Validating Chemical Knowledge in Large Language Models: Expert Benchmarks, Safety Protocols, and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies and frameworks for validating the chemical knowledge and reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) against expert-level benchmarks.

Validating Chemical Knowledge in Large Language Models: Expert Benchmarks, Safety Protocols, and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies and frameworks for validating the chemical knowledge and reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) against expert-level benchmarks. It explores the foundational need for structured data extraction in chemistry, examines advanced applications like autonomous synthesis and reaction optimization, addresses critical challenges such as safety risks and model hallucinations, and presents rigorous comparative evaluations against human expert performance. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence to guide the safe and effective integration of LLMs into chemical research and development workflows.

The Data Dilemma: Why Chemical Knowledge Extraction Demands Advanced LLMs

The Unstructured Data Challenge in Chemical Literature

Chemical research generates a vast and continuous stream of unstructured data, with over 5 million scientific articles published in 2022 alone [1]. This information is predominantly stored and communicated through complex formats including dense text, symbolic notations, molecular structures, spectral images, and heterogeneous tables within scientific publications [2] [3]. Unlike structured databases, this unstructured corpus represents a significant challenge for both human researchers and computational systems attempting to extract and synthesize knowledge. Large language models (LLMs) have emerged as potential tools to navigate this data deluge, capable of processing natural language and performing tasks beyond their explicit training [2]. However, their effectiveness in the chemically specific, precise, and safety-critical domain requires rigorous validation against expert benchmarks to measure true understanding versus superficial pattern recognition [2] [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various LLM approaches against these benchmarks, providing the experimental data and methodologies needed for researchers to assess their utility in real-world chemical research and drug development.

Benchmarking LLM Performance on Chemical Tasks

Systematic evaluation through specialized benchmarks is crucial for assessing the chemical capabilities of LLMs. The following section compares model performance across key benchmarks, detailing the experimental protocols used to generate the data.

Comparative Performance on Chemical Reasoning and Knowledge

Table 1: Performance Comparison of LLMs on General Chemical Knowledge and Reasoning Benchmarks

| Benchmark Name | Core Focus | Model Type / Name | Key Performance Metric | Human Expert Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Broad chemical knowledge & reasoning | Best Performing Models (Overall) | Outperformed best human chemists in the study (average score) | Surpassed human experts |

| Leading Open & Closed-Source Models | Struggled with some basic tasks; provided overconfident predictions | Variable by task | ||

| ChemIQ [5] | Molecular comprehension & chemical reasoning | OpenAI o3-mini (High Reasoning) | 59% accuracy (796 questions) | Not specified |

| OpenAI o3-mini (Lower Reasoning) | 28% accuracy (796 questions) | Not specified | ||

| GPT-4o (Non-reasoning) | 7% accuracy (796 questions) | Not specified |

Performance on Specialized Chemical Data Extraction Tasks

Table 2: Performance Comparison of LLMs on Specialized Data Extraction Tasks

| Benchmark Name | Data Type | Model Type / Name | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemTable [3] | Chemical Table Recognition | Open-source MLLMs | Reasonable performance on basic layout parsing |

| Closed-source MLLMs | Substantial limitations on descriptive & inferential QA vs. humans | ||

| -/- | Scientific Figure Decoding | State-of-the-art LLMs | Show potential but have significant limitations in data extraction [6] |

| -/- | Citation & Reference Generation | ChatGPT (GPT-3.5) | 72.7% citation existence in natural sciences; 32.7% DOI accuracy [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarks

The quantitative data presented in the comparison tables were generated through the following standardized experimental methodologies:

ChemBench Evaluation Protocol [2]: The benchmark corpus consists of 2,788 question-answer pairs (2,544 multiple-choice, 244 open-ended) curated from diverse sources, including manually crafted questions and university exams. Topics range from general chemistry to specialized fields, classified by required skill (knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition) and difficulty. For contextualization, 19 chemistry experts were surveyed on a 236-question subset (ChemBench-Mini). Models were evaluated based on text completions, accommodating black-box and tool-augmented systems. Special semantic encoding for scientific information (e.g., SMILES tags) was used where supported.

ChemIQ Evaluation Protocol [5]: This benchmark comprises 796 algorithmically generated short-answer questions to prevent solution by elimination. It focuses on three core competencies: 1) Interpreting molecular structures (e.g., counting atoms, identifying shortest bond paths), 2) Translating structures to concepts (e.g., SMILES to validated IUPAC names), and 3) Chemical reasoning (e.g., predicting Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and reaction products). Evaluation is based on the accuracy of the model's direct, self-constructed answers.

ChemTable Evaluation Protocol [3]: This benchmark assesses multimodal capabilities on over 1,300 real-world chemical tables from top-tier journals. The Recognition Task involves structure parsing and content extraction from table images into structured data. The Understanding Task involves over 9,000 descriptive and reasoning question-answering instances grounded in table structure and domain semantics (e.g., comparing yields, attributing results to conditions). Performance is automatically graded against short-form answers.

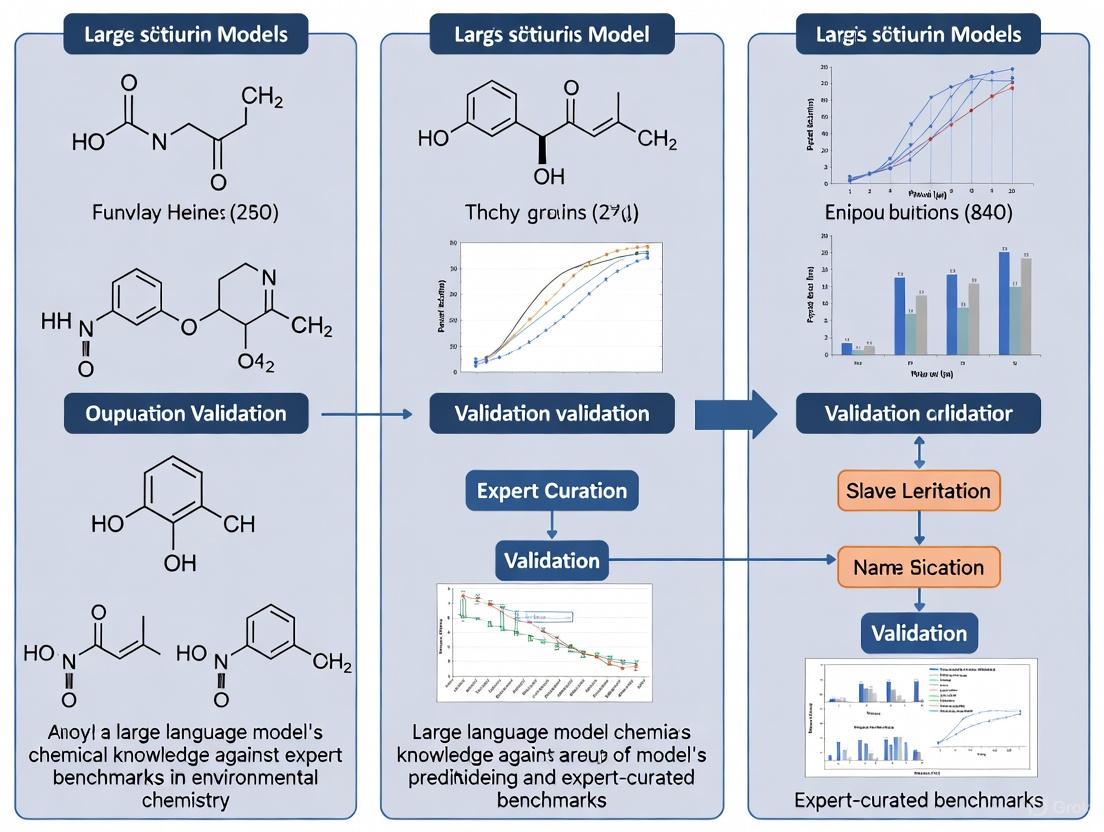

Methodological Workflow for Benchmarking LLMs in Chemistry

The process of validating the chemical knowledge of an LLM against expert benchmarks follows a structured workflow from data curation to final performance scoring. The diagram below outlines the key stages of this methodology, as derived from the experimental protocols of major benchmarks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for LLM Evaluation

