM, Naive Bayes [3] [25] | K-means, HCA, PCA, DBSCAN [27] [11] |

| Accuracy & Performance | High accuracy for known classes; e.g., XGBoost achieved 88% accuracy in microbial source prediction [3] | Results are more qualitative; evaluation focuses on cluster robustness and environmental plausibility [11] |

| Data Requirements | Requires substantial, high-quality labeled data, which is costly and time-consuming to produce [19] [28] | Works with abundant, unlabeled data, but requires expert validation for interpretation [27] [24] |

| Interpretability | Clear, direct interpretation based on known labels and classes [24] | Interpretation can be challenging and subjective, requiring domain expertise [24] |

| Best-Suited Research Phase | Confirmation and prediction phase for known contaminants | Exploratory phase for novel or poorly understood contamination |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below presents experimental performance data from environmental studies that applied these machine learning approaches to contaminant source tracking:

| Study Focus | ML Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Source Tracking [3] | XGBoost (Supervised) | 88% accuracy, AUC = 0.88 | Most effective algorithm for predicting human vs. non-human sources; precipitation and temperature were most important predictors. |

| Microbial Source Tracking [3] | Random Forest (Supervised) | 84% average AUC | Second-best performer; provided variable importance indices for feature interpretation. |

| PFAS Source Identification [11] | RF, SVC, LR (Supervised) | 85.5% to 99.5% balanced accuracy | Successfully classified sources of 222 PFASs from 92 samples using chemical features. |

| General Limitations [19] | Unsupervised Clustering | N/A (Qualitative output) | Higher risk of inaccurate results without human intervention to validate output variables. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents, software, and analytical tools essential for implementing machine learning in contaminant source tracking research:

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| HRMS Platforms | Q-TOF, Orbitrap Systems [11] | Generate high-resolution chemical fingerprint data for non-target analysis of contaminants. |

| Chromatography Systems | LC/GC coupled with HRMS [11] | Separate complex environmental samples before mass spectrometric analysis. |

| Extraction & Purification | SPE, QuEChERS, PLE [11] | Isolate and concentrate contaminants from water, soil, or biological matrices. |

| Statistical Software | R, Python [19] | Provide programming environments for data preprocessing, model development, and validation. |

| ML Libraries | Scikit-learn, XGBoost [3] | Offer pre-implemented algorithms for classification, regression, and clustering tasks. |

| Validation Materials | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [11] | Verify compound identities and ensure analytical confidence in model inputs. |

Selecting between supervised and unsupervised learning is not a matter of superior versus inferior but rather strategic application based on the research question, data availability, and project goals. The following diagram synthesizes the decision criteria into a unified framework for contaminant source tracking research:

Use supervised learning when your research aims to predict or classify known contaminant sources, you have access to reliable labeled data for training, and you require high-accuracy, actionable results for decision-making. This approach is ideal for operational monitoring and regulatory enforcement where precision and reliability are paramount.

Use unsupervised learning when exploring novel contamination scenarios with unknown sources, when labeled data is unavailable or too costly to obtain, and when the research goal is hypothesis generation and pattern discovery. This approach is particularly valuable in early investigative stages of research and for detecting emerging contaminants or unexpected source relationships.

For the most comprehensive understanding, researchers should consider a sequential approach: beginning with unsupervised learning to explore data and identify potential patterns, then applying supervised learning to validate these patterns and build predictive models for future contamination events. This integrated methodology leverages the strengths of both paradigms, transforming raw environmental data into defensible, actionable scientific insights.

