Surface-Modified Chitosan Magnetic Nanoparticles: Advanced Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal from Water

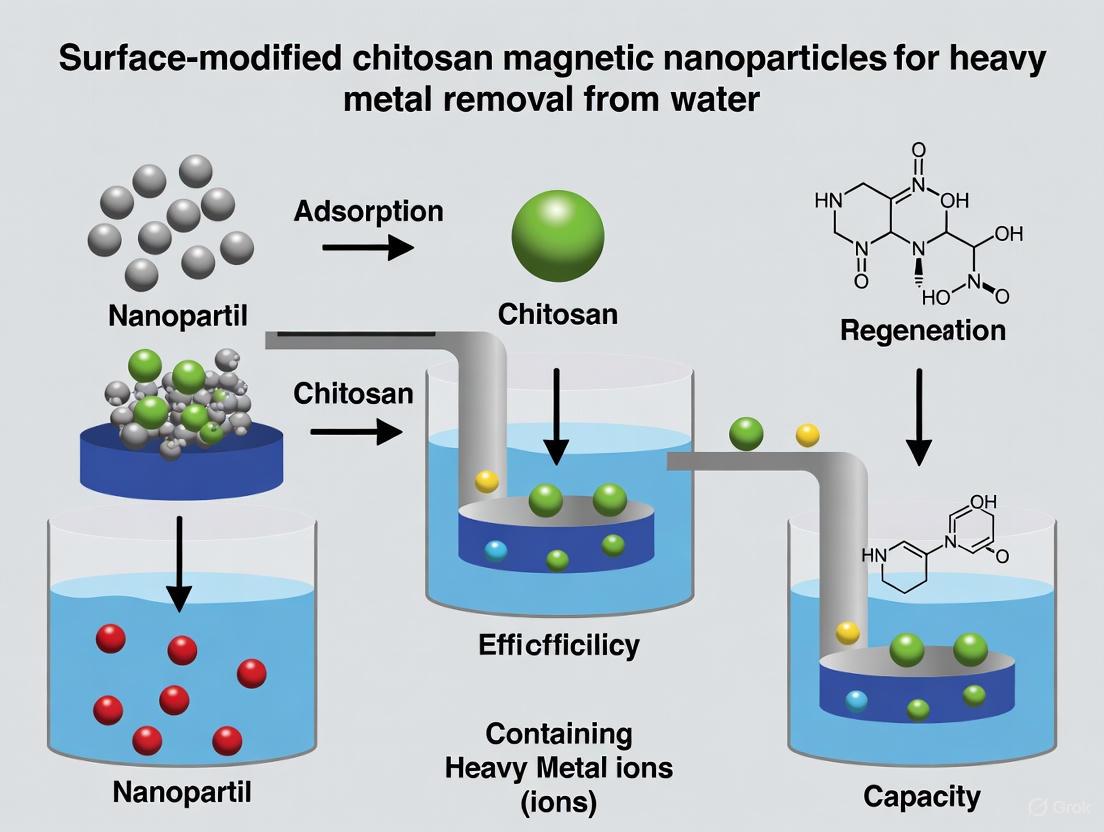

This article comprehensively reviews the development, application, and performance of surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for the removal of heavy metal ions from contaminated water.

Surface-Modified Chitosan Magnetic Nanoparticles: Advanced Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Removal from Water

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the development, application, and performance of surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for the removal of heavy metal ions from contaminated water. Tailored for researchers and scientists in environmental remediation and material science, it covers the foundational science behind chitosan's metal-binding properties and the strategic advantages of magnetic composites. The scope extends to synthesis methodologies, including co-precipitation and cross-linking, and details various surface modification strategies to enhance adsorption capacity and selectivity. It further addresses key operational parameters, troubleshooting for common challenges like aggregation and pH sensitivity, and a comparative validation of performance against other adsorbents. By integrating mechanistic insights, bibliometric trends, and discussions on reusability, this review positions these nano-adsorbents as a sustainable and efficient platform for next-generation water purification technologies.

The Science and Rise of Magnetic Chitosan Nanocomposites

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit) [1]. As the second most abundant natural biopolymer after cellulose, chitosan is derived from chitin, which is primarily found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans (such as shrimp and crabs), insect cuticles, and fungal cell walls [1] [2]. This biopolymer has garnered significant scientific and industrial interest due to its unique properties, including excellent chelation capabilities, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity [3] [4]. The presence of highly reactive functional groups in its molecular structure enables various chemical modifications and facilitates numerous applications, particularly in heavy metal removal from contaminated water systems, which aligns with the broader research on surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for water purification [5] [6].

Structural Characteristics and Functional Groups

Molecular Structure and Composition

Chitosan's molecular structure consists of a linear chain of glycosidic linkages with variable proportions of two primary monomer units: N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) and D-glucosamine (GlcN) [1] [2]. The ratio of these monomers significantly influences the polymer's properties and functionality. Unlike synthetic polymers with well-defined structures, chitosan represents a family of molecules with variations in molecular weight, composition, and monomer distribution, which fundamentally affects its biological and technological performance [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Parameters of Chitosan

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Degree of Deacetylation (DD) | Percentage of D-glucosamine units in the polymer chain | Higher DD increases charge density, solubility in acidic media, and chelation capacity [1] |

| Molecular Weight | Ranges from low (oligomers) to high molecular weight polymers | Lower MW increases solubility range; higher MW affects viscosity and mechanical strength [1] [2] |

| Sequence Distribution | Random or block distribution of GlcNAc and GlcN units | Affects crystallinity, enzymatic degradation, and accessibility to functional groups [1] |

Key Functional Groups

The chelating capability and chemical reactivity of chitosan primarily originate from three key functional groups present on its molecular backbone:

- Primary Amino Groups (-NH₂) at the C-2 position: These groups are the most reactive and primarily responsible for chitosan's cationic nature in acidic conditions and its superior metal chelation capability through coordination bonds [6] [3]. The amino group becomes protonated (-NH₃⁺) in acidic media, enabling electrostatic interactions with anionic species [1].

- Primary Hydroxyl Groups (-OH) at the C-6 position: These groups participate in hydrogen bonding and can be modified for specific applications, though they are less reactive than amino groups [1] [2].

- Secondary Hydroxyl Groups (-OH) at the C-3 position: These groups contribute to the overall hydrophilicity and structural conformation of the polymer chain [2].

The presence of these multiple functional groups makes chitosan a multifunctional ligand capable of forming complexes with various metal ions through different mechanisms, including coordination, ion exchange, and electrostatic interactions [5] [6].

Natural Chelating Properties and Mechanisms

Fundamental Chelation Mechanisms

Chitosan exhibits remarkable chelation properties toward heavy metal ions through several simultaneous mechanisms. The primary amino groups serve as coordination sites for metal ions, forming stable complexes [6] [3]. The chelation capability stems from the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen atoms, which can coordinate with empty orbitals of metal cations [3]. In acidic environments, the protonated amino groups also facilitate electrostatic attraction between chitosan and metal anions [5]. The hydroxyl groups may participate in metal binding, particularly for metals that prefer oxygen coordination, though this contribution is secondary to that of the amino groups [6].

Quantitative Chelation Performance

Table 2: Chelation Performance of Chitosan and Derivatives for Heavy Metals

| Metal Ion | Adsorption Capacity (μmol/g) | Optimal pH Range | Key Interaction Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (Cu²⁺) | Up to 4700 [7] | 4-6 [6] | Coordination with amino groups, chelation [5] |

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Up to 2700 [7] | 5-7 [6] | Coordination, electrostatic attraction [5] |

| Cadmium (Cd²⁺) | Up to 1800 [7] | 6-8 [6] | Coordination, ion exchange [5] |

| Chromium (Cr⁶⁺) | Varies with derivative [4] | 3-5 [6] | Electrostatic attraction, reduction to Cr³⁺ [4] |

The adsorption performance varies significantly based on the chitosan's physicochemical properties (degree of deacetylation, molecular weight) and environmental conditions (pH, temperature, competing ions) [5] [6]. The adsorption process typically follows pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Langmuir isotherm model, suggesting monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface [5] [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Chitosan Nanoparticles via Ionic Gelation

Principle: This method utilizes the electrostatic interaction between positively charged chitosan amino groups and negatively charged polyanions such as tripolyphosphate (TPP) to form nanoparticles through self-assembly [8].

Materials:

- Chitosan (medium molecular weight, >75% deacetylation)

- Sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP)

- Acetic acid (1% v/v)

- Magnetic stirrer with hot plate

- Ultrasonic homogenizer

Procedure:

- Dissolve chitosan powder in 1% acetic acid solution at a concentration of 2 mg/mL under constant magnetic stirring at room temperature for 24 hours to ensure complete dissolution [8].

- Prepare TPP solution in deionized water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL.