Building and evaluating LLMs for chemistry requires a suite of specialized "research reagents"—datasets, benchmarks, and software tools. The table below details essential components for constructing a robust evaluation framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LLM Evaluation in Chemistry

| Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| ChemBench Corpus [2] | Benchmark Dataset | Provides a comprehensive set of >2,700 questions to evaluate broad chemical knowledge and reasoning against human expert performance. |

| ChemIQ Benchmark [5] | Benchmark Dataset | Tests core understanding of organic molecules and chemical reasoning through algorithmically generated short-answer questions. |

| ChemTable Dataset [3] | Benchmark Dataset | Evaluates multimodal LLMs' ability to recognize and understand complex information encoded in real-world chemical tables. |

| SMILES Strings [5] | Molecular Representation | Standard text-based notation for representing molecular structures; the primary input for testing molecular comprehension. |

| OPSIN Tool [5] | Validation Software | Parses systematic IUPAC names to validate the correctness of LLM-generated chemical nomenclature, allowing for non-standard yet valid names. |

| CHEERS Checklist [7] | Reporting Guideline | Serves as a structured framework for evaluating the quality and completeness of health economic studies, demonstrating LLMs' ability to assess research quality. |

Critical Analysis of LLM Capabilities and Limitations

Synthesizing the performance data from these benchmarks reveals a nuanced landscape of LLM capabilities in chemistry. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different LLM system architectures and their associated capabilities and risks, highlighting the path toward more reliable chemical AI.

The data indicates that reasoning models, such as OpenAI's o3-mini, represent a significant leap in autonomous chemical reasoning, dramatically outperforming non-reasoning predecessors like GPT-4o on specialized tasks [5]. Furthermore, the best models can now match or even surpass the average performance of human chemists on broad knowledge benchmarks [2]. However, this strong performance is contextualized by critical limitations. Even high-performing models struggle with basic tasks and exhibit overconfident predictions [2]. A particularly serious constraint is the widespread issue of hallucination, where models generate plausible but incorrect or entirely fabricated information, such as non-existent scientific citations [1] or unsafe chemical procedures [4].

The distinction between "passive" and "active" LLM environments is crucial for real-world application [4]. Passive LLMs, which rely solely on their pre-trained knowledge, are prone to hallucination and providing outdated information. In contrast, active LLM systems are augmented with external tools—such as access to current literature, chemical databases, property calculation software, and even laboratory instrumentation. This architecture grounds the LLM's responses in reality, transforming it from an oracle-like knowledge source into a powerful orchestrator of integrated research workflows [4]. This capability is exemplified by systems like Coscientist, which can autonomously plan and execute complex experiments [4]. The progression towards active, tool-augmented, and reasoning-driven models points the way forward for developing reliable LLM partners in chemical research.

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into chemistry promises to transform how researchers extract knowledge from the vast body of unstructured scientific literature. With most chemical information stored as text rather than structured data, LLMs offer potential for accelerating discovery in molecular design, property prediction, and synthesis optimization [8] [9]. However, this promise depends on a critical foundation: rigorously validating LLMs' chemical knowledge against expert-defined benchmarks. Without standardized evaluation, claims about model capabilities remain anecdotal rather than scientific [2].

The development of comprehensive benchmarking frameworks has emerged as a research priority to quantitatively assess whether LLMs truly understand chemical principles or merely mimic patterns in their training data. Recent studies reveal a complex landscape where the best models can outperform human chemists on certain tasks while struggling with fundamental concepts in others [2] [10]. This comparison guide examines the current state of chemical LLM validation through the lens of recently established benchmarks, experimental protocols, and performance metrics—providing researchers with actionable insights for evaluating these rapidly evolving tools.

Major Benchmarking Frameworks for Chemical LLMs

ChemBench: A Comprehensive Evaluation Framework

ChemBench represents one of the most extensive frameworks for evaluating the chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities of LLMs. This automated evaluation system was specifically designed to assess capabilities across the breadth of chemistry domains taught in undergraduate and graduate curricula [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset Composition: The benchmark comprises 2,788 question-answer pairs curated from diverse sources, including manually crafted questions, university examinations, and semi-automatically generated questions from chemical databases [2].

- Question Types: The corpus includes both multiple-choice (2,544 questions) and open-ended questions (244 questions) to reflect the reality of chemical education and research beyond simple recognition tasks [2].

- Skill Assessment: Questions are classified by required skills (knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition) and difficulty levels, enabling nuanced analysis of model capabilities [2].

- Specialized Processing: The framework implements special encoding for chemical notation (e.g., SMILES strings enclosed in [STARTSMILES][ENDSMILES] tags) to accommodate scientific information [2].

- Human Baseline: Performance is contextualized against 19 chemistry experts who answered a subset of questions, some with tool access like web search [2].

ChemIQ: Assessing Molecular Comprehension

The ChemIQ benchmark takes a specialized approach focused specifically on molecular comprehension and chemical reasoning within organic chemistry [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset Composition: 796 algorithmically generated questions focused on three core competencies: interpreting molecular structures, translating structures to chemical concepts, and reasoning about molecules using chemical theory [5].

- Question Format: Exclusively uses short-answer responses rather than multiple choice, requiring models to construct solutions rather than select from options [5].

- Molecular Representation: Utilizes Simplified Molecular Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings to represent molecules, testing model ability to work with standard cheminformatics notation [5].

- Task Variety: Includes unique tasks like atom mapping between different SMILES representations of the same molecule and structure-activity relationship analysis [5].

AMORE: Evaluating Robustness to Molecular Representations

The AMORE (Augmented Molecular Retrieval) framework addresses a critical aspect of chemical understanding: robustness to different representations of the same molecule [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Core Concept: Tests whether models recognize different SMILES strings representing the same chemical structure as equivalent [11].

- Methodology: Generates multiple valid SMILES variations for each molecule through permutations like randomized atom orderings, then measures embedding similarity between these variants [11].

- Evaluation Metric: Assesses consistency of internal model representations across SMILES variations, with robust models expected to produce similar embeddings for chemically identical structures [11].

PharmaBench: ADMET-Specific Benchmarking

PharmaBench addresses the crucial domain of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties in drug development [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Integrates data from multiple sources including ChEMBL database and public datasets, comprising 156,618 raw entries processed down to 52,482 curated entries [12].

- LLM-Powered Curation: Employs a multi-agent LLM system to extract experimental conditions from unstructured assay descriptions in scientific literature [12].

- Standardization: Implements rigorous filtering based on drug-likeness, experimental values, and conditions to ensure dataset quality and consistency [12].

Table 1: Overview of Major Chemical LLM Benchmarking Frameworks

| Benchmark | Scope | Question Types | Key Metrics | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench | Comprehensive chemistry knowledge | Multiple choice, open-ended | Accuracy across topics and skills | 2,788 questions |

| ChemIQ | Molecular comprehension & reasoning | Short-answer | Accuracy on structure interpretation | 796 questions |

| AMORE | Robustness to molecular representations | Embedding similarity | Consistency across SMILES variations | Flexible |

| PharmaBench | ADMET properties | Structured prediction | Predictive accuracy on pharmacokinetics | 52,482 entries |

Performance Comparison: LLMs vs. Human Expertise

Recent evaluations reveal significant variations in LLM performance across chemical domains. On ChemBench, the best-performing models surprisingly outperformed the best human chemists involved in the study on average across all questions [2]. However, this overall performance masks important nuances and limitations.