The Critical Role of High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Non-Target Analysis (NTA) in Data Generation

Non-Target Analysis (NTA) using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) has emerged as a powerful approach for detecting unknown and unexpected compounds in complex environmental samples. Unlike traditional targeted methods that focus on predefined analytes, NTA provides a comprehensive snapshot of the chemical composition in a sample, enabling the discovery of emerging contaminants, their transformation products, and previously unrecognized pollutants [29] [30]. This capability is particularly valuable for contaminant source tracking, where understanding complex chemical signatures is essential for identifying pollution origins. Modern HRMS platforms, including quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) and Orbitrap systems, generate rich datasets containing information on thousands of chemical features with high mass accuracy and resolution [11]. When coupled with advanced data processing techniques, including machine learning, HRMS-based NTA transforms environmental monitoring by providing the critical data foundation needed for unsupervised and supervised learning approaches in contaminant source identification.

Performance Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Approaches

The selection of mass spectrometry approaches involves trade-offs between quantification performance and screening capability. Targeted methods using triple quadrupole (QqQ) instruments remain the gold standard for sensitive and precise quantification of known compounds, while HRMS-based approaches excel at broad-spectrum screening and retrospective analysis.

Table 1: Performance comparison of targeted MS/MS, high-resolution full scan (HRFS), and data-independent acquisition (DIA) for pharmaceutical analysis in water matrices

| Performance Metric | Targeted MS/MS (QqQ) | HRFS (Orbitrap) | DIA (Orbitrap) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median LOQ (ng/L) | 0.54 | Higher than MS/MS | Higher than MS/MS |

| Trueness (Median) | 101% | 63% of compounds with acceptable trueness | 81% of compounds with acceptable trueness |

| Matrix Effects | Minimal | Compound- and matrix-specific | Compound- and matrix-specific |

| Primary Strength | Sensitive quantification for routine monitoring | Retrospective analysis, broad screening | Comprehensive fragmentation data |

| Data Acquisition | Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) | Full-scan spectra (m/z 100-1000) | All precursor ions fragmented simultaneously |

| Resolving Power | Unit resolution | 70,000 FWHM | 17,500 FWHM (DIA mode) |

Targeted tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) demonstrates superior performance for routine regulatory monitoring, achieving the lowest limits of quantification (median 0.54 ng/L) and highest trueness (median 101%) across various environmental water matrices, including wastewater and surface water [31] [32]. This approach is ideal for monitoring predefined contaminants where high sensitivity and precise quantification are required. In contrast, high-resolution full scan (HRFS) and data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods, while showing higher LOQs and greater variability, provide invaluable broader screening capabilities [32]. The key advantage of HRMS methods lies in their ability to perform retrospective data analysis - stored HRMS data can be reinterrogated years later as new environmental concerns emerge, creating a "digital archive" of environmental samples [30].

Experimental Protocols for HRMS-Based NTA

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Comprehensive sample preparation is crucial for successful NTA. Solid phase extraction (SPE) is widely employed, with multi-sorbent strategies (e.g., combining Oasis HLB with ISOLUTE ENV+, Strata WAX, and WCX) providing broader compound coverage than single-sorbent approaches [11]. The objective is to balance selective removal of interfering matrix components with preservation of as many analyte compounds as possible at adequate sensitivity levels. Green extraction techniques like QuEChERS, microwave-assisted extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction can improve efficiency by reducing solvent usage and processing time, particularly beneficial for large-scale environmental sampling campaigns [11].

Instrumental Analysis and Data Acquisition

Liquid chromatography coupled to HRMS (LC-HRMS) represents the core analytical platform for NTA. Typical parameters for pharmaceutical analysis in water matrices include:

- Chromatography: Reversed-phase separation using C18, C8, or phenyl-hexyl columns with acidified water and acetonitrile as mobile phases [32] [33]

- Ionization: Heated electrospray ionization (H-ESI) in positive or negative mode with spray voltages of 3000-3500V

- Mass Analysis: Full-scan data acquisition with resolving power of 70,000 FWHM or higher across m/z range 100-1000 [32]

- Data Quality: Incorporation of batch-specific quality control samples and procedural blanks to ensure data integrity [11]

Post-acquisition processing involves centroiding, extracted ion chromatogram analysis, peak detection, alignment, and componentization to group related spectral features (adducts, isotopes) into molecular entities [11]. The final output is a structured feature-intensity matrix where rows represent samples and columns correspond to aligned chemical features, serving as the foundation for subsequent statistical and machine learning analysis.