- Add TPP solution dropwise into the chitosan solution at a rate of 0.5 mL/min using a burette or syringe pump while homogenizing at 5,000 rpm with a Polytron homogenizer [8].

- Continue stirring for an additional 60 minutes after complete addition of TPP to allow nanoparticle formation.

- Characterize the resulting nanoparticles for size distribution (85-221 nm range expected), zeta potential, and morphology using dynamic light scattering and electron microscopy [8].

Applications: The synthesized chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) can be used as a final irrigant in root canal treatment with the dual benefit of removing smear layer and inhibiting bacterial recolonization on root dentin, demonstrating a chelation capacity significantly reducing smear layer (p < 0.05) and resisting biofilm formation better than control treatments [8].

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Chelation Capacity Using Batch Equilibrium

Principle: This protocol measures the metal ion adsorption capacity of chitosan materials under controlled conditions to quantify chelation performance [5] [7].

Materials:

- Chitosan-based adsorbent (nanoparticles, films, or beads)

- Metal salt solutions (Pb(NO₃)₂, CuSO₄, CdCl₂, etc.)

- pH meter and buffers

- Orbital shaker incubator

- Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS) or ICP-OES

Procedure:

- Prepare standard solutions of target heavy metals (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Cd²⁺) at concentrations ranging from 50-500 mg/L in deionized water [7].

- Adjust pH of solutions to optimal range (typically 5-6) using dilute HNO₃ or NaOH.

- Add a known quantity of chitosan adsorbent (e.g., 0.1 g) to each metal solution (50 mL) in Erlenmeyer flasks.

- Agitate flasks in an orbital shaker at constant temperature (25±1°C) and speed (150 rpm) for predetermined time intervals (10 min to 24 hours) [7].

- Separate the adsorbent from solution by centrifugation or filtration after equilibration.

- Analyze the supernatant for residual metal concentration using AAS or ICP-OES.

- Calculate adsorption capacity using the formula: [ qe = \frac{(Co - Ce) \times V}{m} ] where ( qe ) = adsorption capacity (mg/g), ( Co ) = initial concentration (mg/L), ( Ce ) = equilibrium concentration (mg/L), V = solution volume (L), and m = adsorbent mass (g) [5].

Applications: This standardized protocol enables comparison of different chitosan-based adsorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater, with typical equilibrium times of 10-30 minutes and maximum adsorption capacities as indicated in Table 2 [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chitosan Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (varying DD & MW) | Primary biopolymer for adsorption studies | Select based on application: higher DD for enhanced metal binding [1] |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Crosslinker for nanoparticle synthesis | Forms ionic bonds with protonated amino groups [8] |

| Acetic Acid (1% v/v) | Solvent for chitosan | Protonates amino groups enabling solubilization [1] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for chitosan beads | Enhances mechanical stability in acidic conditions [5] |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Comparative chelating agent | Reference compound for chelation efficiency studies [8] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) | Core for magnetic chitosan composites | Enables magnetic separation after adsorption [7] [4] |

Structural and Chelation Workflow

Chitosan's fundamental structure, characterized by the presence of highly reactive amino and hydroxyl functional groups, establishes its remarkable natural chelating properties toward heavy metal ions. The protocols outlined herein provide standardized methodologies for synthesizing chitosan nanoparticles and evaluating their chelation capacity, essential for advancing research on surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for water remediation. The quantitative data presented offers benchmarks for comparing adsorption performance across different chitosan-based materials. As research progresses, the precise understanding of structure-function relationships in chitosan and its derivatives will continue to enable the rational design of more efficient and selective adsorbents for environmental applications.

In the development of surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for heavy metal removal, the magnetic core is a foundational component that critically determines the functionality and practicality of the adsorbent. These composites integrate the excellent adsorption properties of chitosan, a biopolymer, with the separation capability and * stability* conferred by magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) like magnetite (Fe₃O₄) [9]. The magnetic core addresses a key limitation of powdered nano-adsorbents—difficult and costly solid-liquid separation—by enabling rapid retrieval from treated water using an external magnetic field [9] [10]. This application note details the roles, synthesis, and characterization of Fe₃O₄ and other ferrite nanoparticles, providing essential protocols for researchers developing these materials for water purification.

The Magnetic Core: Composition and Function

Common Magnetic Nanoparticles

The most commonly used magnetic materials in chitosan composites are iron oxides, prized for their strong magnetic properties, chemical stability, and biocompatibility [11] [12].

- Magnetite (Fe₃O₄): The predominant choice for magnetic cores due to its high saturation magnetization, superparamagnetism at the nanoscale, and ease of synthesis [11] [12]. Its isoelectric point allows for straightforward surface functionalization.

- Maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃): Another iron oxide phase often used, though it has a slightly lower magnetic saturation compared to Fe₃O₄ [4].

- Doped Ferrites (MFe₂O₄): Metals such as Mn, Cu, Zn, Ni, or Co can be incorporated into the ferrite structure to form MFe₂O₄, sometimes used to tailor magnetic properties or catalytic activity [9] [4].

Primary Roles of the Magnetic Core

The incorporation of a magnetic core serves two critical functions:

- Facile Separation and Recovery: The primary role is to impart superparamagnetism to the composite material. This allows for near-instantaneous separation from the aqueous phase upon application of an external magnet, eliminating the need for costly or time-intensive filtration or centrifugation steps [9] [10]. This feature is crucial for the economic reusability of the adsorbent.

- Enhanced Stability and Structure: The magnetic nanoparticles can act as a structural scaffold. The chitosan matrix coating the magnetic cores helps to prevent their oxidation and aggregation [9]. In return, the cores can improve the mechanical stability of the chitosan and enhance its resistance in acidic environments, where pure chitosan is often unstable [9] [4].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for synthesizing and applying magnetic chitosan nanoparticles for heavy metal removal, highlighting the central role of the magnetic core and its characterization.

Synthesis and Modification Protocols

Synthesis of the Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Core

The co-precipitation method is the most widely used technique for synthesizing Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles due to its simplicity and efficiency [11] [10].

Detailed Protocol: Co-precipitation of Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles

Research Reagent Solutions:

- 1 M FeCl₃·6H₂O solution: Source of Fe³⁺ ions.

- 1 M FeSO₄·7H₂O solution: Source of Fe²⁺ ions. Critical: Prepare fresh and under an inert atmosphere (e.g., N₂ purge) to prevent oxidation.

- Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH, 28-30%): Precipitating agent.

- Deoxygenated Water: Purge distilled water with N₂ for 30 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

Procedure:

- In a three-neck round-bottom flask under a constant N₂ atmosphere and mechanical stirring (500-1000 rpm), mix 100 mL of 1 M FeCl₃ and 50 mL of 1 M FeSO₄. The molar ratio of Fe³⁺:Fe²⁺ should be maintained at 2:1.

- Heat the reaction mixture to 70°C.

- While stirring vigorously, rapidly add 50 mL of NH₄OH dropwise to the solution. The immediate formation of a black precipitate indicates the formation of magnetite.

- Continue stirring for 1 hour at 70°C under N₂ to allow for complete particle growth.

- Cool the mixture to room temperature. Separate the black Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles from the supernatant using a laboratory magnet.

- Wash the nanoparticles repeatedly with deoxygenated water and ethanol until the supernatant reaches a neutral pH.

- Re-disperse the purified Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles in 100 mL of distilled water for immediate use in chitosan coating, or freeze-dry for storage.

Table 1: Common Synthesis Methods for Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles [11] [12]

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-precipitation | Rapid precipitation of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ salts in a basic medium. | Simple, efficient, high yield, can be performed in water. | Broad size distribution, control over shape is limited. |

| Thermal Decomposition | Decomposition of organometallic precursors at high temperature. | Excellent control over size and shape, narrow size distribution. | Requires organic solvents, high temperature, complex procedure. |

| Hydrothermal/Solvothermal | Reaction in a sealed vessel at high temperature and pressure. | Good crystallinity, good control over particle morphology. | Requires high pressure/temperature, longer reaction times. |

| Microbial/Green Synthesis | Use of plant extracts or microorganisms to reduce ions. | Environmentally friendly, uses non-toxic chemicals. | Time-consuming fermentation, challenging to control size. |

Protocol: Fabrication of Magnetic Chitosan Composite (MCBMs)

This protocol describes the synthesis of core-shell magnetic chitosan beads via a cross-linking method [13] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticle Dispersion (from Protocol 3.1)

- Chitosan Solution (2% w/v): Dissolve 2 g of medium molecular weight chitosan in 100 mL of aqueous acetic acid (1% v/v).

- Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) Cross-linker Solution (1% w/v)

- Glutaraldehyde Solution (2% v/v) (optional, for additional cross-linking)

Procedure:

- Dispersion: Add 200 mg of the freshly prepared, wet Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles to the 2% chitosan solution. Stir vigorously for 1 hour and then sonicate for 15 minutes to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Droplet Formation: Using a syringe pump with a 21-gauge needle, drop the magnetic chitosan solution into 100 mL of the gently stirred TPP solution. The TPP acts as an ionic cross-linker, instantly gelling the droplets into beads.