Table 2: Comparative Performance on Chemical Reasoning Tasks

| Model Type | Overall Accuracy (ChemBench) | Molecular Reasoning (ChemIQ) | SMILES Robustness (AMORE) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leading Proprietary LLMs | ~80-85% (outperforming humans) [2] | 28-59% (varies by reasoning level) [5] | Limited consistency across representations [11] | Broad knowledge, complex reasoning |

| Specialized Chemistry Models | Lower than general models (e.g., Galactica near random) [10] | Not reported | Moderate performance | Domain-specific pretraining |

| Human Experts | ~40% (average) to ~80% (best) [2] | Baseline for comparison | Native understanding | Chemical intuition, safety knowledge |

| Tool-Augmented LLMs | Mediocre (limited by API call constraints) [10] | Not reported | Not applicable | Access to external knowledge |

Domain-Specific Performance Variations

Spider chart analysis of model performance across chemical subdomains reveals significant variations. While many models perform relatively well in polymer chemistry and biochemistry, they show notable weaknesses in chemical safety and some fundamental tasks [10]. The models provide overconfident predictions on questions they answer incorrectly, presenting potential safety risks for non-expert users [2].

Reasoning-specific models like OpenAI's o3-mini demonstrate substantially improved performance on chemical tasks compared to non-reasoning models, with accuracy increasing from 28% to 59% depending on the reasoning level used [5]. This represents a dramatic improvement over previous models like GPT-4o, which achieved only 7% accuracy on the same ChemIQ benchmark [5].

Experimental Workflows for Chemical LLM Validation

Benchmarking Methodology

The validation of chemical LLMs follows rigorous experimental protocols to ensure meaningful, reproducible results. The workflow encompasses data collection, model evaluation, and performance analysis stages.

Chemical LLM Validation Workflow

Data Extraction and Curation Protocol

LLMs are increasingly used not just as end tools but as components in data extraction pipelines. The workflow for extracting structured chemical data from unstructured text demonstrates another dimension of chemical LLM validation [9].

Chemical Data Extraction Pipeline

Essential Research Reagents for Chemical LLM Validation

The experimental validation of chemical LLMs relies on specialized "research reagents" in the form of datasets, software tools, and evaluation frameworks. These resources enable standardized, reproducible assessment of model capabilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chemical LLM Validation

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in Validation | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench Corpus | Benchmark Dataset | Comprehensive evaluation across chemical subdomains | Open Source [2] |

| SMILES Augmentations | Data Transformation | Testing robustness to equivalent molecular representations | Algorithmically Generated [11] |

| PharmaBench ADMET Data | Specialized Dataset | Validating prediction of pharmacokinetic properties | Open Source [12] |

| OPSIN Parser | Software Tool | Validating correctness of generated IUPAC names | Open Source [5] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular representation and canonicalization | Open Source [12] |

| AMORE Framework | Evaluation Framework | Assessing embedding consistency across representations | Open Source [11] |

The systematic validation of LLMs against chemical expertise reveals both impressive capabilities and significant limitations. Current models demonstrate sufficient knowledge to outperform human experts on broad chemical assessments yet struggle with fundamental tasks and show concerning inconsistencies in molecular representation understanding [2] [11]. The emergence of reasoning models represents a substantial leap forward, particularly for tasks requiring multi-step chemical reasoning [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings suggest a cautious integration approach. LLMs show particular promise as assistants for data extraction from literature [9], initial hypothesis generation, and educational applications. However, their limitations in safety-critical applications and robustness to different molecular representations necessitate careful human oversight. The developing ecosystem of chemical benchmarks provides the necessary tools for ongoing evaluation as models continue to evolve, ensuring that progress is measured rigorously against meaningful expert-defined standards rather than anecdotal successes.

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into chemical research represents a paradigm shift, moving these tools from simple text generators to potential collaborators in scientific discovery. This transition necessitates rigorous evaluation frameworks to validate the chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities of LLMs against established expert benchmarks. The core chemical tasks of property prediction, synthesis planning, and reaction planning are critical areas where LLMs show promise but require systematic assessment. Recent research, including the development of frameworks like ChemBench and ChemIQ, has begun to quantify the capabilities and limitations of state-of-the-art models by testing them on carefully curated questions that span undergraduate and graduate chemistry curricula [2] [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various LLMs on these tasks, providing experimental data and methodologies that are essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand the current landscape of chemical AI.

Benchmarking Frameworks and Key Performance Metrics

To ensure a standardized and fair evaluation, researchers have developed specialized benchmarks that test the chemical intelligence of LLMs. The table below summarizes the core features of two prominent frameworks.

Table 1: Key Benchmarking Frameworks for Evaluating LLMs in Chemistry

| Benchmark Name | Scope & Question Count | Key Competencies Assessed | Question Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Broad chemical knowledge; 2,788 question-answer pairs | Reasoning, knowledge, intuition, and calculation across general and specialized chemistry topics [2] | Mix of multiple-choice (2,544) and open-ended (244) questions [2] |

| ChemIQ [5] | Focused on organic chemistry & molecular comprehension; 796 questions | Interpreting molecular structures, translating structures to concepts, and chemical reasoning [5] | Exclusively short-answer questions [5] |

These benchmarks are designed to move beyond simple knowledge recall. ChemIQ, for instance, requires models to construct short-answer responses, which more closely mirrors real-world problem-solving than selecting from multiple choices [5]. Both frameworks aim to provide a comprehensive view of model capabilities, from foundational knowledge to advanced reasoning.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The methodology for evaluating LLMs using these benchmarks follows a structured protocol to ensure consistency and reliability:

- Benchmark Curation and Validation: The process begins with the compilation of question-answer pairs from diverse sources, including manually crafted questions, university exams, and semi-automatically generated questions from chemical databases. A critical step is expert review; in the case of ChemBench, all questions were reviewed by at least two scientists in addition to the original curator to ensure quality and accuracy [2]. For specialized benchmarks like ChemIQ, questions are often algorithmically generated, which allows for systematic probing of model failure modes and helps prevent performance inflation from data leakage [5].

- Model Evaluation and Prompting: Benchmarks are designed to operate on text completions, making them compatible with a wide range of model types, including black-box systems and tool-augmented LLMs [2]. To enhance performance and reliability, specific prompting strategies are employed. The Hierarchical Reasoning Prompting (HRP) strategy, which mirrors the structured thinking process of human experts (e.g., problem decomposition, knowledge application, and validation), has been shown to notably improve model accuracy and consistency in specialized domains like engineering [13]. Furthermore, the use of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, where models are encouraged to show their intermediate reasoning steps, is a cornerstone of modern "reasoning models" and leads to significant performance gains [5].

- Performance Scoring and Analysis: For multiple-choice questions, standard accuracy metrics are used. For open-ended tasks, more nuanced scoring is required. For example, in the SMILES to IUPAC name conversion task, a generated name may be considered correct if it can be parsed to the intended molecular structure using a tool like OPSIN, rather than requiring an exact string match to a single "standard" name [5]. Performance is then analyzed across different topics (e.g., organic, analytical chemistry) and skill types (e.g., knowledge vs. reasoning) to identify model strengths and weaknesses.

Comparative Performance Analysis of LLMs on Core Tasks

Quantitative Performance Across Models and Tasks

Evaluations on the aforementioned benchmarks reveal significant disparities in the capabilities of different LLMs. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of LLMs on Core Chemical Tasks

| Model / System Type | Overall Accuracy (ChemBench) | Overall Accuracy (ChemIQ) | Key Task-Specific Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best Performing Models | On average, outperformed the best human chemists in the study [2] | 28% to 59% accuracy (OpenAI o3-mini, varies with reasoning effort) [5] | Can elucidate structures from NMR data (74% accuracy for ≤10 heavy atoms) [5] |

| Non-Reasoning Models (e.g., GPT-4o) | Not specified | ~7% accuracy [5] | Struggled with direct chemical reasoning tasks [5] |

| Human Chemists (Expert Benchmark) | Performance was surpassed by the best models on average [2] | Serves as the qualitative benchmark for reasoning processes [5] | The standard for accuracy and logical reasoning against which models are measured [2] |

The data shows that so-called "reasoning models," which are explicitly trained to optimize their chain-of-thought, substantially outperform previous-generation models. The best models not only surpass human expert performance on average on the broad ChemBench evaluation but also show emerging capabilities in complex tasks like structure elucidation from NMR data, a task that requires deep chemical intuition [2] [5].