Machine Learning Integration for Contaminant Source Tracking

The integration of machine learning with HRMS-based NTA has redefined potential for contaminant source identification. ML algorithms excel at identifying latent patterns within high-dimensional data, making them particularly well-suited for disentangling complex source signatures that traditional statistical methods struggle with [11].

Diagram 1: ML-assisted NTA workflow for source tracking

ML-Oriented Data Processing and Analysis

The transition from raw HRMS data to interpretable patterns involves sequential computational steps. Initial preprocessing addresses data quality through noise filtering, missing value imputation (e.g., k-nearest neighbors), and normalization (e.g., total ion current normalization) to mitigate batch effects [11]. Exploratory analysis then identifies significant features via univariate statistics (t-tests, ANOVA) and prioritizes compounds with large fold changes. Dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) simplify high-dimensional data, while clustering methods (hierarchical cluster analysis, k-means) group samples by chemical similarity [11].

Supervised ML models, including Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Classifier (SVC), are subsequently trained on labeled datasets to classify contamination sources. For example, ML classifiers have been successfully implemented to screen 222 targeted and suspect per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as features distributed in 92 samples, achieving classification balanced accuracy ranging from 85.5% to 99.5% across different sources [11]. Feature selection algorithms (e.g., recursive feature elimination) refine input variables, optimizing model accuracy and interpretability.

Retention Time Prediction for Enhanced Compound Identification

Retention time (RT) serves as a critical orthogonal parameter for compound identification in NTA. ML-based RT prediction has emerged as a valuable tool for improving identification confidence, with two primary approaches:

Table 2: Comparison of retention time prediction approaches for compound identification

| Aspect | Projection Methods | Prediction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Projects RT from reference database to target system | Predicts RT from molecular structure using QSRR |

| Data Requirement | Set of chemicals measured on both source and target systems | Large dataset of known RT-structure relationships |

| Key Factors | Similarity of chromatographic systems (column, mobile phase) | Chemical space coverage in training set |

| Performance | Depends on CS~source~ and CS~NTS~ similarity | Depends on CS~training~ and CS~NTS~ similarity |

| Best Application | When similar chromatographic systems are available | When comprehensive training data exists for target method |

Projection methods leverage public databases of retention times measured on similar chromatographic systems and project these to the NTS system based on a small set of commonly analyzed chemicals [33]. Prediction methods utilize machine learning models trained on publicly available retention time data to predict retention behavior directly from molecular structure [33] [34]. The accuracy of both approaches is directly linked to the similarity of the chromatographic systems, with the pH of the mobile phase and the column chemistry being most impactful [33]. For cases where the source and target chromatographic systems differ substantially but the training and target systems are similar, prediction models can perform on par with projection models.

Prioritization Strategies for NTA Workflows

Effective prioritization of features detected in NTA is essential for efficient resource allocation. Seven complementary strategies have been identified for progressive filtering of complex HRMS datasets [35]:

Diagram 2: Seven prioritization strategies for NTA

Target and Suspect Screening (P1): Utilizes predefined databases of known or suspected contaminants to narrow candidates early in the workflow [35].

Data Quality Filtering (P2): Removes artifacts and unreliable signals based on occurrence in blanks, replicate consistency, and peak shape [35].

Chemistry-Driven Prioritization (P3): Focuses on compound-specific properties, such as mass defect filtering for halogenated compounds like PFAS [35].

Process-Driven Prioritization (P4): Leverages spatial, temporal, or technical processes (e.g., upstream vs. downstream sampling) to highlight relevant features [35].

Effect-Directed Prioritization (P5): Integrates biological response data with chemical analysis to target bioactive contaminants [35].

Prediction-Based Prioritization (P6): Combines predicted concentrations and toxicities to calculate risk quotients and prioritize high-risk substances [35].