- Curing: Allow the beads to cure in the TPP solution for 1 hour under slow stirring.

- Cross-linking (Optional) : For enhanced acid stability, transfer the beads to the glutaraldehyde solution for 30 minutes.

- Washing and Storage: Separate the beads magnetically, wash thoroughly with distilled water until neutral pH, and store in water at 4°C.

Characterization of the Magnetic Core and Composite

Rigorous characterization is essential to confirm the successful synthesis and desired properties of the magnetic core and final composite.

Table 2: Key Characterization Techniques for the Magnetic Core and Composite [13] [11] [14]

| Technique | Information Gained | Ideal Outcome for Application |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystal structure, phase purity, and crystallite size of the magnetic core. | Distinct peaks matching the Fe₃O₄ spinel structure, confirming successful synthesis. |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) | Chemical bonds and functional groups; confirms chitosan coating and surface modification. | Presence of Fe–O bond (~580 cm⁻¹) and chitosan bands (N-H, C-O), confirming composite formation. |

| Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM) | Magnetic properties: saturation magnetization (M_s), coercivity. | High M_s (e.g., >40 emu/g for pure Fe₃O₄), superparamagnetic behavior (no hysteresis). |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Particle size, morphology, and core-shell structure. | Clear core-shell structure with well-dispersed, nano-sized particles. |

| Surface Area Analysis (BET) | Specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution. | High surface area (>40 m²/g) to provide abundant adsorption sites. |

Detailed Protocol: Measuring Saturation Magnetization with VSM

- Objective: To quantify the magnetic strength of the synthesized Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles and the final magnetic chitosan composite, which directly impacts separation efficiency.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 20-50 mg of the freeze-dried powder sample.

- Loading: Pack the sample securely into a non-magnetic sample holder (e.g., a gelatin capsule or quartz tube).

- Measurement: Place the holder in the VSM. Run the measurement by applying an external magnetic field that sweeps from a large negative value to a large positive value and back (e.g., -20,000 Oe to +20,000 Oe) at room temperature.

- Data Analysis: From the resulting hysteresis loop (M-H curve), determine the saturation magnetization (Ms) value. For effective magnetic separation, the composite should retain a high Ms. For example, a composite might show an M_s of 36 emu/g, which, while lower than pure Fe₃O₄ (~57 emu/g), is still sufficient for rapid magnetic separation [14].

Performance and Stability Data

The performance of magnetic chitosan composites is evaluated based on their adsorption capacity and reusability, both dependent on the magnetic core's properties.

Table 3: Adsorption Performance of Selected Magnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metals [9] [13]

| Magnetic Composite | Target Heavy Metal | Reported Adsorption Capacity | Key Factors Influencing Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-Fe₃O₄ coated with Chitosan | Pb(II) | 2700 μmol/g | pH, initial concentration, presence of competing ions. |

| Nano-Fe₃O₄ coated with Chitosan | Cu(II) | 4700 μmol/g | pH, surface modification with functional groups. |

| Nano-Fe₃O₄ coated with Chitosan | Cd(II) | 1800 μmol/g | Solution pH, adsorbent dosage, contact time. |

| MCBMs (General) | Cr(VI) | Varies with modification | Often involves a reduction-coupled adsorption mechanism. |

Stability and Reusability: A critical advantage of MCBMs is their regenerability. Studies show that these composites can often undergo multiple adsorption-desorption cycles (e.g., 5 or more) with only a minor loss in capacity [9] [14]. The magnetic separation capability is key to enabling this reusability without significant material loss.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Magnetic Core Synthesis and Composite Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Justification for Use |

|---|---|---|

| FeCl₃·6H₂O / FeSO₄·7H₂O | Fe³⁺ and Fe²⁺ precursors for Fe₃O₄ synthesis. | Standard, high-purity salts for reproducible co-precipitation; 2:1 molar ratio is stoichiometric for magnetite. |

| Ammonium Hydroxide (NH₄OH) | Precipitating and alkalizing agent. | Provides a basic environment (pH ~9-14) required for the instantaneous precipitation of Fe₃O₄. |

| Chitosan (Medium Mol. Wt.) | Biopolymer matrix for coating and functionalization. | Provides amino and hydroxyl groups for metal binding; biocompatible and biodegradable. |

| Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic cross-linker. | Forms ionic bonds with protonated NH₃⁺ groups of chitosan, creating stable hydrogel beads. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Covalent cross-linker. | Reacts with amino groups of chitosan, enhancing mechanical and chemical stability in acidic water. |

The magnetic core, predominantly composed of Fe₃O₄, is indispensable for creating practical and effective chitosan-based adsorbents for heavy metal removal. Its roles in enabling rapid magnetic separation and enhancing the structural stability of the composite are crucial for transitioning from laboratory research to real-world water treatment applications. By following the detailed synthesis, modification, and characterization protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can systematically develop and optimize next-generation magnetic chitosan nanomaterials for environmental remediation.

The remediation of heavy metal contamination in water systems represents a significant global challenge, driven by industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and improper waste disposal [15]. These pollutants, including lead, mercury, cadmium, chromium, and arsenic, pose severe risks to ecosystem integrity and human health due to their toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation potential [4] [15]. While various water treatment technologies exist, adsorption-based methods have gained prominence for their operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency across different contaminant concentrations [4] [16].

Among adsorbents, chitosan—a natural polysaccharide derived from chitin—has emerged as a promising candidate due to its abundance, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and exceptional chelating properties attributable to abundant amino (–NH₂) and hydroxyl (–OH) functional groups [16] [17]. However, native chitosan suffers from limitations including solubility in acidic media, limited mechanical strength, and challenging separation from treated water [4] [17].

The integration of chitosan with magnetic nanoparticles creates a composite material that synergizes the superior adsorption capabilities of chitosan with the facile, rapid magnetic separation offered by iron oxide components [4] [18]. This combination addresses key practical limitations and enhances the overall feasibility of water treatment applications. These magnetic chitosan nanoparticles (MCNPs) represent a significant advancement in adsorbent design, enabling efficient heavy metal removal with simplified operational procedures [19].

Synergistic Mechanisms and Functional Advantages

The enhanced performance of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles stems from several interconnected mechanisms that operate synergistically.

Primary Synergistic Mechanisms

- Chelation and Coordination Bonding: The amino and hydroxyl groups on chitosan chains serve as electron donors, forming stable complexes with heavy metal ions through coordination bonds. This mechanism is particularly effective for metals like Cu(II), Cd(II), and Pb(II) [16] [17].

- Electrostatic Interactions: In acidic conditions, chitosan's amino groups undergo protonation, generating positively charged sites that attract anionic metal species such as chromate (CrO₄²⁻) through Coulombic forces [20] [17].

- Surface Adsorption and Ion Exchange: The high surface area-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles provides numerous active sites for metal binding, while functional groups can participate in ion-exchange processes with metal cations in solution [16].

- Magnetic Responsiveness: Incorporated iron oxide cores (typically Fe₃O₄ or γ-Fe₂O₃) impart superparamagnetic properties, enabling rapid separation (<5 minutes) under an external magnetic field without filtration or centrifugation [4] [18].

Material Property Enhancements

- Improved pH Stability: Cross-linking during composite formation reduces chitosan solubility across acidic pH ranges, expanding operational windows for treatment systems [20] [17].

- Enhanced Mechanical Robustness: The composite structure exhibits greater resistance to mechanical degradation compared to pure chitosan, supporting multiple adsorption-desorption cycles [18].

- Increased Surface Reactivity: Nanoscale dimensions and functional group accessibility significantly enhance adsorption kinetics and capacity relative to bulk chitosan materials [16] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between chitosan's reactivity and magnetic functionality in the composite material:

Synthesis Protocols and Methodologies

Preparation of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles (MCNPs) via Co-precipitation

The co-precipitation method represents the most widely utilized approach for synthesizing MCNPs due to its simplicity and effectiveness [4] [19].

Reagents and Equipment

Table 1: Reagents for MCNP Synthesis via Co-precipitation

| Reagent | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Low molecular weight (50-190 kDa), >75% deacetylation | Primary adsorbent matrix providing functional groups |

| FeCl₃·6H₂O | Analytical grade ≥98% | Iron source for magnetic component (Fe³⁺) |

| FeSO₄·7H₂O | Analytical grade ≥99% | Iron source for magnetic component (Fe²⁺) |

| Ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH) | 25-30% solution | Precipitation agent for iron oxides |

| Glacial acetic acid | Analytical grade ≥99% | Solvent for chitosan dissolution |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Pellets, analytical grade | pH adjustment |

| Deionized water | Resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm | Solvent and washing |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Chitosan Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.0 g of chitosan powder in 100 mL of aqueous acetic acid solution (1% v/v) with continuous mechanical stirring at 40°C for 2 hours until a clear, viscous solution forms [21].