Qualitative Analysis of Model Reasoning and Failure Modes

Beyond quantitative scores, a qualitative analysis of the model's reasoning process is crucial. Studies note that the reasoning steps of advanced models like o3-mini show similarities to the logical processes a human chemist would employ [5]. However, several critical limitations persist:

- Struggles with Basic Tasks: Despite their advanced capabilities, models can still struggle with some fundamental tasks, indicating that their knowledge base is not yet complete [2].

- Overconfidence: A commonly observed issue is that LLMs often provide predictions with a high degree of confidence that is not justified by their accuracy, which poses a significant risk for real-world applications [2] [13].

- Dependence on Reasoning Effort: The performance of reasoning models is not static; it is highly dependent on the computational "effort" or level of reasoning allocated to a problem, with higher levels leading to significantly improved accuracy [5].

Figure 1: The experimental workflow for validating the chemical knowledge of LLMs, showing the progression from problem definition through benchmarking and analysis to a final conclusion.

To conduct rigorous evaluations of LLMs in chemistry or to leverage these tools effectively, researchers should be familiar with the following key resources and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for LLM Evaluation in Chemistry

| Resource / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Evaluation Framework | Provides a broad, expert-validated corpus to test general chemical knowledge and reasoning. |

| ChemIQ [5] | Specialized Benchmark | Assesses focused competencies in molecular comprehension and organic chemical reasoning. |

| SMILES Strings [5] | Molecular Representation | Standard text-based format for representing molecular structures in prompts and outputs. |

| OPSIN Parser [5] | Validation Tool | Checks the correctness of generated IUPAC names by parsing them back to chemical structures. |

| Hierarchical Reasoning\nPrompting (HRP) [13] | Methodology | A prompting strategy that improves model reliability by enforcing a structured, human-like reasoning process. |

| ZINC Database [5] | Chemical Compound Database | Source of drug-like molecules used for algorithmically generating benchmark questions. |

Figure 2: A high-level overview of core chemical tasks, showing how a molecular input (e.g., a SMILES string) is processed by an LLM to address different problem types.

The experimental data from current benchmarking efforts paints a picture of rapid advancement. The best LLMs have reached a level where they can, on average, outperform human chemists on broad chemical knowledge tests and demonstrate tangible skill in specialized tasks like NMR structure elucidation [2] [5]. The advent of "reasoning models" has been a key driver, significantly boosting performance on tasks that require multi-step logic [5]. However, the path forward requires addressing critical challenges, including model overconfidence and inconsistencies on fundamental questions. The future of LLMs in chemistry will likely involve their integration as components within larger, tool-augmented systems, where their reasoning capabilities are combined with specialized software for simulation, database lookup, and synthesis planning. For researchers, this underscores the importance of continued rigorous benchmarking using frameworks like ChemBench and ChemIQ to measure progress, mitigate potential harms, and safely guide these powerful tools toward becoming truly useful collaborators in chemical research and drug development.

Foundation models are revolutionizing chemical research by adapting core capabilities to specialized tasks such as property prediction, molecular simulation, and reaction reasoning. These models, pre-trained on massive, diverse datasets, demonstrate remarkable adaptability through techniques like fine-tuning and prompt-based learning, achieving performance that sometimes rivals or even exceeds human expert knowledge in specific domains [14] [2]. The table below summarizes the primary model classes and their adapted applications in chemistry.

| Model Class | Core Architecture Examples | Primary Adaptation Methods | Key Chemical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Large Language Models (LLMs) | GPT-4, Claude, Gemini [15] | In-context learning, Chain-of-Thought prompting [2] [16] | Chemical knowledge Q&A, Literature analysis [2] |

| Chemical Language Models | SMILES-BERT, ChemBERTa, MoLFormer [14] | Fine-tuning on property labels, Masked language modeling [14] | Molecular property prediction, Toxicity assessment [14] |

| Geometric & 3D Graph Models | GIN, SchNet, Allegro, MACE [14] [17] | Graph contrastive learning, Energy decomposition (E3D), Supervised fine-tuning on energies/forces [14] [17] | Molecular property prediction, Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs), Reaction energy prediction [14] [17] |

| Generative & Inverse Design Models | Diffusion models, GP-MoLFormer [14] | Conditional generation, Guided decoding [14] | De novo molecule & crystal design, Lead optimization [14] |

Performance Benchmarking Against Expert Knowledge

Rigorous benchmarking is critical for validating the real-world utility of foundation models in chemistry. Specialized frameworks have been developed to quantitatively compare model performance against human expertise and established scientific ground truth.

Broad Chemical Knowledge and Reasoning

The ChemBench framework provides a comprehensive evaluation suite, pitting state-of-the-art LLMs against human chemists. Its findings offer a nuanced view of current capabilities and limitations [2].

- Evaluation Scope: ChemBench comprises over 2,700 question-answer pairs covering a wide range of topics from general chemistry to specialized sub-fields. It assesses not only factual knowledge but also reasoning, calculation, and chemical intuition [2].

- Key Finding: On average, the best-performing LLMs were found to outperform the best human chemists involved in the study. However, this superior average performance coexists with significant weaknesses, as models can struggle with fundamental tasks and produce overconfident yet incorrect predictions [2].

Specialized Mechanistic Reasoning

For the complex domain of organic reaction mechanisms, the oMeBench benchmark offers deep, fine-grained insights. It focuses on the step-by-step elementary reactions that form the "algorithm" of a chemical transformation [16].

- Evaluation Scope: oMeBench is a large-scale, expert-curated dataset of over 10,000 annotated mechanistic steps. It evaluates a model's ability to generate valid intermediates and maintain chemical consistency and logical coherence across multi-step pathways [16].

- Key Finding: While current LLMs demonstrate "non-trivial chemical intuition," they significantly struggle with correct and consistent multi-step reasoning. Performance can be substantially improved (by up to 50% over leading baselines) through exemplar-based in-context learning and supervised fine-tuning on specialized datasets, indicating a path forward for bridging this capability gap [16].

Quantitative Performance Table

The following table synthesizes key quantitative results from recent benchmark studies, providing a direct comparison of model performance across different chemical tasks.

| Benchmark / Task | Top Model(s) Performance | Human Expert Performance (for context) | Key Challenge / Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench (Overall) [2] | Best models outperform best humans (on average) | Outperformed by best models (on average) | Struggles with some basic tasks; overconfident predictions |

| oMeBench (Mechanistic Reasoning) [16] | Can be improved by 50% with specialized fine-tuning | Not explicitly stated | Multi-step causal logic, especially in lengthy/complex mechanisms |

| MLIPs (Reaction Energy, ΔE) [17] | MAE improves consistently with more data & model size (scaling) | N/A | N/A |

| MLIPs (Activation Barrier, Ea) [17] | MAE plateaus after initial improvement ("scaling wall") [17] | N/A | Learning transition states and reaction kinetics |

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of model assessments, benchmarks employ standardized evaluation protocols. Below are the detailed methodologies for two major types of evaluations.

The ChemBench Evaluation Workflow

ChemBench is designed to operate on text completions, making it suitable for evaluating black-box API-based models and tool-augmented systems, which reflects real-world application scenarios [2].

Detailed Methodology [2]:

- Corpus Curation: The benchmark corpus is compiled from diverse sources, including manually crafted questions, university exams, and semi-automatically generated questions from chemical databases. All questions are reviewed by at least two scientists.

- Semantic Annotation: Questions are stored in an annotated format, encoding the semantic meaning of chemical entities (e.g., SMILES strings, units, equations) using special tags (e.g.,

[START_SMILES]...[\END_SMILES]). This allows models to treat scientific information differently from natural language. - Text Completion & Scoring: Models are evaluated based on their final text completions. For multiple-choice questions, accuracy is measured. For open-ended questions, automated scoring aligns the model's reasoning and final answer with expert solutions.

- Human Baseline Contextualization: A subset of the benchmark (ChemBench-Mini) is answered by human chemistry experts, sometimes with tool access (e.g., web search). Model performance is directly compared to these human scores to contextualize the results.

The oMeBench Dynamic Scoring Framework

oMeBench introduces a dynamic and chemically-informed evaluation framework, oMeS, which goes beyond simple product prediction to measure the fidelity of entire mechanistic pathways [16].