Pixel- and Tile-Based Approaches (P7): For complex datasets (especially 2D chromatography), localizes regions of high variance before peak detection [35].

When combined, these strategies enable stepwise reduction from thousands of features to a focused shortlist of high-priority compounds, significantly improving the efficiency of NTA workflows.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for HRMS-based NTA

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-sorbent SPE | Broad-spectrum extraction of diverse compounds | Oasis HLB with ISOLUTE ENV+/Strata WAX/WCX [11] |

| HRMS Instrumentation | High-resolution accurate mass measurement | Q-TOF, Orbitrap systems [11] |

| Chromatography Columns | Compound separation | C18, C8, phenyl-hexyl columns for reversed-phase [32] |

| Retention Time Calibrants | System performance monitoring and RT alignment | 41 calibrant chemicals for interlaboratory comparison [33] |

| QC Reference Materials | Data quality assurance | Batch-specific quality control samples [11] |

| MS Calibration Solution | Mass accuracy calibration | Daily instrument calibration for precise mass measurement [32] |

| Database Resources | Compound identification | NORMAN Suspect List Exchange, PubChemLite, CompTox Dashboard [35] |

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry coupled with Non-Target Analysis represents a transformative approach for comprehensive chemical characterization of environmental samples. While targeted MS methods maintain advantages for sensitive quantification of known compounds, HRMS-based approaches provide unparallelled capabilities for discovering unknown contaminants and transformation products. The integration of machine learning with NTA significantly enhances the ability to identify contamination sources through sophisticated pattern recognition in high-dimensional chemical data. As prioritization strategies mature and retention time prediction methods improve, HRMS-NTA workflows are poised to transition from research tools to essential components of regulatory environmental monitoring and chemicals management, ultimately supporting more effective protection of ecosystem and human health.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing ML Models for Real-World Source Tracking

The rapid proliferation of synthetic chemicals has led to widespread environmental pollution through diverse sources such as industrial effluents, household personal care products, and agricultural runoff [11]. Effective contaminant source identification is essential for addressing and managing these pollution issues, yet traditional targeted chemical analysis methods are inherently limited to detecting predefined compounds [11]. Non-targeted analysis (NTA) powered by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) has emerged as a valuable approach for detecting thousands of chemicals without prior knowledge, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant computational challenges [11] [36]. The integration of machine learning (ML) with NTA has redefined the potential for contaminant source identification by enabling the identification of latent patterns within high-dimensional chemical data [11]. This guide explores the complete ML-NTA workflow, objectively comparing the performance of different ML approaches and providing detailed experimental methodologies for researchers and scientists engaged in environmental contaminant tracking and drug development.

Comprehensive Workflow of ML-Assisted NTA

The integration of ML and NTA for contaminant source identification follows a systematic four-stage workflow: (i) sample treatment and extraction, (ii) data generation and acquisition, (iii) ML-oriented data processing and analysis, and (iv) result validation [11]. A brief description for each stage is provided as follows.

Stage (i): Sample Treatment and Extraction

Sample preparation requires careful optimization to balance selectivity and sensitivity. Researchers must find a compromise between removing interfering components and preserving as many compounds as possible with adequate sensitivity [11]. To address this challenge, purification techniques such as solid phase extraction (SPE), Soxhlet extraction, gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) are commonly employed [11]. Notably, SPE is widely employed for its ability to enrich specific compound classes, yet its inherent selectivity for certain physicochemical properties (e.g., polarity) limits broad-spectrum coverage. To address this limitation, broader-range extractions can be achieved by employing multi-sorbent strategies, such as combining Oasis HLB with ISOLUTE ENV+, Strata WAX and WCX [11]. Additionally, green extraction techniques like QuEChERS, microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) can improve efficiency by reducing solvent usage and processing time, particularly for large-scale environmental samples [11].