Iron Solution Preparation: Dissolve 2.0 g of FeCl₃·6H₂O and 1.0 g of FeSO₄·7H₂O in 50 mL of deionized water under nitrogen atmosphere with vigorous stirring (molar ratio Fe³⁺:Fe²⁺ = 2:1) [19].

Magnetic Precipitation: Slowly add the iron solution to the chitosan solution while maintaining vigorous stirring (800-1000 rpm) at 40°C. Gradually add ammonium hydroxide (25% solution) until the pH reaches 10-11 to precipitate magnetite nanoparticles within the chitosan matrix [19].

Aging and Washing: Maintain the reaction mixture at 40°C for 1 hour with continuous stirring. Collect the black magnetic chitosan precipitate using a permanent magnet and wash repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol until neutral pH is achieved [18].

Drying: Dry the synthesized MCNPs in a vacuum oven at 50°C for 12 hours. Grind the dried product to obtain a fine powder for characterization and application [20].

Surface Functionalization with Quaternary Ammonium Groups

Quaternary modification enhances adsorption capacity for anionic metal species through increased positive charge density [20] [17].

Additional Reagents

- Glycidyl trimethyl ammonium chloride (GTMAC) ≥95%

- Glutaraldehyde solution (25%) for cross-linking

Functionalization Procedure

Cross-linking: Suspend 2.0 g of prepared MCNPs in 50 mL of deionized water. Add 2 mL of glutaraldehyde solution (25%) and react at 60°C for 3 hours with continuous stirring to enhance chemical stability [20].

Quaternization: Add 3.94 g of GTMAC (2:1 molar ratio to chitosan repeating units) to the cross-linked MCNP suspension. React at 80°C for 8 hours with constant stirring [20].

Purification: Separate the functionalized MCNPs magnetically and wash thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove unreacted reagents.

Drying: Dry the final product (QMCNPs) at 50°C for 12 hours before use [20].

Synthesis Workflow

The complete synthesis process from raw materials to functionalized magnetic chitosan nanoparticles follows this sequential workflow:

Characterization Techniques and Performance Validation

Essential Characterization Methods

Comprehensive characterization ensures successful MCNP synthesis and predicts application performance.

Table 2: Essential Characterization Techniques for MCNPs

| Technique | Parameters Analyzed | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Functional groups, chemical bonds | Presence of characteristic bands: -NH₂ (1650 cm⁻¹), -OH (3450 cm⁻¹), Fe-O (570 cm⁻¹) [21] [20] |

| XRD Analysis | Crystallinity, phase identification | Characteristic peaks for Fe₃O₄ at 2θ = 30.1°, 35.5°, 43.1°, 57.0°, 62.6° [18] [20] |

| SEM/TEM Imaging | Morphology, size distribution, surface topography | Spherical particles with 10-100 nm diameter, chitosan coating on magnetic cores [21] [22] |

| VSM Analysis | Magnetic properties | Saturation magnetization 30-60 emu/g, superparamagnetic behavior [18] [22] |

| BET Surface Area | Specific surface area, porosity | 50-200 m²/g, mesoporous structure [19] |

| Zeta Potential | Surface charge, colloidal stability | Positive charge (+20 to +40 mV) across acidic to neutral pH [21] [20] |

| TGA Analysis | Thermal stability, composition | ≤10% weight loss at 650°C, indicating high thermal stability [18] |

Adsorption Performance Evaluation

Standardized testing protocols evaluate MCNP effectiveness for heavy metal removal.

Batch Adsorption Experiments

Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions (1000 mg/L) of target heavy metals (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Cr⁶⁺, etc.) from certified nitrate or chloride salts. Dilute to desired concentrations (10-500 mg/L) for experiments [20] [19].

Effect of pH: Adjust solution pH (2-8) using 0.1M HNO₃ or NaOH. Add 10 mg of MCNPs to 50 mL of metal solution (50 mg/L). Shake at 150 rpm for 120 minutes at 25°C [19].

Adsorption Kinetics: Use fixed pH (optimal for target metal), varying contact time (1-360 minutes). Sample at predetermined intervals, separate MCNPs magnetically (2-5 minutes), and analyze supernatant metal concentration [20] [19].

Adsorption Isotherms: Vary initial metal concentration (10-500 mg/L) with fixed adsorbent dose (0.2 g/L), pH, and contact time (until equilibrium) at different temperatures (15-35°C) [18] [19].

Analytical Methods

- Metal Concentration Analysis: Use atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) or inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) with appropriate calibration standards [15].

- Adsorption Capacity Calculation: Determine adsorption capacity qₑ (mg/g) using: qₑ = (C₀ - Cₑ)×V/m, where C₀ and Cₑ are initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), V is solution volume (L), and m is adsorbent mass (g) [20] [19].

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental data from recent studies demonstrates the effectiveness of various magnetic chitosan composites for heavy metal removal.

Table 3: Adsorption Performance of Magnetic Chitosan Composites for Heavy Metals

| Adsorbent Type | Target Heavy Metal | Optimal pH | Equilibrium Time (min) | Maximum Capacity (mg/g) | Adsorption Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternized Magnetic Chitosan | Methyl Orange (model anionic compound) | 4.0 | 120 | 486.13 | Electrostatic interaction, ion exchange | [20] |

| Magnetic Chitosan Functionalized with Heterocyclic Compounds | Cd²⁺ | 6.0 | 120 | 270.27 | Chelation, coordination | [19] |

| Chitosan-modified Fe₃O₄ Microspheres | Flavonoids (catechol structure) | - | - | 147.06 | Hydrogen bonding, π-interactions | [18] |

| Cross-linked Magnetic Chitosan | Cr(VI) | 3.0 | 180 | ~200 (estimated) | Electrostatic attraction, reduction to Cr(III) | [17] |

| Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles | Various heavy metals in multi-ion systems | Varies by metal | 60-180 | 150-300 | Coordination, ion exchange | [4] |

Regeneration and Reusability Protocols

Sustainable application of MCNPs requires effective regeneration and reuse capabilities.

Desorption and Regeneration Procedure

Metal Desorption: After adsorption, separate MCNPs magnetically and immerse in 50 mL of desorbing agent (0.1M NaOH for anionic species; 0.1M EDTA or 0.1M HNO₃ for cationic metals) for 6 hours with gentle shaking [20] [19].

Washing and Reconditioning: Separate desorbed MCNPs magnetically, wash thoroughly with deionized water until neutral pH, and dry at 50°C for 6 hours before reuse [18].

Performance Monitoring: Track adsorption capacity retention over multiple cycles (typically 5-7 cycles) to assess long-term viability [18] [22].

Regeneration Efficiency Data

Table 4: Regeneration Performance of Magnetic Chitosan Adsorbents

| Adsorbent Type | Heavy Metal | Desorption Agent | Cycles Tested | Capacity Retention | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan-modified Fe₃O₄ | Flavonoids | 70% Methanol | 3 | >90% | Minimal structural degradation, stable magnetization [18] |

| Fe₃O₄/CHT-Pd Nanocatalyst | (Catalytic application) | - | 7 | No significant loss | Maintained catalytic activity, structural integrity [22] |

| Quaternized Magnetic Chitosan | Methyl Orange | 0.1M NaOH | 5 | >85% | Good chemical stability, sustained positive charge [20] |

| Functionalized Magnetic Chitosan with Heterocyclic Compounds | Cd²⁺ | 0.1M EDTA | 4 | >80% | Effective metal recovery, stable functional groups [19] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MCNP Development

| Reagent Solution | Composition | Preparation | Primary Function | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan Solvent | 1% (v/v) acetic acid in deionized water | Add 10 mL glacial acetic acid to 990 mL DI water | Dissolves chitosan polymer via protonation of amino groups | Room temperature, sealed container |

| Iron Co-precipitation Solution | Fe³⁺:Fe²⁺ (2:1 molar ratio) in DI water | Dissolve FeCl₃·6H₂O (2.0 g) and FeSO₄·7H₂O (1.0 g) in 50 mL DI water under N₂ | Forms magnetite (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles | Fresh preparation recommended |

| Alkaline Precipitation Agent | 25% NH₄OH solution in DI water | Dilute concentrated NH₄OH (28-30%) with DI water | Increases pH to 10-11 for magnetite precipitation | Room temperature, fume hood |

| Cross-linking Solution | 2.5% glutaraldehyde in DI water | Dilute 25% glutaraldehyde stock 1:10 with DI water | Forms stable Schiff bases with chitosan amino groups | 4°C, dark container |

| Quaternary Modification Reagent | 10% GTMAC in DI water | Dissolve glycidyl trimethyl ammonium chloride in DI water | Introduces quaternary ammonium groups | 4°C, desiccator |

| Desorption Solution | 0.1M NaOH or 0.1M HNO₃ in DI water | Dissolve 4.0 g NaOH or 6.3 mL HNO₃ in 1L DI water | Regenerates spent adsorbent by metal ion release | Room temperature |

Application Notes and Implementation Considerations

Optimization Parameters for Specific Applications

Successful implementation of MCNP technology requires optimization based on specific water treatment scenarios:

pH Optimization: Anionic metal species (CrO₄²⁻) show enhanced adsorption at acidic pH (3-4), while cationic metals (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) typically exhibit optimal removal near neutral conditions (pH 5-7) [20] [19].