Detailed Methodology [16]:

- Dataset Construction:

- oMe-Gold: A core set of literature-verified reactions with detailed, expert-curated mechanisms serving as the gold-standard benchmark.

- oMe-Template: Mechanistic templates with substitutable R-groups, abstracted from oMe-Gold to generalize reaction families.

- oMe-Silver: A large-scale dataset for training, automatically expanded from oMe-Template and filtered for chemical plausibility.

- Dynamic Scoring (oMeS):

- Mechanism Alignment: The framework first aligns the sequence of steps in the predicted mechanism with the gold-standard mechanism.

- Multi-Metric Evaluation: It then computes a final score based on a weighted combination of:

- Step-level Logic: The logical coherence and correctness of each mechanistic step (e.g., arrow-pushing, charge conservation).

- Chemical Similarity: The structural similarity of predicted intermediates to the ground-truth intermediates, often assessed via molecular fingerprints or graph-based metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Datasets

The development and validation of chemical foundation models rely on high-quality, large-scale datasets and specialized software frameworks. The table below lists essential "research reagents" in this field.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Evaluation Framework | Automatically evaluates the chemical knowledge and reasoning of LLMs. | 2,700+ expert-reviewed Q&As; compares model performance directly to human chemists. |

| oMeBench [16] | Benchmark Dataset & Metric | Evaluates organic reaction mechanism elucidation and reasoning. | 10,000+ annotated mechanistic steps; dynamic oMeS scoring for fine-grained analysis. |

| CARA [18] | Benchmark Dataset | Benchmarks compound activity prediction for real-world drug discovery. | Distinguishes between Virtual Screening (VS) and Lead Optimization (LO) assays; mimics real data distribution biases. |

| SPICE, MPtrj, OMat [17] | Training Datasets | Large-scale datasets for training Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs). | Contains molecular dynamics trajectories and material structures; enables scaling and emergent "chemical intuition" in MLIPs. |

| Allegro, MACE [14] [17] | Software / Model Architecture | E(3)-equivariant neural networks for building accurate MLIPs. | Respects physical symmetries; can learn chemically meaningful representations like Bond Dissociation Energies (BDEs) without direct supervision. |

| E3D Framework [17] | Analysis Tool | Mechanistically analyzes how MLIPs learn chemical concepts. | Decomposes potential energy into bond-wise contributions; reveals "scaling walls" and emergent representations. |

Foundation models are demonstrating impressive and sometimes surprising adaptability to chemical problems, with their emergent capabilities ranging from broad chemical knowledge recall to specialized tasks like predicting reaction energies and generating plausible molecular structures. However, benchmarking against expert knowledge reveals a landscape of both promise and limitation. While these models can achieve superhuman performance on certain measures, they continue to struggle with core scientific skills like robust, multi-step mechanistic reasoning and accurately predicting activation barriers. The future of these models in chemistry will likely hinge on strategic fine-tuning, the development of more sophisticated reasoning architectures, and continued rigorous evaluation against expert-curated benchmarks that reflect the complex, multi-faceted nature of real-world scientific discovery.

From Theory to Lab: Methodologies and Real-World LLM Applications in Chemistry

The integration of large language models (LLMs) into scientific domains has revealed a critical limitation: their inherent lack of specialized domain knowledge and propensity for generating inaccurate or hallucinated content. This is particularly problematic in chemistry, a field characterized by complex terminologies, precise calculations, and rapidly evolving knowledge. To address these challenges, researchers have developed a pioneering approach—tool augmentation. This methodology enhances LLMs by connecting them to expert-curated databases and specialized software, creating powerful AI agents capable of tackling sophisticated chemical tasks. The emergence of systems like ChemCrow represents a significant milestone in this evolution, demonstrating how LLMs can be transformed from general-purpose chatbots into reliable scientific assistants.

Tool-augmented LLMs operate on a simple but powerful principle: complement the LLM's reasoning and language capabilities with external tools that provide exact answers to domain-specific problems. This synergy allows the AI to access current information from chemical databases, perform complex calculations, predict molecular properties, and even plan and execute chemical syntheses. For chemistry researchers and drug development professionals, this integration bridges the gap between computational and experimental chemistry, offering unprecedented opportunities to accelerate discovery while maintaining scientific rigor. As these systems continue to evolve, understanding their capabilities, limitations, and optimal applications becomes essential for leveraging their full potential in research and development.

ChemCrow: Architecture and Core Capabilities

System Design and Workflow

ChemCrow operates as an LLM-powered chemistry engine that streamlines reasoning processes for diverse chemical tasks. Its architecture employs the ReAct framework (Reasoning-Acting), which guides the LLM through an iterative process of Thought, Action, Action Input, and Observation cycles [19]. This structured approach enables the model to reason about the current state of a task, plan next steps using appropriate tools, execute those actions, and observe the results before proceeding. The system uses GPT-4 as its core LLM, augmented with 18 expert-designed tools specifically selected for chemistry applications [19] [20].

The tools integrated with ChemCrow fall into three primary categories: (1) General tools including web search and Python REPL for code execution; (2) Molecule tools for molecular property prediction, functional group identification, and chemical structure conversion; and (3) Reaction tools for synthesis planning and prediction [21]. This comprehensive toolkit enables ChemCrow to address challenges across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design, making it particularly valuable for researchers who may lack expertise across all these specialized areas.

Demonstrated Applications and Performance

ChemCrow has demonstrated remarkable capabilities in automating complex chemical workflows. In one notable application, the system autonomously planned and executed the synthesis of an insect repellent (DEET) and three organocatalysts using IBM Research's cloud-connected RoboRXN platform [19] [21]. What made this achievement particularly impressive was ChemCrow's ability to iteratively adapt synthesis procedures when initial plans contained errors like insufficient solvent or invalid purification actions, eliminating the need for human intervention in the validation process.

In another groundbreaking demonstration, ChemCrow facilitated the discovery of a novel chromophore. The agent was instructed to train a machine learning model to screen a library of candidate chromophores, which involved loading, cleaning, and processing data; training and evaluating a random forest model; and providing suggestions based on a target absorption maximum wavelength of 369 nm [19]. The proposed molecule was subsequently synthesized and analyzed, confirming the discovery of a new chromophore with a measured absorption maximum wavelength of 336 nm—demonstrating the system's potential to contribute to genuine scientific discovery.

Table 1: ChemCrow's Tool Categories and Functions

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| General Tools | WebSearch, LitSearch, Python REPL | Access current information, execute computational code |

| Molecule Tools | Name2SMILES, FunctionalGroups, MoleculeProperties | Convert chemical names, identify functional groups, predict properties |

| Reaction Tools | ReactionPlanner, ForwardSynthesis, ReactionExecute | Plan synthetic routes, predict reaction outcomes, execute syntheses |

The Expanding Ecosystem of Chemistry AI Agents

ChemToolAgent: An Enhanced Implementation

Building upon ChemCrow's foundation, researchers have developed ChemToolAgent (CTA), which expands the toolset to 29 specialized instruments and implements enhancements to existing tools [22]. This system represents a significant evolution in capability, with 16 entirely new tools and 6 substantially enhanced from the original ChemCrow implementation. Notable additions include PubchemSearchQA, which leverages an LLM to retrieve and extract comprehensive compound information from PubChem, and specialized molecular property predictors (BBBPPredictor, SideEffectPredictor) that employ neural networks for precise property predictions [22].

CTA's performance on specialized chemistry tasks demonstrates the value of this expanded capability. When evaluated on SMolInstruct—a benchmark containing 14 molecule- and reaction-centric tasks—CTA substantially outperformed both its base LLM counterparts and the original ChemCrow implementation [22]. This performance advantage highlights the critical importance of having a comprehensive and robust toolset for specialized chemical operations involving molecular representations like SMILES and specific chemical operations such as compound synthesis and property prediction.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation: ChemRAG Framework

Complementing the tool-augmentation approach, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has emerged as a powerful framework for enhancing LLMs with external knowledge sources. The recently introduced ChemRAG-Bench provides a comprehensive evaluation framework comprising 1,932 expert-curated question-answer pairs across diverse chemistry tasks [23] [24]. This benchmark systematically assesses RAG effectiveness across description-guided molecular design, retrosynthesis, chemical calculations, molecule captioning, name conversion, and reaction prediction.