Stage (ii): Data Generation and Acquisition

HRMS platforms, including quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) and Orbitrap systems, generate complex datasets essential for NTA [11]. Coupled with liquid or gas chromatographic separation (LC/GC), these instruments resolve isotopic patterns, fragmentation signatures, and structural features necessary for compound annotation. Post-acquisition processing involves centroiding, extracted ion chromatogram (EIC/XIC) analysis, peak detection, alignment, and componentization to group related spectral features (e.g., adducts, isotopes) into molecular entities [11]. Quality assurance measures, such as confidence-level assignments (Level 1-5) and batch-specific quality control (QC) samples, ensure data integrity [11]. The output is a structured feature-intensity matrix, where rows represent samples and columns correspond to aligned chemical features, serving as the foundation for ML-driven analysis [11].

Stage (iii): ML-Oriented Data Processing and Analysis

The transition from raw HRMS data to interpretable patterns involves sequential computational steps. Initial preprocessing addresses data quality through noise filtering, missing value imputation (e.g., k-nearest neighbors), and normalization (e.g., TIC normalization) to mitigate batch effects [11]. Exploratory ML-oriented data processing then identifies significant features via univariate statistics (t-tests, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)) and prioritizes compounds with large fold changes. Dimensionality reduction techniques like principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) simplify high-dimensional data, while clustering methods (hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), k-means clustering) group samples by chemical similarity [11]. Supervised ML models, including Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Classifier (SVC), are subsequently trained on labeled datasets to classify contamination sources [11]. Feature selection algorithms (e.g., recursive feature elimination) refine input variables, optimizing model accuracy and interpretability [11].

Stage (iv): Result Validation

Validation ensures the reliability of ML-NTA outputs through a three-tiered approach. First, analytical confidence is verified using certified reference materials (CRMs) or spectral library matches to confirm compound identities [11]. Second, model generalizability is assessed by validating classifiers on independent external datasets, complemented by cross-validation techniques (e.g., 10-fold) to evaluate overfitting risks [11]. Finally, environmental plausibility checks correlate model predictions with contextual data, such as geospatial proximity to emission sources or known source-specific chemical markers [11]. This multi-faceted validation bridges analytical rigor with real-world relevance, ensuring results are both chemically accurate and environmentally meaningful [11].

Comparative Analysis of Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning for Contaminant Source Tracking

Algorithm Selection Framework

Performance Comparison in Environmental Applications

Table 1: Comparative performance of supervised ML algorithms in contaminant classification

| Algorithm | Application Context | Accuracy Range | Key Strengths | Interpretability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | PFAS source classification (222 features, 92 samples) | 85.5-99.5% | Handles high dimensionality, robust to outliers | Moderate (feature importance available) | [11] |

| Support Vector Classifier (SVC) | Water pollution hotspot classification | Not specified | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient | Low (black-box nature) | [37] |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | Contaminant source attribution | Not specified | Computational efficiency, probabilistic outputs | High (coefficient interpretation) | [11] |

| Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) | Source-specific indicator identification | Not specified | Handles multicollinearity, identifies key features | High (variable importance metrics) | [11] |

Table 2: Characteristics of unsupervised vs. supervised learning for contaminant tracking

| Characteristic | Unsupervised Learning | Supervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Unlabeled data, unknown classes | Labeled data with known sources |

| Primary Applications | Exploratory analysis, pattern discovery, clustering | Classification, regression, prediction |

| Common Algorithms | PCA, t-SNE, HCA, k-means | Random Forest, SVM, Logistic Regression |

| Model Interpretability | Generally high (visual clustering patterns) | Varies (high for linear models, low for ensembles) |

| Implementation Speed | Typically faster (no labeling required) | Slower (requires labeled training data) |

| Accuracy Validation | Challenging (no ground truth for clusters) | Straightforward (using test datasets) |

| Best Suited For | Discovering unknown contaminant sources, initial data exploration | Attributing contaminants to known sources, regulatory decisions |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

In a comprehensive study comparing machine learning algorithms for water pollution prediction, ten different supervised and unsupervised ML algorithms were employed to categorize pollution hotspots for the Terengganu River [37]. The research highlighted how the increase and complexity of big data caused by uncertain water quality parameters necessitated efficient algorithms to trace the most accurate pollution hotspots [37]. The results listed all the accurate and efficient ML algorithms for the classification of river pollutions, providing valuable guidance for facilitating river prediction using efficient and accurate algorithms in various water quality scenarios [37].