Dosage Optimization: Effective adsorbent doses typically range from 0.2-2.0 g/L depending on initial metal concentration and required removal efficiency [19].

Interference Management: In multi-metal systems, competitive adsorption occurs, requiring either selective functionalization or pretreatment strategies [4].

Kinetic Considerations: Most systems reach equilibrium within 60-120 minutes, with initial rapid adsorption followed by slower intraparticle diffusion [18] [19].

Scale-up Considerations

Translating laboratory success to practical application involves addressing several key factors:

Magnetic Separation Efficiency: Design magnetic separation systems capable of processing large volumes with minimal retention time (typically <10 minutes) [4] [18].

Mass Transfer Limitations: Optimize mixing conditions to ensure sufficient contact between adsorbents and contaminants while avoiding excessive shear forces that could damage nanoparticles [16].

Regeneration Infrastructure: Implement efficient adsorbent regeneration systems compatible with continuous or semi-continuous operation [18] [20].

Lifecycle Management: Develop protocols for eventual replacement and environmentally responsible disposal of spent adsorbent materials [16].

The synergistic combination of chitosan's reactivity and magnetic functionality creates a versatile platform for advanced water treatment applications, offering efficient heavy metal removal coupled with practical operational advantages. Continued research focuses on enhancing selectivity, capacity, and long-term stability under diverse application conditions.

The field of nano-chitosan research represents a dynamic and rapidly evolving scientific domain, positioned at the intersection of materials science, environmental technology, and nanotechnology. Chitosan, a linear polysaccharide derived from the deacetylation of chitin, has emerged as a pivotal biomaterial due to its exceptional properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low toxicity [23] [24]. The transformation of chitosan into nano-scale formulations has significantly amplified its functional attributes, leading to expanded applications across diverse sectors with particular emphasis on environmental remediation, specifically heavy metal removal from water systems [16] [25].

This analysis employs bibliometric methodologies to quantitatively assess the growth trajectories, collaborative networks, and research fronts within the nano-chitosan domain. The insights generated are contextualized within a broader thesis framework investigating surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles for aquatic heavy metal remediation, providing both a macroscopic overview of the research landscape and microscopic technical protocols essential for experimental implementation.

Global Research Landscape and Growth Trajectory

The nano-chitosan research domain has experienced exponential growth over the past decade, reflecting its increasing importance as a sustainable material solution. Bibliometric data reveals a substantial publication output, with the broader chitosan field encompassing 8,002 documents related to sustainable development alone as of 2023 [23]. This substantial body of literature underscores the global scientific interest in leveraging chitosan's unique properties for addressing contemporary environmental challenges.

Table 1: Global Publication Metrics in Chitosan Research

| Bibliometric Indicator | Value | Time Period | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total documents on chitosan for sustainable development | 8,002 | 1976-2023 | Scopus [23] |

| Annual publication peak | 1,178 | 2022 | Scopus [23] |

| Documents on magnetic chitosan adsorption | 1,046 | Last 5 years | Web of Science [9] |

| Documents on "magnetic chitosan" + "adsorption" | 1,316 | Last 5 years | Web of Science [4] |

| Documents specifically on MCBMs for heavy metals | >250 | As of 2024 | Web of Science [9] |

Geographically, research productivity and impact demonstrate distinct patterns. China leads in quantitative output with 1,560 total documents on chitosan for sustainable development, while the United States produces the most impactful research with 55,019 total citations and an h-index of 110 [23]. International collaboration is a defining characteristic of the field, with India exhibiting the highest level of cooperative research engagement with 572 total link strength in international partnerships [23].

Table 2: National Research Output and Impact in Chitosan Research

| Country | Total Documents | Total Citations | h-index | International Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 1,560 | Not specified | Not specified | Moderate |

| United States | Not specified | 55,019 | 110 | Not specified |

| India | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 572 (link strength) |

| European Nations | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Moderate |

The market projections for chitosan nanoparticles further substantiate the field's robust growth potential. The global market is poised to reach an estimated $1.5 billion by 2025, with a projected Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 18% through 2033 [26]. In the United States specifically, the chitosan market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 7.4% from 2025 to 2035, potentially reaching $909.9 million by 2035 [27]. This commercial expansion is critically underpinned by sustained research activity and technological innovation in the nano-chitosan domain.

Intellectual Structure and Research Fronts

Co-word analysis and keyword mapping reveal the intellectual structure of nano-chitosan research, highlighting both established and emerging thematic concentrations. The strongest keyword associations include "adsorption," "heavy metal," "heavy metal ion," and "dye" in relation to magnetic chitosan [9]. These associations clearly indicate that environmental applications, particularly water purification, constitute a central research front.

The analytical focus on heavy metal removal is further refined to specific metallic contaminants, with significant research attention dedicated to Cu(II), Cr(VI), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) [9]. The adsorption mechanisms for these contaminants vary, with high-valence heavy metals such as Cr(VI) undergoing a process of "reduction followed by adsorption" [9]. The research landscape also reveals growing interest in multi-metal coexistence systems and their associated synergistic/competitive effects on adsorption efficiency [4].

Beyond environmental applications, emerging research fronts include:

- Pharmaceutical applications: Particularly drug delivery systems, wound healing, and tissue engineering [28] [29] [24]

- Advanced materials development: Including stimuli-responsive nanoparticles and functionalized composites [26]

- Sustainable packaging: Leveraging chitosan's biodegradable and antimicrobial properties [27]

The concentration of research activity is evidenced by the identification of core publication venues, with "International Journal of Biological Macromolecules," "Carbohydrate Polymers," and "Polymers" emerging as the leading journals publishing chitosan-related research [23].

Experimental Protocols for Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

Synthesis of Magnetic Chitosan-Based Materials (MCBMs)

The synthesis of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles for heavy metal adsorption employs several well-established methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 3: Standard Methods for Chitosan Nanoparticle Synthesis

| Synthesis Method | Key Features | Typical Particle Size | Common Cross-linkers/Agents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Cross-Linking | Enhanced structural integrity; controlled particle size | 30-300 nm | Glutaraldehyde [25] |

| Ionic Gelation | Mild conditions; simple process | 100-500 nm | Tripolyphosphate (TPP) [25] |

| Co-precipitation | Direct magnetization; high efficiency | 50-200 nm | Fe₃O₄, Fe₂O₃, MFe₂O₄ (M = Mn, Cu, Zn, Co) [9] [4] |

| Reverse Micelle | Narrow size distribution | 30-100 nm | Sodium bis(ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate [25] |

Protocol 1: Co-precipitation Synthesis of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

Materials:

- Chitosan (medium molecular weight, 75-85% deacetylation)

- Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6H₂O) and ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl₂·4H₂O)

- Ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH, 25-28%)

- Acetic acid (glacial, 99-100%)

- Tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution (1.0 mg/mL)

- Deionized water and nitrogen gas

Procedure:

- Chitosan Solution Preparation: Dissolve 1.0 g of chitosan in 100 mL of aqueous acetic acid solution (1% v/v) with continuous stirring for 4 hours at room temperature until complete dissolution.

- Iron Solution Preparation: Prepare a mixture of FeCl₃·6H₂O (2.4 g) and FeCl₂·4H₂O (1.0 g) in 50 mL deionized water under nitrogen atmosphere with vigorous stirring.

- Co-precipitation: Gradually add 15 mL of ammonium hydroxide to the iron solution over 30 minutes while maintaining pH at 10-11 and temperature at 60°C.

- Magnetite Formation: Continue stirring for 1 hour until black magnetite (Fe₃O₄) precipitates form.

- Chitosan Incorporation: Slowly add the chitosan solution to the magnetite suspension and maintain at 60°C for 2 hours with continuous stirring.

- Cross-linking: Add 50 mL of TPP solution dropwise to form stable nanoparticles.

- Separation and Washing: Recover nanoparticles using an external magnet and wash repeatedly with deionized water until neutral pH.

- Drying: Lyophilize the nanoparticles for 24 hours to obtain dry powder [9] [4] [25].

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain nitrogen atmosphere throughout to prevent oxidation of Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺

- Control precipitation rate to ensure uniform nanoparticle size

- Optimize chitosan-to-magnetite ratio for maximum adsorption capacity and magnetic responsiveness

Surface Modification for Enhanced Heavy Metal Removal

Surface modification of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles significantly enhances their selectivity and adsorption capacity for specific heavy metals.