The results from ChemRAG evaluations demonstrate that RAG yields a substantial performance gain—achieving an average relative improvement of 17.4% over direct inference methods without retrieval [23]. Different chemistry tasks show distinct preferences for specific knowledge corpora; for instance, molecule design and reaction prediction benefit more from literature-derived corpora, while nomenclature and conversion tasks favor structured chemical databases [23]. This suggests that task-aware corpus selection is crucial for maximizing RAG performance in chemical applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Chemistry AI Agents Across Benchmark Tasks

| Model | SMolInstruct (Specialized Tasks) | MMLU-Chemistry (General Questions) | GPQA-Chemistry (Graduate Level) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base LLM (GPT-4o) | Varies by task (lower on specialized operations) | 74.59% accuracy | Not specified |

| ChemCrow | Strong performance on synthesis planning | Not specified | Not specified |

| ChemToolAgent | Substantial improvements over base LLMs | Does not consistently outperform base LLMs | Underperforms base LLMs |

| RAG-Enhanced LLMs | Not specified | Up to 73.92% accuracy (GPT-4o) | Not specified |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Specialized Tasks vs. General Chemistry Knowledge

A comprehensive evaluation of tool-augmented agents reveals a fascinating pattern: their effectiveness varies dramatically depending on the nature of the task. For specialized chemistry tasks—such as synthesis prediction, molecular property prediction, and reaction outcome prediction—tool augmentation provides substantial benefits. ChemToolAgent, for instance, demonstrates significant improvements over base LLMs on the SMolInstruct benchmark, particularly for tasks like name conversion (NC-S2I), property prediction (PP-SIDER), forward synthesis (FS), and retrosynthesis (RS) [22].

Conversely, for general chemistry questions—such as those found in standardized exams and educational contexts—tool augmentation does not consistently outperform base LLMs, and in some cases even underperforms them [22]. This counterintuitive finding suggests that for problems requiring broad chemical knowledge and reasoning rather than specific computational operations, the additional complexity of tool usage may actually hinder performance. Error analysis with chemistry experts indicates that CTA's underperformance on general chemistry questions stems primarily from nuanced mistakes at intermediate problem-solving stages, including flawed logic and information oversight [22].

Evaluation Methodologies: Human Experts vs. Automated Metrics

The evaluation of chemistry AI agents presents unique challenges, particularly in determining appropriate assessment methodologies. Studies comparing ChemCrow with base LLMs have revealed significant discrepancies between human expert evaluations and automated LLM-based assessments like EvaluatorGPT [19] [20]. While experts consistently prefer and rate ChemCrow's answers more highly, EvaluatorGPT tends to rate GPT-4 as superior based largely on response fluency and superficial completeness [21]. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of LLM-based evaluators for assessing factual accuracy in specialized domains and underscores the need for expert-driven validation in scientific AI applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Standards and Procedures

Rigorous evaluation of tool-augmented LLMs in chemistry requires standardized benchmarking approaches. The ChemRAG-Bench framework employs four core evaluation scenarios designed to mirror real-world information needs: (1) Zero-shot learning to simulate novel chemistry discovery scenarios; (2) Open-ended evaluation for tasks like molecule design and retrosynthesis; (3) Multi-choice evaluation for standardized assessment; and (4) Question-only retrieval where only the question serves as the query for RAG systems [23]. This comprehensive approach ensures that evaluations reflect diverse real-world usage scenarios.

For specialized task evaluation, the SMolInstruct benchmark provides 14 types of molecule- and reaction-centric tasks, with models typically evaluated on 50 randomly selected samples from the test set for each task type [22]. For general chemistry knowledge assessment, standardized subsets of established benchmarks are used, including MMLU-Chemistry (high school and college level), SciBench-Chemistry (college-level calculation questions), and GPQA-Chemistry (difficult graduate-level questions) [22]. This multi-tiered evaluation strategy enables researchers to assess performance across different complexity levels and task types.

Workflow for Synthesis Planning and Execution

The experimental workflow for chemical synthesis tasks demonstrates the integrated nature of tool-augmented agents. As illustrated below, the process begins with natural language input, proceeds through iterative tool usage, and culminates in physical synthesis execution:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Automated Synthesis Planning and Execution. This diagram illustrates the iterative process ChemCrow uses to plan and execute chemical syntheses, featuring validation and refinement cycles [19] [21].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The effectiveness of tool-augmented LLMs in chemistry depends critically on the quality and diversity of the tools integrated into their ecosystem. The following table details key "research reagent solutions"—the computational tools and resources that enable these systems to perform sophisticated chemical reasoning and operations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemistry AI Agents

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function | Implementation in Agents |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem Database | Chemical Database | Provides authoritative compound information | Used via PubchemSearchQA for structure and property data |

| SMILES Representation | Molecular Notation | Standardized text-based molecular representation | Enables molecular manipulation and property prediction |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Provides fundamental operations for molecular analysis |

| RoboRXN | Cloud Laboratory | Automated synthesis platform | Enables physical execution of planned syntheses |

| ForwardSynthesis | Reaction Tool | Predicts outcomes of chemical reactions | Used for reaction feasibility assessment |

| Retrosynthesis | Reaction Tool | Plans synthetic routes to target molecules | Core component for synthesis planning |

| Python REPL | General Tool | Executes Python code for computations | Enables custom calculations and data processing |

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Research on tool-augmented chemistry agents suggests several promising directions for future development. The finding that tool augmentation doesn't consistently help with general chemistry questions indicates a need for better cognitive load management and enhanced reasoning capabilities [22]. Future systems may benefit from adaptive tool usage strategies that selectively engage tools only when necessary for specific operations, preserving the LLM's inherent reasoning capabilities for broader questions.

For RAG systems, the observed log-linear scaling relationship between the number of retrieved passages and downstream performance suggests that retrieval depth plays a crucial role in generation quality [23]. Additionally, ensemble retrieval strategies that combine the strengths of multiple retrievers have shown promise for enhancing performance across diverse chemistry tasks. These insights provide practical guidance for developers seeking to optimize chemistry AI agents for specific applications.

Safety and Responsible Implementation

As tool-augmented chemistry agents become more capable, ensuring their safe and responsible use becomes increasingly important. ChemCrow incorporates safety measures including hard-coded guidelines that check if queried molecules are controlled chemicals, stopping execution if safety concerns are detected [21]. The system also provides safety instructions and handling recommendations for proposed substances, integrating safety checks with expert review systems to align with laboratory safety standards.

The potential for erroneous decision-making due to inadequate chemical knowledge in LLMs necessitates robust validation mechanisms. This risk is mitigated through the integration of expert-designed tools and improvements in training data quality and scope [21]. Users are also encouraged to critically evaluate AI-generated information against established literature and expert opinion, particularly for high-stakes applications in drug discovery and materials design.

Tool augmentation represents a transformative approach for adapting LLMs to the exacting demands of chemical research. Systems like ChemCrow and ChemToolAgent have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in automating specialized tasks such as synthesis planning, molecular design, and property prediction. Yet comprehensive evaluations reveal that these approaches are not universally superior—their effectiveness depends critically on task characteristics, with specialized operations benefiting more from tool integration than general knowledge questions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings offer nuanced guidance for implementing AI tools in their workflows. Specialized chemical operations involving molecular representations and predictions stand to benefit significantly from tool-augmented approaches, while broader chemistry knowledge tasks may be better served by base LLMs or retrieval-augmented systems. As the field evolves, the optimal approach will likely involve context-aware systems that dynamically adjust their strategy based on problem characteristics, balancing the powerful capabilities of tool augmentation with the inherent reasoning strengths of modern LLMs.

The conceptual framework of "active" versus "passive" management, well-established in financial markets, provides a powerful lens for evaluating artificial intelligence systems in scientific domains. In investing, active management seeks to outperform market benchmarks through skilled security selection and tactical decisions, while passive management aims to replicate benchmark performance at lower cost [25]. The core differentiator lies in market efficiency – in highly efficient markets where information rapidly incorporates into prices, passive strategies typically dominate due to cost advantages, whereas in less efficient markets, skilled active managers can potentially add value [25].