In PFAS applications, ML classifiers including Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Logistic Regression (LR), and Random Forest (RF) were implemented to successfully screen 222 targeted and suspect per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) as features distributed in 92 samples, with classification balanced accuracy ranging from 85.5 to 99.5% across different sources [11]. This demonstrates the powerful capability of supervised learning approaches for precise contaminant source attribution when adequate labeled data is available.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for ML-NTA workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Application Purpose | Experimental Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oasis HLB & ISOLUTE ENV+ | Multi-sorbent SPE | Broad-spectrum compound extraction | Enhances coverage across different polarity ranges [11] |

| Strata WAX and WCX | Selective SPE | Targeted extraction of specific compound classes | Improves recovery of acidic/basic compounds [11] |

| QuEChERS | Green extraction | Rapid sample preparation with reduced solvent usage | Ideal for large-scale environmental samples [11] |

| HEPES Buffer | Biological and environmental samples | pH stabilization during extraction | Maintains consistent chemical integrity [11] |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Method validation | Quality assurance and compound verification | Essential for quantitative NTA (qNTA) [11] [38] |

| Polystyrene Nanometer Beads | Instrument calibration | Size determination and method validation | Critical for nanoparticle tracking analysis [39] |

| TMC (N-trimethyl chitosan) | Nanoparticle preparation | Drug delivery system characterization | Used in environmental nanomaterial studies [39] |

| PLGA (Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid) | Polymer-based particles | Drug delivery vehicle development | Model system for environmental nanoparticle behavior [39] |

Advanced Methodologies: Quantitative NTA (qNTA) and Effect-Directed Analysis

Bridging the Quantitative Gap

Significant efforts have been made in recent years to bridge the quantitative gap in NTA applications [38]. While traditional NTA has primarily focused on qualitative identification, quantitative NTA (qNTA) approaches are now poised to directly support 21st-century risk-based decisions [38]. The lack of well-defined concentration estimates from NTA measurements has been a fundamental challenge in using NTA data to support chemical safety evaluations [38]. Based on recent advancements, quantitative NTA data, when coupled with other high-throughput data streams and predictive models, can now directly influence the chemical risk assessment process [38].

Effect-Directed Analysis (EDA) Integration

Non-targeted methods can support effect-directed analyses (EDA), wherein complex samples/mixtures are first fractionated, and fractions then individually screened for bioactivity (primarily using in vitro assays) [38]. NTA enables follow-up evaluation of risk drivers within active fractions via compound identification. As a recent example, researchers used EDA and examined sequential fractions of a tire rubber extract, using NTA methods, to identify a quinone transformation product that causes lethality in coho salmon [38]. Other examples include the use of EDA/NTA to identify estrogenic and antiandrogenic compounds in water and biological matrices [38].

While ML-enhanced NTA shows transformative potential for contaminant source tracking, several gaps impede its operationalization in environmental decision-making [11]. The most critical gap lies in the absence of systematic frameworks bridging raw NTA data to environmentally actionable parameters [11]. Current studies place insufficient emphasis on model interpretability; although complex models like deep neural networks can achieve high classification accuracy, their black-box nature limits transparency and hinders the ability to provide chemically plausible attribution rationale required for regulatory actions [11]. The future of ML-NTA integration lies in addressing these challenges through improved model interpretability, robust validation frameworks, and the development of standardized workflows that can be consistently applied across different environmental contexts and contaminant classes. As these methodologies continue to mature, ML-NTA approaches will become increasingly vital tools for environmental monitoring, public health protection, and evidence-based regulatory decision-making [11] [36] [38].