Protocol 2: Thiol-Functionalization of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

Materials:

- Synthesized magnetic chitosan nanoparticles (from Protocol 1)

- Thioglycolic acid (TGA) or 2-mercaptosuccinic acid

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)

- N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Ethanol and deionized water

Procedure:

- Activation: Disperse 1.0 g of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles in 50 mL of deionized water.

- Cross-linker Addition: Add EDC (0.5 g) and NHS (0.3 g) to the suspension and stir for 30 minutes at room temperature to activate carboxylic groups.

- Thiol Incorporation: Add 1.0 mL of thioglycolic acid dropwise and maintain the reaction at 40°C for 6 hours with continuous stirring.

- Purification: Separate thiol-functionalized nanoparticles using an external magnet and wash repeatedly with ethanol-water mixture (1:1 v/v).

- Drying: Lyophilize for 24 hours and store in airtight containers [4] [25].

Characterization:

- Confirm thiol functionalization using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) peaks at 2570 cm⁻¹ (S-H stretch)

- Quantify thiol group density using Ellman's reagent assay

- Verify magnetic properties using vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM)

Synthesis workflow for magnetic chitosan nanoparticles

Adsorption Performance and Mechanism Analysis

The adsorption performance of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles varies significantly based on their structural characteristics and the specific heavy metal targeted.

Table 4: Adsorption Performance of MCBMs for Various Heavy Metals

| Heavy Metal | Adsorption Mechanisms | Key Influencing Factors | Reported Adsorption Capacity Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) | Ion exchange, coordination, electrostatic interaction | pH, competing ions, surface functionalization | High (Varies with modification) [9] |

| Cr(VI) | Reduction to Cr(III) followed by adsorption, electrostatic attraction | pH, redox potential, surface charge | Medium to High [9] |

| Cd(II) | Coordination, ion exchange, complexation | pH, ionic strength, amino group density | Medium [9] [4] |

| Hg(II) | Complexation, chelation, electrostatic interaction | pH, thiol functionalization, chloride ions | High (especially with thiol modification) [9] |

| Cu(II) | Coordination, chelation, ion exchange | pH, amine group availability, competing ions | Medium to High [9] |

Protocol 3: Batch Adsorption Experiments for Heavy Metal Removal

Materials:

- Synthesized magnetic chitosan nanoparticles (MCBMs)

- Standard heavy metal solutions (1000 mg/L)

- pH meter and buffer solutions

- Orbital shaker or temperature-controlled agitator

- Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer or ICP-MS

Procedure:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare heavy metal stock solutions at 1000 mg/L using analytical grade salts.

- Experimental Setup: Add 0.05 g of MCBMs to 50 mL of heavy metal solution at desired concentration in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks.

- pH Adjustment: Adjust pH to predetermined value (typically 2-7) using 0.1M HNO₃ or NaOH.

- Agitation: Agitate the mixture at constant temperature (25±1°C) at 150 rpm for specified contact time.

- Sampling: Withdraw samples at predetermined time intervals and separate nanoparticles using external magnet.

- Analysis: Measure residual heavy metal concentration in supernatant using AAS or ICP-MS.

- Calculation: Calculate adsorption capacity using the formula: [ qe = \frac{(C0 - Ce) \times V}{m} ] where ( qe ) = adsorption capacity (mg/g), ( C0 ) = initial concentration (mg/L), ( Ce ) = equilibrium concentration (mg/L), V = solution volume (L), m = adsorbent mass (g) [9] [4] [25].

Optimization Parameters:

- Contact time (5 minutes to 24 hours)

- Initial metal concentration (10-500 mg/L)

- pH (2.0-7.0)

- Temperature (25-45°C)

- Adsorbent dosage (0.2-2.0 g/L)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for MCBM Development and Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Primary biopolymer matrix | Degree of deacetylation >75%, medium molecular weight [16] [25] |

| Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles | Magnetic core component | Particle size <50 nm, superparamagnetic behavior [9] [4] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent | 25% aqueous solution, molecular biology grade [25] |

| Tripolyphosphate (TPP) | Ionic cross-linker | ≥99% purity, for nanoparticle stabilization [25] |

| Thioglycolic Acid | Thiol functionalization | ≥98% purity, for enhanced Hg adsorption [4] [25] |

| EDC/NHS | Carboxyl group activation | ≥98% purity, for covalent conjugation [25] |

Adsorption mechanisms of heavy metals on MCBMs

Regeneration and Reusability Protocols

The economic viability and practical application of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles depend significantly on their regeneration capacity and reusability.

Protocol 4: Regeneration of Spent Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

Materials:

- Metal-loaded magnetic chitosan nanoparticles

- Eluent solutions (acidic, basic, or chelating)

- Deionized water

- pH meter

Procedure:

- Eluent Selection: Choose appropriate eluent based on heavy metal type:

- Acidic eluent (0.1M HNO₃ or HCl) for most heavy metals

- Basic eluent (0.1M NaOH) for anionic metal species

- Chelating eluent (0.01M EDTA) for strong complexes

- Desorption: Add 0.1 g of metal-loaded nanoparticles to 50 mL of eluent solution.

- Agitation: Agitate at 150 rpm for 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Separation: Separate nanoparticles using external magnet and collect supernatant.

- Neutralization: Wash nanoparticles repeatedly with deionized water until neutral pH.

- Reactivation: If necessary, recondition nanoparticles in mild acid solution (0.001M acetic acid) to protonate amino groups.

- Drying: Air-dry or lyophilize for subsequent reuse [9] [4].

Performance Assessment:

- Monitor adsorption capacity retention over multiple cycles (typically 3-10 cycles)

- Evaluate structural integrity via SEM and FTIR after regeneration

- Assess magnetic separation efficiency after each cycle

Research indicates properly regenerated MCBMs can maintain 70-90% of initial adsorption capacity after 4-5 cycles, with performance reduction attributed to mass loss during regeneration and partial deactivation of functional groups [9].

The bibliometric analysis reveals several emerging frontiers in nano-chitosan research that warrant increased investigative attention:

- Advanced Material Architectures: Development of multi-functional composites with enhanced selectivity through molecular imprinting technologies [9]

- Process Optimization: Application of machine learning algorithms for predictive modeling of adsorption behavior and material optimization [9]

- Circular Economy Integration: Implementation of "close-loop" technologies for simultaneous heavy metal recovery and material regeneration [25]

- Scalability Solutions: Addressing challenges in large-scale production uniformity and economic viability [26]

The synthesis of bibliometric insights with experimental protocols presented in this analysis demonstrates the dynamic interplay between basic material research and applied environmental technology in the nano-chitosan domain. The continued evolution of this field remains contingent upon multidisciplinary collaboration, methodological standardization, and translational research bridging laboratory innovation with industrial implementation.

The removal of heavy metals from water using surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles (CMNPs) is a prominent research focus in environmental science and materials engineering. These bio-based adsorbents combine the excellent metal-binding properties of chitosan, a natural polysaccharide, with the facile magnetic separation capability of iron oxide nanoparticles [9]. The effectiveness of CMNPs hinges on three fundamental mechanisms: electrostatic interaction, chelation, and ion exchange [30]. Understanding these interactions at the molecular level is crucial for optimizing adsorbent design for specific metal ions and environmental conditions. This application note details experimental protocols and methodologies for investigating these core mechanisms, providing researchers with standardized approaches to characterize and quantify the underlying processes governing heavy metal removal.

Core Mechanisms and Experimental Analysis

Electrostatic Interaction

Electrostatic attraction occurs between charged functional groups on the CMNP surface (e.g., protonated amino groups) and dissolved metal ions [9]. The surface charge of the adsorbent, and consequently the electrostatic force, is highly dependent on the solution pH.

- 2.1.1 Protocol: Quantifying pH-Dependent Adsorption

- Objective: To determine the point of zero charge (PZC) of CMNPs and evaluate the effect of pH on adsorption efficiency via electrostatic forces.

- Materials:

- CMNP suspension (1 g/L)

- Heavy metal stock solution (e.g., 1000 mg/L Pb(II) or Cu(II))

- HNO3/NaOH solutions (0.1 M) for pH adjustment

- pH meter

- Thermostatic shaker

- Method:

- Prepare a series of 50 mL metal solutions (initial concentration: 50 mg/L) in conical flasks.

- Adjust the pH of each solution to a value between 3 and 9 using 0.1 M HNO3 or NaOH.

- Add a fixed dose of CMNPs (e.g., 0.5 g/L) to each flask.

- Agitate the flasks in a shaker at a constant speed and temperature (e.g., 150 rpm, 25°C) for 24 hours to ensure equilibrium.

- Measure the final pH and separate the CMNPs using an external magnet.

- Analyze the supernatant for residual metal concentration via Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES).