This paradigm directly translates to evaluating Large Language Models in chemistry and drug development. Passive AI systems operate as knowledge repositories, recalling and synthesizing established chemical information from their training data. In contrast, active AI systems function as discovery engines, generating novel hypotheses, designing experiments, and elucidating previously unknown mechanisms. The critical distinction mirrors the investment world: in well-mapped chemical territories with extensive training data, passive knowledge recall may suffice, but in frontier research areas with sparse data, active reasoning capabilities become essential for genuine scientific progress.

Recent benchmarking studies reveal that even state-of-the-art LLMs demonstrate this performance dichotomy – showing strong performance on established chemical knowledge while struggling with novel mechanistic reasoning [2] [16]. Understanding where and why this divergence occurs is crucial for deploying AI effectively across the drug development pipeline, from initial target identification to clinical trial optimization.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons Across Domains

Financial Markets: A Pattern of Context-Dependent Performance

Comprehensive analysis of active versus passive performance across asset classes reveals consistent patterns that inform our understanding of AI systems. The following table summarizes recent performance data across multiple markets:

Table 1: Active vs. Passive Performance Across Asset Classes (Q2 2025 - Q3 2025)

| Asset Class | Benchmark | Q2 2025 Active vs. Benchmark | YTD 2025 Active vs. Benchmark | TTM Active vs. Benchmark | Long-Term Trend (5-Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Large Cap Core | Russell 1000 | -1.20% [26] | -0.44% [26] | -2.81% [26] | Consistent passive advantage [25] |

| U.S. Small Cap Core | Russell 2000 | -1.74% [26] | +0.01% [26] | -1.61% [26] | Mixed, occasional active advantage [25] |

| Developed International | MSCI EAFE | -0.11% [26] | -0.44% [26] | +0.70% [26] | Around 50th percentile [25] |

| Emerging Markets | MSCI EM | +0.88% [26] | -0.71% [26] | -2.34% [26] | Consistent active advantage [25] |

| Fixed Income | Bloomberg US Agg | -0.01% [26] | -0.15% [26] | -0.09% [26] | Strong active advantage [25] |

The financial data demonstrates a crucial principle: environmental efficiency determines strategy effectiveness. In highly efficient, information-rich environments like U.S. large-cap equities, passive strategies consistently outperform most active managers, with only 31% of active U.S. stock funds surviving and outperforming their average passive peer over 12 months through June 2025 [27]. Conversely, in less efficient markets like emerging market equities and fixed income, active management shows stronger results, with the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index ranking in the bottom quartile for extended periods [25].

AI Chemical Reasoning: Benchmarking Knowledge vs. Reasoning

Translating this framework to AI evaluation, we can distinguish between passive chemical knowledge (recall of established facts, reactions, and properties) and active chemical reasoning (novel mechanistic elucidation and experimental design). Recent benchmarking studies reveal a performance gap mirroring the financial markets:

Table 2: LLM Performance on Chemical Knowledge vs. Reasoning Benchmarks

| Benchmark Category | Benchmark Name | Key Metrics | Top Model Performance | Human Expert Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Knowledge | ChemBench [2] | Accuracy on 2,700+ QA pairs | Best models outperformed best human chemists on average [2] | Surpassed human performance on knowledge recall [2] |

| Active Reasoning | oMeBench [16] | Mechanism accuracy, chemical similarity | Struggles with multi-step reasoning [16] | Lags behind expert mechanistic intuition [16] |

| Specialized Reasoning | Organic Mechanism Elucidation [16] | Step-level logic, pathway correctness | 50% improvement possible with specialized training [16] | Requires expert-level chemical intuition |

The benchmarking data reveals that LLMs excel as passive knowledge repositories but struggle as active reasoning systems. In the ChemBench evaluation, which covers undergraduate and graduate chemistry curricula, the best models on average outperformed the best human chemists in the study [2]. However, this strong performance masks critical weaknesses in active reasoning capabilities. On oMeBench, the first large-scale expert-curated benchmark for organic mechanism reasoning comprising over 10,000 annotated mechanistic steps, models demonstrated promising chemical intuition but struggled with "correct and consistent multi-step reasoning" [16].

This performance dichotomy directly parallels the financial markets: in information-rich, well-structured chemical knowledge domains (analogous to efficient markets), LLMs function exceptionally well as passive systems. However, in novel reasoning tasks requiring multi-step logic and mechanistic insight (analogous to inefficient markets), current models show significant limitations without specialized adaptation.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Benchmarking AI Chemical Capabilities

Chemical Knowledge Assessment (ChemBench Protocol)

The ChemBench framework employs a rigorous methodology for evaluating both passive knowledge recall and active reasoning capabilities:

Dataset Composition: The benchmark comprises 2,788 question-answer pairs compiled from diverse sources, including 1,039 manually generated and 1,749 semi-automatically generated questions [2]. The corpus spans general chemistry, inorganic, analytical, and technical chemistry, with both multiple-choice (2,544) and open-ended (244) formats [2].

Skill Classification: Questions are systematically classified by required cognitive skills: knowledge, reasoning, calculation, intuition, or combination. Difficulty levels are annotated to enable nuanced capability assessment [2].

Evaluation Methodology: The framework uses automated evaluation of text completions, making it suitable for black-box and tool-augmented systems. For specialized content, it implements semantic encoding of chemical structures (SMILES), equations, and units using dedicated markup tags [2].

Human Baseline Establishment: To contextualize model performance, the benchmark incorporates results from 19 chemistry experts surveyed on a benchmark subset, with some volunteers permitted to use tools like web search to simulate real-world conditions [2].

Mechanism Reasoning Evaluation (oMeBench Protocol)

The oMeBench benchmark focuses specifically on evaluating active reasoning capabilities through organic mechanism elucidation:

Dataset Construction: The benchmark comprises three complementary datasets: (1) oMe-Gold (196 expert-verified reactions from textbooks and literature), (2) oMe-Template (167 expert-curated templates abstracted from gold set), and (3) oMe-Silver (2,508 reactions automatically expanded from templates with filtering) [16].

Difficulty Stratification: Reactions are classified by mechanistic complexity: Easy (20%, single-step logic), Medium (70%, conditional reasoning), and Hard (10%, novel or complex multi-step pathways) [16].

Evaluation Metrics: The benchmark employs oMeS (Organic Mechanism Scoring), a dynamic evaluation framework combining step-level logic and chemical similarity metrics. This enables fine-grained scoring beyond binary right/wrong assessment [16].

Model Testing Protocol: Models are evaluated on their ability to generate valid intermediates, maintain chemical consistency, and follow logically coherent multi-step pathways, with specific analysis of failure modes in complex or lengthy mechanisms [16].

Clinical Development Applications

In drug development, the active-passive paradigm manifests in emerging applications that bridge AI systems with physical-world experimentation:

Synthetic vs. Real-World Data: A significant shift is occurring toward prioritizing high-quality, real-world patient data over synthetic data for AI model training in drug development, recognizing limitations and potential risks of purely synthetic approaches [28].

Hybrid Trial Implementation: Hybrid clinical trials are becoming the new standard, especially in chronic diseases, leveraging natural language processing and predictive analytics to engage patients more effectively and incorporate real-world evidence into trial design [28].