- Data Analysis: The pH corresponding to maximum adsorption is identified. The PZC can be determined separately using the solid addition method, where the final pH is plotted against the initial pH after equilibrating CMNPs in 0.01 M NaCl solutions.

Table 1: Exemplary Data for Pb(II) Adsorption on Chitosan-modified γ-Fe₂O₃ at Various pH Levels [31]

| Initial pH | Equilibrium pH | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Removal Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 24% |

| 5.0 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 56% |

| 7.0 | 7.1 | 4.45 | 89% |

| 9.0 | 8.8 | 3.9 | 78% |

The experimental workflow for studying pH-dependent electrostatic adsorption is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for pH-dependent adsorption.

Chelation

Chelation involves the formation of stable, ring-like coordination complexes between a metal ion and multiple donor atoms (e.g., N, O) from a single functional group. The iminodiacetic acid (IDA) functional group is a classic tridentate chelator, coordinating metals via its nitrogen and two oxygen atoms [32].

- 2.2.1 Protocol: Investigating Chelation using FT-IR and XPS

- Objective: To confirm chelation as a primary mechanism by identifying shifts in functional group vibrations and changes in elemental binding energies.

- Materials:

- CMNPs before and after metal loading

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectrometer

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS)

- FT-IR Method:

- Prepare dried samples of pure CMNPs and metal-loaded CMNPs (e.g., after exposure to Cu(II) solution).

- Analyze the samples using FT-IR spectroscopy in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹.

- Compare the spectra, focusing on the amine (-NH₂) and hydroxyl (-OH) stretching and bending regions.

- XPS Method:

- Mount dried samples on XPS stubs.

- Acquire high-resolution spectra for key elements: C 1s, O 1s, N 1s, and the target metal (e.g., Cu 2p).

- Analyze the binding energies (BEs) and potential shifts before and after metal complexation.

- Data Analysis: A shift in the -NH₂ or -OH vibration peaks in FT-IR indicates involvement in metal complexation [31]. In XPS, a change in the N 1s BE suggests coordination of the amino nitrogen to the metal, confirming chelation.

Table 2: Characteristic Spectral Shifts Indicative of Chelation [32] [31]

| Analytical Technique | Functional Group | Typical Wavenumber/BE (Pure CMNP) | After Metal Binding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | -NH₂ bending | ~1590 cm⁻¹ | Shift to lower wavenumber | Coordination of N to metal ion |

| FT-IR | -OH stretching | ~3400 cm⁻¹ | Broadening and shift | Involvement of O in coordination |

| XPS | N 1s | ~399.2 eV | Increase by ~0.5-1.0 eV | Electron donation from N to metal |

Ion Exchange

Ion exchange is a stoichiometric process where metal ions from solution are swapped with similarly charged ions (e.g., H⁺, Na⁺) initially bound to the adsorbent's functional groups. The fixed charge on the adsorbent's matrix facilitates this reversible process.

- 2.3.1 Protocol: Establishing Ion Exchange Stoichiometry

- Objective: To quantify the release of counter-ions (H⁺) during metal adsorption, providing evidence for an ion-exchange mechanism.

- Materials:

- CMNPs (H⁺-saturated form)

- Heavy metal stock solution (e.g., Pb(II))

- pH meter and ion chromatograph (IC)

- Thermostatic shaker

- Method:

- Pre-treat CMNPs with 0.1 M HNO₃, then wash with deionized water to achieve a H⁺-saturated form and neutral pH.

- Prepare 100 mL of metal solution (e.g., 50 mg/L Pb(II)) in a sealed vessel.

- Add a known dose of H⁺-saturated CMNPs.

- Continuously monitor the pH change over time or measure the final pH after equilibrium.

- Separate the CMNPs and analyze the supernatant for released H⁺ concentration via titration or IC.

- Data Analysis: The molar ratio of released H⁺ to adsorbed metal cation is calculated. A ratio of 2:1 (H⁺:M²⁺) strongly indicates an ion-exchange process is a dominant mechanism [33]. The relationship between different adsorption mechanisms and their key features is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Key features of adsorption mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CMNP Synthesis and Application

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (from shrimp/crab shells) | Bio-polymer matrix for CMNPs; provides amino/hydroxyl groups for metal binding [9] [30] | Degree of deacetylation >75%; medium molecular weight; soluble in dilute acetic acid |

| FeCl₂·4H₂O & FeCl₃ | Precursors for magnetic nanoparticle (Fe₃O₄/γ-Fe₂O₃) synthesis via co-precipitation [31] | Analytical grade; oxygen-free water recommended for Fe₃O₄ synthesis |

| Ammonia Solution (NH₄OH) | Precipitating agent for iron oxide formation during co-precipitation [31] | 25-28% concentration; acts as a base catalyst |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent for chitosan; enhances mechanical/chemical stability in acid [10] | 25% aqueous solution; can cross-link via Schiff base reaction with -NH₂ groups |

| Iminodiacetic Acid (IDA) | Functionalizing agent for introducing high-affinity chelating groups [32] | Tridentate chelator; selective for transition metals (Cu²⁺ > Ni²⁺ > Zn²⁺ > Co²⁺) |

| Acetic Acid (1% v/v) | Solvent for dissolving chitosan polymer [30] | Low concentration protonates -NH₂ groups, enabling chitosan solubility |

Integrated Workflow for Mechanism Elucidation

A comprehensive analysis of heavy metal removal by CMNPs requires the integration of multiple characterization techniques. The following protocol provides a holistic workflow.

- 4.1 Protocol: Multi-technique Mechanistic Study

- Objective: To synergistically employ batch adsorption, kinetics, and material characterization to identify the dominant adsorption mechanism(s).

- Materials: As per previous protocols (AAS/ICP-OES, FT-IR, XPS, pH meter).

- Method:

- Batch Equilibrium Studies: Conduct adsorption isotherm experiments (Langmuir, Freundlich) and kinetic studies (Pseudo-first order, Pseudo-second order) to quantify capacity and rate.

- Solution Analysis: Measure pH change and counter-ion release (H⁺) during adsorption.

- Material Characterization: Analyze pristine and metal-laden CMNPs using FT-IR, XPS, and XRD.

- Data Analysis: Correlate findings from all techniques. A strong fit to the Langmuir isotherm suggests monolayer adsorption. A good fit to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model often indicates chemisorption (e.g., chelation or ion exchange) [31]. FT-IR/XPS data confirms functional group involvement, while ion release data validates ion exchange.

Table 4: Interpreting Multi-technique Data for Mechanism Identification

| Observation | Possible Mechanism Indicated |

|---|---|

| High adsorption at pH > PZC of CMNP | Chelation specific to metal ion speciation |

| Molar ratio of H⁺ released / Metal adsorbed ≈ 2 (for M²⁺) | Cation exchange as dominant mechanism |

| Shift in FT-IR peaks for -NH₂ and -OH groups | Coordination/chelation of metal ions |

| Change in N 1s binding energy in XPS | Electron transfer via chelation |

| Adsorption capacity decreases with high competing ions (e.g., Na⁺, Ca²⁺) | Evidence of ion exchange and electrostatic interaction |

Synthesis, Modification, and Targeted Metal Ion Removal

The development of surface-modified chitosan magnetic nanoparticles (M-Ch-NPs) for heavy metal removal from water relies on precise synthetic control to tailor the material's adsorption capacity, magnetic responsiveness, and stability. The selection of a synthesis method directly influences critical nanoparticle properties, including crystallinity, size distribution, surface functionality, and magnetic saturation. This document details three core synthesis techniques—co-precipitation, crosslinking, and hydrothermal synthesis—within the context of preparing advanced nano-sorbents for water remediation. These methods enable the integration of superparamagnetic iron oxide cores (e.g., magnetite (Fe₃O₄) or maghemite (γ-Fe₂O₃)) with the versatile biopolymer chitosan, creating a composite material that combines excellent heavy metal uptake with facile magnetic separation from treated water [34] [4].

Synthesis Methodologies: Principles and Protocols

Co-precipitation Method

The co-precipitation method is one of the most widely used, cost-effective, and scalable approaches for synthesizing magnetic nanoparticles and their chitosan composites [35] [34]. This technique involves the simultaneous precipitation of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions in an aqueous alkaline solution to form magnetic iron oxides, which can be integrated with chitosan in a single pot (in-situ) or in a sequential process (two-step).

Table 1: Key Variations in Co-precipitation Synthesis for M-Ch-NPs

| Variation | Description | Key Features | Typical Chitosan Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-situ Co-precipitation | Chitosan is dissolved in the aqueous solution containing the Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ salt precursors before the base is added [4]. | - Single-pot synthesis.- Direct coating during NP formation.- Potentially more homogeneous polymer distribution. | Chitosan acts as a stabilizer during precipitation, leading to immediate functionalization. |

| Two-step Co-precipitation | Magnetic nanoparticles are synthesized first, purified, and then dispersed in a chitosan solution for surface decoration [36]. | - Better control over magnetic core properties.- Allows for separate optimization of core and shell.- More complex procedure. | Chitosan is adsorbed or cross-linked onto pre-formed NPs in a subsequent step. |

Experimental Protocol: In-situ Co-precipitation of Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

This protocol is adapted from procedures described for the fast preparation of magnetite and its functionalization with biopolymers like chitosan [35] [34] [36].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Iron Salts: Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6H₂O) and Ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl₂·4H₂O).

- Chitosan (CS): Medium molecular weight, degree of deacetylation >75%.

- Precipitation Agent: Ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH, 25-28%) or Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 0.5-1 M).

- Solvent: Deionized water.

- Dispersant/Anti-agglomeration Agent: Acetic acid (for dissolving chitosan).

- Inert Gas: Nitrogen (N₂) or Argon for purging.

II. Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.5 g of chitosan in 100 mL of deionized water containing 1% (v/v) acetic acid. Stir until completely dissolved.

- Iron Salt Addition: Under a constant N₂ purge and vigorous mechanical stirring (500-1000 rpm), add 2.0 mmol of FeCl₃·6H₂O and 1.0 mmol of FeCl₂·4H₂O to the chitosan solution. Maintain the temperature at 25-30°C. The N₂ atmosphere is crucial to prevent oxidation of Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ [35].

- Precipitation: Raise the temperature to 60-80°C. Slowly add the precipitation agent (e.g., NH₄OH) dropwise until the solution pH reaches 10-11. A black precipitate of magnetite will form instantly.

- Maturation: Continue stirring for 60-90 minutes at 60-80°C under N₂ to allow for complete particle growth.

- Sepection and Washing: Separate the black magnetic chitosan nanoparticles using a laboratory magnet. Decant the supernatant and wash the particles 3-4 times with deionized water and ethanol until the washings are neutral (pH ~7).

- Drying: Dry the resulting M-Ch-NPs in a vacuum oven at 50-60°C for 12-24 hours. Alternatively, they can be stored as an aqueous suspension.

III. Critical Parameters

- Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ Molar Ratio: A stoichiometric ratio of 1:2 is essential for pure magnetite formation [34].

- pH: A pH of 10-11 is critical for complete precipitation of the iron oxides.

- Temperature: Higher reaction temperatures (e.g., 80°C) generally improve crystallinity [35].

- Chitosan Concentration: Affects the thickness of the chitosan shell and the final particle size.

Crosslinking Method

Crosslinking is not typically a standalone method for creating the magnetic core but is a crucial secondary step to stabilize the chitosan shell and enhance the mechanical and chemical robustness of the M-Ch-NPs. It involves forming covalent bonds between chitosan chains using a crosslinking agent, which prevents the polymer from dissolving in acidic media and improves reusability [36] [25].

Experimental Protocol: Glutaraldehyde Crosslinking of Pre-formed M-Ch-NPs

This protocol follows a two-step approach where magnetic nanoparticles are first synthesized (e.g., via co-precipitation) and then crosslinked with chitosan.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Pre-formed Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesized via co-precipitation or obtained commercially.

- Chitosan (CS): Low or medium molecular weight.

- Crosslinking Agent: Glutaraldehyde (GA, 25% aqueous solution).

- Solvent: Acetic acid solution (1% v/v) and deionized water.

II. Procedure

- Chitosan Solution: Dissolve 0.5 g of chitosan in 100 mL of 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution.

- M-Ch-NP Dispersion: Disperse 1.0 g of pre-formed magnetic nanoparticles into the chitosan solution. Sonicate for 15-30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Crosslinking: Under constant mechanical stirring, add glutaraldehyde dropwise to the dispersion to a final concentration of 0.5-2.0% (v/v). The reaction typically proceeds for 2-4 hours at room temperature.

- Quenching and Washing: To stop the reaction, add a few drops of a glycine solution to quench unreacted glutaraldehyde. Separate the crosslinked M-Ch-NPs magnetically and wash thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol to remove any unreacted reagents.

- Drying: Dry the final product in a vacuum oven at 50°C.

III. Critical Parameters

- Crosslinker Concentration: Higher concentrations lead to a more rigid and dense polymer network but may block active adsorption sites (-NH₂ groups) [36].

- Reaction Time: Longer times ensure more complete crosslinking but must be optimized to avoid excessive reduction in active sites.

- pH: The reaction is most efficient in slightly acidic conditions where chitosan's amine groups are protonated.

Hydrothermal Synthesis

Hydrothermal synthesis involves conducting chemical reactions in a sealed vessel (autoclave) at elevated temperature and pressure. This method facilitates the crystallization of nanoparticles under precisely controlled conditions, typically resulting in products with high crystallinity, uniform morphology, and excellent thermal stability [37]. While less common for pure M-Ch-NPs, it is highly effective for synthesizing the magnetic component or complex nanocomposites.

Experimental Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Modified Nanotubes (Analogous to M-Ch-NP Synthesis)

This protocol is inspired by the hydrothermal modification of Halloysite nanotubes with metal nanoparticles, illustrating the principles applicable to functionalizing magnetic materials [37].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Magnetic Substrate: Pre-synthesized magnetic nanoparticles or a composite precursor.

- Chitosan Solution: Chitosan dissolved in dilute acetic acid.

- Modifying Agents: As required by the target composite (e.g., metal salts for doping).

- Autoclave: Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave.

II. Procedure

- Precursor Mixing: Combine the magnetic nanoparticle suspension, chitosan solution, and any other modifying agents in the Teflon liner of the autoclave. Stir the mixture thoroughly.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Seal the autoclave and place it in a preheated oven. The typical reaction conditions range from 120-200°C for 6-24 hours. The high temperature and autogenous pressure promote dissolution and recrystallization.

- Cooling and Collection: After the reaction time, remove the autoclave from the oven and allow it to cool naturally to room temperature.

- Washing and Drying: Collect the solid product by magnetic separation or centrifugation. Wash repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol. Dry the final product at 60-80°C.

III. Critical Parameters

- Temperature and Time: Directly control the crystallite size, phase purity, and morphology of the product.

- Fill Factor: The volume of the reaction mixture in the Teflon liner (typically 70-80%) affects the internal pressure.

- Precursor Concentration and pH: Influence nucleation and growth kinetics.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Methods

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Core Synthesis Methods for M-Ch-NPs

| Parameter | Co-precipitation | Crosslinking (as a secondary step) | Hydrothermal Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Simultaneous precipitation of ions in solution [35]. | Covalent bonding between polymer chains [36]. | Crystallization from solution at high T and P [37]. |

| Complexity & Cost | Low; simple equipment, aqueous-based [34]. | Low to Moderate. | High; requires specialized autoclave equipment. |

| Scalability | Excellent; easily scalable for industrial production [34]. | Good. | Moderate; limited by autoclave size and safety. |

| Typical Particle Size | 10-50 nm, but can be polydisperse [34]. | N/A (modifies shell of existing NPs). | 20-200 nm; often more monodisperse. |

| Crystallinity | Moderate; may require post-annealing [35]. | N/A. | High; direct formation of well-crystallized phases. |

| Key Advantages | - Fast and economical.- High yield.- Amenable to in-situ functionalization. | - Enhances chemical/mechanical stability.- Prevents chitosan dissolution in acid.- Improves reusability. | - Superior control over morphology & size.- High product purity and crystallinity. |

| Key Limitations | - Control over size distribution can be challenging.- May require oxygen exclusion. | - Can reduce the number of active adsorption sites. | - Long synthesis time.- High energy input.- Safety concerns with high pressure. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Synthesizing Magnetic Chitosan Nanoparticles

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Iron Precursors | FeCl₂·4H₂O, FeCl₃·6H₂O, FeSO₄·7H₂O [34] [36] | Source of Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ ions for the formation of magnetic iron oxide cores (e.g., Fe₃O₄, γ-Fe₂O₃). |

| Biopolymer | Chitosan (varying molecular weights and deacetylation degrees) [36] [4] | Provides a biocompatible, adsorbent shell functionalized with -NH₂ and -OH groups for heavy metal binding and nanoparticle stabilization. |

| Precipitation Agents | NH₄OH (ammonia), NaOH (sodium hydroxide) [35] [34] | Increases pH to initiate the precipitation and co-precipitation of metal hydroxides/oxides. |

| Crosslinking Agents | Glutaraldehyde (GA), Pentaethylenehexamine (PEHA), Tripolyphosphate (TPP) [36] [25] | Forms covalent or ionic bonds between chitosan chains, enhancing the stability and mechanical strength of the composite. |

| Surfactants & Dispersants | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [35] [38] | Controls particle growth and agglomeration during synthesis, leading to smaller and more monodisperse nanoparticles. |

| Solvents & Acids | Deionized Water, Acetic Acid [36] | Solvent medium and agent for dissolving chitosan via protonation of amine groups. |