Biomarker Validation: Psychiatric drug development is seeing advances in biomarker validation, with event-related potentials emerging as promising functional brain measures that are reliable, consistent, and interpretable for clinical trials [28].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for AI Chemical Reasoning

The evaluation and development of AI systems for chemical applications requires specialized "research reagents" – benchmark datasets, evaluation frameworks, and analysis tools. The following table details essential resources for this emerging field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AI Chemical Reasoning Evaluation

| Reagent Category | Specific Tool/Dataset | Primary Function | Key Applications | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Knowledge Benchmarks | ChemBench [2] | Evaluate broad chemical knowledge across topics and difficulty levels | General capability assessment, education applications | Accuracy on 2,788 QA pairs, human-expert comparison [2] |

| Specialized Reasoning Benchmarks | oMeBench [16] | Assess organic mechanism reasoning with expert-curated reactions | Drug discovery, reaction prediction, chemical education | Mechanism accuracy, step-level logic, chemical similarity [16] |

| Biomedical Language Understanding | BLURB Benchmark [29] | Evaluate biomedical NLP capabilities across 13 datasets | Literature mining, knowledge graph construction, pharmacovigilance | F1 scores for NER (~85-90%), relation extraction (~73%) [29] |

| Biomedical Question Answering | BioASQ [29] | Test QA capabilities on biomedical literature | Research assistance, clinical decision support | Accuracy for factoid/list/yes-no questions, evidence retrieval [29] |

| General AI Agent Evaluation | AgentBench [30] | Assess multi-step reasoning and tool use across environments | Autonomous research agent development, workflow automation | Success rates across 8 environments (OS, database, web tasks) [30] |

The active-passive framework provides valuable insights for developing and deploying AI systems across chemical research and drug development. The evidence demonstrates that current LLMs excel as passive knowledge systems but require significant advancement to function as reliable active reasoning systems for novel scientific discovery.

This dichotomy mirrors the investment world, where passive strategies dominate efficient markets while active management adds value in complex, information-sparse environments. The most effective approach involves strategic integration of both paradigms: leveraging passive AI capabilities for comprehensive knowledge recall and literature synthesis, while developing specialized active reasoning systems for mechanistic elucidation and hypothesis generation.

As benchmarking frameworks become more sophisticated and domain-specific, the field moves toward a future where AI systems can genuinely partner with human researchers across the entire scientific pipeline – from initial literature review to physical-world experimentation and clinical development. The critical insight is that environmental efficiency dictates system effectiveness, requiring thoughtful matching of AI capabilities to scientific problems based on their information richness and mechanistic complexity.

Autonomous agentic systems represent a paradigm shift in scientific research, moving from AI as a passive tool to an active, reasoning partner capable of designing and running experiments. This guide objectively compares the performance, architectures, and validation of leading systems in chemistry, with a specific focus on their ability to plan and execute chemical synthesis.

The table below provides a high-level comparison of two prominent agentic systems for autonomous chemical research.

| Feature | Coscientist [31] [32] | Google AI Co-Scientist [33] |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Modular LLM (GPT-4) with tools for web search, code execution, and documentation [32]. | Multi-agent system with specialized agents (Generation, Reflection, Ranking, etc.) built on Gemini 2.0 [33]. |

| Primary Function | Autonomous design, planning, and execution of complex experiments [32]. | Generating novel research hypotheses and proposals; accelerating discovery [33]. |

| Synthesis Validation | Successfully executed Nobel Prize-winning Suzuki and Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions [31]. | Proposed and validated novel drug repurposing candidates for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in vitro [33]. |

| Key Outcome | First non-organic intelligence to plan, design, and execute a complex human-invented reaction [31]. | Generated novel, testable hypotheses validated through lab experiments; system self-improves with compute [33]. |

| Automation Integration | Direct control of robotic liquid handlers and spectrophotometers via code [31] [32]. | Designed for expert-in-the-loop guidance; outputs include detailed research overviews and experimental protocols [33]. |

Detailed Performance Benchmarks

Beyond specific system capabilities, the field uses standardized benchmarks to objectively evaluate the chemical knowledge and reasoning abilities of AI systems. The following table summarizes performance data from key benchmarks, which contextualize the prowess of agentic systems.

| Benchmark / Task | Model / System | Performance Metric | Human Expert Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChemBench [2] | Leading LLMs (Average) | Outperformed the best human chemists in the study on average [2]. | Baseline (Average chemist) |

| ChemBench [2] | Leading LLMs (Specific Tasks) | Struggled with some basic tasks; provided overconfident predictions [2]. | Varies by task |

| ChemIQ [5] | GPT-4o (Non-reasoning) | 7% accuracy (on short-answer questions requiring molecular comprehension) [5]. | Not Specified |

| ChemIQ [5] | OpenAI o3-mini (Reasoning Model) | 28% - 59% accuracy (varies with reasoning level) [5]. | Not Specified |

| WebArena [34] | Early GPT-4 Agents | ~14% task success rate [34]. | ~78% task success rate [34] |

| WebArena [34] | 2025 Top Agents (e.g., IBM's CUGA) | ~62% task success rate [34]. | ~78% task success rate [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A rigorous and reproducible experimental protocol is fundamental to validating the capabilities of autonomous systems. The following workflow details the core operational loop of a system like Coscientist.

Key Experimental Steps:

- Task Decomposition: The Planner module (e.g., GPT-4) receives a natural language command (e.g., "perform multiple Suzuki reactions") and breaks it down into sub-tasks [32].

- Knowledge Acquisition: The system uses its modules to gather necessary information.

- Code Generation and Validation: The PYTHON command allows the Planner to generate computer code to control the laboratory instruments. The code is often executed in a sandboxed environment to catch and fix errors iteratively [32].

- Physical Execution: The EXPERIMENT command sends the finalized code to the appropriate robotic hardware, such as liquid handlers for dispensing reactants and spectrophotometers for analysis [31] [32].

- Output Analysis: The system analyzes the resulting data (e.g., spectral output from a spectrophotometer) to confirm the success of the experiment, such as identifying the spectral hallmarks of the target molecule [31].

Multi-Agent Reasoning Architecture

For more complex tasks like generating novel hypotheses, a multi-agent architecture has proven effective. The Google AI Co-Scientist employs a team of specialized AI agents that work in concert, mirroring the scientific method.

Key Workflow Steps:

- Orchestration: A Supervisor agent parses the research goal and allocates tasks to a queue of specialized worker agents [33].

- Generation and Critique: Specialized agents (Generation, Reflection, Ranking, Evolution) engage in an iterative loop. The Generation agent proposes hypotheses, which are critiqued by the Reflection agent and compared in tournaments by the Ranking agent [33].

- Iterative Refinement: The Evolution agent refines the hypotheses based on the feedback. This cycle of generate-evaluate-refine continues, creating a self-improving system where output quality increases with computational time [33].

- Output: The result is a novel, high-quality research hypothesis and a detailed plan tailored to the specified goal [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers looking to implement or evaluate similar autonomous systems, the following table details key components and their functions as used in validated experiments.

| Reagent / Resource | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Palladium Catalysts [31] | Essential catalyst for Nobel Prize-winning cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Sonogashira) executed by Coscientist [31]. |

| Organic Substrates | Reactants containing carbon-based functional groups used in cross-coupling reactions to form new carbon-carbon bonds [31]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handler | Automated instrument (e.g., from Opentrons or Emerald Cloud Lab) that precisely dispenses liquid samples in microplates as directed by AI-generated code [31] [32]. |

| Spectrophotometer | Analytical instrument used to measure light absorption by samples; Coscientist used it to identify colored solutions and confirm reaction products via spectral data [31]. |

| Chemical Databases (Wikipedia, Reaxys, SciFinder) | Grounding sources of public chemical information that agents use to learn about reactions, procedures, and compound properties [31] [32]. |

| Application Programming Interface (API) | A standardized set of commands (e.g., Opentrons Python API, Emerald Cloud Lab SLL) that allows the AI agent to programmatically control laboratory hardware [32]. |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Cell Lines [33] | In vitro models used to biologically validate the AI Co-Scientist's proposed drug repurposing candidates for their tumor-inhibiting effects [33]. |

The experimental data confirms that agentic systems like Coscientist and Google's AI Co-Scientist have moved from concept to functional lab partners. Coscientist has demonstrated the ability to autonomously execute complex, known chemical reactions [31] [32], while the AI Co-Scientist shows promise in generating novel hypotheses that have been validated in real-world laboratory experiments [33].

However, benchmarks reveal important nuances. While LLMs can outperform average human chemists on broad knowledge tests like ChemBench [2], their performance plummets on benchmarks like ChemIQ that require deep molecular reasoning without external tools [5]. This highlights a continued reliance on tool integration for robust performance. Furthermore, agents operating in complex, dynamic environments like web browsers still significantly trail human capabilities [34].